Abstract

A key goal in cancer research is to identify the total complement of genetic and epigenetic alterations that contribute to tumorogenesis. We are currently witnessing the rapid evolution and convergence of multiple genome-wide platforms that are making this goal a reality. Leading this effort are studies on the molecular lesions that underlie pediatric acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL). The recent application of microarray-based analyses of DNA copy number abnormalities in pediatric ALL, complemented by transcriptional profiling, resequencing and epigenetic approaches have identified a high frequency of common genetic alterations in both B-progenitor and T-lineage ALL. These approaches have identified abnormalities in key pathways including lymphoid differentiation, cell cycle regulation, tumor suppression and drug responsiveness. Moreover, the nature and frequency of CNAs were shown to markedly differ among ALL genetic subtypes. In this article, we review the key findings from the published data on genome-wide analyses of ALL and highlight some of the technical aspects of the data generation and analysis that must be carefully controlled to obtain optimal results.

Introduction

Treatment of pediatric acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL) represents one of the great triumphs of modern cancer therapy, with cure rates now exceeding 80% (1,2). Despite this overall success, several ALL subtypes continue to have a poor prognosis, most notably BCR-ABL1 and MLL-rearranged leukemia. In addition, in a proportion of cured patients, treatment results in substantial short- and long-term toxicity. In contrast to the results in pediatric patients, overall outcomes for adult patients with ALL are substantially worse, in part reflective of a higher proportion of poor risk ALL subtypes (3,4). Thus, there is substantial scope for further improvements in the therapy of pediatric and adult ALL The most rational approach to improving survivals is to develop novel therapies directed against biological targets. To define suitable targets, we first need a comprehensive understanding of the genetic lesions that contribute to leukemogenesis..

ALL has long been one of the best characterized malignancies from a genetic viewpoint. Gross numerical and structural chromosomal abnormalities identified by cytogenetic analysis are a hallmark of ALL, and include hyperdiploidy, hypodiploidy, and translocations t(12;21)[ETV6-RUNX1], t(1;19)[TCF3-PBX1], t(9;22)[BCR-ABL1] and rearrangement of the MLL gene in B-progenitor ALL, rearrangement of MYC in mature B-cell leukemia/lymphoma, and a number of recurring cytogenetic abnormalities in T-lineage ALL including rearrangement of the HOX11, HOX11L2, LYL1, TAL1 and MLL genes (5-8). Detection of these abnormalities by cytogenetic or molecular methods is important in diagnosis and risk stratification, and identification of the genes targeted by chromosomal abnormalities has provided crucial insights into normal and leukemic hematopoiesis. However several observations indicate that these lesions alone are insufficient to induce leukemia, and that cooperating lesions are required. First, chimeric transcripts encoded by chromosomal translocations may be detected years before the onset of leukemia (9). Second, the frequency of ETV6-RUNX1 transcripts detected in blood obtained at birth (Guthrie spots) is 100-fold higher than the frequency of ETV6-RUNX1 ALL. Third, the expression of translocation encoded products in experimental models fails to induce ALL without the introduction of defined cooperating lesions (10), such as loss of the CDKN2A-encoded ARF tumor suppressor in models of BCR-ABL1 leukemia (11), or non-specific secondary mutagenesis. In addition, approximately one-quarter of pediatric ALL cases lack recurring cytogenetic abnormalities, and the molecular basis of these cases is unknown; this proportion is even higher in adult ALL (12)

Until recently, the search for cooperating lesions has focused on specific candidate genes or has utilized relatively low resolution approaches, such as microsatellite mapping for regions of loss-of-heterozygosity (LOH). The candidate gene approach has identified key lesions including deletion of the CDKN2A/CDKN2B tumor suppressor locus (13-15) and mutation of NOTCH1 in T-lineage ALL (16). With the advent of microarray-based gene expression profiling technology, several ALL studies provided valuable insights into the cellular pathways perturbed in specific leukemic subtypes (17,18). A weakness of these gene expression profiling studies, however, was the difficulty in using long lists of differentially regulated genes to identify perturbations responsible for the leukemic transcriptome. The more recent development of microarray and high-throughput sequencing methodologies enabled identification of genomic abnormalities in a systematic, genome-wide, high-resolution fashion in large numbers of samples (Table 1). These approaches have yielded major advances in our understanding of the genetic lesions underlying the molecular pathology of ALL, as described below.

Table 1.

Methods available for detection of genomic abnormalities in ALL*

| Abnormality | Method | Comments |

|---|---|---|

| Chromosomal abnormalities |

Karyotyping | Good for numerical and structural rearrangements, limited resolution for small copy number abnormalities |

| Fluorescence in-situ hybridization |

Good for specific abnormalities (e.g. rearrangements) |

|

| Spectral karyotyping | Good for characterizing novel gross rearrangmements that may be cryptic by normal chromosome banding methods |

|

| Loss of heterozygosity |

Microsatellite genotyping |

Suitable for small panels of markers only |

| SNP microarrays | Genome-wide analysis, simultaneous analysis with copy number abnormalities |

|

| Copy number abnormalities |

BAC microarrays | Tiling whole genome coverage, but large probe size and limited resolution |

| Oligonucleotide microarrays |

Unlimited resolution, no SNP genotyping (except for SNP microarrays) |

|

| SNP microarrays | Good resolution (currently ~1kb probe spacing), simultaneous LOH analysis |

|

| Single molecule sequencing |

Whole genome coverage and simultaneous SNP genotyping and mutation/ novel variant detection. Methods are also be developed to identify all gene rearrangements |

|

| Epigenetic modifications | ||

| Cytosine methylation |

Bisulfite modification and PCR approaches |

e.g. methylation specific PCR, PCR and sequencing, PCR and mass-spectrometry. Well established, high quality data for panels of genes. |

| Microarray approaches |

e.g. immunoprecipitation with anti-methylcytosine antibodies, or methylation sensitive restriction digests followed by hybridization to microarrays. Genome wide coverage but potential bias to known CpG sites represented on array. |

|

| Next generation sequencing |

Potential whole genome coverage, simultaneous analysis with histone modification |

|

| Histone modification |

Microarray approaches |

e.g. IP and microarray hybridization |

| Next generation sequencing |

Whole genome coverate | |

| Gene expression | Quantitative PCR | Accurate data for limited numbers of genes |

| Microarrays | Well established; newer arrays offer tiling design. Also examine non-coding microRNAs |

|

| Next generation sequencing |

Whole genome coverage, eventually may replace microarray approaches |

|

In general, methods are ordered by resolution (lowest to highest).

Microarray analysis of DNA copy number alterations in acute leukemia

Several microarray platforms are available for the analysis of DNA copy number abnormalities (CNAs) and LOH in cancer, each with its advantages and disadvantages. The basic method involves the hybridization of a labeled sample of test DNA to microarrays that carry thousands to millions of probes, each of which is specific for a different region of the genome. The hybridization strategy may be single color (in the case of single nucleotide polymorphism [SNP] microarrays) or dual color (in the case of many oligonucleotide and bacterial artificial chromosome [BAC] microarrays), in which test and reference DNA are hybridized simultaneously. BAC microarrays were among the first developed and are still widely used. These arrays use probes derived from libraries of tens of thousands of BACs, each of which contains a large fragment of human DNA up to several hundred kilobases in size. These arrays generally yield high quality data with an excellent signal-to-noise ratio, but due to the large probe size the resolution is relatively low. BAC arrays have been employed in many studies examining genomic abnormalities (19-33) and have identified numerous CNAs. BAC arrays reliably detect large scale genomic aberrations in ALL, but due to their limited resolution may miss focal CNAs (21), which higher-resolution platforms have shown to be characteristic of ALL.

Oligonucleotide arrays utilize short nucleotide probes, generally ranging from 20 to 100 nucleotides that are either spotted or synthesized on microarrays. Due to the short probe length, oligonucleotide arrays can interrogate genomes at very high resolution, especially with newer platforms that place millions of probes on a single microarray. It is thus possible to tile across specific regions (or using multiple chips, whole genomes), providing extremely detailed maps of genetic alterations in ALL (34-36).

SNP microarrays are a type of oligonucleotide array in which probes are specific for sequences flanking single nucleotide polymorphisms. These arrays were initially developed as tools to facilitate genome wide linkage and association studies to identify genetic markers associated with inherited and acquired diseases. SNP markers are selected to provide maximum genetic information for a given gene or region, and a single marker may represent a “tag” SNP for a region of genetic variants in linkage disequilibrium (37). Particularly for earlier generation arrays, the physical distribution of SNP markers was uneven across the genome, with many regions and genes relatively poorly covered. Of importantce, in addition to genotyping SNPs, the intensity of probe hybridization on these arrays can be used to infer DNA copy number at each marker. SNP arrays thus provide the ability to detect CNAs and also perturbations in SNP genotypes. By comparing SNP genotypes of a tumor sample with reference samples - ideally a matched normal sample from the same individual - it is possible to detect LOH in a cancer. LOH may arise from deletion (deletional LOH), or from deletion with reduplication of the non-deleted chromosome (copy-neutral LOH, often referred to as acquired uniparental disomy). Detection of copy-neutral LOH may indicate duplication of a mutated or silenced tumor suppressor gene and is thus of considerable interest in cancer biology. The ability to detect copy neutral LOH gives SNP arrays a potential advantage over alternative array platforms, and is discussed in detail in the context of ALL below.

SNP array studies in ALL

The first reported SNP array study of ALL examined 10 pediatric cases using Affymetrix 10K SNP arrays (incorporating approximately 11,000 markers) and detected LOH in 8 cases (38). A region of chromosome 9p harboring the CDKN2A/CDKN2B tumor suppressor locus was most frequently involved, but the low resolution of the arrays (100-200kb between markers) prevented precise delineation of the regions involved, and the copy number status at each region was not reported.

We performed a large study of 242 pediatric ALL cases (192 B-progenitor, 50 T-lineage) using three Affymetrix SNP arrays (50k Hind and Xba, and 250 Sty) that together examine over 350,000 markers, with an intermarker resolution of less than 5kb (39). Corresponding constitutional DNA was available for most cases, enabling accurate determination of LOH and the distinction between inherited and somatic (tumor-acquired) CNAs. A major hurdle was the lack of suitable available tools to normalize SNP array data and to accurately detect all CNAs. We developed a normalization approach (reference normalization) and adapted a CNA detection platform, circular binary segmentation (40), to overcome these problems (discussed further below).

We identified a relatively low number of CNAs in ALL - a mean of 6.46 lesions per case - indicating that gross genomic instability is not a feature of most ALL cases. There was significant variation in the number of CNAs across leukemic subtypes. Specifically, apart from high hyperdiploid ALL, gains of DNA were uncommon, and included amplification of MYB in T-ALL and focal internal amplifications of PAX5 in rare B-progenitor ALL. MLL-rearranged ALL, which typically presents early in infancy, had less than one CNA per case, suggesting that in this subtype few additional genetic lesions are required for leukemogenesis. In contrast, ETV6-RUNX1 and BCR-ABL1 ALL, which typically present later in childhood, had over 6 lesions per case, with some cases having over 20 lesions. This result is consistent with the concept that the initiating translocations develop early in childhood and additional lesions are subsequently required for leukemogenesis (9).

Mutations of genes regulating B-lymphoid development in ALL

Our study identified over 50 recurring regions of copy number alteration in ALL (Table 2). Most were focal (minimal common region of CNA less than one Mb) and many involved genes with known or putative roles on leukemogenesis and cancer. The most striking novel finding was that genes encoding regulators of normal lymphoid development were mutated in over 40% of cases of B-progenitor ALL. The most frequent target was the lymphoid transcription factor PAX5, which harbored deletions or focal amplifications in almost 30% of B-ALL cases. CNAs were also detected in the transcription factor genes IKZF1 (Ikaros), IKZF3 (Aiolos), EBF1 (early B-cell factor), LEF1 and TCF3, and in the RAG1 and RAG2 genes. Appropriate expression of these genes is required for normal B-lymphoid commitment and differentiation (41,42). CNAs involving these genes were confirmed by either fluorescence in situ hybridization or quantitative genomic PCR (gqPCR), and the deletions of PAX5 were shown to reduce intracellular PAX5 levels by intracellular flow cytometry and quantitative RT-PCR. Resequencing of PAX5, EBF1 and IKZF1 identified missense, insertion/deletion, frameshift and splice-site mutations in PAX5 in 14 B-ALL cases, each of which involved the N-terminal DNA-binding paired domain or the C-terminal transactivation domain. We also identified two new PAX5 translocation, PAX5-FOXP1 and PAX5-ZNF521 [PAX5-EVI3], in addition to two cases with the previously reported PAX5-ETV6 translocation (43).

Table 2.

Selected recurring regions of DNA copy number alteration in pediatric ALL. Adapted from ref. (39)

| Cytoband | Start (Mb) |

End (Mb) |

Size (Mb) |

B-ALL N (%) |

T-ALL N (%) |

Gene(s) in region |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Deletions | ||||||

| 1p33 | 47.440 | 47.479 | 0.039 | 0 | 3 (6.0) | TAL1 |

| 2p21 | 43.337 | 43.624 | 0.287 | 2 (1.04) | 1 (2.0) | THADA |

| 3p14.2 | 60.064 | 60.318 | 0.254 | 8 (4.17) | 0 | FHIT |

| 3q13.2 | 113.538 | 113.686 | 0.148 | 13 (6.77) | 0 | CD200, BTLA |

| 3q26.32 | Various | 7 (3.13) | 0 | TBL1XR1 | ||

| 4q25 | 109.393 | 109.442 | 0.049 | 3 (1.56) | 4 (8.0) | LEF1 |

| 4q31.23 | 150.055 | 150.200 | 0.145 | 6 (3.13) | 1 (2.0) | None; telomeric to NR3C2 |

| 5q31.3 | 142.760 | 142.847 | 0.087 | 9 (4.69) | 3 (6.0) | NR3C1, LOC389335 |

| 5q33.3 | Various | 8 (4.17) | 3 (6.0) | EBF1 | ||

| 6p22.22 | 26.345 | 26.368 | 0.023 | 13 (6.77) | 0 |

HIST1H4F, HIST1H4G, HIST1H3F, HIST1H2BH |

| 6q16.2-3 | 99.852 | 102.492 | 2.640 | 10 (5.21) | 5 (10) | 16 genes including CCNC |

| 6q21 | 109.347 | 109.435 | 0.088 | 11 (5.73) | 4 (8.0) | ARMC2, SESN1 |

| 7p12.2 | 50.193 | 50.241 | 0.048 | 17 (8.85) | 1 (2.0) | IKZF1 ( Ikaros) |

| 8q12.1 | 60.195 | 60.289 | 0.094 | 7 (3.65) | 0 | Immediately 5′ TOX |

| 9p21.3 | Various | 65 (33.85) | 36 (72.0) |

CDKN2A | ||

| 9p13.2 | Various | 57 (29.69) | 5 (10)** |

PAX5 | ||

| 10q23.31 | 89.666 | 89.728 | 0.062 | 0 | 3 (6.0) | PTEN |

| 10q24.1 | 97.879 | 98.057 | 0.178 | 2 (1.04) | 0 | BLNK |

| 10q25.1 | 111.772 | 111.850 | 0.078 | 9 (4.69) | 0 | ADD3 |

| 11p13 | 33.874 | 34.029 | 0.155 | 1 (0.52) | 4 (8.0) | 5′ of LMO2 |

| 11p12 | 36.575 | 36.583 | 0.008 | 4 (2.08) | 2 (4.0) | RAG2, LOC119710 |

| 12p13.2 | Various | 11.808 | 0.020 | 51 (26.56) | 4 (8.0) | ETV6 |

| 12q21.33 | 90.786 | 91.039 | 0.253 | 13 (6.77) | 0 | 3′ of BTG1 |

| 13q14.11 | 43.758 | 43.895 | 0.137 | 10 (5.21) | 3 (6.0) | C13orf21, LOC400128 |

| 13q14.2 | 47.885 | 47.968 | 0.083 | 9 (4.69) | 6 (12.0) | RB1 |

| 13q14.2-3 | 49.471 | 50.360 | 0.889 | 12 (6.25) | 3 (6.0) | Includes MIRN16-1, MIRN15A, |

| 15q15.1 | 39.045 | 39.837 | 0.792 | 6 (3.13) | 0 | 18 genes including LTK and MIRN626 |

| 17q11.2 | 26.090 | 26.259 | 0.169 | 4 (2.08) | 2 (4.0) | 7 genes including NF1 |

| 17q21.1 | 35.185 | 35.230 | 0.045 | 3 (1.56) | 0 | IKZF3 (ZNFN1A3, Aiolos) |

| 19p13.3 | 0.229 | 1.531 | 1.302 | 17 (8.85) | 0 | TCF3 to 19ptel |

| 20p12.1 | 10.370 | 10.405 | 0.035 | 9 (4.69) | 1 (2.0) | C20orf94 |

| 21q22.12 | 35.350 | 35.354 | 0.004 | 3 (1.56) | 0 | Immediately distal to RUNX1 |

| 21q22.2 | 38.706 | 38.729 | 0.023 | 5 (2.60) | 0 | ERG |

| Amplifications | ||||||

| 1q23.3-q44 | 161.491 | qtel | 81.326 | 16 (8.33) | 0 | PBX1to 1qtel |

| 6q23.3 | 135.556 | 135.714 | 0.158 | 0 | 5 (10) | MYB, MIRN548A2, AHI1 |

| 9q34.12-q34.3 | 130.687 | qtel | 7.676 | 3 (1.56) | 0 | 155 genes telomeric of ABL1, including 3′ region of ABL1 |

| 21q22.11- q22.12 |

32.896 | 35.199 | 2.303 | 6 (3.125) | 0 | 33 genes including RUNX1 |

| 22q11.1- q11.23 |

ptel | 21.888 | 21.888 | 3 (1.56) | 0 | 277 genes telomeric (5′) of BCR, including 5′ region of BCR |

The majority of lesions were predicted to result in reduced levels of the encoded B lymphoid transcription factor rather than complete loss of expression. An implication was that genes such as PAX5 are haploinsufficient tumor suppressors in ALL; while requiring formal validation in experimental models, existing data suggest this is indeed the case. The PAX5 deletions, point mutations, and translocations inhibit normal PAX5 DNA-binding in gel-shift assays, and they impair transactivation of PAX5 targets in luciferase reporter and functional cell-based assays (39). Furthermore, in murine models of BCR-ABL1 leukemogenesis and retroviral/chemical mutagenesis, Pax5 haploinsufficiency results in increased penetrance, reduced latency, and a shift to an immature B-lymphoid phenotype (our unpublished observations). Thus, genomic lesions resulting in a block in B-lymphoid development appear to be key events in a large proportion of B-progenitor ALL cases. Indeed, in comparable high-resolution SNP array studies of high-risk B-progenitor pediatric ALL, the frequency of lesions targeting the B cell developmental pathway exceeds 50% (44). As the scope and resolution of studies examining the genomic abnormalities of ALL continue to improve, it is likely that this figure will rise.

Genomic determinants of lineage and disease progression in BCR-ABL1leukemia

In our initial ALL SNP array analysis, abnormalities of PAX5, IKZF1, and CDKN2A/B appeared to be very frequent in pediatric BCR-ABL1 ALL; however, the number of cases examined was small (N=9). Thus, we extended our existing studies to an expanded cohort of pediatric ALL (N=304), including 21 pediatric and 22 adult BCR-ABL1 cases, and 23 cases of BCR-ABL1 positive chromic myeloid leukemia (CML), that included samples obtained at various stages of disease progression, including 24 chronic phase (CP) samples, 7 accelerated phase samples, and 12 myeloid blast crisis, and 3 lymphoid blast crisis samples. Strikingly, IKZF1 (Ikaros) was deleted in 36 of 43 (84%) of BCR-ABL1ALL cases (16 of 21 pediatric and 20 of 22 adult cases)(45). In 19 cases, the deletions involved an internal subset of the 7 coding IKZF1 exons, most commonly exons 3-6, resulting in the expression of internally truncated IKZF1 transcripts. Ikaros acts upstream of EBF1 and PAX5 (46), and is required for the development of all lymphoid lineages (47). Notably, mice heterozygous for a dominant negative form of Ikaros develop aggressive T-lineage lymphoproliferative disease (48), and expression of aberrant Ikaros transcripts that lack one or more internal exons has been detected by nested RT-PCR in pediatric ALL (49-55). Using RT-PCR and immunoblotting, we found complete concordance between the extent of genomic IKZF1 lesions and expression of aberrant IKZF1 transcripts, indicating that expression of altered Ikaros isoforms to be the result of a genetic lesion. Deletion of IKZF1 was never observed in chronic phase CML samples but was detected in two of three lymphoid blast crisis samples. Genomic abnormalities of IKZF1 resulting in loss of expression or expression of dominant negative isoforms are thus critical in the pathogenesis of BCR-ABL1 lymphoid leukemia. Approximately half of both BCR-ABL1 ALL and CML lymphoid blast crisis (but not chronic phase) cases also harbor deletions of CDKN2A/B and PAX5, with 20% of cases containing deletions of all three genes. These data further support the concept that disruption of multiple cellular pathways is required to induce lymphoid leukemia (56). Dissecting the relative contribution of each of these lesions to leukemogenesis and therapeutic failure will be of great interest.

Mutations in other cellular pathways in B-ALL

We also identified CNAs targeting other genes regulating cellular growth, differentiation and drug responsiveness in B-ALL. In addition to previously identified deletions involving the CDKN2A/CDKN2B and ETV6 genes, we found deletions of tumor suppressors (RB1, PTEN, NF1, FHIT), the histone gene complex at 6p22, the Arf-induced antiproliferative gene and regulator of apoptosis BTG1 (57-59), the glucocorticoid and mineralocorticoid receptors NR3C1 and NR3C2 (60,61), ATM, the IL3RA and CSF2RA cytokine receptor genes at Xp, and mir-15/-16 microRNA gene cluster at 13q14.2. Many of these lesions have been confirmed by other groups in SNP array studies of both pediatric and adult ALL (62,63). Furthermore, while array-platforms typically cannot detect balanced translocations, several recurring translocations were observed to have microdeletions at the translocation breakpoints, including MLL and its partner genes, ETV6, RUNX1, BCR and ABL1. A striking finding was duplication of 1q from PBX1 to 1qtel in all cases of TCF3-PBX1 rearranged leukemia, and deletion of 19p from TCF3 (E2A) to 19ptel in the majority of cases.

Several recurring deletions were present in genes with less well characterized roles in leukemogenesis. These included deletions involving the BTLA, an inhibitor of T cell proliferation (64), and CD200, a putative lymphoid signaling molecule, overexpression of which is associated with poor prognosis in a number of malignancies (65); deletion of the thymocyte high mobility gene TOX, which is required for CD4+ T-cell development (66); deletion of the upstream region of the dystrophin gene DMD; deletion of TBL1XR1, a transcriptional repressor and putative mediator of Wnt pathway signaling (67); deletion of the adducin gene ADD3; and a deletion involving an uncharacterized transcript on chromosome 20, C20orf94.

We have also identified a focal deletion involving the ETS family member ERG that is uniquely observed in a novel subtype of B-precursor ALL; this subtype has a characteristic gene expression signature but lacks any previously identified cytogenetic or submicroscopic genetic alteration. This “novel” subtype of B-ALL was previously identified on gene expression profiling of pediatric ALL (18), and extensive efforts to identify a translocation involving overexpressed genes in the “novel” gene expression signature were unsuccessful. In an expanded SNP array and transcriptional profiling analysis of ALL, 12 of 16 novel ALL cases were found to have an internally truncating deletion of ERG that results in expression of a truncated C-terminal ERG protein (ref (68) and our unpublished data). ERG is required for normal hematopoiesis (69), and this mechanism of ERG dysregulation in ALL is in sharp contrast to the frequent translocations of this gene, and of other ETS family members, identified in carcinoma of the prostate (70).

Mechanism of deletion in ALL

Long-range PCR mapping and sequencing of the genomic breakpoints at sites of recurring CNAs in B-ALL has provided important insights into the mechanism responsible for the CNAs in ALL. By sequencing across the genomic regions of the breakpoints of the most common IKZF1 deletion (Δ3-6) in BCR-ABL1 B-ALL cases, we found that the proximal and distal breakpoints were extremely conserved, varying by only a few nucleotides, and had a pattern suggestion of aberrant activity of the recombinase activating genes, RAG1 and RAG2 (45). Specifically, heptamer and partially conserved nonamer RAG recognition sequences were present immediately internal to the IKZF1 deletion breakpoints, and extra non-consensus nucleotides were present between the breaks suggestive of the action of terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase (TdT)(45). This pattern has previously been observed for deletion of the CDKN2A/B locus in ALL (71). Multiple additional recurring CNAs in B-ALL have a similar RAG “footprint”, including PAX5, IKZF2 and IKZF3, ERG, C20orf94, BTLA/CD200, and ADD3 (our unpublished observations). Probably these deletions do not arise in hematopoietic stem cells, but instead originate in a lymphoid committed progenitor, at a stage of differentiation during which RAG1 and RAG2 are active.

Role of CNAs in B-ALL leukemogenesis

An important question is whether the identified CNAs play a mechanistic role in leukemogenesis (driver mutation), or represent background genetic “noise” (passenger mutation). Several observations suggest that the CNAs are biologically important. The average number of CNAs per ALL case is low, suggesting that this disease is not characterized by inherent genomic instability. Secondly, the majority of identified CNAs target small regions of the genome, frequently containing only a single gene in the minimal region of copy number alteration, and commonly involve genes with known or putative roles in oncogenesis. Moreover, in a study of matched diagnosis and relapse ALL samples, many of the lesions described above (of IKZF1, IKZF2, IKZF3, RAG, ADD3, CDKN2A, ETV6, BTG1, DMD, IL3RA/CSF2RA, as described above) emerge at relapse, suggesting that they confer a selective advantage and resistance to therapy in ALL (ref (72) and unpublished observations). Dissecting the relative contribution of each of these lesions to leukemogenesis in well-characterized experimental models will be crucial in order to select the most useful targets for potential novel therapeutic approaches. This task can be readily accomplished for single lesions or small numbers of lesions (modeling of Pax5 haploinsufficiency in murine models, as described above) but will prove more challenging for large numbers of lesions. Complementary syrategies - such as using pools of inhibitory RNAs directed against multiple genes targeted by CNAs - will be required and are being actively pursued.

Genome-wide profiling of T-lineage ALL

One of the first CNA studies in T-ALL used BAC CGH arrays and identified high-level amplification resulting in fusion of the NUP214 and ABL1 genes present on extrachromosomal episomes. The fusion of NUP214 to ABL1 results in constitutive activation of the kinase (73), and NUP214-ABL1 positive cell lines are responsive to tyrosine kinase inhibition, suggesting that these agents may be therapeutically useful in this type of leukemia. Using SNP, BAC, or oligo-array CGH platforms, we and others have identified multiple novel genomic aberrations in T-ALL, including focal deletions leading to dysregulated expression of TAL1(39) and LMO2 (74); deletions of the RB1 (39); deletion and mutation of PTEN (39,75,76); and deletion or mutation of the U3 ubiquitin ligase FBXW7 (75,77); duplications of the protooncogene MYB (39,78,79); and fusion of SET to NUP214 (80). T-ALL thus is genetically very heterogeneous, and studies examining all of these abnormalities in conjunction with detection of the known recurring chromosomal translocations and point mutations (such as NOTCH1 (16)) will be important to accurately classify T-ALL and examine associations with treatment response and clinical outcome.

Copy-neutral loss-of heterozygosity (acquired uniparental disomy) in ALL

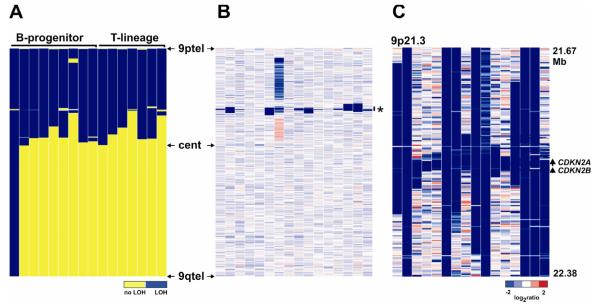

The identification of copy neutral LOH (CN-LOH) in tumor cells can indicate duplication of a gene within the region of LOH that has been altered by point mutations or epigenetic modification. Consequently accurate detection of CN-LOH is important to identify genes for subsequent mutation studies. For example, CN-LOH accompanying acquisition of homozygous mutations of FLT3 and CEBPA has been described in acute myeloid leukemia (81). We and others have reported recurring CN-LOH in ALL, most commonly involving chromosome 9p (39,62). The reported frequency of this type of lesion has varied significantly in published studies. Some investigators have reported that this is a common lesion in ALL, implying that there are frequent point mutations or epigenetic alterations of genes that are contained within the region of CN-LOH, which remain to be defined. Our own interpretation of the true frequency of CN-LOH is that this is a rare event in pediatric ALL. Specifically, in most large regions of CN-LOH the region of reduplication is not copy neutral but instead contains a focal deletion. The most prominent example occurs on chromosome 9/9p, where the region of CN-LOH almost always harbors a deletion of the CDKN2A/B locus (Figure 2). Deletion of CDKN2A/B on one allele is reduplicated to yield homozygous deletion. The extent of reduplication (region of CN-LOH) can vary from a small region around CDKN2A/B to the entire chromosome. The ability to detect focal deletions in regions of CN-LOH is critically dependent on array resolution. Many of the focal CDKN2A/B deletions identified in regions in CN-LOH in pediatric ALL are not evident using 100K SNP arrays but only detected with higher resolution arrays. Prior to commencing detailed mutational analyses of regions of CN-LOH, it is thus crucial to perform detailed analysis of high-resolution CNA data of the involved regions.

Figure 2.

Copy-neutral LOH in ALL. A, 16 pediatric ALL cases with copy neutral LOH involving chromosome 9. LOH is blue. B shows the corresponding copy number heatmap of chromosome 9 for the cases shown in A. The region shown in panel C is indicated by an asterisk. C, Affymetrix 615,000 SNP copy number status at 9p21.3 (the CDKN2A/B locus) for the same cases. Each case has a homozygous deletion that has been reduplicated, and is responsible for the flanking CN-LOH. Several of these deletions are not evident using lower resolution (50K) arrays.

Technical aspects of copy number profiling studies in leukemia

The results described above have transformed our understanding of the genetic basis of ALL, but our ability to accurately and comprehensively detect all regions of copy number alteration and LOH in cancer is critically dependent on the resolution and genomic coverage of the platform used, the selection of appropriate reference samples, and appropriate array normalization and careful CNA/LOH inference.

Array resolution

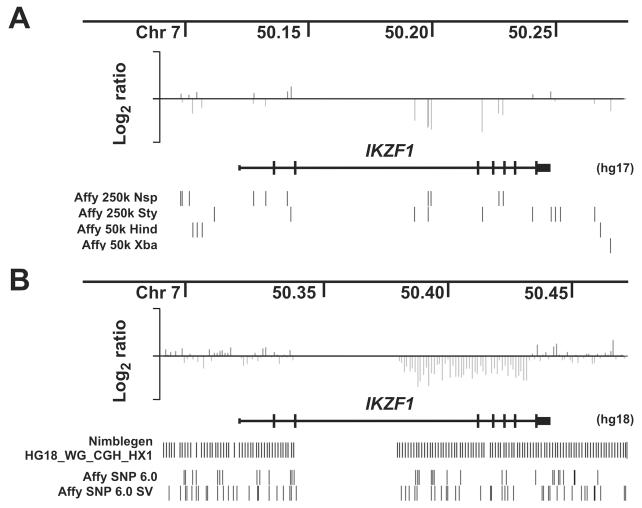

SNPs examined by the Affymetrix 50K and 250K SNP arrays have been selected according to a genetic rather than physical map, in order to optimize disease association/linkage studies. Consequently, the intermarker distance is far from uniform, and coverage of a many genes is suboptimal. With each added SNP array, we have detected more lesions in ALL (6.8 lesions per BCR-ABL1 case with 350,000 markers, compared with 8.8 lesions per case with 615,000 marker data)(39,45). The true frequency of somatic CNAs in ALL and the level of array resolution required to detect them are unknown. Several platforms are available that offer greater coverage. Affymetrix SNP 6.0 arrays have over 1.8 million markers, comprising both SNP probes and copy number variant (CNV) probes interrogating known inherited CNVs and markers spaced relatively evenly across the genome. Both SNP and CNV probes can be combined in CNA analysis to maximize resolution (our unpublished data). Other manufacturers (notably Illumina) also offer arrays that encompadss over 1 million SNP probes. Roche Nimblegen now offer arrays that contain over 2.1 million isothermal oligonucleotide probes that offer more even coverage (but no SNP genotype information). Genes such as IKZF1 that were poorly assessed by SNP arrays show greatly improved coverage on this platform (unpublished observations, Figure 3). In future, platforms that provide tiling coverage of the entire genome will become available, including multi-chip tiling arrays from Affymetrix (82) and Nimblegen (which will not detect SNP genotypes and thus cannot detect CN-LOH), and next generation sequencing approaches, which can simultaneously detect copy number, sequence mutations and SNP genotype (83).

Figure 3.

Effect of array resolution on lesion detection in ALL. A shows log ratio copy number data at the IKZF1 (Ikaros) locus in a case with a focal deletion of exons 3-6. Log ratio copy number at each SNP is shown as a vertical line. Only 7 probes cover the region of deletion. The sparse coverage of the gene by the 250k and 50k Affymetrix arrays is shown below the IKZF1 gene symbol, with each SNP on each array represented by a vertical line. Part of IKZF1 intron 2 has no coverage due to a gap in the human genome assembly. B, copy number data for the same case using a Nimblegen 2.1 million feature array CGH platform. Coverage by the Nimblegen and Affymetrix SNP 6.0 arrays are shown (SNP probes are labeled “Affy SNP 6.0”, and copy number probes on the same array is “Affy SNP 6.0 SV”).

Array normalization

All microarray data must be normalized in order to enable comparisons across samples. Many normalization algorithms are based on strategies used to normalize gene expression data, in which probes are selected for normalization without consideration of gross chromosomal abnormalities. However, if probes from aneuploid chromosomes guide normalization, the result may be an an incorrect assignment of the diploid state and erroneous copy number inferences. We employ reference normalization, which uses only probes from a defined reference set of diploid chromosomes to guide normalization; these can be selected from existing data (like cytogenetics) or by computational approaches (refs (39) and S.B. Pounds et al, submitted). Manual approaches to assign the correct diploid state for each sample are also available in other algorithms (examples are Chip (84), and CNAG (85)). As aneuploidy is a common feature of many cancers, appropriate normalization must be performed using one of these approaches in order to accurately detect CNAs.

Choice of reference samples

The choice of reference samples for CNA and UPD inference is critical. The ability to distinguish somatic, tumor-acquired lesions from inherited copy number polymorphisms (CNPs) is crucial, and the standard is to compare the tumor genome with the matched constitutional genome from the same individual. Constitutional DNA is not always available, and many studies have no choice but to compare tumor genomes with pools of unrelated reference samples. Databases of inherited CNPs are available to filter results from unpaired CNA analysis (86), but this method will always remain a compromise, as it is impossible to definitively distinguish a putative somatic CNA identified in an unpaired analysis from a rare private CNP. This feature is particularly problematic with newer, higher resolution arrays, which have a higher density of copy number probes (our unpublished observations). Wherever possible, paired normal tissue should be examined simultaneously with tumor samples.

LOH analysis

Paired normal genomes should also be used for accurate inference of LOH from SNP genotypes, in order to distinguish CN-LOH from inherited homozygosity. Algorithms are available that substantially reduce false calls of LOH by comparing tumor genotypes to pools of reference samples, but they again represent a compromise (87). For many studies, paired normal samples were not studied, and LOH results should then be interpreted with caution.

Other approaches to identify genomic abnormalities in ALL

Genome-wide techniques to characterize epigenetic changes (88), sequence mutations, and non-coding RNA expression are evolving rapidly, but thus far they have not been widely applied to ALL. Most investigations have focused on limited panels of individual genes. As with CNA/LOH analysis, it is likely that these techniques will provide insights into the pathogenesis of ALL. Several microarray platforms are available for studying epigenetic changes and microRNA expression, but as with gene expression and copy number arrays, they only interrogate those portions of the genome for which probes are available. The next generation of sequencing techniques offers the opportunity to examine copy number, sequence mutations, epigenetic phenomena, and gene expression in a genome-wide fashion (89). Although currently costly and challenging from a bioinformatic perspective, sequencing based approaches are likely to eventually supplant many of the microarray methodologies (90), and are likely to provide more important information about ALL biology.

Summary

The advent of high resolution genome-wide platforms to detect CNAs and regions of LOH, coupled with methods to accurately and quantitatively assess the total transcriptome of a leukemia cell have provided critical new insights into the pathogenesis of pediatric ALL. These data are defining key pathways required for cellular transformation and are highlighting combinations of lesions that appear to influence the response of the leukemia to our present therapeutic approaches. Over the next several years, as genome-wide approaches continue to improve in resolution, while decreasing in cost, it will be possible to accurately define all lesions within a cancer cell. Once this phase of the work is completed, we will then need to expend effort to determine which lesions are driver versus passenger mutations, identify the rational therapeutic targets among the driver mutations, and develop new therapy specifically target against these lesions. Although this remains a long hard road, then end should yield effective therapies with markedly reduced toxicities.

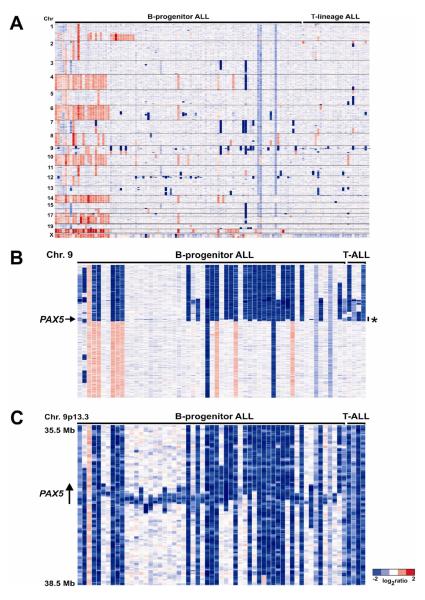

Figure 1.

A. Log2-ratio copy number heatmap of Affymetrix SNP array genome-wide copy number data obtained from 126 pediatric ALL cases. Blue is deletion, red is gain. B, Copy number heatmap of 61 pediatric ALL cases with CNAs involving PAX5 at 9p13.2. Many cases are not identifiable at this whole-chromosome resolution. The region shown in panel C is indicated by an asterisk. C, copy number status at PAX5 for the 61 cases shown in B.

Acknowledgments

Supported in Part by Grants from the Haematology Society of Australasia, The Royal Australasian College of Physicians, the National Health and Medical Research Council (Australia) and the American Lebanese and Syrian Associated Charities of St Jude Children’s Research Hospital.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Contributor Information

Charles G. Mullighan, Pathology St Jude Children’s Research Hospital 262 Danny Thomas Place Memphis, TN, 38105.

James R Downing, St Jude Children’s Research Hospital 262 Danny Thomas Place Memphis, TN, 38105.

REFERENCES

- 1.Pui CH, Robison LL, Look AT. Acute lymphoblastic leukaemia. Lancet. 2008;371:1030–1043. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)60457-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pui CH, Sandlund JT, Pei D, Campana D, Rivera GK, Ribeiro RC, et al. Improved outcome for children with acute lymphoblastic leukemia: results of Total Therapy Study XIIIB at St Jude Children’s Research Hospital. Blood. 2004;104:2690–2696. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-04-1616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fielding AK, Richards SM, Chopra R, Lazarus HM, Litzow MR, Buck G, et al. Outcome of 609 adults after relapse of acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL); an MRC UKALL12/ECOG 2993 study. Blood. 2007;109:944–950. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-05-018192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rowe JM, Buck G, Burnett AK, Chopra R, Wiernik PH, Richards SM, et al. Induction therapy for adults with acute lymphoblastic leukemia: results of more than 1500 patients from the international ALL trial: MRC UKALL XII/ECOG E2993. Blood. 2005;106:3760–3767. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-04-1623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pui CH, Relling MV, Downing JR. Acute lymphoblastic leukemia. N Engl J Med. 2004;350:1535–1548. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra023001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Harrison CJ, Foroni L. Cytogenetics and molecular genetics of acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Rev Clin Exp Hematol. 2002;6:91–113. doi: 10.1046/j.1468-0734.2002.00069.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Raimondi SC. Cytogenetics of acute leukemias. In: Pui CH, editor. Childhood Leukemias. 2nd ed Cambridge University Press; Cambridge: 2006. pp. 235–271. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Graux C, Cools J, Michaux L, Vandenberghe P, Hagemeijer A. Cytogenetics and molecular genetics of T-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia: from thymocyte to lymphoblast. Leukemia. 2006;20:1496–1510. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2404302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Greaves MF, Wiemels J. Origins of chromosome translocations in childhood leukaemia. Nat Rev Cancer. 2003;3:639–649. doi: 10.1038/nrc1164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Andreasson P, Schwaller J, Anastasiadou E, Aster J, Gilliland DG. The expression of ETV6/CBFA2 (TEL/AML1) is not sufficient for the transformation of hematopoietic cell lines in vitro or the induction of hematologic disease in vivo. Cancer Genet Cytogenet. 2001;130:93–104. doi: 10.1016/s0165-4608(01)00518-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Williams RT, Roussel MF, Sherr CJ. Arf gene loss enhances oncogenicity and limits imatinib response in mouse models of Bcr-Abl-induced acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:6688–6693. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0602030103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Moorman AV, Harrison CJ, Buck GA, Richards SM, Secker-Walker LM, Martineau M, et al. Karyotype is an independent prognostic factor in adult acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL): analysis of cytogenetic data from patients treated on the Medical Research Council (MRC) UKALLXII/Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) 2993 trial. Blood. 2007;109:3189–3197. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-10-051912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hebert J, Cayuela JM, Berkeley J, Sigaux F. Candidate tumor-suppressor genes MTS1 (p16INK4A) and MTS2 (p15INK4B) display frequent homozygous deletions in primary cells from T- but not from B-cell lineage acute lymphoblastic leukemias. Blood. 1994;84:4038–4044. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ogawa S, Hangaishi A, Miyawaki S, Hirosawa S, Miura Y, Takeyama K, et al. Loss of the cyclin-dependent kinase 4-inhibitor (p16; MTS1) gene is frequent in and highly specific to lymphoid tumors in primary human hematopoietic malignancies. Blood. 1995;86:1548–1556. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Okuda T, Shurtleff SA, Valentine MB, Raimondi SC, Head DR, Behm F, et al. Frequent deletion of p16INK4a/MTS1 and p15INK4b/MTS2 in pediatric acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Blood. 1995;85:2321–2330. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Weng AP, Ferrando AA, Lee W, Morris JPt, Silverman LB, Sanchez-Irizarry C, et al. Activating mutations of NOTCH1 in human T cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Science. 2004;306:269–271. doi: 10.1126/science.1102160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Golub TR, Slonim DK, Tamayo P, Huard C, Gaasenbeek M, Mesirov JP, et al. Molecular classification of cancer: class discovery and class prediction by gene expression monitoring. Science. 1999;286:531–537. doi: 10.1126/science.286.5439.531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yeoh EJ, Ross ME, Shurtleff SA, Williams WK, Patel D, Mahfouz R, et al. Classification, subtype discovery, and prediction of outcome in pediatric acute lymphoblastic leukemia by gene expression profiling. Cancer Cell. 2002;1:133–143. doi: 10.1016/s1535-6108(02)00032-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Huhta T, Vettenranta K, Heinonen K, Kanerva J, Larramendy ML, Mahlamaki E, et al. Comparative genomic hybridization and conventional cytogenetic analyses in childhood acute myeloid leukemia. Leuk Lymphoma. 1999;35:311–315. doi: 10.3109/10428199909145735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jalali GR, An Q, Konn ZJ, Worley H, Wright SL, Harrison CJ, et al. Disruption of ETV6 in intron 2 results in upregulatory and insertional events in childhood acute lymphoblastic leukaemia. Leukemia. 2008;22:114–123. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2404994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kuchinskaya E, Heyman M, Nordgren A, Schoumans J, Staaf J, Borg A, et al. Array-CGH reveals hidden gene dose changes in children with acute lymphoblastic leukaemia and a normal or failed karyotype by G-banding. Br J Haematol. 2008;140:572–577. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2007.06917.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kuchinskaya E, Nordgren A, Heyman M, Schoumans J, Corcoran M, Staaf J, et al. Tiling-resolution array-CGH reveals the pattern of DNA copy number alterations in acute lymphoblastic leukemia with 21q amplification: the result of telomere dysfunction and breakage/fusion/breakage cycles? Leukemia. 2007;21:1327–1330. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2404628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Larramendy ML, Huhta T, Heinonen K, Vettenranta K, Mahlamaki E, Riikonen P, et al. DNA copy number changes in childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Haematologica. 1998;83:890–895. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Larramendy ML, Huhta T, Vettenranta K, El-Rifai W, Lundin J, Pakkala S, et al. Comparative genomic hybridization in childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Leukemia. 1998;12:1638–1644. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2401142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lundin C, Heidenblad M, Strombeck B, Borg A, Hovland R, Heim S, et al. Tiling resolution array CGH of dic(7;9)(p11 approximately 13;p11 approximately 13) in B-cell precursor acute lymphoblastic leukemia reveals clustered breakpoints at 7p11.2 approximately 12.1 and 9p13.1. Cytogenet Genome Res. 2007;118:13–18. doi: 10.1159/000106436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rabin KR, Man TK, Yu A, Folsom MR, Zhao YJ, Rao PH, et al. Clinical utility of array comparative genomic hybridization for detection of chromosomal abnormalities in pediatric acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2008;51:171–177. doi: 10.1002/pbc.21488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Schoumans J, Johansson B, Corcoran M, Kuchinskaya E, Golovleva I, Grander D, et al. Characterisation of dic(9;20)(p11-13;q11) in childhood B-cell precursor acute lymphoblastic leukaemia by tiling resolution array-based comparative genomic hybridisation reveals clustered breakpoints at 9p13.2 and 20q11.2. Br J Haematol. 2006;135:492–499. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2006.06328.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Steinemann D, Cario G, Stanulla M, Karawajew L, Tauscher M, Weigmann A, et al. Copy number alterations in childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia and their association with minimal residual disease. Genes Chromosomes Cancer. 2008;47:471–480. doi: 10.1002/gcc.20557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Strefford JC, van Delft FW, Robinson HM, Worley H, Yiannikouris O, Selzer R, et al. Complex genomic alterations and gene expression in acute lymphoblastic leukemia with intrachromosomal amplification of chromosome 21. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:8167–8172. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0602360103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Strefford JC, Worley H, Barber K, Wright S, Stewart AR, Robinson HM, et al. Genome complexity in acute lymphoblastic leukemia is revealed by array-based comparative genomic hybridization. Oncogene. 2007;26:4306–4318. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1210190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.van Vlierberghe P, Meijerink JP, Lee C, Ferrando AA, Look AT, van Wering ER, et al. A new recurrent 9q34 duplication in pediatric T-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Leukemia. 2006;20:1245–1253. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2404247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pinkel D, Albertson DG. Comparative genomic hybridization. Annu Rev Genomics Hum Genet. 2005;6:331–354. doi: 10.1146/annurev.genom.6.080604.162140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Davidsson J, Andersson A, Paulsson K, Heidenblad M, Isaksson M, Borg A, et al. Tiling resolution array comparative genomic hybridization, expression and methylation analyses of dup(1q) in Burkitt lymphomas and pediatric high hyperdiploid acute lymphoblastic leukemias reveal clustered near-centromeric breakpoints and overexpression of genes in 1q22-32.3. Hum Mol Genet. 2007;16:2215–2225. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddm173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Balgobind BV, Van Vlierberghe P, van den Ouweland AM, Beverloo HB, Terlouw-Kromosoeto JN, van Wering ER, et al. Leukemia-associated NF1 inactivation in patients with pediatric T-ALL and AML lacking evidence for neurofibromatosis. Blood. 2008;111:4322–4328. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-06-095075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gandemer V, Rio AG, de Tayrac M, Sibut V, Mottier S, Ly Sunnaram B, et al. Five distinct biological processes and 14 differentially expressed genes characterize TEL/AML1-positive leukemia. BMC Genomics. 2007;8:385. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-8-385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Usvasalo A, Savola S, Raty R, Vettenranta K, Harila-Saari A, Koistinen P, et al. CDKN2A deletions in acute lymphoblastic leukemia of adolescents and young adults: an array CGH study. Leuk Res. 2008;32:1228–1235. doi: 10.1016/j.leukres.2008.01.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Frazer KA, Ballinger DG, Cox DR, Hinds DA, Stuve LL, Gibbs RA, et al. A second generation human haplotype map of over 3.1 million SNPs. Nature. 2007;449:851–861. doi: 10.1038/nature06258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Irving JA, Bloodworth L, Bown NP, Case MC, Hogarth LA, Hall AG. Loss of heterozygosity in childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia detected by genome-wide microarray single nucleotide polymorphism analysis. Cancer Res. 2005;65:3053–3058. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-2604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mullighan CG, Goorha S, Radtke I, Miller CB, Coustan-Smith E, Dalton JD, et al. Genome-wide analysis of genetic alterations in acute lymphoblastic leukaemia. Nature. 2007;446:758–764. doi: 10.1038/nature05690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Olshen AB, Venkatraman ES, Lucito R, Wigler M. Circular binary segmentation for the analysis of array-based DNA copy number data. Biostatistics. 2004;5:557–572. doi: 10.1093/biostatistics/kxh008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kwon K, Hutter C, Sun Q, Bilic I, Cobaleda C, Malin S, et al. Instructive role of the transcription factor E2A in early B lymphopoiesis and germinal center B cell development. Immunity. 2008;28:751–762. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2008.04.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Nutt SL, Kee BL. The transcriptional regulation of B cell lineage commitment. Immunity. 2007;26:715–725. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2007.05.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Cazzaniga G, Daniotti M, Tosi S, Giudici G, Aloisi A, Pogliani E, et al. The paired box domain gene PAX5 is fused to ETV6/TEL in an acute lymphoblastic leukemia case. Cancer Res. 2001;61:4666–4670. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Mullighan CG, Su X, Ma J, Yang W, Relling MV, Carroll WL, et al. Genome-Wide Profiling of High-Risk Pediatric Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia (ALL): The ALL Pilot Project for the Therapeutically Applicable Research To Generate Effective Treatments (TARGET) Initiative. Blood (ASH Annual Meeting Abstracts) 2007;110:229. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Mullighan CG, Miller CB, Phillips LA, Dalton JD, Ma J, Radtke I, et al. BCR-ABL1 lymphoblastic leukaemia is characterized by the deletion of Ikaros. Nature. 2008;453:110–114. doi: 10.1038/nature06866. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Reynaud D, I AD, K LR, Schjerven H, Bertolino E, Chen Z, et al. Regulation of B cell fate commitment and immunoglobulin heavy-chain gene rearrangements by Ikaros. Nat Immunol. 2008 doi: 10.1038/ni.1626. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Georgopoulos K, Bigby M, Wang JH, Molnar A, Wu P, Winandy S, et al. The Ikaros gene is required for the development of all lymphoid lineages. Cell. 1994;79:143–156. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90407-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Winandy S, Wu P, Georgopoulos K. A dominant mutation in the Ikaros gene leads to rapid development of leukemia and lymphoma. Cell. 1995;83:289–299. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90170-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Sun L, Crotty ML, Sensel M, Sather H, Navara C, Nachman J, et al. Expression of dominant-negative Ikaros isoforms in T-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Clin Cancer Res. 1999;5:2112–2120. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Sun L, Goodman PA, Wood CM, Crotty ML, Sensel M, Sather H, et al. Expression of aberrantly spliced oncogenic ikaros isoforms in childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia. J Clin Oncol. 1999;17:3753–3766. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1999.17.12.3753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Sun L, Heerema N, Crotty L, Wu X, Navara C, Vassilev A, et al. Expression of dominant-negative and mutant isoforms of the antileukemic transcription factor Ikaros in infant acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1999;96:680–685. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.2.680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Nakase K, Ishimaru F, Avitahl N, Dansako H, Matsuo K, Fujii K, et al. Dominant negative isoform of the Ikaros gene in patients with adult B-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Cancer Res. 2000;60:4062–4065. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Nishii K, Kita K, Miwa H, Shikami M, Taniguchi M, Usui E, et al. Expression of B cell-associated transcription factors in B-cell precursor acute lymphoblastic leukemia cells: association with PU.1 expression, phenotype, and immunogenotype. Int J Hematol. 2000;71:372–378. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Olivero S, Maroc C, Beillard E, Gabert J, Nietfeld W, Chabannon C, et al. Detection of different Ikaros isoforms in human leukaemias using real-time quantitative polymerase chain reaction. Br J Haematol. 2000;110:826–830. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2141.2000.02297.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Takanashi M, Yagi T, Imamura T, Tabata Y, Morimoto A, Hibi S, et al. Expression of the Ikaros gene family in childhood acute lymphoblastic leukaemia. Br J Haematol. 2002;117:525–530. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2141.2002.03487.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Mullighan CG, Williams RT, Downing JR, Sherr CJ. Failure of CDKN2A/B (INK4A/B-ARF)-mediated tumor suppression and resistance to targeted therapy in acute lymphoblastic leukemia induced by BCR-ABL. Genes Dev. 2008;22:1411–1415. doi: 10.1101/gad.1673908. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Kolbus A, Blazquez-Domingo M, Carotta S, Bakker W, Luedemann S, von Lindern M, et al. Cooperative signaling between cytokine receptors and the glucocorticoid receptor in the expansion of erythroid progenitors: molecular analysis by expression profiling. Blood. 2003;102:3136–3146. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-03-0923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Lee H, Cha S, Lee MS, Cho GJ, Choi WS, Suk K. Role of antiproliferative B cell translocation gene-1 as an apoptotic sensitizer in activation-induced cell death of brain microglia. J Immunol. 2003;171:5802–5811. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.171.11.5802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Rouault JP, Rimokh R, Tessa C, Paranhos G, Ffrench M, Duret L, et al. BTG1, a member of a new family of antiproliferative genes. EMBO J. 1992;11:1663–1670. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1992.tb05213.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Bray PJ, Cotton RG. Variations of the human glucocorticoid receptor gene (NR3C1): pathological and in vitro mutations and polymorphisms. Hum Mutat. 2003;21:557–568. doi: 10.1002/humu.10213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Kino T, Chrousos GP. Glucocorticoid and mineralocorticoid receptors and associated diseases. Essays Biochem. 2004;40:137–155. doi: 10.1042/bse0400137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Kawamata N, Ogawa S, Zimmermann M, Kato M, Sanada M, Hemminki K, et al. Molecular allelokaryotyping of pediatric acute lymphoblastic leukemias by high-resolution single nucleotide polymorphism oligonucleotide genomic microarray. Blood. 2008;111:776–784. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-05-088310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Paulsson K, Cazier JB, Macdougall F, Stevens J, Stasevich I, Vrcelj N, et al. Microdeletions are a general feature of adult and adolescent acute lymphoblastic leukemia: Unexpected similarities with pediatric disease. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:6708–6713. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0800408105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Kaye J. CD160 and BTLA: LIGHTs out for CD4+ T cells. Nat Immunol. 2008;9:122–124. doi: 10.1038/ni0208-122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Moreaux J, Veyrune JL, Reme T, De Vos J, Klein B. CD200: a putative therapeutic target in cancer. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2008;366:117–122. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2007.11.103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Aliahmad P, Kaye J. Development of all CD4 T lineages requires nuclear factor TOX. J Exp Med. 2008;205:245–256. doi: 10.1084/jem.20071944. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Li J, Wang CY. TBL1-TBLR1 and beta-catenin recruit each other to Wnt target-gene promoter for transcription activation and oncogenesis. Nat Cell Biol. 2008;10:160–169. doi: 10.1038/ncb1684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Mullighan CG, Miller CB, Su X, Radtke I, Dalton JD, Song G, et al. ERG Deletions Define a Novel Subtype of B-Progenitor Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia. Blood (ASH Annual Meeting Abstracts) 2007;110:691. [Google Scholar]

- 69.Loughran SJ, Kruse EA, Hacking DF, de Graaf CA, Hyland CD, Willson TA, et al. The transcription factor Erg is essential for definitive hematopoiesis and the function of adult hematopoietic stem cells. Nat Immunol. 2008;9:810–819. doi: 10.1038/ni.1617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Tomlins SA, Rhodes DR, Perner S, Dhanasekaran SM, Mehra R, Sun XW, et al. Recurrent fusion of TMPRSS2 and ETS transcription factor genes in prostate cancer. Science. 2005;310:644–648. doi: 10.1126/science.1117679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Kitagawa Y, Inoue K, Sasaki S, Hayashi Y, Matsuo Y, Lieber MR, et al. Prevalent involvement of illegitimate V(D)J recombination in chromosome 9p21 deletions in lymphoid leukemia. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:46289–46297. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M208353200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Mullighan CG, Radtke I, Ma J, Shurtleff SA, Downing JR. High-Resolution SNP Array Profiling of Relapsed Acute Leukemia Identifies Genomic Abnormalities Distinct from Those Present at Diagnosis. Blood (ASH Annual Meeting Abstracts) 2007;110:234. [Google Scholar]

- 73.Graux C, Cools J, Melotte C, Quentmeier H, Ferrando A, Levine R, et al. Fusion of NUP214 to ABL1 on amplified episomes in T-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Nat Genet. 2004;36:1084–1089. doi: 10.1038/ng1425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Van Vlierberghe P, van Grotel M, Beverloo HB, Lee C, Helgason T, Buijs-Gladdines J, et al. The cryptic chromosomal deletion del(11)(p12p13) as a new activation mechanism of LMO2 in pediatric T-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Blood. 2006;108:3520–3529. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-04-019927. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Maser RS, Choudhury B, Campbell PJ, Feng B, Wong KK, Protopopov A, et al. Chromosomally unstable mouse tumours have genomic alterations similar to diverse human cancers. Nature. 2007;447:966–971. doi: 10.1038/nature05886. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Palomero T, Sulis ML, Cortina M, Real PJ, Barnes K, Ciofani M, et al. Mutational loss of PTEN induces resistance to NOTCH1 inhibition in T-cell leukemia. Nat Med. 2007;13:1203–1210. doi: 10.1038/nm1636. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.O’Neil J, Grim J, Strack P, Rao S, Tibbitts D, Winter C, et al. FBW7 mutations in leukemic cells mediate NOTCH pathway activation and resistance to gamma-secretase inhibitors. J Exp Med. 2007;204:1813–1824. doi: 10.1084/jem.20070876. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Clappier E, Cuccuini W, Kalota A, Crinquette A, Cayuela JM, Dik WA, et al. The C-MYB locus is involved in chromosomal translocation and genomic duplications in human T-cell acute leukemia (T-ALL), the translocation defining a new T-ALL subtype in very young children. Blood. 2007;110:1251–1261. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-12-064683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Lahortiga I, De Keersmaecker K, Van Vlierberghe P, Graux C, Cauwelier B, Lambert F, et al. Duplication of the MYB oncogene in T cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Nat Genet. 2007;39:593–595. doi: 10.1038/ng2025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Van Vlierberghe P, van Grotel M, Tchinda J, Lee C, Beverloo HB, van der Spek PJ, et al. The recurrent SET-NUP214 fusion as a new HOXA activation mechanism in pediatric T- cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Blood. 2008;111:4668–4680. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-09-111872. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Raghavan M, Smith LL, Lillington DM, Chaplin T, Kakkas I, Molloy G, et al. Segmental uniparental disomy is a commonly acquired genetic event in relapsed acute myeloid leukemia. Blood. 2008 doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-01-132431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Emerson JJ, Cardoso-Moreira M, Borevitz JO, Long M. Natural selection shapes genome-wide patterns of copy-number polymorphism in Drosophila melanogaster. Science. 2008;320:1629–1631. doi: 10.1126/science.1158078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Campbell PJ, Stephens PJ, Pleasance ED, O’Meara S, Li H, Santarius T, et al. Identification of somatically acquired rearrangements in cancer using genome-wide massively parallel paired-end sequencing. Nat Genet. 2008;40:722–729. doi: 10.1038/ng.128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Lin M, Wei LJ, Sellers WR, Lieberfarb M, Wong WH, Li C. dChipSNP: significance curve and clustering of SNP-array-based loss-of-heterozygosity data. Bioinformatics. 2004;20:1233–1240. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bth069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Nannya Y, Sanada M, Nakazaki K, Hosoya N, Wang L, Hangaishi A, et al. A robust algorithm for copy number detection using high-density oligonucleotide single nucleotide polymorphism genotyping arrays. Cancer Res. 2005;65:6071–6079. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-0465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Iafrate AJ, Feuk L, Rivera MN, Listewnik ML, Donahoe PK, Qi Y, et al. Detection of large-scale variation in the human genome. Nat Genet. 2004;36:949–951. doi: 10.1038/ng1416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Beroukhim R, Lin M, Park Y, Hao K, Zhao X, Garraway LA, et al. Inferring loss-of-heterozygosity from unpaired tumors using high-density oligonucleotide SNP arrays. PLoS Comput Biol. 2006;2:e41. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.0020041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Esteller M. Cancer epigenomics: DNA methylomes and histone-modification maps. Nat Rev Genet. 2007;8:286–298. doi: 10.1038/nrg2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Mortazavi A, Williams BA, McCue K, Schaeffer L, Wold B. Mapping and quantifying mammalian transcriptomes by RNA-Seq. Nat Methods. 2008;5:621–628. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Shendure J. The beginning of the end for microarrays? Nat Methods. 2008;5:585–587. doi: 10.1038/nmeth0708-585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]