Abstract

Severe grief symptoms, treatment receptivity, attitudes about grief, and stigmatization concerns were assessed in a community-based sample of 135 widowed participants in the Yale Bereavement Study. There was a statistically significant association between the severity of grief symptoms and reported negative reactions from friends and family members. However, more than 90% of the respondents with Complicated Grief, a severe grief disorder, reported that they would be relieved to know that having such a diagnosis was indicative of a recognizable psychiatric condition, and 100% reported that they would be interested in receiving treatment for their severe grief symptoms.

In recent years, a cluster of symptoms referred to as Complicated Grief (CG)1 has been identified by Prigerson and colleagues (Boelen, van den Bout & de Keijser, 2003; Ogrodniczuk et al., 2003; Prigerson et al., 1995; Prigerson et al., 1996; Prigerson & Jacobs, 2001). Symptoms of CG include distressing and disruptive levels of yearning for the deceased, an inability to accept the death, feeling detached from others, being on edge since the death, feeling that one’s current life and future life have no purpose or meaning, experiencing bitterness over the loss, and having difficulty moving on with one’s life. These symptoms constitute a clinical syndrome that as been found to be distinct from other psychiatric disorders with respect to clinical phenomenology, etiology/correlates, clinical course, and response to treatment (Boelen et al., 2003; Ogrodniczuk et al., 2003; Prigerson et al., 1995; Prigerson et al., 1996; Prigerson & Jacobs, 2001). High CG symptom levels and a CG diagnosis have been associated with the onset of illnesses such as cancer, hypertension, and cardiac illness, suicidal ideation, reduced quality of life, and increased risk for hospitalization, even after controlling for other disorders such as Major Depression (Melhem et al., 2004; Ott, 2003; Prigerson et al., 1997; Prigerson et al., 1999; Silverman et al., 2000; Prigerson et al., 2002). These findings support the inference that CG is distinct from established psychiatric disorders such as Major Depressive Disorder. There is considerable evidence indicating that CG merits consideration for inclusion in the next edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (APA, 2000). Research has suggested that psychotherapeutic interventions designed to target grief symptoms may be helpful in the treatment of CG (Hensley, 2006).

However, some concerns have been raised regarding the proposal to include CG in DSM-V. Some investigators have expressed the concern that if CG were recognized as a disorder, those receiving a CG diagnosis would be stigmatized (Stroebe, Schut, & Finkenauer, 2001; Stroebe et al., 2001). It has been suggested that a CG diagnosis might be demoralizing or that it might have an adverse effect on self-esteem by labeling some bereaved individuals as mentally ill, subjecting them to potential castigation by others, and limiting the natural inclinations of friends and family members to provide support and assistance. However, it is also possible that a CG diagnosis might confer several advantages. A CG diagnosis might promote understanding of the bereaved person’s distress, reduce self-blame for being unable to “move on with one’s life,” and aid in the development of effective treatments designed to reduce distress and impairment. Another benefit of a CG diagnosis is that it might help those experiencing CG to understand that they are not alone in their suffering. CG tends to be associated with a heightened sense of isolation and alienation (Prigerson et al., 1997) and persons with CG might find it especially consoling to know that there are other individuals like themselves who experience severe reactions to grief. To date, however, the reactions of bereaved individuals to being diagnosed with CG have not yet been examined.

Moreover, there have been no published findings regarding attitudes about grief symptoms, receptivity to treatment, or concerns about stigmatization among bereaved individuals. The present study was conducted to investigate perceptions of stigmatization among widowed individuals in the community, their reactions and expectations regarding a CG diagnosis, and their receptivity to treatment for their grief-related distress. Based on findings indicating that persistent depressive symptoms may be associated with concerns about negative reactions from others (Angermeyer, Beck, Dietrich, & Holzinger, 2004), it was hypothesized that severe and persistent grief symptoms would be associated with concerns about stigmatization. The hypothesis that a diagnosis of CG would be associated with concerns about stigmatization (Stroebe et al., 2001) was also investigated.

Method

Participants and Procedure

The participants in the present study were 135 adults who completed assessments of CG and attitudes about grief during their participation in the Yale Bereavement Study (YBS), a three-wave prospective longitudinal investigation (Chen, Gill, & Prigerson, 2005). Recruitment for the YBS began by obtaining names of recently bereaved (1–3 months post-loss) persons residing in the AARP Widowed Persons Service (WPS) Bridgeport/Fairfield catchment area. Additional names were obtained from obituaries from the New Haven Register, a major regional newspaper, and through newspaper advertisements, flyers, personal referrals and referrals from the Chaplain’s Office of the Hospital of St. Raphael in New Haven. Seventy-six percent of study participants were recruited through the WPS and remaining participants (24.0%) were recruited through these other sources. Participants recruited from these sources did not differ significantly from WPS participants with respect to sex, income, or quality of life, but they were significantly older than WPS participants (p<0.01), with a mean age of 70.0 years (SD=9.6).

Of the 575 persons who were contacted by the study team, 317 (55.1%) agreed to participate. Reasons for non-participation included reporting general reluctance to participate in research studies (N=11; 4.3%); being too busy to participate (N=46; 17.8%); being too upset (N=27; 10.5%); "doing fine" (N=23; 8.9%); not being interested or having "no reason" (N=145; 56.2%); and "other" reasons (N=6; 2.3%). The non-participants were significantly more likely to be male (37.2% vs. 25.9%, p=.0005) and older (mean age= 68.8 years vs. 61.7 years, p<.0001) than participants.

The 317 respondents who met the eligibility criteria and agreed to participate were interviewed at an average of 7.2 (SD=6.9) months after the death of the deceased persons (Wave 1). First follow-up (i.e, Wave 2) interviews were completed an average of 12.0 months (SD=7.1) after the loss of the deceased persons. Wave 3 interviews were conducted at an average of 19.8 (SD=6.6) months post-loss. Wave 3 assessments were completed by 265 individuals (83.6% of those who completed Wave 1). Because the Stigma Receptivity Scale (SRS) was a late addition to the original interview and was added after the study had begun, it was only administered to the final 135 of the 265 (50.9%) participants in the third wave of the YBS. The characteristics of this sample of 135 participants are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Sample characteristics (N=135).

| Variable | % (n) or Mean (SD) |

Without Complicated Grief Disorder (N=119) % (n) |

With Complicated Grief Disorder (N=16) % (n) |

Statistical Comparison | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Statistical Test |

df | p | ||||

| Gender | FET a | ---- a | 0.19 | |||

| • Male | 20.0% (27) | 22.0% (26) | 6.3% (1) | |||

| • Female | 80.0% (108) | 78.0% (108) | 93.8% (15) | |||

| Ethnicity | χ2=0.9 b | 2 | 0.63 | |||

| • White | 95.5% (129) | 95.8% (114) | 93.8% (15) | |||

| • Black | 3.0% (4) | 2.5% (3) | 6.3% (1) | |||

| • Hispanic | 1.5% (2) | 1.68% (2) | 0.0% (0) | |||

| Relationship to the Deceased Person |

χ2=1.3 b | 3 | 0.74 | |||

| • Spouse | 80% (108) | 79.0% (94) | 87.5% (14) | |||

| • Child | 5.2% (7) | 5.0% (6) | 6.3% (1) | |||

| • Parent | 10.4% (14) | 10.9% (13) | 6.3% (1) | |||

| • Sibling | 4.4% (6) | 5.0% (6) | 0.0% (0) | |||

| Age (years) | 61.8 (13.7) | 62.04 (13.8) | 62.3 (8.9%) | t= −0.08 | 130 | 0.94 |

| Education (years) | 14.0 (3.0) | 14.27 (2.9) | 13.3 (2.2%) | t= 1.3 | 132 | 0.20 |

| Time Since Death (days) | 19.8 (6.6) | 19.9 (6.3) | 19.8 (6.7) | W=1051.5 c | ---- | 0.81 |

Because the expected cell number is <5, Fisher’s exact test (FET) was conducted.

Because the expected cell number is <5, Cochran Mantel-Haenszel test was conducted.

Because the time to death variable is highly skewed (skewness>2), non-parametric Wilcoxon rank sum test (W) was conducted. Wilcoxon statistic and associated p-value were reported.

Most (90%) of respondents were interviewed in person within their home, the remaining 10% were interviewed at the YBS office in New Haven, CT. Interviews lasted 2 to 3 hours, and were conducted by Master's-level interviewers, each of whom received extensive training regarding interviewing procedures by the Principal Investigator (HGP) and the project director. The training continued until the interviewers were capable of performing valid and reliable assessments. Interviewers were required to demonstrate perfect or nearly perfect agreement (kappa ≥ 0.90) with the Principal Investigator (HGP) with regard to their diagnosis of CG in a series of 5 pilot interviews before they were permitted to conduct interviews for the study.

Assessment of Complicated Grief

Complicated Grief was assessed using the validated rater-administered version of the Inventory of Complicated Grief-Revised (ICG-R; Prigerson & Jacobs, 2001), a 37-item questionnaire that assesses symptoms of normal and complicated grief, using a 5-point response scale ranging from “never” (0) to “always” (4). The ICG-R, a revised version of the validated Inventory of Complicated Grief (Prigerson et al., 1995), assesses the symptoms of separation distress and traumatic distress that have been validated as the diagnostic criteria for CG (Prigerson et al.,1999). Inter-rater agreement on CG diagnoses in the present study was perfect (kappa = 1.00). Grief-related distress scores were computed by summing ICG-R items.

Assessment of Attitudes about Grief, Treatment Receptivity, and Stigmatization Concerns

Attitudes about grief, receptivity to treatment, and concerns about stigmatization were assessed using the Stigma Receptivity Scale (SRS). The SRS is an 18-item self-report questionnaire that was developed by the YBS investigators to assess attitudes about severe grief, receptivity to mental health interventions and stigmatization due to bereavement-related distress (Bambauer & Prigerson, 2006). The SRS items, which are presented in the tables below, demonstrated satisfactory inter-item reliability (Cronbach's alpha (α) = 0.64). The response format for each item was dichotomous (e.g, "yes" or "no"). There are 3 SRS sub-scales. One SRS subscale (5 items; α =0.45) assesses attitudes and feelings about the severity of grief symptoms (see Table 2). The second subscale (6 items; α =0.52) assesses receptivity to treatment for a mental disorder, and then to 4 common types of bereavement interventions (see Table 3). The third subscale (7 items; α =0.69) assesses the reactions that the respondents would expect from others, given a CG diagnosis, and also assesses how friends and family members have responded to their grief symptoms (see Table 4). SRS sub-scale scores were computed by summing the number of affirmative and reverse-coded responses for each SRS sub-scale.

Table 2.

Attitudes and feelings about diagnosis of a grief disorder among bereaved individuals with or without complicated grief (N=135).

| Response Indicative of Positive Attitudes and Feelings about the Diagnosis of Complicated Grief among Bereaved Individuals |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Attitudes and Feelings about Identification of Grief Symptoms | Total Sample (N=135) % (n) |

Without Complicated Grief Disorder (N=119) % (n) |

With Complicated Grief Disorder (N=16) % (n) |

Adjusteda Odds Ratio (95% C.I.) |

| "Considering your current bereavement related distress, would you feel better knowing you had a mental condition for which effective treatment is available, rather than being told you were normal and that there was no need for any outside intervention to help you?" |

71.8% (97) | 73.1% (87) | 62.5% (10) | 0.7 (0.2–2.2) |

| "If a mental health professional told you that you met criteria for Complicated Grief (a complex of symptoms indicating difficult adjustment to the death of someone close), would you be:" |

||||

| • "relieved to know you were not going crazy?" | 96.3% (130) | 97.5% (116) | 87.5% (14) | 0.1 (0.2–1.0) |

| • "relieved to know you had a recognizable problem? " | 96.3% (130) | 96.6% (115) | 93.8% (15) | 0.4 (0.0–4.3) |

| • "(not) worried because you would not take this to mean you were going crazy?"b |

87.4% (118) | 88.2% (105) | 81.3% (13) | 0.6 (0.1–2.3) |

| • "(not) worried by meeting criteria for a mental illness?"b | 66.7% (90) | 67.2% (80) | 62.5% (10) | 0.7 (0.2–2.1) |

Adjusted for age, sex, and education; 95% C.I. = 95% Confidence Interval.

Reverse-coded item.

NOTE: The two groups did not differ significantly with respect to any of the attitudes and feelings about grief symptoms that were assessed.

Table 3.

Receptivity to treatment among bereaved individuals with or without complicated grief (N=135).

| Receptivity to Treatment Among Bereaved Individuals |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Receptivity to Specific Types of Treatment | Total Sample (N=135) % (n) |

Without Complicated Grief Disorder (n=119) % (n) |

With Complicated Grief Disorder (N=16) % (n) |

Adjusted Odds Ratio (95% C.I.)a |

| If you were diagnosed with a mental illness, would you be interested in receiving treatment for this condition? |

98.5% (133) | 98.3% (117) | 100.0% (16) | ------------b |

| If you were diagnosed with a mental illness, would you be willing to receive help for this condition if others thought you would benefit from it? |

98.5% (133) | 98.3% (117) | 100.0% (16) | ------------b |

| Which of the following bereavement interventions would you be receptive to? |

||||

| • Bereavement support group | 88.9% (120) | 88.2% (105) | 93.8% (15) | 1.6 (0.2–13.3) |

| • Psychotherapy | 83.0% (112) | 81.5% (97) | 93.8% (15) | 3.2 (0.4–26.1) |

| • Medication | 78.5% (106) | 78.2% (93) | 81.3% (13) | 1.1 (0.3–4.3) |

| • Religious group/counselor | 79.3% (107) | 79.0% (94) | 81.3% (13) | 1.1 (0.3–4.1) |

Adjusted for age, sex, and education; 95% C.I. = 95% Confidence Interval.

Odds ratio could not be computed due to 100% receptivity to treatment among individuals with complicated grief.

NOTE: The two groups did not differ significantly with respect to assessed receptivity to treatment.

Table 4.

Concerns about stigmatization among bereaved individuals with or without complicated grief (N=135).

| Concerns about Reactions of Family and Friends to Grief Severity among Bereaved Individuals |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Specific Concerns about Negative Reactions of Family Members and Friends |

Total Sample (N=135) % (n) |

Without Complicated Grief Disorder (N=119) % (n) |

With Complicated Grief Disorder (N=16) % (n) |

Fisher’s Exact Testc (p-value) |

Adjusted Odds Ratio (95% C.I.)a |

| 1. If you met the criteria for Complicated Grief, do you think your family would be less understanding of what you are going through? |

2.2% (3) | 2.5% (3) | 0% (0) | -------- | ----------b |

| 2. Do you think that if you met the criteria for Complicated Grief, your family would be more likely to blame you for how you are now? |

3.7% (5) | 1.7% (2) | 18.8% (3) | 0.012 | 19.5 (1.4–262.6) |

| • Do you think that, if others outside your family knew you were diagnosed with Complicated Grief, they would be less understanding and ridicule you? |

6.7% (9) | 6.7% (8) | 6.3% (1) | -------- | 1.1 (0.1–10.2) |

| • Have your family members or friends told you that you are exaggerating or overreacting with your grief? |

5.9% (8) | 3.4% (4) | 25.0% (4) | 0.007 | 6.3 (1.2–32.8) |

| • Have your family members or friends told you that you are using grief as an excuse to be lazy? |

3.0 (4) | 0.8% (1) | 18.8% (3) | 0.005 | 15.4 (1.2–189.3) |

| • Have your family members or friends told you that you are using grief to get attention? |

3.0 (4) | 0.8% (1) | 18.8% (3) | 0.005 | 15.2 (1.2–195.2) |

| • Have your family members or friends told you that you are feeling sorry for yourself? |

5.9% (8) | 2.5% (3) | 31.3% (5) | <0.001 | 16.7 (2.7–102.3) |

Adjusted for age, sex, and education; 95% C.I. = 95% Cofidence Interval.

Odds ratio could not be computed due to the absence of concerns about negative reactions among individuals with Complicated Grief.

Fisher’s exact tests were computed due to the low number of cases reporting negative reactions from others. When there were less than 2 cases in the Complicated Grief group reporting negative reactions from others, Fisher's exact tests could not be computed.

Data Analysis

Comparative tests were conducted to test for differences in socio-demographic characteristics between the groups with and without CG. T-tests were conducted for continuous outcomes. Cochran-Mantel-Haenszel tests were conducted for dichotomous outcomes. When the expected cell count was smaller than 5, Fisher’s exact test was conducted for binary variables. Non-parametric Wilcoxon rank sum tests were conducted to test for differences between the groups with and without CG with regard to time since bereavement.

Logistic regression analyses (Zelterman, 1999.) were conducted to determine the odds ratios associated with SRS item scores based on the presence or absence of CG, controlling for age, sex, and education. The Odds Ratio can be interpreted as the ratio of the likelihood for the individuals with CG to have the SRS symptom versus the likelihood for the individuals without CG diagnosis to have the SRS symptom. Odds Ratios are considered statistically significant if the number 1.0 is greater than the higher limit of the 95% Confidence Interval, or if the number 1.0 is less than the lower limit of the 95% Confidence Interval. Hosmer and Lemeshow Goodness-of-Fit Tests (Hosmer & Lemeshow, 1989) were conducted to test for the goodness-of-fit of the logistic regression models.2 Fisher's Exact Tests were computed when an outcome was present in fewer than 10 respondents in the CG group.

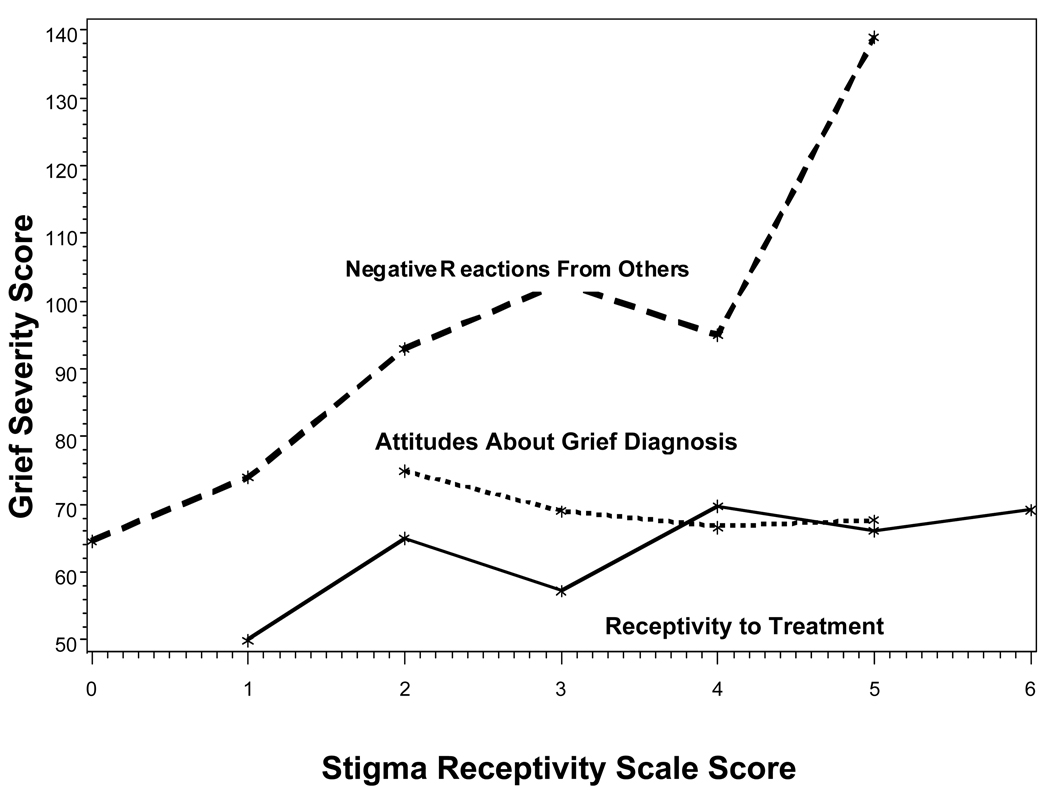

Linear regression analyses were conducted to investigate associations between the 3 SRS subscale scores and the severity of CG symptoms, controlling for age, sex, education and relationship to the deceased. The normality of the outcome variable was checked by the Q-Q plot (Neter, Kutner, Nachtsheim, & Wasserman, 1996) and the residual plots of the models were checked for violation of the model assumptions of normality, linearity, constant variance and no influential observations. In addition, CG symptom scores were plotted against each of the 3 SRS subscales to determine whether negative reactions of others, attitudes about a grief diagnosis and receptivity to mental health treatment varied as a function of grief symptom severity.

Results

Descriptive Statistics

The demographic characteristics of the study sample are presented in Table 1. There were no significant differences between the YBS wave 3 respondents who completed the SRS (N=135) and the wave 3 respondents who did not complete the SRS (N=130) with respect to gender, ethnicity, age, education, or psychiatric status.

Attitudes and Feelings about Severity of Grief Symptoms and Complicated Grief

The vast majority of respondents had positive attitudes about a diagnosis of CG (Table 2). There were no significant differences between the CG and no CG groups with respect to attitudes and feelings about grief symptoms. For example, 87.5% of the respondents with CG reported that if a clinician told them that they met criteria for CG, they would be relieved to know that they were not going crazy; 97.5% of bereaved respondents without CG reported that they would have this reaction. Most (93.8%) of the respondents with CG reported that if a clinician told them that they had CG that they would be relieved to know that they had a recognizable problem. When asked to reflect upon their own bereavement distress, 62.5% of respondents with CG and 73.1% of those without CG reported that they would feel better knowing that they had a mental condition for which effective treatment was available.

Receptivity to Treatment for a Psychiatric Condition

The vast majority of bereaved individuals with and without CG reported that they would be receptive to treatment if they were diagnosed with a mental disorder. There were no statistically significant differences between the two groups with regard to treatment receptivity. For example, 98.3% of the respondents without CG and 100% of those respondents with CG indicated that if they were to be diagnosed with a mental illness, they would be interested in and willing to receive treatment for this condition (Table 3). There was a particularly high level of interest in participating in a bereavement support group, with 88.2% of the respondents without CG and 93.8% of respondents with CG indicating receptivity to this type of treatment. More than 81% of the respondents without CG and 93.8% of those respondents with CG reported that they would be receptive to psychotherapy if they were diagnosed with a mental disorder; 78.2% and 81.3% of bereaved respondents with and without CG, respectively, reported being receptive to taking medication for their bereavement-related distress.

Concerns about Stigmatization due to Severe Grief Symptoms

Findings regarding the prevalence of specific concerns about actual or potential stigmatization by family members and friends, attributable to severe grief symptoms, are presented in Table 4. Most of the respondents did not report a high level of concern about stigmatization, regardless of whether or not they met criteria for CG. For example, no bereaved respondents with CG and only 2.5% of those without a CG diagnosis indicated that family members would be less understanding of what they were going through if they knew that they met criteria for CG. Only 6.3% and 6.7% of bereaved respondents with and without a CG diagnosis, respectively, reported that friends would ridicule them if they learned that the respondent was diagnosed with CG. These differences were not statistically significant. However, the respondents who met criteria for CG were significantly (χ2 =5.49, df=1, p=.02) more likely than respondents without CG to report that friends or family members had told them that they were exaggerating or over-reacting (25%), that they had been told that they were using grief as an excuse to be lazy (18.8%) or to get attention (18.8%), and that they had been told that they were feeling sorry for themselves (31.1%).

Associations of Stigma Receptivity Sub-Scale Scores with Grief Symptom Level

The findings with respect to severity of grief symptoms are consistent with those obtained for a CG diagnosis. Neither attitudes about a grief disorder diagnosis nor receptivity to mental health treatment were associated with the severity of grief-related distress (Table 5; Figure 1). Neither age, nor gender, nor the relationship with the deceased person contributed significant variance to the statistical models. However, the association between grief symptom severity and the number of actual or expected negative reactions from others was statistically significant (Beta=10.85, S.E.=1.78, t=6.07, df=1, p<0.0001). Twenty-two percent of the variance in the reported number of actual or expected negative reactions from others was found to be uniquely attributable to the association with grief symptom severity, net of the covariates.

Table 5.

Association between grief severity scores and Stigma Receptivity Scale sub-scale scores.

| Stigma Receptivity Scale Sub-Scale: | Association with Grief Severity Score | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Betaa | Standard Error | p | R2b | |

| • Attitudes and feelings about diagnosis of a grief disorder | −2.16 | 1.91 | 0.26 | 0.01 |

| • Receptivity to treatment among bereaved individuals | −0.24 | 1.45 | 0.87 | 0.004 |

| • Negative Reactions of Family Members and Friends | 10.85 | 1.78 | <0.0001 | 0.22 |

Age, education, sex and relationship to the deceased were controlled statistically.

Proportion of variance in Stigma Receptivity Scale subscale scores uniquely attributable to the association with grief severity scores.

Figure 1.

Associations of attitudes about grief (dotted line), receptivity to treatment (solid line), and concerns about stigmatization (dashed line) with grief severity scores.

Discussion

The present findings contribute in several ways to an increased understanding of attitudes about grief symptoms, receptivity to treatment for mental disorders and stigmatization among bereaved persons in the community. First, the findings of the present study suggest that individuals with severe grief symptoms may tend to have positive attitudes about a diagnosis of CG, and that this may not vary depending on whether or not the respondent meets the proposed criteria for this disorder. A large majority of bereaved respondents in the present study, regardless of whether they met the criteria for CG, reported that, if informed that they met criteria for a grief disorder, they would feel relieved to know that they had a recognizable problem. These findings indicate that the majority of bereaved respondents would find it helpful, rather than problematic, to know that their grief symptoms were indicative of a bereavement-related distress syndrome. In part, these results may be attributable to a heightened awareness among recently bereaved individuals that some people are profoundly and dramatically adversely affected by the loss of a loved one (i.e., validating their personal observations and feelings). In contrast with the hypothesis that a CG diagnosis might result in unnecessary labeling and medicalizing of a normal response to loss (Stroebe et al., 2001), our findings suggest that bereaved individuals may find it beneficial to have their symptoms recognized as being indicative of a grief related disorder.

The present findings also suggest that most bereaved individuals in the community may be positively disposed to the idea of receiving treatment for their grief symptoms. All of the respondents who met the criteria for CG, and 98% of those who did not, stated that they would be interested in and willing to receive treatment. These results are consistent with research indicating that 93% of caregivers of terminally ill cancer patients reported being receptive to treatment by a mental health professional (Vanderwerker, Laff, Kadan-Lottick, McColl & Prigerson, 2005). The present findings, indicating that respondents with severe grief symptoms were highly receptive to the idea of receiving targeted psychotherapy or participating in bereavement support groups, suggest that efforts should be undertaken to increase the availability of such mental health services. Notably, effective treatments are currently being developed for severe grief symptoms (Shear, Frank, Houck & Reynolds, 2005) and research has indicated that the realization that such conditions are treatable may promote early entry to care (Herrman, 2001). The widespread receptivity to treatment in the studied sample demonstrates that, contrary to the views of some bereavement experts (Stroebe et al., 2001), bereaved persons themselves do not expect to be harmed by grief interventions. Moreover, our findings indicated that bereaved individuals in the community do not tend to believe that the identification of CG itself is likely to cause reduced support from friends or family members.

Our findings do suggest that, in some cases, severe and persistent grief symptoms may be associated with experiences of perceived stigmatization by friends or family members. Although few of the respondents in the present study reported having experienced negative reactions to their bereavement-related distress, those with CG were more likely to report that friends or family members told them that they were feeling sorry for themselves, being lazy, seeking attention, or exaggerating their grief. The findings in Table 4 and Figure 1 indicate that perceived experiences of prior stigmatization were principally attributable to the severity and persistence of the respondents' grief symptoms, rather than to a new CG diagnosis. To the extent that a CG diagnosis promotes treatment utilization, as suggested by the present findings, the identification of CG may actually reduce the likelihood of subsequent stigmatization, particularly if treatment is effective in reducing the severity of bereavement-related distress. It will be of interest for future research to investigate whether public education efforts that explain the characteristics of severe grief reactions may help to prevent or alleviate the stigmatization of severe grief.

It will be of interest for future research to investigate whether the association between grief symptoms and stigmatization tends to be unidirectional or bi-directional in nature. Although severe grief symptoms may contribute to stigmatization, it may also be possible that stigmatization may, in some cases, contribute to increases in the severity of grief symptoms. Future studies should also investigate the association of grief symptoms with interpersonal interactions based on data from multiple informants, in order to distinguish between perceived and actual stigmatization. In addition, it would be of interest to conduct further research using an expanded version of the SRS that would permit a more detailed assessment of the negative reactions that individuals with severe grief reactions may have experienced.

Although the present study is the first systematic investigation of stigmatization and receptivity to treatment among bereaved individuals, the present findings are consistent with previous research indicating that diagnoses proposed for inclusion in DSM-IV did not have an adverse impact on social perceptions, and that labeling the disorder as a "psychiatric condition" was associated with increased treatment seeking (e.g., Schwartz, Weiss & Lennon, 2000). The present findings suggest that the addition of a new diagnostic criterion set for CG, in the next edition of the DSM, may improve treatment utilization without having a negative effect on social attitudes and perceptions about treatment. It will be of interest for future studies to investigate whether such findings will be replicated with the CG diagnostic criteria.

The findings of the present study may have noteworthy clinical implications. The present findings suggest that patients with severe grief symptoms may find it helpful and/or informative to know that their symptoms are indicative of an identifiable and treatable grief syndrome. Patients with severe grief symptoms, including those who meet the criteria for CG may benefit from targeted psychotherapeutic interventions (Hensley, 2006; Shear et al., 2005). Improved assessment and recognition of severe grief symptoms may increase the utilization of targeted interventions. The present findings also suggest that it would be helpful for practitioners to recognize that some individuals with severe and persistent grief symptoms may report negative reactions from others. Such individuals may benefit from interventions that assist them in coping with interpersonal stress.

The limitations of the present study require discussion. The low number of cases (n=16) with CG limited the statistical power available to detect the potential effects of CG on attitudes and feelings about grief symptoms. Although the data were obtained from a regionally representative sample, it will be of interest for future research to examine whether the present findings are applicable to other (e.g., more demographically diverse) bereaved populations. Most of the respondents in the present study were widows and widowers whose spouses died of natural causes. Future studies are needed to investigate whether the present findings will be replicated in samples drawn from other populations, particularly more acutely or severely bereaved samples. In addition, future studies should examine attitudes and feelings about stigmatization and receptivity to treatment in different age and ethnic groups, and among family members whose loved ones died as a result of traumatic events.

Another limitation is that the SRS was only administered on one occasion in the present study. It would be of interest for future studies to investigate how feelings of stigmatization and about a diagnosis of CG may change as a function of time. Lastly, the SRS is the first measure of this kind, assessing grief-related stigmatization. Although the present report is focused on specific SRS items, the modest inter-item alpha coefficient for the SRS attitudes and feelings sub-scale suggests that it will be of interest to examine whether the additional or modification of SRS items might lead to further advances in this field of study. It may be beneficial for future studies of the concurrent and predictive validity of the SRS to assess other aspects of stigmatization, such as alienation, stereotype endorsement, social withdrawal, shame, and internalized stigmatization (Ritsher, Otilingam & Grajales, 2003). It will also be of interest to investigate the potential benefits and drawbacks that may be associated with obtaining specific types of professional and informal assistance for grief-related distress.

Acknowledgment

This research was supported in part by the following grants to Dr. Prigerson: MH56529 and MH63892 from the National Institute of Mental Health and CA106370 from the National Cancer Institute; a Soros Open Society Institute Project on Death in America Faculty Scholarship; a RAND/Hartford Interdisciplinary Geriatric Health Research Center Grant; a Fetzer Religion at the End-of-Life Grant; the Claude D. Pepper Older Americans Independence Center Grant P30AG21342 from the National Institute on Aging; the Center for Psycho-oncology and Palliative Care Research, Dana-Farber Cancer Institute.

Footnotes

Alternative terms for "Complicated Grief," such as "Prolonged Grief Disorder" are under consideration for inclusion in the next edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-V).

The assumptions for logistic regression models are: (1) The true conditional probabilities are a logistic function of the independent variables; (2) No important variables are omitted; (3) No extraneous variables are included; (4) The independent variables are measured without error; (5) The observations are independent; (6) The independent variables are not linear combinations of each other. If the Hosmer and Lemeshow Goodness of Fit Test p-value was less than 0.05, the insignificant covariates were removed from the model and significant confounders were added to gain a better model fit. For the model regressing “relieved to know you had a recognizable problem?” on CG status, education was removed from the model to obtain a good fit. For the model regressing “Have your family member or friends told you that you are exaggerating or overacting with your grief?” on CG status, gender was removed to obtain a good fit.

References

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. Fourth Edition, Text Revision. Washington, D.C: Author; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Angermeyer MC, Beck M, Dietrich S, Holzinger A. The stigma of mental illness: patients' anticipations and experiences. International Journal of Social Psychiatry. 2004;50:153–162. doi: 10.1177/0020764004043115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bambauer KZ, Prigerson HG. The Stigma Receptivity Scale and its association with mental health service use among bereaved older adults. The Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease. 2006;194:139–141. doi: 10.1097/01.nmd.0000198200.20936.03. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boelen PA, van den Bout J, de Keijser J. Traumatic grief as a disorder distinct from bereavement-related depression and anxiety: a replication study with bereaved mental health care patients. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2003;160:1339–1341. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.160.7.1339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen JH, Gill TM, Prigerson HG. Health behaviors associated with better quality of life for older bereaved persons. Journal of Palliative Medicine. 2005;8:96–106. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2005.8.96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hensley PL. A review of bereavement-related depression and complicated grief. Psychiatric Annals. 2006;36:619–627. [Google Scholar]

- Herrman H. The need for mental health promotion. Australian & New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry. 2001;35:709–715. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1614.2001.00947.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hosmer DW, Lemeshow S. Applied Logistic Regression. New York: John Wiley & Sons, Inc.; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Melhem NM, Day N, Shear MK, Day R, Reynolds CF, Brent D. Traumatic grief among adolescents exposed to a peer's suicide. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2004;161:1411–1416. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.161.8.1411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neter J, Kutner MH, Nachtsheim CJ, Wasserman W. Applied Linear Statistical Models. 4th Edition. New York: McGraw-Hill; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Ogrodniczuk JS, Piper WE, Joyce AS, Weideman R, McCallum M, Azim HF, et al. Differentiating symptoms of complicated grief and depression among psychiatric outpatients. Canadian Journal of Psychiatry. 2003;48:87–93. doi: 10.1177/070674370304800204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ott CH. The impact of complicated grief on mental and physical health at various points in the bereavement process. Death Studies. 2003;27:249–272. doi: 10.1080/07481180302887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prigerson H, Ahmed I, Silverman GK, Saxena AK, Maciejewski PK, Jacobs SC, et al. Rates and risks of complicated grief among psychiatric clinic patients in Karachi, Pakistan. Death Studies. 2002;26:781–792. doi: 10.1080/07481180290106571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prigerson HG, Bierhals AJ, Kasl SV, Reynolds CF, Shear MK, Day N, et al. Traumatic grief as a risk factor for mental and physical morbidity. American Journal of Psychiatry. 1997;154:616–623. doi: 10.1176/ajp.154.5.616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prigerson HG, Bierhals AJ, Kasl SV, Reynolds CF, Shear MK, Newsom JT, et al. Complicated grief as a disorder distinct from bereavement-related depression and anxiety: a replication study. American Journal of Psychiatry. 1996;153:1484–1486. doi: 10.1176/ajp.153.11.1484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prigerson HG, Bridge J, Maciejewski PK, Beery LC, Rosenheck RA, Jacobs SC, et al. Influence of traumatic grief on suicidal ideation among young adults. American Journal of Psychiatry. 1999;156:1994–1995. doi: 10.1176/ajp.156.12.1994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prigerson HG, Frank E, Kasl SV, Reynolds CF, Anderson B, Zubenko GS, et al. Complicated grief and bereavement-related depression as distinct disorders: preliminary empirical validation in elderly bereaved spouses. American Journal of Psychiatry. 1995;152:22–30. doi: 10.1176/ajp.152.1.22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prigerson HG, Jacobs S. Traumatic grief as a distinct disorder. In: Stroebe MS, Hansson RO, Stroebe W, Schut H, editors. Handbook of bereavement research: consequences, coping, and care. New York: APA Press; 2001. pp. 613–645. [Google Scholar]

- Prigerson HG, Maciejewski PK, Reynolds CF, Bierhals AJ, Newsom JT, Fasiczka A, et al. Inventory of Complicated Grief: a scale to measure maladaptive symptoms of loss. Psychiatry Research. 1995;29:65–79. doi: 10.1016/0165-1781(95)02757-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prigerson HG, Shear MK, Frank E, Beery LC, Silberman R, Prigerson J, et al. Traumatic grief: a case of loss-induced trauma. American Journal of Psychiatry. 1997;154:1003–1009. doi: 10.1176/ajp.154.7.1003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prigerson HG, Shear MK, Jacobs SC, Reynolds CF, Maciejewski PK, Davidson JR, et al. Consensus criteria for traumatic grief. A preliminary empirical test. British Journal of Psychiatry. 1999;174:67–73. doi: 10.1192/bjp.174.1.67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ritsher JB, Otilingam PG, Grajales M. Internalized stigma of mental illness: psychometric properties of a new measure. Psychiatry Research. 2003;12:31–49. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2003.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz S, Weiss L, Lennon MC. Labeling effects of a controversial psychiatric diagnosis: A vignette experiment of late luteal phase dysphoric disorder. Women & Health. 2000;30:63–75. doi: 10.1300/J013v30n03_05. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shear K, Frank E, Houck PR, Reynolds CF. Treatment of complicated grief: a randomized controlled trial. Journal of the American Medical Association. 2005;293:2601–2608. doi: 10.1001/jama.293.21.2601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silverman GK, Jacobs SC, Kasl SV, Shear MK, Maciejewski PK, Noaghiul FS, et al. Quality of life impairments associated with diagnostic criteria for traumatic grief. Psychological Medicine. 2000;30:857–862. doi: 10.1017/s0033291799002524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stroebe M, Schut H, Finkenauer C. The traumatization of grief: A conceptual framework for understanding the trauma-bereavement interface. Israel Journal of Psychiatry & Related Sciences. 2001;38:185–201. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stroebe M, van Son M, Stroebe W, Kleber R, Schut H, van den Bout J. On the classification and diagnosis of pathological grief. Psychiatric Services. 2001;52:1069–1074. doi: 10.1016/s0272-7358(98)00089-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vanderwerker LC, Laff R, Kadan-Lottick NS, McColl S, Prigerson HG. Psychiatric disorders and mental health service use among caregivers of terminally ill cancer patients. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2005;28:6899–6907. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.01.370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zelterman D. Models for Discrete Data. Oxford, U.K: Clarendon Press; 1999. [Google Scholar]