Abstract

Perillyl alcohol (POH) is a naturally occurring terpene and a promising chemotherapeutic agent for glioblastoma multiform; yet, little is known about its molecular effects. Here we present results of a semi-quantitative proteomic analysis of A172 cells exposed to POH for different time-periods (1′, 10′, 30′, 60′, 4h, and 24h). The analysis identified more than 4,000 proteins; which were clustered using PatternLab for proteomics and then linked to Ras signaling, tissue homeostasis, induction of apoptosis, metallopeptidase activity, and ubiquitin-protein ligase activity. Our results make available one of the most complete protein repositories for the A172. Moreover, we detected the phosphorylation of GSK-3β (Glycogen synthase kinase) and the inhibition of ERK’s (extracellular regulated kinase) phosphorylation after 10′, which suggests a new mechanism of POH’s activation for apoptosis.

Keywords: Perillyl alcohol, glioblastoma, time-course, A172 cells, MudPIT, GSK-3, ERK

Introduction

Glioblastoma multiform (GBM) is by far the most common and malignant glioma, and is associated with a dismal prognosis. During the last 25 years, no significant advances in the treatment of GBMs have been developed. Currently, patients with surgical resection who are treated by radiation or chemotherapy have an approximate survival time of 12 months [1]. In such a scenario, the quest for more effective chemotherapeutic agents is of great importance. Perillyl alcohol (POH) is a naturally occurring terpene that is a new and promising chemotherapeutic agent. It has cytostatic and cytotoxic effects [2] and induces apoptosis in lung [3], leukocyte [4], prostate [5], and breast [6] cancer cell lines. In vivo, POH has anti-metastatic effects and is a potent inhibitor of angiogenesis [7;8]. Its chemotherapeutic effects are under evaluation in several clinical trials, including patients with colorectal, breast, or ovarian cancer [9–11]. In particular, we previously reported an ongoing clinical trial (phase I) comprising GBM patients treated by intranasal delivery that, statistically, has been shown to increase survival time [1].

Prior pharmacological studies have generated clues on the mechanism of action of POH. It has been demonstrated that POH acts by inhibiting the isoprenylation of the small GTPase Ras proteins by blocking their tethering in the cytoplasmic membrane, thus inhibiting Ras signal transduction [12;13]. In addition, POH has been shown to induce apoptosis [4;14;15], as well as to cause G0/G1 arrest in several types of cancers [16;17], to instigate transitory G2/M arrest, and also to induce enhanced Fas-mediated apoptosis [18]. The ability of POH to disrupt protein anchorage to cell membrane suggests it may interfere with other signaling processes.

Membrane proteins constitute about one third of the proteins encoded by the human genome and perform a wide variety of functions required for the development of tissues and the homeostasis of the organism. The disruption of their organization usually leads to various diseases [19;20]. Furthermore, membrane proteins represent about two thirds of the known protein targets for drugs [21], so the identification of differential protein expression under defined perturbations is necessary to understanding the fundamental roles of biological processes and for finding new drug targets [22;23].

We postulate that investigating POH’s effects on the cellular membrane proteome could help understand the mechanism of action of POH, and potentially improve the treatment regimes by combining POH with other surgical/molecular approaches. We designed an experiment that tackles this problem by exposing the human GBM A172 cell line to POH and monitoring the thousands of proteins that constantly change in space and time by harvesting the cells at several time instances during exposure (0, 1′, 10′, 30′, 60′, 4h, and 24h). We then analyzed the membrane-enriched fraction by using a shotgun proteomics strategy that comprises two-dimensional liquid chromatography coupled on-line with tandem mass spectrometry, also known as Multi-dimensional Protein Identification Technology (MudPIT) [24]. Relative quantitation of proteins was performed using spectral counting [25;26]. To help interpret the results, we developed new modules for the PatternLab for proteomics suite[27] that provide three orthogonal data analysis strategies. These strategies include: clustering proteins according to similar expression profiles (TrendQuest module); identifying proteins that are unique to a state (Approximately area-proportional Venn diagram module); and identifying statistically significant changes in protein expression for roughly the same set of states (XFold module). Further insights into selected protein groups were obtained using PatternLab’s Gene Ontology Explorer module (GOEx) [27;28]. We used western blotting to verify a subset of differentially expressed proteins and to probe several targets derived from our analysis.

Materials and Methods

Cell Culture and POH Treatment

The A172 cells were grown as monolayers in 25 cm2 tissue culture flasks in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle medium (D-MEM) supplemented with 0.2 mM nonessential amino acids, 10% fetal calf serum, penicillin (100 U/ml), streptomycin (100 μg/ml), and amphotericin B (fungizone, 2.5 mg/ml). For sub-cultivations, confluent monolayers were gently washed with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS 1X) pH 7.2, and after short trypsinization the cells were suspended in the culture medium. Three subcultures were treated with 1.8 mM of POH (Sigma-Aldrich, 96%) during 1′, 10′, 30′, 60′, 4h, and 24h; three other subcultures received no POH treatment. The medium from all cultures was discarded and a pellet was obtained by centrifugation at 700 RCF. After washing three times with PBS, the pellets were incubated in ice for 45′ with 10 mM Tris (pH 7.5) and 1 mM EDTA for enrichment of the membrane fraction. Cells were lysed in a 1cc U-100 insulin syringe filled with cell suspension by pushing and compressing the plunger several times. The soluble fraction was separated from the membrane fraction by ultra-centrifugation (18,000 RCF).

Protein Solubilization with RapiGest and Trypsin Digestion

Each protein pellet was re-suspended independently with RapiGest SF (1% stock) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Ten millimolar of dithiothreitol (DTT) were added to each pellet and the proteins were incubated at 60 °C during 30′. The pellets were cooled to room temperature and incubated with 10 mM of iodacetamide (IAA) for 20′. Then 100 mM Tris-HCl and 1 mM CaCl2 were added to make the final concentration of RapiGest 0.1%. All samples were digested with 1μg of trypsin (Promega) overnight at 37 °C. Following digestion, all reactions were acidified with 90% formic acid (5% final) to stop the proteolysis. Then samples were centrifuged during 30′ at 18,000 RCF to remove insoluble material.

Protein Identification by MudPIT

Seventy micrograms of the digested peptide mixture were loaded onto a biphasic (strong cation exchange/reversed phase) capillary column and washed with a buffer containing 5% acetonitrile, 0.1% formic acid diluted in HPLC grade water. The two-dimensional liquid chromatography separation and tandem mass spectrometry conditions were as described by Washburn et al.26 The flow rate at the tip of the biphasic column was 100 nL/min when the mobile phase composition was 95% H2O, 5% acetonitrile, and 0.1% formic acid. The ion trap mass spectrometer, Finnigan LTQ-XL (Thermo, San Jose, CA), was set to the data-dependent acquisition mode with dynamic exclusion turned on. One MS survey scan was followed by nine MS/MS scans and 12 salt steps were performed. Mass spectrometer scan functions and HPLC solvent gradients were controlled by the Xcalibur data system (Thermo, San Jose, CA).

Tandem mass spectra were extracted from the raw files using RawExtract1_9_3 [29] and were searched against the Homo sapiens plus common contaminant proteins; all sequences were downloaded as FASTA-formatted from the EBI-IPI protein database (version 3.23, released on November 2, 2006) [30]. To calculate confidence levels and false-positive rates, a decoy database that contained the reverse sequences of the original dataset appended to the target database was used [31], and the best matching sequences from the combined database were indicated by SEQUEST. The searches were done on a cluster of Intel Xeon 80 processors running the Linux operating system. The peptide mass search tolerance was set to 3 Da. No differential modifications were considered. No enzymatic cleavage conditions were imposed on the database search, so the search space included all candidate peptides whose theoretical mass fell within the 3 Da mass tolerance window, regardless of their tryptic status.

The validity of peptide/spectrum matches was assessed in DTASelect 2 [32] according to the SEQUEST [33] cross-correlation score (XCorr) and the SEQUEST normalized difference in cross-correlation score (DeltaCN). The search results were grouped by charge state (+1, +2, and +3) and tryptic status (fully tryptic, half-tryptic, and non-tryptic), resulting in 9 distinct subgroups. In each of the subgroups, the distribution of XCorr and DeltaCN values for the direct and decoy database hits was obtained, and the two subsets were separated by quadratic discriminant analysis. Outlier points in the two distributions (for example, matches with very low XCorr but very high DeltaCN) were discarded. As the full separation of the direct and decoy subsets is not generally possible, the discriminant score was set such that a false discovery rate of 1% was determined based on the number of accepted decoy database peptides. This procedure was independently performed on each data subset, resulting in a false-positive rate independent of tryptic status or charge state. In addition, a minimum sequence length of 7 amino acid residues was required, and each protein on the list was supported by at least two peptide identifications. These additional requirements, especially the latter, resulted in the elimination of most decoy database and false-positive hits, as these tended to be overwhelmingly present as proteins identified by single peptide matches. After this last filtering step, the estimated false discovery rate was reduced to below 1%.

PatternLab for Proteomics data parsing

First, the DTASelect filtered files (which contain the spectral counting information) were converted to PatternLab’s native data format (the index and sparse matrix files) by using PatternLab’s DTASelect to Sparse Matrix parser. The index file lists all identified proteins within all the project’s assays and assigns to each one a unique Protein IDentification (PID) integer. As for the sparse matrix, each row corresponds to an assay and follows the schema: 〈class label〉 〈PID1〉:〈value1〉 … 〈PIDn〉:〈valuen〉, where n is the number of identified proteins for that assay. In this work, 〈class label〉 is a member of {0,1,10,30,60,240,1440} and is used to indicate the POH exposure time (thus, 0 represents the control group and, e.g., 30 stands for 30 minutes of exposure to POH). Accordingly, 〈PIDi〉 and 〈valuei〉 correspond, respectively, to the ith protein’s identification integer and its spectral count for the respective assay. The resulting sparse matrix has 21 rows obtained from seven exposure durations analyzed in triplicates. The index and sparse matrix are available in Supplemental Data I.

Gene Ontology Explorer Analysis

To help interpret the data output by the new modules we used PatternLab’s Gene Ontology Explorer (GOEx) module [28]. GOEx is targeted at proteomic studies because it considers protein fold changes besides searching for over-represented terms. Our data analysis used the gene ontology database (OBO v1.2, downloaded on June 30, 2009) and the human annotation file (GOA, downloaded on June 30, 2009) from http://geneontology.org and http://www.ebi.ac.uk, respectively.

Western Blot Analyses

Fifteen micrograms of the membrane-enriched fraction lysate were run on a precast 4% to 12% Bis-Tris gel (Invitrogen, NP0322) and transferred onto a nitrocellulose membrane (Invitrogen, LC 2000). The membrane was blocked with 5% nonfat dry milk in TBST (50 mM Tris pH 7.5, 150 mM NaCl, and 0.1% Tween 20) during 1 h at room temperature. The blocking solution was discarded and the membrane was washed several times in milk-free TBST and incubated overnight at 4°C with anti-HSP70 primary antibody (1:2500; BD Biosciences, cat. no 610607) diluted in 1% nonfat dry milk in TBST, according to the supplier’s instructions. The following day, the membrane was washed three times in milk-free TBST and incubated with anti-mouse horseradish peroxidase-conjugated antibodies diluted 1:10000 in 1% nonfat dry milk TBST during 1h. After successive washes, the membranes were submitted to a Super Signal West Pico chemiluminescent substrate (Thermo, cat. no 34080) and exposed to X-ray Kodak film (X-Omat). The same procedure was performed for: anti-β-catenin (1:1000; Abcam, ab6301), anti-phospho-p44/42 ERK (1:500; Cell Signaling Technology, mAb # 4376), anti-p44/42 ERK (1:1000; Cell Signaling Technology, mAb # 9107), anti-phospho-GSK-3βSer 9 (1:1000; Cell Signaling Technology, mAb # 9323), and anti-GSK-3β (1:1000; Cell Signaling Technology, mAB # 9315).

Results and Discussion

Tools Created for the Data Analysis

a) TrendQuest Module

The TrendQuest module clusters proteins having similar expression profiles throughout the time-course experiment. The software proceeds as follows. The sparse matrix is loaded onto TrendQuest and quality filters are set. Here the filters were set to eliminate proteins averaging less than 5 spectral counts or detected in less than 12 of the 21 assays. Secondly, the sparse matrix is normalized. Here we opted for the total signal normalization strategy: briefly, it divides the spectral count of each protein by the sum of all spectral counts from that experiment. Thirdly, for each protein a representative time-expression profile vector is generated having one element for each of the possible time durations. Such an element contains the average spectral count of that protein for the corresponding time duration. The vector is then normalized to 1.

Finally, a hierarchical-like clustering is performed on these vectors, using the Pearson correlation coefficient as a similarity measure. To this end, the following procedure is used. Initially, one cluster is created for each vector and the vector becomes the cluster’s representative. Then a sequence of clustering steps takes place. At each of these steps, the two clusters with the most similar representatives (those for which the Pearson correlation coefficient is highest) are merged together into a new cluster, whose representative is created by averaging all its vectors (those that were contained within both the original clusters). The algorithm finishes when no two clusters can be coalesced into another one, by virtue of being insufficiently similar (i.e., no pair of representatives yields a Pearson correlation coefficient superior to a user-specified value, 0.95 in our case). Figure 1A shows TrendQuest’s graphical user interface.

Figure 1.

Graphical user interfaces for the new PatternLab modules A) The TrendQuest graphical user interface provides several quality filter and normalization options. The clustering result is displayed in the right panel. B) The XFold graphical user interface. On the left, the user can specify several parameters such as the normalization strategy and stringency parameters (e.g., minimum fold change and p-value). On the right side are the results in the form of a table showing groups of proteins (rows) that were differentially expressed for roughly the same set of different conditions. C) The AAPVD module’s graphical user interface. The number of unique proteins for each MudPIT run is shown for three biological states in an AAPVD. Clicking on the diagram’s annotations within the circles lists the proteins and further details such as the quantitation information for each experiment.

b) XFold Module

We designed the XFold module to pinpoint differentially expressed proteins when comparing multiple states. This tool extends the concept of the existing TFold and ACFold [27;28] modules, which are targeted at comparing two states by combining a statistical test (the t-test or the AC-test, respectively) with protein expression fold changes and a theoretical false discovery rate estimator [34] (the latter is necessary to address the massive multiple hypothesis testing problem). The XFold algorithm proceeds as follows. First it automatically performs a TFold (or ACFold) analysis for all organism-state pairs to find the differentially expressed proteins. Secondly, a table is generated having a row for each protein and a column for each state. A table entry is either 1 (for differentially expressed) or 0 (for not differentially expressed). Thirdly, a score is obtained by computing how many times a protein was classified as differentially expressed (i.e., summing up each row’s entries). Finally, the table’s rows are sorted by score and then clustered according to the Hamming distance between consecutive rows. This results in groups of proteins (rows) that were differentially expressed for roughly the same set of different conditions. Figure 1B shows XFold’s graphical user interface.

c) Approximately Area-Proportional Venn Diagram Module

The approximately area-proportional Venn diagram (AAPVD) module can pinpoint proteins that are unique to each condition. This module offers a quality filter capable of retaining only proteins identified within a minimum number of replicates for each condition. For this study, proteins detected in only one of the three replicates were discarded. Figure 1C shows AAPVD’s graphical user interface. By clicking on each Venn diagram’s labels for any section, a list of the proteins belonging to that section is presented, together with details such as the assays in which each protein was identified and its spectral counts. The graphics are highly customizable, besides providing important visual information. When analyzing more than two conditions, a table listing the unique proteins for every pairwise combination of conditions is also provided. By clicking on the table entry of interest, the common proteins are listed.

Differentially expressed proteins in early time points

We used the XFold module to search for differentially expressed proteins found during the early time points (≤ 10min). This is because the membrane proteins are extremely dynamic and will be the first ones to come in contact with POH. The condition for differential expression was to have an absolute fold change of at least 2.5 and a t-test p-value of less than 0.01. A group of 10 proteins was selected accordingly and is given in Supplemental Data II. GOEx indicated the “Binding” term (GO: 0005488) as overrepresented for this protein list. More specifically, the proteins were divided into the following child categories: anion binding, growth factor binding, cytokine binding, phospholipid binding, ribonucleotide binding, and purine binding. Within the cellular component namespace of GO, GOEx also indicated these proteins to be mainly related to intracellular membrane-bound organelles (GO: 0043241) (p < 0.01).

Proteins unique to a state

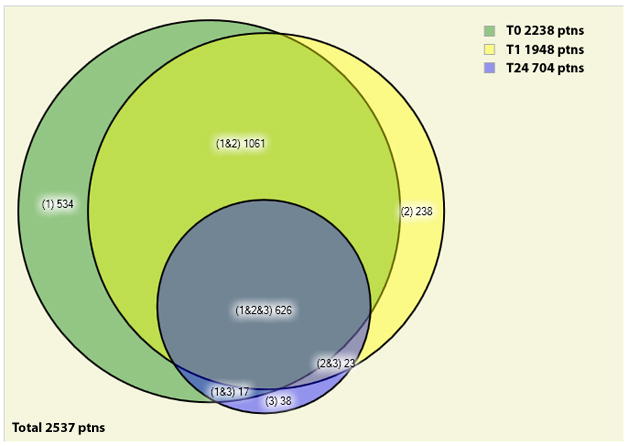

We generated an approximately area proportional Venn diagram (AAPVD) comparing the unique proteins identified for three states, namely control, 1h, and 24h exposure to 1.8 mM of POH (Figure 2). These two time durations were chosen to emphasize the analysis of proteins generated in the presence of POH. The list of the unique proteins identified for each section of the AAPVD, together with a description of each protein, is available in Supplemental Data III. The results show a considerable reduction in the number of identified proteins (from 2238 to 704) when comparing the two extreme conditions (control and 24h of exposure to POH). Among the uniquely identified proteins in the 24h case, the PICALM isoform 2 of Phosphatidylinositol-binding clathrin assembly protein (IPI00216184.3) and the AP2A1 isoform B of AP-2 complex subunit alpha-1 (IPI00256684.1) were found. AP2A1 is a component of the endocytotic clathrin-coated vesicles and abnormal expression or mutation of some endocytosis proteins has been reported in human cancers [35].

Figure 2.

AAPVD of the identified proteins present in at least two replicates for each state. The labels T0, T1, and T24 stand for A172 cells not exposed to POH, exposed to 1.8 mM of POH for 1 hour, exposed to 1.8 mM of POH for 24 hours, respectively.

Proteins sharing similar expression profiles

Based on the hypothesis that proteins functioning at similar signal transduction pathways are likely to show correlated expression profiles both temporally and spatially [36], we designed and utilized a TrendQuest algorithm to search for temporal patterns of protein expression after POH treatment on a glioblastoma cell line as described in Materials and Methods.

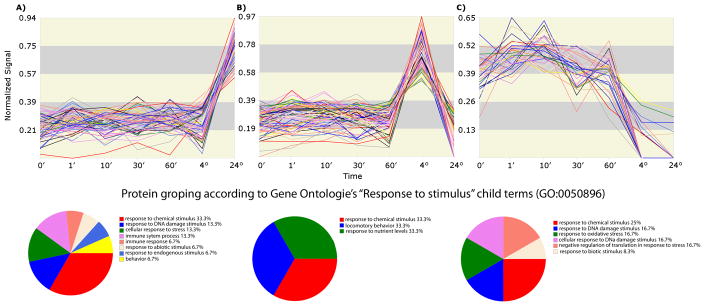

The TrendQuest analysis showed three distinct trends that we further analyzed using GOEx to map their proteins onto the Gene Ontology “Response to Stimulus” child terms (Figure 3). Trend A shows proteins whose expression increased after 24h in relation to other cell proteins. Trend B, in turn, shows proteins that increased after a 4h exposure to POH but then decreased after 24h. The proteins shown in trend C are the ones that are consistently decreasing in expression. The proteins belonging to each group are listed in Supplemental Data IV.

Figure 3.

The three major trends obtained from clustering the normalized expression profiles of A172 membrane-enriched fractions exposed to 1.8 mM of POH are displayed in Panels A, B, and C.

Trend A lists mostly proteins from the Ras pathway (e.g., Rab-2A, Rab-2B, NRAS GTPase, RAB8A, RAB5B, RAB10, and RAB14), together with some stress-related proteins, such as HSP70. Indeed, a known action mechanism of POH is its ability to inhibit the farnesylation in G proteins. The p21 Ras is a small G protein involved in signal transduction at the plasma membrane that couples signals from cell surface tyrosine kinase receptors to the cytosolic second messenger, ultimately resulting in an increase in cell growth [37;38]. The Ras protein becomes active after farnesylation, allowing its attachment to the cellular membrane and thus permitting signal transduction [39]. One of the proposed anticancer activities of POH lies in attenuating the Ras pathway by inhibiting the farnesylation of Ras [40]. Our results show the expression of the proteins from this pathway to be among the ones least affected by POH after 24h. This is indirectly reflected by the sudden increase in the last step of trend A. The rationale is as follows: the AAPVD showed that the general trend for the majority of the proteins is down-regulation. TrendQuest, on the other hand, normalized the data according to the total protein expression, so the ones that were least affected or not affected at all will present a positive slope in their trends. These given, our results suggest that this pathway is a key mechanism for survival and its stability is essential when trying to compensate for the effects of POH.

Another protein from this cluster that is indirectly linked with the Ras pathway is Caveolin (Figure 3A). It has been previously described that glioblastoma cells expressing caveolins are more aggressive and metastatic because of a potential for anchorage-independent growth [41;42]. Our results are aligned with these findings by showing an elevated expression of Caveolin in the A172 clones that resisted POH after 24h. These results suggest Caveolin as a candidate marker for prognosis and drug target.

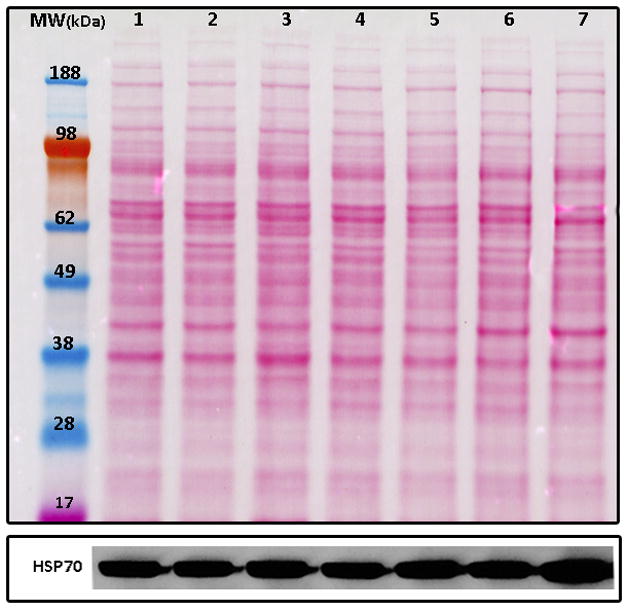

Heat shock proteins (HSP) were also found in the same trend. The HSPs are highly conserved proteins that have an important cellular function as molecular chaperones, protecting cells from various forms of stress [43]. The HSP super family includes several different molecular-weight class families, of which the Hsp70 family represents the most highly conserved [44]. The high expression of HSPs in malignant gliomas indicates a possible role of these proteins in resistance to cancer chemotherapy [45, 46]. This is because HSPs protect cells from many cell-damaging agents or conditions of environmental stress [47, 44]. Ours results suggest that an over-expression of HSP70 as compared to the general downtrend after 24h of POH exposure is associated with the surviving cells. A western blotting using an antibody against HSP70 was performed to validate trend A; its expression profile (Figure 4) correlated well with TrendQuest’s result (Figure 3A).

Figure 4.

The upper panel shows the nitrocellulose membrane stained with Ponceau red. Lanes 1–7 represent the exposure times of 0′, 1′, 10′, 30′, 60′, 4h, and 24h, respectively. The lower panel shows the western blot for the HSP70 antibody.

Biological Validations

The known function of POH as a mediator of posttranslational modification and inhibitor of Ras, together with our finding that several Ras proteins are up regulated in our membrane-enriched fraction, prompted us to look for downstream signaling proteins of the Ras/Raf/MEK pathway. We used a western blot to check the phosphorylation states of several key molecules, including ERK, GSK3, and β–catenin.

Mitogen-activated protein kinases (MAPKs) are serine threonine kinases activated by phosphorylation in response to a wide array of extracellular stimuli[48]. Three distinct groups of MAPKs have been identified in mammalian cells, namely extracellular signal regulated kinases (ERKs), c-Jun amino terminal kinases (JNKs), and p38, all of which play important roles in diverse cellular processes[49]. The extra-cellular related kinase (ERK) is a key MAPK downstream of the Ras pathway. Previously we demonstrated that POH inhibits ERK phosphorylation in lung cancer cells when exposed to POH[50]. In accordance, here we showed that POH inhibits the phosphorylation of the ERKs in glioblastoma cells after 1 minute of POH exposure, suggesting a similar mechanism of action on different cancer cells for this chemotherapeutic agent (Figure 5). Because the ERKs are thought to regulate cell growth and differentiation upon extracellular stimuli and their activation rely on serine phosphorylation, our observation indicates that POH treatment resulted in a shutting down of cell proliferation in our glioblastoma cell line.

Figure 5.

A172 enriched-membrane fraction were incubated with 1.8 mM of POH during 1′, 10′, 30′, 60′, 4h, and 24h, resolved by SDS-PAGE, and transferred to a nitrocellulose membrane. The membrane was probed with p-ERK, ERK, β-catenin, p-GSK-3β, and GSK-3β as described in Materials and Methods. This procedure was repeated twice.

GSK3β (Glycogen synthase kinase) has been shown to induce the activation of the mitogen-activated protein kinase, MEKK1, an activator of JNK, and thereby to promote signaling by the stress-activated protein kinase pathway [51]. MEK-1/2 is involved in the phosphorylation of Ty216 in GSK-3, which increases GSK-3 activity, in human skin fibroblasts [52]. On the other hand, phosphorylation at Ser9 of GSK3β has been shown to reduce its activity [53]. Using an antibody recognizing Ser9 phosphorylated GSK3β, we showed by western blot that POH rapidly induces GSK3β phosphorylation at 10 minutes, and maintains the phosphorylation state until 24 hours, without dramatically changing the total level of GSK3β (Figure 5). This indicates that POH can exert a quick and lasting effect in deactivating GSK3β. Although activation of GSK3β has been shown to influence cell survival by inducing apoptosis in a variety of pharmacological and pathological conditions [54], studies in solid tumor and cancer cell lines have associated inhibition of GSK3β activity with cancer cell apoptosis [55–57]. Specifically, a recent study showed that inhibition of GSK3β by multiple small-molecule inhibitors and genetic down-regulation of GSK3β significantly reduced glioma cell survival and clonogenicity [58]. Consistently, our observation that POH mediated the increase in GSK3β phosphorylation may play at least a partial role in its induction of apoptosis.

GSK3β inhibition has been shown to increase ERK phosphorylation, a state that activates the ERK [59]. Our western data indicates a rapid decrease in ERK phosphorylation, while an obvious increase of GSK3β phosphorylation happens at about 10 minutes, a time lag that cannot be used to account for a GSK3β-mediated ERK phosphorylation change. One possibility is that the two pathways work independently but in concert in our system, leading to the activation of downstream targets.

One known substrate of GSK3β is β-catenin, which plays a key role in intercellular adhesion and in the regulation of gene expression. Down-regulation of β-catenin is associated with oncogenic properties through inactivation of the tumor suppressor adenomatous polyposis coli (APC) or mutations in β-catenin itself [60]. In the absence of growth and differentiation signals, the cytoplasmic β-catenin is degraded by the ubiquitin-proteasome system [61] after sequential phosphorylation by the serine/threonine kinases CKI and GSK3β [62] through a scaffolding complex containing axin and APC protein [63]. Ours results showed a decreasing of the total level of β-catenin after 24 hours, which is consistent with the decreased activity of GSK3β after phosphorylation at ser9.

We have described and included three new computational tools in the PatternLab for proteomics suite for analyzing time-course shotgun proteomic experiments. We used these tools to analyze the effects of POH in the human glioblastoma cells A172. Our results contain more than 4,000 proteins and clusters related to several signaling pathways (e.g., Ras). We then described the phosphorylation of GSK-3β (Glycogen synthase kinase) and the inhibition of ERKs (extracellular regulated kinases) phosphorylation after 10 minutes, suggesting a new mechanism of POH action for apoptosis.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by CAPES, CNPq, the Rio de Janeiro Proteomic Network, a FAPERJ BBP grant, and the National Institutes of Health P41 RR011823.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Reference List

- 1.da Fonseca CO, Landeiro JA, Clark SS, Quirico-Santos T, da Costa Carvalho MG, Gattass CR. Recent advances in the molecular genetics of malignant gliomas disclose targets for antitumor agent perillyl alcohol. Surg Neurol. 2006;65 (Suppl 1):S1. doi: 10.1016/j.surneu.2005.06.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Clark SS, Zhong L, Filiault D, Perman S, Ren Z, Gould M, Yang X. Anti-leukemia effect of perillyl alcohol in Bcr/Abl-transformed cells indirectly inhibits signaling through Mek in a Ras- and Raf-independent fashion. Clin Cancer Res. 2003;12:4494–504. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yeruva L, Pierre KJ, Elegbede A, Wang RC, Carper SW. Perillyl alcohol and perillic acid induced cell cycle arrest and apoptosis in non small cell lung cancer cells. Cancer Lett. 2007;2:216–26. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2007.07.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Clark SS. Perillyl alcohol induces c-Myc-dependent apoptosis in Bcr/Abl-transformed leukemia cells. Oncology. 2006;1:13–8. doi: 10.1159/000091181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chung BH, Lee HY, Lee JS, Young CY. Perillyl alcohol inhibits the expression and function of the androgen receptor in human prostate cancer cells. Cancer Lett. 2006;2:222–8. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2005.05.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yuri T, Danbara N, Tsujita-Kyutoku M, Kiyozuka Y, Senzaki H, Shikata N, Kanzaki H, Tsubura A. Perillyl alcohol inhibits human breast cancer cell growth in vitro and in vivo. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2004;3:251–60. doi: 10.1023/B:BREA.0000019966.97011.4d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Loutrari H, Hatziapostolou M, Skouridou V, Papadimitriou E, Roussos C, Kolisis FN, Papapetropoulos A. Perillyl alcohol is an angiogenesis inhibitor. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2004;2:568–75. doi: 10.1124/jpet.104.070516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Teruszkin BI, ves de PS, Henriques SN, Curie CM, Gibaldi D, Bozza M, Orlando da FC, Carvalho Da Gloria da Costa. Effects of perillyl alcohol in glial C6 cell line in vitro and anti-metastatic activity in chorioallantoic membrane model. Int J Mol Med. 2002;6:785–8. doi: 10.3892/ijmm.10.6.785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Meadows SM, Mulkerin D, Berlin J, Bailey H, Kolesar J, Warren D, Thomas JP. Phase II trial of perillyl alcohol in patients with metastatic colorectal cancer. Int J Gastrointest Cancer. 2002;(2–3):125–8. doi: 10.1385/IJGC:32:2-3:125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Stearns V, Coop A, Singh B, Gallagher A, Yamauchi H, Lieberman R, Pennanen M, Trock B, Hayes DF, Ellis MJ. A pilot surrogate end point biomarker trial of perillyl alcohol in breast neoplasia. Clin Cancer Res. 2004;(22):7583–91. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-04-0295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bailey HH, Levy D, Harris LS, Schink JC, Foss F, Beatty P, Wadler S. A phase II trial of daily perillyl alcohol in patients with advanced ovarian cancer: Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group Study E2E96. Gynecol Oncol. 2002;(3):464–8. doi: 10.1006/gyno.2002.6647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hardcastle IR, Rowlands MG, Barber AM, Grimshaw RM, Mohan MK, Nutley BP, Jarman M. Inhibition of protein prenylation by metabolites of limonene. Biochem Pharmacol. 1999;(7):801–9. doi: 10.1016/s0006-2952(98)00349-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Crowell PL, Ren Z, Lin S, Vedejs E, Gould MN. Structure-activity relationships among monoterpene inhibitors of protein isoprenylation and cell proliferation. Biochem Pharmacol. 1994;(8):1405–15. doi: 10.1016/0006-2952(94)90341-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mills JJ, Chari RS, Boyer IJ, Gould MN, Jirtle RL. Induction of apoptosis in liver tumors by the monoterpene perillyl alcohol. Cancer Res. 1995;(5):979–83. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fernandes J, da Fonseca CO, Teixeira A, Gattass CR. Perillyl alcohol induces apoptosis in human glioblastoma multiforme cells. Oncol Rep. 2005;(5):943–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bardon S, Picard K, Martel P. Monoterpenes inhibit cell growth, cell cycle progression, and cyclin D1 gene expression in human breast cancer cell lines. Nutr Cancer. 1998;(1):1–7. doi: 10.1080/01635589809514708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bardon S, Foussard V, Fournel S, Loubat A. Monoterpenes inhibit proliferation of human colon cancer cells by modulating cell cycle-related protein expression. Cancer Lett. 2002;(2):187–94. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3835(02)00047-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rajesh D, Howard SP. Perillyl alcohol mediated radiosensitization via augmentation of the Fas pathway in prostate cancer cells. Prostate. 2003;(1):14–23. doi: 10.1002/pros.10269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Carter P, Smith L, Ryan M. Identification and validation of cell surface antigens for antibody targeting in oncology. Endocr Relat Cancer. 2004;(4):659–87. doi: 10.1677/erc.1.00766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Frame MC. Src in cancer: deregulation and consequences for cell behaviour. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2002;(2):114–30. doi: 10.1016/s0304-419x(02)00040-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rabilloud T. Membrane proteins ride shotgun. Nat Biotechnol. 2003;(5):508–10. doi: 10.1038/nbt0503-508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hopkins AL, Groom CR. The druggable genome. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2002;(9):727–30. doi: 10.1038/nrd892. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Josic D, Clifton JG. Mammalian plasma membrane proteomics. Proteomics. 2007;(16):3010–29. doi: 10.1002/pmic.200700139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Washburn MP, Wolters D, Yates JR., III Large-scale analysis of the yeast proteome by multidimensional protein identification technology. Nat Biotechnol. 2001;(3):242–7. doi: 10.1038/85686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Liu H, Sadygov RG, Yates JR., III A model for random sampling and estimation of relative protein abundance in shotgun proteomics. Anal Chem. 2004;(14):4193–201. doi: 10.1021/ac0498563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Carvalho PC, Hewel J, Barbosa VC, Yates JR., III Identifying differences in protein expression levels by spectral counting and feature selection. Genet Mol Res. 2008;(2):342–56. doi: 10.4238/vol7-2gmr426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Carvalho PC, Fischer JS, Chen EI, Yates JR, III, Barbosa VC. PatternLab for proteomics: a tool for differential shotgun proteomics. BMC Bioinformatics. 2008;(9):316. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-9-316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Carvalho PC, Fischer JS, Chen EI, Domont GB, Carvalho MG, Degrave WM, Yates JR, III, Barbosa VC. GO Explorer: A gene-ontology tool to aid in the interpretation of shotgun proteomics data. Proteome Sci. 2009;(7):6. doi: 10.1186/1477-5956-7-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.McDonald WH, Tabb DL, Sadygov RG, MacCoss MJ, Venable J, Graumann J, Johnson JR, Cociorva D, Yates JR., III MS1, MS2, and SQT-three unified, compact, and easily parsed file formats for the storage of shotgun proteomic spectra and identifications. Rapid Commun Mass Spectrom. 2004;(18):2162–8. doi: 10.1002/rcm.1603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kersey PJ, Duarte J, Williams A, Karavidopoulou Y, Birney E, Apweiler R. The International Protein Index: an integrated database for proteomics experiments. Proteomics. 2004;(7):1985–8. doi: 10.1002/pmic.200300721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Peng J, Elias JE, Thoreen CC, Licklider LJ, Gygi SP. Evaluation of multidimensional chromatography coupled with tandem mass spectrometry (LC/LC-MS/MS) for large-scale protein analysis: the yeast proteome. J Proteome Res. 2003;(1):43–50. doi: 10.1021/pr025556v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tabb DL, McDonald WH, Yates JR., III DTASelect and Contrast: tools for assembling and comparing protein identifications from shotgun proteomics. J Proteome Res. 2002;(1):21–6. doi: 10.1021/pr015504q. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Eng JK, McCormack AL, Yates, Yates JR., III An Approach to Correlate Tandem Mass Spectral Data of Peptides with Amino Acid Sequences in a Protein Database. J Am Soc Mass Spectrom. 1994;(5):976–89. doi: 10.1016/1044-0305(94)80016-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Benjamini Y, Hochberg Y. Controlling the false discovery rate: a practical and powerful approach to multiple testing. J R Stat Soc Ser B. 1995;(57):289–300. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Corsi F, De PC, Colombo M, Allevi R, Nebuloni M, Ronchi S, Rizzi G, Tosoni A, Trabucchi E, Clementi E, Prosperi D. Towards Ideal Magnetofluorescent Nanoparticles for Bimodal Detection of Breast-Cancer Cells. Small. 2009 doi: 10.1002/smll.200900881. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zhang B, VerBerkmoes NC, Langston MA, Uberbacher E, Hettich RL, Samatova NF. Detecting differential and correlated protein expression in label-free shotgun proteomics. J Proteome Res. 2006;(11):2909–18. doi: 10.1021/pr0600273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Barbacid M. ras genes. Annu Rev Biochem. 1987;(56):779–827. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.56.070187.004023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Liu JJ, Chao JR, Jiang MC, Ng SY, Yen JJ, Yang-Yen HF. Ras transformation results in an elevated level of cyclin D1 and acceleration of G1 progression in NIH 3T3 cells. Mol Cell Biol. 1995;(7):3654–63. doi: 10.1128/mcb.15.7.3654. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Rowinsky EK, Windle JJ, Von Hoff DD. Ras protein farnesyltransferase: A strategic target for anticancer therapeutic development. J Clin Oncol. 1999;(11):3631–52. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1999.17.11.3631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Chaudhary SC, Alam MS, Siddiqui MS, Athar M. Perillyl alcohol attenuates Ras-ERK signaling to inhibit murine skin inflammation and tumorigenesis. Chem Biol Interact. 2009;(2–3):145–53. doi: 10.1016/j.cbi.2008.12.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Abulrob A, Giuseppin S, Andrade MF, McDermid A, Moreno M, Stanimirovic D. Interactions of EGFR and caveolin-1 in human glioblastoma cells: evidence that tyrosine phosphorylation regulates EGFR association with caveolae. Oncogene. 2004;(41):6967–79. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1207911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Martin S, Cosset EC, Terrand J, Maglott A, Takeda K, Dontenwill M. Caveolin-1 regulates glioblastoma aggressiveness through the control of alpha(5)beta(1) integrin expression and modulates glioblastoma responsiveness to SJ749, an alpha(5)beta(1) integrin antagonist. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2009;(2):354–67. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2008.09.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Jaattela M. Heat shock proteins as cellular lifeguards. Ann Med. 1999;(4):261–71. doi: 10.3109/07853899908995889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Nylandsted J, Brand K, Jaattela M. Heat shock protein 70 is required for the survival of cancer cells. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2000;(926):122–5. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2000.tb05605.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hermisson M, Strik H, Rieger J, Dichgans J, Meyermann R, Weller M. Expression and functional activity of heat shock proteins in human glioblastoma multiforme. Neurology. 2000;(6):1357–65. doi: 10.1212/wnl.54.6.1357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Strik HM, Weller M, Frank B, Hermisson M, Deininger MH, Dichgans J, Meyermann R. Heat shock protein expression in human gliomas. Anticancer Res . 2000;(6B):4457–62. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Gyrd-Hansen M, Nylandsted J, Jaattela M. Heat shock protein 70 promotes cancer cell viability by safeguarding lysosomal integrity. Cell Cycle. 2004;(12):1484–5. doi: 10.4161/cc.3.12.1287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Schaeffer HJ, Weber MJ. Mitogen-activated protein kinases: specific messages from ubiquitous messengers. Mol Cell Biol. 1999;(4):2435–44. doi: 10.1128/mcb.19.4.2435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Seger R, Krebs EG. The MAPK signaling cascade. FASEB J. 1995;(9):726–35. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Fischer JS, Carvalho PC, Gattass CR, Paschoal EM, da Mota e Silva MS, Carvalho MG. Effects of perillyl alcohol and heat shock treatment in gene expression of human lung adenocarcinoma cell line A549. J Exp Ther Oncol. 2006;(4):301–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kim JW, Lee JE, Kim MJ, Cho EG, Cho SG, Choi EJ. Glycogen synthase kinase 3 beta is a natural activator of mitogen-activated protein kinase/extracellular signal-regulated kinase kinase kinase 1 (MEKK1) J Biol Chem. 2003;(16):13995–4001. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M300253200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Takahashi-Yanaga F, Shiraishi F, Hirata M, Miwa Y, Morimoto S, Sasaguri T. Glycogen synthase kinase-3beta is tyrosine-phosphorylated by MEK1 in human skin fibroblasts. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2004;(2):411–5. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2004.02.061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Jope RS, Johnson GV. The glamour and gloom of glycogen synthase kinase-3. Trends Biochem Sci. 2004;(2):95–102. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2003.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Grimes CA, Jope RS. The multifaceted roles of glycogen synthase kinase 3beta in cellular signaling. Prog Neurobiol. 2001;(4):391–426. doi: 10.1016/s0301-0082(01)00011-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Ougolkov AV, Fernandez-Zapico ME, Savoy DN, Urrutia RA, Billadeau DD. Glycogen synthase kinase-3beta participates in nuclear factor kappaB-mediated gene transcription and cell survival in pancreatic cancer cells. Cancer Res. 2005;(6):2076–81. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-3642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Demarchi F, Bertoli C, Sandy P, Schneider C. Glycogen synthase kinase-3 beta regulates NF-kappa B1/p105 stability. J Biol Chem. 2003;(41):39583–90. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M305676200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Tan J, Zhuang L, Leong HS, Iyer NG, Liu ET, Yu Q. Pharmacologic modulation of glycogen synthase kinase-3beta promotes p53-dependent apoptosis through a direct Bax-mediated mitochondrial pathway in colorectal cancer cells. Cancer Res. 2005;(19):9012–20. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-1226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Kotliarova S, Pastorino S, Kovell LC, Kotliarov Y, Song H, Zhang W, Bailey R, Maric D, Zenklusen JC, Lee J, Fine HA. Glycogen synthase kinase-3 inhibition induces glioma cell death through c-MYC, nuclear factor-kappaB, and glucose regulation. Cancer Res. 2008;(16):6643–51. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-0850. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Wang Q, Zhou Y, Wang X, Evers BM. Glycogen synthase kinase-3 is a negative regulator of extracellular signal-regulated kinase. Oncogene. 2006;(1):43–50. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1209004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Persad S, Troussard AA, McPhee TR, Mulholland DJ, Dedhar S. Tumor suppressor PTEN inhibits nuclear accumulation of beta-catenin and T cell/lymphoid enhancer factor 1-mediated transcriptional activation. J Cell Biol. 2001;(6):1161–74. doi: 10.1083/jcb.153.6.1161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Aberle H, Bauer A, Stappert J, Kispert A, Kemler R. beta-catenin is a target for the ubiquitin-proteasome pathway. EMBO J. 1997;(13):3797–804. doi: 10.1093/emboj/16.13.3797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Polakis P. Casein kinase 1: a Wnt’er of disconnect. Curr Biol. 2002;(14):R499–R501. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(02)00969-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Cadigan KM, Nusse R. Wnt signaling: a common theme in animal development. Genes Dev. 1997;(24):3286–305. doi: 10.1101/gad.11.24.3286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.