Abstract

Rationale and Objective

To evaluate the relationship between measurements of lung volume (LV) on inspiratory/expiratory computed tomography (CT) scans, pulmonary function tests, and CT measurements of emphysema in individuals with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD).

Materials and Methods

46 smokers (20 females and 26 males; age range 46–81 years), enrolled in the NHLBI Lung Tissue Research Consortium, underwent PFT and chest CT at full inspiration and expiration. Inspiratory and expiratory LV were automatically measured by open-source software, and the expiratory/inspiratory (E/I) ratio of LV was calculated. Mean lung density (MLD) and low attenuation area percent (LAA%,<−950HU) were also measured. Correlations of LV measurements with lung function and other CT indices were evaluated by the Spearman rank correlation test.

Results

LV E/I ratio significantly correlated with the following: the percentage of predicted value of forced expiratory volume in the first second (FEV1), the ratio of FEV1 to forced vital capacity (FVC), and the ratio of residual volume (RV) to total lung capacity (TLC) (FEV1%P, R=−0.56, p<0.0001; FEV1/FVC, R=−0.59, p<0.0001; RV/TLC, R=0.57, p<0.0001, respectively). A higher correlation coefficient was observed between expiratory LV and expiratory MLD (R=−0.73, p<0.0001) than between inspiratory LV and inspiratory MLD (R=−0.46, p<0.01). LV E/I ratio showed a very strong correlation to MLD E/I ratio (R=0.95, p<0.0001).

Conclusion

LV E/I ratio can be considered to be equivalent to MLD E/I ratio and to reflect airflow limitation and air-trapping. Higher collapsibility of lung volume, observed by inspiratory/expiratory CT, indicates less severe conditions in COPD.

Keywords: lung volume, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, computed tomography, pulmonary emphysema, airflow obstruction

Introduction

With the development of imaging analysis using computed tomography (CT) in individuals with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), several quantitative CT indices have been advocated and proved to be significant for predicting lung function. The more commonly used indices are the percentage of low attenuation area (LAA%) and mean lung density (MLD). Further, these indices on expiratory CT scans have been often reported to be stronger predictors for lung function than those on inspiratory scans [1–11]. Regarding MLD, it is also known that the expiratory/inspiratory (E/I) ratio of MLD demonstrates significant correlations with PFT [4,5,12].

In contrast, lung volume (LV) measured by CT has not been as rigorously assessed in subjects with COPD. Although prior investigations have demonstrated significant correlations between inspiratory/expiratory LV and plethysmographic measures of total lung capacity (TLC) and residual volume (RV) [1,2,13], the relationship between CT-based LV measurements, including LV E/I ratio, and airflow limitation or air-trapping is still undefined.

The relationship between MLD and LV has been gradually recognized. A recent study showed the direct relationship between inspiratory LV and MLD [14]. Further, Zaporozhan and colleagues reported that the difference in MLD (ΔMLD) strongly correlated with the difference in LV (ΔLV) on paired inspiratory/expiratory CT scans, and that ΔLV correlated with FEV1 [2]. Based upon these results, it can be predicted that expiratory LV would also reflect expiratory MLD, which is a useful CT index to predict lung function, and that LV E/I ratio would be correlated to MLD E/I ratio and be a predictor of lung function.

We therefore hypothesized that LV E/I ratio would show significant correlations with PFT as well as MLD E/I ratio, and that the CT-based LV measurements would be correlated with MLD measurements. Thus, the aim of this study is: (i) to clarify the relationship between PFT and LV measurements, including LV E/I ratio, and (ii) to confirm the correlation between LV measurements and other CT indices, in particular MLD.

Materials and methods

The study and manuscript were reviewed and approved according to the procedures outlined by the NHBLI Lung Tissue Research Consortium (LTRC). This study was also approved by the Institutional Review Board at each institution. Further information on the LTRC is available on the website [www.ltrcpublic.com].

Subjects

All subjects gave written informed consent. A total number of 46 subjects (20 females and 26 males; age range 46–81 years), who were enrolled in the LTRC, were included in this study. All subjects were current or former smokers (mean pack-years of 50.8 ± 38.4). Those who had pneumothorax, lobar atelectasis, huge bulla, interstitial pneumonia, a mass in the lung (>3cm in diameter), or a previous history of a lung operation were not included in the study. Table 1 summarizes the characteristics of the subjects.

Table 1.

Clinical characteristics of 46 LTRC subjects

| Mean ± SD | (Range) | |

|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 67.7 ± 7.9 | (46 – 81) |

| Smoking index (pack-years) | 50.8 ± 38.4 | (51 – 80) |

| FEV1 (%predicted) | 57.9 ± 24.6 | (15 – 114) |

| FEV1/FVC | 0.55 ± 0.14 | (0.25 – 0.81) |

| RV/TLC | 0.50 ± 0.12 | (0.32 – 0.73) |

| Dlco (%predicted) | 61.6 ± 22.2 | (22 – 103) |

Pulmonary Function Tests

All 46 subjects performed pre-bronchodilator spirometry, including forced expiratory volume in the first second (FEV1) and forced vital capacity (FVC), according to American Thoracic Society standards as described previously [15]. Diffusing capacity for carbon monoxide (DLco) was measured by the single breath method. These values were expressed as the percentages of predicted values. RV and TLC were also measured using plethysmography [16]. Table 1 summarizes the PFT results.

According to the Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD) staging [17], 46 subjects were classified as follows: smokers with normal lung function, n=6; GOLD stage 1, n= 7; stage 2, n=19; stage 3, n= 9; and stage 4, n=5.

Thin-section CT

All subjects were scanned with 16-detector CT (Light Speed 16 or LightSpeed Pro16, GE Medical Systems, Milwaukee, WI) at full inspiration and full expiration without receiving a contrast medium. Prior to CT scanning, subjects were coached to hold breaths at full inspiration and full expiration. Images were obtained using 140 kV and 300 mA. The scanning field of view (FOV) ranged from 28 to 44 cm, which was based upon the subject’s body habitus. Exposure time was 0.53 second and the matrix size was 512 × 512 pixels. Images were reconstructed with a 1.25mm-slice thickness (with 0.625mm-overlapping), using the ‘Bone’ algorithm.

Measurements of lung volume and other CT indices

The analysis for LV and other CT indices was performed using free open-source software (Airway Inspector, Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston, MA) [www.airwayinspector.org], as described previously [18,19]. The software automatically measured LV, LAA%[<−950 Hounsfield unit (HU)], and MLD. In brief, the software executed the following process: (i) The software segmented the lung parenchyma (−1024 to −500 HU) from the chest wall and the hilum; (ii) LV was calculated by summing the voxels in this attenuation range; (iii) MLD was obtained by averaging the CT values of the voxels in the lung parenchyma; (iv) The volume of LAA (−1024 to −950 HU) in the lung parenchyma was calculated and LAA% was obtained by dividing the total LAA volume by LV. In each subject, this process was performed both on inspiratory and expiratory scans. Figure 1 shows an example of the analysis done by the software. Ultimately, E/I ratios of LV and MLD, as well as the differences in LV and MLD (ΔLV and ΔMLD) between inspiratory and expiratory scans, were calculated.

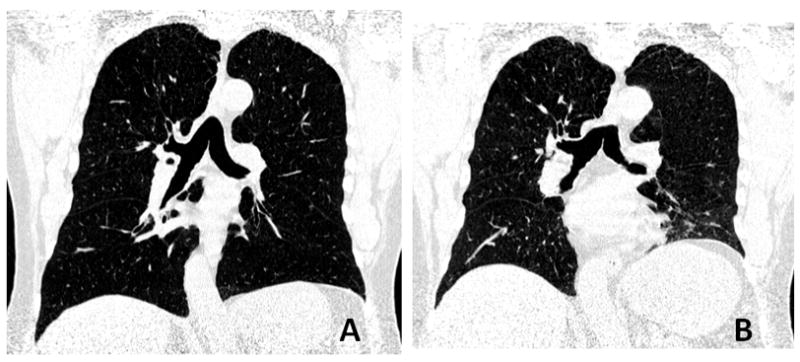

Figure 1. 69-year-old man with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (GOLD stage 2).

Reconstructed coronal CT images, which are made by the software, at full inspiration (A) and full expiration (B) are shown. Lung volume (LV) expiratory/inspiratory (E/I) ratio is 0.70, and mean lung density (MLD) E/I ratio is 0.95. Note that LV is calculated based on all axial images, not on the coronal images.

Statistical analysis

All statistical analyses were performed using JMP 7.0 software (SAS Institute, Cary, NC). Data were expressed as mean ± standard deviation. The linear regression analysis and the Spearman rank correlation analysis were used to estimate the relationships among measured CT indices, and between CT indices and PFT values. Multiple regression analysis was also performed, using MLD as the dependent outcome to evaluate relative contributions of LAA% and LV, both on inspiratory and expiratory CT. P values less than 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Results

CT measurements and correlations with lung function

Inspiratory LV was strongly correlated with TLC (R=0.829, p<0.0001) and expiratory LV with RV (R=0.700, p<0.0001), respectively. Table 2 demonstrates CT measurements, including LV measurements, and correlations with other PFT values. All LAA% and MLD values obtained by both inspiratory and expiratory scans demonstrated significant correlations with FEV1%P, FEV1/FVC, RV/TLC, and DLco%P, except for inspiratory MLD with DLco%P.

Table 2.

CT measurements and correlations with lung function

| CT measurements | Correlations with pulmonary function tests | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean ± SD | (Range) | FEV1%P | FEV1/FVC | RV/TLC | DLco%P | |

| Insp-LAA% (%) | 14.1 ± 11.9 | (1.2 – 49.7) | −0.625a | −0.713a | 0.532b | −0.606a |

| Exp-LAA% (%) | 9.3 ± 11.2 | (0.6 – 46.8) | −0.637a | −0.729a | 0.574a | −0.633a |

| Insp-MLD (HU) | −848.8 ± 35.7 | (−906.3 – −755.3) | 0.494b | 0.562a | −0.397c | 0.284 |

| Exp-MLD (HU) | −796.1 ± 60.7 | (−893.4 – −660.5) | 0.661a | 0.743a | −0.607a | 0.411c |

| MLD E/I ratio | 0.94 ± 0.05 | (0.78 – 0.99) | −0.583a | −0.648a | 0.537b | 0.366d |

| Insp-LV (L) | 5.12 ± 1.27 | (3.08 – 9.09) | −0.010 | −0.198 | −0.168 | 0.149 |

| Exp-LV (L) | 3.74 ± 1.07 | (1.76 – 6.31) | −0.406c | −0.588a | 0.252 | −0.160 |

| LV E/I ratio | 0.73 ± 0.14 | (0.39 – 0.95) | −0.563a | −0.594a | 0.571a | −0.358d |

p<0.0001;

p<0.001;

p<0.01;

p<0.05

Definition of abbreviations: insp = inspiratory, exp = expiratory, LAA% = low attenuation area percent (<−950HU), MLD = mean lung density, E/I = expiratory/inspiratory, LV = lung volume

Overall, CT measurements using expiratory scans were found to be stronger correlates of lung function than those using inspiratory scans. Expiratory MLD showed the highest correlation coefficients with FEV1%P, FEV1/FVC, and RV/TLC (FEV1%P, R=0.661, p<0.0001; FEV1/FVC, R=0.743, p<0.0001; RV/TLC. R=−0.607, p<0.0001; respectively) among all CT indices in the study. In contrast, expiratory LAA% showed the highest correlation coefficient with DLco%P (R=−0.633, p<0.0001). MLD E/I ratio was significantly correlated with FEV1%P, FEV1/FVC, RV/TLC, and DLco%P (FEV1%P, R=−0.583, p<0.0001; FEV1/FVC, R=−0.648, p<0.0001; RV/TLC, R=0.537, p=0.0002; DLco%P, R=0.366, p=0.01; respectively).

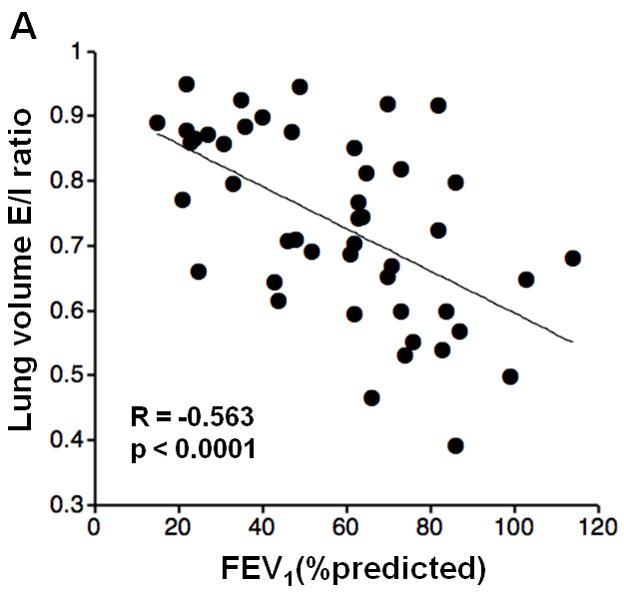

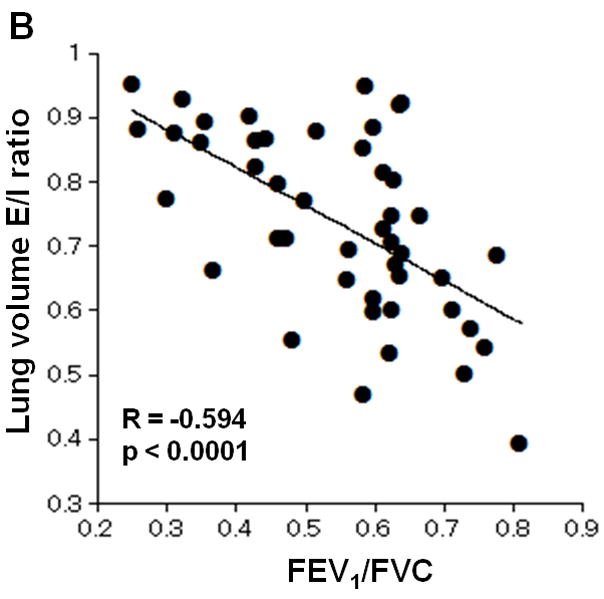

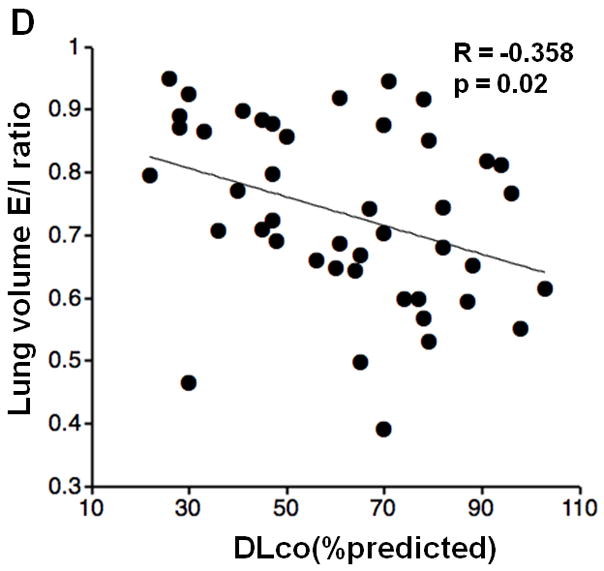

Inspiratory LV did not show significant correlations with FEV1%P, FEV1/FVC, RV/TLC, or DLco%P; however, expiratory LV demonstrated significant correlations with FEV1%P and FEV1/FVC (FEV1%P, R=−0.406, p<0.005; FEV1/FVC, R=−0.588, p<0.0001; respectively). Furthermore, LV E/I ratio demonstrated significant correlations with FEV1%P, FEV1/FVC, RV/TLC, and DLco%P (Figure 2, FEV1%P, R=−0.563, p<0.0001; FEV1/FVC, R=−0.594, p<0.0001; RV/TLC, R=0.571, p<0.0001; DLco%P, R=−0.358, p=0.02; respectively).

Figure 2. Correlations between lung volume (LV) expiratory/inspiratory (E/I) ratio and lung function.

Correlations between LV E/I ratio and PFT values are demonstrated. LV E/I ratio shows moderate correlations with FEV1%P, FEV1/FVC, and RV/TLC (A, B, C). A weak correlation is observed with DLco%P (D).

Correlations of LV measurements with MLD and LAA%

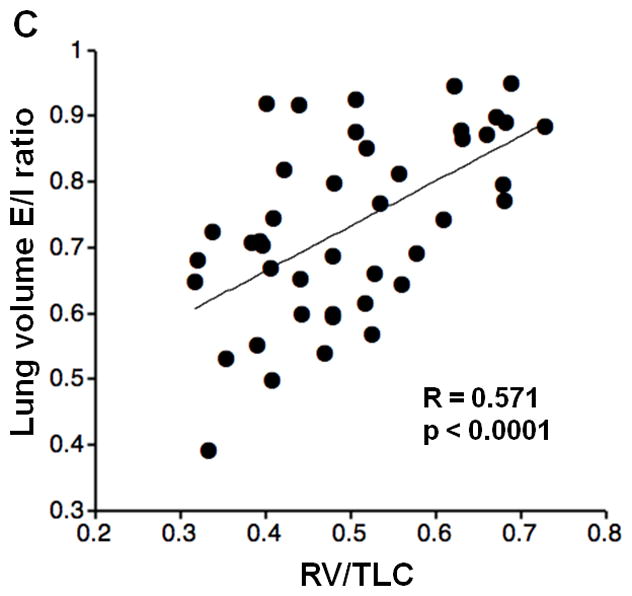

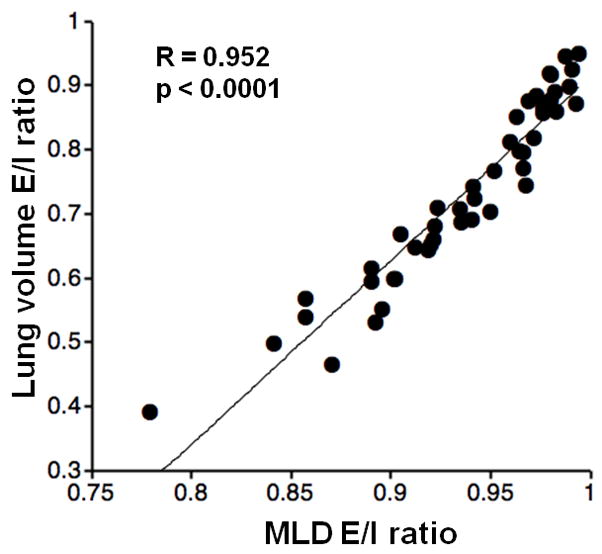

Table 3 demonstrates the correlations of LV measurements with LAA% and MLD. Overall, the correlations between LV and MLD were higher than those between LV and LAA%. The correlation coefficient of expiratory LV with expiratory MLD (R=−0.725, p<0.0001) was higher than that of inspiratory values (R=−0.463, p=0.001). LV E/I ratio also showed a strong correlation coefficient with expiratory MLD (R=−0.767, p<0.0001). Further, LV E/I ratio showed a very strong correlation with MLD E/I ratio (Figure 3, R=0.952, p<0.0001). A significant correlation was also found between ΔLV and ΔMLD (R=0.802, p<0.0001). In the multivariate analysis to predict MLD, a higher contribution of LV was observed in expiratory phase than in inspiratory phase (Table 4). In each phase, both LAA% and LV were significant predictors for MLD.

Table 3.

Correlations between CT lung volume and other indices

| Insp-LAA% | Exp-LAA% | Insp-MLD | Exp-MLD | MLD E/I ratio | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Insp-LV | 0.175 | 0.096 | −0.463c | −0.233 | 0.030 |

| Exp-LV | 0.449c | 0.482b | −0.565a | −0.725a | 0.628a |

| LV E/I ratio | 0.411c | 0.554a | −0.256 | −0.767a | 0.952a |

p<0.0001;

p<0.001;

p<0.01

Definition of abbreviations: insp = inspiratory, exp = expiratory, LAA% = low attenuation area percent (<−950HU), MLD = mean lung density, E/I = expiratory/inspiratory, LV = lung volume

Figure 3. Correlation between lung volume (LV) expiratory/inspiratory (E/I) ratio and mean lung density (MLD) E/I ratio.

LV E/I ratio demonstrates a strong correlation with MLD E/I ratio (R=0.952, p<0.0001).

Table 4.

Multivariate analysis using LV and LAA% to predict MLD

| R2 | LV | LAA% | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Std B | p | Std B | p | ||

| Inspiratory phase | 0.721 | −0.336 | <0.001 | −0.723 | <0.0001 |

| Expiratory phase | 0.760 | −0.458 | <0.0001 | −0.553 | <0.0001 |

Definition of abbreviations: MLD = mean lung density, LV = lung volume, LAA% = low attenuation area percent (<−950HU), Std B = standardized coefficient B

Discussion

In the current study, we first reported that LV E/I ratio, which demonstrates the collapsibility of the lung, shows significant correlations with airflow limitation, as well as with air-trapping. MLD measures, particularly in expiratory phase, are correlated with LV measures. Furthermore, LV E/I ratio strongly correlates with MLD E/I ratio; these two indices can be considered to be equivalent. Higher collapsibility of the lung, obtained by paired inspiratory/expiratory scans, suggests less severe conditions in COPD. We believe therefore that, if expiratory scans are available, measuring LV and LV E/I ratio is recommended as it has complementary meanings for CT studies for COPD.

The published data concerning the utility of CT-based measures LV and its correlation to lung function is limited in scope [1,2,13,20]. Although some CT studies, including the studies for lung volume reduction surgery or bronchial valve treatment, have demonstrated the correlations of LV with TLC, RV, or vital capacity [1,2,13,20–22], the impact of LV collapsibility on airflow limitation or air-trapping has not been fully investigated. In the current study, LV E/I ratio and expiratory LV showed significant correlations with lung function, including FEV1%P or RV/TLC, suggesting that the quantitative assessment of LV and LV E/I ratio on paired inspiratory and expiratory CT scans may be of utility in subjects with COPD.

MLD has been investigated by several studies and has been proven to be a good predictor of lung function, in particular on expiratory scans [3–7,12]. In addition, MLD E/I ratio has also been found to reflect airflow limitation and air-trapping [3,5,12]. We replicated these findings in the current study, and further found a stronger correlation between expiratory LV and MLD (R=−0.725) than between inspiratory LV and MLD (R=−0.463). In addition, on multivariate analysis, using LAA% and LV as predictors of MLD, the relative contribution of LV is higher in the model of expiratory CT than in inspiratory CT. These observations indicate that MLD, in particular expiratory MLD, is very sensitive to volumetric changes of the lung, as well as to the severity of emphysema.

Although the direct relationship between LV and MLD has been rarely investigated [14], the connection between the differences in MLD (ΔMLD) and LV (ΔLV), which are measured using CT scans obtained at two different lung volumes, has been gradually recognized in subjects with COPD or bronchial asthma [2, 23]. Such observations have also been reproduced in the current study; however, the correlation coefficient between LV E/I ratio and MLD E/I ratio (R=0.952) is much higher than that between ΔLV and ΔMLD (R=0.802). These results suggest the utility of measuring LV ratio, instead of measuring difference in LV, for another volume-adjustment technique in order to compare emphysema values on two different CT scans within a single subject [24].

Our study does not show that LV E/I ratio or expiratory LV are superior CT indices to other conventional CT measurements, such as LAA% or MLD, in predicting lung function. However, we believe that quantifying the lung collapsibility between inspiratory and expiratory scans holds potential for future CT studies in COPD. A major potential advantage of measuring LV E/I ratio would be its application for unstandardized CT data. It has already been proven that conventional CT indices, such as MLD and LAA%, are very sensitive to the differences in scanning/reconstruction protocols [25,26]. In contrast, it could be predicted that LV measures are less sensitive to such differences, because LV measurements are simple sums of the voxels/pixels included in the range of thresholds. The upper threshold may be influenced by scanning/reconstruction protocols; however, compared with the sensitivity of MLD or LAA%, LV would be a robust index for protocol differences. It would be of interest to examine whether LV E/I ratio is an alternative, universal CT index for different scanning/reconstruction protocols.

Another advantage of measuring LV collapsibility would be in its connection with airway collapsibility. Recently, Matsuoka and colleagues reported that the collapsibility of the distal bronchi, on paired inspiratory/expiratory CT scans, is a stronger predictor of airflow obstruction than airway luminal area in COPD [27]. In their study, higher collapsibility of the airways indicates more severe airflow limitation. Interestingly, in our study, higher collapsibility of the lung field suggests less severe airflow limitation. It would be of interest whether the airways included in the highly collapsed lung, which would indicate good lung function based on the current study, maintain the luminal areas on expiratory scans, and, furthermore, whether the collapsibility of such airways is truly correlated with airflow limitation.

Further, measuring LV on inspiratory and expiratory scans may be also meaningful in lobar segmentation analysis for COPD. Lobar volume analysis has been developed as a pre/post-operative assessment for bronchoscopic lung volume reduction (valve treatment) in subjects with progressed emphysema [22,28]. Although no published information is available on the collapsibility or air-trapping in each lobe in COPD, lobar LV measurements on both inspiratory and expiratory scans may directly reveal the severity of air-trapping in each lobe, which may contribute to the determination of the targeted lobe(s) for lung volume reduction, as well as for further physiological knowledge on lobar heterogeneity/severity in COPD.

We should mention some limitations in the study. First, the number of enrolled subjects was relatively small. For future study, it is recommended to have a larger number of subjects to investigate whether LV collapsibility can distinguish between early/severe COPD patients, smokers with normal lung function, and non-smoking control subjects.

Second, the threshold of −500HU for determining the lung parenchyma could be debated. Although several previous papers have adopted this threshold both for inspiratory and expiratory CT scans [2,3,8–10], it has also been reported that a higher threshold should be recommended [1]. Because lung density is increased on expiratory CT scans, it could be predicted that LV could be underestimated on expiratory scans with the same threshold, particularly in the subjects with higher collapsibility. Underestimation of MLD would be also expected on expiratory CT, because some of the lung field would be higher than the upper threshold. Although it has been reported that different upper thresholds (−200 to −500HU) do not significantly influence correlations with TLC or RV [1], and while the results of the current study suggest that expiratory CT values using the threshold are still robust, this issue would be a focus for future investigation.

Third, a lack of subjects’ cooperation, particularly on expiratory scans, was not fully evaluated in the current study. This may be one of the reasons why CT-based LV values do not perfectly match PFT values. A good correlation was observed between inspiratory LV and TLC (R=0.829). However, the correlation became relatively weak between expiratory LV and RV (R=0.700), as is reported by other investigators [1,2,20]. Furthermore, LV E/I ratio showed a lower correlation coefficient with RV/TLC (R=0.571). Even though all the correlation coefficients were statistically significant (p<0.0001), this tendency may lead to the question concerning whether LV measurements by CT truly reflect the subject’s respiratory status. It has also been suggested that TLC measured by helium-dilution or plethysmographic method is larger than inspiratory LV obtained by CT scan [2,29,30]. These disturbances, in particular on expiratory phase, can be explained by a lack of patient cooperation, the difference of the body position, or the larger effort of breath-holding at expiratory CT scanning than at PFT.

Fourth, according to the scanning protocol determined by the LTRC, a relatively high dose of radiation was used in this study. Since it can be predicted that radiation dosage would not influence CT-based LV measures, it is recommended to apply a low-dose technique to future studies for LV measurements.

Sixth, this study focused on CT measures of lung parenchyma and did not evaluate the influence of airway abnormalities. Since airway abnormalities, typically in chronic bronchitis, also significantly influence airflow limitation and air-trapping in COPD, further studies are needed to evaluate the relationship between airway abnormalities/collapsibility and LV measures.

In summary, we first reported that the collapsibility of the lung, which is expressed as LV E/I ratio, reflects lung function, including airflow limitation and air-trapping, and correlates to other CT indices. Expiratory MLD is strongly correlated with LV, and MLD LV E/I ratio can be thought to be almost an equivalent CT index to MLD E/I ratio. Higher collapsibility of LV on inspiratory/expiratory CT scans suggests less severe conditions in smokers with COPD. Future CT studies would provide another perspective on COPD by measuring LV and lung collapsibility.

Acknowledgments

This study utilized data provided by the Lung Tissue Research Consortium (LTRC) supported by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute.

Grant information: This study is supported by NIH K23HL089353-01A1 and a grant from the Parker B. Francis Foundation.

Footnotes

Special note for the name of Dr. San José Estépar

Please note that his first name is Raúl, and family name is San José Estépar. The authors would really appreciate it if the editors would pay attention to his first/family name and accents.

Conflicts of interest: Dr. Yamashiro, Dr. Matsuoka, Dr. Bartholmai, Dr. San Jose Estepar, Mr. Ross, Dr. Diaz, Dr. Murayama, Dr. Hatabu, and Dr. Washko have no conflicts of interest to disclose. Dr. Silverman received an honorarium for a talk on COPD genetics in 2006, and grant support and consulting fees from GlaxoSmithKline for two studies of COPD genetics. Dr. Silverman also received honoraria from Bayer in 2005, and from AstraZeneca in 2007 and 2008.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Kauczor HU, Heussel CP, Fischer B, Klamm R, Mildenberger P, Thelen M. Assessment of lung volumes using helical CT at inspiration and expiration: comparison with pulmonary function tests. Am J Roentgenol. 1998;171:1091–1095. doi: 10.2214/ajr.171.4.9763003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zaporozhan J, Ley S, Eberhardt R, Weinheimer O, Iliyushenko S, Herth F, et al. Paired inspiratory/expiratory volumetric thin-section CT scan for emphysema analysis: comparison of different quantitative evaluations and pulmonary function test. Chest. 2005;128:3212–3220. doi: 10.1378/chest.128.5.3212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Akira M, Toyokawa K, Inoue Y, Arai T. Quantitative CT in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: inspiratory and expiratory assessment. Am J Roentgenol. 2009;192:267–272. doi: 10.2214/AJR.07.3953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lee YK, Oh YM, Lee JH, Kim EK, Lee JH, Kim N, et al. Quantitative assessment of emphysema, air trapping, and airway thickening on computed tomography. Lung. 2008;186:157–165. doi: 10.1007/s00408-008-9071-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.O’Donnell RA, Peebles C, Ward JA, Daraker A, Angco G, Broberg P, et al. Relationship between peripheral airway dysfunction, airflow obstruction, and neutrophilic inflammation in COPD. Thorax. 2004;59:837–842. doi: 10.1136/thx.2003.019349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Arakawa A, Yamashita Y, Nakayama Y, Kadota M, Korogi H, Kawano O, et al. Assessment of lung volumes in pulmonary emphysema using multidetector helical CT: correlation with pulmonary function tests. Comput Med Imaging Graph. 2001;25:399–404. doi: 10.1016/s0895-6111(01)00004-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kauczor HU, Hast J, Heussel CP, Schlegel J, Mildenberger P, Thelen M. CT attenuation of HRCT scans obtained at full inspiratory and expiratory position: comparison with pulmonary function tests. Eur Radiol. 2002;12:2757–2763. doi: 10.1007/s00330-002-1514-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mergo PJ, Williams WF, Gonzalez-Rothi R, Gibson R, Ros PR, Staab EV, et al. Three-dimensional volumetric assessment of abnormally low attenuation of the lung from routine helical CT: inspiratory and expiratory quantification. Am J Roentgenol. 1998;170:1355–1360. doi: 10.2214/ajr.170.5.9574615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Matsuoka S, Kurihara Y, Yagihashi K, Hoshino M, Watanabe N, Nakajima Y. Quantitative assessment of air trapping in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease using inspiratory and expiratory volumetric MDCT. Am J Roentgenol. 2008;190:762–769. doi: 10.2214/AJR.07.2820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Matsuoka S, Kurihara Y, Yagihashi K, Nakajima Y. Quantitative assessment of peripheral airway obstruction on paired expiratory/inspiratory thin-section computed tomography in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease with emphysema. J Comput Assist Tomogr. 2007;31:384–389. doi: 10.1097/01.rct.0000243457.00437.10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nishino M, Roberts DH, Sitek A, Raptopoulos V, Boiselle PM, Hatabu H. Loss of anteroposterior intralobar attenuation gradient of the lung: correlation with pulmonary function. Acad Radiol. 2006;13:589–597. doi: 10.1016/j.acra.2005.10.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kubo K, Eda S, Yamamoto H, Fujimoto K, Matsuzawa Y, Murayama Y, et al. Expiratory and inspiratory chest computed tomography and pulmonary function tests in cigarette smokers. Eur Respir J. 1999;13:252–256. doi: 10.1034/j.1399-3003.1999.13b06.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Iwano S, Okada T, Satake H, Naganawa S. 3D-CT volumetry of the lung using multidetector row CT: comparison with pulmonary function tests. Acad Radiol. 2009;16:250–256. doi: 10.1016/j.acra.2008.09.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Camiciottoli G, Cavigli E, Grassi L, Diciotti S, Orlandi I, Zappa M, et al. Prevalence and correlates of pulmonary emphysema in smokers and former smokers: a densitometric study of participants in the ITALUNG trial. Eur Radiol. 2009;19:58–66. doi: 10.1007/s00330-008-1131-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Miller MR, Hankinson J, Brusasco V, Burgos F, Casaburi R, Coates A, et al. ATS/ERS task force: standardisation of spirometry. Eur Respir J. 2005;26:319–338. doi: 10.1183/09031936.05.00034805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Stocks, Quanjer PH. Reference values for residual volume, functional residual capacity and total lung capacity: ATS workshop on lung volume measurements/official statement of the European Respiratory Society. Eur Respir J. 1995;8:492–506. doi: 10.1183/09031936.95.08030492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rabe KF, Hurd S, Anzueto A, Barnes PJ, Buist SA, Calverley P, et al. Global strategy for the diagnosis, management, and prevention of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: GOLD executive summary. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2007;176:532–555. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200703-456SO. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dransfield MT, Washko GR, Foreman MG, San Jose Estepar R, Reilly J, Bailey WC. Gender differences in the severity of CT emphysema in COPD. Chest. 2007;132:464–470. doi: 10.1378/chest.07-0863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Washko GR, Dransfield MT, San Jose Estepar R, Diaz A, Matsuoka S, Yamashiro T, et al. Airway wall attenuation: a biomarker of airway disease in subjects with COPD. J Appl Phisiol. 2009;107:185–191. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00216.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Becker MD, Berkmen YM, Austin JH, Mun IK, Romney BM, Rozenshtein A, et al. Lung volumes before and after lung volume reduction surgery: quantitative CT analysis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1998;157:1593–1599. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.157.5.9706066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bae KT, Slone RM, Gierada DS, Yusen RD, Cooper JD. Patients with emphysema: quantitative CT analysis before and after lung volume reduction surgery. Radiology. 1997;203:705–714. doi: 10.1148/radiology.203.3.9169692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Coxson HO, Nasute Fauerbach PV, Storness-Bliss C, Muller NL, Cogswell S, Dillard DH, et al. Computed tomography assessment of lung volume changes after bronchial valve treatment. Eur Respir J. 2008;32:1443–1450. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00056008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cohen J, Douma WR, van Ooijen PM, Willems TP, Dicken V, Kuhnigk JM, et al. Localization and quantification of regional and segmental air trapping in asthma. J Comput Assist Tomogr. 2008;32:562–569. doi: 10.1097/RCT.0b013e31815f2bb0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Stoel BC, Putter H, Bakker ME, Dirksen A, Stockley RA, Piitulainen E, et al. Volume correction in computed tomography densitometry for follow-up studies on pulmonary emphysema. Proc Am Thorac Soc. 2008;5:919–924. doi: 10.1513/pats.200804-040QC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Boedeker KL, McNitt-Gray MF, Rogers SR, Truong DA, Brown MS, Gjertson DW, et al. Emphysema: effect of reconstruction algorithm on CT imaging measures. Radiology. 2004;232:295–301. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2321030383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ley-Zaporozhan J, Ley S, Weinheimer O, Iliyushenko S, Erdugan S, Eberhardt R, et al. Quantitative analysis of emphysema in 3D using MDCT: influence of different reconstruction algorithms. Eur J Radiol. 2008;65:228–234. doi: 10.1016/j.ejrad.2007.03.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Matsuoka S, Kurihara Y, Yagihashi K, Hoshino M, Nakajima Y. Airway dimensions at inspiratory and expiratory multisection CT in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: correlation with airflow limitation. Radiology. 2008;248:1042–1049. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2491071650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.D’Andrilli A, Vismara L, Rolla M, Ibrahim M, Venuta F, Pochesci I, et al. Computed tomography with volume rendering for the evaluation of parenchymal hyperinflation after bronchoscopic lung volume reduction. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2009;35:403–407. doi: 10.1016/j.ejcts.2008.10.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.O’Donnell CR, Loring SH. Comparison of plethysmographic, helium dilution and CT-derive total lung capacity. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2005;171:A293. (abstract) [Google Scholar]

- 30.Garfield JL, Marchetti N, Gaughan JP, Criner GJ. Lung volume by plethsmography and CT in advanced COPD. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2009;179:A2902. (abstract) [Google Scholar]