Abstract

An adult female chimpanzee showed responding through use of exclusion in an auditory to visual matching-to-sample procedure. The chimpanzee had previously learned to associate specific visuographic symbols called lexigrams with real-world referents and the spoken English words and photographs for those referents. On some trials, an unknown spoken English word was presented as the sample, and the match choices could consist of photographs or lexigrams that already were associated with known English words as well as unknown lexigrams or photos of objects without associated lexigrams. The chimpanzee reliably avoided choosing known comparisons for these unknown samples, instead relying on exclusion to choose comparisons that were of unknown lexigrams or photographs of items without associated lexigram symbols.

Keywords: CHIMPANZEES, EXCLUSION, AUDITORY-VISUAL, MATCHING-TO-SAMPLE, SPEECH PERCEPTION

Introduction

Imagine being presented with an odd-looking and unknown fruit, and then being asked to name it. When given the choice to call it a durian or a banana, you choose durian, because you know that banana is the name for a different fruit. In this case, your response was based on exclusion. When presented with an unknown or nameless object, exclusion occurs when an unknown name is selected over a known name that is not the correct match for the presented item. The same definition applies to traditional tests involving matching-to-sample procedures. In the matching-to-sample test, the stimuli presented as samples or match comparisons can be novel or they can have already-learned associates. In tests for exclusion, if a given comparison has a known sample with which it is associated, that comparison will be avoided as the match for a novel sample (Dixon, 1977). Adult humans use exclusion (e.g., Meehan, 1995), and young children also use exclusion in recognition memory tasks (e.g., Ackerman & Emmerich, 1978) and during vocabulary learning (e.g., the fast mapping phenomenon; Markman & Wachtel, 1988; Wilkinson, Dube, & McIlvane, 1998). Exclusion also is shown by people with developmental disabilities (Ferrari, de Rose, & McIlvane, 1993; McIlvane, Kledaras, Lowry, & Stoddard, 1992; Stromer, 1989).

Exclusion plays a prominent role in certain aspects of language acquisition in humans. For example, some cases of so-called “fast-mapping” involve vocabulary learning in which unknown spoken English words are mapped to novel objects rather than familiar ones that already have names after just a few exposures (Markman & Wachtel, 1998). It is an important issue then, whether such a mechanism may be present in nonhuman animals (Kaminski, Call, & Fisher, 2004; Wilkinson et al., 1998).

Despite clear indications of the use of exclusion in humans, reports of exclusion in nonhuman animals have been mixed (for an overview, see Aust, Range, Steurer, & Huber, 2008). Some reports indicated that pigeons failed to use exclusion (e.g., Aust et al., 2008; Cumming & Berryman, 1961) but others reported that pigeons responded on the basis of exclusion (e.g., Clement & Zentall, 2003). Dogs show some evidence of reasoning by exclusion (Aust et al., 2008), and dolphins and sea lions also have shown use of exclusion. In one procedure, these marine mammals came to associate novel gestures with novel items in the environment, as opposed to associating the novel gestures with familiar items that had previously learned associations with other gestures (Herman, Richards, & Wolz, 1984; Schusterman, Gisiner, Grimm, & Hanggi, 1993; Schusterman & Krieger, 1984). Using a matching-to-sample paradigm, Kastak & Schusterman (2002) also reported use of exclusion by two sea lions. After learning two 10-item equivalence classes, the sea lions were presented with a familiar sample from one of those two classes. The comparisons were a novel item and an item from the other class, and the animals rejected the familiar comparison (from the other class).

Reports with great apes also differ with regard to the use of exclusion. Using conditional discrimination and matching-to-sample paradigms, Tomonaga, Matsuzawa, Fujita, and Yamamoto (1991) found no evidence of exclusion in a chimpanzee, although Tomonaga (1993) reported that a single chimpanzee used exclusion. Beran and Washburn (2002) reported that three chimpanzees used exclusion during matching-to-sample tests involving photographs and geometric stimuli called lexigrams. In one variation, the chimpanzees were presented with a sample photograph and four lexigrams. When the photograph was of an item that had no previously-learned lexigram label, the chimpanzees selected only lexigrams with no previous association with real world items (novel lexigrams).

There are other tests also given to nonhuman animals that involve a form of exclusion. Typically, animals must search for hidden food items within identical containers after being provided with limited information (such as being shown one container that does not contain the food). Here, exclusion is credited when animals reject one option and choose another because of the limited information that is provided. To date, a number of species have solved this problem by using exclusion, including the great apes (e.g., Call, 2006) and ravens (Schloegl et al., 2009).

In most previous studies, the stimuli presented to nonhuman animals were visual. However, some studies have used auditory stimuli. Hashiya and Kojima (2001) presented a chimpanzee with an unfamiliar human voice and a picture of a familiar and an unfamiliar human face. In previous studies, the chimpanzee had learned to match faces to voices, and in this situation the face of the unfamiliar person was selected on 75% of the trials. However, the stimulus set was small (only four pairs of faces were used as those were the only pairs for which the chimpanzee was successful in visual-visual matching-to-sample). Other studies have involved cross-modal testing of exclusion in animals by presenting verbal stimuli and determining whether novel items were matched to those verbal labels (e.g., Pepperberg & Wilcox, 2000). In one such test, the border collie Rico not only chose novel items when given a novel verbal label but then showed consistent choice of that novel item later when the same verbal label was provided (Kaminski et al., 2004).

In this experiment, cross-modal matching-to-sample performance, as it pertains to the use of exclusion, was observed in a chimpanzee (Pan troglodytes) using a computerized matching-to-sample paradigm. This chimpanzee participated in a language acquisition project (Brakke & Savage-Rumbaugh, 1995, 1996; Rumbaugh & Washburn, 2003) in which she learned to associate geometric figures called lexigrams with real world items, actions, locations, and people. She has been documented to comprehend over one hundred spoken English words (Beran, Savage-Rumbaugh, Brakke, Kelley, & Rumbaugh, 1998; Brakke & Savage-Rumbaugh, 1995). She can hear an English word and select the corresponding lexigram or photograph of the item, person, or location represented by that spoken word. This afforded an opportunity to determine whether this chimpanzee, when presented with a new spoken word, would exclude known lexigrams or photographs of things with other known verbal labels. If she did, it would expand the demonstrated exclusion performances of nonhuman animals to include cross-modal matching with arbitrary stimuli matched to spoken English words in a referential manner, and it would involve a larger set of stimuli than used in most previous studies.

If Panzee showed use of exclusion in her matching, her performance also could provide evidence about the mechanism that underlies matching by exclusion. There are three mechanisms that have been proposed to account for exclusion behavior (see Aust et al., 2008). The first is neophilia, or preference for novel stimuli. If such neophilia accounts for Panzee’s performance, she would be expected to choose novel, undefined comparison stimuli indiscriminately, and thus she would make errors on trials with defined samples because she would be attracted to the novel photographs or lexigrams. However, this possibility is highly unlikely because in this experiment the photographs and lexigrams are not novel in the sense of being unfamiliar but are instead novel only to the degree that they are not associated with known English words.

The second possible mechanism that supports responding through exclusion is avoidance, in which a subject rejects a defined match comparison due to its association with another sample but does not go so far as to form a new association between the undefined sample and this undefined match comparison. Most previous experiments with animals, including chimpanzees, have provided evidence that this is the mechanism underlying matching by exclusion (e.g., Beran & Washburn, 2002; Clement & Zentall, 2003; Schusterman et al., 1993; Tomonaga, 1993).

The third mechanism involves not only the rejection of defined match comparisons but also the formation of new associations or relations between the undefined match comparison and the undefined sample. This final mechanism, often referred to as fast mapping by researchers investigating language acquisition (e.g. Markman & Wachtel, 1998), has been elusive in tests with animals, with only limited positive evidence. That evidence comes when subjects not only prefer undefined over defined stimuli when given an undefined sample, but also prefer those specific undefined stimuli over other undefined stimuli later when again presented with undefined samples (e.g., Aust et al., 2008; Kaminski et al., 2004). Thus, learning by exclusion (or fast mapping) requires both avoidance of defined comparisons and the formation of new associations. If only the first outcome is met, responding through use of exclusion is present, but learning by exclusion (or fast mapping) is not.

The present experiment allowed simultaneously assessment of both of these components of potential learning by exclusion because trials were presented with both defined and undefined comparisons to be matched to defined and undefined samples. If Panzee showed improved performance in matching undefined comparisons with undefined English words that could not be accounted for solely through avoidance of defined match choices, this would indicate fast-mapping, or learning by exclusion. However, if her performance with undefined samples showed only that she chose undefined comparison stimuli, but that she did not consistently choose specific undefined comparison stimuli for undefined samples, this would indicate that avoidance formed the basis of the exclusion performance, and it would argue against learning by exclusion or fast mapping.

Materials and methods

Subject

The subject was an 18-year old female chimpanzee (Pan troglodytes) named Panzee that had been involved in comparative research projects focused on planning behavior, recall memory, delay of gratification and numerical competence (e.g., Beran, 2002; Beran & Beran, 2004; Beran & Evans, 2006; Beran, Pate, Washburn, and Rumbaugh, 2004; Menzel, 1999) as well as the previous study of exclusion in chimpanzees (Beran & Washburn, 2002). Panzee had an established vocabulary of defined lexigrams ascertained through computerized matching-to-sample tests (Beran et al., 1998). The word “vocabulary” here refers to learned associations between geometric symbols called lexigrams and real world items. In addition, Panzee had a documented ability to understand over 100 spoken English words (see Beran et al., 1998; Brakke & Savage-Rumbaugh, 1995, 1996). Panzee had extensive experience using photographs in a variety of test situations, including the vocabulary tests outlined above. She had been exposed to photographs for her entire life, along with other two-dimensional stimuli that represent real world objects (such as drawings and videos). She also had daily exposure to lexigrams, which she used to communicate with humans. Previous tests of Panzee’s vocabulary showed that she performed equally well in matching photographs and lexigrams to spoken English words (e.g., Beran et al., 1998), and so these stimulus types were considered to be roughly equivalent for the purposes of the present experiment.

Materials

The computerized apparatus consisted of a Compaq DeskPro personal computer and a Kraft Systems joystick. The joystick was attached to the chimpanzee’s home cage so that she could manipulate the joystick with her hand. The matching-to-sample program used for testing was written in Visual Basic for Windows. A set of 16 photographs and corresponding lexigrams served as the stimulus set. All of the photographs were of real world items that were familiar items for Panzee. Each photograph was associated with a single lexigram. There were eight defined sets of stimuli (i.e., photographs and lexigrams which Panzee would correctly select at high levels when presented with a spoken English word) and eight undefined sets of stimuli (i.e., photographs and lexigrams for which Panzee did not know the corresponding spoken English word). The defined stimuli included the photographs and lexigrams for banana, bread, carrot, chow (protein supplement), coke, juice, M&Ms, and orange. The undefined stimuli included the photographs and lexigrams for crackers, donut, goldfish (the cracker-like food item), fruit loops, mango, pickle, popcorn, and pretzels. It is important to note that, although Panzee did not have names for these items, she was familiar with all of them as they were highly preferred food treats.

Design and Procedure

There were two conditions in this experiment. One condition involved the use of lexigrams as the comparison stimuli, and the other involved the use of photographs as the comparison stimuli. Within a given test session, trials from only one condition were presented, but across sessions condition was randomized. Sessions were presented in the order Photograph, Lexigram, Photograph, Lexigram, Lexigram, Photograph, Lexigram, Photograph, Photograph, Lexigram.

At the start of a trial, a gray square appeared in the center of the screen. Panzee moved the cursor into contact with the square, and the square then disappeared. Immediately, the sample for the trial was presented as a spoken English word by the computer program. These words were .wav file recordings of the author’s voice stating the single word. The sample type (defined or undefined) was randomized within 16-trial blocks so that one presentation with each sample was given within each block. After sample presentation, the gray square appeared again, and Panzee again had to contact it to initiate the sample presentation (a repetition of the spoken English word sample). Four comparison stimuli then were presented, each in one of six randomly selected positions around the perimeter of the screen. Only one of the presented test stimuli was the correct comparison matching the spoken English sample. Each of the three foil (incorrect) comparison stimuli was either a defined comparison (i.e., one of the eight lexigrams or photographs previously associated by Panzee with a specific spoken English word) or was an undefined comparison (i.e., one of the eight lexigrams or photographs that had no previous learned association with a spoken English word). Foil comparisons were selected randomly from the set of comparison stimuli for each trial (i.e., from the 15 stimuli that were not the correct comparisons for that sample). The computer program randomly determined whether or not each foil comparison was defined or undefined on each trial, and all potential foil comparisons were equally likely to be drawn on a given trial (i.e., choice of foil comparisons was completely random and determined by the software). Thus, there were trials in which 0, 1, 2, or all three foil comparisons were defined.

Next, Panzee moved the cursor into contact with one of the comparison stimuli. If the correct comparison was selected, a melodic tone sounded, and she received a food reward from an experimenter (a reward not corresponding to any of the 16 food items in the stimulus set). If the response was incorrect, a buzz tone sounded, Panzee received no reward, and the next trial was presented. There was a 1 s inter-trial interval before a new trial was presented. The experimenter who dispensed food reward for correctly completed trials was seated next to the computer and could hear the spoken samples but was unaware of the match choices or Panzee’s responses.

In each condition, each spoken English word was presented for 25 trials (i.e., there were 25 16-trial blocks presented in each condition). Panzee completed five sessions of 80 trials for each condition (lexigram comparison stimuli and photograph comparison stimuli).

Results

For both conditions (Lexigram match comparisons and Photograph match comparisons), performance was compared to true chance (25%) and to a modified chance level that would be expected if exclusion was used. If one foil comparison was defined, this modified chance level was 33%, if two foil comparisons were defined, this modified chance level was 50%, and if all three foil comparisons were defined this modified chance level was set at 100%. Because multiple comparisons were made for each of the chance levels, the Bonferroni correction was used and the alpha level was set at .006.

Lexigram Condition

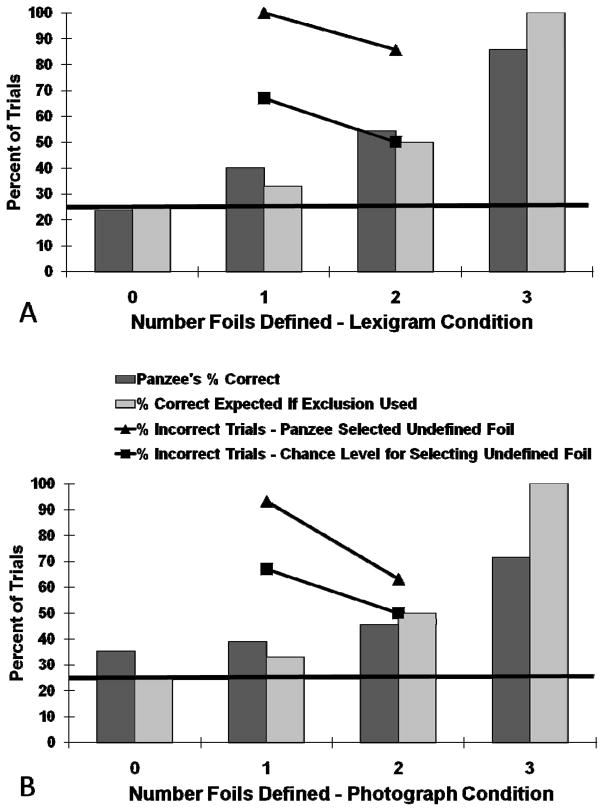

For defined samples, Panzee performed at near perfect levels (all samples 92–100% correct, p < .001 as assessed with a binomial test). The results for the undefined samples are presented in Figure 1a. In addition to Panzee’s actual performance, Figure 1a shows the performance expected by true chance (25%) and the performance expected if exclusion was used. Panzee’s performance with undefined samples significantly exceeded true chance (25%) levels when one foil comparison was defined (p = .004, binomial test), when two foil comparisons were defined (p < .001, binomial test), and when all three foil comparisons were defined (p < .001, binomial test). When none of the foil comparisons were defined, Panzee’s performance did not differ from chance levels of responding (p =.57, binomial test).

Figure 1.

A. Panzee’s performance when presented with lexigram comparison stimuli and an undefined sample stimulus. Bars present her percentage correct and the expected performance level if exclusion was used. The lines indicate the percentage of incorrect trials that involved selection of an undefined comparison stimulus by Panzee and the percentage expected by chance. The thick horizontal line represents the true chance level (25%). B. Panzee’s performance when presented with photograph comparison stimuli and an undefined sample stimulus, shown in the same way as in A.

When the modified chance level was used, however, Panzee’s performance did not differ from the performance level expected given the use of exclusion. When no foils were defined, Panzee was correct on 23.5% of the trials (modified chance = 25%, p = .57, binomial test). When one foil was defined, Panzee was correct on 40.0% of the trials (modified chance = 33%, p = .15, binomial test). When two foils were defined, Panzee was correct on 54.3% of the trials (modified chance = 50%, p = .47, binomial test).

Another way of examining the use of exclusion is to look at what errors were made by Panzee when presented with an undefined sample. These data also are presented in Figure 1.1 If Panzee was using exclusion, she should have selected undefined foil comparison stimuli significantly more often than would be expected by chance. This was true for trials with one defined foil comparison where she selected undefined comparisons on 100% of trials instead of the expected 67% (p < .001, binomial) and for trials with two defined foil comparisons where she selected undefined comparisons on 85.7% of trials instead of the expected 50% (p < .001, binomial).

Because Panzee was given feedback about her choices, the most critical trials are those that required responses without benefit from previous feedback because that feedback may have allowed Panzee to learn what matches to choose, but this would not be the result of exclusion. An examination of the first 8 trials in which an undefined sample was presented and lexigrams were the match choices showed that Panzee selected an undefined match choice on all 8 trials (she was correct on 3 of those 8 trials). In the first full session with lexigram match choices, Panzee selected an unknown match choice when presented with an unknown sample on 39 of 40 trials (97.5%; p < .001, binomial test).

Photograph Condition

For defined samples, Panzee performed at near perfect levels (all samples 92–100% correct, p < .001 as assessed with a binomial test). The results for the undefined samples are presented in Figure 1b. Panzee’s performance with undefined samples significantly exceeded true chance (25%) levels when one foil comparison was defined (p = .006, binomial test), when two foil comparisons were defined (p < .001, binomial test), and when all three foil comparisons were defined (p < .001, binomial test). When none of the foil comparisons were defined, Panzee’s performance did not differ from chance levels of responding (p =.24, binomial test).

When the modified chance level was used, however, Panzee’s performance did not differ from the performance level expected given the use of exclusion. When no foils were defined, Panzee was correct on 35.3% of the trials (modified chance = 25%, p = .24, binomial test). When one foil was defined, Panzee was correct on 38.9% of the trials (modified chance = 33%, p = .19, binomial test). When two foils were defined, Panzee was correct on 45.6% of the trials (modified chance = 50%, p = .46, binomial test).

Panzee selected undefined foil comparison stimuli significantly more often than would be expected by chance for trials with one defined foil comparison where she selected undefined comparisons on 93.2% of trials instead of the expected 67% (p < .001, binomial). However, her selection of foil comparison stimuli did not differ from that expected by chance for trials with two defined foil comparisons. On those trials, she selected undefined comparisons on 63.3% of trials instead of the expected 50% (p = .085, binomial).

Panzee selected an undefined match choice on 7 of the first 8 trials in which an undefined sample was presented (she was correct on 4 of those 8 trials). In the first full session with photograph match choices, Panzee selected an unknown match choice when presented with an unknown sample on 29 of 40 trials (72.5%; p < .01, binomial test).

Across both conditions, on 15 of 16 trials Panzee chose a photo or lexigram on the first trial with an undefined sample English word. Over the course of the first session in both conditions, she selected undefined match choices when presented with undefined samples on 67 of 80 trials (83.75%). Thus, Panzee’s use of exclusion emerged early in the experiment and likely was not influenced by the feedback she received about the responses she made to these stimuli.

Panzee showed no success in forming new associations between undefined samples and matches. In her last session with photograph matches, she was correct on 8 of 40 trials with an undefined sample and at least one undefined foil choice (20%; p = .81, binomial test). In her last session with lexigram matches, she was correct on 13 of 36 such trials (36.1%; p = .09, binomial test). Had she learned new associations between those stimuli on the basis of exclusion (i.e., fast mapping), she would have performed above chance levels at the conclusion of the experiment.

Discussion

Panzee’s performance clearly indicated use of exclusion. When she was presented with a spoken English word without a defined comparison stimulus (either a photograph or a lexigram), performance was dependent on the opportunity to eliminate foil comparisons that were previously associated with other spoken English words. The more comparison stimuli that were already associated with other spoken English words, the better Panzee’s performance. Therefore, as in the previous study with visual-visual matching-to-sample (Beran & Washburn, 2002), Panzee excluded multiple defined comparisons when presented with an undefined auditory sample. When Panzee did make errors given an undefined sample, she chose an undefined (but incorrect) comparison stimulus more often than expected by chance.

The data provide a clear indication of the mechanism supporting responding through exclusion. Panzee was not choosing undefined comparison stimuli because of the novelty (the neophilia mechanism) as she only selected those stimuli when the sample was undefined. When the sample was defined, she chose the photographs and lexigrams that also were defined. Panzee did show avoidance in her responses. She avoided defined comparison stimuli, but only when presented with an undefined sample. This is clear use of exclusion. Despite Panzee’s clear use of exclusion, however, the present data do not indicate that learning through exclusion or “fast mapping” occurred as a result, given that Panzee performed at chance levels throughout the experiment when all foil comparisons were unknown. Also, Panzee showed no improvement over time in correctly matching undefined samples, unless she could avoid defined match choices. Thus, she learned no new associations between specific speech sounds and photographs or lexigrams not already associated with other speech sounds.

The lack of newly formed, and retained, associations through use of exclusion matches what Beran and Washburn (2002) reported in the test with visual-visual matching. As such, it demonstrates a difference between chimpanzees and humans with regard to long-lasting benefits of use of exclusion. Chimpanzees seemingly do not acquire new associations by using exclusion in a matching-to-sample format, even in this task that is an analogue to the traditional tests given to children with speech perception and vocabulary learning. However, it is important to note that the present method is a far removed from the more elaborative and fluid environment in which fast mapping is considered to naturally occur in human children. Such an enriched and complex environment has been argued as critical to the emergence of speech perception and comprehension as well as symbol acquisition in great apes (e.g., Rumbaugh & Washburn, 2003; Savage-Rumbaugh, Murphy, Sevcik, Brakke, Williams, & Rumbaugh, 1993). Thus, it may require other tests to determine the capacity of chimpanzees to demonstrate long-term learning of new associations through use of exclusion. It may also be the case that chimpanzees simply need more trials in which they can use exclusion before these new associations form. Although this would seemingly exclude any interpretation of fast mapping, it could indicate that learning through exclusion was possible. Despite the lack of evidence for fast mapping, the cross-modal matching of undefined samples to undefined match stimuli by a chimpanzee offers another example of the successful use of exclusion by nonhuman animals.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by National Institutes of Health grant NICHD - 38051 and by NSF grants BCS-0924811 and SES 0729244.

Footnotes

This analysis was only performed for trials with either one or two defined foil comparisons because, with no defined foil comparisons, 100% of the incorrect selections would be of undefined foil comparisons, and with three defined foil comparisons, 0% of the incorrect choice could have been of undefined foil comparisons, and these values have no meaningful interpretation.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Ackerman BP, Emmerich HJ. When recognition memory fails: The use of an elimination strategy by young children. Dev Psychol. 1978;14:286–293. [Google Scholar]

- Aust U, Range F, Steurer M, Huber L. Inferential reasoning by exclusion in pigeons, dogs, and humans. Anim Cogn. 2008;11:587–597. doi: 10.1007/s10071-008-0149-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beran MJ. Maintenance of self-imposed delay of gratification by four chimpanzees (Pan troglodytes) and an orangutan (Pongo pygmaeus) J Gen Psychol. 2002;129:49–66. doi: 10.1080/00221300209602032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beran MJ, Beran MM. Chimpanzees remember the results of one-by-one addition of food items to sets. Psychol Sci. 2004;15:94–99. doi: 10.1111/j.0963-7214.2004.01502004.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beran MJ, Evans TA. Maintenance of delay of gratification by four chimpanzees (Pan troglodytes): The effects of delayed reward visibility, experimenter presence, and extended delay intervals. Behav Process. 2006;73:315–324. doi: 10.1016/j.beproc.2006.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beran MJ, Pate JL, Washburn DA, Rumbaugh DM. Sequential responding and planning in chimpanzees (Pan troglodytes) and rhesus macaques (Macaca mulatta) J Exp Psychol Anim Behav Proc. 2004;30:203–212. doi: 10.1037/0097-7403.30.3.203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beran MJ, Savage-Rumbaugh ES, Brakke KE, Kelley JW, Rumbaugh DM. Symbol comprehension and learning: A “vocabulary” test of three chimpanzees (Pan troglodytes) Evol Communication. 1998;2:171–188. [Google Scholar]

- Beran MJ, Washburn DA. Chimpanzee responding during matching-to-sample: Control by exclusion. J Exp Anal Behav. 2002;78:497–508. doi: 10.1901/jeab.2002.78-497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brakke KE, Savage-Rumbaugh ES. The development of language skills in bonobo and chimpanzee: I. Comprehension. Lang Commun. 1995;15:121–148. [Google Scholar]

- Brakke KE, Savage-Rumbaugh ES. The development of language skills in Pan: II Production. Lang Commun. 1996;16:361–380. [Google Scholar]

- Call J. Inferences by exclusion in the great apes: The effect of age and species. Anim Cogn. 2006;9:393–403. doi: 10.1007/s10071-006-0037-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clement TS, Zentall TR. Choice based on exclusion in pigeons. Psychon Bull Rev. 2003;10:959–964. doi: 10.3758/bf03196558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cumming WW, Berryman R. Some data on matching behavior in the pigeon. J Exp Anal Behav. 1961;4:281–284. doi: 10.1901/jeab.1961.4-281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferrari C, De Rose JC, McIlvane WJ. Exclusion vs. selection training of auditory-visual conditional relations. J Exp Child Psychol. 1993;56:49–63. doi: 10.1006/jecp.1993.1025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hashiya K, Kojima S. Hearing and auditory-visual intermodal recognition in the chimpanzee. In: Matsuzawa T, editor. Primate Origins of Human Cognition and Behavior. Springer-Verlag; Tokyo: 2001. pp. 155–189. [Google Scholar]

- Herman LN, Richards DG, Wolz JP. Comprehension of sentences by bottlenosed dolphins. Cognition. 1984;16:129–219. doi: 10.1016/0010-0277(84)90003-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaminski J, Call J, Fischer J. Word learning in a domestic dog: Evidence for “fast mapping”. Science. 2004;304:1682–1683. doi: 10.1126/science.1097859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kastak CR, Schusterman RJ. Sea lions and equivalence: Expanding classes by exclusion. J Exp Anal Behav. 2002;78:449–466. doi: 10.1901/jeab.2002.78-449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Markman EM, Wachtel GF. Children’s use of mutual exclusivity to constrain the meanings of words. Cognitive Psychol. 1988;20:121–157. doi: 10.1016/0010-0285(88)90017-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McIlvane WJ, Kledaras JB, Lowry MJ, Stoddard LT. Studies of exclusion in individuals with severe mental retardation. Res Dev Disabil. 1992;13:509–532. doi: 10.1016/0891-4222(92)90047-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meehan EF. Emergence by exclusion. Psychol Rec. 1995;45:133–154. [Google Scholar]

- Menzel CR. Unprompted recall and reporting of hidden objects by a chimpanzee (Pan troglodytes) after extended delays. J Comp Psychol. 1999;113:426–434. doi: 10.1037/0735-7036.113.4.426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pepperberg IM, Wilcox SE. Evidence for a form of mutual exclusivity during label acquisition by grey parrots (Psittacus erithacus)? J Comp Psychol. 2000;114:219–231. doi: 10.1037/0735-7036.114.3.219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rumbaugh DM, Washburn DA. Intelligence of Apes and Other Rational Beings. Yale University Press; New Haven: 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Savage-Rumbaugh ES, Murphy J, Sevcik RA, Brakke KE, Williams S, Rumbaugh DM. Language comprehension in ape and child. Monogr Soc Res Child. 1993;58:3–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schloegl C, Dierks A, Gajdon GK, Huber L, Kotrschal K, Bugnyar T. What you see is what you get? Exclusion performances in ravens and keas. PLoS One. 2009;4:e6368. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0006368. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schusterman RJ, Gisiner R, Grimm BK, Hanggi EB. Behavior control by exclusion and attempts at establishing semanticity in marine mammals using match-to-sample paradigms. In: Roitblat HL, Herman LM, Nachtigall PE, editors. Language and communication: Comparative perspectives. Erlbaum; Hillsdale, NJ: 1993. pp. 249–274. [Google Scholar]

- Schusterman RJ, Krieger K. California sea lions are capable of semantic comprehension. Psychol Rec. 1984;34:3–23. [Google Scholar]

- Stromer R. Symmetry of control by exclusion in humans’ arbitrary matching to sample. Psychol Rep. 1989;64:915–922. doi: 10.2466/pr0.1989.64.3.915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tomonaga M. Tests for control by exclusion and negative stimulus relations of arbitrary matching to sample in a “symmetry-emergent” chimpanzee. J Exp Anal Behav. 1993;59:215–229. doi: 10.1901/jeab.1993.59-215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tomonaga M, Matsuzawa T, Fujita K, Yamamoto J. Emergence of symmetry in a visual conditional discrimination by chimpanzees (Pan troglodytes) Psychol Rep. 1991;68:51–60. doi: 10.2466/pr0.1991.68.1.51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilkinson KM, Dube WV, McIlvane WJ. Fast mapping and exclusion (emergent matching) in developmental language, behavior analysis, and animal cognition research. Psychol Rec. 1998;48:407–422. [Google Scholar]