Abstract

A combination of cell intrinsic factors and extracellular signals determine whether mouse embryonic stem cells (ESC) divide, self renew, and differentiate. Here, we report a new interaction between cell intrinsic aspects of the canonical Wnt/Tcf/β-catenin signaling pathway and extracellular Lif/Jak/Stat3 stimulation that combines to promote self renewal and proliferation of ESC. Mutant ESC lacking the Tcf3 transcriptional repressor continue to self renew in the absence of exogenous Lif and through pharmacological inhibition Lif/Jak/Stat3 signaling; however, proliferation rates of TCF3−/− ESC were significantly decreased by inhibiting Jak/Stat3 activity. Cell mixing experiments showed that stimulation of Stat3 phosphorylation in TCF3−/− ESC was mediated through secretion of paracrine acting factors, but did not involve elevated Lif or LifR transcription. The new interaction between Wnt and Lif/Jak/Stat3 signaling pathways has potential for new insights into the growth of tumors caused by aberrant activity of Wnt/Tcf/β-catenin signaling.

INTRODUCTION

Stem cells interact with their extracellular environment, frequently called a niche because of its protective abilities to stimulate self renewal and inhibit differentiation of stem cells. Secreted Wnt proteins have been implicated as important extracellular niche components with potent effects on stem cells [1]. Wnt-binding to transmembrane receptors inhibits an intracellular complex of proteins including adenomatous polyposis coli (APC), axin and GSK3, which phosphorylates β-catenin, targeting it for ubiquitin-mediated degradation [2-4]. Stabilized β-catenin interacts with the DNA-binding Tcf proteins, which targets dynamic β-catenin complexes to promoters of target genes [5, 6]. A transcriptional activating function of the Tcf-β-catenin complex promotes stem cell characteristics in a remarkable variety of physiological contexts, including hematopoietic stem cells [7], hair follicle stem cells [8], intestinal crypt stem cells[9, 10], and ESC [11]. Interestingly, cancers develop when Wnt signaling is activated in blood, skin or the gut by mutational inactivation of the β-catenin-destruction complex [12], and a derangement of stem cells by Wnt signaling appears to be the underlying cause of colorectal cancer [13].

Embryonic stem cells can self renew indefinitely without a specialized niche in vitro; however, the reliance of ESC on external stimuli has been extensively studied. The extracellular environment consisting of the cohort of factors present in media and secreted by ESC has been considered to be analogous to a stem cell niche [14]. The Lif cytokine was the first identified stimulator of ESC self renewal [15], and it works by stimulating Janus kinase (Jak) phosphorylation of Stat3 and subsequent activation of Stat3 target genes. When exogenous Lif is withdrawn from ESC culture, wild type cells differentiate and senesce or undergo apoptosis after exhausting proliferative capacity usually after several days [15, 16]. Adding Wnt3a or other activators of the β-catenin stabilization was sufficient to replace Lif and stimulate ESC self renewal [11]. Recently, it was shown that mouse ESC could self renew in a chemically defined, serum-free culture medium if ERK and GSK3 kinase activity was inhibited, confirming a pivotal role for Wnt signaling in regulating self renewal [17].

Previously, we found that ablation of TCF3 in ESC was sufficient to support self renewal in the absence of exogenous Lif and delayed responses to differentiation stimuli [18]. Similar observations were also made with RNAi-mediated knockdown of Tcf3 [19, 20]. Examination of genome-wide Tcf3-binding and the effects of Tcf3-ablation and Wnt3a treatments combined to suggest that Tcf3 functioned as a transcriptional repressor on key stem cell genes, such as Nanog [18-20], and that Wnt-stabilized β-catenin appeared to counteract Tcf3-repressive effects on stem cell genes [21].

In this study, we examine the role of extrinsic factors in regulating self renewal of ESC following ablation of Tcf3. We found that TCF3−/− ESC cultured in the absence of exogenous Lif recover rapid proliferation rates through constitutive activation of Stat3 phosphorylation. Despite the effects on cell proliferation, there was little apparent effect on the stem cell characteristics. The mechanism for constitutive Stat3 phosphorylation was dependent on Jak kinase activity, and did not require elevated Lif or LifR. Finally, co-culture experiments revealed that Stat3 phosphorylation occurred non-cell-autonomously, suggesting that Tcf3 regulated the secretion of a Jak-Stat3 activating factor in stem cells. Given the effects of Wnt-Tcf-β-catenin and JakStat3 in cancer, these data offer a novel point where the intersection of two signaling pathways could combine to support proliferative self renewal of cancer cells in tumors.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cell culture

All experiments were performed using feeder-free mouse ESC lines which were maintained using standard culture conditions [21]. Cells were propagated on gelatinized (30min at room temperature) 10 cm tissue culture dishes (Falcon 35-3003) in Knockout Dulbecco's modified Eagle Medium (Knockout-DMEM, GIBCO) supplemented with 15% fetal bovine serum (Atlanta Biologicals), 2 mM L-glutamine (GIBCO), 10 mM HEPES (GIBCO), 100 U/ml penicillin (GIBCO), 100 mg/ml streptomycin (GIBCO), 0.1 mM nonessential amino acids (GIBCO), 0.1 mM β-mercatpoethanol (GIBCO), and 1000 U/ml Lif (Chemicon). Media was replaced daily and every 2-3 days, single cell suspensions of ESC were created by trypsin treatment (0.25% trypsin-EDTA; GIBCO) and passaged onto new gelatinized plates. For all proliferation assays, ESC lines were plated at a density of 5×104 cells/ml on gelatinized 6-well plates in ES media with or without 1000 U/ml Lif. Media was replaced daily. Every third day, single cell suspensions were made by trypsinization, viable cells (bromphenol blue negative) were counted by hemacytometer, and diluted for seeding on a new plate at the same density (5×104 cells/ml) for the next passage.

Short-term Lif withdrawal assay

Different groups of ESC were plated on gelatinized 6-well plate at the density of 5×104 cells/ml in media with 1000 U/ml Lif or without Lif for adapted TCF3−/− ESC. Twenty four hours later, cells were washed twice with PBS, and ES media lacking exogenous Lif was placed on the cells. Protein lysates were collected 15 and 30 minutes after addition of media by washing cells briefly with PBS and adding lysis buffer (150 mM NaCl, 10mM Tris, pH 7.2, 0.1% SDS, 1.0% Triton X-100, 1.0% Deoxycholate, 5 mM EDTA and protease inhibitors (Roche) and scraping the cells. At 30 minutes, media containing 1000 U/ml Lif was added to a third well of cells protein samples were collected after an additional 30 minute incubation.

Western blot analysis

Protein concentrations were determined for samples before electrophoresis using the Coomassie Plus Protein Assay reagent (PIERCE). Ten micrograms of total protein was separated by SDS-PAGE and transferred to nitrocellulose membranes (BioRad). The membranes were blocked with 5% Carnation-brand nonfat dry milk in PBST (phosphate buffer saline-0.05% Tween20) and incubated with primary antibody in PBST-5% milk overnight at 4°C. The primary antibodies and dilutions used were mouse anti-tubulin (1:3000, E7, DSHB), mouse anti-Oct4 (1:1500, AB/POU31-M, BD Biosciences), rabbit anti-Nanog (1:500, ab21603, Abcam), rabbit anti-phospho-STAT3 (1:1000, #9131, Cell Signaling Technologies), rabbit anti-STAT3 (1:1000, #9132, Cell Signaling Technologies). Secondary antibodies were HRP-conjugated anti rabbit and mouse both at 1:3000 dilution (Jackson labs). Signal was detected with ECL Western Blotting Detection Reagents (Amersham Biosciences).

Flow cytometry

Single cell suspensions were made by trypsin, and ESC were resuspended in 100 μl PBS. Cells were fixed by drop-wise addition of 1ml cold (−20°C) 70% ethanol while vortexing. To analyze DNA content, fixed cells were rehydrated and washed twice with 10ml PBS before finally being suspended in 200 μl PBS. Cells were stained by incubating with of 5 μg/ml propidium iodide (Sigma) and 1 mg/ml RNase A for 20 min at room temperature and analyzed on Beckman-Counter Elite ESP with WinMDI software.

Alkaline phosphatase colony assay and pyridone 6 treatment

Five hundred adapted TCF3−/− ESC were plated on gelatinized 6-well plate in media without Lif. Cells were fed daily with Lif deficient media containing four different concentration of Tetracyclic pyridone 6 (Calbiochem, Cat. No. 420097): 0; 0.25 μM; 0.5 μM; 1.0 μM. Colonies were stained for alkaline phosphatase activity after four days in culture. Briefly, cells were washed once with PBS, fixed in citrate-acetate-formaldehyde (18mM NaCitrate, 9mM NaCl, pH 3.6, 65% acetone, 37% formaldehyde) for 45 seconds, washed three times with water and stained with NBT/BCIP solution (Promega). For each well, 100 random colonies were counted and scored for levels of alkaline phosphatase activity and morphology into four categories (Fully stained, tight morphology; Fully stained, loose morphology; Partially stained, differentiated; Unstained, differentiated).

Quantitative real-time PCR (qPCR)

Total RNA was isolated with TRIZOL reagent (Invitrogen), and 3.0 mg total RNA was used as template for cDNA synthesis. Reverse transcription was carried out with oligo-dT primers (0.5 mg/ml) using SuperScript™ III First-Strand cDNA Synthesis kit (Invitrogen). Quantitative real-time PCR reactions were performed with the iTaq SYBR Green Supermix (BioRad) and an iCycler apparatus (BioRad). Amplification was achieved by the following protocol: 1× 95°C for 2 min; 40× 95°C for 30 sec; 60°C for 30 sec. To identify potential amplification of contaminating genomic DNA, control reactions using mock cDNA preparations lacking reverse transcriptase were run in parallel for each analysis. To ensure specificity of PCR, melt-curve analyses were performed at the end of all PCR reactions. The relative amount of target cDNA was determined from the appropriate standard curve and divided by the amount of GAPDH cDNA present in each sample for normalization. All PCRs had an efficiency of 80% or higher. Each sample was analyzed in duplicate, and results were expressed as means +/− standard deviations.

ESC mix culture and Immunofluorescence microscopy

Single cell suspensions of each ESC line were made by trypsinization. Cells were plated alone or pre-mixed by a 1:1 ratio with EGFP labeled adapted TCF3−/− ESC before plating on gelatinized coverslips at a density of 1×105 cells/ml. 48 hours later, cells were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde for 10min at room temperature and permeabilized with cold 100% methanol for 3min at −20°C, followed by 2 hours blocking with blocking buffer (2.5% Normal goat serum, 2.5% Normal donkey serum, 1.0% Bovine serum albumin fraction V, 0.2% Gelatin, 0.1% Tx-100 in PBS). ESC were stained overnight at 4°C with primary antibodies: rabbit anti-phospho-STAT3 (1:150, #9131, Cell Signaling Technologies) or rabbit anti-Tcf3 (1:500, Merrill lab), followed by Cy5-conjugated anti-rabbit secondary antibody (1:150, Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories) and DAPI for nuclei. Images were capture with a confocal microscope (LSM 5 PASCAL, Carl Zeiss, Germany).

RESULTS

Phosphorylation of Stat3 at tyrosine 705 and cell proliferation do not require exogenous Lif in adapted TCF3−/− ESC

Previously, we found that in contrast to TCF3+/+ ESC controls, TCF3−/− ESC could self renew in serum-containing media without exogenously added Lif [18]. Whereas TCF3+/+ ESC withdrew from the cell cycle and underwent apoptosis in the second and third passages without exogenous Lif, TCF3−/− ESC escaped apoptosis and recovered a rapid rate of proliferation following the fourth passage [18]. Such rapidly dividing, TCF3−/− ESC maintained in Lif− conditions for at least 10 passages will be referred to as “adapted” cells through the rest of this manuscript. Interestingly, the reduction in proliferation after Lif-withdrawal was returned to adapted cells when they were cultured in Lif+ media for five passages [18]. Although these data suggested an epigenetic effect of Tcf3 ablation led to Lif-independence of rapid proliferation, the nature of the relationship between Tcf3 and the effects of the Lif/Jak/Stat3 pathway was poorly understood.

We first tested the possibility that Lif-independence of adapted TCF3−/− ESC was caused by a direct stimulation of Jak/Stat3 activity in the absence of exogenous Lif. Phosphorylation of Stat3 at tyrosine 705 by Jak kinases activates Stat3 dimer formation and downstream activity as a transcription factor on downstream target genes. Therefore, we used phosphorylation of Stat3 to assess the activity of the Jak/Stat3 pathway. In short term experiments, TCF3+/+ and TCF3−/− ESC cultured in media containing 1000 U/ml Lif (Lif+) were washed twice with PBS, and placed in the same media lacking exogenous Lif (Lif−). Proteins isolated 15 and 30 minutes after Lif withdrawal were separated and probed by Western blot (Figure 1A). After these manipulations, tyrosine 705 phosphorylation of Stat3 was rapidly diminished in both TCF3+/+ and TCF3−/− ESC. Phosphorylation of Stat3 remained low for both cell types through the 30 minute duration of this experiment, and it returned to levels observed in Lif+ cultures within 30 minutes of adding fresh Lif+ media to the cells (Figure 1A). These results suggested that it was unlikely that Tcf3 affected the Lif/Jak/Stat3 pathway prior to adaptation.

Figure 1. Long-term phosphorylation of Stat3 at tyrosine 705 in TCF3−/− ESC in the absence of exogenous Lif.

A) Western blot analysis for the phosphorylation of Stat3 in short-term Lif withdrawal assay. TCF3+/+ and TCF3−/− were cultured in media containing 1000 U/ml Lif (Lif+) for 24 hours. Cells were washed twice by PBS and fed with media without supplemented Lif (Lif−). Protein samples were isolated at indicated time points. Phosphorylation of Stat3 was diminished in both ESC lines 15 and 30 minutes after Lif withdrawal, and returned to normal levels within 30 minutes when switch back to the Lif+ media. B) Stat3 was phosphorylated at a lower but substantial level comparing to the Lif+ cultures in all three independently-derived adapted TCF3−/− ESC. C) Western blot analysis for the phosphorylation of Stat3 in long-term Lif withdrawal assay. Stat3 was not significantly phosphorylated until the third passage (P3) and maintained throughout the assay (P10). D) Flow cytometry analysis for cell cycle using propidium iodide staining for total DNA content. Similarly to the TCF3+/+ and naïve TCF3−/− ESC, adapted TCF3−/− ESC exhibited a typical self renewing ESC cell cycle structure.

In contrast to the loss of Stat3 phosphorylation immediately following removal of Lif+ media, we noticed that phospho-Stat3 was detectable in the adapted cultures of TCF3−/− ESC that had not received exogenous Lif in their culture media for several passages. This effect was highly reproducible as all adapted TCF3−/− ESC lines possessed phospho-Stat3 in the absence of exogenous Lif after 10 passages (Figure 1B). All adapted TCF3−/− ESC still expressed self renewal genes, such as Nanog and Oct4, which suggested they had retained an undifferentiated status (Figure 1B, 1C), and adapted TCF3−/− ESC had previously been shown to possess the ability to differentiate into all three germ layers through in vitro differentiation assays[18]. We conclude from these results that the adaptation process confers an ability to stimulate phosphorylation of Stat3, which was independent of exogenously added Lif ligand.

To examine the kinetics of this aspect of adaptation, we measured phospho-Stat3 levels in cultures following a switch to Lif− conditions. Western blot analysis of protein samples taken from cells prior to each passage revealed that Stat3 was not significantly phosphorylated in TCF3−/− ESC during the first two passages in Lif− media (Figure 1C). Somewhat surprisingly, the TCF3+/+ ESC exhibited Stat3 phosphorylation, albeit a low level, at the end of the second passage. This low level Stat3 phosphorylation was not sufficient to rescue self renewal as the TCF3+/+ cells had lost its Oct4 expression (Figure 1C) and proliferative capacity (Figure 4) by this point in the experiment. Stat3 phosphorylation in TCF3−/− ESC first became apparent by the end of the third passage in Lif− media (P3, Figure 1C). Interestingly, this timing corresponded to the point at which TCF3−/− ESC began to recover their rate of proliferation (Figure 4) [18]. Although the level is lower than both TCF3+/+ and naïve TCF3−/− ESC maintained in Lif+ media, the Stat3 phosphorylation in adapted TCF3−/− ESC was stable in Lif− media through long-term culture (shown is 10 passages, Figure 1B, 1C). Although adapted TCF3−/− ESC continued to proliferate for as long as we continued passaging cells (two months was the longest period), they appeared to exhibit a slight proliferation deficit relative to either TCF3+/+ or TCF3−/− ESC grown in Lif+ media. To examine this potential defect, the doubling time for each cell was calculated by averaging data from five successive passages. Adapted TCF3−/− ESC displayed a slightly increased doubling time relative to cells maintained in Lif+ conditions (Figure 1D). Flow cytometry measurement of DNA content in self renewing cultures suggested that the slightly decreased proliferation rate was caused by a minor delay at G2 and G2/M stages of the cell cycle of adapted TCF3−/− cells (Figure 1D). Both of these differences in proliferation and cell cycle were quite small, yet reproducible in three separate derivations of adapted TCF3−/− ESC (data not shown). Considering the complete failure of TCF3+/+ cells to proliferate without exogenous Lif, adapted TCF3−/− ESC were remarkable in that they self renewed with such similar kinetics to TCF3+/+ ESC cultured in the presence of 1000 U/ml Lif.

Figure 4. Adaptation of TCF3−/− ESC in long-term Lif− culture occurs without Jak activity.

TCF3+/+ and naïve TCF3−/− ESC were passaged in Lif− culture with or without 1.0 μM pyridone 6. The numbers of cells were counted at the end of each passage. Each column represents a mean number of total cell counts in duplicated assays with standard deviation. TCF3+/+ ESC failed to proliferate and underwent apoptosis during the first three passages. Treatment with 1.0μM pyridone 6 reduced the proliferation of naïve TCF3−/− ESC throughout the assay but did not prevent the naïve TCF3−/− ESC from adapting to Lif− culture.

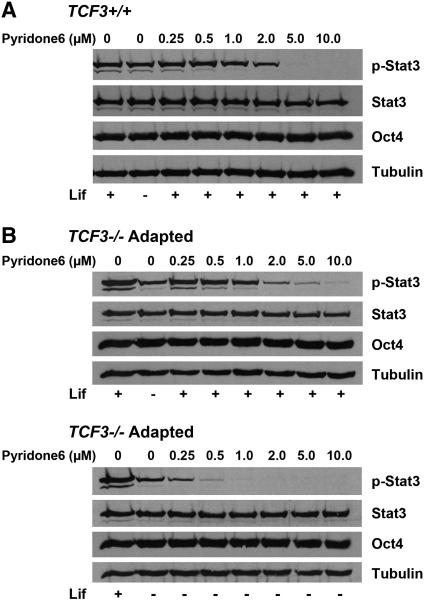

Phosphorylation of Stat3 in adapted TCF3−/− ESC is blocked by the Jak kinase inhibitor, pyridone 6

To determine what effect, if any, the constitutive phosphorylation of Stat3 has on the characteristics of adapted TCF3−/− ESC, we sought methods of blocking Stat3 phosphorylation. Two inhibitors of Jak kinase activity were tested. Tryphostin AG490 inhibited Jak2 activity, and other tyrosine kinases, in acute lymphoblastic leukemia cells [22, 23]. TCF3+/+ ESC treated with AG490 in Lif+ media displayed poor long-term viability at inhibitor concentrations (10 μM) much lower than those required to diminish Stat3 phosphorylation (50 μM) (data not shown), thus making its use problematic for interpreting effects of Stat3 phosphorylation. Tetracyclic pyridone 6 specifically inhibited Jak kinase activity in multiple myeloma cells [24]. TCF3+/+ ESC treated with 5.0 μM pyridone 6 in Lif+ media had levels of phospho-Stat3 below detection by Western blot (Figure 2A). Stat3 phosphorylation was similarly inhibited in adapted TCF3−/− ESC in Lif+ media (Figure 2B); however, there was a slight but reproducible presence of phospho-Stat3 in adapted TCF3−/− ESC treated with 5.0 μM pyridone 6 in Lif+ media, suggesting higher levels of Jak activity in adapted TCF3−/− ESC relative to TCF3+/+ ESC (Figure 2A) or naïve TCF3−/− ESC (data not shown) when they were stimulated with equivalent amounts of Lif. In contrast, much lower concentrations of pyridone 6 were needed to inhibit Stat3 phosphorylation in adapted TCF3−/− ESC in Lif− media; phospho-Stat3 immunoreactivity was not detectable in adapted TCF3−/− ESC in Lif− media after treatment with 0.5-1.0 μM pyridone 6 (Figure 2B). Combined with previous reports of pyridone 6 specificity for Jak kinases, we concluded that it was effective at specifically inhibiting Jak phosphorylation of Stat3 in ESC and that Stat3 phosphorylation in Lif− media required Jak activity in adapted TCF3−/− ESC.

Figure 2. Jak Kinase activity is necessary for Stat3 phosphorylation in adapted TCF3−/− ESC.

Western blot analysis for the indicated antigens (right) was performed using protein lysates after six hours of pyridone 6 treatment. A) 5.0-10.0 μM Jak kinase specific inhibitor pyridine 6 inhibited Stat3 phosphorylation of TCF3+/+ ESC in Lif+ culture. B) Upper panel: 5.0-10.0 μM pyridone 6 similar inhibited the Stat3 phosphorylation in adapted TCF3−/− ESC in Lif+ culture comparing to the TCF3+/+ ESC, but a higher concentration was needed to achieve a complete inhibition; Lower panel: 0.5-1.0 μM pyridone 6 inhibited the phosphorylation of Stat3 in adapted TCF3−/− ESC in Lif− culture.

Since pyridone 6 abolished Stat3 phosphorylation in TCF3−/− ESC, we used it as a means of elucidating effects of Stat3 phosphorylation on the maintenance of stem cell characteristics in adapted TCF3−/− ESC. First, we determined whether adapted TCF3−/− ESC could continue self renewal in the absence of detectable Stat3 phosphorylation by passaging cells in Lif− media containing 0-1.0 μM pyridone 6 (Figure 3A). Total cell numbers at each passage were reduced with 0.5-1.0 μM pyridone 6 throughout the course of this experiment (Figure 3A), and the doubling time was increased from 15.2 +/− 0.28 hours without pyridine 6 to 18.7 +/− 0.41 hours in 1.0 μM pyridine 6. Despite the decreased cell proliferation, expression of stem cell markers, Nanog and Oct4, were not affected by high concentration of pyridone 6 even after five repeated passages in the presence of the inhibitor (Figure 3B). This effect was not due to a resistance to the inhibitor because Stat3 phosphorylation was consistently and effectively blocked through five passages (Figure 3B). Alkaline phosphatase staining of colonies at the end of the fifth passage revealed that pyridone 6 altered the morphology of colonies such that were slightly flatter and maintained AP activity; however, the inhibitor did not significantly increase the apparence of differentiated colonies (green + purple bars together; Figure 3C, D). Taken together with the maintenance of Oct4 and Nanog expression, the maintenance of an ESC morphology suggested that Jak phosphorylation of Stat3 was not necessary for self renewal of adapted TCF3−/− ESC. In contrast, Jak phosphorylation of Stat3 was necessary for a high rate of cell proliferation in adapted TCF3−/− ESC.

Figure 3. Adapted TCF3−/− ESC self renew under blockade of Jak phosphorylation of Stat3.

Adapted TCF3−/− ESC were treated with 0-1.0 μM of pyridone 6 in Lif− culture (A-D). A) Total numbers of cells were counted at the end of each passage(P#). Each column represents a mean number of total cell counts in duplicated assays with standard deviation. B) Western blot analysis of protein samples isolated at the end of the fifth passage (P5). Adapted TCF3−/− ESC lost the Stat3 phosphorylation with 0.5-1.0 μM pyridone 6 while the expression of Nanog and Oct4 were not affected by pyridone 6. C) Percentages of alkaline phosphatase-positive colonies were determined at the end of the fifth passage (P5). Inhibition of Stat3 phosphorylation by pyridone 6 affected the morphology of colonies without substantially increasing the percentage of differentiated colonies. D) Key for different categories of colonies counted for graphs in panel C.

In the experiments where naïve TCF3−/− ESC were subjected to long-term Lif− media, Stat3 phosphorylation (Figure 1B) was first detected at the same time (passage 3, P3) after which proliferation rates began to increase (Figure 4; red bars) [18]. While this observation suggested a role for Jak/Stat3 activity in stimulating proliferation of adapted TCF3−/− ESC, it also raised the possibility that ectopic Stat3 phosphorylation could be the underlying mechanism that allowed adapted cells to survive Lif− conditions. To distinguish between these two possibilities, TCF3+/+ and naïve TCF3−/− ESC were passaged in Lif− media in the presence of 1.0 μM pyridone 6 (Figure 4), which blocked Stat3 phosphorylation at every point during the adaptation process. In control Lif− conditions without pyridone 6, naïve TCF3−/− ESC continued to self renew and TCF3+/+ ESC failed to self renew past the third passage (Figure 4) [18]. Adding 1.0 μM pyridone 6 did not significantly worsen survival TCF3+/+ cells in this assay, suggesting that removal of exogenous Lif was sufficient to cause the same effects as directly blocking Stat3 phosphorylation in TCF3+/+ ESC, which is consistent with a negligible effect from the low level of phospho-Stat3 observed at the end of P2 in Figure 1C. Similarly, adding pyridone 6 also had little effect on the proliferation of naïve TCF3−/− ESC during the first three passages following Lif withdrawal. In contrast, after the third passage pyridone 6-treated TCF3−/− ESC maintained relatively poor proliferation rates relative to vehicle-treated TCF3−/− ESC controls (Figure 4). Taken together, these data confirmed that pyridone 6-sensitive Jak activity was not necessary for maintenance of self renewal in adapted TCF3−/− ESC, but it was important to stimulate proliferation of the stem cells.

Stat3 phosphorylation in adapted TCF3−/− ESC is independent of endogenous Lif and LifR

To begin to elucidate the mechanism underlying the Jak kinase phosphorylation of Stat3 in the absence of exogenous Lif, we examined whether ligand binding at LifR complexes could be increased in adapted TCF3−/− ESC. First, we determined if the levels of either Lif or LifR were increased in TCF3−/− ESC with quantitative real-time RT-PCR (qPCR) of mRNA. Levels of Lif and LifR mRNA in mouse embryonic fibroblasts (MEFs) were used to evaluate significance of any potential differences, because MEFs secrete levels of Lif that are sufficient to support wild type ESC self renewal [15]. TCF3+/+, naïve TCF3−/−, and adapted TCF3−/− ESC all expressed similar low levels of Lif (Figure 5A). Compared to MEFs, the low levels of Lif expressed by adapted TCF3−/− ESC were not substantial, and unlikely to contribute sufficient pathway activation to support Stat3 phosphorylation and self renewal observed in adapted TCF3−/− ESC. Although naïve TCF3−/− ESC expressed a higher level of LifR, TCF3+/+ and adapted TCF3−/− ESC expressed levels that were not statistically significantly different (Figure 5B). Thus, the constitutive Jak kinase phosphorylation of Stat3 in adapted TCF3−/− ESC in Lif− media was not caused by increased transcription of genes encoding Lif or LifR.

Figure 5. Lif and LifR were not upregulated in the adapted TCF3−/− ESC.

Quantitative real-time RT PCR (qPCR) was used to measure the levels of Lif and LifR mRNA. A) Comparing to the mouse embryonic fibroblasts (MEFs) and TCF3+/+ ESC, both naïve and adapted TCF3−/− ESC did not express sufficient levels of Lif to support Stat3 phosphorylation and self renewal. B) The LifR level was also not significantly higher in adapted TCF3−/− ESC comparing to TCF3+/+ ESC.

To determine if stimulation of LifR activity occurred independently of Lif or LifR gene transcription, LifR activity was pharmacologically inhibited. The Lif antagonist (named Q29A&G124R MH35-BD) was designed to possess a higher affinity for LifR (>1000 fold higher than wild-type human Lif) and to harbor point mutations preventing its binding to the gp130 co-receptor; this combination results in an effective abrogation of LifR-activation of downstream Jak kinases [25]. Purified recombinant Lif antagonist (LA) was tested for its ability to inhibit Stat3 phosphorylation in the presence of 1000 U/ml Lif. TCF3+/+ and naive TCF3−/− ESC displayed similar sensitivity to the antagonist, as phosphorylation of Stat3 was inhibited by 10 nM concentration of the inhibitor (Figure 6A, B). Although phospho-Stat3 immunoreactivity was decreased in adapted TCF3−/− ESC treated with LA in the absence of exogenous Lif, phosphorylation of Stat3 was readily detectable from samples treated with 10 nM LA (Figure 6C). When considered together with the observation that adapted TCF3−/− ESC in Lif− media were sensitive to 10-fold lower concentrations of pyridone 6 than cells in Lif+ media (Figure 2), the maintenance of Stat3 phosphorylation in 10 nM LA suggested that the Jak activity in adapted TCF3−/− ESC was at least partially independent of LifR-ligand binding. To examine this possibility more directly, phospho-Stat3 levels were directly compared by Western blot analysis of several samples separated on the same gel (Figure 6D). This analysis confirmed that the level of Stat3 phosphorylation was lower in adapted TCF3−/− ESC without Lif compared to TCF3+/+ ESC with 1000 U/ml Lif. The lower baseline level allowed a lower concentration (1 μM) of pyridone 6 to completely block Stat3 phosphorylation in adapted TCF3−/− ESC compared to TCF3+/+ ESC in 1000 U/ml. In contrast, the same concentration of LA was required to inhibit Stat3 phosphorylation in both adapted TCF3−/− ESC and TCF3+/+ in 1000 U/ml. We conclude that the LA was relatively less effective on adapted TCF3−/− ESC, suggesting that Stat3 phosphorylation was partially independent of the LifR target of LA in adapted TCF3−/− ESC.

Figure 6. Stat3 phosphorylation in adapted TCF3−/− ESC is partially LifR-independent.

Western blot analysis of TCF3+/+ and TCF3−/− ESC in Lif+ culture and adapted TCF3−/− ESC in Lif− culture treated with 0-10 nM Lif antagonist (LA) (A-C). A) 1-10 nM LA blocked the Stat3 phosphorylation in TCF3+/+ ESC in Lif+ culture. B) 1-10 nM LA blocked the Stat3 phosphorylation in TCF3−/− ESC in Lif+ culture. C) 1-10 nM LA diminished but did not completely block the Stat3 phosphorylation in adapted TCF3−/− ESC in Lif− culture. D) Western blot analysis of TCF3+/+ ESC in Lif+ culture and adapted TCF3−/− ESC in Lif− culture under either pyridone 6 or LA treatment. 1 μM pyridone 6 completely blocked Stat3 phosphorylation in adapted TCF3−/− ESC but only caused a minor decrease in TCF3+/+ ESC; while 1 nM and 10 nM LA decreased the Stat3 phosphorylation in both TCF3+/+ and adapted TCF3−/− ESC to comparable levels.

Lif-independent Stat3 phosphorylation occurred non-cell-autonomously

Based on the results of the previous experiments, we posited that the Lif-independent phosphorylation of Stat3 in adapted TCF3−/− ESC could be caused either by a cell-intrinsic stimulation of Jak activity at the level of gp130-coreceptor complexes or by a non-cell-autonomous mechanism most likely involving the secretion of paracrine factor(s) that do not require LifR for signaling. To distinguish between these two mechanisms, we first utilized the ability to rapidly reduce Stat3 phosphorylation by washing Lif-containing media from cells as shown in Figure 1A and reasoned that a non-cell-autonomous mechanisms would be more likely to be inhibited by washing than a cell-intrinsic mechanism. In fresh Lif− media, Stat3 phosphorylation was rapidly lost similarly in adapted TCF3−/− ESC, naïve TCF3−/−, and TCF3+/+ ESC (Figure 7A). Once Lif+ media was added for 30 minutes, the Stat3 phosphorylation in adapted TCF3−/− ESC recovered to a level as high as TCF3+/+ and TCF3−/− ESC. This result indicated the adapted TCF3−/− ESC retained the ability to respond normally to exogenous Lif. More importantly, these data were most consistent with a non-cell-autonomous mechanism causing the ectopic Stat3 phosphorylation in adapted TCF3−/− ESC.

Figure 7. Lif-independent Stat3 phosphorylation occurred non-cell-autonomously.

A) Similar to Figure 1A, Western blot analysis for Stat3 phosphorylation in short-term Lif withdrawal assay. TCF3+/+, TCF3−/− were cultured in media containing 1000 U/ml Lif (Lif+) while adapted TCF3−/− ESC were cultured without supplemented Lif (Lif−) for 24 hours. All cells were washed twice by PBS and fed with media without supplemented Lif (Lif−). Protein samples were isolated at indicated time points. Phosphorylation of Stat3 was diminished in all three ESC lines 15 and 30 minutes after Lif withdrawal, and returned to normal levels within 30 minutes when switch back to the Lif+ media. B-D) Indirect immunofluorescent staining for Tcf3 (Red; B) or phosphoStat3 (Red; C-D). B) Individual colony from TCF3+/+ ESC and EGFP-labeled adapted TCF3−/− ESC mixed-culture exhibited mosaic patterns of expression of Tcf3 (Red) and EGFP (Green). Multiple colonies were shown for staining (C-D). C) Stat3 phosphorylation (Red) in TCF3+/+ and TCF3−/− ESC was detected in Lif+ culture (upper two panels) and absent from Lif− culture (middle two panels). In Lif− culture, Stat3 was phosphorylated in adapted TCF3−/− ESC and the EGFP (Green) was ubiquitously expressed (bottom panel). D) Stat3 was uniformly phosphorylated in all cells in individual colonies in mixed-culture of TCF3+/+ (upper panel) or TCF3−/− (lower panel) ESC with adapted TCF3−/− ESC in the absence of Lif. EGFP was detected in a mosaic pattern in the culture confirming the mixture of cell types in individual colonies.

To determine whether non-cell-autonomous effects were sufficient for Lif-independent Stat3 phosphorylation in adapted TCF3−/− ESC, a simple cell mixing experiment was performed. We fluorescently-labeled adapted TCF3−/− ESC by stably transfecting them with an EGFP-expressing plasmid. Single cell suspensions of EGFP+ adapted TCF3−/− ESC were mixed together with either unlabeled naïve TCF3−/− or unlabeled TCF3+/+ ESC, and cells were plated at concentrations such that most colonies would be a mosaic formed from multiple cells. Immunofluorescent detection of Tcf3 (from TCF3+/+ ESC) and EGFP (from adapted TCF3−/− ESC) confirmed the efficient mixing of cell types within individual colonies (Figure 7B).

The phosphorylation of Stat3 was examined in individual cells in ESC colonies by indirect Immunofluorescence staining. As expected, Stat3 phosphorylation was detected in >90% of TCF3+/+ and naïve TCF3−/− cells in Lif+ media, and it was not detected in these cells after 48 hrs in Lif− media (Figure 7C). Adapted TCF3−/− ESC maintained phosphorylated Stat3 immunoreactivity in Lif− media (Figure 7C), which is consistent with Western blot data (Figure 1). When TCF3+/+ or naïve TCF3−/− ESC were mixed with adapted TCF3−/− EGFP+ ESC and placed in Lif− media, most colonies consisted of a mixture of both cell types, as detected by a mosaic EGFP pattern, yet the colonies displayed uniform phospho-Stat3 immunoreactivity (Figure 7D). Phospho-Stat3 immunoreactivity was lost in cells treated with pyridone 6 (data not shown). Taken together with the reduction in Stat3 phosphorylation after washing adapted TCF3−/− ESC with fresh media (Figure 7A), these data indicate that adapted TCF3−/− secrete into media paracrine factor(s) capable of stimulating proliferation and potentially self renewal of ESC.

DISCUSSION

Data presented here build upon our previously published observation that TCF3−/− ESC could indefinitely self renew in the absence of exogenous Lif [18]. Comparison of naïve and adapted TCF3−/− ESC revealed an induction of Lif-independent activation of Stat3-phosphorylation In TCF3−/− ESC only after extended Lif− culture. This Lif-independent phosphorylation of Stat3 stimulated proliferation of the stem cells; however, it was not necessary for maintenance of stem cell markers Nanog and Oct4 in either naïve or adapted TCF3−/− ESC because those markers were present in TCF3−/− ESC treated with the Jak kinase inhibitor pyridone 6 for several passages.

Although the definitive molecular markers of ESC identity were maintained, pyridone 6 treatment altered the morphology of colonies by causing them to be less compact. Thus, it is possible that pyridone 6 treatment could have compromised the pluripotency of adapted TCF3−/− cells. It is important to point out that based on the stability of colony morphology and stem cell marker gene expression over the course of five passages, the adapted TCF3−/− cells did not change significantly through multiple divisions. These data suggest that even if pyridone 6 inhibited pluripotency, the cells appeared to retain the important characteristic of self renewal.

Adaptation of TCF3−/− ESC to Lif− media involved the upregulation of secreted factor that stimulated Stat3 phosphorylation and cell proliferation in a cell non-autonomous manner. Although the identification of the factor(s) is beyond the scope of the present study, the partial inhibition of Stat3 phosphorylation by the Lif antagonist experiments suggested that the factor(s) can signal both through the LifR and independently of LifR to activate Jak phosphorylation of Stat3. The pyridone 6 inhibitor experiments showed that Stat3 phosphorylation was dependent on Jak kinase activity. Taken together, these data suggest that the secreted factor(s) can stimulate multiple receptor complexes, including LifR-gp130, leading to the activation of Jak kinases.

One potentially important observation is that the ablation of Tcf3 allowed stem cells to overcome changing extracellular stimuli, and to adapt to a highly proliferative outcome. Given the role of the niche in regulating stem cell characteristics, these new findings suggest the potential for Wnt/β-catenin/Tcf signaling to stimulate niche-independent proliferation of stem cells. Essentially, ablation of Tcf3 allowed ESC to adapt and generate their own extracellular, niche-like, signals to stimulate proliferation. The mechanism underlying this process is not known; however, it was shown to be reversible by returning adapted TCF3−/− ESC to Lif+ media [18]. It is tempting to speculate that an increased malleability of epigenetic regulation could account for adaptability of TCF3−/− ESC.

Considering the molecular activity of Tcf3 in stem cells, the adaptation process revealed here offers potential for a new perspective on Wnt/β-catenin signaling in cancer. The process of adapting to Lif− conditions selected for TCF3−/− ESC that had activated factors supporting rapid self renewal. The observation that this only occurred in TCF3−/− ESC and not TCF3+/+ ESC suggested that the presence of Tcf3 inhibited the adaptation process. Several studies examining Tcf3 regulation of target genes and effects of Wnt-β-catenin on gene expression in ESC showed that Tcf3 functioned as a transcriptional repressor of stem cell self renewal circuitry and opposed effects of Wnt-stabilized β-catenin [18-20]. Genetic data have also attributed repressor activities to Tcf3-function during gastrulation in the mouse [26] and frog [27], for anterior neural patterning in the fish [28], and in hair follicle stem cells in the mouse [26]. Given the absence of Tcf3 and Wnt-β-catenin activated caused an overlapping set of effects on gene expression in ESC [19], it is reasonable to suggest activation of Wnt signaling would allow cells to undergo an adaptation process similar to TCF3−/− ESC.

It is interesting to consider these results in terms of how they may pertain to cancer and changes occurring in cancer cells during the life of a tumor. Activation of Stat3 signaling has been reported for a broad cross-section of human tumors [29]. Recent studies reported high IL-6 levels in the serum of breast and lung cancer patients, and high IL-6 levels correlated with poor clinical prognosis [30]. Serum IL-6 levels correlated with clinicopathological factors of colorectal cancer, including tumor size, cell proliferation, and liver metastasis [31, 32]. Interestingly, in tumor bearing APC+/min mice, serum IL-6 levels were increased relative to non-tumor bearing mice, and the serum levels of IL-6 were quantitatively proportional to the intestinal tumor burden both in number of polyps and size of polyps [33]. Moreover, genetic ablation of IL-6 significantly reduced tumor growth and number in APC+/min mice [33]. These in vivo observations are consistent our findings that removal of Tcf3-repression allowed upregulation of extracellular stimulators of Jak/Stat3, and they suggest potential for future examination of the role of Jak/Stat3 activation in proliferation of colon cancer stem cells.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank the members of the Merrill Lab for their helpful discussions and thoughtful comments on the manuscript, Battuya Bayarmagnai for assistance in performing the Lif-antagonist experiments, Dr. Jian-Guo Zhang (The Walter and Eliza Hall Institute of Medical Research, Australia) for the Lif antagonist expression construct, and the UIC Flow Cytometry Facility for their expert assistance with experimental methods. The work was funded by grants from the American Cancer Society (RSG GGC 112994) and the National Institutes of Health (R01-CA128571).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

REFERENCES

- 1.Nusse R. Wnt signaling and stem cell control. Cell Res. 2008;18:523–527. doi: 10.1038/cr.2008.47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Brannon M, Gomperts M, Sumoy L, Moon RT, Kimelman D. A beta-catenin/XTcf-3 complex binds to the siamois promoter to regulate dorsal axis specification in Xenopus. Genes Dev. 1997;11:2359–2370. doi: 10.1101/gad.11.18.2359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Molenaar M, van de Wetering M, Oosterwegel M, Peterson-Maduro J, Godsave S, Korinek V, Roose J, Destree O, Clevers H. XTcf-3 transcription factor mediates beta-catenin-induced axis formation in Xenopus embryos. Cell. 1996;86:391–399. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80112-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.van de Wetering M, Cavallo R, Dooijes D, van Beest M, van Es J, Loureiro J, Ypma A, Hursh D, Jones T, Bejsovec A, Peifer M, Mortin M, Clevers H. Armadillo coactivates transcription driven by the product of the Drosophila segment polarity gene dTCF. Cell. 1997;88:789–799. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81925-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tutter AV, Fryer CJ, Jones KA. Chromatin-specific regulation of LEF-1-beta-catenin transcription activation and inhibition in vitro. Genes Dev. 2001;15:3342–3354. doi: 10.1101/gad.946501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Willert K, Jones KA. Wnt signaling: is the party in the nucleus? Genes Dev. 2006;20:1394–1404. doi: 10.1101/gad.1424006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Reya T, Duncan AW, Ailles L, Domen J, Scherer DC, Willert K, Hintz L, Nusse R, Weissman IL. A role for Wnt signalling in self-renewal of haematopoietic stem cells. Nature. 2003;423:409–414. doi: 10.1038/nature01593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gat U, DasGupta R, Degenstein L, Fuchs E. De Novo hair follicle morphogenesis and hair tumors in mice expressing a truncated beta-catenin in skin. Cell. 1998;95:605–614. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81631-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Korinek V, Barker N, Moerer P, van Donselaar E, Huls G, Peters PJ, Clevers H. Depletion of epithelial stem-cell compartments in the small intestine of mice lacking Tcf-4. Nat Genet. 1998;19:379–383. doi: 10.1038/1270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sato T, Vries RG, Snippert HJ, van de Wetering M, Barker N, Stange DE, van Es JH, Abo A, Kujala P, Peters PJ, Clevers H. Single Lgr5 stem cells build crypt-villus structures in vitro without a mesenchymal niche. Nature. 2009;459:262–265. doi: 10.1038/nature07935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sato N, Meijer L, Skaltsounis L, Greengard P, Brivanlou AH. Maintenance of pluripotency in human and mouse embryonic stem cells through activation of Wnt signaling by a pharmacological GSK-3-specific inhibitor. Nat Med. 2004;10:55–63. doi: 10.1038/nm979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Morin PJ. beta-catenin signaling and cancer. Bioessays. 1999;21:1021–1030. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1521-1878(199912)22:1<1021::AID-BIES6>3.0.CO;2-P. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Barker N, Ridgway RA, van Es JH, van de Wetering M, Begthel H, van den Born M, Danenberg E, Clarke AR, Sansom OJ, Clevers H. Crypt stem cells as the cells-of-origin of intestinal cancer. Nature. 2009;457:608–611. doi: 10.1038/nature07602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Peerani R, Onishi K, Mahdavi A, Kumacheva E, Zandstra PW. Manipulation of signaling thresholds in “engineered stem cell niches” identifies design criteria for pluripotent stem cell screens. PLoS ONE. 2009;4:e6438. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0006438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Williams RL, Hilton DJ, Pease S, Willson TA, Stewart CL, Gearing DP, Wagner EF, Metcalf D, Nicola NA, Gough NM. Myeloid leukaemia inhibitory factor maintains the developmental potential of embryonic stem cells. Nature. 1988;336:684–687. doi: 10.1038/336684a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Smith AG, Heath JK, Donaldson DD, Wong GG, Moreau J, Stahl M, Rogers D. Inhibition of pluripotential embryonic stem cell differentiation by purified polypeptides. Nature. 1988;336:688–690. doi: 10.1038/336688a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ying QL, Wray J, Nichols J, Batlle-Morera L, Doble B, Woodgett J, Cohen P, Smith A. The ground state of embryonic stem cell self-renewal. Nature. 2008;453:519–523. doi: 10.1038/nature06968. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yi F, Pereira L, Merrill BJ. Tcf3 Functions as a Steady State Limiter of Transcriptional Programs of Mouse Embryonic Stem Cell Self Renewal. Stem Cells. 2008 doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2008-0229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cole MF, Johnstone SE, Newman JJ, Kagey MH, Young RA. Tcf3 is an integral component of the core regulatory circuitry of embryonic stem cells. Genes Dev. 2008;22:746–755. doi: 10.1101/gad.1642408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tam WL, Lim CY, Han J, Zhang J, Ang YS, Ng HH, Yang H, Lim B. Tcf3 Regulates Embryonic Stem Cell Pluripotency and Self-Renewal by the Transcriptional Control of Multiple Lineage Pathways. Stem Cells. 2008 doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2007-1115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pereira L, Yi F, Merrill BJ. Repression of nanog gene transcription by tcf3 limits embryonic stem cell self-renewal. Mol Cell Biol. 2006;26:7479–7491. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00368-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Meydan N, Grunberger T, Dadi H, Shahar M, Arpaia E, Lapidot Z, Leeder JS, Freedman M, Cohen A, Gazit A, Levitzki A, Roifman CM. Inhibition of acute lymphoblastic leukaemia by a Jak-2 inhibitor. Nature. 1996;379:645–648. doi: 10.1038/379645a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wang LH, Kirken RA, Erwin RA, Yu CR, Farrar WL. JAK3, STAT, and MAPK signaling pathways as novel molecular targets for the tyrphostin AG-490 regulation of IL-2-mediated T cell response. J Immunol. 1999;162:3897–3904. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pedranzini L, Dechow T, Berishaj M, Comenzo R, Zhou P, Azare J, Bornmann W, Bromberg J. Pyridone 6, a pan-Janus-activated kinase inhibitor, induces growth inhibition of multiple myeloma cells. Cancer Res. 2006;66:9714–9721. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-4280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fairlie WD, Uboldi AD, McCoubrie JE, Wang CC, Lee EF, Yao S, De Souza DP, Mifsud S, Metcalf D, Nicola NA, Norton RS, Baca M. Affinity maturation of leukemia inhibitory factor and conversion to potent antagonists of signaling. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:2125–2134. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M310103200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Merrill BJ, Pasolli HA, Polak L, Rendl M, Garcia-Garcia MJ, Anderson KV, Fuchs E. Tcf3: a transcriptional regulator of axis induction in the early embryo. Development. 2004;131:263–274. doi: 10.1242/dev.00935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Houston DW, Kofron M, Resnik E, Langland R, Destree O, Wylie C, Heasman J. Repression of organizer genes in dorsal and ventral Xenopus cells mediated by maternal XTcf3. Development. 2002;129:4015–4025. doi: 10.1242/dev.129.17.4015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kim CH, Oda T, Itoh M, Jiang D, Artinger KB, Chandrasekharappa SC, Driever W, Chitnis AB. Repressor activity of Headless/Tcf3 is essential for vertebrate head formation. Nature. 2000;407:913–916. doi: 10.1038/35038097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Al Zaid Siddiquee K, Turkson J. STAT3 as a target for inducing apoptosis in solid and hematological tumors. Cell Res. 2008;18:254–267. doi: 10.1038/cr.2008.18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hong DS, Angelo LS, Kurzrock R. Interleukin-6 and its receptor in cancer: implications for Translational Therapeutics. Cancer. 2007;110:1911–1928. doi: 10.1002/cncr.22999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chung YC, Chang YF. Serum interleukin-6 levels reflect the disease status of colorectal cancer. J Surg Oncol. 2003;83:222–226. doi: 10.1002/jso.10269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Corvinus FM, Orth C, Moriggl R, Tsareva SA, Wagner S, Pfitzner EB, Baus D, Kaufmann R, Huber LA, Zatloukal K, Beug H, Ohlschlager P, Schutz A, Halbhuber KJ, Friedrich K. Persistent STAT3 activation in colon cancer is associated with enhanced cell proliferation and tumor growth. Neoplasia. 2005;7:545–555. doi: 10.1593/neo.04571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Baltgalvis KA, Berger FG, Pena MM, Davis JM, Muga SJ, Carson JA. Interleukin-6 and cachexia in ApcMin/+ mice. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2008;294:R393–401. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00716.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]