Abstract

Lung surfactant (LS) is a mixture of lipids and proteins that line the alveolar air-liquid interface, lowering the interfacial tension to levels that make breathing possible. In acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS), inactivation of LS is believed to play an important role in the development and severity of the disease. This review examines the competitive adsorption of LS and surface-active contaminants, such as serum proteins, present in the alveolar fluids of ARDS patients, and how this competitive adsorption can cause normal amounts of otherwise normal LS to be ineffective in lowering the interfacial tension. LS and serum proteins compete for the air-water interface when both are present in solution either in the alveolar fluids or in a Langmuir trough. Equilibrium favors LS as it has the lower equilibrium surface pressure, but the smaller proteins are kinetically favored over multi-micron LS bilayer aggregates by faster diffusion. If albumin reaches the interface, it creates an energy barrier to subsequent LS adsorption that slows or prevents the adsorption of the necessary amounts of LS required to lower surface tension. This process can be understood in terms of classic colloid stability theory in which an energy barrier to diffusion stabilizes colloidal suspensions against aggregation. This analogy provides qualitative and quantitative predictions regarding the origin of surfactant inactivation. An important corollary is that any additive that promotes colloid coagulation, such as increased electrolyte concentration, multivalent ions, hydrophilic non-adsorbing polymers such as PEG, dextran, etc. or polyelectrolytes such as chitosan, added to LS, also promotes LS adsorption in the presence of serum proteins and helps reverse surfactant inactivation. The theory provides quantitative tools to determine the optimal concentration of these additives and suggests that multiple additives may have a synergistic effect. A variety of physical and chemical techniques including isotherms, fluorescence microscopy, electron microscopy and X-ray diffraction show that LS adsorption is enhanced by this mechanism without substantially altering the structure or properties of the LS monolayer.

Keywords: charge reversal, chitosan, inhibition, depletion attraction, albumin, polyethylene glycol, Debye length

Introduction: Why Lung Surfactant?

The human lung bifurcates into numerous channels (bronchi and bronchioles) terminating in sub-millimeter diameter spherical, liquid-coated chambers [1], called alveoli, in which gas exchange occurs. The surface area in adult lungs is ~ 70 m2, about half the area of a tennis court [2–5]. This enormous surface area maximizes the exchange of oxygen and carbon dioxide between air and blood, but air-water interfaces of this size contribute a potentially significant drain on metabolic energy as the interface expands and contracts against surface tension. Nature has minimized this energy drain by coating the lung air-water interface with a thin film of lipids and proteins, collectively called lung surfactant (LS).

LS is composed of 90% lipids (primarily dipalmitoylphosphatidylcholine, DPPC) and 10% of four lung surfactant specific proteins (SP-A, B, C, and D) [2–9]. Lung surfactant, like other surface-active substances, adsorbs spontaneously to an air-water interface because doing so lowers the energy of the interface [10]. Lung surfactant continues to adsorb until the normal air-water surface tension, γ, of ~ 70 mN/m (dyne/cm) decreases to ~ 30 mN/m at equilibrium [11, 12]; this equilibrium surface tension is similar for native and most clinical replacement surfactants [13]. In normal lungs, after secretion of LS in the form of multilamellar bodies from alveolar type II cells [14–16] surfactant must unpack, move across the alveolar hypophase, adsorb to the air-water interface, and then transform from bilayer to monolayer and spread over the interface [4]. Similarly, exogenous surfactant, introduced into the airway of a patient with lung disease, must travel to the periphery of the lung, adsorb and spread to cover the air-liquid interface, despite the presence of any other surface-active materials present in the alveoli. For both normal and exogenous surfactant, adsorption through the liquid subphase is the primary route of surfactant accumulation at the interface.

Why is this reduction in equilibrium surface tension so important to breathing? Surface tension causes the pressure in an air bubble (Pin) of radius, R, (a simple model for an alveolus with radius R) within a confining liquid (Pout) to increase according to Laplace’s equation: Pin − Pout = ΔP ≈ 2γ/R. Breathing is initiated by motion of the diaphragm, which induces a negative pressure (vacuum) on the outsides of the alveoli (Pout); during breathing, the ambient pressure, Pam, must be less than the pressure inside the alveoli, Pin, so that air can flow into the alveoli and gas exchange can occur. During breathing, the increase in pressure in the alveolus due to surface tension, ΔP ≈ 2γ/R, must be such that an overall negative pressure (Pin − Pam < 0) remains between the air inside and outside the body so that air flows into the lungs. Hence, surface tension requires that the diaphragm generate a lower pressure (greater vacuum) so that Pout + 2γ/R = Pin < Pam, a lower pressure than would be necessary in the absence of surface tension. The lower the surface tension, γ, the less force (Force = Pressure × surface area of lung) must be developed by the motion of the diaphragm, and the less work (Work = Force × Distance) is necessary for breathing. If the diaphragm cannot generate the necessary vacuum, air no longer flows into the lungs; if too much work is required to generate this vacuum, little energy is left for anything else. Simply put, the evolution of air-breathing required the co-evolution of lung surfactant [17].

A second consideration necessitating lung surfactant is that at any given time during breathing, different alveoli will be in different states of inflation. This means different values of R, different Laplace pressures, ΔP ≈ 2γ/R, and different values of Pin in different alveoli, with the less inflated, smaller alveoli having the larger Pin. Hence, the smaller alveoli tend to get even smaller and eventually collapse, and their high-pressure gas contents flow to the larger alveoli with their smaller pressures [18]. The corresponding liquid layer thickens in the less inflated alveoli, because the corresponding Laplace pressure inside the liquid in the deflated alveoli is less than in the liquid lining more inflated alveoli. The net result is that the smallest alveoli can collapse and fill with liquid and become difficult to re-inflate. While part of the lung collapses, other parts are over-extended.

Lung surfactant solves this second problem by reducing the surface tension as the air-epithelial fluid interface in the alveolus shrinks during expiration. Surfactant molecules are effectively insoluble in the alveolar liquids, which traps the surfactant at the interface (at least over the time scales relevant to breathing). The area available per surfactant molecule at the interface decreases along with the decrease in the alveolar interfacial area. As the interfacial density of the surfactant increases, the surfactant molecules bump into each other more and more, which induces a force opposing the surface tension of the liquid. This “surface pressure”, Π (Π = γw−γ; γw is the surface tension of a clean air-water interface, 72 mN/m, and γ the measured surface tension) exerted by the surfactant acts to expand the interfacial area in opposition to the surface tension of the liquid-air interface, which acts to decrease the interfacial area. These opposing forces cause the net interfacial tension to decrease during compression of the interface; a good lung surfactant can lower this dynamic interfacial tension to near zero. The minimum dynamic interfacial tension is limited ultimately by the strength and cohesion of the monolayer film. Eventually, the monolayer “collapses” and the film folds, buckles, deforms, cracks, etc. into either the subphase or the air [19–25] (See Fig 7). After this monolayer collapse, enough lung surfactant must remain at the interface (or re-adsorb to the interface) to respread and cover the expanding alveolar interface during inspiration to restore the equilibrium surface tension and the low dynamic surface tension during the subsequent breath.

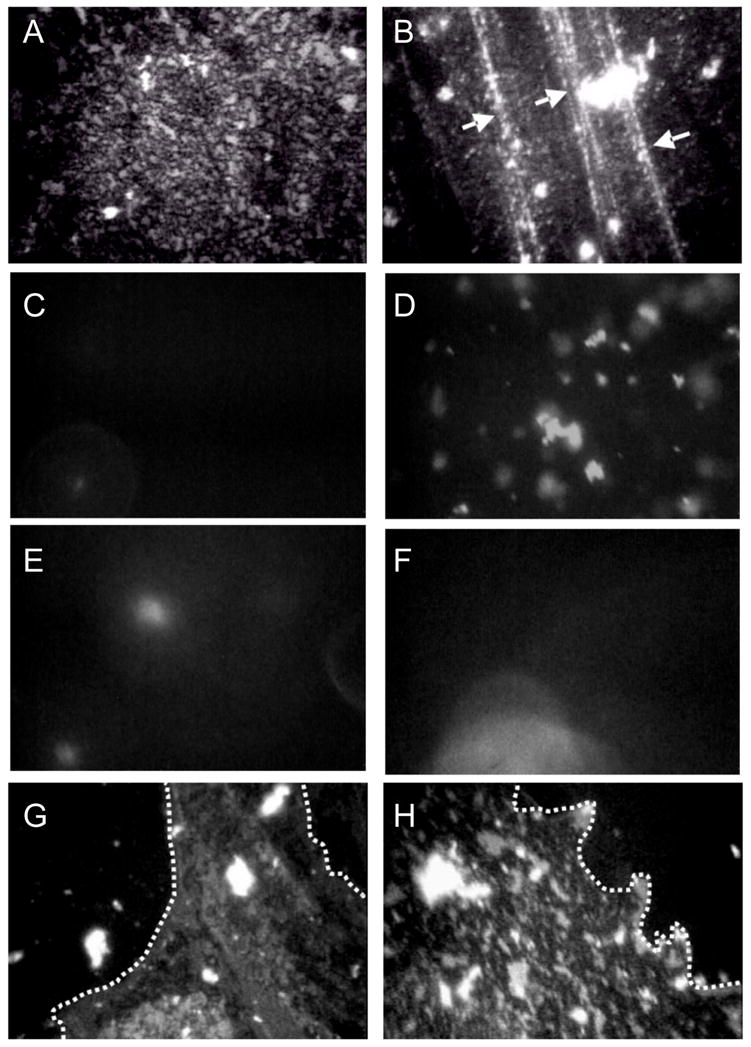

Figure 7.

Fluorescence images of 800 μg Survanta spread at varying subphase compositions. Images are 180 μm by 250 μm. The left column is for each subphase composition at Π = 18 mN/m (a, c, e, g) and the right column is for each subphase at the maximum surface pressure reached during the cycle (66,40,31,38 mN/m, respectively for b, d, f, h). Row 1-Survanta on a clean, buffered subphase. (a) shows the mottled texture typical of a phase separated lipid/protein monolayer. The mottled texture is found at all surface pressures from 0 to collapse. (b) Arrows denote cracks where material is forced from the interface at the collapse plateau at 66 mN/m.

Row 2-Survanta on buffer containing 2 mg/mL albumin. (c) At low surface pressure, no fluorescence is visible showing that the albumin prevents Survanta from adsorbing to the interface. (d) After several expansion and compression cycles (see Fig. 1b), Survanta comes close to the interface, but does not spread due to the albumin film at the interface. (Compare to e – h)

Row 3- (e) During the first cycle for Survanta spread on buffer containing 2 mg/mL albumin and 0.12% wt. PEG, small areas of the interface are starting to become covered with Survanta. (f) The Survanta monolayer begins to displace the albumin (arrow).

Row 4- (g) By the third expansion-compression cycle for Survanta spread on buffer containing 2 mg/mL albumin and 0.12% wt. PEG larger areas have a morphology similar to Survanta on a clean interface (Row 1, a,b) in coexistence with areas similar to albumin (Row 2, c, d). The dotted white lines denote the borders between the Survanta and albumin regions. 0.12 wt% PEG is not sufficient to allow for sufficient Survanta adsorption to completely displace the albumin (See Fig. 3). For ~ 1 wt% PEG, the images are identical to Row 1 for all cycles (not shown) Figure adapted from [83].

A good lung surfactant, therefore, provides both a low equilibrium surface tension and an even lower dynamic interfacial tension which minimizes the work of breathing, stabilizes alveoli against atelectasis during expiration, prevents excess liquid from accumulating in the lung, and insures uniform inflation on inspiration [2–6, 8, 9, 18]. Every air-breathing mammal has some form of lung surfactant, often very similar in composition to human lung surfactant [17, 26–29]. This is why replacement surfactants for diseases associated with surfactant deficiency or inhibition are harvested from cows (Survanta), calves (Infasurf) and pigs (Curosurf), the most common large mammals raised for food in the US and Europe.

Although essential to breathing, lung surfactant [2, 30–33] and its importance in the development of neonatal respiratory distress syndrome (NRDS; known as hyaline membrane disease at that time) [8, 34] was only begun to be appreciated in the late 1950’s. In NRDS, the lack of functional surfactant results in a progressive failure of the lungs, which is manifested clinically by atelectasis (alveolar collapse), decreased lung compliance (stiff lungs that require a greater pressure differential to inflate), decreased functional residual capacity (a measure of the amount of air left in the lungs after exhalation), systemic hypoxia (oxygen starvation), and lung edema (accumulation of fluid in the lungs) [2–4, 8, 30–32, 34, 35]. Only since the 1980’s have infants with NRDS been treated with replacement surfactants, which has significantly reduced neonatal mortality [9, 36]. Surfactant-deficient infants typically have less than 5 mg/kg of LS in their lungs, while typical healthy newborns have approximately 100 mg/kg. In 2002, RDS affected an estimated 24,000 newborns in the US [9]. Surfactant replacement is an expensive therapy; but it is cost-effective relative to neonatal intensive care [37] and has contributed to a decline in the infant mortality rate in the US.

The first clinically approved replacement lung surfactant, Exosurf, was a synthetic mixture of dipalmitoylphosphatidylcholine (DPPC, the major lipid component of native LS), hexadecanol, and the non-ionic surfactant, tyloxapol. Although efficacious, Exosurf does not contain the lung surfactant specific proteins SP-B and SP-C or any synthetic replacement peptide or protein [2]. Survanta, Curosurf and Infasurf, currently the three most-used clinical surfactants in the US, are organic solvent extracts from minced cow (Survanta) or pig (Curosurf) lungs, or extracted with organic solvents from the aqueous lavage of calf lung (Infasurf) [3, 4]. The compositions of all four clinically approved surfactants vary widely in lipid composition; there still is no generally accepted lipid composition for a replacement surfactant, although DPPC is the major lipid species of all of the replacement surfactants.

As yet, there is no clinical surfactant replacement that is as effective as whole, native lung surfactant collected directly from lavage. Whole surfactant from lavage cannot be used in human therapy due the potential for contamination by water-soluble non-surfactant proteins or infectious agents. In addition, the hydrophilic surfactant proteins SP-A and SP-D can be highly immunogenic. While the lung surfactant specific proteins SP-B and SP-C are essential to surfactant function, none of the animal extract surfactants contains even half the levels of SP-B and SP-C as native surfactant due to losses during organic solvent extraction and purification [28]. Although there is no clinical surfactant that contains SP-A, this hydrophilic protein makes up the largest fraction of LS protein, and is believed to be important to LS adsorption as well as to lung host-defense. SP-A is hydrophilic, so it cannot be harvested by organic extraction.

One goal of research in LS is to develop an entirely synthetic replacement surfactant that should reduce costs of NRDS treatment, improve uniformity, and decrease the likelihood of contamination with infectious agents [4, 9]. However, as the myriad functions and properties of lung surfactant are still being discovered and the relationship between lung surfactant composition and function is only slowly being revealed, there is likely a great deal of room for improvement and new lung surfactant formulations are in the pipeline.

Surfactant Inactivation

In certain cases, meconium aspiration syndrome being an example, neonatal replacement surfactant therapy is less effective because surfactant somehow loses the ability to reduce surface tension and is said to be “inactivated” [3, 9, 13, 38–42]. Surfactant inactivation is a qualitative term for the inability of nominally sufficient amounts of surfactant to lower surface tension to levels necessary for lung function [3, 9]. Surfactant inactivation likely contributes to the severity of acute lung injury (ALI) and acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) in both children and adults. ARDS, the more acute form of ALI, [43] was first described in 1967 and shares many symptoms with NRDS, although ARDS occurs as a rapid onset of respiratory failure that can affect patients regardless of age [9, 44–47]. ARDS has an incidence of 150,000 cases per year (U.S.) and a mortality rate of 30–40% [48–50]. The pathophysiology of ARDS involves injury to the alveolar-capillary barrier, lung inflammation, atelectasis, surfactant dysfunction, and intrapulmonary shunting. The disorder typically appears within 12 to 24 hours of an identifiable clinical event such as gastric content aspiration, pneumonia, near-drowning, toxic gas inhalation, or chest/lung trauma. In addition, ARDS may be associated with systemic processes such as sepsis, non-thoracic trauma, acute pancreatitis, major surgery, multiple blood transfusions, fat embolism, or shock. No specific therapy for ARDS currently exists.

While ARDS has a more complicated pathology than the simple absence of surfactant responsible for NRDS, ARDS shares many NRDS symptoms such as diminished lung compliance, marked restriction of functional lung volume, and hypoxemia. Hence, it was hoped ARDS might respond favorably to surfactant replacement therapy. So far, results have been mixed. Early clinical trials with the most effective formulations used in NRDS provided modest and transient improvement in adult ARDS patients [3, 44, 47, 48, 50, 51], suggesting that ARDS involves not only a lack of functional surfactant, but a mechanism of inactivation that renders both endogenous and exogenous surfactant ineffective. However, recent trials conducted with pediatric acute lung injury patients have shown significant and positive impacts on mortality after treatment with large doses of exogenous surfactant, especially those containing SP-B and SP-C [52–55].

There are many ways surfactant can be inactivated at various points in the surfactant life cycle; from transcription and protein translation, during multivesicular and lamellar body formation in the type II cell [14–16, 56], secretion into the alveolar liquid layer (subphase) from the type II cells, transformation from lamellar bodies to tubular myelin to membrane vesicles [3], re-uptake by type II cells or macrophages, losses due to transport out of the alveoli to the airways [3], or chemical degradation [9, 41, 57–59]. However, most of these mechanisms should respond favorably to surfactant replacement therapy [41]. Other abnormalities include modification of the phospholipid composition of LS, with decreased relative amounts of phosphatidylcholine and phosphatidylglycerol and an increase in cholesterol [60–62]. These biochemical abnormalities correlate with the severity of respiratory failure [35]. One reason is that increased cholesterol levels increase the minimum surface tension on monolayer compression [60, 61, 63, 64]. Lipase [65] or oxidative [57, 58, 66] damage to lipids or SP-B or C [58, 67] may also contribute to inhibition. These forms of inactivation are often slow to develop and are permanent, and could also result in degradation of exogenous surfactant over time.

However, in ARDS and ALI, inactivation is rapid. Understanding how this inactivation occurs might explain why exogenous surfactant does not have the dramatic effect in treating adult lung injuries that are seen in treating premature infants with surfactant deficiency [9, 13, 44–46, 49, 68–74]. In vivo, rapid surfactant inactivation in ARDS patients often correlates with the presence of a variety of water-soluble and surface-active substances normally absent from the alveoli [3, 44, 68, 72, 75, 76] including serum proteins, bile salts, lysolipids, and other contaminants [46, 68–70]. For example, reports of the average albumin concentrations in the alveolar fluid of ARDS patients and healthy patients vary widely, but consistently suggest an increase during ARDS: from 0.5 mg/mL for ARDS patients compared to 0.03 mg/mL for healthy patients in one reference [72] to 25 mg/mL for ARDS patients compared to 5 mg/mL for healthy patients in another report [76]. Protein concentration in the alveolar fluids of ARDS patients has been shown to correlate with the severity of the disease [77]. Da Silva et al. [62] have shown that serum proteins leaking into a ventilated rat lung led to significant decreases in surfactant performance and lung compliance; the effects on the surfactant were less when the lung was flushed to remove blood and reduce cholesterol. In vitro, there is an ARDS-like depression of LS activity when serum proteins are added to a LS-covered interface [68–70, 74, 78], LS is added to a serum-covered interface [13, 79–84] or both LS and serum proteins are presented simultaneously [85–87].

A common feature of these inhibitors of LS activity is a competing surface-activity; serum proteins, lysolipids, bile salts, etc. also spontaneously adsorb to the air-water interface and lower the surface tension. Surfactant inactivation is known to be strongly dependent on both the species and concentration of inhibitor [13, 42, 68, 88, 89], as is the surface activity. Unlike lung surfactants, which are insoluble in saline, these inhibitors can exist both at the interface and in solution; as a result, the surface tension does not drop appreciably on compression of the interface [74, 90, 91]. Serum proteins, lysolipids and bile salts have a surface pressure that is a logarithmic function of concentration up to a saturation concentration, i.e. they form Gibbs-type monolayers in many ways similar to simple detergents such as sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) [74, 91].

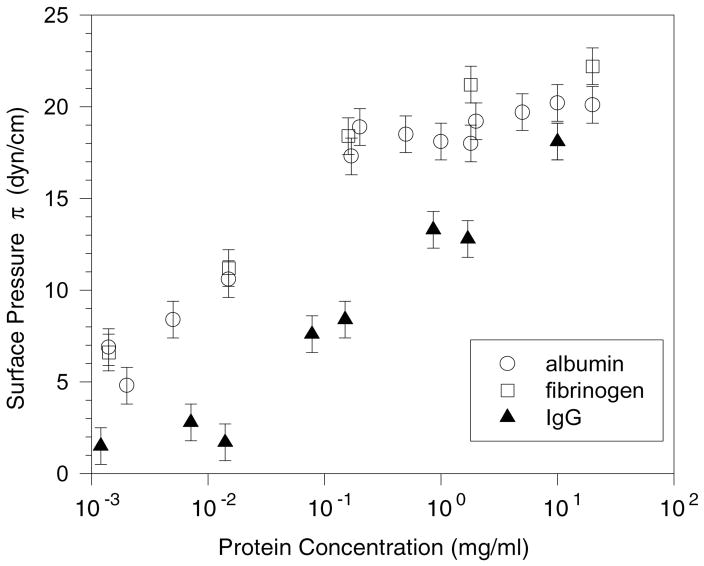

In Figure 1, the surface pressures of fibrinogen, albumin and IgG, three serum proteins commonly implicated in surfactant inhibition, are given as a function of concentration. Regardless of the protein or the concentration beyond saturation, the surface pressure does not increase to more than ~ 25 mN/m for any serum protein at equilibrium [91]. From Figure 1, albumin and fibrinogen reach the saturation surface pressure at concentrations ~ .1 mg/ml, while IgG requires 100 times that concentration to reach saturation. This concentration dependence of surface activity correlates with earlier work [92] establishing the relative inhibitory capacity of serum proteins. In Seeger et al. [92], albumin and fibrinogen were shown to be potent inhibitors requiring concentrations of just .1 and .01 mg/ml respectively, while IgG had little effect even at 1 mg/ml. This relationship between inhibitory power and surface activity appears to hold for non-protein inhibitors as well. For lysopalmitoylphosphatidylcholine, the surface pressure at the surface saturation concentration of .004 mg/ml is 34 mN/m. Holm et al. showed that lysophosphatidylcholine is a more potent inhibitor than albumin [70, 88]. Cockshutt has shown that lysolipids increase the sensitivity of lung surfactants to inhibition by serum proteins, even at very low concentrations [93], consistent with the higher surface activity of the lysolipids.

Figure 1.

Surface pressure π vs. protein concentration for bovine albumin, fibrinogen and IgG at 25 ± 1 C in buffered saline; this behavior is consistent with the serum proteins forming Gibbs-type monolayers. Fibrinogen and albumin exert a higher surface pressure than IgG at all concentrations measured. Fibrinogen and albumin reach their saturation concentrations at ~ .1 – 1.0 mg/ml, while the IgG concentration at saturation is ~ 10 mg/ml. The lower the concentration required to reach the saturation concentration, the more surface-active is the molecule and the greater is its ability to inactivate lung surfactant. However, the saturation surface pressure, Πsat, never goes much beyond 20 – 25 mN/m for all surface active serum proteins [91] and the surface pressure does not increase significantly on compression of the interface [74].

Equilibrium vs Kinetic Effects

The equilibrium surface pressure, Πeq, is the negative derivative of the Gibbs free energy, G, with respect to the interfacial area, A: [10]; therefore, the higher the equilibrium surface pressure of a given surface-active species, the more thermodynamically stable it is at the interface, and the more likely this species will occupy the interface relative to another of lower equilibrium surface pressure. For LS, Πeq (~ 40 mN/m [13]) is much higher than that of serum proteins (Πeq ~ 20 mN/m [74, 91]) or lysolecithins (Πeq ~ 30 mN/m). Therefore, LS should always be the dominant species at the air-water interface under equilibrium conditions.

However, in the expanding and contracting lung, it is doubtful if interfacial equilibrium is ever established; hence, kinetics plays the dominant role in determining which species adsorbs to the air-water interface. In vivo, LS likely never adsorbs to a pristine air-saline interface, even though this is how almost all in vitro experiments with LS begin. It is inevitable that other surface-active species (in addition to LS) compete for the interface, or must be displaced from the interface if present. New interface is created continuously during the expansion of the alveoli that accompanies inspiration, interface that must be coated with surfactant for proper breathing. Hence, if surfactant adsorption and/or spreading are slow relative to inhibitor adsorption, surfactant may not reach the interface in the concentrations needed to properly reduce surface tension, and “inactivation” is a possible result [74].

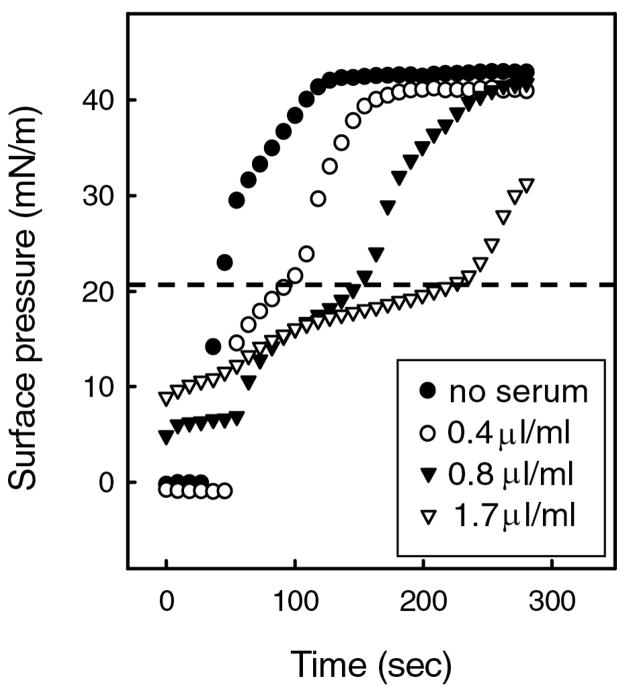

For example, [9, 13, 41, 42, 68, 70, 74, 79–85, 94–96] serum proteins can slow or even prevent LS from reaching the interface and lowering surface tension. Figure 2 shows that the time necessary for the clinical surfactant Curosurf to reach its equilibrium surface pressure, Πeq of ~ 42 mN/m, dramatically increases with increasing concentrations of human serum in the subphase. What is curious is that the rate of increase in Π is slowed only for surface pressures below the serum Πeq of ~ 20 mN/m and the slowing is proportional to the serum concentration. However once the serum equilibrium surface pressure was exceeded, further increases in Π up to the equilibrium surface pressure of LS were similar to that of the serum-free interfaces, and independent of serum concentration [13]. Πeq of the LS (~ 42 mN/m) was also independent of the serum concentration, suggesting that the composition of the adsorbed LS film was independent of the serum presence or concentration [13]. The shape of the adsorption curves suggest that as the surfactant adsorbs, it first concentrates the serum proteins in discrete domains at the interface so that the surface pressure increases to the serum Πeq as the adsorbing LS restricts the interface area available for the proteins. This co-adsorption is consistent with fluorescence images (Fig. 7) and X-ray diffraction (Figs. 8,10) [79, 80, 82–84, 97] that shows albumin and LS coexist at an air-water interface. As surfactant adsorption increases, the serum proteins must be displaced from the interface; as the surface pressure increases above the serum Πeq, the serum proteins are displaced from the interface and return to the subphase [13, 79, 80, 82–84, 97]. At higher serum concentrations in the subphase, the interfacial density of serum is also higher, and surfactant must displace more protein to adsorb and raise the surface pressure. Once the serum proteins are substantially removed from the interface by the spreading LS, additional LS appears to adsorb more readily to a LS-covered interface than to a serum protein-covered interface.

Figure 2.

Fixed amounts of the clinical lung surfactant Curosurf deposited within a buffered subphase (24°C) containing increasing concentrations of human serum. ● no serum; ○ 0.4 μl serum/mL buffer; ▼; 0.8μl serum/mL buffer; ▽ 1.7 μl serum/mL buffer. The rate of increase in surface pressure after addition of Curosurf decreased below ~ 20 mN/m (dotted line), and was proportional to the serum concentration. Above ~ 20 mN/m, the rate of increase in surface pressure was similar to that of the serum-free surfaces. The critical surface pressure at which the rates change is roughly equal to the equilibrium surface pressure, Πeq, of a subphase containing serum, ~ 20 mN/m (see Figure 1) [74, 91] The data suggests that as the surfactant adsorbs, the surfactant compresses the serum components at the interface up to Πeq, at which the serum components are squeezed-out from the interface back into the subphase. At higher serum concentrations in the subphase, more serum is adsorbed to the interface (Fig.1) and it takes longer for surfactant to adsorb and raise the surface pressure to Πsat. This decrease in the rate of adsorption with serum proteins can cause insufficient surfactant to adsorb to the interface in the time available during respiration Figure adapted from [13].

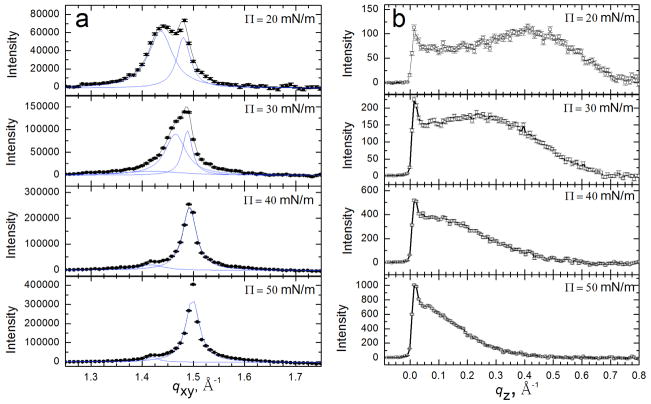

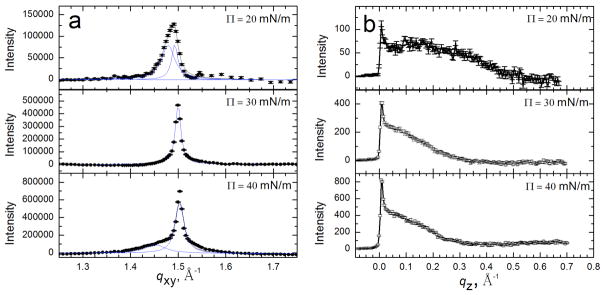

Figure 8.

Bragg peaks (a) and Bragg rods (b) from GIXD scans of 200 μg Survanta spread onto a saline buffer subphase. (a) Bragg peaks at 20–50 mN/m. The points indicate instrument data, the black curve is the overall fit and the blue curves are fits of the individual peaks. The packing changes from distorted hexagonal to hexagonal at 40 mN/m (see schematic in Table 1). A second unknown phase is visible at 1.42 Å−1 at higher surface pressures. (b) Bragg rods at 20–50 mN/m. The local maximum of the Bragg rod profile shifts left with increasing surface pressure indicating a reduction in tilt of the molecules relative to the normal; the molecules are normal to the interface for Π ≥ 40 mN/m as indicated by the lack of a local maximum for z > 0. The lattice spacings and details of the molecular ordering are given in Table 1. Figure adapted from [97].

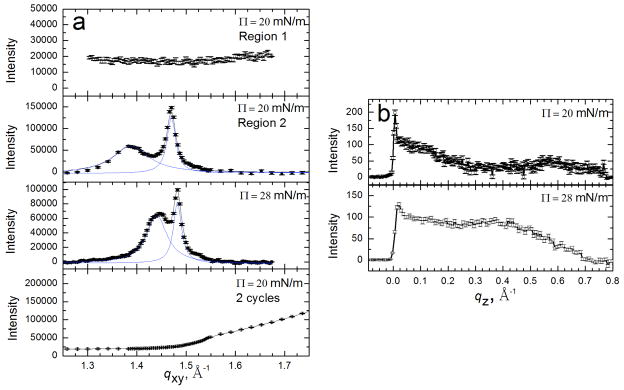

Figure 10.

Bragg peaks (a) and Bragg rods (b) from GIXD scans of 600 μg Survanta spread onto a saline buffer subphase containing 2 mg/mL albumin. (a) Bragg Peaks at 20–30 mN/m. The points indicate the diffraction data, the black curve is the overall fit and the blue curves are fits of the individual peaks. The first two panels show different regions of the film at the same surface pressure. Surface pressures higher than 28 mN/m cannot be sustained due to the presence of albumin. The distorted hexagonal lattice is slightly shifted compared to Survanta on a saline buffered subphase (See Table 1 for details). The last panel shows a GIXD scan at 20 mN/m after two additional cycles; the Survanta peaks are no longer present. (b) Bragg rods at 20–28 mN/m for scans containing Survanta peaks. At each surface pressure, a local maximum occurs for z > 0 and at a given surface pressure the molecular tilt is somewhat greater than on the control subphase Figure adapted from [97].

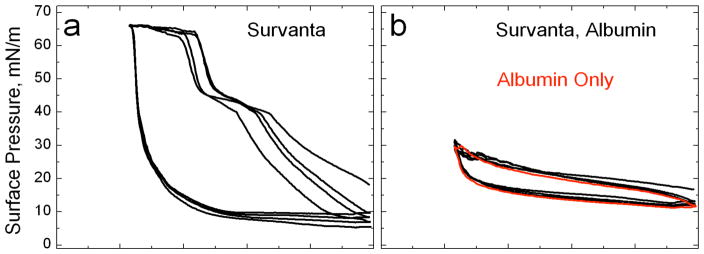

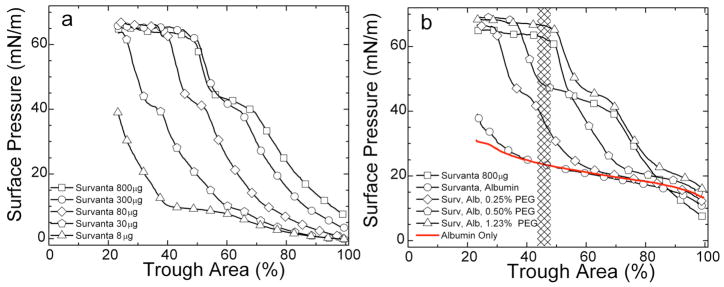

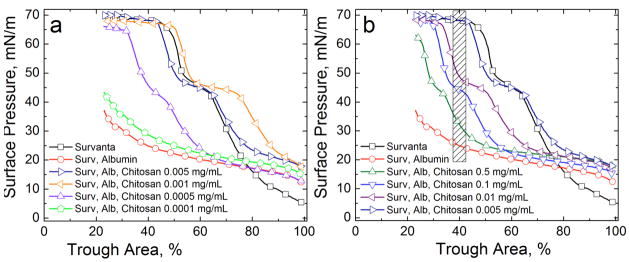

If the subphase concentration of protein is high enough, LS added to the subphase never reaches the interface and the surface pressure remains near the Πeq of albumin (Fig. 3). The expansion and compression isotherms of Survanta on an albumin-containing subphase (Fig. 3b) do not show the characteristic features of Survanta on a saline buffer (Fig. 3a); the isotherms are nearly identical to that of albumin alone, showing that significant amounts of Survanta have not reached the interface (See Fig. 7). There is a small amount of hysteresis in the isotherm of albumin suggesting that the albumin changes its conformation, orientation or packing at the interface and is less able to return to the saline subphase after compression [98].

Figure 3.

(a) Normal isotherms of Survanta, a clinical lung surfactant, on a buffered saline subphase. (b) Survanta on a 2 mg/ml albumin subphase. The Survanta plus albumin isotherm is indistinguishable from the albumin only isotherm (red). Only albumin is adsorbed to the interface under these conditions.

LS Bilayer Organization and Interactions in Solution

Both endogenous and exogenous surfactants are inactivated in ALI and ARDS; hence it is possible that serum proteins mix with or otherwise alter LS bilayers in solution, thereby altering the properties of the surfactant. Previous researchers have speculated that there might be a relationship between inhibition and surfactant microstructure [99–101] based on transmission electron microscopy of chemically fixed clinical lung surfactants. However, clinical surfactants are ~98% lipid, and lipid aggregates are notoriously difficult to fix via the conventional chemical techniques of glutaraldehyde-osmium tetroxide fixation and ethanol dehydration [14–16, 56, 102]. In comparison, rapid freezing methods [103] provide more artifact-free images of lipid bilayer samples in their hydrated state with no added chemical fixatives, while preserving both the distribution of the aggregates in the original dispersion and the microstructure and bilayer organization of the aggregates [87, 103–122].

LS contains disaturated dipalmitoylphosphatidylcholine (DPPC), unsaturated phospholipids, and the two hydrophobic LS specific proteins SP-B and SP-C [28], all of which are effectively insoluble in physiological saline. As a result, the fundamental building blocks of LS self-assembly in solution are bilayers; these bilayers further organize into more complex multilamellar liposome-like aggregates 1 – 100 microns in diameter [87, 103] (Figure 4). Although the basic structural unit is the bilayer, the bilayers within the clinical surfactants are organized in quite different ways, likely due to the differences in lipid composition, especially the fraction of saturated vs unsaturated lipids, as well as the fraction of charged lipids and cholesterol. Survanta forms the largest aggregates with the smallest bilayer spacing, consistent with a highly ordered, likely gel phase bilayer due to its high fractions of DPPC and palmitic acid [123, 124, 125.]. Infasurf, with the smallest fraction of saturated lipids, forms very open, multicompartment structures with a large amount of water contained within the aggregate, indicative of highly fluid and fluctuating bilayers. Curosurf, with intermediate saturated lipid fractions, forms aggregates that are intermediate between the structures of Survanta and Curosurf (Fig. 4).

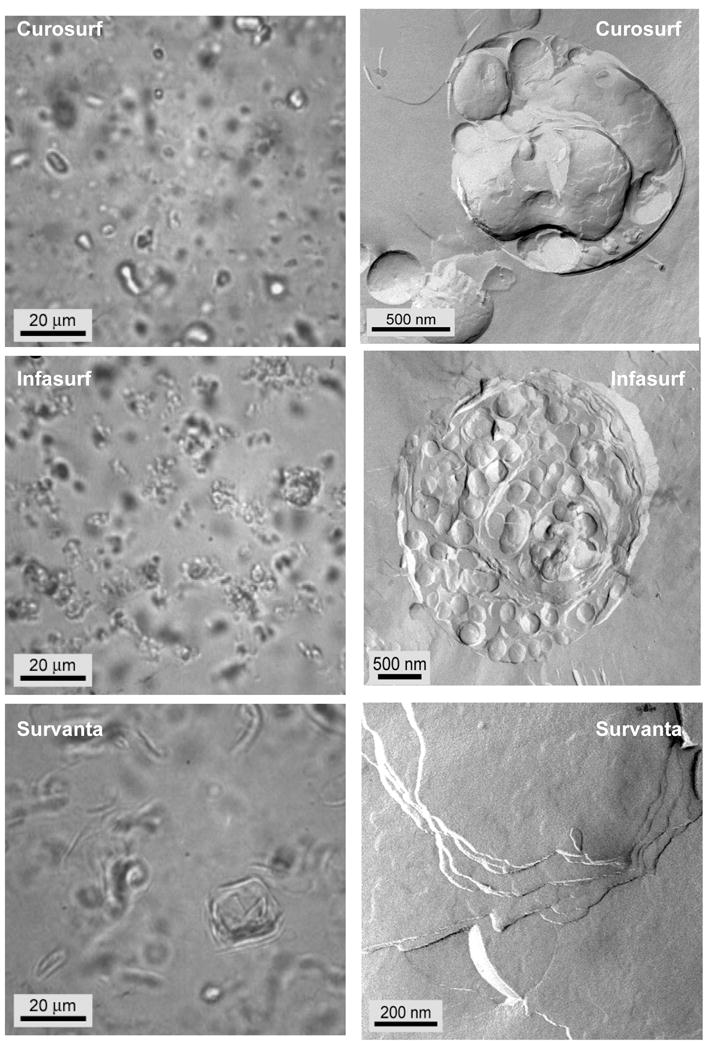

Figure 4. Optical phase contrast (left column) and freeze-fracture electron (right column) microscopy images of Curosurf (A, B), Infasurf (C, D) and Survanta (E, F).

A, C, E: The optical images show that all of the clinical surfactants consist of dispersed, small aggregates, with Survanta being the largest.

B. Individual Curosurf aggregates are multilamellar and typically had some void space between bilayers and “pockets” of water within the aggregate. This is consistent with the small angle X-ray scattering that showed broad reflections indicative of poor correlations between the bilayers.

D. Infasurf aggregates had a multicompartment bilayer structure with densely packed interior vesicles and large water pockets. The structures are similar to vesosomes, a vesicle in vesicle drug delivery vehicle [115–117, 216].

F. Survanta aggregates were typically too large to be imaged as individual particles in TEM. Here we show the multilamellar stacks of well-ordered bilayers within the larger aggregates. There are no water pockets within the Survanta particles. The degree of organization of the aggregates scaled with the fraction of saturated phospholipids and fatty acids, with Survanta being the most ordered and having the most saturated lipids, and Infasurf having the least ordered aggregates, with the highest unsaturated lipid and cholesterol fraction (Figure adapted from [87]).

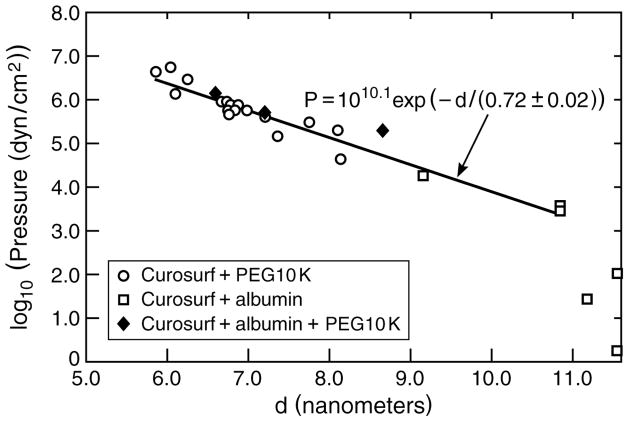

The bilayer-bilayer interactions that determine the equilibrium bilayer d-spacing (or bilayer repeat spacing, which is a combination of the bilayer thickness plus any water between the bilayers) are a balance of van der Waals attraction [79, 126–128] and a combination of the Helfrich undulation repulsion [126, 127, 129–132] and electrostatic double-layer repulsion [87, 120, 121] (Eqn. 14). Small angle X-ray scattering shows that when 10 kDa polyethylene glycol polymer is added to Curosurf, the bilayer d-spacing decreases as shown in Fig. 5. The same thing happens when sufficient albumin is added to the Curosurf suspension. This reduction in the d-spacing implies that macromolecules such as 10 kDa PEG or albumin cannot enter the aqueous spaces between the surfactant bilayers or incorporate within the bilayers themselves [133–135]. This exclusion of the PEG or albumin generates a concentration difference between the inside and outside of the bilayer shells that make up the aggregate, which in turn, generates an osmotic pressure difference that causes the water between the bilayers of the aggregate to be expelled, and the bilayer d-spacing to decrease so as to equalize the pressure between the bilayers with the applied external osmotic pressure.

Figure 5.

Bilayer d-spacing measured by small angle X-ray scattering from dispersions of Curosurf, Curosurf plus albumin and Curosurf plus albumin and 10 KDa PEG polymer as a function of the osmotic pressure of polymer or polymer plus albumin. For osmotic pressures greater than 103 dynes/cm2, the d-spacing decreases exponentially with increasing osmotic pressure with a decay length of 0.72 nm, which is nearly identical to the calculated Debye length of the solvent, κ−1 = 0.77 nm, confirming that the bilayers interaction is dominated by the electrostatic double-layer repulsion [133, 134]. For comparison to Figs. 4, 6, the osmotic pressure of 2 wt% albumin is < 103 dynes/cm2 and the osmotic pressure of 5 wt% 10 kDa PEG is ~ 106 dynes/cm2. The albumin and polymer act primarily as osmotic agents that dehydrate the bilayers, confirming that albumin and polymer do not adsorb to or penetrate the surfactant aggregates. Figure adapted from [87].

With no albumin or polymers in the solution, Curosurf has a bilayer d-spacing of about 11 nm, which decreases to about 6 nm at the highest PEG and/or albumin concentration, and hence, applied osmotic pressure. As the bilayers come closer together, the inter-bilayer repulsion increases, thereby increasing the internal pressure between the bilayers. The functional form and characteristic decay length of the interbilayer pressure is determined by the origin of the interactions between the bilayers. If the electrostatic double-layer repulsion (See 2nd term in Eqn. 14) dominates the bilayer-bilayer interaction [133–135], the relationship between d-spacing and applied pressure is exponential:

| (1) |

| (2) |

with a characteristic decay length given by κ−1, the Debye length (T is the absolute temperature, kB is Boltzmann’s constant, 1.38054 × 10−23 N-m/K, zi is the valence of ionic species i, e is the electron charge, 1.6021 × 10−19 C, ε0 is the permittivity of the vacuum, 8.854 × 10−12 C2/N-m2, and ε is the dielectric constant of the solution, about 80 for water [136]. In practical units, for an aqueous buffer at 25° C [128]. For the buffered, physiological (150 mM NaCl, 2 mM CaCl2) saline used, the ionic strength, moles/liter, which gives κ1 ~ .77 nm (ρi is the molar concentration of each ion and zi is the charge on that ion [128].) Any additional counterions from the anionic lipids in the surfactant (or albumin) increase the ionic strength and further reduce κ−1. Fig. 5 shows that the bilayer d-spacing for Curosurf is an exponential function of the osmotic pressure with a characteristic decay length of 0.72 ± .02 nm, which is in excellent agreement with the calculated Debye length. This behavior is typical for fluid bilayers with a significant fraction of charged lipids stabilized by double-layer repulsion [133–135]. Zeta-potentials of −10 to −15 millivolts have been measured for other LS aggregates, which are also consistent with electrostatic double-layer interactions [137].

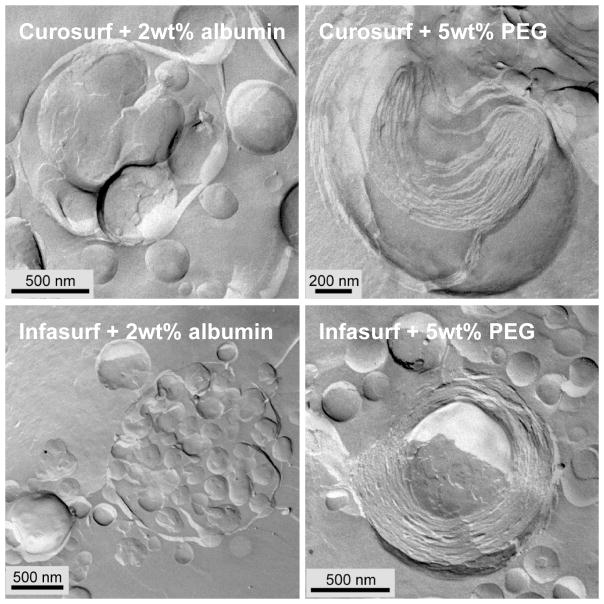

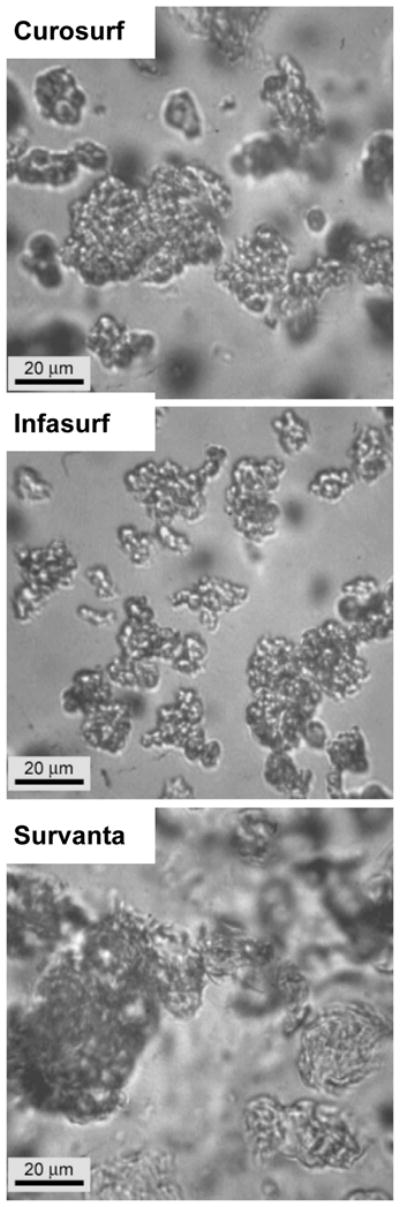

Figure 6 shows freeze-fracture TEM images of Curosurf and Infasurf aggregates in a buffer solution containing 2 wt% albumin (left) or 5 wt% 10 kDa PEG (right). 2 wt% albumin is more than sufficient to prevent LS adsorption, (Figs. 2,3,7) but does not alter the bilayer organization within LS aggregates (compare to Fig. 4). Individual albumin molecules adsorbed to or incorporated within the bilayers would appear as 5 – 10 nm high bumps or pits on the bilayer surfaces in freeze-fracture images [109]. However, the bilayers remain as smooth as when there is no albumin in solution. This is consistent with the SAXS data in Fig. 5 that shows that the primary effect of albumin in the bulk (even at much higher concentrations) is as an osmotic agent that does not penetrate the aggregate. The osmotic pressure of a 2 mg/ml albumin solution is ~ 103 dynes/cm2, which is not sufficient to alter the spacing of the Curosurf bilayers (See Fig. 5). While Infasurf, Curosurf and Survanta have quite different compositions and microstructures, albumin does not adsorb to or alter the lamellar organization of any of the clinical surfactants at concentrations at which surfactant adsorption is inhibited.

Figure 6.

Freeze-fracture TEM images of Curosurf (top row) and Infasurf (bottom row) aggregates in a buffer containing 2 wt% albumin (left) or 5 wt% 10 kDa PEG (right). 2 wt% albumin does not appreciably alter the aggregate morphology (compare to Fig. 4), while it is more than sufficient to prevent LS adsorption. 5 wt% 10 kDa PEG causes the bilayer spacing in both Curosurf and Infasurf aggregates to decrease (see Fig. 5) and eliminates the water-filled void spaces within the aggregates. The bilayers were more ordered after exposure to PEG (compare to Fig. 4). For Infasurf in 5 wt% 10 kDa PEG, instead of the vesicle within vesicle structure common when there was no PEG (Fig. 4), the aggregates were much more compact with concentric, parallel bilayers in onion-like structures [16, 56]. Figure adapted from [87]. These changes are consistent with PEG not being capable of crossing the bilayers and acting as an osmotic dehydrating agent.

In the presence of 5 wt% 10 kDa PEG (or proportionately high albumin concentrations), while there was little change in the average aggregate size, the organization of the bilayers within the aggregates was significantly altered. The average bilayer spacing decreased (as expected from the SAXS results) and there were no longer any water-filled void spaces within the aggregates. The bilayers were more ordered after exposure to PEG (compare to Fig. 4). For Infasurf in 5 wt% 10 kDa PEG, instead of the vesicle within vesicle structure common when there was no PEG (Fig. 4), the aggregates were much more compact with concentric, parallel bilayers in onion-like structures [16, 56]. The void spaces and water pockets were removed and the interior compartments fused. However, Survanta, which consisted of compact bilayers with no void spaces even without PEG, did not show significant morphological changes caused by adding PEG at 5 wt% (not shown).

Monolayer Structure, Organization and Collapse

Alterations in the organization and structure of the monolayer might also contribute to surfactant inactivation by serum proteins, leading to lower collapse pressures, poor respreading, etc. When the surfactant aggregates shown in Figs. 4, 6 contact the air-water interface, the bilayers break down to form insoluble, Langmuir-type monolayers and multilayers (Fig. 7 and See Movie 1 in Supplementary Materials). It appears that the aggregates must contact the interface to undergo this conversion. If there is insufficient area to spread on the interface, the bilayer aggregates can partially fuse with the monolayer or multilayer film without undergoing complete conversion (bright white patches in Fig. 7) [83, 138]. Figure 7 shows fluorescence images of Survanta (doped with 1 mol% of the fluorescent dye, Texas Red-DHPE; Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR) films at the air-subphase interface. The mottled black and gray textures in Fig. 7a are typical of a phase separated lipid/protein monolayer (Fig. 7a; Π = 18 mN/m); the scattered, bright white patches are aggregates partially fused with the interface. The gray patches, which contain a higher fraction of the fluorescent lipid dye, are disordered, fluid lipid domains mainly populated by unsaturated and anionic lipids and LS proteins [4, 20, 22, 139–141]. The dark gray patches, on the other hand, have semi-crystalline order of the lipids molecules (See Fig. 8), which excludes the fluorescent lipid dye. This ordered phase contains most of the DPPC, palmitic acid (PA) and other saturated lipids in LS [124, 125, 138, 141, 142].

Surfactant adsorbs only up to the Πeq of 40 – 45 mN/m (Fig. 2); to provide the necessary low tensions required for breathing, as the available interfacial area is reduced in the alveolus during exhalation, or on compression of the film in a Langmuir trough (Fig. 7b), the surface pressure increases to 65–70 mN/m as the available area per molecule of LS decreases. At some point, the interfacial film can no longer support an increasing surface pressure and the film fails or “collapses” [22, 24, 25]. At collapse, the film can no longer support the imposed stresses and lung surfactant films usually fail by buckling and forming three-dimensional cracks and folds. Fig. 7b shows the cracks and folds (arrows) at monolayer collapse in Survanta, which determines the maximum surface pressure, Πmax that can be achieved by the film (Fig. 7b; Πmax = 66 mN/m, surface tension of ~ 6 mN/m) [22, 23, 138]. The collapse mechanism [22, 24, 25, 61, 138, 140, 142–154] and respreading of the monolayer film are areas of intense interest, but will not be examined in this review.

In contrast, when Survanta is deposited on a buffered subphase containing 2 mg/ml albumin, the fluorescence images are featureless (Fig. 7c) or show isolated, out of focus bright spots (Fig. 7d) indicative of Survanta aggregates in the subphase kept from reaching the interface by the adsorbed albumin film. It appears that the Survanta does not undergo significant conversion from bilayers to monolayers and cannot unravel and expand to cover the interface unless the surfactant particle comes into contact with the interface. Quantitative comparisons shows that less surfactant adsorbs to the interface from 3.8 mg of Survanta deposited on an albumin subphase than from 30 μg of Survanta deposited onto a clean subphase [83]. Albumin in the subphase is roughly equivalent to lowering the surfactant concentration by a factor of 120! From the isotherms and the fluorescence images, the interface is essentially covered by albumin with very little surfactant.

Lung Surfactant Interfacial Organization

A second possibility underlying surfactant inactivation is that serum proteins alter the monolayer organization, causing the surfactant to collapse at lower surface pressures or in some other way to lose its ability to reduce surface tension. Table 1 summarizes the intermolecular d-spacings, lattice parameters, area per chain, and coherence lengths of the ordered portion of Survanta monolayers as a function of subphase composition and surface pressure (Fig. 7a). Grazing incidence X-ray diffraction (GIXD) provides information about the laterally ordered (liquid condensed and solid phases) domains within the monolayer; disordered (liquid expanded, fluid or protein-covered) areas of the film do not diffract appreciably and are effectively invisible [155]. The number and position of the Bragg peaks (Fig. 8a) allows the determination of the symmetry and repeat distances, d = 2π/qxy, of the 2D lattice. The sharper the peak, the better ordered the crystal, which is quantified by the coherence length, Lxy, in the different lattice directions. The Bragg rods (Fig. 8b) give the molecular tilt; if a local maximum in the intensity of the Bragg rod occurs for z > 0, the molecules in the monolayer are tilted with respect to the normal to the monolayer [155, 156].

Table 1.

| Phase 1 |

||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unit Cell Angle | ||||||||||

| Subphase | Π(mN/m)1 | Packing | Observed d-spacing d10 (Å) | Observed d-spacing d1-1 (Å) | a = b (Å) | γ° | Coherence Length Lc10 (Å) | Coherence Length Lc1-1 (Å) | Area per Chain (Å2) | |

| Saline Buffer | 20 | Dist. Hex | 4.38 | 4.24 | 4.95 | 118 | 100 | 175 | 21.7 |  |

| Saline Buffer | 30 | Dist. Hex | 4.29 | 4.22 | 4.90 | 119 | 115 | 265 | 21.0 | |

| Saline Buffer | 40 | Hexagonal | 4.21 | -- | 4.86 | 120 | 177 | -- | 20.5 | |

| Saline Buffer | 50 | Hexagonal | 4.19 | -- | 4.84 | 120 | 185 | -- | 20.3 | |

| PEG | 25 | Dist. Hex | 4.36 | 4.23 | 4.94 | 118 | 129 | 225 | 21.5 | |

| PEG | 30 | Dist. Hex | 4.32 | 4.22 | 4.91 | 118 | 131 | 237 | 21.2 | |

| PEG | 40a | Hexagonal | 4.18 | -- | 4.83 | 120 | 287 | -- | 20.2 | |

| PEG | 40 | Hexagonal | 4.19 | -- | 4.83 | 120 | 200 | -- | 20.2 | |

| PEG | 50 | Hexagonal | 4.20 | -- | 4.84 | 120 | 181 | -- | 20.3 | |

| Albumin | 20 | Dist. Hex | 4.53 | 4.28 | 5.04 | 116 | 64 | 296 | 22.8 | |

| Albumin | 30 | Dist. Hex | 4.36 | 4.24 | 4.94 | 118 | 113 | 312 | 21.6 | |

| Albumin/PEG | 20 | Dist. Hex | 4.25 | 4.21 | 4.88 | 119 | 183 | 399 | 20.7 | |

| Albumin/PEG | 30 | Hexagonal | 4.19 | -- | 4.84 | 120 | 494 | -- | 20.3 | |

| Albumin/PEG | 40 | Hexagonal | 4.18 | -- | 4.83 | 120 | 280 | -- | 20.2 | |

The first row for a PEG subphase at 40 mN/m is 200 μg Survanta while the second is 600 μg

Survanta d-spacings, unit cell parameters (see inset figure), coherence length and area per chain as a function of subphase composition and surface pressure. Phase 1 is the dominant phase and transitions from a distorted hexagonal lattice (a = b, γ ≠ 120°) to a hexagonal lattice (a = b, γ = 120°) with increasing surface pressure. The approximate molecular tilt relative to the normal to the interface is given by t° = cos(20.2/Ac), in which Ac is the area per chain (20.2 A2 is the minimum area per chain for orientations normal to the interface in a hexagonal lattice).

The coherence lengths are determined from the peak full widths at half maximum height (FWHM) relative to the instrument resolution FWHMresol(qxy) = 0.0084 Å−1. The intrinsic FWHM can be obtained from: FWHMinstrinsic(qxy) = [FWHMmeas(qxy)2 − FWHMresol(qxy)2]1/2 and the Scherrer formula defines the coherence length: L ≈ 0.9[2π/FWHMintrinsic(qxy)] [215].

Fig. 8 shows the Bragg peaks (Fig. 8a) and Bragg rods (Fig. 8b) from [155] monolayers of the LS, Survanta, as a function of surface pressure [97]. At Π = 20 mN/m, two Bragg peaks are observed, with the integrated intensity of the qxy = 1.44 Å−1 or {1,0} peak, roughly twice that of the qxy = 1.48 Å−1 or {1,−1} peak, indicating a distorted hexagonal lattice similar to DPPC and DPPC/palmitic acid mixtures under similar conditions [124, 125, 138, 142]. The lattice spacings (dxy = 2π/qxy) are d10 = 4.38 Å and d1-1 = 4.24 Å, corresponding to a distorted hexagonal unit cell (see schematic diagram in Table 1) with axes a = b = 4.95 Å and γ=118° [125]. This lattice spacing leads to a calculated area per hydrocarbon chain of 21.7 Å2. At 20 mN/m, the Bragg rod profile (Fig. 8b) exhibits a local maximum at qz = 0.41 Å−1, indicating that the lipid molecules are tilted relative to the surface normal [138].

At Π = 30 mN/m, the two Bragg peaks shift to qxy = 1.47 Å−1 and qxy = 1.49 Å−1 indicating a less tilted lattice. The local maximum in the Bragg rod moves closer to zero (qz = 0.23 Å−1) confirming the reduction in lipid tilt. At 40 mN/m, the single peak at qxy = 1.49 Å−1 indicates a transition to a hexagonal lattice (a = b, α = 120°) with d10 = 4.21 Å and . The Bragg rod has a maximum at z=0, indicating that the lipid molecules are normal to the interface. Increasing the surface pressure to 50 mN/m results in only a slight right shift of the main to peak to qxy = 1.50 Å−1; the Bragg rods again indicate that the molecules are untilted. Survanta films are more compact than DPPC films; a pure DPPC film at Π = 40 mN/m shows two Bragg peaks at qxy = 1.38 Å−1 and qxy = 1.46 Å−1 indicating that the DPPC lattice is still tilted [125, 157]. The solid phase domains in Curosurf and Infasurf have similar lattice spacings as Survanta, although since the fraction of DPPC is different, the surface pressure dependence of the lattice spacing and the tilt are also different [124, 125, 138, 142].

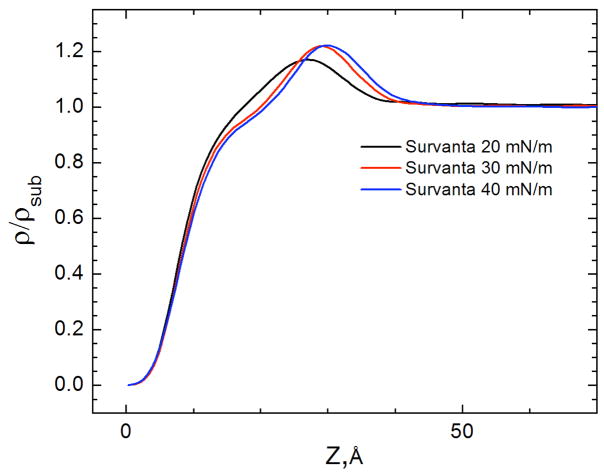

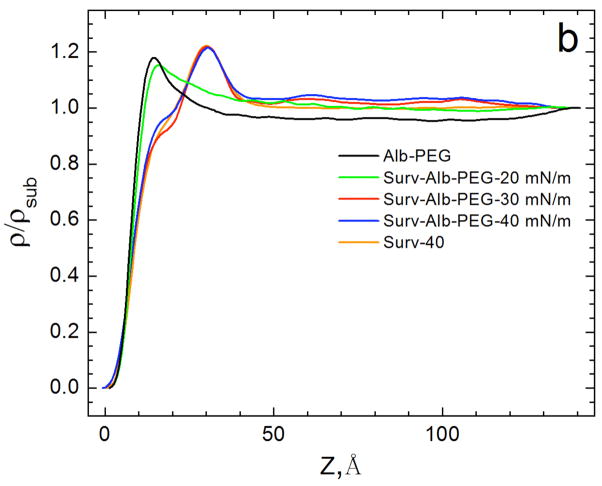

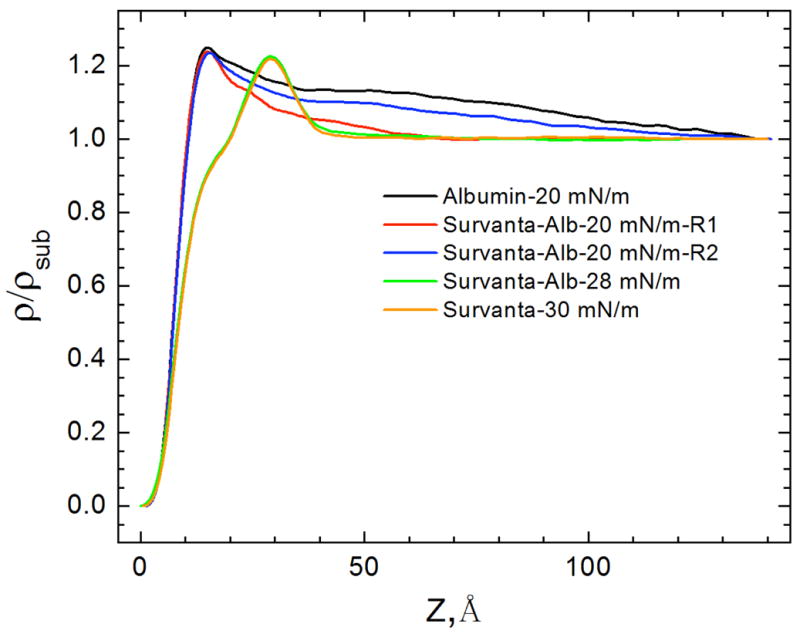

X-ray reflectivity (XR) provides the complementary laterally averaged electron density profile normal to the interface. Unlike GIXD, XR is sensitive to all materials at the interface regardless of local order. Fig. 9 shows the electron density profiles of adsorbed Survanta films, normalized by the subphase electron density (ρ(Z)/ρsub) [158–160]. For LS films, the electron density begins at 0 on the air side of the interface (Z = 0), rises sharply through the tail region, and reaches a maximum at the headgroup region at Z~30 Å before quickly decaying to the subphase electron density (ρ(Z)/ρsub = 1) at Z ~ 42 Å. The density of the headgroup maximum increases (1.17 to 1.22) and the width of the maximum decreases and shifts to the right with increasing surface pressure, indicating a reduction in the tilt of the tails, consistent with the Bragg rods in Fig. 8b [161].

Figure 9.

The electron density profiles calculated from X-ray reflectivity data normalized by the subphase electron density, for 200 μg Survanta spread on the control subphase. Increasing Z moves from the air (Z=0) through the interface and into the subphase. With increasing surface pressure, the density of the headgroup maximum increases, the width of the headgroup region decreases and the location of the headgroup maximum shifts right, consistent with the GIXD data in Fig. 8 that shows a steady decrease in the molecular tilt with increasing surface pressure Figure adapted from [97].

When Survanta is adsorbed to an interface from a subphase containing albumin, both GIXD and XR confirm that albumin and LS can coexist at the interface, consistent with the fluorescence images in Fig. 7. At Π = 20 mN/m, different areas of the interface showed dramatically different scattering patterns. Region 1 (Fig. 10a, first panel) shows no diffraction peaks, consistent with a disordered albumin film at the interface. However, Region 2 (Fig. 10a, second panel), which was obtained by simply moving the interface horizontally by several mm in the direction perpendicular to the X-ray beam, shows Bragg peaks consistent with a distorted hexagonal lattice with the {1,0} reflection at qxy = 1.39 Å−1 and the {1,−1} reflection at qxy = 1.47 Å−1. The lattice is slightly expanded compared to Survanta at 20 mN/m with a = b = 5.04 Å and γ=116°. The Bragg rods exhibit a local maximum at qz = 0.57 Å−1, indicating a greater molecular tilt than Survanta on the control subphase (Fig. 8b). While the isotherm (Fig. 3b) and fluorescence images (Fig. 7) [82–84] indicate that the albumin dominates the interface under these conditions, the appearance of diffraction peaks consistent with a distorted hexagonal lattice demonstrates that some ordered domains of Survanta have broken through to the interface. Compressing the film in the trough increased the surface pressure only to 28 mN/m (see Fig. 3b), which caused the two Survanta peaks to shift to qxy = 1.44 Å−1 and qxy = 1.48 Å−1, corresponding to a less tilted lattice. While there are subtle changes in the Survanta tilt and lattice spacing on albumin-containing subphases, the general features are unchanged [124, 125, 138, 142, 162]; it appears as if the albumin were slightly lowering the effective surface pressure. The last panel in Fig. 10 shows GIXD scans after two additional compression-expansion cycles; the Bragg peaks disappear, indicting that no ordered domains of Survanta remain at the interface; the albumin has displaced the Survanta from the interface. From the minimal changes in the lattice spacing and tilt of the Survanta, there is minimal mixing of the albumin film with the ordered fraction of the LS film at the interface.

XR electron density profiles confirm the albumin-LS coexistence at the interface. For albumin alone, the electron density at the interface increases more sharply than does Survanta (Fig. 11), reaching a maximum ρ/ρsub = 1.25 at Z = 15 Å. Other globular proteins such as β-lactoglobulin have a similar maximum electron density (ρ/ρsub = 1.20) [163]. Albumin is a prolate spheroid of dimensions 40 × 40 × 140 Å [164]. Unlike the electron density profiles for Survanta (Fig. 9), ρ/ρsub is significantly greater than 1 for 50 < Z < 100 Å. This suggests that a second layer of albumin [97] may form with the albumin long axis parallel to the interface. Both neutron reflectivity [164] and ellipsometry [165] also indicate a dense, closely packed albumin monolayer with a less dense second layer.

Figure 11.

The electron density profiles, normalized by the subphase electron density from X-ray reflectivity measurements for 600 μg Survanta spread on a saline buffer subphase containing 2 mg/mL albumin. No Survanta is present for the albumin-only subphase data. Region 1 and Region 2 are the same areas as the GIXD data in Fig. 10. For Survanta-albumin mixtures at 20 mN/m, the electron density profile is similar to albumin for both Region 1 and Region 2, while for 28 mN/m, the electron density profile is similar to Survanta (Fig. 9). Figure adapted from [97].

The electron density (Fig. 11) corresponding to Region 1 and Region 2 (defined in Fig. 10), are qualitatively similar to albumin even though GIXD showed small patches of ordered Survanta in Region 2. However, the electron density of the mixed Survanta/albumin films in both Region 1 and Region 2 decreased more quickly with increasing z than the albumin film. This suggests that Survanta has displaced the second layer of albumin (Fig. 7c,d). In contrast, the electron density of the mixed Survanta-albumin film at 28 mN/m, the highest surface pressure that could be achieved for the duration of the XR experiment, is very similar to that of Survanta on the control buffer at 30 mN/m. The GIXD curve of Survanta-albumin at 28 mN/m (Fig. 4) shows diffraction peaks, confirming that Survanta is at the interface. The ratio of Survanta to albumin at the interface apparently increases with increasing surface pressure. However, the film is still “inhibited” by albumin; the isotherms (Fig. 3) shows that the maximum surface pressure does not increase above 35 mN/m even after compression to the smallest trough area, suggesting that the Survanta never completely displaces the albumin.

At all surface pressures, 10 kDa PEG in the subphase induces minimal changes in the Survanta Bragg peaks and Bragg rods (Table 1) [97], indicating that PEG, like albumin, does not significantly modify the molecular lattice of the ordered domains of the surfactant. Additionally, Table 1 shows that at a specific surface pressure (Π = 40 mN/m) and subphase condition (5% wt. PEG), different amounts of Survanta (200 μg and 600 μg) yield nearly identical lattice parameters. This confirms that at a given surface pressure, there is a unique, fixed area per molecule [83] for a given temperature; the surface density is not a function of the subphase concentration, but only of the surface pressure and temperature.

Kinetically Hindered Equilibrium and Analogies to Colloid Stability

The equilibrium spreading pressure, collapse pressure, LS aggregate sizes and shapes in solution, the bilayer d-spacing and the monolayer lattice spacing and tilt are not affected by albumin or serum at concentrations that inactivate LS performance [97]. Hence, this mechanism of inactivation does not involve alterations to the surfactant bilayer or monolayer. However, both albumin and LS prefer to occupy the air-water interface, resulting in a competition for the available area. Because of its nanometer size, albumin diffuses much faster than multi-micron bilayer aggregates of LS (Fig. 4, 6). The Stokes-Einstein diffusivity, DSE = kBT/6πηsa, shows that an albumin molecule 2 nm in radius, a, should diffuse 1000 times faster than a surfactant aggregate of radius 2 microns in saline with a bulk viscosity ηs. Hence, albumin and the other serum proteins will almost inevitably beat LS aggregates in the race to an uncoated interface [74, 166]. In both the expanding alveolus in the lung and the Langmuir trough, new air-water interface is continuously being created for this competitive adsorption [74]. In addition to competing for this new interface, LS must displace albumin from whatever part of the interface the protein already occupies in order to lower the surface tension so that proper lung function occurs. From the isotherms (Fig. 3b), fluorescence images (Fig. 7) and X-ray (Fig. 8–11), if a significant fraction of the interface is covered by albumin or serum proteins, sufficient LS cannot adsorb to the interface to raise the surface pressure to the levels needed for proper lung function for a given compression (Π > 60 mN/m, surface tension < 10 mN/m).

Clearly, there is something about the presence of serum proteins at the interface that inhibits lung surfactant adsorption [9, 13, 42, 68–70, 74, 88, 96, 167]. To adsorb, LS must first clean an area of interface by pushing the albumin aside, which reduces the overall driving force for LS adsorption [166]. Instead of increasing the surface pressure from zero at a clean interface to the ~ 40 mN/m equilibrium spreading pressure of LS, albumin already had increased the surface pressure to ~ 20 mN/m. This change in the driving force likely leads to changes in the desorption of albumin and the adsorption-desorption equilibrium for LS [166].

However, from the fluorescence images and isotherms, LS often does not even reach the interface. The isoelectric point of albumin is 5.2, and hence albumin, like LS, is negatively charged at physiological pH, which can induce an electrostatic energy barrier to adsorption [80, 96], preventing LS from reaching the interface and converting from bilayers to a surface-active film [42]. This energy barrier to LS adsorption is reminiscent of the energy barriers that stabilize colloidal dispersions and prevents them from coagulating [9, 13, 42, 80, 83, 84, 95, 96]. Colloidal dispersions should coagulate at equilibrium due to strong, short range interactions, yet they remain stable for years and even decades [79, 128, 136, 168, 169].

The stabilization of colloidal dispersions by proteins, including albumin, was first exploited for the preparation of ink in ancient Egypt and China as early as 2500 BC [170]. By mixing the soot from lamps with a solution of proteins (casein from milk, egg albumin, or gum Arabic), the ink could be dried and stored. When fluid ink was needed, the dried ink was dipped into water, and the soot particles coated by the proteins spontaneously re-dispersed and the ink was ready for use. Fast re-dispersion is a characteristic of colloids that are stabilized by proteins and other biopolymers [170].

The famous British chemical physicist, Michael Faraday, reported the first scientific study of the effects of albumin and other proteins on colloid stability in 1857 [171, 172]. In the absence of protein, a gold sol could be induced to aggregate by the addition of sodium chloride; aggregation was not observed when protein was present. Some of Faraday’s original gold colloids remain dispersed for over 100 years [172]. Richard A. Zsigmondy, who won the Nobel Prize in Chemistry in 1925, quantified the relative effects of different biopolymers in preventing the coagulation of a gold sol by a fixed concentration of sodium chloride, which he termed the “gold number” [173]. The gold number of a protein was defined as the amount in milligrams of protein which, when added to 10 ml of a gold sol, just prevents coagulation on the addition of 1 ml of a 10% salt (NaCl) solution. For gelatin, the gold number was ~ 0.01; for albumin, ~ 0.1, showing that albumin and other soluble, surface-active proteins were quite effective at stabilizing a gold sol against coagulation [170]. However, quantifying and predicting the stabilizing effects of albumin and the de-stabilizing effects of electrolytes on colloids required another 80 years of research.

The first step toward understanding the mechanisms behind colloid stability was the derivation by Smoluchowski (1917) of diffusion-limited coagulation [174], which Fuchs (1934) extended to show that the coagulation rate slowed in the presence of an repulsive inter-particle potential, Φ [175]. The flux/area, −J = dΓ/dt, (Γ is the interfacial concentration in molecules/unit area) to an interface located at x=0, is proportional to a friction factor, DSE/kBT, which is in turn proportional to the diffusivity of the colloidal particles, DSE, (here the lung surfactant aggregates, Figs. 4, 6). The driving force, in general, is the product of the local bilayer aggregate concentration, C, and the gradient in chemical potential ∇μ:

| (3) |

The normal chemical potential is altered by the inter-particle potential, Φ(x):

| (4) |

Combining Eqns. 3, 4 leads to a generalized diffusion equation:

| (5) |

The first term on the right side of Eqn. 5 is the normal diffusive flux, which is usually called Fick’s First Law of Diffusion [176]. The second term in Eqn. 5 is the retarding effect of the potential gradient between the particles. At steady state, the flux/area, J, in Eqn. 5 is constant, and Eqn. 5 can be simplified by multiplying both sides by exp(Φ/kBT):

| (6) |

and integrated as follows:

| (7) |

The limits of integration are such that the LS aggregate concentration is zero anytime a surfactant aggregate gets to the interface at x=0, (the surfactant aggregate converts to monolayer form, making C=0 at x =0), and the concentration reaches the bulk surfactant solution concentration, C = CB, and the potential, Φ → 0, as x → ∞. This gives:

| (8) |

The right hand side of Eqn. 8 is approximated by noting that the integral is dominated by the value of Φ at its maximum, Φmax, and the potential can be expanded in a Taylor series about the maximum [177]:

| (9) |

dΦmax/dx = 0 at Φmax. Combining Eqns. 8 and 9 gives:

| (10) |

In Eqn. 10, the integrand is simply that of a Gaussian and gives:

| (11) |

p is a constant that reflects the curvature at the potential maximum. Rearranging Eqn. 11,

| (12) |

Deff is an effective diffusion coefficient. Eqn. 12 shows that the flux to the interface is slowed exponentially by an energy barrier of height Φmax/kBT. For Φmax/kBT ~ 5, the flux is reduced by 150 times; for Φmax/kBT ~ 10, the flux to the interface is reduced by a factor of 20,000! In Fig. 2, the time it takes for Curosurf to increase the surface pressure to > 20 mN/m increases from about 2 second for a clean interface to more than 250 seconds for a serum covered interface for the same bulk concentration of Curosurf, consistent with Eqn. 12 and Φmax/kBT ~ 5. Doubling the bulk surfactant concentration does not have nearly the effect of reducing the potential barrier by 50%. This is likely why simply increasing the surfactant concentration does not lead to a significant improvement in surfactant adsorption in the presence of albumin or other charged, surface-active inhibitors. To stabilize colloidal particles indefinitely (from coagulation in 10 seconds to more that one year) against equilibrium aggregation, the energy barrier height need only be ~ 15 kBT [170]. For the relatively fast cycles of expansion and compression under normal breathing (of order seconds), the energy barrier does not have to be very high to effectively inhibit surfactant adsorption.

From Eqn. 12, the ratio of the diffusion-limited (Φ=0) flux, Jo, to the actual flux, J, at a fixed bulk concentration is proportional to the exponential of the potential maximum, Φmax [177]:

| (13) |

To enhance surfactant adsorption in the presence of proteins, it is essential to know how to manipulate Φ. At the time Eqn. 8 was originally derived, neither the origin of the attraction between colloid particles (and LS aggregates), nor the functional form of the repulsion or attraction were known. In the 1940’s, Derjaguin, Landau, [168] Verwey, and Overbeek [169] (DLVO) combined the van der Waals/London dispersion attraction [178] with double-layer electrostatic repulsion [136] to give the functional form of Φ between two spheres of radius, a, at a separation, r, surface potential, ψs, and ion concentration, ni, via the Debye length, κ−1:

| (14) |

AH is the Hamaker constant that determines the magnitude of the attractive van der Waals/London dispersion forces [178]. The magnitude and range of the DLVO potential can be most easily be changed by changing the ionic strength of the solution, which decreases both κ−1 and Φmax (and to a lesser extent, AH [128]). Both Faraday and Zgismondy de-stabilized their gold sols by adding NaCl [170, 171]. If the negatively charged albumin and serum proteins act to induce a DLVO-type energy barrier to LS adsorption, just as albumin adsorbed to gold colloids inhibits coagulation, we expect that adding NaCl should promote LS adsorption.

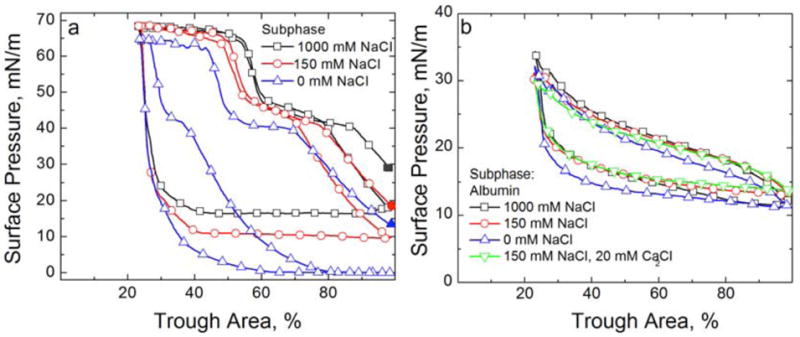

Figure 12a shows the effect of varying the NaCl concentration on the adsorption of 800 μg of Survanta on a buffered subphase (0.2 mM NaHCO3, pH ~ 7) with no albumin present. The respective Debye lengths are ~ 21 nm for the subphase with no added salt (mainly due to the buffer), .78 nm for the 150 mM NaCl and .3 nm for 1000 mM salt at 25° C. The minimum surface pressure after adsorption, but before compression, more than doubled from 14 mN/m for no salt, to 29 mN/m for 1000 mM NaCl. On the first compression, a characteristic shoulder at ~ 45 mN/m and collapse plateau at ~ 65 mN/m are visible for all three salt concentrations. On expansion, the minimum surface pressure drops to ~ 0 mN/m on the subphase with no NaCl, but is ~ 15 mN/m on the 1000 mM NaCl subphase. The length of the characteristic shoulder and collapse plateaus are roughly the same for the 150 and 1000 mN NaCl subphases on the first and second compressions; for the subphase with no NaCl, the shoulder and the collapse plateau are much reduced. These isotherms show that higher NaCl concentrations in the subphase promotes Survanta adsorption and respreading, even to a clean interface [179]. This should not be surprising since both the surfactant aggregates and monolayer contain a significant fraction of anionic lipids, which should lead to a DLVO repulsion even between the surfactant aggregates and the surfactant film, which is decreased by higher electrolyte concentrations.

Figure 12.

Cyclic isotherms of Survanta and albumin on a buffered subphase (0.2 mM NaHCO3 and pH=7) containing varying NaCl and CaCl2 concentrations. (a) 800 μg Survanta deposited onto a subphase containing varying NaCl concentrations. For all plots, the solid symbol denotes the surface pressure after adsorption before beginning the first compression cycle. The first compression, first expansion and second compression are shown for all three isotherms. □ 1000 mM NaCl subphase; ○ 150 mM NaCl subphase; △ 0 mM NaCl subphase. Increasing NaCl concentration increases the equilibrium surface pressure, the minimum surface pressure on expansion and promotes re-adsorption of collapsed material. (b) Fourth cycle isotherms of 2 mg/mL albumin on a buffered subphase (0.2 mM NaHCO3 and pH=7) containing varying concentrations of electrolytes. No Survanta has been deposited. □ 1000 mM NaCl subphase; ○ 150 mM NaCl subphase; △ 0 mM NaCl subphase; ▽ 150 mM NaCl, 20 mM CaCl2 subphase. The albumin isotherm is independent of the subphase electrolyte concentration indicating that the albumin adsorption and surface activity are unchanged over the range studied.

On the other hand, Fig. 12b shows that increasing the electrolyte concentration has little effect on the cyclic isotherms of 2 mg/ml albumin with no LS present. All the curves reach a maximum surface pressure of ~ 33 mN/m on compression and a minimum surface pressure of ~ 11 mN/m on expansion. Hence, the electrolyte does not lead to precipitation of the albumin or significant changes in the albumin adsorbed to the interface.

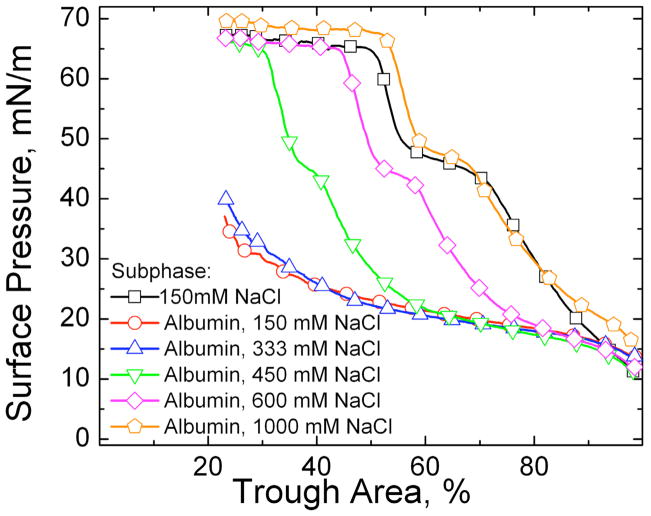

Fig. 13 shows the dramatic effects on adsorption as the NaCl concentration is increased when 800 μg of Survanta was deposited on a buffered subphase containing 2 mg/ml albumin. For NaCl concentrations up to 333 mM, the compression isotherms were indistinguishable and showed virtually no Survanta adsorption; they were identical to the albumin-only compression isotherms in Fig 12b. However, increasing the NaCl to 450 mM restored the characteristic shoulder and collapse plateau (Fig. 12a) typical of Survanta adsorbing to an albumin-free interface, although it required a greater compression (smaller trough area) to reach these plateaus. This is characteristic of slower than diffusion-limited adsorption. Further increases in NaCl concentration translate the compression isotherms to greater trough areas, implying greater adsorption; for 1000 mM NaCl, the compression isotherm with albumin in the subphase occurs at an even greater trough area at a given surface pressure than for Survanta adsorption on an albumin-free, 150 mM NaCl subphase. As the relationship between surface pressure and area/molecule is fixed for Survanta (See X-ray results in Table 1), this increase in trough area at a given surface pressure shows that more Survanta is adsorbing to the interface as the electrolyte concentration is increased. The added NaCl decreases κ−1, which causes a decrease in Φmax and an increase in the diffusive flux of surfactant to the interface, consistent with Eqns. 12–14.

Figure 13.

Fourth cycle compression isotherms of 800 μg Survanta on a buffered subphase (0.2 mM NaHCO3 and pH=7) containing varying NaCl concentrations and/or albumin (2 mg/mL when present). □ Survanta on a 150 mM NaCl subphase; ○ Survanta-albumin on a 150 mM NaCl subphase; △ Survanta-albumin on a 333 mM NaCl subphase; ▽ Survanta-albumin on a 450 mM NaCl subphase; ◇ Survanta-albumin on a 600 mM NaCl subphase; ⬠ Survanta-albumin on a 1000 mM NaCl subphase. A subphase containing 1000 mM NaCl is necessary to completely reverse the albumin inhibition and restore surfactant adsorption.

While the qualitative enhancement of adsorption is obvious from Fig. 13, it is difficult to directly calculate the theoretical enhancement of adsorption due to changes in electrolyte concentration from Eqn. 12–14 as many of the parameters (ψs, AH, a) are unknown. However, it is much easier to show how adsorption should scale with the valence of the ions in solution. One of the surprising early experimental discoveries in colloid science (1880–1900) was that the critical electrolyte concentration required to flocculate (CFC) a variety of positive and negative colloids was essentially independent of the chemical or physical details of the colloid and the electrolyte, but decreased as z−6, in which z is the valence of the ion opposite in charge to the colloid, which is known as the Schulze-Hardy rule [136, 180, 181]. Starting with the DLVO potential, Eqn. 14, rapid, diffusion-limited coagulation or flocculation should occur at an electrolyte concentration (called the critical flocculation concentration or CFC) at which Φmax = dΦ/dr = 0, that occurs when the separation between spheres, r =κ−1:

| (15) |

For ezψs/4kBT > 1, in the limit of large surface potentials, ψs, and the CFC ∝z−6, which successfully explained the Schulze-Hardy rule [136], and was one of the first important validations of the DLVO theory.

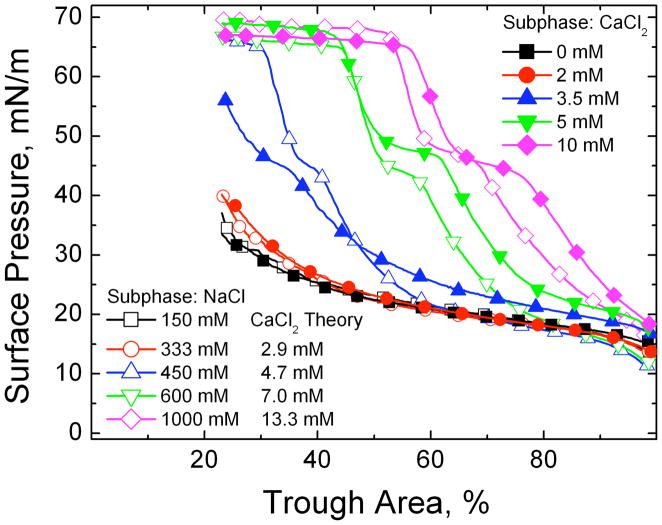

Fig. 14 shows that significantly lower levels of CaCl2 restore surfactant adsorption in the presence of albumin. For each NaCl concentration, the Schulze-Hardy rule (CFC proportional to z−6) was used to compare the isotherm with a functionally equivalent amount of CaCl2 in the subphase. To make the comparisons physiologically relevant, 150 mM NaCl was taken as a baseline electrolyte concentration (e.g. for 1000 mM total NaCl, the equivalent CaCl2 concentration for 850 mM NaCl is 2−6 * 850 = 13.3 mM). The CaCl2 concentrations relative to the NaCl concentrations (above 150 mM) to restore surfactant adsorption are in the ratio 2−(6.4±0.1), in excellent agreement with the scaling relationship predicted by DLVO theory. In analogy to the CFC, the ratio of divalent (calcium) to monovalent (sodium) ion concentration needed to induce diffusion limited surfactant adsorption is proportional to 2−6, which is, as far as we are aware, the first demonstration of the Schulze-Hardy rule for competitive adsorption. In designing surfactant replacement formulations, it would be impractical to use 1 M saline in a treatment due to its osmotic effects on lung tissue; however, 15 – 20 mM CaCl2 added to physiological saline has minimal effects on the fluid balance in a rat lung (H. W. Tauesch, unpublished observations). Biocompatible trivalent ions should be even more effective in enhancing surfactant adsorption and should be identified and tested.

Figure 14.

The fourth cycle compression isotherms of 800 μg lipid dispersion on a buffered saline subphase (0.2 mM NaHCO3 and pH=7) containing 2 mg/mL albumin and varying electrolyte concentrations. □ 150 mM NaCl subphase; ○ 333 mM NaCl subphase; △ 450 mM NaCl subphase; ▽ 600 mM NaCl subphase; ◇ 1000 mM NaCl; ■ 0 mM CaCl2, 150 mM NaCl subphase; ● 2 mM CaCl2, 150 mM NaCl subphase; ▲ 3.5 mM CaCl2, 150 mM NaCl subphase; ▼; 5 mM CaCl2, ◆ 150 mM NaCl subphase; 10 mM CaCl2, 150 mM NaCl subphase. For each NaCl concentration, the theoretical CaCl2 concentration according to the Schulze-Hardy/DLVO scaling (Eqn. 13) is given. The agreement between theory and experiment is excellent. Figure adapted from [79].

Polymers – Two Distinct Mechanisms of Destabilizing Colloids and Enhancing Adsorption

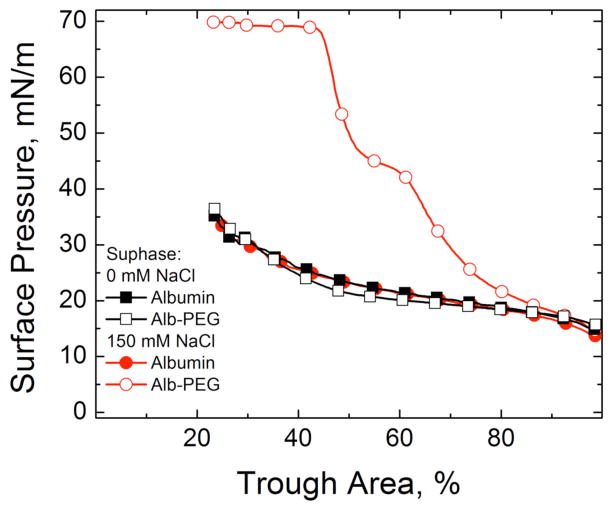

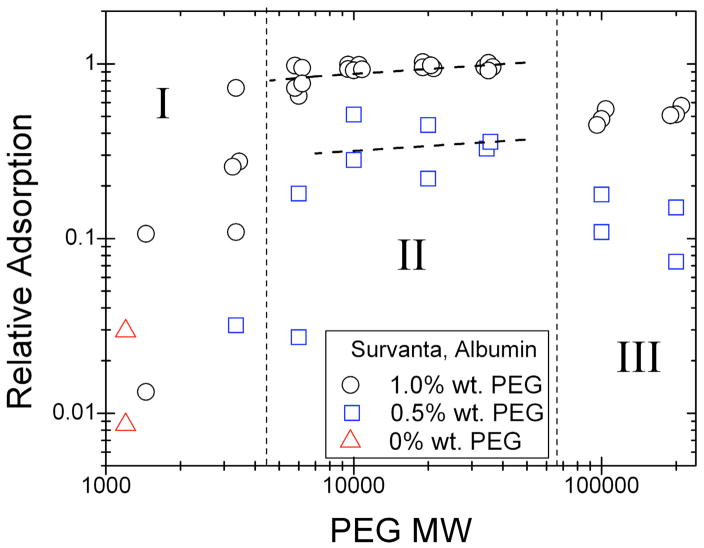

To continue the analogy between colloid stability and surfactant adsorption, other additives traditionally used to flocculate colloids [90, 136, 182–187] should also lead to enhanced surfactant adsorption in the presence of albumin or serum proteins. The first suggestion of the analogy between colloid stability and surfactant adsorption came from observations that adding non-ionic hydrophilic polymers such as polyethylene glycol (PEG) or dextran [9, 38, 41, 85, 95, 188–191] to clinical lung surfactants improved lung function in animals with lung injuries. This improved lung function correlated with enhanced surfactant adsorption to an albumin-covered air-water interface in vitro, as well as the flocculation of the LS aggregates in suspension [13, 42, 82–84, 95, 97, 192].

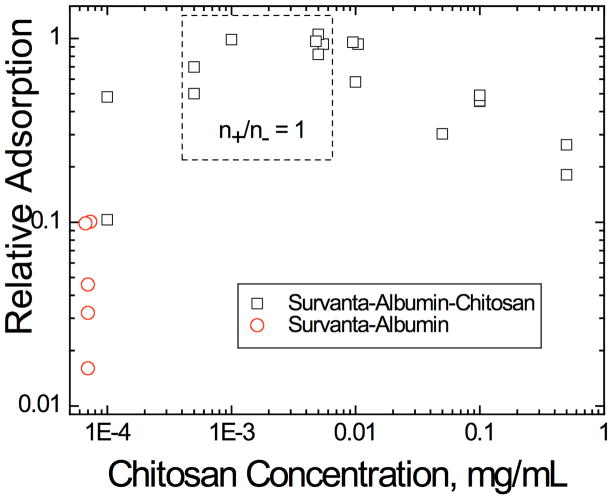

Polymer Depletion Forces

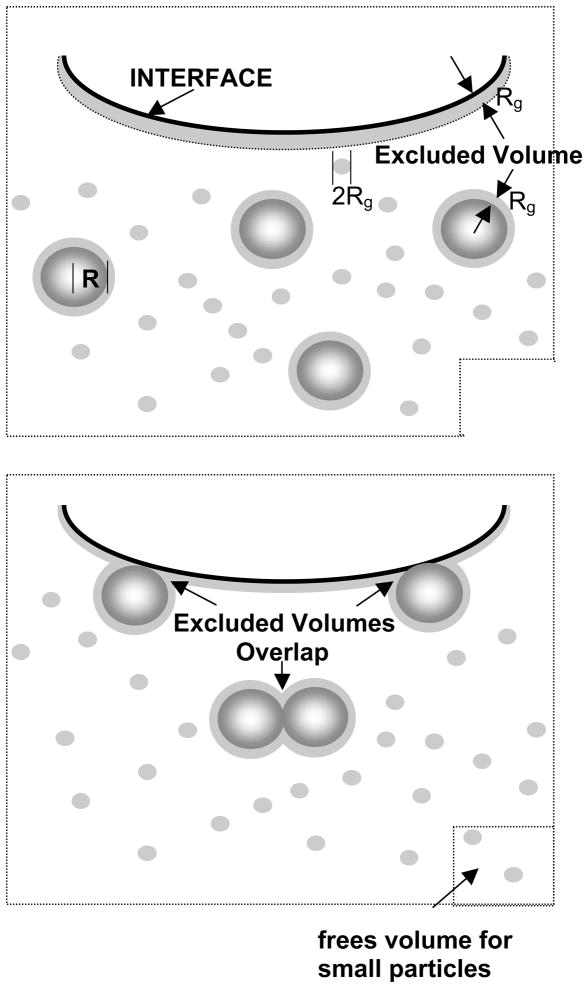

The unifying features of the polymers that reverse inhibition by this mechanism are: (1) they do not specifically adsorb to surfactant aggregates; (2) the polymers show no surface activity by themselves; (3) the polymers are small compared to surfactant aggregates (nm vs microns); (4) inactivation reversal occurs for all surfactant and polymer mixtures tried thus far. This suggests that a generic interaction, the so-called “depletion interaction” (Fig. 15), leads to inhibition reversal, rather than a specific interaction between particular surfactants and polymers.

Figure 15.

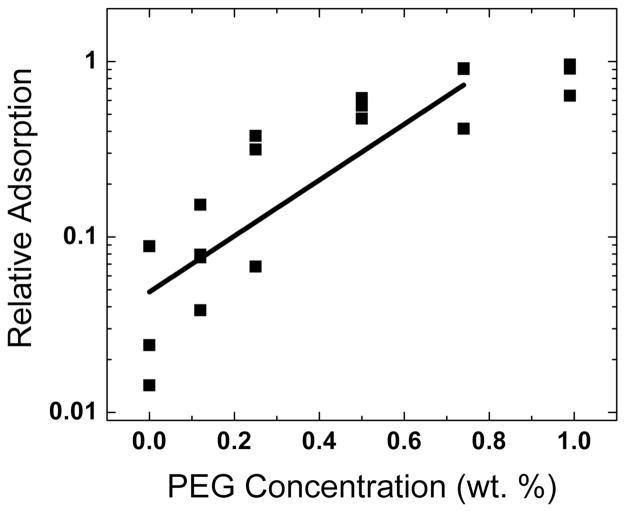

Origin of depletion forces in a binary sphere mixture. (Top) The centers of the small spheres are excluded from the hatched regions within one small sphere radius (Rg) of the larger spheres (radius R) or the interface. (Bottom) When the larger spheres move to the interface or toward each other, the hatched regions overlap, and the total volume accessible to the small spheres increases by this amount times the number of large spheres (total increase in volume in the bottom right-hand corner). The increase in the volume accessible to the polymer increases the entropy of the system, resulting in a net “depletion” force pushing the large spheres toward the interface or each other. Figure adapted from [42].