Abstract

Alkylating agents induce cell death in wild-type (WT) mouse embryonic fibroblasts (MEFs) by multiple mechanisms, including apoptosis, autophagy and necrosis. DNA polymerase β (Pol β) knockout (KO) MEFs are hypersensitive to the cytotoxic effect of alkylating agents, as compared to WT MEFs. To test the hypothesis that Parp1 is preferentially activated by methyl methanesulfonate (MMS) exposure of Pol β KO MEFs, we have examined the relationship between Pol β expression, Parp1 activation and cell survival following MMS exposure in a series of WT and Pol β deficient MEF cell lines. Consistent with our hypothesis, we observed elevated Parp1 activation in Pol β KO MEFs as compared to matched WT MEFs. Both the MMS-induced activation of Parp1 and the MMS-induced cytoxicity of Pol β KO MEFs are attenuated by pre-treatment with the Parp1/Parp2 inhibitor PJ34. Further, elevated Parp1 activation is observed following knockdown (KD) of endogenous Pol β, as compared to WT cells. Pol β KD MEFs are hypersensitive to MMS and both the MMS-induced hypersensitivity and Parp1 activation is prevented by pre-treatment with PJ34. In addition, the MMS-induced cellular sensitivity of Pol β KO MEFs is reversed when Parp1 is also deleted (Pol β/Parp1 double KO MEFs) and we observe no MMS sensitivity differential between Pol β/Parp1 double KO MEFs and those that express recombinant mouse Pol β. These studies suggest that Parp1 may function as a sensor of BER to initiate cell death when BER is aborted or fails. Parp1 may therefore function in BER as a tumor suppressor by initiating cell death and preventing the accumulation of cells with chromosomal damage due to a BER defect.

Keywords: Base excision repair, alkylating agents, Parp1, RNAi, DNA glycosylase, DNA polymerase beta

1. Introduction

DNA polymerase β (Pol β) plays a critical role in the repair of genomic base damage and is considered the predominant DNA polymerase in the base excision repair (BER) pathway [1]. The development of mouse embryonic fibroblasts (MEFs) deficient in Pol β clearly defined a requirement for Pol β in the repair of base damage mediated by the BER pathway [2]. Pol β is a bi-functional, two-domain, single-polypeptide 39kDa enzyme [3]. The polymerase activity responsible for gap-filling DNA synthesis in BER resides in the C-terminal 31kDa domain whereas the N-terminal 8kDa domain encodes a 5′deoxyribose phosphate (5′dRP) lyase activity that removes the sugar-phosphate lesion (5′dRP) [3]. The 5′dRP lesion is the product of AP endonuclease 1 (Ape1)-mediated hydrolysis of the abasic site generated following DNA glycosylase action [3]. The polymerase function of Pol β is responsible for gap-filling DNA synthesis in both the short-patch and long-patch sub-pathways of BER [4] yet alternate DNA polymerases have been demonstrated to complement the long-patch BER related DNA synthesis activity of Pol β in its absence when evaluated in cell extracts in vitro [5]. It is possible that the polymerase activity of Pol β is also complemented in vivo, as it is the 5′dRP lyase function of Pol β [6] that is essential and sufficient for alkylating-agent resistance in MEFs [7] and in human breast cancer cells [8]. In the absence of Pol β, cells are unable to efficiently repair the highly toxic 5′dRP moiety and therefore are hypersensitive to the cytotoxic effect of different alkylating agents such as methylmethane sulfonate (MMS), N-methyl-N-nitrosourea and N-methyl-N'-nitro-N-nitrosoguanidine (MNNG) [2], the thymidine analog 5-hydroxymethyl-2′-deoxyuridine [9] as well as the therapeutic alkylating agent temozolomide [8-10].

The 5′dRP lyase enzymatic activity, an essential BER gap-tailoring function, was first identified in mammalian cells as an enzymatic activity due to a 47kDa enzyme [10] but was later shown to be encoded by Pol β [6]. It is somewhat surprising however that the 5′dRP lyase function of Pol β is not complemented in vivo since there are several mammalian proteins that have 5′dRP lyase enzymatic activity. In addition to Pol β, DNA polymerase λ (Pol λ) and DNA polymerase ι (Pol ι), as well as the mitochondrial polymerase Pol γ have 5′dRP lyase activity and can function (in vitro) in the removal of the 5′dRP BER intermediate [11-16]. Further, the endonuclease VIII-like DNA glycosylases NEIL1 and NEIL2 both excise 5′dRP lesions with similar efficiency to Pol β [17]. However, the severe 5′dRP-mediated cell death observed in Pol β knockout (KO) MEFs [7] and Pol β deficient human cells [8] indicates that potential complementing activities provide little, if any, repair of the 5′dRP lesion generated during BER. This would suggest that the un-repaired 5′dRP lesion is not freely and readily available by additional cellular proteins outside of the BER complex that forms at the lesion site [1].

The molecular mechanism responsible for 5′dRP-mediated cell death is unknown. However, left un-repaired, 5′dRP lesions trigger mouse fibroblast and human breast cancer cell death via a p53-independent mechanism that does not involve apoptosis and does not induce the formation of autophagosomes [8,18]. Initial reports suggested a possible apoptotic mechanism of cell death [19] concomitant with an elevated level of chromosome aberrations following alkylating-agent exposure [19]. It was subsequently suggested that the observed apoptosis was the result of DNA double-strand breaks (DSBs) that form secondary to failed BER (in the absence of Pol β) following replication [20]. The formation of replication-dependent DSBs in Pol β KO MEFs following MMS-exposure is consistent with the increase in sister chromatid exchange (SCE) events observed in Pol β KO MEFs following MMS treatment [18]. However, the significantly long time-frame for the appearance of DSBs is not consistent with the relatively rapid (2 hrs) alterations in the cell cycle observed in Pol β KO MEFs following MMS exposure [18]. We have therefore hypothesized that the un-repaired 5′dRP lesion functions as a signal for cell death, possibly via protein binding and activation.

The DNA binding and signaling molecules Parp1 and Parp2 have each been implicated in BER [1], although the precise enzymatic role of either Parp isoform in BER is un-defined. Robust BER can be recapitulated in vitro in the absence of Parp1 [21] and neither bacteria (E. coli) nor yeast (S. cerevisiae or S. pombe) expresses a Parp homolog yet each is proficient in BER [22]. Interestingly, BER has been reported as both impaired [23] and proficient [24] in the absence of Parp1 [23,24]. Current models suggest that Parp1 and possibly Parp2 function as scaffold proteins in BER, facilitating the formation of BER complexes at the site of DNA damage via multiple protein-protein interactions, including interactions with Pol β, Xrcc1 and DNA LigIIIα [1,25]. Parp1 was observed to bind to the lesion site prior to Xrcc1 or Pol β [26,27]. Further, Parp1 was found in a complex of BER proteins cross-linked to a BER intermediate [28] and more recently it was observed that Parp1 and Ape1 from MEF extracts compete for the same 5′dRP BER intermediate [29]. It has been postulated that local, strand-break induced activation of Parp1 and the resultant synthesis of poly(ADP-ribose) (PAR) facilitates recruitment of the BER proteins Xrcc1 and Pol β to stimulate DNA repair [30]. In short, Parp1 (and Parp2) are involved in BER complex formation [1], Parp1 can recognize and bind to BER intermediates [29], Parp1 activation is observed upon BER initiation [30] and in un-related studies, it has been shown that Parp1 hyperactivation is recognized as an inducer of necrotic cell death [31].

We have hypothesized that Parp1 is the signaling protein that triggers cell death in MEFs when 5′dRP lesions are not repaired. In this study, we used genetically defined Pol β KO and knockdown (KD) mouse cell lines to define a role for Parp1 in the cellular response to alkylation damage in MEFs when BER fails or is aborted. These studies suggest that Parp1 (and likely Parp2) may function not only in BER protein recruitment but may also act as a sensor of completed BER and therefore Parp1 may be considered a BER sensor protein. As a BER sensor or checkpoint protein, Parp1 may therefore function as a tumor suppressor by preventing chromosomal damage that could accumulate due to a BER defect.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Chemicals and reagents

Cell culture media and supplies where from InVitrogen-Gibco (Carlsbad, CA). Fetal bovine serum was from Atlanta Biologicals (Lawrenceville, GA). Methyl methanesulfonate (MMS), DTT, Phosphocreatine di(tris) salt, Creatine Phosphokinase and NAD+ were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO). ATP and Parp Inhibitor VIII (PJ34) were obtained from GE Healthcare (Piscatway, NJ) and Calbiochem (San Diego, CA), respectively. The hairpin DNA substrate with a 3′-biotinylated end was synthesized by Integrated DNA Technologies (IDT; Coralville, IA). We used the following primary antibodies: DNA polymerase beta Ab-2; clone 61 (NeoMarker, Fremont, CA); Ape1 Ab (EMD Biosciences, Inc, San Diego, CA); Xrcc1 Ab (Bethyl Labs, Montgomery, TX); Parp1 mAb (Novus Biologicals, Littleton, CO); PCNA mAb (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA); PAR Ab (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA); anti-human MPG (Mab; clone 506-3D)[8]. Secondary antibodies GAM-HRP and GAR-HRP conjugates and signal generation substrates were from Bio-Rad (Hercules, CA) and Pierce (Rockford, IL), respectively. All electrophoresis reagents were from Bio-Rad (Hercules, CA).

2.2. Cell lines and culture conditions

Transformed WT MEF cells (16tsA, clone 1B5; 36.3; 53TAg and 92TAg), Pol β KO MEF cells (38Δ4; 50TAg and 88TAg), Pol β/Pol ι double KO MEF cells (19tsA, clone 2B2) and Pol β/Parp1 double KO MEF cells have been described previously [2]. Transformed WT MEFs HCC384 were derived from c57BI/6 day 14 embryos, as described previously [2]. The cell lines 16tsA, clone 1B5; 19tsA, clone 2B2; 88TAg and 92TAg are available from the ATCC. 92TAg cells engineered to express MPG have been reported previously [32]. The Pol β/Parp1 double KO MEF cells were kindly provided by Dr. J. Menissier-de Murcia (CNRS). MEFs were cultured at 37°C in a humidified incubator with 10% CO2 in DMEM supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum, penicillin (50 units/mL), streptomycin (50 μg/mL) and Glutamax (4 mmol/L). The Pol β/Parp1 double KO MEF cells were then immortalized with SV40 T antigen, as we have previously described [32].

2.3. Cloning and expression of mouse Pol β

Total RNA was isolated from 5 × 106 92TAg cells using Qiagen RNAeasy reagents. Total cDNA was prepared using a first-strand cDNA synthesis kit (InVitrogen) as described by the manufacturer, using oligo-dT as the primer. The mouse Pol β cDNA was then amplified by PCR using primers mBetaF (caccatgagcaaacgcaaggcgccg) and mBetaR (tcattcacttctatccttggg). EGFP cDNA was also amplified by PCR from pIRES2-EGFP (Clontech) using primers FEGFP (caccatggtgagcaagggcgagga) and REGFP (ttacttgtacagctcgtccatgccgagag). Each cDNA was then cloned via a Topoisomerase cloning procedure into the pENTR-D cloning plasmid (InVitrogen), as per the manufacturers protocol. The cloned mouse Pol β cDNA and EGFP cDNA were both sequence verified to be identical to that reported earlier (NM_011130.1 and www.addgene.com; respectively). The mouse Pol β open reading frame (ORF) and the EGFP ORF were each transferred from pENTR-mPolBeta or pENTR-EGFP; respectively, to a Gateway modified pIRES-Puro plasmid via LR recombination, as per the manufacturer (InVitrogen).

Pol β KO (88TAg) and Pol β/Parp1 double KO MEF cells were modified to express transgenic mouse Pol β or EGFP as follows: briefly, 1.5 × 105 cells were seeded into 60mm dishes and incubated for 24-30 hours at 10% CO2 at 37°C. The mouse Pol β expression plasmid (pIRES-Puro-mBeta) or the EGFP expression plasmid (pIRES-Puro-EGFP) was transfected using FuGene 6 Transfection Reagent (Roche Diagnostic Corp, Indianapolis, IN) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Stable cell lines were selected in puromycin (7 μg/ml) for 2 weeks, individual clones (stably expressing mouse Pol β or EGFP) were amplified and 30 μg of nuclear extract was analyzed by immunoblotting for the expression of mouse Pol β protein as described below.

2.4. Lentivirus expressing mouse Pol β specific shRNA

We have previously described a highly effective retroviral shRNA vector specific for mouse Pol β [32]. Using the same target sequence (gatcagtactactgtggtg), we cloned the corresponding hairpin sequence into the lentiviral vector pLL3.7 [33]. Lentiviral particles were generated by transfection of four plasmids (the control plasmid pLL3.7 or the mouse Pol β-specific shRNA plasmid pLLOXmPol β, plus pMD2.g(VSVG), pRSV-REV and pMDLg/pRRE) into 293-FT cells [33,34] using FuGene 6 transfection reagent (Roche Diagnostic Corp, Indianapolis, IN). Culture media from transfected cells was collected 48 hours after transfection to isolate the viral particles, passed through 0.45 μm filters, used immediately or stored at -80°C in single-use aliquots. Transduction of 92TAg and HCC384 cells with control lentivirus (GFP expression only) and mouse Pol β specific shRNA lentivirus was completed as follows: Briefly, 6.0 × 104 cells were seeded into 6-well plates and incubated for 24-30 hours at 10% CO2 at 37°C. Cells were transduced for 18 hours with virus at 32°C and cultured for 72 hours at 37°C and then seeded in 96-well plates at limiting dilution (0.3 cells/well) for the isolation of single-cell clones. Individual clones (control and stable KD of mouse Pol β protein) were amplified and 30 μg of nuclear extract was analyzed by immunoblotting for the expression of endogenous mouse Pol β protein as described below.

2.5. Cell extract preparation and immunoblot assays

Preparation of whole cell extract from 92TAg cells expressing MPG was as described [35]. Briefly, cells were washed three times with ice cold PBS and the pellet was suspended in buffer containing 20 mM Hepes-KCl, pH 7.9, 100 mM KCl, 0.2 mM EDTA, 10% glycerol and 1 mM DTT. Cells were disrupted by sonication for 10 seconds (four times) with 30-second incubations on ice in between each burst. The cell suspension was centrifuged for 20 minutes at 16400 RPM (4°C) to obtain whole cell extract and dialyzed overnight against re-suspension buffer (25 mM Hepes pH 7.9, 100 mM KCl, 12 mM MgCl2, 1 mM EDTA, 5% Glycerol, 2 mM DTT).

Nuclear extracts were prepared using the NucBuster nuclear protein extraction reagent (Novagen). Protein concentration was determined using Bio-Rad protein assay reagents according to the manufacturer's instructions. Nuclear protein (30 μg) was separated by electrophoresis in a 4-12% SDS-polyacrylamide gel and electrotransferred to a 0.45 μm nitrocellulose membrane (Trans-Blot, Bio-Rad). Antigens were detected using standard protocols. Primary antibodies: anti–Pol β, (NeoMarkers, #MS-1402-P0), 1,000×; anti-Ape1, (Novus, #NB-100-116), 3,000×; anti-Xrcc1, (Bethyl Labs, #A300-065A) 1,000×; anti-Parp, (Novus, #NB-100-112) 3,000×; anti-PCNA, (Santa Cruz, #sc-56) 1,000×; anti-MPG, [8] 1000× and the horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated secondary antibody (GAM-HRP or GAR-HRP; Bio-Rad) were diluted 10,000× in TBST/5% milk. Each membrane was stripped and reprobed with anti-PCNA antibodies to correct for differences in protein loading.

2.6. PAR assay

Cells (1.5 × 106) where seeded in 100mm dishes 24 hours before treatment. After 24 hours, media was removed and replaced with fresh media or media supplemented with Parp Inhibitor VIII (PJ34; Calbiochem, #528150) at a final concentration of 2 μM. After 30 minutes, cells were lysed immediately (0 time point) or media was replaced with MMS at a final concentration of 1.25 mM (diluted in media) and incubated for 15 or 30 minutes, as indicated in the figure legends. Extracts were prepared by washing the cells with PBS and preparing cell extract with 400 μl of 2× Laemmli Buffer. 20 μl of the cell extract was analyzed by immunoblot with a 1,000-fold dilution of an anti-PAR primary antibody (BD Pharmingen, #551813) followed by a 5,000-fold dilution of the horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated secondary goat anti-rabbit Ab (Pierce; cat#1858415).

2.7. Cell cytotoxicity assays

MMS induced cytotoxicity was determined by growth inhibition assays, essentially as we have described previously [32]. Briefly, cells were seeded in 96-well dishes at 1,200 cells per well in two sets. After 24 hours one set was pre-treated with the Parp inhibitor PJ34 at a final concentration of 2 μM. After 30 minutes of media or PJ34 pre-treatment, cells were treated with a range of concentrations of MMS for one hour (+/- PJ34, 2 μM). Drug-containing medium was replaced with fresh media or media containing PJ34 (2 μM) and the plates were incubated at 37°C for 48 hours at which point the total cell number was determined by a modified 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide (MTT) assay (MTS; Promega, Madison, WI) [36]. Metabolically active cells were quantified by the bioreduction of the MTS tetrazolium compound by recording absorbance at 490nm using a microplate reader. Results were calculated from the average of four separate experiments and are reported as the % of treated cells relative to the cells in control wells (% Control).

3. Results

3.1. Increased Parp1 activation following MMS exposure in the absence of Pol β

These studies were designed to address our hypothesis that Parp1 is the signaling protein that triggers cell death in MEFs when cells are deficient in Pol β and the BER intermediate 5′dRP is not repaired. We utilized a series of SV40 T-Antigen transformed WT and Pol β KO MEF cell lines. As depicted in Fig. 1, each of the cell lines have similar expression levels of the BER proteins Parp1, Xrcc1 and Ape1. Our human MPG antibody [8] does not cross-react with mouse Mpg/Aag and repeated attempts to validate antibodies specific for mouse Mpg were unsuccessful. However, as we have reported [32], Mpg glycosylase activity of both MEF WT and MEF Pol β knockout (KO) cell lines is low but uniform and suggests that MEFs generally have a low, yet sufficient level of expression of Mpg to initiate repair of the MMS-induced lesions, in-line with a previous report from one of us [18]. Further, these studies confirm that the WT cells all express similar levels of Pol β protein (lanes 1,3,5 & 7) and as expected, no Pol β protein is detected in the Pol β KO cell lines (lanes 2,4,6 & 8). All of the cell lines express Pol ι except for the Pol β/Pol ι double KO cell line 19tsA, as we and others have reported [37,38].

Fig. 1. WT and Pol β KO MEFs used in this study.

Expression of the DNA repair proteins Pol β, Ape1, Xrcc1, Parp1 and PCNA in MEFs as determined by immunoblot analysis of nuclear proteins isolated from the following MEF cells: 92TAg (lane 1), 88TAg (lane 2), 53TAg (lane 3), 50TAg (lane 4), 36.3 (lane 5), 38Δ4 (lane 6), 16tsa (lane 7) and 19tsA (lane 8).

Parp1 is part of the BER machinery [37] and can be found in a complex with other BER proteins, as was shown previously by two different experimental methodologies [26,28]. Using a similar approach, we confirmed that Parp1, as well as the BER proteins Ape1, Pol β, MPG and Xrcc1 can bind to a BER substrate by incubating a hairpin oligonucleotide containing a single MPG substrate (Etheno-2′-deoxyAdenosine) with whole cell extracts prepared from MEFs expressing human MPG [32]. Proteins bound to the substrate were cross-linked by incubation with formaldehyde (see Supplementary data and methods, Appendix A) and purified from unbound proteins by affinity purification via the biotin moiety linked to the 3′ end of the DNA hairpin oligonucleotide, essentially as described [26]. Purified proteins were released from the DNA by heating to reverse the formaldehyde-induced crosslinks, thereby separating the protein complexes. The purified BER proteins were then analyzed by immunoblot, as shown in Fig. S1. This is similar to that reported by Dianov and colleagues [26] and importantly, demonstrates that Parp1 binds to a BER substrate, as do the other BER proteins MPG, Ape1, Xrcc1 and Pol β.

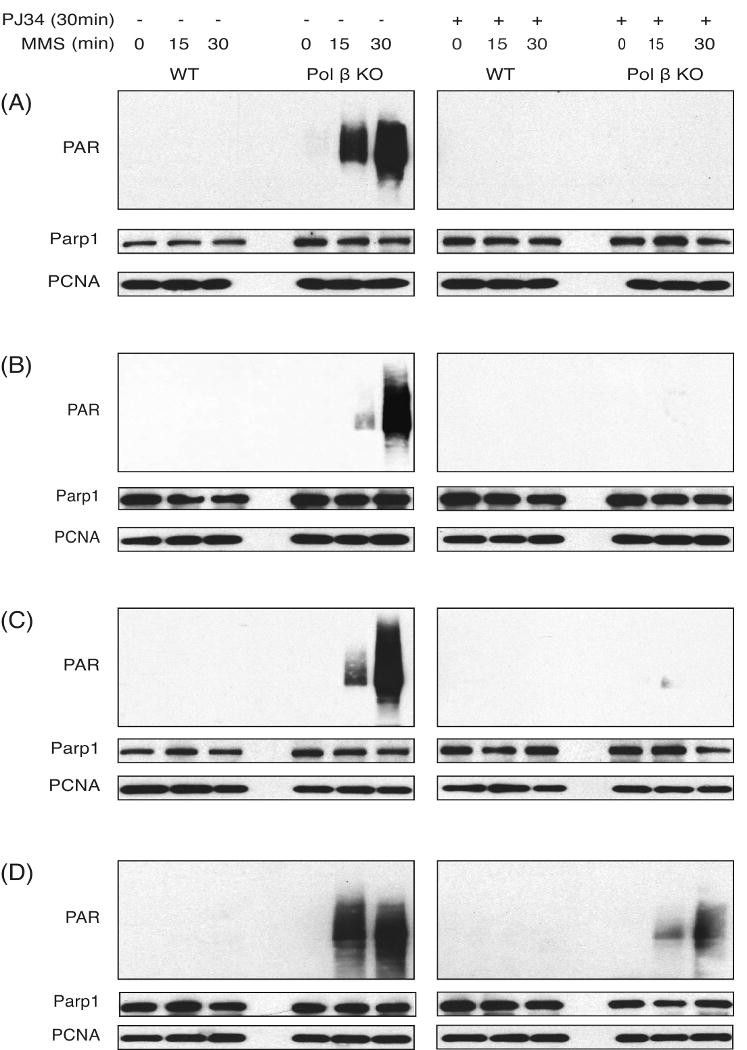

Parp1 binding to a BER substrate supports the current BER model in which Parp1 is recruited to the lesion site to facilitate BER complex formation, including the recruitment of Xrcc1/DNA ligase III and Pol β to complete repair [1,26,40]. Once bound to the lesion site, Parp1 undergoes rapid, low-level auto-modification (ADP-ribosylation). This self-imposed post-translational modification helps facilitate recruitment of Xrcc1 to complete repair [38]. We therefore reasoned that inability to complete repair due to the absence of Pol β would perpetuate the DNA strand-break induced activation of Parp1, preferentially in the Pol β KO cells. Activation of Parp1 in cells can be monitored by the presence of PAR in whole cell lysates, probing for PAR synthesis and accumulation by immunoblot analysis. In support of this hypothesis, DNA repair proficient cells (WT) show little or no evidence of Parp1 activation following challenge to 1.25 mM MMS (Fig. 2A-D, left panel). Note however that over-exposure of these immunoblots reveals a very low level of Parp1 activation in WT cells (Fig. 4C and data not shown). However, cells deficient in Pol β expression show a rapid and robust activation of Parp1 within 15 minutes after exposure of the cells to the same low dose of MMS (1.25 mM). Further, an even greater level of Parp1 activation is observed 30 minutes after MMS treatment (Fig. 2A-D, left panel). In 3 of the 4 Pol β KO cell lines, all of the observed Parp1 activation can be blocked by a 30 minute pre-treatment with the Parp1/Parp2 inhibitor PJ34 (2 μM) (Fig. 2A-C, right panel). In the fourth Pol β KO cell line (19tsA), a majority of the Parp1 activation can be blocked by pre-incubation with PJ34 (Fig. 2D, right panel). These data show very clearly that failed BER due to loss of Pol β leads to rapid and robust Parp1 activation following DNA damage induction mediated by MMS exposure.

Fig. 2. Preferential Parp1 activation in Pol β KO cells following MMS exposure.

Parp1 activation was determined in MEF cell extract by immunoblot analysis, measuring the synthesis of PAR in the absence (left panel) or in the presence of PJ34 (2 μM, right panel), after exposure with MMS (1.25 mM) for 0, 15 or 30 minutes in [92TAg (WT) and 88TAg (Pol β KO); Panel-A], [53TAg (WT) and 50TAg (Pol β KO); Panel-B], [36.3 (WT) and 38Δ4 (Pol β KO); Panel-C] and [16tsa (WT) and 19tsA (Pol β/Pol ι double KO); Panel-D] MEFs. Parp1 and PCNA expression was determined by immunoblot. PCNA expression is shown as a loading control.

Fig. 4. Mouse Pol β knockdown causes robust Parp1 activation and Parp1 dependent cell death following MMS exposure in MEFs.

(A & B) BER protein expression as determined by immunoblot analysis of nuclear proteins isolated from the 92TAg cells or 92TAg cells transduced with a mouse Pol β shRNA lentiviral vector (A) or the HCC384 cells or HCC384 cells transduced with a mouse Pol β shRNA lentiviral vector (B). (A) Proteins isolated from the shRNA expressing clone (92TAg/Polβ-KD(3); lane 2) as compared to proteins isolated from control cells (92TAg; lane 1) are shown in (A) and from the shRNA expressing clone (HCC384/Polβ-KD(1); lane 2) as compared to proteins isolated from control cells (HCC384; lane 1) are shown in (B). Pol β, Ape1, Xrcc1 and Parp1 expression was determined by immunoblot. PCNA expression is shown as a loading control. (C & D) Parp1 activation was determined in cell extracts by immunoblot analysis, measuring the synthesis of PAR after exposure with MMS (1.25 mM) for 0, 15 or 30 minutes in (C) 92TAg cells [WT] or 92TAg cells transduced with a mouse Pol β shRNA lentiviral vector, clone 3 [Pol β KD] or (D) HCC384 cells [WT] or HCC384 cells transduced with a mouse Pol β shRNA lentiviral vector, clone 1 [Pol β KD]. PCNA expression is shown as a loading control. (E & F) MMS-induced cytotoxicity following PJ34 pre-treatment was evaluated by culturing (E) 92TAg cells (open squares) or 92TAg cells transduced with a mouse Pol β shRNA lentiviral vector (92TAg/Polβ-KD(3); open circles) or (F) HCC384 cells (open squares) or HCC384 cells transduced with a mouse Pol β shRNA lentiviral vector (HCC384/Polβ-KD(1); open circles), in 96-well plates for 24 hours prior to exposure with media (open squares or open circles) or PJ34 (filled squares or filled circles; 2 μM) for 30 minutes. After PJ34 pre-treatment, cells were then treated with MMS and viable cells were determined using a modified MTT assay as described in Fig. 3.

3.2. Inhibition of Parp1 in Pol β null MEFs provides partial resistance to MMS

The hallmark phenotype of Pol β KO MEFs is an increase in cytotoxicity following exposure to alkylating agents such as MMS, MNNG and temozolomide [2]. We therefore evaluated the four matched WT and Pol β KO cell pairs for sensitivity to the alkylating agent MMS, as this has been the most commonly used alkylating agent for the characterization of Pol β KO cells [2]. Based on our observation that MMS induces an elevated level of Parp1 activation in Pol β KO MEFs (as compared to WT MEFs) and that Parp1 inhibition can protect MEFs, cortical neurons, PC12, SH-SY5Y and HeLa cells from DNA damage-induced cell death [31,39-42], we reasoned that a potent Parp inhibitor may provide some level of phenotypic rescue, leading to an increase in the survival of Pol β KO cells exposed to MMS. Parp1 and Parp2 were inhibited by either pre-treating cells (30 min) with PJ34 before addition of MMS or treating cells simultaneously with PJ34 and MMS. PJ34 was used at a concentration (2 μM) sufficient to prevent MMS-induced Parp-activation in the Pol β KO cells (Fig. 2). After an hour of MMS exposure, cells were re-fed normal growth media (+/- PJ34, 2 μM), grown for 48 hours and surviving cells were measured by an MTS assay (Fig. 3). In line with reports that Parp inhibition can potentiate the cell killing effect of many DNA damaging agents, including alkylating agents [38,43-45], blocking Parp activation in the WT MEFs increased the cell killing effect of MMS at most doses (Fig. 3). This potentiation effect was observed for both the pre-treatment and simultaneous treatment regimen. However, the MMS-induced cytotoxicity of Pol β KO cells was not increased by Parp inhibition. Conversely the MMS-induced cytotoxicity of Pol β KO cells was reduced when Parp was inhibited. Two of the Pol β KO MEF cell lines (88TAg; Fig. 3A,E & 50TAg; Fig. 3B,F) showed a marked improvement in cell survival when Parp was inhibited and the cells were challenged with MMS, as evidenced by as much as a 10-fold increase in survival for the +PJ34 treated Pol β KO cells at the highest doses of MMS. In some cases, the survival curve of the Pol β KO cells + PJ34 was similar to the WT cells treated with PJ34 (Fig. 3A & F). One Pol β KO cell line (38Δ4) showed an intermediate or variable response to the Parp inhibitor. Whereas simultaneous treatment of the 38Δ4 cells with PJ34 and MMS restored survival equal to that of the WT (36.3) cells (MMS+PJ34, Fig. 3G), pre-treatment with PJ34 provided rescue at only the highest doses of MMS (Fig. 3C). Finally, the Pol β/Pol ι double KO cell line was only mildly rescued by Parp inhibition. This was not entirely unexpected, as PJ34 treatment was found to only prevent some (a majority) of the MMS-induced Parp activation (Fig. 2D, right panel). The involvement of Parp1 in the hypersensitive phenotype of Pol β KO MEFs is consistent with earlier reports that un-repaired 5′dRP lesions trigger MEF [7,32] and human breast cancer [8] cell death via a mechanism that does not involve apoptosis and does not induce the formation of autophagosomes [8], suggesting a necrotic form of cell death [31].

Fig. 3. Chemical inhibition of Parp1 sensitizes WT MEFs yet provides partial resistance to MMS in Pol β KO MEFs.

Wild type (92TAg, 53TAg, 36.3 and 16tsa; open squares), Pol β KO (88TAg, 50TAg and 38Δ4; open circles) and Pol β/Pol ι double KO (19tsA; open circles) MEFs were seeded in 96-well plates in two sets. After 24 hours, cells were pre-treated with media (open squares or open circles) or PJ34 (filled squares or filled circles) at a final concentration of 2 μM. After 30 minutes of media or PJ34 pre-treatment, cells were treated with a range of concentrations of MMS for one hour (A, B, C and D). A second set was treated with media (open squares or open circles) or media supplemented with PJ34 (2 μM) and MMS (0.25-2.0 mM) simultaneously (filled squares or filled circles) for one hour (E, F, G and H). Drug-containing medium was replaced with fresh media or media containing PJ34 and the plates were incubated at 37°C for 48 hours and viable cells were determined using a modified MTT assay. Plots show the % viable cells as compared to untreated (control) cells. Means are calculated from quadruplicate values in each experiment. Results indicate the mean ± S.E. of four independent experiments.

3.3. Pol β down-regulation in WT MEFs leads to elevated Parp activation and Parp-dependent cell death following MMS exposure

The general trend observed in Pol β KO cells is that MMS treatment leads to hyper-activation of Parp1 that contributes to the elevated level of cell death in Pol β KO cells as compared to WT cells (Fig. 2 & 3). As with many studies using MEF cells isolated from gene-targeted KO mice, direct comparison is made between a Pol β KO cell line and a WT cell line, each derived from embryos of the same litter to minimize genetic variation (i.e., an isogenic cell line pair). However, this may not guarantee a true isogenic system. For example, the WT cell line 16tsA is WT for Pol ι while the littermate-derived Pol β KO cell line 19tsA is null for Pol ι [37,38]. To avoid any suggestion of genetic variation that may complicate interpretation of the role of Parp1 in the hypersensitive phenotype of Pol β KO MEFs, we developed a lentiviral system for expression of mouse Pol β specific shRNA, based on the target sequence for our retroviral shRNA system reported earlier [32]. We transduced two different WT MEF cells: 92TAg and HCC384. Stable cell lines expressing the mouse Pol β specific shRNA are devoid of detectable Pol β expression, as determined by immunoblot analysis (Fig. 4A, B). Expression of the BER proteins Ape1, Xrcc1 and Parp1 are similar when comparing the 92TAg and HCC384 cells and the corresponding lentiviral-transduced cells that show a Pol β KD phenotype (Fig. 4A, B). Similar to the results discussed above for the Pol β KO cells, the Pol β KD cells have a highly elevated level of Parp1 activation following MMS exposure (Fig. 4C, D) whereas the 92TAg and HCC384 WT cells show little or no Parp1 activation following MMS treatment. The Pol β KD cells are functionally similar to the gene targeted KO cells. Both the 92TAg/PolβKD and HCC384/PolβKD cells are hypersensitive to MMS as compared to the corresponding WT cell line (Fig. 4E, F). This is consistent with our previous results and others that strong knockdown of Pol β in MEFs leads to hypersensitivity to alkylating agents [32,46]. Most importantly, this isogenic system clearly demonstrates the role of Parp1 activation in the hypersensitivity of Pol β deficient MEFs. For both the 92TAg/PolβKD and HCC384/PolβKD cells, Parp1 inhibition by pre-treatment with the Parp1/Parp2 inhibitor PJ34 significantly enhances survival following MMS exposure (Fig. 4E, F). Interestingly, there is some slight variation in response even when comparing the 92TAg cells (Fig. 4E) and the HCC384 cells (Fig. 4F), supporting the significance of developing a truly isogenic system using shRNA-mediated gene expression knockdown. For example, the 92TAg cells were slightly sensitized to MMS when Parp1 was inhibited whereas the viability of the HCC384 cells was not altered by Parp1 inhibition (Fig. 4E, F). In both cases however, Parp1 inhibition provides a significant survival advantage for the corresponding Pol β KD cells (92TAg/PolβKD and HCC384/PolβKD), supporting our hypothesis that Parp1 activation is involved in the hypersensitivity of Pol β deficient MEFs to alkylating agents.

3.4. Complementation of Pol β KO MEFs and Pol β/Parp1 double KO MEFs with mouse Pol β – impact of Parp1 expression on MMS sensitivity in the absence of Pol β

The use of small molecule Parp inhibitors such as PJ34 to inhibit Parp1 and Parp2 activation provides significant support for our hypothesis that Parp1 activation promotes the hypersensitivity of Pol β deficient MEFs to alkylating agents. However, there are 18 Parp family members that are involved in many biological processes [47]. Although only Parp1 and Parp2 have been implicated in BER and in response to DNA damage [37], potential off-target effects of inhibitors such as PJ34 (and others) is always a distinct possibility. Therefore, we reasoned that if Parp1 was the primary Parp-family member that regulates the cellular response to failed repair of the BER intermediate 5′dRP, then we should take advantage of the previously developed Pol β/Parp1 double KO MEF cells [51]. To directly compare the cellular response of the Pol β KO and Pol β/Parp1 double KO MEFs to those that express Pol β, we cloned the mouse Pol β cDNA and developed stable cell lines that express either GFP (as a control) or mouse Pol β. An immunoblot analysis of the Pol β KO and Pol β/Parp1 double KO cells as well as the corresponding GFP or mouse Pol β expressing stable cell lines are shown (Fig. 5A, B). Pol β is only expressed in the transfected, stable cell lines (shown in lanes 4&5) and Parp1 is only expressed in the Pol β KO cells, with no Parp1 expression observed in the Pol β/Parp1 double KO cells (Fig. 5A, B). Comparable to the results shown above, the Pol β KO and Pol β KO/GFP cells show an MMS-induced hyper-activation of Parp1, as evidenced by the elevated level of PAR formation 15 minutes following MMS treatment of the Pol β KO and Pol β KO/GFP cells (Fig. 5C, group 1 & 2). Further, analogous to that shown above when comparing WT and Pol β KO cell lines (Fig. 2), ectopic expression of Pol β in the Pol β KO cell line suppresses MMS-induced Parp1 activation (Fig. 5C, group 3). Analysis of the Pol β/Parp1 double KO cells and the derived GFP and mouse pol β expressing clones show no PAR synthesis following MMS exposure (Fig. 5D), suggesting that most if not all of the PAR synthesized following MMS exposure of Pol β KO cells (Fig. 5C) is mediated by Parp1.

Fig. 5. Impact of Parp1 expression on MMS sensitivity in the absence of Pol β.

(A & B) BER protein expression as determined by immunoblot analysis of nuclear proteins isolated from the (A) 88TAg cells or 88TAg cells complemented with mouse Pol β or (B) Pol β/Parp1 double KO cells or Pol β/Parp1 double KO cells complemented with mouse Pol β. Proteins isolated from two separate mouse Pol β (pIRES-Puro-mBeta) expressing clones are shown: (A) [88TAg/mPol β (27) and 88TAg/mPol β (28); lanes 4 and 5] as compared to proteins isolated from control cell (88TAg; lane 1) or pIRES-Puro-EGFP transfected in 88TAg cell [88TAg/EGFP (1) and 88TAg/EGFP (2); lanes 2 and 3]. (B): [Pol β/Parp1 double KO/mPol β (6) and Pol β/Parp1 double KO/mPol β (7); lanes 4 and 5] as compared to proteins isolated from control cells (Pol β/Parp1 double KO cell; lane 1) or pIRES-Puro-EGFP transfected in Pol β/Parp1 double KO cells [Pol β/Parp1 double KO/EGFP (1) and Pol β/Parp1 double KO/EGFP (2); lanes 2 and 3]. Pol β, Ape1, Xrcc1 and Parp1 expression was determined by immunoblot. PCNA expression is shown as a loading control. (C & D) Parp1 activation was determined in cell extract by immunoblot analysis, measuring the synthesis of PAR after exposure with MMS (1.25 mM) for 0 or 15 minutes in (C) 88TAg cells (group 1) or 88TAg cell transfected with pIRES-Puro-EGFP (group 2) or 88TAg cells transfected with pIRES-Puro-mBeta (group 3) or (D) Pol β/Parp1 double KO cells (group 1) or Pol β/Parp1 double KO cells transfected with pIRES-Puro-EGFP (group 2) or Pol β/Parp1 double KO cells transfected with pIRES-Puro-mBeta (group 3). PCNA expression is shown as a loading control. (E) MMS-induced cytotoxicity following PJ34 pre-treatment was evaluated by culturing 88TAg cells [88Tag], 88TAg cells transfected with pIRES-Puro-EGFP [88Tag/GFP] or 88TAg cells complemented with mouse Pol β [88Tag/mPolβ], in 96-well plates for 24 hours prior to exposure with media [open bars] or PJ34 (2 μM) [filled bars] for 30 minutes. After PJ34 pre-treatment, cells were then treated with MMS (1.5 mM) and viable cells were determined using a modified MTT assay as described in Fig. 3. (F) MMS-induced cytotoxicity following PJ34 pre-treatment was evaluated by culturing Pol β/Parp1 double KO cells transfected with pIRES-Puro-EGFP or Pol β/Parp1 double KO cell complemented with mouse Pol β, in 96-well plates for 24 hours prior to exposure with media [open bars] or PJ34 (2 μM) [filled bars] for 30 minutes. After PJ34 pre-treatment, cells were then treated with MMS (1.5 mM) and viable cells were determined using a modified MTT assay as described in Fig. 3.

We next extended our functional comparison of the Pol β KO and Pol β/Parp1 double KO cells, as well as, the corresponding GFP or mouse Pol β expressing stable cell lines by exposing each to MMS (1.5 mM) and measuring survival, as described in the Methods section. Both the 88TAg cells and the derived GFP expressing cells (88TAg/GFP) were highly sensitive to MMS whereas the 88TAg cells expressing recombinant mouse Pol β (88TAg/mPolβ) showed marked resistance, similar to other genetically WT cells such as 92TAg (Fig. 5E). Similar to the WT cells described above (Fig. 4E), the 88TAg/mPolβ cells were slightly sensitized to MMS by Parp1 inhibition (Fig. 5E). However, Parp1 inhibition provided a significant survival advantage for the 88TAg and GFP-expressing cells (Fig. 5E). On the contrary, there is little or no difference in survival following MMS exposure when comparing GFP-expressing and mouse Pol β expressing Pol β/Parp1 double KO cells (Pol β/Parp1 KO/GFP vs. Pol β/Parp1 KO/mPolβ) (Fig. 5F). In support of the overall hypothesis put forth herein, the MMS-induced hypersensitive phenotype of Pol β KO cells (as compared to Pol β expressing cells) requires or is exacerbated by Parp1 activation (Fig. 5).

4. Discussion

Alkylators such as MMS induce a spectrum of DNA base lesions [48] as well as single-strand and double-strand DNA breaks. Failure to repair these lesions or DNA breaks triggers cell death via apoptosis, autophagy and necrosis. The role of Pol β in repair of MMS-induced lesions is restricted to base lesions removed by the methylation-specific DNA glycosylase MPG (AAG) [18]. Once repair is initiated, Pol β is essential for repair gap tailoring to remove the 5′dRP BER intermediate. Although it is clear that the un-repaired 5′dRP BER intermediate is the cytotoxic lesion that renders Pol β KO MEFs hypersensitive to alkylating agents [7], the specific cell death mechanism that is triggered by failure to repair the 5′dRP BER intermediate (BER failure) following alkylation damage has not been adequately resolved.

This study tested the hypothesis that Parp1 is a sensor of “BER failure” and that a major function of Parp1 within the context of the BER pathway is to monitor the status of BER and initiate cell death if the Pol β-dependent repair process fails (i.e., BER failure). To test this, we utilized a series of WT and Pol β KO MEF cell lines (Fig. 1). Each littermate cell line pair contains a Pol β WT and Pol β KO cell line and each expresses Parp1. Treatment of WT and Pol β KO MEFs with MMS induces a rapid and robust activation of Parp1 in Pol β KO cells, with little or no measurable activation in WT cells (Fig. 2). As an alternative, we developed a lentiviral system to down-regulate or KD Pol β in MEFs. This lentiviral-based mouse Pol β specific shRNA expression system leads to a complete loss of Pol β expression in MEFs (Fig. 4) and in preliminary studies, it appears that KD in mice is sufficient to induce post-natal lethality (not shown), similar to that observed in gene-targeted KO mice [49]. As with all four Pol β KO cell lines evaluated, exposure of Pol β KD cells to MMS initiates rapid Parp1 activation, with little or no MMS-induced Parp1 activation in the parental WT cells (Fig. 4). Data presented from these studies of Pol β KO and KD cells therefore supports our hypothesis that Parp1 provides a cellular signal of failed BER via PAR synthesis.

Alkylation damage can induce cell death via a mismatch repair dependent process [50,51], activation of caspases [52] or calpains [53], induction of autophagy [54] or the generation of DNA double strand breaks and H2AX recruitment [55]. In a multitude of studies of alkylation-induced cell death in MEFs, Parp1 activation and the onset of necrosis is the primary means of cell death [45,47,52,56-58]. Importantly, the specific molecular activator of Parp1 due to alkylation damage has not been clearly defined. Parp1 is activated by breaks to ssDNA and dsDNA [47,58], by Erk1/2-mediated phosphorylation [59] or by a direct interaction with ERK2, the latter independent of DNA damage [60]. In DNA repair proficient cells, the expectation is that alkylation-induced Parp1 activation is via DNA breaks [47,58], but it is not clear if activation is mediated by failed BER or via replication-induced specific ssDNA breaks, dsDNA breaks or a spectrum of both. It is also possible that cell death arises from mitotic catastrophe [61]. To address the connection between Pol β status, Parp1 activation and cell death, we utilized Parp1/Parp2 inhibitors [31,39,62] to prevent Parp1 activation resulting from BER failure. Since we found that a deficiency in Pol β caused DNA damage-induced Parp1 activation, we hypothesized that blocking Parp1 activation may provide some level of phenotypic rescue in the Pol β KO and KD cells. In support of this hypothesis, we find that the alkylation-sensitive phenotype of all four Pol β KO cells used in this study was rescued, either completely or partially, by Parp1 inhibition (Fig. 3). An even stronger phenotypic rescue is observed in two independently derived Pol β KD MEF cell lines (Fig. 4). The phenotypic (cell death) rescue observed herein is similar to that observed in neurons [63,64], cardiac myocytes [65-69] and ischemia-reperfusion stroke models [63,64] whereby cell death is Parp1 dependent and inhibition of Parp1 activation prevents stress-induced cell death. Additional studies will be required to determine if this resistant phenotype is long-lived or if the resulting un-repaired BER intermediates lead to the formation of DNA double-strand breaks and the onset of apoptosis after several rounds of replication [70].

Complicating the interpretation of the DNA-damage induced survival curves of the Pol β KO and Pol β KD cell lines (Fig. 3, 4) is the well-documented potentiation of DNA damaging agents by Parp1 inhibition [43]. It is hypothesized that blocking Parp1 activation prevents Parp1-regulated DNA repair processes, increasing the cell killing and anti-tumor effect of many DNA damaging agents, including alkylating agents, cisplatin, radiation and topoisomerase-inhibitors [71,72]. Many of these earlier studies utilized DNA repair proficient MEFs and exposure to extremely high doses of DNA damaging agent. It is likely that Parp1 inhibition shifts the cell death mechanism from necrosis to apoptosis [45]. In the context of BER-mediated repair of alkylated bases, blocking Parp1 should therefore prevent BER complex recruitment [73,74], leading to accumulation of cytotoxic replication-induced DSBs [75]. In-line with the potentiating effect of Parp1-inhibition, we do observe an increase in MMS-induced cell killing in WT cells when Parp1 is inhibited (Fig. 3, 4). However, Parp1 inhibition provides a survival advantage to Pol β KO cells, equal to that of the Parp1 inhibited WT cells for most doses of MMS (Fig. 3, 4). This led us to speculate that the alkylation-damage mediated hypersensitive phenotype of Pol β KO (and KD) cells requires Parp1 activation. Although we observe a phenotypic rescue by Parp1 inhibition, we recognize that the ‘damage’ from a combination of alkylation treatment and BER failure will undoubtedly lead to an accumulation of DSBs and enhanced apoptotic cell death [43,45].

To directly test the role of Parp1 in the alkylation-damage mediated hypersensitive phenotype of Pol β deficient cells, we compared the alkylation response of Pol β KO cells and Pol β/Parp1 double KO cells. In support of our hypothesis that Parp1 activation is the result of BER failure (i.e., Pol β deficiency), ectopic expression of mouse Pol β in Pol β KO MEFs restored MMS resistance and attenuated MMS-induced Parp1 activation (Fig. 5). The Pol β/Parp1 double KO cells did not show any MMS-induced PAR synthesis, implicating Parp1 as the major DNA damage response Parp-family member, as expected [47]. In support of our hypothesis that Parp1 is required for the Pol β hypersensitive phenotype, there was no MMS-induced cytotoxic difference when comparing Pol β/Parp1 double KO cells expressing GFP and those that express mouse Pol β (Fig. 5).

In summary, we propose that Pol β KO MEFs are hypersensitive to alkylating agents due to hyper-activation of Parp1. Once repair is initiated and the DNA backbone is hydrolyzed, Parp1 is engaged to recruit the necessary proteins required for the completion of repair [1], including Xrcc1 and Pol β [73,74]. However, we show that BER failure (due to Pol β deficiency) leads to a rapid, elevated level of Parp1 activation, implicating Parp1-mediated necrosis as the cause of the Pol β hypersensitive phenotype [8,10]. This work shows one way by which defective BER can lead to cell death (via Parp1 activation), but there may be other ways as well. These studies are in-line with our recent report that Pol β deficiency in human cells gives rise to cellular sensitivity to the chemotherapeutic alkylating agent temozolomide by a mechanism that does not involve apoptosis and does not lead to the formation of autophagosomes [8]. Together with the Parp1 activation described here, it is our expectation that cell death due to failed BER is mediated by Parp1 activation. Continuing studies will explore how Parp1 and related PAR- and NAD+-metabolic enzymes impact BER and in turn, affect DNA damage or chemotherapeutic response in BER-proficient as compared to BER-deficient or BER-inhibited cells.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by a Research Scholar grant (RSG-05-246-01-GMC) from the American Cancer Society, grants from the Susan G. Komen Breast Cancer Foundation (Grant # BCTR0403276), NIH (1 R01 AG24364-01; P20 CA103730, 1 P20 CA132385-01 and 1P50 CA 097190 01A1), the Brain Tumor Society, the UPMC Health System Competitive Medical Research Fund and the University of Pittsburgh Cancer Institute to RWS. This project is also funded, in part, under a grant with the Pennsylvania Department of Health. The Department of Health specifically disclaims responsibility for any analyses, interpretations or conclusions. We would like to thank Dr. Ben Van Houten (University of Pittsburgh) and Dr. Christi A. Walter (University of Texas Health Science Center San Antonio) for critically reading his manuscript.

Appendix A

Footnotes

Conflict of interest statement: The authors state that there is no conflict of interest.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Almeida KH, Sobol RW. A unified view of base excision repair: lesion-dependent protein complexes regulated by post-translational modification. DNA Repair. 2007;6:695–711. doi: 10.1016/j.dnarep.2007.01.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sobol RW, Horton JK, Kuhn R, Gu H, Singhal RK, Prasad R, Rajewsky K, Wilson SH. Requirement of mammalian DNA polymerase-β in base-excision repair. Nature. 1996;379:183–186. doi: 10.1038/379183a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Beard WA, Wilson SH. Structure and mechanism of DNA polymerase Beta. Chem Rev. 2006;106:361–382. doi: 10.1021/cr0404904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Horton JK, Prasad R, Hou E, Wilson SH. Protection against methylation-induced cytotoxicity by DNA polymerase β-dependent long patch base excision repair. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2000;275:2211–2218. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.3.2211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fortini P, Pascucci B, Parlanti E, Sobol RW, Wilson SH, Dogliotti E. Different DNA polymerases are involved in the short- and long-patch base excision repair in mammalian cells. Biochemistry. 1998;37:3575–3580. doi: 10.1021/bi972999h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Matsumoto Y, Kim K. Excision of deoxyribose phosphate residues by DNA polymerase β during DNA repair. Science. 1995;269:699–702. doi: 10.1126/science.7624801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sobol RW, Prasad R, Evenski A, Baker A, Yang XP, Horton JK, Wilson SH. The lyase activity of the DNA repair protein β-polymerase protects from DNA-damage-induced cytotoxicity. Nature. 2000;405:807–810. doi: 10.1038/35015598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Trivedi RN, Wang XH, Jelezcova E, Goellner EM, Tang J, Sobol RW. Human methyl purine DNA glycosylase and DNA polymerase β expression collectively predict sensitivity to temozolomide. Molecular Pharmacology. 2008;74:505–516. doi: 10.1124/mol.108.045112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Horton JK, Joyce-Gray DF, Pachkowski BF, Swenberg JA, Wilson SH. Hypersensitivity of DNA polymerase beta null mouse fibroblasts reflects accumulation of cytotoxic repair intermediates from site-specific alkyl DNA lesions. DNA Repair (Amst) 2003;2:27–48. doi: 10.1016/s1568-7864(02)00184-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Price A, Lindahl T. Enzymatic release of 5′-terminal deoxyribose phosphate residues from damaged DNA in human cells. Biochemistry. 1991;30:8631–8637. doi: 10.1021/bi00099a020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bebenek K, Tissier A, Frank EG, McDonald JP, Prasad R, Wilson SH, Woodgate R, Kunkel TA. 5′-Deoxyribose phosphate lyase activity of human DNA polymerase iota in vitro. Science. 2001;291:2156–2159. doi: 10.1126/science.1058386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Prasad R, Bebenek K, Hou E, Shock DD, Beard WA, Woodgate R, Kunkel TA, Wilson SH. Localization of the deoxyribose phosphate lyase active site in human DNA polymerase iota by controlled proteolysis. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2003;278:29649–29654. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M305399200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Braithwaite EK, Prasad R, Shock DD, Hou EW, Beard WA, Wilson SH. DNA polymerase lambda mediates a back-up base excision repair activity in extracts of mouse embryonic fibroblasts. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2005;280:18469–18475. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M411864200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Braithwaite EK, Kedar PS, Lan L, Polosina YY, Asagoshi K, Poltoratsky VP, Horton JK, Miller H, Teebor GW, Yasui A, Wilson SH. DNA polymerase lambda protects mouse fibroblasts against oxidative DNA damage and is recruited to sites of DNA damage/repair. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:31641–31647. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C500256200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Garcia-Diaz M, Bebenek K, Gao G, Pedersen LC, London RE, Kunkel TA. Structure-function studies of DNA polymerase lambda. DNA Repair (Amst) 2005;4:1358–1367. doi: 10.1016/j.dnarep.2005.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Garcia-Diaz M, Bebenek K, Kunkel TA, Blanco L. Identification of an intrinsic 5′-deoxyribose-5-phosphate lyase activity in human DNA polymerase lambda: a possible role in base excision repair. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2001;276:34659–34663. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M106336200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Grin IR, Khodyreva SN, Nevinsky GA, Zharkov DO. Deoxyribophosphate lyase activity of mammalian endonuclease VIII-like proteins. FEBS Lett. 2006;580:4916–4922. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2006.08.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sobol RW, Kartalou M, Almeida KH, Joyce DF, Engelward BP, Horton JK, Prasad R, Samson LD, Wilson SH. Base Excision Repair Intermediates Induce p53-independent Cytotoxic and Genotoxic Responses. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2003;278:39951–39959. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M306592200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ochs K, Sobol RW, Wilson SH, Kaina B. Cells deficient in DNA polymerase β are hypersensitive to alkylating agent-induced apoptosis and chromosomal breakage. Cancer Research. 1999;59:1544–1551. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ochs K, Lips J, Profittlich S, Kaina B. Deficiency in DNA polymerase β provokes replication-dependent apoptosis via DNA breakage, Bcl-2 decline and caspase-3/9 activation. Cancer Res. 2002;62:1524–1530. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Srivastava DK, Berg BJ, Prasad R, Molina JT, Beard WA, Tomkinson AE, Wilson SH. Mammalian abasic site base excision repair. Identification of the reaction sequence and rate-determining steps. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1998;273:21203–21209. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.33.21203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Friedberg EC, Walker GC, Siede W, Wood RD, Schultz RA, Ellenberger T. DNA Repair and Mutagenesis. 2nd. ASM Press; Washington, D.C.: 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dantzer F, de La Rubia G, Menissier-De Murcia J, Hostomsky Z, de Murcia G, Schreiber V. Base excision repair is impaired in mammalian cells lacking Poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase-1. Biochemistry. 2000;39:7559–7569. doi: 10.1021/bi0003442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Vodenicharov MD, Sallmann FR, Satoh MS, Poirier GG. Base excision repair is efficient in cells lacking poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase 1. Nucleic Acids Res. 2000;28:3887–3896. doi: 10.1093/nar/28.20.3887. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Almeida KH, Sobol RW. Increased Specificity and Efficiency of Base Excision Repair through Complex Formation. In: Siede W, Doetsch PW, Kow YW, editors. DNA Damage Recognition. Marcel Dekker Inc.; New York: 2005. pp. 33–64. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Parsons JL, Dianov GL. Monitoring base excision repair proteins on damaged DNA using human cell extracts. Biochem Soc Trans. 2004;32:962–963. doi: 10.1042/BST0320962. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Parsons JL, Dianova II, Allinson SL, Dianov GL. Poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase-1 protects excessive DNA strand breaks from deterioration during repair in human cell extracts. Febs J. 2005;272:2012–2021. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2005.04628.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lavrik OI, Prasad R, Sobol RW, Horton JK, Ackerman EJ, Wilson SH. Photoaffinity labeling of mouse fibroblast enzymes by a base excision repair intermediate. Evidence for the role of poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase-1 in DNA repair. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2001;276:25541–25548. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M102125200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cistulli C, Lavrik OI, Prasad R, Hou E, Wilson SH. AP endonuclease and poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase-1 interact with the same base excision repair intermediate. DNA Repair (Amst) 2004;3:581–591. doi: 10.1016/j.dnarep.2003.09.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Dantzer F, Ame JC, Schreiber V, Nakamura J, Menissier-de Murcia J, de Murcia G. Poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase-1 activation during DNA damage and repair. Methods Enzymol. 2006;409:493–510. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(05)09029-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zong WX, Ditsworth D, Bauer DE, Wang ZQ, Thompson CB. Alkylating DNA damage stimulates a regulated form of necrotic cell death. Genes & Development. 2004;18:1272–1282. doi: 10.1101/gad.1199904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Trivedi RN, Almeida KH, Fornsaglio JL, Schamus S, Sobol RW. The Role of Base Excision Repair in the Sensitivity and Resistance to Temozolomide Mediated Cell Death. Cancer Research. 2005;65:6394–6400. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-0715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rubinson DA, Dillon CP, Kwiatkowski AV, Sievers C, Yang L, Kopinja J, Zhang M, McManus MT, Gertler FB, Scott ML, Van Parijs L. A lentivirus-based system to functionally silence genes in primary mammalian cells, stem cells and transgenic mice by RNA interference. Nature Genetics. 2003;33:401–406. doi: 10.1038/ng1117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Poeschla EM, Wong-Staal F, Looney DJ. Efficient transduction of nondividing human cells by feline immunodeficiency virus lentiviral vectors. Nature Medicine. 1998;4:354–357. doi: 10.1038/nm0398-354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kataoka N, Dreyfuss G. A simple whole cell lysate system for in vitro splicing reveals a stepwise assembly of the exon-exon junction complex. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:7009–7013. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M307692200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Berridge MV, Tan AS. Characterization of the cellular reduction of 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide (MTT): subcellular localization, substrate dependence, and involvement of mitochondrial electron transport in MTT reduction. Archives of Biochemistry and Biophysics. 1993;303:474–482. doi: 10.1006/abbi.1993.1311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wood RD, Mitchell M, Sgouros J, Lindahl T. Human DNA repair genes. Science. 2001;291:1284–1289. doi: 10.1126/science.1056154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Woodhouse BC, Dianov GL. Poly ADP-ribose polymerase-1: An international molecule of mystery. DNA Repair (Amst) 2008;7:1077–1086. doi: 10.1016/j.dnarep.2008.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Yu SW, Wang H, Poitras MF, Coombs C, Bowers WJ, Federoff HJ, Poirier GG, Dawson TM, Dawson VL. Mediation of poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase-1-dependent cell death by apoptosis-inducing factor. Science. 2002;297:259–263. doi: 10.1126/science.1072221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ethier C, Labelle Y, Poirier GG. PARP-1-induced cell death through inhibition of the MEK/ERK pathway in MNNG-treated HeLa cells. Apoptosis. 2007;12:2037–2049. doi: 10.1007/s10495-007-0127-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Paquet-Durand F, Silva J, Talukdar T, Johnson LE, Azadi S, van Veen T, Ueffing M, Hauck SM, Ekstrom PA. Excessive activation of poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase contributes to inherited photoreceptor degeneration in the retinal degeneration 1 mouse. J Neurosci. 2007;27:10311–10319. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1514-07.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Iwashita A, Yamazaki S, Mihara K, Hattori K, Yamamoto H, Ishida J, Matsuoka N, Mutoh S. Neuroprotective effects of a novel poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase-1 inhibitor, 2-[3-[4-(4-chlorophenyl)-1-piperazinyl] propyl]-4(3H)-quinazolinone ( FR255595), in an in vitro model of cell death and in mouse 1-methyl-4-phenyl-1,2,3,6-tetrahydropyridine model of Parkinson's disease. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2004;309:1067–1078. doi: 10.1124/jpet.103.064642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Tentori L, Graziani G. Chemopotentiation by PARP inhibitors in cancer therapy. Pharmacol Res. 2005;52:25–33. doi: 10.1016/j.phrs.2005.02.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Horton JK, Stefanick DF, Naron JM, Kedar PS, Wilson SH. Poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase activity prevents signaling pathways for cell cycle arrest following DNA methylating agent exposure. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2005;280:15773–15785. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M413841200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Horton JK, Stefanick DF, Wilson SH. Involvement of poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase activity in regulating Chk1-dependent apoptotic cell death. DNA Repair (Amst) 2005;4:1111–1120. doi: 10.1016/j.dnarep.2005.05.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Polosina YY, Rosenquist TA, Grollman AP, Miller H. ‘Knock down’ of DNA polymerase β by RNA interference: recapitulation of null phenotype. DNA Repair (Amst) 2004;3:1469–1474. doi: 10.1016/j.dnarep.2004.05.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hassa PO, Haenni SS, Elser M, Hottiger MO. Nuclear ADP-ribosylation reactions in mammalian cells: where are we today and where are we going? Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 2006;70:789–829. doi: 10.1128/MMBR.00040-05. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Beranek DT. Distribution of methyl and ethyl adducts following alkylation with monofunctional alkylating agents. Mutation Research. 1990;231:11–30. doi: 10.1016/0027-5107(90)90173-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Gu H, Marth JD, Orban PC, Mossmann H, Rajewsky K. Deletion of a DNA polymerase β gene segment in T cells using cell type-specific gene targeting. Science. 1994;265:103–106. doi: 10.1126/science.8016642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Casorelli I, Pelosi E, Biffoni M, Cerio AM, Peschle C, Testa U, Bignami M. Methylation damage response in hematopoietic progenitor cells. DNA Repair (Amst) 2007;6:1170–1178. doi: 10.1016/j.dnarep.2007.03.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kaina B, Christmann M, Naumann S, Roos WP. MGMT: key node in the battle against genotoxicity, carcinogenicity and apoptosis induced by alkylating agents. DNA Repair (Amst) 2007;6:1079–1099. doi: 10.1016/j.dnarep.2007.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Cohausz O, Blenn C, Malanga M, Althaus FR. The roles of poly(ADP-ribose)-metabolizing enzymes in alkylation-induced cell death. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2008;65:644–655. doi: 10.1007/s00018-008-7516-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Moubarak RS, Yuste VJ, Artus C, Bouharrour A, Greer PA, Menissier-de Murcia J, Susin SA. Sequential activation of poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase 1, calpains, and Bax is essential in apoptosis-inducing factor-mediated programmed necrosis. Mol Cell Biol. 2007;27:4844–4862. doi: 10.1128/MCB.02141-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Kanzawa T, Germano IM, Komata T, Ito H, Kondo Y, Kondo S. Role of autophagy in temozolomide-induced cytotoxicity for malignant glioma cells. Cell Death Differ. 2004;11:448–457. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4401359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Meador JA, Zhao M, Su Y, Narayan G, Geard CR, Balajee AS. Histone H2AX is a critical factor for cellular protection against DNA alkylating agents. Oncogene. 2008;27:5662–5671. doi: 10.1038/onc.2008.187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Affar el B, Shah RG, Dallaire AK, Castonguay V, Shah GM. Role of poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase in rapid intracellular acidification induced by alkylating DNA damage. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99:245–250. doi: 10.1073/pnas.012460399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Ha HC, Snyder SH. Poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase is a mediator of necrotic cell death by ATP depletion. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1999;96:13978–13982. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.24.13978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Schreiber V, Dantzer F, Ame JC, de Murcia G. Poly(ADP-ribose): novel functions for an old molecule. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2006;7:517–528. doi: 10.1038/nrm1963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Kauppinen TM, Chan WY, Suh SW, Wiggins AK, Huang EJ, Swanson RA. Direct phosphorylation and regulation of poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase-1 by extracellular signal-regulated kinases 1/2. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:7136–7141. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0508606103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Cohen-Armon M, Visochek L, Rozensal D, Kalal A, Geistrikh I, Klein R, Bendetz-Nezer S, Yao Z, Seger R. DNA-independent PARP-1 activation by phosphorylated ERK2 increases Elk1 activity: a link to histone acetylation. Mol Cell. 2007;25:297–308. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2006.12.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Russo AL, Kwon HC, Burgan WE, Carter D, Beam K, Weizheng X, Zhang J, Slusher BS, Chakravarti A, Tofilon PJ, Camphausen K. In vitro and in vivo radiosensitization of glioblastoma cells by the poly (ADP-ribose) polymerase inhibitor E7016. Clin Cancer Res. 2009;15:607–612. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-08-2079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Andrabi SA, Kim NS, Yu SW, Wang H, Koh DW, Sasaki M, Klaus JA, Otsuka T, Zhang Z, Koehler RC, Hurn PD, Poirier GG, Dawson VL, Dawson TM. Poly(ADP-ribose) (PAR) polymer is a death signal. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:18308–18313. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0606526103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Eliasson MJ, Sampei K, Mandir AS, Hurn PD, Traystman RJ, Bao J, Pieper A, Wang ZQ, Dawson TM, Snyder SH, Dawson VL. Poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase gene disruption renders mice resistant to cerebral ischemia. Nat Med. 1997;3:1089–1095. doi: 10.1038/nm1097-1089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Endres M, Wang ZQ, Namura S, Waeber C, Moskowitz MA. Ischemic brain injury is mediated by the activation of poly(ADP-ribose)polymerase. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 1997;17:1143–1151. doi: 10.1097/00004647-199711000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Fiorillo C, Ponziani V, Giannini L, Cecchi C, Celli A, Nassi N, Lanzilao L, Caporale R, Nassi P. Protective effects of the PARP-1 inhibitor PJ34 in hypoxic-reoxygenated cardiomyoblasts. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2006;63:3061–3071. doi: 10.1007/s00018-006-6345-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Oh KS, Lee S, Yi KY, Seo HW, Koo HN, Lee BH. A novel and orally active poly (ADP-ribose) polymerase-1 inhibitor, 2-[methoxycarbonyl(4-methoxyphenyl)methyl sulfanyl]-1H-benzimidazole-4-carboxylic acid amide (KR-33889), attenuates injury in in vitro model of cell death and in vivo model of cardiac ischemia. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2008 doi: 10.1124/jpet.108.143719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Pillai JB, Gupta M, Rajamohan SB, Lang R, Raman J, Gupta MP. Poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase-1-deficient mice are protected from angiotensin II-induced cardiac hypertrophy. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2006;291:H1545–1553. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.01124.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Pillai JB, Isbatan A, Imai S, Gupta MP. Poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase-1-dependent cardiac myocyte cell death during heart failure is mediated by NAD+ depletion and reduced Sir2alpha deacetylase activity. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:43121–43130. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M506162200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Yang KT, Chang WL, Yang PC, Chien CL, Lai MS, Su MJ, Wu ML. Activation of the transient receptor potential M2 channel and poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase is involved in oxidative stress-induced cardiomyocyte death. Cell Death Differ. 2006;13:1815–1826. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4401813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Liu X, Shi Y, Guan R, Donawho C, Luo Y, Palma J, Zhu GD, Johnson EF, Rodriguez LE, Ghoreishi-Haack N, Jarvis K, Hradil VP, Colon-Lopez M, Cox BF, Klinghofer V, Penning T, Rosenberg SH, Frost D, Giranda VL, Luo Y. Potentiation of temozolomide cytotoxicity by poly(ADP)ribose polymerase inhibitor ABT-888 requires a conversion of single-stranded DNA damages to double-stranded DNA breaks. Mol Cancer Res. 2008;6:1621–1629. doi: 10.1158/1541-7786.MCR-08-0240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Haince JF, Rouleau M, Hendzel MJ, Masson JY, Poirier GG. Targeting poly(ADP-ribosyl)ation: a promising approach in cancer therapy. Trends Mol Med. 2005;11:456–463. doi: 10.1016/j.molmed.2005.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Miknyoczki SJ, Jones-Bolin S, Pritchard S, Hunter K, Zhao H, Wan W, Ator M, Bihovsky R, Hudkins R, Chatterjee S, Klein-Szanto A, Dionne C, Ruggeri B. Chemopotentiation of temozolomide, irinotecan, and cisplatin activity by CEP-6800, a poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase inhibitor. Mol Cancer Ther. 2003;2:371–382. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.El-Khamisy SF, Masutani M, Suzuki H, Caldecott KW. A requirement for PARP-1 for the assembly or stability of XRCC1 nuclear foci at sites of oxidative DNA damage. Nucleic Acids Research. 2003;31:5526–5533. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkg761. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Mortusewicz O, Ame JC, Schreiber V, Leonhardt H. Feedback-regulated poly(ADP-ribosyl)ation by PARP-1 is required for rapid response to DNA damage in living cells. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007;35:7665–7675. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkm933. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Helleday T, Petermann E, Lundin C, Hodgson B, Sharma RA. DNA repair pathways as targets for cancer therapy. Nat Rev Cancer. 2008;8:193–204. doi: 10.1038/nrc2342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.