Abstract

Previously melittin, the α-helical basic honey bee venom peptide, was shown to inhibit F1-ATPase by binding at the β-subunit DELSEED motif of F1Fo ATP synthase. Herein, we present the inhibitory effects of the basic α-helical amphibian antimicrobial peptides, ascaphin-8, aurein 2.2, aurein 2.3, carein 1.8, carein 1.9, citropin 1.1, dermaseptin, maculatin 1.1, maganin II, MRP, or XT-7, on purified F1 and membrane bound F1Fo E. coli ATP synthase. We found that the extent of inhibition by amphibian peptides is variable. Whereas MRP-amide inhibited ATPase essentially completely (~96% inhibition), carein 1.8 did not inhibit at all (0% inhibition). Inhibition by other peptides was partial with a range of ~13% to 70%. MRP-amide was also the most potent inhibitor on molar scale (IC50 ~3.25 µM). Presence of an amide group at the c-terminal of peptides was found to be critical in exerting potent inhibition of ATP synthase (~20–40% additional inhibition). Inhibition was fully reversible and found to be identical in both F1Fo membrane preparations as well as in isolated purified F1. Interestingly, growth of Escherichia coli was abrogated in the presence of ascaphin-8, aurein 2.2, aurein 2.3, citropin 1.1, dermaseptin, magainin II-amide, MRP, MRP-amide, melittin, or melittin-amide but was unaffected in the presence of carein 1.8, carein 1.9, maculatin 1.1, magainin II, or XT-7. Hence inhibition of F1-ATPase and E. coli cell growth by amphibian antimicrobial peptides suggests that their antimicrobial/anticancer properties are in part linked to their actions on ATP synthase.

Keywords: F1Fo-ATP synthase, F1-ATPase, E. coli ATP synthase, Antimicrobial peptides, Amphibian; Enzyme inhibitors

F1Fo-ATP synthase is the primary source of cellular energy production in animals, plants, and almost all microorganisms by oxidative or photophosphorylation. The ATP synthase enzyme is highly conserved and structurally similar in all organisms. This enzyme is the smallest known biological nanomotor and is composed of two rotary sectors, F1 and Fo. In its simplest form in Escherichia coli ATP synthase contains eight different subunits namely α3ß3γδεab2c10 with a total molecular mass of ~530 kDa. F1 corresponds to α3ß3γδε -and Fo to ab2c10. The reversible processess of ATP hydrolysis and synthesis occur on three catalytic sites in the F1 sector, whereas proton transport occurs through the membrane embedded Fo [1–2]. An important feature of the molecular mechanism of ATP synthase is that a “rotor” made up of γεc10 subunits undergoes rapid, continuous 360° rotation as catalysis proceeds [3]. γ-subunit is comprised of three α-helices. Two of these helices form a coiled coil and go right up into the central space of the α3ß3 hexagon. During ATP-driven proton transport, sequential ATP hydrolysis at the three catalytic sites generates rotation of γ, and rotation of the connected c10 ring against the a subunit moves protons outward across the membrane. A "stator" made up of b2δ subunits prevents corotation of catalytic sites and subunit a with the rotor. Conversely, during oxidative phosphorylation, rotation is in the opposite direction and generates ATP [4–5]. Detailed reviews of ATP synthase structure and function may be found in [6–13].

ATP synthase is critical to human health. Malfunction of this complex has been implicated in a wide variety of diseases including cancer, tuberculosis, neuropathy, Alzheimer’s, Parkinson’s, and the class of severely debilitating diseases known collectively as mitochondrial myopathies. Mutation in the a-subunit causes a form of the neurodegenerative disease Leigh syndrome [14]. The Lysosomal storage disease, Kufs’ or Battens’, involves the c-subunit of ATP synthase. Alzhimer’s disease is associated with low expression of β-subunit and cytosolic accumulation of α-subunit. The nuropathy, ataxia, is also caused by dysfunction of ATP synthase. Increased blood pressure has been shown to involve subunit F6 circulating in the blood. This enzyme is not only implicated in many disease conditions but is also a likely therapeutic target in the treatment of diseases such as, cancer, heart disease, mitochondrial diseases, immune deficiency, cystic fibrosis, diabetes, ulcers, tuberculosis, Parkinson’s, and Alzheimer’s [15]. Interestingly, recent studies have suggested that ATP synthase present on the surface of several animal cell types is associated with multiple cellular processes including agiogenesis, lipid metabolism, regulation of intracellular pH, and apoptosis.

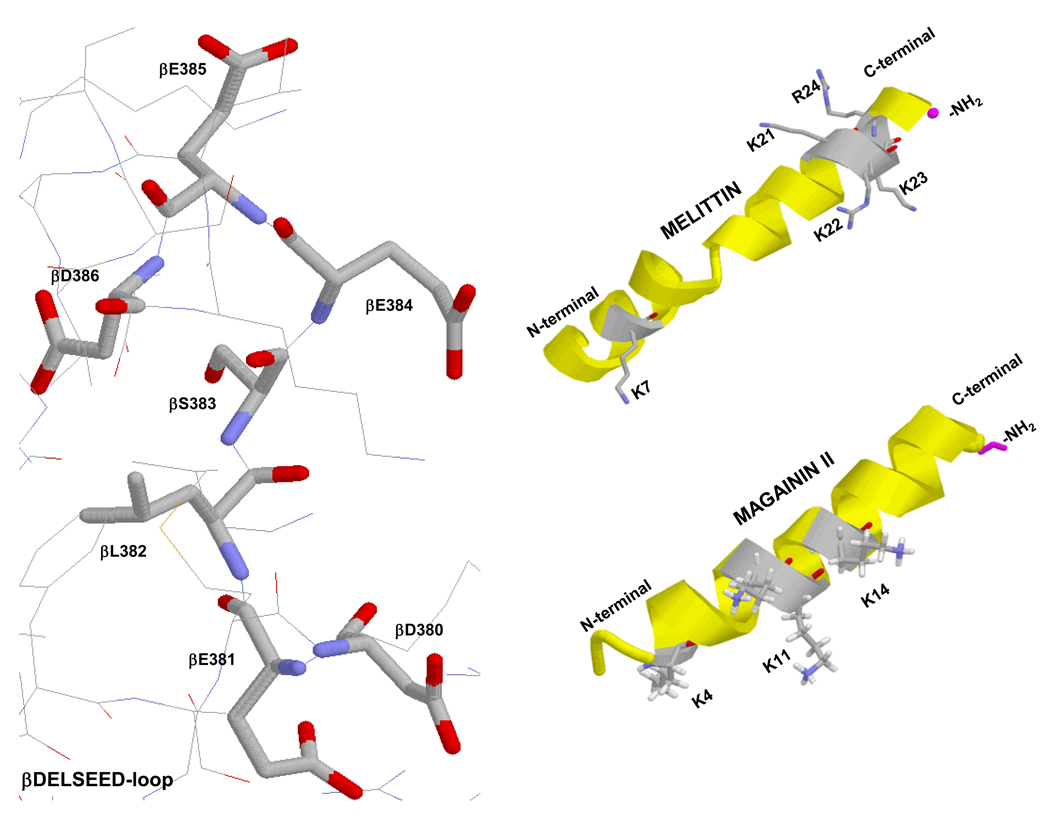

A wide range of natural and synthetic products including polyphenols and peptides are known to bind and inhibit ATP synthase. A detailed list of inhibitors and their action on ATP synthase in relation to human heath and disease is discussed in reference [15]. Plant based photochemical polyphenols bind to multiple targets in the body including ATP synthase ([15] and references therein). Recently, the polyphenols resveratrol, piceatannol and quercetin, were shown to prevent synthetic and hydrolytic activities of bacterial and mitochondrial ATP synthase, suggesting that the beneficial dietary effect of polyphenols may be in part linked to the blocking of ATP synthesis in tumor cells, thereby leading to apoptosis [16]. Several basic peptides including the honey bee venom peptide melittin, bacterial/chloroplast ε subunit, SynA2, SynC (the presequence of yeast cytochrome oxidase subunit IV, synthetic or wild-type), form a basic amphiphilic α-helical structure and have been shown to bind at β-subunit 1residues 380–386 with the sequence βDELSEED of ATP synthase [17–19] (Fig. 1).

Figure 1. X-ray structures (A) of mitochondrial ATP synthase showing βDELSEED residues and (B)α-helical structure of melittin and magainin II.

Rasmol software was used to generate these figures. For ATP synthase β-subunit DELSEED PDB file 1H8E was used [49]. βDELSEED is the proposed peptide binding site E. coli residue numbering is shown. The 26-residue long structure of the α-helical honey bee (Apis mellifera) venom peptide melittin, was generated by using PDB file 2MLT [50]. Five positively charged residues along with amide group (NH2) on the c-terminal are identified. The 23-residue long structure of the α-helical amphibian (Xenopus laevis) peptide magainin II, was generated by using PDB file 2MAG [51]. Three positively charged residues along with amide group (NH2) on the c-terminal are identified.

Previously it was found that replacement of five acidic residues in βDELSEED of thermophilic Bacillus PS3 by Alanine resulted in the loss of inhibition by the ε-subunit, an intrinsic inhibitor of F1-ATPase. Likewise, replacement of the basic residues of the c-terminal region of the ε- subunit by Alanine, also abrogated the inhibition of F1-ATPase activity [20].

Antimicrobial peptides (AMPs) were first described in insects as an inducible system of protection against bacterial infection [21–23]. AMPs have been isolated from a wide variety of phyla, including microbes, plants, invertebrates and vertebrates and show potent activity against Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria, fungi, parasites, and enveloped viruses and are known to play an important role in vertebrate innate immunity [24]. Most AMPs are cationic, amphipathic, between 10 and 50 residues in size, and frequently include a c-terminal amide group. There are ~1500 identified AMPs in the Antimicrobial Database [25], of which 1154 (77%) are identified as having antibacterial activity, 438 with antifungal activity, 94 with anticancer activity and 86 with antiviral activity. Frog skin is the single largest source of AMPs identified in the database. Many amphibian AMPs have structural resemblance to melittin, the honey bee venom peptide. For example magainin II, a 23-residue long amphibian AMP, from frog skin and the 26-residue long melittin form corresponding α-helical amphipathethic structures (Fig.1). Based on α-helical amphipathic structure, net positive charge, antimicrobial activity, and anticancer activity we selected several peptides of amphibian origin to examine ATP synthase as a potential target molecule (see Table 1).

Table 1.

Peptides examined in this study

| Peptide | Sequence | Length | Net positive charge |

Species |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ascaphin-8 | GFKDLLKGAAKALVKTVLF | 19 | 3 | Ascaphus truei |

| Aurein 2.2 | GLFDIVKKVVGALGSL-NH2 | 16 | 1 | Litoria aurea |

| Aurein 2.3 | GLFDIVKKVVGAIGSL-NH2 | 16 | 1 | Litoria aurea |

| Caerin 1.8 | GLFKVLGSVAKHLLPHVVPVIAEK | 24 | 4 | Litoria chloris |

| Caerin 1.9 | GLFGVLGSIAKHVLPHVVPVIAEK | 24 | 3 | Litoria chloris |

| Citropin 1.1 | GLFDVIKKVASVIGGL | 16 | 1 | Litoria citropa |

| Dermaseptin | ALWKTMLKKLGTMALHAGKAALGAAADTISQGTQ | 34 | 4 | Phyllomedusa sauvagei |

| Maculatin 1.1 | GLFVGVLAKVAAHVVPAIAEHF-NH2 | 22 | 2 | Litoria genimaculata |

| Magainin II | GIGKFLHSAKKFGKAFVGEIMNS | 23 | 4 | Xenopus laevis |

| Magainin II-amide | GIGKFLHSAKKFGKAFVGEIMNS-NH2 | 23 | 4 | Xenopus laevis |

| Melittin | GIGAVLKVLTTGLPALISWIKRKRQQ | 26 | 5 | Apis mellifera |

| Melittin-amide | GIGAVLKVLTTGLPALISWIKRKRQQ-NH2 | 26 | 5 | Apis mellifera |

| MRP | AIGSILGALAKGLPTLISWIKNR | 23 | 3 | Rana tagoi |

| MRP-amide | AIGSILGALAKGLPTLISWIKNR-NH2 | 23 | 3 | Rana tagoi |

| XT-7 | GLLGPLLKIAAKVGSNLL | 18 | 2 | Xenopus tropicalis |

In this paper we present the first direct experimental evidence of amphibian antimicrobial peptides as potential E. coli ATP synthase inhibitors using both purified F1-ATPase and membrane bound F1Fo ATP synthase preparations.

Materials and Methods

Measurement of growth yield in limiting glucose medium; preparation of E. coli membranes; purification of E. coli F1; assay of ATPase activity of membranes or purified F1

The E. coli strain was pBWU13.4/DK8 [26]. ATP synthesis by oxidative phosphorylation was measured by growth on succinate plates (a non fermentable carbon source). Oxidative and/or substrate level phosphorylation were measured on limiting glucose (3–5 mM instead of typical 30 mM glucose containing minimal media) as in [27]. E. coli membranes were prepared as in [28]. It should be noted that this procedure involves three washes of the initial membrane pellets. The first wash is performed in buffer containing 50 mM TES pH 7.0, 15% glycerol, 40 mM 6-aminohexanoic acid, and 5 mM p-aminobenzamidine. The following two washes are performed in buffer containing 5 mM TES pH 7.0, 15% glycerol, 40 mM 6-aminohexanoic acid, 5 mM p-aminobenzamidine, 0.5 mM DTT, and 0.5 mM EDTA. Prior to the experiments, membranes were washed twice more by resuspension and ultracentrifugation in 50 mM TrisSO4 pH 8.0, 2.5 mM MgSO4. F1 was purified as described in [29]. Before experiments, F1 samples (100µl) were also passed twice through 1-ml centrifuge columns (Sephadex G-50) equilibrated in 50mM TrisSO4 pH 8.0, to remove catalytic site bound-nucleotide. ATPase activity was measured in 1 ml assay buffer containing 10 mM NaATP, 4 mM MgCl2, and 50 mM TrisSO4, at pH 8.5 and 37 °C. Reactions were started by addition of 1 ml assay buffer to the purified F1 or membranes and stopped by addition of SDS to 3.3% final concentration. Pi released was assayed as in [30]. For membranes (30 – 50 µg protein), reaction times were 20–30 min. For purified F1 (20 µg protein), reaction times were 2–5 min. All reactions were shown to be linear with time and protein concentration. SDS-gel electrophoresis on 10% acrylamide gels was as in [31]. Immunoblotting with rabbit polyclonal anti-F1-α and anti-F1-β antibodies was as in [32].

Source of peptides and other chemicals

Amphibian peptides dermaseptin (D4671-.5MG), magainin II (M7402-1 MG), magainin II-amide (M8155-1MG), and melittin (M4171-1MG), honey bee venom peptide were purchased from Sigma Chemical Company. Other amphibian antimicrobial peptides, ascaphin-8, aurein 2.2, aurein 2.3, caerin 1.8, caerin 1.9, citropin 1.1, dermaseptin, maculatin 1.1, MRP (melittin-related peptide, also called AR-23), MRP-amide, XT-7, and honey bee venom peptides melittin and melittin-amide, were custom ordered from Biomatik (http://www.biomatik.com). All amphibian antimicrobial peptides from Biomatik were greater than 95% pure as measured by HPLC. They were received as lyophilized powder shipped on dry ice, immediately kept at −20°C and resuspended in autoclaved deionized water as needed. All other chemicals used in this study were ultra pure analytical grade purchased either from Sigma –Aldrich Chemical Company or Fisher Scientific Company.

Inhibition of ATPase activity by amphibian antimicrobial peptides, or honey bee venom peptide melittin / melittin-amide

Membrane bound ATP synthase or purified F1 (0.2–1.0 mg/ml) were preincubated with varied concentrations of ascaphin-8, aurein 2.2, aurein 2.3, caerin 1.8, caerin 1.9, citropin 1.1, dermaseptin, maculatin 1.1, magainin II, magainin II-amide, MRP, XT-7 melittin, or melittin-amide for 60 min at room temperature, in 50 mM TrisSO4 pH 8.0. The volume of peptides added was in the ranged from 0–35µl in a total reaction volume of 1050µl. Then 1 ml ATPase assay buffer was added to measure the activity. Inhibitory exponential decay curves were generated using SigmaPlot 10.0. The best fit lines and IC50 values for the curves were obtained using a single 3 parameter model. The range of absolute specific activity for membrane bound F1Fo was 18–24 and for purified F1 was 28–38 µmol/min/mg at 37 °C for different preparations. These absolute values were used as 100% bench mark to calculate the relative ATPase activity.

Reversal of purified F1 or membrane bound enzyme ATPase activity from peptide inhibition

Reversibility of inhibition was assayed by dilution of the membrane enzyme or by passing the inhibited purified F1 through centrifuge columns. Membranes were first incubated with inhibitory concentrations of peptides for 1 hour at room temperature. The concentrations used were based on the maximal inhibition of ATP synthase (see Fig. 2–4). Then 50 mM TrisSO4 pH 8.0 buffer was added to decrease the concentrations to noninhibitory levels and incubation continued for 1 additional hour at room temperature before ATPase assay. Reversibility was also tested by passing the peptide inhibited purified F1 enzyme twice through 1 ml centrifuge columns before measuring the ATPase activity. Control samples without peptides were also incubated for the same time periods as the samples with peptides. Two consecutive passages through centrifuge columns were previously found to decrease the concentration of small molecules bound to ATP synthase and other proteins to non-detectable levels. Thus, after passage through centrifuge columns, reactivation is likely a first-order kinetic process that is a function of the release of bound inhibitor.

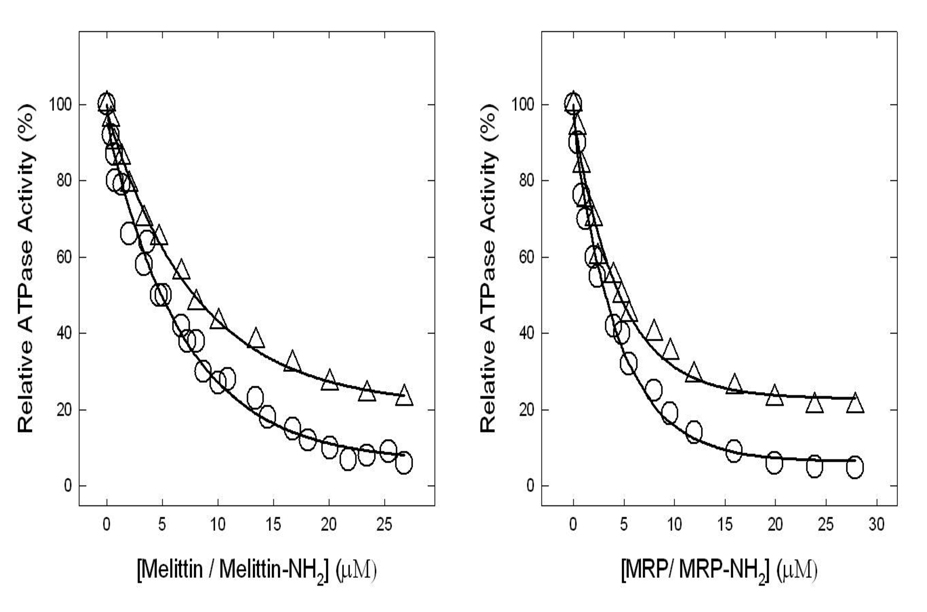

Figure 2. Inhibition of ATPase activity in purified F1 or membrane-bound ATP synthase by melittin, melittin-amide, MRP, MRP-amide.

Membranes or purified F1 were preincubated for 60 min at 23°C with varied concentration of melittin, melittin-amide, MRP, MRP-amide, and then 1 ml of assay buffer was added and ATPase activity determined. Details are given in Materials and Methods. Symbols used are: circles (○, melittin –amide and Δ, melittin), triangles (○, MRP-amide and Δ, MRP). Each data point represents average of at least four experiments done in duplicate tubes, using two independent membrane or F1 preparations. Results agreed within ± 10%.

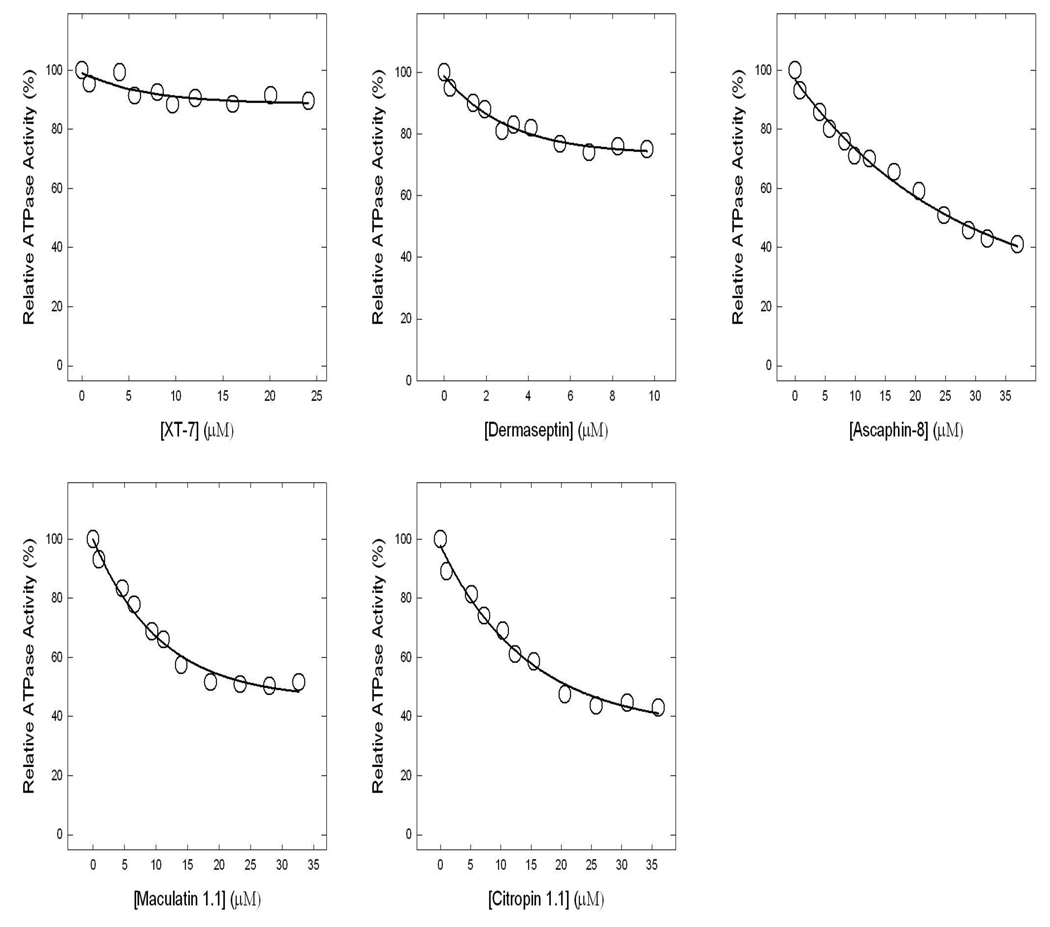

Figure 4. Inhibition of ATPase activity in purified F1 or membrane-bound ATP synthase by ascaphin-8, citropin 1.1, dermaseptin, maculatin 1.1, or XT-7.

Purified F1 or membranes were preincubated for 60 min at 23°C with varied concentration of ascaphin-8, citropin 1.1, dermaseptin, maculatin 1.1, or XT-7 and then 1ml of assay buffer was added and ATPase activity determined. Details are given in Materials and Methods. Each data point represents average of at least four experiments done in duplicate tubes, using two independent membrane or F1 preparations. Results agreed within ± 10%.

Results

Inhibition of ATPase activity of purified F1 and F1Fo ATP synthase in membranes by melittin, melittin-amide, MRP, or MRP-amide

Figure 2 shows the inhibition of ATPase activity of purified F1 or membrane bound enzyme in the presence of varied concentrations of melittin, melittin-amide, MRP, or MRPamide. Melittin or melittin–amide inhibited ~77% (IC50 ~7.84 µM, R = 0.9985) or ~95% (IC50 ~4.68 µM, R = 0.9944), while MRP or MRP-amide inhibited ~79% (IC50 ~4.77 µM, R = 0.9937) or ~96% (IC50 ~3.25 µM, R = 0.9957). We consistently found that the purified F1 data and the membrane bound ATP synthase data were the same for both these and other peptide inhibitors. This is in agreement with our previously established interpretation that inhibition of ATPase activity can be assayed using either membrane preparations or purified F1 with equivalent results [33–37].

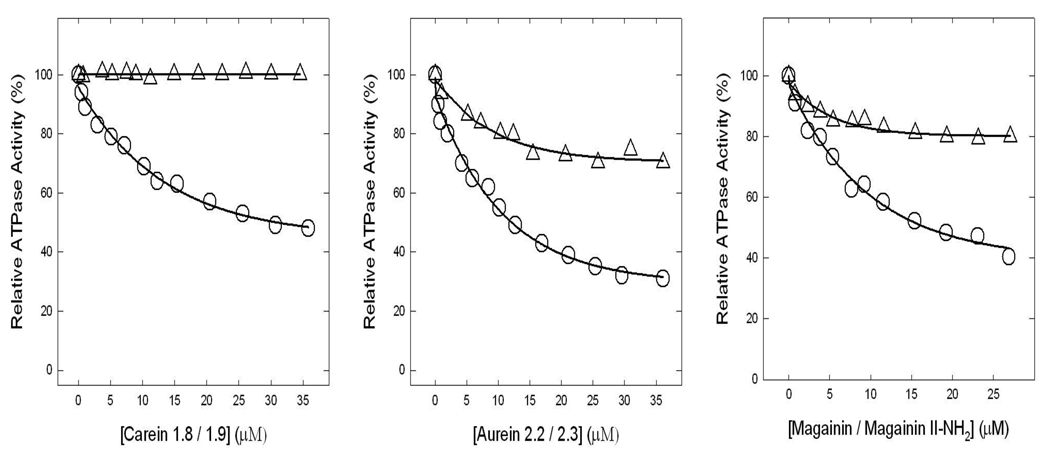

Inhibitory effect of amphibian AMPs aurein 2.2, aurein 2.3, carein 1.8, carein 1.9, magainin II, or magainin II-amide on the purified F1 or membrane bound enzyme

Figure 3 shows the inhibitory effect of amphibian AMPs aurein 2.2, aurein 2.3, carein 1.8, carein 1.9, magainin II, or magainin II-amide. While carein 1.8 did not inhibit at all (0% inhibition) others beget partial inhibition with aurein 2.2 (~69%), aurein 2.3 (~30%), carein 1.9 (~52%), magainin II (~20%), or magainin II-amide (~60%). Again the F1 data and the membrane data were same for all inhibitors.

Figure 3. Inhibition of ATPase activity in purified F1 or membrane-bound ATP synthase by aurein 2.2, aurein 2.3, carein 1.8, carein 1.9, magaininII, or magainin II-amide.

Purified F1 or membranes were preincubated for 60 min at 23°C with varied concentration of aurein 2.2 (○), aurein 2.3 (Δ), carein 1.8 (Δ), carein 1.9 (○), magaininII (Δ), or magainin II-amide (○) and then 1 ml of assay buffer was added and ATPase activity determined. Details are given in Materials and Methods. Each data point represents average of at least four experiments done in duplicate tubes, using two independent membrane or F1 preparations. Results agreed within ± 10%.

Inhibitory effect of amphibian AMPs ascaphin-8, citropin 1.1, dermaseptin, maculatin 1.1, or XT-7 on the purified F1 or membrane bound enzyme

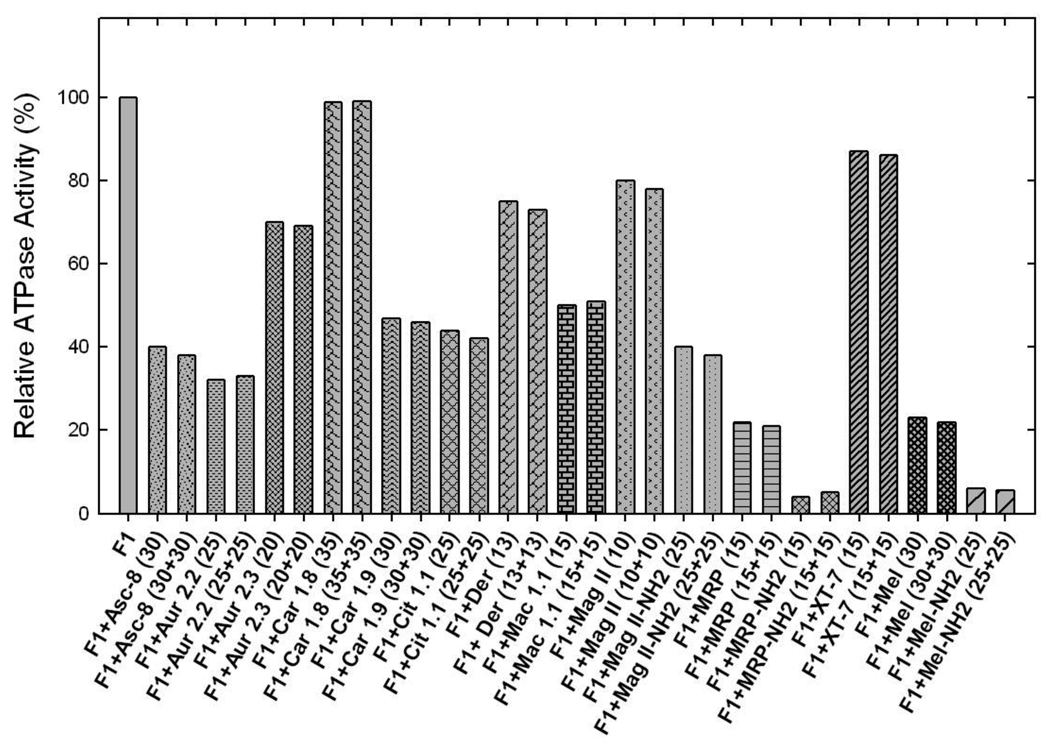

Amphibian AMPs ascaphin-8, citropin 1.1, dermaseptin, maculatin 1.1, or XT-7 induced partial inhibition with the following residual activities: ascaphin-8 (~41%), citropin 1.1 (~43%), dermaseptin (~74%), maculatin 1.1 (~52%), or XT-7 (~87%) (See Fig. 4, Table 2). Partial inhibition of ATP synthase is not uncommon. In previous studies [12, 33–40], we have noted several instances where wild-type or mutant E. coli ATP synthase was incompletely inhibited by potent inhibitors like fluoroaluminate, fluoroscandium, sodium azide, NBD-Cl or by polyphenols like resveratrol, quercetrin, or quercetin-3-βglucoside. To ensure that the maximal inhibition with amphibian AMPs had been reached, we incubated each membrane preparation or purified F1 with ascaphin-8 (30µM), aurein 2.2 (25µM), aurein 2.3 (20µM), carein 1.8 (35µM), carein 1.9 (30µM), citropin 1.1 (25µM), dermaseptin (13µm), maculatin 1.1 (15 µM), magainin II (10µM), magainin II-amide (25µM), MRP (15µM), MRP-amide (15µM), XT-7 (15µM), melittin (30µM), or melittin-NH2 (25µM), by the maximal inhibitory concentrations, for 1 h as in Figure 2–4. This was followed by supplementary pulses of the same inhibitory peptide concentrations and incubation was continued for an additional hour before ATPase assay. As shown in Figure 5 very little or no additional inhibition occurred consistent with Figure 2–4 data. This shows that the inhibition by amphibian AMPs could reach a maximal value, and yet residual activity could be retained in many cases

Table 2.

Growth of E. coli and inhibition of ATPase activity in presence of amphibian Antimicrobial peptides and melittin

| Peptide |

a Growth on Succinate plates |

b Growth yield on limiting glucose (%) |

c ATPase inhibition (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| dWild type | ++++ | 100 | N/A |

| eNull | − | 41 | N/A |

| Ascaphin-8 | + | 10 | 59 |

| Aurein 2.2 | + | 12 | 69 |

| Aurein 2.3 | ++ | 24 | 30 |

| Caerin 1.8 | ++++ | 99 | 0 |

| Caerin 1.9 | ++ | 34 | 52 |

| Citropin 1.1 | ++ | 23 | 57 |

| Dermaseptin | ++ | 34 | 26 |

| Maculatin1.1 | ++++ | 92 | 48 |

| Magainin II | +++ | 96 | 20 |

| Magainin II-NH2 | + | 21 | 60 |

| MRP | + | 11 | 80 |

| MRP-NH2 | − | 2 | 96 |

| XT-7 | ++++ | 89 | 13 |

| Melittin | + | 8 | 77 |

| Melittin-NH2 | − | 1 | 94 |

Growth on succinate plates after 3 days was determined by visual inspection. ++++, high growth; +++, moderate growth; ++ low growth; +, minimal; −, no growth.

Growth yield on limiting glucose was measured as OD595 after ~20 hours growth at 37 °C.

ATPase inhibirion is the percent inhibition in presence of peptides.

Control, pBWU13.4/DK8 which contains UNC+ gene encoding ATP synthase; Null, pUC118/DK8 with UNC− gene. Growth of wild-type and Null in absence of peptides. Data are means of four to six experiments each at 37 °C. Each individual experimental point is itself the mean of duplicate assays.

Figure 5. Results of Extra pulse of peptides on purified F1 or membrane bound ATP synthase.

Membrane bound ATP synthase (Mbr) or purified F1 (F1) was inhibited with inhibitory concentrations of amphibian peptides or melittin for 60 min under conditions as described in Fig 2–4. Then a further pulse of identical inhibitory concentrations was added and incubation continued for 1 h before assay. The last digits represent the peptide concentrations in [µM].

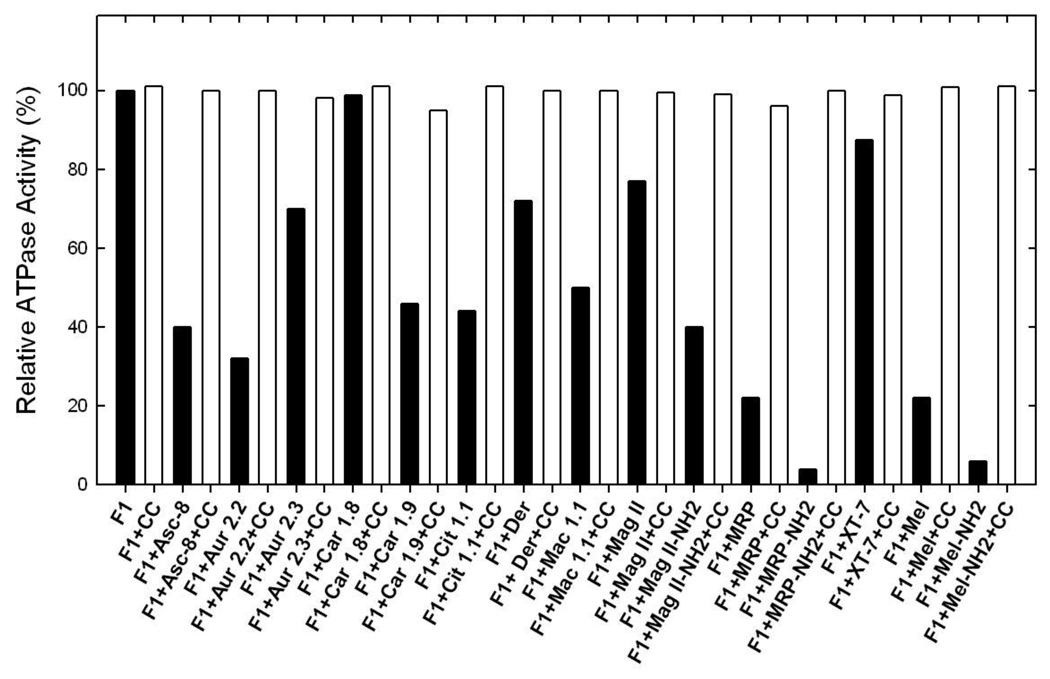

Reversal of ATPase activity of purified F1 or membrane bound enzyme from the peptide inhibition

Here we examined whether the peptide induced inhibition of ATPase is reversible or not. Reversibility data is shown in Figure 6. This experiment was carried out in two ways. (i) the purified F1 or membrane bound enzyme was inhibited with the maximum inhibitory concentrations of peptides for 1 hr at RT as in figure 2–figure 4. Samples were then diluted to a non-inhibitory concentration and ATPase activity was measured. (ii) 20 µg of purified F1 samples were inhibited with maximum inhibitory concentrations of peptides for 1 hr at RT. As before the inhibitory concentrations were determined based on data from figure 2–figure 4. Inhibited samples were then passed twice through 1 ml centrifuge columns and ATPase activity measured. Inhibition by both melittin and amphibian AMPs was found to be fully reversible.

Effect of peptides on the growth of E. coli cells in LB and limiting glucose media

Inhibitory effects on ATP synthesis were studied by growing the wild-type E. coli strain pBWU13.4/DK on succinate plates, limiting glucose, or LB media in the presence or absence of peptides (Table 2). While there was no growth in presence of melittin, melittin-amide, MRP, MRP-amide, magainin II-amide, dermaseptin, citropin 1.1, aurein 2.2, aurein 2.3, or ascaphin-8, the cells grew well in presence of carein 1.8, carein 1.9, maculatin 1.1, magainin II, or XT-7. Four peptides, melittin, melittin-amide, MRP, or MRP-amide show strongest inhibition of F1-ATPase as well as cell growth. Three peptides: carein 1.8, magainin II, and XT-7, show the least amount of inhibition of both ATPase and cell growth. Ascaphin-8, aurein 2.2, aurein 2.3, carein 1.9, citropin 1.1, dermaseptin, and magainin II-NH2, partially inhibited ATPase activity and inhibited cell growth in limiting glucose and on succinate plates. Interestingly maculatin 1.1 partially inhibited F1-ATPase without an observed effect on cell growth. other peptides tested in this study show abrogation of both gylcolytic and oxidative phosphorylation pathways (Table 1).

Discussion

The goal of this study was to examine the inhibitory effects of amphibian AMPs on ATP synthase. Previously, it was shown that a number of α helical amphiphlic peptides, including honey bee venom peptide melittin, inhibit F1-ATPase [18]. Also, inhibition of ATP synthase by compounds such as resveratrol, quercetin, or piceatannol suggests that the beneficial effects of dietary polyphenols may be in part linked to the blocking of ATP synthesis in tumor cells, thereby leading to apoptosis [16, 33].

It is noteworthy that the amphibian peptide MRP or MRP-amide were as potent on molar scale as melittin or melittin-amide, the previously known honey bee peptide inhibitor of ATPase. Melittin or melittin-amide, resulted in ~78% or 94% inhibition (IC50 ~7.84 or ~4.68 µM) respectively. MRP or MRP-amide resulted in ~80% or ~96% inhibition (IC50 ~4.77µM or ~3.25µM) respectively. Also, amide moieties at the c-terminal of melittin or MRP caused ~17% or 16% additional inhibition respectively. For example, melittin-amide or MRP-amide caused augmented inhibition of ~94% or 96% respectively (IC50 ~4.68 µM or 3.25µM), while melittin or MRP, lacking a c-terminal amide moiety, resulted in ~78% or 80% inhibition respectively (IC50 ~7.84 µM or 4.77µM). Apparently, the presence of a c-terminal amide (NH2) enhances the inhibitory effects by peptides (Fig.2). This enhanced inhibition may be the result better binding between the negatively charged βDELSEED motif residues and peptides having additional positive charge from an amide group.

The F1 sector β-subunit residues 394–400 (βDELSEED-loop) was identified as the site of binding and inhibition for several peptide inhibitors. Quinacrine mustard a potent inhibitor of F1-ATPase was shown to bind at the βDELSEED motif with an apparent kd value of 27 µM [41]. The βDELSEED sequence also resembles the negatively charged residue sequence EEEIRE of calmodulin, where cationic phenothiazine [42–43] or melittin interact [44]. Hence, the partial protection against the inhibition of F1-ATPase from quinacrine mustard by melittin, SynA2, or SynC, in proportion to their inhibitory capabilities, is suggestive of a common βDELSEED binding site on F1-sector of ATP synthase for these peptides (see figure 1). It was also found that the ε-subunit, an intrinsic inhibitor of F1-ATPase, exerts its inhibitory effect through the electrostatic interactions with the DELSEED motif of the β-subunit [20]. Therefore, we propose that electrostatic interactions between the α-helical basic amphibian AMPs and the acidic residues of the βDELSEED motif may be responsible for inhibition of E. coli ATP synthase.

Our results demonstrated variable inhibition of E. coli ATP synthase by amphibian AMPs (Fig. 2–4). Eleven other amphibian AMPs used in this study caused ~0–70% inhibition. The observed variability in the degree of inhibition among amphibian AMPs can be explained in terms of changes in residue charge, size, or position (Fig. 3, Table 1). Presence of Leu-13 (aurein 2.2) instead of Ile-13 (aurein 2.3) in the 16-residue long aurein peptide results in ~40% more inhibition. Carein 1.8 with Lys-4, Val-9, and Leu-13 causes ~0% inhibition, while carein 1.9 with Gly-4, Ile-9, and Val-13 results in ~52% inhibition. Carein 1.8 with 4 net positive charges compared to carein 1.9 with 3 net positive charges would have been expected to be a better inhibitor. Experimental results are quite contrary to this expectation (Figure 3). Presently we have no convincing explanation for this outcome, but steric hindrance and /or repulsion between the Leu residue of βDELSEED and Leu-13 of carein 1.8 are a possibility. Future mutagenic analysis of βDELSEED motif may help answer this question. Again, presence of an amide group at the c-terminal of maganin II-amide resulted in ~40% higher inhibition than that of magainin II (Fig.3). The observed differences in the degree of inhibition among the other five amphibian AMPs in Figure 4 can also be attributed to variation in their primary sequence resulting in divergent amphipathic α-helical folds [18, 45].

For those peptides which resulted in partial inhibition (~31– 87%, Table 2), addition of an extra pulse of peptides to the previously inhibited purified F1 or membrane bound F1Fo did not change the degree of inhibition significantly (Fig. 5). This suggests that the purified F1 or membrane bound enzyme were fully inhibited by the peptides and the extent of observed inhibition was accurate. In addition, partial inhibition is not the result of uninhibited enzyme or degradation of the peptides over time. The process of inhibition was also found to be completely reversible. Inhibited F1 regained activity after being passed twice through the centrifuge columns to remove the peptides (Fig. 6). Likewise purified F1 or membrane bound enzyme regained activity once returned to lower noninhibitory concentrations of peptides by dilution with buffer after exposing them to higher concentrations (Fig. 6). The process of reversibility is an indication of noncovalent binding of peptides [15, 18].

Figure 6.

Results of reversal of inhibition by passing through centrifuge columns purified F1 (F1) was inhibited with inhibitory concentrations of the peptides shown in the figure for 60 min under conditions as described in Fig 2–4. Then the inhibited samples were passed twice through 1 ml centrifuge columns and ATPase activity was measured. Identical reversibility results were obtained by diluting the inhibited membrane bound enzyme or purified F1. For clarity, only the data for reversibility by centrifuge columns is shown.

Another interesting result is the growth patterns of E. coli cells observed in the presence of amphibian AMPs (Table 2). It was found that some amphibian AMPs like ascaphin-8, aurein 2.2, aurein 2.3, carein 1.9, citropin 1.1 dermaseptin, maganin II-amide, MRP, MRP-amide, melittin, or melittin-amide abrogated growth. On the other hand carein 1.8, maculatin 1.1, magainin II, or XT-7 did not affect growth of cells. Our null strain (pUC118/DK8) usually will grow 40–50% of the wild-type (pBWU13.4/DK). This is because the null strain uses only glycolysis to generate ATP whereas the wild-type uses both gyolysis and oxidative phosphorylation. Melittin, melittin-amide, MRP, or MRP-amide strongly inhibit both F1-ATPase as well as cell growth. While carein 1.8, magainin II, and XT-7, show the least amount of inhibition of both ATPase and cell growth. Ascaphin-8, aurein 2.2, aurein 2.3, carein 1.9, citropin 1.1, dermaseptin, and magainin II-NH2, partially inhibited ATPase activity and inhibited cell growth in limiting glucose and on succinate plates. On the other hand maculatin 1.1 partially inhibited F1-ATPase without an observed effect on cell growth. Other peptides tested in this study show abrogation of both gylcolytic and oxidative phosphorylation pathways (Table 1). Apparently some peptides inhibit glycolysis in addition to oxidative phosphorylation, and some do not inhibit growth at all. There is not consistent pattern of inhibitory effects by these peptides other than increased inhibition by the presence of a c-terminal amide group. This result is consistent with previously observed effects of polyphenols on both E. coli and bovine ATP synthase [16, 33]. However, the following arguments cannot be ruled out at this time: (a) peptide penetration into the cells was variable, (b) some peptides were removed by an export pump, (c) some peptides were degraded by the bacterial cells, or (d) residue level steric hindrances or ionic/hydrophobic interactions occurred between peptides and βDELSEED motif. Further inhibitory studies with additional and/or modified peptides along with mutagenic analysis of βDELSEED motif should help in understanding these results.

Peptides are an indispensable part of natural defense mechanisms for many plants, animals and microorganisms. Both natural and synthetic AMPs are important antimicrobial agents. AMPs are mainly cationic, and amphipathic molecules ranging from 10 to 50 amino acid residues long which show broad spectrum of activity against bacteria and fungi [46]. Previous studies have proposed that the mode of action for AMPs is through their interaction with negatively charged bacterial cell membranes [45, 47–48]. Our results demonstrate that amphibian antimicrobial peptides inhibit F1Fo ATP synthase. This inhibition is likely to occur via binding of these peptides to the βDELSEED motif. Further investigation through mutagenic analysis of βDELSEED in presence of peptides will be helpful in understanding the inhibitory mechanism.

Recently ATP synthase has been identified on the surface of multiple animal cell types other than the membranes of mitochondria, bacteria, and chloroplast. The new found role of ATP synthase as a receptor for ligands and other cellular processes including angiogenesis, lipid metabolism, and cytolytic pathways of tumor cells, in addition to ATP hydrolysis or synthesis, has emphasized its potential as a pathway to the treatment of many human diseases [15]. The results of this study clearly show that amphibian AMPs bind and inhibit bacterial ATP synthase maximally or partially. This suggests a possible link between antimicrobial/ anticancer properties of amphibian skin peptides and their inhibition of ATP synthase.

As the role of ATP synthase is becoming clear in the pathopysiology of many human disorders, so the inhibitors of ectopic ATP synthase become an increasingly attractive potential source of therapeutic strategies [17]. Hence, the need to identify and characterize potent inhibitors of ATP synthase (natural or synthetic) is of paramount importance.

Acknowledgement

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health Grant GM GM085771 to ZA and ETSU Small RDC Grant 211506 to ZA and TL. We are grateful to Dr. Alan Senior, Professor Emeritus, Department of Biochemistry & Biophysics, University of Rochester Medical Center, Rochester, NY for his comments on the manuscript.

Abbreviations used

- Mbr

membrane containing ATP synthase

- F1

purified F1-ATPase

- AMP

antimicrobial peptide

- MRP

melittin-related peptide; IC50 corresponds to the concentration of inhibitor where 50% of maximal inhibition was observed.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

E. coli residue numbers used throughout.

References

- 1.Abrahams JP, Leslie AGW, Lutter R, Walker JE. Nature. 1994;370:621–628. doi: 10.1038/370621a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Senior AE, Nadanaciva S, Weber J. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2002;1553:188–211. doi: 10.1016/s0005-2728(02)00185-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Noji H, Yasuda R, Yoshida M, Kinosita K., Jr Nature. 1997;386:299–302. doi: 10.1038/386299a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Diez M, Zimmermann B, Borsch M, Konig M, Schweinberger E, Steigmiller S, Reuter R, Felekyan S, Kudryavtsev V, Seidel CAM, Graber P. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2004;11:135–141. doi: 10.1038/nsmb718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Itoh H, Takahashi A, Adachi K, Noji H, Yasuda R, Yoshida M, Kinosita K. Nature. 2004;427:465–468. doi: 10.1038/nature02212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Senior AE. Cell. 2007;130:220–221. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pedersen PL. J Bioenerg Biomembr. 2007;39:349–355. doi: 10.1007/s10863-007-9123-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Noji H, Yoshida M. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:1665–1668. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R000021200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Weber J, Senior AE. FEBS Lett. 2003;545:61–70. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(03)00394-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Frasch WD. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2000;1458:310–325. doi: 10.1016/s0005-2728(00)00083-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ren H, Allison WS. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2000;1458:221–233. doi: 10.1016/s0005-2728(00)00075-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ahmad Z, Senior AE. J Bioenerg Biomembr. 2005;37:437–440. doi: 10.1007/s10863-005-9486-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kabaleeswaran V, Puri N, Walker JE, Leslie AG, Mueller DM. EMBO J. 2006;25:5433–5442. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.de Vries DD, van Engelen BG, Gabreels FJ, Ruitenbeek W, van Oost BA. Ann Neurol. 1993;34:410–412. doi: 10.1002/ana.410340319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hong S, Pedersen PL. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 2008;72:590–641. doi: 10.1128/MMBR.00016-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gledhill JR, Montgomery MG, Leslie AG, Walker JE. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:13632–13637. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0706290104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gledhill JR, Walker JE. Biochem J. 2005;386:591–598. doi: 10.1042/BJ20041513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bullough DA, Ceccarelli EA, Roise D, Allison WS. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1989;975:377–383. doi: 10.1016/s0005-2728(89)80346-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kato-Yamada Y, Bald D, Koike M, Motohashi K, Hisabori T, Yoshida M. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:33991–33994. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.48.33991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hara KY, Kato-Yamada Y, Kikuchi Y, Hisabori T, Yoshida M. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:23969–23973. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M009303200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Boman HG, Nilsson I, Rasmuson B. Nature. 1972;237:232–235. doi: 10.1038/237232a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hultmark D, Steiner H, Rasmuson T, Boman HG. Eur J Biochem. 1980;106:7–16. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1980.tb05991.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Steiner H, Hultmark D, Engstrom A, Bennich H, Boman HG. Nature. 1981;292:246–248. doi: 10.1038/292246a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jakubke H-D, Sewald N. Peptides from A to Z : a concise encyclopedia. Weinheim: Wiley-VCH; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wang Z, Wang G. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004;32:D590–D592. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkh025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ketchum CJ, Al-Shawi MK, Nakamoto RK. Biochem. J. 1998;330:707–712. doi: 10.1042/bj3300707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Senior AE, Latchney LR, Ferguson AM, Wise JG. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1984;228:49–53. doi: 10.1016/0003-9861(84)90045-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Senior AE, Langman L, Cox GB, Gibson F. Biochem. J. 1983;210:395–403. doi: 10.1042/bj2100395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Weber J, Lee RS, Grell E, Wise JG, Senior AE. J Biol Chem. 1992;267:1712–1718. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Taussky HH, Shorr E. J Biol Chem. 1953;202:675–685. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Laemmli UK. Nature. 1970;227:680–685. doi: 10.1038/227680a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rao R, Perlin DS, Senior AE. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1987;255:309–315. doi: 10.1016/0003-9861(87)90398-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Dadi PK, Ahmad M, Ahmad Z. Int J Biol Macromol. 2009;45:72–79. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2009.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ahmad Z, Senior AE. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:31505–31513. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M404621200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ahmad Z, Senior AE. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:27981–27989. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M503955200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Brudecki LE, Grindstaff JJ, Ahmad Z. Arch Biochem Biophys. 2008;471:168–175. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2008.01.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Li W, Brudecki LE, Senior AE, Ahmad Z. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:10747–10754. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M809209200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ahmad Z, Senior AE. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:46057–46064. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M407608200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ahmad Z, Senior AE. FEBS Lett. 2005;579:523–528. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2004.12.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ahmad Z, Senior AE. FEBS Lett. 2006;580:517–520. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2005.12.057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bullough DA, Ceccarelli EA, Verburg JG, Allison WS. J Biol Chem. 1989;264:9155–9163. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Strynadka NC, James MN. Proteins. 1988;3:1–17. doi: 10.1002/prot.340030102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Gresh N, Pullman B. Mol Pharmacol. 1986;29:355–362. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Malencik DA, Anderson SR. Biochemistry. 1984;23:2420–2428. doi: 10.1021/bi00306a016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Almeida PF, Pokorny A. Biochemistry. 2009;48:8083–8093. doi: 10.1021/bi900914g. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.McCoy AJ, Liu H, Falla TJ, Gunn JS. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2001;45:2030–2037. doi: 10.1128/AAC.45.7.2030-2037.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Conlon JM, Ahmed E, Coquet L, Jouenne T, Leprince J, Vaudry H, King JD. Toxicon. 2009;53:699–705. doi: 10.1016/j.toxicon.2009.02.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Conlon JM, Al-Ghaferi N, Abraham B, Leprince J. Methods. 2007;42:349–357. doi: 10.1016/j.ymeth.2007.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Menz RI, Walker JE, Leslie AG. Cell. 2001;106:331–341. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(01)00452-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Anderson D, Terwilliger TC, Wickner W, Eisenberg D. J Biol Chem. 1980;255:2578–2582. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Gesell J, Zasloff M, Opella SJ. J Biomol NMR. 1997;9:127–135. doi: 10.1023/a:1018698002314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]