CD8+ cytotoxic T lymphocytes (CTLs) provide defense against intracellular pathogens and tumors by recognizing and subsequently destroying infected or transformed cells. Recognition is achieved by T cell receptors (TCRs) on the CTL binding to non-self-peptide fragments presented in the cleft of class I MHC molecules (peptide–MHC complexes) on the surface of the target cell. TCR ligation triggers target cell destruction by the CTL through several mechanisms, including the delivery to target cells of a pore-forming protein that penetrate the target cell membrane (perforin) and specialized proteases (granzymes). It has been known for some time that the density of peptide–MHC (pMHC) complexes on the surface of target cells required to stimulate cytotoxic functions in CTLs is dramatically lower than that required to stimulate cytokine production and clonal expansion: very few agonist pMHC complexes, perhaps even a single one per target cell, can elicit measurable cytotoxic function at the population level (1, 2). In contrast, production of cytokines such as IFN-γ (which trigger effector functions in immune cells) and clonal expansion of CTLs require the presence of 100- to 1,000-fold more complexes (3). Separate thresholds for these biological responses fit within the context of CTL function: effector CD8+ T cells need to kill infected cells in response to the lowest possible level of foreign peptides to control infections at their early stages, but the immune system must also carefully control this potent cell population to avoid destruction of healthy tissue. Thus, cytokine production and proliferation likely occur only under conditions of high pMHC complex density, typically with delivery of costimulatory signals that in vivo will be provided by professional antigen-presenting cells (APCs). Although the phenomenon of dual antigen-density thresholds for CTL responses is well established at the population level, the mechanism behind these dual programs of function at the cellular level has remained unknown.

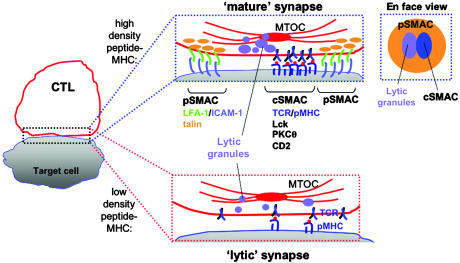

In this issue of PNAS, Faroudi et al. (4) now provide evidence that this duality may be at least in part controlled through the selective accumulation of signaling and adhesion proteins formed at the interface between lymphocytes and their partner APCs, which is known as the immunological synapse (IS) (Fig. 1). Since the first publications described the IS structure for CD4+ T cells (5, 6), the synapse has been the subject of intensive study aimed at characterizing the molecules involved in T cell activation and their dynamics during antigen recognition. The mature synapse structure observed when CD4+ T cells are activated by high densities of peptide–MHC complexes is characterized by a bulls-eye-like central accumulation of T cell receptors and other signaling molecules known as the central supramolecular activation cluster (cSMAC). The cSMAC is corralled by a ring of adhesion molecules in a second region known as the peripheral SMAC (pSMAC). Strikingly, the IS structure appears to result from clustering specific molecules (as opposed to a general aggregation of membrane proteins), because fluorescence labeling has revealed that molecules not involved in activation are generally found in unperturbed, uniform distributions on the T cell surface, even in the interface (5, 7, 8). A similar overall IS structure was discovered in the interface between CTLs and their target cells, with the exception being that the cSMAC shares space with secretory granules (containing perforin and granzymes) that accumulate at the interface to deliver the cell's killer function (Fig. 1 and refs. 9 and 10).

Fig. 1.

Assembly of molecules at the CTL–target cell interface. (Left) A simplified schematic of the mature IS formed by CD8+ T cells, showing the central region occupied by both an accumulation of lytic granules and the cSMAC. This central core of signaling and effector molecules is surrounded by adhesion molecules localized to the pSMAC. At low antigen densities sufficient for target cell lysis but insufficient for cytokine production or proliferation, Faroudi et al. (4) now report a minimal lytic synapse formed by recruitment of components required for cell lysis but lacking features present in the mature IS.

The density of pMHC complexes on the surface of APCs can be experimentally varied by incubating the cells for short time periods (pulsing) with different concentrations of the agonist peptide. Whereas the synapse structure formed in response to maximal pMHC densities has been extensively characterized, fewer reports have examined variations in the structure of the synapse with peptide density. Studies in CD4+ and CD8+ T cells have shown that formation of the mature IS structure correlates with the onset of proliferation and cytokine production in these cells (6, 8, 10). However, CTLs can exhibit maximal cytotoxicity in response to target cells pulsed with 100- to 1,000-fold less antigen (pMHC) than is required for cytokine production, and the accumulation of signaling proteins at the CTL–target cell interface when the triggering pMHC complexes are scarce has not been examined. Faroudi et al. (4) have now compared the response of CTLs to a very low pMHC density that promotes maximal cytotoxicity (peptide–MHC complexes generated by incubating target cells with 1 nM peptide), to that observed at a very high pMHC density (target cells pulsed with 10 μM peptide) that promotes full cytokine production, and found significant differences in the accumulation of molecules at the T cell–target cell interface under these two conditions. They found that CTLs still assemble some (but not all) of the components of their IS in response to the very low number of pMHC complexes formed by pulsing target cells with the low peptide concentration. Under these conditions, CTLs polarized the microtubule-organizing center (MTOC) and perforin to the cell–cell interface with frequencies comparable to CTLs contacting targets pulsed with the 10,000-fold higher peptide concentration. In addition, lytic granules were accumulated at the interface in response to this low pMHC complex density, although not as strongly as at the higher peptide concentration. These results would be expected, given that cytotoxic function is fully triggered even at these low antigen densities. Interestingly, however, Faroudi et al. (4) also found that at low peptide-MHC levels, the adhesion receptor CD2 and phosphotyrosine were weakly accumulated at the interface or not at all (as in controls where target cells lacked specific peptide–MHC complexes), whereas at high peptide concentrations, CD2 and phosphotyrosine were strongly clustered at the T-APC contact zone as part of the mature IS structure. CD2 is believed to play a role in stabilizing the close contact between the two cells, facilitating TCR binding to pMHC complexes, whereas phosphotyrosine is a signature of activated signaling molecules, which may dock additional components of the T cell signaling machinery. Thus, CTLs selectively polarized components required for target cell lysis in response to minimal peptide levels, whereas signal-stabilizing components of the mature IS were only assembled in response to higher pMHC densities.

In addition to differences in the IS formed at the T cell–target cell interface, Faroudi et al. (4) also found differences in the nature of calcium signals elicited in CTLs responding to low vs. high antigen concentrations. Release of calcium from intracellular stores and subsequent influx of extracellular calcium into the cytosol are two of the earliest events triggered by TCR ligation, and they can be sustained for hours to regulate gene expression in T cells (11, 12). Faroudi et al. (4) found that calcium signaling under lytic (low) pMHC complex densities in single CD8+ T cells exhibited a different pattern, qualitatively and quantitatively, from the response at high antigen densities. Examining the magnitude and shape of intracellular calcium concentration vs. time, they found that high antigen levels promoted smooth calcium fluxes which decayed slowly, whereas calcium signaling in response to low antigen density showed a spiky behavior with lower mean calcium levels. Whereas the quantitative outcome of different calcium signaling patterns in T cells is not yet well understood, it is known that at the level of gene expression programs, different transcription factors are sensitive to the pattern of calcium signaling (11, 13). For example, at low levels of stimulation, oscillatory calcium signaling is believed to be more efficient than a sustained plateau in intracellular calcium of the same average concentration for activation of the transcription factor nuclear factor of activated T cells (NFAT) (11); thus CTLs may use oscillatory signaling to enhance their responsiveness to low densities of foreign antigen. Calcium signals are also implicated in more rapid responses, such as the delivery of the stop signal that arrests migrating T cells on contact with antigen and permits sustained interactions with the APC (11). Thus, while it is unclear as to which of the differences observed in the calcium signal at low vs. high peptide-MHC densities is critical (spikiness or mean calcium concentration), these differences in signaling are likely to have a functional role in dictating the different CTL responses.

The observations made by Faroudi et al. (4) lead them to suggest that the selective assembly of components at the immunological synapse may control the program of subsequent CTL functions. At high antigen densities, recruitment of molecules like CD2 involved in the assembly of the mature synapse structure would promote sustained signaling, and presumably provide the smooth calcium signaling observed. In contrast, at low antigen density, a spare lytic synapse structure might be specifically assembled by hypersensitive recruitment of the MTOC and secretory apparatus to the interface in response to minimal TCR signals, as illustrated in Fig. 1. A spiky calcium signal might then directly result from the lack of assembly of the mature synapse and its accompanying accumulation of signal–stabilizing interactions. CTLs can deliver a fatal hit to target cells within 5 min, and, thus, once the secretory apparatus is positioned at the interface, only minimal TCR signaling may be needed for target cell destruction. This ability to kill targets rapidly, coupled with the fact that assembly of the mature synapse requires several minutes to occur further suggests that it is dispensable for target cell lysis, and that a stripped down synapse may be sufficient for destruction of target cells.

Altogether, these studies provide key initial information in the pursuit of understanding the separable nature of CTL killing and cytokine production. Further studies will be needed to move from the correlative results seen here to prove, as suggested by the authors, that differential regulation of immunological synapse assembly shapes these two different patterns of calcium signaling, and, in turn, the two different programs of function in these cells. The next question is how such differential assemblies are regulated; if cytotoxic components of the synapse are recruited at lower antigen densities, how are these thresholds determined at the molecular level, and what are the specific mechanisms that allow different components to be recruited when different levels of T cell receptor signaling are reached? Also of interest is the question of whether the large-scale differences in synapse structure observed in this study at different pMHC complex densities are accompanied by even more diverse differences in molecular assemblies at length scales below the resolution of light microscopy. It is possible that the synapse, as it is currently understood, is only the highest-order manifestation of a hierarchy of molecular organization occurring at the interface of T cells and APCs, and that a full explanation of the dual activation threshold of T cells will only emerge when we become able to probe these ever-shrinking length scales.

See companion article on page 14145.

References

- 1.Sykulev, Y., Joo, M., Vturina, I., Tsomides, T. J. & Eisen, H. N. (1996) Immunity 4, 565–571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Demotz, S., Grey, H. M. & Sette, A. (1990) Science 249, 1028–1030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Valitutti, S., Muller, S., Dessing, M. & Lanzavecchia, A. (1996) J. Exp. Med. 183, 1917–1921. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Faroudi, M., Utzny, C., Salio, M., Cerundolo, V., Guiraud, M., Müller, S. & Valitutti, S. (2003) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 100, 14145–14150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Monks, C. R. F., Freiberg, B. A., Kupfer, H., Sciaky, N. & Kupfer, A. (1998) Nature 395, 82–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Grakoui, A., Bromley, S. K., Sumen, C., Davis, M. M., Shaw, A. S., Allen, P. M. & Dustin, M. L. (1999) Science 285, 221–227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Freiberg, B. A., Kupfer, H., Maslanik, W., Delli, J., Kappler, J., Zaller, D. M. & Kupfer, A. (2002) Nat. Immunol. 3, 911–917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Irvine, D. J., Purbhoo, M. A., Krogsgaard, M. & Davis, M. M. (2002) Nature 419, 845–849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Stinchcombe, J. C., Bossi, G., Booth, S. & Griffiths, G. M. (2001) Immunity 15, 751–761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Potter, T. A., Grebe, K., Freiberg, B. & Kupfer, A. (2001) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 98, 12624–12629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lewis, R. S. (2001) Annu. Rev. Immunol. 19, 497–521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Feske, S., Giltnane, J., Dolmetsch, R., Staudt, L. M. & Rao, A. (2001) Nat. Immunol. 2, 316–324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Winslow, M. M., Neilson, J. R. & Crabtree, G. R. (2003) Curr. Opin. Immunol. 15, 299–307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]