Abstract

Acid-sensing ion channels (ASICs) are proton-gated Na+ channels. They are implicated in synaptic transmission, detection of painful acidosis, and possibly sour taste. The typical ASIC current is a transient, completely desensitizing current that can be blocked by the diuretic amiloride. ASICs are present in chordates but are absent in other animals. They have been cloned from urochordates, jawless vertebrates, cartilaginous shark and bony fish, from chicken and different mammals. Strikingly, all ASICs that have so far been characterized from urochordates, jawless vertebrates and shark are not gated by protons, suggesting that proton gating evolved relatively late in bony fish and that primitive ASICs had a different and unknown gating mechanism. Recently, amino acids that are crucial for the proton gating of rat ASIC1a have been identified. These residues are completely conserved in shark ASIC1b (sASIC1b), prompting us to re-evaluate the proton sensitivity of sASIC1b. Here we show that, contrary to previous findings, sASIC1b is indeed gated by protons with half-maximal activation at pH 6.0. sASIC1b desensitizes quickly but incompletely, efficiently encoding transient as well as sustained proton signals. Our results show that the conservation of the amino acids crucial for proton gating can predict proton sensitivity of an ASIC and increase our understanding of the evolution of ASICs.

Introduction

Acid-sensing ion channels (ASICs) are ligand-gated channels that are gated open by the binding of protons, the simplest ligand possible. In the continued presence of protons, ASICs desensitize. They are involved in synaptic transmission (Wemmie et al. 2002) and transduction of painful acidosis (Jones et al. 2004; Yagi et al. 2006; Deval et al. 2008) and have been implicated in cell death accompanying stroke (Xiong et al. 2004), in autoimmune inflammation of the central nervous system (Friese et al. 2007), and in seizure termination during epilepsy (Ziemann et al. 2008).

Mammals contain four genes coding for ASICs: ASIC1–4 (Waldmann & Lazdunski, 1998; Gründer et al. 2000); the use of alternative first exons gives rise to the variants ASIC1b (Chen et al. 1998; Bässler et al. 2001) and ASIC2b (Lingueglia et al. 1997). One characterizing feature of ASIC subtypes is their time course of desensitization: time constants vary over a 100-fold range from 10 ms (Paukert et al. 2004b) to several seconds (Lingueglia et al. 1997). Usually, desensitization is complete; among homomeric ASICs, only rat ASIC3 desensitizes incompletely (Waldmann et al. 1997; Hesselager et al. 2004; Salinas et al. 2009), but at rather low pH values (pH ≤ 5.0).

The primary sequence of ASICs shows two hydrophobic domains that could span the membrane, a large loop (> 350 amino acids) between these domains, and rather short N- and C-termini. A topology with two transmembrane domains, a large ectodomain and intracellular N- and C-termini has been experimentally confirmed (Saugstad et al. 2004). All ASICs contain 14 conserved cysteine residues within the ectodomain (Paukert et al. 2004b) that may stabilize its structure (Firsov et al. 1999). In addition, each ASIC contains at least one consensus sequence for N-glycosylation and glycosylation may assist the proper folding of the ectodomain (Kadurin et al. 2008). These features have recently been confirmed by the crystal structure of a chicken ASIC1 deletion mutant (Jasti et al. 2007). Moreover, the crystal structure revealed the three-dimensional folding of the ectodomain: it is composed of five subdomains which are connected to the membrane-spanning domains by an apparently flexible wrist (Jasti et al. 2007). The crystal represents the desensitized conformation of the channel (Gonzales et al. 2009); thus, it does not provide direct evidence for the proton sensor of ASICs. A recent comprehensive mutagenesis screen of conserved titratable amino acids identified four amino acids of ASIC1a that are important for proton-gating: Glu63, His72/His73, and Asp78 (Paukert et al. 2008). The presence of these amino acids correlated well, though not perfectly, with the proton sensitivity of ASICs (Paukert et al. 2008).

To gain further insight into the structural determinants of proton sensitivity of ASICs and to understand whether proton sensitivity is an ancient feature of ASICs, ASICs have been cloned from different chordate species; they are absent in other animals like Drosophila or C. elegans. ASICs have been cloned from the urochordate Ciona (Coric et al. 2008), the simple, jawless vertebrate lamprey (Coric et al. 2005), the cartilaginous shark spiny dogfish (Coric et al. 2005), and the teleosts toadfish (Coric et al. 2003, 2005) and zebrafish (Paukert et al. 2004b); moreover, they have been cloned from the chicken (Coric et al. 2005) and different mammals. It has been reported that ASICs from Ciona, lamprey and shark are not gated by protons (Coric et al. 2005, 2008), suggesting that proton gating first evolved in bony fish and that ASICs of primitive chordates have a different and unknown gating stimulus. Since related channels from the cnidarian Hydra are gated by neuropeptides (Golubovic et al. 2007), it is, for example, conceivable that early ASICs were gated by neuropeptides.

From shark, so far two ASICs have been cloned, sASIC1a and sASIC1b; both have been cloned from brain. sASIC1a and 1b have the highest sequence homology to rat ASIC1b and zebrafish ASIC1.1 (zASIC1.1; Coric et al. 2005). The amino acids that are critical for H+ sensitivity of rat ASIC1a are completely conserved in sASIC1b, prompting us to re-evaluate proton sensitivity of sASIC1b. Here we show that sASIC1b is indeed gated by protons and produces typical rapidly desensitizing Na+ currents that are sensitive to amiloride. In addition and in contrast to other ASICs, a small sustained current persists during even slight acidification (pH < 7.0). Our results show that the proton sensitivity of ASICs arose earlier in evolution than previously thought, at latest in cartilaginous fish. Moreover, they consolidate the definition of a ‘proton sensitivity signature’ in ASICs.

Methods

Electrophysiology

The cDNA of shark ASIC1b was cloned from the brain of the spiny dogfish Squalus acanthias (Coric et al. 2005); it was a kind gift of C. M. Canessa (Yale University). Our sequence analysis of this cDNA differs from the sASIC1b sequence, which is in the DDBJ/EMBL/GenBank databases (accession no. AY956392), at two residues in the cytoplasmic C-terminus: an R instead of a K at position 496 and an A instead of a V at 498. The same amino acids (R and A) are found at the corresponding positions in the closely related toadfish ASIC1.1 and zASIC1.1.

We subcloned this cDNA into expression vector pRSSP, which is optimized for functional expression in Xenopus oocytes, containing the 5′- untranslated region from Xenopusβ-globin and a poly(A) tail (Bässler et al. 2001). Chimeric and mutant channels were generated by recombinant PCR using standard protocols with KAPA HiFi DNA polymerase (Peqlab). All PCR-derived fragments were entirely sequenced.

Oocytes were surgically removed under anaesthesia (2.5 g l−1 tricaine methanesulfonate for 20–30 min) from adult Xenopus laevis females and kept in OR-2 medium (82.5 mm NaCl, 2.5 mm KCl, 1.0 mm Na2HPO4, 5.0 mm Hepes, 1.0 mm MgCl2, 1.0 CaCl2 and 0.5 g l−1 polyvinylpyrrolidone). Anaesthetized frogs were killed after the final oocyte collection by decapitation. Animal care and experiments followed approved institutional guidelines at RWTH Aachen University.

Synthesis of cRNA was done as previously described (Paukert et al. 2004b). We injected 0.8–8 ng of sASIC1b cRNA per oocyte. Whole-cell currents were recorded after 1–4 days with a TurboTec 03X amplifier (npi electronic, Tamm, Germany) using an automated, pump-driven solution exchange system together with the oocyte testing carousel controlled by the interface OTC-20 (npi electronic) (Madeja et al. 1995). With this system, 80% of the bath solution (10–90%) is exchanged within 300 ms (Chen et al. 2006b). Data acquisition and solution exchange were managed using CellWorks version 5.1.1 (npi electronic). Data were filtered at 20 Hz and acquired at 1 kHz. Holding potential was −70 mV if not otherwise indicated. All experiments were performed at room temperature (20–25°C). Psalmotoxin 1 (PcTx 1) was purchased from Alomone Labs (Jerusalem, Israel).

Bath solution for the two-electrode voltage clamp contained 140 mm NaCl, 1.8 mm CaCl2, 1.0 MgCl2, 10 mm Hepes. For the acidic test solutions, Hepes was replaced by Mes buffer. Solutions containing the spider toxin psalmotoxin 1 (PcTx1) were supplemented with 0.05% bovine serum albumin (BSA) (Sigma-Aldrich) in order to avoid absorption by the tubing. Glass electrodes filled with 3 m KCl and a resistance of 0.3–1.5 MΩ were used.

Determination of surface expression

The haemagglutinin (HA) epitope (YPYDVPDYA) of the influenza virus was inserted in the extracellular loop of sASIC1b between residues R161 and N162. HA-tagged sASIC1b formed a proton-activated channel with an estimated apparent H+ affinity indistinguishable from untagged channels (results not shown). The oocytes were injected with 8 ng of cRNA and surface expression was determined as previously described (Zerangue et al. 1999; Chen & Gründer, 2007; Chen et al. 2007). Briefly, oocytes expressing shark ASIC1b were placed for 30 min in ND96 with 1% BSA to block unspecific binding, incubated for 60 min with 0.5 μg ml−1 of rat monoclonal anti-HA antibody (3F10, Roche), washed extensively with ND96–1% BSA, and incubated for 90 min with 2 μg ml−1 of horseradish peroxidase-coupled secondary antibody (goat anti-rat Fab fragments, Jackson ImmunoResearch). Oocytes were washed six times with ND96–1% BSA and three times with ND96 without BSA. All steps were performed on ice. Oocytes were then placed individually in wells of microplates and luminescence was quantified in a Berthold Orion II luminometer (Berthold detection systems; Pforzheim, Germany). The chemiluminescent substrates (50 μl Power Signal Elisa; Pierce) were automatically added and luminescence measured after 2 s for 5 s. Relative light units (RLUs) per second were calculated as a measure of surface-expressed channels. RLUs of HA-tagged channels were at least 400-fold higher than RLUs of untagged channels. The results are from two independent frogs; at least eight oocytes were analysed for each experiment and each condition.

Data analysis

Data were analysed with the software IGOR Pro (WaveMetrics, Lake Oswego, OR, USA). Concentration–response curves were fitted to the Hill function

where Imax is the maximal current, a is the residual current, EC50 is the pH/concentration at which half-maximal activation/block of the transient current component was achieved, and n is the Hill coefficient. For pH activation and steady-state desensitization curves, Imax was set to 1 and a to 0.

Current decay kinetics of the fast transient currents were fitted with a mono-exponential function:

where A0 is the relative amplitude of the non-desensitizing component, A is the relative amplitude of the desensitizing component and τ is the time constant of desensitization.

Current decay kinetics of the slow ‘sustained’ currents were best fitted with the sum of two exponential components

where A0, A1 and A2 are the relative amplitudes of the various components, and τ1 and τ2 are the slow and fast time constants, respectively.

Results are reported as means ±s.e.m. They represent the mean of n individual measurements on different oocytes. Statistical analysis was done using Student's unpaired t test.

Results

Functional characterization of shark ASIC1b

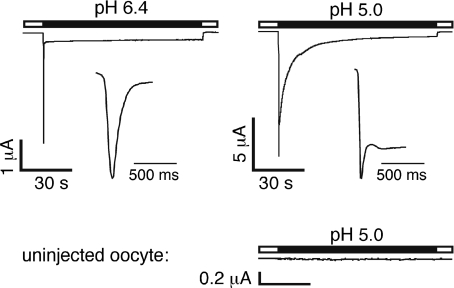

Oocytes expressing sASIC1b generated robust currents when stimulated by pH 6.4. These currents were typical rapidly activating and desensitizing ASIC currents (Fig. 1); we did not observe such currents in oocytes that did not express sASIC1b (Fig. 1). The sASIC1b current desensitized with a time constant < 50 ms; the rapid gating of this channel precluded a more precise determination of the time course of desensitization. Most of the current rapidly declined due to desensitization; a small fraction (∼5%), however, persisted even after prolonged (90 s) acid application without any sign of desensitization (Fig. 1). Such a sustained current is known from ASIC3 (Waldmann et al. 1997); ASIC3, however, generates a sustained current only at very acidic pH ≤ 5 (Waldmann et al. 1997; Salinas et al. 2009). Application of pH 5.0 to oocytes expressing sASIC1b generated transient currents of larger amplitude than pH 6.4. Moreover, at pH 5, after a short delay a second current component developed with a variable amplitude around 50% of the amplitude of the transient current. This second current component desensitized much slower than the initial transient current. The time course of desensitization of the slow current component was best fitted by a double-exponential function with time constants τ1= 16 ± 4 s and τ2= 3.1 ± 0.2 s (n= 7; Table 1). Similar to the current at pH 6.4, the current at pH 5.0 did not completely desensitize but relaxed to a sustained steady-state level; the double-exponential fit revealed a level of 2.6 ± 0.5% of the initial amplitude of the slow component at steady state (Table 1), which is in the same order as the sustained level at higher pH (normalized to the transient current at pH 5; see below). At pH 5, the sASIC1b current is, thus, qualitatively very similar to the ASIC3 current (Salinas et al. 2009). In the remainder of this study, we will refer to the typical transient ASIC current as the ‘transient current’ and to the second slow current component at pH 5.0 as the ‘slow current’.

Figure 1. Shark ASIC1b is H+ sensitive.

Top, representative traces of sASIC1b currents at pH 6.4 and pH 5.0. Note the sustained current at pH 6.4 and the two current components at pH 5. The current rise phase and the initial desensitization phase are also shown on an expanded time scale. Bottom, representative current trace of an uninjected oocyte. No currents are elicited by pH 5.0.

Table 1.

Parameters describing desensitization of the slow current component of shark ASIC1b at pH 5.0

| Parameter | Value | s.e.m. | n |

|---|---|---|---|

| a0 (%) | 2.6 | 0.5 | 7 |

| a1 (%) | 24.1 | 2.2 | 7 |

| a2 (%) | 73.3 | 2.4 | 7 |

| τ1 (s) | 16 | 4 | 7 |

| τ2 (s) | 3.1 | 0.2 | 7 |

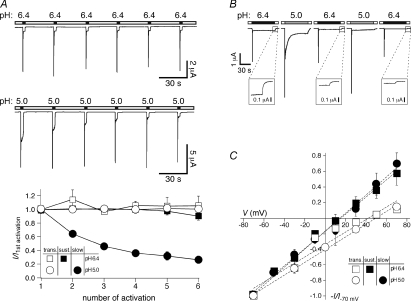

Repetitive application of pH 6.4 to oocytes expressing sASIC1b with an interval of 30 s elicited transient currents of similar amplitude (Fig. 2A), showing that recovery from desensitization was complete in 30 s. As expected for a non-desensitizing current, the amplitude of the sustained current also did not change with repetitive applications of pH 6.4. Repetitive application of pH 5 also elicited transient currents of similar amplitude (Fig. 2A); in contrast, the initial amplitude of the slow current diminished progressively towards a steady-state level (Fig. 2A). Even after intervals of 3 min, the slow current did not recover (not shown). This result shows that the slow current recovers slowly from desensitization, if at all, similar to ASIC3 (Salinas et al. 2009).

Figure 2. Characterization of the sustained sASIC1b current.

A, top, representative current traces of sASIC1b that was repeatedly activated by application of either pH 6.4 or 5 for 3 s. Channels were allowed to recover in conditioning pH 7.4 for 30 s. Bottom, current amplitudes were normalized to the first amplitude. The initial amplitude of the slow current component at pH 5 decreased progressively. Absolute values of the initial amplitudes were 4.1 ± 0.5 μA (transient current at pH 6.4; n= 7), 0.3 ± 0.05 μA (sustained current at pH 6.4; n= 7), 5.8 ± 1.8 μA (transient current at pH 5; n= 6), and 1.7 ± 0.4 μA (slow current at pH 5; n= 6), respectively. B, desensitization of the sustained current at pH 6.4 by application of pH 5.0. Channels were alternately activated by pH 6.4 and pH 5.0. The amplitude of the sustained current (magnified in the insets) successively decreased after application of pH 5.0. C, current–voltage relationship for the transient and the sustained current at pH 5.0 and 6.4, respectively. For the transient currents, channels had been repeatedly activated at different holding potentials; for the sustained and slow currents, channels had been activated with pH 6.4 or 5.0, respectively, and voltage steps from −70 to +70 mV of 1 s duration were applied. Voltage steps at pH 5.0 were applied 60 s after activation when the slow current had relaxed to a constant amplitude. Absolute values of the current amplitudes at −70 mV were 19.4 ± 4.5 μA (transient current at pH 5.0; n= 6), 0.78 ± 0.12 μA (transient current at pH 6.4; n= 12), 0.33 ± 0.07 μA (sustained current at pH 5.0; n= 9–11 for voltage jumps between −70 mV and +30 mV; n= 3–5 for voltage jumps at +50 mV and +70 mV) and 0.44 ± 0.09 μA (sustained current at pH 6.4; n= 7), respectively.

Since the slow current developed after the transient current and did not completely desensitize, we wondered whether this current has the same basis as the sustained current at pH 6.4. In order to address this question, we asked whether the slow current at pH 5.0 cross-desensitizes the sustained current at pH 6.4. This was indeed the case: after a 1 min application of pH 5.0 the amplitude of the sustained current at pH 6.4 was significantly smaller (49 ± 10% of the initial amplitude, P < 0.01) than before the pH 5.0 application (Fig. 2B). A second pH 5.0 application further decreased the sustained current at pH 6.4 (42 ± 10% of the initial amplitude, P < 0.05; Fig. 2B). This is in contrast to several applications of pH 6.4, which did not desensitize the sustained current (Fig. 2A). Cross-desensitization of the sustained current at pH 6.4 by pH 5.0 suggests that the sustained current has a similar basis to the slow current. This interpretation implies that the slow current starts to desensitize only at pH values < 6.4 (see also below).

The reversal potential of the transient current was around 50 mV (Fig. 2C), indicating a Na+-selective current, which is typical for ASICs. For the sustained current at pH 6.4, the reversal potential was shifted by approximately 30 mV to the left (Fig. 2C), indicating a lower Na+ selectivity. The reversal potential of the slow current at pH 5.0 was similar to the reversal potential of the sustained current (Fig. 2C), supporting the idea that both currents have the same basis. Similar non-selective sustained currents are also carried by the ASIC3/2b heteromer (Lingueglia et al. 1997).

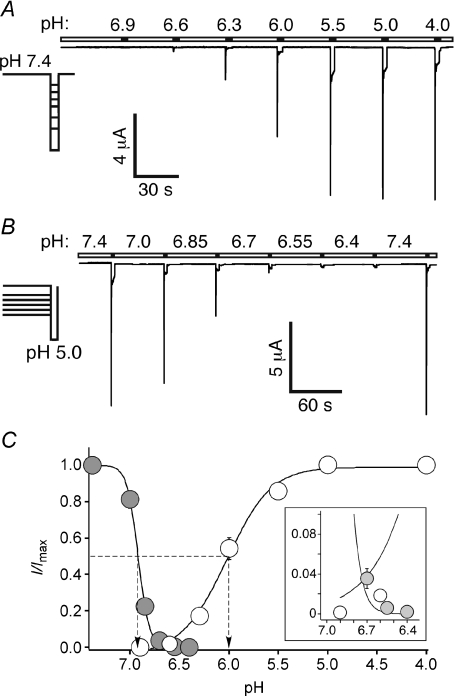

The amplitude of the transient sASIC1b current increased with increasing H+ concentrations and saturated at pH 5.0 (Fig. 3A); half-maximal activation was reached at pH 6.0 ± 0.04 (n= 15; Fig. 3C). Due to the long-lasting desensitization, the apparent H+ affinity of the slow current could not be determined precisely. Pre-conditioning by slight acidification for 60 s revealed that the number of channels available for activation diminished at pH values below 7.4 so that at a pre-conditioning pH of 6.55 no transient currents could be recorded any more (Fig. 3B). Steady-state desensitization of the transient current was half-maximal at pH 6.9 ± 0.01 (n= 11; Fig. 3C). In contrast, even at a conditioning pH of 6.4, small sustained currents were still elicited (Fig. 3B).

Figure 3. Apparent H+ affinity of shark ASIC1b.

A, representative current trace of oocytes expressing sASIC1b. Channels were activated for 3 s by varying low pH, as indicated. Conditioning pH 7.4 was applied for 30 s. B, channels were activated by pH 5.0 with varying pre-conditioning pH, as indicated. Conditioning pH was applied for 60 s. C, pH–response curves for activation (open circles) and steady-state desensitization (grey circles); lines represent fits to the Hill function. Dotted lines indicate EC50 values. Only the transient current was analysed. The overlapping region of the activation and inactivation curves is magnified (inset). Absolute values of the current amplitudes were 4.9 ± 1.2 μA (activation curve, pH 5.0; n= 15) and 8.4 ± 1.9 μA (steady-state desensitization curve, conditioning pH 7.4; n= 11), respectively.

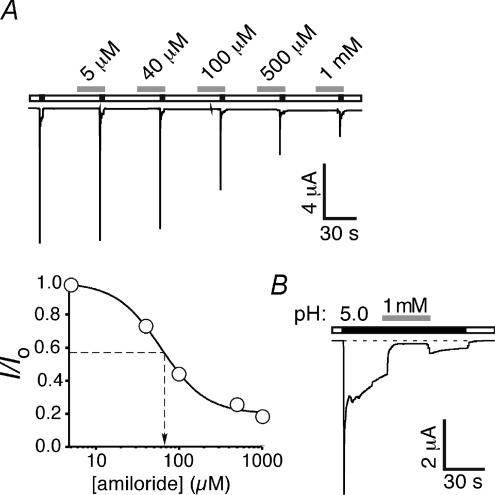

Pharmacology of shark ASIC1b

The sASIC1b current was sensitive to amiloride: the transient current was half-maximally blocked by 78 ± 12 μm amiloride (n= 21; Fig. 4A), similar to other ASICs (Paukert et al. 2004b). Amiloride at concentrations up to 4 mm did not completely block this current (not shown); however, the fast desensitization of the transient current may mask a higher amiloride affinity of the channel. In agreement with this hypothesis, 1 mm amiloride blocked the slow current to a larger extent than the transient current (Fig. 4B). The kinetics, Na+ selectivity, pH activation and steady-state desensitization curves, and block by amiloride all identify the transient sASIC1b current as a typical ASIC current.

Figure 4. Shark ASIC1b is amiloride-sensitive.

A, top, representative traces of sASIC1b currents in the presence of increasing concentrations of amiloride, as indicated. sASIC1b was activated with pH 5.0. Bottom, concentration–response curve for amiloride; the line represents a fit to the Hill function. Dotted lines indicate the EC50 value. Absolute value of the current amplitude without amiloride was 4.6 ± 0.7 μA (n= 21). B, the sustained current was almost completely blocked by 1 mm amiloride (grey bar).

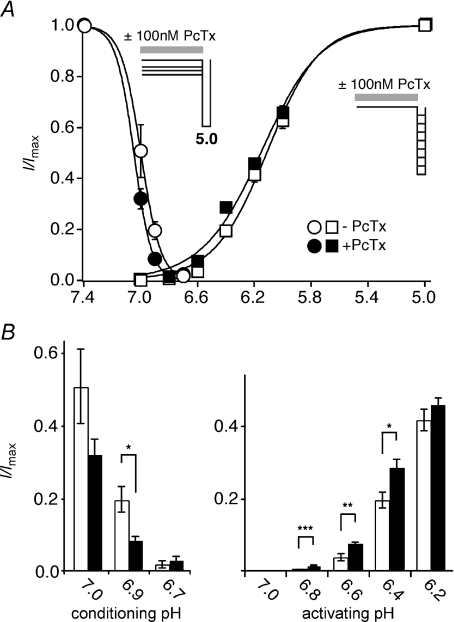

The spider toxin PcTx1 is a specific inhibitor of homomeric ASIC1a (Escoubas et al. 2000); it inhibits ASIC1a by increasing its apparent H+ affinity (Chen et al. 2005), transferring all channels into the desensitized conformation at pH 7.4. By contrast, homomeric ASIC1b is not inhibited by PcTx1 but opened at slight acidification (Chen et al. 2006a). Therefore the binding of PcTx1 is state dependent: for ASIC1a, it binds with highest affinity to the desensitized state and for ASIC1b, to the open state (Chen et al. 2006a). So far, modulation has been shown for rat, mouse and chicken ASIC1 (Escoubas et al. 2000; Chen et al. 2005, 2006a; Samways et al. 2009). To investigate whether ASIC1b from shark is also modulated by PcTx1, we investigated the effect of PcTx1 on the steady-state desensitization and pH activation curves of sASIC1b. This tests the stabilization of the desensitized and the open conformation, respectively. PcTx1 at 100 nm did not significantly shift the steady-state desensitization or the activation curve of sASIC1b (Fig. 5A). For comparison, 30 nm PcTx1 shifts the steady-state desensitization curve of rat ASIC1a by ∼0.3 pH units (Chen et al. 2005) and 100 nm PcTx1 shifts the activation curve of rat ASIC1b by ∼0.4 pH units (Chen et al. 2006a). In contrast to rat ASIC1b (Chen et al. 2006a), there were also no effects of PcTx1 on the desensitization of sASIC1b. Furthermore, the amplitude of the sustained current relative to the transient current at pH 6.6 was not significantly different when PcTx1 was present or absent (results not shown). Thus, PcTx1 does not strongly stabilize the desensitized or the open state of sASIC1b.

Figure 5. Shark ASIC1b is slightly modulated by psalmotoxin 1.

A, pH–response curves for activation (squares) and steady-state desensitization (circles) with (filled symbols) and without (open symbols) pre-application of 100 nm psalmotoxin (PcTx); PcTx was present only in the conditioning period (60 s). For activation curves, channels had been activated for 3 s by varying low pH, as indicated. For steady-state desensitization curves, channels had been activated for 3 s by pH 5.0 with varying pre-conditioning pH, as indicated. Lines represent fits to the Hill function. Absolute values of the current amplitudes were 8.4 ± 2.6 μA (activation curve, pH 5.0, without PcTx; n= 6), 8.3 ± 1.8 μA (activation curve, pH 5.0, with PcTx; n= 6), 8.9 ± 2.7 μA (steady-state desensitization curve, conditioning pH 7.4, without PcTx; n= 6) and 4.5 ± 1.4 μA (steady-state desensitization curve, conditioning pH 7.4, with PcTx; n= 6), respectively. B, bar graphs comparing normalized current amplitudes at slight acidification for the data from A. Open bars, without PcTx1; filled bars, with PcTx1. For conditioning pH 6.9, significantly more channels were desensitized when PcTx was present; similarly, for activation by pH 6.8–6.4 current amplitudes were significantly larger when PcTx was present. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001.

There were subtle effects of PcTx1, however, that led to significant changes of the current amplitudes at certain pH values. At steady state and a conditioning pH of 6.9, significantly more channels were desensitized when PcTx1 was present than when it was absent (Fig. 5B). Similarly, slight acidification (pH 6.8–6.4) opened significantly more channels in the presence than in the absence of PcTx1 (Fig. 5B). This result shows that PcTx1 slightly promotes desensitization and opening of sASIC1b at low agonist concentrations, suggesting that PcTx1 indeed binds to and stabilizes the desensitized and the open conformation of sASIC1b, qualitatively similar to rat ASIC1 (Chen et al. 2006a). The comparatively subtle effects of PcTx1 can be due to either a low PcTx1 affinity of sASIC1b or a subtle effect of PcTx1 binding on gating of sASIC1b. In summary, subtle effects of PcTx1 on sASIC1b suggest that the PcTx1 binding site (Pietra, 2009; Qadri et al. 2009) is partially conserved in sASIC1b, suggesting that it is an evolutionary old pocket in the three-dimensional structure of ASIC1.

Mutational analysis of shark ASIC1b

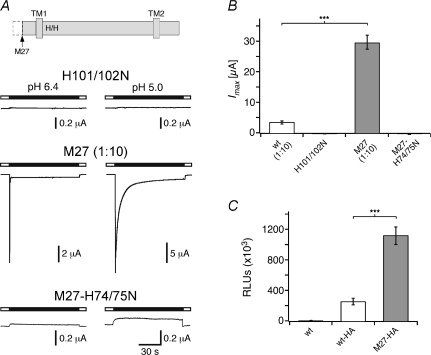

A pair of histidines that is indispensable for H+ sensitivity of rat ASIC1a is conserved in sASIC1b (Paukert et al. 2008). When both histidines were exchanged by asparagines (H101/H102N), sASIC1b was no longer sensitive to H+ (pH ≥ 4; Fig. 6A): both the transient and the slow current were no longer elicited by H+. This result shows that fundamental structural requirements for H+ sensing are also conserved in sASIC1b. Collectively, these results suggest that the gating mechanism of ASICs is conserved from shark to mammals.

Figure 6. A pair of histidines is indispensable for H+ sensitivity of shark ASIC1b.

A, top, schematic illustration of the topology of sASIC1b. TM1, TM2: transmembrane domains. The arrow indicates the position of the N-terminal truncation in construct M27; the two conserved histidines localize to the proximal ectodomain. Bottom, representative current traces for sASIC1b-H101/102N, -M27, and -M27-H74/75N. Note that for M27-H74/75N, application of H+ slightly reduced the background current. B, bars representing the peak current amplitude (mean ±s.e.m.) of oocytes expressing wild-type sASIC1b (wt), the histidine mutant (H101/102N), and the two M27-mutants (n≥ 6); channels had been activated by pH 5.0. The amounts of cRNA that had been injected into each oocyte were 0.8 ng (wt and M27) or 8 ng (H101/102N and M27-H74/75N), respectively. ***P≪ 0.01. C, bars representing surface expression of sASIC1b and -M27; untagged sASIC1b served as a control (left bar). Results are expressed as relative light units (RLUs) per oocyte per second (n= 36). ***P≪ 0.01.

Amplitudes of transient sASIC1b currents usually ranged between 1 and 10 μA (Fig. 6B, first bar). Amplitudes of rat ASIC1b, which are of similar magnitude, can be increased by deletion of an N-terminal domain (Bässler et al. 2001), which is conserved in sASIC1b. Deletion of this N-terminal domain increases surface expression of zASIC4.1 (Chen et al. 2007). Deletion of this domain in sASIC1b (sASIC1b-M27) increased current amplitudes by about tenfold (Fig. 6B, third bar), indicating that the N-terminal domain controls surface expression of sASIC1b. Substitution of the conserved histidine pair (H74/H75, corresponding to H101/102 in the wild-type) also rendered the highly expressing variant sASIC1b-M27 H+ insensitive (Fig. 6A and B, fourth bar), confirming the importance of these histidines. Sustained and slow currents were identical between wild-type sASIC1b and sASIC1b-M27 (Fig. 6A), as well as the apparent affinity for H+ of the transient current (not shown), suggesting that the N-terminal domain has a specific role in the trafficking of sASIC1b.

To more specifically address surface expression of sASIC1b-M27, we introduced an HA-epitope in the ectodomain of sASIC1b and sASIC1b-M27 and assessed the presence of epitope-tagged channels on the surface of intact oocytes using a monoclonal anti-HA antibody and a luminescence assay (see Methods). Deletion of the N-terminal domain in sASIC1b-M27 increased surface expression 4.5-fold compared to wild-type (Fig. 6C), showing that the N-terminal domain indeed leads to inefficient surface expression of shark ASIC1b. Inefficient surface expression together with the fast kinetics may be the reason why a previous study reported that sASIC1b is H+ insensitive (Coric et al. 2005).

The sustained current of shark ASIC1b

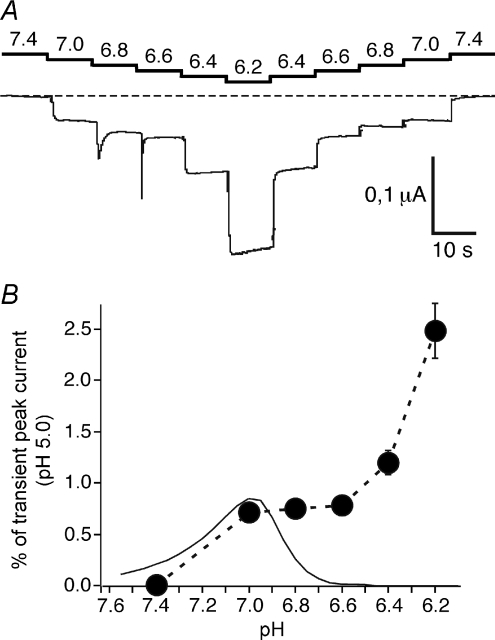

A striking feature of sASIC1b was the sustained current at mild acidification (Fig. 1). It endows this ASIC with the capacity also to encode sustained H+ signals of small amplitude, as illustrated in Fig. 7. Similar to a previous study that mimicked the effect of mild acidification on ASIC3 (Yagi et al. 2006), pH was decreased from 7.4 to 6.2 in steps of 0.2 units, with each step held for 10 s (Fig. 7A). Under these conditions, sASIC1b already generated non-desensitizing currents at pH 7.0. Slightly stronger acidification to pH 6.8 and 6.6 generated transient currents in addition to sustained currents, which were of slightly larger amplitude than at pH 7.0. Below pH 6.6, due to steady-state desensitization of the transient current (Fig. 3C), only the sustained currents remained, the amplitude of which further increased. Only at pH 6.2 was some desensitization of the sustained current apparent. This result demonstrates that sASIC1b generates sustained H+ signals over a pH range from 7.0 to 6.4 without any apparent desensitization.

Figure 7. Small pH steps evoke sustained shark ASIC1b currents.

A, pH was stepped from 7.4 to 6.2 in steps of 0.2 units (first step: 0.4 units; top). A representative current trace is shown (bottom). B, current versus pH relationship of sustained currents (filled circles; n= 12) measured as in A and the predicted window current (smooth curve). The window current was calculated by multiplying values at each pH of the activation and steady-state desensitization curve fits from Fig. 3C; the fit for the activation curve was refined for low H+ concentrations by measuring transient currents also at pH 6.95 (I= 0 μA; n= 15).

As was previously shown for ASIC3, overlap of steady-state activation and desensitization curves can generate a sustained ‘window current’ (Yagi et al. 2006). In order to determine the window current of sASIC1b, we multiplied values of the two curves that were fitted to the data in Fig. 3C (Fig. 7B, smooth curve). We then compared the predicted window current with the current amplitude of the sustained current (expressed as a fraction of the transient current amplitude at pH 5) that we actually measured. As can be seen in Fig. 7B, both curves matched well from pH 7.4 to 7.0, suggesting that the sustained current at pH 7.0 is a pure window current. At pH values below pH 7.0, however, the plot for the sustained current starts to deviate from the predicted window current. The additional sustained current, which cannot be explained by the window current, is probably carried by the non-selective sustained current that we observed at pH 6.4. Thus, the sustained current between 7.0 and 6.6 is a mixture of window current and the non-selective sustained current and at pH values below 6.6, the sustained current is solely carried by the non-selective sustained current. If this interpretation were correct, the non-selective sustained current of sASIC1b would start to activate just below pH 7.0, effectively being so far the most sensitive sustained ASIC current that is not a window current.

Discussion

Our study has two key findings: (1) we show that the presence of the ‘proton sensitivity signature’ can predict H+ sensitivity of an ASIC, and (2) we show that H+ sensitivity of ASICs evolved latest in cartilaginous fish. Moreover, we show that sASIC1b has a sustained current component, which is unusually sensitive to H+.

The ‘H+ sensitivity signature’

A recent study identified a few amino acids that are important for H+ sensitivity of rat ASIC1a (Paukert et al. 2008). These amino acids are E63, H72/H73, and D78 and cluster in the proximal ectodomain. Substitution of E63 or D78 together with amino acids that mediate open channel block by Ca2+ (Paukert et al. 2004a) renders ASIC1a H+ insensitive; substitution of the histidine pair H72/H73 has the same effect. The crucial role of a histidine at this position had also previously been shown for ASIC2a (Baron et al. 2001; Smith et al. 2007). The precise role of these amino acids for ASIC gating is unknown, but it has been proposed that protonation of H72/H73 induces channel opening (Paukert et al. 2008). All ASICs that contain these amino acids are H+ sensitive, with two exceptions: sASIC1b and zASIC2 (Paukert et al. 2008). In the present study we show that sASIC1b is indeed H+ sensitive, reducing the number of H+-insensitive ASICs containing the ‘H+ sensitivity signature’ to one; we speculate that zASIC2 contains some unknown sequence features that render this channel H+ insensitive despite the presence of the critical amino acids.

The critical amino acids are not conserved in all H+-sensitive ASICs (Paukert et al. 2008). For example, zASIC1.1 does not contain the crucial His residue. Thus, it is clear that at present we cannot predict with certainty the H+ sensitivity of an ASIC solely based on the amino acid sequence. However, the present study is an example in which we can predict it with some reliability, justifying the definition of a ‘H+ sensitivity signature’.

Other regions implicated in the H+ sensitivity of ASICs are a putative Ca2+-binding site in the ion pore (Immke & McCleskey, 2003) and a cluster of acidic amino acids, the acidic pocket, that was identified in the crystal structure of chicken ASIC1 (Jasti et al. 2007). Both elements are supposed to hold a Ca2+ ion in the closed state. H+ would compete with these Ca2+ ions and displace them during acidification, triggering the opening of the ion pore. Both elements individually are not absolutely necessary for the H+ sensitivity of an ASIC (Paukert et al. 2004a; Li et al. 2009), but probably contribute to H+ sensitivity. The acidic pocket for example, determines apparent proton affinity of an ASIC (Sherwood et al. 2009). Crucial elements of the Ca2+-binding site in the ion pore are two acidic amino acids (Paukert et al. 2004a) that are conserved in sASIC1b (Glu441 and Asp448). Similarly, the eight acidic amino acids, which form three carboxyl-carboxylate pairs composing the acidic pocket and a fourth pair outside the acidic pocket (Jasti et al. 2007), are also conserved in sASIC1b (Glu108, Glu235, Asp253, Glu254, Asp361, Glu365, Asp423, and Glu432). Although the exact role of both elements in the H+ sensitivity of ASICs is still uncertain, their presence in sASIC1b is in agreement with its H+ sensitivity.

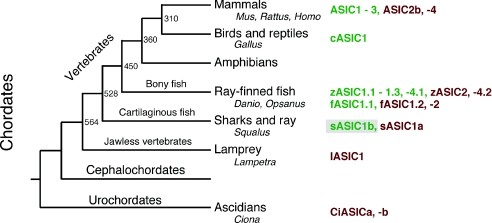

When did H+ sensitivity of ASICs evolve?

Previous studies (Coric et al. 2005, 2008) suggested that proton-gating first evolved in bony fish (Fig. 8) and that ASICs of primitive chordates have a different gating stimulus. Here we clearly show that this is not true for shark. sASIC1b generates typical ASIC currents, showing that H+ sensitivity evolved latest in cartilaginous fish. Cartilaginous fish evolved some 80 million years earlier than bony fish, approximately 500 million years ago (Kumar & Hedges, 1998) (Fig. 8). What about the ASICs from chordates that diverged even earlier from higher vertebrates?

Figure 8. Phylogenetic tree illustrating the main branches of chordates.

Individual ASICs are shown on the right; proton-sensitive ASICs in green, presumably proton-insensitive ASICs in red; sASIC1b is shown on a grey background. Genera from which ASICs have been cloned are also indicated. An estimate of the time of some branching events is given (Kumar & Hedges, 1998).

ASIC1 from the jawless vertebrate lamprey is H+ insensitive (Coric et al. 2005) and does not contain the H+ sensitivity signature (Paukert et al. 2008). Since mammalian ASIC1a has a high H+ affinity and a widespread expression in the nervous system, H+ insensitivity of lamprey ASIC1 is a striking feature, suggesting a ligand different from H+ for this ASIC. However, so far only ASIC1 has been cloned and characterized from the lamprey and it remains an open question whether the lamprey does also contain H+-sensitive ASICs. Higher vertebrates, for example, contain H+-insensitive ASICs such as ASIC2b and ASIC4 of mammals (Lingueglia et al. 1997; Gründer et al. 2000) and zASIC2 and zASIC4.2 of zebrafish (Paukert et al. 2004b), together with H+-sensitive ASICs. If such channels also existed in lamprey, it would be possible that lamprey ASIC1 contributes to H+-gated channels by formation of heteromeric channels, as has been shown for other H+-insensitive ASICs (Lingueglia et al. 1997; Chen et al. 2007).

Concerning the urochordate Ciona (Fig. 8), the Ciona genome contains a single ASIC gene, which gives rise to two splice forms (Coric et al. 2008). The cDNA sequence for one of these subtypes can be found in the public EMBL database. Similar to sASIC1b, this ASIC from Ciona contains the proton sensitivity signature, suggesting that the H+ sensitivity of this subtype should also be re-evaluated. Irrespective of the H+ sensitivity of Ciona ASIC, H+ insensitivity could also be a secondary, acquired feature. Given the close relationship of ASICs with peptide-gated channels from Cnidaria (Golubovic et al. 2007), it is tempting to postulate an agonist other than H+ for ASICs from primitive chordates; however, the possibility that some of these ASICs are H+ sensitive and that H+ ions are the original gating stimulus of ASICs should not be dismissed.

The sustained current of shark ASIC1b

Whereas the typical ASIC current is a transient current, a few ASICs also generate sustained currents (Hesselager et al. 2004). However, these currents are usually generated only at unphysiological acidic pH. For example, homomeric rat ASIC3, a well-studied subtype, generates sustained currents only at pH ≤ 5.0 (Waldmann et al. 1997). Nevertheless is it believed that ASIC3, a sensory neuron-specific ASIC, is a sensor of acidic and inflammatory pain (Deval et al. 2008). How can a channel that carries transient currents encode sustained acidification during a painful inflammation? This paradox has been solved by showing that pH activation and steady-state desensitization curves of ASIC3 overlap, allowing ASIC3 to carry a sustained ‘window current’ at the pH values of overlap (Yagi et al. 2006). The window of overlap is tiny, however, limiting the pH range where ASIC3 can carry sustained currents from 7.3 to 6.7 (Yagi et al. 2006); moreover, ASIC1a, another highly H+-sensitive ASIC, does not support such sustained window currents (Yagi et al. 2006).

Our results show that sASIC1b carries a bell-shaped window current at mild acidification between pH 7.4 and 6.6 (Fig. 7B), similar to ASIC3. Unique among homomeric ASICs, however, a second sustained current component developed already at only slightly more acidic pH below 7.0. Thus, the sustained current between pH 7.0 and 6.6 is a mix of a window current and a non-selective sustained current. The sustained current at pH 6.4 no longer has any contribution from the window current and is a pure non-selective sustained current (Fig. 7B). The tight overlap of window current and non-selective sustained current results in sustained sASIC1b currents over the whole pH range below pH 7.0. This behaviour is similar to heteromeric ASIC3/2a (Yagi et al. 2006), with the exception that the fractional sustained current of sASIC1b is up to 5-fold larger over the pH range from 7.0 to 6.2.

The relation of the non-selective sustained current at slight acidification (e.g. pH 6.4) to the slow current at pH 5.0 is not entirely clear. Cross-desensitization of the sustained current at pH 6.4 by the slow current (Fig. 2B) and the non-selectivity of both currents (Fig. 2C) suggest, however, that both currents are carried by the same state of the channel. This interpretation would imply that the slow current starts to develop at pH < 7.0, gradually increases in amplitude with increasing acidification and gets slowly, but profoundly desensitized by pH values < 6.2.

Other homomeric ASICs that generate sustained currents are zASIC4.1 and -4.2 (Paukert et al. 2004b; Chen et al. 2007). The sustained current of these subtypes differs from the sASIC1b sustained current in several ways: (1) it develops only slowly over 1 s (Chen et al. 2007) whereas the sASIC1b current develops at least ten times faster (Fig. 1); (2) it is insensitive to amiloride (Chen et al. 2007) whereas the sASIC1b current is sensitive to amiloride (Fig. 4B); (3) it depends on the presence of the N-terminal domain (Chen et al. 2007) whereas the sASIC1b deletion mutant (M27) also developed the sustained current (Fig. 6A). Thus, it seems that the sustained current of zASIC4.1 and 4.2 is unrelated to the sustained current of sASIC1b.

The sustained sASIC1b current endows this channel with the capacity to encode sustained acidification. ASIC3, with which sASIC1b shares many features, is involved in the detection of painful acidosis (Yagi et al. 2006; Deval et al. 2008). Although there is now clear evidence for nociception in bony fish (Sneddon, 2004), nociception in sharks, however, remains contested (Snow et al. 1993). Moreover, sASIC1b has been cloned from shark brain and its expression in dorsal root ganglia (DRGs) is unknown, rendering a role for sASIC1b in nociception hypothetical. In the brain, sASIC1b would carry a sustained depolarizing current during acidosis, suggesting that the extracellular pH has an important impact on neurons in shark brain.

Acknowledgments

We thank Cecilia Canessa for the generous gift of the shark ASIC1b clone and M. K. Schnizler for critical reading of the manuscript. This work was supported by grant GR 1771/3-5 of the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft to S.G.

Glossary

Abbreviations

- ASIC

acid-sensing ion channel

- HA

haemagglutinin

- PcTx1

the spider toxin psalmotoxin 1

- sASIC

shark ASIC

- zASIC

zebrafish ASIC

Author contributions

A.S. and S.G. conceived and designed the experiments of this study. A.S. collected the data and A.S. and S.G. analysed and interpreted them. S.G. wrote the manuscript with important intellectual input from A.S.; both authors have approved the final version of this manuscript.

References

- Baron A, Schaefer L, Lingueglia E, Champigny G, Lazdunski M. Zn2+ and H+ are coactivators of acid-sensing ion channels. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:35361–35367. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M105208200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bässler EL, Ngo-Anh TJ, Geisler HS, Ruppersberg JP, Gründer S. Molecular and functional characterization of acid-sensing ion channel (ASIC) 1b. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:33782–33787. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M104030200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen CC, England S, Akopian AN, Wood JN. A sensory neuron-specific, proton-gated ion channel. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1998;95:10240–10245. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.17.10240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen X, Gründer S. Permeating protons contribute to tachyphylaxis of the acid-sensing ion channel (ASIC) 1a. J Physiol. 2007;579:657–670. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2006.120733. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen X, Kalbacher H, Gründer S. The tarantula toxin psalmotoxin 1 inhibits acid-sensing ion channel (ASIC) 1a by increasing its apparent H+ affinity. J Gen Physiol. 2005;126:71–79. doi: 10.1085/jgp.200509303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen X, Kalbacher H, Gründer S. Interaction of acid-sensing ion channel (ASIC) 1 with the tarantula toxin psalmotoxin 1 is state dependent. J Gen Physiol. 2006a;127:267–276. doi: 10.1085/jgp.200509409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen X, Paukert M, Kadurin I, Pusch M, Gründer S. Strong modulation by RFamide neuropeptides of the ASIC1b/3 heteromer in competition with extracellular calcium. Neuropharmacology. 2006b;50:964–974. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2006.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen X, Polleichtner G, Kadurin I, Gründer S. Zebrafish acid-sensing ion channel (ASIC) 4, characterization of homo- and heteromeric channels, and identification of regions important for activation by H+ J Biol Chem. 2007;282:30406–30413. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M702229200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coric T, Passamaneck YJ, Zhang P, Di Gregorio A, Canessa CM. Simple chordates exhibit a proton-independent function of acid-sensing ion channels. FASEB J. 2008;22:1914–1923. doi: 10.1096/fj.07-100313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coric T, Zhang P, Todorovic N, Canessa CM. The extracellular domain determines the kinetics of desensitization in acid-sensitive ion channel 1. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:45240–45247. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M304441200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coric T, Zheng D, Gerstein M, Canessa CM. Proton sensitivity of ASIC1 appeared with the rise of fishes by changes of residues in the region that follows TM1 in the ectodomain of the channel. J Physiol. 2005;568:725–735. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2005.087734. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deval E, Noel J, Lay N, Alloui A, Diochot S, Friend V, Jodar M, Lazdunski M, Lingueglia E. ASIC3, a sensor of acidic and primary inflammatory pain. EMBO J. 2008;27:3047–3055. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2008.213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Escoubas P, De Weille JR, Lecoq A, Diochot S, Waldmann R, Champigny G, Moinier D, Menez A, Lazdunski M. Isolation of a tarantula toxin specific for a class of proton-gated Na+ channels. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:25116–25121. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M003643200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Firsov D, Robert-Nicoud M, Gründer S, Schild L, Rossier BC. Mutational analysis of cysteine-rich domains of the epithelium sodium channel (ENaC). Identification of cysteines essential for channel expression at the cell surface. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:2743–2749. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.5.2743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friese MA, Craner MJ, Etzensperger R, Vergo S, Wemmie JA, Welsh MJ, Vincent A, Fugger L. Acid-sensing ion channel-1 contributes to axonal degeneration in autoimmune inflammation of the central nervous system. Nat Med. 2007;13:1483–1489. doi: 10.1038/nm1668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Golubovic A, Kuhn A, Williamson M, Kalbacher H, Holstein TW, Grimmelikhuijzen CJ, Gründer S. A peptide-gated ion channel from the freshwater polyp Hydra. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:35098–35103. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M706849200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonzales EB, Kawate T, Gouaux E. Pore architecture and ion sites in acid-sensing ion channels and P2X receptors. Nature. 2009;460:599–604. doi: 10.1038/nature08218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gründer S, Geissler HS, Bässler EL, Ruppersberg JP. A new member of acid-sensing ion channels from pituitary gland. Neuroreport. 2000;11:1607–1611. doi: 10.1097/00001756-200006050-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hesselager M, Timmermann DB, Ahring PK. pH dependency and desensitization kinetics of heterologously expressed combinations of acid-sensing ion channel subunits. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:11006–11015. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M313507200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Immke DC, McCleskey EW. Protons open acid-sensing ion channels by catalyzing relief of Ca2+ blockade. Neuron. 2003;37:75–84. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(02)01130-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jasti J, Furukawa H, Gonzales EB, Gouaux E. Structure of acid-sensing ion channel 1 at 1.9 Å resolution and low pH. Nature. 2007;449:316–323. doi: 10.1038/nature06163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones NG, Slater R, Cadiou H, McNaughton P, McMahon SB. Acid-induced pain and its modulation in humans. J Neurosci. 2004;24:10974–10979. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2619-04.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kadurin I, Golubovic A, Leisle L, Schindelin H, Gründer S. Differential effects of N-glycans on surface expression suggest structural differences between the acid-sensing ion channel (ASIC) 1a and ASIC1b. Biochem J. 2008;412:469–475. doi: 10.1042/BJ20071614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar S, Hedges SB. A molecular timescale for vertebrate evolution. Nature. 1998;392:917–920. doi: 10.1038/31927. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li T, Yang Y, Canessa CM. Interaction of the aromatics Tyr-72/Trp-288 in the interface of the extracellular and transmembrane domains is essential for proton gating of acid-sensing ion channels. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:4689–4694. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M805302200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lingueglia E, de Weille JR, Bassilana F, Heurteaux C, Sakai H, Waldmann R, Lazdunski M. A modulatory subunit of acid sensing ion channels in brain and dorsal root ganglion cells. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:29778–29783. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.47.29778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Madeja M, Musshoff U, Speckmann EJ. Improvement and testing of a concentration-clamp system for oocytes of Xenopus laevis. J Neurosci Methods. 1995;63:211–213. doi: 10.1016/0165-0270(95)00094-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paukert M, Babini E, Pusch M, Gründer S. Identification of the Ca2+ blocking site of acid-sensing ion channel (ASIC) 1: implications for channel gating. J Gen Physiol. 2004a;124:383–394. doi: 10.1085/jgp.200308973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paukert M, Chen X, Polleichtner G, Schindelin H, Gründer S. Candidate amino acids involved in H+ gating of acid-sensing ion channel 1a. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:572–581. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M706811200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paukert M, Sidi S, Russell C, Siba M, Wilson SW, Nicolson T, Gründer S. A family of acid-sensing ion channels from the zebrafish: widespread expression in the central nervous system suggests a conserved role in neuronal communication. J Biol Chem. 2004b;279:18783–18791. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M401477200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pietra F. Docking and MD simulations of the interaction of the tarantula peptide psalmotoxin-1 with ASIC1a channels using a homology model. J Chem Inform Model. 2009;49:972–977. doi: 10.1021/ci800463h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qadri YJ, Berdiev BK, Song Y, Lippton HL, Fuller CM, Benos DJ. Psalmotoxin-1 docking to human acid-sensing ion channel-1. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:17625–17633. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.003913. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salinas M, Lazdunski M, Lingueglia E. Structural elements for the generation of sustained currents by the acid pain sensor ASIC3A. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:31851–31859. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.043984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Samways DS, Harkins AB, Egan TM. Native and recombinant ASIC1a receptors conduct negligible Ca2+ entry. Cell Calcium. 2009;45:319–325. doi: 10.1016/j.ceca.2008.12.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saugstad JA, Roberts JA, Dong J, Zeitouni S, Evans RJ. Analysis of the membrane topology of the acid-sensing ion channel 2a. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:55514–55519. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M411849200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sherwood T, Franke R, Conneely S, Joyner J, Arumugan P, Askwith C. Identification of protein domains that control proton and calcium sensitivity of ASIC1a. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:27899–27907. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.029009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith ES, Zhang X, Cadiou H, McNaughton PA. Proton binding sites involved in the activation of acid-sensing ion channel ASIC2a. Neurosci Lett. 2007;426:12–17. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2007.07.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sneddon LU. Evolution of nociception in vertebrates: comparative analysis of lower vertebrates. Brain Res. 2004;46:123–130. doi: 10.1016/j.brainresrev.2004.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Snow PJ, Plenderleith MB, Wright LL. Quantitative study of primary sensory neurone populations of three species of elasmobranch fish. J Comp Neurol. 1993;334:97–103. doi: 10.1002/cne.903340108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waldmann R, Bassilana F, de Weille J, Champigny G, Heurteaux C, Lazdunski M. Molecular cloning of a non-inactivating proton-gated Na+ channel specific for sensory neurons. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:20975–20978. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.34.20975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waldmann R, Lazdunski M. H+-gated cation channels: neuronal acid sensors in the NaC/DEG family of ion channels. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 1998;8:418–424. doi: 10.1016/s0959-4388(98)80070-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wemmie JA, Chen J, Askwith CC, Hruska-Hageman AM, Price MP, Nolan BC, Yoder PG, Lamani E, Hoshi T, Freeman JH, Jr, Welsh MJ. The acid-activated ion channel ASIC contributes to synaptic plasticity, learning, and memory. Neuron. 2002;34:463–477. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(02)00661-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiong ZG, Zhu XM, Chu XP, Minami M, Hey J, Wei WL, MacDonald JF, Wemmie JA, Price MP, Welsh MJ, Simon RP. Neuroprotection in ischemia: blocking calcium-permeable acid-sensing ion channels. Cell. 2004;118:687–698. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2004.08.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yagi J, Wenk HN, Naves LA, McCleskey EW. Sustained currents through ASIC3 ion channels at the modest pH changes that occur during myocardial ischemia. Circ Res. 2006;99:501–509. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000238388.79295.4c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zerangue N, Schwappach B, Jan YN, Jan LY. A new ER trafficking signal regulates the subunit stoichiometry of plasma membrane K(ATP) channels. Neuron. 1999;22:537–548. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80708-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ziemann AE, Schnizler MK, Albert GW, Severson MA, Howard MA, 3rd, Welsh MJ, Wemmie JA. Seizure termination by acidosis depends on ASIC1a. Nat Neurosci. 2008;11:816–822. doi: 10.1038/nn.2132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]