Abstract

Recombinant adeno-associated viral (rAAV) vectors have been widely used in pulmonary gene therapy research. In this study, we evaluated the transduction and expression efficiencies of several AAV serotypes and AAV2 capsid mutants with specific pulmonary targeting ligands in the mouse lung. The noninvasive intranasal delivery was compared with the traditional intratracheal lung delivery. The rAAV8 was the most efficient serotype at expressing α-1-antitrypsin (AAT) in the lung among all the tested serotypes and mutants. A dose of 1 × 1010 vg of rAAV8-CB-AAT transduced a high percentage of cells in the lung when delivered intratrachealy. The serum and the broncho-alveolar lavage fluid (BALF) levels of human AAT (hAAT) were about 6- and 2.5-fold higher, respectively, than those of rAAV5 group. Among the rAAV2 capsid mutants, the rAAV2 capsid mutants that display a peptide sequence from hAAT (“long serpin”) indicated a twofold increase in transgene expression. For most vectors, the serum hAAT levels achieved after intranasal delivery were 1/2 to 1/3 of those with the intratracheal method. Overall, rAAV8 was the most promising vector for the future application in gene therapy of pulmonary diseases such as AAT deficiency–related emphysema.

Introduction

Recombinant adeno-associated virus (rAAV)-based vectors have been developed for a variety of pulmonary disorders including α-1-antitrypsin (AAT) deficiency and cystic fibrosis.1,2,3,4 However, the paucity of AAV2 receptors on the apical surface of airway epithelium, the degradation of AAV in the cytoplasm, and the lack of integration of rAAV has limited its efficacy in clinical trials.5 One potential solution to these problems is the use of alternative AAV serotypes such as rAAV5, rAAV8, rAAV9, or AAV2 capsid mutants with specifically targeted ligands. These alternative capsids may bypass the binding and internalization barriers and achieve improved gene expression from a single administration. Recombinant AAV8 is emerging as a powerful gene therapy vector because of its ability to efficiently transduce many different tissues in vivo; however, studies demonstrating its affinity for lung gene transfer have not been performed. Interestingly, AAV8 shows high homology to rAAV9 which has been shown to transduce airways remarkably well.6 Both of theses serotypes have been implicated in binding the laminin receptor, which has been shown to be expressed in developing and adult lungs; thus, it is of great interest to determine whether rAAV8 also proves to be highly efficient at lung gene transfer.7,8,9

In an earlier work, we showed that two AAV2 capsid mutants with long and short serpin ligand insertions into the structural viral protein 1 at amino acid position 34 [VP1 (+34)] and VP2 (+1) of the capsid increased the transduction efficiency for the human lung cell line IB3 by about 80- and 25-fold, respectively.10 An other work has demonstrated that AAV2 capsid with an ApoE ligand in VP2 (+1) targeting the LDL receptor improved pancreatic islet transduction efficiency by 1.5-fold.4 Curiously, the LDL receptor has also been described to be present and upregulated in airway epithelial cells in response to viral infection.11,12 This makes the ApoE mutant an attractive candidate for airway gene transfer along with AAV2 mutants incorporating the peptide THALWHT and serpin ligands which have also been reported to have high binding affinity to airway epithelial cells.13 To accomplish this, we inserted the ApoE, long serpin (LS), short serpin (SS), and THALWHT ligands into AAV capsid VP1(+34), VP2(+1), and VP3(+588) sites, which have been studied previously.10 We examined the mouse lung transduction characteristics of these rAAV2 capsid mutants along with AAV5, AAV8, and AAV9 pseudotypes. All vectors contained identical genomes with the AAV2 inverted terminal repeats flanking a transcriptional unit composed of the chicken β-actin promoter cassette, the human AAT (hAAT) cDNA, and a poly A tail.5 The same vector genome was packaged into each different serotype or AAV2 capsid mutant so that any observed differences would be because of the capsid proteins themselves.

The purpose of our study was twofold: to compare (i) the lung transduction efficiency of various serotypes of AAV and AAV2 capsid mutants with targeting ligands, and (ii) the efficiency of gene expression between the traditional intratracheal injection method with that of the noninvasive intranasal method.

Results

Packaging of rAAV viruses

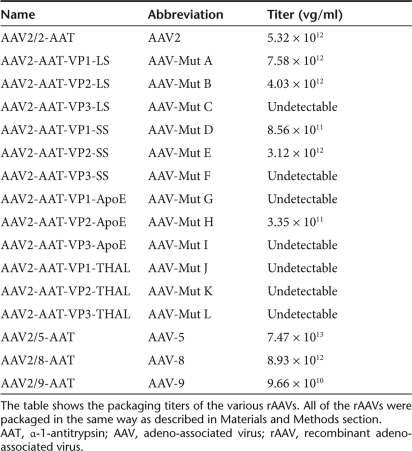

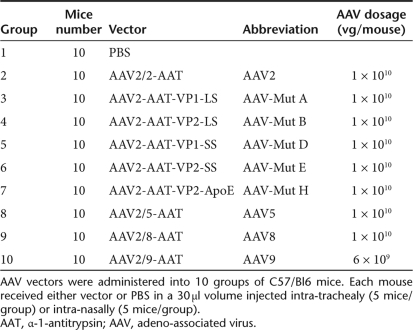

rAAV serotypes 2, 5, 8, 9, together with all AAV serotype 2 capsid mutants, were packaged under the same conditions. Among 12 mutants, only 5 mutants could be successfully packaged and purified. The detailed titer information is shown in Table 1. The titer of AAV mutants A, B, and E was close to that of AAV2. The titer decreased by about tenfold in AAV mutants D and H. AAV mutants C, F, G, I, J, K, and L could not be successfully packaged.

Table 1.

rAAV packaging titer

hAAT expression in serum after in vivo transduction of the murine lung

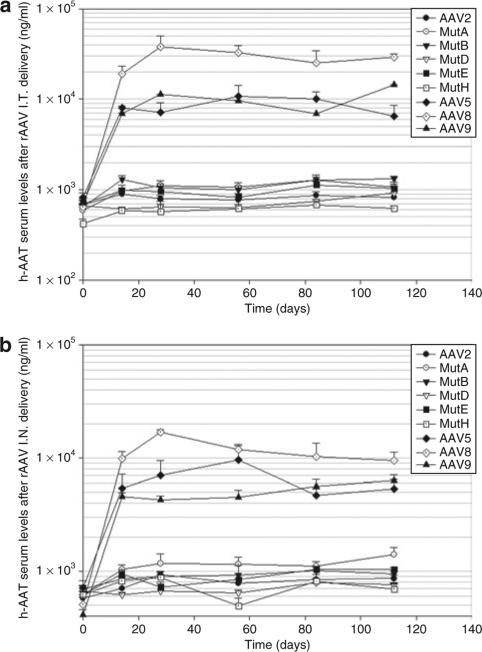

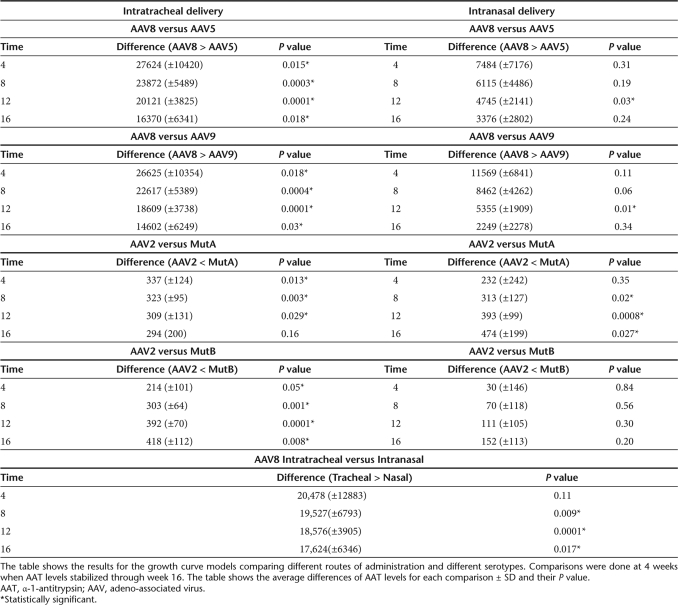

To determine the transduction and AAT expression efficiency of the various viral vectors in vivo, serum samples from mice receiving the vectors either intranasally or intratrachealy were analyzed for levels of hAAT. The serum hAAT enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) results are shown in Figure 1. The serum hAAT serum levels were stable for 4 months. Serum hAAT levels were highest in the AAV8 group, about five- to sevenfold higher than those of the AAV5 mice group. The serum levels were quite similar between the AAV5 and AAV9 groups although the AAV9 group mice were injected only with 60% of virus dose compared with the other groups (Figures 1a, b, 4, and Table 2). Among AAV2 capsid mutants, both AAV long-serpin Mutants A and B increased serum hAAT level twofold higher than rAAV2, and AAV mutants D and H showed reduced efficiency in lung transduction (Figure 1a, b and Table 2).

Figure 1.

Comparison of serum human α-1-antitrypsin (hAAT) levels among the different recombinant adeno-associated viruses (rAAVs) and delivery routes. The blood of C57B16 mice receiving various AAV serotypes or AAV2 capsid mutants intratrachealy or intranasally were collected every 4 weeks. The serum hAAT levels were assayed by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay. (a) rAAVs delivered intratrachealy, (b) rAAVs delivered intranasally. Refer to Table 2 for statistical analysis. Data are presented as group averages ± SEM (n = 5).

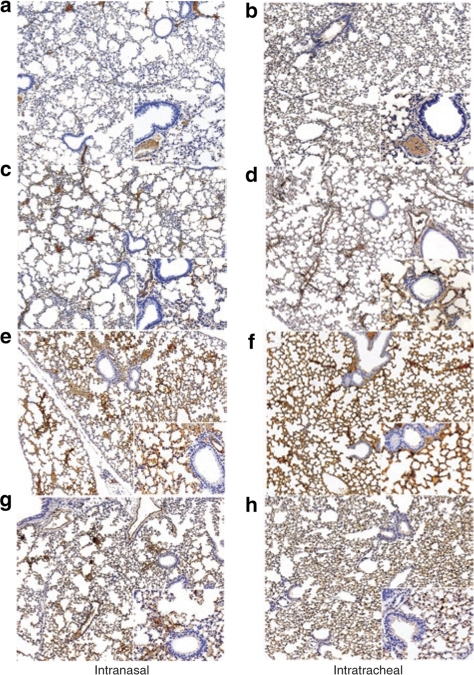

Figure 4.

Immunostaining for α-1-antitrypsin in the Lung. Representative lung histology sections images (×10 and ×20) of mice receiving 1 × 1010 vg of various rAAV serotypes via both routes of administration. (a) rAAV2-intranasal, (b) rAAV5-intranasal, (c) rAAV8-intranasal, (d) rAAV9-intranasal, (e) rAAV2-intratracheal, (f) rAAV5-intratracheal, (g) rAAV8-intratracheal, (h) rAAV9-intratracheal.

Table 2.

Statistical analysis of serum hAAT levels

rAAV lung transduction efficiency among various serotypes and AAV 2 capsid mutants

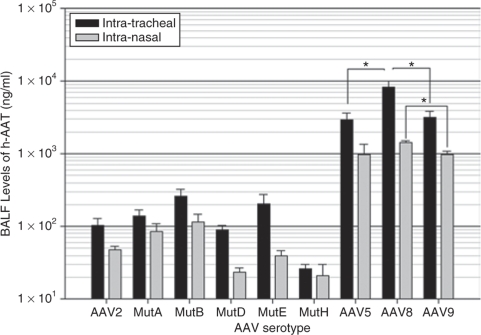

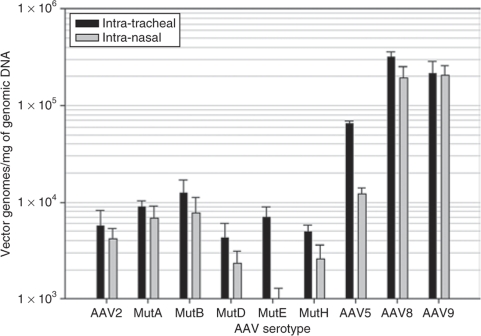

Intratracheal doses of 1 × 1010 vector genomes of rAAV8 showed the highest expression in the lung compartment as determined by hAAT levels in the broncho-alveolar lavage fluid (BALF) and increased transduction over rAAV5 as shown in the analysis of vector genomes (Figures 2 and 3). The BALF levels of hAAT were quite close among the AAV5, AAV8, and AAV9 pseudotypes after intranasal vector administration, whereas in the intratracheal groups, the hAAT levels of the rAAV8 group were 2.5-fold higher than those of AAV5 and AAV9 groups. AAV mutants A, B, and E increased the BALF levels of hAAT by two-, three-, and twofold, respectively, compared to that of AAV 2 (Figure 2). The lung tissue real-time PCR results showed that in the AAV8 group, the transduction efficiency was sixfold higher than that of AAV5 and 1.5-fold higher than that of rAAV9 (Figure 3) In addition, this is supported by the AAT immunostaining seen in the lungs (Figure 4).

Figure 2.

Human α-1-antitrypsin (hAAT) expression in broncho-alveolar lavage fluid (BALF). Four months after being injected with the rAAVs, animals were killed and their lungs were lavaged to measure hAAT levels present in the lung with an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay. Data are presented as group averages ± SEM (n = 5).

Figure 3.

Recombinant AAV genome copies in lung tissue. Four months after being injected with AAVs, animals were killed and lungs were collected and genomic DNA was extracted. Purified DNA was assayed by Taqman quantitative PCR for AAV copies. Data are presented as group averages ± SEM (n = 5).

Comparison of rAAV lung transduction efficiency between intratracheal and intranasal delivery

The lung transduction efficiency was compared after intratracheal versus intranasal delivery. For most of the rAAV vectors, the serum levels of hAAT after intranasal delivery were about 1/2 to 1/3 of those with intratracheal injection (Figures 1, 4, and Table 2). Among the AAV2 capsid mutants, AAV mutant B was best after intratracheal delivery (Figure 1a), whereas AAV mutant A was best after intranasal delivery (Figure 1b). The BALF hAAT levels of the intranasal group reached about 1/3 to 1/5 of the intratracheal group (Figure 2). The lung tissue real-time PCR results showed that the CB-AAT DNA transfer efficiency in the intranasal group was about 1/2 to 1/6 of the intratracheal group with the exception of AAV9, which had almost no difference between the two delivery methods (Figure 3).

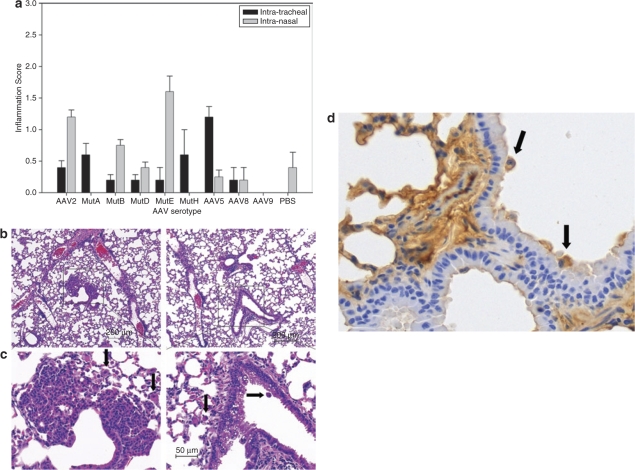

Safety of gene delivery

Bronchial epithelial hyperplasia was observed in two of five mice in the AAV mutant E intranasal delivery group (Figure 5a,b). Intraepithelial vesicles were also found in one mouse from this group (Figure 5c). Four of five mice in the AAV8 intratracheal delivery group demonstrated an increase in macrophage numbers (Figure 5d). No similar pathological changes were observed in negative control groups where phosphate buffered saline (PBS) was administrated intranasally or intratrachealy. The inflammation scores are shown (Figure 5a).

Figure 5.

Inflammatory changes after rAAV administration. (a) Pathological score of inflammation, 4 months after being injected with virus or PBS control, mice lungs were harvested and pathology scoring was done to evaluate the possible inflammation. (b) Hyperplasia in bronchial epithelial cells in mice receiving AAV mutant E mouse 4 months after intranasal delivery, the hyperplasia was found in the bronchial epithelial (×10). Macrophages are also observed in the region (arrows). (c) Vesicles in bronchial epithelial in AAV mutant E: mouse 4 months after intranasal delivery, the vesicles were found in the bronchial epithelial (×20), along with an occasional macrophage (arrows). (d) Macrophage infiltration and staining in rAAV8 transduced lung 4 months after intratracheal delivery. Data are presented as group averages (×40) (n = 5).

Discussion

The lung is an important target for gene delivery because it offers an easily accessible large surface area and an extensive capillary network.14 When considering AAT deficiency, the lung interstitium is thought to be the primary site of action for AAT to protect elastin and other extracellular matrix components. AAT levels in the interstitium are normally 2% of serum levels, as inactive AAT produced in the liver circulates in the blood and traffics into the lung components.15 Local AAV-mediated hAAT expression in alveolar cells may potentially circumvent this issue and produce a therapeutic effect without having to achieve high serum levels.16

rAAV has been used for gene transfer in the lung in preclinical and clinical trials.5,17 One strategy for improving rAAV lung transduction efficiency would be to use a different capsid serotype or capsid mutants with a greater affinity for airway epithelial cells. Using different AAV capsids to deliver the same DNA cassette, we compared the lung transduction efficiencies of the various AAV capsids. Previous results from several groups showed that AAV8 virus is capable of conferring significantly higher levels of hepatocyte,18 brain,19,20 and muscle transduction20 than other AAV serotypes. In view of these advantages, we tested the lung transduction efficiency of this serotype. Our results indicated that AAV8 was superior to AAV9, AAV5, AAV2, and AAV2 capsid mutants at expressing AAT in the murine lung. This result was confirmed by both vector-delivery methods and by hAAT levels in both serum and BALF. In addition, we confirmed earlier reports that show that lung transduction efficiency and subsequent AAT expression with AAV9 is superior to that of AAV5.21 However, Limberis et al.6 reports a peak 60-fold difference in AAT serum levels between AAV5 and AAV9. Our results are not as striking; however, the dose used in our study is tenfold lower and thus it is possible that there may be a threshold of cells readily transducible with rAAV5 at higher doses that may magnify this difference. Considering that only 6 × 109 vg (60% dosage of other AAV serotypes) was administrated in our experiment, the actual AAV9 transduction efficiency was an estimated to be twofold higher than that of AAV5. In contrast, the AAV2 capsid mutants demonstrated only very limited improvement of lung transduction with both delivery methods. These results suggest that newer AAV serotypes will be more promising than currently designed mutants for lung transduction.

After a single rAAV administration, the transgene expression was sustained for at least 4 months in both delivery methods. However, the hAAT in serum started to decrease after reaching a peak at 1 month after rAAV8 delivery. The rate decline was slow. Although the noninvasive intranasal delivery of rAAV is a very promising virus administration method which has been reported before, serum hAAT levels with intranasal delivery reached about 1/2 to 1/3 of those with the intratracheal method, and the BALF levels of hAAT in the intranasal groups were about 1/3 to 1/5 of intratracheal groups. Our data demonstrated that the noninvasive intranasal delivery method is fairly efficient for gene transfer, but less efficient than intratracheal delivery. It is possible that AAT levels in the serum may not necessarily reflect levels of lung transduction due to the use the ubiquitous chicken β-actin promoter and the relatively invasive nature of the intratracheal surgery. Certainly with a surgical delivery, some virus may accidentally end up transducing other tissues. Although this may explain some of the differences in serum levels between the two delivery routes, it is evident from BALF that AAT levels in the lung compartment are truly different between delivery routes.

In conclusion, we showed that AAV vectors packaged with the serotype 8 capsid resulted in the most robust AAT expression in the mouse lung among all AAV serotypes tested. The serum transgene expression levels from the noninvasive intranasal delivery were within the same order of magnitude as those seen with the standard intratracheal delivery method; however, intratracheal delivery resulted in significantly greater BALF expression of AAT among all serotypes tested. Furthermore, we showed even low doses (1010 vg) of rAAV8 via intratracheal delivery can successfully infect a high percentage of lung cells, resulting in long-term transgene expression. These results suggest that AAV8 might have future applications in gene therapy for pulmonary diseases.

Materials and Methods

Construction of rAAV plasmids. The CB-AAT vector was described previously.19 Briefly, it contains a CMV/chicken β-actin hybrid promoter, the hAAT cDNA, and poly A sequence. pDG-AAV2, pDG-AAV5, and pDG-AAV8 were used to pseudotype rAAV and have also been described previously.6 pDG-AAV9 was cloned from a plasmid containing the AAV9 capsid, which was a gift from the University of Pennsylvania.

pDG Vp1-LS, pDGVp2-LS, and pDG Vp3-LS were constructed by inserting 5′-aagtttaacaagccttttgtgttcctgatc-3′ long-serpin sequence between the Eag I site and the Mlu site of pDG-VP1(+34), pDG-VP2(+1), and pDG-VP3(+587), respectively.

pDG-Vp1-SS, pDG-Vp2-SS, and pDG Vp3-SS were constructed by inserting 5′-tttgtgttcctgatc-3′ small-serpin sequence into Eag I site and Mlu site of pDG-VP1(+34), pDG-VP2(+1), and pDG-VP3(+587), respectively.

pDG-Vp1-THALWHT, pDG-Vp2-THALWHT, and pDG-Vp3-THALWHT were constructed by inserting 5′-acccacgcattatggcataca-3′ THALWHT sequence between the Eag I site and the Mlu site of pDG-VP1(+34), pDG-VP2(+1), and pDG-VP3(+587), respectively.

pDG-Vp1-ApoE, pDG-Vp2-ApoE, and pDG-Vp3-ApoE were constructed by inserting 5′-ggcctgcgcaagctgcgcaagcgcctgctgcgcgactggctg aaggccttctacgacaaggtggccgaggacctggacgaggccttcggc-3′ ApoE ligand sequence between the Eag I site and the Mlu site of pDG-VP1(+34), pDG-VP2(+1), and the pDG-VP3(+587), respectively.

Virus production and purification. The methods used for viral production have been previously published.22 For the AAV2 vector and AAV2 Vp1 and Vp2 mutants, the lysate was loaded immediately onto a HiTrap Heparin (Pharmacia) column and eluted with 1× PBS-MK containing 0.5 mol/l NaCl. For rAAV5, rAAV8, rAAV9, and AAV2-Vp3 mutant, a HiTrap Q column (Amersham Pharmacia, Uppsala, Sweden) was used and fractions were eluted with 20 mmol/l Tris, 500 mmol/l NaCl (pH 8.5). The physical titers (in DNase-resistant particles) of the virus preparation were determined using DNA dot-blot hybridization. In a typical run of ten cell factories (2 × 109 cells), the packaging yields nearly 1 × 1013 particles.19

Pulmonary delivery of rAAV-AAT vectors.

Intranasal vector delivery: Eight- to ten-week-old C57/Bl6 mice obtained from Jackson Laboratories were used for all experiments. The mice were anesthetized by inhaled isoflurane administered with oxygen using a precision vaporizer (induced at 3%, maintained at 1.5–3%) in a closed ventilation chamber and subsequently moved to the rodent surgery area where they were placed in a supine position and instilled with a 30-µl aliquot of virus. Both nostrils were instilled with 15 µl of virus or PBS. The mice were allowed to inhale the bolus naturally. Subsequently, the mice were monitored for respiratory distress.

Intratracheal vector injection: The ventral cervical region was clipped, and scrubbed with alternating iodine and alcohol wipes for 2 minutes. Adequacy of surgical anesthesia was assessed by withdrawal reflex secondary to pinching of the skin between toes, as well as monitoring for a rapid and steady respiratory effort. A 1% topical gel lidocaine was applied to the skin of the mouse before the incision, followed by gentle blunt separation of muscle bundles. Intratracheal vector injections were performed with a butterfly catheter (25 G); placement of the needle within the lumen of the trachea was confirmed by movement of the fluid column (within the clear tubing) with respiratory effort. Injection volume was a 30-µl aliquot (1 × 1010 vg) of virus. The skin incision was then closed with a cyanoacrylate skin adhesive.

Ten groups of 10 mice received either intratracheal (n = 5) or intranasal (n = 5) injections in this portion of the study, as outlined in Table 3.

Table 3.

Animal experimental plan

Collection of blood samples: Approximately 50–75 µl of serum was obtained from 100–150 µl of blood before viral (or control) delivery in all mice. Blood samples were collected every 4 weeks by cutting into the tail vein under 1.5–3.5% isoflurane anesthesia. A final blood sample was collected at the time of killing via cardiac puncture in all mice under 3.5% isoflurane anesthesia.

Ten groups of 12 mice received either intratracheal (n = 5) or intranasal (n = 5) injections in this portion of the study, as outlined in Table 3.

Necropsy, tissue harvest, and BALF collection: Animals were euthanized by a 4% isoflurane induction followed by immediate cervical dislocation. Lung tissue samples were obtained from one mouse in each group at 4 weeks after virus injection. After a broncho-alveolar lavage (BAL) was performed on the lungs, they were instilled with 4% paraformaldehyde, then inflated and fixed with another 1 ml of 4% paraformaldehyde. The lungs were then taken out of the thoracic cavity; upper lobes of the lung together with other organs were stored in 4% paraformaldehyde and used to make hematoxylin and eosin slides and paraffin-embedded slides. The rest of lung was stored in liquid nitrogen for real-time PCR analysis.

BAL: BAL was harvested at the time of killing in all mice. BAL was performed by cannulating the trachea in situ with a 22-G needle, instilling three aliquots (1.0 ml) of sterile PBS solution, and collecting the fluid by gentle aspiration. The total lavage fluid recovered from all animals was measured and stored at ‐80 °C until assayed by ELISA.

ELISA analysis.

Determination of serum AAT: The levels of hAAT were measured in the serum samples by ELISA as previously described in detail.18

Immunostaining for hAAT in mouse tissues: Paraformaldehyde-fixed paraffin-embedded tissue sections (4 µm) were sequentially deparaffinized, rehydrated, and blocked for endogenous peroxidase activity. After antigen retrieval in target retrieval solution (DakoCytomation, Carpinteria, CA), slides were serum blocked and incubated with either rabbit anti-hAAT (1:100; Research Diagnostic Institute, Flanders, NJ) or normal rabbit immunoglobulin as a negative control. Antibody binding was detected using the EnVision+ HRP kit (DakoCytomation) and DAB+ (DakoCytomation). Slides were counterstained using hematoxylin (Vector Labs, Burlingame, CA). The tissue images were captured using a Zeiss Axioskop equipped with an Axiocam camera.19

For determination of inflammatory cells, the tissue was stained with hematoxylin and eosin and slides were semi-quantitatively scored in a blinded fashion using the following scale: 0 = none, 1 = focal or 1–3 small foci of inflammation, 2 = moderately sized single lesion or multifocal small lesions, 3 = multifocal moderate to severe lesions, 4 = multifocal degeneration or necrosis.

Genomic DNA extraction and quantitative PCR: Extraction of genomic DNA was performed using the Qiagen DNAeasy Tissue Kit, and DNA concentrations (1:25) were determined. One microgram of DNA was used in all quantitative PCRs according to a previously used protocol in our lab,23 and reaction conditions followed those recommended by the manufacturer to include 45 cycles of 95 °C for 15 seconds, 60 °C for 1 minute. Primer pairs were designed for the CMV enhancer/chicken B-actin promoter as described, and a standard curve was established using the pCBAT plasmid.23

Statistical analysis. Tests to examine differences in the serum levels of AAT between vector serotypes and mutants or delivery routes were based on growth curve models in which serum baseline levels and change over time were considered random effects and viral vector, delivery route, time and the interaction of these variables were fixed effects. Timepoints 4, 8, 12, and 16 were coded in separate models as 0 to contrast the difference between levels of AAT outcomes. An unstructured covariance structure was used. Goodness of fit was assessed using Akaike's information criterion. We assumed a linear trend model that provided a better fit than curvilinear models.

When comparing BAL levels, two-tailed Student's t-tests were used for determining statistical significance. Results are presented as group averages ± SEM and are considered significant when P < 0.05.

Acknowledgments

We thank Amy Poirier for her help with mice necropsies and Mark Potter of the University of Florida's Gene Therapy Center Vector core for providing the rAAV virus stocks. This work was supported by research grant from NIH.

REFERENCES

- Flotte TR. Recent developments in recombinant AAV-mediated gene therapy for lung diseases. Curr Gene Ther. 2005;5:361–366. doi: 10.2174/1566523054064986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flotte TR. Adeno-associated virus-based gene therapy for inherited disorders. Pediatr Res. 2005;58:1143–1147. doi: 10.1203/01.pdr.0000189226.03684.fe. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flotte TR. Gene therapy progress and prospects: recombinant adeno-associated virus (rAAV) vectors. Gene Ther. 2004;11:805–810. doi: 10.1038/sj.gt.3302233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loiler SA, Conlon TJ, Song S, Tang Q, Warrington KH, Agarwal A, et al. Targeting recombinant adeno-associated virus vectors to enhance gene transfer to pancreatic islets and liver. Gene Ther. 2003;10:1551–1558. doi: 10.1038/sj.gt.3302046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Virella-Lowell I, Zusman B, Foust K, Loiler S, Conlon T, Song S, et al. Enhancing rAAV vector expression in the lung. J Gene Med. 2005;7:842–850. doi: 10.1002/jgm.759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Limberis MP., and , Wilson JM. Adeno-associated virus serotype 9 vectors transduce murine alveolar and nasal epithelia and can be readministered. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:12993–12998. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0601433103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Virtanen I, Gullberg D, Rissanen J, Kivilaakso E, Kiviluoto T, Laitinen LA, et al. Laminin α1-chain shows a restricted distribution in epithelial basement membranes of fetal and adult human tissues. Exp Cell Res. 2000;257:298–309. doi: 10.1006/excr.2000.4883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Virtanen I, Laitinen A, Tani T, Paakko P, Laitinen LA, Burgeson RE, et al. Differential expression of laminins and their integrin receptors in developing and adult human lung. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 1996;15:184–196. doi: 10.1165/ajrcmb.15.2.8703474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akache B, Grimm D, Pandey K, Yant SR, Xu H., and , Kay MA. The 37/67-kilodalton laminin receptor is a receptor for adeno-associated virus serotypes 8, 2, 3, and 9. J Virol. 2006;80:9831–9836. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00878-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu P, Xiao W, Conlon T, Hughes J, Agbandje-McKenna M, Ferkol T, et al. Mutational analysis of the adeno-associated virus type 2 (AAV2) capsid gene and construction of AAV2 vectors with altered tropism. J Virol. 2000;74:8635–8647. doi: 10.1128/jvi.74.18.8635-8647.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suzuki M, Matsuse T., and , Isigatsubo Y. Gene therapy for lung diseases: development in the vector biology and novel concepts for gene therapy applications. Curr Mol Med. 2001;1:67–79. doi: 10.2174/1566524013364086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yuasa K, Sakamoto M, Miyagoe-Suzuki Y, Tanouchi A, Yamamoto H, Li J, et al. Adeno-associated virus vector-mediated gene transfer into dystrophin-deficient skeletal muscles evokes enhanced immune response against the transgene product. Gene Ther. 2002;9:1576–1588. doi: 10.1038/sj.gt.3301829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jost PJ, Harbottle RP, Knight A, Miller AD, Coutelle C., and , Schneider H. A novel peptide, THALWHT, for the targeting of human airway epithelia. FEBS Lett. 2001;489:263–269. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(00)02236-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Auricchio A, O'Connor E, Weiner D, Gao GP, Hildinger M, Wang L, et al. Noninvasive gene transfer to the lung for systemic delivery of therapeutic proteins. J Clin Invest. 2002;110:499–504. doi: 10.1172/JCI15780. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Louie SG, Sclar DA., and , Gill MA. Aralast: a new α1-protease inhibitor for treatment of α-antitrypsin deficiency. Ann Pharmacother. 2005;39:1861–1869. doi: 10.1345/aph.1E061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stecenko AA., and , Brigham KL. Gene therapy progress and prospects: α-1 antitrypsin. Gene Ther. 2003;10:95–99. doi: 10.1038/sj.gt.3301947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flotte TR, Zeitlin PL, Reynolds TC, Heald AE, Pedersen P, Beck S, et al. Phase I trial of intranasal and endobronchial administration of a recombinant adeno-associated virus serotype 2 (rAAV2)-CFTR vector in adult cystic fibrosis patients: a two-part clinical study. Hum Gene Ther. 2003;14:1079–1088. doi: 10.1089/104303403322124792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conlon TJ, Cossette T, Erger K, Choi YK, Clarke T, Scott-Jorgensen M, et al. Efficient hepatic delivery and expression from a recombinant adeno-associated virus 8 pseudotyped α1-antitrypsin vector. Mol Ther. 2005;12:867–875. doi: 10.1016/j.ymthe.2005.05.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howard DB, Powers K, Wang Y, Harvey BK. Tropism and toxicity of adeno-associated viral vector serotypes 1, 2, 5, 6, 7, 8, and 9 in rat neurons and glia in vitro. Virology. 2008;372:24–34. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2007.10.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cearley CN., and , Wolfe JH. Transduction characteristics of adeno-associated virus vectors expressing cap serotypes 7, 8, 9, and Rh10 in the mouse brain. Mol Ther. 2006;13:528–537. doi: 10.1016/j.ymthe.2005.11.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Z, Zhu T, Qiao C, Zhou L, Wang B, Zhang J, et al. Adeno-associated virus serotype 8 efficiently delivers genes to muscle and heart. Nat Biotechnol. 2005;23:321–328. doi: 10.1038/nbt1073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song S, Lu Y, Choi YK, Han Y, Tang Q, Zhao G, et al. DNA-dependent PK inhibits adeno-associated virus DNA integration. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:2112–2116. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0307833100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conway JE, Rhys CM, Zolotukhin I, Zolotukhin S, Muzyczka N, Hayward GS, et al. High-titer recombinant adeno-associated virus production utilizing a recombinant herpes simplex virus type I vector expressing AAV-2 Rep and Cap. Gene Ther. 1999;6:986–993. doi: 10.1038/sj.gt.3300937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]