Abstract

Electroporation (EP) has been used in basic research for the past 25 years to aid in the transfer of DNA into cells in vitro. EP in vivo enhances transfer of DNA vaccines and therapeutic plasmids to the skin, muscle, tumors, and other tissues resulting in high levels of expression, often with serological and clinical benefits. The recent interest in nonviral gene transfer as treatment options for a vast array of conditions has resulted in the refinement and optimization of EP technology. Current research has revealed that EP can be successfully used in many species, including humans. Clinical trials are currently under way. Herein, the transition of EP from basic science to clinical trials will be discussed.

Introduction

According to the Journal of Gene Medicine there are 246 clinical trials worldwide investigating naked plasmid DNA (www.wiley.co.uk/genmed/clinical), representing almost 20% of all vectors used in clinical trials and coming in third place behind adenovirus (24.8%) and retrovirus (22.3%) vectors. The development of novel nonviral vaccines and therapeutics for the prevention or treatment of disease has warranted the development of a delivery system that enables satisfactory expression of the desired molecule. Viral transfection systems have classically resulted in high expression levels of transgene products; however, this approach has immunological drawbacks1 and has led to nonviral vectors increasingly becoming the vehicle of choice. To boost efficacy of nonviral gene therapies several delivery methods have been under investigation such as lipid-mediated entry into cells,2 jet injection, gene gun delivery,3 and sonoporation.4 In this review we will focus on electroporation (EP) whereby cellular membranes are transiently destabilized by localized and controlled electric fields, facilitating the entry of foreign molecules into cells and tissues.5 Although the exact mechanism of cellular macromolecule entry is still under discussion, entry of small molecules such as anticancer drugs seems to occur by simple diffusion after the pulse, and larger molecules such as plasmid DNA are thought to enter through a multistep mechanism involving the interaction of the DNA molecule with the destabilized membrane during the pulse and then its passage across the membrane.6

The technique of EP has been used for over 25 years as a means of introducing macromolecules, including DNA, into cells in vitro,7 and is now widely used for transfection of plasmids into different tissues in vivo.8 More recently, EP has been used for the application of DNA vaccines and gene therapies. However, the transition of EP to the clinical setting has been slow to progress. Initially, the administration of bleomycin, an anticancer agent that induces DNA strand breaks, in combination with EP was the subject of numerous preclinical studies (reviewed in ref. 9) and tested in several humans with the first clinical trials started >15 years ago.10,11 Of note, pivotal studies performed around the same time demonstrated for the first time effective macromolecule in vivo EP in tumors,12 liver,13,14 and skeletal muscle.15

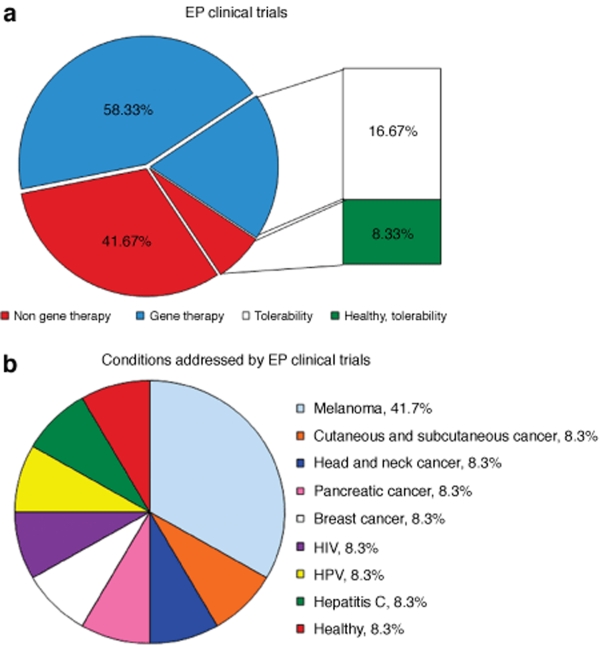

Although other physical delivery methods, such as ultrasound, have been used recently in small animal settings,16 successful small and large animal including nonhuman primate studies and human clinical trials using EP have demonstrated the effectiveness of this technique with plasmids. Overall, the technique of EP has been shown to be a versatile approach, as delivery has been accomplished across several species, different types of cells and tissues, EP conditions, macromolecule types, and most importantly, a large spectrum of applications. Several clinical trials are now investigating EP as a medical technology in humans, as shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Clinical trials using electroporation. (a) Seven gene therapy trials are listed on regulatory Web sites and investigate the benefits of EP; out of these, two are examining the tolerability of the technology. Five trials are investigating the combination of EP with nongene therapy approaches (anticancer drugs) for the treatment of cancer. One completed nongene therapy study by Merck tested the tolerability of EP in healthy adults. The number of trials is presented as a percentage. (b) Conditions addressed by EP clinical trials. Four trials examining the potential of EP in the treatment of melanoma. For all other conditions there is presently just one trial. Five of the trials (one head and neck cancer, one melanoma, one pancreatic cancer, one breast cancer, and one cutaneous/subcutaneous cancer) involve non-gene therapy approaches. The number of trials is presented as a percentage.

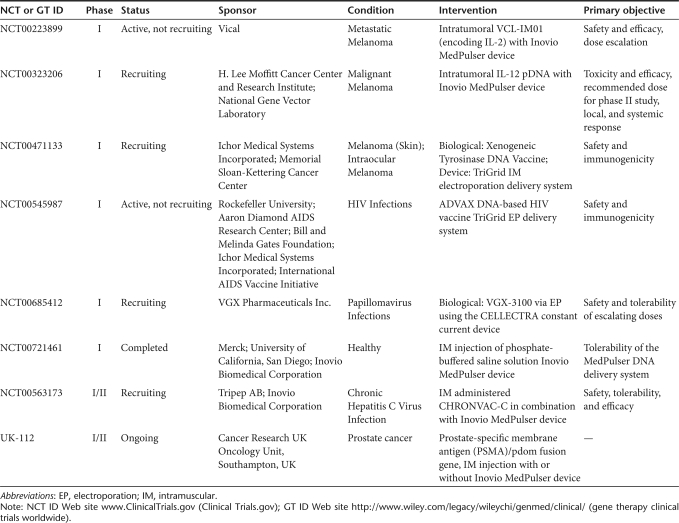

Various well-designed preclinical studies have been stepping stones in the progression to clinics (reviewed in refs 17,18,19,20). While diverse in scope and approaches, the ability to provide sound evidence and preliminary findings in laboratory or companion animals have proven crucial for the design of successful clinical trials. Furthermore, the development of naked DNA and EP technology in animals not only provides the basis for human studies but also lays the foundation for veterinary medical advances and bridges the gap between the two disciplines.21,22,23,24,25 The preclinical studies that have led to the clinical trials for various conditions shown in Table 1 will be discussed.

Table 1.

Clinical trial cases involving gene therapy and electroporation

Melanoma

Cytokines

The use of recombinant cytokines has provided a glimmer of hope in the fight against cancer; however, the frequent systemic administration of high doses often leads to dose-limiting side effects and toxicity.26 Therefore, new treatment strategies are in high demand. Interleukin (IL)-2 and IL-12 have shown promising antitumor effects in numerous preclinical studies by improving immune responses although the exact mechanism has yet to be elucidated.27,28,29

Previous studies have examined the treatment of mice bearing murine ovarian teratocarcinoma with IL plasmid DNA complexed with a cationic lipid.30 The administration of IL-2 pDNA increased the local concentration of the expressed cytokine and extended the length of expression from 24 hours for the recombinant form to up to 10 days for the plasmid DNA. Furthermore, the results showed that there was a significant antitumor effect as well as a significant increase in survival. Combining the delivery of bleomycin with IL-2 plasmid using EP resulted in long-term disease free survival in a mouse melanoma model.31

Nonclinical investigational new drug (IND) application-enabling studies in mice evaluated the effect of intratumoral murine IL-2 pDNA on local expression and systemic distribution of IL-2 transgene, as well as the inhibition of established tumor growth.32 Results showed that EP-assisted delivery produced the highest levels of IL-2 in the tumor (3–7 times higher than without EP). Local sustained levels of IL-2 within the tumor and relatively low, short-lived serum levels were detected. Tumor regression was noted with IL-2 plus EP compared to IL-2 alone. Further studies testing the safety of repeated s.c. administrations of VCL-IM01 [human IL-2 pDNA (VCL-1102) in PBS] with EP were carried out in rats. There were no mortalities, no evidence of drug-related toxicity, no erythema associated with injection or EP, and overall treatment was well tolerated. These preclinical findings, in combination with previously published safety study results for VCL-1102 pDNA,33 led to the ongoing clinical testing of VCL-IM01 with EP in a phase I clinical trial (ClinicalTrials.gov ID NCT00223899). Thirty patients with metastatic melanoma are scheduled to receive VCL-IM01 at various dose concentrations intratumorally followed by EP using the Medpulser EPT System. The primary endpoint of the study is safety, with secondary outcomes including response rate, assessment of injected tumors for induration, inflammation, and erythema, and serum levels of IL-2. Tumor burden, response rate, and disease progression will also be assessed.

The success of the administration of plasmid IL-2 led to studies examining the potential of IL-12 in combination with EP in murine melanoma tumor models. A local antitumor effect with reduced systemic cytokine levels was observed.34 The combination of EP with either murine IL-2 or IL-12 plasmids resulted in a significant growth delay of ~5–15 days compared to control plasmid plus EP and the respective naked cytokine plasmids without EP.34 Further studies demonstrated that intratumoral injection of plasmid IL-12 with EP of mice with B16.F10 melanoma tumors resulted in 80% being tumor free for >100 days and resistant to challenge with B16 cells.35,36 To facilitate the translation of this approach to the clinic, toxicity was evaluated in the B16.F10 melanoma model. Expression levels of IL-12 were significantly increased when delivered with EP in addition to complete regression of tumors, when plasmid IL-12 was delivered with EP, the findings showed minimal to no toxicity.37

The phase I trial of intratumoral pIL-12 EP in patients with Stage IIIB/c or IV malignant melanoma (n = 24) (ClinicalTrials.gov ID NCT00323206) was designed to determine safety and tolerability, the correct dose of this type of treatment, and also its effectiveness in treating melanoma. EP was performed using the Medpulser EPT System. Primary outcome measures included toxicity profile, maximum-tolerated dose, recommended dose for a phase II study, local and systemic response, and local and systemic expression of IL-12 and IFN-γ. An increase in IL-12 and IFN-γ was observed locally within treated tumors but no increase in serum levels was seen. Biopsies of treated lesions revealed marked necrosis and lymphocytic infiltration. In addition, 8 of the 24 patients were observed to have stable disease and two of them had a complete response of all lesions, treated and untreated. This first human trial investigated IL-12 gene transfer utilizing in vivo DNA EP in metastatic melanoma and showed that it is safe, effective, reproducible, and titratable.38

The preclinical findings indicate that the application of cytokines alone can improve efficacy but the addition of EP can further enhance their therapeutic potential. The clinical trials will hopefully demonstrate that the combination of EP with cytokine-expressing plasmids will be effective in treating humans with melanoma.

Xenogeneic tyrosinase DNA vaccine

The tyrosinase family proteins are well-characterized differentiation antigens recognized by antibodies and T cells of patients with melanoma. Preclinical mouse studies revealed that xenogeneic DNA vaccination with genes encoding tyrosinase family members can induce antibody and cytotoxic T cell responses resulting in tumor rejection.39,40 The addition of EP for administration of plasmid encoding, a novel construct of autologous, melanocyte antigen tyrosinase–related protein-2, resulted in very high numbers of CD8+ T cells and significant delay in tumor growth after challenge in mice.41 These results led to the examination of the long-term survival of dogs with advanced spontaneous malignant melanoma after DNA vaccination with xenogeneic human tyrosinase in a single-arm phase I trial.42,43 Nine dogs were injected with human tyrosinase plasmid DNA intramuscularly (IM) via a different methodology, using Biojector2000, a needle-free delivery device. The trial demonstrated that the vaccination was safe and efficacious. The median survival time for all vaccinated dogs was just over 1 year compared to dogs treated using historical controls with conventional therapies that survived 1–5 months. Antibody responses were documented in a follow-up publication, with three out of the nine dogs showing a response.44

Based on these encouraging results, a phase I trial of mouse and human TYR DNA vaccines in 18 stage-III/IV melanoma patients was conducted to assess safety and immunogenicity using the Biojector2000.45 This needle-free injection system was well tolerated and T cell responses were detected in seven patients. Median survival time had not been determined after >42 months follow-up, at the time of study publication. The results of this study and the advent of efficacious EP devices have led to the larger evaluation of various DNA delivery methods including a phase I clinical trial investigating the safety and immunogenicity of xenogeneic tyrosinase DNA vaccine, administered IM with EP to patients with stage IIB, IIC, III, or IV melanoma (ClinicalTrials.gov ID NCT00471133). Primary outcome measures include evaluation of the safety and feasibility of EP-mediated IM delivery and assessment of the magnitude and frequency of tyrosinase-specific immunologic responses in the immunized patients. Patients with measurable tumors will be assessed for evidence of antitumor responses following immunization. The ability of xenogeneic tyrosinase DNA vaccine in combination with EP will hopefully lead to even greater increases in immune responses, antitumor effects, and increased longevity compared to the vaccine alone.

HIV Infections

Since the identification of the causative agent of acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS) in the early 1980s progress toward an effective vaccine has been hindered by the pathogenesis of the virus itself. Although current treatment with antiretroviral drugs can turn this fatal disease into a manageable chronic condition, the need for a novel therapeutic strategy is without question to control the AIDS pandemic.

Attempts at developing an effective AIDS vaccine led to the recent STEP AIDS vaccine study by Merck. The STEP HIV vaccine trial used a modified recombinant adenovirus serotype 5 (rAd5) as a vaccine vector along with three synthetically produced HIV genes (gag, pol, and nef).46 The phase I and phase II human clinical trials were suspended based on an interim data review that concluded that the vaccine could not be shown to prevent HIV infection or reduce the amount of virus in those who became infected (ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT00486408 and NCT00413725). Further analysis of the study suggested that those participants who received the vaccine were more susceptible to HIV infection, especially those who had higher levels of preexisting immunity (antibodies) to Ad5 due to prior natural exposure to that particular type of cold virus. (http://www3.niaid.nih.gov/news/QA/step_qa.htm). Nevertheless, the lessons learned from these trials are invaluable, and establish the basis for the next generation of vaccines.

One method to overcome the issue of preexisting immunity, which was problematic in the STEP trial, is the use of DNA vaccines in place of their viral counterparts. Numerous studies and clinical trials are examining the potential of DNA vaccines as HIV therapeutics. In a phase I trial, the safety and immunogenicity of a multigene, polyvalent HIV-1 DNA plasmid prime/Env protein–boost vaccine formulation was evaluated in healthy volunteers (ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT00061243) demonstrating T cell responses as well as high-titer serum antibody responses.47 The combination of a DNA vaccine with cytokines indicated that memory-immune responses in SIV-infected macaques were enhanced.48

Further studies have demonstrated that the route and dose of DNA vaccine is critical for optimal immune responses.49 Results of a phase I trial demonstrated that vaccination with a DNA prime formulation followed by a protein boost for seronegative adults induced HIV-1-specific T cells and anti-Env antibodies capable of neutralizing cross-clade viral isolates. Additional studies examined vaccination with a low dose of DNA administered intradermic (ID) compared with low or high dose of DNA administered IM. Each group subsequently received one or two doses of the gp120 protein–boost vaccine IM. The high dose, administered IM, resulted in a greater response than ID after DNA vaccination. However, after the second protein boost, the magnitude of T cell responses in the ID group was indistinguishable from those in the other two groups. The need for a prime/boost strategy in this case was important for a quality immune response. In another phase I trial, patients who received four IM immunizations with a DNA vaccine did not differ statistically in rate of response from placebo controls.50 It would seem, therefore, that the route of administration and the dose are both extremely important for success. Nevertheless, other studies have shown that the efficacy of the prime/boost vaccination regime by needle injection can be improved and simplified by the use of EP.

Several studies have examined the potential of EP in the administration of a HIV vaccine. In mice, in vivo EP amplified cellular and humoral immune responses to a HIV type 1 Env DNA vaccine, enabled a tenfold reduction in vaccine dose, and resulted in an increased recruitment of inflammatory cells.51 Nonhuman primate studies examined four different administration strategies, namely, DNA by IM injection, DNA with plasmid-encoded IL-12 by IM injection, DNA by IM injection with in vivo EP, and DNA with IL-12 by IM EP.52 Each group was immunized three times with optimized HIV gag and env constructs. The combined approach of cytokine adjuvant and EP resulted in dramatically higher cellular as well as humoral responses and a tenfold increase in antigen-specific IFN-γ(+) cells compared to IM DNA immunization. Further studies supporting these findings demonstrated that an optimized HIV gag expression plasmid administered by EP resulted in an expansion of antigen-specific CD4+ and CD8+ T cells of both central and effector memory phenotype in SIV-infected animals.53 These studies all utilized the IM route of administration, but ID EP administration of an HIV DNA vaccine in nonhuman primates has also been shown to be effective at inducing high-humoral and cellular-immune responses compared to ID injection alone.54 Other studies show that EP of low-dose HIV env elicited Th1 cytokines and antienvelope antibodies. The subsequent boosting of DNA-primed animals with gp120 proteins administered with either QS-21, or the orally administered immunomodulator, Talabostat, has been shown to augment cellular immune responses.55,56,57

The safety and immunogenicity of a plasmid HIV vaccine, ADVAX env/gag + ADVAX pol/nef-tat (ADVAX), is being examined in an ongoing phase I trial in HIV uninfected adults (ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT00249106) and in combination with EP as a potential protective vaccine against HIV (ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT00545987). The dual-promoter multigenic DNA vaccine capable of high-level expression of two independent transgenes was designed and constructed.58 HIV-1 gag, pol, env, nef, and tat from a primary subtype C/B′ CCR5-tropic HIV-1 were codon optimized and then modified to remove known functional activity, and assembled using an overlapping polymerase chain reaction into two plasmids, namely, ADVAX-I (containing env and gag) and ADVAX-II (containing pol and nef-tat). In this randomized, placebo-controlled, dose-escalating, double-blinded phase I study local and systemic reactogenicity signs and symptoms as well as adverse effects were investigated after the administration of one to three doses of ADVAX. This has led to the current study that is recruiting participants to test the safety and immunogenicity of an IM injection of two doses of ADVAX using the EP TriGrid Delivery System (Ichor Medical Systems, ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT00545987). Of note, this trial is investigating the prophylactic potential of a DNA vaccine administered by EP and is part of a broader research effort to determine whether changes in the way vaccines are administered can make them more effective.

Human Papillomavirus Infections

Human papillomavirus (HPV) infection is the major cause of cervical cancer. Although the recently FDA-approved HPV vaccine Gardasil has been shown to prevent infection, it does not provide treatment for individuals already infected. Therefore, the development of a therapeutic HPV vaccine is of great importance. The HPV genome encodes two HPV late genes, L1 and L2, which form the viral capsid. Early viral proteins support viral genome replication, two of which (E6 and E7) are important for HPV-associated malignant transformation. Prophylactic vaccines target the HPV capsid protein L1, thereby preventing infection, whereas therapeutic HPV vaccines target the E6 and E7 proteins.59

Studies have demonstrated that DNA vaccines can induce CTL responses and antitumor activity. Administration of a codon-optimized HPV-16 E6 DNA vaccine (pNGVL4a-E6/opt) resulted in significantly enhanced E6-specific CD8+ T cell immune responses in mice. Protective and therapeutic antitumor effects were also noted against challenge.60 Other groups report that a DNA vaccine–encoding calreticulin (CRT) linked to HPV-16 E7 generated potent E7-specific CD8+ T cell-immune responses and antitumor effects against an E7-expressing tumor.61 Furthermore, development of a similar DNA vaccine encoding CRT linked to E6 (CRT/E6) generated significant T cell responses and could protect mice from challenge.62

An earlier study utilized the technique of EP for the introduction of plasmids that express antisense RNA of the E6 and E7 genes on the growth of HPV positive human cancer cell lines resulting in slowed growth.63 Several other studies are examining the potential of EP for administration of dendritic cell–based tumor vaccines.64,65

Strong cellular immune responses can be induced in both mice and nonhuman primates following the administration with EP of a novel HPV18 DNA vaccine encoding an E6/E7 fusion consensus protein.66 These finding have lead to a phase I study using a DNA vaccine, VGX-3100, which includes plasmids targeting E6 and E7 proteins of both HPV subtypes 16 and 18 that will be delivered using the constant current CELLECTRA EP device following IM injection (ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT00685412). This study will determine the dose, safety, and tolerability as well as the humoral and cellular immune responses in adult female subjects' postsurgical or ablative treatment of grade 2 or 3 cervical intraepithelial neoplasia.

Hepatitis C

Hepatitis C is a blood-borne infectious disease that is caused by hepatitis C virus (HCV) infecting hepatocytes with almost one third of infected individuals progressing to liver disease. No vaccine against hepatitis C is available and current treatment strategies are insufficiently effective, poorly tolerated, and expensive. A DNA vaccine encoding cell-surface HCV-envelope 2 (E2) glycoprotein was shown to stimulate strong immune responses in mice and rhesus macaques. Immunization of chimpanzees did not result in protection from challenge but prevented progression to a chronic state.67 Therefore, the development of novel vaccines and delivery methods will be important in treating this highly prevalent infection.

To this end, a synthetic nonstructural (NS) NS3/4A-based DNA vaccine was generated in which the codon usage was optimized for human cells.68 In a study examining the in vivo EP of the HCV NS3/4A DNA vaccine revealed increased and prolonged expression of protein levels as well as an increased infiltration of CD3+ T cells at the site of injection, likely contributing to an observed enhancement of CD4+ T cells, CD8+ T cells, and IFN-γ production. The increase in CD8+ T cells resulted in the elimination of HCV NS3/4A-expressing liver cells in transiently transgenic mice.69 In a separate study, a construct encoding a HCV genotype 1a/1b consensus immunogen of proteins NS3/4A was used to immunize mice followed by IM EP. Results show that strong anti-NS3/4A T cell responses in mice as well as in rhesus macaques were induced.70 In mice and nonhuman primates, EP of a DNA vaccine encoding an optimized version of the NS region of HCV (from NS3 to NS5B) induced strong and long-lasting CD4+ and CD8+ cellular immunity compared to naked DNA injection alone.71 Furthermore, in the same study, vaccination with EP produced a higher CD4+ T cell response than an adenovirus 6-based viral vector encoding the same antigen.

Currently, there is one clinical trial evaluating the administration of the DNA vaccine CHRONVAC-C by IM injection with EP using the Inovio Elgen system. CHRONVAC is a therapeutic vaccine given to individuals already infected with HCV. Early results indicate that the first two patients given the intermediate dose of CHRONVAC-C with EP had reduced viral loads (by 87 and 98%) and that there may be a dose-dependent correlation between T cell responses generated and reduction in hepatitis C viral load. No severe adverse effects have been noted (http://tripep.se/english/news/press_releases/?id=2008063020130). These findings are extremely promising for the continued development of DNA vaccines and the use of EP for treatment of hepatitis C.

Prostate Cancer

Prostate cancer is one of the most common types of cancer in men. Treatment options for prostate cancer are primarily surgery and radiation therapy; however, statistical data point that 186,320 men will be diagnosed with cancer of the prostate and 28,660 men will die due to this cancer in 2008 (http://seer.cancer.gov/statfacts/html/prost.html). Prostate-specific antigen (PSA) is a serine protease secreted at high levels by prostate cancer cells making it a potential target for immunotherapeutic approaches.

DNA-based vaccines have been shown to induce CTLs specific for prostate antigens. A phase I clinical trial previously revealed that vaccination with a PSA DNA vaccine in patients with prostate cancer is safe and can induce cellular and humoral immune responses against PSA protein.72,73 The technique of EP has been investigated as a more effective way for delivering PSA DNA vaccines.74,75 In mice, the ID EP of a prostate cancer DNA vaccine encoding PSA resulted in 100- to 1,000-fold increased gene expression and higher levels of PSA-specific T cells, compared to DNA delivery alone.75 Further investigations demonstrated that ID DNA vaccination with small amounts of DNA followed by two sets of electrical pulses of different length and voltage, effectively induced PSA-specific T cells.74

Currently, there is one clinical trial examining the ability of EP to enhance the effectiveness of vaccination against prostate cancer. Interim data from the clinical study suggest that the treatment is safe and well tolerated and that higher levels of antibody as well as CD4+ and CD8+ T cells were detected in patients treated with EP. Tolerability of the procedure was also documented in this trial. Patients were given a choice between simple IM vaccination and repeat EP—all patients chose repeat EP. The heightened immune responses in patients treated using EP further validate the efficacy of this DNA vaccine delivery method (http://www.medicalnewstoday.com/articles/102919.php).

Preclinical Applications of Ep For Future Clinical Use

There are several preclinical studies that have investigated EP but have not yet made it to the clinical trial stage. The injection of plasmid DNA in the retina with and without EP in vivo and in vitro was carried out in rodents. Appropriate expression patterns and long-term expression of the constructs carrying retinal cell type–specific promoters was observed.76,77 The retina is an interesting target system for the study of neural development and treatment of disease and is being pursued for transition to humans. Another promising area is that of inflammatory disease, in particular rheumatoid arthritis, where EP of plasmids encoding for human tumor necrosis factor alpha–soluble receptor I variants (hTNFR-Is) were shown to exert protective effects, with decreased joint destruction in the ankles.78

Other studies are investigating the use of EP for vaccination against influenza virus. An optimized H5N1 hemagglutinin (HA)-based DNA vaccine administered by IM EP was shown to elicit antibodies that neutralized a panel of virions from various H5N1 viruses and protected the immunized mice from H5N1 virus challenges.79 In a separate study mice, ferrets and nonhuman primates were immunized by combining several consensus influenza antigens with in vivo EP inducing both protective cellular and humoral immune responses. Furthermore, in a ferret-challenge model, vaccination with EP protected against morbidity and mortality.80 The continued development and transition to clinical trial status of such research will be important for the expansion and success of DNA vaccination with EP.

Summary

This review demonstrates the wide-reaching ability of DNA delivery with EP to treat or prevent numerous diseases. The continued research into this approach will enable this technology to be applied to many more conditions that are lacking effective therapies. Recently, the technique of EP itself, independent of DNA delivery, has been shown to recruit and trigger cells involved in antigen presentation and immune response.81 Therefore, EP has adjuvant-like properties that will enhance the continued development and success of DNA vaccines and immunotherapeutics. The results from the current phase I studies will provide important safety information as well as preliminary efficacy data in humans for EP-assisted delivery of plasmid DNA enabling the transition to phase II and III studies and ultimately for use in clinical practice. Interim data from some of the current clinical trials as discussed suggest that the technique of EP for the administration of DNA vaccines and immunotherapies is a powerful tool for combating diseases. Not only does EP enhance humoral and cellular immune responses, but it also decreases injection volume, minimizes the number of applications, and prolongs the vaccine or therapeutic effects. The route of administration will also likely play a large role in the transition of EP to humans. Although most preclinical studies to date have centered on IM applications, the ID route of application will likely be more readily accepted by the majority of the population. Together with the fact that skin administration has been the status quo for vaccinations, the ease of accessibility and the reduced pain level compared to IM injections may increase public acceptance. Evolution of the EP device itself from a lab-like instrument to an esthetically pleasing, biosafe medical tool that is easily operated and portable with low-cost disposables will also be necessary for its future widespread use. Therefore, the further development and application of EP will be of significant importance in administration of vaccines to the public, in terms of compliance and economical feasibility.

The most current developments in the field of EP are targeted toward therapeutic applications. However, the one ongoing prophylactic vaccine study and many preclinical studies targeted to prophylaxis suggest that using EP technology for prophylactic applications may be feasible, depending on application, safety, and tolerability data. Overall, the further understanding and development of EP will play an important role in advancing the use of DNA vaccinations as well as the administration of DNA-based immunotherapies or other therapeutic approaches.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by VGX Pharmaceuticals, Inc. A.M.B.-B. and R.D.-A are employees of VGX Pharmaceuticals, Inc. and own stock and/or stock options in this company; R.D.-A is an inventor on patents and patent applications assigned or licensed to VGX Pharmaceuticals, Inc. R.H. owns stock or stock options in Inovio Biomedical Corporation and has ownership interest in RMR Technologies, LLC. R.H. is an inventor on patents and patent applications licensed to Inovio biomedical Corporation and RMR Technologies, LLC. No writing assistance was utilized in the production of this manuscript.

REFERENCES

- Hartman ZC, Appledorn DM., and , Amalfitano A. Adenovirus vector induced innate immune responses: impact upon efficacy and toxicity in gene therapy and vaccine applications. Virus Res. 2008;132:1–14. doi: 10.1016/j.virusres.2007.10.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ewert KK, Ahmad A, Bouxsein NF, Evans HM., and , Safinya CR. Non-viral gene delivery with cationic liposome-DNA complexes. Methods Mol Biol. 2008;433:159–175. doi: 10.1007/978-1-59745-237-3_10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuller DH, Loudon P., and , Schmaljohn C. Preclinical and clinical progress of particle-mediated DNA vaccines for infectious diseases. Methods. 2006;40:86–97. doi: 10.1016/j.ymeth.2006.05.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohta S, Suzuki K, Ogino Y, Miyagawa S, Murashima A, Matsumaru D, et al. Gene transduction by sonoporation. Dev Growth Differ. 2008;50:517–520. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-169X.2008.01026.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rols MP. Mechanism by which electroporation mediates DNA migration and entry into cells and targeted tissues. Methods Mol Biol. 2008;423:19–33. doi: 10.1007/978-1-59745-194-9_2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Escoffre JM, Portet T, Wasungu L, Teissie J, Dean D., and , Rols MP. What is (still not) known of the mechanism by which electroporation mediates gene transfer and expression in cells and tissues. Mol Biotechnol. 2009;41:286–295. doi: 10.1007/s12033-008-9121-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neumann E, Schaefer-Ridder M, Wang Y., and , Hofschneider PH. Gene transfer into mouse lyoma cells by electroporation in high electric fields. EMBO J. 1982;1:841–845. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1982.tb01257.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cemazar M., and , Sersa G. Electrotransfer of therapeutic molecules into tissues. Curr Opin Mol Ther. 2007;9:554–562. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gothelf A, Mir LM., and , Gehl J. Electrochemotherapy: results of cancer treatment using enhanced delivery of bleomycin by electroporation. Cancer Treat Rev. 2003;29:371–387. doi: 10.1016/s0305-7372(03)00073-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mir LM, Belehradek M, Domenge C, Orlowski S, Poddevin B, Belehradek J, Jr, et al. [Electrochemotherapy, a new antitumor treatment: first clinical trial] C R Acad Sci III. 1991;313:613–618. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heller R, Jaroszeski MJ, Glass LF, Messina JL, Rapaport DP, DeConti RC, et al. Phase I/II trial for the treatment of cutaneous and subcutaneous tumors using electrochemotherapy. Cancer. 1996;77:964–971. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0142(19960301)77:5<964::aid-cncr24>3.0.co;2-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niu G, Heller R, Catlett-Falcone R, Coppola D, Jaroszeski M, Dalton W, et al. Gene therapy with dominant-negative Stat3 suppresses growth of the murine melanoma B16 tumor in vivo. Cancer Res. 1999;59:5059–5063. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heller R, Jaroszeski M, Atkin A, Moradpour D, Gilbert R, Wands J, et al. In vivo gene electroinjection and expression in rat liver. FEBS Lett. 1996;389:225–228. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(96)00590-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suzuki T, Shin BC, Fujikura K, Matsuzaki T., and , Takata K. Direct gene transfer into rat liver cells by in vivo electroporation. FEBS Lett. 1998;425:436–440. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(98)00284-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aihara H., and , Miyazaki J. Gene transfer into muscle by electroporation in vivo. Nat Biotechnol. 1998;16:867–870. doi: 10.1038/nbt0998-867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kusumanto YH, Mulder NH, Dam WA, Losen MH, Meijer C., and , Hospers GA. Improvement of in vivo transfer of plasmid dna in muscle: comparison of electroporation versus ultrasound. Drug Deliv. 2007;14:273–277. doi: 10.1080/10717540601098807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trollet C, Scherman D., and , Bigey P. Delivery of DNA into muscle for treating systemic diseases: advantages and challenges. Methods Mol Biol. 2008;423:199–214. doi: 10.1007/978-1-59745-194-9_14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heller LC., and , Heller R. In vivo electroporation for gene therapy. Hum Gene Ther. 2006;17:890–897. doi: 10.1089/hum.2006.17.890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luxembourg A, Evans CF., and , Hannaman D. Electroporation-based DNA immunisation: translation to the clinic. Expert Opin Biol Ther. 2007;7:1647–1664. doi: 10.1517/14712598.7.11.1647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prud'homme GJ, Glinka Y, Khan AS., and , Draghia-Akli R. Electroporation-enhanced nonviral gene transfer for the prevention or treatment of immunological, endocrine and neoplastic diseases. Curr Gene Ther. 2006;6:243–273. doi: 10.2174/156652306776359504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dhama K, Mahendran M, Gupta PK., and , Rai A. DNA vaccines and their applications in veterinary practice: current perspectives. Vet Res Commun. 2008;32:341–356. doi: 10.1007/s11259-008-9040-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Person R, Bodles-Brakhop AM, Pope MA, Brown PA, Khan AS., and , Draghia-Akli R. Growth hormone-releasing hormone plasmid treatment by electroporation decreases offspring mortality over three pregnancies. Mol Ther. 2008;16:1891–1897. doi: 10.1038/mt.2008.178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown PA, Bodles-Brakhop A., and , Draghia-Akli R. Plasmid growth hormone releasing hormone therapy in healthy and laminitis-afflicted horses-evaluation and pilot study. J Gene Med. 2008;10:564–574. doi: 10.1002/jgm.1170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown PA, Bodles-Brakhop AM., and , Draghia-Akli R. Effects of plasmid growth hormone releasing hormone treatment during heat stress. DNA Cell Biol. 2008;27:629–635. doi: 10.1089/dna.2008.0758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bodles-Brakhop AM, Brown PA, Pope MA., and , Draghia-Akli R. Double-blinded, placebo-controlled plasmid GHRH trial for cancer-associated anemia in dogs. Mol Ther. 2008;16:862–870. doi: 10.1038/mt.2008.31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chada S, Ramesh R., and , Mhashilkar AM. Cytokine- and chemokine-based gene therapy for cancer. Curr Opin Mol Ther. 2003;5:463–474. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lotze MT, Shurin M, Esche C, Tahara H, Storkus W, Kirkwood JM, et al. Interleukin-2: developing additional cytokine gene therapies using fibroblasts or dendritic cells to enhance tumor immunity Cancer J Sci Am 20006S61–S66.Suppl 1 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shimizu K, Fields RC, Redman BG, Giedlin M., and , Mule JJ.Potentiation of immunologic responsiveness to dendritic cell-based tumor vaccines by recombinant interleukin-2 Cancer J Sci Am 20006S67–S75.Suppl 1 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weiss JM, Subleski JJ, Wigginton JM., and , Wiltrout RH. Immunotherapy of cancer by IL-12-based cytokine combinations. Expert Opin Biol Ther. 2007;7:1705–1721. doi: 10.1517/14712598.7.11.1705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horton HM, Dorigo O, Hernandez P, Anderson D, Berek JS., and , Parker SE. IL-2 plasmid therapy of murine ovarian carcinoma inhibits the growth of tumor ascites and alters its cytokine profile. J Immunol. 1999;163:6378–6385. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heller L, Pottinger C, Jaroszeski MJ, Gilbert R., and , Heller R. In vivo electroporation of plasmids encoding GM-CSF or interleukin-2 into existing B16 melanomas combined with electrochemotherapy induces long-term antitumour immunity. Melanoma Res. 2000;10:577–583. doi: 10.1097/00008390-200012000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horton HM, Lalor PA., and , Rolland AP. IL-2 plasmid electroporation: from preclinical studies to phase I clinical trial. Methods Mol Biol. 2008;423:361–372. doi: 10.1007/978-1-59745-194-9_28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parker SE, Vahlsing HL, Lew D, Martin T, Hall B, Kornburst D, et al. Cancer gene therapy using plasmis DNA—pharmacokinetics and safety evaluation of an IL-12 plasmid DNA expression vector in rodents and nonhuman primates. Biopharm Appl Technol Biopharm Dev. 2008;12:18–24. [Google Scholar]

- Lohr F, Lo DY, Zaharoff DA, Hu K, Zhang X, Li Y, et al. Effective tumor therapy with plasmid-encoded cytokines combined with in vivo electroporation. Cancer Res. 2001;61:3281–3284. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lucas ML, Heller L, Coppola D., and , Heller R. IL-12 plasmid delivery by in vivo electroporation for the successful treatment of established subcutaneous B16.F10 melanoma. Mol Ther. 2002;5:668–675. doi: 10.1006/mthe.2002.0601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lucas ML., and , Heller R. IL-12 gene therapy using an electrically mediated nonviral approach reduces metastatic growth of melanoma. DNA Cell Biol. 2003;22:755–763. doi: 10.1089/104454903322624966. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heller L, Merkler K, Westover J, Cruz Y, Coppola D, Benson K, et al. Evaluation of toxicity following electrically mediated interleukin-12 gene delivery in a B16 mouse melanoma model. Clin Cancer Res. 2006;12:3177–3183. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-05-2727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daud AI, DeConti RC, Andrews S, Urbas P, Riker AL, Sondak VK, et al. Human trial of in vivo electroporation-mediated gene transfer: safety and efficacy of interleukin-12 plasmid dose escalation in metastatic melanoma. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:5896–5903. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.15.6794. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weber LW, Bowne WB, Wolchok JD, Srinivasan R, Qin J, Moroi Y, et al. Tumor immunity and autoimmunity induced by immunization with homologous DNA. J Clin Invest. 1998;102:1258–1264. doi: 10.1172/JCI4004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowne WB, Srinivasan R, Wolchok JD, Hawkins WG, Blachere NE, Dyall R, et al. Coupling and uncoupling of tumor immunity and autoimmunity. J Exp Med. 1999;190:1717–1722. doi: 10.1084/jem.190.11.1717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalat M, Kupcu Z, Schuller S, Zalusky D, Zehetner M, Paster W, et al. In vivo plasmid electroporation induces tumor antigen-specific CD8+ T-cell responses and delays tumor growth in a syngeneic mouse melanoma model. Cancer Res. 2002;62:5489–5494. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bergman PJ, McKnight J, Novosad A, Charney S, Farrelly J, Craft D, et al. Long-term survival of dogs with advanced malignant melanoma after DNA vaccination with xenogeneic human tyrosinase: a phase I trial. Clin Cancer Res. 2003;9:1284–1290. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bergman PJ, Camps-Palau MA, McKnight JA, Leibman NF, Craft DM, Leung C, et al. Development of a xenogeneic DNA vaccine program for canine malignant melanoma at the Animal Medical Center. Vaccine. 2006;24:4582–4585. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2005.08.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liao JC, Gregor P, Wolchok JD, Orlandi F, Craft D, Leung C, et al. Vaccination with human tyrosinase DNA induces antibody responses in dogs with advanced melanoma. Cancer Immun. 2006;6:8. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolchok JD, Yuan J, Houghton AN, Gallardo HF, Rasalan TS, Wang J, et al. Safety and immunogenicity of tyrosinase DNA vaccines in patients with melanoma. Mol Ther. 2007;15:2044–2050. doi: 10.1038/sj.mt.6300290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sekaly RP. The failed HIV Merck vaccine study: a step back or a launching point for future vaccine development. J Exp Med. 2008;205:7–12. doi: 10.1084/jem.20072681. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang S, Kennedy JS, West K, Montefiori DC, Coley S, Lawrence J, et al. Cross-subtype antibody and cellular immune responses induced by a polyvalent DNA prime-protein boost HIV-1 vaccine in healthy human volunteers. Vaccine. 2008;26:3947–3957. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2007.12.060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halwani R, Boyer JD, Yassine-Diab B, Haddad EK, Robinson TM, Kumar S, et al. Therapeutic vaccination with simian immunodeficiency virus (SIV)-DNA + IL-12 or IL-15 induces distinct CD8 memory subsets in SIV-infected macaques. J Immunol. 2008;180:7969–7979. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.180.12.7969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bansal A, Jackson B, West K, Wang S, Lu S, Kennedy JS, et al. Multifunctional T-cell characteristics induced by a polyvalent DNA prime/protein boost human immunodeficiency virus type 1 vaccine regimen given to healthy adults are dependent on the route and dose of administration. J Virol. 2008;82:6458–6469. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00068-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson CC, Newman MJ, Livingston BD, MaWhinney S, Forster JE, Scott J, et al. Clinical phase 1 testing of the safety and immunogenicity of an epitope-based DNA vaccine in human immunodeficiency virus type 1-infected subjects receiving highly active antiretroviral therapy. Clin Vaccine Immunol. 2008;15:986–994. doi: 10.1128/CVI.00492-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu J, Kjeken R, Mathiesen I., and , Barouch DH. Recruitment of antigen-presenting cells to the site of inoculation and augmentation of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 DNA vaccine immunogenicity by in vivo electroporation. J Virol. 2008;82:5643–5649. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02564-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirao L, Wu L, Khan AS, Hokey D, Yan J, Dai A, et al. Combined effects of IL-12 and electroporation enhances the potency of DNA vaccination in macaques. Vaccine. 2008;26:3112–3120. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2008.02.036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosati M, Valentin A, Jalah R, Patel V, von Gegerfelt AS, Bergamaschi C, et al. Increased immune responses in rhesus macaques by DNA vaccination combined with electroporation. Vaccine. 2008;26:5223–5229. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2008.03.090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirao LA, Wu L, Khan AS, Satishchandran A, Draghia-Akli R., and , Weiner DB. Intradermal/subcutaneous immunization by electroporation improves plasmid vaccine delivery and potency in pigs and rhesus macaques. Vaccine. 2008;26:440–448. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2007.10.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cristillo AD, Weiss D, Hudacik L, Restrepo S, Galmin L, Suschak J, et al. Persistent antibody and T cell responses induced by HIV-1 DNA vaccine delivered by electroporation. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2008;366:29–35. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2007.11.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cristillo AD, Galmin L, Restrepo S, Hudacik L, Suschak J, Lewis B, et al. HIV-1 Env vaccine comprised of electroporated DNA and protein co-administered with Talabostat. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2008;370:22–26. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2008.02.145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cristillo AD, Wang S, Caskey MS, Unangst T, Hocker L, He L, et al. Preclinical evaluation of cellular immune responses elicited by a polyvalent DNA prime/protein boost HIV-1 vaccine. Virology. 2006;346:151–168. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2005.10.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang Y, Chen Z, Zhang W, Gurner D, Song Y, Gardiner DF, et al. Design, construction and characterization of a dual-promoter multigenic DNA vaccine directed against an HIV-1 subtype C/B' recombinant. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2008;47:403–411. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e3181651b9d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin YY, Alphs H, Hung CF, Roden RB., and , Wu TC. Vaccines against human papillomavirus. Front Biosci. 2007;12:246–264. doi: 10.2741/2062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin CT, Tsai YC, He L, Calizo R, Chou HH, Chang TC, et al. A DNA vaccine encoding a codon-optimized human papillomavirus type 16 E6 gene enhances CTL response and anti-tumor activity. J Biomed Sci. 2006;13:481–488. doi: 10.1007/s11373-006-9086-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng WF, Hung CF, Chai CY, Hsu KF, He L, Ling M, et al. Tumor-specific immunity and antiangiogenesis generated by a DNA vaccine encoding calreticulin linked to a tumor antigen. J Clin Invest. 2001;108:669–678. doi: 10.1172/JCI12346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peng S, Ji H, Trimble C, He L, Tsai YC, Yeatermeyer J, et al. Development of a DNA vaccine targeting human papillomavirus type 16 oncoprotein E6. J Virol. 2004;78:8468–8476. doi: 10.1128/JVI.78.16.8468-8476.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steele C, Sacks PG, dler-Storthz K., and , Shillitoe EJ. Effect on cancer cells of plasmids that express antisense RNA of human papillomavirus type 18. Cancer Res. 1992;52:4706–4711. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benencia F, Courreges MC., and , Coukos G. Whole tumor antigen vaccination using dendritic cells: comparison of RNA electroporation and pulsing with UV-irradiated tumor cells. J Transl Med. 2008;6:21–34. doi: 10.1186/1479-5876-6-21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dell K, Klein C., and , Gissmann L. Comparison of DNA- and mRNA-transfected mouse dendritic cells as potential vaccines against the human papillomavirus type 16 associated oncoprotein E7. Antivir Ther. 2008;13:495–509. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yan J, Harris K, Khan AS, Draghia-Akli R, Sewell DA., and , Weiner DB. Cellular immunity induced by a novel HPV18 DNA vaccine encoding an E6/E7 fusion consensus protein in mice and rhesus macaques. Vaccine. 2008;26:5210–5215. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2008.03.069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forns X, Payette PJ, Ma X, Satterfield W, Eder G, Mushahwar IK, et al. Vaccination of chimpanzees with plasmid DNA encoding the hepatitis C virus (HCV) envelope E2 protein modified the infection after challenge with homologous monoclonal HCV. Hepatology. 2000;32:618–625. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2000.9877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frelin L, Ahlen G, Alheim M, Weiland O, Barnfield C, Liljestrom P, et al. Codon optimization and mRNA amplification effectively enhances the immunogenicity of the hepatitis C virus nonstructural 3/4A gene. Gene Ther. 2004;11:522–533. doi: 10.1038/sj.gt.3302184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahlen G, Soderholm J, Tjelle T, Kjeken R, Frelin L, Hoglund U, et al. In vivo electroporation enhances the immunogenicity of hepatitis C virus nonstructural 3/4A DNA by increased local DNA uptake, protein expression, inflammation, and infiltration of CD3+ T cells. J Immunol. 2007;179:4741–4753. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.179.7.4741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lang KA, Yan J, Draghia-Akli R, Khan A., and , Weiner DB. Strong HCV NS3- and NS4A-specific cellular immune responses induced in mice and Rhesus macaques by a novel HCV genotype 1a/1b consensus DNA vaccine. Vaccine. 2008;26:6225–6231. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2008.07.052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Capone S, Zampaglione I, Vitelli A, Pezzanera M, Kierstead L, Burns J, et al. Modulation of the immune response induced by gene electrotransfer of a hepatitis C virus DNA vaccine in nonhuman primates. J Immunol. 2006;177:7462–7471. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.177.10.7462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pavlenko M, Roos AK, Lundqvist A, Palmborg A, Miller AM, Ozenci V, et al. A phase I trial of DNA vaccination with a plasmid expressing prostate-specific antigen in patients with hormone-refractory prostate cancer. Br J Cancer. 2004;91:688–694. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6602019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller AM, Ozenci V, Kiessling R., and , Pisa P. Immune monitoring in a phase 1 trial of a PSA DNA vaccine in patients with hormone-refractory prostate cancer. J Immunother. 2005;28:389–395. doi: 10.1097/01.cji.0000165353.19171.41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roos AK, King A., and , Pisa P. DNA vaccination for prostate cancer. Methods Mol Biol. 2008;423:463–472. doi: 10.1007/978-1-59745-194-9_36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roos AK, Moreno S, Leder C, Pavlenko M, King A., and , Pisa P. Enhancement of cellular immune response to a prostate cancer DNA vaccine by intradermal electroporation. Mol Ther. 2006;13:320–327. doi: 10.1016/j.ymthe.2005.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsuda T., and , Cepko CL. Controlled expression of transgenes introduced by in vivo electroporation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104:1027–1032. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0610155104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsuda T., and , Cepko CL. Analysis of gene function in the retina. Methods Mol Biol. 2008;423:259–278. doi: 10.1007/978-1-59745-194-9_19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bloquel C, Denys A, Boissier MC, Apparailly F, Bigey P, Scherman D, et al. Intra-articular electrotransfer of plasmid encoding soluble TNF receptor variants in normal and arthritic mice. J Gene Med. 2007;9:986–993. doi: 10.1002/jgm.1088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen MW, Cheng TJ, Huang Y, Jan JT, Ma SH, Yu AL, et al. A consensus-hemagglutinin-based DNA vaccine that protects mice against divergent H5N1 influenza viruses. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105:13538–13543. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0806901105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laddy DJ, Yan J, Kutzler M, Kobasa D, Kobinger GP, Khan AS, et al. Heterosubtypic protection against pathogenic human and avian influenza viruses via in vivo electroporation of synthetic consensus DNA antigens. PLoS ONE. 2008;3:e2517. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0002517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiarella P, Massi E, De Robertis M, Sibilio A, Parrella P, Fazio VM, et al. Electroporation of skeletal muscle induces danger signal release and antigen-presenting cell recruitment independently of DNA vaccine administration. Expert Opin Biol Ther. 2008;8:1645–1657. doi: 10.1517/14712598.8.11.1645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]