Abstract

Experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis (EAE) constitutes a paradigm of antigen (Ag)-specific T cell driven autoimmune diseases. In this study, we transferred bone marrow cells (BMCs) expressing an autoantigen (autoAg), the peptide 40–55 of the myelin oligodendrocytic glycoprotein (MOG40–55), to induce preventive and therapeutic immune tolerance in a murine EAE model. Transfer of BMC expressing MOG40–55 (IiMOG-BMC) into partially myeloablated mice resulted in molecular chimerism and in robust protection from the experimental disease. In addition, in mice with established EAE, transfer of transduced BMC with or without partial myeloablation reduced the clinical and histopathological severity of the disease. In these experiments, improvement was observed even in the absence of engraftment of the transduced hematopoietic cells, probably rejected due to the previous immunization with the autoAg. Splenocytes from mice transplanted with IiMOG-BMC produced significantly higher amounts of interleukin (IL)-5 and IL-10 upon autoAg challenge than those of control animals, suggesting the participation of regulatory cells. Altogether, these results suggest that different tolerogenic mechanisms may be mediating the preventive and the therapeutic effects. In conclusion, this study demonstrates that a cell therapy using BMC expressing an autoAg can induce Ag-specific tolerance and ameliorate established EAE even in a nonmyeloablative setting.

Introduction

Induction of antigen (Ag)-specific immune tolerance has long been an elusive “holy grail” pursued for organ and cell transplantation, some replacement therapies, autoimmunity, and also for gene therapy. One of the most promising strategies to induce long-term immune tolerance is by genetic modification of hematopoietic stem cells resulting in a state of molecular chimerism.1 This notion is analogous to that of donor-specific tolerance associated with mixed hematopoietic chimerism.2 In gene-therapy protocols, enforced expression of foreign genes in somatic cells (e.g., muscle) or transfer of autologous cells expressing foreign proteins after ex vivo transduction into immunocompetent individuals usually elicit specific immune responses and rejection of the transduced cells. It has been proposed that creation of molecular chimerism by transferring gene modified autologous or syngeneic hematopoietic cells induces Ag-specific tolerance.3 This strategy has been used to induce immune tolerance for different applications including allogeneic transplantation,1,3,4 autoimmune diseases,5,6,7 inherited diseases,8 and other experimental settings.9

However, creation of stable hematopoietic molecular chimerism relies on the engraftment of gene-modified hematopoietic stem cells, which requires a hematopoietic transplantation and, in most cases, the use of preparative myeloablative and/or immunosuppressive treatments (known as conditioning) whose toxicity precludes its use in the clinics for tolerance induction. This stresses the need for investigation on well-tolerated, minimally myeloablative regimens, yet capable of allowing stable engraftment of gene-modified autologous hematopoietic cells.

Autoimmune diseases constitute a paradigm of the loss of the normal immune tolerance to self-Ag. Experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis (EAE) has been extensively used to study immune mechanisms in the central nervous system (CNS) and to evaluate potential therapies for multiple sclerosis. The disease is induced in susceptible rodent strains or nonhuman primates by immunization with peptides or proteins of the myelin sheath such as myelin basic protein, proteolipid protein (PLP), or myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein (MOG), all candidate multiple sclerosis autoantigen (autoAg). Interestingly, the immune response to myelin basic protein and PLP observed in EAE is directed to epitopes expressed only in the CNS but not in the thymus while MOG is also expressed at very low levels in thymus. Hence, the central tolerance to these EAE inducing Ag is precarious.10

In the present study, we show that the transfer of bone marrow cells (BMCs) expressing an autoAg induces specific immune tolerance in mice with EAE. This study, designed with preventive and therapeutic arms, clearly demonstrates both prevention of EAE and reduction of its severity, even in the absence of any myeloablative conditioning.

Results

Vector producing cell lines and transduction efficiency of murine BMC

Vectors encoding either the murine invariant chain (Ii) and enhanced green fluorescent protein (EGFP) or Ii containing the 40–55 MOG peptide (MOG40–55) sequence and EGFP (IiMOG) were generated (Figure 1). The SF1-EGFP vector has been described elsewhere.11 BMC were transduced using a multiplicity of infection of 1–2. Mean transduction efficiencies were (mean ± SD) 21.5 ± 7.9% (IiMOG), 15.6 ± 3.9% (Ii), and 21.8 ± 6.5% (EGFP).

Figure 1.

Retroviral vectors. (a) Bicistronic retroviral vector containing the murine Ii in which the sequence encoding the CLIP region was replaced by that encoding the encephalitogenic peptide MOG40–55 and the EGFP reporter gene placed after an IRES sequence. (b) The control vector encoding the WT murine Ii and EGFP. (c) A second retroviral control vector which only encodes EGFP. EGFP, enhanced green fluorescent protein; Ii, Invariant chain (CD74); IRES, Internal ribosome entry site; LTR, long terminal repeat; MOG, myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein.

Transplantation of IiMOG-BMC prevents EAE

C57BL/6J mice were conditioned with busulfan and transplanted with 0.7–1 × 106 BMC transduced with either the EGFP vector (EGFP-treated mice) or the IiMOG vector (IiMOG-treated mice) or not transplanted. Additionally, a group of untreated mice (NT) was included as disease control. Three weeks after bone marrow transplantation (BMT), chimerism was assessed in the peripheral blood (PB) and EAE induced. IiMOG-treated mice were strongly protected from EAE in comparison with controls (Figure 2a). In fact, only 5/13 (38.5%) IiMOG-treated mice developed EAE signs in contrast to 14/15 (93.3%) of NT and 11/13 (84.6%) of EGFP-treated animals (P < 0.01). Overall, IiMOG-treated mice had significantly lower maximum and cumulative clinical scores than controls (Table 1). In addition, the disease was more transient and/or less severe in the five IiMOG-treated mice developing clinical signs than in controls (Supplementary Figure S1).

Figure 2.

Effect of preventive gene therapy on EAE and anti-MOG Ab production. (a) Clinical score. Animals transplanted with IiMOG-BMC before EAE induction were strongly protected from the disease, in comparison with controls. Data from two independent experiments are represented. EAE was evaluated using the following 6-point scale: 0 = no clinical signs; 0.5 = partial loss of tail tonus for three consecutive days; 1 = full tail paralysis; 2 = mild paraparesis of one or both hind limbs; 3 = paraplegia; 4 = tetraparesis; 5 = tetraplegia; 6 = death. (b) Anti-MOG40–55 IgG reactivity. Serum samples were obtained at the time of killing (day 28 p.i.) and anti-MOG40–55 Ab were analyzed by ELISA. Anti-MOG40–55 Ab were more frequently found and their titers were significantly higher in EGFP-treated mice than in their IiMOG-treated counterparts.

Table 1.

Transplantation of IiMOG-BMC prevents EAE

Protection from EAE is not associated with the levels of molecular chimerism

Analysis of donor and molecular chimerisms in PB samples prior to EAE induction showed that virtually all IiMOG-treated mice had donor engraftment (mean level 8.4 ± 10.0%) and molecular chimerism (4.4 ± 6.7%). Although IiMOG-treated mice were clearly protected, no association was found between the levels of molecular chimerism and protection from EAE (data not shown).

Lower incidence of anti-MOG40–55 antibodies (Ab) in IiMOG-treated mice

Anti-MOG40–55 IgG Ab were analyzed four weeks postimmunization (p.i.). The risk of developing anti-MOG40–55 Ab was lower in IiMOG-treated mice (IiMOG: 30.8%; EGFP: 83.3%). In addition, the levels of specific Ab were significantly decreased in the IiMOG-treated group (Figure 2b). No association was found in IiMOG-treated mice between the levels of molecular chimerism and the presence of specific Ab. Additionally, no significant differences in Ab levels were observed between protected and nonprotected IiMOG-treated mice (data not shown).

Transplantation of IiMOG-BMC improves established EAE

At day 15–17 p.i., when the first neurological signs were present in the majority (>90%) of mice (mean onset day: 11.0 ± 4.0 p.i.), animals were randomized into three different groups (NT, Ii, or IiMOG) in such a way that the clinical parameters would be comparable between groups. Mice were conditioned with busulfan and transplanted with 0.6–1.6 × 106 transduced BMC. From then on, the clinical follow-up was carried out blinded by a single researcher. In two experiments, animals were followed for an extended period of time (until days 86 and 104 p.i., respectively) and, in another experiment, mice were followed for 41 days p.i., as we sought to obtain cells and tissues suitable for immunological and histopathological studies.

Starting at day 2 until day 16 after BMT, clinical improvement was observed in a significant proportion of the IiMOG-treated mice in comparison with the controls (Figure 3). For this study, remission was defined as a measurable maintained clinical improvement, and full recovery as complete remission of all clinical signs. Pooling the data from three independent experiments, full clinical recoveries were observed in 7 of 22 IiMOG-treated mice (22.7%), in contrast to only 1 of 23 (4.3%) Ii-treated controls and 1 of 19 (5.3%) NT controls (P < 0.05). Furthermore, at the end of the experiment 5 of the 7 full-recovered mice remained disease-free. In addition, the cumulative score was significantly lower in the IiMOG-treated group than in controls (IiMOG: 52.0 ± 29.1; Ii: 80.6 ± 14.5; NT: 85.9 ± 19.0, P < 0.001).

Figure 3.

Amelioration of EAE clinical course on therapeutic gene therapy. Mice were conditioned with busulfan and transplanted with BMC expressing either Ii or the IiMOG transgene, a median of 5 days after the clinical onset. After transplantation of BMC expressing IiMOG, mice experienced a clinical recovery from EAE, while this was not observed in the Ii-treated controls. Each chart represents an independent experiment. Arrows indicate the day of BMT.

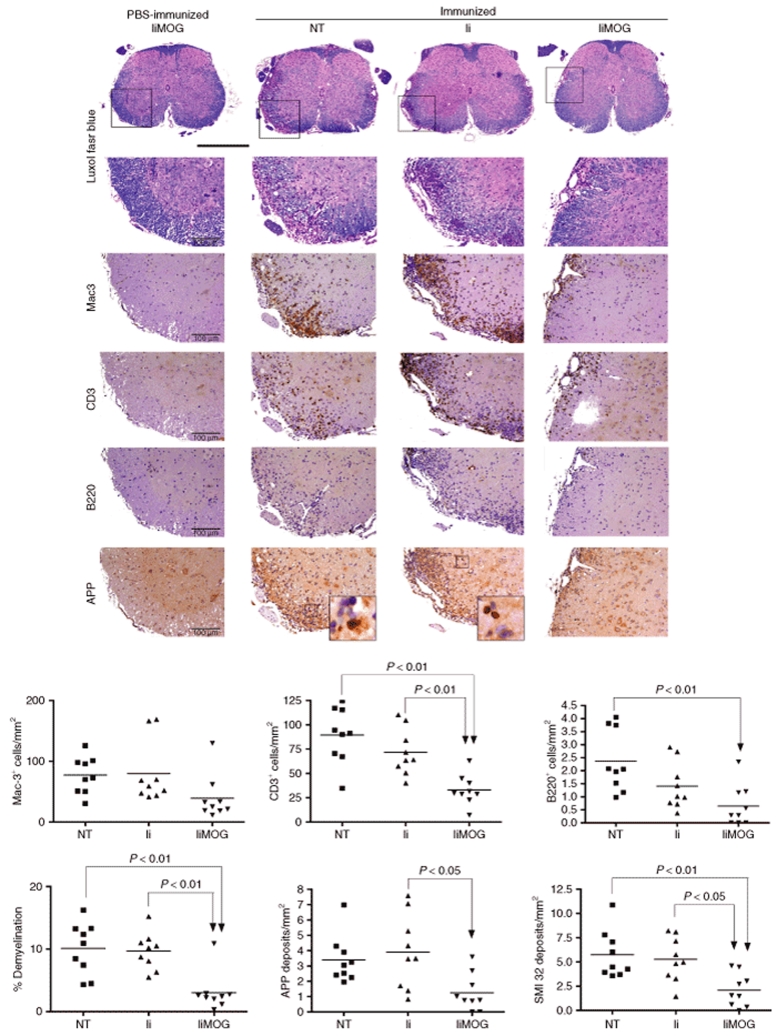

CNS pathology is improved by gene therapy with autoAg

The histopathological study of a total of 27 CNS samples, nine from each experimental group, was carried out in a blinded manner. Infiltration of T and B cells as well as the demyelination area and axonal damage were significantly reduced in IiMOG-treated mice (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Reduced spinal cord inflammation and axonal injury after liMOG-BMC transfer. The presence of macrophage/microglia (Mac-3+ cells), T cells (CD3+ cells), B cells (B220+ cells), and the extent of demyelination (luxol fast blue) and axonal damage (APP and SMI 32) in the central nervous system were analyzed. The study was performed in one representative experiment, which included PBS-immunized controls (experiment III, n = 9 in each group). The number of infiltrating CD3+ T lymphocytes was significantly reduced in IiMOG-treated mice compared with both Ii-treated and NT control mice (P < 0.01). Infiltrating B cells (B220+) were significantly reduced in IiMOG mice in comparison with NT controls. In addition, the demyelinating area, the acute axonal damage (measured by the amount of APP deposits/mm2) and functional abnormalities of axons (measured by the amount of SMI 32 deposits/mm2) were significantly reduced in the IiMOG-treated mice. Inflammation was restricted to the white matter, leading to substantial destruction of myelin (luxol fast blue) as well as axonal injury (APP) in control animals. No inflammation was seen in healthy controls receiving the IiMOG-BMC. Bar = 100 µm except for overview, 500 µm.

Humoral anti-MOG40–55 response does not predict EAE outcome

Anti-MOG40–55 Ab were analyzed at the time of killing. In contrast to what was observed in the preventive arm, Ab were present in the sera of a significant fraction of the immunized animals, although no significant differences were found between the experimental groups (IiMOG: 41.7%; Ii: 45.5%; Figure 5a) nor between recovered and unrecovered mice within the IiMOG-treated group (data not shown), which suggests a lack of impact of these Ab on EAE outcome.

Figure 5.

Splenocytes from IiMOG-treated mice secreted more IL-5 and IL-10 upon autoAg challenge while the humoral response was not affected. (a) Anti-MOG40–55 IgG reactivity in mice sera. Both the prevalence and the mean levels of anti-MOG Ab were similar in all experimental groups. Dotted lines represent the mean optical density (OD) of the control sera plus 3 SD. (b) Splenocytes from IiMOG-treated mice secreted more IL-5 and IL-10 upon autoAg challenge in comparison with those of Ii controls. Culture supernatants from splenocytes were harvested 72 h after incubation with MOG40–55 and the concentrations of GM-CSF, IFN-γ, IL-1α, IL-2, IL-4, IL-5, IL-6, IL-10, IL-17, and TNF-α were measured by a Multiplex assay. TGF-β levels were assessed by ELISA. Concentrations of IL-17 and IFN-γ, two important cytokines involved in the pathogenesis of EAE, were similar in both groups.

Splenocytes of IiMOG-treated mice secrete more IL-5 and IL-10

Splenocytes obtained at day 41 p.i. were cultured in the presence and absence of MOG40–55, and the cytokine production pattern was analyzed. As shown in Figure 5b, concentrations of interleukin (IL)-5 and IL-10 were significantly higher in IiMOG-treated mice than in Ii-treated controls (92.1 ± 60.5 vs. 23.9 ± 33.2 pg/ml for IL-10 and 229.5 ± 180.9 vs. 90.4 ± 75.0 pg/ml for IL-5; P < 0.05 in both cases). No significant differences were observed for the rest of cytokines analyzed (Figure 5b).

The frequency of IFN-γ and IL-17 specific producing cells are not altered after transfer of IiMOG-BMC

Because IL-17 and IFN-γ play important roles in the pathogenesis of EAE, we investigated whether there were differences in the frequency of cells producing these cytokines. Splenocytes of IiMOG-treated mice yielded similar frequencies of ELISPOT colonies secreting IFN-γ compared to those of Ii-treated controls (Supplementary Figure S2a), with fewer colonies in recovered than in unrecovered mice within the IiMOG-treated group, although this difference was not statistically significant (Supplementary Figure S2c). For IL-17, splenocytes from both IiMOG- and Ii-treated groups yielded similar frequencies of MOG-specific colonies (Supplementary Figure S2b), with no significant differences between recovered and unrecovered mice within the IiMOG-treated group (Supplementary Figure S2d).

Molecular chimerism is virtually absent in IiMOG-treated mice

To assess the levels of donor and molecular chimerism, PB samples were analyzed both 30 days after BMT and at the time of killing in the hematopoietic tissues in all experiments. Although donor engraftment was detected in virtually all the transplanted mice 30 days after BMT (mean level 5.1 ± 4.2%) in IiMOG-treated animals, cells expressing EGFP were either absent or present at very low levels (0.2 ± 0.8%), in contrast to the percentages found in Ii-treated mice, (14.3 ± 7.6% for donor chimerism and 7.3 ± 4.3% for molecular chimerism) (Figure 6a,b), most likely due to the anti-MOG immune response elicited in the mice previously injected with the autoAg. This notion is also supported by the observations that both groups had similar levels of nontransduced donor chimerism (Figure 6b) and that nonsensitized mice immunized only with phosphate buffered saline transplanted with transduced BMC displayed similar levels of both donor engraftment (IiMOG: 10.9 ± 5.5%, Ii: 11.0 ± 5.7%) and molecular chimerism (IiMOG: 4.4 ± 3.1%, Ii: 5.0 ± 3.0%; P = 0.841) in their PB, suggesting a lack of rejection in these mice. Similar results were found in other hematopoietic tissues (PB, BM, spleen, and thymus) at the end of the experiments (Figure 6c). Additionally, both groups of transplanted mice displayed similar lineage patterns (CD3+, B220+, CD11b+, and Gr-1+) in spleen donor-derived cells and similar CD4/CD8 ratios (IiMOG: 7.5 ± 3.8; Ii: 8.4 ± 4.8), indicating multilineage engraftment (data not shown).

Figure 6.

IiMOG-transduced BMC are cleared in mice with EAE. Donor and molecular chimerism were assessed at different time points after BMT. (a) Levels of donor chimerism (DCh) and molecular chimerism (MCh) in the PB (30 days post-BMT) and in the BM, spleen, and thymus (71 days post-BMT) of a representative experiment. Note the absence of molecular chimerism in the hematopoietic tissues of IiMOG-treated mice. (b) Levels of nontransduced donor chimerism (NTd DCh) and molecular chimerism (MCh) in the PB (30 days post-BMT) of mice pooled from three separate experiments. Note the absence of molecular chimerism in the IiMOG-treated group. (c) Dot plots correspond to analyses of total donor chimerism (CD45.1+ cell population) in the PB of a transplanted mouse (left) and analyses of donor and molecular chimerism (CD45.1+ EGFP+ cell population) in representative samples of Ii-treated (central) and IiMOG-treated mice (right), showing the lack of molecular chimerism in the latter.

Myeloablation is not necessary to achieve Ag-specific tolerance induction

Because this clinical improvement occurred in the absence of engraftment of IiMOG expressing cells, we hypothesized that the therapy would also be effective in unconditioned recipients. To this pursuit, we infused transduced BMC into unconditioned mice with EAE. Much like in the conditioned mice, significant clinical improvement was observed in IiMOG-treated animals in comparison with controls (Figure 7) (cumulative scores: IiMOG: 26.9 ± 21.0, Ii: 47.6 ± 6.8; P < 0.05).

Figure 7.

Therapeutic benefit after non-myeloablative cell transfer. BMC transduced with the therapeutic vector IiMOG or the control vector Ii were infused into nonmyeloablated mice with EAE. Note the clinical improvement after the BMC infusion in the IiMOG-treated group, similar to that observed in the partially myeloablative experiments.

Most transplanted cells have a myeloid phenotype

We investigated the phenotype of the ex vivo cultured BMC after retroviral transduction and before transplantation. The vast majority (65.5–72.3%) of the cells were CD11b+; 19.7–26.6% were Gr-1+ and 8.3–8.6% were CD3+. The percentages of cell populations positive for other lineage markers such as B220 (B cells) or NK1.1 (NK cells) were almost negligible, indicating that our culture conditions preferably drive myeloid differentiation.

Discussion

The fact that EAE can be experimentally induced on immunization with autoAg indicates that potentially autoreactive T cells escape from thymic deletion and are present in normal rodents and primates. Under physiological circumstances their activation is prevented by dominant peripheral mechanisms, among which regulatory T cells are believed to play a major role since in vivo depletion of such cells results in a more severe disease.12,13 To restore tolerance in EAE, Ag-specific based therapies have the potential advantage of avoiding nonspecific immune suppression. In this regard, creation of molecular chimerism via transplantation of hematopoietic cells expressing autoAg has been proposed as a strategy to induce specific tolerance.5 Indeed, molecular chimerism is usually associated with long-term tolerance to the transgene product.5,9,14 However, engraftment of gene-modified BMC usually requires the use of toxic myeloablative and/or immunosuppressive treatments, which precludes its applicability for nonlethal diseases. In this study, we used BMC expressing an autoAg to induce tolerance in EAE. In preliminary experiments, we found that sublethal doses of busulfan did not modify the incidence or severity of the disease while allowing long-term engraftment of the transplanted cells. On the other hand, there is evidence that very low levels of hematopoietic molecular chimerism in mice (even below 1%) can suffice to induce tolerance to a transgene product.15,16

In this work, we used a previously described strategy to express peptides in which the cDNA encoding the CLIP region of the murine Ii molecule is replaced by that encoding a peptide of interest, in this case the MOG40–55, to target its expression to the MHC class II pathway, thus allowing for efficient Ag presentation.17 Preventive transplantation of IiMOG-BMC into partially myeloablated mice resulted in molecular chimerism in PB plus robust disease protection. Mechanisms accounting for such preventive effect in mice with molecular chimerism include both intrathymic clonal deletion (central tolerance).18,19 and peripheral mechanisms such as the induction of regulatory T cells.20 Transplantation of either BMC transgenic for proinsulin II targeted to Ag-presenting cells or BMC transduced with this autoAg into syngeneic nonobese diabetic recipients also induced preventive tolerance.6,21

Regarding the lack of correlation between anti-MOG Ab levels and the clinical severity or disease outcome in our experiments, whether these Ab are pathogenic is still controversial. Heterogeneity in epitope specificity and pathogenicity among anti-MOG Ab has been reported by several groups.22,23 In humans, anti-MOG or antimyelin Ab levels did not correlate with clinical progression in patients with multiple sclerosis.24 In our preventively treated mice, the lack of specific Ab suggests that B cell tolerance was induced in the IiMOG-treated animals, but the mentioned lack of correlation in the therapeutic arm can simply indicate that the Ab can be present in plasma for long periods of time, regardless of whether tolerance is induced or not.

In the therapeutic arm, transfer of IiMOG-BMC resulted in donor engraftment, but autoAg expressing cells were eventually rejected in previously immunized animals. Interestingly, significant clinical improvement was observed in the IiMOG-treated animals in comparison with controls, indicating that autoAg expression by the BMC infused was crucial in modulating the disease, which demonstrates the participation of the adaptative immune system in the therapeutic effect observed. In previous reports, creation of molecular chimerism using hematopoietic cells expressing myelin basic protein failed to prevent or improve the disease.25 More recently, similar strategies have proved effective both preventively and therapeutically in MOG- and PLP-induced EAE.7,26 In these studies, relatively intense myeloablation was used and molecular chimerisms were documented after BMT. In our experiments, significant clinical improvement was observed after the transfer of IiMOG-BMC despite the absence of molecular chimerism, suggesting a different mechanism of action than that of the preventive arm or of the studies mentioned earlier, in which tolerance was probably dependent on the establishment of molecular chimerism. Lack of association between tolerance and molecular chimerism was documented previously. Indeed, tolerance to factor VIII (FVIII) was induced in FVIII-deficient mice transplanted with BMC transduced with FVIII in the absence of FVIII plasma activity,8 which did not rule out the possibility that FVIII was not secreted but still presented as an Ag by transduced cells.

In our therapeutic arm, the absence of molecular chimerism and the relatively short period of time observed between the BMC infusion and the beginning of the clinical improvement suggest that peripheral rather than central mechanisms of tolerance are involved. Adoptive transfer of B cells transduced with PLP into susceptible mice were shown to protect the majority of animals from PLP-induced EAE27 and blocked subsequent relapses in mice with established disease,28 similar to what we observed in our experiments. Mechanisms of peripheral tolerance include clonal deletion, anergy, and suppression mediated by regulatory T cells. The best characterized are the CD4+ CD25+ Foxp3+ T regulatory (Treg) cells and the adaptative type 1 regulatory cells (Tr1), also called Ag-driven IL-10 producing TReg (IL-10 TReg). Both cell types share some common features such as suppressive functions and low proliferative response in vitro, though they have some phenotypic and functional differences.29,30 We found increased IL-5 and IL-10 production by IiMOG-treated mice on Ag challenge in comparison with the Ii controls. IL-10 is an anti-inflammatory cytokine produced primarily by many cell types including both Treg and Tr1 cells. It is both an inducer of Tr1 cells and a key effector cytokine secreted by these cells. Tr1 cells are generated in the periphery on Ag presentation by resting or immature Ag-presenting cells. They do not have a well-defined phenotype and are characterized by a unique pattern of cytokine secretion: high levels of IL-10, TGF-β, and IL-5, low amounts of IFN-γ and IL-2, and no IL-4 (ref. 31). Interestingly, defective IL-10 production by Tr1 cells has recently been described in patients with multiple sclerosis,32 and this cytokine has been shown to play a central role in EAE recovery33,34,35 and in avoiding autoreactivity in normal mice.36 IL-5 is a Th2 cytokine that can be produced by Tr1 but not by natural Treg. Both IL-5 and IL-10 were reported to mediate Tr1 effects.37 The increased production of IL-5 and IL-10 in the IiMOG-treated group support the notion that Ag-driven Tr1 could be mediating the therapeutic effect observed in the IiMOG-treated mice, although the participation of other types of regulatory cells cannot be ruled out.

Immature dendritic cells are involved in the induction of peripheral tolerance by promoting the generation of regulatory T cells.38,39,40 Indeed, immature or resting dendritic cells can drive Tr1 differentiation.38 This effect can be mediated by IL-10-producing CD4+ cells.41 The crucial role for class II expression by Ag-expressing B cells and BMC in tolerance induction was clearly demonstrated in a nonautoimmune setting.42 Murine diabetes was prevented by the transfer of irradiated myeloid (Gr-1+) cells encoding proinsulin II.43 More recently, myeloid (CD11c+ CD11b+) dendritic cells, but not lymphoid (CD8+ CD11b−) dendritic cells were shown to mediate tolerance induction by intravenously Ag injection in an EAE model.44 Both central and peripheral mechanisms have been shown to play a role in tolerance induction by the transfer of murine allogeneic T cells in partially myeloablated recipients receiving immunosuppressive therapy, demonstrating that T cells can also act as tolerogenic Ag-presenting cells.45 As the therapeutic effect of IiMOG-BMC was observed in the absence of engraftment of the MOG expressing cells and because the vast majority of cells from the ex vivo transduced BMC had a myeloid phenotype, we believe that the beneficial effect is mediated by myeloid precursors presenting Ag in a tolerogenic fashion. This reasoning led us to investigate whether the therapy could also work in unconditioned mice, in which we observed similar results. This approach avoids the toxicity of myeloablation and virtually eliminates the risks of insertional mutagenesis, because the transduced cells are eventually rejected. We propose the potential use of autologous BMC encoding autoAg to treat Ag-specific autoimmune diseases.

Materials and Methods

Retroviral vector construction and production of viral supernatants. The coding region of the murine Ii or a chimeric DNA, generated by replacing the sequence encoding aa 89 to 98 of the CLIP region of the WT murine Ii (Swiss-Prot access number P04441) by such encoding the encephalitogenic rat MOG40–55 peptide,46 were cloned into the murine leukemia virus–based retroviral vector SF91-IRES-EGFP-Wpre, obtaining the SF91-IiMOG-I-EGFP (or IiMOG) and the SF91-Ii-I-EGFP (or Ii). The three retroviral vectors used are shown in Figure 1 in more detail.

Two 293T based cell lines producing high infectious viral particles titers (NX-e/IiMOG and NX-e/Ii) were obtained as previously described.16 The vector producing cell line NX-e/EGFP16 (ref. 16) was also used. Cells were maintained in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium supplemented with 10% FCS, 2 mmol/l L-glutamine, 50 IU/ml penicillin and 50 µg/ml streptomycin (all from PAA laboratories, Pasching, Austria).

Mice. Five- to ten-week old female C57Bl/6J mice (CD45.2+, recipients), purchased from Harlan (Indianapolis, IN) and age- and sex-matched B6/SJL-PtprcaPep3b/BoyJ mice (CD45.1+, congenic donors), bred in our animal facility, were used. Experiments were done according to the EU regulations and approved by our institutional Ethics Committee on Animal Experimentation.

BMC transduction. BMC from donor mice were seeded at a density of 106 mononuclear cells (MNC)/ml in pre-coated Retronectin (Takara Bio, Japan) plates and transduced after 48 h of cytokine stimulation.16

Conditioning and BMC transfer. Up to 1.6 × 106 cells were infused intravenously into recipient mice 21 days before EAE induction (preventive arm) or 15–17 days after EAE induction (therapeutic arm). In some experiments, mice were conditioned with two doses of 20 mg/kg intraperitoneally of busulfan (Sigma Chemical, St Louis, MO) on days 3 and 2 prior to BMT.

FACS analysis. Transduction efficiency was assessed by EGFP expression prior to cell infusion. Donor engraftment and molecular chimerism (CD45.1+ events and EGFP+ events in the total CD45+ cell population) were analyzed using PE-conjugated anti-CD45.1 and allophycocyanin (AP)-conjugated anti-CD45.2 (eBioscience, San Diego, CA) in hematopoietic samples at different time points after BMT. Splenocytes were labeled to assess CD4/CD8 ratio (Mouse T Lymphocyte Subset Ab Cocktail, BD Pharmingen, San Jose, CA) and hematopoietic lineage differentiation (anti-CD11b, anti-Gr-1, AP-conjugated anti-CD3, and PE-conjugated anti-NK1.1 from BD Pharmingen; anti-B220 from Caltag Laboratories, Burlingame, CA). The same Ab were used to assess the phenotype of the ex vivo cultured BMC. 7-aminoactinomycin D (7-AAD; Molecular Probes, Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) was used to discriminate dead cells. Data acquisition was performed on a FACSCalibur and analyzed using the DIVA software (BD Pharmingen).

EAE induction and clinical follow-up. Anesthetized mice were immunized by subcutaneous injections of phosphate buffered saline containing 200 µg of MOG40–55 (Proteomics Section, Universitat Pompeu Fabra, Barcelona, Spain) emulsified in CFA (Sigma Chemical) containing 4 mg/ml Mycobacterium tuberculosis H37RA (Difco Laboratories, Detroit, MI). On days 0 and 2 p.i. mice received 500 ng of pertussis toxin (Sigma Chemical) intravenously. Mice immunized in the same way using phosphate buffered saline without the peptide were included as controls of the immunization process. Mice were weighted and examined daily for neurological signs using a 6-point scale as previously described.46

CNS histopathology. Spinal cords were removed, fixed in 4% buffered formalin and embedded in paraffin before staining with hematoxylin and eosin, luxol fast blue to assess the degree of inflammation and demyelination. Anti-MAC-3 (BD Pharmingen), anti-CD3 (Serotec, Düsseldorf, Germany), anti-B220, anti-APP (amyloid precursor protein) (Chemicon, Temecula, CA), and anti-SMI 32 (dephosphorylated neurofilament) (Sternberger Monoclonals, Lutherville, MA) Ab were used for immunohistochemistry, as previously described.47,48

Anti-MOG40–55 Ab detection. Nunc Immuno plates (Nalgene Nunc International, Roskilde, Denmark) were coated overnight with 0.1 µg/well of MOG40–55. Serum samples in duplicates were added and after extensive washes a secondary horseradish peroxidase-conjugated goat antimouse IgG (H+L) was used. On addition of TMB Substrate Reagent Set (BD Pharmingen), plates were read at 450 nm. Results are presented as the mean optical density (OD) of each sample. Positivity was defined as an OD greater than the mean OD + 3 SD of sera from phosphate buffered saline–immunized control mice.

Splenocyte cytokine production. Spleen cells were seeded at a density of 106 MNC/ml in complete RPMI 1640 medium [10% FCS, 2 mmol/l glutamine, 50 IU/ml – 50 µg/ml penicillin-streptomycin, 50 µmol/l 2-mercaptoethanol (Sigma Chemical)] and 5 µg/ml of MOG40–55. Cells cultured without the Ag or with PHA were used as negative and positive controls, respectively. Supernatants were harvested after 72 h and cytokine levels were assessed with the Quantikine TGF-β1 ELISA kit (for TGF-β1 detection; R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN) and the Flow Cytomix Th1/Th2 10plex kit (for detection of the rest of cytokines; Bender MedSystems, Burlingame, CA), according to manufacturer instructions.

ELISPOT assays. Cells were seeded in complete RPMI 1640 medium at a density of 5 × 106 MNC/ml (for detection of IL-17) and 106 MNC/ml (IFN-γ), and were incubated for 20 h. Mouse IL-17 ELISPOT Ready-Set-Go! Kit (eBiosciences, San Diego, CA) and Mouse IFN-γ ELISPOTPLUS kit (Mabtech AB, Nacka Strand, Sweden) were used to detect the cytokine producing cells following the manufacturer's instructions. Spot images were captured with the AID ELISPOT Reader and analyzed with the AID ELISPOT Reader software (Autoimmun Diagnostika GmbH, Strassberg, Germany). Cells cultured without the Ag or with PMA and ionomycin were used as negative and positive controls, respectively.

Statistical analysis. Statistical analysis was performed with the SPSS 15.0 software for Windows. χ2, Fisher's exact test, ANOVA with Bonferroni procedure, Mann–Whitney test or Student's t-test were applied for data comparisons. Differences were considered statistically significant when P values were below 0.05. Quantitative data are presented as mean values ± SD unless otherwise stated.

Supplementary MaterialFigure S1. EAE in nonprotected IiMOG-treated mice is less severe and transient. Individual charts of the EAE clinical course of non-protected IiMOG-treated mice that received the preventive treatment. Only one of the incident animals developed a chronic clinical disease (c), while three other mice only presented a mild and/or short outbreak of clinical signs followed by full recovery (a, b, d, e).Figure S2. The frequency of IFN-γ and IL-17 MOG-specific ELISPOTs did not differ between IiMOG-treated mice and controls. Upon sacrifice (day 41 p.i.), MOG-specific IFN-γ (a) and IL-17 (b) producing splenocytes were quantified by ELISPOT assays. No statistically significant differences were found in their frequencies between the experimental groups. (c) Mice recovering from EAE within the IiMOG-treated group had a lower frequency of specific IFN-γ spots than their unrecovered counterparts (227.5 ± 75.42 vs. 350 ± 144.16 per 106 splenocytes) although this difference did not reach statistical significance (p = 0.123). (d) The frequencies of IL-17 ELISPOTs were similar in recovered and unrecovered mice within the IiMOG-treated group.

Supplementary Material

EAE in nonprotected IiMOG-treated mice is less severe and transient. Individual charts of the EAE clinical course of non-protected IiMOG-treated mice that received the preventive treatment. Only one of the incident animals developed a chronic clinical disease (c), while three other mice only presented a mild and/or short outbreak of clinical signs followed by full recovery (a, b, d, e).

The frequency of IFN-γ and IL-17 MOG-specific ELISPOTs did not differ between IiMOG-treated mice and controls. Upon sacrifice (day 41 p.i.), MOG-specific IFN-γ (a) and IL-17 (b) producing splenocytes were quantified by ELISPOT assays. No statistically significant differences were found in their frequencies between the experimental groups. (c) Mice recovering from EAE within the IiMOG-treated group had a lower frequency of specific IFN-γ spots than their unrecovered counterparts (227.5 ± 75.42 vs. 350 ± 144.16 per 106 splenocytes) although this difference did not reach statistical significance (p = 0.123). (d) The frequencies of IL-17 ELISPOTs were similar in recovered and unrecovered mice within the IiMOG-treated group.

Acknowledgments

We thank Roland Martin, Ricardo Pujol-Borrell and Dolores Jaraquemada for their scientific advice, Joseph Graells for help with language edition of the manuscript, Marta Rosal for assistance with mice, and C. Baum for providing the SF91-IRES-EGFP-Wpre backbone. This work was supported by grants from the European Union FP6 (LSHB CT2004-005242, CONSERT) and the “Instituto de Salud Carlos III”, from the Spanish Ministry of Health PI020205, PI051441. We thank the “Red Española de Esclerosis Múltiple (REEM)” sponsored by the FIS, Ministry of Science and Innovation, Spain, and the “Ajuts per donar Suport als Grups de Recerca de Catalunya (SGR 2005-1081)”, sponsored by the “Agència de Gestió d'Ajuts Universitaris i de Recerca” (AGAUR), Generalitat de Catalunya, Spain. CE is partially supported by the “Miguel Servet” program (CP07/00146) from the FIS, Ministry of Science and Innovation, Spain. AG is supported by the “Comissionat per a Universitats i Recerca del Departament de Innovació, Universitats i Empresa de la Generalitat de Catalunya i del Fons Social Europeu”. The authors declare no competing financial interests.

REFERENCES

- Bracy JL, Sachs DH., and , Iacomini J. Inhibition of xenoreactive natural antibody production by retroviral gene therapy. Science. 1998;281:1845–1847. doi: 10.1126/science.281.5384.1845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wekerle T., and , Sykes M. Mixed chimerism and transplantation tolerance. Annu Rev Med. 2001;52:353–370. doi: 10.1146/annurev.med.52.1.353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emery DW, Sablinski T, Shimada H, Germana S, Gianello P, Foley A, et al. Expression of an allogeneic MHC DRB transgene, through retroviral transduction of bone marrow, induces specific reduction of alloreactivity. Transplantation. 1997;64:1414–1423. doi: 10.1097/00007890-199711270-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bagley J, Tian C, Sachs DH., and , Iacomini J. Induction of T-cell tolerance to an MHC class I alloantigen by gene therapy. Blood. 2002;99:4394–4399. doi: 10.1182/blood.v99.12.4394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alderuccio F, Murphy K., and , Toh BH. Stem cells engineered to express self antigen to treat autoimmunity. Trends Immunol. 2003;24:176–180. doi: 10.1016/s1471-4906(03)00066-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steptoe RJ, Ritchie JM., and , Harrison LC. Transfer of hematopoietic stem cells encoding autoantigen prevents autoimmune diabetes. J Clin Invest. 2003;111:1357–1363. doi: 10.1172/JCI15995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu B, Haviernik P, Wolfraim LA, Bunting KD., and , Scott DW. Bone marrow transplantation combined with gene therapy to induce antigen-specific tolerance and ameliorate EAE. Mol Ther. 2006;13:42–48. doi: 10.1016/j.ymthe.2005.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans GL., and , Morgan RA. Genetic induction of immune tolerance to human clotting factor VIII in a mouse model for hemophilia A. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:5734–5739. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.10.5734. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andersson G, Denaro M, Johnson K, Morgan P, Sullivan A, Houser S, et al. Engraftment of retroviral EGFP-transduced bone marrow in mice prevents rejection of EGFP-transgenic skin grafts. Mol Ther. 2003;8:385–391. doi: 10.1016/s1525-0016(03)00210-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kyewski B., and , Klein L. A central role for central tolerance. Annu Rev Immunol. 2006;24:571–606. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.23.021704.115601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Limon A, Briones J, Puig T, Carmona M, Fornas O, Cancelas JA, et al. High-titer retroviral vectors containing the enhanced green fluorescent protein gene for efficient expression in hematopoietic cells. Blood. 1997;90:3316–3321. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montero E, Nussbaum G, Kaye JF, Perez R, Lage A, Ben-Nun A, et al. Regulation of experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis by CD4+, CD25+ and CD8+ T cells: analysis using depleting antibodies. J Autoimmun. 2004;23:1–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jaut.2004.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reddy J, Illes Z, Zhang X, Encinas J, Pyrdol J, Nicholson L, et al. Myelin proteolipid protein-specific CD4+CD25+ regulatory cells mediate genetic resistance to experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:15434–15439. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0404444101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bagley J, Bracy JL, Tian C, Kang ES., and , Iacomini J. Establishing immunological tolerance through the induction of molecular chimerism. Front Biosci. 2002;1:d1331–d1337. doi: 10.2741/bagley. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kang E, Giri N, Wu T, Sellers S, Kirby M, Hanazono Y, et al. In vivo persistence of retrovirally transduced murine long-term repopulating cells is not limited by expression of foreign gene products in the fully or minimally myeloablated setting. Hum Gene Ther. 2001;12:1663–1672. doi: 10.1089/10430340152528156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Puig T, Kadar E, Limon A, Cancelas JA, Eixarch H, Luquin L, et al. Myeloablation enhances engraftment of transduced murine hematopoietic cells, but does not influence long-term expression of the transgene. Gene Ther. 2002;9:1472–1479. doi: 10.1038/sj.gt.3301826. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bischof F, Wienhold W, Wirblich C, Malcherek G, Zevering O, Kruisbeek AM, et al. Specific treatment of autoimmunity with recombinant invariant chains in which CLIP is replaced by self-epitopes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2001;98:12168–12173. doi: 10.1073/pnas.221220998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brocker T, Riedinger M., and , Karjalainen K. Targeted expression of major histocompatibility complex (MHC) class II molecules demonstrates that dendritic cells can induce negative but not positive selection of thymocytes in vivo. J Exp Med. 1997;185:541–550. doi: 10.1084/jem.185.3.541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kang ES., and , Iacomini J. Induction of central deletional T cell tolerance by gene therapy. J Immunol. 2002;169:1930–1935. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.169.4.1930. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forman D, Kang ES, Tian C, Paez-Cortez J., and , Iacomini J. Induction of alloreactive CD4 T cell tolerance in molecular chimeras: a possible role for regulatory T cells. J Immunol. 2006;176:3410–3416. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.176.6.3410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan J, Clements W, Field J, Nasa Z, Lock P, Yap F, et al. Transplantation of bone marrow genetically engineered to express proinsulin II protects against autoimmune insulitis in NOD mice. J Gene Med. 2006;8:1281–1290. doi: 10.1002/jgm.968. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marta CB, Oliver AR, Sweet RA, Pfeiffer SE., and , Ruddle NH. Pathogenic myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein antibodies recognize glycosylated epitopes and perturb oligodendrocyte physiology. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102:13992–13997. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0504979102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou D, Srivastava R, Nessler S, Grummel V, Sommer N, Bruck W, et al. Identification of a pathogenic antibody response to native myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein in multiple sclerosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:19057–19062. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0607242103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuhle J, Pohl C, Mehling M, Edan G, Freedman MS, Hartung HP, et al. Lack of association between antimyelin antibodies and progression to multiple sclerosis. N Engl J Med. 2007;356:371–378. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa063602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peters TR, Bodine DM, McDonagh KT, Lovett-Racke A, McFarland HF, McFarlin DE, et al. Retrovirus mediated gene transfer of the self antigen MBP into the bone marrow of mice alters resistance to experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis. J Neuroimmunol. 2000;103:51–62. doi: 10.1016/s0165-5728(99)00181-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan J, Ban EJ, Chun KH, Wang S, Backstrom BT, Bernard CC, et al. Transplantation of bone marrow transduced to express self-antigen establishes deletional tolerance and permanently remits autoimmune disease. J Immunol. 2008;181:7571–7580. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.181.11.7571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen CC, Rivera A, Ron N, Dougherty JP., and , Ron Y. A gene therapy approach for treating T-cell-mediated autoimmune diseases. Blood. 2001;97:886–894. doi: 10.1182/blood.v97.4.886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen CC, Rivera A, Dougherty JP., and , Ron Y. Complete protection from relapsing experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis induced by syngeneic B cells expressing the autoantigen. Blood. 2004;103:4616–4618. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-01-0091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roncarolo MG., and , Levings MK. The role of different subsets of T regulatory cells in controlling autoimmunity. Curr Opin Immunol. 2000;12:676–683. doi: 10.1016/s0952-7915(00)00162-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levings MK., and , Roncarolo MG. Phenotypic and functional differences between human CD4+CD25+ and type 1 regulatory T cells. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol. 2005;293:303–326. doi: 10.1007/3-540-27702-1_14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Groux H, O'Garra A, Bigler M, Rouleau M, Antonenko S, de Vries JE, et al. A CD4+ T-cell subset inhibits antigen-specific T-cell responses and prevents colitis. Nature. 1997;389:737–742. doi: 10.1038/39614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martinez-Forero I, Garcia-Munoz R, Martinez-Pasamar S, Inoges S, Lopez-Diaz de Cerio A, Palacios R, et al. IL-10 suppressor activity and ex vivo Tr1 cell function are impaired in multiple sclerosis. Eur J Immunol. 2008;38:576–586. doi: 10.1002/eji.200737271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kennedy MK, Torrance DS, Picha KS., and , Mohler KM. Analysis of cytokine mRNA expression in the central nervous system of mice with experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis reveals that IL-10 mRNA expression correlates with recovery. J Immunol. 1992;149:2496–2505. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jander S, Pohl J, D'Urso D, Gillen C., and , Stoll G. Time course and cellular localization of interleukin-10 mRNA and protein expression in autoimmune inflammation of the rat central nervous system. Am J Pathol. 1998;152:975–982. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang X, Koldzic DN, Izikson L, Reddy J, Nazareno RF, Sakaguchi S, et al. IL-10 is involved in the suppression of experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis by CD25+CD4+ regulatory T cells. Int Immunol. 2004;16:249–256. doi: 10.1093/intimm/dxh029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson AC, Reddy J, Nazareno R, Sobel RA, Nicholson LB., and , Kuchroo VK. IL-10 plays an important role in the homeostatic regulation of the autoreactive repertoire in naive mice. J Immunol. 2004;173:828–834. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.173.2.828. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bacchetta R, Bigler M, Touraine JL, Parkman R, Tovo PA, Abrams J, et al. High levels of interleukin 10 production in vivo are associated with tolerance in SCID patients transplanted with HLA mismatched hematopoietic stem cells. J Exp Med. 1994;179:493–502. doi: 10.1084/jem.179.2.493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roncarolo MG, Levings MK., and , Traversari C. Differentiation of T regulatory cells by immature dendritic cells. J Exp Med. 2001;193:F5–F9. doi: 10.1084/jem.193.2.f5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hawiger D, Inaba K, Dorsett Y, Guo M, Mahnke K, Rivera M, et al. Dendritic cells induce peripheral T cell unresponsiveness under steady state conditions in vivo. J Exp Med. 2001;194:769–779. doi: 10.1084/jem.194.6.769. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rutella S., and , Lemoli RM. Regulatory T cells and tolerogenic dendritic cells: from basic biology to clinical applications. Immunol Lett. 2004;94:11–26. doi: 10.1016/j.imlet.2004.04.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Menges M, Rossner S, Voigtlander C, Schindler H, Kukutsch NA, Bogdan C, et al. Repetitive injections of dendritic cells matured with tumor necrosis factor α induce antigen-specific protection of mice from autoimmunity. J Exp Med. 2002;195:15–21. doi: 10.1084/jem.20011341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El-Amine M, Melo M, Kang Y, Nguyen H, Qian J., and , Scott DW. Mechanisms of tolerance induction by a gene-transferred peptide-IgG fusion protein expressed in B lineage cells. J Immunol. 2000;165:5631–5636. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.165.10.5631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steptoe RJ, Ritchie JM, Jones LK., and , Harrison LC. Autoimmune diabetes is suppressed by transfer of proinsulin-encoding Gr-1+ myeloid progenitor cells that differentiate in vivo into resting dendritic cells. Diabetes. 2005;54:434–442. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.54.2.434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li H, Zhang GX, Chen Y, Xu H, Fitzgerald DC, Zhao Z, et al. CD11c+CD11b+ dendritic cells play an important role in intravenous tolerance and the suppression of experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis. J Immunol. 2008;181:2483–2493. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.181.4.2483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tian C, Yuan X, Bagley J, Blazar BR, Sayegh MH., and , Iacomini J. Induction of transplantation tolerance by combining non-myeloablative conditioning with delivery of alloantigen by T cells. Clin Immunol. 2008;127:130–137. doi: 10.1016/j.clim.2008.01.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Espejo C, Carrasco J, Hidalgo J, Penkowa M, Garcia A, Saez-Torres I, et al. Differential expression of metallothioneins in the CNS of mice with experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis. Neuroscience. 2001;105:1055–1065. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(01)00252-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prinz M, Garbe F, Schmidt H, Mildner A, Gutcher I, Wolter K, et al. Innate immunity mediated by TLR9 modulates pathogenicity in an animal model of multiple sclerosis. J Clin Invest. 2006;116:456–464. doi: 10.1172/JCI26078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Loo G, De Lorenzi R, Schmidt H, Huth M, Mildner A, Schmidt-Supprian M, et al. Inhibition of transcription factor NF-κB in the central nervous system ameliorates autoimmune encephalomyelitis in mice. Nat Immunol. 2006;7:954–961. doi: 10.1038/ni1372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

EAE in nonprotected IiMOG-treated mice is less severe and transient. Individual charts of the EAE clinical course of non-protected IiMOG-treated mice that received the preventive treatment. Only one of the incident animals developed a chronic clinical disease (c), while three other mice only presented a mild and/or short outbreak of clinical signs followed by full recovery (a, b, d, e).

The frequency of IFN-γ and IL-17 MOG-specific ELISPOTs did not differ between IiMOG-treated mice and controls. Upon sacrifice (day 41 p.i.), MOG-specific IFN-γ (a) and IL-17 (b) producing splenocytes were quantified by ELISPOT assays. No statistically significant differences were found in their frequencies between the experimental groups. (c) Mice recovering from EAE within the IiMOG-treated group had a lower frequency of specific IFN-γ spots than their unrecovered counterparts (227.5 ± 75.42 vs. 350 ± 144.16 per 106 splenocytes) although this difference did not reach statistical significance (p = 0.123). (d) The frequencies of IL-17 ELISPOTs were similar in recovered and unrecovered mice within the IiMOG-treated group.