Abstract

Activation of the extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK) signaling pathway has been implicated in mediating a diverse array of cellular functions including cell differentiation, proliferation, and inflammatory responses. In this review, we will discuss approaches to identify inhibitors of ERK proteins through targeting ATP-dependent and ATP-independent mechanisms. Given the diversity of ERK substrates and the importance of ERK signaling in normal cell functions, emphasis will be placed on the methods for identifying small molecular weight compounds that are substrate selective through ATP-independent interactions and potentially relevant to inflammatory processes. The approach for selective targeting of ERK substrates takes advantage of the basic understanding of unique ERK docking domains that are thought to interact with specific amino acid sequences on substrate proteins. Computer aided drug design (CADD) can facilitate the high throughput screening of millions of compounds with the potential for selective interactions with ERK docking domains and disruption of substrate interactions. As such, the CADD approach significantly reduces the number of compounds that will be evaluated in subsequent biological assays and greatly increases the hit rate of biologically active compounds. The potentially active compounds are evaluated for ERK protein binding using spectroscopic and structural biology methods. Compounds that show ERK interactions are then tested for their ability to inhibit substrate interactions and phosphorylation as well as ERK-dependent functions in whole organism or cell-based assays. Finally, the relevance of substrate-selective ERK inhibitors in the context of inflammatory disease will be discussed.

Keywords: Extracellular signal-regulated kinase, mitogen-activated protein kinases, signal transduction, computer aided drug design, docking domains

INTRODUCTION

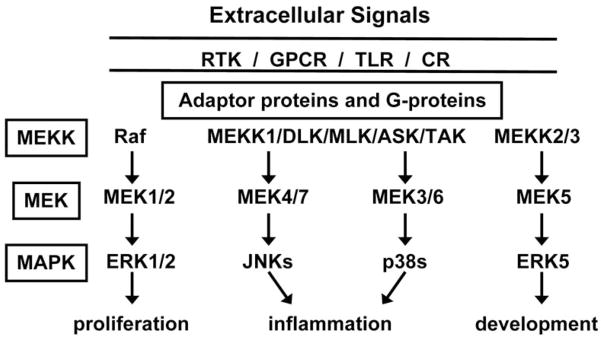

The extracellular signal-regulated kinase isoforms 1 and 2 (ERK1/2) proteins are ubiquitous and multifunctional signaling proteins that are involved in most cellular responses to extracellular signals [1]. ERK1/2 are members of the mitogen activated protein (MAP) kinase superfamily of signaling proteins whose activity is most often regulated by extracellular ligands binding to plasma membrane receptors. These ligand-activated receptors, acting through adaptor proteins and G-proteins, initiate the activation of a three-tiered kinase signaling cascade that funnels a vast amount of information generated at the plasma membrane through to the MAP kinases (Fig. 1). The other major MAP kinase family members that will not be discussed in this review include ERK5, c-Jun N-terminal kinase (JNK), and p38 MAP kinases. For a comprehensive description of the signal transduction cascades that regulate these four MAP kinase signaling cascades, please see the following review articles [1–5]. In the context of inflammation, the p38 MAP kinases have received much attention as promising targets for reducing inflammatory responses. Targeted inhibition of p38 MAP kinase activity has been proposed to alleviate inflammation associated with diseases such as rheumatoid arthritis [6] and asthma [7]. Other excellent reviews that describe the drug discovery programs targeting p38 MAP kinases in the context of inflammatory diseases are available [8, 9]. Despite the fact that the ERK1/2 proteins have been the most comprehensively studies of the MAP kinase, little is known about how they integrate extracellular information into a specific cellular response. In the context of inflammatory disease, targeted inhibition of the ERK proteins may reduce the expression of inflammatory cytokines and the survival of inflammatory cells [10, 11]. While it’s clear that ERK1/2 are important regulators of cell proliferation and inflammatory cell processes, only recently has the development of potentially ERK1/2-selective inhibitors been reported. Using key findings of the regulation and function of ERK proteins, the focus of this review will be on drug discovery efforts that identify small molecular weight compounds aimed at targeted inhibition of the ERK1/2 proteins.

Fig. 1.

Overview of the major MAP kinase signaling pathways. Extracellular signals interact with receptor tyrosine kinases (RTK), G-protein coupled receptors (GPCR), Toll-like receptors (TLR), or cytokine receptors (CR) to initiate signaling pathways. Adaptor proteins and G-proteins initiate the 3-tiered MAP kinase cascade beginning with the MAP or ERK kinase kinases (MEKK), which include Raf proteins, other MEKK isoforms, DLK (dual leucine-zipper bearing kinases), MLK (mixed-lineage kinases), ASK-1 (apoptosis signal-regulating kinase-1) and TAK1 (transforming growth factor-β-activated protein kinase-1). The MEKK proteins phosphorylate and activate the MEKs, which activate the MAP kinases and cellular functions.

EXTRACELLULAR SIGNAL-REGULATED KINASE (ERK) MAP KINASES

The ERK1/2 MAP kinases are serine/threonine kinases that integrate cellular signals in response to a variety of extracellular growth factors, cytokines, and stress signals that affect cell growth, proliferation, and differentiation [1]. Activation of this signaling pathway can occur through a variety of membrane receptors including receptor tyrosine kinases (RTK), G-protein coupled receptors (GPCR), toll-like receptors (TLR), and cytokine receptors (CR) (Fig. 1). The best characterized mechanism for ERK1/2 activation involves growth factor ligand binding to the RTK extracellular domain resulting in receptor dimerization and autophosphorylation of the receptor’s intracellular domain. These phosphorylated tyrosine residues on the receptors promote recruitment of adaptor proteins and sequential activation of the Ras G-proteins, Raf kinases, MAP or ERK kinases 1 and 2 (MEK1/2), and finally ERK1/2. MEK1/2 activates the ERK1/2 proteins through dual phosphorylation of threonine and tyrosine located within a TXY motif on the activation lip found on MAP kinase family members [1]. Although MEK1/2 proteins are the only known activators of ERK1/2, the ERK1/2 proteins have the potential to phosphorylate and regulate the activity of dozens of different substrate proteins found in both the cytoplasm and the nucleus [1]. At first glance, the similarities in sequence and regulation suggest that the ERK1 and ERK2 isoforms are functionally redundant. However, differences between these two isoforms have been observed. For example, knockout of ERK2 in mice results in embryonic lethality, whereas ERK1−/− mice can survive although these strains have defects in thymocyte maturation [12]. These findings suggest that each of these isoforms have unique functions and that ERK2 can largely compensate for ERK1 defects.

The ERK1/2 pathway has received much attention in the context of mutations that contribute to the development and progression of cancer cells. Mutations in the Ras G-proteins have been identified in approximately 30% of all human cancers [13–15], and a constitutively active B-Raf mutation has been found in a majority of malignant melanomas [16]. Moreover, mutations and changes in expression of RTK proteins that regulate ERK1/2 activity also contribute to the uncontrolled proliferation of cancer cells [17–19]. Thus, specific inhibition of proteins in the ERK pathway is an important goal. Several reviews that give an excellent description of clinically relevant inhibitors of RTK activity and proteins that are coupled to ERK1/2 activation have been published [20–25]. A brief overview of specific structural features of ERK1/2 proteins that can be manipulated in the development of ERK-targeted inhibitors will be presented.

ERK REGULATION: ATP BINDING POCKET

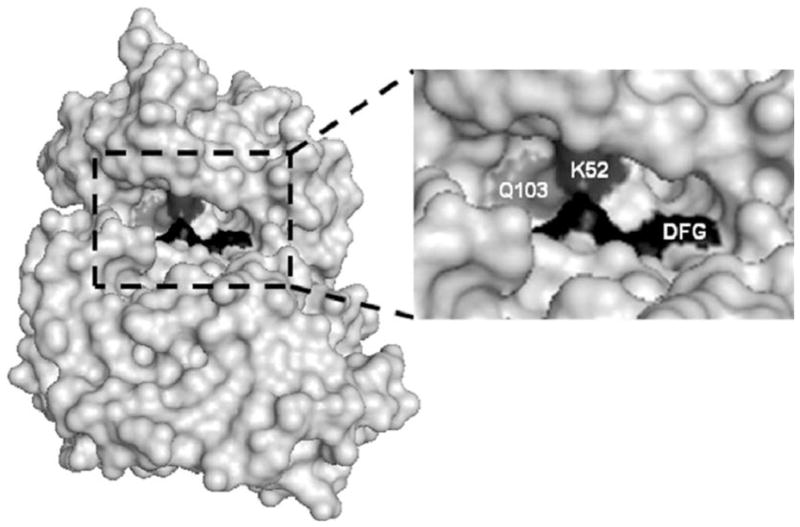

Structural studies of the ERK1/2 and other MAP kinases show conservation of the catalytic domain that includes the ATP binding site [26]. As such, many of the early kinase inhibitors that were developed to target this region and compete for ATP binding lacked specificity. However, a better understanding of the unique features of the ATP binding site through structural biology has yielded many kinase-selective and clinically relevant ATP-competitive inhibitors including STI571, gefitinib, and sorafenib that inhibit elevated tyrosine kinase activity in cancer cells [21, 27]. The catalytic region of kinases contains an ATP binding pocket, which includes hydrophobic residues for coordinating the adenine base and a critical lysine (K52) that anchors the phosphate moieties [26]. Adjacent to the ATP binding region is another pocket that contains a conserved DFG motif that coordinates the binding of magnesium, which is essential for enzyme catalysis and phosphotransfer [28]. Changes in structural conformations within these catalytic pockets, as determined by regulation of the kinase at allosteric sites, will determine enzyme catalysis efficiency. Between these two regions of the catalytic domain is a residue that acts as a gatekeeper controlling access of molecules to the magnesium pocket containing the DFG motif [26]. It has been hypothesized that the gatekeeper residue (Q103 for ERK2) may be a major determinant of regulatory selectivity between MAP kinases and thus possibly exploited in the development of more selective kinase inhibitors [29, 30]. The location of the catalytic region containing the residues important for ATP and magnesium binding are shown in Fig. 2.

Fig. 2.

Space filling model of the ATP binding site on ERK2. The right panel is an expansion of the ATP binding region showing the DFG motif region (residues 165–167) in black, lysine 52 in dark grey, and the gatekeeper glutamine at position 103 in light grey.

MAP KINASE SUBSTRATE-DOCKING DOMAINS

The nature of the interactions between ERK1/2 proteins and the dozens of different substrate proteins are largely unknown. A better understanding of these interactions could be used to develop ERK inhibitors that are selective for specific substrates involved in pathological conditions, while preserving interactions involved in normal cell processes. Studies have explored these interactions by examining unique amino acid sequences on the substrates and the contacts they make on the ERK proteins. Critical analysis of the substrate proteins has revealed two domains that facilitate ERK1/2 interactions and substrate phosphorylation. The first is referred to as the D-domain or DEJL motif (docking site for ERK or JNK, LXL motif), which is conserved in a variety of transcription factor substrates of ERK proteins [31–33]. The D-domain typically consists of a cluster of basic lysine or arginine residues followed by the leucine/any amino acid/leucine (LXL) sequence [34]. In addition to transcription factors, the D-domain is found on the upstream activator MEK1/2 proteins [35, 36], the p90 ribosomal S6 kinase-1 substrate (p90Rsk-1) [37], and several phosphatases that interact with and regulate ERK1/2 [38–40]. A similar sequence is also found on proteins that selectively interact with the JNK MAP kinases [31, 32, 41].

The second ERK1/2 substrate-binding motif is often referred to as the F-domain or the DEF (docking site for ERK, FXF) site. The F-domain consists of the amino acid sequence phenylalanine/any amino acid/phenylalanine followed by a proline (FXFP), which is usually 6–10 amino acids C-terminal to the phosphorylation site [42]. The F-domain has been identified in a variety of ERK1/2 substrates such as transcription factors, putative scaffolding proteins, and phosphatases [43]. Some ERK1/2 substrates contain both the D and F domains, which may act cooperatively in facilitating protein interactions and the efficient phosphorylation of substrate proteins by ERK1/2 [42]. For example, individual mutations of either the D or F-domains reduced but did not eliminate transcription factor activation of the ERK1/2 substrate, Elk-1, in cultured cells [42]. However, mutations of both the F-domain and D-domain completely inhibited Elk-1 activity suggesting that proper activation by ERK proteins required both docking domains. It is likely that additional substrate binding motifs will be revealed to further clarify the understanding of substrate specific interactions with the MAP kinases.

DOCKING DOMAINS ON MAP KINASES

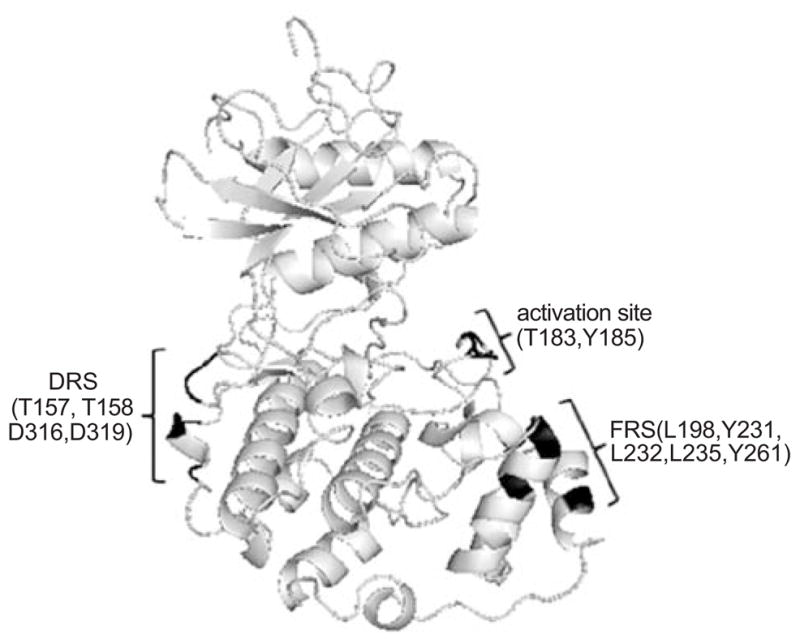

The D and F-domains on substrate proteins interact with specific docking domains on the ERK1/2 proteins. Recent studies have revealed new information about the nature of these ERK docking domains and how they confer specificity. The first ERK docking domain to be identified was referred to as the common docking or CD domain (Fig. 3) [44, 45]. Interestingly, the CD domain, also referred to as the D-recruitment site (DRS) [46], is located on the side of ERK2 opposite the MAP kinase activation lip. The CD domain consists of aspartate residues 316 and 319 (numbered according to ERK2). Similarly, ERK1 and other MAP kinases have acidic residues in the same region of their 3D structures [45, 47]. Contacts between the D-domain of substrate proteins and the CD domain of ERK proteins include ionic interactions between the basic lysine/arginine and the acidic aspartate residues as well as hydrophobic interactions [44, 47]. The CD domain of ERK2 has been shown to facilitate interactions with the upstream activating MEK1/2 proteins and the regulatory MAP kinase phosphatase-3 (MKP-3) protein [48]. Mutagenesis of the aspartate residues on the ERK DRS or basic residues of the D-domain on substrate proteins can effectively disrupt these protein-protein interactions [44]. Similar binding interactions and docking sites have been reported between upstream activators, downstream effectors, and regulatory phosphatases of the p38 and JNK MAP kinases [47]. These data indicated that all of the major MAP kinase family members use a common docking region to mediate substrate interactions [44].

Fig. 3.

Ribbon structure of ERK2 highlighting the amino acid residues (shown in black) that make up the DRS and FRS substrate docking sites. The position of the threonine and tyrosine residues that are phosphorylated in the activation site are also shown and highlighted in black.

Despite common features of the CD domain among the MAP kinases, other docking site residues near the CD domain have been identified and may contribute to substrate specificity within the MAP kinase family members. Adjacent to the CD domain is another substrate docking site referred to as the ED domain (named for a glutamate 160 and aspartate 161 on p38α MAP kinase). The ED domain on ERK2 consists of threonine residues on position 157 and 158 (Fig. 3) [45]. Exchanging the ED residues on ERK2 with the ED site residues of p38 MAP kinase altered substrate recognition suggesting that this site confers specificity [45]. However, p38 MAP kinase mutants containing the ERK2 CD and ED domains did not demonstrate a preference towards ERK2-specific substrates, indicating that additional amino acids are involved in the recognition of these substrates [45]. To support this idea, recent findings indicate that the two amino acids C-terminal to the ED site also play a role in ERK selectivity towards the phosphorylation and inactivation of the pro-apoptotic protein, caspase-9 [49]. In these studies, the variability in the ED and adjacent residues between MAP kinases determined ERK specificity towards caspase-9.

Studies evaluating solvent protection as measured by deuterium exchange and mass spectrometry revealed hydrophobic regions near the activation lip of ERK2 that were responsible for interactions with the F-site of substrates [50]. These residues include L198, Y231, L232, L235, and Y261 and may also be referred to as the F-recruitment site (FRS) (Fig. 3). Mutating these hydrophobic residues to alanine inhibited interactions between ERK2 and F-site-containing proteins Elk-1 and nucleoporin-153, a member of the nuclear pore complex, in GST-pulldown assays [50]. Thus, the unique features of the DRS and FRS on MAP kinases may be utilized in the development of novel MAP kinase inhibitors that are also substrate selective.

DEVELOPING ERK1/2-SPECIFIC INHIBITORS

Traditional drug discovery projects first develop the appropriate in vitro and cell-based assays to screen large chemical libraries and assess effects on target kinase activity or a cellular response. Once active compounds are identified, chemical modifications and refinement of these lead molecules are made to reach greater inhibition in both the in vitro and cell-based models [51]. This approach has been successful in identifying potentially specific compounds with a desired effect from a large pool of lead compounds. However, this approach has often made the understanding of mechanistic information about the compound a secondary consideration. As crystal structures of the MAP kinases were reported and computer modeling of protein-inhibitor interactions became possible [52], a second approach became available in which compounds were designed to bind to specific regions on the MAP kinases. These regions are either the ATP-binding domain or non-catalytic substrate binding domains [53–55]. This approach allows for specific, directed modifications to be made to the most active compounds based on the kinase structural features and modeling information. This approach, in combination with testing in biological assays, may produce highly specific compounds with better information on mechanism of action. These two approaches are by no means mutually exclusive, and recent reports have used both lead compound screening and detailed molecular modeling to identify MAP kinase inhibitors [53–56]. Using the structural features of ERK1/2 proteins as a guide, the focus of this review will shift to the development of inhibitors that directly target the ERK MAP kinases through interference with ATP binding or by targeting substrate-docking domains.

ATP-DEPENDENT ERK INHIBITORS

The majority of MAP kinase inhibitors identified to date bind to the ATP-binding pocket. Kinase activity is inhibited through competition of the compound with ATP and the subsequent inhibition of phospho-transfer to the substrate protein. While inhibition of ATP is certainly effective, one potential problem with this approach is that these inhibitors must compete with the relatively high concentrations of ATP found in vivo, thereby increasing the inhibitors IC50 and potential for off-target effects. In addition, because the ATP-binding domain is a relatively well-conserved region among many kinases, questions have been raised regarding the specificity achievable by targeting this domain [57–59]. As mentioned previously, a better understanding of the catalytic binding sites can overcome issues of specificity when targeting inhibitors to this site. Nonetheless, this potential problem underscores the importance of assaying a broad range of protein kinase family members when testing for compound specificity.

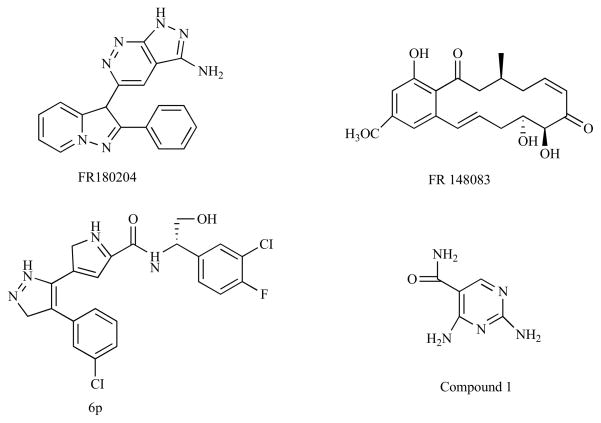

Recent studies have made progress towards identifying selective ERK inhibitors that interfere with the ATP binding pocket [60]. In screening a chemical library for inhibitors of ERK1/2-mediated phosphorylation of myelin basic protein (MBP), a promising compound, referred to as FR180204, inhibited recombinant ERK1 and ERK2 activity with Ki values of 0.31 μM and 0.14 μM, respectively [60]. This compound also inhibited TGFβ activation of the ERK-targeted AP-1 transcription factor complex in cells with an IC50 of ~3 μM [60]. X-ray crystallography studies indicate that the pyrazolopyridazine ring of this compound forms hydrogen bonds with several residues including the critical lysine important for phosphate interactions and the gatekeeper, which may act to regulate the access of molecules to the ATP binding site [60]. Recent studies suggest that this compound relieves the inflammation associated with an animal model of rheumatoid arthritis [61].

Another ATP-dependent inhibitor of ERK was identified by screening compounds generated from a fermentation culture broth [62]. This compound, called FR148083, inhibits ERK2 with an IC50 value of 80 nM and interacts with the ATP binding site by forming a covalent bond with a cysteine residue that is conserved amongst several MAP kinase regulators including MEK1, MEK4, and MEK7. It turns out that this compound is also a potent inhibitor of MEK1 and may therefore have utility as a general ERK1/2 pathway inhibitor [62].

In a high throughput screen of ERK inhibitors, it was discovered that compounds based on a pyrazolylpyrrole scaffold inhibit ERK in an ATP-dependent manner with Ki values in the low micromolar range [63]. Structural studies revealed key interactions between this molecule and the critical lysine and gatekeeper residue within the ATP binding site. Based on these interactions, chemical modifications were made on a phenyl ring and an amide group, generating a compound (6p) that inhibited ERK2 with a Ki of ~2 nM, which was at least 200-times more selective towards ERK2 compared to other kinases tested [63]. In addition, this compound inhibited the proliferation of a colon carcinoma cell line with an IC50 of 0.54 μM.

Lastly, in studies evaluating the contribution of hydrogen bonding for inhibitors interacting with the ATP binding site, the crystal structure of ERK2 in complex with a pyrimidine-based molecule called compound 1 was determined [64]. Although this compound inhibits ERK2 with an IC50 of 750 nM, it also can potently inhibit receptor tyrosine kinase activity and is likely non-specific [64]. Of interest in these studies is that compound 1 could adopt different hydrogen bonding patterns within the same ATP binding site region on different kinases, which could help identify regions important for determining compound specificity. These studies indicate that non-specificity is still a barrier to overcome when targeting ATP binding sites on ERK and other kinases. However, as additional information on unique structural features of the catalytic site is generated, more selective ATP-dependent kinase inhibitors are expected to emerge. The structures of the ATP-dependent inhibitors that are somewhat selective for ERK proteins are shown in Fig. 4.

Fig. 4.

Structures of test compounds that bind to the ATP binding site of ERK2 as determined by X-ray crystallography.

ATP-INDEPENDENT ERK INHIBITORS: TARGETING SUBSTRATE-DOCKING DOMAINS

As another approach in developing ERK-selective inhibitors and to overcome the potential limitations of non-selectivity associated with targeting ATP binding, recent efforts have begun to design inhibitors that are selective for unique sites that do not affect ATP interactions. This approach is based on the ability to identify small molecular weight compounds that disrupt specific protein-protein interactions. The identification of the previously mentioned MAP kinase docking domains indicates that there are specific regions that direct the interactions with specific substrates. Although the understanding of these docking regions is still in its infancy, these sites represent regions that offer an opportunity to identify inhibitors that are substrate selective. By selective targeting of ERK substrates, one could envision the selective interference of substrates involved in pathological processes but not substrates involved in normal cellular functions, thereby reducing the toxicity associated with kinase inhibitors.

Targeted inhibition of protein-protein interactions using small molecular weight compounds has been shown to be feasible in a variety of systems [65–67]. For example, compounds that block Src homology-2 (SH2) domains inhibit interactions between active tyrosine phosphorylated receptors and SH2 domain-containing signaling proteins such as Src, Grb2, and PI3 kinase, which are involved in cancer cell proliferation and survival [68, 69], or p56lck, which is involved in T-cell activation [70]. Another example is the identification of small molecules that bind to Bcl-2 thereby blocking the anti-apoptotic function of Bcl-2 [71]. Thus, it is feasible to use low-molecular weight compounds to disrupt the interaction energies involved in protein-protein recognition. This is despite the expectation that such protein-protein interactions involve extended molecular surfaces that are significantly larger than the small molecular weight inhibitors themselves. Accordingly, the disruption of protein-protein interactions approach has been applied to the identification of low molecular weight compounds with the potential to interact with specific ERK docking domains and selectively disrupt interactions with protein substrates [55].

IN SILICO SCREENING OF ERK-TARGETED COMPOUNDS USING COMPUTER-AIDED DRUG DESIGN (CADD)

Computer-aided drug design (CADD) can be used for the rational identification of novel compounds that target specific sites in a protein and have biological activity [52, 67]. Target-based CADD takes advantage of the protein’s 3D structure. The structure is then analyzed to identify putative binding sites, and compounds that structurally complement the targeted binding site may then be selected from an in silico or virtual chemical database [72]. Structural complementarity that can predict whether a compound will have an enhanced probability of binding to a particular site on the target protein may be determined by a variety of criteria including steric fit, ligand-protein interaction energies, and hydrogen bonding [73]. The compounds selected by CADD are then screened in assays to determine their specificity of binding and regulation of the target protein, among other properties. Particularly appealing is that CADD database screening methods can typically increase the hit rates from 0.01% (i.e. 1 active compound in 10,000) or less using only experimental high-throughput screening methods to 5% or more [52, 74].

The screening of in silico databases of commercially available compounds over, for example, de novo drug design for identifying new compounds holds a particular advantage in that it eliminates the need for chemical synthesis in the initial phases of the drug discovery process, thereby greatly saving time and experimental costs. Once the CADD-selected compounds have been determined to have the desired biological activity, chemical modifications can be systematically introduced into these lead compounds to improve their effectiveness in targeting the protein of interest. Among the many successes of CADD database screening are the identification of several lead compounds that inhibit protein-protein interactions [55, 70, 73–75].

Important for the successful application of target-based CADD is the availability of the three-dimensional (3D) structure of the protein and information on potential residues involved in the binding interaction being targeted. A large number of protein 3D structures have been determined and are available through the protein databank (PDB) [76]. If the 3D structure of the intended target is not known, structural information may be obtained by virtue of the target protein’s homology with other known proteins with similar function for which the 3D structure is known. The quality of such structures and utility in CADD, however, will be largely dictated by the degree of conservation between the target protein and the protein being used as the basis of the homology model. Once the 3D structure of the protein is available, it is necessary to identify putative binding sites on the protein surface. The identification of regions within the catalytic regions, such as the ATP binding site, is reasonably trivial as this site is conserved amongst kinases. However, in the case of putative ERK binding sites involved in protein-protein interactions, the exact identification of sites, which may differ from other MAP kinases, to bind low-molecular weight compounds is not trivial. The discovery that substrate proteins interact with at least two regions (DRS and FRS) on ERK proteins provides the ideal starting point for identification of such sites, which may then be facilitated by computational approaches that characterize binding sites [72]. This combination of experimental data and computational analysis sets the foundation for the application of CADD for inhibitor identification.

The 3D structures for both the unphosphorylated (inactive; PDB code, 1ERK) and phosphorylated (active, PDB code, 2ERK) forms of ERK2 have been solved [77, 78]. To identify small molecules that interact with substrate binding sites, CADD was used to screen in silico a database of over 800,000 compounds targeting a putative binding pocket within the DRS, discussed above, on ERK2 [55]. The CADD search initially targeted the unphosphorylated 3D structure of ERK2 and employed the program DOCK [79, 80] along with the CHAOS suite of programs that were developed by the Computer Aided Drug Design center at the University of Maryland [81].

From this initial screen, ~20,000 compounds were selected based on the van der Waals (VDW) attractive energy normalized for the size of the compound [73]. The goal of the initial screen was to identify any compound that has steric complementarity to the targeted binding site. The use of the VDW attractive energy helps assure the selection of compounds that have significant shape complementarity to the binding pocket. If, for example, electrostatic interactions were included in the scoring at this stage, compounds with highly favorable electrostatic interactions may be selected, but they potentially may not have a good fit to the binding site of interest. Additional selection criteria included a size-based normalization procedure to avoid the bias of DOCK scoring towards higher molecular weight compounds and allow the selection of compounds with lead-like or drug-like properties [82, 83]. The initial 20,000 compounds selected were subjected to a second screen that included additional relaxation of the test compound during the docking process. Selection of compounds from the secondary screen was based on the total interaction energy and included size normalization. Use of the total interaction energy for scoring of test compounds included the electrostatic interactions, as only compounds that are predicted to sterically complement the binding site have been selected. From this secondary screen, ~500 compounds were selected, which can be reasonably tested in experimental assays. If the biological assays to test the compounds are low throughput, a subset of the selected compounds that have maximal chemical diversity can also be generated. This procedure involves clustering of compounds based on chemical fingerprints from which chemically similar compounds can be grouped together. From 500 compounds, approximately 100 chemically similar groups can be identified and individual compounds selected from each group can be assayed experimentally. This final selection includes consideration of solubility, size, and number of hydrogen bond acceptors and donors as required to maximize drug-like characteristics [84], although flexibility is allowed in these criteria to ensure that all compounds of interest are tested.

The above CADD approach outlined above has identified novel low molecular weight compounds that bind to ERK2 and inhibit downstream phosphorylation of ERK substrates [55, 75, 85]. This successful effort strongly supports the hypothesis that inhibitors of ERK-substrate proteins can be identified via a combination of CADD and biological assays.

METHODS FOR CHARACTERIZING ERK1/2 INHIBITORS GENERATED BY CADD

The following section provides some of the in vitro and in vivo approaches for analyzing and evaluating potential ERK inhibitors. This is by no means a comprehensive overview of all assays available, and it will not include all HTS methods that evaluate general kinase activity and effects of compounds on substrate phosphorylation. Other excellent review articles provide a comprehensive evaluation of most of the standard in vitro or cell-based HTS assays for identifying kinase inhibitors [86–88]. The goal of this section is to provide a framework for identifying ERK inhibitors with particular emphasis on evaluating molecules that interact with ERK and are selective in disrupting substrate interactions.

Fluorescence Based Assays

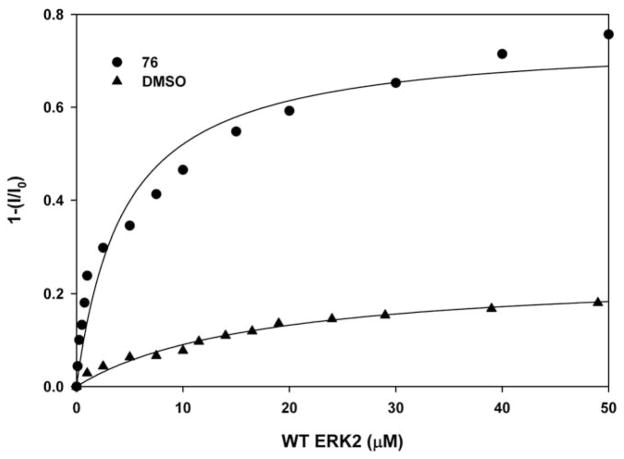

Measuring changes in protein fluorescence is a convenient approach to identify compounds that potentially interact with ERK1/2 proteins [55, 75]. The basic approach for these studies requires purified ERK protein and a spectrometer that can measure excitation/emission wavelengths between 280 and 500 nm. The ability for the spectrophotometer to adapt to a 96 or 384-well format greatly facilitates the initial screening of the several hundred compounds that will emerge from the initial CADD screen. ERK1/2 fluorescence can be measured primarily due to the presence of tryptophans. Molecular interactions can be inferred if a test compound inhibits or quenches ERK fluorescence. The quenching of the ERK fluorescence intensity following incubation with a test compound indicates a change in tertiary structure of one or more tryptophan residues to a more hydrophobic environment. Compounds that cause fluorescence quenching of ERK2 tryptophan residues are then further investigated in subsequent assays.

To evaluate fluorescence quenching, ERK2 (0.5–1 μM) is excited at 295 nm wavelength, which avoids protein absorbance at 280 nm, and fluorescence emission is monitored from 300–500 nm in the absence or presence of test compounds (0.1 μM to 50 μM). The change in fluorescence intensity can be plotted as a function of the test compound concentration to calculate a dissociation constant (KD) and binding stoichiometry [55]. A sample fluorescence quenching trace is shown in Fig. 5 where the test compound 76 causes quenching of ERK2 fluorescence compared to equivalent volumes of the control solvent DMSO [55]. The data suggest that the estimated binding affinity (KD) of compound 76 with ERK2 is 8 μM. Controls must take into account the possibility that the test compounds will absorb light or fluoresce within the measured emission wavelengths and interfere with the accurate determination of the dissociation constants. Test compounds that exhibit natural fluorescence and obscure ERK fluorescence cannot be evaluated by this method. Alternative methods, such as isothermal titration calorimetry (ITC), described in the next section, can be used to evaluate ERK-interacting compounds.

Fig. 5.

Fluorescence quenching assay with ERK2 in the presence of test compound. The degree of fluorescence quenching of ERK2 at 340 nm was plotted against increasing concentrations of test compound (76) or the DMSO control. These data suggest a KD binding affinity of approximately 8 μM for 76.

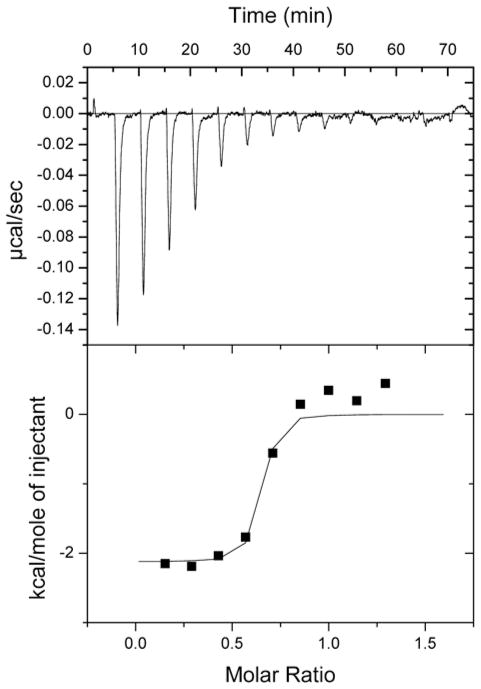

Isothermal Titration Calorimetry (ITC) Assays

ITC offers the ability to directly determine the binding association constant (Ka), the binding enthalpy (ΔH), and the binding stoichiometry of test compounds with target proteins such as ERK2. Unlike spectroscopy methods, the absorbance and fluorescence associated with small molecular weight compounds does not interfere with these determinations. Binding constants from 102 to 109 M−1 can be accurately measured, and thermodynamic properties such as the change in Gibbs free energy upon binding, ΔG, can be calculated from equation ΔG = −RT ln Ka, whereas, ΔS, the binding entropy, can be determined using the equation ΔG = ΔH − TΔS [89, 90]. For a typical ITC experiment, ERK2 (10 μM) in the cell is titrated with a test compound (100 μM). The integrated heats (μJ) for each injection as a function of the molar ratio of test compound to ERK2 are utilized for calculation of dissociation constants and binding stoichiometry. As controls, the mechanical heats of dilution, produced by the act of injecting test compounds, must be subtracted for each experiment to obtain accurate binding determinations, and the heats of dilution must include experiments where test compound is titrated in the absence of ERK2. An example of ITC data showing ERK2 interactions with a test compound targeting the region of the CD and ED substrate docking domain is shown in Fig. 6. In this case, this test compound shows nanomolar affinity towards ERK2.

Fig. 6.

A sample ITC experiment evaluating test compound interactions with ERK2. Purified ERK2 was titrated with a potential small molecular weight ERK2 docking domain inhibitor identified by CADD. The raw data and integrated heats corrected for dilutions are shown in the top and bottom panels, respectively.

The thermodynamic properties calculated by an ITC experiment can provide valuable information about the binding interactions of test compounds with ERK docking domains. The interactions of the test compound with ERK can be determined from the binding enthalpy (ΔH), which includes contributions from hydrogen bonding, van der Waals forces, and polar and dipolar interactions that are formed as previously described [91]. Therefore, compounds that exhibit favorable enthalpy can be predicted to bind to ERK specifically. Binding entropy (ΔS), however, is composed of solvation entropy, conformational entropy, and rotational-translational entropy. Solvation entropy is related to the change in solvation of ERK2 and the ligand leading to a decrease in the number of constrained water molecules upon compound binding, whereas, conformational entropy is the change in structural fluctuations of ERK2 and the ligand upon compound binding. Rotational-translational entropy, on the other hand, is associated with the change in configuration of the target protein upon binding to the test compound [91–93]. Knowledge of the thermodynamic forces contributing to binding interactions between a test compound and target protein can be used to facilitate modification of the potential inhibitors and improve affinity. Ultimately, the nature of the test compound’s interactions with ERK proteins will need to be determined through more definitive methods such as X-ray crystallography or NMR spectroscopy.

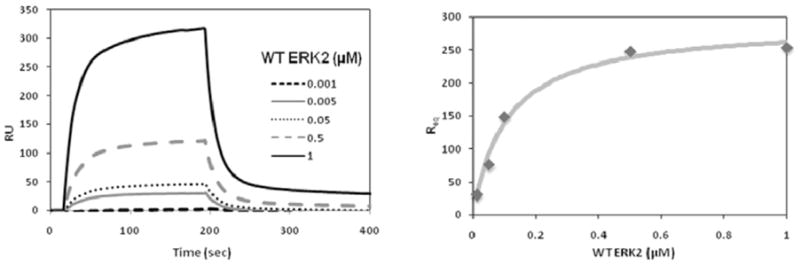

Real Time Measure of Protein-Protein Interactions: Surface Plasmon Resonance

Once test compounds that bind to ERK2 have been identified, a variety of approaches including co-immunoprecipitations and pull-down assays can be used to evaluate whether the compounds actually disrupt protein-protein interactions. One of the problems with the previously mentioned methods for analyzing protein-protein interactions is that they are difficult to quantify. As such, alternative methods such as surface plasmon resonance (SPR) can be utilized to determine, in real time, whether lead compounds can selectively inhibit ERK interactions with specific substrates. An explanation of the optical measurements used to quantify protein-protein interactions by SPR can be obtained in the following reviews [94, 95]. In applying this approach for evaluating ERK interactions, the interacting substrate of interest (ligand) is directly immobilized on a gold-plated sensorchip by direct or indirect coupling. The different sensorchips take into account the desired type of direct chemical coupling to attach the ligand, such as amine coupling to lysine, thiol coupling to cysteine, or aldehyde coupling to carbohydrates on a glycoprotein. Indirect coupling of ligand can be through an antibody, biotin-streptavidin complexes, or an oligo histidine-tagged protein that binds to nickel-nitrilotriacetic acid (Ni-NTA). The ERK protein (analyte) is injected into the chamber and allowed to flow across the bound substrate ligand. The binding of ERK to its substrate on the sensorchip surface alters the optical properties of the incident light, and this is measured as resonance units. The sensorgram, which plots the change in resonance units as a function of time, allows for the determination of an on-rate (association) when the analyte is being injected or an off-rate (dissociation) after analyte injection has been stopped. From these two rate constants, a binding affinity (KD) can be determined. Fig. 7 shows an SPR trace for the association and dissociation of ERK2 (analyte) with its substrate Rsk-1 (ligand), a D-domain-containing protein. The binding affinity (KD) of this interaction was determined to be 0.143 μM, which is consistent with other reports using fluorescence anisotropy methods that show a D-domain substrate (PEA-15) interacting with ERK proteins with a KD in the 0.2 – 0.4 μM range [96].

Fig. 7.

Evaluating ERK2 interactions with substrate proteins using surface plasmon resonance. The left panel shows the raw traces for the change in resonance units (RU) for estimating binding association and dissociation of wild type ERK2 (0.001 – 1.0 μM) as the analyte with the Rsk-1 substrate as the ligand. The right graph plots the normalized resonance units at equilibrium (Req) as a function of ERK2 concentration. The estimated binding affinity (KD) of ERK2 is 0.143 μM.

Evaluating ERK Inhibitors in Cells and Whole Organisms

A variety of cell-based models are available for evaluating ERK inhibitors. Most of these assays measure the ability for test compounds to inhibit cell proliferation or ERK-regulated transcription factor function [55, 60, 63]. In addition, the effects of test compounds on ERK-mediated substrate phosphorylation has been examined in immunoblotting assays using phosphorylation-specific antibodies [55, 75]. The use of whole organism models is also important for evaluating potential ERK inhibitors. For examples, the nematode Caenorhabditis elegans (C. elegans) has been very well characterized in terms of developmental and physiological processes and has potential use in drug discovery and development programs targeting the ERK signaling pathway [97, 98]. Importantly, C. elegans contains a MAP kinase, MPK-1, which is 80% homologous to the human ERK2, and is regulated by the same mechanisms as the ERK1/2 proteins [99]. MPK-1 functions in a receptor-mediated signaling cascade that is required for the development of the vulva structure responsible for egg laying [100]. This extensive understanding of the egg laying process and available reagents has been used to demonstrate that novel small molecular weight compounds can selectively inhibit MPK-1 substrates [85].

CONCLUSIONS

The development of ERK-specific inhibitors may have significant potential for clinical use in treating proliferative disorders and inflammatory diseases. These inhibitors may block all ERK functions by targeting the ATP binding site, or they may be selective in disrupting specific substrate interactions that might mediate pathological conditions. In the context of inflammation, several potential ERK substrates may be targeted for selective inhibition. For example selective disruption of ERK phosphorylation and activation of Rsk-1 may reduce inflammation associated with increased cyclooxygenase (COX-2) expression and activity in generating prostaglandins [101]. Another ERK substrate is the pro-TNFα-converting enzyme (TACE or ADAM17), which is a metalloprotease that regulates TNFα levels and other inflammatory signaling pathways [102]. Future studies that expand our understanding of ERK interactions with substrate proteins will facilitate the identification of new small molecular weight compounds that have the potential to selectively inhibit ERK-mediated phosphorylation events that regulate inflammation.

References

- 1.Lewis TS, Shapiro PS, Ahn NG. Signal tranduction through MAP kinase cascades. Adv Cancer Res. 1998;74:49–139. doi: 10.1016/s0065-230x(08)60765-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cobb MH, Goldsmith EJ. How MAP kinases are regulated. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:14843–14846. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.25.14843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pearson G, Robinson F, Gibson TB, Xu BE, Karandikar M, Berman K, Cobb MH. Mitogen-activated protein (MAP) kinase pathways: regulation and physiological functions. Endocr Rev. 2001;22:153–183. doi: 10.1210/edrv.22.2.0428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nishimoto S, Nishida E. MAPK signalling: ERK5 versus ERK1/2. EMBO Rep. 2006;7:782–786. doi: 10.1038/sj.embor.7400755. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Raman M, Chen W, Cobb MH. Differential regulation and properties of MAPKs. Oncogene. 2007;26:3100–3112. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1210392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Schett G, Zwerina J, Firestein G. The p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) pathway in rheumatoid arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2008;67:909–916. doi: 10.1136/ard.2007.074278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Adcock IM, Caramori G, Chung KF. New targets for drug development in asthma. Lancet. 2008;372:1073–1087. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)61449-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ivanenkov YA, Balakin KV, Tkachenko SE. New approaches to the treatment of inflammatory disease: focus on small-molecule inhibitors of signal transduction pathways. Drugs R D. 2008;9:397–434. doi: 10.2165/0126839-200809060-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pettus LH, Wurz RP. Small molecule p38 MAP kinase inhibitors for the treatment of inflammatory diseases: novel structures and developments during 2006–2008. Curr Top Med Chem. 2008;8:1452–1467. doi: 10.2174/156802608786264245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Thalhamer T, McGrath MA, Harnett MM. MAPKs and their relevance to arthritis and inflammation. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2008;47:409–414. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/kem297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hallett JM, Leitch AE, Riley NA, Duffin R, Haslett C, Rossi AG. Novel pharmacological strategies for driving inflammatory cell apoptosis and enhancing the resolution of inflammation. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2008;29:250–257. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2008.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pages G, Guerin S, Grall D, Bonino F, Smith A, Anjuere F, Auberger P, Pouyssegur J. Defective thymocyte maturation in p44 MAP kinase (Erk 1) knockout mice. Science. 1999;286:1374–1377. doi: 10.1126/science.286.5443.1374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Reuter CW, Morgan MA, Bergmann L. Targeting the Ras signaling pathway: a rational, mechanism-based treatment for hematologic malignancies? Blood. 2000;96:1655–1669. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Brose MS, Volpe P, Feldman M, Kumar M, Rishi I, Gerrero R, Einhorn E, Herlyn M, Minna J, Nicholson A, Roth JA, Albelda SM, Davies H, Cox C, Brignell G, Stephens P, Futreal PA, Wooster R, Stratton MR, Weber BL. BRAF and RAS mutations in human lung cancer and melanoma. Cancer Res. 2002;62:6997–7000. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bos JL. Ras oncogenes in human cancer: a review. Cancer Res. 1989;49:4682–4689. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Davies H, Bignell GR, Cox C, Stephens P, Edkins S, Clegg S, Teague J, Woffendin H, Garnett MJ, Bottomley W, Davis N, Dicks E, Ewing R, Floyd Y, Gray K, Hall S, Hawes R, Hughes J, Kosmidou V, Menzies A, Mould C, Parker A, Stevens C, Watt S, Hooper S, Wilson R, Jayatilake H, Gusterson BA, Cooper C, Shipley J, Hargrave D, Pritchard-Jones K, Maitland N, Chenevix-Trench G, Riggins GJ, Bigner DD, Palmieri G, Cossu A, Flanagan A, Nicholson A, Ho JW, Leung SY, Yuen ST, Weber BL, Seigler HF, Darrow TL, Paterson H, Marais R, Marshall CJ, Wooster R, Stratton MR, Futreal PA. Mutations of the BRAF gene in human cancer. Nature. 2002;417:949–954. doi: 10.1038/nature00766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mendelsohn J, Baselga J. Epidermal growth factor receptor targeting in cancer. Semin Oncol. 2006;33:369–385. doi: 10.1053/j.seminoncol.2006.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kolch W, Kotwaliwale A, Vass K, Janosch P. The role of Raf kinases in malignant transformation. Expert Rev Mol Med. 2002;4:1–18. doi: 10.1017/S1462399402004386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Murphy LO, Smith S, Chen RH, Fingar DC, Blenis J. Molecular interpretation of ERK signal duration by immediate early gene products. Nat Cell Biol. 2002;4:556–564. doi: 10.1038/ncb822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Willems A, Gauger K, Henrichs C, Harbeck N. Antibody therapy for breast cancer. Anticancer Res. 2005;25:1483–1489. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Arora A, Scholar EM. Role of tyrosine kinase inhibitors in cancer therapy. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2005;315:971–979. doi: 10.1124/jpet.105.084145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Appels NM, Beijnen JH, Schellens JH. Development of farnesyl transferase inhibitors: a review. Oncologist. 2005;10:565–578. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.10-8-565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lowinger TB, Riedl B, Dumas J, Smith RA. Design and discovery of small molecules targeting raf-1 kinase. Curr Pharm Des. 2002;8:2269–2278. doi: 10.2174/1381612023393125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wilhelm SM, Carter C, Tang L, Wilkie D, McNabola A, Rong H, Chen C, Zhang X, Vincent P, McHugh M, Cao Y, Shujath J, Gawlak S, Eveleigh D, Rowley B, Liu L, Adnane L, Lynch M, Auclair D, Taylor I, Gedrich R, Voznesensky A, Riedl B, Post LE, Bollag G, Trail PA. BAY 43–9006 exhibits broad spectrum oral antitumor activity and targets the RAF/MEK/ERK pathway and receptor tyrosine kinases involved in tumor progression and angiogenesis. Cancer Res. 2004;64:7099–7109. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-1443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Friday BB, Adjei AA. Advances in targeting the Ras/Raf/MEK/Erk mitogen-activated protein kinase cascade with MEK inhibitors for cancer therapy. Clin Cancer Res. 2008;14:342–346. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-07-4790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Liao JJ. Molecular recognition of protein kinase binding pockets for design of potent and selective kinase inhibitors. J Med Chem. 2007;50:409–424. doi: 10.1021/jm0608107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Levitzki A. Tyrosine kinases as targets for cancer therapy. Eur J Cancer. 2002;38(Suppl 5):S11–S18. doi: 10.1016/s0959-8049(02)80598-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nolen B, Taylor S, Ghosh G. Regulation of protein kinases; controlling activity through activation segment conformation. Mol Cell. 2004;15:661–675. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2004.08.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wang Z, Canagarajah BJ, Boehm JC, Kassisa S, Cobb MH, Young PR, Abdel-Meguid S, Adams JL, Goldsmith EJ. Structural basis of inhibitor selectivity in MAP kinases. Structure. 1998;6:1117–1128. doi: 10.1016/s0969-2126(98)00113-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Vieth M, Higgs RE, Robertson DH, Shapiro M, Gragg EA, Hemmerle H. Kinomics-structural biology and chemogenomics of kinase inhibitors and targets. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2004;1697:243–257. doi: 10.1016/j.bbapap.2003.11.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yang SH, Whitmarsh AJ, Davis RJ, Sharrocks AD. Differential targeting of MAP kinases to the ETS-domain transcription factor Elk-1. EMBO J. 1998;17:1740–1749. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.6.1740. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Yang SH, Yates PR, Whitmarsh AJ, Davis RJ, Sharrocks AD. The Elk-1 ETS-domain transcription factor contains a mitogen-activated protein kinase targeting motif. Mol Cell Biol. 1998;18:710–720. doi: 10.1128/mcb.18.2.710. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Galanis A, Yang SH, Sharrocks AD. Selective targeting of MAPKs to the ETS domain transcription factor SAP-1. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:965–973. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M007697200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sharrocks AD, Yang SH, Galanis A. Docking domains and substrate-specificity determination for MAP kinases. Trends Biochem Sci. 2000;25:448–453. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0004(00)01627-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bardwell L, Thorner J. A conserved motif at the amino termini of MEKs might mediate high-affinity interaction with the cognate MAPKs. Trends Biochem Sci. 1996;21:373–374. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Xu B, Wilsbacher JL, Collisson T, Cobb MH. The N-terminal ERK-binding site of MEK1 is required for efficient feedback phosphorylation by ERK2 in vitro and ERK activation in vivo. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:34029–34035. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.48.34029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Smith JA, Poteet-Smith CE, Malarkey K, Sturgill TW. Identification of an extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK) docking site in ribosomal S6 kinase, a sequence critical for activation by ERK in vivo. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:2893–2898. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.5.2893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zuniga A, Torres J, Ubeda J, Pulido R. Interaction of mitogen-activated protein kinases with the kinase interaction motif of the tyrosine phosphatase PTP-SL provides substrate specificity and retains ERK2 in the cytoplasm. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:21900–21907. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.31.21900. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Johnson TR, Biggs JR, Winbourn SE, Kraft AS. Regulation of dual-specificity phosphatases M3/6 and hVH5 by phorbol esters. Analysis of a delta-like domain. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:31755–31762. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M004182200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Nichols A, Camps M, Gillieron C, Chabert C, Brunet A, Wilsbacher J, Cobb M, Pouyssegur J, Shaw JP, Arkinstall S. Substrate recognition domains within extracellular signal-regulated kinase mediate binding and catalytic activation of mitogen-activated protein kinase phosphatase-3. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:24613–24621. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M001515200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Karin M. The regulation of AP-1 activity by mitogen-activated protein kinases. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:16483–16486. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.28.16483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Fantz DA, Jacobs D, Glossip D, Kornfeld K. Docking sites on substrate proteins direct extracellular signal-regulated kinase to phosphorylate specific residues. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:27256–27265. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M102512200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Jacobs D, Beitel GJ, Clark SG, Horvitz HR, Kornfeld K. Gain-of-function mutations in the Caenorhabditis elegans lin-1 ETS gene identify a C-terminal regulatory domain phosphorylated by ERK MAP kinase. Genetics. 1998;149:1809–1822. doi: 10.1093/genetics/149.4.1809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Tanoue T, Adachi M, Moriguchi T, Nishida E. A conserved docking motif in MAP kinases common to substrates, activators and regulators. Nat Cell Biol. 2000;2:110–116. doi: 10.1038/35000065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Tanoue T, Maeda R, Adachi M, Nishida E. Identification of a docking groove on ERK and p38 MAP kinases that regulates the specificity of docking interactions. EMBO J. 2001;20:466–479. doi: 10.1093/emboj/20.3.466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Callaway K, Abramczyk O, Martin L, Dalby KN. The anti-apoptotic protein PEA-15 is a tight binding inhibitor of ERK1 and ERK2, which blocks docking interactions at the D-recruitment site. Biochemistry. 2007;46:9187–9198. doi: 10.1021/bi700206u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Tanoue T, Nishida E. Docking interactions in the mitogen-activated protein kinase cascades. Pharmacol Ther. 2002;93:193–202. doi: 10.1016/s0163-7258(02)00188-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Zhang J, Zhou B, Zheng CF, Zhang ZY. A bipartite mechanism for ERK2 recognition by its cognate regulators and substrates. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:29901–29912. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M303909200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Martin MC, Allan LA, Mancini EJ, Clarke PR. The docking interaction of caspase-9 with ERK2 provides a mechanism for the selective inhibitory phosphorylation of caspase-9 at threonine 125. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:3854–3865. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M705647200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Lee T, Hoofnagle AN, Kabuyama Y, Stroud J, Min X, Goldsmith EJ, Chen L, Resing KA, Ahn NG. Docking motif interactions in MAP kinases revealed by hydrogen exchange mass spectrometry. Mol Cell. 2004;14:43–55. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(04)00161-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Jackson PF, Bullington JL. Pyridinylimidazole based p38 MAP kinase inhibitors. Curr Top Med Chem. 2002;2:1011–1020. doi: 10.2174/1568026023393372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Gohlke H, Klebe G. Approaches to the description and prediction of the binding affinity of small-molecule ligands to macromolecular receptors. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 2002;41:2644–2676. doi: 10.1002/1521-3773(20020802)41:15<2644::AID-ANIE2644>3.0.CO;2-O. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Pargellis C, Tong L, Churchill L, Cirillo PF, Gilmore T, Graham AG, Grob PM, Hickey ER, Moss N, Pav S, Regan J. Inhibition of p38 MAP kinase by utilizing a novel allosteric binding site. Nat Struct Biol. 2002;9:268–272. doi: 10.1038/nsb770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Regan J, Breitfelder S, Cirillo P, Gilmore T, Graham AG, Hickey E, Klaus B, Madwed J, Moriak M, Moss N, Pargellis C, Pav S, Proto A, Swinamer A, Tong L, Torcellini C. Pyrazole urea-based inhibitors of p38 MAP kinase: from lead compound to clinical candidate. J Med Chem. 2002;45:2994–3008. doi: 10.1021/jm020057r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Hancock CN, Macias A, Lee EK, Yu SY, Mackerell AD, Jr, Shapiro P. Identification of novel extracellular signal-regulated kinase docking domain inhibitors. J Med Chem. 2005;48:4586–4595. doi: 10.1021/jm0501174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Davidson W, Frego L, Peet GW, Kroe RR, Labadia ME, Lukas SM, Snow RJ, Jakes S, Grygon CA, Pargellis C, Werneburg BG. Discovery and characterization of a substrate selective p38alpha inhibitor. Biochemistry. 2004;43:11658–11671. doi: 10.1021/bi0495073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Davies SP, Reddy H, Caivano M, Cohen P. Specificity and mechanism of action of some commonly used protein kinase inhibitors. Biochem J. 2000;351:95–105. doi: 10.1042/0264-6021:3510095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Bain J, McLauchlan H, Elliott M, Cohen P. The specificities of protein kinase inhibitors: an update. Biochem J. 2003;371:199–204. doi: 10.1042/BJ20021535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Fabian MA, Biggs WH, 3rd, Treiber DK, Atteridge CE, Azimioara MD, Benedetti MG, Carter TA, Ciceri P, Edeen PT, Floyd M, Ford JM, Galvin M, Gerlach JL, Grotzfeld RM, Herrgard S, Insko DE, Insko MA, Lai AG, Lelias JM, Mehta SA, Milanov ZV, Velasco AM, Wodicka LM, Patel HK, Zarrinkar PP, Lockhart DJ. A small molecule-kinase interaction map for clinical kinase inhibitors. Nat Biotechnol. 2005;23:329–336. doi: 10.1038/nbt1068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Ohori M, Kinoshita T, Okubo M, Sato K, Yamazaki A, Arakawa H, Nishimura S, Inamura N, Nakajima H, Neya M, Miyake H, Fujii T. Identification of a selective ERK inhibitor and structural determination of the inhibitor-ERK2 complex. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2005;336:357–363. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2005.08.082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Ohori M. ERK inhibitors as a potential new therapy for rheumatoid arthritis. Drug News Perspect. 2008;21:245–250. doi: 10.1358/DNP.2008.21.5.1219006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Ohori M, Kinoshita T, Yoshimura S, Warizaya M, Nakajima H, Miyake H. Role of a cysteine residue in the active site of ERK and the MAPKK family. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2007;353:633–637. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2006.12.083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Aronov AM, Baker C, Bemis GW, Cao J, Chen G, Ford PJ, Germann UA, Green J, Hale MR, Jacobs M, Janetka JW, Maltais F, Martinez-Botella G, Namchuk MN, Straub J, Tang Q, Xie X. Flipped out: structure-guided design of selective pyrazolylpyrrole ERK inhibitors. J Med Chem. 2007;50:1280–1287. doi: 10.1021/jm061381f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Katayama N, Orita M, Yamaguchi T, Hisamichi H, Kuromitsu S, Kurihara H, Sakashita H, Matsumoto Y, Fujita S, Niimi T. Identification of a key element for hydrogen-bonding patterns between protein kinases and their inhibitors. Proteins. 2008;73:795–801. doi: 10.1002/prot.22207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Cochran AG. Protein-protein interfaces: mimics and inhibitors. Curr Opin Chem Biol. 2001;5:654–659. doi: 10.1016/s1367-5931(01)00262-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Cochran AG. Antagonists of protein-protein interactions. Chem Biol. 2000;7:R85–94. doi: 10.1016/s1074-5521(00)00106-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Zhong S, Macias AT, MacKerell AD., Jr Computational identification of inhibitors of protein-protein interactions. Curr Top Med Chem. 2007;7:63–82. doi: 10.2174/156802607779318334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Cody WL, Lin Z, Panek RL, Rose DW, Rubin JR. Progress in the development of inhibitors of SH2 domains. Curr Pharm Des. 2000;6:59–98. doi: 10.2174/1381612003401532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Garcia-Echeverria C. Antagonists of the Src homology 2 (SH2) domains of Grb2, Src, Lck and ZAP-70. Curr Med Chem. 2001;8:1589–1604. doi: 10.2174/0929867013371905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Huang N, Nagarsekar A, Xia G, Hayashi J, MacKerell AD., Jr Identification of non-phosphate-containing small molecular weight inhibitors of the tyrosine kinase p56 Lck SH2 domain via in silico screening against the pY + 3 binding site. J Med Chem. 2004;47:3502–3511. doi: 10.1021/jm030470e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Enyedy IJ, Ling Y, Nacro K, Tomita Y, Wu X, Cao Y, Guo R, Li B, Zhu X, Huang Y, Long YQ, Roller PP, Yang D, Wang S. Discovery of small-molecule inhibitors of Bcl-2 through structure-based computer screening. J Med Chem. 2001;44:4313–4324. doi: 10.1021/jm010016f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Zhong S, MacKerell AD., Jr Binding response: a descriptor for selecting ligand binding site on protein surfaces. J Chem Inf Model. 2007;47:2303–2315. doi: 10.1021/ci700149k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Pan Y, Huang N, Cho S, MacKerell AD., Jr Consideration of molecular weight during compound selection in virtual target-based database screening. J Chem Inf Comput Sci. 2003;43:267–272. doi: 10.1021/ci020055f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Chen IJ, Neamati N, MacKerell AD., Jr Structure-based inhibitor design targeting HIV-1 integrase. Curr Drug Targets Infect Disord. 2002;2:217–234. doi: 10.2174/1568005023342380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Chen F, Hancock CN, Macias AT, Joh J, Still K, Zhong S, MacKerell AD, Jr, Shapiro P. Characterization of ATP-independent ERK inhibitors identified through in silico analysis of the active ERK2 structure. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2006;16:6281–6287. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2006.09.038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Westbrook J, Feng Z, Jain S, Bhat TN, Thanki N, Ravichandran V, Gilliland GL, Bluhm W, Weissig H, Greer DS, Bourne PE, Berman HM. The Protein Data Bank: unifying the archive. Nucleic Acids Res. 2002;30:245–248. doi: 10.1093/nar/30.1.245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Zhang F, Strand A, Robbins D, Cobb MH, Goldsmith EJ. Atomic structure of the MAP kinase ERK2 at 2.3 A resolution [see comments] Nature. 1994;367:704–711. doi: 10.1038/367704a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Canagarajah BJ, Khokhlatchev A, Cobb MH, Goldsmith EJ. Activation mechanism of the MAP kinase ERK2 by dual phosphorylation. Cell. 1997;90:859–869. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80351-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Kuntz ID, Blaney JM, Oatley SJ, Langridge R, Ferrin TE. A geometric approach to macromolecule-ligand interactions. J Mol Biol. 1982;161:269–288. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(82)90153-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Kuntz ID. Structure-based strategies of drug discovery and design. Science. 1992;257:1078–1082. doi: 10.1126/science.257.5073.1078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Huang N, Nagarsekar A, Xia G, Hayashi J, MacKerell AD., Jr Identification of inhibitors targeting the pY+3 binding site of the tyrosine kinase p53lck SH2 domain. J Med Chem. 2004;47:3502–3511. doi: 10.1021/jm030470e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Opera TI. Property distribution of drug-related chemical databases. J Comput-Aided Mol Des. 2000;14:251–264. doi: 10.1023/a:1008130001697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Oprea TI, Davis AM, Teague SJ, Leeson PD. Is there a difference between leads and drugs? A historical perspective. J Chem Inf Comp Sci. 2001;41:1308–1315. doi: 10.1021/ci010366a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Lipinski CA. Drug-like properties and the causes of poor solubility and poor permeability. J Pharmacol Toxicol Methods. 2000;44:235–249. doi: 10.1016/s1056-8719(00)00107-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Chen F, Mackerell AD, Jr, Luo Y, Shapiro P. Using Caenorhabditis elegans as a model organism for evaluating extracellular signal-regulated kinase docking domain inhibitors. J Cell Commun Signal. 2008;2:81–92. doi: 10.1007/s12079-008-0034-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Wesche H, Xiao SH, Young SW. High throughput screening for protein kinase inhibitors. Comb Chem High Throughput Screen. 2005;8:181–195. doi: 10.2174/1386207053258514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.von Ahsen O, Bomer U. High-throughput screening for kinase inhibitors. Chembiochem. 2005;6:481–490. doi: 10.1002/cbic.200400211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Minor LK. Assays to measure the activation of membrane tyrosine kinase receptors: focus on cellular methods. Curr Opin Drug Discov Devel. 2003;6:760–765. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Leavitt S, Freire E. Direct measurement of protein binding energetics by isothermal titration calorimetry. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 2001;11:560–566. doi: 10.1016/s0959-440x(00)00248-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Weber PC, Salemme FR. Applications of calorimetric methods to drug discovery and the study of protein interactions. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 2003;13:115–121. doi: 10.1016/s0959-440x(03)00003-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Evans LJ, Labeit S, Cooper A, Bond LH, Lakey JH. The central domain of colicin N possesses the receptor recognition site but not the binding affinity of the whole toxin. Biochemistry. 1996;35:15143–15148. doi: 10.1021/bi9615497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Raggett EM, Bainbridge G, Evans LJ, Cooper A, Lakey JH. Discovery of critical Tol A-binding residues in the bactericidal toxin colicin N: a biophysical approach. Mol Microbiol. 1998;28:1335–1343. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1998.00899.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Cooper A, Johnson CM, Lakey JH, Nollmann M. Heat does not come in different colours: entropy-enthalpy compensation, free energy windows, quantum confinement, pressure perturbation calorimetry, solvation and the multiple causes of heat capacity effects in biomolecular interactions. Biophys Chem. 2001;93:215–230. doi: 10.1016/s0301-4622(01)00222-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Malmqvist M. Surface plasmon resonance for detection and measurement of antibody-antigen affinity and kinetics. Curr Opin Immunol. 1993;5:282–286. doi: 10.1016/0952-7915(93)90019-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Piliarik M, Vaisocherova H, Homola J. Surface plasmon resonance biosensing. Methods Mol Biol. 2009;503:65–88. doi: 10.1007/978-1-60327-567-5_5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Callaway K, Rainey MA, Dalby KN. Quantifying ERK2-protein interactions by fluorescence anisotropy: PEA-15 inhibits ERK2 by blocking the binding of DEJL domains. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2005;1754:316–323. doi: 10.1016/j.bbapap.2005.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Reiner DJ, Gonzalez-Perez V, Der CJ, Cox AD. Use of Caenorhabditis elegans to evaluate inhibitors of Ras function in vivo. Methods Enzymol. 2008;439:425–449. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(07)00430-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Artal-Sanz M, de Jong L, Tavernarakis N. Caenorhabditis elegans: a versatile platform for drug discovery. Biotechnol J. 2006;1:1405–1418. doi: 10.1002/biot.200600176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Wu Y, Han M. Suppression of activated Let-60 ras protein defines a role of Caenorhabditis elegans Sur-1 MAP kinase in vulval differentiation. Genes Dev. 1994;8:147–159. doi: 10.1101/gad.8.2.147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Lackner MR, Kornfeld K, Miller LM, Horvitz HR, Kim SK. A MAP kinase homolog, mpk-1, is involved in ras-mediated induction of vulval cell fates in Caenorhabditis elegans. Genes Dev. 1994;8:160–173. doi: 10.1101/gad.8.2.160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Eliopoulos AG, Dumitru CD, Wang CC, Cho J, Tsichlis PN. Induction of COX-2 by LPS in macrophages is regulated by Tpl2-dependent CREB activation signals. EMBO J. 2002;21:4831–4840. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdf478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Diaz-Rodriguez E, Montero JC, Esparis-Ogando A, Yuste L, Pandiella A. Extracellular signal-regulated kinase phosphorylates tumor necrosis factor alpha-converting enzyme at threonine 735: a potential role in regulated shedding. Mol Biol Cell. 2002;13:2031–2044. doi: 10.1091/mbc.01-11-0561. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]