Abstract

We use longitudinal data from the Panel Study of Income Dynamics, data from three U.S. censuses, and techniques of spatial data analysis to examine how the composition of extralocal areas – those areas surrounding a householder’s neighborhood of residence – affect the likelihood that whites will move out of their neighborhood. Net of the influence of local neighborhood conditions and other predictors of residential mobility, high concentrations of minorities in surrounding neighborhoods reduce the likelihood that white householders will move, presumably by reducing the attractiveness of the most likely residential alternatives. This effect suppresses the influence of the racial composition of the immediate neighborhood so that controlling for extralocal conditions provides substantially greater support for the white flight thesis than has previously been observed. We also find that recent growth in the size of the extralocal minority population increases the likelihood of white out-migration and accounts for much of the influence previously attributed to racial change in the local neighborhood. Finally, high levels of minority concentration in surrounding neighborhoods exacerbate the positive effect of local minority concentration on white out-migration. These results highlight the importance of looking beyond reactions to local racial conditions to understand mobility decisions and resulting patterns of segregation.

Spurred by growing recognition of the detrimental impacts of racial residential segregation and spatially concentrated poverty, recent research has focused on the processes of residential mobility through which individuals and families attain residence in neighborhoods of varying racial and socioeconomic status (e.g., Crowder and South 2005; Massey et al. 1994; Quillian 2002; South et al. 2005). To date, this research has focused mainly on the influences of individual- and family-level characteristics on the probability of undertaking a move and the choice of destinations. And, while characteristics of the immediate neighborhood of residence have occasionally been considered as predictors of out-migration (Boehm and Ihlandfeldt 1986; Crowder 2000; Lee et al. 1994), past research has tended to treat neighborhoods as isolated islands, largely divorced from their broader social, geographic, and economic context. Despite theoretical arguments that patterns of residential change are influenced as much by conditions in surrounding areas as those in the immediate neighborhood (Sampson et al. 1999; Wilson and Taub 2006), data limitations and methodological complexities have prevented researchers from examining how these conditions of extralocal areas – areas surrounding the neighborhood of residence – affect individual migration behavior. Similarly, we know little about how the effects of established individual-level or neighborhood-level characteristics complement and interact with the sociodemographic characteristics of other geographically and socially linked areas. As a result, our current understanding of the factors affecting individual migration behavior--and the broader population distributions that they shape--is incomplete.

This lack of attention to extralocal contextual conditions is especially problematic in the context of studying residential segregation by race. Some of the key theoretical arguments informing research on this topic imply that migration-related decisions of individual householders, and the patterns of neighborhood change and segregation that they produce, are affected not only by the racial composition of the immediate neighborhood, but also by the composition of surrounding areas. Most notably, the white flight thesis and related models of neighborhood change imply that whites not only tend to flee neighborhoods with large shares of minorities (Krysan 2002a), but that they may be especially sensitive to such compositional characteristics when surrounding areas also contain large shares of minorities or are undergoing significant racial change (Denton and Massey 1991; Molotch 1972). These arguments suggest that a full understanding of the individual-level behaviors that shape neighborhood racial change and maintain high levels of racial residential segregation requires attention to the effects of both local neighborhood conditions and extralocal neighborhood conditions, and the interaction between the two.

This paper provides a first examination of how the racial composition of extralocal areas affects the migration behavior of white households. Using individual-level data from the Panel Study of Income Dynamics (PSID), neighborhood-level data from three U.S. censuses, and techniques of spatial data analysis, we address several interrelated questions: 1) Does the racial composition of populations in surrounding neighborhoods exert an influence on white householders’ likelihood of leaving the neighborhood of residence, independent of the effects of racial and socioeconomic conditions in the immediate neighborhood of residence? 2) If extralocal neighborhood conditions are important, is it the static composition of the population or changes in this composition that have the strongest influence on neighborhood out-migration? 3) Do concentrations of minority populations in extralocal neighborhoods alter white householders’ response to the composition of the population in their immediate neighborhood of residence? In particular, do high concentrations of minorities in geographically-proximate neighborhoods exacerbate the effect of local minority concentration on white out-migration?

THEORETICAL BACKGROUND AND HYPOTHESES

In its simplest form, the white flight thesis suggests that the aversion of white householders to living in racially-integrated settings leads them to vacate neighborhoods occupied by large or growing minority populations, and that this exodus from integrating neighborhoods helps to bolster residential segregation by race. This argument is generally consistent with results of a number of studies showing a weak preference for integrated neighborhoods among white survey respondents. While white racial attitudes have apparently become more liberal over time (Farley et al. 1994), even by the 1990s a sizable percentage of white participants in the Detroit Area Study and the Multi-City Study of Urban Inequality expressed a reluctance to remain in a moderately integrated neighborhood, and the percentage reporting that they would move out of a hypothetical neighborhood increases with the concentration of African Americans (Charles 2006; Krysan 2002a). Moreover, based on both an aversion to living near black neighbors and exaggerated estimates of crime and other problems in racially-integrated neighborhoods (Quillian and Pager 2001), white respondents tend to rate integrated neighborhoods as substantially less desirable than predominantly white neighborhoods (Krysan 2002b).

To date, most evidence regarding the veracity of the white flight thesis has come from studies relying on aggregate data to identify patterns and processes of neighborhood turnover. While a number of these studies have pointed to important variations in the pace and timing of the process of neighborhood turnover, this body of literature provides fairly consistent evidence that white populations tend to decline following the introduction of racial and ethnic minorities to the neighborhood (e.g., Denton and Massey 1991; Duncan and Duncan 1957; Guest and Zuiches 1972; Lee and Wood 1991; Taeuber and Taeuber 1965). However, studies in this tradition provide only indirect evidence on the white flight thesis because the reliance on aggregate-level data makes it difficult to distinguish the influence of the racial composition of the local neighborhood from the influence of other factors that might influence either aggregate population change or the individual migration behaviors that sustain high levels of residential segregation. In fact, a number of authors have argued that white migration from integrated neighborhoods is driven primarily by the same life cycle and housing characteristics that motivate moving in general, and that the racial composition of neighborhoods plays at best a minor role in this calculus (Ellen 2000; Frey 1979; Guest and Zuiches 1972; Molotch 1972). Similarly, some researchers have suggested that it is the reaction to nonracial characteristics of the neighborhood, and not the aversion to sharing a neighborhood with minority-group members per se, that motivates whites to devalue or leave integrated neighborhoods (Harris 1999; Keating 1994; Taub et al. 1984). Specifically, these arguments suggest that the migration of whites from racially-integrated neighborhoods reflects whites’ desire to avoid residence in neighborhoods with unstable populations, large numbers of poor residents, weak ties between neighbors, or other undesirable social and economic conditions that may be concentrated in minority-populated neighborhoods.

In order to provide more direct evidence on the individual-level implications of the white flight thesis, Crowder (2000) merged data from the 1979 to 1985 waves of the Panel Study of Income Dynamics to U.S. census data to examine the net impact of neighborhood racial composition on the likelihood of individual white householders moving away from their neighborhood of residence. This study found that for white respondents, the likelihood of moving out of the neighborhood increased modestly, but significantly, with the relative size of the non-white minority population in the neighborhood. Providing some evidence of racially-motivated white flight, the effects of local neighborhood racial composition remained significant even after controlling for a wide range of individual-level predictors of residential mobility and indicators of the social and economic condition of the neighborhood. Furthermore, consistent with previous studies of aggregate neighborhood change (e.g., Denton and Massey 1991), Crowder (2000) found that the likelihood of white out-migration was especially high from those areas in which the minority population was made up of sizable proportions of multiple racial and ethnic groups, suggesting that whites are reluctant to remain in racially and ethnically diverse neighborhoods. Finally, Crowder (2000) found that that white out-migration was positively associated with recent increases in the size of the black population in the area. This finding was interpreted as supporting the idea that white householders perceive changes in the composition of their neighborhood as clues about the future trajectory of the area and seek to leave their neighborhood when these clues suggest a growing minority presence.

Yet even this individual-level support for the white flight thesis is incomplete in that it fails to fully address the broader context in which migration decisions are made. Most importantly, it ignores the ways in which white mobility decisions might be shaped not only by the composition of the immediate local neighborhood, but also by conditions in surrounding, extralocal neighborhoods. Past studies provide some clues that such extralocal conditions may be important. For example, Sampson and his colleagues (1999: 637) point out that, because housing values and appreciation rates in a given neighborhood are partially dependent on the characteristics of nearby communities, housing-related mobility decisions will be influenced by the “…quality of a neighborhood relative to the quality of neighborhoods that surround it.” Similarly, the white residents in Wilson and Taub’s (2006) ethnographic study clearly express concerns over changing racial conditions in nearby neighborhoods.

Aggregate-level studies have found that a neighborhood’s proximity to other areas with established black populations is among the strongest predictors of the pace of white population loss and the likelihood of neighborhood racial change, exerting an influence on par with the level of minority representation in the local neighborhood itself (Denton and Massey 1991; Massey and Mullan 1984). The predictive power of these extralocal racial conditions led Denton and Massey (1991: 55) to conclude that whites are “highly cognizant” of the distribution of blacks in neighborhoods near their own and make their migration decisions accordingly.

According to these arguments, the size of the minority population in surrounding neighborhoods is an important consideration in white householders’ assessment of the relative desirability of their neighborhood. Similarly, the growth of minority populations in adjoining neighborhoods may provide residents with important clues about the future of their own neighborhood. Large or increasing minority populations in surrounding areas may be interpreted as a precursor to invasion and succession in the neighborhood of residence (Denton and Massey 1991; Molotch 1972) and may significantly influence individual decisions to remain in the neighborhood, or move out in advance of impending changes in the local area.

Following similar theoretical arguments, most prior studies of spatial dynamics anticipate and find reinforcing effects of extralocal conditions and local conditions. For example, Morenoff and Sampson (1997) find that levels of homicide in both the immediate neighborhood and surrounding neighborhoods are positively related to population loss, and Burnell (1988) finds that the minority composition of both focal and contiguous neighborhoods are inversely associated with housing values. Similarly, conditions in extralocal areas may simply spill over into the immediate neighborhood with minority concentrations in both areas exerting parallel positive influences on the likelihood of white out-migration. According to this spill-over thesis, prior studies of individual residential mobility that have focused solely on the racial characteristics of the immediate neighborhood (Crowder 2000; Harris 1997) might very well understate the extent of “white flight” from communities with large and/or increasing minority populations.

In contrast to this spillover thesis, in which the effects of racial conditions in extralocal areas are assumed to simply parallel the effects of local racial conditions, there are also reasons to anticipate opposing effects of local and extralocal characteristics on whites’ propensity to leave the neighborhood. Specifically, the concentration of minorities in extralocal neighborhoods may deter, rather than encourage, the migration of whites from the immediate, local neighborhood. What South and Crowder (1997) refer to as the housing availability model of inter-neighborhood migration posits that families’ decisions to leave their neighborhood of origin are shaped in part by the supply of neighborhoods that are perceived to be more attractive than the origin neighborhood. The racial characteristics of surrounding neighborhoods are likely to shape whites’ perceptions of the quality of potential destination options. Most residential moves occur over fairly short distances (Lee 1966; Long 1988), and individual householders are likely to consider nearby options first when weighing possible destinations. If most of these nearby options are unattractive to whites because of their large concentrations of minorities, whites may then be motivated to remain in their current neighborhood. By the same token, white residents may be particularly likely to move to a different neighborhood if they are surrounded by neighborhood options containing few minority residents because such neighborhoods are likely to be viewed as more attractive than their current neighborhood. Thus, according to this distance-dependence argument, the size and growth of minority populations in extralocal areas may actually decrease the likelihood of neighborhood out-migration among whites even while similar conditions in the immediate neighborhood propel white out-movement.

In addition to possible additive (albeit counterposing) effects of extralocal racial conditions on whites’ migration behavior, the racial characteristics of surrounding neighborhoods are likely to modify the influence of local neighborhood conditions on white migration. Specifically, living in a neighborhood with a large or growing minority population might be especially inimical to white residents if that neighborhood is surrounded by other areas in which the minority-group members make up a sizable or increasing share of residents; the combination of these local and extralocal features may send an especially strong message to white residents about the population trajectory of the broader area. In this sense, the size and growth of the minority population in the immediate neighborhood of residence might interact with, and be magnified by, similar conditions in the surrounding areas. The absence of appropriate cross-level spatially-referenced data has prevented an assessment of these interactive effects, and thus existing research might have significantly understated or overstated the overall level of “white flight” away from minority populations.

Data and Methods

Sources

In order to test the effects of extralocal neighborhood conditions on neighborhood out-migration we rely on data from the Panel Study of Income Dynamics (PSID) linked to contextual data drawn from the U.S. Census. The PSID is a well-known longitudinal survey of U.S. residents and their families begun in 1968 with approximately 5,000 families (about 18,000 individuals). Members of panel families were interviewed annually between 1968 and 1995 and every two years thereafter. New families have been added to the panel as children and other members of original panel families form their own households.

For several reasons, the PSID is uniquely suited to examining the effects of local and extralocal neighborhood conditions on migration behavior. The longitudinal nature of the PSID data makes it possible to assess prospectively the migration behavior of individual householders. In addition, the PSID contains rich information on a variety of individual- and household-level characteristics that are known to influence residential mobility decisions, thereby improving the ability to isolate the effects of neighborhood level influences on these behaviors.

Most important for the purpose of this study is the availability of restricted-access Geocode Match Files which allow us to link the individual records of individual PSID respondents to census codes describing their place of residence at each interview. These data allow us to trace the migration of PSID respondents across neighborhoods between successive interviews and to attach detailed census data about the neighborhoods occupied by these respondents at each annual interview. The PSID Geocode data also allow us to identify the conditions of the extralocal neighborhoods – those neighborhoods that are in close proximity to the tract in which each PSID resided at each annual interview. Standard GIS tools are used to determine the physical proximity of the census tract of residence to all other census tracts in the country. By attaching information on the characteristics of surrounding tracts, we are able to construct reliable measures of both local and extralocal neighborhood conditions for PSID respondents at each interview.

In this study, we follow much of the prior work in this area (e.g., Massey, Gross, and Shibuya 1994; Quillian 2002) by using census tracts to represent neighborhoods in defining local and extralocal neighborhood conditions. Although census tracts are imperfect operationalizations of neighborhoods (Tienda 1991), they undoubtedly come the closest of any commonly available spatial entity in approximating the usual conception of a neighborhood (Jargowsky 1997; White 1987). Furthermore, as of the 2000 census, census tracts were designated for the entire United States, providing the basis for characterizing neighborhoods consistently for all PSID respondents. Potential problems associated with changes in tract boundaries across decennial censuses are mitigated by our use of the Neighborhood Change Database (NCDB) constructed through a collaboration of GeoLytics Corporation and the Urban Institute (GeoLytics 2006). We use linear interpolation to estimate values for tract characteristics in non-census years.

Sample

Our sample for this analysis consists of 7,622 non-Latino white heads of PSID households who were interviewed between 1980 and 2003 and resided in a census-defined metropolitan area (MA) at the time of the interview. Because most residential moves are undertaken by families, a decision to move made by the household head (or made jointly by the family) perforce means a move by other family members. The focus only on household heads allows us to avoid counting as unique and distinct those moves made by members of the same family (e.g., children and spouses). At the same time, moves by family members who were not the household head at the beginning of the interval but become the head at the end of the interval—e.g., when a child leaves the parental home or when an ex-husband or ex-wife establishes a new residence are—included in our effective sample. We focus on PSID households residing in MA’s to take into consideration the effects of the broader geographic context on residential mobility, to remove the influence of substantial variations in the geographic scale of census tracts between metropolitan and non-metropolitan areas, and to align our results more closely with the results of studies of residential segregation.1 We focus on observations beginning in 1980 because incorporating earlier observations would require the use of 1970 census data in which racial and ethnic categories for population counts are inconsistent with categories used in later censuses.

Analytic strategy

As Anselin (2002) points out, techniques of spatial data analysis are most commonly used to model spatial autocorrelation. In these situations, a spatially lagged measure of the outcome variable of interest is included as a predictor in order to assess the degree to which the value of the dependent variable is determined by the value of the dependent variable in nearby areas (e.g., Morenoff et al. 2001; Tolnay et al. 1996). Our theoretical models point to a parallel, but somewhat less common, application of spatial regression techniques. In this analysis, the outcome of interest – out-migration from the neighborhood of origin – is hypothesized to be influenced not only by the racial composition of the population in the immediate neighborhood, but also by conditions in surrounding neighborhoods. Thus, we are interested in producing and modeling spatially lagged versions of a key set of independent variables. Such models, sometimes referred to as spatial cross-regressive models, rely on methodology that is similar to spatial autoregressive models, but are somewhat simpler to estimate without the use of specialized software (Anselin 2003).2

Consider the following extension of the basic linear regression model:

where y is the familiar n by 1 vector of observations on the dependent variable, X is an n by k matrix of observations on the contextual explanatory variables of interest, and β is the familiar k by 1 vector of regression coefficients. Less familiar are WX and γ. Here W represents a spatial weights matrix, with dimensions determined by the total number of tracts in the system, that summarizes the presumed relationship between each individual tract (row) and each of the other tracts in the system (columns). In other words, the weights that comprise the components of this matrix specify, for each tract, the presumed existence and magnitude of effects of conditions in all other tracts in the system on outcomes among those individuals originating in the tract of interest. By convention, the weights matrix is typically row standardized so that the elements of each row sum to one (Anselin 1988). Thus, WX, referred to by Anselin (1988; 2001) as a spatial lag operator, can be easily interpreted as a weighted average of values on the explanatory variable for all potentially influential extralocal tracts and γ is the k-1 by 1 vector (matching the column dimension of WX) representing the effect of these extralocal conditions on the value of the dependent variable. In the analysis of the effects of extralocal racial conditions on the risk of residential out-mobility for a given observation in tract i, the spatial lag ΣjwijXj represents the weighted average of the racial composition (e.g., percent minority) in all extralocal tracts. A key advantage of this approach is that it specifies separate effects of local and extralocal conditions; the spatial lag operator is treated as a separate contextual characteristic with possible additive and interactive effects on the outcomes of interest.

The spatial weights matrix is essential for specifying which tracts are to be considered most important in defining extralocal neighborhood conditions and, therefore, the presumed dependence of events that occur to the individuals in a given tract on the conditions in other tracts in the system. Following Downey’s (2006: 570) argument that spatial dependence tends to decline with distance, we employ a spatial-weighting strategy in which the influence of conditions in an extralocal area on individual mobility decisions is assumed to be inversely related to the distance of the extralocal tract from the individual’s tract of residence. Specifically, under this distance-decay strategy the elements of the spatial weights matrix are defined as wij = 1/dij where dij is the geographic distance between the centroid of the tract of residence (i) and the centroid of the extralocal tract, j. Given the implausibility that the demographic characteristics of every tract in the nation directly affect the decisions of residents of all other tracts, we constrain to zero the influence of tracts that are more than 100 miles away from the focal tract.3

Under this strategy, nearby neighborhoods are weighted most heavily in creating extralocal measures (e.g., the spatial weight linking a tract that is ten miles from the tract of residence is one-tenth as large as the weight characterizing a tract that is one mile away) and, therefore, assumed to be most important in shaping mobility decisions. This is consistent with theoretical models of neighborhood change (e.g., Park et al. 1925) that imply that processes of invasion and succession originate from adjacent neighborhoods in such a way that conditions in nearby tracts would provide the most important cues about the potential for the influx of minority populations. More generally, this weighting reflects the assumption that nearby areas are most influential in individual assessments of the broader racial-residential context in which the neighborhood of residence is situated. By extension, to the extent that these perceptions of broader racial conditions shape levels of neighborhood satisfaction and definitions of place utility (Wolpert 1966), these conditions in the most proximate neighborhoods are likely to have the strongest effect on decisions to leave the area. Finally, the greater weight applied to geographically proximate neighborhoods is consistent with observations that mobility is highly distance dependent (Lee 1966) such that neighborhoods within the closest proximity to the tract of residence are the most likely destinations for movers. Accordingly, racial conditions in these nearby areas are likely to be most important in defining the relative attractiveness of alternative residential options.

While sharing an emphasis on nearby tracts, the distance-decay function holds important theoretical and practical advantages over a simpler adjacency approach in which all tracts that do not share a border with the tract of residence are presumed to be inconsequential for mobility decisions. Most notably, the distance decay function produces measures of extralocal context based on (distance weighted) conditions in a larger set of surrounding areas, including those tracts that are not directly adjacent but still in close proximity to the tract of residence, and those areas visited or traveled through by the individual in the course of her/his daily activities. This is in line with the theoretical argument that householders take into consideration conditions in a broader range of geographic areas in weighing their residential options, an assumption supported by recent research suggesting that white householders are well aware of the racial composition of neighborhoods across the metropolitan area and adjust their residential search strategies accordingly (Krysan 2002b, 2007). In addition, the distance-decay approach does not require the adoption of necessarily arbitrary criteria for assigning adjacency (Anselin 2002) and avoids the definition of presumably influential extralocal areas that vary dramatically in geographic size depending on the size of the tracts in and around the individual’s area of residence (Downey 2006).4

Despite these advantages, the distance-decay approach likely produces only rough estimates of the extralocal conditions that may influence individual mobility decisions. Notably, due to the limited geographic precision of the PSID geocode data, our measures of extralocal and local context rely on fairly large geographic units and do not account for the precise location of the individual household within the census tract, limitations that can have profound implications for the ability to construct meaningful contextual variables (Downey 2006). Furthermore, our spatial weights do not incorporate information about many factors that may affect residents’ actual exposure to conditions in different neighborhoods, including connections via residential streets (Grannis 1998), the existence of natural and manmade barriers, and actual travel times between tracts. The geographic dispersion of our sample limits our ability to consider these types of factors so that our measures of extralocal conditions likely include information about some tracts that are relatively unimportant to individual mobility decisions while deemphasizing conditions in some more important areas. To the extent that these sources of imprecision introduce (presumably random) measurement error into our measures of extralocal context, our results should be considered conservative estimates of the effects of these extralocal conditions on individual mobility behavior.

In comparison to more typical autoregressive forms of spatial data analysis, the general cross-regressive strategy requires few modifications to standard estimation procedures (Anselin 2002) and is sufficiently flexible to accommodate a variety of methodological techniques. We take full advantage of this flexibility, the longitudinal nature of the PSID data, and the fact that tract-coded residential addresses are available for PSID respondents at each interview by segmenting each respondent’s data record into a series of person-period observations, with each observation referring to two-year period between PSID interviews. Although it is possible to define annual mobility intervals for most years of the PSID, the use of a two-year interval is necessitated by the adoption of a biennial interview schedule in the PSID after 1995.5 On average, the individuals in the sample contribute just under 6.4 person-period observations for a total sample size of 48,508 person-period observations. We use logistic regression to examine the additive and interactive effects of local and extralocal neighborhood conditions and individual-level characteristics on the odds of moving to a different census tract between interviews. Because the same PSID respondent can contribute more than one person-period to the analysis, and because inter-neighborhood migration is a repeatable event, the usual assumption of the stochastic independence of error terms underlying tests of statistical significance is violated (McClendon 2002). We correct for this non-independence of observations using the cluster procedure6 available in Stata to compute robust standard errors (StataCorp 2005).7

Dependent variable

The dependent variable is a dichotomous variable indicating whether the respondent moved out of the census tract of origin between PSID interviews, taking a value of 1 for those who moved during the migration interval and a value of 0 for those who remained in the same tract.

Explanatory variables

Our primary explanatory variables refer to the racial and ethnic composition of the population in and around the tract of residence at the beginning of the migration interval. Following past research (Crowder 2000; Denton and Massey 1991) we focus on three dimensions of the racial/ethnic composition of the tract of origin. The overall local minority concentration is measured by the percentage of the population in the tract of residence that is not non-Latino white (i.e., the percent non-anglo)8. The local multiethnic indicator is a simple dichotomous variable that takes a value of 1 if three groups – Latinos, non-Latino blacks, and non-Latino members of other non-white groups – each represent at least 10% of the total minority population in the neighborhood. Change in the local minority concentration in the local neighborhood is measured as the absolute difference between the percent minority in the year of observation and the percent minority in the tract as of five years prior to the observation year. We use linear interpolation, with endpoints defined by the most recent preceding census year and the nearest subsequent census, to estimate the racial/ethnic composition of census tracts in non-census years.

A parallel set of variables are used to characterize the racial/ethnic composition of the population in extralocal neighborhoods – those areas surrounding the neighborhood of residence. As noted above, with row standardization of the spatial weights matrix, the racial/ethnic composition of extralocal neighbors refers to the distance-weighted average characteristics in surrounding tracts. We use these spatially weighted data as the basis for three separate variables related to extralocal racial conditions: the overall minority concentration; an extralocal multiethnic indicator9; and the change in the extralocal minority concentration during the five years prior to the observation year.

In order to better isolate the influence of racial conditions in and around the tract of residence, we control for a number of other potential individual-, family-, and tract-level determinants of geographic mobility. Key demographic predictors of residential mobility include age and, to capture the non-monotonic dependence of migration on age (Long 1988), age-squared. The sex of the householder is captured as a dummy variable scored 1 for females and marital status takes a value of 1 for respondents who were married or permanently cohabiting. The effect of children is tapped with a variable indicating the total number of people under age 18 in the family. We also control for the education of the householder, measured by years of school completed, and the total family taxable income, measured in thousands of constant 2000 dollars. Home ownership is coded as 1 for those in an owner-occupied housing unit, household crowding is measured by the number of persons per room, and length of residence takes a value of 1 for those respondents who had lived in their home for at least three years. All of these variables except sex are considered time-varying and refer to conditions at the beginning of the mobility interval. The year of observation is included in all models to account for trends in inter-neighborhood migration.

To further isolate white respondents’ responsiveness to area racial characteristics, we also control for several other tract-level characteristics that may be correlated with both the racial composition of the population and the likelihood of moving. To account for the possibility that white residents are more responsive to socioeconomic characteristics than to the racial composition of the neighborhood, we control for the poverty level – the percentage of the population in families with incomes below the federal poverty line – in the tract of residence. We also control for the local level of home ownership – the percentage of households in the tract of residence that are owner occupied – a factor that may influence mobility decisions by affecting the social and economic stability of the neighborhood. Finally, we control for the local concentration of single-mother families, which refers to the percentage of families with children in the neighborhood that are headed by single women. Although these variables do not represent an exhaustive list, they are likely correlated with a number of other contextual factors (e.g., economic conditions, social cohesion, crime, and structural deterioration) that may influence migration decisions (Crowder 2000).

Results

Table 1 provides means, standard deviations, and descriptions of the measurement strategies for all variables employed in the analysis. The table shows that about 27% of white householders moved to a different tract during the typical two-year observation period. The average respondent was just over 43 years of age, had completed just over 13 years of education, and had a family income of about $54,700 (adjusted to 2000 dollars) at the beginning of the typical interval. Over 80% of the householders were employed for pay at the beginning of the migration interval. About one-fourth of the householders in the sample are women and the households contained an average of just below one child. At the beginning of the typical mobility interval, about 65% of the householders owned their own home, 38% had lived in their home for at least three years, and, on average, the households represented in the sample had a ratio of members to rooms of just under one-half.

Table 1.

Descriptive Statistics for Variables in Models of Residential Mobility between Census Tracts: White PSID Householders, 1980–2003.

| Variable | Definition | Mean | S.D. |

|---|---|---|---|

| Dependent Variable | |||

| Moved out of the census tract | Whether R changed census tracts from time t to t+2 (1=yes) | .267 | .442 |

| Independent Variables | |||

| Extralocal Neighborhood Conditions | |||

| Minority concentration in distance-weighted surrounding neighborhoods | Distance-weighted average percent non-anglo in tracts within 100 miles of R’s tract of residence at time t. | 26.692 | 14.865 |

| Multiethnic indicator for distance-weighted surrounding neighborhoods | Whether distance-weighted average non-anglo population in tracts within 100 miles of R’s tract of residence at time t contains at least 10% black, 10% Latino, and 10% other races (1=yes) | .520 | .500 |

| Change in minority concentration in distance- weighted surrounding neighborhoods | Difference between times t and t-5 in distance-weighted average percent non-anglo in tracts within 100 miles of R’s tract of residence at time t. | 2.935 | 1.632 |

| Local Neighborhood Conditions | |||

| Minority concentration in neighborhood | Percent non-white in R’s tract of residence at time t | 18.285 | 22.249 |

| Multiethnic indicator for neighborhood | Whether non-white population R’s tract of residence at time t contains at least 10% black, 10% Latino, and 10% other races (1=yes) | .459 | .498 |

| Change in minority concentration in neighborhood | Difference between times t and t-5 in percent non-white in R’s tract of residence at time t. | 3.023 | 4.561 |

| Poverty level in neighborhood | Percent of population in R’s tract of residence at time t living in families with incomes below poverty line | 9.512 | 8.695 |

| Level of home ownership in neighborhood | Percent of housing units in R’s tract of residence at time t occupied by the homeowner | 66.635 | 21.320 |

| Level of single-motherhood in neighborhood | Percent of families with children in R’s tract of residence at time t headed by a single woman | 19.521 | 10.960 |

| Micro-level characteristics | |||

| Age | Age of R in years at time t | 43.280 | 16.450 |

| Female | Whether R is female (1=yes) | .249 | .432 |

| Education | Total years of school complete by R by time t | 13.206 | 2.970 |

| Family Income (in $1000’s) | Total taxable income of household head and spouse at time t, in thousands of constant 2000 dollars | 54.764 | 66.954 |

| Employed | Whether R is working for pay at time t (1=yes) | .833 | .373 |

| Married | Whether R has spouse or long-term cohabitor present at time t (1=yes) | .642 | .480 |

| Children | Number of children in household at time t | .810 | 1.107 |

| Homeowner | Whether R is living in owner-occupied housing unit at time t (1=yes) | .653 | .476 |

| Household crowding | Number of persons per room in housing unit at time t | .478 | .256 |

| Long-term resident | Whether R had lived in house for 3 or more years at time t (1=yes) | .384 | .486 |

| Year | Year of interview, time t | 1989.436 | 5.946 |

| N of person-period observations | 48,508 | ||

| N of persons | 7,622 | ||

More important for the purpose of this study are the contextual conditions in and around the neighborhood of residence for these householders. Focusing first on the conditions of the local neighborhood, the statistics highlight the fact that the average householder originated in a predominantly white non-Latino neighborhood; at the beginning of the average mobility interval the tracts in which these householders resided contained populations in which only about 18% of the residents were non-anglo, and these minority concentrations had grown by an average of about 3 percentage points in the five years preceding the mobility interval. The mean for the local multiethnic indicator indicates that in about 46% of the neighborhoods occupied by the householders in the sample, Latino, black, and other-race residents each made up at least 10% of the total minority population. In terms of the nonracial contextual conditions that may be associated with neighborhood out-migration, the poverty rate in the tract at the beginning of the typical observation period was just under 10%, about 66% of the residents in the average tract owned their own home, and about 20% of the families with children in these areas were headed by single mothers.

The statistics for extralocal conditions in Table 1 indicate that the percent minority in tracts surrounding the respondents’ immediate neighborhood had a spatially-weighted average of just under 27% non-white minorities. In about 52% of the observation periods, the householder lived in a neighborhood in which the average population in surrounding neighborhoods could be considered multiethnic, with the minority population made up of at least 10% of each of the three main non-white groups. The minority percentage increased by an average of about 3 percentage points in these extralocal areas in the five years preceding the mobility interval. The similarity in the means for local and extralocal racial conditions is consistent with fairly high correlations between these sets of measures. For example, the bivariate correlation between the minority concentration in the immediate neighborhood and that in surrounding tracts is .59, clearly reflecting high levels of residential segregation by race in most metropolitan areas. However, the fact that this correlation is not higher also points to considerable dissimilarity between local and extralocal conditions faced by many white householders, highlighting the potential for independent effects of these local and extralocal conditions on individual migration behavior.

Table 2 presents results of logistic regression models that explore the additive effects of extralocal neighborhood population conditions on white householders’ decisions to leave their neighborhoods. The first model is a baseline model that focuses just on the effects of racial conditions in the immediate neighborhood of residence along with a set of tract- and individual-level control variables used to isolate the influence of local racial conditions. The results of this first model are consistent with the hypothesis that white householders’ likelihood of moving from their neighborhood is influenced by the concentration of minorities in the area. However, consistent with results from research utilizing data from a more limited time period (Crowder 2000) and at least one study of aggregate neighborhood change (Galster 1990), this effect is non-linear. Specifically, the combination of the positive coefficient for the linear term (b=.0159) with the small but significant coefficients for the squared and cubed versions of the variable (b=−.0003 and b=.000002, respectively) indicates that the odds of out-migration increase as the concentration of minority residents increases from 0% up to about 35% minority, where the effect softens in the middle of the distribution before becoming more pronounced after the minority concentration surpasses about 60%. Also consistent with earlier research (Crowder 2000; Denton and Massey 1991), the presence of multiethnic minority populations is a significant mobility motivator for white householders; the odds of moving from the tract of origin are over 9% higher [(e.0884 − 1)*100=9.243] for those whites living in neighborhoods with multi-ethnic minority populations than for those in areas with more homogeneous minority populations. Finally, independent of the overall size and specific composition of the minority population in the neighborhood, recent changes in the size of the minority population increase the odds of exit for white householders. This result is consistent with the idea that white householders view growing minority concentrations as an indication of an undesirable future trajectory for the neighborhood with some householders opting to move out in advance of these changes.10

Table 2.

Logistic Coefficients for Regression Analyses of Residential Mobility Out of Census Tract of Origin: White PSID Householders, 1980–2003.

| Model 1 |

Model 2 |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Independent Variables | b | se | b | se |

| Extralocal Neighborhood Conditions | ||||

| Minority concentration in distance- weighted surrounding neighborhoods | −.0092 *** | .0021 | ||

| Multiethnic indicator for distance- weighted surrounding neighborhoods | −.0971 ** | .0350 | ||

| Change in minority concentration in distance- weighted surrounding neighborhoods | .0445 ** | .0163 | ||

| Local Neighborhood Conditions | ||||

| Minority concentration | .0159 ** | .0053 | .0231 *** | .0059 |

| Squared minority concentration | −.0003 * | .0001 | −.0004 ** | .0002 |

| Cubed minority concentrationa | .0002 * | .0001 | .0002 * | .0001 |

| Multiethnic indicator | .0884 ** | .0332 | .0848 * | .0335 |

| Change in minority concentration | .0075 * | .0038 | .0019 | .0049 |

| Poverty level | −.0056 | .0032 | −.0067 * | .0033 |

| Level of homeownership | −.0030 ** | .0011 | −.0037 *** | .0011 |

| Level of single-motherhood | .0010 | .0023 | −.0010 | .0023 |

| Micro-level Characteristics | ||||

| Age | −.1347 *** | .0062 | −.1351 *** | .0063 |

| Age-squared | .0010 *** | .0001 | .0010 *** | .0001 |

| Female | .0634 | .0506 | .0549 | .0506 |

| Education | .0310 *** | .0067 | .0323 *** | .0068 |

| Family Income (in $1000’s) | .0007 *** | .0002 | .0009 *** | .0002 |

| Employed | −.0486 | .0616 | −.0545 | .0618 |

| Married | −.2298 *** | .0442 | −.2370 *** | .0442 |

| Children | −.1055 *** | .0161 | −.1069 *** | .0161 |

| Homeowner | −1.0504 *** | .0380 | −1.0622 *** | .0381 |

| Household crowding | .0357 *** | .0071 | .0347 *** | .0071 |

| Long-term resident | −.2442 *** | .0384 | −.2357 *** | .0383 |

| Year | .0419 *** | .0033 | .0427 *** | .0034 |

| Constant | −80.367 *** | 6.695 | −81.687 *** | 6.810 |

| Wald chi-square | 4228.38 | 4290.20 | ||

p<.05;

p<.01;

p<.001

Coefficients and standard errors multiplied by 100

N of observations = 48,508; N of persons = 7,622

Importantly, these effects of local racial conditions hold even controlling for a wide range of individual-level characteristics and non-racial tract conditions, most of which have effects on neighborhood out-migration that are consistent with existing theory and prior research. The concentration of homeowners in the neighborhood negatively affects the likelihood of out-migration, presumably by affecting the stability and structural quality of the neighborhood. The likelihood of moving decreases significantly with age but this decline tapers off at older ages. Educational attainment and family income are both significantly and positively associated with the likelihood of moving out of the origin tract. Married respondents are less likely than the unmarried to change tracts, and the number of children in the household is inversely associated with inter-tract migration. The likelihood of moving to a different tract increases significantly with household crowding and is significantly lower for those who own their home and for longer-term residents.

While the results in Model 1 show that the migration behavior of individual white respondents is influenced significantly by the relative size and composition of minority populations in their neighborhood of residence, our central goal is to assess whether these effects of the local racial context extend beyond the borders of their immediate neighborhoods to surrounding areas. To this end, Model 2 of Table 2 adds the series of variables describing the racial conditions of extralocal areas. The results of this model indicate that all three dimensions of the extralocal racial context exert an independent influence on white out-migration. The negative coefficient associated with the minority concentration in adjacent neighborhoods indicates that, controlling for conditions in the immediate neighborhood and other predictors of mobility, the likelihood of out-migrating is lower for white householders living in areas in which surrounding neighborhoods have relatively large minority populations than for those living in areas surrounded by whiter neighborhoods. 11 To illustrate, a 10-point increase in the distance-weighted average minority percentage in extralocal areas is predicted to decrease the odds of neighborhood out-migration by almost 9% [(e−.0092×10−1)*100 = −8.789] Similarly, the significant negative coefficient associated with the indicator of the multiethnic populations indicates that, even controlling for the relative size of the minority population in surrounding tracts, a sizable representation of all three major non-white groups within this population decreases the odds of out-migration for white householders by just over 9% [(e−.0971−1)*100=−9.075].

These negative effects of the relative size and composition of the minority population in surrounding areas are consistent with arguments based on the distance-dependence of migration: Because most geographic moves take place over a relatively short distance12, unfavorable conditions in nearby areas will tend to reduce the likelihood of out-migration by convincing householders that the available alternative neighborhoods to which they might move are relatively unattractive.

It is also worth noting that controlling for these negative effects of the size and composition of the minority population in the extralocal areas substantially enhances the influence of local racial conditions. Specifically, the positive linear coefficient for local minority concentration increases by about 45%, from .0159 in Model 1 to .0231 in Model 2, when these extralocal conditions are introduced. This suppression stems from the fairly strong positive association between local and extralocal neighborhood characteristics, with neighborhoods of similar racial characteristics clustering together, but countervailing influences of these forces on whites’ out-migration. Consequently, controlling for the negative impact of minority concentration in surrounding neighborhoods on whites’ out-migration reveals a stronger positive effect of local minority concentrations on white’s propensity to move out of their neighborhood.13

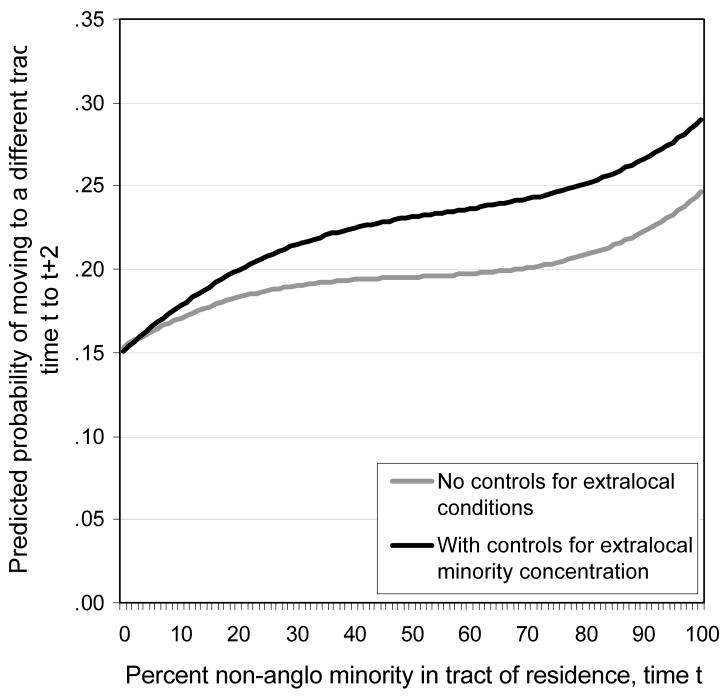

Figure 1 illustrates this suppression by graphing the effect of local minority concentration on the probability that whites will move from their census tract, with and without controls for the level of minority concentration in extralocal areas.14 The difference between the two lines in this figure is most acute at lower levels of local minority concentration— the very types of neighborhoods in which most whites reside. For example, without controlling for extralocal minority concentration, the predicted probability that whites will leave their neighborhood over the subsequent two-year period increases from .15 to about .19 as the percent minority in the immediate neighborhood increases from 0% to 30%. This is a nontrivial but not overwhelming difference. However, when the concentration of minorities in extralocal neighborhood is controlled, the predicted probability of out-migration increases from .15 in local neighborhoods with no minorities to about .22 in neighborhood that are 30% minority. Thus, the observed influence of local minority concentration on white neighborhood out-migration— and hence support for the core claim of the white flight thesis— is enhanced considerably when the impact of racial conditions in surrounding neighborhoods is taken into account.

Figure 1.

Predicted Probability of Migration Out of Census Tract of Origin by Local Minority Concentration

In contrast to the mobility-deterring effects of extralocal minority concentrations and multiethnic structures, recent growth of the minority population in these surrounding areas appears to encourage white out-migration.15 The positive coefficient in Model 2 indicates that the odds of leaving the tract of origin increase by about 4.6% for each one percentage-point increase in the distance-weighted average minority concentration in surrounding areas during the five years leading up to the mobility interval [(e.0445−1)*100=4.550]. Furthermore, when this significant influence of changes in the extralocal racial concentrations is controlled, the coefficient associated with changes in the minority composition of the immediate neighborhood of residence is reduced to less than a third of its original size (from .0075 in Model 1 to .0019 in Model 3) and the coefficient is driven to statistical non-significance. Thus, changes in the minority population in surrounding areas appear to be more important in prompting white out-migration than are recent changes in the racial composition of the immediate neighborhood. This finding is consistent with theoretical arguments suggesting that changes in surrounding areas may provide the strongest clues about the future trajectory of their area so that, controlling for the size and specific composition of the local population, growing minority populations in these surrounding neighborhoods are an especially powerful impetus to move for white householders. By failing to consider the impact of extralocal racial conditions and change, past studies aimed at describing patterns of white flight (e.g., Crowder 2000; Ellen 2000) apparently not only underestimated the effects of static population concentrations on white out-migration, but may have overstated the importance of changes in local racial conditions.

Supplemental test of the distance-dependence argument

As noted above, the results in Table 2 support the argument that high concentrations of minorities and multiethnic population structures in surrounding neighborhoods deter white out-mobility by reducing the relative attractiveness of the most likely mobility destinations. Following the basic logic of this distance-dependence thesis, it is reasonable to expect that white householders would avoid unattractive extralocal areas not only by remaining in their current neighborhood, but by choosing destinations farther away when they do decide to move. Thus, in order to further test the distance-dependence argument, Table 3 provides a supplemental analysis of the distance moved, in miles, by those white householders who changed tracts between interviews. These distances were calculated by applying the Haversine equation (Sinnott 1984) to the latitude and longitude coordinates for the centroids of the tracts of origin and destination. We apply Ordinary Least Squares regression to predict these distances as a function of extralocal neighborhood conditions while controlling for the racial conditions of the immediate neighborhood of residence and micro-level factors that affect mobility decisions.

Table 3.

Ordinary Least Squares Regression Analysis of Distance in Miles between Tracts of Origin and Destination: Mobile White PSID Householders, 1980–2003.

| Independent Variables | b | se |

|---|---|---|

| Extralocal Neighborhood Conditions | ||

| Minority concentration in distance- weighted surrounding neighborhoods | 1.0691 * | .4633 |

| Multiethnic indicator for distance- weighted surrounding neighborhoods | 21.6281 ** | 8.0017 |

| Change in minority concentration in distance- weighted surrounding neighborhoods | .5004 | 3.7016 |

| Local Neighborhood Conditions | ||

| Minority concentration | 3.3355 ** | 1.2712 |

| Squared minority concentration | −.0461 | .0351 |

| Cubed minority concentrationa | .0040 | .0267 |

| Multiethnic indicator | 13.2241 | 7.8416 |

| Change in minority concentration | −3.795 | 2.1420 |

| Micro-level Characteristics | ||

| Age | −2.1787 | 1.4001 |

| Age-squared | .0293 | .0154 |

| Female | −9.4519 | 9.3750 |

| Education | 16.7378 *** | 1.4809 |

| Family Income (in $1000’s) | .0010 | .0737 |

| Employed | −39.7071 ** | 15.0570 |

| Married | 32.7062 *** | 9.3084 |

| Children | −1.9736 | 4.0790 |

| Homeowner | 25.6266 ** | 9.0579 |

| Household crowding | −1.6489 * | 1.8695 |

| Long-term resident | −37.7173 *** | 9.8580 |

| Year (1980=0) | −3.7113 *** | .8576 |

| Constant | −28.9374 | 34.1047 |

| R-square | .0240 | |

p<.05;

p<.01;

p<.001

Coefficients and standard errors multiplied by 100

N of observations = 12,934; N of persons = 4,686

The results of this supplemental analysis confirm that the distance moved by mobile white householders is significantly influenced by a wide range of micro-level factors including education, housing status, and family composition. Most importantly, even after controlling for these significant predictors, the coefficients for both the extralocal minority concentrations and the extralocal multiethnic indicator are positive and statistically significant. Thus, consistent with the distance-dependence function, these results indicate that when they do choose to move, those whites moving away from tracts surrounded by relatively large and diverse concentrations of minorities tend to bypass these geographically nearby neighborhoods – areas that are usually the most common destinations for residential movers – in favor of neighborhoods farther away.

The moderating effects of extralocal conditions on white migration

Having presented evidence that racial conditions in surrounding neighborhoods significantly affect white householders’ likelihood of moving from their neighborhood, we now examine the extent to which these extralocal racial conditions alter whites’ reactions to the conditions in their own neighborhood. Table 4 reports partial results from logistic regression models predicting the log-odds of neighborhood out-migration that test for these interactive effects. These models include a series of product terms involving specific indicators of local racial conditions and specific indicators of extralocal racial conditions.

Table 4.

Coefficients for Interactions between Local and Extralocal Conditions from Logistic Regression Analyses of Residential Mobility Out of Census Tract of Origin: White PSID Householders, 1980–2003.

| Model 1 |

Model 2 |

Model 3 |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| b | se | b | se | b | se | |

| Extralocal Neighborhood Conditions | ||||||

| Minority concentration in distance- weighted surrounding neighborhoods | −.0135 *** | .0029 | −.0066 * | .0026 | −.0106 *** | .0025 |

| Multiethnic indicator for distance- weighted surrounding neighborhoods | −.1637 *** | .0456 | −.0407 | .0459 | −.1317 ** | .0437 |

| Change in minority concentration in distance- weighted surrounding neighborhoods | .0592 ** | .0231 | .0244 | .0206 | .0636 *** | .0197 |

| Local Neighborhood Conditions | ||||||

| Minority concentration | .0204 ** | .0068 | .0235 *** | .0059 | .0220 *** | .0064 |

| Squared minority concentration | −.0005 * | .0003 | −.0004 ** | .0002 | −.0004 * | .0002 |

| Cubed minority concentrationa | .0003 | .0002 | .0002 * | .0001 | .0002 * | .0001 |

| Multiethnic indicator | .0793 * | .0340 | .1745 * | .0790 | .0823 * | .0336 |

| Change in minority concentration | .0005 | .0050 | .0019 | .0049 | .0041 | .0125 |

| Local-Extralocal Interactions | ||||||

| Local minority concentration | ||||||

| by Extralocal minority concentration | .0002 * | .0001 | ||||

| by Extralocal multiethnic indicator | .0030 * | .0015 | ||||

| by Extralocal change in minority conc. | −.0004 | .0006 | ||||

| Squared local minority concentration | ||||||

| by Extralocal minority concentration | −.0000 | .0000 | ||||

| by Extralocal multiethnic indicator | .0000 | .0000 | ||||

| by Extralocal change in minority conc. | .0001 | .0001 | ||||

| Cubed local minority concentration | ||||||

| by Extralocal minority concentration | −.0000 | .0000 | ||||

| by Extralocal multiethnic indicator | −.0000 | .0000 | ||||

| by Extralocal change in minority conc. | −.0000 | .0000 | ||||

| Local multiethnic indicator | ||||||

| by Extralocal minority concentration | −.0061 | .0035 | ||||

| by Extralocal multiethnic indicator | −.1240 * | .0617 | ||||

| by Extralocal change in minority conc. | .0460 | .0302 | ||||

| Local change in minority concentration | ||||||

| by Extralocal minority concentration | .0003 | .0003 | ||||

| by Extralocal multiethnic indicator | .0087 | .0072 | ||||

| by Extralocal change in minority conc. | −.0040 | .0024 | ||||

Note: All coefficients based on models containing all micro-level and tract characteristics controlled in Table 2.

p<.05;

p<.01;

p<.001

Coefficients and standard errors multiplied by 100

N of observations = 48,508; N of persons = 7,622

In Model 1 of Table 4, we include product terms representing the interaction between the percent minority in the local neighborhood of residence and its polynomials with the three measures of extralocal conditions – the minority concentration, multiethnic indicator, and recent changes in minority concentration. Although few of the coefficients for the product terms are statistically significant, the results highlight some important ways that local and extralocal conditions interact to affect mobility behavior. The positive coefficient for the interaction between the measures of local and extralocal minority concentrations suggests that high concentrations of minority residents in surrounding neighborhoods tend to increase the generally positive influence of local minority concentrations on white out-mobility. In other words, the combination of high concentrations of minorities in the immediate neighborhood of residence with high concentrations in surrounding areas appears to be especially inimical to white householders.

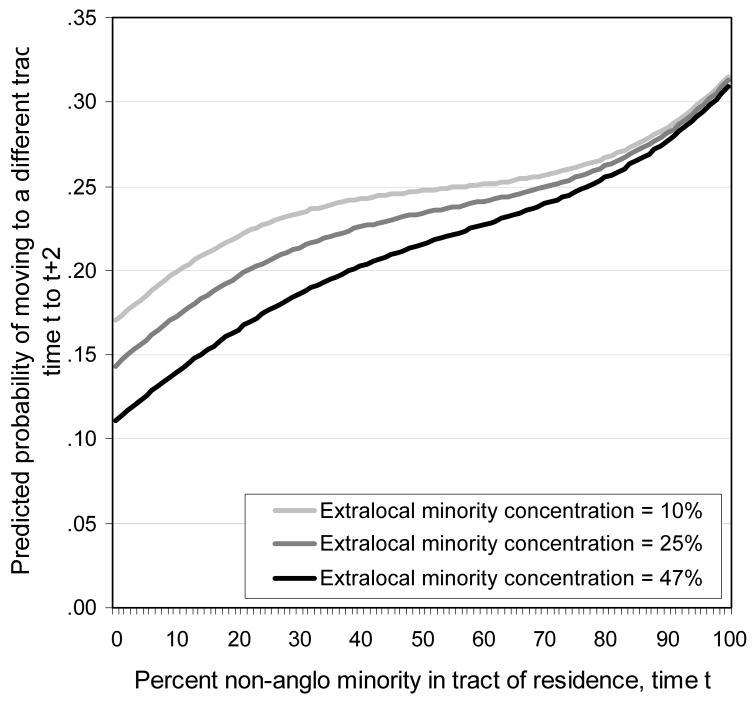

Figure 2 illustrates how the concentration of minorities in extralocal areas modifies the impact of local minority concentration on white neighborhood out-migration. The three lines in the figure represent the estimated probability of out-migration across the values of local minority concentrations when minority percentages in surrounding areas are at the 10th percentile (top line in the figure), median (middle line), and 90th percentile (bottom line), with values for all other variables set at their means.

Figure 2.

Predicted Probability of Migration Out of Census Tract of Origin by Local Minority Concentration and Extralocal Minority Concentration

The differences in intercepts for the three lines in Figure 2 reflect the generally negative effect of extralocal minority concentrations on the likelihood of out-migration. More important is the difference in slopes between these lines, a function of the interaction between local and extralocal minority concentrations in Model 1 of Table 4. When the spatially-weighted average extralocal population contains only 10% minority residents, the likelihood of leaving the neighborhood rises moderately with the level of minority concentration in the immediate neighborhood of residence. But as the concentration of minority residents in surrounding areas increases, the association between local minority concentrations and out-migration becomes more pronounced. For example, when the minority concentration in surrounding areas is at about 47% (the 90th percentile), the predicted probability of leaving the neighborhood is about .11 for a white householder in a neighborhood with no minority neighbors. Under such extralocal conditions, this probability of out-migration doubles to about .22 for those in neighborhoods in which 50% of the residents are non-white. Moreover, the nonlinearity of the association between local minority concentrations and out-migration is less pronounced when surrounding tracts contain higher shares of minorities.

As also shown in Model 1 of Table 4, the generally positive influence of local minority concentrations appears to be enhanced by the presence of diverse minority populations in surrounding neighborhoods, as indicated by the significant positive coefficient for the interaction involving the extralocal multiethnic indicator. Thus, not only does the correlation between local and extralocal neighborhood conditions tend to suppress the apparent additive effects of extralocal population characteristics, higher concentrations of minorities in surrounding areas and the presence of multiethnic minority populations also appear to increase whites’ sensitivity to the size of the minority population in their own neighborhood. Or, turning this interpretation around, the positive interaction coefficients in Model 1 indicate that while large concentrations of minority residents and multiethnic minority populations in surrounding areas tend to inhibit white out-migration by reducing the pool of attractive potential destinations, these effects are weaker when the local neighborhood contains similarly unattractive concentrations of minority residents.

Models 2 and 3 present selected coefficients from models that include interactions of the three measures of extralocal racial conditions with the local multiethnic indicator and changes in the local minority composition, respectively. Only one coefficient for these interaction terms attains statistical significance. The negative interaction between the local and extralocal multiethnic indicators (Model 2) suggests that the generally positive effect on white out-migration of exposure to a diverse minority population in the immediate neighborhood is somewhat weaker when the minority population in surrounding areas also contains sizable shares of all three minority groups. In such situations, white householders may be less likely to leave multiethnic neighborhoods because surrounding areas fail to provide more attractive residential options. Like the significant interactions involving local and extralocal minority concentrations, this interaction suggests that understanding how the racial-residential context affects whites’ mobility decisions requires attention to conditions within the neighborhood of residence relative to those in surrounding areas.

Discussion and Conclusion

A growing number of studies have sought to understand the individual migration patterns that shape patterns of segregation by race, ethnicity, and economic status. While these studies have provided important clues about the processes through which broader population distributions are developed and maintained, most of this research has focused on the effects of individual-level characteristics and, in a few studies, the conditions of the immediate neighborhood of residence. These studies have ignored how individual migration behaviors are shaped by conditions in extralocal areas – the broader set of neighborhoods surrounding the place of residence – despite compelling practical and theoretical arguments that these broader contextual conditions help to shape individual’s residential satisfaction and interact in important ways with local conditions to affect individuals’ assessment of their residential options.

Like other recent studies of spatial dynamics (e.g., Morenoff 2003; Sampson et al. 1999), our approach explicitly acknowledges that neighborhoods are embedded in a larger mosaic of urban communities, and demonstrates that the behaviors of individuals in a given neighborhood are influenced by conditions in nearby neighborhoods. Specifically, growing concentrations of non-white minority residents in nearby tracts significantly increase the likelihood that whites will leave their neighborhood of residence. In fact, all else equal, changes in extralocal minority populations appear to exert a stronger influence on whites’ migration behavior than do changes in the size of the minority population in the immediate neighborhood. In contrast, controlling for local neighborhood conditions and changes in surrounding areas, large and diverse minority populations in extralocal neighborhoods tend to reduce the likelihood that white residents will leave their neighborhood.

These disparate effects of extralocal racial conditions on neighborhood out-migration likely reflect the fact that the various features of surrounding neighborhoods influence different aspects of the mobility decision-making process. Following Wolpert’s (1966) classic place-utility model and Speare’s residential satisfaction perspective (Speare 1974), recent racial changes in surrounding neighborhoods are especially likely to influence the desire to leave the neighborhood of residence by creating a disparity between residential preferences (which likely influenced the decision to settle in the neighborhood of residence) and actual neighborhood contextual conditions. These changes are also likely to signal the trajectory of the neighborhood characteristics and provide clues about the future rift between residential preferences and neighborhood conditions, prompting at least some white householders to consider a move. However, once this decision to consider leaving the neighborhood of residence is made, the size and diversity of the minority population in surrounding areas is likely to be important in determining the relative attractiveness of alternative locations. In the context of white aversion to residing near large and diverse concentrations of non-whites and the fact that nearby neighborhoods tend to be the most likely residential destinations, a large concentration of minorities in these surrounding areas may dissuade the householder from actually undertaking a residential move because these residential alternatives are relatively unattractive, an argument supported by the negative net effects of extralocal minority concentrations and multiethnic conditions on the likelihood of out-migration among whites.

Perhaps most importantly, controlling for countervailing effects of conditions in extralocal areas reveals substantially stronger support for the most essential element of the white flight thesis —that whites leave neighborhoods containing large minority populations —than has previously been observed. Some observers have dismissed the claim that white flight plays an important role in shaping broader population patterns largely on the grounds of fairly weak effects of neighborhood racial composition on white out-migration (Ellen 2000; Taub, Taylor, and Dunham 1984). But by failing to consider the countervailing effects of racial conditions in local and extralocal neighborhoods, prior tests of the white flight thesis may have substantially underestimated the causal impact of neighborhood racial composition on white out-migration. Our results suggest that white flight in its most basic form remains a defining feature of the American urban landscape.

While additional attention to the residential choices of non-white groups and to the destinations of movers is still needed, the effects of extralocal conditions on white mobility decisions have important implications for understanding the dynamics of neighborhood change and the processes that sustain high levels of racial residential segregation in American cities. High levels of white migration from neighborhoods that contain large minority populations, in conjunction with whites’ tendency to relocate to neighborhoods that are “whiter” than their origin neighborhoods (South and Crowder 1998), reinforce existing levels of segregation. This “white flight” likely helps to explain that part of racial segregation resulting from different races occupying different broad swaths of the metropolitan area (Farley et al. 1993). But beyond white flight, the tendency for whites to remain in neighborhoods that are surrounded by predominantly minority neighborhoods points to the stability of some white communities even in the face of ever larger minority populations in the broader metropolitan area. Our results imply that, provided such neighborhoods are not themselves “invaded” by minorities, whites will often opt to remain in these areas ostensibly because of the restricted supply of attractive neighborhoods nearby. Creating gated communities may represent one method for white enclaves to cordon themselves off from surrounding areas, but white residents also appear likely to resist neighborhood racial change by relying on community solidarity and maintaining racially exclusive social organizations (Wilson and Taub 2006). From a spatial standpoint, these different migratory responses would seem to underpin the “checkerboard” dimension of segregation— pockets of white (or minority) neighborhoods surrounded by largely minority (or white) areas even within central cities and, to a lesser extent, suburbs. And this process would seem to be at least partly self-reinforcing: the more populated by minorities that surrounding neighborhoods become, the less likely whites are to leave the immediate neighborhood (holding constant the racial composition of the immediate neighborhood), and in turn whites’ low levels of out-migration impede housing vacancies into which minorities might move. Both whites’ tendency to move from neighborhoods with large minority populations and whites’ tendency to remain in (predominantly white) neighborhoods that are surrounded by neighborhoods with large minority populations imply constraints on future declines in residential segregation between racial minorities and whites.

Overall, our analysis appears to confirm theoretical arguments that whites take into consideration the characteristics of a wide range of surrounding neighborhoods when assessing the likely racial trajectory of their own neighborhood and their options for relocating to a more attractive neighborhood. From a theoretical standpoint, these results suggest that models of neighborhood racial change should attend not only to racial conditions in the immediate neighborhood, but to racial conditions in surrounding neighborhoods as well. We acknowledge, of course, that linear distance between neighborhoods —the basis of our distance-decay function— is likely to capture only crudely whites’ actual or potential exposure to minorities. As noted earlier, physical barriers and the configuration of streets and highways are likely to shape whites’ exposure to minorities in other neighborhoods, just as they do within neighborhoods (Grannis 1998). Administrative boundaries, especially school attendance zones, are also likely to shape whites’ exposure to minorities in ways that are not captured by the simple distance between neighborhoods (Saporito and Sohoni 2006). Future research would do well to explore results using spatial weighting schemes that take these factors into consideration and utilize more precise geographic data in order to further develop our understanding of the effects of extralocal neighborhood conditions. Regardless of how these refinements are approached, however, the results presented here suggest that giving greater attention to the influence of extralocal areas on inter-neighborhood migration behavior will enhance substantially our understanding of the spatial dynamics of white flight and broader patterns of neighborhood change.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by a grant from the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (R21 HD049610). We thank Glenn Deane, John Iceland, the editors of ASR, and four anonymous ASR reviewers for helpful comments on earlier versions of this paper.

Footnotes

About 94% of the householders in our sample remained in the same metropolitan area between consecutive interviews. Results using a sample excluding householders moving between metropolitan areas are similar to those reported below.

More extensive discussions of these methodologies are provided by Anselin (2001; 2003).

Even without this constraint, spatial weights determined by inverse distance are quite small beyond distances of about 10 miles.

We compared the inverse-distance weighting strategy to results using several other alternatives: 1) the adjacent-tracts approach in which wij=1 when tracts i and j share a common border and wij=0 otherwise; 2) a strategy in which spatial weights were defined as the squared distance between census tracts so that more distant extralocal tracts are presumed to be less influential relative to nearby tracts; 3) a strategy in which spatial weights are a function of logged distance so that distant tracts exert more influence on extralocal measures; and 4) a structure in which conditions in all tracts in the metropolitan are presumed to have the same influence on individual mobility decisions. Of these strategies, the inverse-distance approach produced results that fit the data best, thereby supporting the idea that the dependence of inter-tract mobility of white householders on conditions in extralocal areas corresponds best with the weighting strategy employed here.