Abstract

RNA interference (RNAi) has tremendous potential for investigating gene function and developing new therapies. However, the design and validation of proficient vehicles for stable and safe microRNA (miR) and small interfering RNA (siRNA) delivery into relevant target cells remains an active area of investigation. Here, we developed a lentiviral platform to efficiently coexpress one or more natural/artificial miR together with a gene of interest from constitutive or regulated polymerase-II (Pol-II) promoters. By swapping the stem–loop (sl) sequence of a selected primary transcript (pri-miR) with that of other miR or replacing the stem with an siRNA of choice, we consistently obtained robust expression of the chimeric/artificial miR in several cell types. We validated our platform transducing a panel of engineered cells stably expressing sensitive reporters for miR activity and on a natural target. This approach allowed us to quantitatively assess at steady state the target suppression activity and expression level of each delivered miR and to compare it to those of endogenous miR. Exogenous/artificial miR reached the concentration and activity typical of highly expressed natural miR without perturbing endogenous miR maturation or regulation. Finally, we demonstrate the robust performance of the platform reversing the anergic/suppressive phenotype of human primary regulatory T cells (Treg) by knocking-down their master gene Forkhead Transcription Factor P3 (FOXP3).

Introduction

RNA interference (RNAi) has proven essential for gene function studies and holds promise for the development of new molecular medicines.1,2 RNAi is endogenously mediated by microRNA (miR), 21–24 nucleotides noncoding RNA which fine-tunes expression of a large numbers of target genes.3 miRs are generated from primary transcripts (pri-miRs) generally transcribed from polymerase-II (Pol-II) promoters and processed in the nucleus by Drosha, an RNase III like enzyme, to ~60–70 nucleotides stem–loop (sl) molecules with two-nucleotide 3′ overhangs (pre-miR). Pre-miRs are shuttled by exportin 5, a Ran-GTPase, to the cytosol where Dicer, another RNase III like enzyme, releases a 21–24 double-stranded RNA from the stem. This is loaded into the RNA-induced silencing complex (RISC), which generally selects one of the two strands as the guide strand (mature miR), according to thermodynamic properties. RISC targets mRNA with complementary sequence to the miR and downregulates their expression decreasing transcript translation and stability by a variety of molecular mechanisms.4 Because most miR:mRNA pairing in mammalian cells is not perfect, direct RISC-dependent mRNA cleavage is unusual. However, substantial knockdown of mRNA can be obtained using exogenous synthetic small interfering RNA (siRNA) perfectly complementary to the transcript, which induces its cleavage.5

Several hurdles still prevent full exploitation of the biological and therapeutic potential of RNAi. Selection of an efficient siRNA sequence still requires empirical validation, and safe and effective delivery of RNAi molecules remains an active area of investigation.6,7,8,9,10,11,12 Ongoing efforts aim to identify which approach guarantees the best balance between efficacy and off-target effects/toxicity and which expression cassette and delivery vehicle best fit the requirements of stable RNAi delivery.2

Commonly siRNA are transiently delivered to target cells by transfection approaches, a constraint that limits the possible applications. Hence, other strategies have been pursued to express RNAi precursors from within the target cells. Short hairpin RNA mimic the pre-miR structure and require Dicer processing in order to be functional. A crucial advantage is the possibility to use polymerase-III promoters for high-level expression and stable gene knockdown.13 Although polymerase-III promoters have also been engineered for inducible expression,14 they lack the tissue and developmental specificity of Pol-II promoters. Furthermore, concerns on the potential toxicity of this approach have been reported due to the possible saturation of miR processing steps and consequently interference with endogenous miR regulation.6,9,15

Artificial miRs (amiRs) are natural pri-miR in which the stem sequence of an miR has been substituted with a sequence targeting the gene of interest. In target cells, amiR undergoes the same processing steps of the parental pri-miR.16 Importantly, amiR can be also transcribed by Pol-II promoters, like endogenous pri-miR, which allows exploiting state-of-the art gene expression cassettes and may alleviate concerns for overexpression. Despite many examples in the literature of functional amiR and many of the details for making amiR having been worked out, the choice of an optimal pri-miR backbone for robust and versatile amiR expression and the criteria for its validation are still actively pursued.17,18,19,20

In order to coexpress RNAi and a selector or therapeutic gene, amiRs have been introduced into the 5′- or 3′-untranslated region (UTR) of the transgene.21 This modification, while improving amiR expression, impairs expression of the linked transgene. More recently, amiRs were inserted within an intron to maintain expression of the transgene unaltered.17,22,23,24,25,26,27 However, these features of the expression cassette may interfere with delivery by γ-retroviral and lentiviral vectors (LVs), the preferred systems for stable expression in proliferating cells and tissues. Thus, optimization of vector design is still required to perform knockdown studies in challenging settings, such as primary cells.

Here, we optimize several of these aspects to develop a versatile lentiviral platform28,29 for regulated and multiple miR/siRNA delivery and demonstrate its robust performance by knocking-down the master gene Forkhead Transcription Factor P3 (FOXP3)30 in human primary regulatory T cells (Treg).

Results

Generation of constitutive and self-regulated miR expressing LVs

We first constructed a series of LVs with self-inactivating long-term repeat29 in order to find the optimal arrangement for coexpressing an miR together with a reporter transgene (Figure 1a, left and b,c). We inserted ~200 bp from the hsa pri-miR 223 sequence, comprising the sl structure, into the 5′- or 3′-UTR of an expression cassette made of the elongation factor 1-α (EF1α) promoter and first intron and a complementary DNA for the truncated form of the low affinity nerve growth factor receptor (ΔLNGFR). We chose miR 223, which is expressed to high levels (>103 copies/pg small RNA) in myelomonocytic cells and almost undetectably in other cell types,31 in order to reliably assess exogenous miR expression in several cell types without the confounding influence of the endogenous counterpart and hypothesizing that robust expression also indicated efficient post-transcriptional processing.

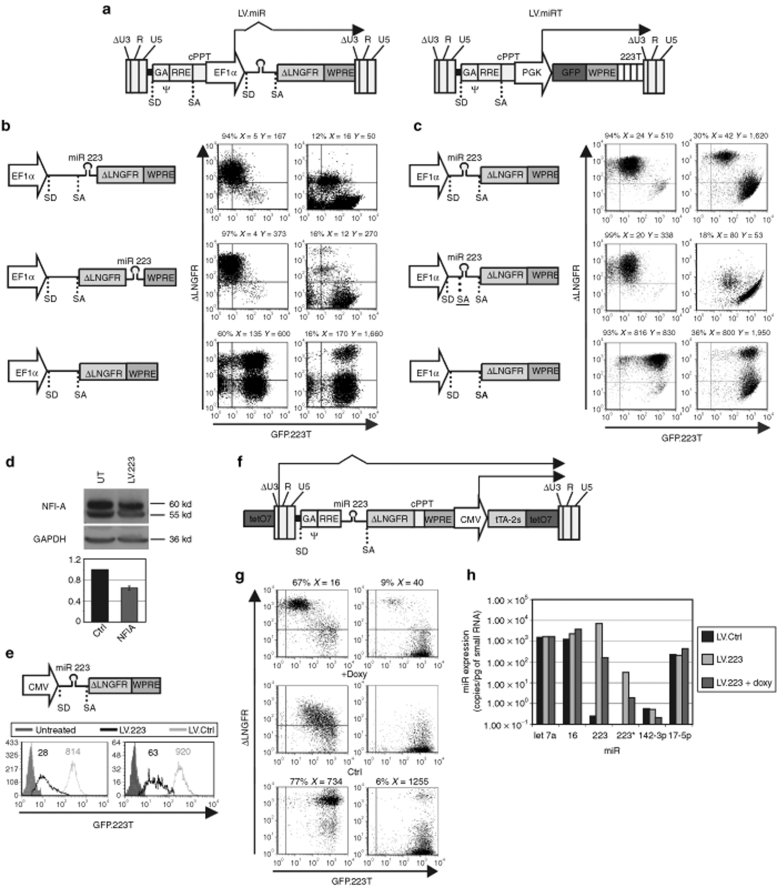

Figure 1.

Constitutive and self-regulated coexpression of miR and marker gene by LV. (a) Schematics of the LV used for expressing miR (left; LV.miR) and for reporting miR activity (right; LV.GFP.miRT). Proviral forms are shown, arrows indicate transcripts. For abbreviations see below. (b,c) HeLa cells were transduced with LV.GFP.223T and, after 1 week, with high and low MOI (right and left plots, respectively) of the depicted LV.223 or no-miR vectors (schematic of the expression cassette on the left). One week later cells were analyzed by FACS. The frequency of ΔLNGFR+ cells and their GFP (X) and ΔLNGFR (Y) MFI are indicated on top of each plot. (d) Representative western blot analysis of NFI-A expression in K562 cells either untreated or transduced with LV.223. Densitometric analysis of the NFI-A band is shown below, using GAPDH as normalizer, and the value are presented relative to no-miR LV transduced cells (64 ± 2%, mean ± SD). (e) GFP.223T HeLa, generated as above, were transduced with high (left) and low (right) MOI of the depicted LV.223 and no-miR vectors (LV.Ctrl) and analyzed as in b. Histograms show GFP expression of the ΔLNGFR+ cells. GFP MFI is indicated. Untreated cells—without GFP reporter—are shown for reference. (f) Schematic of the self-regulated LV.223. (g) GFP.223T HeLa were transduced with high (left) and low (right) MOI of the self-regulated LV.223 and a cognate no-miR vectors (LV.Ctrl), kept with or without 500 ng/ml doxycycline and analyzed as in b. (h) miR expression levels by RT-qPCR analysis in GFP.223T HeLa transduced with high MOI of the indicated self-regulated LV. All results shown are representative of at least two independent experiments performed on different batches of reporter cells and at ≥3 MOI (except for h, which was performed only for high MOI transduced cells) with similar results. CMV, immediate/early enhancer promoter of the human cytomegalovirus; cPPT, central polypurine tract; ctrl, control; GAPDH, glyceraldehyde 3 phosphate dehydrogenase; EF1α, human elongation factor 1 α promoter, 1st exon and intron; FACS, fluorescence activated cell sorting; GFP, green fluorescent protein cDNA; LV, lentiviral vector; MFI, mean fluorescence index; miR, microRNA; MOI, multiplicity of infection; NFI, nuclear factor I A; PGK, human phosphoglycerate kinase promoter; RRE, Rev responsive element; RT-qPCR, reverse transcription quantitative PCR; SA, splice acceptor site; SD, splice donor site; tetO7, tetracycline dependent promoter made by replacing the U3 sequence from position −418 to −36 with seven tandem repeats of tetracycline operators; tTA-2S, synthetic gene for the tetracycline dependent transactivator-2 cDNA; UT, untransduced cells; WPRE, woodchuck hepatitis virus post-transcription regulatory element; ΔLNGFR, truncated human low affinity nerve growth factor receptor cDNA; ΔU3, R and U5, HIV-1 LTR regions with −18 deletion relative to R in U3; ψ, encapsidation signal including the 5′ portion of the gag gene (GA); 223T, four tandem copies of a perfectly complementary target sequence for miR 223.

To functionally evaluate miR activity, we generated reporter cell lines by transducing HeLa cells with LV expressing a green fluorescent protein (GFP) transcript tagged with four copies of a sequence perfectly complementary to the mature miR 223 (GFP.223T) in the 3′-UTR (Figure 1a, right).31,32 Once GFP expression reached steady state, the cell line was transduced a second time with serial dilutions of the miR and no-miR vectors. About 7 days after the second round of transduction, we evaluated both GFP repression and ΔLNGFR expression (Figure 1b). Both LV.miRs were equally proficient in repressing GFP approximately tenfold at single vector copy, as obtained after transduction at low multiplicity of infection (MOI 0.1–0.2, yielding <20% ΔLNGFR+ cells), and ~30-fold after transduction at high MOI (MOI 10, yielding >80% ΔLNGFR+ cells). However, there were clear differences in the mean fluorescent intensity of the ΔLNGFR reporter, which was ~30- or ~6-fold lower than the no-miR vector for the 5′-UTR and the 3′-UTR vector, respectively. The detrimental effect on ΔLNGFR expression can be due to the mutually exclusive processing pathways required for the generation of miR versus mRNA. In fact, if these transcripts are cleaved by Drosha to release the pre-miR, they will loose either the 5′-cap or the poly-A tail and likely be rapidly degraded. To overcome this hurdle, we placed the miR sequence within the EF1α intron (Figure 1c). In addition to efficient GFP repression, this vector was able to express ΔLNGFR to the same level as the no-miR vector, likely due to the splicing event which separates the two pathways, therefore, avoiding competition and maximizing the efficiency of both processes. To demonstrate that this improvement is due to the intronic miR placement, we restored the naturally occurring splicing acceptor sequence upstream of the miR 223 sl. Upon this modification, the miR sequence remains in the same position within the vector but should not be spliced out. As expected, the modified vector behaved like the 5′-UTR vector, effectively downregulating GFP while expressing ΔLNGFR at reduced levels compared to the no-miR vector.

We confirmed splicing of the intronic vector RNA in transduced cells by reverse transcription quantitative PCR (RT-qPCR) specific for the spliced and the unspliced transcript using both SyberGreen chemistry and TaqMan assays. The spliced mRNA was on average 140-fold more abundant than the unspliced transcript for the different vectors tested, irrespective of whether they contained or not an miR within the intron (Syber ΔCT = 7.3 ± 0.1, mean ± SD, n = 4; TaqMan ΔCT = 7.12 ± 0.24, mean ± SD, n = 4; see Materials and Methods).

Based on these data, we selected the intronic vector as the best performing one and used this design for the rest of the study.

To biologically validate the activity of LV.223, we tested its ability to repress a validated endogenous target (Figure 1d).33 We transduced K562 erythroleukemia cells and analyzed expression of nuclear factor I A by western blot. miR 223 overexpression by LV.223 resulted in a 40% decrease of nuclear factor I A protein (n = 3). As compared to the GFP.223T reporter, the natural target contains only one imperfectly complementary miR 223 target sequence, thus repression is expected to occur mostly at the translational level and to an overall lower efficiency.

In order to assess the possibility of exploiting the miR-containing EF1α intron under the control of a different promoter, we replaced the internal EF1α promoter with the cytomegalovirus promoter and obtained comparable knockdown of GFP expression (Figure 1e). However, both cytomegalovirus and EF1α promoters drive transcription constitutively, although the possibility to switch on and off miR expression would be of greater interest for functional studies. Thus, we adapted our previously reported self-regulated LV34 by inserting miR 223 into the human immunodeficiency virus-1 intron under the control of the hybrid Tet-operator long-term repeat (Figure 1f). In this inducible vector, miR expression is transcriptionally coupled to the ΔLNGFR reporter. In the “on” condition, the vector downregulated GFP ~30-fold at single vector copy and up to ~50-fold after transduction at high MOI, while inducing robust ΔNGFR expression (Figure 1g). Administration of doxycycline (“off” condition) recovered GFP expression and concomitantly switched off ΔLNGFR. The reversion was complete when using low MOI, although some leakiness intrinsic to the Tet system was detectable at high MOI. These results were supported by directly measuring mature miR 223 levels by RT-qPCR, which indicates a range of miR regulation by doxycycline of ~40-fold, without perturbation of other endogenous miR (Figure 1h). Because qPCR reactions performed with synthetic standards for all measured miR had a similar amplification efficiency (1.95 < E < 1.97), miR concentrations in experimental samples were calculated using a standard curve based on synthetic let-7a RNA.

Next, we replaced the pri-miR 223 sequence in the LV with that derived from other pri-miR, including mmu miR 142, hsa miR 146, and hsa miR 126, and transduced reporter cell lines expressing GFP transcripts carrying the cognate miR target sequences (GFP.miRT; Figure 2a and data not shown). All new LV.miR downregulated GFP approximately tenfold at single vector copy and ~30-fold after high MOI transduction, while efficiently expressing ΔLNGFR. The natural pri-miR 142 generates substantial amounts of mature miR from both strands of the sl, miR 142-5p and miR 142-3p. Hence, we verified the proficiency of our LV.142 at producing both miR species by transducing two different reporter cell lines, GFP.142-3pT and GFP.142-5pT. We observed repression of both target sequences, with miR 142-3p showing similarly strong activity as observed for the other miR and miR 142-5p showing lower activity, possibly reflecting a preferential 142-3p loading into RISC.

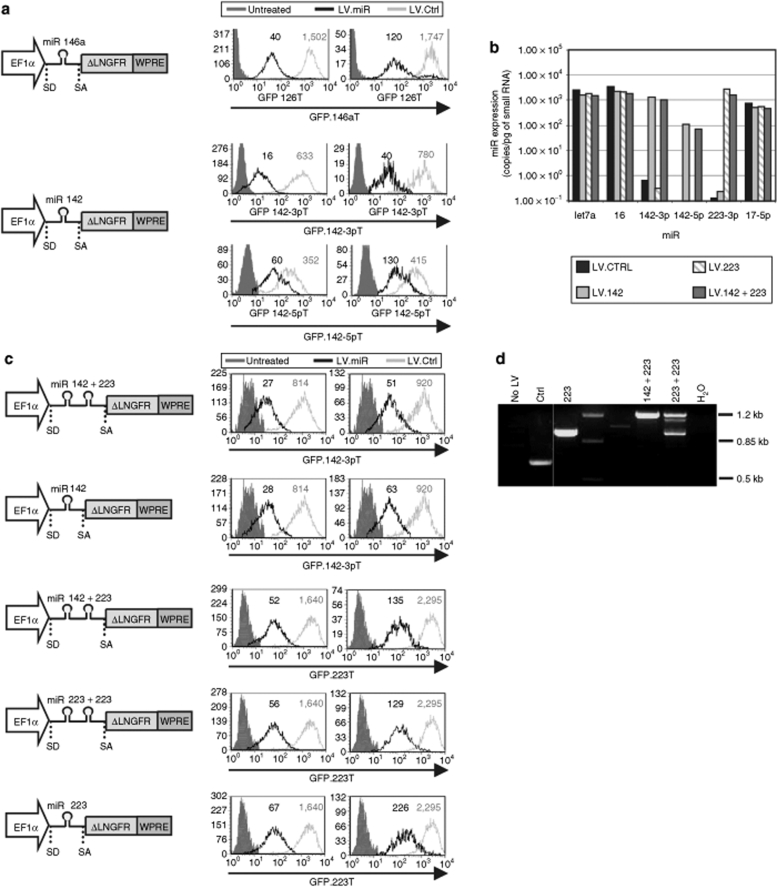

Figure 2.

Multiple miR delivery. (a,c) HeLa cells were transduced with the indicated GFP.miRT reporter vectors and, after 1 week, transduced with high and low MOI (right and left histograms, respectively) of the depicted LV.miR and no-miR vectors (LV.Ctrl), and analyzed as in Figure 1. Histograms show GFP expression of the ΔLNGFR+ cells. GFP MFI is indicated. Untreated cells—without GFP reporter—are shown for reference. (b) miR expression levels by RT-qPCR analysis in GFP.miRT HeLa cells transduced with high MOI of the indicated LV. (d) Genomic DNA was extracted from GFP.miRT HeLa cells 10 days after transduction with high MOI of the indicated LV and PCR-analyzed for miR retention using an intronic forward primer and a 5′ ΔLNGFR reverse primer. Expected fragment lengths: no-miR LV = 631 bp, LV.223 = 943 bp, LV.142 + 223 = 1,218 bp, LV.223 + 223 = 1,217 bp. Results shown are from one of two independent experiments performed on different batches of reporter cells and at ≥3 MOI (except for b and d, which were performed only for high MOI transduced cells) with similar results. ctrl, control; EF1α, human elongation factor 1 α promoter, 1st exon and intron; GFP, green fluorescent protein cDNA; LV, lentiviral vector; MFI, mean fluorescence index; miR, microRNA; MOI, multiplicity of infection; RT-qPCR, reverse transcription quantitative PCR; SA, splice acceptor site; SD, splice donor site; WPRE, woodchuck hepatitis virus post-transcription regulatory element; ΔLNGFR, truncated human low affinity nerve growth factor receptor cDNA.

The functional data were in agreement with the respective concentrations of both mature miR 142 in the transduced cells, as measured by RT-qPCR (Figure 2b). The concentration of miR 223 and miR 142 driven by our LV at high MOI was between 103 and 104 copies/pg small RNA from almost undetectable levels in untransduced cells. Interestingly, miR 223 and 142 are found within this range of concentrations in myelomonocytic U937 cells, where they are naturally expressed and suppress the cognate GFPmiRT reporter of ~20- to 30-fold (see Figure 1 and ref. 31). Thus, our LV can reconstitute miR to wild-type specific activity (as indicated by the ratio between repression and concentration) and within the range of concentration and activity typical of highly expressed natural miR, such as miR 16 and let-7a. Moreover, this analysis showed that unrelated miR were unaffected by exogenous miR expression.

Multiple miR delivery

We investigated whether our design could be adapted to deliver multiple miR from a single LV. We generated a construct carrying the sequences of pri-miR 223 and pri-miR 142 in tandem (LV.223 + 142) and tested its activity in repressing GFP.223T and GFP.142-3pT in comparison with single miR and no-miR vectors (Figure 2c). LV.223 + 142 repressed both GFP reporters similarly or slightly better than the cognate single LV.miR. This result was confirmed by RT-qPCR, which showed that the double copy LV gave similar yields of both miR 223 and miR 142, comparable to the level obtained by each single LV.miR (see Figure 2b).

We then sought to increase miR 223 expression level by inserting two miR 223 copies in tandem (LV.223 + 223). Although this LV repressed GFP slightly better than the single LV.223, genomic PCR analysis performed to assess miR sequence retention showed both the expected size for two integrated tandem copies of miR as well as a smaller band corresponding to only one miR copy (Figure 2d). Importantly, we did not observe a similar rearrangement in cells transduced by LV.223 + 142, suggesting that the two-miR configuration is unstable only when there are repeats between the two miR.

Heterologous miR expression by sl replacement

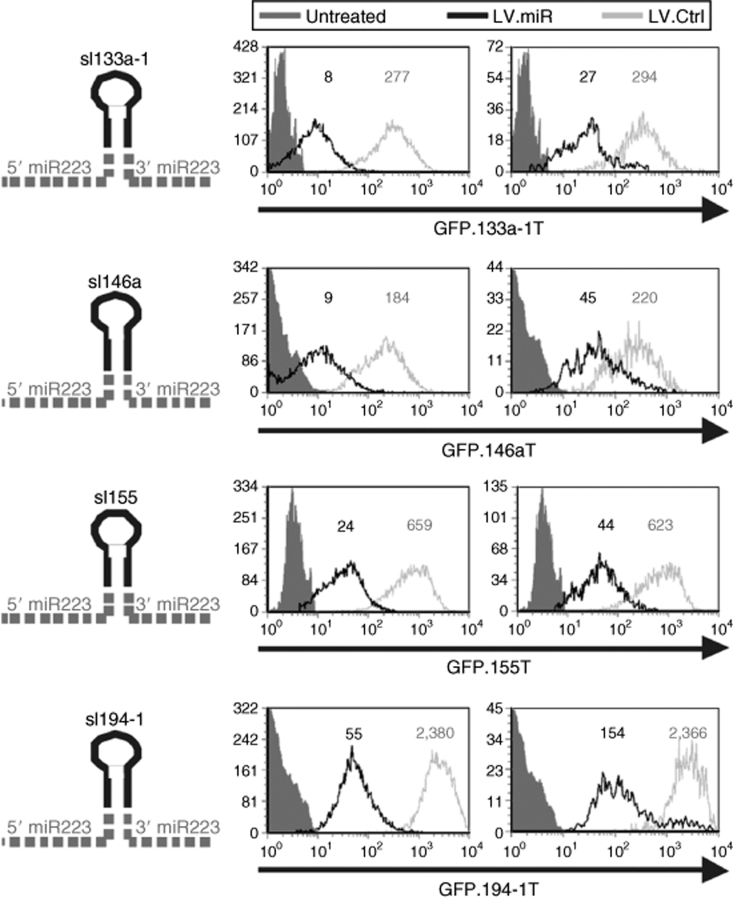

We then determined whether the pri-miR 223 backbone inserted in our LV could be exploited to express other miR or siRNA molecules. We first replaced the upper sl of miR 223 with the sl of other miR, keeping the miR 223 flanking sequences in the vector unmodified. We constructed LV.223 with the sl of hsa miR 133, 194, 155, and 146 and evaluated mature miR activity from these sl-chimeric LV.miR (LV.slmiR) in reporter cell lines expressing the cognate GFP.miRT (Figure 3). Except for LV.sl146, which showed a slightly lower activity than its wild-type counterpart (Figure 2a), all other LV.sl-chimeric miR tested repressed the cognate GFP as efficiently as LV.223, showing that our platform allows reproducible exogenous miR expression.

Figure 3.

Heterologous miR expression. The pri-miR 223 upper stem–loop (sl) was replaced by that of other miR, as depicted on the left, and the chimeric miR and no-miR vectors (LV.Ctrl) were used to transduce at high and low MOI (left and right histograms, respectively) GFP.miRT HeLa cells as in Figure 1. Histograms show GFP expression of the ΔLNGFR+ cells. GFP MFI is indicated. Untreated cells—without GFP reporter—are shown for reference. Results shown are from one of two independent experiments performed on different batches of reporter cells and at ≥3 MOI with similar results. ctrl, control; GFP, green fluorescent protein cDNA; LV, lentiviral vector; MFI, mean fluorescence index; miR, microRNA; MOI, multiplicity of infection; WPRE, woodchuck hepatitis virus post-transcription regulatory element; ΔLNGFR, truncated human low affinity nerve growth factor receptor cDNA.

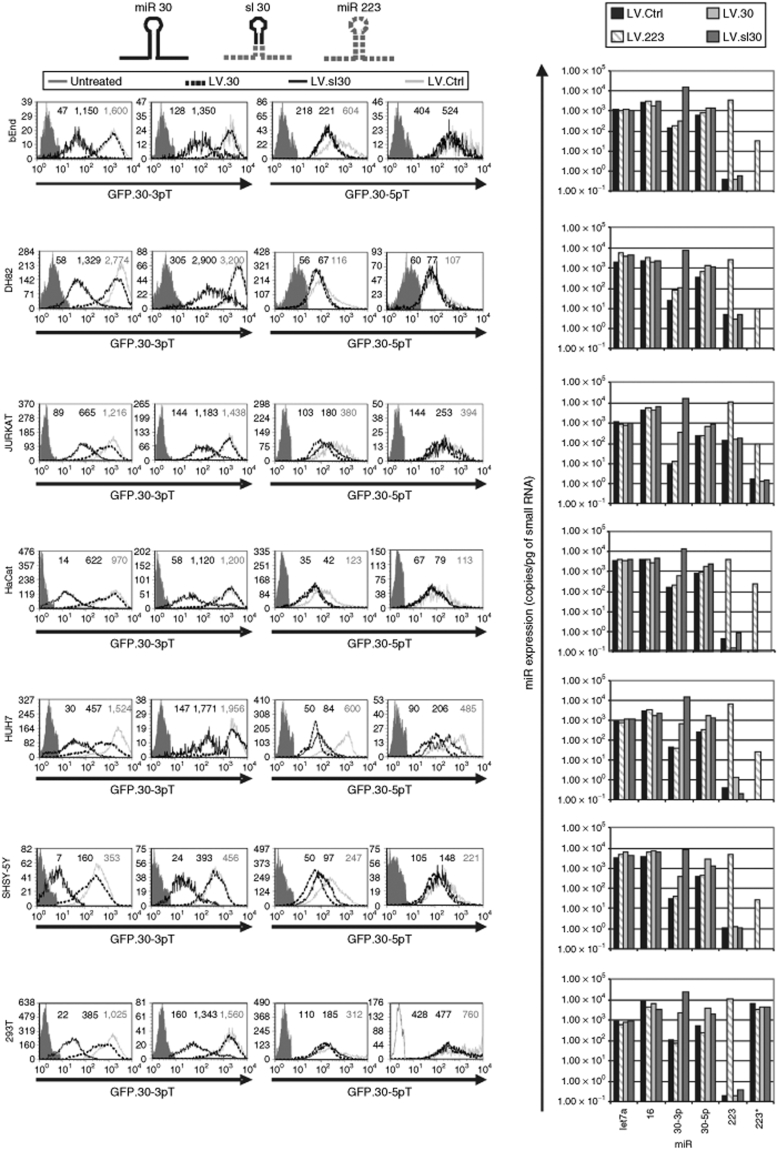

Pri-miR sequences have been engineered to express short hairpin RNA libraries from the miR 30a (ref. 16) and, more recently, the miR 155 backbone.17 Surprisingly, when we incorporated the same pri-miR 30a sequence in our vector (LV.30), we observed a much weaker activity as compared to LV.223 in repressing the cognate GFP reporters stably introduced in several cell lines from different tissues and species (Figure 4, left panels). We investigated whether the lower repressive activity of miR 30 was dependent on inefficient processing. We generated an sl-chimeric LV.sl30 within our miR 223 backbone and compared it to the LV.30. Because endogenous miR 30 generates mature miR from both strands of the stem, miR 30-5p and miR 30-3p, we evaluated both LV.sl30 and LV.30 in GFP.30-5pT and GFP.30-3pT reporter cell lines derived for each cell type tested. As a reference, we concomitantly tested LV.223 on its cognate GFP.223T reporter cells (Supplementary Figure S1). In all cell types, LV.sl30 repressed GFP.30-3pT to similarly high levels as shown by LV.223 with its own GFP-223T reporter. LV.30 was at least tenfold less active than LV.sl30 in all cell types and only showed weak repression of GFP.30-3pT up to threefold at high MOI. On the other hand, GFP.30-5pT was only slightly repressed, about threefold, by either LV.sl30 or LV.30, except for HUH7, in which GFP repression reached tenfold.

Figure 4.

Expression and activity of mature miR 30 upon delivery within the pri-miR 223 or its own backbone in different cell types. The indicated cell lines were transduced with the GFP.30-3pT or GFP.30-5pT reporter LV and, after 1 week, with high and low MOI (left and right histograms, respectively) of the indicated LV.miR/chimeric miR and no-miR vectors (LV.Ctrl). Schematics of the parental and chimeric pri-miR are shown on top; sl, miR upper stem–loop. Cells were analyzed by FACS (left) and RT-qPCR (right), at 7 and 14 days after transduction, respectively, as in Figure 1. FACS histograms show GFP expression of the ΔLNGFR+ cells. GFP MFI is indicated. Untreated cells—without GFP reporter—are shown for reference. Results shown are from one of two independent experiments performed on different batches of reporter cells and at ≥3 MOI (except for RT-qPCR which was performed only for high MOI transduced cells) with similar results. Cell lines used: bEnd, murine brain endothelial; DH82, canine monocytic; JURKAT, human T lymphoblastoid; HaCat, human keratinocytic; HUH7, human hepatocytic; SHSY-5Y, human neuroblastoma; 293T, human kidney carcinoma. FACS, fluorescence activated cell sorting; GFP, green fluorescent protein cDNA; LV, lentiviral vector; MFI, mean fluorescence index; miR, microRNA; MOI, multiplicity of infection; RT-qPCR, reverse transcription quantitative PCR; ΔLNGFR, truncated human low affinity nerve growth factor receptor cDNA.

We then evaluated miR concentration by RT-qPCR in cells transduced with comparable LV copy numbers (Figure 4, right panels). In all cell types, miR 30-3p was endogenously expressed to low levels, <100 copies/pg small RNA, and was increased >100-fold by LV.sl30 and only from two- to tenfold by LV.30. On the other hand, miR 30-5p was endogenously expressed to relatively high levels, between 300 and 1,000 copies/pg small RNA, and was modestly increased by both LV, between two- and fivefold. miR 223 was almost undetectable (<1 copy/pg small RNA) in all cell types except Jurkat cells, and was strongly overexpressed upon LV.223 transduction reaching concentrations ranging between 1,000 and 10,000 copies/pg small RNA, similar to those observed for miR 30-3p when it was expressed from the 223 backbone by LV.sl30. Importantly, expression of LV.223 showed a strong bias for the mature 223 strand versus the 223* or passenger strand, with >100-fold difference between the concentration of each mature product. This bias reproduces that observed for the endogenous miR 223, as it can be seen in the Jurkat cells. These results suggested less-efficient processing of miR 30 from its own backbone than from that of miR 223.

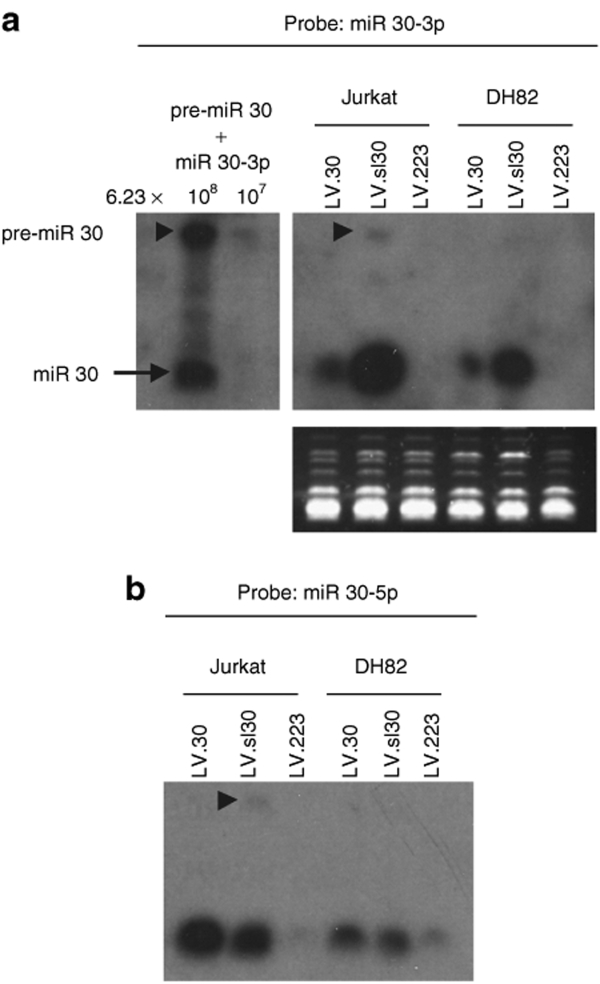

We then analyzed two representative vector-transduced cell lines by northern blot for miR 30, which allows for the simultaneous detection of pre-miR and mature miR (Figure 5). We detected mostly mature miR 30 forms in both Jurkat and DH82 cells transduced with LV.sl30 and LV.30, indicating proficient Dicer processing of both pre-miR. Mature miR 30-3p was much more abundant in LV.sl30-transduced cells as compared to the LV.30 ones, while miR 30-5p was similarly expressed from both vectors. These results are consistent with the repressing activity exerted on miR 30-3p and -5p reporters shown above. Moreover, by determining miR concentrations in the RNA samples analyzed by northern blot relative to miR 30 standards, we confirmed the results of the qPCR assays. LV.sl30 and LV.30 expressed the ΔLNGFR marker at similar levels in matched conditions (data not shown), suggesting similar expression levels for the pri-miR, which are transcriptionally linked to the ΔLNGFR gene. Because pri-miR expression and pre-miR processing appear similarly proficient for LV.sl30 and LV.30, the observed difference in miR expression likely occurs at the Drosha cleavage and/or nuclear export step.

Figure 5.

Northern blot analysis for miR 30 expression and processing by LVsl30 and LV.30. Cell lines were transduced with the indicated vectors at high MOI (same samples shown in Figure 4) and small RNA were extracted. Blot was probed for (a) miR 30-3p or (b) miR 30-5p. Left, the indicated number of copies of oligonucleotides corresponding to the pre-miR 30 (63 nucleotides) and mature miR 30-3p (22 nucleotides) were loaded on the gel as standards. Bottom, ethidium bromide shows similar RNA loading. a and b are the same filter. Arrow heads indicate the pre-miR band. Results shown are from one of two similar experiments performed. LV, lentiviral vector; miR, microRNA; MOI, multiplicity of infection; pri-miR, primary transcript.

Overall, these results indicate that the miR 223 backbone provides more efficient miR expression than the miR 30 backbone and can be used to robustly force expression of an exogenous miR sl. Moreover, overexpression occurs preferentially for one strand, possibly reflecting the natural bias of 223.

The RT-qPCR data (Figures 1–4) show that LV.miR does not alter expression of the endogenous miR tested, suggesting lack of competition/saturation of processing enzymes. miR detection, however, does not necessarily imply RISC loading and target repression. Thus, we transduced HeLa cells, which endogenously express miR 15 or 16 (Figures 1f and 2c and data not shown) with LV.GFP.15T or LV.GFP.16T reporters and showed the expected GFP repression. Upon further transduction of these cells with LV.223 at high MOI, there was no detectable increase in GFP expression, suggesting lack of interference with miR 15 and 16 activity in our experimental conditions (data not shown).

Engineering LV.223 for siRNA expression and validation in human primary cells

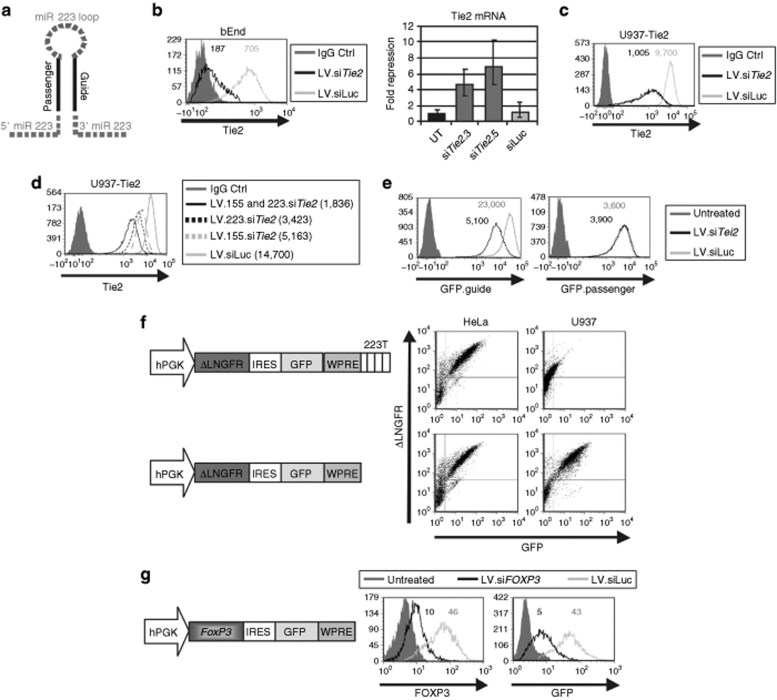

In order to adapt LV.223 to siRNA expression, we replaced the upper stem of miR 223 with perfectly base-paired 21-bp siRNA maintaining the flanking and loop sequences of LV.223, thus generating artificial miR (amiR) against a gene of interest (Figure 6a).

Figure 6.

siRNA delivery by LV.amiR. (a) The pri-miR 223 upper stem was replaced by siRNA against the indicated gene of interest to generate an amiR, as shown in the schematic. (b) bEnd cells were transduced with LV.amiR against murine Tie2 (LV.siTie2) or luciferase (LV.siLuc) at high MOI and analyzed by FACS and RT-qPCR after 7 and 14 days, respectively. Left histogram shows the endogenous Tie2 expression of the ΔLNGFR+ cells. Tie2 MFI is indicated. Isotype control stained cells are shown for reference. Right bar histogram shows fold of Tie2 mRNA downregulation as calculated by RT-qPCR (error bars represent 95% of the confidence interval for each value). (c) U937 cells engineered to express murine Tie2 were transduced with LV.siTie2 and LV.siLuc vector at high MOI and analyzed as above. (d) U937-Tie2 cells were transduced with the indicated single and double amiR vector at low MOI and analyzed after 14 days as above. Tie2 MFI is indicated in the legend. (e) Reporter cell lines were generated by transducing HeLa cells with vectors encoding for GFP tagged with a fragment of the Tie2 cDNA (GFP.guide) or its complement (GFP.passenger). These cells were then transduced with LV.siTie2 and LV.siLuc vector at high MOI and analyzed as above. (f) U937 and HeLa cells, which naturally express or not miR223, were transduced with the depicted bicistronic LV carrying or not four copies of the miR 223 perfectly complementary target sequence. Both vectors efficiently express both marker genes in HeLa cells. Expression of both genes was suppressed in U937 cells from the miR.223T vector while expression of control vector was unaffected. (g) HeLa cells were engineered to express human FOXP3 by transduction with the depicted bicistronic LV and then transduced with LV.siFOXP3 and siLuc vector. Cells were analyzed by FACS after 10 days for FOXP3 and GFP expression. Histograms show FOXP3 and GFP expression of the ΔLNGFR+ cells. FOXP3 and GFP MFI are indicated. Untreated cells—without GFP reporter—are shown for reference. Results shown are representative of at least two independent experiments performed with similar results. ctrl, control; FACS, fluorescence activated cell sorting; FOXP3, Forkhead Transcription Factor P3; GFP, green fluorescent protein cDNA; IRES, internal ribosomal entry site; LV, lentiviral vector; MFI, mean fluorescence index; miR, microRNA; MOI, multiplicity of infection; RT-qPCR, reverse transcription quantitative PCR; UT, untransduced cells; WPRE, woodchuck hepatitis virus post-transcription regulatory element; ΔLNGFR, truncated human low affinity nerve growth factor receptor cDNA.

We first evaluated LV.siRNA against the murine angiopoietin receptor 2 (Tie2/Tek).35 We tested several LV.siTie2 on mouse brain–derived endothelial cells and evaluated downregulation of the endogenous protein, by fluorescence activated cell sorting (FACS), and mRNA, by RT-qPCR (Figure 6b). The two best-performing LV.siTie2 almost completely shutoff Tie2 expression at FACS and reduced its mRNA by 7- and 4.5-fold, respectively, as compared to LV.siRNA against luciferase (LV.siLuc) or no-miR vectors. To more reliably quantify the extent of protein suppression, we transduced the two LV.siTie2 into U937 cells overexpressing mouse Tie2 and detected downregulation of the protein by approximately ten- and fivefold, respectively (Figure 6c and data not shown). Note that the repression of an endogenous gene is expected to be lower compared to the repression of the GFP.miRT reporters used previously, because there is only one copy of the siRNA target sequence in the mRNA instead of four in the reporter transcript.

In order to improve gene knockdown at single vector copy, we generated vectors encoding for two siRNA directed against different regions of the Tie2 mRNA. To avoid recombination between repeated sequences during reverse transcription (as shown in Figure 2d), we used the miR 155 scaffold17,22 in tandem with our miR 223 scaffold. The best-performing miR155.siTie2 out of five tested was then cloned together with the miR233.siTie2 into the intron of our LV. We compared the performance of this double siRNA vector with that of each single siRNA vector and the LV.223.siLuc, LV.155.siLacZ, and LV.155.siLacZ.223.siLuc control vectors (Figure 6d and data not shown). U937-Tie2 cells were transduced with these vectors at single vector copy and analyzed by FACS at increasingly longer time points after transduction. The double siTie2 vector repressed Tie2 expression approximately tenfold, twice as much as the best single siTie2 vector. This repression remained stable at increasingly longer times post-transduction (data not shown), although Tie2 expression was unaffected by any of the control vectors.

Next, to evaluate whether our LV.223.siTie2 can favor strand-specific RISC loading, we generated two new LV.GFP reporter vectors tagged with sequences perfectly complementary to either the guide or the passenger strand of the amiR. The guide reporter thus contains a fragment of the Tie2 coding sequence targeted by the siRNA incorporated into the amiR downstream to GFP, whereas the passenger reporter contains its complement. With these two vectors, we generated reporter cell lines and transduced them with serial dilutions of LV.223.siTie2 or control LV.223.siLuc vectors. LV.223.siTie2 specifically and strongly repressed the guide reporter with no detectable effect on the passenger reporter (Figure 6e). These results indicate that the amiR generated for our study mediated effective and specific RISC loading of the guide strand, reducing the potential siRNA off-target effects due to the passenger strand.

We expanded our findings by generating and testing other LV.siRNA against human FOXP3. As Treg are difficult to obtain in large numbers and require high vector titer for transduction, we first generated a reporter cell line expressing the FOXP3 complementary DNA from an internal ribosomal entry site (IRES)-based bicistronic transcript containing GFP as second gene. We demonstrated that RNAi targeting of bicistronic transcripts results in downregulation of both transgenes (Figure 6f) and then compared the efficacy of different LV.siFOXP3 on FOXP3.IRES.GFP HeLa cells (Figure 6g and data not shown). The two best-performing vectors were able to repress GFP approximately ten- and fivefold, respectively. We confirmed efficient reduction of FOXP3 expression by FOXP3 intranuclear staining.

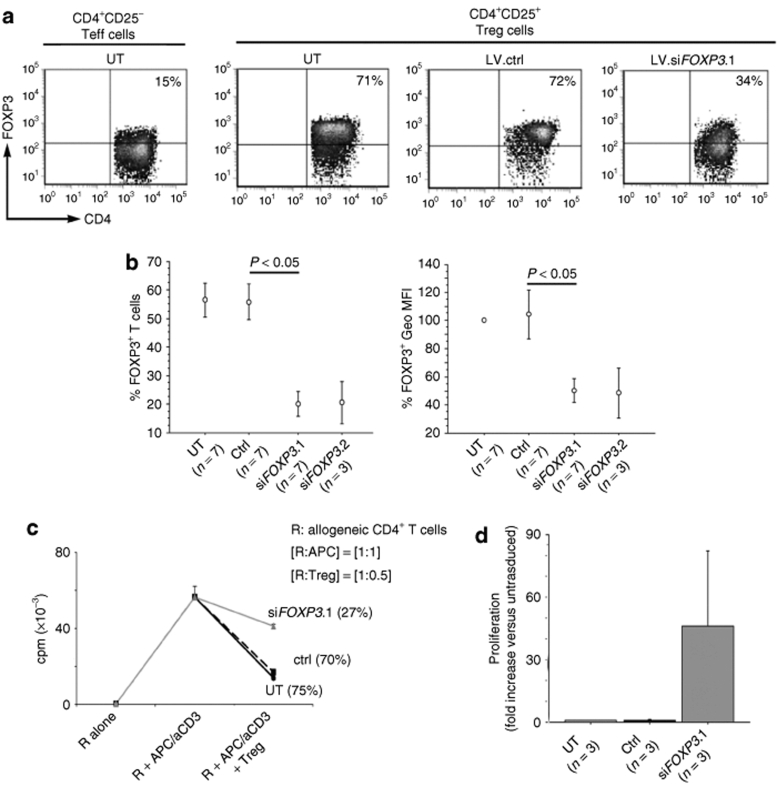

We then transduced human primary CD4+CD25bright T cells sorted by FACS with either LV.siFOXP3 or control LV.siLuc. Upon a single hit at MOI 20 (2 × 107 transducing units of HeLa/ml), transduction efficiency ranged from 30 to 85%, as assessed by ΔLNGFR staining (Figure 7a), and significant downregulation of FOXP3 was obtained in LV.siFOXP3-transduced cells as compared to LV.siLuc or mock transduced Treg cells (Figure 7b). After 14 days of in vitro culture the percentage of FOXP3+ cells was 20 ± 4% (mean ± SE) with LV.siFOXP3.1 (n = 7) and 21 ± 7% with LV.siFOXP3.2 (n = 3) versus 56 ± 6% in LV.siLuc (n = 7) or mock cells (n = 7) (P < 0.05, for LV.siFOXP3.1). In addition, the FOXP3 mean fluorescent intensity was 2.1- and 2.2-fold lower in LV.siFOXP3.1 and LV.siFOXP3.2, respectively, versus LV.siLuc Treg cells. FOXP3 suppression remained similar after two rounds of T-cell receptor stimulation and 3–4 weeks of culture.

Figure 7.

Knockdown of FOXP3 expression and reversion of suppressive phenotype of human Treg cells by LV.siFOXP3. FACS sorted human CD4+CD25bright Treg cells were transduced with the indicated LV.siFOXP3 or LV.siLuc vector at MOI 20. After 14 days of culture cells were stained for FOXP3 expression. (a) Representative FACS density plots; percent of positive cells is indicated. UT, untransduced cells. (b) Percent FOXP3 positive cells (left) and MFI of FOXP3 staining relative to UT (right) of the indicated samples. Results are presented as mean ± SE. Significance assessed by Mann–Whitney test. (c) The ability of LV.siFOXP3 transduced Treg cells to suppress the proliferation of allogeneic CD4+ responder T cells was assessed at a 1:0.5 responder: Treg ratio by evaluating 3[H]-thymidine incorporation after stimulation with antigen presenting cells (APC) and anti-CD3 antibody and 3-day culture. In these conditions, LV.siFOXP3 Treg cells remained anergic. Representative experiment out of five performed with similar results. (d) Treg cells were activated by plate-bound anti-CD3 antibody before the proliferation assay. Results are presented as fold increase versus untrasduced Treg cells, tested in parallel. cpm, counts per minute; ctrl, control; FACS, fluorescence activated cell sorting; GFP, green fluorescent protein cDNA; LV, lentiviral vector; MFI, mean fluorescence index; miR, microRNA; MOI, multiplicity of infection; Treg, effector T cells; Teff, regulatory T cells; UT, untransduced cells.

The observed FOXP3 knockdown was enough to induce significant biological effects both at the level of Treg phenotype and function. Expression of the inhibitory molecule CTLA4 was reduced in LV.siFOXP3 cells (data not shown). For functional studies, we took advantage of the coexpressed ΔLNGFR marker to purify transduced T cells to >80% purity and tested their suppressive activity in vitro (Figure 7c). Similar to mock transduced, LV.siLuc Treg cells efficiently suppressed the proliferation of allogeneic CD4+ cells by an average of 75 ± 6% (mean ± SE, n = 4). Suppression was reduced to 49 ± 9% for LV.siFOXP3 cells (n = 5; P < 0.05). These results could not be attributed to the proliferation of LV.siFOXP3 cells, because they remained hypo-proliferative upon stimulation by antigen presenting cells and anti-CD3 antibody, as it was done in the experiments of Figure 7c (not shown). However, upon a stronger T-cell receptor stimulus mediated by plate-bound anti-CD3, LV.siLuc Treg cells remained anergic, whereas LV.siFOXP3 cells displayed a clear proliferative response (46 ± 36-fold increase for LV.siFOXP3.1, mean ± SE, n = 3, versus LV.siLuc Treg) (Figure 7d).

Overall, the FOXP3 knockdown results stringently validate our siRNA delivery platform in challenging primary target cells.

Discussion

In this study, we validate an LV platform to efficiently coexpress one or more miR/amiR together with a gene of interest. Coexpression from the same Pol-II promoter ensures tight miR coupling to the appropriate selector/marker gene, as compared to using separate promoters, and allows constant monitoring of inducible systems. Intronic miR placement allows robust coexpression of the linked gene, as an efficient splicing reaction, demonstrated by RT-qPCR, segregates the antagonistic mRNA and pri-miR maturation processes.

The pri-miR 223 scaffold was selected for heterologous miR and siRNA expression because of its high level of expression and low passenger strand activity, a feature that may reduce the likelihood of off-target effects when adapted for siRNA expression. By swapping the sl sequence with that of other miR or replacing the stem with a siRNA of choice, we consistently obtained robust strand-specific expression of the chimeric miR/amiR in several cell types.

These findings were obtained using a panel of engineered cells stably expressing sensitive reporters for miR activity and transduced with the LV miR/chimeric miR of interest. This approach allowed us to quantitatively assess at steady state the target suppression activity and expression level of each delivered miR and to compare it to those of endogenous miR. We showed similarly high levels of expression and activity for all LV miR/chimeric miR tested. Because delivery and reporter design were matched in our experimental setup, this finding indicates versatile and predictable miR delivery by our platform. The sl swap can be used for convenient and reproducible exogenous miR expression and, more interestingly, to segregate backbone and sl dependent effects on miR post-transcriptional processing and activity.36,37 For LV.223, we also verified the biological activity of the exogenous miR on a natural target.

Forced miR/amiR expression may result in adverse consequences. These include perturbation of endogenous miR maturation and/or activity, due to interference for processors and effectors, siRNA off-target effects and RISC loading of passenger strand.6,8,9,12,15 In our analysis, we monitored several endogenous miR upon LV.miR transduction, and did not find evidence of perturbation of their maturation, level or activity and verified, at least for the amiR LV.siTie2, the absence of unwanted passenger strand RISC loading.

Surprisingly, a chimeric 223.sl30 vector performed better than a vector expressing the wild-type pri-mir 30 in matched conditions. Because the only differences between these two vectors are the pri-miR flanking sequences, we suggest that the increased miR 30 output and activity is due to a more proficient nuclear processing of the 223 versus 30 pri-miR backbone. This is supported by northern blot analysis, which shows proficient pre-miR processing by Dicer for both LV.sl30 and LV.30. Interestingly, in current miR 30-based amiR,1 the siRNA targeting sequence replaces the 3p strand of miR 30, which is specifically overexpressed from our 223.sl30 chimeric as compared to wild-type miR 30. Overall, these data stringently validate the performance of our platform for amiR delivery.

Beside miR 30 (ref. 16), other miR scaffolds have been previously used to express siRNA in mammalian17,18,19,20 as well as plant cells,38 although most of these systems were mainly tested using transient transfection approaches and only few were adapted for LV delivery. The methodological approaches described here will be useful to further assess their performance.

There are concerns on the feasibility of intron delivery by retroviral vectors, especially when inserted in the same transcriptional orientation as the vector,25,39 although some reports suggest that this can occur efficiently in certain conditions.40,41 The Rev-dependent lentiviral packaging system42 allowed efficient delivery of the miR-encoding intron into target cells, as shown by GFP.miRT repression in the majority of cells carrying only one vector copy and expressing ΔLNGFR. Because splicing of the upstream viral intron is suppressed by Rev, the preservation of the downstream miR-encoding intron may be due to the unfavorable distance of its splice donor site from the 5′-cap, according to the exon definition theory43 (see vector schematic in Figure 1a). In transduced cells, transcription starts from the internal EF1α promoter, thus restoring efficient splicing, as demonstrated by RT-qPCR.

For all the single and double miR/amiR vectors described, we only observed modest if none deleterious effects on titer as compared to no-miR control vectors. This may be explained by Rev activity, which mediates cytoplasmic export of vector RNA and may inhibit pri-miR processing, or simply by Drosha saturation by the accumulating miR-containing transcripts in vector-producing cells.

Recent studies have explored coexpression of more than one miR/amiR by a single expression cassette.17,18,19,23,24 Our results support the concept that insertion of two miR in tandem does not interfere with and may even facilitate miR processing possibly by more efficiently recruiting Drosha and/or increasing transcript nuclear retention time.44 In addition, we showed that LV encoding for two amiR directed against different regions of the same mRNA have an additive effect in target downregulation, in agreement with other studies.27 However, when using retroviral delivery, the two siRNA should be embedded into different miR scaffolds to avoid recombination between repeats during retrotranscription, as also shown by others.45

Because evaluating siRNA activity against an endogenous target can be troublesome when target cells are limiting and/or the target protein is difficult to detect, we demonstrate the possibility of using IRES.GFP based bicistronic LV as a simple readout for the knockdown of the gene of interest.

The ultimate proof of performance of an siRNA delivery platform must be obtained in primary cells or in vivo, the relevant targets for gene function studies and therapeutic applications. Exploiting the good infectivity and robust amiR expression of our LV, we could transduce up to 85% human primary Treg by a single hit and achieve FOXP3 knockdown sufficient to revert their anergic phenotype and suppressive potential, highlighting the crucial importance of this transcription factor in maintaining Treg properties.46 This observation is in line with the notion that suppressive capacity is conferred to human T cells upon high and stable FOXP3 expression.46 By contrary, Treg cells in which FOXP3 has been knocked down resemble effector T cells, which do not acquire suppressive activity upon low and transient FOXP3 expression.

Materials and Methods

Plasmid construction. pCCL.sin.cPPT.hEF1α.ΔLNGFR.WPRE transfer vectors were built from the pCCL.sin.cPPT.hPGK.GFP.WPRE.29 EF1α promoter was cloned together with exon and intron 1 (ref. 47). The naturally occurring XhoI site inside the EF1α intron was used to insert a multicloning site to clone all the miR/siRNA sequences described in the text. Approximately 200 bp of miR 223 gene sequence containing the miR hairpin were cloned into pBKS and then cut with the naturally occurring NspI–PstI to replace the miR hairpin with an oligo containing two BbsI sites. Synthetic oligos for chimeric miR (retrieved from the miR registry http://microrna.sanger.ac.uk/) and siRNA were annealed and inserted inside the pBKS.miR 223 cut with BbsI. Plasmids were sequence verified and then inserted into the pCCL.sin.cPPT.hEF1α.ΔLNGFR.WPRE or other LV with different promoters. hsa pri-mir-30a was a kind gift of G.J. Hannon, hsa pri-mir 146a of D. Baltimore, hsa pri-mir-142 of C.Z. Zang, all obtained through Addgene. pCCL.sin.cPPT.hPGK.Tie2.WPRE was generated by cloning the murine Tie2 complementary DNA (kindly provided by D.J. Dumont) into the pCCL.sin.cPPT.hPGK.GFP.WPRE vector. Inducible vectors were built from our previously described LVCCL-TA4/R2 (ref. 34). LV.GFP.miRT were generated as previously described.31,32

The siRNA sequences used are: Tie2.3, 5′-TTGACGGAA ATGTTGAAAGGC-3′; Tie2.5, 5′-TTTGCCCTGAACCTTATAC CG-3′; Tie2 (miR 155): 5′-TACAGGTCCTGCCAAATGTGT-3′; FOXP3.1, 5′-AAGACCTTCTCACATCCGGGC-3′; FOXP3.2, 5′-TTGCAGACACCATTTGCCAGC-3′; LucA, 5′-TATTCAGCCCA TATCGTTTCA-3′; LucB, 5′-ATTTGTATTCAGCCCATATCG-3′; LacZ, 5′-AAATCGCTGATTTGTGTAGTC-3′. For the siRNA strand bias experiment, GFP transcript was tagged with one copy of the following sequence: GFP.guide, 5′-CGGTATAAGGT TCAGGGCAAA-3′; GFP.passenger, 5′-TTTGCCCTGAACCTTA TACCG-3′.

Reagents and sequence information are available upon request.

Vector production and titration. VSV-G pseudotyped third generation LV were produced by transient four plasmid cotransfection into 293T cells and concentrated by ultracentrifugation as described.48 Expression titer of GFP or ΔLNGFR vectors were determined on HeLa cells by limiting dilution. Vector particle content was measured by HIV-1 Gag p24 antigen immunocapture (NEN Life Science Products; Waltham, MA). Vector infectivity was calculated as the ratio between titer and particle content. Titer of 293T conditioned medium ranged from 106 to 107 transducing units/ml and infectivity from 104 to 105 transducing units/ng of p24.

Cell cultures. Continuous cultures of HeLa, 293T, HUH7, and HaCat were grown in Iscove Modifies Dulbecco's Medium (Sigma, St. Louis, MO), DH82 and bEnd in Dulbecco's Modified Eagle Medium (Sigma) and Jurkat, U937 and SHSY-5Y in RPMI 1640 Medium (Euroclone, Amsterdam, the Netherlands), all supplemented with penicillin–streptomycin, glutamine (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) and 10% fetal bovine serum (Biosera, Ringmer, UK), except HaCat and DH82 which were supplemented with 8 and 15% fetal bovine serum, respectively. Cells transduced with inducible vectors were kept with or without 500 ng/ml doxycycline (Sigma) to regulate transgene and miR expression.

Human peripheral blood was obtained upon informed consent from healthy donors in accordance with Institutional ethical committee approval. Peripheral blood mononuclear cells were prepared by centrifugation over Ficoll-Hypaque gradients. CD4+ T cells were purified by negative selection with the CD4+ T cell isolation kit (Miltenyi Biotec, Bergisch Gladbach, Germany), subsequently separated into CD25bright and CD25− fractions by FACS, with a resulting purity of >95%.

Transduction of human CD4+CD25+ Treg cells. CD4+CD25bright T cells sorted by FACS were activated for 18 hours with soluble anti-CD3 monoclonal antibody (mAb, 1 µg/ml, OKT3, Janssen-Cilag), rhIL-2 (100 U/ml) (Chiron) and autologous irradiated antigen presenting cells at a 1:5 ratio of T cells to antigen presenting cells. T cells were transduced with LV at MOI 20. ΔLNGFR+-transduced T cells were purified 9 days after transduction using ΔLNGFR-select beads (Miltenyi Biotec) and expanded in medium containing 100 U/ml rhIL-2. T cells were stimulated every 14 days in the presence of an allogeneic feeder mixture containing 106 peripheral blood mononuclear cells per ml (irradiated 6,000 rad), 105 JY cells (an Epstein–Barr virus–transformed lymphoblastoid cell line expressing high levels of human leukocyte antigen and costimulatory molecules) per ml (irradiated 10,000 rad), and soluble anti-CD3 mAb, 1 µg/ml. Cultures were maintained in X-VIVO 15 medium supplemented with 5% human serum (BioWhittaker-Lonza, Washington, DC), and 100 U/ml penicillin–streptomycin. All experiments were performed at least 12 days after activation.

T-cell proliferation and suppression assay. To assess proliferative response, T cells were plated at a density of 0.5 × 105 cells/well in a 96-well round bottom plate in a final volume of 200 µl of complete medium. T cells were activated either with plate-bound anti-CD3 mAb (1 µg/ml) or in the presence of CD3-depleted peripheral blood mononuclear cells (irradiated 6,000 rad) and soluble anti-CD3 mAb. To test Treg cell suppressive capacity, allogeneic CD4+ responder T cells were stimulated in the presence of CD3-depleted peripheral blood mononuclear cells (irradiated 6,000 rad) and soluble anti-CD3 (1 µg/ml) mAb. Responder T cells were plated at a density of 0.5 × 105 cells/well in a final volume of 200 µl of complete medium. Suppressor T cells were added at a ratio of 1:0.5 (responder:suppressor). After 72 hours of culture, cells were pulsed for 16 hours with 1 µCi per well [3H]-thymidine (Amersham Biosciences, Wien, Austria), harvested and counted in a scintillation counter.

Western blot analysis. Cells were directly extracted in lysis buffer (2.5% sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) 0.625 mol/l Tris–HCl pH = 6.8, 1% β-mercaptoethanol, deionized water) and proteins quantified using Bicinchoninic Acid Protein Assay Kit (Thermo Scientific, Waltham, MA). Protein (80–100 µg) were loaded on a polyacrylamide gel (Nupage Novex 4–12% Bis–Tris Gel; Invitrogen), blotted to nitrocellulose paper (Hybond ECL; Amersham), blocked for 2 hours in 0.05% Tween20 5% dry milk, incubated with rabbit polyclonal anti-nuclear factor I A (ab11988; Abcam, Cambridge, MA) or mouse monoclonal anti-GAPDH (Sigma), washed and developed with ECL Western Blotting Detection Reagent (GE Healthcare, Little Chalfont, UK).

PCR analysis. Genomic DNA was extracted from cells 10 days after transduction using Maxwell Cell DNA Purification Kit (Promega, Madison, WI) according to manufacturer's instructions. We quantified vector copies per genome by RT-qPCR using ~200 ng of template DNA. We used primers (HIV forward (Fw): 5′-TACTGACGCTCTCGCACC-3′; HIV reverse (Rv): 5′-TCTCGACGCAGGACTCG-3′), and probe (FAM 5′-ATCTCTCTCCTTCTAGCCTC-3′) against the primer binding site region for the LV and primer/probe set against the human telomerase gene (Telo Fw: 5′-GGCACACGTGGCTTTTCG-3′; Telo Rv: 5′-GGTGAACCTCGTAAGTTTATGCAA-3′; TAMRA-Probe: 5′-TCAG GACGTCGAGTGGACACGGTG-3′) or the murine β-actin gene (β- Act Fw: 5′-AGAGGGAAATCGTGCGTGAC-3′; β-Act Rv: 5′-CAATAG TGATGACCTGGCCGT-3′; VIC-probe 5′-CACTGCCGCATCCTCTTC CTCCC-3′) to quantify endogenous DNA amount used for each reaction. Copies per genome were calculated using the equation: [(ng of LV)/(ng of endogenous DNA)] × (number of LV integrations in the standard curve). The standard curve was generated by using DNA extracted from a human CEM cell line or transgenic mice carrying 4 or 8 LV copies, respectively, as previously determined by Southern blot analysis.

PCR for miR retention was performed as follows: intron Fw: 5′-TTGCGTGAGCGGAAAGATGG-3′; ΔLNGFR Rv: 5′-ACCCCCAGAA GCAGCAACAGC-3′.

To assess the ratio between spliced and unspliced transcripts of intronic LV, total RNA was extracted (RNeasy Mini kit; Qiagen, Hilden, Germany) from cells 10 days after transduction with vectors delivering amiR (LV.223.siTie2, LV.155.siTie2, LV.223.siLuc, LV.155siTie2.223siTie2) or no-miR. Similar amounts of RNA for each sample were retrotranscribed with SuperScript III (Invitrogen). RT-qPCR analyses were performed with both SyberGreen and TaqMan-based qPCR assay. Syber primers were designed with Primer3 (http://frodo.wi.mit.edu/primer3/input.htm) to perform a mutually exclusive qPCR for spliced and unspliced transcript forms: intron Fw: 5′-TGGAATTTGCCCTTTTTGAG-3′; exon Fw: 5′-GTTTGCCGCCAGAACACA-3′; common ΔLNGFR Rv: 5′-CCAGAA GCAGCAACAGCAG-3′ (Primm, Milan, Italy). Two different TaqMan assays specific for each transcript form were used: intron Fw: 5′-GCCTCAGACAGTGGTTCAAAGTTT-3′, intron Rv: 5′-CCGCGGTA CCGTCGAT-3′, FAM-probe 5′-CTCACGACACCTGAAATG-3′ MGB, and the human NGFR TaqMan assay (inventoried; Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA).

qPCR were carried out in triplicate in an ABI Prism 7900 HT Sequence Detection System (Applied Biosystems) and analyzed using the SDS 2.2.1 software. The same threshold was used to calculate the Ct values for each PCR reaction. The spliced/unspliced ratio was calculated as 2ΔCt, where ΔCt is the difference between the average Ct of spliced and unspliced transcript forms. For SyberGreen primers a dissociation curve was performed to exclude wells with aspecific amplification.

For murine Tie2 mRNA analysis, RT-qPCR analyses were performed with TaqMan probes) both for murine Tie2 and Gapdh (inventoried; Applied Biosystems), the latter used as normalizer for RNA amount used for each reaction. RT-qPCR were carried out as described above and analyzed using the SDS 2.2.1 software (ΔΔ Ct method).

microRNA analysis. Small RNAs were extracted from cells 10 days after transduction by mirVana miR Isolation Kit following manufacturer instructions (Ambion, Austin, TX). For analysis of miR expression, the Applied Biosystems Taqman microRNA Assay system was used49 and absolute copy number was determined by a standard curve generated using a purified RNA oligonucleotide corresponding to Let-7a (Primm).31 To evaluate the amplification efficiency of the different miR TaqMan assays used in our study, we performed RT-qPCR using serial dilutions of a panel of synthetic RNA oligonucleotides (mirVana miRNA Reference Panel, Applied Biosystems). We obtained similar amplification efficiency for let-7a, miR16, miR30-3p, miR30-5p, miR142-3p, miR142-5p and miR223 standards (1.95 < E < 1.97). We confirmed similar amplification efficiency (between 1.9 and 2) in all our qPCR analyses using a web program (http://miner.ewindup.info/miner/; ref. 50) which allows efficiency calculation based on the kinetics of individual reactions. Reactions were carried out in duplicate or triplicate in an ABI Prism 7900 HT Sequence Detection System (Applied Biosystems). The SDS 2.2.1 software was used to analyze the data.

For northern blot analysis, 500 µg of small RNA per sample were run on a 10% TBE-urea gel (Invitrogen), transferred by electroblotting onto Hybond-N+ membrane (Amersham Biosciences), and UV crosslinked. Hybridization was performed with terminally 32P-labeled DNA oligos (mirVana Probe and Marker Kit, Applied Biosystems) in PerfectHyb Plus (Sigma). Probes were as follows: miR 30-3p, 5′-GCTGCAAACATCCGACTGAAAG-3′; miR 30-5p, 5′-CTTCCAGTCGAGGATGTTTACA-3′. Membrane was washed with 6× SSPE (Invitrogen) and exposed in Hypercassette (Amersham Biosciences). For reprobing, blot was stripped with 0.1% SDS (GIBCO) boiling water.

Flow cytometry. Transduced cells were grown for at least 1 week after each transduction to reach steady state expression before FACS analysis and were treated as previously described.48 For immunostaining, 105 cells were blocked in phosphate buffered saline 2% fetal bovine serum and 5% human serum for 10 minutes at 4 °C, stained for 20 minutes at 4 °C with the following directly conjugated antibody: anti-ΔLNGFR conjugated with antigen presenting cells- or phycoerythrin- (anti-CD271 antibody, Miltenyi Biotec or BD Pharmingen, San Diego, CA, respectively), phycoerythrin-anti-mTie2, and phycoerythrin-IgG1 isotype control (eBioscience, San Diego, CA), FITC-anti-CD4 (BD Pharmingen), phycoerythrin-anti-CD25 (BD Pharmingen), washed, stained with 10 ng/ml of 7-aminoactinomycin D (Sigma), and analyzed by three-color flow cytometry. Nuclear expression of FOXP3 was determined by staining with clone 259D (Biolegend, San Diego, CA) conjugated to Alexa 488, following cell permeabilization according to the manufacturers' instructions. At least 10,000 viable cells were acquired for each sample. BD FACSCanto II or BD FACSCalibur Flow Cytometer (BD Pharmingen) were used for acquisition and FCS Express 3 (De Novo Software, Los Angeles, CA) for analysis.

Supplementary MaterialFigure S1. Expression and activity of LV.223 in different cell types. The indicated cell lines were transduced with the GFP.223T reporter LV and, after one week, with high and low MOI (left and right histograms, respectively) of the indicated LV.miR and no miR vectors. Cells were analyzed by FACS at 7 days after transduction as in Figure 1 of the main text. FACS histograms show GFP expression of the ΔLNGFR+ cells. GFP MFI is indicated. Untreated cells – without GFP reporter – are shown for reference. Results shown are from one of two independent experiments performed on different batches of reporter cells and at ≥3 MOI with similar results.

Supplementary Material

Expression and activity of LV.223 in different cell types. The indicated cell lines were transduced with the GFP.223T reporter LV and, after one week, with high and low MOI (left and right histograms, respectively) of the indicated LV.miR and no miR vectors. Cells were analyzed by FACS at 7 days after transduction as in Figure 1 of the main text. FACS histograms show GFP expression of the ΔLNGFR+ cells. GFP MFI is indicated. Untreated cells – without GFP reporter – are shown for reference. Results shown are from one of two independent experiments performed on different batches of reporter cells and at ≥3 MOI with similar results.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Brian D. Brown (Mount Sinai School of Medicine, New York, NY); Gregory J. Hannon (Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory, NY), David Baltimore (Caltech, Pasadena, CA), Chan-Zeng Chen (Stanford University, Palo Alto, CA), Daniel J. Dumont (University of Toronto, Canada) for providing reagents, Michele De Palma for generating the PGK-Tie2 LV, Michael H. Malim (Kings College, London, UK) for fruitful advices, Fabrizio Benedicenti, Lucia Sergi Sergi, Giulia Schira and Grazia Andolfi for technical help. This work was supported by Telethon (TIGET grant), EU (LSHB-CT-2004-005276, RIGHT) and Associazione Italiana per la Ricerca sul Cancro (AIRC) grants to L.N., and Novartis funds to L.N. and R.B. B.G. is the recipient of a research fellowship from the German Research Foundation (DFG Forschungsstipendium). The authors declare that they have no competing financial interests.

REFERENCES

- Chang K, Elledge SJ., and , Hannon GJ. Lessons from nature: microRNA-based shRNA libraries. Nat Methods. 2006;3:707–714. doi: 10.1038/nmeth923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim DH., and , Rossi JJ. Strategies for silencing human disease using RNA interference. Nat Rev Genet. 2007;8:173–184. doi: 10.1038/nrg2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bartel DP. MicroRNAs: genomics, biogenesis, mechanism, and function. Cell. 2004;116:281–297. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(04)00045-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eulalio A, Huntzinger E., and , Izaurralde E. Getting to the root of miRNA-mediated gene silencing. Cell. 2008;132:9–14. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.12.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elbashir SM, Harborth J, Lendeckel W, Yalcin A, Weber K., and , Tuschl T. Duplexes of 21-nucleotide RNAs mediate RNA interference in cultured mammalian cells. Nature. 2001;411:494–498. doi: 10.1038/35078107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grimm D, Streetz KL, Jopling CL, Storm TA, Pandey K, Davis CR, et al. Fatality in mice due to oversaturation of cellular microRNA/short hairpin RNA pathways. Nature. 2006;441:537–541. doi: 10.1038/nature04791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li L, Lin X, Khvorova A, Fesik SW., and , Shen Y. Defining the optimal parameters for hairpin-based knockdown constructs. RNA. 2007;13:1765–1774. doi: 10.1261/rna.599107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boudreau RL, Monteys AM., and , Davidson BL. Minimizing variables among hairpin-based RNAi vectors reveals the potency of shRNAs. RNA. 2008;14:1834–1844. doi: 10.1261/rna.1062908. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McBride JL, Boudreau RL, Harper SQ, Staber PD, Monteys AM, Martins I, et al. Artificial miRNAs mitigate shRNA-mediated toxicity in the brain: implications for the therapeutic development of RNAi. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105:5868–5873. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0801775105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giering JC, Grimm D, Storm TA., and , Kay MA. Expression of shRNA from a tissue-specific pol II promoter is an effective and safe RNAi therapeutic. Mol Ther. 2008;16:1630–1636. doi: 10.1038/mt.2008.144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kleinman ME, Yamada K, Takeda A, Chandrasekaran V, Nozaki M, Baffi JZ, et al. Sequence- and target-independent angiogenesis suppression by siRNA via TLR3. Nature. 2008;452:591–597. doi: 10.1038/nature06765. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ter Brake O, Legrand N, von Eije KJ, Centlivre M, Spits H, Weijer K, et al. Evaluation of safety and efficacy of RNAi against HIV-1 in the human immune system (Rag-2−/−γc−/−) mouse model. Gene Ther. 2009;16:148–153. doi: 10.1038/gt.2008.124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brummelkamp TR, Bernards R., and , Agami R. A system for stable expression of short interfering RNAs in mammalian cells. Science. 2002;296:550–553. doi: 10.1126/science.1068999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szulc J, Wiznerowicz M, Sauvain MO, Trono D., and , Aebischer P. A versatile tool for conditional gene expression and knockdown. Nat Methods. 2006;3:109–116. doi: 10.1038/nmeth846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castanotto D, Sakurai K, Lingeman R, Li H, Shively L, Aagaard L, et al. Combinatorial delivery of small interfering RNAs reduces RNAi efficacy by selective incorporation into RISC. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007;35:5154–5164. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkm543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeng Y, Wagner EJ., and , Cullen BR. Both natural and designed micro RNAs can inhibit the expression of cognate mRNAs when expressed in human cells. Mol Cell. 2002;9:1327–1333. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(02)00541-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chung KH, Hart CC, Al-Bassam S, Avery A, Taylor J, Patel PD, et al. Polycistronic RNA polymerase II expression vectors for RNA interference based on BIC/miR-155. Nucleic Acids Res. 34:e53. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkl143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu YP, Haasnoot J, ter Brake O, Berkhout B., and , Konstantinova P. Inhibition of HIV-1 by multiple siRNAs expressed from a single microRNA polycistron. Nucleic Acids Res. 2008;36:2811–2824. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkn109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aagaard LA, Zhang J, von Eije KJ, Li H, Saetrom P, Amarzguioui M, et al. Engineering and optimization of the miR-106b cluster for ectopic expression of multiplexed anti-HIV RNAs. Gene Ther. 2008;15:1536–1549. doi: 10.1038/gt.2008.147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ely A, Naidoo T, Mufamadi S, Crowther C., and , Arbuthnot P. Expressed anti-HBV primary microRNA shuttles inhibit viral replication efficiently in vitro and in vivo. Mol Ther. 2008;16:1105–1112. doi: 10.1038/mt.2008.82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stegmeier F, Hu G, Rickles RJ, Hannon GJ., and , Elledge SJ. A lentiviral microRNA-based system for single-copy polymerase II-regulated RNA interference in mammalian cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102:13212–13217. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0506306102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Du G, Yonekubo J, Zeng Y, Osisami M., and , Frohman MA. Design of expression vectors for RNA interference based on miRNAs and RNA splicing. FEBS J. 2006;273:5421–5427. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2006.05534.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xia XG, Zhou H, Samper E, Melov S., and , Xu Z. Pol II-expressed shRNA knocks down Sod2 gene expression and causes phenotypes of the gene knockout in mice. PLoS Genet. 2006;2:e10. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.0020010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greber D., and , Fussenegger M. Multi-gene engineering: simultaneous expression and knockdown of six genes off a single platform. Biotechnol Bioeng. 2007;96:821–834. doi: 10.1002/bit.21303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stern P, Astrof S, Erkeland SJ, Schustak J, Sharp PA., and , Hynes RO. A system for Cre-regulated RNA interference in vivo. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105:13895–13900. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0806907105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qiu L, Wang H, Xia X, Zhou H., and , Xu Z. A construct with fluorescent indicators for conditional expression of miRNA. BMC Biotechnol. 2008;8:77. doi: 10.1186/1472-6750-8-77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Snyder LL, Esser JM, Pachuk CJ., and , Steel LF. Vector design for liver-specific expression of multiple interfering RNAs that target hepatitis B virus transcripts. Antiviral Res. 2008;80:36–44. doi: 10.1016/j.antiviral.2008.04.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naldini L, Blomer U, Gallay P, Ory D, Mulligan R, Gage FH, et al. In vivo gene delivery and stable transduction of nondividing cells by a lentiviral vector. Science. 1996;272:263–267. doi: 10.1126/science.272.5259.263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Follenzi A, Ailles LE, Bakovic S, Geuna M., and , Naldini L. Gene transfer by lentiviral vectors is limited by nuclear translocation and rescued by HIV-1 pol sequences. Nat Genet. 2000;25:217–222. doi: 10.1038/76095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang Q., and , Bluestone JA. The Foxp3+ regulatory T cell: a jack of all trades, master of regulation. Nat Immunol. 2008;9:239–244. doi: 10.1038/ni1572. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown BD, Gentner B, Cantore A, Colleoni S, Amendola M, Zingale A, et al. Endogenous microRNA can be broadly exploited to regulate transgene expression according to tissue, lineage and differentiation state. Nat Biotechnol. 2007;25:1457–1467. doi: 10.1038/nbt1372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown BD, Venneri MA, Zingale A, Sergi Sergi L., and , Naldini L. Endogenous microRNA regulation suppresses transgene expression in hematopoietic lineages and enables stable gene transfer. Nat Med. 2006;12:585–591. doi: 10.1038/nm1398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fazi F, Rosa A, Fatica A, Gelmetti V, De Marchis ML, Nervi C, et al. A minicircuitry comprised of microRNA-223 and transcription factors NFI-A and C/EBPalpha regulates human granulopoiesis. Cell. 2005;123:819–831. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.09.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vigna E, Amendola M, Benedicenti F, Simmons AD, Follenzi A., and , Naldini L. Efficient Tet-dependent expression of human factor IX in vivo by a new self-regulating lentiviral vector. Mol Ther. 2005;11:763–775. doi: 10.1016/j.ymthe.2004.11.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones N, Iljin K, Dumont DJ., and , Alitalo K. Tie receptors: new modulators of angiogenic and lymphangiogenic responses. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2001;2:257–267. doi: 10.1038/35067005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michlewski G, Guil S, Semple CA., and , Caceres JF. Posttranscriptional regulation of miRNAs harboring conserved terminal loops. Mol Cell. 2008;32:383–393. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2008.10.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu G, Min H, Yue S., and , Chen CZ. Pre-miRNA loop nucleotides control the distinct activities of mir-181a-1 and mir-181c in early T cell development. PLoS ONE. 2008;3:e3592. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0003592. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ossowski S, Schwab R., and , Weigel D. Gene silencing in plants using artificial microRNAs and other small RNAs. Plant J. 2008;53:674–690. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2007.03328.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu X, Santat LA, Chang MS, Liu J, Zavzavadjian JR, Wall EA, et al. A versatile approach to multiple gene RNA interference using microRNA-based short hairpin RNAs. BMC Mol Biol. 2007;8:98. doi: 10.1186/1471-2199-8-98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramezani A, Hawley TS., and , Hawley RG. Lentiviral vectors for enhanced gene expression in human hematopoietic cells. Mol Ther. 2000;2:458–469. doi: 10.1006/mthe.2000.0190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bohne J, Wodrich H., and , Krausslich HG. Splicing of human immunodeficiency virus RNA is position-dependent suggesting sequential removal of introns from the 5′ end. Nucleic Acids Res. 2005;33:825–837. doi: 10.1093/nar/gki185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dull T, Zufferey R, Kelly M, Mandel RJ, Nguyen M, Trono D, et al. A third-generation lentivirus vector with a conditional packaging system. J Virol. 1998;72:8463–8471. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.11.8463-8471.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berget SM. Exon recognition in vertebrate splicing. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:2411–2414. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.6.2411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pawlicki JM., and , Steitz JA. Primary microRNA transcript retention at sites of transcription leads to enhanced microRNA production. J Cell Biol. 2008;182:61–76. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200803111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ter Brake O, t Hooft K, Liu YP, Centlivre M, von Eije KJ., and , Berkhout B. Lentiviral vector design for multiple shRNA expression and durable HIV-1 inhibition. Mol Ther. 2008;16:557–564. doi: 10.1038/sj.mt.6300382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allan SE, Alstad AN, Merindol N, Crellin NK, Amendola M, Bacchetta R, et al. Generation of potent and stable human CD4+ T regulatory cells by activation-independent expression of FOXP3. Mol Ther. 2008;16:194–202. doi: 10.1038/sj.mt.6300341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salmon P, Kindler V, Ducrey O, Chapuis B, Zubler RH., and , Trono D. High-level transgene expression in human hematopoietic progenitors and differentiated blood lineages after transduction with improved lentiviral vectors. Blood. 2000;96:3392–3398. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amendola M, Venneri MA, Biffi A, Vigna E., and , Naldini L. Coordinate dual-gene transgenesis by lentiviral vectors carrying synthetic bidirectional promoters. Nat Biotechnol. 2005;23:108–116. doi: 10.1038/nbt1049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen C, Ridzon DA, Broomer AJ, Zhou Z, Lee DH, Nguyen JT, et al. Real-time quantification of microRNAs by stem-loop RT-PCR. Nucleic Acids Res. 2005;33:e179. doi: 10.1093/nar/gni178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao S., and , Fernald RD. Comprehensive algorithm for quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction. J Comput Biol. 2005;12:1047–1064. doi: 10.1089/cmb.2005.12.1047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Expression and activity of LV.223 in different cell types. The indicated cell lines were transduced with the GFP.223T reporter LV and, after one week, with high and low MOI (left and right histograms, respectively) of the indicated LV.miR and no miR vectors. Cells were analyzed by FACS at 7 days after transduction as in Figure 1 of the main text. FACS histograms show GFP expression of the ΔLNGFR+ cells. GFP MFI is indicated. Untreated cells – without GFP reporter – are shown for reference. Results shown are from one of two independent experiments performed on different batches of reporter cells and at ≥3 MOI with similar results.