Abstract

Duchenne muscular dystrophy (DMD), one of the most severe neuromuscular disorders of childhood, is caused by the absence of a functional dystrophin. Antisense oligomer (AO) induced exon skipping is being investigated to restore functional dystrophin expression in models of muscular dystrophy and DMD patients. One of the major challenges will be in the development of clinically relevant oligomers and exon skipping strategies to address many different mutations. Various models, including cell-free extracts, cells transfected with artificial constructs, or mice with a human transgene, have been proposed as tools to facilitate oligomer design. Despite strong sequence homology between the human and mouse dystrophin genes, directing an oligomer to the same motifs in both species does not always induce comparable exon skipping. We report substantially different levels of exon skipping induced in normal and dystrophic human myogenic cell lines and propose that animal models or artificial assay systems useful in initial studies may be of limited relevance in designing the most efficient compounds to induce targeted skipping of human dystrophin exons for therapeutic outcomes.

Introduction

Duchenne muscular dystrophy (DMD), one of the most severe neuromuscular disorders of childhood, is caused by the absence of a functional dystrophin,1 with patients suffering from progressive muscle weakness and severe respiratory and cardiac complications by the second and third decades of life.2,3 Becker muscular dystrophy also arises from mutations in dystrophin, but these lesions are such that some functional protein can be generated, albeit of reduced quantity and/or quality.

Splice intervention using antisense oligomers (AOs) is being developed as a potential molecular therapy for DMD. AO intervention during dystrophin pre-mRNA processing aims to exclude one or more exons associated with the primary DMD-causing mutation, while maintaining or restoring the dystrophin mRNA reading frame. A clinical trial of AO-induced exon skipping in DMD patients has demonstrated proof of principle that this antisense strategy can restore some dystrophin expression in DMD muscle.4

One of the major challenges to oligomer-induced gene transcript manipulation for therapeutic purposes will be in the design and development of clinically relevant oligomers. Various models, including cell-free extracts, cells transfected with artificial constructs, mice with a human transgene, and in silico predictions, have been proposed as tools to facilitate oligomer design for splice manipulation.5,6,7 The highly coordinated nature of gene expression leads to reduced efficiency of processing when cell-free extracts are used to assay splicing. Within a nucleus, introns are removed an estimated 40 times faster than in vitro processing of synthetic pre-mRNA transcripts.8 Normal gene expression appears precariously balanced when one considers minor base changes can lead to activation of cryptic splice sites, pseudoexon inclusion, or some other form of aberrant splicing.9,10 Hence, insertion of any test exon with some arbitrarily selected flanking intronic sequences into a splice reporter system may allow some assessment of oligomer-induced redirection of splicing patterns in transfected cells. However, such a system will not directly reflect processing of that exon when it is under control of the full complement of tissue specific cis- and trans-splicing motifs and factors. Finally, transcription-coupled processing differs from uncoupled processing in that the nascent pre-mRNA is a growing strand that is constantly folding into new structures and associating with protein–RNA and protein–protein complexes within the “mRNA factory.”11

We consider normal human myogenic cells appropriate for AO design and optimization, and reported an initial draft of AOs targeting human dystrophin exons 2–78.12 Despite strong homology between mouse and human dystrophin, we found variation in exon skipping efficiency and patterns of exon removal in these transcripts. For some exons, directing oligomers to the same target motifs induced similar exon skipping patterns. In contrast, oligomers targeting other exons generated different dystrophin splice isoforms in the two species. We report substantially different levels of exon skipping induced in normal and dystrophic human myogenic cell lines, and propose that animal models or artificial assay systems, useful in some studies, may be of limited relevance in designing the most efficient compounds to induce targeted skipping of human dystrophin exons.

Results

Splice site and auxiliary motif predictions

Acceptor and donor splice site scores for exons under investigation, as calculated by the web-based program, MaxEntScan are shown in Table 1, along with details of exon and flanking intron lengths. Although there was some variation in the mean donor splice site strength of those exons under investigation, there was no obvious trend where strong or weak donor splice sites were found to be more responsive as targets for splice intervention. Similarly, the score for the acceptor splice sites did not offer any indication as to the suitability of the sites for AO-induced exon skipping. It is of interest that the mouse dystrophin exon 23 acceptor splice site, predicted to be very weak, has previously been shown to be unresponsive as a target for exon removal.13

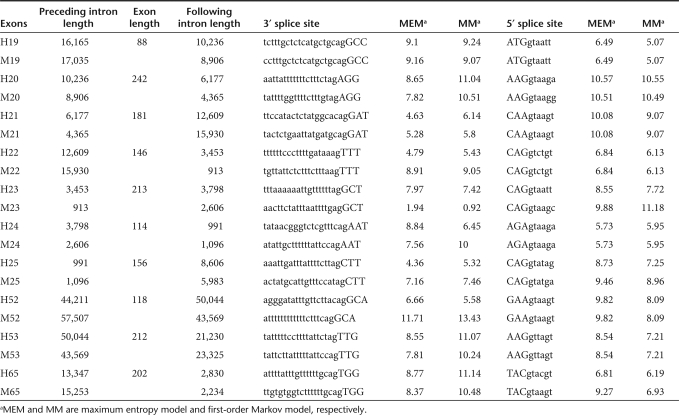

Table 1.

Predicted acceptor and donor splice site scores showing length of exon and flanking introns

Exons and limited flanking intronic sequences were analyzed for exonic splice enhancers (ESEs), using two programs: ESEfinder 3.0 predicts motifs responsive to the human SR proteins SF2/ASF, SC35, SRp40, or SRp55,14,15 and RESCUE-ESE allows identification of putative ESEs for human and mouse.16,17 AO sequences designed to excise selected exons, and predicted ESEs, within these annealing sites are described in Table 2. The distribution of splice motifs predicted by RESCUE-ESE, relative AO annealing, and induced exon skipping patterns for both human and mouse dystrophin exons under investigation are shown in Figure 1a–e. The most effective AOs appear to preferentially target predicted SF2/ASF (IgM-BRCA1) (25%) or SC35 (28%) motifs, compared to 22, 17, and 8% targeting SF2/ASF, SRp40, and SRp55, respectively. These percentages are calculated from the number of ESE motifs, either completely or partially occurring within the oligomer annealing site, divided by the total number of ESE motifs within the target exons.

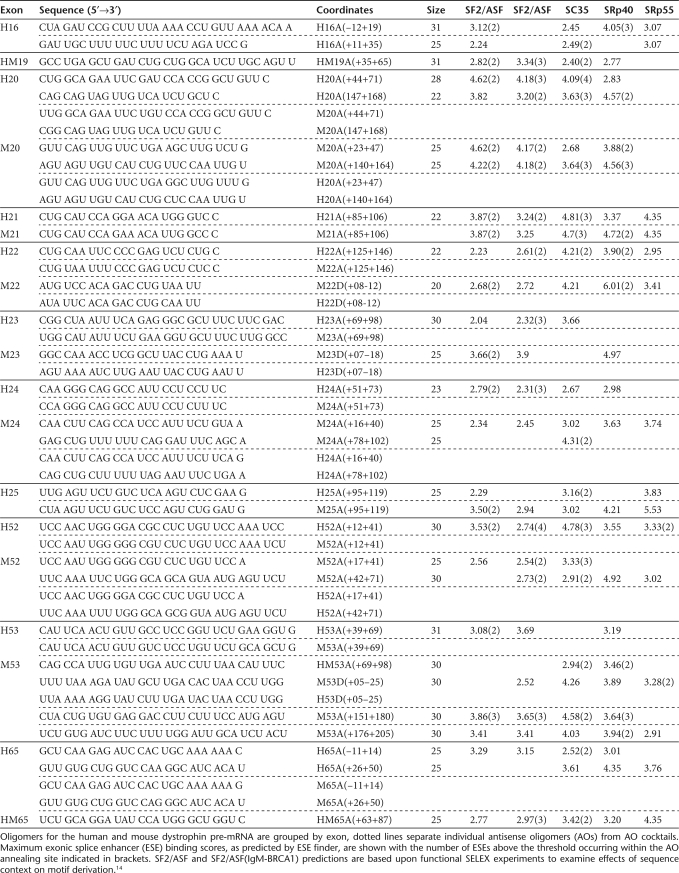

Table 2.

Nucleotide sequences of oligomers designed and evaluated for exon skipping potential

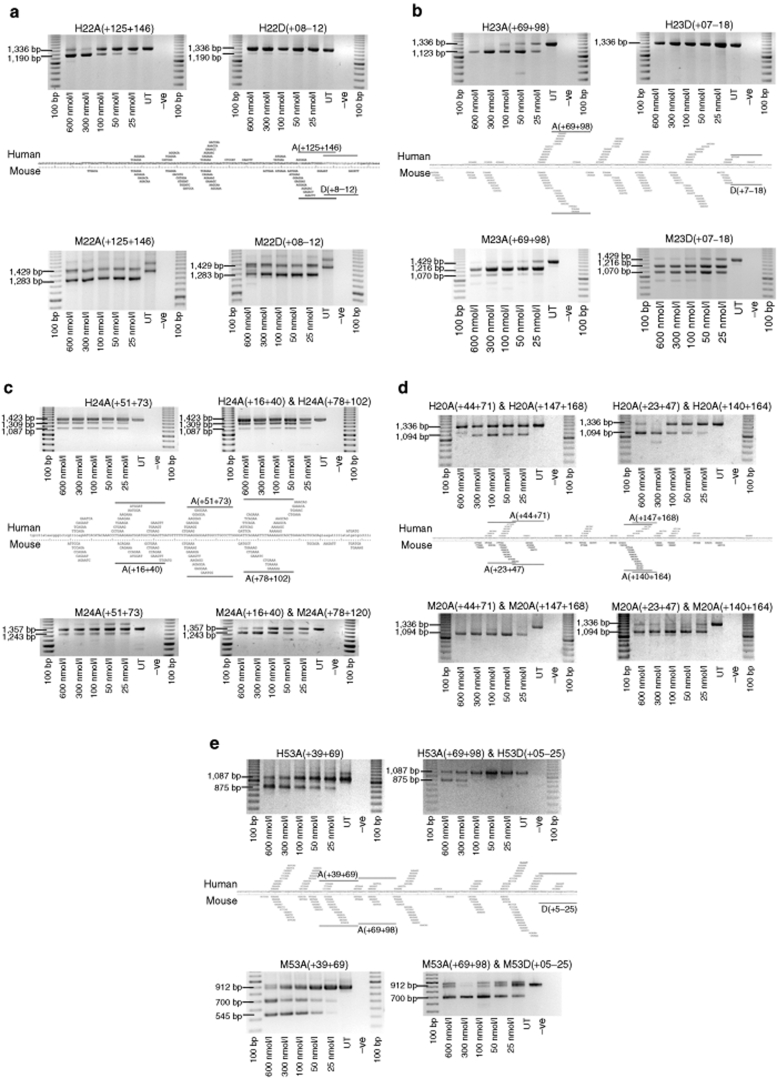

Figure 1.

Comparison of exon skipping induced in human and mouse myogenic cells. Patterns of dystrophin exon skipping induced by antisense oligomers (AOs) targeting 5 exons [(a) 22; (b) 23; (c) 24; (d) 20; (e) 53] after transfection into normal human and mdx mouse myogenic cells. Annealing coordinates relative to predicted exonic splice enhancers are shown, as are the sizes of full-length and induced transcript products. UT, Lipo, or L2K refer to untreated cells, or cells treated with Lipofectin, or Lipofectamine 2000, respectively.

AO design and evaluation

A direct comparison of relative AO-induced skipping of the same exon in immortalized mdx mouse and human myogenic cells was undertaken to establish, if annealing coordinates for one species could be directly applied to the other. Immortalized mdx cells were assessed as removal of exon 23 would bypass the nonsense mutation, and exon 23 skipped transcripts would no longer be subjected to nonsense-mediated decay, unlike the intact, full-length transcript. Removal of other exons from the mdx dystrophin gene transcript would not remove the premature stop codon, hence both full-length and skipped transcripts should be subjected to equal rates of nonsense-mediated decay. Exclusion of selected exons from the normal dystrophin gene transcript will, in many cases, disrupt the reading frame and render the induced transcript subject to nonsense-mediated decay. In most experiments, dose responses of exon skipping with varying oligomer concentration were used to rank oligomer efficiency for that exon. A comprehensive series of AOs has been developed to excise each exon from the human dystrophin gene transcript.12,18,19 Oligomer-induced exon skipping of several mouse dystrophin exons has been examined in normal and dystrophic mice, and is an on-going process of refinement.20,21

In 3 of 10 exons under investigation, optimal annealing coordinates for induction of exon skipping were identical in human and mouse, indicating that transfer of AO design between human and mouse dystrophin exons 19, 21, and 25 was possible (data not shown). As shown in Table 1, the calculated acceptor splice site scores for exon 19 was high (9.07–9.24), while the donor splice site scores were moderate (5.07–6.49). In contrast, the scores for exon 21 acceptor (4.63–6.14) were much weaker than the donor (9.07–10.08), whereas the acceptor and donor site scores of exon 25 were of intermediate values (4.36–7.46 and 7.25–9.46, respectively).

Exons 19, 21, and 25 were removed by single AOs, as were exons 22 and 23, although in the latter cases there were substantial differences in exon skipping efficiency and splicing patterns between the species. For both mouse exons 22 and 23, the donor splice sites were originally identified as amenable targets for exon excision, however, when these coordinates were targeted in the human dystrophin pre-mRNA, there was no detectable exon skipping (Figure 1a,b). Targeting intraexonic motifs in human dystrophin exons 22 and 23 induced substantial exon skipping, and directing AOs to these coordinates in the mouse dystrophin pre-mRNA also resulted in efficient exon excision. Indeed, it would appear that directing an oligomer to the corresponding mouse intraexonic motif identified in human dystrophin exon 22 was equally effective at excising the target exon, as the oligomer annealing to the donor splice site. The induced splicing patterns for exon 23 also differed between human and mouse, in that when human exon 23 removal was specific (1,216 bp), transcripts missing exons 22 and 23 (1,070 bp) were readily detected in the treated mouse cells, in addition to specific exon 23 skipping. This dual exon skipping was more pronounced when the mouse exon 23 donor site was targeted, and it would appear that directing an oligomer to the intraexonic motif may result in more specific exon 23 skipping.

Human exon 24 could be excised with a single AO, H24A(+51+73) (1,309 bp), but reverse transcription–PCR (RT-PCR) also revealed the presence of transcripts missing exons 24+25 (1,087 bp). Targeting the equivalent mouse coordinates resulted in lower levels of exon 24 skipping in an apparent nondose-dependant manner. More efficient and specific mouse exon 24 skipping was induced using a combination of two AOs. The application of an AO cocktail targeting the equivalent coordinates induced skipping of human exon 24, but transcripts missing exon 24 and 25 were still evident (Figure 1c).

Two of the 10 human exons (20 and 65)22 and 4 of the 10 mouse exons (20, 24,21 52, and 5320) were only efficiently dislodged by the application of combinations of AOs. There was partial overlap in AO annealing coordinates for the cocktails that excised exon 20 from both the human [H20A(+44+71) and H20A(+147+168)] and mouse [(M20A(+23+47) and M20A(+140+164)] dystrophin gene transcripts (Table 2).12,21,22 The human and mouse AO cocktails appeared equally efficient when used in mice, but when the optimal mouse coordinates were directed to the human dystrophin pre-mRNA, there was a slight, but reproducible decline in efficiency of exon removal, most noticeable at lower transfection concentrations (Figure 1d).

A single AO, H52A(+12+41), was found to efficiently remove human exon 52 from the mature dystrophin transcript, with >30% exon skipping being induced after transfection at 100 nmol/l.12 Directing an oligomer to the corresponding mouse coordinates induced substantial exon skipping, but the application of the cocktail M52A(+17+41) and M52A(+42+71) resulted in two- to threefold more exon exclusion (Supplementary Figure S1).

Directing AOs to human and mouse dystrophin exons 53 resulted in the generation of the most distinct patterns of exon excision observed to date. A single AO, H53A(+39+69), was able to induce efficient and specific exon skipping from the human dystrophin gene transcript (Figure 1e). Upon targeting the same coordinates in the mouse dystrophin pre-mRNA, some transcripts missing exon 53 (700 bp) were detected, as well as a substantial proportion of transcripts missing both exons 53 and 54 (545 bp). The shorter transcript is out-of-frame and was never detected after transfecting human cells with this AO or any of the other 18 AOs, designed to excise human exon 53.20 Specific mouse exon 53 skipping could be induced using a combination of two mouse-specific AOs (Figure 1e). However, when the same annealing coordinates were targeted in the human dystrophin gene transcript, only low levels of exon 53 skipping were detected (Figure 1e).

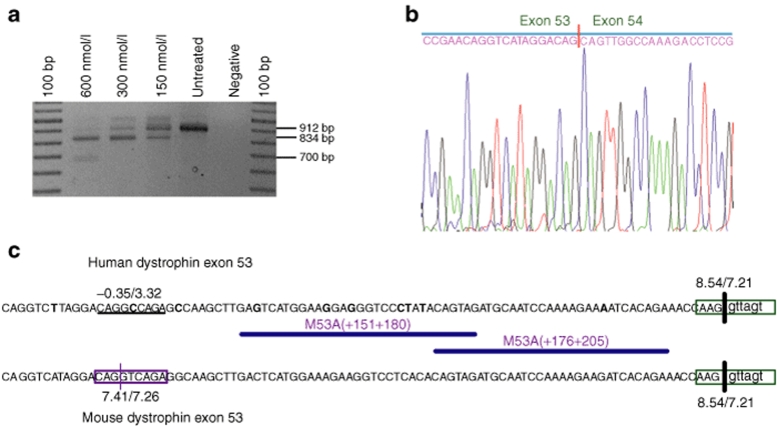

Two additional AOs, [M53A(+151+180) and M53A(+176+ 205)], with overlapping annealing sites, were found to induce cryptic splicing in mouse exon 53, which led to the loss of 78 bases of coding sequence from 3′ end of the exon (Figure 2a). The activated mouse cryptic donor splice site was identified by DNA sequencing (Figure 2b), and calculated to have a splice site score of 7.41/7.26 (Figure 2c). Directing oligomers to this region of the human gene transcript resulted in low levels of inconsistent exon 53 skipping, with no evidence of cryptic splice site activation (data not shown).

Figure 2.

Antisense oligomer (AO)-induced cryptic splicing of mouse dystrophin exon 53. (a) Dystrophin transcript products in AO-treated mdx cultures; (b) nucleotide sequences at the novel junction arising from activation of the exon 53 cryptic donor splice site identified by DNA sequencing; (c) partial sequence of human and mouse dystrophin exon 53 showing mouse cryptic donor splice site and AO annealing coordinates. Differences in nucleotide sequences are indicated in bold type.

Human dystrophin exon 65 could only be efficiently removed using a combination of two AOs,22 whereas AOs, M65A(−11+14) and M65A(+26+50), annealing to the same coordinates as the human cocktail components were able to induce robust exon skipping from the mouse dystrophin pre-mRNA, after transfection at concentrations of 300 nmol/l, but efficiency declined at lower concentrations (Supplementary Figure S2). Another oligomer targeting mouse exon 65, M65A(+63+87) (shown in Table 2), was found to induce more robust exon skipping (Supplementary Figure S2). However, directing an oligomer to the corresponding coordinates in the human dystrophin pre-mRNA did not induce skipping of the target exon, when applied individually.22

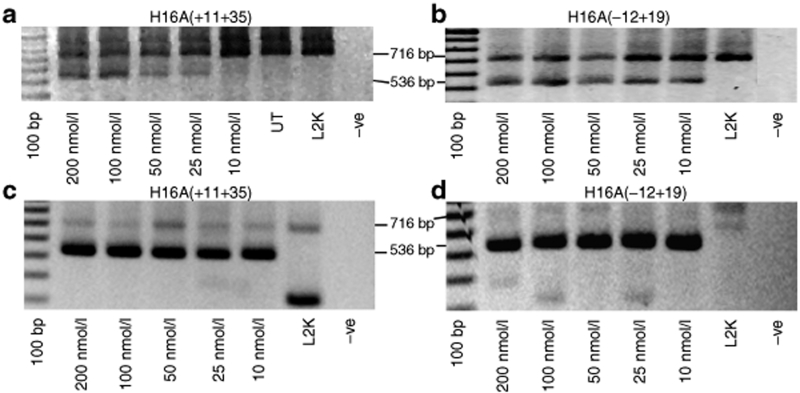

Induced exon 16 skipping in normal and dystrophic human myogenic cells

Two AOs, H16A(−12+19)12,23 and H16A(+11+35),23 previously designed to excise exon 16 from the mature human dystrophin mRNA, could be readily distinguished in their ability to excise the target exon (Figure 3a,b). H16A(−12+19), targeting the exon 16 acceptor site could induce pronounced exon excision at a concentration of 10 nmol/l, while H16A(+11+35) induced weaker exon 16 skipping after transfection at 25 nmol/l in normal human myogenic cells. However, when these compounds were transfected into myogenic cells from a DMD patient with a G>T substitution of the first base of intron 16 (IVS16+1G>T; c.1992+1G>T), both AOs induced robust exon skipping and could not be readily discriminated (Figure 3c,d). RT-PCR on RNA extracted from the untreated DMD cells did not yield a consistent pattern, with sporadic generation of shorter than normal transcripts missing exons 13–15, 14–16, 14+16 (exon 15 present), and 16, and less abundant, near-normal, or larger than expected products. Some of the products of abnormal size were identified by DNA sequencing as having arisen from displacement of the exon 16 donor splice site by one base upstream, or pseudoexon inclusion of 89 bases from intron 16 (data not shown).

Figure 3.

Comparison of exon skipping induced in normal and patient myogenic cells. Reverse transcription–PCR analysis of two oligomers to induce exon 16 skipping in normal myogenic cells (a and b); and cells from a Duchenne muscular dystrophy patient with a mutation (IVS16+1G>T; c.1992+1G>T) in dystrophin exon 16 (c and d). UT or L2K refer to untreated cells, or cells treated with Lipofectamine 2000.

Discussion

Pre-mRNA splicing, the process of joining exons and removing intervening sequences, is tightly controlled by complex interactions between cis-elements and >150 trans-factors24,25,26,27 involved in recognition of exon boundaries and subsequent incorporation into the mature transcript. Four classical cis-elements; the 5′ and 3′ splice site, the polypyrimidine tract, and branch point are primary binding sites for snRNPs and other proteins involved in defining exon/intron boundaries. In addition to the obvious splice motifs, exon recognition and splicing also depends upon the nature, position, and combination of auxiliary splice motifs that modulate signals determining exon incorporation, presumably by recruiting trans-factors that regulate exon selection.28,29

The high degree of conservation at the ends of the introns would suggest that the acceptor and donor splice sites are obvious and preferable targets for AO-induced exon skipping. As all dystrophin exons are constitutively expressed in the predominant 427 kd skeletal muscle isoform, splice site scores are somewhat redundant, but may provide an indication of amenable targets to redirect pre-mRNA splicing. However, considering the 10 exons examined in this report, there was no obvious correlation between predicted splice site score and optimal AO target. Donor splice sites seemed to be the least preferred human targets, although these motifs were amenable targets in skipping 3 of the 10 mouse exons.

AO-induced exon skipping requires appropriately designed AOs to specifically mask motifs involved in the exon recognition and splicing process, by either rendering the single-stranded motifs double-stranded or altering the secondary structures essential for normal exon recognition and processing. Robust and consistent exon skipping is essential if oligomers are to be clinically applicable. If it is necessary to use large amounts of an oligomer to excise a target exon, this may be difficult to achieve in a clinical setting, and/or lead to nonantisense effects. Although 12 oligomers may be capable of restoring the dystrophin reading frame in DMD individuals with exon deletions in the mutation hotspots,30 it will be essential to extend this therapy to many different amenable mutations across the gene transcript.

Subtle DNA changes in dystrophin (microinsertion/deletion, nonsense, splice site mutations) represent an estimated 30% of DMD cases. These mutations cannot be ignored based only upon incidence, especially because the gene is largely intact and in most of these cases splice intervention would result in a dystrophin isoform of near-normal function. Furthermore, protein-truncating mutations in the exons encoding the rod domain could be considered most amenable to exon skipping. The majority of exons in this region are in-frame and hence removal of a nonsense mutation/microinsertion/deletion would only require excision of a single exon. In-frame deletions within this region are not commonly reported, possibly because many of these cases are not recognized due to a mild phenotype.31 Indeed, it has been reported that an individual missing exon 16 had no clinical symptoms and normal serum creatine kinase levels, a sensitive marker of muscle damage.32

The 45 AOs evaluated for both human and mouse dystrophin pre-mRNA annealed to a total of 174 predicted ESEs. SF2/ASF (IgM-BRCA) and SC35 were found to be more common targets for the optimized AO-induced skipping of these dystrophin exons, consistent with other reports.22,33 The high proportion of AOs capable of redirecting splicing supports the concept that many pre-mRNA motifs are involved in exon definition and splicing (for review see refs. 11,34,35). It is possible that the importance of some motifs in pre-mRNA processing is reflected by the levels of induced shortened transcripts. It should also be noted that no single motif is a universal optimal target. Mouse exons 22 and 23 were efficiently excised by targeting two distinct domains, the donor splice sites and intraexonic motifs, which were identified during a study of the human gene transcript. Although the human dystrophin gene transcript only responded to AOs directed at intraexonic targets for these exons, it is important that, in the event of sequence-specific effects with one compound, another oligomer may be available. In addition, if polymorphisms or disease-causing mutations compromise annealing of one oligomer, it will be necessary to have identified an alternative compound.

Although some AO coordinates appeared to be equally amenable in the two species, there were differences, some subtle and others more pronounced, that might raise questions regarding the accuracy and validity of AO design in nonhomologous or artificial systems. Directing an AO at coordinates found to efficiently excise exon 53 from the human dystrophin mRNA induced dystrophin gene transcripts missing exons 53 and 53 + 54 when applied to mouse cells. There are several cases where a single AO can excise two exons at a time, presumably reflecting closely coordinated processing.30,36,37 Targeting human exon 53 resulted in only the loss of that exon from the mature dystrophin transcript, but interestingly, directing an AO to human dystrophin exon 54 led to removal of both exons 54 + 55.12 An AO designed to excise mouse exon 54 resulted in specific removal of that targeted exon (C. Mitrpant, S. Fletcher, and S.D. Wilton, unpublished results). Although similarities in human and mouse dystrophin splice motif usage were predicted to be as high as 90% in constitutive splicing,38,39,40 differences in genetic background and splice motif usage must be considered when extrapolating transcript manipulation from one model to another.

During initial optimization studies to induce mouse exon 53 skipping, two overlapping AOs were found to activate a cryptic donor splice site in that exon, which led to the loss of 78 bases of coding sequence. The activated mouse exon 53 cryptic splice site was calculated to have a splice site score similar to the wild-type donor site. When targeting the same coordinates in the human dystrophin transcript, activation of cryptic splicing was never detected. A “T” (mouse) and “C” (human) difference allowed activation of a cryptic donor splice site only in the mouse transcript, thereby demonstrating that species-specific variation, even when not directly affecting AO annealing, can have indirect and unexpected consequences on gene expression.

We consider it important to initially optimize AO design in myogenic cells expressing a normal dystrophin gene transcript, even though protein studies are not possible. Induced exon removal from the intact dystrophin mRNA would ensure that the intervention was possible in the presence of all normal transcription and splicing cis-elements and splicing machinery, thus setting a high standard in AO design. Exonic deletions that disrupt the reading frame and lead to DMD would compromise pre-mRNA processing to some extent, because of the loss of splice motifs in the deleted region. A deletion of exon 50 and flanking intronic sequences will bring together exons 49 and 51 that should not be in direct communication in the context of normal dystrophin transcript processing. Furthermore, a normal dystrophin gene transcript would not be subjected to nonsense-mediated decay, unlike induced transcripts in which exon removal causes a frameshift.34

We previously reported optimization of AOs to excise exon 16 from the human gene transcript.23 The addition of five nucleotides to the AO was found to increase efficiency of target exon skipping by ~40-fold, more than justifying a 20% increase in the length of the oligomer. The exon 16 donor splice site mutation did not lead to a single aberrant gene transcript, but a mixture of products, including shorter in-frame transcripts that should have mitigated severity of the disease. Since the diagnosis of DMD had been confirmed clinically, it is most likely that the in-frame products represent very low abundance mRNAs that had escaped NMD and were, hence, detected by RT-PCR. A nonsense mutation in the muscle glycogen phosphorylase gene was reported to result in seven different gene transcripts generated by altered splicing.41 While it appears that the exon 16 dystrophin donor splice site mutation generated multiple disease-associated transcripts, the AO that excised exon 16 restored apparently normal levels of a single in-frame transcript.

The evidence that single base variation between mouse:human or human:human dystrophins can influence splice manipulation must cast some doubts on assays that do not assess dystrophin splicing in the appropriate environment. It is unreasonable to assume that in vitro gene expression in a monolayer of cultured myogenic cells will exactly reflect in vivo gene expression, especially considering fiber-type differences, muscle architecture, innervation, and degree of pathology in dystrophic muscle. However, dystrophin processing in cultured myogenic cells is likely to be more relevant than an artificial system examining transgene expression in a cell line transfected with a plasmid construct containing only a portion of dystrophin taken out of context. Goren et al.40 demonstrated that the same auxiliary splice motif could direct either exon inclusion or exclusion from different mini genes, depending on the location of splice motifs in the construct. When sequences flanking splice regulatory motifs are manipulated, splicing is modified.40 In such an artificial system, irrelevant intron size and sequences must be a major concern for AO design and optimization.

In summary, the design and evaluation of AOs to induce human dystrophin exon skipping should be undertaken in human myogenic cultures, whereas a study of exon excision from the mouse dystrophin gene transcript should be undertaken in murine cells. Despite strong homology between the human and mouse (and canine) dystrophin, there are many differences and some, as described in this report, influence RNA processing. When developing exon skipping strategies for nondeletion DMD patients, AOs designed according to the normal dystrophin may not be ideal. The disease-causing base change, loss, or insertion may occur at the AO annealing site and compromise its ability to excise that exon. Although it is possible that the change may alter a splice motif and enhance exon recognition and strengthen splicing, it is more probable that most changes in a gene would weaken exon recognition and splicing. Regardless of the predicted consequences of a change in dystrophin splicing, testing should be undertaken in myogenic cells, then dystrophic cells carrying the mutation under examination, and ultimately the patient.

Materials and Methods

Splice site scoring and prediction of ESEs motifs. Acceptor and donor splice site scores for all exons under analysis were determined using two different algorithms; the maximum entropy model and the first-order Markov model. Both algorithms were computed on the web-based program, MaxEntScan (http://genes.mit.edu/burgelab/maxent/Xmaxent.html), which allows the calculation of strength of both acceptor and donor splice site scores. MaxEntScan requires 20 bases upstream of the 3′ splice site and the first three bases after the acceptor to perform 3′ splice site scoring. Three bases upstream and six bases downstream of the donor splice site were included to evaluate 5′ splice site scoring.42 Exonic sequence with 25 bases of flanking intron from 10 human and mouse exons were analyzed to identify putative ESEs, using ESEsfinder3.014,15 for human exons, and human and mouse ESE motifs were predicted by RESCUE-ESE.16,17

AO synthesis, design, and nomenclature. 2′-O-methyl-modified AOs on a phosphorothioate backbone were designed to anneal to motifs predicted to be involved in pre-mRNA splicing, and synthesized in-house on and Expedite 8909 Nucleic Acid Synthesizer (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA), using the 1 µmol thioate synthesis protocol. Nomenclature was based on that described by Mann et al.,37 where the first letter designates the species (H: human, M: mouse), the number refers to the exon, the second letter indicates Acceptor or Donor Splice site and the “−” and “+” specifies intron or exon bases, respectively.

Myoblast culture and transfection. Normal and dystrophic human myogenic cells were prepared by a modification of the protocol described by Rando and Blau.43 Myogenic cells were transfected with AOs at concentrations of 25–600 nmol/l. Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen, Melbourne, Australia) and Lipofectin (Invitrogen) were employed as transfection reagents for human myogenic cells and H-2K mdx cells, respectively, as described previously.18

RNA extraction and RT-PCR analysis. RNA was harvested from the cell cultures 24 hours after transfection, using Trizol (Invitrogen), according to the manufacturer's protocol. One-step RT-PCR was undertaken, using 100 ng of total RNA as template in a 12.5 µl reaction for 30 cycles, using 1 U of Superscript III (Invitrogen). Nested PCR was carried out for 30 cycles, using AmpliTaQ Gold (Applied Biosystems, Melbourne, Australia). PCR cycling conditions were performed, as described by McClorey et al.36 PCR products were separated on 2% agarose gels in Tris–acetate–EDTA buffer and the images were captured on a CHEMISMART-3000 gel documentation system (Vilber Lourmat, Marne-la-Vallee, France).

Supplementary MaterialFigure S1. (a) Exon 52 skipping induced by M52A(+12+41) and an AO cocktail of M52A(+17+41) & M52A(+42+71) at different concentrations in H-2K mdx myoblasts; and (b) the efficiency of exon skipping as determined by densitrometric analysis of RT-PCR.Figure S2. Exon 65 skipping induced by M65A(+63+87) and an AO cocktail of M65A(-11+14) & M65A(+26+50) at different concentrations in H-2K mdx myoblasts.

Supplementary Material

(a) Exon 52 skipping induced by M52A(+12+41) and an AO cocktail of M52A(+17+41) & M52A(+42+71) at different concentrations in H-2K mdx myoblasts; and (b) the efficiency of exon skipping as determined by densitrometric analysis of RT-PCR.

Exon 65 skipping induced by M65A(+63+87) and an AO cocktail of M65A(-11+14) & M65A(+26+50) at different concentrations in H-2K mdx myoblasts.

Acknowledgments

The authors received funding from the National Institutes of Health (RO1 NS044146-02), the Muscular Dystrophy Association USA (MDA3718), Charley's Fund, and the Medical and Health Research Infrastructure Fund of Western Australia. C.M. was supported by a scholarship from the Faculty of Medicine, Siriraj Hospital, Mahidol University, Thailand. We thank Dr. Fabian (Department of Neurology, Royal Perth Hospital, Perth, Australia) for supplying normal muscle biopsy material, after informed patient consent, (Institutional Human Ethics committee approval number RA/4/1/0962). The support of the Biobank of the MRC Neuromuscular Centre, London, is also acknowledged.

REFERENCES

- Blake DJ, Weir A, Newey SE., and , Davies KE. Function and genetics of dystrophin and dystrophin-related proteins in muscle. Physiol Rev. 2002;82:291–329. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00028.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emery AE. Muscular dystrophy into the new millennium. Neuromuscul Disord. 2002;12:343–349. doi: 10.1016/s0960-8966(01)00303-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emery AE. The muscular dystrophies. Lancet. 2002;359:687–695. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)07815-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Deutekom JC, Janson AA, Ginjaar IB, Frankhuizen WS, Aartsma-Rus A, Bremmer-Bout M, et al. Local dystrophin restoration with antisense oligonucleotide PRO051. N Engl J Med. 2007;357:2677–2686. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa073108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dominski Z., and , Kole R. Restoration of correct splicing in thalassemic pre-mRNA by antisense oligonucleotides. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1993;90:8673–8677. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.18.8673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bremmer-Bout M, Aartsma-Rus A, de Meijer EJ, Kaman WE, Janson AA, Vossen RH, et al. Targeted exon skipping in transgenic hDMD mice: a model for direct preclinical screening of human-specific antisense oligonucleotides. Mol Ther. 2004;10:232–240. doi: 10.1016/j.ymthe.2004.05.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graham IR, Hill VJ, Manoharan M, Inamati GB., and , Dickson G. Towards a therapeutic inhibition of dystrophin exon 23 splicing in mdx mouse muscle induced by antisense oligoribonucleotides (splicomers): target sequence optimisation using oligonucleotide arrays. J Gene Med. 2004;6:1149–1158. doi: 10.1002/jgm.603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wetterberg I, Zhao J, Masich S, Wieslander L., and , Skoglund U. In situ transcription and splicing in the Balbiani ring 3 gene. EMBO J. 2001;20:2564–2574. doi: 10.1093/emboj/20.10.2564. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gurvich OL, Tuohy TM, Howard MT, Finkel RS, Medne L, Anderson CB, et al. DMD pseudoexon mutations: splicing efficiency, phenotype, and potential therapy. Ann Neurol. 2008;63:81–89. doi: 10.1002/ana.21290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Sandre-Giovannoli A., and , Levy N. Altered splicing in prelamin A-associated premature aging phenotypes. Prog Mol Subcell Biol. 2006;44:199–232. doi: 10.1007/978-3-540-34449-0_9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bentley DL. Rules of engagement: co-transcriptional recruitment of pre-mRNA processing factors. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2005;17:251–256. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2005.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilton SD, Fall AM, Harding PL, McClorey G, Coleman C., and , Fletcher S. Antisense oligonucleotide-induced exon skipping across the human dystrophin gene transcript. Mol Ther. 2007;15:1288–1296. doi: 10.1038/sj.mt.6300095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mann CJ, Honeyman K, Cheng AJ, Ly T, Lloyd F, Fletcher S, et al. Antisense-induced exon skipping and synthesis of dystrophin in the mdx mouse. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2001;98:42–47. doi: 10.1073/pnas.011408598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith PJ, Zhang C, Wang J, Chew SL, Zhang MQ., and , Krainer AR. An increased specificity score matrix for the prediction of SF2/ASF-specific exonic splicing enhancers. Hum Mol Genet. 2006;15:2490–2508. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddl171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cartegni L, Wang J, Zhu Z, Zhang MQ., and , Krainer AR. ESEfinder: a web resource to identify exonic splicing enhancers. Nucleic Acids Res. 2003;31:3568–3571. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkg616. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yeo G, Hoon S, Venkatesh B., and , Burge CB. Variation in sequence and organization of splicing regulatory elements in vertebrate genes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:15700–15705. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0404901101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fairbrother WG, Yeh RF, Sharp PA., and , Burge CB. Predictive identification of exonic splicing enhancers in human genes. Science. 2002;297:1007–1013. doi: 10.1126/science.1073774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Errington SJ, Mann CJ, Fletcher S., and , Wilton SD. Target selection for antisense oligonucleotide induced exon skipping in the dystrophin gene. J Gene Med. 2003;5:518–527. doi: 10.1002/jgm.361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pramono ZA, Takeshima Y, Alimsardjono H, Ishii A, Takeda S., and , Matsuo M. Induction of exon skipping of the dystrophin transcript in lymphoblastoid cells by transfecting an antisense oligodeoxynucleotide complementary to an exon recognition sequence. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1996;226:445–449. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1996.1375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitrpant C, Fletcher S, Iversen PL., and , Wilton SD. By-passing the nonsense mutation in the 4(CV) mouse model of muscular dystrophy by induced exon skipping. J Gene Med. 2008;11:46–56. doi: 10.1002/jgm.1265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fall AM, Johnsen R, Honeyman K, Iversen P, Fletcher S., and , Wilton SD. Induction of revertant fibres in the mdx mouse using antisense oligonucleotides. Genet Vaccines Ther. 2006;4:3. doi: 10.1186/1479-0556-4-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adams AM, Harding PL, Iversen PL, Coleman C, Fletcher S., and , Wilton SD. Antisense oligonucleotide induced exon skipping and the dystrophin gene transcript: cocktails and chemistries. BMC Mol Biol. 2007;8:57. doi: 10.1186/1471-2199-8-57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harding PL, Fall AM, Honeyman K, Fletcher S., and , Wilton SD. The influence of antisense oligonucleotide length on dystrophin exon skipping. Mol Ther. 2007;15:157–166. doi: 10.1038/sj.mt.6300006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou Z, Licklider LJ, Gygi SP., and , Reed R. Comprehensive proteomic analysis of the human spliceosome. Nature. 2002;419:182–185. doi: 10.1038/nature01031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nilsen TW. The spliceosome: the most complex macromolecular machine in the cell. Bioessays. 2003;25:1147–1149. doi: 10.1002/bies.10394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jurica MS., and , Moore MJ. Pre-mRNA splicing: awash in a sea of proteins. Mol Cell. 2003;12:5–14. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(03)00270-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hartmuth K, Urlaub H, Vornlocher HP, Will CL, Gentzel M, Wilm M, et al. Protein composition of human prespliceosomes isolated by a tobramycin affinity-selection method. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002;99:16719–16724. doi: 10.1073/pnas.262483899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Z., and , Burge CB. Splicing regulation: from a parts list of regulatory elements to an integrated splicing code. RNA. 2008;14:802–813. doi: 10.1261/rna.876308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fox-Walsh KL, Dou Y, Lam BJ, Hung SP, Baldi PF., and , Hertel KJ. The architecture of pre-mRNAs affects mechanisms of splice-site pairing. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102:16176–16181. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0508489102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aartsma-Rus A, Bremmer-Bout M, Janson AA, den Dunnen JT, van Ommen GJ., and , van Deutekom JC.Targeted exon skipping as a potential gene correction therapy for Duchenne muscular dystrophy Neuromuscul Disord 200212S71–S77.suppl. 1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prior TW., and , Bridgeman SJ. Experience and strategy for the molecular testing of Duchenne muscular dystrophy. J Mol Diagn. 2005;7:317–326. doi: 10.1016/S1525-1578(10)60560-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz M, Duno M, Palle AL, Krag T., and , Vissing J. Deletion of exon 16 of the dystrophin gene is not associated with disease. Hum Mutat. 2007;28:205. doi: 10.1002/humu.9477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aartsma-Rus A, De Winter CL, Janson AA, Kaman WE, Van Ommen GJ, Den Dunnen JT, et al. Functional analysis of 114 exon-internal AONs for targeted DMD exon skipping: indication for steric hindrance of SR protein binding sites. Oligonucleotides. 2005;15:284–297. doi: 10.1089/oli.2005.15.284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cartegni L, Chew SL., and , Krainer AR. Listening to silence and understanding nonsense: exonic mutations that affect splicing. Nat Rev Genet. 2002;3:285–298. doi: 10.1038/nrg775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Black DL. Mechanisms of alternative pre-messenger RNA splicing. Annu Rev Biochem. 2003;72:291–336. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.72.121801.161720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McClorey G, Moulton HM, Iversen PL, Fletcher S., and , Wilton SD. Antisense oligonucleotide-induced exon skipping restores dystrophin expression in vitro in a canine model of DMD. Gene Ther. 2006;13:1373–1381. doi: 10.1038/sj.gt.3302800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mann CJ, Honeyman K, McClorey G, Fletcher S., and , Wilton SD. Improved antisense oligonucleotide induced exon skipping in the mdx mouse model of muscular dystrophy. J Gene Med. 2002;4:644–654. doi: 10.1002/jgm.295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sugnet CW, Kent WJ, Ares M., Jr, and , Haussler D. Transcriptome and genome conservation of alternative splicing events in humans and mice. Pac Symp Biocomput. 2004. pp. 66–77. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Sorek R, Shamir R., and , Ast G. How prevalent is functional alternative splicing in the human genome. Trends Genet. 2004;20:68–71. doi: 10.1016/j.tig.2003.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goren A, Ram O, Amit M, Keren H, Lev-Maor G, Vig I, et al. Comparative analysis identifies exonic splicing regulatory sequences—The complex definition of enhancers and silencers. Mol Cell. 2006;22:769–781. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2006.05.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernandez-Cadenas I, Andreu AL, Gamez J, Gonzalo R, Martin MA, Rubio JC, et al. Splicing mosaic of the myophosphorylase gene due to a silent mutation in McArdle disease. Neurology. 2003;61:1432–1434. doi: 10.1212/wnl.61.10.1432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yeo G., and , Burge CB. Maximum entropy modeling of short sequence motifs with applications to RNA splicing signals. J Comput Biol. 2004;11:377–394. doi: 10.1089/1066527041410418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rando TA., and , Blau HM. Primary mouse myoblast purification, characterization, and transplantation for cell-mediated gene therapy. J Cell Biol. 1994;125:1275–1287. doi: 10.1083/jcb.125.6.1275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

(a) Exon 52 skipping induced by M52A(+12+41) and an AO cocktail of M52A(+17+41) & M52A(+42+71) at different concentrations in H-2K mdx myoblasts; and (b) the efficiency of exon skipping as determined by densitrometric analysis of RT-PCR.

Exon 65 skipping induced by M65A(+63+87) and an AO cocktail of M65A(-11+14) & M65A(+26+50) at different concentrations in H-2K mdx myoblasts.