Abstract

Here, we report on the first systematic long-term study of fibroblast therapy in a mouse model for recessive dystrophic epidermolysis bullosa (RDEB), a severe skin-blistering disorder caused by loss-of-function of collagen VII. Intradermal injection of wild-type (WT) fibroblasts in >50 mice increased the collagen VII content at the dermal–epidermal junction 3.5- to 4.7-fold. Although the active biosynthesis lasted <28 days, collagen VII remained stable and dramatically improved skin integrity and resistance to mechanical forces for at least 100 days, as measured with a digital 3D-skin sensor for shear forces. Experiments using species-specific antibodies, collagen VII–deficient fibroblasts, gene expression analyses, and cytokine arrays demonstrated that the injected fibroblasts are the major source of newly deposited collagen VII. Apart from transitory mild inflammation, no adverse effects were observed. The cells remained within an area ≤10 mm of the injection site, and did not proliferate, form tumors, or cause fibrosis. Instead, they became gradually apoptotic within 28 days. These data on partial restoration of collagen VII in the skin demonstrate the excellent ratio of clinical effects to biological parameters, support suitability of fibroblast-based therapy approaches for RDEB, and, as a preclinical test, pave way to human clinical trials.

Introduction

Currently, causal therapies for genetic diseases are intensely explored by the international scientific community. Skin disorders are in the prime focus of such developments, as the target organ is easily accessible for both therapeutic measures and for analysis of their effects on macroscopic, microscopic, and molecular level. Unexpectedly, recent studies in animal models have revealed that relatively small biological changes, e.g., moderately increased levels of a missing protein in the skin, can have substantial clinical effects.1 Therefore, a large number of patients with genetic skin disorders will at this point not expect a complete cure, but welcome any biologically valid treatment modalities and advances that reduce symptoms, improve functionality, or increase the quality of life.

Epidermolysis bullosa (EB), a group of hereditary skin fragility disorders caused by mutations in genes encoding components of the epidermal adhesion complex,2,3,4,5 serves as ideal prototype for such investigations.6 Preliminary studies have demonstrated the principal promise of ex vivo–gene therapy and direct nonviral gene transfer approaches in cell culture, animal models7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14 and, in one case, in an individual with junctional EB.15 Very recently, in the severely affected collagen VII knockout mouse some improvement of symptoms was reported after the treatment with bone marrow–derived cells.16,17 However, both gene therapy and stem cell–based approaches still have to deal with numerous technical and safety problems including oncogenic potential of the vectors or the cells,18 which impede their rapid adaptation for clinical use.

In order to avoid the above-mentioned problems, allogeneic fibroblasts have been considered for intralesional treatment of recessive dystrophic EB (RDEB), a severe condition that manifests with mechanically induced skin blistering and scarring.3 Affected individuals are confronted with life-long skin fragility, impaired resistance of the integument to external shearing forces, and healing with scarring, a situation that leads to secondary symptoms including joint contractures, mutilating deformities of hands and feet, malnutrition, growth retardation and, as a severe complication, highly increased risk of skin cancer.19 RDEB is caused by mutations in the COL7A1 gene, which encodes collagen VII, a major component of the anchoring fibrils and an important adhesion molecule at the dermal–epidermal junction zone (DEJZ). To date, close to 500 different COL7A1 mutations have been reported, and an array of homozygous, heterozygous, and compound heterozygous mutations underlie a broad spectrum of phenotypes.20 The clinical and laboratory findings in patients, together with the effects of complete or partial inactivation of the Col7a1 gene in mice,1,21 clearly show that the main determinant of the blistering phenotype in RDEB is the absence or strongly reduced expression of collagen VII due to gene mutations. Therefore, therapeutic approaches for RDEB based on the restoration of collagen VII expression are in the center of interest of both researchers and patients.3

In vitro studies and pilot experiments with allogeneic normal or gene-corrected fibroblasts provided first indications that these cells can increase collagen VII content at the DEJZ in vivo in mice and humans with RDEB.1,11,12,22 Notably, fibroblast treatment of the collagen VII hypomorphic mouse, a model for RDEB, showed that already a small increase in collagen VII significantly stabilized the skin against shearing forces and ameliorated the phenotype,1 suggesting that a full restoration of collagen VII may not be required to improve functions and quality of life of patients. However, the preliminary studies opened a spectrum of new questions regarding the safety and potential adverse effects, as well as the mechanisms and duration of the therapeutic effects of the newly synthesized collagen VII.

Here, we performed the first systematic long-term evaluation of fibroblast-based therapy for RDEB using a standardized therapeutic regimen and assessment of functionality in a large number of mice. Remarkably, after 3–4 weeks of protein synthesis by fibroblasts, the levels of collagen VII remained significantly elevated for >3 months and substantially enhanced the mechanical integrity of the skin. Apart from mild inflammation, no notable adverse effects were observed. Thus, intradermal injections of normal fibroblasts may represent a first safe method of causal therapy for RDEB that could be expected to increase the resistance of the skin against external shearing forces and alleviate skin blistering and scarring in trauma-exposed skin areas.

Results

The cell therapy regimen

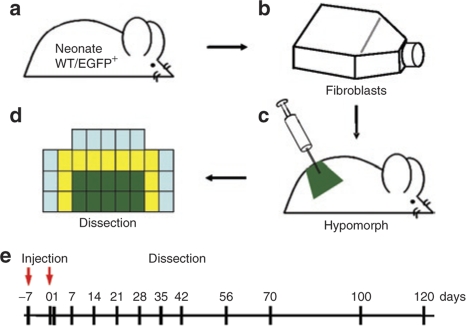

The collagen VII hypomorph was used for evaluation of fibroblast-based cell therapy. This viable and immunocompetent mouse model for RDEB has about 10% of normal collagen VII levels in the skin.1 The phenotype closely resembles severe human RDEB with trauma-induced mucocutaneous blistering, progressive nail dystrophy, and mitten deformities of the extremities. Mucosal fragility causes growth retardation, and repeated blistering leads to excessive tissue repair, contractile fibrosis, and pseudosyndactyly of the extremities, but the mice survive until adulthood.1 Here, the rationale was to test the therapeutic potential and putative adverse effects of intradermally applied syngeneic and allogeneic primary fibroblasts in a long-term in vivo setting. To this end, 5-week-old collagen VII hypomorphs (n = 55) were injected intradermally with either syngeneic wild-type (WT), hypomorphic fibroblasts from the same inbred strain, or with normal human fibroblasts (n = 33) for the monitoring of long-term efficacy, possible side effects, and potential paracrine stimulation of other cells. For assessment of the cell fate after injection, allogeneic enhanced green fluorescent protein expressing (EGFP+) fibroblasts (n = 22) were employed. Twenty million cells in 0.5 ml of normal saline were injected into a defined 1.5 × 2.5 cm area of caudal dorsal skin, and the procedure was repeated after 7 days. Neighboring and control areas were marked. The animals were killed at different time points 1–120 days after the second injection, and skin samples were obtained from injected, neighboring, and untreated areas for morphological and molecular analysis (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Schematic representation of the cell therapy regimen applied in this study. (a) Fibroblasts were isolated from the skin of newborn WT pups of the C57Bl/6-TgH(Col7a1flNeo)288LBT inbred strain or from the C57BL/6-Tg(ACTB-EGFP)1Osb/J strain (EGFP+ fibroblasts). (b) Fibroblasts in passages 2–3 were trypsinized, extensively washed and adjusted to a concentration of 40 × 106 cells/ml in sterile saline. (c) A volume of 0.5 ml of the cell suspension (i.e., 20 × 106 cells) were injected intradermally into a 1.5 × 2.5 cm skin area on caudal back of the collagen VII hypomorph. After 7 days, the procedure was repeated. (d) One hour before dissection, skin stability was assessed. Skin samples were obtained from symmetrically marked injected (green), neighboring (yellow), and untreated (blue) areas for (immuno)histopathological, ultrastructural, and molecular analysis. (e) The animals were killed 1–120 days after the second injection. EGFP, enhanced green fluorescent protein; WT, wild type.

The fate of injected fibroblasts

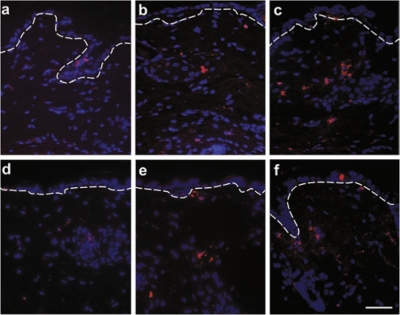

The fate of the therapeutic fibroblasts in the skin was assessed by injecting EGFP+ fibroblasts into the dermis and following them in biopsies from the injected, neighboring, and untreated areas. Twenty-four hours after the second injection, the EGFP+ fibroblasts were found in all vertical layers of the dermis within the injected area. Most cells remained in this area, but some lateral migration into untreated adjacent areas was observed (Figure 2a–c). Morphometric measurements revealed that cells did not move >10 mm from the test area, with only occasional cells found in neighboring areas. No EGFP+ fibroblasts were found in the circulation, as assessed by fluorescence-activated cell sorting analysis of peripheral blood (data not shown). The fibroblasts did not proliferate after the injection, as demonstrated by lack of Ki67-staining in the dermis, a marker for proliferation (data not shown). In contrast, with time, the number of the EGFP+ cells gradually decreased, and after 28 days, no EGFP+ cells were observed any more (Figure 2d–f). The morphological findings were corroborated by determining EGFP mRNA levels in the skin. The expression was increased during the first week after injections, but then gradually decreased until day 28, when no EGFP mRNA was detected in the injected skin anymore (Figure 2g).

Figure 2.

EGFP+ fibroblasts are present in the dermis for at least 21 days after intradermal injection, and actively synthesize protein. (a) At 24 hours after the second intradermal injection of 20 × 106 EGFP+ fibroblasts, the cells were found in all layers of the dermis within the injected area. (b) Some fibroblasts migrated into the adjacent skin, ≤10 mm from the marked area. (c) No cells were present in the skin >10 mm from the injection site. (d,e) The number of EGFP+ fibroblasts decreases with time: (d) 7 days after treatment, (e) 21 days after treatment, and (f) 28 days after treatment; at this point only very few EGFP+ fibroblasts were seen. EGFP+ fibroblasts appear in green, nuclei in blue. The interrupted white line depicts the DEJZ. Bar = 50 µm. (g) RT-PCR demonstrating EGFP mRNA expression by the cells within the time span of 1–28 days. The expression increased between 1 and 7 days (−, untreated; +, treated), but gradually decreased thereafter, until at day 28 no expression was seen. GAPDH expression was used as internal standard. EGFP, enhanced green fluorescent protein; GAPDH, glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase.

Measurement of EGFP+ areas per total dermis area, reflecting the cell number, corresponded to EGFP mRNA expression (Supplementary Figure S1). TUNEL (terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase dUTP nick end labeling)-assays of the injected areas demonstrated that the loss of EGFP mRNA and protein expression was due to apoptosis of the fibroblasts within 21–28 days (Figure 3a–c). The degree of apoptosis was similar when WT fibroblasts from the same inbred strain were injected (Figure 3d–f), indicating that EGFP+ fibroblasts and WT fibroblasts from the same inbred strain behave in a similar manner after injection.

Figure 3.

Fibroblasts gradually undergo apoptosis in the dermis. TUNEL assays of the injected areas showed that both EGFP+ and WT fibroblasts slowly become apoptotic in a similar manner. (a) In untreated control occasional apoptotic cells were seen in the epidermis. In treated skin, apoptotic cells were found in the dermis (b) 7 days and (c) 21 days after injection of EGFP+ fibroblasts. The situation was similar after injection of WT fibroblasts from the same inbred strain: (d) untreated control, (e) 7 days, and (f) 21 days after injection. Apoptotic cells appear in red, nuclei in blue. Bar = 50 µm. EGFP, enhanced green fluorescent protein; TUNEL, terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase dUTP nick end labeling; WT, wild type.

Intradermally injected fibroblasts actively synthesize collagen VII and appear to be the major source of newly deposited collagen VII at the DEJZ

The EGFP+ and WT fibroblasts in the dermis actively synthesized collagen VII, as demonstrated by both collagen VII mRNA and protein levels in the skin. The Col7a1 mRNA levels were clearly increased for 7–21 days after the second injection (Figure 4a–c), but returned to pretreatment levels by day 28 and remained low during the entire observation period of 100 days (Figure 4d–f).

Figure 4.

Injected fibroblasts actively express Col7a1 mRNA in the skin. Whole skin specimens obtained from WT, untreated (−), and treated (+) areas of the collagen VII hypomorph were used for total RNA extraction and RT-PCR amplification of collagen VII mRNA. In untreated skin, the expression of Col7a1 mRNA corresponds to ~8% of WT levels. In the areas treated with fibroblast injections, the expression of collagen VII increased between (a) 1 and (b) 7 days after injection and decreased gradually thereafter (21 days, c), until at (d) day 28, (e) day 70, and (f) day 100 the expression levels were similar to those in untreated areas. (g) Col7a1 mRNA expression in skin injected with fibroblasts isolated from a hypomorphic mouse. Note that in contrast to (b) WT cells, the injection of hypomorphic fibroblasts did not lead to increased Col7a1 mRNA expression at day 7 (g). Such an increase would have been expected, if the therapeutic cells exerted paracrine effects and stimulated keratinocytes to express collagen VII. (h) Semiquantification of Col7a1 mRNA levels by densitometry. Individual bands in panels a–g were normalized to GAPDH, and the WT band was set as 100%. The relative amount of Col7a1 mRNA in treated and untreated areas in % of WT are shown. GAPDH, glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase; hypo, collagen VII hypomorph fibroblasts; RT, reverse transcription; WT, wild type.

As collagen VII can be produced by both fibroblasts and keratinocytes,23 it was important to determine whether the injected fibroblasts in the dermis deposited collagen VII at the DEJZ, or whether paracrine signals from the injected or other cells stimulated epidermal keratinocytes to continuously synthesize the collagen. To test this, we employed four lines of experiments. First, fibroblasts isolated from newborn collagen VII hypomorphs, which only have ~10% of normal collagen VII levels, were injected intradermally in the same manner as WT cells. If the collagen VII found at the DEJZ was derived from keratinocytes induced by paracrine, fibroblast-derived stimuli, these injections should produce a similar effect as WT cells. However, no increase of Col7a1 mRNA (Figure 4g,h) levels was seen in the skin 7 days after the injections of hypomorphic fibroblasts, indicating that putative paracrine effects were minimal, and that the increased deposition of collagen VII was indeed derived from the WT fibroblasts. Second, to uncover unknown paracrine signals from injected fibroblasts, cytokine antibody arrays were employed to determine cytokine expression in collagen VII hypomorphic and WT fibroblasts.24 Of 96 cytokines in the array 92 showed no significant difference between the two cell types. In collagen VII hypomorphic fibroblasts, the low-affinity IgG receptor IIB (FcγRIIB) and platelet factor-4 were increased 2.1- and 3-fold, whereas insulin growth factor–binding protein-2 (IGFBP-2) and basic fibroblast growth factor were decreased 1.8- and 2.3-fold, respectively (Supplementary Figure S2). Downregulation of IGFBP-2, known to inhibit the proliferation of normal cells, and of basic fibroblast growth factor, is not directly correlated to known signaling cascades downstream of collagen VII. Collectively, this demonstrates, that collagen VII hypomorphic fibroblasts can serve as a control, and—as they did not stimulate collagen VII synthesis after injection—renders paracrine signals from injected fibroblasts as a major mechanism very unlikely. Third, to complement the cytokine arrays, skin treated with fibroblast injections was stained with antibodies to transforming growth factor-β and connective tissue growth factor. In the case that paracrine effects played a major role in the therapeutic success in these mice, these factors would be expected to be upregulated. However, there was no significant change in their expression in the injected skin (Supplementary Figure S3). Fourth, injections of normal human fibroblasts into the hypomorph skin enhanced deposition of human collagen VII at the DEJZ, as demonstrated using species-specific antibodies (see below). This observation delivers compelling evidence of fibroblasts as the cellular source for the therapeutic collagen VII.

Newly deposited collagen VII remained stable for >100 days

In congruence with the mRNA expression, the biosynthesis of collagen VII protein and its deposition at the DEJZ were enhanced after injections of murine or human fibroblasts. Untreated skin of the collagen VII hypomorph exhibits a barely visible collagen VII immunofluorescence signal (Figure 5a), but 70 days after the second fibroblast injection the content of collagen VII protein at the DEJZ was significantly increased (Figure 5b). Injection of normal human fibroblasts lead to an increase of human collagen VII, as shown with human-specific antibodies (Figure 5e), further supporting the prediction that the collagen VII was derived from the injected fibroblasts. The strong immunofluorescence signals persisted for extended periods (Figure 5b,c). Semiquantitative confocal laser microscopy demonstrated that 70 days after injection of WT fibroblasts, collagen VII fluorescence levels were 4.7-fold higher than in untreated skin (P < 0.001), at 100 days 3.5-fold higher (P < 0.001; Figure 5f), and at 120 days about twofold higher than in untreated skin (P < 0.05; data not shown). It is remarkable that after only 3–4 weeks of protein synthesis by fibroblasts, the levels of collagen VII remained significantly elevated for >3 months.

Figure 5.

Collagen VII deposition is restored at the DEJZ. (a) In untreated hypomorphic skin, collagen VII is strongly reduced. (b) Increased collagen VII levels at the DEJZ 70 days after injection of murine WT fibroblasts. (c) The increased levels persisted for at least 100 days. (d) WT control. (e) Injection of normal human fibroblasts increased deposition of human collagen VII at the DEJZ 7 days after injection, as shown with the NC1-F3 antibody, specific to human collagen VII.44 This clearly demonstrates that fibroblast-derived collagen VII is incorporated into the DEJZ. Collagen VII appears in green, nuclei in red. Bar = 25 µm. (f) Semiquantitative confocal microscopy (n = 5 per group) using identical image settings demonstrated that the relative mean intensity of collagen VII fluorescence signals at the DEJZ was significantly increased after treatment with WT fibroblasts, as compared to untreated skin of the hypomorphic mice. At 70 days after injection, collagen VII signals were 4.7-fold higher and 100 days after injection 3.5-fold higher than in untreated skin (Mean plus standard deviation, the asterisks denote statistical significance, ***P < 0.001; *P < 0.05 in Student's t-test). After 100 days, the levels continued to decline, but were still about twofold higher at 120 days than in untreated skin (P < 0.05). (g) Ultrastructural analysis showed normal hemidesmosomes, but lack of anchoring fibrils in untreated skin of the collagen VII hypomorph. Magnification ×35,000. (h) Some filamentous aggregates with frayed ends (inset, arrows) could be discerned 70 days after fibroblast treatment in the skin of the collagen VII hypomorph. Magnification ×39,000. DEJZ, dermal–epidermal junction zone; WT, wild type.

One of the hallmarks of RDEB skin is the reduced number of anchoring fibrils.5 This is also the case in the collagen VII hypomorph,1 which has almost no anchoring fibrils at the DEJZ (Figure 5g). Also in this regard, the fibroblast injections seemed to have a positive effect. After 70 days, filamentous aggregates with frayed ends could be recognized with transmission electron microscopy (Figure 5h), suggesting that the newly synthesized collagen VII is fibril-competent and capable of specific aggregation.

Skin integrity and resistance to external mechanical forces is improved by fibroblast injections

Functionally, the skin areas treated with fibroblast injections exhibited clearly improved dermal–epidermal adhesion and stability against shear forces, as compared to untreated areas. Shear forces were applied to the skin and detected using a silicon-based 3D force sensor (Figure 6a).25 Fibroblast-treated skin resisted without blistering average forces of 341 mN, applied 20 times within 20 seconds (Figure 6b), whereas in untreated skin dermal–epidermal separation and blister formation occurred. Remarkably, still 70 days and 100 days after fibroblast treatment notable differences between treated and untreated skin areas were observed (Figure 6c–f). After 70 days, in untreated skin, the above-mentioned shear forces led to blistering, with an average of 27% of the length of the DEJZ being separated. In contrast, in fibroblast-treated skin, dermal–epidermal separation occurred in <1% of the junction (Figure 6g). One-hundred days after injections, the resistance of treated skin to shear forces was still high, with only 2.5% separation of the DEJZ (Figure 6g).

Figure 6.

3D force sensor shows enhanced resistance against mechanical forces after fibroblast treatment. (a) The silicon-based 3D force sensor with the tactile element, i.e., a silicone cylinder with hemispherical tip (red). The silicon chip is mounted and wire-bonded to a printed circuit board. The silicone cylinder serves as tactile element to apply frictional stress to the skin and to mechanically stabilize the fragile silicon structure. (b) Shear forces applied to the skin as a function of time. The forces were detected using the 3D force sensor shown in a. In this specific case, shear forces of 380.6 ± 134.6 mN were extracted. Fibroblast-treated skin resisted average forces of 341 mN, applied 20 times within 20 seconds, without blistering (c,e), whereas in untreated skin (d,f) dermal–epidermal separation and blister formation occurred (arrows), as demonstrated with hematoxylin/eosin staining of skin sections. (c,d) 70 days and (e,f) 100 days after fibroblast treatment. Bar = 50 µm. (g) Morphometric quantification of skin integrity after application of frictional stress, 70 and 100 days after fibroblast treatment. The graph depicts the percentage of blistered DEJZ. White columns: untreated skin. Black columns: treated skin (mean plus standard deviation). DEJZ, dermal–epidermal junction zone.

Fibroblast injections generated a mild transient inflammatory reaction, but no specific immune response to collagen VII

A major concern about cell or protein therapy approaches in genetic diseases is the potential development of immune reactions against the therapeutic agent. Therefore, we searched for both signs of inflammation and immune reactions to collagen VII. Immunohistochemical staining with the CD11b antibody revealed initial mild inflammatory cell infiltrates in the dermis after the fibroblast injections (Figure 7a). However, the infiltrates subsided within 21 days (Figure 7b,c), concomitantly with apoptosis of the fibroblasts. To assess putative inflammatory responses to multiple fibroblast injections, collagen VII hypomorphs were subjected to repeated WT fibroblast injections. Four injections, 20 million cells each, were administered with 1-week intervals. Seven days after the fourth injection, a mild inflammatory infiltrate was observed (Figure 7d), which was not more intensive than in the skin after two cell injections.

Figure 7.

Fibroblast injections cause a transient inflammatory reaction but no immune response to collagen VII. (a) Positive immunofluorescence staining of CD11b, a marker for monocytes, dendritic cells, and macrophages, revealed a mild inflammatory infiltrate in the dermis 24 hours after fibroblast injection. (b) The number of CD11b-positive inflammatory cells was reduced after 7 days. (c) No inflammatory cells were observed in the skin 21 days after injection. (d) To analyze the inflammatory response to multiple fibroblast injections, which could be necessary in the treatment of DEB patients, collagen VII hypomorphs were injected four times with 1-week intervals. Seven days after the fourth injection a mild inflammatory infiltrate was observed, similar to that seen in c. CD11b-positive cells appear in red, nuclei in blue. The interrupted white line depicts the DEJZ. (e–h) Potential therapy-induced immune reactions to collagen VII were tested with indirect immunofluorescence staining. (e) Positive control with collagen VII antibody shows a linear signal at the DEJZ. Circulating antibodies to the DEJZ were screened with indirect immunofluorescence staining of normal mouse skin with 25 sera of fibroblast-treated mice. (f) A serum obtained 120 days after fibroblast injections showed no reactivity. (g) Only one of 25 sera of fibroblast-treated mice (obtained 56 days after injection) displayed a very faint positive reaction with the DEJZ. (h) However, when this serum was tested with immunoblotting, it failed to recognize collagen VII. 1: positive control, 2: the serum used in h. Arrow: collagen VII. Bar = 50 µm. DEJZ, dermal–epidermal junction zone.

The presence of potential tissue-bound anticollagen VII antibodies at the DEJZ was evaluated with direct immunofluorescence staining. The skin of all mice treated with syngeneic WT or allogeneic EGFP+ fibroblasts remained negative during ≤ 120 days (data not shown). Circulating anticollagen VII antibodies in the serum of fibroblast-treated animals were tested with indirect immunofluorescence staining using normal mouse skin as a substrate. Of the 25 sera tested, only one, obtained 56 days after treatment with syngeneic WT fibroblasts, showed weak reactivity with the DEJZ (Figure 7e–g). However, immunoblot analysis with this serum failed to reveal specificity to collagen VII (Figure 7h). Taken together, no specific immune reaction to collagen VII was seen within the observation period of 4 months after fibroblast injections.

Lack of fibrotic reactions in the dermis after fibroblast injections

A potential undesired effect of fibroblast injections is excessive synthesis of extracellular matrix proteins and local fibrosis in the dermis, similar to subcutaneous nodules or hypertrophic scars. As excessive scarring is an inherent problem in RDEB, such a reaction to fibroblasts would be counterproductive and inacceptable. To address this, we followed dermal changes in the collagen VII hypomorph for 70 days after fibroblast injections. Transforming growth factor-β and connective tissue growth factor were used as markers for paracrine stimulation, enhanced extracellular matrix production and initial fibrosis (Supplementary Figure S3). α-Smooth-muscle-actin was used as a marker for fibroblast-to-myofibroblast differentiation associated with contractile fibrosis,26 and tenascin C as an indicator for synthesis of extracellular matrix components.27 All these markers remained essentially unchanged 7, 21, and 70 days after treatment (data not shown), indicating that the therapeutic cells did not induce processes associated with excessive cell–matrix aggregation, scarring, or pathological fibrosis.

Collagen VII synthesis in cultured human fibroblasts does not decrease with donor age and passaging number of cells

First-passage fibroblast extracts from a 5-year-old individual and tenth-passage fibroblast extracts from a 53-year-old individual were immunoblotted with an anticollagen VII antibody, to assess a putative loss of collagen VII expression with passaging or advancing donor age. Similar collagen VII expression was found in both fibroblast extracts (Supplementary Figure S4), indicating that donor age or higher passaging of fibroblasts does not significantly affect collagen VII expression in these cells.

Discussion

At present, the general therapeutic outline for inherited skin fragility disorders is only symptomatic and consists of the avoidance and minimization of environmental factors, which induce blistering and complicate wound healing.3 Therefore, the development of curative molecular therapies is urgently needed. Even though the clinical application of such treatments may still be in the far future, even small improvements will be highly significant for the affected individuals. Recent progress with experimental therapies, both in preclinical models and in some individuals with EB, included approaches ranging from gene transfer to bone marrow transplantation.1,7,8,9,10,11,12,14,15,16,17,22,28,29,30,31,32,33,34 However, all of these still deal with a number of technical and strategic challenges.6,18,35

An intriguing question is whether the goal of therapeutic developments should be a complete cure or whether a stepwise approach, from intralesional therapy to systemic application, would be more realistic and lead faster to clinical studies. Critical evaluation of the data in the literature tends to favor the latter option. For intralesional applications, fibroblast cell therapy seems promising.1,11,12,22 First, these cells bear technical advantages, as they can be easily cultivated, expanded, and injected into the skin. Second, primary fibroblasts have not been genetically modified by transfection with a therapeutic gene or during an immortalization process, which could induce the development of malignancies. Third, as shown here, only two intradermal fibroblast injections increased the dermal–epidermal adherence in collagen VII hypomorphic mice for >3 months, without notable adverse effects.

This study represents the first systematic long-term evaluation of fibroblast-based therapy for RDEB using a standardized therapeutic regimen and assessment of functionality in a large number of mice. It delivers several lines of novel information: (i) the stability of collagen VII protein in situ is remarkably high and an essential prerequisite for the therapeutic success; (ii) significant clinical improvement of RDEB does not require full restoration of collagen VII; (iii) fibroblasts seem to be the major source of the therapeutic collagen VII; (iv) injected fibroblast undergo apoptosis within 28 days and cause mild inflammation; (v) no immune response to collagen VII was caused by the therapy.

Remarkably, substantial clinical improvement was achieved with the present regimen despite gradual apoptosis of the fibroblasts. During 21–28 days, the injected cells actively synthesized collagen VII and deposited it at the DEJZ. We used primary fibroblasts and achieved an almost fivefold increase of collagen VII content at the DEJZ and restored skin stability for >3 months (Figure 8). This demonstrates on one hand that the strategy of delivering collagen VII via authentic dermal cells successfully recruits the collagen to its ligands at the DEJZ and produces functional protein suprastructures and, on the other hand, reflects the long half-life of collagen VII in situ, which is highly advantageous in the present context. Recently, a different approach using an inducible collagen VII knockout mouse also confirmed the long half-life of collagen VII in vivo.36

Figure 8.

Long-term responses of RDEB skin to fibroblast injections. This graphic illustration summarizes the molecular, cellular, and functional responses of RDEB skin to fibroblast injections as correlation of time. The values were obtained as shown in the Results and Figures 2–6. The X-axis represents days after the second fibroblast injection (not drawn to scale), the Y-axis depicts relative units for each parameter. Green line: EGFP+ fibroblasts in the skin. The amount was determined on the basis of EGFP mRNA expression in the skin. The maximal amount of EGFP mRNA found at 7 days was set as the value of 1.0. With time, the number of the EGFP+ fibroblasts gradually decreased, and after 28 days, no cells/EGFP mRNA synthesis were observed any more. Grey line: Col7a1 mRNA expression in the skin. The maximal amount of Col7a1 mRNA found at 7 days was set as the value of 1.0. Similar to EGFP expression, collagen VII mRNA decreased gradually and reached pretreatment levels after 28 days. Blue line: Collagen VII protein at the DEJZ. The injected cells generated a maximally 4.7-fold increase of collagen VII content at the DEJZ. This was set as the value of 1.0, present still 70 days after the second injection. The collagen VII content then slowly decreased to 0.75 relative units at 100 days, still a remarkably high value. Red line: Skin blistering as an indicator of adhesive collagen VII functions at the DEJZ. The pretreatment level of mechanically induced blistering was set as the value of 1.0. Within 7 days, the fibroblast injections resulted in a significant increase in adhesive collagen VII functions and in drastic reduction of skin blistering. These positive effects persisted for at least 70 days. Thereafter, blistering tendency slowly increased, but as compared to pretreatment levels was still low at 100 days. Taken together, it is notable that even though protein biosynthesis by the injected fibroblasts lasted maximally 28 days, the long half-life of collagen VII protein at the DEJZ contributed to significantly increased skin integrity during extended periods of time. DEJZ, dermal–epidermal junction zone; EGFP, enhanced green fluorescent protein; RDEB, recessive dystrophic epidermolysis bullosa.

The time course of therapeutic effects shows that about 3.5-fold increase of collagen VII at 100 days (about 35% of normal levels) still provided reasonable stability against shear forces, but a twofold increase at 120 days (about 20% of normal levels) did not (Figure 8). The data are in line with morphometric analyses of the lateral density of anchoring fibrils at the DEJZ, which revealed that in DEB skin the fibrils were reduced to 0–33% (ref. 37). The findings also agree with the fact that heterozygous carriers of COL7A1 null mutations, who express 50% of normal collagen levels, are phenotypically normal. Taken together, these observations indicate that ≥ 35% of physiological collagen VII levels are necessary for mechanical stability of the skin36 and this should be the goal of molecular and cell therapies for DEB.

As both keratinocytes and fibroblasts have the capacity to synthesize collagen VII, other investigators have pondered the significance of paracrine stimulatory effects after injection of therapeutic cells into the skin.22 Here, this question was carefully addressed by using human instead of mouse fibroblasts for injections, and by comparing the effects of primary fibroblasts isolated from newborn WT and hypomorphic mice, as well as their cytokine profiles. Notably, intradermally injected human fibroblasts deposited human collagen VII at the DEJZ of the hypomorphic mouse, thus corroborating the role of fibroblasts as the source for collagen VII. This was further supported by experiments with hypomorphic fibroblasts, which can synthesize only 10% of the normal collagen VII amounts. If paracrine effects were substantial, and the injected fibroblasts induced collagen VII synthesis in keratinocytes, a similar increase in collagen VII mRNA and protein should be seen after administration of WT and collagen VII hypomorphic fibroblasts. Our experiments clearly demonstrated lack of durable stimulus by hypomorphic cells. One week after injections of hypomorphic fibroblasts, collagen VII mRNA levels remained unchanged and immunofluorescence signals at the DEJZ, which reflect the amount of collagen VII protein, remained as low as in untreated skin. In contrast, both parameters were strongly increased in the skin treated with WT fibroblasts.

Yet another possibility is that the cytokine profile of hypomorphic fibroblasts could differ from that in WT cells. Therefore, we assessed the profiles on arrays that detect 96 cytokines. Ninety-five percent of the cytokines showed no difference. The minor differences found in cytokine expression between WT and hypomorphic fibroblasts are not involved in collagen VII signaling. In hypomorphic fibroblasts, about twofold downregulation of basic fibroblast growth factor and of IGFBP-2 was found. Basic fibroblast growth factor has multiple functions in vivo; it can stimulate proliferation and migration of endothelial cells and participates in inflammation.38 IGFBP-2 can act as an inhibitor of cell growth in vivo, most likely through modulation of IGF bioactivity.39 Its downregulation in hypomorphic fibroblasts is consistent with their slightly decreased growth potential, which reduces mTOR activity upstream of IGFBP-2 (ref. 40). These changes are not correlated with collagen VII signaling, which was recently shown to involve CXCL10 and downstream-associated phospholipase C signaling.41 In summary, several approaches in this study failed to deliver evidence for paracrine stimulation of collagen VII synthesis in keratinocytes. Nevertheless, some hitherto unknown effects on epidermal cells that contribute to skin integrity cannot be excluded with certainty.

Primary newborn fibroblasts seem to represent a safe therapeutic regimen. The injections did not cause adverse effects through cell migration into neighboring or distant sites. The fibroblasts moved maximally 10 mm into the adjacent dermis, and no EGFP+ fibroblasts were found in the circulation. An important issue for therapeutic safety considerations is also that the fibroblasts did not proliferate, lead to hypercellularity of the dermis, or cause tumors.42 Clinically, apart from mild edema at the injection site, no signs of inflammation, i.e., redness, pain, or itch were evident after fibroblast injections. Microscopically, a transient inflammatory infiltrate was seen in the injected areas after 1 and 7 days. The infiltrate subsided by day 21, as the fibroblasts gradually underwent apoptosis.

Future fibroblast therapy of human RDEB is likely to involve injections of allogeneic fibroblasts derived from unrelated donors (e.g., foreskin fibroblasts) or siblings, and expansion of cells for multiple injections may be necessary. We addressed these points by evaluating the therapeutic potential and risks of allogeneic EGFP+ fibroblasts that are not derived from the same inbred mouse strain. No difference in terms of effects/adverse effects was observed between these cells and WT fibroblasts. In addition, we performed multiple injections of WT fibroblasts, and found that the inflammatory response was similar to the two-injection regimen, which is an encouraging result for this therapeutic strategy. A putative reduction of collagen VII expression with passaging number or advancing donor age was analyzed using human fibroblasts from healthy donors of different age. Collagen VII expression in fibroblasts derived from the skin of a 5-year-old individual, in passage one, did not significantly differ from that in fibroblasts derived from the skin of a 53-year-old individual, in passage 10 (Supplementary Figure S4), indicating that expansion of fibroblasts for multiple injections for treatment RDEB patients would be feasible and not lead to loss of expression of the therapeutic molecule.

As excessive scarring is an inherent problem in RDEB, it is important that the therapeutic cells do not have fibrotic potential. Histopathology revealed normal dermal matrix structures and no nodules or tumors in treated areas. No signs of early fibrosis in the injected areas were detected by immunohistochemical analyses; i.e., transforming growth factor-β, connective tissue growth factor, or myofibroblasts were not induced in the dermis. In contrast, it seems likely that the therapeutic fibroblasts produce extracellular matrix components that integrate into the dermal matrix scaffold, support normal fibroblast functions, and undergo normal turnover. Based on these observations, one could envisage future fibroblast cell therapy of still nonscarred skin areas, e.g., in the hands or feet, as a preventive measure to alleviate the severe blistering–scarring cycles in trauma-exposed skin.

Putative immune reactions to the therapeutic collagen VII present a further concern. A protein therapy approach with recombinant collagen VII generated high titers of collagen VII antibodies in the circulation of the Col7a1 knockout mice.34 In this study, when the collagen was synthesized by fibroblasts in the dermis, no immune reaction developed during 120 days of observation. Direct immunofluorescence staining of the mouse skin remained negative in 100% of the animals, and only 1/25 sera reacted discretely with the DEJZ; however, further tests with this serum did not establish specificity to collagen VII.

Taken together, this study proves the suitability of fibroblasts for cell therapy in RDEB in a preclinical setting and demonstrates the excellent ratio of clinical effects to biological parameters: relatively short duration of collagen VII biosynthesis resulted in greatly improved skin integrity for extended periods of time. As intradermally injected fibroblasts undergo apoptosis within 28 days, repeated injections will be necessary for sustained clinical effects. In order to improve this therapeutic approach, it will be intriguing to delineate the reasons for fibroblast apoptosis in the dermis and to find ways to prevent or slow down cell death, perhaps by optimizing cell isolation and culture, by downregulation of apoptosis mediators, or by improving the matrix scaffolding in the dermis.

Materials and Methods

Mouse strains. The collagen VII hypomorph, i.e., the immunocompetent C57Bl/6-TgH(Col7a1flNeo)288LBT transgenic strain,1 which closely resembles severe human RDEB, was used for all treatments. In this mouse, collagen VII in the skin is reduced by about 90% due to suppression of its expression by the Neo-cassette, and very few anchoring fibrils are present. The clinical phenotype includes practically all symptoms of severe human RDEB, i.e., trauma-induced mucocutaneous blistering, progressive nail dystrophy, and development of mitten deformities of the extremities as a result of repeated blistering, excessive tissue repair, and contractile fibrosis. Mucosal fragility causes difficulty in feeding and growth retardation, but the mice survive until adulthood when kept on liquid diet. Therefore, the pups were fed baby formula (Bebivita, Munich, Germany) with Nutri-plus Gel dietary supplement (Virbac, Carros Cedex, France) and ground animal feed dissolved in water (Kliba Nafag, Kaiseraugst, Switzerland), ad libitum, starting at day 10 after birth. Heterozygous siblings were mated to maintain the strain and obtain collagen VII hypomorphs. The C57BL/6-Tg(ACTB-EGFP)1Osb/J (Jackson Laboratory, Bar Harbor, Maine) mouse strain was used for isolation of EGFP+ fibroblasts. All animal experiments in this study were approved by the institutional and state review board (no. 35/9185.81/G-05/08).

Human fibroblasts. Studies with material derived from human donors have been approved by the ethical committee/institutional review board (no. 16603). Patients gave informed consent for the use of their material and clinical data for research and publication; all clinical investigations were conducted according to the Declaration of Helsinki.

Isolation and culture of fibroblasts. Fibroblasts were isolated from skin of newborn collagen VII hypomorphs, WT littermates, C57BL/6-Tg(ACTB-EGFP)1Osb/J mice, or human skin, essentially as described.43 Briefly, after washing the skin specimens with 70% ethanol, dermal–epidermal separation was induced by digestion with 0.5% trypsin (wt/vol) for 30 minutes at 37 °C. The reaction was stopped with phosphate-buffered saline containing 10% fetal calf serum and the epidermis was mechanically removed. The dermis was digested with 500 U/ml collagenase type I (Worthington, Lakewood, NJ) for 60 minutes in a shaking water bath at 37 °C, and the cells plated in a Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium/Ham's F12-mixture (1:1; Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) containing 10% fetal calf serum and 100 U/ml penicillin, 100 µg/ml streptomycin and 0.25 µg/ml amphotericin B (all Invitrogen). For cell injections, fibroblasts in passage 2–3 were washed extensively after trypsinization and then adjusted with saline to a concentration of 40 x 106 cells/ml (Figure 1a,b).

Cell therapy regimen. Five-week-old collagen VII hypomorphs were injected intradermally with either WT or hypomorphic fibroblasts from the same inbred strain for monitoring of long-term effects, allogeneic EGFP-expressing fibroblasts, or normal human fibroblasts. The mice were treated under isoflurane anesthesia after the dorsal skin was shaved and disinfected with octenidine-2HCl-phenoxyethanol (Schülke & Mayr, Hamburg, Germany). Into a marked caudal back skin area of 1.5 × 2.5 cm of each mouse, 20 × 106 cells in 0.5 ml of sterile saline were injected intradermally with a 27 G needle. This procedure was performed twice with an interval of 7 days (Figure 1) to evaluate therapeutic effects and possible side effects, or four times to evaluate a putative inflammatory response to multiple injections. Neighboring and cranial control areas were marked symmetrically. One hour before dissection, skin stability was assessed under isoflurane anesthesia (see below). Skin samples were obtained from injected, neighboring, and untreated areas for (immuno)histopathological, ultrastructural, and molecular analysis. The animals were killed 1–120 days after the last injection (1–42 days: EGFP+ fibroblast and normal human fibroblasts; and 7, 21, and 56–120 days: WT fibroblast treatment) (Figure 1).

Skin stability assessment with a micromechanichal 3D force sensor. Shear forces were applied to the skin using a silicone cylinder (diameter 5.7 mm, length 13.7 mm, Elastosil M4642 A) with a hemispherical tip. The cylinder was mounted on a silicon-based micromechanical force sensor enabling the monitoring of shear forces parallel to the skin surface to be monitored. The sensor chip comprises a flexible cross-structure suspended by 20-µm thin membrane hinges within a solid silicon frame.25 Piezoresistive stress sensor elements are integrated in the membrane hinges and detect deformations of the cross structures caused by forces applied to the tactile element, i.e., the silicone cylinder. The 3D silicon-based force sensor was attached and wire-bonded to a printed circuit board (Figure 6a). In combination with the silicone cylinder the sensor exhibited sensitivities of Sx = (0.458 ± 0.036)VN−1V−1 and Sy = (0.445 ± 0.034)VN−1V−1 for forces Fx and Fy applied to the silicone cylinder in the x and y directions, respectively. The sensitivity Si is defined as Si = Vout/(FiVbias) where Fi, Vout, and Vbias denote the applied force, the sensor output and bias voltages, respectively. Figure 6b shows a typical experiment with the extracted shear force Fshear = (Fx2 + Fy2)1/2 as a function of time.

Light and electron microscopy. Skin specimens of treated and untreated areas were stained with hematoxylin–eosin using standard methods for light microscopy. For estimation of the extent of skin blistering, the length of intact and separated areas at the DEJZ (microblisters) was traced with the Zeiss AxioVision software (version 4.6). The relative extent of blistering was determined on the basis of separated areas at the DEJZ/total length of the DEJZ. For electron microscopy, specimens of treated, and untreated skin were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde/2% glutaraldehyde at 4 °C. They were then washed twice in 0.1 mol/l cacodylate buffer and incubated in 1% osmium tetroxide solution for 1 hour. Samples were dehydrated in ethanol (25, 50, 75, 90, 100%) and propylene oxide and embedded in an epoxy resin. Sections (70 nm) were mounted on microscopy grids, stained with 5% uranyl acetate and Reynold's solution.1

Immunofluorescence staining. Four micrometer skin cryosections were air-dried for indirect immunofluorescence staining. An overnight incubation at 4 °C with the primary antibodies was followed by a 1 hour incubation with the secondary antibodies, intensive washing and mounting in Fluorescence Mounting Medium (Dako, Glostrup, Denmark). The primary antibodies used were: polyclonal anticollagen VII (Calbiochem, La Jolla, CA), polyclonal human-specific anticollagen VII NC1-F3 (ref. 44), anti-EGFP (Chemicon, Temecula, CA), anti-Ki-67 (Dako), anti-CD11b (BD Biosciences, Franklin Lakes, NJ), anti–transforming growth factor-β (Promega, Madison, WI), anti–connective tissue growth factor (GeneTex, San Antonio, TX), antitenascin C (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN) and anti-α-smooth-muscle-actin (Sigma, St Louis, MO). Secondary antibodies used were: anti-rabbit-Alexa488 IgG, anti-rabbit-Alexa594 IgG, anti-rat-Alexa488 IgG, and streptavidin- Alexa488 (Invitrogen). Nuclei were stained with DAPI (Sigma).

For analysis of tissue-bound antibodies reactive with the DEJZ, skin-sections obtained 7–120 days post-treatment were incubated with anti-mouse-Alexa594 IgG (Invitrogen). For indirect immunofluorescence analysis of circulating antibodies, cryosections of normal mouse skin were incubated with sera of fibroblast-treated hypomorphic mice. Sera were obtained 7–120 days post-treatment and used in dilution 1:10.

Semiquantitative confocal microscopy and assessment of EGFP+ fibroblasts in the dermis. Semiquantitative comparison of collagen VII immunofluorescence signal intensity at the DEJZ of fibroblast-treated and untreated skin was performed by confocal microscopy as described.1,45 Per group, five cryosections were stained for collagen VII as described above. Z-stacks with five sections (distance 0.8 µm) of monochrome 12-bit gray-level images were recorded using identical settings and multichannel acquisition after excitation at 488 nm (Alexa 488, emission LP 505 nm; Invitrogen), with an LSM510 confocal microscope equipped with an LD LCI-Apochromat 25×/0.8 glycerine objective (Zeiss, Jena, Germany). Images with 2,048 × 2,048 pixels (0.18 µm isotropic) were recorded and the pinhole adjusted to 1 airy unit (corresponding to a slice thickness of 1.6 µm). The full version of Zeiss LSM software (version 4.2) was used for data analysis, after the image plane with the highest mean intensity signal was chosen. Three independent DEJZ areas (defined as n = 1) were measured and the intensity of an adjacent epidermal area of the same size subtracted as background, to obtain the mean intensity of the collagen VII signal at the DEJZ. Based on the mean collagen VII intensity at the DEJZ of untreated hypomorphs, relative intensities were calculated. To asses the amount of EGFP+ fibroblasts in the dermis, the surface of EGFP+ dermis areas was measured with the Zeiss AxioVision software (version 4.6) and set in relation to total dermis surface in the image.

TUNEL assay. Apoptotic cells were identified in tissue sections using the In situ Cell Death Reaction Kit (Roche Diagnostics, Mannheim, Germany) according to the manufacturer's recommendations.

RNA isolation and RT-PCR. Frozen s kin samples were homogenized and total RNA isolated using the RNeasy Fibrous Tissue Mini Kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany). Reverse transcription of RNA was performed using the Advantage RT-for-PCR Kit (BD Biosciences). The primers used for amplification of collagen VII complementary DNA with Taq DNA Polymerase (Invitrogen) were: Col7a1 exon 1–exon 3: 5′-CTGCAGAGATCCTGATGGGA-3′, 5′-CAGGACGTGTTAGACGAGGC-3′; EGFP complementary DNA was amplified with the following primers: 5′-CTGGTCGAGCTGGAC GGCGACG-3′, 5′-CACGAACTCCAGCAGGACCATG-3′ (Biomers.net, Ulm, Germany). Amplification of glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase was used as loading control to ensure equal complementary DNA amounts. For semiquantitative densitometry, the Gel-Pro Express 4.0 software (Media Cybernetics, Bethesda, MD) was used.

Cytokine antibody arrays. For preparation of cell extracts for the cytokine antibody array analysis, two subconfluent 150-cm2 flasks of control and hypomorphic fibroblasts were used. Cells were washed four times with phosphate-buffered saline, scraped off with a sterile scraper, and shock-frozen in liquid nitrogen. Protein extracts were prepared by dissolving the cells in a cell lysis buffer (Ray Biotech, Norcross, GA) containing a protease inhibitor cocktail (Roche Diagnostics) according to the manufacturer's instructions. The homogenate was cleared by centrifugation at 14,000 rpm at 4 °C for 15 minutes. The protein concentration of the supernatant was determined with the Bradford method. Further handling was performed as described.24 RayBio mouse cytokine antibody arrays, C series 1000.1 (Ray Biotech) were employed to assay cell lysates derived from the hypomorphic and control fibroblasts. In a volume of 1.2 ml supernatant, 200 µg total protein was used to probe the cytokine antibody arrays according to the manufacturer's instructions. Cytokine antibody array nitrocellulose membranes were developed by standard enhanced chemiluminescence techniques. The relative spot intensities for each cytokine were determined by densitometry and plotted for hypomorphic fibroblast extracts in comparison to WT extracts. Spot intensities were determined by 2D densitometry using the AIDA software of the phosphoimager BAS 1800II (Fuji/Raytest, Straubenhardt, Germany). Individual background values were subtracted, and spot intensities were normalized according to positive control signals. Relative spot intensities are presented as means ± SD. Microsoft Excel was utilized for statistical analysis.

Western blotting of mouse keratinocyte and human fibroblast extracts. Keratinocytes isolated from murine skin and human fibroblasts were cultured to early confluence46 and extracted as described.47 For immunoblotting, the proteins in the extracts were separated on sodium dodecyl sulfate–polyacrylamide gel electophoresis, and collagen VII expression was assayed with the NC2-10 antibody.47 Mouse sera were used in a dilution of 1:10 to test their reactivity with collagen VII.

Fluorescence-activated cell sorting analysis for detection of EGFP+ cells in the blood circulation. Peripheral blood cells were treated with 0.15 mol/l NH4Cl/10 mmol/l KHCO3/0.1 mmol/l Na2EDTA pH 7.2 for 3 minutes to lyse erythrocytes and then washed with phosphate-buffered saline. A total of 1 × 105 cells were resuspended in 200 µl fluorescence-activated cell sorting buffer consisting of 2% fetal calf serum and 0.02% Na-azide in phosphate-buffered saline. Data were acquired on a FACScan and analyzed using the CellQuest Pro software (BD Biosciences). The percentage of EGFP+ cells was determined using a 488 nm laser for excitation and first fluorescence detector channel by placing a marker discriminating between EGFP− and EGPF+ cells based on mean fluorescence intensity. The detection limit was three EGFP+ fibroblasts in 1,000 peripheral blood cells from untreated animals, or 0.3%.

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIALFigure S1. EGFP+ fibroblasts in the dermis and active EGFP mRNA synthesis in the dermis. This graphic illustration summarizes the relation of EGFP+ fibroblasts and active EGFP mRNA expression in the skin. The X axis represents days after the second fibroblast injection, the Y axis depicts relative units for each parameter. Blue line: EGFP+ areas / cells in the dermis. To asses the amount of EGFP+ fibroblasts in the dermis, the surface of EGFP-positive dermis areas was measured and set in relation to total dermis surface in the same image. The maximal percentage of 15 %, found at day one after treatment, was set as the value of 1.0. Thereafter, the ratio of EGFP+ areas / total dermis area decreased. At day 28, almost no EGFP+ areas / cells were observed any more. Green line: EGFP mRNA expression in the skin (cf. also Figures 2 and 8). The maximal amount of EGFP mRNA found at 7 days was set as the value of 1.0. With time, the amount of EGFP mRNA gradually decreased, and after 28 days, no EGFP mRNA was found. The results show that EGFP+ cell numbers and EGFP mRNA expression correspond to each other, indicating that EGFP staining in the dermis is due to active protein synthesis by the injected fibroblasts.Figure S2. A 96 cytokine array of WT and collagen VII hypomorphic fibroblasts reveals no significant differences. Cytokine expression in collagen VII hypomorphic and control WT fibroblasts was determined by cytokine antibody arrays, which were performed in duplicates using cell extracts of WT (black columns) and collagen VII hypomorphic (white columns) fibroblasts. The relative spot intensities were determined by densitometry and normalized on the basis of background and positive control signals. Quantification of the relative expression levels of the 96 cytokines are shown in a-h. (a) Members of the interleukin family of cytokines and selected receptors. (b) CC-type chemokines. (c) Growth factors and other cytokines. (d) Receptor tyrosine kinases, adhesion molecules and matrix metalloproteases. (e) CXC-type chemokines. (f) Tumor necrosis factor (TNF) receptor superfamily members, their ligands and related proteins. (g) Growth factors and their binding proteins. (h) Other cytokines. There was no significant difference in 92 of the 96 cytokines tested. In collagen VII hypomorphic fibroblasts, the low affinity IgG receptor IIB (FcγRIIB) and platelet factor 4 (PF-4) were increased 2.1 and 3 fold, whereas insulin growth factor binding protein-2 (IGFBP-2) and basic fibroblast growth factor (bFGF) were decreased 1.8 and 2.3 fold, respectively. The downregulation of IGFBP-2 and of bFGF are not directly correlated to known signaling cascades downstream of collagen VII. Collectively, this demonstrates that the cytokine profiles of WT and collagen VII hypomorphic fibroblasts are very similar. Shown are means ± SD.Figure S3. No increase of TGF-β and CTGF expression after fibroblast injections. Skin treated with fibroblast injections was stained with antibodies to TGF-ß (a–c) and to CTGF (d–f). As a positive control, staining of paws of an 80 day-old collagen VII hypomorphic mouse are shown. The dermis with contractile fibrosis exhibits strong signals with both antibodies (a,d). In contrast, in areas of back skin injected with allogeneic fibroblasts, there was no significant expression of TGF- ß and CTGF, and no increase during the observation period from 7 days (b,e) to 21 days (c,f). These data indicate on one hand that TGF-ß or CTGF-mediated paracrine effects are not likely to play a major role in the synthesis of collagen VII after fibroblast injection. On the other hand they demonstrate that fibrosis is not induced by the therapeutic cells. Scale bar: 50 μm.Figure S4. Collagen VII synthesis in cultured human fibroblasts in correlation to age and passaging number. Fibroblast extracts were immunoblotted with collagen VII antibody NC2-10. Left panel: first-passage fibroblasts from a 5 year-old individual (5y, P1). Middle panel: tenth-passage fibroblasts from a 53 year-old individual (53y, P10). In both lanes, a similar collagen VII expression was seen, indicating that donor age or higher passaging of fibroblasts does not significantly affect collagen VII expression in these cells. Right panel: fibroblast extracts of a collagen VII deficient RDEB patient served as a negative control for the antibodies. The arrow points to the migration position of the approx. 290 kD procollagen VII molecule (CVII).

Supplementary Material

EGFP+ fibroblasts in the dermis and active EGFP mRNA synthesis in the dermis. This graphic illustration summarizes the relation of EGFP+ fibroblasts and active EGFP mRNA expression in the skin. The X axis represents days after the second fibroblast injection, the Y axis depicts relative units for each parameter. Blue line: EGFP+ areas / cells in the dermis. To asses the amount of EGFP+ fibroblasts in the dermis, the surface of EGFP-positive dermis areas was measured and set in relation to total dermis surface in the same image. The maximal percentage of 15 %, found at day one after treatment, was set as the value of 1.0. Thereafter, the ratio of EGFP+ areas / total dermis area decreased. At day 28, almost no EGFP+ areas / cells were observed any more. Green line: EGFP mRNA expression in the skin (cf. also Figures 2 and 8). The maximal amount of EGFP mRNA found at 7 days was set as the value of 1.0. With time, the amount of EGFP mRNA gradually decreased, and after 28 days, no EGFP mRNA was found. The results show that EGFP+ cell numbers and EGFP mRNA expression correspond to each other, indicating that EGFP staining in the dermis is due to active protein synthesis by the injected fibroblasts.

A 96 cytokine array of WT and collagen VII hypomorphic fibroblasts reveals no significant differences. Cytokine expression in collagen VII hypomorphic and control WT fibroblasts was determined by cytokine antibody arrays, which were performed in duplicates using cell extracts of WT (black columns) and collagen VII hypomorphic (white columns) fibroblasts. The relative spot intensities were determined by densitometry and normalized on the basis of background and positive control signals. Quantification of the relative expression levels of the 96 cytokines are shown in a-h. (a) Members of the interleukin family of cytokines and selected receptors. (b) CC-type chemokines. (c) Growth factors and other cytokines. (d) Receptor tyrosine kinases, adhesion molecules and matrix metalloproteases. (e) CXC-type chemokines. (f) Tumor necrosis factor (TNF) receptor superfamily members, their ligands and related proteins. (g) Growth factors and their binding proteins. (h) Other cytokines. There was no significant difference in 92 of the 96 cytokines tested. In collagen VII hypomorphic fibroblasts, the low affinity IgG receptor IIB (FcγRIIB) and platelet factor 4 (PF-4) were increased 2.1 and 3 fold, whereas insulin growth factor binding protein-2 (IGFBP-2) and basic fibroblast growth factor (bFGF) were decreased 1.8 and 2.3 fold, respectively. The downregulation of IGFBP-2 and of bFGF are not directly correlated to known signaling cascades downstream of collagen VII. Collectively, this demonstrates that the cytokine profiles of WT and collagen VII hypomorphic fibroblasts are very similar. Shown are means ± SD.

No increase of TGF-β and CTGF expression after fibroblast injections. Skin treated with fibroblast injections was stained with antibodies to TGF-ß (a–c) and to CTGF (d–f). As a positive control, staining of paws of an 80 day-old collagen VII hypomorphic mouse are shown. The dermis with contractile fibrosis exhibits strong signals with both antibodies (a,d). In contrast, in areas of back skin injected with allogeneic fibroblasts, there was no significant expression of TGF- ß and CTGF, and no increase during the observation period from 7 days (b,e) to 21 days (c,f). These data indicate on one hand that TGF-ß or CTGF-mediated paracrine effects are not likely to play a major role in the synthesis of collagen VII after fibroblast injection. On the other hand they demonstrate that fibrosis is not induced by the therapeutic cells. Scale bar: 50 μm.

Collagen VII synthesis in cultured human fibroblasts in correlation to age and passaging number. Fibroblast extracts were immunoblotted with collagen VII antibody NC2-10. Left panel: first-passage fibroblasts from a 5 year-old individual (5y, P1). Middle panel: tenth-passage fibroblasts from a 53 year-old individual (53y, P10). In both lanes, a similar collagen VII expression was seen, indicating that donor age or higher passaging of fibroblasts does not significantly affect collagen VII expression in these cells. Right panel: fibroblast extracts of a collagen VII deficient RDEB patient served as a negative control for the antibodies. The arrow points to the migration position of the approx. 290 kD procollagen VII molecule (CVII).

Acknowledgments

We thank Claudia Ehret, Käthe Thoma, Margit Schubert, Björn Wienke, and Josef Joos for expert technical assistance, and Eva Mangel for animal care, Armin Baur and Michael Reichel for sensor fabrication, and Philipp Esser for help with the FACS analyses. This work was supported in part by the Excellence Initiative of the German Federal and State Governments (Spemann Graduate School of Biology and Medicine, SGBM, The Center for Biological Signalling Studies, BIOSS; and Freiburg Institute for Advanced Studies, FRIAS, School of Life Sciences), by the Network Epidermolysis bullosa grant and the stem cell therapy for inherited skin fragility disorders grant from the Federal Ministry for Education and Research (BMBF), by Debra International, and by a Young Investigator Grant from the German Dermatological Society (DDG) to J.S.K. The authors have no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- Fritsch A, Loeckermann S, Kern JS, Braun A, Bösl MR, Bley TA, et al. A hypomorphic mouse model of dystrophic epidermolysis bullosa reveals mechanisms of disease and response to fibroblast therapy. J Clin Invest. 2008;118:1669–1679. doi: 10.1172/JCI34292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fine JD, Eady RA, Bauer EA, Bauer JW, Bruckner-Tuderman L, Heagerty A, et al. The classification of inherited epidermolysis bullosa (EB): Report of the Third International Consensus Meeting on Diagnosis and Classification of EB. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008;58:931–950. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2008.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kern JS., and , Has C. Update on diagnosis and therapy of inherited epidermolysis bullosa. Exp Rev Dermatol. 2008;3:721–733. [Google Scholar]

- Has C., and , Bruckner-Tuderman L. Molecular and diagnostic aspects of genetic skin fragility. J Dermatol Sci. 2006;44:129–144. doi: 10.1016/j.jdermsci.2006.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aumailley M, Has C, Tunggal L., and , Bruckner-Tuderman L. Molecular basis of inherited skin-blistering disorders, and therapeutic implications. Expert Rev Mol Med. 2006;8:1–21. doi: 10.1017/S1462399406000123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uitto J. Epidermolysis bullosa: prospects for cell-based therapies. J Invest Dermatol. 2008;128:2140–2142. doi: 10.1038/jid.2008.216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woodley DT, Keene DR, Atha T, Huang Y, Ram R, Kasahara N, et al. Intradermal injection of lentiviral vectors corrects regenerated human dystrophic epidermolysis bullosa skin tissue in vivo. Mol Ther. 2004;10:318–326. doi: 10.1016/j.ymthe.2004.05.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ortiz-Urda S, Thyagarajan B, Keene DR, Lin Q, Fang M, Calos MP, et al. Stable nonviral genetic correction of inherited human skin disease. Nat Med. 2002;8:1166–1170. doi: 10.1038/nm766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen M, Kasahara N, Keene DR, Chan L, Hoeffler WK, Finlay D, et al. Restoration of type VII collagen expression and function in dystrophic epidermolysis bullosa. Nat Genet. 2002;32:670–675. doi: 10.1038/ng1041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ortiz-Urda S, Lin Q, Green CL, Keene DR, Marinkovich MP., and , Khavari PA. Injection of genetically engineered fibroblasts corrects regenerated human epidermolysis bullosa skin tissue. J Clin Invest. 2003;111:251–255. doi: 10.1172/JCI17193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woodley DT, Krueger GG, Jorgensen CM, Fairley JA, Atha T, Huang Y, et al. Normal and gene-corrected dystrophic epidermolysis bullosa fibroblasts alone can produce type VII collagen at the basement membrane zone. J Invest Dermatol. 2003;121:1021–1028. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1747.2003.12571.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goto M, Sawamura D, Ito K, Abe M, Nishie W, Sakai K, et al. Fibroblasts show more potential as target cells than keratinocytes in COL7A1 gene therapy of dystrophic epidermolysis bullosa. J Invest Dermatol. 2006;126:766–772. doi: 10.1038/sj.jid.5700117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baldeschi C, Gache Y, Rattenholl A, Bouillé P, Danos O, Ortonne JP, et al. Genetic correction of canine dystrophic epidermolysis bullosa mediated by retroviral vectors. Hum Mol Genet. 2003;12:1897–1905. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddg200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meneguzzi G, Pin D, Carozzo C., and , Gache Y. Successful ex vivo gene therapy of recessive DEB. J Invest Dermatol. 2008;128:S124. [Google Scholar]

- Mavilio F, Pellegrini G, Ferrari S, Di Nunzio F, Di Iorio E, Recchia A, et al. Correction of junctional epidermolysis bullosa by transplantation of genetically modified epidermal stem cells. Nat Med. 2006;12:1397–1402. doi: 10.1038/nm1504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chino T, Tamai K, Yamazaki T, Otsuru S, Kikuchi Y, Nimura K, et al. Bone marrow cell transfer into fetal circulation can ameliorate genetic skin diseases by providing fibroblasts to the skin and inducing immune tolerance. Am J Pathol. 2008;173:803–814. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2008.070977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tolar J, Ishida-Yamamoto A, Riddle M, McElmurry RT, Osborn M, Xia L, et al. Amelioration of epidermolysis bullosa by transfer of wild-type bone marrow cells. Blood. 2009;113:1167–1174. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-06-161299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prockop DJ., and , Olson SD. Clinical trials with adult stem/progenitor cells for tissue repair: let's not overlook some essential precautions. Blood. 2007;109:3147–3151. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-03-013433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fine JD, Johnson LB, Weiner M, Li KP., and , Suchindran C. Epidermolysis bullosa and the risk of life-threatening cancers: the National EB Registry experience, 1986–2006. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2009;60:203–211. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2008.09.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kern JS, Kohlhase J, Bruckner-Tuderman L., and , Has C. Expanding the COL7A1 mutation database: novel and recurrent mutations and unusual genotype-phenotype constellations in 41 patients with dystrophic epidermolysis bullosa. J Invest Dermatol. 2006;126:1006–1012. doi: 10.1038/sj.jid.5700219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heinonen S, Männikkö M, Klement JF, Whitaker-Menezes D, Murphy GF., and , Uitto J. Targeted inactivation of the type VII collagen gene (Col7a1) in mice results in severe blistering phenotype: a model for recessive dystrophic epidermolysis bullosa. J Cell Sci. 1999;112:3641–3648. doi: 10.1242/jcs.112.21.3641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wong T, Gammon L, Liu L, Mellerio JE, Dopping-Hepenstal PJ, Pacy J, et al. Potential of fibroblast cell therapy for recessive dystrophic epidermolysis bullosa. J Invest Dermatol. 2008;128:2179–2189. doi: 10.1038/jid.2008.78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Konig A., and , Bruckner-Tuderman L. Transforming growth factor-beta stimulates collagen VII expression by cutaneous cells in vitro. J Cell Biol. 1992;117:679–685. doi: 10.1083/jcb.117.3.679. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roth W, Reuter U, Wohlenberg C, Bruckner-Tuderman L., and , Magin TM. Cytokines as genetic modifiers in K5−/− mice and in human epidermolysis bullosa simplex. Hum Mutat. 2009;30:832–841. doi: 10.1002/humu.20981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruther P, Bartholomeyczik W, Dominicus O, Roth K, Seitz W, Strauss A, et al. Proc IEEE Sensors 2005. Irvine, USA; 2005. Novel 3D piezoresistive silicon force sensor for dimensional metrology of micro components; pp. 1006–1009. [Google Scholar]

- Hinz B. Formation and function of the myofibroblast during tissue repair. J Invest Dermatol. 2007;127:526–537. doi: 10.1038/sj.jid.5700613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiquet-Ehrismann R., and , Chiquet M. Tenascins: regulation and putative functions during pathological stress. J Pathol. 2003;200:488–499. doi: 10.1002/path.1415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woodley DT, Remington J, Huang Y, Hou Y, Li W, Keene DR, et al. Intravenously injected human fibroblasts home to skin wounds, deliver type VII collagen, and promote wound healing. Mol Ther. 2007;15:628–635. doi: 10.1038/sj.mt.6300041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woodley DT, Keene DR, Atha T, Huang Y, Lipman K, Li W, et al. Injection of recombinant human type VII collagen restores collagen function in dystrophic epidermolysis bullosa. Nat Med. 2004;10:693–695. doi: 10.1038/nm1063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woodley D, Wang X, Zhou H, Wu T, Muirhead T., and , Chen M. Bone marrow stem cells improve the survivability of RDEB mice but do not correct the fundamental type VII collagen defect. J Invest Dermatol. 2008;128:S126. [Google Scholar]

- Fujita Y, Abe R, Inokuma D, Sasaki M, Hoshina D, Nishie W, et al. Bone marrow transplantation restores deficient epidermal basement membrane protein and improves the clinical phenotype in epidermolysis bullosa model mice. J Invest Dermatol. 2008;128:S114. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1000044107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kopp J, Horch RE, Stachel KD, Holter W, Kandler MA, Hertzberg H, et al. Hematopoietic stem cell transplantation and subsequent 80% skin exchange by grafts from the same donor in a patient with Herlitz disease. Transplantation. 2005;79:255–256. doi: 10.1097/01.tp.0000144325.01925.be. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gostynski A, Deviaene FC, Pasmooij AM, Pas HH., and , Jonkman MF.Adhesive stripping to remove epidermis in junctional epidermolysis bullosa for revertant cell therapy Br J Dermatol 2009. epub ahead of print [DOI] [PubMed]

- Remington J, Wang X, Hou Y, Zhou H, Burnett J, Muirhead T, et al. Injection of recombinant human type VII collagen corrects the disease phenotype in a murine model of dystrophic epidermolysis bullosa. Mol Ther. 2009;17:26–33. doi: 10.1038/mt.2008.234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bruckner-Tuderman L. Can type VII collagen injections cure dystrophic epidermolysis bullosa. Mol Ther. 2009;17:6–7. doi: 10.1038/mt.2008.262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fritsch A, Kern JS, Loeckermann S, Velati D, Fassler R., and , Bruckner-Tuderman L. Conditional Col7a1 inactivation allows analysis of anchoring fibril stability and function in vivo and reveals a major role of fibroblasts in collagen VII expression. J Invest Dermatol. 2009;129:S81. [Google Scholar]

- Tidman MJ., and , Eady RA. Evaluation of anchoring fibrils and other components of the dermal-epidermal junction in dystrophic epidermolysis bullosa by a quantitative ultrastructural technique. J Invest Dermatol. 1985;84:374–377. doi: 10.1111/1523-1747.ep12265460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beenken A., and , Mohammadi M. The FGF family: biology, pathophysiology and therapy. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2009;8:235–253. doi: 10.1038/nrd2792. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Firth SM., and , Baxter RC. Cellular actions of the insulin-like growth factor binding proteins. Endocr Rev. 2002;23:824–854. doi: 10.1210/er.2001-0033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin JL., and , Baxter RC. Expression of insulin-like growth factor binding protein-2 by MCF-7 breast cancer cells is regulated through the phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase/AKT/mammalian target of rapamycin pathway. Endocrinology. 2007;148:2532–2541. doi: 10.1210/en.2006-1335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martins VL, Vyas JJ, Chen M, Purdie K, Mein CA, South AP, et al. Increased invasive behaviour in cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma with loss of basement-membrane type VII collagen. J Cell Sci. 2009;122:1788–1799. doi: 10.1242/jcs.042895. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Wever O, Demetter P, Mareel M., and , Bracke M. Stromal myofibroblasts are drivers of invasive cancer growth. Int J Cancer. 2008;123:2229–2238. doi: 10.1002/ijc.23925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Echtermeyer F, Streit M, Wilcox-Adelman S, Saoncella S, Denhez F, Detmar M, et al. Delayed wound repair and impaired angiogenesis in mice lacking syndecan-4. J Clin Invest. 2001;107:R9–R14. doi: 10.1172/JCI10559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sat E, Leung KH, Bruckner-Tuderman L., and , Cheah KS. Tissue-specific expression and long-term deposition of human collagen VII in the skin of transgenic mice: implications for gene therapy. Gene Ther. 2000;7:1631–1639. doi: 10.1038/sj.gt.3301281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zaha V, Nitschke R, Göbel H, Fischer-Rasokat U, Zechner C., and , Doenst T. Discrepancy between GLUT4 translocation and glucose uptake after ischemia. Mol Cell Biochem. 2005;278:129–137. doi: 10.1007/s11010-005-7154-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caldelari R, Suter MM, Baumann D, De Bruin A., and , Müller E. Long-term culture of murine epidermal keratinocytes. J Invest Dermatol. 2000;114:1064–1065. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1747.2000.00960-4.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bruckner-Tuderman L, Nilssen O, Zimmermann DR, Dours-Zimmermann MT, Kalinke DU, Gedde-Dahl T, et al. Immunohistochemical and mutation analyses demonstrate that procollagen VII is processed to collagen VII through removal of the NC-2 domain. J Cell Biol. 1995;131:551–559. doi: 10.1083/jcb.131.2.551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

EGFP+ fibroblasts in the dermis and active EGFP mRNA synthesis in the dermis. This graphic illustration summarizes the relation of EGFP+ fibroblasts and active EGFP mRNA expression in the skin. The X axis represents days after the second fibroblast injection, the Y axis depicts relative units for each parameter. Blue line: EGFP+ areas / cells in the dermis. To asses the amount of EGFP+ fibroblasts in the dermis, the surface of EGFP-positive dermis areas was measured and set in relation to total dermis surface in the same image. The maximal percentage of 15 %, found at day one after treatment, was set as the value of 1.0. Thereafter, the ratio of EGFP+ areas / total dermis area decreased. At day 28, almost no EGFP+ areas / cells were observed any more. Green line: EGFP mRNA expression in the skin (cf. also Figures 2 and 8). The maximal amount of EGFP mRNA found at 7 days was set as the value of 1.0. With time, the amount of EGFP mRNA gradually decreased, and after 28 days, no EGFP mRNA was found. The results show that EGFP+ cell numbers and EGFP mRNA expression correspond to each other, indicating that EGFP staining in the dermis is due to active protein synthesis by the injected fibroblasts.