Abstract

Self-inactivating (SIN) lentiviruses flanked by the 1.2-kb chicken hypersensitive site-4 (cHS4) insulator element provide consistent, improved expression of transgenes, but have significantly lower titers. The mechanism by which this occurs is unknown. Lengthening the lentiviral (LV) vector transgene cassette by an additional 1.2 kb by an internal cassette caused no further reduction in titers. However, when cHS4 sequences or inert DNA spacers of increasing size were placed in the 3′-long terminal repeat (LTR), infectious titers decreased proportional to the length of the insert. The stage of vector life cycle affected by vectors carrying the large cHS4 3′LTR insert was compared to a control vector: there was no increase in read-through transcription with insertion of the 1.2-kb cHS4 in the 3′LTR. Equal amount of full-length viral mRNA was produced in packaging cells and viral assembly/packaging was unaffected, resulting in comparable amounts of intact vector particles produced by either vectors. However, LV vectors carrying cHS4 in the 3′LTR were inefficiently processed following target-cell entry, with reduced reverse transcription and integration efficiency, and hence lower transduction titers. Therefore, vectors with large insertions in the 3′LTR are transcribed and packaged efficiently, but the LTR insert hinders viral-RNA (vRNA) processing and transduction of target cells. These studies have important implications in design of integrating vectors.

Introduction

Chromatin insulator elements prevent spread of heterochromatin and silencing of genes, reduce chromatin position effects, and have enhancer-blocking activity, properties that are desirable for consistent predictable expression and safe transgene delivery with randomly integrating vectors.1,2,3 Overcoming chromatin position effects can reduce the number of copies required for a therapeutic effect and reduce the risk of genotoxicity of vectors.4 Vector genotoxicity has become an area of intense study since the occurrence of gene therapy related leukemia in patients in the X-linked severe combined immunodeficiency trials.5,6 γ-Retroviral (γ-RV) and lentiviral (LV) vectors have been modified to a self-inactivating (SIN) design to delete ubiquitously active enhancers in the U3 region of the long terminal repeats (LTRs).4,7,8,9 A 1.2-kb DNase chicken hypersensitive site-4 (cHS4) from the chicken β-globin locus, one of the best characterized chromatin insulator,10 has been inserted in the 3′LTR to allow its duplication into the 5′LTR in γ-RV and LV vectors. Insulated vectors have reduced chromatin position effects and, provide consistent, and therefore improved overall expression.11,12,13,14,15 We have done a side-by-side comparison of cHS4 insulated and uninsulated LV vectors carrying human β-globin and the locus control region (termed BG), and found that insulated vectors showed consistent, predictable expression, regardless of integration site in the differentiated progeny of hematopoietic stem cells, resulting in a two- to fourfold higher overall expression.14 Recent evidence also suggests that cHS4 insulated lentivirus vectors may also reduce the risk of insertional activation of cellular oncogenes.16,17

Despite the beneficial effects of insulated vectors, we and others have found a significant reduction in titers with insertion of the full-length 1.2-kb cHS4 insulator element in the 3′LTR of LV vectors.13,14 There are similar reports of lowering of viral titers or unstable transmission with γ-RV vectors containing insertions in the 3′LTR.18 This reduction in titers becomes practically limiting for scale up of vector production for clinical trials, especially with vectors carrying relatively large expression cassettes, such as BG, that have moderate titers even without insulator elements.

Although the field of virology has extensively studied deletions of various U3 and U5 sequences in the LTR to identify elements necessary for optimal viral production, the effects of insertions of exogenous fragments into the LTR on viral life cycle have not been addressed. In this study, we investigated the mechanism by which insertion of cHS4, or other inserts in the viral 3′LTR lower titers of LV vectors. Our results show that large LTR inserts lower titers via a postentry restriction in reverse transcription, and increased homologous recombination in the LTRs of viral complementary DNA, thus reducing the amount of vector DNA available for integration. These results have important implications for vector design for clinical gene therapy.

Results

Increased length of the vector genome by 1.2 kb does not affect viral titers

We explored whether reduction in titers by cHS4 was secondary to additional lengthening of the viral genomes in the otherwise large BG LV vector. Large viral-RNA (vRNA) genomes are known to be packaged less efficiently in integrating vectors.19,20 Replication competent γ-RV vectors delete added sequences and recombine to revert back to their original viral size.21 In γ-RV vectors that exceed the natural size of the virus, reduction in titers occurs at multiple steps of the viral life cycle—generation of full-length genome, viral encapsidation/release, and postentry recombination events.19 Notably, BG LV contain transgene inserts of ~7 kb, which is not larger than the natural size/packaging capacity of the wild-type human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)-1 virus. In LV vectors, however, lowering of viral titers from transgene inserts ≥6 kb has been shown to occur from reduced packaging efficiency.22

We have recently compared two uninsulated vectors BG and BGM with analogous insulated vectors BG-I and BGM-I for position effects.14 The BG lentivirus vector carries the hβ and locus control region, while a similar vector BGM additionally carries a phosphoglycerate kinase (PGK) promoter–driven methylguanine methyl transferase (P140K) cDNA (PGK-MGMT) insert downstream of BG. The PGK-MGMT cassette is 1.2 kb in size. The BG-I and BGM-I vectors carry the 1.2-kb cHS4 insulator in the 3′LTR in addition. Viral vector was produced from all four vectors and titered.14,15 The titers of the concentrated BG vector were 2 ± 0.5 × 108 IU/ml, while that of BGM, carrying an additional 1.2 kb internal cassette were slightly higher at 5 ± 0.8 × 108 IU/ml (n = 4). In contrast, addition of the 1.2-kb cHS4 in the 3′LTR to the BG vector, termed BG-I reduced titers by nearly sixfold to 3.8 ± 0.8 × 107 IU/ml. A further addition of a 1.2-kb PGK-MGMT internal cassette to the BG-I vector, termed BGM-I, did not reduce the titers any further. These data suggest that cHS4 insertion into the LTR, and not overall viral genome size reduced viral titers. Ramezani et al.13 observed a threefold reduction in LV vector titers when the 1.2-kb cHS4 was inserted in lentivirus vectors encoding relatively small transgene expression cassettes. Our data concur with their results, although we observed approximately six- to tenfold reduction in titers. We additionally observed that reduction in titers with the insulator occurred by a distinct mechanism that was not dependent on the increased size of the viral genome.

The size of the insert in the 3′LTR is responsible for reduction in titers

Although the LV vectors used did not exceed the natural size of the HIV-1 virus, the size of the cHS4 insert (1.2 kb) exceeded the natural size of the wild-type LTR (the wild-type LTR carries an additional 400-base pair (bp) U3 that is deleted in the SIN 3′LTR). We explored whether lowering of viral titers was due to lengthening of the LTR, or whether titers were lower due to specific sequences in the insulator. We constructed a series of BG LV vectors carrying different length fragments of cHS4 in the 3′LTR (Figure 1a): the first 250 bp of the insulator, also called the core, a 400- and a 800-bp cHS4 fragment, to generate sBGC, sBG400, sBG800 vectors, respectively. These vectors were compared to an analogous “uninsulated” vector, sBG, and a vector carrying the full-length 1.2-kb insulator, sBG-I. In addition, we also cloned a vector with two copies of the core as tandem repeats, sBG2C. The cHS4 core has been shown to have 50% of enhancer-blocking activity of the full-length insulator;23 with tandem repeats of cHS4 core reported to have the same insulating capacity as the full-length 1.2-kb cHS4 (ref. 24).

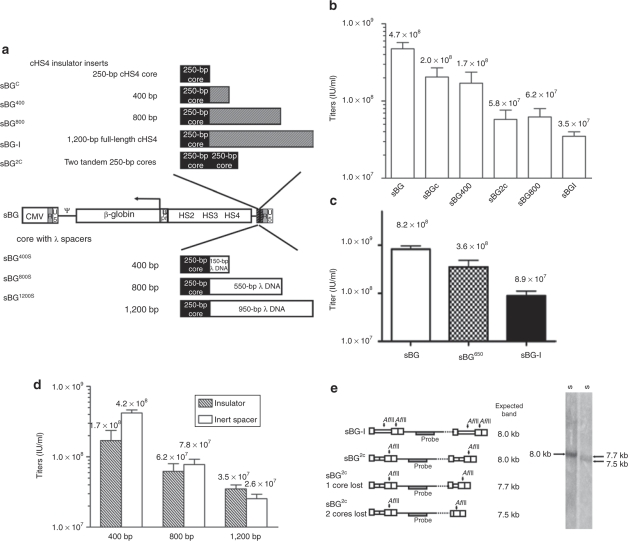

Figure 1.

Viral titers of LV vectors with inserts into the 3′LTR were inversely proportional to the length of the LTR insert. (a) Schematic representation of the LV vectors. All vectors were based on sBG, a SIN LV vector carrying the β-globin gene, β-globin promoter and the locus control region elements HS2, HS3, and HS4. Different fragments of the cHS4 site were inserted in the U3 region of the sBG 3′LTR (shown above the sBG vector). Similar-sized inserts were made by replacing the region downstream of cHS4 core with inert DNA spacers from the lambda phage DNA (shown below the sBG vector). (b) Viral titers of insulated vectors decreased as the length of the insulator insert increased. Titers reflect concentrated vector made concurrently for all vectors in each experiment (n = 4). All titers were significantly lower than the titers of the control vector sBG (P < 0.01; one-way analysis of variance). (c) A 650-bp sequence of cHS4, optimized for insulator activity through a structure–function analysis. A vector containing this 650-bp fragment (sBG650) was found to have approximately twofold lower titers than the uninsulated vector sBG (n = 3). (d) Titers fell with insertion of increasing length of an inert DNA spacer downstream of the core. Titers of insulated LV vectors (hatched bars) are similar to those containing inert DNA spacers in the LTR (open bar) in four independent experiments. The titers of sBG with a 400-bp spacer were slightly higher (*P < 0.05). (e) The sBG2C vector, carrying tandem repeats of the cHS4 core recombined with high frequency. A schematic representation of the vectors sBG-I and sBG2C proviruses, when intact, or when the core elements recombine with loss of one or two cores with the region probed and restriction site of the enzyme used (AflII) is shown. The size of the expected band is shown adjacent to each vector cartoon. The right panel is the Southern blot analysis showing a single 8 kb expected band for sBG-I transduced MEL cell population, and two bands in the sBG2C-transduced MEL cell population, representing sBG2C with either loss of one or both cores. cHS4, chicken hypersensitive site-4; CMV, cytomegalovirus; LTR, long terminal repeat; LV, lentiviral; MEL, mouse erythroleukemia; SIN, self-inactivating.

Viral vector was generated from sBG, sBGC, sBG400, sBG2C, sBG800, sBG-I plasmids concurrently, and titered by flow cytometry of mouse erythroleukemia (MEL), as described in ref. 14. Each experiment was replicated four times.

We found that as the size of the cHS4 insert in the 3′LTR increased, viral titers dropped (Figure 1b). There was a statistically significant reduction in titers with inserts of 250 and 400 bp. Titers fell sharply thereafter, proportional to the length of the insulator fragment (Figure 1b). The titers of the vector with a 1.2-kb full-length cHS4 insulator, sBG-I, were an order of magnitude lower than the uninsulated control, sBG. Of note, sBG2C vector, with a tandem repeat of two cHS4 core sequences (500-bp insert) had titers similar to sBG800.

To ensure that reduction in titers was not from specific cHS4 sequences but an effect of the size of the LTR insert, we constructed three additional vectors, sBG400-S, sBG800-S, and sBG1200-S that contained spacer elements from the Λ phage DNA downstream of the cHS4 core to generate 3′LTR inserts of 400 bp, 800 bp, and 1.2 kb, respectively (Figure 1a). The core cHS4 sequences were retained as the reduction in titers was minimal with the core; and we wanted to know whether additional sequences downstream of the core are necessary for optimal insulator activity. The titer of the vectors containing the 150-bp ΛDNA spacer was higher than the titer of the vector containing 400-bp insulator (P = 0.02), However, the 800-or 1,200 bp cHS4 sequences behaved similar to 550-and 950-bp ΛDNA inserts. There may be an effect of the 150-bp sequence either in ΛDNA or cHS4. But overall, the titers of 800-bp and 1.2-kb ΛDNA/cHS4 reduced titers in a similar fashion (Figure 1d). Taken together, these data show that lengthening of the insert in the 3′LTR primarily lowered titers, although specific sequences in the 400 bp of cHS4 could also have an effect.

In order to find a vector that would provide insulator activity, yet not lower titers, we performed a detailed structure–function analysis of the 1.2-kb cHS4 insulator. We have defined 650-bp sequences as the minimum necessary sequence for full insulation effect (P.I. Arumugam, F. Uribnati, V.S. Chinamenveni, T. Higashimoto, H.L. Grimes, and P. Malik, manuscript submitted). The 650-bp insert had lower, yet reasonable viral titers as shown in Figure 1c. The titers are two- to threefold lower titers than the uninsulated vector sBG, as compared to eight- to tenfold lower titers of sBG-I.

It has been reported that HIV-1 reverse transcriptase (RT) is not a strongly processive polymerase; it dissociates from its template frequently and the viral DNA is synthesized in relatively short segments.25 Therefore, it is likely that as the size of insert in the U3 LTR increased, there was reduced processivity through the 3′LTR. Previous studies have also shown that there is a spatial arrangement in the wild-type HIV LTR,26,27,28 which may be disrupted with the presence of inserts bigger than 400 bp in the U3 region of the LTR.

Recombination occurs with repeat elements in the 3′LTR

In order to detect whether recombination events occurred in the LTRs, we generated ~12–20 MEL cell clones transduced with the entire series of insulated vectors (sBGC, sBG400, sBG2C, sBG800, and sBG-I). All clones that had a single copy of proviral vector were identified using quantitative PCR (qPCR).14 Primers spanning the 250-bp core detected cHS4 in clones derived from all vectors except those derived from sBG2C-transduced cells. In sBG2C MEL clones, the insulator core was undetectable in 6 of 24 (25%) single-copy clones, suggesting deletion of both core sequences in the 5′ and 3′LTR of the proviral vector (Table 1). However, other recombination events, resulting in one remaining copy of cHS4 in either LTR could have also occurred. A genomic Southern blot analysis on sBG2C-transduced MEL cell pools was performed, by restricting with an enzyme that cut within the LTRs. Although a single proviral band was seen in sBG-I-transduced MEL cells, the sBG2C provirus in MEL cells showed loss of one or both copies of the cHS4 core sequences (Figure 1e). Indeed, proviral bands containing two intact copies of the core were not detected at the level of sensitivity of Southern blot analysis. Therefore, tandem repeats in sBG2C recombined at a high frequency, and recombination during reverse transcription may have lowered titers of this vector. These results were not unexpected, because repeat elements within γ-RV and LV vectors have been shown to recombine frequently.18,29,30

Table 1.

PCR for presence of 3′LTR inserts in proviruses derived from single-copy MEL clones shows stable transmission of all inserts except those present as tandem repeats

Steps in vector life cycle affected by large inserts into the 3′LTR

Next, we explored the mechanism by which this affected viral titers. We studied the following steps in the viral life cycle: (i) characteristics of vRNA in packaging cells, (ii) virus particle production, (iii) postentry steps: reverse transcription, nuclear translocation, integration, and proviral integrity. For these studies, we chose the vector with the largest insert, sBG-I, and compared it to the vector without the insulator, sBG.

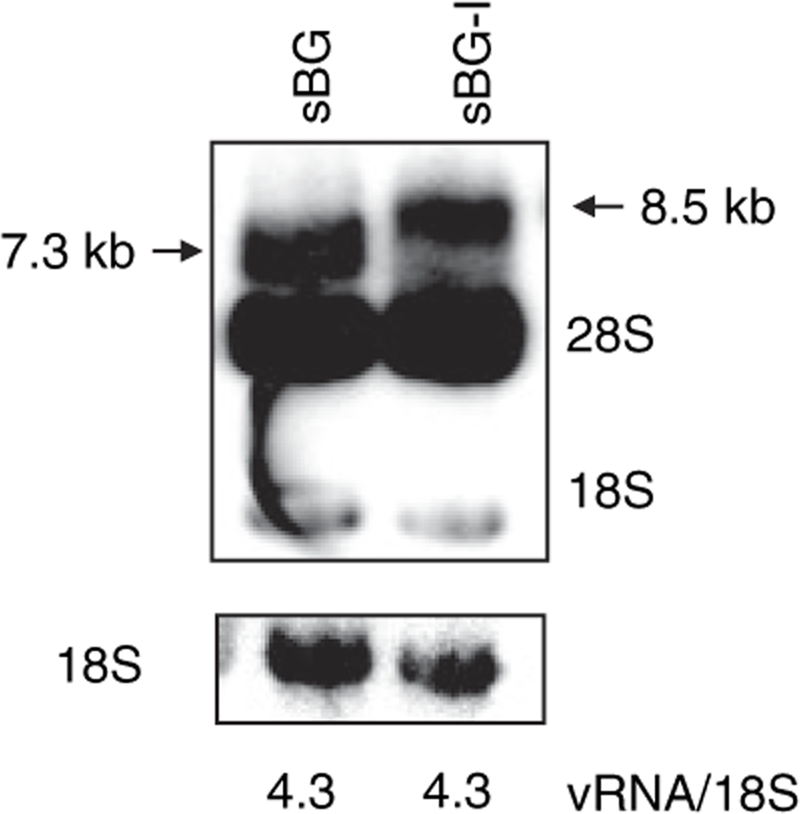

Insertion of cHS4 in the 3′LTR does not alter the quantity or quality of vRNA in packaging cells

Northern blot analysis was performed on RNA derived from the 293T packaging cells after transient transfection with sBG, sBG-I vector plasmids, along with packaging plasmids and probed with hβ fragment. Figure 2 shows similar intensity vRNA transcripts of the expected lengths of sBG and sBG-I vectors. This probe (and other probes in the vector (data not shown) nonspecifically probed the 28S and 18S RNA. Nevertheless, there were no additional bands other than the full-length vRNA of expected length, suggesting that no recombination/aberrant splicing occurred with insertion of the insulator and vRNA was produced efficiently regardless of an insert in the LTR.

Figure 2.

Similar amounts of viral RNA were produced from the insulated and uninsulated vectors in packaging cells. Northern blot analysis on the 293T packaging cells after transfection with sBG and sBG-I vectors showed the expected length viral RNA. The membrane was hybridized with a 32P-labeled β-globin probe (top panel) and 18S (bottom panel) as a loading control. An expected 7.3 and 8.5-kb band corresponds to sBG and sBG-I viral RNA were detected. The 18S and 28S rRNA were nonspecifically probed with this probe. No extraneous recombined bands were detected with either vector. The phosphoimager quantified ratios of viral RNA and 18S rRNA of both vectors are listed below the lanes and show no difference in the amount of vRNA between the two vectors.

We also determined whether the cHS4 insert upstream of the viral polyadenylation signal in the LTR could increase read-through transcription and lower viral titers.31,32 We33 and others32,34 have shown that transcriptional read-through in SIN γ-RV and LV vectors. Using a sensitive enzyme-based assay,33,34 we observed no increase in read-through transcription from the LTR (Supplementary Figure S1).

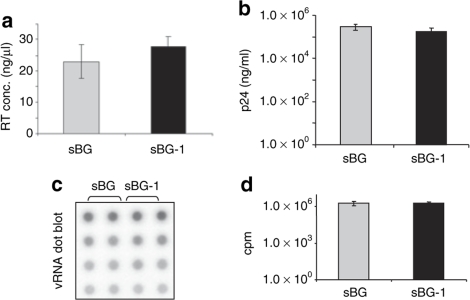

Production of viral particles containing viral genomes is not affected by cHS4

vRNA encapsidation efficiency was assessed by p24 levels, virus-associated RT activity and vRNA levels in virions (Figure 3a–c). Figure 4a shows that there was no difference in the amount virus-associated RT between the two vectors. The p24 levels in the sBG and sBG-I viral vectors preparation were also similar (Figure 3b). In order to ensure that sBG-I virions contained viral genomes, and were not empty viral-like particles, viral vector was subjected to RNA dot-blot analysis. Figure 3c,d shows one of two representative experiments. vRNA from sBG and sBG-I was loaded in duplicate in four different dilutions of p24 (Figure 3c,d). There were similar amounts of vRNA encapsidated from either vector. These data suggest that insertion of a 1.2-kb fragment in the LTR did not affect packaging efficiency of vRNA in viral particles.

Figure 3.

Vector production was not impaired by insertion of cHS4 in the 3′LTR. (a) Reverse transcriptase activity in sBG and sBG-I viral supernatants is similar (23 ± 5 versus 27 ± 3; n = 3, P > 0.5). (b) p24 levels detected in the concentrated viral preparation is the same with sBG and sBG-I. (2.9 ± 0.5 × 105 versus 1.7 ± 0.5 × 105; n = 3, P > 0.1). (c) Dot-blot analysis of viral RNA extracted from sBG and sBG-I viral supernatant shows similar amounts of viral RNA packaged into virions in both vectors. Note that four different dilutions of viral RNA were loaded in duplicate for the two vectors. The membrane was hybridized with a 32P-labeled β-globin probe. Only one of two representative experiments is shown. (d) Phosphoimager quantification of two independent experiments was plotted and showed similar amounts of viral RNA in sBG and sBG-I virions (1.9 ± 0.7 × 106 versus 1.9 ± 0.6 × 106; n = 2, P > 0.5). cHS4, chicken hypersensitive site-4; cpm, counts per minute; LTR, long terminal repeat; RT conc., reverse transcriptase concentration; vRNA, viral RNA.

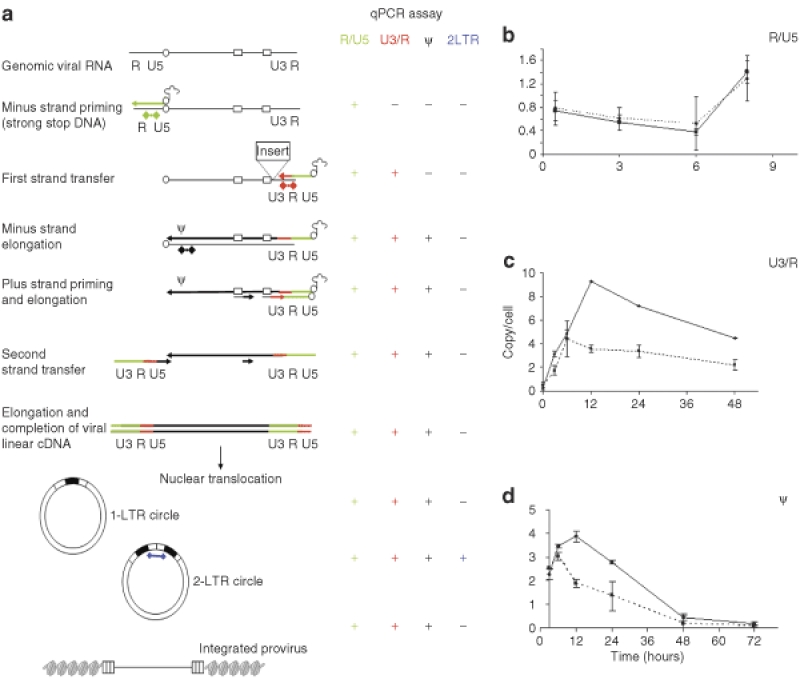

Figure 4.

Kinetic of reverse transcription and nuclear translocation in lentivirus vector carrying insulator element in the LTR. (a) Schema of the LV reverse transcription and nuclear translocation process are illustrated. On the right a summary of qPCR assays performed to analyze several steps of the process. Thin line: RNA; thick line: DNA. Open boxes: polypurine tract (PPT). Open circle: primer-binding site (pBS). The 3′ LTR DNA insert is illustrated in the first strand transfer diagram. The positions of the qPCR assays are shown. DNA from MEL cells after infection with sBG and sBG-I viral vector was collected at different time points after infection and analyzed by qPCR. Solid line: sBG. Dashed line: sBG-I. (b) Kinetic of reverse transcription before the first strand transfer (R/U5) shows no difference between the two vectors. (c,d) After the first strand transfer (U3/R and ψ) there is a decrease in reverse transcription efficiency in presence of the insulator (n = 3). cDNA, complementary DNA; LTR, long terminal repeat; qPCR, quantitative PCR.

Our results with large inserts into the LTR are in contrast to those by Sutton et al. where LV vectors with lengthened internal transgene cassettes are inefficiently packaged into virions.22 Equal amounts of vector particles produced from the sBG and sBG-I vectors, but significantly lower infectious/transduction titers suggests a postentry block of large LTR insert–bearing vectors, resulting in less integrated units.

Large LTR inserts affect reverse transcription and integration of viral cDNA

We next investigated viral postentry steps, i.e., reverse transcription, nuclear translocation, integration, and proviral integrity. The steps of reverse transcription, location of qPCR primers and probes and the viral DNA products are summarized in Figure 4a. Reverse transcription initiates from the primer-binding site near the 5′ end of the genomic RNA, and minus-strand synthesis proceeds to the 5′ end of the genome (minus-strand strong stop DNA (−sssDNA)). The newly formed −sssDNA anneals to the 3′R region of the genome (first strand transfer), minus-strand DNA synthesis resumes, accompanied by RNase H digestion of the vRNA template. It has been shown that the secondary structure of vRNA at the 3′ end is a critical determinant for the −sssDNA transfer, for the reverse transcription process to be efficient.26,27,28,35,36 Therefore, it is likely that presence of the insulator/an insert in the U3 region of the 3′ LTR would alter the secondary structure of the region involved in this complex process, resulting in overall decreased reverse transcription efficiency. We performed bioinformatics analysis of the insulator sequences using the software M-fold37 (mfold.bioinfo.rpi.edu) that predict secondary structures of RNA sequences. As expected, the insulator has been predicted to form complex secondary structure with numerous loops that could indeed interfere with the reverse transcription process.

MEL cells were infected with equal amounts of sBG and sBG-I viral particles, and cells were collected at different time points postinfection. Kinetics of early reverse transcription (production of −sssDNA) were studied using primers and probe spanning the R/U5 region (Figure 4b). As expected, we did not detect any difference between the two viral vectors, because the 5′ ends of sBG or sBG-I vRNA were identical. Nevertheless, the data validated that qPCR accurately determined viral reverse transcription.

It is conceivable, however, that when RT switches templates (minus-strand jump) to reverse transcribe the 3′ LTR, alteration of secondary structure from the presence of an insert in the U3 region would reduce reverse transcription products. Amplification of the U3/R and ψ regions by qPCR was done to quantify the intermediate and late reverse transcribed viral cDNA, respectively (Figure 4c,d). We found that RT efficiency soon after the first strand transfer was impaired. Notably, the U3/R primers amplified viral DNA that was reverse transcribed before the insulator sequences, suggesting that insert in the 3′LTR affected reverse transcription by altering or “poisoning” the 3′LTR. Indeed, the inefficiency in intermediate RT product formation was similar to that seen with late RT products. In both analysis, the peak of viral cDNA synthesis occurred at 12 hours for the uninsulated vector sBG and then gradually decreased, consistent with integration of viral cDNA, and previously reported.38 The amount of viral DNA from the insulated vector sBG-I was lower postentry compared to sBG by approximately twofold at all time points, as early as 6 hours post-target cell entry. These data strongly suggest that reverse transcription after the minus-strand jump was rate limiting in the sBG-I vector.

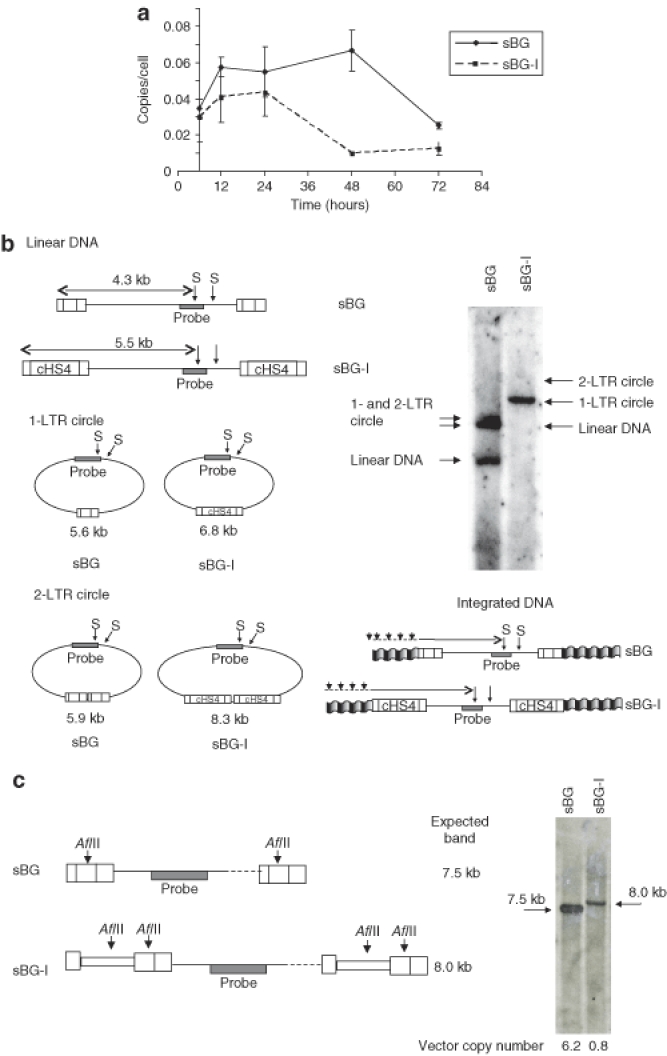

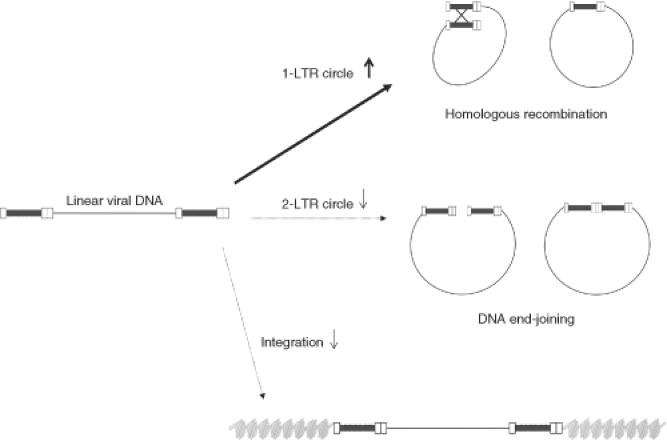

Nuclear translocation. After the viral DNA is synthesized in the cytoplasm, it is translocated into the nucleus of infected cells, where it can be found as linear DNA or circular DNA (1-LTR and 2-LTR circles) (Figure 4a). The linear form is circularized at the LTRs and is the direct precursor of the integration process; 1-LTR and 2-LTR circles, instead, are abortive products of homologous recombination and nonhomologous DNA end-joining, respectively. However, 1-LTR and 2-LTR circles are specifically localized in the nucleus, and are used as a marker for nuclear translocation.39,40,41 Presence of an insert in the LTR can possibly interfere with the preintegration complex formation and the nuclear translocation. Preintegration complexs bind HIV LTR in the cytoplasm and are responsible for the transport to the nucleus and the integration of the cDNA into the genome of infected cells.42,43 In order to detect the nuclear translocation, we analyzed the amount of 2-LTR circles using a qPCR on DNA from infected MEL cells at different time points in sBG versus sBG-I infected cells. The amounts of 2-LTR circles were not significantly different between the two vectors at early time points (Figure 5a). However, at 48 hours after infection, the peak at which 2-LTR circles are normally detected,38 2-LTR circles were 6.7 times higher in sBG infected cells, but were barely at the detection limit in sBG-I infected cells. We also analyzed at later time points (72 and 96 hours), but found no delay in the kinetics of 2-LTR circle formation in the insulated vectors. Indeed, the 2-LTR circles were barely detectable by qPCR in the sBG-I infected cells after 24 hours. These data suggested that nuclear translocation was likely reduced due to presence of the large U3 insert.

Figure 5.

Insertion of cHS4 in the LTR affected viral integration. Linear viral cDNA circularizes and is the form that integrates; 1-LTR and 2-LTR circles represent abortive integration products from homologous recombination and nonhomologous end-joining, respectively. The 1-LTR and 2-LTR circles are therefore used as markers of nuclear translocation. (a) There are reduced 2-LTR circles, analyzed by qPCR on DNA extracted from MEL cells infected at different times after infection with viral vector suggesting reduced nuclear translocation or nonhomolgous end-joining. (b) Southern blot analysis of MEL cells 72 hours after infection with same amount of sBG and sBG-I vector. StuI digestion of genomic DNA allows identification of 1-LTR circles, 2-LTR circles, linear DNA, and integrated DNA (a smear) for sBG and sBG-I. Expected band sizes are shown for both vectors. While linear, 1-LTR and 2-LTR circles are seen in the sBG lane, no linear DNA or 2-LTR circles are detected in the sBG-I lane. However, 1-LTR circles are almost as prominent as in the sBG lane. The relative ratios of linear, 1-LTR and 2-LTR circles suggest increased recombined abortive integration products with the sBG-I vector, and hence result in inefficient integration. (c) sBG- and sBG-I-transduced MEL cells show intact proviral integrants (7.5 and 8.0 kb, respectively). There was an eightfold difference in phosphoimager counts of the two bands. Vector copy number per cell was also quantified by qPCR and is depicted below the lanes. cDNA, complementary DNA; cHS4, chicken hypersensitive site-4; LTR, long terminal repeat; MEL, mouse erythroleukemia; qPCR, quantitative PCR.

It is also conceivable, however, that two copies of large U3 inserts provide a template for homologous recombination, and higher homologous recombination results in more 1-LTR circles and reduced 2-LTR circles (as proposed in the cartoon in Figure 6), decreasing the template available for integration. Due to the nature of reverse transcribed viral cDNA with an insulated and uninsulated vector, 1-LTR circles cannot be quantified by a PCR-based technique. We therefore performed a Southern blot analysis to detect linear viral cDNA, 1-LTR, and 2-LTR circles at 72 hours postinfection with equal amounts of sBG and sBG-I (quantified using p24 levels) (Figure 5b). The Southern blot analysis showed that (i) the linear form of reverse transcribed viral cDNA, the form that integrates, was undetectable in the sBG-I lane at the sensitivity of Southern blot analysis, while it was readily detectable in the sBG lane. (ii) The 2-LTR circles were also undetectable in the Southern analysis in the sBG-I lane, but detectable in the sBG lane, corroborating the qPCR data on 2-LTR circles. (iii) However, large amount of 1-LTR circles were present in sBG-I lane, similar in amount to those seen in the sBG lane. The relative ratios of linear, 1-LTR and 2-LTR circles in sBG versus sBG-I lanes suggested that there was increased homologous recombination of the sBG-I viral DNA. Indeed, these data indicated that nuclear translocation was not affected to any major extent by the U3 insert. But after the reverse transcribed cDNA entered the nucleus, increased 1-LTR circles, representing abortive recombinant integration products were formed due to the large LTR insert. Therefore, integration was reduced.

Figure 6.

Hypothesis of mechanism by which insulator sequence decrease viral titer. In wild-type HIV, linear cDNA molecules translocate to the nucleus where a small percentage undergoes recombination and end-joining ligation to form 1-LTR and 2-LTR circles, respectively. Only the linear form is the immediate precursor to the integrated provirus. In the case of insulated LV vectors, we show an increase in 1-LTR circle formation, probably due to the presence of a larger U3 sequence that could facilitate an increase in homologous recombination. This process depletes the amount of viral DNA available for integration as well as the amount of 2-LTR circle formation. The decreased amount of DNA available for integration could explain the loss in titers for LV vector carrying large inserts in the LTR. cDNA, complementary DNA; LTR, long terminal repeat; LV, lentiviral.

It is conceivable that the integration machinery is also affected by the presence of foreign sequences in the LTR. Therefore, we packaged sBG and sBG-I vectors using an integrase defective packaging plasmid, so that effect of the insulator on reverse transcription, nuclear localization, and 1-LTR circle formation could be studied independent of integration. We performed the same analysis as with active integrase containing viral vectors: a qPCR to study the late reverse transcription products, 2-LTR circles; and a genomic Southern blot to determine 1-LTR circles and viral cDNA forms. The results were identical to those seen with sBG and sBG-I packaged with active integrase (shown in Figure 5b; data not shown). Therefore, sequences inserted into the lentivirus LTR interfered mainly with the reverse transcription process, and increased the frequency of homologous recombination by a mechanism independent of the integrase machinery.

Finally, we analyzed the integrated sBG and sBG-I proviral vector for stability of transmission and efficiency of integration. The Southern blot analysis in Figure 5b shows the integrated DNA as a smear, which is of higher intensity in the sBG than the sBG-I lane. In order to confirm and quantify integration, MEL cells were transduced with same amount of p24 levels of sBG or sBG-I vector, cultured for 21 days and a qPCR and Southern blot analysis were performed (Figure 5c). There were 6.2 proviral copies/cell in sBG MEL cell population by qPCR, while only 0.8 proviral copies were detected in sBG-I MEL cells, an eightfold difference, which is consistent with differences seen in transduction titers between the two vectors. Next, DNA was restricted with AflII, an enzyme that cuts within the LTRs (Figure 5c, left panel). Consistent with transduction titers and qPCR, the amount of integrated sBG-I proviral vector was eightfold less than sBG (Figure 5c). The sBG-I vector did not recombine, as shown by the single proviral band of the expected size. Additionally, we were able to detect the full-length insulator by PCR in all single-copy clones of sBG-I-transduced MEL cells (Table 1). Therefore, the linear sBG-I cDNA, albeit inefficiently formed, integrated as an intact provirus.

Discussion

Because insulators are important for generating viral vectors that would be safe and provide consistent predictable expression, we attempted to find a solution to the problem of low viral titers with insulated viral vectors. One way to overcome the problem would be to flank the internal expression cassette with cHS4 on either end, because further lengthening of the internal cassette did not decrease titers. However, repeat elements within RV are known to result in recombination.18,29,30

We are confident that the sBG650 vector can be scaled up for clinical trials, based upon unconcentrated titers of ~5–6 × 105 IU/ml. For example, for a 50-kg patient, where a 4 × 106 CD34+ cells/kg are transplanted, one would need 2 × 108 CD34+ cells transduced at a multiplicity of infection of 10 for 75% transduction efficiency.15 This would then require 2 × 109 IU of vector particles/patient, which would translate to 4-l unconcentrated vector/patient (assuming a vector titer of 5 × 105 IU/ml). A 60-l preparation for a phase I/II clinical trial would result in 30 × 109 infectious vector particles. This volume is routinely processed in vector production facilities that produce cyclic guanosine monophosphate grade vectors. Indeed, a current Good Manufacturing Practices (cGMP) production of 150 l for a lentivirus vector for the X-linked severe combined immunodeficiency trial was done, at public presentation of this trial in the recent Recombinant DNA Advisory Committee meeting: (http://oba.od.nih.gov/rdna_rac/rac_past_meetings_2000.html#RAC2009). Alternative insulators that of smaller size may help further improve titers.

In summary, herein we studied the mechanism by which inserts into LV 3′LTR reduce viral titers. We showed that the low transduction titers were specifically due to increased length of the 3′LTR. The quantity and quality of vRNA were unaffected and vRNA encapsidation/packaging was comparable in vectors with and without a 1.2 kb LTR insert. Reduced viral titers occurred from postentry steps, from inefficient reverse transcription, increased homologous recombination in the LTR of viral DNA, making less viral DNA available for integration. We also performed improvements in vector design, by including smaller insulator inserts with essential insulator elements.

With the generation of SIN vectors, insertions into the LTR have extended beyond flanking expression cassettes with insulators to the inclusion of enhancers of polyadenylation/transcript termination32,33, and replacement of ubiquitous viral enhancers with lineage-specific enhancers in the 3′LTR.44 Others have placed promoter–transgene cassettes in the 3′LTR to achieve double-copy vectors.18,45,46,47,48 Our studies, therefore, have important implications for future design of vectors with inserts within the 3′LTR, given the usefulness of chromatin insulator elements, customized lineage-specific LTR vectors or double-copy vectors.

Materials and Methods

Vector constructs. All vectors carried the human β-globin gene and the hypersensitive site 2, 3, and 4 fragments (BG), as previously described.15 The cloning of the BG, BGM, BG-I, and BGM-I vectors has been previously described.14 All the vectors were obtained cloning the different insulator fragments into a unique NheI/EcoRV site inserted in the U3 3′LTR region of the LV vector plasmid. Insulator fragments were amplified by PCR using the pJCI3-1 as a template (kindly provided by Gary Felsenfeld (National Institute of Health, Bethesda, MD) and amplicons sequenced following the PCR, and after insertion into the 3′LTR. sBG-I was cloned by cloning the XbaI fragment from from pJC13 into the NheI/EcoRV restriction site of sBG. sBGC was cloned inserting into sBG vector the fragment EcoRI/XbaI containing the 250-bp core from the primer-binding site (pBS)-1 core plasmid. The latter was obtained cloning the 250-bp core Insulator PCR product (using Core 1F and Core 1R primers, Table 2) into BamHI/EcoRI restriction sites of a pBS plasmid. A second copy of the 250-bp core was then added into the pBS-1 core plasmid, cloning into EcoRI/KpnI sites the PCR product (Core 2F and Core 2R), obtaining the pBS-2 core plasmid. Two tandem copies of the 250-bp core were then isolated digesting the latter plasmid with KpnI/XbaI, and then cloned into the sBG vector, obtaining sBG2C. The sBG400 and sBG800 vectors were obtained cloning the two PCR products (using InsF and Ins400R primers and InsF and Ins800R primers, respectively) into the sBG NheI/EcoRV sites. sBG650 vector was obtained cloning the 3′ 400 fragment of the insulator in EcoRV/BspEI sites of sBG1c vector. The 3′ 400 fragment was PCR amplified from the plasmid pJCI3-1 using the following primers: 3′ 400 R (BspEI) and 3′ 400 F (EcoRV) (see Table 2). The vectors containing the ΛDNA spacers were obtained amplifying different size Λ phage DNA using the following primer combinations: spacerF1 and spacerR1, spacerF1 and spacerR2, and spacerF1 and spacerR3 amplifying a 150-, 550-, and 950-bp ΛDNA fragments, respectively. The three PCR fragments were digested with ClaI and EcoRI restriction enzymes and ligated into EcoRI/ClaI sites in the pBS-1 core plasmid, The 400-, 800-, and 1,200-bp fragments were digested from the pBS-1 core plasmid with HincII and XbaI for the 400-bp fragment, and with XbaI and XhoI for the remaining two fragments, and cloned into the EcoRV/NheI restriction sites in the sBG vector. All the vectors cloned were confirmed by sequencing. The list of all the primers is available in Table 2.

Table 2.

PCR primers

Cell lines. MEL cell line and 293T cells were maintained in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (Mediatech, Manassas, VA) supplemented with 10% heat inactivated fetal bovine serum (US Bio-technologies, Parker Ford, PA). MEL cells were induced to differentiate in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium containing 20% fetal bovine serum and 5 mmol/l N,N′-hexamethylene bisacetamide (Sigma, St Louis, MO), as previously described.14 Single-copy clones were identified by qPCR for lentivirus ψ-sequences, and a PCR for the cHS4 core sequences was performed to confirm presence of insulator sequences in the provirus.

Adult hemoglobin staining and fluorescence-activated cell-sorter scanner analysis. The staining using the antihuman adult hemoglobin antibody was as previously described.15

Vector production. Vector was produced by transient cotransfection of 293T cells, as previously described,49 using the vector plasmids, the packaging (Δ8.9 or Δ8.2 for active or inactive integrase, respectively) and the vesicular stomatitis virus glycoprotein envelope plasmids; vector-containing supernatant was collected at 60 hours after transfection and concentrated by ultracentrifugation. To ensure purity of viral particles, vector was filtered through a 0.45-µm filter and concentrated over a sucrose gradient and subjected to DNase digestion. Lack of plasmid contamination was confirmed by a qPCR for the ampicillin-resistance gene present in the plasmid backbone. Vector was concentrated 1,400-fold from all viral supernatants after ultracentrifugation at 25,000 rpm for 90 minutes. Viral titers were determined by infecting MEL cells with serial dilutions of concentrated vector, differentiating them, and analyzing them for HbA expression by fluorescence-activated cell-sorter scanner.

Northern blot. Total RNA was extracted from 293T cells using RNA-STAT (Tel-Test, Friendswood, TX), 72 hours after transfection. Northern blot was then performed according to standard protocol. The blot was hybridized with a 32P-labeled β-globin probe. A film was exposed and developed after 48 hours. A phosphoimager screen was then exposed for 1 hour to quantify the intensity of the bands (Biorad, Hercules, CA).

RNA dot blot. vRNA was extracted from same volumes of concentrated viral vectors using the QIAamp Viral RNA Mini Kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA) following the manufacturer's instructions. After elution vRNA was treated for 20 minutes at room temperature with amplification grade DNase I (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). DNase was inactivated incubating the sample at 65 °C. vRNA was then denatured in three volumes of denaturation buffer (65% formamide, 8% formaldehyde, 3-(N-morpholino)propanesulfonic acid 1×) for 15 minutes at 65 °C. After denaturation, two volumes of ice-cold 20× saline–sodium citrate were added and the RNA was bound to a nylon membrane by aspiration through a dot-blot apparatus. The blot was hybridized with a 32P-labeled β-globin specific probe and a film was exposed overnight. Quantification of the dots was performed with a phosphoimager (Biorad).

RT assay. Concentrated vector (1 µl), and serial dilutions (1:10, 1:100, 1:1,000) were lysed and processed following the “Reverse transcriptase (RT) assay, colorimetric” Kit (Roche, Basel, Switzerland) protocol.

p24 Assay. p24 Antigen concentration was determined by HIV-1 p24 Antigen EIA Kit (Beckman Coulter, Fullerton, CA), following manufacturer's protocol.

Southern blot. To analyze the integrity of the proviral vector we infected MEL cells, expanded them for 21 days, and extracted DNA using Qiagen Blood and Cell culture DNA Mini Kit (Qiagen). DNA (10 µg) was digested with AflII. To determine presence of viral linear DNA, genomic DNA was extracted 72 hours after infection of MEL cells and restricted with StuI, The DNA was separated on a 0.8% agarose gel, transfer to a nylon membrane, and probed overnight with a β-globin fragment.

Real-time PCR for RT products and 2-LTR circle. Same amount of p24 were used to transduce MEL cells with sBG and sBG-I vectors, in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium, in the presence of 8 µg/ml polybrene. Cells were harvested at different time point (0.5, 3, 6, 8, 12, 24, 48, and 72 hours) and DNA extracted using Qiagen Blood and Cell culture DNA Mini Kit (Qiagen). Genomic DNA (50 ng) from a single-copy MEL clone (confirmed by Southern for a single integrant) was diluted with untransduced DNA to generate copy number standards (1–0.016 copies/cell). The primers and the probe for RT product were designed using the Primer Express Software from Applied Biosystems (Foster City, CA). Primers and probe sequence for early RT products (R/U5) qPCR assay are: forward primer 5′-GAACCCACTGCTTAAGCCTCAA-3′, reverse primer: 5′-ACAGACGGGCACACACTACTTG-3′. The reaction was carried out with TaqMan MGB probe: 5′-AAAGCTTGCCTTGAGTGC-3′. Primers and probe sequence for intermediate RT products (U3/R) qPCR assay are: forward primer 5′-CCCAGGCTCAGATCTGGTCTAA-3′, reverse primer: 5′-TGTGAAATTTGTGATGCTATTGCTT-3′. The reaction was carried out with TaqMan MGB probe: 5′-AGACCCAGTACAAGCAAAAAGCAGACCGG-3′. For the late RT product assay (ψ) the primers were designed to recognize the ψ region of the provirus: forward primer: 5′-ACCTGAAAGCGAAAGGCAAAC-3′, reverse primer: 5′ AGAAG GAGAGAGATGGGTGCG-3′. The reaction was carried out with TaqMan probe: 5′-AGCTCTCTCGACGCAGGACTCGGC-3′ with TAMRA dye as quencher. Normalization for loading was carried out using mouse apoB gene controls. The cycling conditions were 2 minutes at 50 °C and 10 minutes at 95 °C, then 40 cycles of 95 °C for 15 seconds and 60 °C for 1 minute. The primers and probe for 2-LTR circle were as previously described.50 The PCR mix was thermo cycled according to the thermal cycler protocol for 96-well plates in Applied Biosystems 7900HT Fast Real-Time PCR System.

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIALFigure S1. Viral RNA read-through transcription was not increased with a large insert in the 3′LTR. (A) Plasmid constructs containing varying LTRs down stream of a promoter were designed with β-galactosidase gene inserted downstream of the LTR. The latter would be transcribed in case read-through transcription occurred. (B) Read-through transcription from the SIN-LTR with cHS4 insert was negligible and comparable to the wt HIV LTR and the SIN HIV LTR. β-galactosidase enzyme activity was measured by spectrophotometer, and enzyme activity was normalized for transfection efficiency. (n=3) (C) β-galactosidase staining confirmed results seen with the enzyme assay and was also performed on TE-26 cells after transfection.

Supplementary Material

Viral RNA read-through transcription was not increased with a large insert in the 3′LTR. (A) Plasmid constructs containing varying LTRs down stream of a promoter were designed with β-galactosidase gene inserted downstream of the LTR. The latter would be transcribed in case read-through transcription occurred. (B) Read-through transcription from the SIN-LTR with cHS4 insert was negligible and comparable to the wt HIV LTR and the SIN HIV LTR. β-galactosidase enzyme activity was measured by spectrophotometer, and enzyme activity was normalized for transfection efficiency. (n=3) (C) β-galactosidase staining confirmed results seen with the enzyme assay and was also performed on TE-26 cells after transfection.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by National Institute of Health grants U54-HL070595, RO1-HL70135, P01-HL073104, and U54 HL06-008.

REFERENCES

- Rivella S, May C, Chadburn A, Rivière I., and , Sadelain M. A novel murine model of Cooley anemia and its rescue by lentiviral-mediated human β-globin gene transfer. Blood. 2003;101:2932–2939. doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-10-3305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Persons DA, Hargrove PW, Allay ER, Hanawa H., and , Nienhuis AW. The degree of phenotypic correction of murine β-thalassemia intermedia following lentiviral-mediated transfer of a human gamma-globin gene is influenced by chromosomal position effects and vector copy number. Blood. 2003;101:2175–2183. doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-07-2211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Imren S, Payen E, Westerman KA, Pawliuk R, Fabry ME, Eaves CJ, et al. Permanent and panerythroid correction of murine β thalassemia by multiple lentiviral integration in hematopoietic stem cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002;99:14380–14385. doi: 10.1073/pnas.212507099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Modlich U, Bohne J, Schmidt M, von Kalle C, Knöss S, Schambach A, et al. Cell-culture assays reveal the importance of retroviral vector design for insertional genotoxicity. Blood. 2006;108:2545–2553. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-08-024976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thrasher AJ, Gaspar HB, Baum C, Modlich U, Schambach A, Candotti F, et al. Gene therapy: X-SCID transgene leukaemogenicity. Nature. 2006;443:E5–6; discussion E6. doi: 10.1038/nature05219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hacein-Bey-Abina S, Von Kalle C, Schmidt M, McCormack MP, Wulffraat N, Leboulch P, et al. LMO2-associated clonal T cell proliferation in two patients after gene therapy for SCID-X1. Science. 2003;302:415–419. doi: 10.1126/science.1088547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zufferey R, Dull T, Mandel RJ, Bukovsky A, Quiroz D, Naldini L, et al. Self-inactivating lentivirus vector for safe and efficient in vivo gene delivery. J Virol. 1998;72:9873–9880. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.12.9873-9880.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miyoshi H, Blömer U, Takahashi M, Gage FH., and , Verma IM. Development of a self-inactivating lentivirus vector. J Virol. 1998;72:8150–8157. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.10.8150-8157.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kraunus J, Schaumann DH, Meyer J, Modlich U, Fehse B, Brandenburg G, et al. Self-inactivating retroviral vectors with improved RNA processing. Gene Ther. 2004;11:1568–1578. doi: 10.1038/sj.gt.3302309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Felsenfeld G, Burgess-Beusse B, Farrell C, Gaszner M, Ghirlando R, Huang S, et al. Chromatin boundaries and chromatin domains. Cold Spring Harb Symp Quant Biol. 2004;69:245–250. doi: 10.1101/sqb.2004.69.245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rivella S, Callegari JA, May C, Tan CW., and , Sadelain M. The cHS4 insulator increases the probability of retroviral expression at random chromosomal integration sites. J Virol. 2000;74:4679–4687. doi: 10.1128/jvi.74.10.4679-4687.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emery DW, Yannaki E, Tubb J, Nishino T, Li Q., and , Stamatoyannopoulos G. Development of virus vectors for gene therapy of β chain hemoglobinopathies: flanking with a chromatin insulator reduces gamma-globin gene silencing in vivo. Blood. 2002;100:2012–2019. doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-01-0219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramezani A, Hawley TS., and , Hawley RG. Performance- and safety-enhanced lentiviral vectors containing the human interferon-β scaffold attachment region and the chicken β-globin insulator. Blood. 2003;101:4717–4724. doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-09-2991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arumugam PI, Scholes J, Perelman N, Xia P, Yee JK., and , Malik P. Improved human β-globin expression from self-inactivating lentiviral vectors carrying the chicken hypersensitive site-4 (cHS4) insulator element. Mol Ther. 2007;15:1863–1871. doi: 10.1038/sj.mt.6300259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Puthenveetil G, Scholes J, Carbonell D, Qureshi N, Xia P, Zeng L, et al. Successful correction of the human β-thalassemia major phenotype using a lentiviral vector. Blood. 2004;104:3445–3453. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-04-1427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans-Galea MV, Wielgosz MM, Hanawa H, Nienhuis AW. Suppression of clonal dominance in cultured human lymphoid cells by addition of 5′ cHS4 insulator to a lentiviral vector. Mol Ther. 2006;13:S405. doi: 10.1038/sj.mt.6300103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryu BY, Persons DA, Evans-Galea MV, Gray JT., and , Nienhuis AW. A chromatin insulator blocks interactions between globin regulatory elements and cellular promoters in erythroid cells. Blood Cells Mol Dis. 2007;39:221–228. doi: 10.1016/j.bcmd.2007.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Junker U, Böhnlein E., and , Veres G. Genetic instability of a MoMLV-based antisense double-copy retroviral vector designed for HIV-1 gene therapy. Gene Ther. 1995;2:639–646. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shin NH, Hartigan-O'Connor D, Pfeiffer JK., and , Telesnitsky A. Replication of lengthened Moloney murine leukemia virus genomes is impaired at multiple stages. J Virol. 2000;74:2694–2702. doi: 10.1128/jvi.74.6.2694-2702.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gélinas C., and , Temin HM. The v-rel oncogene encodes a cell-specific transcriptional activator of certain promoters. Oncogene. 1988;3:349–355. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coffin JM.Retroviridae and their replication Feilds Virology 1990Raven Press: New York; 1437–1500.In: Fields, BN (ed2nd edn [Google Scholar]

- Kumar M, Keller B, Makalou N., and , Sutton RE. Systematic determination of the packaging limit of lentiviral vectors. Hum Gene Ther. 2001;12:1893–1905. doi: 10.1089/104303401753153947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chung JH, Bell AC., and , Felsenfeld G. Characterization of the chicken β-globin insulator. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:575–580. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.2.575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Recillas-Targa F, Bell AC., and , Felsenfeld G. Positional enhancer-blocking activity of the chicken β-globin insulator in transiently transfected cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:14354–14359. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.25.14354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Julias JG, Ferris AL, Boyer PL., and , Hughes SH. Replication of phenotypically mixed human immunodeficiency virus type 1 virions containing catalytically active and catalytically inactive reverse transcriptase. J Virol. 2001;75:6537–6546. doi: 10.1128/JVI.75.14.6537-6546.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brulé F, Bec G, Keith G, Le Grice SF, Roques BP, Ehresmann B, et al. In vitro evidence for the interaction of tRNA(3)(Lys) with U3 during the first strand transfer of HIV-1 reverse transcription. Nucleic Acids Res. 2000;28:634–640. doi: 10.1093/nar/28.2.634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohi Y., and , Clever JL. Sequences in the 5' and 3' R elements of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 critical for efficient reverse transcription. J Virol. 2000;74:8324–8334. doi: 10.1128/jvi.74.18.8324-8334.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Topping R, Demoitie MA, Shin NH., and , Telesnitsky A. Cis-acting elements required for strong stop acceptor template selection during Moloney murine leukemia virus reverse transcription. J Mol Biol. 1998;281:1–15. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1998.1929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pathak VK., and , Temin HM. Broad spectrum of in vivo forward mutations, hypermutations, and mutational hotspots in a retroviral shuttle vector after a single replication cycle: deletions and deletions with insertions. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1990;87:6024–6028. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.16.6024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhuang J, Jetzt AE, Sun G, Yu H, Klarmann G, Ron Y, et al. Human immunodeficiency virus type 1 recombination: rate, fidelity, and putative hot spots. J Virol. 2002;76:11273–11282. doi: 10.1128/JVI.76.22.11273-11282.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herman SA., and , Coffin JM. Efficient packaging of readthrough RNA in ALV: implications for oncogene transduction. Science. 1987;236:845–848. doi: 10.1126/science.3033828. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schambach A, Galla M, Maetzig T, Loew R., and , Baum C. Improving transcriptional termination of self-inactivating gamma-retroviral and lentiviral vectors. Mol Ther. 2007;15:1167–1173. doi: 10.1038/sj.mt.6300152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Higashimoto T, Urbinati F, Perumbeti A, Jiang G, Zarzuela A, Chang LJ, et al. The woodchuck hepatitis virus post-transcriptional regulatory element reduces readthrough transcription from retroviral vectors. Gene Ther. 2007;14:1298–1304. doi: 10.1038/sj.gt.3302979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zaiss AK, Son S., and , Chang LJ. RNA 3' readthrough of oncoretrovirus and lentivirus: implications for vector safety and efficacy. J Virol. 2002;76:7209–7219. doi: 10.1128/JVI.76.14.7209-7219.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heilman-Miller SL, Wu T., and , Levin JG. Alteration of nucleic acid structure and stability modulates the efficiency of minus-strand transfer mediated by the HIV-1 nucleocapsid protein. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:44154–44165. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M401646200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berkhout B, Vastenhouw NL, Klasens BI., and , Huthoff H. Structural features in the HIV-1 repeat region facilitate strand transfer during reverse transcription. RNA. 2001;7:1097–1114. doi: 10.1017/s1355838201002035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zuker M. Mfold web server for nucleic acid folding and hybridization prediction. Nucleic Acids Res. 2003;31:3406–3415. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkg595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Butler SL, Hansen MS., and , Bushman FD. A quantitative assay for HIV DNA integration in vivo. Nat Med. 2001;7:631–634. doi: 10.1038/87979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown PO, Bowerman B, Varmus HE., and , Bishop JM. Correct integration of retroviral DNA in vitro. Cell. 1987;49:347–356. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(87)90287-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bukrinsky MI, Sharova N, Dempsey MP, Stanwick TL, Bukrinskaya AG, Haggerty S, et al. Active nuclear import of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 preintegration complexes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1992;89:6580–6584. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.14.6580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zennou V, Petit C, Guetard D, Nerhbass U, Montagnier L., and , Charneau P. HIV-1 genome nuclear import is mediated by a central DNA flap. Cell. 2000;101:173–185. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)80828-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hansen MS, Smith GJ, Kafri T, Molteni V, Siegel JS., and , Bushman FD. Integration complexes derived from HIV vectors for rapid assays in vitro. Nat Biotechnol. 1999;17:578–582. doi: 10.1038/9886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller MD, Farnet CM., and , Bushman FD. Human immunodeficiency virus type 1 preintegration complexes: studies of organization and composition. J Virol. 1997;71:5382–5390. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.7.5382-5390.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lotti F, Menguzzato E, Rossi C, Naldini L, Ailles L, Mavilio F, et al. Transcriptional targeting of lentiviral vectors by long terminal repeat enhancer replacement. J Virol. 2002;76:3996–4007. doi: 10.1128/JVI.76.8.3996-4007.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bordignon C, Notarangelo LD, Nobili N, Ferrari G, Casorati G, Panina P, et al. Gene therapy in peripheral blood lymphocytes and bone marrow for ADA-immunodeficient patients. Science. 1995;270:470–475. doi: 10.1126/science.270.5235.470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hantzopoulos PA, Sullenger BA, Ungers G., and , Gilboa E. Improved gene expression upon transfer of the adenosine deaminase minigene outside the transcriptional unit of a retroviral vector. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1989;86:3519–3523. doi: 10.1073/pnas.86.10.3519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiznerowicz M, Fong AZ, Mackiewicz A., and , Hawley RG. Double-copy bicistronic retroviral vector platform for gene therapy and tissue engineering: application to melanoma vaccine development. Gene Ther. 1997;4:1061–1068. doi: 10.1038/sj.gt.3300500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ilves H, Barske C, Junker U, Böhnlein E., and , Veres G. Retroviral vectors designed for targeted expression of RNA polymerase III-driven transcripts: a comparative study. Gene. 1996;171:203–208. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(96)00075-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moreau-Gaudry F, Xia P, Jiang G, Perelman NP, Bauer G, Ellis J, et al. High-level erythroid-specific gene expression in primary human and murine hematopoietic cells with self-inactivating lentiviral vectors. Blood. 2001;98:2664–2672. doi: 10.1182/blood.v98.9.2664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yáñez-Muñoz RJ, Balaggan KS, MacNeil A, Howe SJ, Schmidt M, Smith AJ, et al. Effective gene therapy with nonintegrating lentiviral vectors. Nat Med. 2006;12:348–353. doi: 10.1038/nm1365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Viral RNA read-through transcription was not increased with a large insert in the 3′LTR. (A) Plasmid constructs containing varying LTRs down stream of a promoter were designed with β-galactosidase gene inserted downstream of the LTR. The latter would be transcribed in case read-through transcription occurred. (B) Read-through transcription from the SIN-LTR with cHS4 insert was negligible and comparable to the wt HIV LTR and the SIN HIV LTR. β-galactosidase enzyme activity was measured by spectrophotometer, and enzyme activity was normalized for transfection efficiency. (n=3) (C) β-galactosidase staining confirmed results seen with the enzyme assay and was also performed on TE-26 cells after transfection.