Abstract

Rapid detection of brain natriuretic peptide (BNP) concentration can be used for the diagnosis of acute heart failure and for the evaluation of the effectiveness of a clinical therapy. We used the systematic evolution of ligands by exponential enrichment method to develop DNA aptamers for BNP whose sequences were determined by cloning method and consensus sequence analysis. A total of eight conserved sequences was identified. By combining the fluorescent-labeled aptamers with fast protein lab-on-chip analysis, we could achieve quantification of BNP concentrations with high speed, sensitivity, and specificity.

INTRODUCTION

Aptamers are small single-stranded (ss) nucleic acids isolated from combinatorial libraries through an iterative process of binding, partitioning, washing, elution, and amplification, which is referred to as systematic evolution of ligands by exponential enrichment (SELEX).1 The SELEX procedure is initiated with a RNA or DNA library consisting of randomized sequences that provide a vast number of sequence-specific three-dimensional structures that specifically recognize and bind to a specified target, which is then separated from the nonbinders, polymerase chain reaction (PCR) amplified, and used as refined libraries in the next round of selection.2, 3, 4, 5 This process is typically repeated 5–15 times until oligonucleotides with a reasonably high affinity and specificity for the target molecule are obtained.6 Aptamers bind to target molecules to which they have a high affinity as comparable to those of antigen antibody complexes.7 They have been developed against different classes of molecules including metal ions,8 small molecules,9, 10 and proteins.11, 12 Due to their high specificity, adaptability, and ease of modification, aptamers have been used in a wide range of applications such as drug discovery,13 high-throughput screening,14 therapeutics,15, 16 and medical and environmental diagnostics.17 Since standard DNA and RNA aptamers themselves are not inherently fluorescent, modification methods are required for rationally converting nonfluorescent aptamers into fluorescent reporters to give recordable signal generation ability.18 They can be specifically labeled with radioscopic, fluorescent, or other reporters for molecular recognition. With their advantages and unique properties, aptamers have high potential for use in medical applications.

In this study, we used the SELEX technique to construct DNA aptamers against brain natriuretic peptide (BNP). BNP is a neurohormone with a ring structure produced mainly by ventricular myocytes in response to increased end-diastolic pressure, or volume, of the ventricles.19, 20, 21 BNP causes diuresis, natriuresis, vasodilatation, and pressure regulation of the circulatory system.22, 23 The measurement of BNP concentration has been routinely used especially in the emergency department for acute dyspnea. In addition, the BNP assay is widely applied to evaluate if patients have acute heart failure (HF). The commercialized BNP assay is based on the immunoassay method and has high sensitivity.24, 25, 26 Another BNP assay method is the radioimmunoassay technique.27, 28 The method has been used to detect BNP level from blood sample of chronic HF patient which involved the use of gamma-radioactive isotopes of BNP in conjunction with anti-BNP antibody. While extremely sensitive and specific, this technique requires a sophisticated apparatus and is costly. It also requires special precautions since radioactive substances are used. We proposed to develop an assay kit for BNP. The development of highly specific and sensitive DNA aptamers instead of antibodies for the BNP assay would decrease the cost and increase the shelf life of reagents. Therefore, we analyzed the binding affinities between target and aptamers by protein lab-on-a-chip, which is usually used for the analysis of protein mixtures.29

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Conjugation of BNP antibody with ligand

Protein A-conjugated sepharose beads (GE Healthcare, Uppsala, Sweden) were used for human anti-BNP monoclonal antibody (LTK Biolab, Inc., Hsinchu, Taiwan) conjugation. The Protein A-conjugated beads were washed with 100 μl of binding buffer (10 mM N—(2–hydroxyethyl)piperazine-N′—(2–ethanesulfonic acid) (HEPES), pH 7.4, 75 mM NaCl, 5 mM MgCl2, and 1 mM CaCl2) three times. The sepharose beads were then mixed with 15 μl of BNP antibody in binding buffer for 1 h at room temperature. The conjugated BNP antibody was used as the supporting material for the SELEX experiment.

Construction of BNP-aptamers by the SELEX method

The DNA aptamer library (Mission Biotech Co., Ltd., Taipei, Taiwan) used consisted of a randomized 25 base pair (bp) DNA sequence flanked by two known 24 bp primer-binding sites, 5′-GGGAGACAAGAATAAACGCTCAAA ⟨N25⟩ TTCGACAGGAGGCTCACAACAGGC-3′, where N25 represents 25 random nucleotides with equal nucleotide composition. SELEX experiment was performed to obtain BNP-aptamer. Briefly, 1.0 mg∕ml BNP (Sigma, St. Louis, MO) and ssDNA were mixed to give a final equal molar ratio in binding buffer for 1 h at room temperature. Oligonucleotide-bound BNP were concentrated using BNP antibody conjugated with Protein A-conjugated sepharose beads. The DNA was eluted using elution buffer (0.1M glycine buffer, pH 3.0) at 80 °C for 10 min with mild shaking. DNA was recovered, washed with 75% ethanol, and then redissolved in double distilled water (ddH2O) as a template for PCR amplification with biotinylated 5′ primers (5′-biotin-GGGAGACAAGAATAAACG CTCAAA). Reagents of PCR reaction include 0.4 μM forward and reverse primers, 0.2 mM deoxyribonucleotide triphosphate (dNTP), 0.1 U∕μl Taq, 1x reaction buffer, and a template from the elution (Yeastern Biotech (Taipei, Taiwan). The PCR condition was to heat at 95 °C for 5 min, followed by denaturation at 95 °C for 3 min, annealing at 58 °C for 30 s, extension at 72 °C for 30 s for 20 cycles, and finally incubation at 72 °C for 10 min. The 73 bp double-stranded DNA (dsNNA) PCR products were examined on 3% agarose gels and further separated by streptavidin (SAV) beads to obtain ssDNA for the next round of the SELEX process. The SELEX process was repeated eight times in order to achieve enough selectivity.

Cloning and sequencing

The BNP-aptamer pools from eight cycles of the SELEX process were chosen for sequencing analysis in order to analyze the sequence of the aptamers. Aptamer pools were cloned by the pGEM®-T easy vector system from Promega (Wisconsin) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The plasmid DNA was purified using Qiaex II gel extraction kit (Qiagen, ON, Canada). Some aptamers showed molecular weight larger than 73 bp with tandem repeats of the design primer. An example of this is a sequence pattern such as F-S-R-R (F=forward primer, S=random sequence of the aptamer, and R=reverse primer). This might be due to errors in the annealing of primers to the random sequence of the designed DNA aptamer library produced during the first SELEX procedure. Only aptamers that had the same length as the original design (73 bp) were collected for analysis. A 73 bp insert of BNP-aptamers was examined by digestion with 1 U of EcoR1 at 37 °C for 30 min, followed by 3% agarose gel electrophoresis. The plasmid DNA representing the 73 bp PCR products was selected for nucleotide sequencing. PCR was carried out with a Px2 Thermal Cycler Thermo Fisher Scientific (Massachusetts).

Aptamer similarity analysis

The similarity of aptamer sequences was analyzed using the ALIGNX program in VECTOR NTI ADVANCE™ software (V9.1) from Invitrogen (Montreal, Canada) according to the neighbor-joining method30 with default parameters (gap opening penalty: 15; gap extension penalty: 6.66; gap separation penalty range: 8; and score matrix: swgapdnamt). The method is proposed for reconstructing phylogenetic trees from evolutionary distance data. It is usually used for trees based on DNA or protein sequence information. This algorithm makes the cluster of the sequences in minimization of the total branch length at each stage of clustering of operational taxonomic unit (OTU) starting with a starlike tree. Shortest pairs are chosen as neighbors and then joined as one OTU. Therefore, these distances are related to the degree of divergence between the sequences. It produces a unique final tree under the principle of minimum evolution and quite efficient in obtaining the correct tree topology by using computer simulations. The method does not assume that all lineages evolve at the same rate and produces an unrooted tree.

ELISA assay

For examining the binding affinity between aptamers and BNP, the enzyme-linked-immunosorbent assay (ELISA) assay was performed. The ELISA plate (MaxiSorp™, NUNC, Massachusetts) was coated with different concentrations of BNP. Following three washes with phosphate buffered saline with Tween 20 (PBST), the wells were blocked in 5% nonfat milk. The wells were incubated with 4 ng∕μl biotin-labeled aptamer at room temperature for 3 h. After washing with PBST, the BNP-binding aptamers were detected by SAV-horseradish peroxidase (HRP) and 3,3′,5,5′-tetramethybenzidine (TMB∕E) solution. The reaction was stopped by 0.3 mol∕l H2SO4 and the absorbance at 450 nm was recorded.

Fluorescent dye aptamer labeling

Fluorescent compound labeled to aptamer via amino group. The amino-linked BNP-aptamers were synthesized by reaction BNP-aptamers with 5′-amino-C12 modified by Mission Biotech (Nankang, Taipei, Taiwan). The amino-linked BNP-aptamers were labeled with Alexa Flour® 647 reactive dye (Invitrogen, Montreal, Canada), according to the manufacturer’s instruction with some modification. 5 μg of amide-modified BNP-aptamers dissolved in 5 μl nuclease-free water was added with 30 μl labeling buffer (1M sodium bicarbonate) and 1 μl Alexa Flour 647 reactive dye was added. The mixture was mixed and incubated at room temperature in the dark for 1 h. The fluorescent-labeled DNA was subjected to clean-up by ethanol precipitation. The aptamer pellet was resuspended in 50 μl phosphate buffer and stored at −80 °C until use.

Protein lab-on-a-chip analysis

5 μl of fluorescent-labeled BNP-aptamers (3 μg∕ml in 10 mM phosphate buffer, pH 7.4) were reacted with 15 μl BNP (0.5 mg∕ml in the same buffer) and 5 μl of the fluorescent-labeled aptamers added with 15 μl in 10 mM phosphate buffer, pH 7.4, were incubated without BNP (as control) at 37 °C for 30 min. All samples were then reconstituted with 50 μl ddH2O. The sample analysis was performed on an Agilent 2100 Bioanalyzer using the PROTEIN 50 PLUS LabChip kit (Agilent Technologies, Waldbronn, Germany). The samples were applied onto the protein chip and data analysis was performed using a PROTEIN 2100 PLUS assay software (version B.02.05.SI.360).

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

SELEX of BNP-aptamers

Aptamer technology has raised a lot of interest for many applications because of its ability to recognize various kinds of biological molecules.31 Although the radioimmunoassay method is high sensitive and specific, it requires a sophisticated apparatus, is costly, and requires special precautions due to the use of radioactive substances. The potential of applying aptamers for the detection of BNP in biological samples prompted us to develop aptamers against the peptide hormone. It is our hope that the aptamers can be used clinically.

An initial population of 1025 random-sequence DNA oligonucleotides was subjected to eight rounds of in vitro selection to favor molecules that bind BNP. Progression of the SELEX process was monitored by using nondenaturing 3% agarose gel electrophoresis and ethidium bromide staining to detect the PCR products. The BNP-aptamers were successfully amplified from the ssDNA library in eight rounds of SELEX process. Only clones with correct base pairing were selected for sequencing.

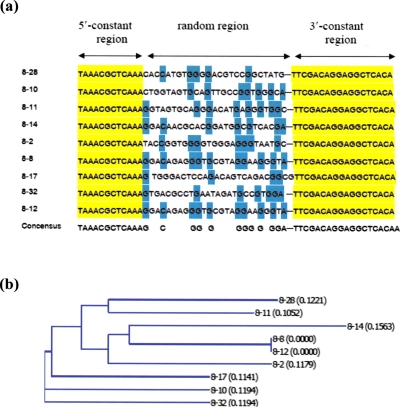

In this study, SELEX technology was used to construct DNA aptamers against BNP, a peptide hormone with a ring structure (Fig. 1). From the results of oligonucleotide sequencing, nine BNP-aptamers with eight different sequences were identified [Fig. 2a]. The alignment of all sequences showed that the aptamer consensus sequence was G--C----GG-G----GGG-G-GGA. Base composition analysis revealed a high and differing content of GC bases in the oligonucleotides. It is well known that the best outcomes from SELEX experiments are generally obtained when the target protein has a stable conformation, which allows for consistent presentation of structural epitopes from one round of selection to the next.32 According to its structure, BNP is a simple and stable cyclic peptide. Its structure may allow oligonucleotides containing some differences in GC base content to bind the peptide. It is possible that the GC-rich proportion is important for the binding of aptamers to BNP.33, 34

Figure 1.

Primary amino acid sequences of the BNP peptide hormone. Amino acids in gray circles indicate identical sequences to the ANP and CNP peptide hormones at the same positions.

Figure 2.

(a) SELEX consensus sequences of BNP-aptamer analysis using VECTOR NTI ADVANCE™ software. (b) The phylogenetic guide tree built from the software. The labels on the tree indicated number of aptamers and letters in parentheses indicated distance of similarity (degree of divergence) between the aptamers.

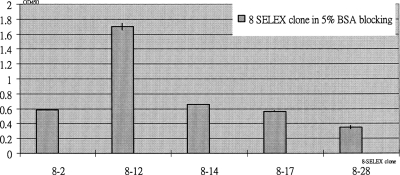

The phylogenetic guide tree was built from the VECTOR NTI ADVANCE™ Software [Fig. 2b]. It indicated that diverse DNA structures can bind to BNP under the selected condition used. In addition, the phylogenetic guide tree of BNP-aptamer sequences showed a relative similarity among the sequences. BNP-aptamer sequence 8-12, in particular, had a highly similar sequence for conserved nucleotides and may therefore have a higher possibility for BNP specificity than other sequences. We selected sequences 8-2, 8-12, 8-14, 8-17, and 8-28 for the determination of their affinity to BNP by the ELISA assay (Fig. 3). The results show that sequence 8-12 has the highest affinity for BNP. In addition, the R2 value of linear regression analysis is equal to 0.97, indicating a good fit between BNP concentration and 8-12 sequence binding.

Figure 3.

ELISA assay results of eight SELEX aptamers to BNP.

Moreover, all of the BNP-aptamers have full sequences (25-mer at variable region) and none of them were truncated. This indicated that the randomized regions of the aptamers are stable in the presence of the polymerase enzyme with endonuclease activities that are used in the experiment.35

Protein analysis based on lab-on-a-chip

Agilent lab-on-a-chip is a technology with high sensitivity for protein analysis. Its main principles and formats with miniaturized typical electrokinetic manipulations, separations, and detection methods have been described.36, 37 This technology is normally used for the analysis of protein samples, similar to sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) electrophoresis and ten samples can be analyzed in one chip.38 Herein, we took advantage of this system coupled with DNA-aptamer technology to improve performance, speed, and throughput and to reduce cost and reagent consumption in the detection of BNP. The use of the fluorescent-labeled aptamer improved the sensitivity of BNP detection and enabled detection of the aptamer-BNP complex at different retention times.

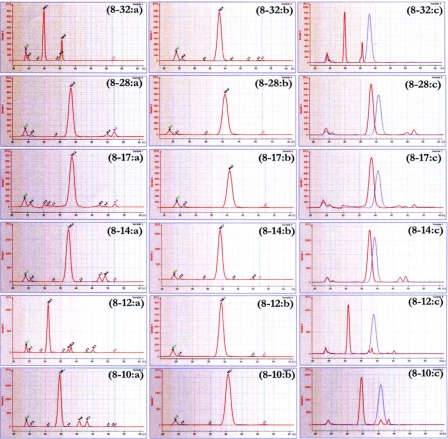

Normally, proteins or nucleic acids have different retention times on electrophoresis analysis, depending on negative charges. When a protein is bound to other proteins or nucleic acids and forms a complex, the retention time will be longer due to its higher molecular weight. BNP bound with high ratio amounts of aptamers should have a longer retention time than BNP bound with fewer molecules of aptamers. Likewise, in this study, the result showed that the aptamers themselves gave different retention times in the analysis. Since some of the aptamers formed dimers and appeared at a higher retention time in addition to the major peak, only six of the aptamers were selected for a comparison of the affinity binding with BNP (Table 1). Aptamers 8-2 and 8-11 showed a large contamination peak, which was a nucleotide dimer peak (results not shown). The BNP-aptamers 8-10, 8-12, 8-14, 8-17, 8-28, and 8-32 showed different retention times from the unbound aptamer, with a binding order of 8–12>8–32>8–10>8–28>8–17>8–14, respectively. The two aptamers, 8-12 and 8-32, gave the best different retention times from the others (Fig. 4, Table 1). The BNP-aptamer 8-12 also had higher frequency and the highest binding affinity in the SELEX experiment. This suggests that the 8-12 aptamer bound BNP with better affinity than the other aptamers. The amount of BNP that bound the aptamer was higher and raised the molecular weight of the complex. The binding between the aptamer and the BNP thus resulted in changes in the retention time when compared to other sequences. The fluorescent-labeled aptamer enabled us to detect the concentration of BNP with high sensitivity and speed. This new method is useful for screening the binding property between an aptamer and a protein target.

Table 1.

Retention time analysis of aptamer and BNP-aptamers on protein lab-on-a-chip.

| Aptamer No. | Retention time (s) | |

|---|---|---|

| Aptamer | BNP-aptamer | |

| 8–10 | 34.48 | 40.75 |

| 8–12 | 30.99 | 38.98 |

| 8–14 | 37.49 | 39.15 |

| 8–17 | 39.15 | 40.83 |

| 8–28 | 38.32 | 40.81 |

| 8–32 | 30.20 | 37.90 |

Figure 4.

Electropherograms of BNP-binding aptamers by Bioanalyzer lab-on-a-chip. Labels: (a) aptamer chromatograms; (b) aptamer-BNP chromatograms; and (c) overlay chromatograms of (a) and (b).

In this study, we applied SELEX technology to develop DNA aptamers against BNP. The development of aptamers for the BNP assay is an alternative way to decrease cost and increase throughput analysis with similar specificity and sensitivity to the immunoassay method. Combining the advantages of aptamer and the microfluidic lab-on-a-chip method, we are able to use a small amount of sample to rapidly determine the BNP concentration.

References

- Tuerk C. and Gold L., Science 249, 505 (1990). 10.1126/science.2200121 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stavis S. M., Corgié S. C., Cipriany B. R., Craighead H. G., and Walker L. P., Biomicrofluidics 1, 034105 (2007). 10.1063/1.2789565 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Esfandyarpour H., Zheng B., Pease R. F. W., and Davis R. W., Biomicrofluidics 2, 024102 (2008). 10.1063/1.2901138 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Senapati S., Mahon A. R., Gordon J., Nowak C., Sengupta S., Powell T. H. Q., Feder J., Lodge D. M., and Chang H. C., Biomicrofluidics 3, 022407 (2009). 10.1063/1.3127142 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osborne S. E. and Ellington A. D., Chem. Rev. (Washington, D.C.) 97, 349 (1997). 10.1021/cr960009c [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rimmele M., ChemBioChem 4, 963 (2003). 10.1002/cbic.200300648 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brody E. N., Willis M. C., Smith J. D., Jayasena S., Zichi D., and Gold L., Mol. Diagn. 4, 381 (1999). 10.1016/S1084-8592(99)80014-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ciesiolka J., Gorski J., and Yarus M., RNA 1, 538 (1995). [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lorsch J. R. and Szostak J. W., Biochemistry 33, 973 (1994). 10.1021/bi00170a016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson D. S. and Szostak J. W., Annu. Rev. Biochem. 68, 611 (1999). 10.1146/annurev.biochem.68.1.611 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bock L. C., Griffin L. C., Latham J. A., Vermaas E. H., and Toole J. J., Nature (London) 355, 564 (1992). 10.1038/355564a0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weiss S., Proske D., Neumann M., Groschup M. H., Kretzschmar H. A., Famulok M., and Winnacker E. L., J. Virol. 71, 7890 (1997). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bacher J. M. and Ellington A. D., Drug Discovery Today 3, 265 (1998). 10.1016/S1359-6446(97)01166-5 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Famulok M., Curr. Opin. Mol. Ther. 7, 137 (2005). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E. T.Cunningham, Jr., Adamis A. P., Altaweel M., Aiello L. P., Bressler N. M., D’Amico D. J., Goldbaum M., Guyer D. R., Katz B., Patel M., and Schwartz S. D., Ophthalmology 112, 1747 (2005). 10.1016/j.ophtha.2005.06.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siddiqui M. A. and Keating G. M., Drugs 65, 1571 (2005). 10.2165/00003495-200565110-00010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Menger M., Glokler J., and Rimmele M., in RNA Towards Medicine, edited by Erdmann V. A., Brosius J., and Barciszewski J. (Springer, Berlin, 2006), p. 359. [Google Scholar]

- Nutiu R. and Li Y., Methods 37, 16 (2005). 10.1016/j.ymeth.2005.07.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maeda K., Tsutamota T., Wada A., Hisanaga T., and Kinoshita M., Am. Heart J. 135, 825 (1998). 10.1016/S0002-8703(98)70041-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakamura S., Naruse M., Naruse K., Kawana M., Nishikawa T., and Hosoda S., Am. J. Hypertens. 4, 909 (1991). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tonolo G., Richards A. M., Manunta P., Troffa C., Pazzola A., and Madeddu P., Circulation 80, 893 (1989). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patel J. B., Valencik M. L., Pritchett A. M., Jr Burnett J. C., McDonald J. A., and Redfield M. M., Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 289, H777 (2005). 10.1152/ajpheart.00117.2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tamura N., Ogawa Y., Yasoda A., Itoh H., Saito Y., and Nakao K., J. Mol. Cell. Cardiol. 28, 1811 (1996). 10.1006/jmcc.1996.0170 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koch A. M. E., Zink S., Singer H., and Dittrich S., Eur. J. Heart Fail. 10, 60 (2008). 10.1016/j.ejheart.2007.11.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vogelsang T. W., Jensen R. J., Monrad A. L., Russ K., Olesen U. H., Hesse B., and Kjær A., Eur. J. Heart Fail. 9, 892 (2007). 10.1016/j.ejheart.2007.05.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crilley J. G. and Farrer M., Heart 86, 638 (2001). 10.1136/heart.86.6.638 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferreira A. L., Reis Z. S., Braga J., Leite H. V., and Cabral A. C., Arch. Gynecol. Obstet. 279, 335 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hogenhuis J., Voors A. A., Jaarsma T., Hillege H. L., Boomsma F., and van Veldhuisen D. J., Eur. J. Heart Fail. 7, 81 (2005). 10.1016/j.ejheart.2004.03.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsieh J. F. and Chen S. T., Biomicrofluidics 1, 014102 (2007). 10.1063/1.2399892 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Saitoi N. and Nei M., Mol. Biol. Evol. 4, 406 (1987). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellington A. D. and Szostak J. W., Nature (London) 346, 818 (1990). 10.1038/346818a0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shamah S. M., Healy J. M., and Cload S. T., Acc. Chem. Res. 41, 130 (2008). 10.1021/ar700142z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noll B. O., Debelak H., and Uhlmann E., J. Chromatogr., B: Analyt. Technol. Biomed. Life Sci. Appl. 847, 153 (2007). 10.1016/j.jchromb.2006.09.046 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cui T. and Leng F., Biochemistry 46, 13059 (2007). 10.1021/bi701269s [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lyamichev V., Brow M. A., and Dahlberg J. E., Science 260, 778 (1993). 10.1126/science.7683443 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dolnik V., Liu S., and Jovanovich S., Electrophoresis 21, 41 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Effenhauser C. S., Bruin G. J. M., and Paulus A., Electrophoresis 18, 2203 (1997). 10.1002/elps.1150181211 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nawarak J., Sinchaikul S., Wu C. Y., Liau M. Y., Phutrakul S., and Chen S. T., Electrophoresis 24, 2838 (2003). 10.1002/elps.200305552 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]