Abstract

Focusing cells into a single stream is usually a necessary step prior to counting and separating them in microfluidic devices such as flow cytometers and cell sorters. This work presents a sheathless electrokinetic focusing of yeast cells in a planar serpentine microchannel using dc-biased ac electric fields. The concurrent pumping and focusing of yeast cells arise from the dc electrokinetic transport and the turn-induced ac∕dc dielectrophoretic motion, respectively. The effects of electric field (including ac to dc field ratio and ac field frequency) and concentration (including buffer concentration and cell concentration) on the cell focusing performance were studied experimentally and numerically. A continuous electrokinetic filtration of E. coli cells from yeast cells was also demonstrated via their differential electrokinetic focusing in a serpentine microchannel.

INTRODUCTION

Focusing particles or cells into a single stream is usually a necessary step prior to counting and separating them in microfluidic devices such as flow cytometers and cell sorters.1, 2, 3, 4 Previously, particle focusing in microchannels has been achieved by pinching the suspending medium with hydrodynamic5, 6, 7, 8, 9 or electrokinetic10, 11, 12, 13, 14 sheath flows. This sheath flow focusing method requires precise control of the flow rate of both the sheath flows and the particulate stream. Particle focusing has also been achieved through the use of external force fields such as acoustic,15 optical,16 magnetic,17 electrophoretic,18 and ac dielectrophoretic forces.19, 20, 21, 22 Although these approaches directly manipulate particles to the desired positions, both external pressure pumping of the particle stream and extra setups for generating the external forces are typically required. Recently, hydrophoresis has been used to focus particles in a microchannel using obstacles on the top and bottom channel walls.23, 24 This approach is dependent on fabrication as the focusing effectiveness is sensitive to the structure of the obstacles. Particle focusing has also been obtained using inertia in curved microchannels,25, 26, 27 where the equilibrium position of the focused particle stream is sensitive to the Reynolds number.28

In addition, the concurrent pumping and focusing of particles have been demonstrated using dielectrophoresis induced in dc electrokinetic flow. However, in creating the nonuniform electric field for this focusing technique, an array or pairs of microstructures such as insulating posts and oil menisci are required.29, 30, 31 Furthermore, high electric fields in the constriction areas formed by the microstructures can cause significant Joule heating and shear stress, both of which may have strong adverse effects on cell viability, especially when dealing with mammalian cells.32 In order to overcome these issues, a sheathless dc electrokinetic focusing of particles in a planar serpentine microchannel was recently introduced by Xuan’s group.33 Due to the turn-induced negative dielectrophoretic motion, particles migrate across streamlines and flow in a focused stream along the channel centerline. While this method eliminates the in-channel microelectrodes and microinsulators and hence the accompanying adverse effects, relatively large electric fields or long channels are still required in order to focus small particles. This issue can be addressed using dc-biased ac electric fields.34, 35 As both dc and ac fields contribute to dielectrophoresis while only the former generates the net particle motion, focusing can be implemented at lower field magnitudes.

This paper presents a systematic study of electrokinetic focusing of yeast cells in a serpentine microchannel under dc-biased ac electric fields. The effects of electric field (including magnitude, ac to dc field ratio, and ac field frequency) and concentration (including cell and buffer concentrations) on the cell focusing performance are examined. Further, this focusing technique is used to demonstrate a continuous filtration of Escherichia coli (E. coli) cells from yeast cells. In addition, numerical simulation is performed to predict and verify the effectiveness of the electrokinetic focusing and filtration of cells in a serpentine microchannel.

EXPERIMENT

Microchannel fabrication

The serpentine microchannel was fabricated with polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS) using the standard soft lithography method.36 In order to make the photomask, the channel geometry was drawn in AUTOCAD® and printed onto a transparent thin film at a resolution of 10 000 dpi (CAD∕Art Services, Bandon, OR). Photoresist (SU-8 25, MicroChem Corp, Newton, MA) was applied to a clean glass slide by spin coating (WS-400E-NPP-Lite, Laurell Technologies, North Wales, PA) at a terminal speed of 2000 rpm, which yielded a nominal thickness of 25 μm. After spin coating, the slide was baked on hotplates (HP30A, Torrey Pines Scientific, San Marcos, CA) using a two-step soft bake (65 °C for 3 min and 95 °C for 7 min). The photoresist film was then exposed to near UV light (ABM Inc., San Jose, CA) through the negative photomask before being subjected to another two-step hard bake (65 °C for 1 min and 95 °C for 3 min). Following the hard bake, the photoresist was developed in SU-8 developer solution for 4 min, which left a positive replica of the microchannel on the glass slide. After briefly rinsing the slides with isopropyl alcohol, the slides were subjected to one final hard bake at 150 °C for 5 min. The cured photoresist was then ready for use as the mold of the microchannel.

The channel mold was placed into a Petri dish and covered with liquid PDMS before being degassed for 30 min in an isotemp vacuum oven (13-262-280A, Fisher Scientific, Fair Lawn, NJ). Following the degassing, the liquid PDMS was cured in a gravity convection oven (13-246-506GA, Fisher Scientific, Fair Lawn, NJ) for 2 h at 70 °C. Once cured, the PDMS covering the microchannel was cut with a scalpel and peeled off of the mold. Next, two holes were punched into the PDMS cast to serve as reservoirs. The channel side of the PDMS and a clean glass slide were then plasma treated (PDC-32G, Harrick Scientific, Ossining, NY) for 1 min. Immediately after the plasma treating, the two treated surfaces were bonded irreversibly to make the microchannel. Once sealed, the working buffer was dispensed into the channel by capillary action to prime the channel and maintain the wall surface properties.

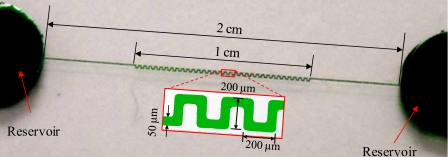

The microchannel for the experiments is a straight channel connecting two wells (serving as reservoirs) with a serpentine section in the center. Figure 1 shows a picture of the fabricated channel whose dimensions are as indicated. The serpentine section of the channel is comprised of 33 periods and used to produce the dielectrophoretic focusing of cells along the channel centerline, as explained in Sec. 3. The total length of the microchannel is 30 mm, and the width and depth are 50 and 25 μm, respectively, throughout the length of the channel.

Figure 1.

Picture and dimensions of the serpentine microchannel used in the experiments.

Cell culture

ATCC4098 yeast cells (Saccharomyces cerevisiae) were cultured at 37 °C in the sabouraud dextrose broth (Becton and Dickinson Co., USA) medium. After about 24 h, the cells were harvested and washed three times with phosphate buffered saline (PBS). The cells were then collected at an approximate concentration of 9×108 cells∕ml in 1×PBS. Prior to use, the cell concentration was diluted down to about 4.5×107 cells∕ml. The average diameter of the yeast cells was measured at about 5 μm. In preparing E. coli cells, a single colony of E. coli ORN208 was inoculated into a tryptic soy broth and incubated at 37 °C overnight. Afterward, the E. coli was centrifuged at 3000g for 3 min before being resuspended in 1×PBS. After repeating this process three times, the cells were collected at an approximate concentration of 8.9×109 cells∕ml in 1×PBS. As their diameter (about 1 μm) is much smaller than that of the yeast cells, E. coli cells were not diluted significantly prior to the experiments for visibility purposes in the recorded images. Tween 20 (Fisher Scientific) was added to the cell suspensions at 0.5% (v∕v) in order to suppress the cell adhesions to channel walls as well as the cell aggregations.

Experimental technique

The electrokinetic focusing and filtration of cells in the serpentine microchannel was achieved through negative dielectrophoresis induced by application of an electric field. A function generator (33220A, Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA) combined with a high-voltage amplifier (609E-6, Trek, Medina, NY) was used to supply both the dc and dc-biased-ac fields required in the experiments. The ac fields had a sine waveform. The behavior of cells in the microchannel was visualized using an inverted microscope (Nikon Eclipse TE2000U, Nikon Instruments, Lewisville, TX), and videos were recorded using a charge coupled device camera (Nikon DS-Qi1Mc) at a rate of 19 frames∕s. The captured videos and images were then processed using the Nikon imaging software (NIS-ELEMENTS AR 2.30). Pressure-driven cell motions were eliminated by carefully balancing the liquid heights in the two reservoirs prior to each measurement.

THEORY

Operating mechanism

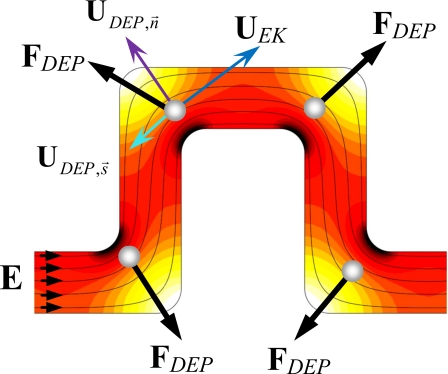

Figure 2 shows the distribution of electric field intensity (the darker the higher) and the electric field lines (with arrows showing the direction) in one period of the serpentine microchannel. Due to the variation in path length for electric current, the electric field at each of the four 90° turns becomes nonuniform and attains the local maximum and minimum values at the inner and outer corners, respectively. As a result of the electric field gradients at these corners, cells experience a dielectrophoretic force FDEP (a bold symbol denotes a vector henceforth) as they move electrokinetically through the channel turns. The time average of FDEP on an isolated spherical particle is modeled by37

| (1) |

| (2) |

where εm is the permittivity of the suspending medium, d the cell diameter, fCM the so-called Clausius–Mossotti (CM) factor that has been assumed approximately the same for dc and low frequency (<100 kHz) ac electric fields,29, 32E the root-mean-square (rms) value of the applied electric field, σc the electric conductivity of cells, and σm is the electric conductivity of the medium.

Figure 2.

Mechanism for electrokinetic cell focusing in a serpentine microchannel. The diagram shows the dielectrophoretic force experienced by the cell at each turn in one serpentine period as well as the velocity components in streamline (similar to the electric field lines as demonstrated) coordinates. The background shows the electric field contour (the darker the higher).

Since biological cells appear to be poorly conducting in dc and low-frequency ac electric fields,38 their conductivity is generally smaller than the medium conductivity, leading to fCM<0 and hence negative dielectrophoresis. Therefore, FDEP is directed toward the lower electric field region at the outer corner of each turn, as indicated in Fig. 2. Since the turns in the serpentine channel alternate direction, cells are gradually deflected toward the center region of the channel during each period as they move electrokinetically through the channel. The compounding effect results in a focused stream of cells along the channel centerline as the cells exit the serpentine section of the microchannel.

The cell velocity Uc is a combination of electrokinetic motion caused by the dc field and dielectrophoretic motion caused by both the ac and dc fields, as shown in Eq. 3,

| (3) |

| (4) |

where μEK denotes the electrokinetic mobility which is a combination of fluid electro-osmotic mobility and cell electrophoretic mobility, μDEP the dielectrophoretic mobility, Edc the dc component of the applied electric field, E=Edc+Eac with Eac being the rms value of the ac field, and μm is the dynamic viscosity of the suspending medium. As the mechanism for cell focusing in the serpentine microchannel is the cross streamline migration of cells due to dielectrophoresis, the cell velocity can be conveniently expressed in streamline coordinates, as illustrated in Fig. 2,

| (5) |

where UEK is the streamwise electrokinetic velocity, the dielectrophoretic particle velocity in the streamline direction with the unit vector , the dielectrophoretic particle velocity normal to the streamline direction with the unit vector , E the electric field intensity (i.e., E=∣E∣), and R is the radius of curvature of the streamline. It is important to note that the electric field lines shown in Fig. 2 resemble the streamlines in the serpentine channel due to the similarity between flow and electric fields in pure electrokinetic flows.39, 40

The effectiveness of cell focusing in a serpentine microchannel is determined by the ratio of the distance a cell moves perpendicular to the streamline to the distance the cell moves along the streamline. This ratio can be expressed as the ratio of the cell velocity components perpendicular and parallel to the streamline, which, as referred to Eq. 5, is given by

| (6) |

| (7) |

where has been assumed to have a much smaller magnitude than UEK in the current channel geometry, and α is the ratio of rms ac field to dc field, i.e., E=Edc+Eac=Edc (1+α). Equation 6 indicates that a larger E or α and a smaller R should provide a better focusing. The focusing performance is also dependent on the channel dimensions. Apparently cells can be more easily focused to the center of a channel with a smaller width w. Moreover, the longer the channel, or more exactly, the more serpentine periods, the better focusing will be obtained. A rough estimation of the necessary number of serpentine periods n may be written as

| (8) |

In addition, as μDEP is proportional to the square of the cell diameter [see Eq. 2], whereas μEK is only a weak function of cell size,41 bigger cells should be focused more effectively than smaller ones. This differential focusing enables the electrokinetic filtration of cells by size in a serpentine microchannel.

Numerical modeling

In order to predict and understand the effects of the working parameters on cell focusing, a numerical model was developed in order to simulate the electrokinetic transport of cells through the serpentine microchannel. This model is based on the one developed by Kang et al.,42, 43 and has recently been used by the authors to simulate the particle focusing in various structured microchannels.33, 35, 44 In this model a correction factor λ was introduced to account for the perturbation of cell size, cell-cell interactions, etc. on the dielectrophoretic velocity. Thus, Eq. 3 can be revised to show the simulated cell velocity as

| (9) |

This velocity was used as an input to the particle tracing function in COMSOL (Burlington, MA) for computing the cell trajectory. Note that the correction factor λ decreases with the increase in cell size,33, 35, 42, 43, 44 which indicates a smaller difference in the real dielectrophoretic response of cells with different sizes than that predicted by Eq. 1.

In order to determine the cell velocity in Eq. 9, the electric field distribution Edc was solved from the Laplace equation in COMSOL with a full-scale model. The electrokinetic mobility μEK was obtained by measuring the average cell velocity in the straight section of the serpentine microchannel. The dielectrophoretic mobility μDEP was determined from Eq. 4 where the dynamic viscosity μm=0.9×10−3 kg∕(m s) and permittivity εm=6.9×10−10 C∕(V m) of pure water at 25 °C were used as they closely approximate the respective properties of the PBS solution. As the electric conductivity of live cells at dc and low frequency ac electric fields is far smaller than that of the PBS buffer, the CM factor fCM in Eq. 2 was found to be approximately −1∕2. The correction factor λ was determined by matching the predicted cell trajectory to the visible thickness of the cell stream at the exit of the serpentine channel under a 50 V∕cm dc field. This obtained value was then used for all other fields and buffer concentrations. Note that the electric field magnitudes stated in this article were all obtained from a full-scale numerical modeling with the experimentally applied voltages.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSIONS

This section presents the parametric study of the effects of electric field and concentration on the electrokinetic focusing of yeast cells in the serpentine microchannel. The electric field effects examined include electric field magnitude, ac to dc field ratio, and ac field frequency, and the concentration effects examined include buffer concentration and cell concentration. In each experiment, all parameters were fixed except for the parameter being tested to ensure only the tested parameter was affecting the cell focusing. The standard parameters used in the experiments include the electric field magnitude E=100 V∕cm, the ac to dc field ratio α=2, the ac field frequency of 1 kHz, the buffer solution of 1×PBS, and the standard cell concentration as prepared in Sec. 2. The electrokinetic mobility of yeast cells in 1×PBS was measured to be μEK=3(±0.6) (μm∕s)∕(V∕cm) where the 20% variation is due to the variance in cells and the experimental error. The electrokinetic focusing technique as demonstrated here was also used to demonstrate a continuous filtration of E. coli cells from yeast cells. The results from these experiments were all compared with the simulated results from numerical modeling.

Electric field effects on yeast cell focusing

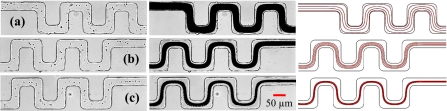

With all other parameters as given above being fixed, the electric field magnitude was varied from 50 to 100 V∕cm in order to study its effect on cell focusing. The snapshot (left column) and superimposed (middle column, a superposition of around 500 images) images of the focused yeast cells at the exit of the serpentine section of the channel are shown in Fig. 3. The cell images at the entrance [Fig. 3a] are also included to show how focusing improves as cells progress through the serpentine section. It is apparent from comparing Fig. 3c with Fig. 3b that increasing the field magnitude improves the focusing as the width of the cell stream at 100 V∕cm is narrower than at 50 V∕cm. Moreover, the cell throughput is also enhanced at a larger field magnitude. This result is consistent with Eq. 6 and also agrees with the simulated cell trajectories, as demonstrated in Fig. 3 (right column). The correction factor was set to λ=0.18 for both field magnitudes, which is much smaller than that previously obtained for 5-μm-diam polystyrene beads (λ≈0.5).33, 34, 42, 43, 44 This may be attributed to the distinctly different internal structure of yeast cells from that of polymer beads. The intrinsic variance in cell size, shape, etc., as well as the influence of Tween 20 on cell membrane permeability, may also contribute to the difference. This issue will be addressed in the future by studying the electrokinetic motion of single cells in a microchannel turn.

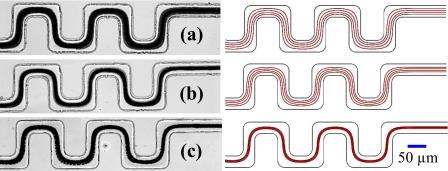

Figure 3.

Experimentally obtained images (left and middle columns) and numerically predicted trajectories (right column) of yeast cells at the (a) entrance and [(b) and (c)] exit of the serpentine section of the microchannel under the electric fields of (b) 50 and (c) 100 V∕cm. Other parameters are referred to the text.

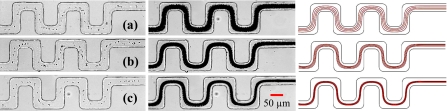

In examining the effect of the ac to dc electric ratio on cell focusing, α was varied from (a) α=0 (i.e., pure dc) to (b) α=1 (i.e., 1dc:1ac) and (c) α=2 (i.e., 1dc:2ac); see Fig. 4 for the comparison of snapshot (left column) and superimposed (middle column) images at the exit of the serpentine section. As expected from Eq. 6, cells obtain a better focusing when α is increased. It is, however, important to note that increasing α decreases the dc field component and hence reduces the cell throughput. The simulation results in Fig. 4 (right column) show the same trend as in the experimental images. The correction factor was still set to λ=0.18 as it is independent of electric field.33, 35, 42, 43, 44 In all cases, the simulated cell trajectories agree well with the experimental results, which justifies the use of the correction factor in the modeling.

Figure 4.

Experimentally obtained images (left and middle columns) and numerically predicted trajectories (right column) of yeast cells at the exit of the serpentine section of the microchannel for (a) α=0 (i.e., pure dc), (b) α=1 (i.e., 1dc:1ac), and (c) α=0 (i.e., 1dc:2ac) at a total field magnitude of 100 V∕cm.

The effect of ac field frequency on cell focusing was also examined, where three different frequencies, 100 Hz, 1 kHz, and 10 kHz, have been tested. No higher frequency was applied due to the limitation of the amplifier. At these frequencies, there was no significant change in the width of the focused cell stream at the exit of the serpentine section. This was expected because the frequency effect is represented by the CM factor in Eq. 1, which only has a substantial impact on dielectrophoresis once the frequency exceeds 100 kHz.29, 32

Concentration effects on yeast cell focusing

The effects of buffer and cell concentrations on yeast cell focusing in the serpentine microchannel were both examined. Figure 5 compares the superimposed cell images (left column) from the exit of the serpentine section at three different buffer solutions: (a) 0.01×PBS, (b) 0.1×PBS, and (c) 1×PBS. The cell concentration was maintained at the standard concentration as used in all previous tests. It was observed that increasing the buffer concentration increases the effectiveness of the cell focusing. This is because cells move slower when the buffer concentration is increased. The measured electrokinetic mobilities of yeast cells are μEK=7(±1.4) and 5(±1) (μm∕s)∕(V∕cm) in the 0.01× and 0.1×PBS, respectively, in contrast to μEK=3(±0.6) (μm∕s)∕(V∕cm) in the 1×PBS. The decrease in cell mobility with increasing buffer concentration is mainly attributed to the reduced electro-osmotic flow.45, 46 At lower velocities, there is more time for the dielectrophoretic force to affect the cells at each turn as they progress through the channel, which leads to an improved focusing in the serpentine channel. This trend can also be clearly seen in the simulation results in Fig. 5 (right column), where the measured cell electrokinetic mobilities have been used and the correction factor was still fixed at λ=0.18.

Figure 5.

Experimentally obtained images (left column) and numerically predicted trajectories (right column) of yeast cells at the exit of the serpentine section of the microchannel for buffer concentrations of (a) 0.01×PBS, (b) 0.1×PBS, and (c) 1×PBS.

In testing the effect of cell concentration on focusing, the original yeast cell sample was not diluted. The cell images thus obtained from the exit of the serpentine section [Fig. 6a] are compared with those at the standard cell concentration [Fig. 6b]. Apparently increasing the cell concentration can decrease the effectiveness of cell focusing. This is due in part to the cell-cell interactions which affect cell dielectrophoresis and the fact that there is not always room for the cells to form a thin stream at the exit regardless of the effectiveness of the focusing. The latter is clearly seen in comparing the snapshot images (left column in Fig. 6) for the two cell concentrations. The reduced yeast cell focusing at the high cell concentration appears to be well predicted by decreasing the correction factor from λ=0.18 to 0.12 in the simulation, as demonstrated in Fig. 6 (right column).

Figure 6.

Experimentally obtained images (left and middle columns) and numerically predicted trajectories (right column) of yeast cells at the exit of the serpentine section of the microchannel for (a) high cell concentration and (b) standard cell concentration.

Electrokinetic filtration of E. coli cells from yeast cells

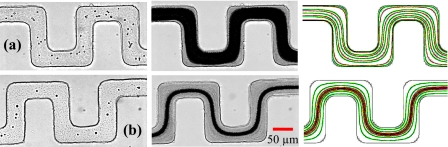

The electrokinetic cell focusing method was also used to demonstrate an electrokinetic filtration of cells by size in the serpentine microchannel. For this purpose, E. coli cells were mixed with yeast cells in 1×PBS. The standard parameters as presented earlier were employed. Figure 7 shows the snapshot and superimposed images recorded from (a) the entrance and (b) the exit of the serpentine section. Both the yeast and E. coli cells were unfocused at the entrance to the serpentine section, see Fig. 7a. This can be easily seen by observing the widths of the cell streams in the superimposed image, where yeast cells appeared dark while E. coli cells appeared gray. At the exit of the serpentine section, however, yeast cells were aligned along the channel centerline while E. coli cells still scattered, see Fig. 7b. This differential electrokinetic focusing lies in the size difference between the two types of cells. Although it is not a complete separation, the unfocused E. coli cells can be filtered from the focused yeast cells if a three-branch outlet is designed to follow the serpentine section. Notably the predicted cell trajectories closely agree with the experimental results, as shown in Fig. 7 (right column), where the green trajectories represent E. coli cells and the red trajectories represent yeast cells. The correction factor for E. coli cells was set to λ=1. The measured electrokinetic mobility of E. coli is approximately 5(μm∕s)∕(V∕cm).

Figure 7.

Experimentally obtained images (left and middle columns) and numerically predicted trajectories (right column) of yeast and E. coli cells at the (a) entrance and (b) exit of the serpentine section of the microchannel.

Joule heating and cell viability test

As 1×PBS is highly conductive and was used in the majority of the cell focusing experiments, Joule heating may have caused a temperature rise in the solution affecting cell viability.30 In order to ensure that Joule heating was not an issue in these tests, the electric current in 1×PBS was monitored when the highest electric field of 100 V∕cm was applied. The current was found to remain at 30 μA for 5 min with no noticeable increase, indicating negligible Joule heating in all the tests.47

Other adverse effects on cell viability may be caused by the electric field-induced transmembrane voltage, especially from the dc field.32 For this reason, a cell viability test was performed by staining a sample of the yeast cells from both the inlet and outlet reservoirs with methylene blue. As viable cells with an intact cellular membrane reject methylene blue and remain translucent while nonviable cells with permeable cellular membrane are stained blue, the impact of electric field exposure on cell viability can be determined by comparing the percentage of viable cells in the inlet and outlet reservoirs. It was confirmed that more than 95% of the yeast cells were still alive after being exposed to the most abrasive electric field used in the experiments, which is the 100 V∕cm dc electric field.

CONCLUSION

A sheathless cell-friendly electrokinetic focusing technique has been demonstrated in a planar serpentine microchannel using dc-biased ac electric fields. This technique uses the dc electrokinetic motion to pump the cell suspension while exploiting the induced cross-stream ac∕dc dielectrophoretic motion within the turns to focus cells along the channel centerline. The fabricated in-channel microstructures (either electrodes or obstacles) and∕or the external pressure-driven pumping that are typically required in dielectrophoresis-based particle focusing approaches are thus eliminated. This greatly simplifies the device fabrication as well as the device operation. Using a combination of experimental and numerical methods, the effects of five parameters, including electric field magnitude, ac to dc field ratio, ac field frequency, buffer concentration, and cell concentration on the focusing performance of yeast cells in a serpentine microchannel have been examined. It is found that the effectiveness of cell focusing is enhanced with increasing field magnitude, ac to dc field ratio, and buffer concentration, or by decreasing cell concentration. The electrokinetic cell focusing in serpentine microchannels has also been demonstrated to continuously filter E. coli cells from yeast cells. This serpentine cell focusing microchannel can be envisioned as a front-end device for cell detection and sorting in lab-on-a-chip devices for numerous other applications.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by NSF (Grant No. CBET-0853873) with Marc S. Ingber as the grant monitor.

References

- Huh D., Gu W., Kamotani Y., Grotgerg J. B., and Takayama S., Physiol. Meas. 26, R73 (2005). 10.1088/0967-3334/26/3/R02 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chung T. D. and Kim H. C., Electrophoresis 28, 4511 (2007). 10.1002/elps.200700620 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pamme N., Lab Chip 7, 1644 (2007). 10.1039/b712784g [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ateya D. A., Erickson J. S., P. B.Howell, Jr., Hilliard L. R., Golden J. P., and Ligler F. S., Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 391, 1485 (2008). 10.1007/s00216-007-1827-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee G. B., Chang C. C., Huang S. B., and Yang R. J., J. Micromech. Microeng. 16, 1024 (2006). 10.1088/0960-1317/16/5/020 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Simonnet C. and Groisman A., Anal. Chem. 78, 5653 (2006). 10.1021/ac060340o [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang C. C., Huang Z. Y., and Yang R. J., J. Micromech. Microeng. 17, 1479 (2007). 10.1088/0960-1317/17/8/009 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tsai C. G., Hou H. H., and Fu L. M., Microfluid. Nanofluid. 5, 827 (2008). 10.1007/s10404-008-0284-6 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lin T. A., Hosoi A. E., and Ehrlich D. J., Biomicrofluidics 3, 014101 (2009). 10.1063/1.3055278 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fu L. M., Yang R. J., and Lee G. B., Anal. Chem. 75, 1905 (2003). 10.1021/ac020741d [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang R. J., Chang C. C., Huang S. B., and Lee G. B., J. Micromech. Microeng. 15, 2141 (2005). 10.1088/0960-1317/15/11/021 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Xuan X. and Li D., Electrophoresis 26, 3552 (2005). 10.1002/elps.200500298 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chu H., Doh II, and Cho Y. H., Lab Chip 9, 686 (2009). 10.1039/b812213j [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewpiriyawong N., Yang C., and Lam Y. C., Biomicrofluidics 2, 034105 (2008). 10.1063/1.2973661 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi J., Mao X., Ahmed D., Colletti A., and Huang T. J., Lab Chip 8, 221 (2008). 10.1039/b716321e [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao Y., Fujimoto B. S., Jeffries G. D. M., Schiro P. G., and Chiu D. T., Opt. Express 15, 6167 (2007). 10.1364/OE.15.006167 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramadan Q., Samper V., Poenar D., and Yu C., Biomed. Microdevices 8, 151 (2006). 10.1007/s10544-006-7710-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takahashi T., Ogata S., Nishizawa M., and Matsue T., Electrochem. Commun. 5, 175 (2003). 10.1016/S1388-2481(03)00002-X [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lin C. H., Lee G. B., Fu L. M., and Hwey B. H., J. Microelectromech. Syst. 13, 923 (2004). 10.1109/JMEMS.2004.838352 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yu C., Vykoukal J., Vykoukal D. M., Schwartz J. A., Shi L., and Gascoyne P. R. C., J. Microelectromech. Syst. 14, 480 (2005). 10.1109/JMEMS.2005.844839 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng I. F., Chang H. C., Hou D., and Chang H. C., Biomicrofluids 1, 021503 (2007). 10.1063/1.2723669 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tornay R., Braschler T., Demierre N., Steitz B., Finka A., Hofmann H., Hubbell J. A., and Renaud P., Lab Chip 8, 267 (2008). 10.1039/b713776a [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi S., Song S., Choi C., and Park J. K., Small 4, 634 (2008). 10.1002/smll.200700308 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi C. and Park J. K., Anal. Chem. 80, 3035 (2008). 10.1021/ac8001319 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Carlo D., Irimia D., Tompkins R. G., and Toner M., Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 104, 18892 (2007). 10.1073/pnas.0704958104 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mao X. L., Waldeisen J. R., and Huang T. J., Lab Chip 7, 1260 (2007). 10.1039/b711155j [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seo J., Lean M. H., and Kole A., Appl. Phys. Lett. 91, 033901 (2007). 10.1063/1.2756272 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Di Carlo D., Edd J. F., Irimia D., Tompkins R. G., and Toner M., Anal. Chem. 80, 2204 (2008). 10.1021/ac702283m [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cummings E. B. and Singh A. K., Anal. Chem. 75, 4724 (2003). 10.1021/ac0340612 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xuan X., Raghibizadeh S., and Li D., J. Colloid Interface Sci. 296, 743 (2006). 10.1016/j.jcis.2005.09.039 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thwar P. K., Linderman J. J., and Burns M. A., Electrophoresis 28, 4572 (2007). 10.1002/elps.200700373 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Voldman J., Annu. Rev. Biomed. Eng. 8, 425 (2006). 10.1146/annurev.bioeng.8.061505.095739 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu J., Tzeng T. J., Hu G., and Xuan X., Microfluid. Nanofluid. 7, 751 (2009). 10.10907/s10404-009-0432-7 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hawkins B. G., Smith A. E., Syed Y. A., and Kirby B. J., Anal. Chem. 79, 7291 (2007). 10.1021/ac0707277 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu J. and Xuan X., Electrophoresis 30, 2668 (2009). 10.1002/elps.200900017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duffy D. C., McDonald J. C., Schueller O. J. A., and Whitesides G. M., Anal. Chem. 70, 4974 (1998). 10.1021/ac980656z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morgan H. and Green N. G., AC Electrokinetic: Colloids and Nanoparticles (Research Studies Press, Hertfordshire, England, 2003). [Google Scholar]

- Marks G. H., Huang Y., Zhou X. F., and Pethig R., Microbiology 140, 585 (1994). 10.1099/00221287-140-3-585 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cummings E. B., Griffiths S. K., Nilson R. H., and Paul P. H., Anal. Chem. 72, 2526 (2000). 10.1021/ac991165x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santiago J. G., Anal. Chem. 73, 2353 (2001). 10.1021/ac0101398 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson J. L., Annu. Rev. Fluid Mech. 21, 61 (1989). 10.1146/annurev.fl.21.010189.000425 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hyoung Kang K., Xuan X., Kang Y., and Li D., J. Appl. Phys. 99, 064702 (2006). 10.1063/1.2180430 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kang K., Kang Y., Xuan X., and Li D., Electrophoresis 27, 694 (2006). 10.1002/elps.200500558 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu J. and Xuan X., J. Colloid Interface Sci. 340, 285 (2009). 10.1016/j.jcis.2009.08.031 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hunter R. J., Zeta Potential in Colloid Science, Principles and Applications (Academic, New York, 1981). [Google Scholar]

- Tandon V. and Kirby B. J., Electrophoresis 29, 1102 (2008). 10.1002/elps.200800735 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xuan X., Electrophoresis 29, 33 (2008). 10.1002/elps.200700302 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]