Abstract

The soil dwelling nematode Caenorhabditis elegans (C. elegans) is an excellent model organism for the study of numerous disease including neurodegenerative disease. In this study, a programmable microvalve-based microfluidic array for real-time and long-term monitoring of the neurotoxin-induced responses of the individual C. elegans was developed. The device consisted of a flow layer and a control layer, which were used for worm manipulation. By activating the programmable microvalves in the control layer, mutiple worms could be individually captured and intermittently immobilized in parallel channels. Thus the mobility behavior, together with the corresponding dopaminergic neuron features of the worms in response to neurotoxin, could be investigated simultaneously. It was found that the neurotoxin MPP+ enabled to induce mobility defects and dopaminergic neurons loss in worms. The established system is easy and fast to operate, which offers not only the controllable microenvironment for analyzing the individual worms in parallel, monitoring the same worm over time, but also the capability to characterize the mobility behavior and neuron features in response to stimuli simultaneously. In addition, the device enabled to sustain the worm culture over most of their adult lifespan without any harm to worm, providing a potential platform for lifespan and aging research.

INTRODUCTION

The soil dwelling nematode Caenorhabditis elegans (C. elegans) is an excellent model organism for a variety of biological studies due to the unique characteristics of its development, genetics, and neurology. In particular, the basic composition of neurotransmitters, synaptic proteins, and ion channels are highly conserved between C. elegans and human beings, which makes it an effective tool for investigating the multicellular processes, numerous diseases (e.g., neurodegenerative disease), and drug discovery.1, 2 Because of the high mobility of the worms, effective immobilization is often required for the better observation and imaging of specific neurons during the studies of neurobiology. Traditionally, glue and anesthetics are used for immobilizing the C. elegans;3, 4, 5 however, these methods are time consuming, which often require manual operations. They also lead to potential toxicity and irreversibility, limiting the use for the real-time and long-term monitoring of the responses of worms to stimulus. Therefore, a new approach that enables to manipulate the individual worms conveniently, harmlessly, as well as reversibly is highly desirable.

Microfluidics has recently aroused increasing interests in C. elegans study attributed to its benefits including miniaturizing and integrating various operations by flexible, and especially the perfect match with the size of worms at microscale dimension. Microfluidics-based C. elegans studies have been carried out for maze exploration,6 oxygen sensation,7 phenotype and genetic screenings,8, 9 automatic cultivation,10 and individual movement assay.11 In addition, some microfluidic systems, which utilized the microfabricated tapered channels12, 13 or microvalves14, 15, 16, 17 for imaging analysis, have been reported as well. However, real-time and long-term monitoring of the individual worms in response to stimulus in terms of mobility and neuron features still imposes a challenge.

In this study, we demonstrated a programmable microvalve-based microfluidic array for real-time and long-term monitoring of the neurotoxin-induced responses of the individual C. elegans. The mobility behavior and the corresponding dopaminergic neuron features of the worms were investigated simultaneously. The programmable microvalves were incorporated to manipulate individual worms, and each microvalve could be adjusted according to the specific requirement of its closed state and speed. Multiple worms were individually captured, immobilized, and released under flexible control by using the design, which enabled to realize the real-time monitoring of the worms for a long term. The established system could immobilize and release the same worm repeatedly, facilitating the continuous monitoring and tracking the responses of worms to chemical stimulation at single-animal resolution, thus, providing a potential platform for screening of chemical compounds.

EXPERIMENTAL

Microfluidic device fabrication

The microfluidic device (shown in Fig. 1) was fabricated in polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS) (Sylgard Silicone elastomer 184, Dow Corning Corp. Midland, MI) by a rapid prototyping method18 and utilized the well-established “PDMS flow-control layer” technique.19 The flow layer master was prepared on a glass wafer by spinning SU-8 3035 negative photoresist (Microchem Corp, Newton, MA) at a thickness of 80 μm in distribution channels and 45 μm in imaging channels, respectively, and patterned by photolithography. The control layer master was patterned in a same way and the thickness was 35 μm. PDMS base and curing agent with two different mixing ratios (5:1 and 10:1 by mass) were mixed thoroughly and degassed under vacuum. The PDMS with 5:1 ratio was used to create the flow layer, and the PDMS with 20:1 ratio was to create the control layer. The flow layer was peeled off from the SU-8 master and subsequently bonded to the control layer at 80 °C for at least 2 h. Then, the two-layer PDMS replica was peeled off from the glass wafer and trimmed to size. Finally, the PDMS slab was bonded irreversibly to a glass cover slip using air plasma.

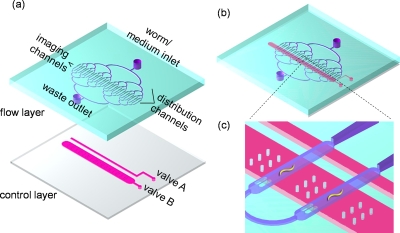

Figure 1.

Schematic of the microvalve-based microfluidic device for monitoring C. elegans. (a) Layout of the microfluidic device, which is composed of upper flow layer and lower control layer. (b) Schematic of the overall structure. (c) A magnified view of two imaging channels in the microfluidic device.

Worm culture and treatment

Wild-type N2 and transgenetic strain UA57 (genotype was baIn4) C. elegans were obtained from the Caenorhabditis Genetics Center at the University of Minnesota (St. Paul) and was cultivated as described by Brenner.20 Briefly, worms were cultivated at 20 °C on nematode growth medium (NGM) agar seeded with Escherichia coli OP50 (food). Prior to seeding, bacteria were incubated overnight at 37 °C.

For the neurotoxin-induced response assays, a suspension of L1 UA57 worms with bacteria in NGM was distributed into 96-well microtiter plates containing 1-methyl-4-phenylpyridinium (MPP+) (Sigma, St. Louis, MO) at various concentrations (0, 0.5, and 1.0 mM), the plates were incubated at 20 °C until the worms reached adulthood stage, and then analyzed.

For the postimmobilized survival test, the adult N2 worms captured in the imaging channels were flushed out and collected by applying positive pressure to the syringe connected to the outlet, the postimmobilized worms were then transferred to a fresh Petri dish, and the day of transferring was defined as 0 day. We monitored the survival of the worms for the subsequent up to 4 days. The test population consisted of 22 worms that were immobilized and released five times (the immobilizing time is about 5 min for each time), and the control population consisted of 24 worms that were not run through the device. Both populations were monitored once a day for dead animals. An animal was scored as dead if it did not respond to prodding with a platinum worm pick.

Worm loading and manipulation

Adult worms were collected and added to the inlet. By applying negative pressure to the syringe connected to the outlet, the worms were loaded into the imaging channels. The immobilizing and releasing individual worms were achieved by activating the two programmable microvalves (valves A and B in Figs. 12) in the control layer. The programmable microvalves were controlled using the stepping motor.

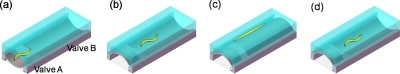

Figure 2.

The operation processes of the microvalves for immobilizing and releasing of worms on chip. (a) The worm was loaded into the imaging channels (valves A and B were switched on); (b) the worm was trapped into the imaging channel (valve A was switched off); (c) the worm was immobilized for imaging (valve B was switched off); (d) the worm was released after imaging (valve B was switched on).

Worm mobility behavior analysis

The mobility behavior of individual worms in response to the neurotoxin was recorded using an inverted fluorescent microscope (Olympus IX 71, Japan). After being captured into the imaging channels, the worms were allowed to acclimate for 30 s, and then the number of their body bends in 20 s intervals was recorded for each worm. Three independent experiments were performed at each condition.

Fluorescence imaging

The green fluorescent protein (GFP) expression in transgenetic strains UA57 in response to the neurotoxin was examined using the same inverse fluorescence microscope with excitation wavelengths at 470–495 nm and detection wavelengths at 510–550 nm. The fluorescence images were analyzed using image processing and analysis software (IMAGE-PRO, Media Cybernetics, USA).

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Microfluidic device design and operation for worm manipulation

In this work, a programmable microvalve-based microfluidic array was designed to manipulate the individual worms, and the schematic of the device was shown in Fig. 1. It consisted of a flow layer and a deformable PDMS membrane, which served as a control layer. In the flow layer, there were two functional units, including the distribution channels and the imaging channels. The worms were loaded from a tapered distributing channel (from 100 to 70 μm in width) to a wider (250 μm in width) channel for immobilizing and imaging, and a parallel channel design was implemented to benefit for the analysis of multiple worms at same time. In most cases, the tapered end of the distributing channel was sufficient to limit a single worm within one of the imaging channels. The two narrow grooves (30 μm interval distance) at the end of the imaging channel were designed to prevent the captured worm from escaping from the imaging channel. In the control layer, two programmable microvalves were activated to manipulate the worms, and valve A was designed for trapping the worms, while valve B for immobilizing the worms. The operation processes for each step were illustrated in Fig. 2. (a) Before the worms entered the imaging channel, both valves A and B were switched on in order to form the continuous worm flow. (b) Once the worms were loaded into the imaging channels, valve A was switched off immediately to prevent the worms from escaping. At that time, valve B was still open, the total height of imaging area was 80 μm (the height of control channels was involved), which was sufficient for the free movement of the worms. (c) For imaging, valve B was switched off gradually to immobilize individual worms in a linear position. (d) After imaging, valve B was switch on. By repeatedly switching valve B, the real-time imaging and the long-term monitoring of the individual worms could be obtained.

Microfluidic device performance validation

Prior to characterization of the neurotoxin-induced responses of individual worms, adult N2 worms were used to verify the performance of the proposed microfluidic device. Commonly, the captured worm retained high mobility until the pushed-up PDMS membrane restricted its movement space. By continuously pushing up the deformable PDMS membrane (switching off valve B), the worm was squeezed to the side of the imaging channel and its movement could be fully restricted. The finely immobilized worm recovered its mobile activity quickly after the PDMS membrane was pushed down (switching on valve B). A series of images for the immobilizing and releasing process were shown in Fig. 3b(i) and Fig. 3b(iii) (enhanced). By controlling the incorporated microvalves, the device was able to capture individual worms into parallel channels for immobilizing and imaging conveniently [Fig. 3c]. The processes for loading and immobilizing multiple worms were accomplished within 30 and 20 s, respectively, which were much faster than conventional methods. As the cross sections of channels were rectangular, the formed gap between PDMS membrane and channel walls made the captured worms able to get the liquid medium (nutrient and stimulus), thus, maintaining the nutrient conditions of worms during long-term monitoring. In this design, by maintaining the individual worms in separate imaging channels and supplying nutrient delivery, the device was enabled to perform long-term culture up to 7 days without harm to the worms.

Figure 3.

(a) Photograph of the microvalve-based microfluidic device used in this experiment. (b) Photographs of a single worm (i) before (enhanced), (ii) during, and (iii) after (enhanced) immobilization. (c) Photograph of the adult worms immobilized within the microchannels. The immobilized worms were marked by arrows.

To further demonstrate the feasibility of the proposed device for long-term imaging, we performed a postimmobilized survival test. Both the test and control populations were monitored for 4 days. We did not observe any morphological and movement defects or premature death in test populations (data are not shown).

Characterizing the neurotoxin-induced responses of individual worms

Based on the above work, the responses of the individual worms to neurotoxin were further characterized by using the microfluidic device. MPP+ has been reported to cause Parkinson diseaselike symptoms in vertebrates by selectively destroying dopaminergic neurons.1 In this study, a transgenic strain UA57, which expressed strong and specific green fluorescence in all eight dopaminergic neurons, was used for the following work.

Mobility defects induced by MPP+

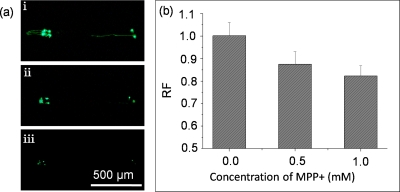

We first characterized the mobility behavior of individual worms in response to MPP+. After the worms were individually loaded into the imaging channels, we immediately switched off valve A, while maintaining valve B open, the mobility behavior of the individual worms were recorded and analyzed. Typically, the untreated worms exhibited free movements with more often sine wave-shape and C-shape movement states [Fig. 4a(i) (enhanced)] in the imaging channels, whereas the worms after MPP+ treatment were subjected to mobility defects, such as slow, titanic, and coiled movements [Fig. 4a]. The correlative analysis of the stroke frequency of individual worms associated with MPP+ concentration was shown in Fig. 4b. As shown in Fig. 4b, the stroke frequency of worms decreased with the increased concentration of MPP+. We also found that in most cases, the worms treated with 0.5 mM MPP+ only exhibited slow mobility without obvious change in their movement state (sine wave-shape and C-shape) [Fig. 4a(ii) (enhanced)]; but the situation was significantly changed in worms treated with 1.0 mM MPP+, not only the slow stroke frequency but also the coiled or titanic state [Fig. 4a(iii) (enhanced)] were observed. From the results shown in Fig. 4, we could easily concluded the MPP+ induced different mobility defects of the worms and the phenotypes could be characterized at single-animal resolution.

Figure 4.

Mobility defects induced by the MPP+. (a) Representative images of mobility shapes of the worms treated with MPP+ at different concentrations, (i) 0 mM MPP+ (enhanced), (ii) 0.5 mM MPP+ (enhanced), and (iii) 1.0 mM MPP+ (enhanced). (b) The histogram of the stroke frequency of the worms treated with MPP+ at different concentrations. Error bars represented standard deviation from three independent experiments.

Dopaminergic neurons features induced by MPP+

After the mobility behaviors were evaluated, the dopaminergic neuron features of the worms in response to MPP+ were subsequently characterized. By gradually switching off valve B, the captured worms were immobilized in a linear position for imaging, and their GFP expression in eight dopaminergic neurons were imaged and analyzed. As shown in Fig. 5a, the untreated worms expressed intact and strong GFP expression in all eight dopaminergic neurons. As a comparison, the worms treated with 0.5 mM MPP+ showed significant reduction or complete loss of GFP expression in the dendrites of dopaminergic neurons with the retention of GFP expression in cell soma, and a more significant reduction in GFP expression in the dopaminegic cell bodies was observed in the worms treated with 1.0 mM MPP+. The relative fluorescence intensity of GFP expression in the individual worms treated with MPP+ at different concentrations was shown in Fig. 5b, and the degree of GFP expression related to MPP+ was dose dependent. Coupled with the mobility analysis results, the worms with no mobility defects showed intact and strong GFP expression, and the worms with different mobility defects showed a reduction in GFP expression, suggesting that the mobility defects were closely related to a reduction in GFP expression in dopaminergic neurons.

Figure 5.

Dopaminergic neuron features induced by the MPP+. (a) Fluorescence images of the worms treated with MPP+ at different concentrations, (i) 0 mM MPP+, (ii) 0.5 mM MPP+, and (iii) 1.0 mM MPP+. (b) The histogram of the relative fluorescence intensity in dopaminergic neurons of the worms treated with MPP+ at different concentrations. Error bars represented standard deviation from three independent experiments.

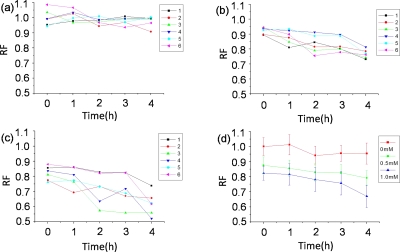

Real-time monitoring of the dopaminergic neuron features in individual worms

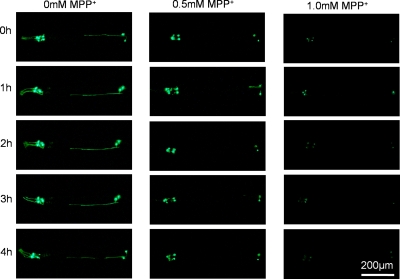

The neurotoxic effect of MPP+ on dopaminergic neurons was further characterized by monitoring the GFP expression in dopaminergic neurons in real time. Based on the preliminary work, we chose 4 h as the monitoring time duration, which was sufficient for observing the continuous attenuation of GFP expression in the MPP+ treated worms. The captured worms were intermittently immobilized for imaging by repeatedly switching valve B, and the fluorescent photographs were taken at every 1 h interval for a continuous period of 4 h. The attenuated GFP expression suggested the potential neurotoxicity of MPP+ on dopaminergic neurons (Fig. 6). Furthermore, the attenuated GFP expression, expressed by the relative fluorescence intensity, was observed in time- and dose-response manners (Fig. 7). As shown in Fig. 7d, after treated with MPP+ at different concentrations (0.5 and 1.0 mM), the relative fluorescence intensity in the worms decreased to 79.19% and 67.07%, respectively.

Figure 6.

Real-time monitoring of the dopaminergic neuron loss in the worms treated with MPP+ at different concentrations.

Figure 7.

The curves of the relative fluorescence intensity in dopaminergic neurons of individual worms and total worms. (a)–(c) represented the relative fluorescence intensity of the individual worms randomly selected from the total worms: (a) 0 mM MPP+, (b) 0.5 mM MPP+, and (c) 1.0 mM MPP+. (d) represented the average relative fluorescence intensity from the total worms. Error bars represented standard deviation from three independent experiments.

Due to the individual difference, worms of same genotype might show different responses to stimulus. During the experiment, we noticed the obvious differences among the individual worms tested [Figs. 7a, 7b, 7c], indicating the special ability of this device for tracking the responses of individual worms to stimulation over time. In such a case, the unique characteristics from the individual worms can be obtained, which is not possible by using the traditional methods.

CONCLUSIONS

We have demonstrated a new programmable microvalve-based microfluidic device for the analysis of individual C. elegans with more flexibility. The established system is simple and fast to operate, which offers not only the controllable microenvironment for analyzing the individual worms in parallel, monitoring the same worm over time, but also the capability to characterize the mobility behavior and neuron features in response to stimuli simultaneously. This device could be potentially applied for whole animal assay and screening of antineurodegenerative drugs at single-animal resolution. In addition, the capabilities of this device to maintain a long-term worm culture make it an attractive platform for lifespan and aging study.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by the National Nature Science Foundation of China (Grant Nos. 90713014 and 20635030), the Ministry of Science and Technology of China (Grant Nos. 2007CB714505 and 2007CB714507), and the Knowledge Innovation Program of the Chinese Academy of Sciences (Grant No. KJCX2-YW-H18).

References

- Braungart E., Gerlach M., Riederer P., Baumeister R., and Hoener M. C., Neurodegener. Dis. 1, 175 (2004). 10.1159/000080983 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nass R., Miller D. M., and Blakely R. D., Parkinsonism Relat. Disord. 7, 185 (2001). 10.1016/S1353-8020(00)00056-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodman M. B., Hall D. H., Avery L., and Lockery S. R., Neuron 20, 763 (1998). 10.1016/S0896-6273(00)81014-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kerr R., Lev-Ram V., Baird G., Vincent P., Tsien R. Y., and Schafer W. R., Neuron 26, 583 (2000). 10.1016/S0896-6273(00)81196-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis J. A., Wu C. H., Berg H., and Levine J. H., Genetics 95, 905 (1980). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qin J. H. and Wheeler A. R., Lab Chip 7, 186 (2007). 10.1039/b613414a [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gray J. M., Karow D. S., Lu H., Chang A. J., Chang J. S., Ellis R. E., Marletta M. A., and Bargmann C. I., Nature (London) 430, 317 (2004). 10.1038/nature02714 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chung K. H., Crane M. M., and Lu H., Nat. Methods 5, 637 (2008). 10.1038/nmeth.1227 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crane M. M., Chung K., and Lu H., Lab Chip 9, 38 (2009). 10.1039/b813730g [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim N., Dempsey C. M., Zoval J. V., Sze J. Y., and Madou M. J., Sens. Actuators B 122, 511 (2007). 10.1016/j.snb.2006.06.026 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Shi W. W., Qin J. H., Ye N. N., and Lin B. C., Lab Chip 8, 1432 (2008). 10.1039/b808753a [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hulme S. E., Shevkoplyas S. S., Apfeld J., Fontana W., and Whitesides G. M., Lab Chip 7, 1515 (2007). 10.1039/b707861g [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chronis N., Zimmer M., and Bargmann C. I., Nat. Methods 4, 727 (2007). 10.1038/nmeth1075 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chokshi T. V., Ben-Yakar A., and Chronis N., Lab Chip 9, 151 (2009). 10.1039/b807345g [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo S. X., Bourgeois F., Chokshi T., Durr N. J., Hilliard M. A., Chronis N., and Ben-Yakar A., Nat. Methods 5, 531 (2008). 10.1038/nmeth.1203 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rohde C. B., Zeng F., Gonzalez-Rubio R., Angel M., and Yanik M. F., Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 104, 13891 (2007). 10.1073/pnas.0706513104 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeng F., Rohde C. B., and Yanik M. F., Lab Chip 8, 653 (2008). 10.1039/b804808h [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDonald J. C., Duffy D. C., Anderson J. R., Chiu D. T., Wu H. K., Schueller O. J. A., and Whitesides G. M., Electrophoresis 21, 27 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Unger M. A., Chou H. P., Thorsen T., Scherer A., and Quake S. R., Science 288, 113 (2000). 10.1126/science.288.5463.113 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brenner S., Genetics 77, 71 (1974). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]