Abstract

This study examined associations between self reports of sadness and anger regulation coping, reluctance to express emotion, and physical and relational aggression among two cohorts of predominantly African-American fifth (N = 191; 93 boys and 98 girls) and eighth (N = 167; 73 boys and 94 girls) graders. Multiple regression analyses indicated unique associations between relational aggression and expressive reluctance and sadness regulation coping. In contrast, physical aggression, but not relational aggression, was associated with anger regulation coping. These relations did not differ across gender, but, the strength of the association between anger regulation coping and physical aggression varied by grade. Sadness regulation coping moderated the association between expressive reluctance and relational aggression. Conversely, anger regulation coping moderated the relation between expressive reluctance and physical aggression, however, the strength of this relation differed by gender. These findings have important implications for intervention efforts.

Keywords: physical aggression, relational aggression, emotional awareness, emotional expressiveness, emotion regulation coping

Extensive literature confirms the link between physical aggression and psychosocial maladjustment for boys (e.g., Coie & Dodge, 1998), and more recent research also highlights this relation for girls (e.g., Pepler, Madsen, Webster, & Levene, 2005). Physical aggression in childhood and adolescence predicts difficulties in areas including academic achievement (e.g., Pepler & Craig, 2005), peer relationships (e.g., Barnow, Lucht, & Freyberger, 2005), delinquency and drug use (e.g., Farrell, Sullivan, Esposito, Meyer, & Valois, 2005), and arrest outcomes (Miller-Johnson, Moore, Underwood, & Coie, 2005). Although the aggression literature historically has focused on physical aggression, an important extension of this research is the study of relational aggression (Crick & Grotpeter, 1995).

Relational aggression represents a distinct construct from physical aggression in that harm is inflicted not by physical damage (or threat of physical damage) but by purposely manipulating or damaging the victim's relationships with others (Crick & Grotpeter, 1995). Examples of relational aggression include threatening to withdraw friendship unless a peer complies with specific demands, exclusion from group activities, and spreading rumors or gossip (Crick, Ostrov, & Werner, 2006). Concurrent and longitudinal studies also demonstrate associations between relational aggression and maladjustment among youth including internalizing and externalizing behaviors, struggles in peer relationships, and misbehavior in school (e.g., Crick, 1997; Crick et al., 1999; Crick et al., 2006). Given the range of adjustment difficulties associated with relational aggression, this relatively understudied form of aggression warrants further attention.

The study of relational aggression may be particularly salient during early adolescence as youth spend increasing time with peers relative to adults, and peer support becomes more influential (Prinstein, Boergers & Vernberg, 2001). Supportive peer relationships address developmental needs for belongingness and also offer opportunities to develop adaptive social skills, such as prosocial coping with peer conflict (Yoon, Barton & Taiariol, 2004). Relative to middle childhood, friendships are more intimate in nature and are often characterized by disclosure of personal information with conversational themes including concerns about self-presentation, inclusion by peers, gossip, and evaluation of others (Maccoby, 1988; Parker & Gottman, 1989). Although high rates of personal disclosure emphasize the trust placed in friendships, increased access to personal information also may provide fuel for relational aggression (Prinstein et al., 2001). Advances in social cognition contribute to a climate of social comparison typified by concerns about social status with peers (e.g., Espelage, 2002). Both physical and relational aggression may be used to establish hierarchies and maintain boundaries in friendship and peer contexts (Underwood, 2003), but neither strategy promotes growth in prosocial competence and both are linked to adjustment difficulties. Thus, important areas of focus include identifying individual-level factors associated with physical and relational aggression and a better understanding of whether such factors are common or unique to each form of aggression.

Emotion Regulation and Aggression

Emotion regulation is a key factor implicated in the development of psychopathology that has received considerable attention in prevention and intervention efforts (Ehrenreich, Fairholme & Buzzella, 2007; Izard, 2002; Suveg, Southam-Gerow, Goodman & Kendall, 2007). Some prior efforts focusing on emotion regulation and aggression have distinguished between reactive and proactive functions of aggression (e.g., Dodge & Coie, 1987). Proactive aggression is based on a social learning model with aggression resulting from learned behaviors and functioning to achieve instrumental goals, whereas reactive aggression is based on the anger-frustration theory with aggression resulting as a response to provocation (e.g., perceived threats) (Vitaro & Brendgen, 2005). In comparison, physical and relational aggression are differentiated primarily based on the mechanism of harm (physical damage versus damage to one's relationships), and a number of studies support this distinction (e.g., Crick, 1997; Grotpeter & Crick, 1996; Murray-Close, Ostrov & Crick, 2007). However, little is known about how emotion regulation processes relate to physical and relational aggression.

One aim of the present study was to examine associations between emotion regulation coping and physical and relational aggression. The literature on emotion regulation is replete with discussion of conceptual and theoretical dilemmas, with several researchers attempting clarification (e.g., Campos, Frankel, & Camras, 2004; Cole, Martin, & Dennis, 2004; Eisenberg, Champion, & Ma, 2004). We drew from the definition of emotion regulation that includes emotion as a behavior regulator and a regulated phenomenon (e.g., Campos, Campos & Barrett, 1989; Cole et al., 2004; Cole, Michel & Teti, 1994). As a regulated phenomenon, an adolescent's perceived capacity to control emotional arousal and to adaptively cope with anger or sadness reflects an important aspect of emotion regulation, and measures of sadness and anger regulation coping offer a perspective on this coping ability (Zeman, Shipman, & Suveg, 2002). Researchers also underscore the role of self-perceived capacity in regulating emotions as a key determinant of behavioral responses across situational contexts (John & Gross, 2007).

The functionalist perspective provides a basis for examining associations between distinct emotions (i.e., sadness and anger) and physical and relational forms of aggression (e.g., Barrett, 1998). From this perspective, emotions serve the function of regulating interactions between individuals and their environment, organizing and motivating goal-driven behavior (Campos et al., 1989). For example, an important function of sadness is to communicate the need for social support (e.g., to strengthen social bonds), and key functions of anger include attaining justice or overcoming perceived obstacles in interpersonal contexts (e.g., Witherington & Crichton, 2007). Both relational and physical aggression can be used to achieve anger-driven goals (i.e., to inflict harm in the moment or to planfully seek justice or revenge), and indeed empirical literature indicates that anger (and its regulation) are implicated in both physical and relational aggression (e.g., Crick, 1997; Peled & Moretti, 2007; Toblin, Schwartz, Gorman & Abou-ezzeddine, 2005). However, relational aggression may be unique in its utility to achieve sadness-driven goals including attempts to connect with others and strengthen social bonds (Campos et al., 1989; Conway, 2005; Izard & Ackerman, 2000). An adolescent who engages in relational aggression (e.g., threatens to withdraw friendship to gain compliance with a request, starts gossip that others join in on) may increase social connections, however, this is achieved in a coercive manner that may ultimately undermine friendships or result in being the target of such behavior.

Prior research suggests that difficulty managing sadness is associated with peer-rated aggression, although the composite measure used to assess aggression precluded comparison of physical and relational aggression (Zeman, Shipman & Penza-Clyve, 2001). In addition, low ability to manage anger, but not sadness, has been associated with externalizing symptoms (Zeman et al., 2002). The present study extends the literature by examining how adolescents' ability to regulate discrete emotions of anger and sadness is associated with relational and physical subtypes of aggression in adolescence. We hypothesized that adolescents with high levels of sadness regulation coping would engage in lower frequencies of relational aggression relative to youth with low levels of sadness regulation coping. We also anticipated that adolescents with high levels of anger regulation coping would engage in lower frequencies of both relational and physical aggression.

Emotional Expression and Aggression

A second study aim was to examine associations between reluctance to express emotion and physical and relational aggression. Emotional expression can facilitate social understanding and communication, representing a key aspect of emotional competence (Boone & Buck, 2003; Saarni, 1999). However, expressive reluctance denotes a constrained pattern of social interaction based on not being willing or motivated to express emotion. This constraint operates regardless of the social appropriateness for expressing or not expressing emotions. This construct may have considerable utility because the inhibition of emotional expression limits the extent to which youth can make use of extrinsic support for coping with emotion. We anticipated that youth with high expressive reluctance would engage in higher rates of relational aggression relative to youth with low expressive reluctance. Relational aggression encompasses a number of behaviors that are covert in nature and thus can be implemented without directly confronting others. In fact, one behavior pattern for relational aggressors is to refrain from outwardly expressing emotions to peers, only later to cope with subjective negative experiences by engaging in less overt, relationally aggressive methods such as social exclusion or gossip (Underwood, 2003). Therefore, for individuals who inhibit emotional expression, relational aggression may serve as a vehicle to more covertly achieve social goals or retaliate against perceived interpersonal slights.

Interactions of Emotion Regulation and Emotional Expression

Eisenberg et al. (2003) suggest that the appropriateness of emotional expression depends on understanding social rules for expressing emotions across social contexts, and that youth with low or high levels of emotional expressivity may be at risk for maladaptive behavior (e.g., aggression). This may be particularly true when these types of response patterns are paired with difficulty regulating specific emotions. For youth who experience difficulty coping with sadness, emotional expression offers one avenue to communicate social information and elicit support from others (Zeman, Cassano, Perry-Parrish & Stegall, 2006). However, adolescents who inhibit emotional expression and have difficulty managing feelings of sadness may be especially limited in their options for attaining support through prosocial means and be more likely to engage in relational aggression. Relations between expressive reluctance and physical aggression also were anticipated to vary by levels of anger regulation coping. Physical aggression represents overt behaviors with the function of inflicting physical harm. Research demonstrates that youth with difficulty regulating anger are more likely to engage in externalizing behaviors (e.g., Eisenberg et al., 2001; Zeman et al., 2002) and this may be intensified for youth who are not motivated to inhibit emotional expression (e.g., Underwood, Coie & Herbsman, 1992). We anticipated that youth with low expressive reluctance and low levels of anger regulation coping would engage in higher rates of physical aggression relative to adolescents with high expressive reluctance and low levels of anger regulation coping.

Age and Gender Effects

A final study aim was to test potential moderating roles of grade and gender on associations between emotion and aggression variables. Study cohorts include youth at the beginning (fifth grade) and end (eighth grade) of early adolescence. Social developmental changes such as increasing emotional disclosure to peers relative to parents from fifth to eighth grade (e.g., Zeman & Shipman, 1997) highlight the relevance of regulating emotions within the peer context in early adolescence. Some literature suggests that the understanding of social rules for emotion regulation reaches a plateau in fifth grade (Gnepp & Hess, 1986). However, youth increase coping strategies and problem-solving abilities to effectively manage emotional arousal during early adolescence (e.g., Saarni, 1999; Zeman & Shipman, 1997). Unfortunately, relatively few studies address developmental changes in interrelations between emotion regulation and expression and relational aggression during adolescence (e.g., Conway, 2005), particularly for African American youth. The literature on gender differences in the regulation and expression of emotion offers mixed findings. Some researchers highlight that relationally aggressive youth are reluctant to express emotion due to cultural socialization that may be more pertinent for girls (Underwood, 2003). From an early age, socialization patterns may promote suppression of anger for girls (e.g., Zahn-Waxler, Klimes-Dougan & Slattery, 2000), and girls may also anticipate more negative responses relative to boys when emotions of sadness and anger are expressed (Underwood, 1997). Other research including African American and European American adolescents suggests girls are more likely than boys to express emotions such as anger and sadness in direct, verbal communication (e.g., Tangney, Becker & Barlow, 1996; Underwood et al., 1992; Zeman & Shipman, 1996). Furthermore, although research indicates that girls endorse greater emotional expression than do boys as a response to stress (Connor-Smith, Compas, Wadsworth, Thomsen, & Saltzman, 2000), other research suggests no gender differences with regard to inhibition of expression or “expressive reluctance” (e.g., Penza-Clyve & Zeman, 2002). Given that literature findings are inconclusive with regard to gender differences on the key emotion constructs of interest in this study, and because few studies shed light on moderating effects for grade and gender on associations between emotion regulation and relational aggression, we did not explicitly hypothesize moderating effects for grade and gender in our analyses. However, considering that developmental context (both gender and age) may influence the constructs under investigation we explored gender and grade as potential moderators in our analyses.

The Present Study

The present study extends prior research in several ways. Unlike many studies examining associations between emotion and aggression constructs, this study focused on African American adolescents living in a low socioeconomic inner-city context. Prior research highlights the importance of further examining the interrelation between emotion and aggression among African American youth (e.g., Hubbard, 2001), and supports the relevance of examining distinctions between relational and physical aggression in this understudied population (Miller-Johnson et al., 2005; Xie, Farmer & Cairns, 2003). The effects of emotion regulation processes are influenced by cultural and socioecological contexts (Raver, 2004), and African-American youth in poor urban environments often face a convergence of stressors based on structural neighborhood characteristics (e.g., high crime rates and economic strain) and other ecological factors (Farrell et al., 2007). This study may also provide information about the generalizability of studies focusing on emotion regulation coping, emotional expression or relational aggression that have been conducted with middle-class, European-American samples. Furthermore, relatively few studies have examined associations between emotion regulation and expression in adolescence.

Method

Participants

Participants included a total of 358 youth representing two cohorts of 191 fifth (M = 10.7 yrs, SD = 0.6) and 167 eighth graders (M = 13.7 yrs, SD = 0.8) who were part of a larger longitudinal study that examined associations between exposure to violence, stress and coping processes, and adjustment. Nearly half (46%) of the sample was male (166 boys, 192 girls), and 92% of participants identified themselves as African American. Participants were recruited from Richmond, Virginia; a community with a large population of African American adolescents living in neighborhoods with high rates of crime and violence. U.S. Census data from 2000 indicate that 61% of 15 to 24 year olds in Richmond were African American, and 61% of children lived in neighborhoods classified as high in poverty (Kids Count, 2004).

Participants were recruited from neighborhoods in the Richmond area that had high levels of violence and/or poverty based on police statistics and census data (e.g., DeNavas-Walt, Proctor, & Lee, 2005). For example, participants were recruited from neighborhoods that had low-income housing, and most of these neighborhoods also had higher levels of crime relative to other areas of the city. There was some diversity in terms of socioeconomic status. Approximately one-third (34%) of the families had a weekly household income of $300 or less; 29% earned $600 or more per week. The median household income was $401-$500 per week which translates into a yearly income level of $20,852-$26,000 per year. Primary maternal caregivers included the adolescent's biological mother (86%), biological grandmother (7%), adoptive mother or step-mother (3%), and females endorsing other categories (4%); however, a range of family structures was represented in the sample, although many (41%) of the caregivers had never married. Thirty-two percent of caregivers were married or cohabitating at the time of the study, 14% were separated, 11% were divorced, and 2% were widowed. About a quarter (23%) of the caregivers had not completed high school, 31% had completed high school or had a general education diploma, 24% had some education beyond high school but had not completed a post high school degree, and 22% had completed either an Associate's (6%), Vocational (7%), Bachelor's (7%) or Master's (2%) degree.

Measures

Physical and Relational Aggression - were assessed using two subscales of the Problem Behavior Frequency Scales (Farrell, Kung, White, & Valois, 2000). Students indicated how frequently they engaged in specific aggressive behaviors in the past 30 days using a six-point scale: 0 = Never, 1 = 1-2 times, 2 = 3-5 times, 3 = 6-9 times, 4 = 10-19 times, and 5 = 20 times or more. The Physical Aggression subscale included seven items based on the Centers for Disease Control's Youth Risk Behavior Survey (e.g., “hit or slapped another kid”, “threatened someone with a weapon”) (Kolbe, Kann, & Collins, 1993). The six items representing relational aggression (e.g., “left another kid out on purpose when it was time to do an activity”, “tried to keep others from liking another kid by saying mean things about him or her”) were based on Crick and Grotpeter's (1995) measure of relational aggression. The response format was changed to reflect the frequency of these behaviors in the past 30 days, and, “Spread a false rumor about someone” and “Said something about another kid to make others laugh” were added to the Relational Aggression scale. The alpha coefficients for the Physical and Relational Aggression scales were .77 and .66, respectively.

Expressive Reluctance - was assessed using a subscale of the Emotion Expression Scale for Children (EESC; Penza-Clyve & Zeman, 2002). Youth responded to each item using a 5-point scale: 1 = Not at all true, 2 = A little true, 3 = Somewhat true, 4 = Very true, and 5 = Extremely true. The Expressive Reluctance subscale included eight items that assessed difficulty in communicating emotions to others (e.g., “I prefer to keep my feelings to myself”, “When I get upset, I am afraid to show it”) (Penza-Clyve & Zeman, 2002). The alpha coefficient for this scale was .70.

Emotion Regulation Coping -was assessed using the Anger and Sadness Regulation Coping subscales from the Children's Anger Management Scale (CAMS) and the Children's Sadness Management Scale (CSMS) (Zeman et al., 2001; Zeman et al., 2002). Validation studies indicated the CAMS and CSMS are negatively related to scores on the Child Depression Inventory (CDI) and the State-Trait Anxiety Inventory for Children (STAI-C) (Zeman et al., 2001; Zeman et al., 2002). Youth responded to each item using a 3-point scale: 1 = Hardly ever, 2 = Sometimes, and 3 = Often. The Anger Regulation Coping subscale included four items that assessed the ability to effectively manage and cope with feelings of anger (i.e., “When I am feeling mad, I control my temper”, “I stay calm and keep my cool when I am feeling mad”, “I can stop myself from losing my temper”, and “I try to calmly deal with what is making me mad”). Four items from the Sadness Regulation Coping subscale assessed the ability to effectively manage and cope with feelings of sadness (i.e., “When I am feeling sad, I control my crying and carrying on”, “I stay calm and don't let sad things get to me”, “I can stop myself from losing control over my sad feelings”, and “I try to calmly deal with what is making me feel sad”). Alpha coefficients for the Anger Regulation Coping subscale and the Sadness Regulation Coping subscale were .61 and .65, respectively.

Procedure

Participants were recruited through community agencies and events, and by canvassing qualifying neighborhoods via flyers posted door-to-door. Respondents were screened for eligibility over the telephone. To be eligible, participants had to have a fifth or eighth grader living in the home, and a female caregiver needed to participate in the interview. Only English-speaking participants were recruited into the study. Eligible respondents were scheduled for interviews, which were conducted in participants' homes unless a family requested to be interviewed elsewhere. Sixty-three percent of eligible participants agreed to be in the study, which is consistent with studies using similar designs and populations.

Interviewers thoroughly reviewed the parental consent and student assent forms with the family, and answered any questions. The caregiver received a copy of the signed consent form. After the maternal caregiver provided written consent, the parent and child separated for the interviews. Youth assent was provided by the child before initiating this interview. Participants agreed to participate in an ongoing series of three annual interviews that are currently in progress, and data for this study represent the first wave of data collection. Face-to-face interviews using visual aids were used to collect the data, and all questions were read aloud, with the exception of a small portion of the student interview. Students who had passed a reading screening test answered several (primarily sensitive) questions in a booklet without interviewer assistance. Tests for interviewer race and gender effects revealed no systematic biases, ps > .10. Interviews with the caregiver and child lasted approximately 2.5 hours and participants received $50 in gift cards per family.

Results

Prevalence of physical and relational aggression

For both physical and relational aggression, approximately three-fourths of the youth reported engaging in one aggressive act in the last 30 days. Also, 39% and 56% of adolescents indicated engaging in multiple acts of relational and physical aggression during this timeframe, respectively. For physical aggression, prevalence rates ranged from 4% for threatening someone with a weapon to 54% for pushing or shoving another kid. Boys and girls reported similar levels of physical aggression with the exception that boys reported pushing or shoving another kid more frequently than did girls, F(1,353) = 4.8, p < .05. Fifth graders reported higher rates of being in a fight where someone was hit, F(1,355) = 5.2, p < .05, as compared to eighth graders, but otherwise rates of physical aggression were similar across grade1.

For relational aggression, prevalence rates ranged from 9% for telling another kid you wouldn't like them unless they did what you wanted them to do to 58% for saying something about another kid to make others laugh. Girls reported not letting another youth be part of their group because they were mad at them more frequently than did boys, F(1,355) = 8.1, p < .01. In contrast, boys reported saying something about another kid to make others laugh more frequently than did girls over the past 30 days, F(1,356) = 6.1, p < .05. No other gender differences were found across the relational aggression items. Fifth graders reported higher rates than eighth graders for not letting another student be part of their group because they were mad at them, F(1,355) = 16.2, p < .001, spreading a false rumor about someone, F(1,356) = 10.2, p < .01, and leaving another student out on purpose when it was time to do an activity, F(1,350) = 5.1, p < .05.

Descriptive Statistics and Zero-order Associations among the Emotion Regulation Coping, Expressive Reluctance, and Physical and Relational Aggression Variables

Means, standard deviations, and intercorrelations among the emotion and aggression variables are presented in Tables 1 and 2. Analyses of variance (ANOVAs) revealed few differences in the study variables across gender and grade. Boys reported higher levels of sadness regulation coping, F(1,347) = 17.8, p < .001 than did girls. For the intercorrelations, a per-test significance level of p < .005 was established based on a multi-stage Bonferroni with a family-wise Type I error rate of p < .10. Based on this per-test significance level, physical and relational forms of aggression were significantly correlated with all study variables with the exception of a non-significant correlation between physical aggression and expressive reluctance. The emotion regulation coping variables (anger and sadness) were significantly related to each other.

Table 1.

Means, Standard Deviations, and Observed Ranges for Emotion and Aggression Variables by Gender and Grade.

| Total | Boys | Girls | Fifth Graders | Eighth Graders | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | F | M | SD | M | SD | F | Range | |

| Physical Aggression | 10.6 | 4.3 | 11.1 | 4.6 | 10.3 | 4.0 | 3.0 | 10.3 | 3.7 | 11.0 | 4.9 | 2.8 | 7-32 |

| Relational Aggression | 8.6 | 3.4 | 8.7 | 3.3 | 8.6 | 3.5 | 0.1 | 8.9 | 3.7 | 8.3 | 3.0 | 2.5 | 6-27 |

| Expressive Reluctance | 20.9 | 6.4 | 21.5 | 6.2 | 20.4 | 6.6 | 2.5 | 21.4 | 6.6 | 20.4 | 6.2 | 2.0 | 8-40 |

| Sadness Regulation Coping | 8.5 | 1.9 | 8.9 | 2.1 | 8.1 | 1.7 | 17.8*** | 8.6 | 2.0 | 8.4 | 1.8 | 0.8 | 4-12 |

| Anger Regulation Coping | 8.5 | 1.9 | 8.6 | 2.0 | 8.5 | 1.7 | 0.4 | 8.6 | 1.9 | 8.5 | 1.8 | 0.3 | 4-12 |

p < .05

p < .01

p < .001

Table 2.

Zero-Order Correlations among Physical and Relational Aggression and Emotion Regulation Coping and Expressive Reluctance

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Relational Aggression | ---- | |||||

| 2. Physical Aggression | 0.61* | ---- | ||||

| 3. Anger Regulation Coping | -0.22* | -0.26* | ---- | |||

| 4. Sadness Regulation Coping | -0.25* | -0.16* | 0.44* | ---- | ||

| 5. Expressive Reluctance | 0.18* | 0.09 | -0.05 | -0.04 | ---- | |

| 6. Gender | -0.02 | -0.09 | -0.03 | -0.22* | -0.08 | ---- |

| 7. Grade | -0.08 | 0.09 | -0.03 | -0.05 | -0.07 | 0.05 |

Note: Per-test significance level of p < .005 is based on a multi-stage Bonferroni correction with a family-wise error rate of p < .10.

Associations of Emotion Regulation Coping and Expressive Reluctance with Physical and Relational Aggression by Gender and Grade

Hierarchical regression analyses were used to examine the associations of anger and sadness regulation coping and expressive reluctance with physical and relational aggression (see Table 3). Separate analyses were conducted for physical and relational aggression. Gender and grade differences in these relations were also examined. For all analyses, the emotion variables were centered at the mean, and the high and low scores plotted in the figures represent one standard deviation above and below the mean. Gender and grade variables were dummy-coded. Aggression variables were log transformed to normalize their distribution and multiplied by 10 to facilitate reporting. At Step 1, gender, grade, and the non-focal form of aggression (i.e., relational or physical) were entered. The three emotion variables (emotion coping and expressive reluctance) were entered at Step 2. Next, the two-way gender and grade interactions were entered for each emotion variable at Step 3, followed by the three-way Gender X Grade X Emotion Variable interactions entered at Step 4.

Table 3.

Summary of Hierarchical Regression Analyses using Emotion Regulation Coping and Reluctance to Express Emotion to Concurrently Predict Physical and Relational Aggression by Gender and Grade

| Relational Aggression | Physical Aggression | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B | SEB | β | ΔR2 | B | SEB | β | ΔR2 | |

| 1. Gender | 0.12 | 0.12 | 0.04 | 0.39*** | -0.27 | 0.13 | -0.09* | 0.39*** |

| Grade | -0.36 | 0.12 | -0.13** | 0.39 | 0.13 | 0.13** | ||

| Non-focal Aggression | 0.57 | 0.04 | 0.62*** | 0.67 | 0.05 | 0.61*** | ||

| 2. Anger Regulation Coping | -0.02 | 0.04 | -0.03 | 0.03*** | -0.12 | 0.04 | -0.15** | 0.02* |

| Sadness Regulation Coping | -0.09 | 0.03 | -0.13** | 0.02 | 0.04 | 0.03 | ||

| Expressive Reluctance | 0.02 | 0.01 | 0.11** | 0.00 | 0.01 | -0.01 | ||

| 3. Gender X Anger Regulation Coping | -0.03 | 0.07 | -0.02 | 0.01 | 0.06 | 0.08 | 0.05 | 0.02 |

| Gender X Sadness Regulation Coping | 0.06 | 0.07 | 0.05 | -0.11 | 0.08 | -0.09 | ||

| Gender X Expressive Reluctance | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.05 | 0.01 | 0.02 | 0.04 | ||

| Grade X Anger Regulation Coping | 0.05 | 0.07 | 0.04 | -0.22 | 0.08 | -0.19** | ||

| Grade X Sadness Regulation Coping | 0.02 | 0.07 | 0.02 | 0.09 | 0.07 | 0.08 | ||

| Grade X Expressive Reluctance | -0.03 | 0.02 | -0.08 | 0.01 | 0.02 | 0.02 | ||

| 4. Gender X Grade X Anger Regulation Coping | 0.06 | 0.14 | 0.04 | 0.00 | 0.07 | 0.15 | 0.04 | 0.00 |

| Gender X Grade X Sadness Regulation Coping | 0.00 | 0.14 | 0.00 | -0.19 | 0.15 | -0.09 | ||

| Gender X Grade X Expressive Reluctance | 0.00 | 0.04 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.04 | 0.02 | ||

p < .05

p < .01

p < .001

For relational aggression, a significant main effect was found for grade with fifth graders reporting higher levels of relational aggression than eighth graders. However, similar levels of relational aggression were reported across gender. Relational aggression was also positively associated with physical aggression. Adolescents who reported higher rates of sadness regulation coping engaged in lower frequencies of relational aggression as compared to those with lower rates of sadness regulation coping. In comparison, expressive reluctance was positively related to relational aggression. Neither the two-way interactions with gender or grade nor the three-way Gender X Grade X Emotion Variable interactions were significant.

For physical aggression, significant main effects were found for gender and grade with boys and eighth graders reporting higher levels of physical aggression than girls and fifth graders, respectively. In comparison to adolescents who reported lower levels of anger regulation, youth with higher levels of anger regulation coping exhibited significantly lower frequencies of physical aggression. One significant two-way interaction, Grade X Anger Regulation Coping was found. At high levels of anger regulation coping, rates of physical aggression were similar for fifth and eighth graders. However, at low levels of anger regulation coping, eighth graders reported higher frequencies of physical aggression than fifth graders. No other two-way interactions or three-way interactions were significant.

Interactive Effects of Sadness and Anger Regulation Coping and Expressive Reluctance on Physical and Relational Aggression

Two hierarchical regression analyses were run to test specific hypotheses about interaction effects between regulating specific emotions, expressive reluctance, and physical and relational aggression. Gender, grade, and the non-focal form of aggression were entered at the first step followed by the two emotion variables of interest at Step 2. The two-way gender and grade interactions by these emotion variables were entered at Step 3 and the Emotion Regulation Coping X Expressive Reluctance interaction was entered at Step 4. The three-way gender and grade interactions by Emotion Regulation Coping and Expressive Reluctance were entered at the final step.

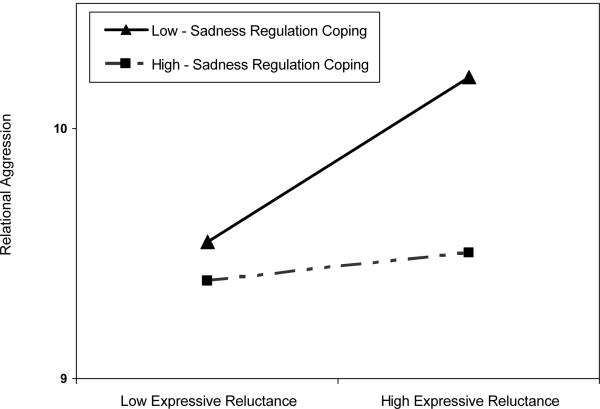

A significant two-way interaction was found for Sadness Regulation Coping X Expressive Reluctance for relational aggression (see Table 4). Post-hoc tests of simple slopes (Aiken & West, 1991) revealed that the regression line for high sadness regulation coping did not differ from zero; however, the regression line for low sadness regulation coping was significantly different from zero. As Figure 1 illustrates, for youth with high levels of sadness regulation coping, little change was found in the frequency of relational aggression as a function of expressive reluctance. However, for youth with low levels of sadness regulation coping, higher levels of expressive reluctance were related to higher frequencies of relational aggression.

Table 4.

Effects of Emotion Regulation Coping on Relations between Reluctance to Express Emotion and Relational Aggression

| Relational Aggression | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| B | SEB | β | ΔR2 | |

| 1. Gender | 0.13 | 0.12 | 0.05 | 0.39*** |

| Grade | -0.37 | 0.12 | -0.13** | |

| Physical Aggression | 0.57 | 0.04 | 0.62*** | |

| 2. Sadness Regulation Coping | -0.10 | 0.03 | -0.15** | 0.03*** |

| Expressive Reluctance | 0.02 | 0.01 | 0.11* | |

| 3. Gender X Sadness Regulation Coping | 0.04 | 0.06 | 0.04 | 0.01 |

| Gender X Expressive Reluctance | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.06 | |

| Grade X Sadness Regulation Coping | 0.04 | 0.06 | 0.03 | |

| Grade X Expressive Reluctance | -0.03 | 0.02 | -0.08 | |

| 4. Sadness Regulation Coping X Expressive Reluctance | -0.01 | 0.00 | -0.11* | 0.01* |

| 5. Gender X Sadness Regulation Coping X Expressive Reluctance | 0.00 | 0.01 | 0.03 | 0.00 |

| Grade X Sadness Regulation Coping X Expressive Reluctance | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.06 | |

| Physical Aggression | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Gender | -0.27 | 0.13 | -0.09* | 0.39*** |

| Grade | 0.38 | 0.13 | 0.13** | |

| Relational Aggression | 0.66 | 0.05 | 0.61*** | |

| 2. Anger Regulation Coping | -0.11 | 0.03 | -0.14** | 0.02** |

| Expressive Reluctance | 0.00 | 0.01 | -0.02 | |

| 3. Gender X Anger Regulation Coping | 0.00 | 0.07 | 0.00 | 0.01 |

| Gender X Expressive Reluctance | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.05 | |

| Grade X Anger Regulation Coping | -0.17 | 0.07 | -0.15* | |

| Grade X Expressive Reluctance | 0.00 | 0.02 | 0.01 | |

| 4. Anger Regulation Coping X Expressive Reluctance | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.05 | 0.00 |

| 5. Gender X Anger Regulation Coping X Expressive Reluctance | -0.03 | 0.01 | -0.15* | 0.01* |

| Grade X Anger Regulation Coping X Expressive Reluctance | 0.00 | .01 | -0.02 | |

Figure 1.

Regression lines for relational aggression as a function of expressive reluctance and sadness regulation coping.

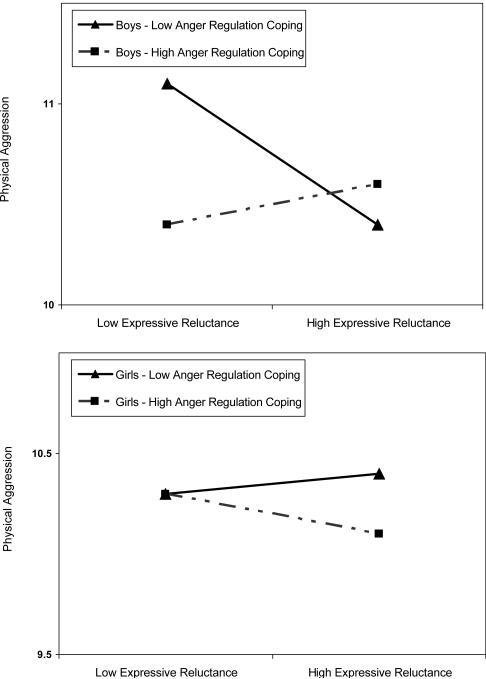

A significant Gender X Anger Regulation Coping X Expressive Reluctance interaction was found for physical aggression (see Table 4). Post-hoc tests of simple slopes revealed that the slope of the regression lines for girls were not significantly different from zero. The slope of the regression line for boys with low but not high levels of anger regulation coping was significantly different from zero. As depicted in Figure 2, among boys with low levels of anger regulation coping, higher rates of physical aggression were found for youth with low as compared to high expressive reluctance.

Figure 2.

Regression lines for physical aggression as a function of expressive reluctance, anger regulation coping, and gender.

Discussion

This study examined associations between anger and sadness regulation coping, expressive reluctance, and relational and physical forms of aggression. Two features that distinguished relational from physical aggression shed light on underlying aspects of emotional competence and emotion regulation. The relatively covert nature of a number of relationally aggressive behaviors allows individuals to perpetrate aggression without directly expressing or indicating observable emotional arousal. Thus, expressive reluctance was conceptualized and emerged as a factor that differentiated relationally aggressive from physically aggressive youth. Also, one social function of relational aggression is to strengthen social connections for perpetrators (at the expense of the victim) and to build social status (e.g., Underwood, 2003). Although social connection has been conceptualized as a sadness-driven goal in the basic emotions literature, many studies of emotion regulation and aggression have focused on anger, given that this emotion is readily conceptualized as the impetus for aggressive acts. This study extends the literature by focusing on associations between sadness regulation coping and aggression. As anticipated, youth with low relative to high levels of sadness regulation coping were more likely to engage in relational aggression. Thus, relational aggression may serve as one strategy, albeit not a prosocial one, for youth who have difficulty coping with sadness to enhance social connections with others.

Sadness regulation coping moderated the association between expressive reluctance and relational aggression. Reluctance to express emotion was associated with higher rates of relational aggression among youth who had difficulty coping with sadness. This finding suggests that the synergistic effect of difficulties with emotional coping (for feelings of sadness) and emotional expression is related to high rates of relational aggression. Although theoretical support for examining associations between sadness regulation coping and expressive reluctance is based on research with girls (e.g., Underwood, 2003), no gender differences were found in this relation. Given that several studies report similar frequencies of relational aggression for boys and girls in adolescent populations (e.g., Prinstein et al., 2001; Sullivan, Farrell & Kliewer, 2006), it is important to identify common factors associated with relational aggression and the processes by which they work across gender. The pattern of difficulties with these aspects of emotion coping and expression also may provide some insight into the mechanisms by which relational aggression and internalizing behavior outcomes are positively related (e.g., Crick, 1997; Crick & Grotpeter, 1996; Murray-Close et al., 2007).

Similar frequencies of physical aggression were found for fifth and eighth graders who reported high levels of anger regulation coping. However, for youth with low levels of anger regulation coping, eighth graders reported higher frequencies of physical aggression relative to fifth graders. Although some researchers note declining trajectories of physical aggression into early adolescence (e.g., Côté, Vaillancourt, Barker, Nagin & Tremblay, 2007), others have found increasing trajectories of physical aggression among urban youth living in disadvantaged neighborhoods that began to level off toward the end of middle school (e.g., Farrell et al., 2005). Results of this study indicated that anger regulation coping was significantly associated with physical but not relational aggression, and positive associations between difficulty coping with anger and physical aggression are supported in the literature (e.g., Orobio de Castro, Merk, Koops, Veerman, & Bosch, 2005; Tangney, Miller, & Flicker, 1996). As skills in emotion regulation continue to be honed during early adolescence, youth who struggle to develop adaptive ways to manage anger may be particularly at risk for physical aggression. The finding that relational aggression was not significantly associated with anger regulation coping was surprising given that concurrent and longitudinal studies have demonstrated positive associations between relational aggression and externalizing behavior (e.g., Crick et al., 2006). Zeman et al. (2001) linked sadness regulation coping to a composite measure of peer-rated aggression and these findings provide further understanding of the specific kinds of aggression that are associated in coping with distinct emotions.

Anger regulation coping moderated the association between expressive reluctance and physical aggression with these relations differing by gender. Among boys who were not reluctant to express their emotions, difficulty adaptively controlling anger expression was associated with increased physical aggression. However, no differences in rates of physical aggression were found for girls as a function of either expressive reluctance or anger regulation coping. Interestingly, other studies conducted with African American youth indicated that boys inhibited anger more frequently than girls (e.g., Underwood et al., 1992), however, findings from this study highlight that the interactive effect of low ability to cope with anger and emotional disinhibition resulted in higher rates of physical aggression for boys. Several studies support associations between components of difficulty with anger regulation and emotional expressivity and physical aggression among boys (e.g., Berkowitz, 1990; Eisenberg et al., 2001; Hubbard et al., 2002). One reason why these associations may vary for girls and boys is because of gender differences in meanings and methods of emotional expression, especially in the context of anger. Although some research indicates that girls are more likely to cope through emotion expression and support seeking (Rose & Rudolf, 2006), prior research failed to find gender differences in rates of expressive reluctance (e.g., Penza-Clyve & Zeman, 2002). Recent meta-analytic findings by Rose and Rudolf (2006) suggest that girls are more likely to endorse connection-oriented goals (e.g., relationship maintenance, prosocial support) whereas boys are more likely to endorse status-oriented and agentic goals (e.g., dominance, revenge, control). Thus, among youth with low anger regulation coping, a willingness to express emotions (low expressive reluctance) may be more strongly associated with physical aggression for those youth with goals that are more typically endorsed by males. Such goals should be considered in future research in order to tease apart the contribution of gender-typed goals from other sex differences. Finally, it is also possible that associations between physical aggression and anger regulation coping may only be significant when a specific level of anger intensity is attained, and that boys may reach this level of anger intensity more frequently than girls. Thus, the anger intensity experienced by boys and girls may provide insight into the differential relations between anger coping and physical aggression across gender.

Overall, these interactions illustrate the way in which expressive reluctance may in fact be a “double-edged sword” for youth in determining associations with externalizing behaviors (e.g., Thompson & Calkins, 1996). That is, the results provide a foundation for future work to explore processes that simultaneously put youth at risk for one type of aggression but also protect youth from engaging in another type of aggression. The results from this study indicate that general measures of ability to manage specific emotions may have some utility for further examining the etiology and maintenance of physical and relational aggression. In addition, expressive reluctance is one facet of emotional competence that might either facilitate or thwart the development of specific subtypes of aggression.

Prevalence rates for aggression indicated that for both physical and relational aggression, approximately three quarters of the sample engaged in at least one act of aggression in the past 30 days, and 39% and 56% reported multiple acts of relational and physical aggression, respectively. For physical aggression, boys reported higher rates of pushing and shoving other children but rates of other behaviors were similar across gender. Although research findings typically demonstrate higher rates of physical aggression among boys than girls, Miller-Johnson et al. (2005) specifically focused on increasing rates of physical aggression among girls growing up in disadvantaged neighborhoods characterized by low socioeconomic status and high rates of crime and violence. Youth living in neighborhoods high in disadvantage reported nearly twice as many stressful events as youth living in moderately disadvantaged neighborhoods (Attar, Guerra, & Tolan, 1994) and also experienced high rates of victimization and witnessing violence (e.g., Gorman-Smith & Tolan, 1998) that may contribute to increased aggressive behavior (e.g., Sullivan, Farrell, Kliewer, Vulin-Reynolds, & Valois, 2007).

Similar frequencies of relational aggression were reported for boys and girls across the majority of items. Several studies conducted with primarily Caucasian samples found that girls reported higher rates of relational aggression relative to boys (e.g., Crick, 1997). Comparatively, other studies including more diverse adolescent samples report similar prevalence rates for relational aggression across gender (e.g., Prinstein et al., 2001; Sullivan et al., 2006). With the inclusion of eighth graders in our sample, similar rates of relational aggression across gender may be related in part to the intensified focus on peer relationships and the movement from primarily same-sex peer groups in late middle-childhood to mixed-sex peer groups in early adolescence (Yoon et al., 2004). However, additional research is needed to more closely examine potential cultural and contextual differences in rates of relational aggression for boys and girls across diverse ethnic samples and socioecological contexts.

Study Limitations and Direction for Future Research

Study results must be interpreted cautiously because of several limitations. First, the measures relied on self-report; thus it is possible that the findings of the current study may be influenced in part by shared method variance. However, we hypothesized differential patterns of associations between related forms of aggression and emotion variables (i.e., physical aggression associated with anger but not sadness regulation coping) that would be unlikely to emerge in the regression analyses if the results were strongly based on a response tendency. Studies have also found that aggressive youth may underestimate how often they engage in aggressive behavior (Lochman & Dodge, 1998) and overestimate their social competence with peers (Brendgen, Vitaro, Turgeon, & Poulin, 2002). Thus, it is possible that in the current study aggressive youth may have underreported these behaviors and this may have attenuated the relations between aggression and emotion constructs.

The absence of peer sociometrics to assess aggression is also a limitation given that peers offer a rich source of information regarding their peers' aggressive behaviors. However, data collected from peers may also represent a sample of behavior that is more limited to aggression occurring during the school day whereas self-report data may span school, neighborhood, and community contexts. In addition, some acts of relational aggression are subtle to the point where only the originator or individuals within a friendship dyad may know about such acts.

Also, causal links between study variables could not be determined because of the cross-sectional design and correlational nature of the data. Prospective studies are needed to establish the causal direction of relations between these emotion and aggression constructs. Second, internal consistencies for relational aggression and anger and sadness regulation coping were relatively low (ranging from .61 to .66), and continued research is needed to examine the cultural and contextual relevance of these measures as most studies in this area focused on middle class, European American samples. In addition, although a number of significant relations were found between the emotion and aggression constructs, many of these relations were modest in size.

Our study extended prior research by its focus on interrelations among emotion variables and physical and relational forms of aggression among a sample of primarily African American adolescents. However, because our sample included a large percentage of youth from low-income households, it is unclear the extent to which our findings generalize to African American youth living in a variety of socioeconomic contexts. This is another important direction for future research. In the current study, we sought to understand how emotion processes were associated with two distinct forms of aggression (i.e., physical and relational). Additional research is needed to address the interplay between the form and function (i.e., aggression that is reactive versus proactive) of these subtypes of aggression (e.g., Little, Jones, Henrich & Hawley, 2003) in relation to the emotion constructs examined in the present study. Future studies might also examine how aspects of temperament (e.g., negative emotionality, behavioral inhibition, and impulsivity) are linked to differential associations between expressive reluctance and physical versus relational forms of aggression.

Finally, although many violence prevention curricula include components on anger management skills focusing on the adaptive regulation and expression of anger (e.g., Farrell, Meyer & White, 2001; Grossman et al., 1997; Taub, 2002), relatively fewer address how to adaptively cope with sadness. Based on study results, one function of relational aggression may be to achieve sadness-driven goals and in this case a component of effectively managing feelings of sadness may serve as an important addition to traditional violence prevention curricula. Study findings may offer relevant information for other health promotion efforts as youth who suppress emotional expression and have difficulty regulating emotions may also be at risk for negative health consequences (Conway, 2005).

Acknowledgments

This research was supported in part by grants 5K01DAO15442 and 5R21DA020086 from the National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA). The research and interpretations reported are the sole responsibility of the authors and are not necessarily endorsed by the NIDA or represent the views, opinions, or policies of the NIDA or their staff.

Footnotes

The interviews were completed throughout the year and we recorded the interview date for each adolescent. We created a dichotomous variable by coding interviews taking place during summer vacation as 0 and interviews taking place during the school year as 1. We ran two ANOVAs to examine differences in physical and relational aggression during the school year as compared to vacation. No significant differences were found in frequencies of physical, F(1,353) = 2.9, p = .10, or relational, F(1,353) = 1.1, p = .30 aggression based on completing the protocol during the school year versus during summer vacation.

References

- Aiken LS, West SG. Multiple regression: Testing and interpreting interactions. Sage Publications, Inc; Thousand Oaks, CA: 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Attar BK, Guerra NG, Tolan PH. Neighborhood disadvantage, stressful life events, and adjustment in urban elementary school children. Journal of Clinical Child Psychology. 1994;23:391–400. [Google Scholar]

- Barnow S, Lucht M, Freyberger H. Correlates of aggressive and delinquent conduct problems in adolescence. Aggressive Behavior. 2005;31:24–39. [Google Scholar]

- Barrett K. A functionalist perspective to the development of emotions. In: Mascolo MF, Griffin S, editors. What develops in emotional development? Plenum Press; New York: 1998. pp. 109–133. [Google Scholar]

- Berkowitz L. On the formation and regulation of anger and aggression: A cognitive-neoassociationistic analysis. American Psychologist. 1990;45:494–503. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.45.4.494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boone RT, Buck R. Emotional expressivity and trustworthiness: The role of nonverbal behavior in the evolution of cooperation. Journal of Nonverbal Behavior. 2003;27:163–182. [Google Scholar]

- Brendgen M, Vitaro F, Turgeon L, Poulin F. Assessing aggressive and depressed children's social relations with classmates and friends: A matter of perspective. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2002;30:609–624. doi: 10.1023/a:1020863730902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campos JJ, Campos RG, Barrett KC. Emergent themes in the study of emotional development and emotion regulation. Developmental Psychology. 1989;25:394–402. [Google Scholar]

- Campos JJ, Frankel CB, Camras L. On the nature of emotion regulation. Child Development. 2004;75:377–394. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2004.00681.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coie JD, Dodge KA. Aggression and antisocial behavior. In: Damon W, Eisenberg N, editors. Handbook of child psychology. 5th ed. vol. 3. John Wiley & Sons, Inc; New Jersey: 1998. pp. 779–862. [Google Scholar]

- Cole PM, Martin SE, Dennis TA. Emotion regulation as a scientific construct: Methodological challenges and directions for child development research. Child Development. 2004;75:317–333. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2004.00673.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cole PM, Michel MK, Teti LO. The development of emotion regulation and dysregulation: A clinical perspective. Monographs of the Society for Research in Child Development. 1994;59(2-3):73–100. 250–283. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Connor-Smith JK, Compas BE, Wadsworth ME, Thomsen AH, Saltzman H. Responses to stress in adolescence: Measurement of coping and involuntary stress responses. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2000;68:976–992. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conway AM. Girls, aggression, and emotion regulation. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry. 2005;75:334–339. doi: 10.1037/0002-9432.75.2.334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Côté SM, Vaillancourt T, Barker ED, Nagin D, Tremblay RE. The joint development of physical and indirect aggression: Predictors of continuity and change during childhood. Development and Psychopathology. 2007;19:37–55. doi: 10.1017/S0954579407070034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crick NR. Engagement in gender normative versus nonnormative forms of aggression: Links to social-psychological adjustment. Developmental Psychology. 1997;33:610–617. doi: 10.1037//0012-1649.33.4.610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crick NR, Grotpeter JK. Relational aggression, gender, and social-psychological adjustment. Child Development. 1995;66:710–722. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1995.tb00900.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crick NR, Grotpeter JK. Children's treatment by peers: Victims of relational and overt aggression. Development and Psychopathology. 1996;8:367–380. [Google Scholar]

- Crick NR, Ostrov JM, Werner NE. A longitudinal study of relational aggression, physical aggression, and children's social-psychological adjustment. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2006;34:131–142. doi: 10.1007/s10802-005-9009-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crick NR, Werner NE, Casas JF, O'Brien KM, Nelson DA, Grotpeter JK, et al. Childhood aggression and gender: A new look at an old problem. In: Dienstbier RA, Bernstein D, editors. Nebraska symposium on motivation: Gender and motivation. University of Nebraska Press; Lincoln, NE: 1999. pp. 75–141. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeNavas-Walt C, Proctor BD, Lee CH. Income, poverty, and health insurance coverage in the United States. U.S. Government Printing Office; Washington, D.C.: U.S. Census Bureau. 2005

- Dodge KA, Coie JD. Social-information-processing factors in reactive and proactive aggression in children's peer groups. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1987;53:1146–1158. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.53.6.1146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ehrenreich JT, Fairholme CP, Buzzella BA. The role of emotion in psychological therapy. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice. 2007;14:422–428. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-2850.2007.00102.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisenberg N, Champion C, Ma Y. Emotion-related regulation: An emerging construct. Merrill-Palmer Quarterly. 2004;50:236–259. [Google Scholar]

- Eisenberg N, Cumberland A, Spinrad TL, Fabes RA, Shepard SA, Reiser M, et al. The relations of regulation and emotionality to children's externalizing and internalizing problem behavior. Child Development. 2001;72:1112–1134. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisenberg N, Zhou Q, Losoya SH, Fabes RA, Shepard SA, Murphy BC, et al. The relations of parenting, effortful control, and ego control to children's emotional expressivity. Child Development. 2003;74:875–895. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Espelage DL. Bullying in early adolescence: The role of the peer group. ERIC Clearinghouse on Elementary and Early Childhood Education; Champaign, IL: 2002. (ERIC Document Reproduction Service No. ED471912) [Google Scholar]

- Farrell AD, Erwin EH, Allison KW, Meyer A, Sullivan T, Camou S, et al. Problematic situations in the lives of urban African American middle school students: A qualitative study. Journal of Research on Adolescence. 2007;17:413–454. [Google Scholar]

- Farrell AD, Kung EM, White KS, Valois R. The structure of self-reported aggression, drug use, and delinquent behaviors during early adolescence. Journal of Clinical Child Psychology. 2000;29:282–292. doi: 10.1207/S15374424jccp2902_13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farrell AD, Meyer AL, White KS. Evaluation of Responding in Peaceful and Positive Ways (RIPP): A school-based prevention program for reducing violence among urban adolescents. Journal of Clinical Child Psychology. 2001;30:451–463. doi: 10.1207/S15374424JCCP3004_02. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farrell AD, Sullivan TN, Esposito LE, Meyer AL, Valois RF. A latent growth curve analysis of the structure of aggression, drug use, and delinquent behaviors and their interrelations over time in urban and rural adolescents. Journal of Research on Adolescence. 2005;15:179–204. [Google Scholar]

- Gnepp J, Hess DL. Children's understanding of verbal and facial display rules. Developmental Psychology. 1986;22:103–108. [Google Scholar]

- Gorman-Smith D, Tolan P. The role of exposure to community violence and developmental problems among inner-city youth. Development and Psychopathology. 1998;10:101–116. doi: 10.1017/s0954579498001539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grossman DC, Neckerman HJ, Koepsell TD, Liu PY, Asher KN, Beland K, et al. Effectiveness of a violence prevention curriculum among children in elementary school. A randomized controlled trial. Journal of the American Medical Association. 1997;277:1605–1611. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grotpeter JK, Crick NR. Relational aggression, overt aggression, and friendship. Child Development. 1996;67:2328–2338. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hubbard JA. Emotion expression processes in children's peer interaction: The role of peer rejection, aggression, and gender. Child Development. 2001;72:1426–1438. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hubbard JA, Smithmyer CM, Ramsden SR, Parker EH, Flanagan KD, Dearing KF, et al. Observational, physiological, and self-report measures of children's anger: Relations to reactive versus proactive aggression. Child Development. 2002;73:1101–1118. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Izard CE. Translating emotion theory and research into preventive interventions. Psychological Bulletin. 2002;128:796–824. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.128.5.796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Izard CE, Ackerman BP. Motivational, organizational, and regulatory functions of discrete emotions. In: Lewis M, Haviland-Jones J, editors. Handbook of emotions. 2nd ed. Guilford Press; New York: 2000. pp. 253–322. [Google Scholar]

- John OP, Gross JJ. Individual differences in emotion regulation. In: Gross J, editor. Handbook of emotion regulation. Guilford Press; New York: 2007. pp. 351–372. [Google Scholar]

- Kids Count. Annie E. Casey Foundation; Baltimore, MD: 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Kolbe LD, Kann L, Collins JL. Overview of the youth risk behavior surveillance system. Public Health Reports. 1993;20S:2–10. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Little TD, Jones SM, Henrich CC, Hawley PH. Disentangling the `whys' from the `whats' of aggressive behaviour. International Journal of Behavioral Development. 2003;27:122–133. [Google Scholar]

- Lochman JE, Dodge KA. Distorted perceptions in dyadic interactions of aggressive and nonaggressive boys: Effects of prior expectations, context, and boys' age. Development and Psychopathology. 1998;10:495–512. doi: 10.1017/s0954579498001710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maccoby EE. Social-emotional development and response to stressors. In: Garmezy N, Rutter M, editors. Stress, coping, and development in children. Johns Hopkins University Press; Baltimore, MD: 1988. pp. 217–234. [Google Scholar]

- Miller-Johnson S, Moore BL, Underwood MK, Coie JD. African-American girls and physical aggression: Does stability of childhood aggression predict later negative outcomes? In: Pepler DJ, Madsen KC, Webster C, Levene KS, editors. The development and treatment of girlhood aggression. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc; Mahwah, NJ: 2005. pp. 75–95. [Google Scholar]

- Murray-Close D, Ostrov JM, Crick NR. A short-term longitudinal study of growth of relational aggression during middle childhood: Associations with gender, friendship intimacy, and internalizing problems. Development and Psychopathology. 2007;19:187–203. doi: 10.1017/S0954579407070101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orobio de Castro B, Merk W, Koops W, Veerman J, Bosch J. Emotions in social information processing and their relations with reactive and proactive aggression in referred aggressive boys. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology. 2005;34:105–116. doi: 10.1207/s15374424jccp3401_10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parker JG, Gottman JM. Social and emotional development in a relational context: Friendship interaction from early childhood to adolescence. In: Berndt T, Ladd G, editors. Peer relationships in child development. John Wiley & Sons; Oxford, England: 1989. pp. 95–131. [Google Scholar]

- Peled M, Moretti MM. Rumination on anger and sadness in adolescence: Fueling of fury and deepening of despair. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology. 2007;36:66–75. doi: 10.1080/15374410709336569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Penza-Clyve S, Zeman J. Initial validation of the Emotion Expression Scale for Children (EESC) Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology. 2002;31:540–547. doi: 10.1207/S15374424JCCP3104_12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pepler DJ, Craig WM. Aggressive girls on troubled trajectories: A developmental perspective. In: Pepler DJ, Madsen KC, Webster C, Levene KS, editors. The development and treatment of girlhood aggression. Lawrence Earlbaum Associates, Inc; Mahwah, NJ: 2005. pp. 3–28. [Google Scholar]

- Pepler DJ, Madsen KC, Webster C, Levene KS, editors. The development and treatment of girlhood aggression. Lawrence Earlbaum Associates, Inc; Mahwah, NJ: 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Prinstein MJ, Boergers J, Vernberg EM. Overt and relational aggression in adolescents: Social-psychological adjustment of aggressors and victims. Journal of Clinical Child Psychology. 2001;30:479–491. doi: 10.1207/S15374424JCCP3004_05. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raver C. Placing emotional self-regulation in sociocultural and socioeconomic contexts. Child Development. 2004;75:346–353. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2004.00676.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rose AJ, Rudolph KD. A review of sex differences in peer relationship processes: Potential trade-offs for the emotional and behavioral development of girls and boys. Psychological Bulletin. 2006;132:98–131. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.132.1.98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saarni C. The development of emotional competence. Guilford Press; New York: 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Sullivan TN, Farrell AD, Kliewer W. Peer victimization in early adolescence: Association between physical and relational victimization and drug use, aggression, and delinquent behaviors among urban middle school students. Development and Psychopathology. 2006;18:119–137. doi: 10.1017/S095457940606007X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sullivan TN, Farrell AD, Kliewer W, Vulin-Reynolds M, Valois RF. Exposure to violence in early adolescence: The impact of self-restraint, witnessing violence, and victimization on aggression and drug use. Journal of Early Adolescence. 2007;27:296–323. [Google Scholar]

- Suveg C, Southam-Gerow MA, Goodman KL, Kendall PC. The role of emotion theory and research in child therapy development. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice. 2007;14:358–371. [Google Scholar]

- Tangney JP, Becker B, Barlow DH. Gender differences in constructive vs. destructive responses to anger across the lifespan. George Mason University; 1996. Unpublished manuscript. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tangney JP, Miller RS, Flicker L. Assessing individual differences in constructive versus destructive responses to anger across the lifespan. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1996;70:780–796. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.70.4.780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taub J. Evaluation of the Second Step violence prevention program at a rural elementary school. School Psychology Review. 2002;31:186–200. [Google Scholar]

- Thompson RA, Calkins SD. The double-edged sword: Emotional regulation for children at risk. Development and Psychopathology. 1996;8:163–182. [Google Scholar]

- Toblin RL, Schwartz D, Gorman AH, Abou-ezzeddine T. Social-cognitive and behavioral attributes of aggressive victims of bullying. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology. 2005;26:329–346. [Google Scholar]

- Underwood MK. Peer social status and children's understanding of the expression and control of positive and negative emotions. Merrill-Palmer Quarterly. 1997;43:610–634. [Google Scholar]

- Underwood MK. Social aggression among girls. Guilford Press; New York: 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Underwood MK, Coie JD, Herbsman CR. Display rules for anger and aggression in school-age children. Child Development. 1992;63:366–380. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vitaro F, Brendgen M. Proactive and reactive aggression: A developmental perspective. In: Tremblay R, Hartup W, Archer J, editors. Developmental origins of aggression. Guilford Press; New York: 2005. pp. 178–201. [Google Scholar]

- Witherington DC, Crichton JA. Frameworks for understanding emotions and their development: Functionalist and dynamic systems approaches. Emotion. 2007;7:628–637. doi: 10.1037/1528-3542.7.3.628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xie H, Farmer TW, Cairns BD. Different forms of aggression among inner-city African-American children: Gender, configurations, and school social networks. Journal of School Psychology. 2003;41:355–375. [Google Scholar]

- Yoon JS, Barton E, Taiariol J. Relational aggression in middle school: Educational implications of developmental research. Journal of Early Adolescence. 2004;24:303–318. [Google Scholar]

- Zahn-Waxler C, Klimes-Dougan B, Slattery MJ. Internalizing problems of childhood and adolescence: Prospects, pitfalls, and progress in understanding the development of anxiety and depression. Development and Psychopathology. 2000;12:443–466. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeman J, Cassano M, Perry-Parrish C, Stegall S. Emotion regulation in children and adolescents. Journal of Developmental & Behavioral Pediatrics. 2006;27:155–168. doi: 10.1097/00004703-200604000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeman J, Shipman K. Children's expression of negative affect: Reasons and methods. Developmental Psychology. 1996;32:842–849. [Google Scholar]

- Zeman J, Shipman K. Social-contextual influences on expectancies for managing anger and sadness: The transition from middle childhood to adolescence. Developmental Psychology. 1997;33:917–924. doi: 10.1037//0012-1649.33.6.917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeman J, Shipman K, Penza-Clyve S. Development and initial validation of the Children's Sadness Management Scale. Journal of Nonverbal Behavior. 2001;25:187–205. [Google Scholar]

- Zeman J, Shipman K, Suveg C. Anger and sadness regulation: Predictions to internalizing and externalizing symptoms in children. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology. 2002;31:393–398. doi: 10.1207/S15374424JCCP3103_11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]