This study coordinates data analysis among central cancer registries in multiple states to examine differences in care between rural and urban areas.

Abstract

Purpose:

A team from Maine, New Hampshire, and Vermont evaluated quality of care for breast and colon cancers in these predominantly rural states.

Methods:

Central cancer registry records from diagnosis years 2003 to 2004 in Maine, New Hampshire, and Vermont were aggregated. Patient residence was classified into three tiers (small rural, large rural, and urban) using Rural-Urban Commuting Area classification.

Results:

Among 6,134 women diagnosed with breast cancer, there were significant differences between rural and urban residents in age (P < .001), stage (P < .001), and tumor size (P = .006). Use of breast-conserving surgery was similar, but sentinel lymph node (SLN) dissection was more common in urban (44.1%) than in large rural (39.9%) and small rural (37.6%) areas. Patients who underwent SLN dissection were more likely to receive radiation therapy after lumpectomy than patients who underwent regional lymph node dissection without SLN (85.9% v 75.5%). However, there was no statistically significant association between the rates of postlumpectomy radiation therapy by residence. Among 2,848 patients with colon cancer, patient characteristics in rural and urban areas were similar, but there were differences in their subsequent surgical treatment (P < .001) and lymph node sampling (P = .079). Adjuvant chemotherapy for patients with stage III colon cancer was less frequent in rural (57.3%) than in urban areas (64.7%; P < .001).

Conclusion:

Central cancer registry data, aggregated among three states, identified differences between rural and urban areas in care for patients with breast and colon cancers. To our knowledge, this is the first time residential category, cancer stage, and treatment data have been analyzed for multiple states using population-based data.

Introduction

A variety of studies have identified limitations in access to cancer screening and treatment among residents of rural locations.1–3 The goal of this project was to assess whether access to oncology care is significantly limited in the predominantly rural northern New England states of Maine, New Hampshire, and Vermont. Members of the Northern New England Clinical Oncology Society (Sandown, NH); the Maine, New Hampshire, and Vermont central cancer registries; the Maine Cancer Consortium (Topsham, ME); Vermonters Taking Action Against Cancer (Williston, VT); and the New Hampshire Comprehensive Cancer Collaboration (Concord, NH) collaborated across state borders for the first time to study indicators of cancer care in rural areas.

For breast cancer, we hypothesized that rural residence is associated with less frequent use of sentinel lymph node (SLN) dissection and postlumpectomy radiation therapy. For colorectal cancer, we hypothesized that rural residence is associated with later stage of cancer at presentation and less frequent use of adjuvant chemotherapy use for stage IIB and III disease.

Methods

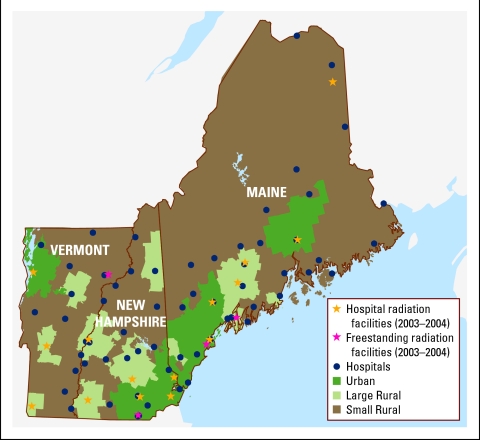

The northern New England area has a total population of 3.2 million.4 There are 79 hospitals in the region: 37 in Maine, 27 in New Hampshire, and 15 in Vermont. According to the Rural-Urban Commuting Area (RUCA) classification scheme,5 25% of these hospitals are located in urban areas, and the remainder are in small (52%) and large (23%) rural locations. During the study period, 2003 to 2004, there were 19 radiation therapy (RT) facilities: eight in Maine, seven in New Hampshire, and four in Vermont (Fig 1). Oncology services are provided in hospital-based oncology practices, three large private oncology practices, two large teaching institutions, and satellite clinics.

Figure 1.

Study region showing type of residence and health care facilities.

By law, states are required to collect data for all cancers diagnosed or treated among their residents. Estimated case completeness for each registry for the study period was 95% or greater (Ali Johnson, personal communication, April 23, 2009). Colon and breast cancer cases were enhanced by obtaining missing data from reporting facilities. In addition to collecting demographic and stage data at diagnosis, for colon cancer cases, we collected details of surgery and chemotherapy within 6 months after diagnosis. For breast cancer, we collected data on SLN dissection, surgical treatment, and RT within 6 months after diagnosis. For legal and logistic reasons, each state provided only aggregate data for the study. An SAS-based analysis program (SAS Version 9.2; SAS Institute, Cary, NC) was developed for each state to extract aggregate data summaries, which were pooled and analyzed.

We defined the residential category of each patient's address using the RUCA classification scheme,5 which uses urbanization, population density, and commuting patterns by zip code. Each patient's residence was assigned to one of three categories: urban, large rural town (large rural), and small rural town (small rural; Fig 1). We then developed an algorithm to assimilate the best available registry information on stage at diagnosis (best stage). In 2004, American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) TNM staging was superseded by the Collaborative Stage (CS).6 According to the best stage algorithm, if the diagnosis year was 2004, we used CS; if the diagnosis year was 2004 and CS was missing, or if the diagnosis year was 2003, we used AJCC TNM pathologic stage; if AJCC pathologic stage was missing, AJCC TNM clinical stage was used.

For stage 0, I, and II breast cancer, the recommended treatment was lumpectomy followed by RT.7–9 Exceptions were patients age 70 years or older, patients with small tumor size (< 1 cm), estrogen receptor antigen–positive patients, and patients with contraindications, including early pregnancy, prior radiation, and connective tissue disorders. Also recommended was SLN dissection to provide accurate axillary staging. SLN surgery was controversial for stage 0 but was the standard of care for stages I and II.10

During 2003 to 2004, the College of American Pathologists and AJCC recommended removing at least 12 lymph nodes for adequate staging of colon cancer.11,12 For stage IIB colon cancer, treatment with adjuvant chemotherapy was controversial. However, ASCO recommendations included consideration of adjuvant chemotherapy in a subset of stage IIB patients, including those who were medically fit, who had been inadequately staged (< 12 nodes examined), and who had high-risk features (eg, T4 lesions, perforation, poorly differentiated histology).13 For stage III colon cancer, surgical resection and adjuvant chemotherapy were recommended.14,15

In describing breast cancer by stage and treatment, we excluded lobular carcinoma in situ cases, those of unknown stage, and those of unknown surgical and radiation treatment. To describe colon cancer by stage and treatment, we excluded cases with unknown stage and unknown surgical and radiation treatment. Comparisons were made using χ2 tests.

Results

Breast Cancer

From 2003 to 2004, 6,134 women were diagnosed with breast cancer. These women had a mean age of 61 years, and 87% had stage 0 to II disease. We saw geographic differences in age at diagnosis (P < .001), with a greater percentage of urban women diagnosed at a younger age (Table 1). Tumor size also showed differences between rural and urban residents (P = .006), with the greatest percentage of patients with larger tumors occurring among residents of small rural areas. Stage also varied geographically (P < .001) but without an easily interpretable pattern. In urban areas, proportionately more patients were diagnosed with stage 0 breast cancer than in rural areas, but fewer were diagnosed with stage I. The combined percentages for stages 0 and I were similar across the three residential categories (59.7%, 63.2%, and 62.7% for small rural, large rural, and urban, respectively). Metastatic disease was seen with similar frequency in small rural and urban areas (3.4% v 3.1%).

Table 1.

Characteristics of 6,134 Northern New England Women Diagnosed With Breast Cancer, 2003 to 2004

| Characteristic | Total |

Small Rural (%; n = 1,777) | Large Rural (%; n = 1,312) | Urban (%; n = 3,045) | P* | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. | % | |||||

| Age at diagnosis, years | <.001 | |||||

| ≤ 49 | 1,491 | 24.3 | 20.4 | 22.3 | 27.4 | |

| 50-64 | 2,232 | 36.4 | 36.0 | 36.7 | 36.5 | |

| 65-74 | 1,192 | 19.4 | 22.4 | 20.0 | 17.4 | |

| ≥ 75 | 1,219 | 19.9 | 21.2 | 20.9 | 18.7 | |

| Mean | 61 | 62 | 62 | 60 | ||

| SD | 13.9 | 13.6 | 13.9 | 14.0 | ||

| Stage at diagnosis | >.001†‡ | |||||

| 0 | 1,344 | 21.9 | 19.0 | 19.1 | 24.8 | |

| I | 2,457 | 40.1 | 40.7 | 44.1 | 37.9 | |

| II | 1,531 | 25.0 | 27.2 | 24.0 | 24.0 | |

| III | 512 | 8.3 | 8.0 | 7.9 | 8.7 | |

| IV | 193 | 3.1 | 3.4 | 2.9 | 3.1 | |

| NA | 20 | 0.3 | 0.3 | 0.5 | 0.3 | |

| Unknown | 77 | 1.3 | 1.3 | 1.4 | 1.2 | |

| Tumor size, cm | .006‡ | |||||

| ≤ 0.5 | 636 | 10.4 | 8.7 | 12.1 | 10.6 | |

| 0.6 to < 1.0 | 799 | 13.0 | 13.7 | 14.6 | 11.9 | |

| 1 to < 2 | 1,897 | 30.9 | 31.2 | 31.3 | 30.6 | |

| 2 to < 5 | 1,530 | 24.9 | 26.6 | 22.9 | 24.8 | |

| ≥ 5 | 385 | 6.3 | 7.0 | 5.2 | 6.3 | |

| Unknown | 887 | 14.5 | 12.7 | 13.9 | 15.7 | |

| Surgery | .146 | |||||

| Lumpectomy | 3,808 | 62.1 | 59.7 | 62.4 | 63.3 | |

| Mastectomy | 1,981 | 32.3 | 34.6 | 32.0 | 31.1 | |

| None | 342 | 5.6 | 5.7 | 5.5 | 5.5 | |

| Unknown/other | 3 | 0.0 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.0 | |

| LN dissection | <.001‡ | |||||

| Sentinel (± regional) | 2,535 | 41.3 | 37.6 | 39.9 | 44.1 | |

| Regional only | 1,793 | 29.2 | 33.5 | 32.6 | 25.3 | |

| None | 1,786 | 29.1 | 28.5 | 27.1 | 30.3 | |

| Unknown | 20 | 0.3 | 0.4 | 0.5 | 0.2 | |

| Positive LNs | .206§ | |||||

| All negative | 3,007 | 49.0 | 49.0 | 51.4 | 48.0 | |

| 1-3 | 928 | 15.1 | 15.9 | 14.5 | 15.0 | |

| 4-9 | 284 | 4.6 | 4.1 | 5.0 | 4.8 | |

| ≥ 10 | 115 | 1.9 | 2.2 | 1.8 | 1.7 | |

| Positive LNs, No. unknown | 16 | 0.3 | 0.2 | 0.1 | 0.4 | |

| No dissection | 1,720 | 28.0 | 27.6 | 26.1 | 29.1 | |

| Unknown if dissected | 64 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.2 | 1.0 | |

| Radiation | .098‡ | |||||

| Yes | 3,123 | 50.9 | 48.7 | 52.0 | 51.7 | |

| No | 3,005 | 49.0 | 51.1 | 47.8 | 48.3 | |

| Unknown | 6 | 0.1 | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.0 | |

Abbreviations: SD, standard deviation; NA, not applicable; LN, lymph node.

χ2 test.

χ2 excludes NA.

χ2 excludes unknown.

χ2 compares all negative LNs v any positive v no LN dissection, excluding unknown.

Overall, 3,808 (62.1%) women underwent lumpectomy, 1,981 (32.3%) underwent mastectomy, and 342 (5.6%) had no surgery. Of the entire cohort, 2,535 (41.3%) had SLN dissection alone or with additional axillary surgery. Although there was no statistically significant difference in breast-conserving surgery by residential category, we observed differences in the patterns of lymph node dissection (P < .001); SLN sampling was performed in 44.1% of urban women, 39.9% of women in large rural areas, and 37.6% of women in small rural areas. The percentages of patients with any positive nodes, all negative nodes, or no dissection performed were independent of residence.

Use of postlumpectomy radiation therapy did not differ by residence. Among the 5,591 women treated surgically, age was associated with use of postoperative RT (Table 2).Women age 75 years or older were significantly less likely than younger women to receive RT after lumpectomy (48.0% v 77.9%) or mastectomy (10.6% v 23.1%). After lumpectomy, adjuvant RT was significantly more often used among women diagnosed at an earlier stage (0 to II; P < .001). Women with very small (≤ 0.5 cm) or larger (≥ 5 cm) tumors had lower rates of RT after breast-conserving surgery (64.9% and 57.3%, respectively) than women with intermediate-sized tumors (76.4%).

Table 2.

Surgery and Radiation Treatment Among 5,591 Northern New England Women With Breast Cancer Treated With Surgery, 2003 to 2004*

| Characteristic | Total |

Lumpectomy |

Mastectomy |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. | % | No RT (%; n = 1,015) | Postoperative RT (%; n = 2,635) | P† | No RT (%; n = 1,540) | Postoperative RT (%; n = 401) | P† | |

| Age at diagnosis, years | <.001 | <.001 | ||||||

| ≤ 49 | 1,358 | 24.3 | 18.5 | 24.1 | 24.6 | 38.9 | ||

| 50-64 | 2,038 | 36.5 | 28.6 | 41.5 | 33.4 | 34.7 | ||

| 65-75 | 1,118 | 20.0 | 17.4 | 21.8 | 19.6 | 16.2 | ||

| ≥ 75 | 1,077 | 19.3 | 35.5 | 12.6 | 22.3 | 10.2 | ||

| Mean | 61 | 66 | 59 | 62 | 55 | |||

| SD | 13.4 | 15.1 | 11.9 | 14.3 | 13.7 | |||

| Residence at diagnosis | .372 | .729 | ||||||

| Small rural | 1,607 | 28.7 | 29.0 | 27.1 | 31.2 | 29.2 | ||

| Large rural | 1,199 | 21.4 | 20.3 | 22.1 | 21.0 | 21.7 | ||

| Urban | 2,785 | 49.8 | 50.7 | 50.8 | 47.7 | 49.1 | ||

| Stage at diagnosis | <.001‡ | <.001‡ | ||||||

| 0 | 1,159 | 20.7 | 36.9 | 18.4 | 19.3 | 0.2 | ||

| I | 2,407 | 43.1 | 35.0 | 54.9 | 38.5 | 3.0 | ||

| II | 1,473 | 26.3 | 21.1 | 23.1 | 32.4 | 37.9 | ||

| III | 480 | 8.6 | 5.0 | 3.1 | 7.5 | 57.4 | ||

| IV | 72 | 1.3 | 2.0 | 0.4 | 2.3 | 1.5 | ||

| Tumor size, cm | <.001§ | <.001§ | ||||||

| ≤ 0.5 | 598 | 10.7 | 15.1 | 10.7 | 10.2 | 1.2 | ||

| 0.6 to < 1.0 | 776 | 13.9 | 15.5 | 18.0 | 9.0 | 1.5 | ||

| 1 to < 2 | 1,841 | 32.9 | 26.4 | 40.5 | 29.4 | 13.7 | ||

| 2 to < 5 | 1,431 | 25.6 | 21.5 | 20.4 | 31.9 | 45.9 | ||

| ≥ 5 | 325 | 5.8 | 3.2 | 1.6 | 7.9 | 31.9 | ||

| Unknown | 620 | 11.1 | 18.4 | 8.8 | 11.6 | 5.7 | ||

| LN dissection | <.001‖ | <.001‖ | ||||||

| Sentinel (± regional) | 2,514 | 45.0 | 24.5 | 57.6 | 40.3 | 31.7 | ||

| Regional only | 1,760 | 31.5 | 18.9 | 22.5 | 46.3 | 65.3 | ||

| No dissection | 1,303 | 23.3 | 55.9 | 19.8 | 13.2 | 2.5 | ||

| Positive LNs | <.001¶ | <.001¶ | ||||||

| All negative | 2,961 | 53.0 | 28.4 | 63.6 | 60.9 | 14.7 | ||

| 1-3 | 911 | 16.3 | 11.0 | 13.5 | 19.2 | 36.7 | ||

| 4-9 | 254 | 4.5 | 3.1 | 2.2 | 4.1 | 25.2 | ||

| ≥ 10 | 140 | 2.5 | 1.0 | 0.7 | 2.2 | 19.2 | ||

| Positive LNs, No. unknown | 10 | 0.2 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 1.0 | ||

| No dissection | 1,292 | 23.1 | 55.6 | 19.6 | 13.1 | 2.2 | ||

Abbreviations: SD, standard deviation; LN, lymph node.

Excludes patients with unknown stage, unknown surgery, unspecified or unknown radiation treatment, or lobular carcinoma in situ.

χ2 test.

χ2 compares stages 0-II v III-IV.

χ2 compares tumor size < 2 cm v ≥ 2 cm.

χ2 compares sentinel v regional.

χ2 compares any positive v all negative LNs.

The use of adjuvant RT after lumpectomy was positively associated with SLN sampling (P < .001). Women were more likely to have postlumpectomy RT after SLN dissection (with or without regional lymph node dissection; 85.9%) than after regional lymph node dissection alone (75.5%) or in the absence of lymph node sampling (48.0%). Adjuvant RT use was inversely associated with lymph node involvement at diagnosis (P < .001). Among 2,781 women with stage I to III disease treated with lumpectomy (Table 3), residence category was significantly associated with type of lymph node sampling (P < .001) but was not associated with adjuvant RT use. Among 1,941 women who underwent mastectomy, use of postmastectomy RT was significantly associated with age, tumor size, performance of any lymph node dissection, nodal involvement, and late stage (III or IV) disease (all P < .001).

Table 3.

Characteristics of 2,781 Northern New England Women Diagnosed With Stage II or III Breast Cancer Treated With Lumpectomy, 2003 to 2004

| Characteristic | Small Rural |

Large Rural |

Urban |

Total |

P* | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. | % | No. | % | No. | % | No. | % | ||

| Radiation | .642† | ||||||||

| Yes | 609 | 76.2 | 493 | 77.9 | 1,055 | 78.2 | 2,157 | 77.6 | |

| No | 187 | 23.4 | 139 | 22.0 | 294 | 21.8 | 620 | 22.3 | |

χ2 test.

Includes patients treated with unspecified type of radiation; patients unknown to have been treated by radiation (n = 4) not shown and excluded from calculation.

Colon Cancer

Among 2,848 patients with colon cancer (Table 4), we found no residence-based differences in age at diagnosis; 7.4% of patients were diagnosed before age 50 years, and 42.6% of patients were older than age 75 years. The distributions of stage were similar in each of the three RUCA categories. Stage 0 disease was diagnosed in 11.7% of patients, and stage IV disease in 14.5%.

Table 4.

Characteristics of 2,848 Northern New England Patients Diagnosed With Colon Cancer, 2003 to 2004

| Characteristic | Total |

Small Rural (%; n = 950) | Large Rural (%; n = 568) | Urban (%; n = 1330) | P* | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. | % | |||||

| Age at diagnosis, years | 0.361 | |||||

| < 49 | 210 | 7.4 | 7.2 | 8.1 | 7.2 | |

| 50-64 | 665 | 23.3 | 21.9 | 24.6 | 23.8 | |

| 65-74 | 759 | 26.7 | 28.3 | 22.9 | 27.1 | |

| ≥ 75 | 1,214 | 42.6 | 42.6 | 44.4 | 41.9 | |

| Mean | 70 | 70 | 70 | 70 | ||

| SD | 13.2 | 13.1 | 13.4 | 13.1 | ||

| Stage at diagnosis | .666†‡ | |||||

| 0 | 334 | 11.7 | 10.4 | 12.9 | 12.2 | |

| I | 682 | 23.9 | 26.0 | 22.2 | 23.2 | |

| II | 695 | 24.4 | 24.2 | 24.1 | 24.7 | |

| III | 611 | 21.5 | 21.2 | 23.1 | 21.0 | |

| IV | 412 | 14.5 | 14.4 | 14.3 | 14.6 | |

| NA | 16 | 0.6 | 0.3 | 0.7 | 0.7 | |

| Unknown | 98 | 3.4 | 3.5 | 2.8 | 3.7 | |

| Surgery | .625§ | |||||

| Local excision | 332 | 11.7 | 11.5 | 12.3 | 11.5 | |

| Segmental resection | 2,170 | 76.2 | 76.8 | 72.7 | 77.2 | < .001‖ |

| Colectomy | 62 | 2.2 | 1.9 | 2.6 | 2.2 | |

| Other | 43 | 1.5 | 1.8 | 3.0 | 0.7 | |

| No surgery | 240 | 8.4 | 7.9 | 9.3 | 8.4 | |

| Unknown | 1 | 0.0 | 0.1 | 0.0 | 0.0 | |

| LN sampling, No. | .743¶ | |||||

| 1-5 | 329 | 11.6 | 11.9 | 12.1 | 11.1 | |

| 6-11 | 614 | 21.6 | 20.4 | 24.1 | 21.3 | |

| ≥ 12 | 1,219 | 42.8 | 43.5 | 38.6 | 44.1 | .079# |

| No dissection | 593 | 20.8 | 20.5 | 22.0 | 20.5 | |

| No. examined not known | 41 | 1.4 | 1.9 | 1.4 | 1.1 | |

| Unknown | 52 | 1.8 | 1.8 | 1.8 | 1.9 | |

| Chemotherapy | .306‡ | |||||

| Yes | 661 | 23.2 | 21.5 | 23.8 | 24.2 | |

| No | 2,185 | 76.7 | 78.3 | 76.2 | 75.8 | |

| Unknown | 2 | 0.1 | 0.2 | 0.0 | 0.0 | |

Abbreviations: SD, standard deviation; NA, not applicable; LN, lymph node.

χ2 test.

χ2 excludes NA.

χ2 excludes unknown.

χ2 compares no surgery v any surgery, excluding unknown.

χ2 compares segmental resection v other listed surgeries v no surgery.

χ2 compares no dissection v any LN dissection performed, excluding unknown.

χ2 compares ≥ 12 v < 12 LNs dissected, excluding no dissection and unknown.

A comparison of surgical procedures performed on residents of rural and urban areas suggested differences in treatment with segmental resection, another form of surgery, or nonsurgical measures (P < .001). Local excision rates were similar, but segmental resection (representing 76.2% of all procedures) was least frequent in large rural areas (72.7%) and highest in urban areas (77.2%). Colectomy was performed in only 2.2% of patients. An important component of surgery is the number of lymph nodes removed during the procedure. The standard of removing at least 12 lymph nodes was met in 1,219 patients, representing 42.8% of patients (including noninvasive disease and nonsurgically treated patients), 46.8% of the 2,607 patients treated surgically, and 55.3% of the 2,203 surgically treated patients who had any lymph nodes removed. Among patients with colon cancer with any lymph nodes removed, there was a borderline significant geographic difference in the proportions having 12 or more removed (P = .079), with a similar proportion in small rural (56.0%) and urban (56.9%) areas and a smaller proportion (50.6%) in large rural areas.

We studied use of adjuvant chemotherapy among 597 patients with stage III disease and a subset of high-risk stage II patients treated surgically (Table 5). Overall, 54.2% of stage IIB patients received chemotherapy. The percentage was smallest among elderly patients (age ≥ 75 years; 24.1%). Patients younger than age 75 years received chemotherapy 74.4% of the time. Of 525 surgically treated patients with stage III colon cancer, 60.8% received adjuvant chemotherapy. The majority of surgically treated stage III patients (90.9%) were age 50 years or older. In the group of patients age younger than 50 years, 89.6% received chemotherapy. Those age 75 years or older with stage III colon cancer received adjuvant chemotherapy 34.7% of the time. Three fourths of those age 50 to 75 years received chemotherapy. Similar percentages received adjuvant chemotherapy in small (58.3%) and large (55.8%) rural areas. Stage III patients in urban areas received adjuvant chemotherapy more often (64.7%) than those in the small and large rural areas combined (57.3%; P = .001). Combining stages IIB and III, there was no significant difference overall in use of adjuvant chemotherapy between urban (63.4%) and combined rural regions (56.9%).

Table 5.

Receipt of Adjuvant Chemotherapy Among 597 Patients With Stage IIB to III Colon Cancer in Northern New England Treated With Surgery by Stage at Diagnosis, 2003 to 2004

| Chemotherapy | Stage IIB |

Stage III |

Total |

P* | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chemotherapy |

No Chemotherapy |

Chemotherapy |

No Chemotherapy |

Chemotherapy |

No Chemotherapy |

||||||||

| No. | % | No. | % | No. | % | No. | % | No. | % | No. | % | ||

| Age at diagnosis, years | < .001 | ||||||||||||

| < 49 | 6 | 15.4 | 2 | 6.1 | 43 | 13.5 | 5 | 2.4 | 49 | 13.7 | 7 | 2.9 | |

| 50-64 | 17 | 43.6 | 1 | 3.0 | 110 | 34.5 | 22 | 10.7 | 127 | 35.5 | 23 | 9.6 | |

| 65-74 | 9 | 23.1 | 8 | 24.2 | 96 | 30.1 | 47 | 22.8 | 105 | 29.3 | 55 | 23.0 | |

| ≥ 75 | 7 | 17.9 | 22 | 66.7 | 70 | 21.9 | 132 | 64.1 | 77 | 21.5 | 154 | 64.4 | |

| Mean | 76 | 62 | 76 | 64 | 76 | 63 | |||||||

| SD | 11.11 | 11.27 | 10.57 | 12.70 | 10.64 | 12.56 | |||||||

| Residence at diagnosis | .195 | ||||||||||||

| Small rural | 17 | 43.6 | 11 | 33.3 | 94 | 29.5 | 67 | 32.5 | 111 | 31.0 | 78 | 32.6 | .105† |

| Large rural | 3 | 7.7 | 6 | 18.2 | 67 | 21.0 | 53 | 25.7 | 70 | 19.6 | 59 | 24.7 | < .001‡ |

| Urban | 19 | 48.7 | 16 | 48.5 | 158 | 49.5 | 86 | 41.7 | 177 | 49.4 | 102 | 42.7 | |

| Surgery | |||||||||||||

| Local excision | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 2 | 0.6 | 3 | 1.5 | 2 | 0.6 | 3 | 1.3 | |

| Segmental resection | 36 | 92.3 | 30 | 90.9 | 306 | 95.9 | 193 | 93.7 | 342 | 95.5 | 223 | 93.3 | |

| Colectomy | 2 | 5.1 | 0 | 0.0 | 10 | 3.1 | 7 | 3.4 | 12 | 3.4 | 7 | 2.9 | |

| Other | 1 | 2.6 | 3 | 9.1 | 1 | 0.3 | 3 | 1.5 | 2 | 0.6 | 6 | 2.5 | |

| LN sampling, No. | .878 | ||||||||||||

| 1-5 | 8 | 20.5 | 3 | 9.1 | 34 | 10.7 | 26 | 12.6 | 42 | 11.7 | 29 | 12.1 | |

| 6-11 | 9 | 23.1 | 8 | 24.2 | 84 | 26.3 | 58 | 28.2 | 93 | 26.0 | 66 | 27.6 | |

| ≥ 12 | 22 | 56.4 | 22 | 66.7 | 201 | 63.0 | 122 | 59.2 | 223 | 62.3 | 144 | 60.3 | |

Abbreviations: SD, standard deviation; LN, lymph node.

χ2 test based on total of chemotherapy given/not given.

χ2 compares rural (small, large) v urban.

χ2 compares rural (small, large) v urban for stage III cancers only.

Discussion

Among patients with breast cancer, we identified several geographic differences in the distributions of patient age, stage, and tumor size (Table 1). Urban areas had the highest percentages of younger patients and of noninvasive breast cancer (stage 0). However, using aggregate data, we could not determine whether the noninvasive disease occurred preferentially among younger women in urban areas. In contrast with the stage 0 pattern, stage I disease was seen most commonly in large rural (44.1%) and small rural (40.7%) areas. If access to screening were substantially better in urban areas, we might expect to see higher percentages of stage I and stage 0 breast cancer. In contrast with other studies (eg, in northeastern Scotland) in which rural areas saw a higher percentage of patients with colon and lung cancer with advanced disease and diminished survival,16 we found that patients in both small rural and urban areas had similar percentages of stage IV breast cancer at diagnosis, suggesting that rural residence in northern New England was not associated with a significant delay in diagnosis.

Breast-conserving surgery was performed in similar proportions in rural and urban areas, with 62.1% of women undergoing lumpectomy, but there were differences in the pattern of lymph node dissection during the first course of treatment (Tables 1 and 3). Greater proportions of women in urban areas had either SLN sampling or SLN sampling combined with regional node dissection. The data regarding use of SLN sampling alone were still maturing during the study period, and several major centers were actively accruing patients to studies assessing whether regional lymph node dissections were necessary in patients who had SLNs sampled. SLN sampling alone or in combination with regional lymph node dissection was more common in urban (44.1%) than in large (39.9%) and small (37.6%) rural areas.

RT after breast-conserving surgery is an important standard component of care unless precluded by significant comorbid conditions, small noninvasive breast cancer, advanced age, proceeding to mastectomy, and previous RT. Only 48% of patients older than age 75 years received RT after lumpectomy compared with approximately 78% of patients younger than age 75 years (Table 3). Patients treated with lumpectomy were more likely to have RT if they had SLN dissection (85.9%) or SLN sampling with regional sampling (85.9%) than if only regional sampling was performed (75.5%). Although SLN sampling was more common in urban areas, and SLN sampling was associated with higher rates of RT use, we saw no significant difference in postlumpectomy RT rates by geographic region. RT was delivered more frequently in patients with larger tumors, more lymph nodes involved, and stage III disease. These additional factors potentially complicate an assessment of the role of rural and urban residence and could be explored using individual-level data in multivariate analyses.

In contrast with the geographic variations seen among women with breast cancer, patients with colon cancer seemed more homogeneous across residential categories in terms of patient age and stage (Table 4). However, we identified geographic differences in surgical treatment and borderline differences in use of lymph node sampling. Among patients with colon cancer who had any lymph nodes removed, there was a borderline significant geographic difference in the proportions having 12 or more removed (P = .079), with a similar proportion in small rural (56.0%) and urban (56.9%) and a smaller proportion in large rural (50.6%) areas.

For stage IIB and III colon cancer combined, there was no significant difference in use of chemotherapy by residential category. Among those who did or did not receive adjuvant chemotherapy, similar percentages of patients had 12 or more lymph nodes removed (Table 5). In stage III colon cancer alone, delivery of adjuvant therapy was significantly less frequent in small rural and large rural areas combined (57.3%) than in their urban counterparts (64.7%; P < .001). We tried to account for this observation in terms of potential confounding in the data. For instance, age is inversely associated with chemotherapy use, but from Table 4, we see no significant geographic differences in the age distributions. We have no information on comorbid conditions that might have influenced adjuvant chemotherapy use. However, presumably, those unable to receive chemotherapy because of poor performance status would have been unlikely to undergo surgery and so excluded from this analysis. Although we could not do multivariate analyses, we do not find any obvious alternative explanation in our data to account for the geographic difference in adjuvant chemotherapy use. Certainly, the complexity, duration, cost, and travel for 6 to 12 months of adjuvant therapy could affect patients' treatment decisions. Because there is a significant overall survival advantage for adjuvant chemotherapy in stage III colon cancer, it is important to determine why rural patients received adjuvant chemotherapy less often than their urban counterparts.

The study had several limitations. Many factors other than residence determine how an individual accesses medical care, including convenience, availability of a provider, travel time, income, health insurance, and race/ethnicity.17 We only considered the effect of residential category, and for logistic reasons, we used a three-category RUCA-based classification scheme, which is an imperfect proxy for access to services. The concept of rural residence is also complex, multifaceted, and often vague.18 There can be significant variations in the demographics, economics, culture, and environmental characteristics of different rural areas. Large rural towns near urban centers often have more in common with urban than rural areas,19 and in our study region, not all tertiary care centers are located in urban areas. In addition, we did not consider changes in residence before diagnosis that may have affected subsequent health.

For legal and logistic reasons, this study was based on aggregate data pooled from the three states. This lack of individual-level data precluded the use of multivariate analyses to examine and adjust for the effects of confounding variables in the data, and this significantly limited our interpretation of the results. An additional limitation was that AJCC TNM stage, a mandatory variable in Maine and New Hampshire, was required neither by the National Program of Cancer Registries nor by Vermont. For Vermont cases, we assigned TNM stage on the basis of available text, other staging variables, and previously reported TNM stage (if available). It is possible that these regional differences and differences in data collection methods over time affected our best stage variable, despite our best efforts to standardize the data.

Conclusions

To our knowledge, this is the first study to coordinate data analysis among central cancer registries in multiple states to examine differences in care between rural and urban areas. The clinical parameters evaluated served as surrogates for access to care in northern New England.

Although preliminary and based on aggregate data, our results suggest some geographic differences in the characteristics of patients with breast cancer at diagnosis and some differences in use of SLN dissection, which itself was associated with more frequent use of postoperative RT. In contrast, we found relatively few geographic differences at baseline among patients with colon cancer, but there were geographic treatment differences, specifically in type of surgery performed, lymph node sampling, and use of chemotherapy for stage IIB and III disease. Patients from rural areas with stage III disease were less likely to receive adjuvant chemotherapy than their urban counterparts. These differences in care between rural and urban areas should be explored further using individual-level data.

We used clinical benchmarks to evaluate access to care and identified specific areas for improving oncologic care in underserved populations. In the clinical setting, AJCC stage is used to make treatment decisions; however, population-based cancer registry data often lack this detail. The stakeholders in this study obtained additional information to improve the quality of AJCC staging data to better understand treatment received among patients with cancer in the northern New England region. Accurate AJCC staging data in population-based cancer registries will help evaluate the success of future programs designed to increase access to adjuvant therapies, educate patients to make meaningful choices, streamline communication among providers, and bridge service provision between tertiary care centers and rural community hospitals. Efficient use of resources and coordination among stakeholders in northern New England is one way to maintain the fragile delivery system in place.

Acknowledgment

Supported by a 2008 ASCO State Affiliate Grant; by the Northern New England Clinical Oncology Society; and by Centers for Disease Control Cooperative Agreement Numbers U58/CCU000785, U58/DP000798, and U58/DP000800. Its contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the Centers for Disease Control.

Authors' Disclosures of Potential Conflicts of Interest

The authors indicated no potential conflicts of interest.

Author Contributions

Conception and design: Ali Johnson, Judy R. Rees, Molly Schwenn, Castine Verrill, Sai Cherala, Melanie Feinberg, Lisa Rutstein, Johannes C. Nunnink

Administrative support: Sai Cherala, Johannes C. Nunnink

Provision of study materials or patients: Ali Johnson, Molly Schwenn, Castine Verrill, Dawn A. Nicolaides, Sai Cherala, Johannes C. Nunnink

Collection and assembly of data: Ali Johnson, Judy R. Rees, Bruce Riddle, Castine Verrill, Maria O. Celaya, Dawn A. Nicolaides, Sai Cherala, Melanie Feinberg, Ann Gray, Johannes C. Nunnink

Data analysis and interpretation: Ali Johnson, Judy R. Rees, Molly Schwenn, Bruce Riddle, Castine Verrill, Maria O. Celaya, Sai Cherala, Melanie Feinberg, Matthew S. Katz, Johannes C. Nunnink

Manuscript writing: Ali Johnson, Judy R. Rees, Molly Schwenn, Castine Verrill, Maria O. Celaya, Sai Cherala, Melanie Feinberg, Johannes C. Nunnink

Final approval of manuscript: Ali Johnson, Judy R. Rees, Molly Schwenn, Bruce Riddle, Castine Verrill, Maria O. Celaya, Sai Cherala, Melanie Feinberg, Ann Gray, Lisa Rutstein, Matthew S. Katz, Johannes C. Nunnink

References

- 1.Mathews M, West R, Buehler S. How important are out-of-pocket costs to rural patients' cancer care decisions? Can J Rural Med. 2009;14:54–60. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gorey KM, Luginaah IN, Holowaty EJ, et al. Wait times for surgical and adjuvant radiation treatment of breast cancer in Canada and the United States: Greater socioeconomic inequity in America. Clin Invest Med. 2009;32:E239–E249. doi: 10.25011/cim.v32i3.6113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Coughlin SS, Thompson TD, Hall HI, et al. Breast and cervical carcinoma screening practices among women in rural and nonrural areas of the United States, 1998–1999. Cancer. 2002;94:2801–2812. doi: 10.1002/cncr.10577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.US Census Bureau. Annual estimates of the resident population for the United States, regions, states, and Puerto Rico: April 1, 2000 to July 1, 2008 (NST-EST2008-01) http://www.census.gov/popest/states/NST-ann-est.html.

- 5.University of Washington, WWAMI Rural Health Research Center. Using RUCA data. http://depts.washington.edu/uwruca/ruca-uses.php.

- 6.Collaborative Stage Data Collection System. http://www.cancerstaging.org/cstage/about.html.

- 7.Polychemotherapy for early breast cancer. An overview of the randomised trials—Early Breast Cancer Trialists' Collaborative Group. Lancet. 1998;352:930–942. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fisher B, Dignam J, Wolmark N, et al. Lumpectomy and radiation therapy for the treatment of intraductal breast cancer: Findings from National Surgical Adjuvant Breast and Bowel Project B-17. J Clin Oncol. 1998;16:441–452. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1998.16.2.441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Eifel P, Axelson JA, Costa J, et al. J Natl Cancer Inst; National Institutes of Health Consensus Development Conference statement: Adjuvant therapy for breast cancer; November 1–3, 2000; 2001. pp. 979–989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lyman GH, Giuliano AE, Somerfield MR, et al. American Society of Clinical Oncology guideline recommendations for sentinel lymph node biopsy in early-stage breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:7703–7720. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Greene FL, Page DL, et al., editors. ed 6. New York, NY: Springer; 2002. American Joint Committee of Cancer: Cancer Staging Manual; p. 114. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Compton CC, Fielding LP, Burgart LJ, et al. Prognostic factors in colorectal cancer: College of American Pathologists Consensus Statement 1999. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2000;124:979–994. doi: 10.5858/2000-124-0979-PFICC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Benson AB, 3rd, Schrag D, Somerfield MR, et al. American Society of Clinical Oncology recommendations on adjuvant chemotherapy for stage II colon cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22:3408–3419. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.05.063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mamounas E, Wieand S, Wolmark N, et al. Comparative efficacy of adjuvant chemotherapy in patients with Dukes' B versus Dukes' C colon cancer: Results from four National Surgical Adjuvant Breast and Bowel Project adjuvant studies (C-01, C-02, C-03, and C-04) J Clin Oncol. 1999;17:1349–1355. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1999.17.5.1349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.André T, Boni C, Mounedji-Boudiaf L, et al. Oxaliplatin, fluorouracil, and leucovorin as adjuvant treatment for colon cancer. N Engl J Med. 2004;350:2343–2351. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa032709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Campbell NC, Elliott AM, Sharp L, et al. Rural and urban differences in stage at diagnosis of colorectal and lung cancers. Br J Cancer. 2001;84:910–914. doi: 10.1054/bjoc.2000.1708. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Abel AL, Burdine JN, Felix MR. Measures of access to primary health care: Perceptions and reality. http://gateway.nlm.nih.gov/MeetingAbstracts/ma?f=102194440.html. [Google Scholar]

- 18.University of Washington, WWAMI Rural Health Research Center. Rural-urban commuting area codes, Version 2.0. http://depts.washington.edu/uwruca/ruca-data.php.

- 19.Hart LG, Larson EG, Lishner DM. Rural definitions for health policy and research. Am J Public Health. 2005;95:1149–1155. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2004.042432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]