Abstract

Accumulation of noncoding DNA and therefore genome size (C-value) may be under strong selection toward increase of body size accompanied by low metabolic costs. C-value directly affects cell size and specific metabolic rate indirectly. Body size can enlarge through increase of cell size and/or cell number, with small cells having higher metabolic rates. We argue that scaling exponents of interspecific allometries of metabolic rates are by-products of evolutionary diversification of C-values within narrow taxonomic groups, which underlines the participation of cell size and cell number in body size optimization. This optimization leads to an inverse relation between slopes of interspecific allometries of metabolic rates and C-value. To test this prediction we extracted literature data on basal metabolic rate (BMR), body mass, and C-value of mammals and birds representing six and eight orders, respectively. Analysis of covariance revealed significant heterogeneity of the allometric slopes of BMR and C-value in both mammals and birds. As we predicted, the correlation between allometric exponents of BMR and C-value was negative and statistically significant among mammalian and avian orders.

Keywords: allometry, genome size, body size optimization, cell number

The amount of DNA per haploid nucleus, referred to as genome size or the C-value, varies in eukaryotes by more than four orders of magnitude (1). Mechanically, spreading of repetitive noncoding sequences is most often responsible for C-value increase, and the amount of encoded genetic information is much less variable and usually not correlated with the C-value (2, 3). Accumulation of this noncoding DNA is attributed to the “selfishness” of DNA, and many authors consider it selectively almost neutral unless transposon spreading demolishes existing genes (4). Although the costs of producing copies of a bigger genome are obvious, these costs may not be high enough to balance mutation pressure for selfish (parasitic) DNA accumulation. A strong correlation between C-value and cell size exists, however (2, 5). Within a taxon, smaller cells usually divide faster and have a higher metabolic rate, as evidenced by the strong negative correlation between specific metabolic rates corrected for body size and DNA amounts in mammals (6) and birds (7, 8), and by direct measures of erythrocyte metabolism in amphibians (9). In birds there is a strong correlation between erythrocyte size and metabolic rate, with erythrocyte size correlating very strongly with cell sizes in other tissues (8). Advocates of the “selfish DNA” hypothesis for C-value increase argue that organisms with small cells are under stronger pressure to clean up noncoding DNA and to possess more efficient mechanisms limiting the spreading of transposons. Although the relation between C-value and cell size is never perfect, it seems too strong to be explained by this mechanism. Nor can this hypothesis explain instantaneous reductions in cell size after reductions in DNA content (2, 10), and especially an instantaneous increase in cell size after experimental addition of DNA (2). An alternative explanation called nucleoskeletal theory (11) assumes concerted evolution of cell size and C-value: any increase in cell size requires a subsequent increase in nuclear volume to provide a sufficient number of nuclear pores through which RNA can pass into the cytoplasm. This hypothesis also cannot explain instantaneous changes in cell size in response to changes in DNA amount. The most likely explanation at present is an old causative one, called the nucleotypic effect: DNA content directly affects cell size and the cell division rate (12, 13). The mechanism is still hypothetical and probably involves interaction between the function of specific regulatory genes and DNA bulk in cell cycle control (2, 14). In any case, however, because of the link between the C-value or nucleus size and cell volume, changes in the amount of DNA must directly affect cell volume and, unless cell number is simultaneously reduced, must indirectly affect body size and general metabolism. In our view this fundamental relationship underlies scaling of metabolic rate.

The Model

Consider the evolutionary changes of relations between body size and metabolic rate in hypothetical lineages of species originating from ancestral species of similar body size. We restrict the use of the term lineage to a group of closely related species, alive or extinct, sharing the same pattern of adult body size change with respect to change in C-value, and therefore cell size and cell number. Although cells differ in size between tissues, we assume that in all tissues changes in C-value equally affect cell size. This allows us to take into account the “average” cell size in further considerations.

For all lineage members, the pattern of adult body size change with respect to change in C-value results in a common line describing the dependence of log metabolic rate on log adult body size. Adult body mass (w) of a given lineage member can be approximated as

|

where n is the number of cells, and wc is the cell mass. Within-lineage scaling of the standard metabolic rate (R) of the adults can therefore be expressed as

|

where a is a normalization coefficient, and b is the allometric exponent scaling wc to R. Body size in a lineage can shrink or expand through changes in C-value mediating cell size or cell numbers, and the two mechanisms usually work together. Under body expansion exclusively through cell number, we expect body mass to scale to standard metabolic rate as

|

where

|

that is, to increase in direct proportion (isometrically, with a slope of 1, Fig. 1a), because the body is composed of larger numbers of the same units (see Appendix for derivation). A large part of standard metabolic costs are spent preserving ionic gradients on cell membranes (15, 16). Systematic differences in the permeability of cell membranes between lineages of organisms composed of cells of similar size result in different intercepts of allometric scaling (Fig. 1a and refs. 16 and 17). When body expansion is realized chiefly through an increase in C-value and the related increase in cell size, the cell surface-to-volume ratio decreases. All other things being equal, the standard metabolic rate is then expected to increase slower than body volume (and body mass as well). In such a case R scales to w as

|

where b < 1 and β = abn1–b (for derivation see Appendix). For the extreme case with all metabolic costs proportional to cell surface and size expansion strictly linked to C-value and realized exclusively through cell size, the standard metabolic rate of the whole organism would increase in proportion to body volume raised to the 2/3 power (Fig. 1a). Because only part of the costs are proportional to cell surface and part to cell volume, the power must be substantially higher, but <1. If we additionally acknowledge that body size expansion is realized usually simultaneously through an increase in cell number and cell size, we expect that the standard metabolic rate in most lineages will be proportional to body mass raised to a power much closer to 1 than to 2/3, and that the power will differ between lineages because they differ in the participation of C-value, and thus cell size and cell number effects on body size change.

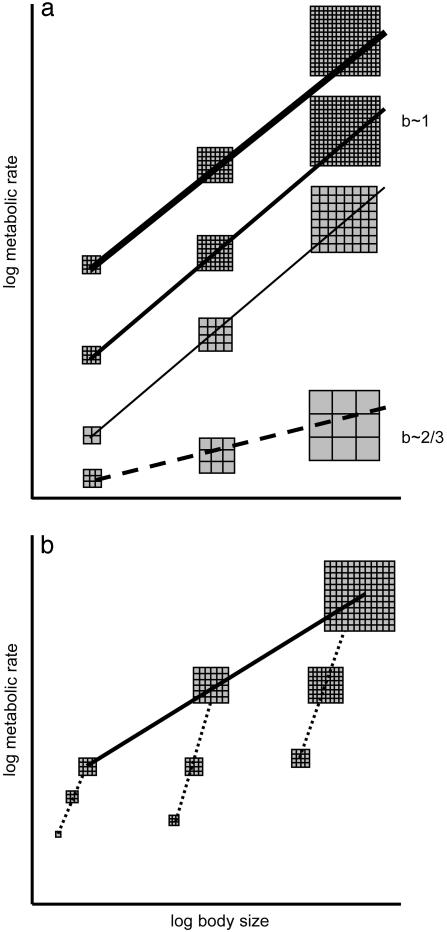

Fig. 1.

(a) The relation between body size and metabolic rate in hypothetical lineages originating from species of similar body size. The uppermost solid line connects hypothetical adult representatives of three species belonging to a lineage. Their body masses are approximated as sums of equal-sized cells depicted as small squares. In this lineage the increase in body size has been realized entirely through an increase of cell number. The second and third (from top) solid lines represent lineages also increasing body size exclusively through cell number increase, but having lower cell membrane permeability (medium solid line) or having larger cells (thin solid line). Both lower cell membrane permeability and larger cells result in lower metabolic costs of maintenance of ionic gradients, and hence a lower metabolic rate reflected in a lower intercept. All three solid lines have a slope ≈1. The dashed line represents a lineage increasing body size entirely through cell size expansion; the allometric slope equals 2/3 if the metabolic rate of larger cells decreases according to the surface-to-volume ratio. (b) Illustration of the difference between the concepts of within-lineage (solid line) and ontogenetic (dashed lines) scaling of metabolic rate. BMR (reflecting metabolic costs of tissue maintenance, but not metabolic costs of tissue production) should scale in ontogenesis with the slope ≈1.

It is important to point out that the lines in Fig. 1a should not be interpreted as ontogenetic changes of metabolic rates with body size. The difference between the concept of scaling of ontogenetic and within-lineage changes of metabolic rates is illustrated in Fig. 1b. Furthermore, the solid lines in Fig. 1 do not strictly reflect within-species allometries. They rather represent evolutionary trajectories of the relationships between metabolic rate and body size, dictated by the relationship between changes in C-value, cell size, cell numbers, and, independently, cell membrane permeability.

From the evolutionary point of view, not all adult body sizes lying on the evolutionary trajectories of within-lineage scaling of metabolic rates depicted in Fig. 1a are optimal. The optimal ones are only those maximizing fitness, measured here as lifetime allocation of resources to reproduction (18). Such optimal body sizes are determined by the dependence of the production and mortality rates on body size (19, 20). The simplest optimization model (for a constant environment and under continuous reproduction after reaching maturity) predicts that the optimal adult body size is the one for which switching from growth to reproduction satisfies the following condition:

|

[1] |

where w is body size in energy units, P(w) is the size-dependent production rate, and m(w) is the size-dependent mortality rate (20, 21). The production rate is the difference between the rate at which resources are acquired, A(w), and the metabolic rate, R(w). The dependence of A(w) on body size may be complex, because it depends not only on the organism's physiology and behavior but also on food availability. In the vicinity of the optimal size satisfying condition 1, A(w) can be approximated by a simple function, for example an allometric equation, which is convenient because the slope will measure the rate of change of the acquisition rate with size.

Let us consider first a set of lineages characterized by exactly the same resource acquisition rate A(w), and exactly the same dependence of mortality on body size. The lineages differ in the relative role of changes in C-value, and thus cell number and cell size increase in expanding body mass. This is reflected by the diversification of within-lineage slopes for metabolic rate (Fig. 2a). It is straightforward that condition 1 is satisfied at smaller adult body sizes for lineages with steeper slopes, because at the same resource acquisition rate the difference between A(w) and R(w) is smaller and therefore P(w) is lower. Fig. 2a illustrates the connection between the within-lineage slopes for metabolic rates and the location of the resulting optimal adult body size for each of the lineages. According to our model these optima should be characteristic for the extant species representing particular lineages. If we draw a line connecting the optimal sizes of species lying on different within-lineage metabolic rate lines, we get the interspecific allometry of adult metabolic rates, as observed on the level of extant taxa. It is important to note that unlike members of the lineage, different species do not share the same pattern of body composition with respect to C-value, cell size, cell number, and cell membrane permeability. Because combinations of these traits resulting in low metabolic rate are associated with larger body sizes, the slope of the interspecific allometry on the taxon level is lower than the within-lineage slopes for metabolic rate (Fig. 2a).

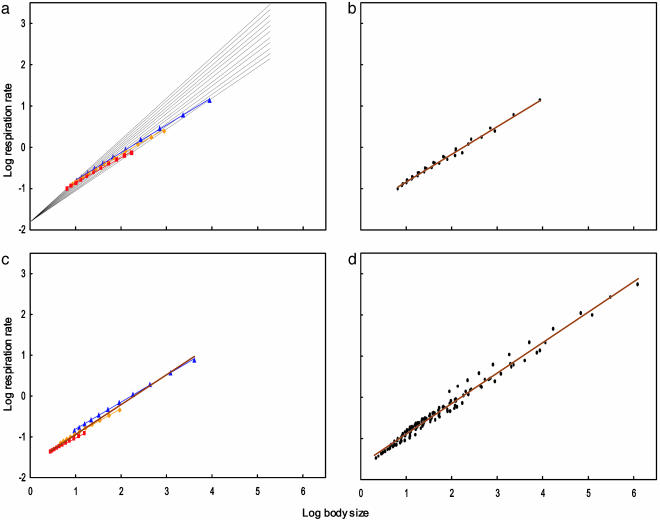

Fig. 2.

Interspecific allometries resulting from body size optimization in lineages differing in their slopes for the dependence of metabolic rate on body size dictated by cell size. (a) Thin black lines depict within-lineage scaling of metabolic rate according to the equation R(w) = 0.015 wb, where b changes from 0.75 to 1.0, which gives the average 0.875; optimal body sizes were calculated with condition 1, assuming that energy acquisition scales as A(w) = 0.05 w.67 and mortality rate scales as m(w) = 0.0015 w–.1 (blue points), m(w) = 0.0015 w0 (orange points), or m(w) = 0.0015 w.1 (red points). Blue points can be well approximated by a straight line with slope 0.67, orange points by a line with slope 0.64, and red points by a line with slope 0.61. These slopes represent interspecific allometries for metabolic rate. Note that all these slopes are much lower than the average within-lineage slope. (b) The same picture as in a, after the lines for within-lineage slopes are removed, and all points for optimal body size are represented with the same color; points are approximated with a common regression line having slope 0.67. Note that the points resemble real data analyzed by students of interspecific allometries for metabolic rate: they do not know the within-lineage slopes for metabolic rate for particular species, and usually they are not aware that the group of species may be nonuniform with respect to other parameters. (c) Like a (after the lines for within-species metabolic rate are removed), but with the resource acquisition rate scaling as 0.05 w.66 (blue points), 0.05 w.58 (orange points), or 0.05 w.50 (red points), and mortality rate as 0.0015 w–.10. Slopes for interspecific allometries are 0.66, 0.62, and 0.60, respectively, and the common slope is 0.73. (d) Data points from a and c, supplemented with points obtained by changing the intercepts of the resource acquisition and mortality rate functions. Common slope is 0.74.

We can go a step further and assume that taxa belonging to a higher taxon differ in the function describing the dependence of mortality on body size. Each taxon will then be characterized by a separate interspecific allometry for metabolic rates, with a distinct slope (Fig. 2a). Interestingly, for exactly the same within-lineage allometries for metabolic rates, taxa differing in mortality scale interspecifically with different slopes. The grand slope for species belonging to the higher taxon is still lower than the average within-lineage slope, but higher than the slopes for all particular taxa (Fig. 2b).

Similar calculations can be performed for the other parameters embedded in condition 1, as shown in Fig. 2c. In fact, we expect that species belonging to different lineages will differ simultaneously in their scaling for metabolic rate, resource acquisition rate, and mortality rate. Fig. 2d represents species with optimal sizes according to condition 1 under different values of the parameters of all these three functions, presented on the body size/metabolic rate plane. The common regression line representing the interspecific allometry has a slope of 0.74, still lower than the average within-lineage slope for metabolic rate equal to 0.875. Points representing particular “optimal species” are scattered around the allometric line, as in real allometric relationships. Although the interspecific general slope 0.74 was obtained by chance with the ranges of parameters assumed in the first trial, we diverged the ranges substantially to study their impact on the slope. It is difficult to get slopes outside 0.7–0.8 without assuming unrealistic parameter values.

Validation of the Model

The cornerstone of our reasoning is that values of allometric scaling of standard metabolic rate with body size are in part determined by the relationship between C-value (and thus cell size) and body size (Fig. 1a). We therefore predict that shallow within-lineage slopes of metabolic scaling should be associated principally with changes of body size through changes in cell size, which implies a substantial increase of C-value with body size. These shallow slopes should be associated with a steep scaling of C-value with body size. Conversely, lower values of allometric slopes of C-value with body size should be associated with little change in cell size, and therefore steeper allometric slopes of metabolic rates. Thus, there should exist a negative interlineage correlation between the slopes of scaling of standard metabolic rate and the slopes of scaling of C-value.

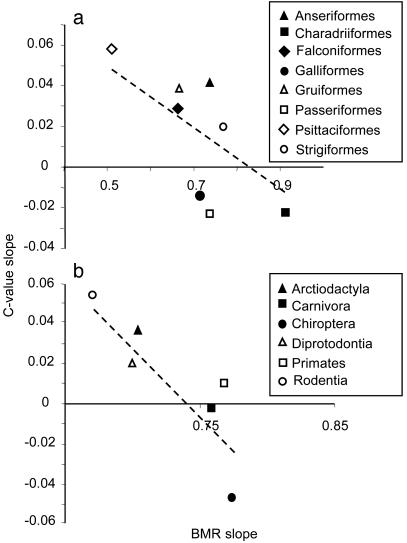

Unfortunately, we are not aware of any data that would be adequate to test this correlation on a lineage level. However, it can be approximated by the correlation between allometric slopes within extant taxonomic groups, roughly conforming to our definition of the lineage. We managed to extract sufficient literature data on basal metabolic rates (BMRs), body mass, and C-value of six orders of mammals and eight orders of birds (sources of data and details of statistics are given in Tables 1 and 2). Analysis of covariance revealed significant heterogeneity of the allometric slopes of BMR and C-value both in mammals (heterogeneity of BMR slopes: F5,383 = 2.45, P = 0.03; heterogeneity of C-value slopes: F5,178 = 2.69, P = 0.02) and birds (heterogeneity of BMR slopes: F7,153 = 3.53, P = 0.002; heterogeneity of C-value slopes: F7,100 = 3.37, P = 0.003). As we predicted, the correlation between the allometric exponents of BMR and C-value were negative and statistically significant for birds (r = –0.72, P = 0.04, Fig. 3a) and mammals (r = –0.83, P = 0.04, Fig. 3b). Interestingly, the slopes of scaling of C-value in some mammalian and avian orders were negative (Fig. 3). This finding suggests that reduction of body mass without simultaneous reduction of cell size prevailed in their evolutionary history. It resulted in low metabolic rates of smaller species, which in turn have resulted in steep scaling of BMR.

Table 1. Slopes of allometries of BMR and C-value on body mass in six orders of mammals.

| Allometry of BMR

|

Allometry of C-value

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Order | Slope ± SE | n | Slope ± SE | n |

| Artiodactyla | 0.70 ± 0.05 | 18 | 0.0036 ± 0.030 | 14 |

| Carnivora | 0.76 ± 0.05 | 33 | -.0015 ± 0.013 | 16 |

| Chiroptera | 0.77 ± 0.03 | 47 | -0.048 ± 0.019 | 26 |

| Diprodontia | 0.70 ± 0.02 | 44 | 0.018 ± 0.016 | 9 |

| Primates | 0.77 ± 0.04 | 18 | 0.010 ± 0.012 | 60 |

| Rodentia | 0.67 ± 0.01 | 255 | 0.058 ± 0.018 | 64 |

All C-value data were from the database compiled by T. R. Gregory (www.genomesize.com). Where more than one estimate of C-value was available, we used the average. Data on BMR (and corresponding body mass) were sourced primarily from ref. 30 and supplemented from refs. 6, 27, and 35-40. To convert BMR from kcal/day to ml O2/h we assumed that 1 liter O2 = 4.8 kcal. For species with no BMR data available, we extracted the data on body mass from refs. 41-44. When body size range was available or body masses were reported separately for males and females, we used the average body mass.

Table 2. Slopes of allometries of BMR and C-value on body mass in eight orders of birds.

| Allometry of BMR

|

Allometry of C-value

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Order | Slope ± SE | n | Slope ± SE | n |

| Anseriformes | 0.73 ± 0.06 | 16 | 0.0041 ± 0.017 | 10 |

| Charadriiformes | 0.89 ± 0.04 | 30 | -0.0024 ± 0.044 | 4 |

| Falconiformes | 0.66 ± 0.04 | 11 | 0.028 ± 0.012 | 19 |

| Galliformes | 0.71 ± 0.04 | 20 | -0.015 ± 0.015 | 9 |

| Gruiformes | 0.66 ± 0.04 | 4 | 0.038 ± 0.010 | 10 |

| Passeriformes | 0.74 ± 0.02 | 56 | -0.028 ± 0.013 | 40 |

| Psittaciformes | 0.59 ± 0.05 | 16 | 0.058 ± 0.023 | 15 |

| Strigiformes | 0.77 ± 0.05 | 16 | 0.020 ± 0.023 | 9 |

All C-value data were from the database compiled by T. R. Gregory (www.genomesize.com). Where more than one estimate of C-value was available, we used the average. Data on BMR (and corresponding body mass) were sourced primarily from ref. 28 and supplemented from refs. 45-47. To convert BMR from kcal/day to ml O2/h we assumed that 1 liter O2 = 4.8 kcal. For species with no data on BMR available, we extracted the data on body mass from ref. 48. When body size range was available or body masses were reported separately for males and females, we calculated the average body mass.

Fig. 3.

Correlation between values of slopes of allometric scaling of BMR and C-values with body mass among eight orders of birds (a) and six orders of mammals (b). Broken lines are type II least-square regressions indicating trends.

Discussion

It is not difficult to imagine selective forces toward high or low metabolic rates dictated by small or large cell sizes. Small cells enable rapid conversion of surplus energy to offspring tissues under food excess, and large cells enable long fasting and some offspring production even under moderate food availability. Szarski (15) calls the first strategy wasteful and the second frugal, with a full continuum in between. This continuum is represented in Fig. 2a by the within-lineage lines for metabolism differing in slopes. Only these slopes require a functional explanation, provided here by the link with cell size and DNA bulk. Interspecific allometries do not need such an explanation. The best examples of frugal and wasteful strategies can be found among amphibians and fishes. Anurans have small cells and small genomes, whereas urodels often have very large cells and huge genomes (22). Some miniature salamanders, especially from the group Bolitoglossini, consist of a relatively low number of very large cells and have some very simplified organs including their brains, a very low metabolic rate, and slow development (23). Lungfishes, which survive long periods under hypoxic conditions, have very low metabolic rates and the largest genomes of all vertebrates (11). Although birds with their small genomes and small cells represent a wasteful strategy, even within this group small C-value correlates with short development time (24) and high metabolic rates (7, 8).

Our conclusions seem to contradict two widely accepted findings: that the standard metabolic rate scales with body mass to the 3/4 power, and that in nature this scaling is almost universal (25). The metabolic rate scales with body mass to the 3/4 power only for phylogenetically diversified interspecific data sets (26), whereas within narrow taxonomic groups or species the slope differs from 3/4 (27–29). We argue that adult body mass is strongly affected by the mechanisms determining the metabolic rate, such as cell size or less directly the C-value. In other words, body mass cannot be treated as an independent variable for the metabolic rate, as these two traits covary under the pressure of natural selection molding the C-value. This finding is strongly supported by tight, negative correlations between the allometric slopes of scaling of C-value and BMR in both birds and mammals (Fig. 3).

The question is therefore whether the 3/4 power law is an empirical fact or an artifact. Recently, Lovegrove (30) studied the BMR scaling of 487 mammalian species. According to our analysis of his data, the general slope is 0.69 but the range of values for orders is from 0.42 (Insectovora) to 0.85 (Carnivora). The slopes differ from 3/4 significantly for all mammals, rodents (also separately for Muridae and Sciuridae), insectivores, and Diprodontia. The lack of significance in other orders means either that the slope is close to 0.75 (e.g., bats: 0.79, 42 species) or that the number of degrees of freedom is too small (e.g., carnivores: 0.85, 22 species). Also, there is no agreement on whether the slope for birds and mammals is closer to 3/4 or 2/3 (28, 31, 32). Many slopes reported by Peters (26) are significantly different from 3/4. Thus it seems that the universal 3/4 power for metabolic rate is a myth reinforced by each new slope researchers find differing from 0.75 but not significantly. A very large set of data, usually not at hand, is necessary to falsify the myth. It is therefore clear that any model explaining an interspecific allometry of metabolic rate should predict a range of values ≈3/4, not exactly the 3/4 value.

Our explanation of the 3/4 power law for metabolic rate is an alternative to the model by West et al. (25), which is based on several questionable assumptions. The most important one is that the standard metabolic rate depends on the structure of the supplying systems (e.g., the fractal structure of the circulatory system in vertebrates); it is more likely that the structure of the supplying system adjusts to meet the maximum metabolic demands (31, 33). Furthermore, close to 3/4 scaling of the metabolic rate has also been observed in organisms that lack a space-filling, self-similar fractal organization of internal supply systems, such as protists (26). Our model does not predict an exactly 3/4 exponent, but only an exponent in this range, as in the case of real data. Although in our model interspecific allometries are by-products of within-lineage allometries and body size optimization, as in the model by Kozlowski and Weiner (34), ours goes further: the parameters of intraspecific allometries for metabolic rate are not considered random variables but are deduced from evolutionary mechanisms common to all cellular organisms. Our explanation incorporates selection pressures acting simultaneously on all levels of biological organization, from genome and cell size to whole body size. The conclusion that within-lineage allometric slopes differ from those computed between-lineage clearly invalidates the universality of the 3/4 allometric exponent and its functional explanation put forward by West et al. (25). Instead, the links between DNA amount, nucleus size, cell metabolism, and whole body metabolism should be studied more carefully, and it must be rethought whether noncoding DNA is really “junk” and “parasitic.” We agree with Vinogradov (7) that a new field is emerging: ecophysiological cytogenetics. The field may be even broader and may include life history evolution.

Acknowledgments

We are indebted to T. R. Gregory for access to his database; M. Cichon, T. R. Gregory, R. Korona, P. Koteja, the late H. Szarski, R. E. Ricklefs, J. Taylor, M. Woyciechowski, and two anonymous reviewers for comments on an earlier version of the paper; and M. Jacobs for helping to edit it. This research was supported partly by Polish Ministry of Scientific Research and Information Technology Grant 3PO4F 026 24.

Appendix

Adult body mass (w) of a given lineage member can be approximated as

|

where n is the number of cells, and wc is the cell mass. Within-lineage scaling of standard metabolic rate (R) of the adults can therefore be expressed as R(w) = anwbc, where a is a normalization coefficient, and b is the allometric exponent scaling wc to R. When wc is constant and body size changes through cell number n, then

|

Substituting dn/dw = 1/wc and solving for R gives R(w) = γw, where  .

.

When n is constant and body size changes through wc, then  . Because wc = w/n, rearranging the terms and solving for R gives R(w) = βwb, where β = abn1–b.

. Because wc = w/n, rearranging the terms and solving for R gives R(w) = βwb, where β = abn1–b.

This paper was submitted directly (Track II) to the PNAS office.

Abbreviations: BMR, basal metabolic rate; C-value, genome size.

References

- 1.Cavalier-Smith, T. (1982) Annu. Rev. Biophys. Bioengin. 11, 273–302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gregory, T. R. (2001) Biol. Rev. 76, 65–101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kidwell, M. G. & Lisch, D. R. (2001) Evolution (Lawrence, Kans.) 55, 1–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pagel, M. & Johnstone, R. A. (1992) Proc. R. Soc. London Ser. B 249, 119–124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Szarski, H. (1970) Nature 226, 651–652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Vinogradov, A. E. (1995) Evolution (Lawrence, Kans.) 49, 1249–1259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Vinogradov, A. E. (1997) Evolution (Lawrence, Kans.) 51, 220–225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gregory, T. R. (2002) Evolution (Lawrence, Kans.) 56, 121–130. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Goniakowska, L. (1973) Acta Biol. Cracov. Ser. Zool. 16, 114–134. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sherman, F. (1991) in Guide to Yeast Genetics and Molecular Biology, eds. Guthrie C. & Fink, G. R. (Academic, San Diego), pp. 3–21.

- 11.Cavalier-Smith, T. (1985) in The Evolution of Genome Size, ed. Cavalier-Smith, T. (Wiley, Chichester, U.K.), pp. 69–103.

- 12.Commoner, B. (1964) Nature 202, 960–968. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bennett, M. D. (1971) Proc. R. Soc. London Ser. B 178, 277–299. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nurse, P. (1985) in The Evolution of Genome Size, ed. Cavalier-Smith, T. (Wiley, Chichester, U.K.), pp. 185–196.

- 15.Szarski, H. (1983) J. Theor. Biol. 105, 201–209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Porter, R. K. & Brand, M. D. (1993) Nature 362, 628–630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hulbert, A. J. & Else, P. L. (2000) Annu. Rev. Physiol. 62, 207–235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kozłowski, J. (1992) Trends Ecol. Evol. 7, 15–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Charnov, E. L. (1993) Life History Invariants: Some Explorations of Symmetry in Evolutionary Ecology (Oxford Univ. Press, Oxford).

- 20.Perrin, N. & Sibly, R. M. (1993) Annu. Rev. Ecol. Syst. 24, 379–410. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kozłowski, J. (1996) Am. Nat. 147, 101–114. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jockusch, E. L. (1997) Proc. R. Soc. London Ser. B 264, 597–604. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Roth, G., Nishikava, K. C. & Wake, D. B. (1997) Brain Behav. Evol. 50, 50–59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Morand, S. & Ricklefs, R. E. (2001) Trends Genet. 17, 567–568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.West, G. B., Brown, J. H. & Enquist, B. J. (1997) Nature 276, 122–126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Peters, R. H. (1983) The Ecological Implications of Body Size (Cambridge Univ. Press, Cambridge, U.K.).

- 27.Hayssen, V. & Lacy, R. C. (1985) Comp. Biochem. Physiol. 81, 741–754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bennett, P. M. & Harvey, P. H. (1987) J. Zool. 213, 327–363. [Google Scholar]

- 29.White, C. R. & Seymour R. S. (2003) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 100, 4046–4049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lovegrove, B. G. (2000) Am. Nat. 156, 201–219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Dawson, T. H. (2001) J. Exp. Biol. 204, 395–407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Dodds, P. S., Rothman, D. H. & Weitz, J. S. (2001) J. Theor. Biol. 209, 9–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Darveau, C.-A., Suarez, R. K., Andrews, R. D. & Hochachka, P. W. (2002) Nature 417, 166–170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kozłowski, J. & Weiner, J. (1997) Am. Nat. 149, 352–380. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Heusner, A. A. (1991) J. Nutr. 121, S8–S17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.McNab, B. K. (1989) in Carnivore Behavior, Ecology and Evolution, ed. Gittleman, J. L. (Univ. Press, Ithaca, NY), pp. 335–354.

- 37.McNab, B. K. & Armstrong, M. I. (2001) J. Mammal. 82, 709–720. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Poczopko, P. (1971) Acta Theriol. 16, 1–21. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Poczopko, P. (1979) Acta Theriol. 24, 125–136. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Welle, S. & Nair, K. S. (1990) Endocrinol. Metab. 1990, E990–E998. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lindenfors, P. & Tullberg, B. S. (1998) Biol. J. Linn. Soc. 64, 413–447. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Nowak, R. M. (1995) Mammals of the World (The Johns Hopkins Univ. Press, Baltimore).

- 43.Purvis, A. & Harvey, P. H. (1995) J. Zool. 237, 259–283. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Symonds, M. R. E. (1999) J. Zool. 249, 315–337. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kendeigh, S. C., Dol'nik, V. R. & Gavrilov, V. M. (1977) in Granivorous Birds in Ecosystems, eds. Pinowski, J. & Kendeigh, S. C. (Cambridge Univ. Press, Cambridge, U.K.), pp. 127–204.

- 46.Thouzeau, C., Duchamp, C. & Handrich, Y. (1999) Physiol. Biochem. Zool. 72, 170–178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Tieleman, B. I. & Williams, J. B. (2000) Physiol. Biochem. Zool. 73, 461–479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Brough, T. (1983) Average Weights of Birds (Ministry of Agriculture, Fisheries and Food, Agricultural Science Service, Aviation Bird Unit, Worplesdon Laboratory, Guilford, U.K.).