SUMMARY

Pseudomonas syringae infects a wide range of plant species through the use of a type III secretion system. The effector proteins injected into the plant cell through this molecular syringe serve as promoters of disease by subverting the plant immune response to the benefit of the bacteria in the intercellular space. The targets and activities of a subset of effectors have been elucidated recently. In this article, we focus on the experimental approaches that have proved most successful in probing the molecular basis of effectors, ranging from loss‐of‐function to gain‐of‐function analyses utilizing several techniques for effector delivery into plants. In particular, we highlight how these diverse approaches have been applied to the study of one effector—AvrPtoB—a multifunctional protein with the ability to suppress both effector‐triggered immunity and pathogen (or microbe)‐associated molecular pattern‐triggered immunity. Taken together, advances in this field illustrate the need for multiple experimental approaches when elucidating the function of a single effector.

PSEUDOMONAS SYRINGAE, A MODEL PATHOGEN

The plant pathogenic bacterium, Pseudomonas syringae, has emerged as a pre‐eminent model system for the study of molecular plant–microbe interactions (Preston, 2000). Pseudomonas syringae encompasses nearly 50 pathovars that infect both monocotyledonous and dicotyledonous plant species. The pathogen utilizes a type III secretion system (T3SS) as its main virulence strategy to inject a suite of proteins, termed effectors, into host cells, where they are typically individually dispensable but collectively required for disease (Cunnac et al., 2009). Although the proposed functions of effectors include the promotion of nutrient release into the apoplast and suppression of plant immune responses, only the latter has been demonstrated experimentally (Alfano and Collmer, 1996; Mudgett, 2005). Therefore, it is generally accepted that effectors function mainly to subvert plant immunity, which permits bacterial multiplication in the leaf apoplast, leading to the onset of disease symptoms and, eventually, transmission of the pathogen to other hosts.

At present, the genome sequences of four P. syringae strains from three pathovars have been published (Almeida et al., 2009; Buell et al., 2003; Feil et al., 2005; Joardar et al., 2005). The first sequenced genome was that of P. syringae pv. tomato strain DC3000 (DC3000) (Buell et al., 2003), which causes bacterial speck disease on tomato and is able to infect the model plants Arabidopsis thaliana (Whalen et al., 1991) and, when lacking the hopQ1‐1 gene, Nicotiana benthamiana (Wei et al., 2007). Each of these three host plants boasts unique advantages for studying the molecular aspects of susceptibility and immunity. Tomato shares an evolutionary history with the pathogen, whereas Arabidopsis features the availability of catalogued T‐DNA insertion mutants and well‐characterized ethyl methanesulfonate (EMS) mutants (Glazebrook et al., 1997). Nicotiana benthamiana is particularly amenable to virus‐induced gene silencing, and its large leaves lend themselves to robust assays using Agrobacterium tumefaciens‐mediated transient expression (Goodin et al., 2008).

A BRIEF HISTORY: FUNCTIONAL STUDIES OF EFFECTORS AND THE PLANT IMMUNE RESPONSE

To describe efforts to elucidate effector function, it is necessary to first consider how plants defend themselves against pathogen infection, as the two are evolutionarily intertwined. Plants utilize a bipartite, localized, inducible innate immune system. The first layer consists of a basal response, triggered by the perception of nonself or, more specifically, pathogen (or microbe)‐associated molecular patterns (PAMPs) that are common to entire classes of microbes by pattern recognition receptors (PRRs). This type of immunity is designated PAMP‐triggered immunity (PTI) (Chisholm et al., 2006). PTI is associated with increased production of antimicrobial compounds, including reactive oxygen species (ROS), and the fortification of plant cell walls by increased callose production (Gómez‐Gómez et al., 1999). The second, more robust level of immunity is triggered by the virulence activities of effector proteins, and is accordingly called effector‐triggered immunity (ETI) (Chisholm et al., 2006). A hallmark of ETI, although apparently not required in some cases (Yu et al., 1998), is the occurrence of a type of programmed cell death called the hypersensitive response (HR). Effector targeting of host components of both PTI and ETI suppresses plant immunity, and is referred to as effector‐triggered susceptibility (ETS) (Jones and Dangl, 2006). How effectors suppress host immunity to cause disease is currently the central question of effector functional analyses.

Three models for ETI, each based on the previous one, led to distinct phases of effector functional analyses. Early success came from the ability of a subset of effectors, also called ‘avirulence’ or ‘avr’ proteins, to confer avirulence to the expressing pathogen on a host expressing a corresponding resistance (R) protein. This gain‐of‐function phenotype provided the basis for the gene‐for‐gene model where, for every plant resistance (R) gene, there was postulated to exist a corresponding pathogen avr gene which, when detected, led to complete immunity (Flor, 1956). At the time, the simplest prediction from this model was that R proteins acted as receptors by physically interacting with avirulence protein elicitors, thereby activating immunity. This prediction held true for the molecular analysis of the first cloned R‐Avr pair, the Pto kinase and AvrPto (Martin et al., 1993; Ronald et al., 1992; Scofield et al., 1996; Tang et al., 1996). However, a lack of evidence for the direct interaction of other R‐Avr pairs indicated that a direct interaction was the exception. Instead, most R proteins belong to the nucleotide‐binding leucine‐rich repeat (NB‐LRR) family of proteins that also function in pathogen recognition in animals (for a review, see (Deyoung and Innes, 2006). In fact, elicitation of immunity by Pto recognition of AvrPto requires the tomato NB‐LRR protein Prf (1994, 1996). Unexpectedly, completion of the Arabidopsis genome sequence revealed the existence of approximately 150 NB‐LRR genes (Initiative, 2000), a number unlikely to be adequate for a ‘gene‐for‐gene’ system to defend the plant against numerous pathogens.

Both the unexplained requirement for Prf in Pto‐mediated resistance and the relatively small number of NB‐LRR genes present in Arabidopsis led to the development of the guard model of plant immunity (van der Biezen and Jones, 1998; Dangl and Jones, 2001). In order for the plant to maximize the recognition capabilities of a limited number of NB‐LRR proteins, these proteins were viewed as serving to guard common effector targets or ‘guardees’ in the host cell. On effector manipulation of the ‘guardee,’ the NB‐LRR protein signals an immune response. The guard model provided an explanation for how a single R protein could recognize multiple sequence‐unrelated effectors (Bisgrove et al., 1994; Grant et al., 1995; Kim et al., 2002), and proposed a relationship between the avirulence and virulence activities of effectors (van der Biezen and Jones, 1998; Dangl and Jones, 2001). This ushered in the second phase of effector functional studies, defining effector virulence activities.

The most recent model of plant immunity, termed the decoy model, arose from many observations that, in the absence of a specific R protein, there is little or no evidence that the guardee contributes to the virulence activity of the corresponding effector (Belkhadir et al., 2004; Chang et al., 2000; Lim and Kunkel, 2004a; Lin and Martin, 2005). In addition, mutations affecting avirulence and virulence can be uncoupled (Shan et al., 2000). These observations indicated that R proteins may not be guarding effector targets, but rather are guarding proteins that mimic effector targets. In this way, these host mimics act as ‘decoys’ by intercepting the effector before it can manipulate its intended host target (van der Hoorn and Kamoun, 2008; Xing et al., 2007). Therefore, proteins closely related to the decoy have recently been sought after as the most promising candidates for effector targets.

This article concentrates on recent techniques for investigating the function of P. syringae effector proteins, and is organized by the type of analysis and the method of effector delivery into the host. We focus on the widely studied effector AvrPtoB, also known as HopAB2, as a case study to demonstrate the necessity of multiple assays to reveal the function of a single effector. A summary of the multiple activities of AvrPtoB in plants is provided in Fig. 1. Where the use of a technique is not exemplified by the analysis of AvrPtoB, we provide examples from the study of other effectors. There is a secondary focus on the sequence‐unrelated effector, AvrPto, as it shares many of the same activities in suppressing PTI with AvrPtoB. We recognize the significant advances made in the functional analyses of other P. syringae effector proteins, and have included Table 1 as a summary of the literature that led to these discoveries. It is important to note, however, that we have included only those effectors whose functions have been confirmed using multiple methods. For comprehensive reviews of the entire P. syringae effector repertoire and the basis of its host specificity, the reader is referred to Cunnac et al. (2009) and Lindeberg and Collmer (this issue), respectively.

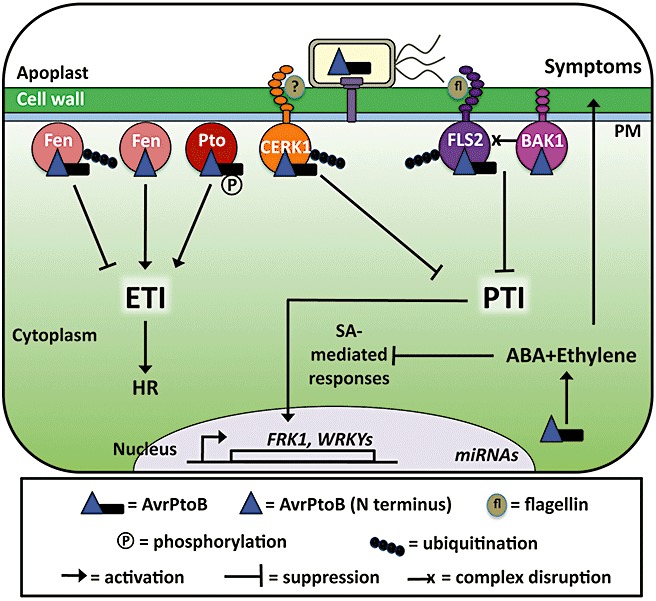

Figure 1.

The diverse activities of AvrPtoB. AvrPtoB is delivered into the plant cell by the type III secretion system (T3SS) of Pseudomonas syringae. In tomato, full‐length AvrPtoB is recognized by Pto, whereas the N‐terminal region of AvrPtoB is recognized by Fen. Both Pto and Fen kinases signal effector‐triggered immunity (ETI) through the nucleotide‐binding leucine‐rich repeat (NB‐LRR) protein, Prf (not shown). Full‐length AvrPtoB ubiquitinates Fen, leading to its degradation and the suppression of ETI. One explanation for the ability of Pto to avoid ubiquitination and degradation by AvrPtoB is that it may inhibit ubiquitination by phosphorylating AvrPtoB near the E3 ubiquitin ligase domain. In the absence of AvrPtoB, CERK1/Bti9 and FLS2 trigger pathogen (or microbe)‐associated molecular pattern‐triggered immunity (PTI) in response to PAMPs (flagellin in the case of FLS2 and an unknown PAMP for CERK1/Bti9). AvrPtoB suppresses CERK1/Bti9‐ and FLS2‐mediated PTI, reportedly by promoting their degradation in Arabidopsis. In addition, the N‐terminal region of AvrPtoB is sufficient for interacting with the co‐receptor BAK1 and disrupting the PAMP‐induced FLS2–BAK1 complex. The N‐terminal region of AvrPtoB is also able to suppress mitogen‐activated protein (MAP) kinase activation, transcription of PAMP‐induced genes and microRNA (miRNA) production, most probably as a result of targeting pattern recognition receptors (PRRs). AvrPtoB expression is associated with increased production of the phytohormones abscisic acid (ABA) and ethylene. Both hormones antagonize the salicylic acid (SA)‐mediated immune response and ethylene is known to be important for symptom formation. HR, hypersensitive response; PM, plasma membrane.

Table 1.

Summary of additional Pseudomonas syringae effector functional analyses for virulence activity.

| Effector | Pathovar/strain | Host process(es) targeted | Mechanism of action | Host target(s) or decoys (in bold) | Methods utilized* | References† |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AvrB | glycinea/race 0 | PTI | Promotes phosphorylation | RIN4, RAR1 | GoF, T3D, AMT, Y2H, TP, SA, MP, CoIP, IVvE | 1–6 |

| AvrE | tomato/DC3000 | PTI, symptom formation | Unknown | Unknown | LoF, SM, PM, C, GoF, AMT | 7,8 |

| AvrPto | tomato/JL1065, DC3000 | PTI, PRR signalling, ethylene production, miRNA processing | Kinase inhibition, PRR complex disruption | Pto, FLS2, BAK1, EFR | LoF, SM, PM, GoF, T3D, AMT, TP, PT, MP, SP, SA, IVtE, IVvE, IVPD, CoIP, BiFC, SPR, Y2H | 9–22 |

| AvrRpm1 | maculicola/M2 | PTI | Promotes phosphorylation | RIN4 | LoF, SM, CoIP, IVvE, TP | 23–25 |

| AvrRps4 | pisi1/151 | PTI | Unknown | Unknown | GoF, T3D, TP | 26 |

| AvrRpt2 | tomato/JL1065 | ETI, PTI, auxin production | Cysteine protease | RIN4 | GoF, T3D, TP, IVvE, AMT, H, MP, HE, IVPD, IVtE, PT | 23,25,27–38 |

| AvrPphB | phaseolicola/ races 3 and 4 | Unknown | Cysteine protease | PBS1 | GoF, AMT, H, IVtE, MP, CoIP, HE, SA, IVvE | 39–42 |

| HopAI1 | tomato/0288‐9 | PTI, MAP kinase signalling | Phosphothreonine lyase | MPK3/MPK6 | LoF, SM, GoF, TP, PT, IVPD, CoIP, IVtE | 43,44 |

| HopAM1 | tomato/DC3000 | PTI, ABA response, salt stress response | Unknown | Unknown | GoF, T3D, TP | 45 |

| HopAO1 | tomato/DC3000 | Avirulence‐associated cell death | Protein tyrosine phosphatase | Unknown | LoF, SM, C, GoF, T3D, AMT, TP, H, IVtE | 46–48 |

| HopI1 | tomato/DC3000 | SA accumulation | J domain activity | Unknown | LoF, SM, C, H, TP, AMT, HE, MP | 49 |

| HopM1 | tomato/DC3000 | PTI, symptom formation | Promotes degradation of host proteins, mechanism unknown | MIN7 | LoF, SM, PM, C, GoF, TP, Y2H, CoIP, AMT, MP | 50–52 |

| HopN1 | tomato/DC3000 | Virulence‐ and avirulence‐associated cell death | Cysteine protease | Unknown | LoF, SM, GoF, T3D, H, IVtE | 41,53 |

| HopU1 | tomato/DC3000 | Avirulence‐associated cell death, PTI | ADP‐ribosyltransferase | GRP7 | LoF, SM, C, H, GoF, AMT, TP, IVtE, IVvE, MP | 54 |

| HopZ2 | pisi/895A | Unknown | Cysteine protease | Unknown | H, IVtE, GoF, T3D, AMT | 55,56 |

AMT, Agrobacterium‐mediated transformation; BiFC, bimolecular fluorescent complementation; C, complementation; CoIP, co‐immunoprecipitation; CT, candidate target; GoF, gain of function; H, homology; HE, heterologous expression; IVPD, in vitro pull‐down; IVtE, in vitro enzymatic activity assay; IVvE, in vivo enzymatic activity assay; LoF, loss of function; MP, mutant plants; PM, polymutant; PT, protoplast transformation; RI, RNA interference; SA, structural analysis; SM, single mutant; SP, silenced plants; SPR, surface plasmon resonance; T3D, type III secretion system delivery; TP, transgenic plants; Y2H, yeast two hybrid.

1, Ashfield et al. (1995); 2, Desveaux et al. (2007); 3, Lee et al. (2004); 4, Mackey et al. (2002); 5, Ong and Innes (2006); 6, Shang et al. (2006); 7, Badel et al. (2006); 8, Debroy et al. (2004); 9, Anderson et al. (2006); 10, Bogdanove and Martin (2000); 11, Chang et al. (2000); 12, Cohn and Martin (2005); 13, Hann and Rathjen (2007); 14, Hauck et al. (2003); 15, He et al. (2006); 16, Lin and Martin (2005); 17, Navarro et al. (2008); 18, Shan et al. (2008); 19, Shan et al. (2000); 20, Wulf et al. (2004); 21, Xiang et al. (2007); 22, Xing et al. (2007); 23, Kim et al. (2005b); 24, Mackey et al. (2002); 25, Ritter and Dangl (1995); 26, Sohn et al. (2009); 27, Axtell et al. (2003); 28, Axtell and Staskawicz (2003); 29, Chen et al. (2007); 30, Chen et al. (2004); 31, Chen et al. (2000); 32, Chisholm et al. (2005); 33, Coaker et al. (2005); 34, Guttman and Greenberg (2001); 35, Kim et al. (2005a); 36, Lim and Kunkel (2004a); 37, Lim and Kunkel (2004b); 38, Mackey et al. (2003); 39, Ade et al. (2007); 40, Shao et al. (2003); 41, Shao et al. (2002); 42, Zhu et al. (2004); 43, Li et al. (2005); 44, Zhang et al. (2007); 45, Goel et al. (2008); 46, Bretz et al. (2003); 47, Espinosa et al. (2003); 48, Underwood et al. (2007); 49, Jelenska et al. (2007); 50, Badel et al. (2003); 51, Badel et al. (2006); 52, Nomura et al. (2006); 53, Lopez‐Solanilla et al. (2004); 54, Fu et al. (2007); 55, Lewis et al. (2008); 56, Ma et al. (2006).

IDENTIFICATION OF A VIRULENCE PHENOTYPE: LOSS‐OF‐FUNCTION ANALYSIS

The requirement of the T3SS for pathogenicity in the absence of host R proteins clearly indicates that the activity of effectors extends beyond betrayal of the pathogen to the plant surveillance system. The most common first step in assigning importance to a particular effector is to identify a loss‐of‐function phenotype by creating a deletion mutation in the parent strain and testing for alterations in virulence. Indeed, of the nearly 30 effectors delivered into plant cells by DC3000 (Chang et al., 2005; Lindeberg et al., 2006; Schechter et al., 2006), several have been shown to be involved in symptom formation (2003, 2006; Lopez‐Solanilla et al., 2004) or bacterial growth in planta (Bretz et al., 2003; Espinosa et al., 2003; Fu et al., 2007; Guo et al., 2005) in the absence of host R proteins using a loss‐of‐function approach. However, in most cases, the deletion of single effectors does not cause a detectable decrease in virulence using current methods, presumably because of redundancy. The challenges brought about by effector redundancy have driven the generation of many alternative assays for effector function.

Past research has demonstrated that, in some cases, the lack of a virulence phenotype from the mutation of a single effector can be addressed by the deletion of two or more effectors. The application of such polymutants to overcome the challenges of redundancy has been illustrated recently in two reports (Kvitko et al., 2009; Wei et al., 2007). Loss‐of‐function analyses of AvrPtoB have benefited to a great extent from the use of a polymutant strategy. Indeed, the identification of AvrPtoB was initiated from the observation that the deletion of avrPto from P. syringae pv. tomato does not alleviate the avirulence phenotype in Pto‐expressing tomatoes (Ronald et al., 1992). Therefore, it was hypothesized that Pto recognizes a second effector present in the pathogen and that a double mutation is required to observe the loss of avirulence. In a cross‐kingdom yeast two‐hybrid analysis, AvrPtoB, another P. syringae protein, was confirmed to interact with tomato Pto (Kim et al., 2002). As expected, DC3000 lacking expression of both AvrPto and AvrPtoB results in virulence on tomato lines expressing Pto, and complementation with AvrPtoB restores avirulence. The double mutant was also useful in identifying virulence activity attributable to AvrPtoB (Lin and Martin, 2005). The mutant displays diminished bacterial growth and symptom formation on susceptible tomato plants. Complementation with AvrPtoB, but not the vector control, partially restores bacterial growth of the mutant. Further complementation analyses of the same avrPto/avrPtoB mutant demonstrated that all tested members of the HopAB family retain virulence and avirulence activity in tomato, including the C‐terminally truncated homologue, HopPmaL (Lin et al., 2006). In addition, complementation analysis was used to determine the minimal region required and specific amino acids important for both avirulence and virulence activities of AvrPtoB (Xiao et al., 2007b). The N‐terminal 307 amino acids of AvrPtoB are sufficient for both avirulence and virulence activity, and mutations disrupting the avirulence activity of this truncated protein also affect the virulence activity (2007a, 2007b).

A similar technique for demonstrating both avirulence and virulence activity was utilized for VirPphA, another member of the HopAB family of P. syringae effectors found in P. syringae pv. phaseolicola strains (Lindeberg et al., 2005). The virPphA gene is located on a plasmid, together with several other effectors, in strain 1449B. On curing the plasmid, Jackson et al. (1999) observed that the strain gained virulence on previously resistant cultivars, demonstrating a role for at least one plasmid‐borne effector in conferring avirulence. Surprisingly, the same strain was avirulent on previously susceptible cultivars of bean, pointing to a function for a plasmid‐borne effector in the suppression of ETI. The molecular basis of ETI suppression has since been elucidated in tomato (2006, 2003; Janjusevic et al., 2006; Ntoukakis et al., 2009; Rosebrock et al., 2007). Through a series of complementation experiments, coupled with insertional mutagenesis, VirPphA was confirmed to contribute to both loss‐of‐function phenotypes (Jackson et al., 1999).

GAIN‐OF‐FUNCTION ASSAYS: EFFECTOR DELIVERY VIA T3SS

Although the polymutant approach has been successful, there are known cases in which deletion of entire effector clusters results in no measurable phenotype in a particular host (Kvitko et al., 2009; Wei et al., 2007). Therefore, to address the roles of these effectors, many gain‐of‐function assays have been developed over the last ∼10 years. These assays differ primarily in the method of effector delivery or expression in the host, which provides the majority of the constraints on any particular assay.

The method of effector delivery that most closely mimics a natural infection is through a T3SS of a closely related pathogen. This method utilizes a pathogen from which the effector of interest is normally absent and has been employed as an alternative to early loss‐of‐function assays. The surrogate pathogen is modified to deliver the effector of interest and is tested for alterations to virulence or avirulence. This approach has been particularly effective in early studies of AvrPto using the P. syringae pv. tomato strain T1, which lacks avrPto and expression of AvrPtoB (Chang et al., 2000; Lin et al., 2006; Shan et al., 2000).

Similarly, delivery of effectors by type I nonhost pathogens (those not causing an HR; Mysore and Ryu, 2004) can be used to identify effectors that suppress PTI by testing for increased bacterial growth of the formerly repressed pathogen. The plasmid‐cured P. syringae pv. phaseolicola strain described above typically exhibits a limited increase in bacterial growth and no visual symptoms when infiltrated into the leaves of Arabidopsis (Soylu et al., 2005); yet, the expression of AvrPtoB in this strain enhances both phenotypes (de Torres et al., 2006). Interestingly, the expression of AvrPtoB truncations that can no longer suppress ETI in bean still enhances symptom formation in Arabidopsis, suggesting that the suppression of ETI and PTI by AvrPtoB is separable. Although the delivery of an effector by a surrogate pathogen mimics the natural method of delivery, it often does not address the issue of effector redundancy. Therefore, false negatives may occur as a result of redundant activities of endogenous, unknown effectors.

The delivery of effectors from the nonpathogen P. fluorescens carrying the T3SS from P. syringae pv. syringae strain 61 has been particularly effective as a single effector delivery system for gain‐of‐function assays for both ETI and PTI suppression (Jamir et al., 2004; Oh and Collmer, 2005). The ability of AvrPtoB, among other DC3000 effectors, to suppress ETI was confirmed by a lack of HR elicitation following expression of the effector in P. fluorescens carrying a T3SS and hopA1, an effector that is recognized in tobacco by an unknown R protein (Jamir et al., 2004). A similar P. fluorescens T3SS delivery system lacking hopA1 and, consequently, recognition by tobacco, was used to deliver effectors to test for PTI suppression in N. benthamiana (Oh and Collmer, 2005). This assay takes advantage of the observation that PTI induction is associated with localized resistance to subsequent HR‐ or disease‐associated cell death in plants (Klement et al., 1999; Lovrekovich and Farkas, 1965; Oh and Collmer, 2005). Therefore, effectors that suppress PTI allow the HR to ensue in the infiltrated area. Although the authors did not test AvrPtoB, our own results have shown that C‐terminal truncations of AvrPtoB suppress PTI in this assay (K. Munkvold and G. Martin, unpublished results).

Although delivery of an effector by a T3SS is the most natural delivery method employed for gain‐of‐function effector studies, there are some disadvantages to its use. Effectors are probably delivered by the T3SS in very small quantities into the host cell. Therefore, subtle activities expected for some effectors are unlikely to be detected using this delivery system. Furthermore, it is possible that some effectors may require the activity of another effector(s) for full activation. In addition, the activity of an effector cannot be studied in the absence of PAMPs present in the delivering bacterium, making the study of individual PTI elicitors impossible.

GAIN‐OF‐FUNCTION ASSAYS: EFFECTOR EXPRESSION VIA AGROBACTERIUM

The expression of effectors directly in plant cells overcomes the issue of low effector abundance faced by T3SS delivery methods. A. tumefaciens‐mediated transient expression of effector proteins is the most commonly utilized plant transformation method. Coupled with expression from the cauliflower mosaic virus (CaMV) 35S promoter, this method leads to high levels of protein production (Abramovitch et al., 2003). The popularity of Agrobacterium‐mediated transformation stems from the ability to express several constructs in a single leaf in the case of the broad‐leaved model plant N. benthamiana. The transient nature of the transformation event also avoids the time‐consuming process of creating stable transformants. As a result, the assay can be completed in as little as 1–2 days.

The first gain‐of‐function assays utilizing Agrobacterium‐mediated transformation were often cell death based. In the case of bacterial pathogens, effector activity within the host cell is a prerequisite for the elicitation of ETI and the subsequent HR. Therefore, Agrobacterium‐mediated transient transformation of plant leaves could be used as an assay for avirulence activity in resistant plants (Tang et al., 1996). Recognition of AvrPtoB by the tomato R protein Pto was first demonstrated by transiently transforming tomato plants with or without a functional copy of Pto (Kim et al., 2002). Expression of AvrPtoB causes cell death exclusively in the presence of functional Pto.

A surprising yet fortuitous observation was made whilst testing for Pto recognition of AvrPtoB in N. benthamiana. In this plant, no cell death occurs following the co‐expression of the R/Avr pair, leading to the hypothesis that AvrPtoB blocks downstream signalling events necessary for HR (Abramovitch et al., 2003). To test this hypothesis, the ability of AvrPtoB to prevent cell death by known cell death elicitors was examined. Co‐expression of AvrPtoB with Pto and AvrPto, Avr9 and Cf9 (an Avr/R pair originating from a fungal–tomato interaction) and the mouse programmed cell death inducer Bax abolishes cell death. This result is consistent with the previous finding that the related effector VirPphA suppresses ETI elicited by another effector in P. syringae pv. phaseolica (Jackson et al., 1999).

Not only does AvrPtoB suppress HR elicited by other effectors, it also suppresses HR elicitation caused by its own recognition by an unknown N. benthamiana‐derived R protein (Abramovitch et al., 2003). A truncation of the C‐terminal region of AvrPtoB, removing approximately 30% of the protein (leaving amino acids 1–387), results in cell death when transiently expressed in N. benthamiana, whereas expression of full‐length AvrPtoB does not. Furthermore, a loss‐of‐function assay for avirulence by a DC3000 mutant strain lacking the C‐terminal 44 amino acids of AvrPtoB in tomato demonstrated that the recognition normally suppressed by full‐length AvrPtoB (Rsb) is also present in tomato. Rsb‐mediated resistance is dependent on the NB‐LRR protein Prf, and is not caused by Pto. These studies illustrate the power of combining gain‐of‐function and loss‐of‐function analyses in revealing effector function.

Recently, Agrobacterium‐mediated transient expression has been used for a number of noncell death‐based assays in N. benthamiana. A recent methods paper describes several assays for effector‐mediated alteration of PAMP perception and the subsequent induction of PTI (Hann and Rathjen, 2007). The readouts range from early signalling events following PAMP perception, such as mitogen‐activated protein (MAP) kinase activation and rapid calcium burst, to ROS production, all elicited by P. syringae pv. tabaci flagellin. In all three assays, AvrPtoB suppresses the flagellin‐induced response, demonstrating its ability to suppress multiple PTI readouts.

One of the caveats of Agrobacterium‐mediated transformation is that there are likely to be multiple PAMPs originating from the Agrobacterium strain that are recognized by the plant. The presence of these PAMPs may complicate the results of assays measuring effector suppression of PTI. Nevertheless, Agrobacterium‐mediated expression of AvrPtoB enhances the multiplication of the transforming bacteria in the apoplast, demonstrating that AvrPtoB can also suppress PTI elicited by Agrobacterium‐derived PAMPs (Hann and Rathjen, 2007).

A second disadvantage is that assays involving pathogen challenge subsequent to effector expression cannot be accomplished in the system, because of the inhibition of disease‐associated cell death and, presumably, bacterial multiplication in the apoplast by prior elicitation of PTI (Oh and Collmer, 2005). As with all assays involving the overexpression of an effector, conclusions from these experiments must be drawn with some caution and should also be examined by an assay utilizing natural delivery by the T3SS.

Although Agrobacterium‐mediated transient expression works well in solanaceous plants, a final limitation of this expression system is the low expression levels typically attained in Arabidopsis. This difficulty can be overcome partially with a mutant Arabidopsis line lacking the EF‐Tu receptor, EFR, whose activation restricts Agrobacterium‐mediated transformation (Zipfel et al., 2006). EF‐Tu is one of the most abundant bacterial proteins and is targeted as a PAMP in plants. In particular, the Agrobacterium EF‐Tu is a very potent elicitor of PTI in Arabidopsis. Although the efr mutant plant may be useful for studies of ETI in Arabidopsis, the loss of EFR may compromise PTI and associated analyses of this effector‐targeted type of immunity.

GAIN‐OF‐FUNCTION ASSAYS: EFFECTOR EXPRESSION IN PROTOPLASTS

Another useful method of plant transformation that has grown in popularity for effector functional analysis is mesophyll protoplast transformation. The entire process, protoplast generation from leaf tissue, transformation and protein expression, can be completed in 1–3 days, depending on the plant species and the length of time allotted for protein expression. Although protoplasts lack fully developed cell walls, their responses to most elicitors mimic those found in intact leaves (Sheen, 2001; Yoo et al., 2007). Therefore, hormone or PAMP elicitors can be added directly to the incubation medium and the protoplasts monitored for downstream signalling events.

The main advantage of protoplast transformation over Agrobacterium‐mediated transformation is the ability to transform plant cells in the absence of bacteria and their associated PAMPs. As a result, signalling by individual PAMPs in protoplasts can be tested. PAMP perception leads to changes in gene expression that can be assayed with a luciferase reporter system in protoplasts. Several early response genes, including FRK1, an LRR receptor‐like kinase (RLK), and WRKY29, a transcription factor, are induced within 30 min of treatment of Arabidopsis protoplasts with flg22, an active 22‐amino‐acid peptide from a conserved region of flagellin (Asai et al., 2002). NHO1 is induced within 3 h of induction with flg22 (Li et al., 2005). Each of these responses can be suppressed by the expression of individual DC3000 effectors. AvrPtoB has been shown to suppress the induction of FRK1 and other PAMP‐induced genes, but has not been tested for NHO1 suppression (He et al., 2006; Li et al., 2005; Xiao et al., 2007b). Some effectors are known to cause cell death when overexpressed or delivered in large amounts in plants, even in the absence of a typical ETI response when expressed by the pathogen (Wei et al., 2007). Consequently, it is important to show relative expression of a reporter compared with that of a housekeeping gene. In the case of FRK1, expression was compared with that of a ubiquitin–β‐glucuronidase (GUS) reporter to show that overall transcription is not diminished as a result of lethality caused by the expressed protein (He et al., 2006).

The activation of MAP kinase cascades is another early response to PAMP perception in plants (Asai et al., 2002). To test whether DC3000 effectors target this process, He et al. (2006) treated protoplasts expressing AtMPK3 or AtMPK6 with flg22 and assayed for the ability of the MAP kinases to phosphorylate the artificial substrate, myelin basic protein. In this assay, AvrPtoB and AvrPto, but not several other effectors tested, suppressed activation of the MAP kinases, indicating once more that these effectors act very early in the suppression of PTI. In fact, suppression was not restricted to flg22‐mediated PTI, as both effectors suppressed MAP kinase activation by NPP and HrpZ, two other known PTI elicitors. Furthermore, epistasis analysis involving overexpression of the constitutively active MAP kinase kinase (MAPKK) and MAP kinase kinase kinase (MAPKKK) placed the activity of the effectors upstream of MAPKKK. A later study using the same assay narrowed the required region for flg22‐induced MAP kinase suppression to the N‐terminal 387 amino acids of AvrPtoB (Xiao et al., 2007b). These data suggest that the C‐terminal ETI suppression domain of AvrPtoB is unnecessary for PTI suppression in Arabidopsis protoplasts. However, it is important to note that, in each of these assays, the effector is overexpressed and may be acting differently than during a natural infection.

Transient expression of effectors in protoplasts serves as a fast, microbe‐free transformation technique for in planta assays. Nevertheless, this method of transformation suffers from drawbacks when compared with other modes of transformation. Foremost, it is important to note that wound response signalling is often activated during protoplast generation and may cross‐talk with immune signalling. Although protoplasts appear to preserve the signal transduction networks of the intact leaves from which they were derived, cell wall‐based defences that serve an important role in PTI cannot be generated. In addition, assays to detect increases in bacterial virulence following effector expression cannot be performed in this system because of the physical nature of protoplast incubation in a liquid medium. Therefore, assays performed with this method of expression are molecular or biochemical in nature and do not fully reflect the biological interactions between a pathogen and its host.

GAIN‐OF‐FUNCTION ASSAYS: EFFECTOR EXPRESSION IN STABLE TRANSGENIC PLANTS

A final method of effector expression in plants can be achieved by generating stably transformed plants. The constitutive CaMV 35S promoter or dexamethasone‐ or oestradiol‐inducible systems are most often used to drive effector expression in these plants. The start‐up time invested in generating stable transformants greatly exceeds that of any transient transformation method. However, once in hand, these plants facilitate many gain‐of‐function assays and provide the only method of expression suitable for pathogen challenge assays.

In planta effector expression, followed by inoculation with wild‐type or mutant pathogens, is a powerful assay for assessing the virulence activity of an effector. Enhanced growth of a T3SS‐deficient pathogen as a result of effector expression in the plant suggests that the effector is able to suppress the cellular immune response, allowing for multiplication of the bacteria in the apoplast. This exact result has been observed for the expression of several DC3000 effectors, including AvrPtoB in transgenic Arabidopsis (Fu et al., 2007; Goel et al., 2008; Hauck et al., 2003; He et al., 2006; Jelenska et al., 2007; Li et al., 2005; Nomura et al., 2006; de Torres et al., 2006; Underwood et al., 2007). In most cases, induction of effector expression alone leads to a physiological change in the plant, including wilting, chlorosis or even necrosis. Therefore, high levels of effector expression clearly disturb the physiology of the plant and, as with other gain‐of‐function assays, it is best to validate this type of data with a parallel loss‐of‐function assay.

Pathogen interference with normal hormone signalling during P. syringae infection is important for disease progression (recently reviewed by López et al., 2008). Two microarray studies identified ethylene and abscisic acid (ABA) biosynthetic and responsive genes induced specifically by DC3000 carrying a functional T3SS. This suggests that effectors directly or indirectly function to increase the production of these hormones (Cohn and Martin, 2005; de Torres‐Zabala et al., 2007). Both AvrPto and AvrPtoB were found to contribute to the up‐regulation of ethylene signalling during the infection process based on two loss‐of‐function assays (Cohn and Martin, 2005). First, a mutant strain of P. syringae lacking both effectors was unable to induce the transcription of the ethylene‐associated genes or promote the production of ethylene during disease. Furthermore, inoculation of a tomato line deficient in ethylene production demonstrated that ethylene is required for enhanced virulence associated with the presence of AvrPto and AvrPtoB. Ethylene is known to play a role in P. syringae symptom formation (Bent et al., 1992; Lund et al., 1998), supporting the result that AvrPto and AvrPtoB target this pathway to benefit the pathogen. In the second study, de Torres‐Zabala et al. (2007) utilized transgenic Arabidopsis plants expressing AvrPtoB under the control of an inducible promoter to show that AvrPtoB expression results in an increase in transcription of NCED3, an ABA biosynthetic gene, as well as ABA production.

The use of transgenic plants expressing the effectors AvrPto or AvrRpt2 led to surprising and valuable observations regarding hormone alteration by effectors. Intriguingly, AvrPto‐ and AvrRpt2‐expressing plants display phenotypes reminiscent of those altered in brassinosteroid and auxin perception, respectively (Chen et al., 2007; Shan et al., 2008). AvrPto was subsequently shown to target the RLK, BAK1, in Arabidopsis, leading to a brassinosteroid insensitive‐like phenotype (Shan et al., 2008). AvrRpt2 was shown to enhance auxin production and sensitivity when expressed in Arabidopsis. AvrRpt2 also enhances auxin production caused by P. syringae infection when delivered by the pathogen (Chen et al., 2007).

Effector expression in transgenic plants facilitates unique assays compared with the other approaches of in planta effector expression described above. Other than possible artefacts caused by overexpression, fewer disadvantages are associated with this technique for in planta expression, making it a valuable method for gain‐of‐function assays in plants.

GAIN‐OF‐FUNCTION ASSAYS: EFFECTOR EXPRESSION IN YEAST

Information can also be gained from the expression of effectors in a heterologous system, such as the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Interestingly, the cell death‐inducing and cell death‐suppressing activities of some effectors are conserved across kingdoms and function similarly in yeast (Abramovitch et al., 2003; Jamir et al., 2004; Munkvold et al., 2008). AvrPtoB suppresses programmed cell death elicited by several inducers in yeast, suggesting that AvrPtoB targets a broadly conserved eukaryotic process for its general cell death suppression activity (Abramovitch et al., 2003). Unfortunately, at this time, few advances in the identification of the pathways or proteins targeted by plant pathogen effectors have resulted from these yeast screens. However, additional strategies, including chemical targeting of specific pathways or stress‐inducing conditions prior to effector expression, may reveal further clues to effector function in yeast.

The loss‐of‐function and gain‐of‐function assays described thus far demonstrate that AvrPtoB is a multifunctional protein capable of suppressing both general and specific elicitation of ETI, as well as early signalling in PTI. However, the determination of the details of the mechanism of action and specific targets of the effector requires additional tools.

EFFECTOR FUNCTION: DEFINING THE MECHANISM OF ACTION THROUGH HOMOLOGY

The primary goal of much effector research is to identify the host targets and to understand how effectors manipulate these targets. Only a small portion of the puzzle of effector function in plants has been understood to date, although significant progress has been made in unravelling how effectors suppress the plant immune response. During the early days of effector mining, it became apparent that, although some effectors exhibit primary amino acid sequence similarity to proteins with known functions, most do not (Bretz et al., 2003; Espinosa et al., 2003; Petnicki‐Ocwieja et al., 2002). The use of iterative blast searches helped to group effectors, not obviously homologous to other proteins, into activity classes. Using this approach, the P. syringae pv. phaseolicola effector, AvrPphB, and the DC3000 effector, HopN1, were classified as members of the YopT family of effectors, named for YopT, an effector from the human plague pathogen Yersinia pestis (Shao et al., 2002). Like YopT, both HopN1 and AvrPphB possess cysteine protease activity (Lopez‐Solanilla et al., 2004; Shao et al., 2002). Mutations affecting enzymatic activity have been shown to be required for effector virulence and avirulence activity.

EFFECTOR FUNCTION: DEFINING MECHANISM OF ACTION THROUGH STRUCTURAL BIOLOGY

However, some effectors, including AvrPtoB and AvrPto, have been refractory to homology searches, yielding no significant clues to their functions. For these effectors, it seemed that the best path to function was structural biology. Because the C‐terminal portion of AvrPtoB appears to function independently of the N‐terminus to suppress general cell death in plants (Abramovitch et al., 2003), Janjusevic et al. (2006) analysed the crystal structure of AvrPtoB, amino acids 436–553. The structure revealed similarity to eukaryotic RING‐finger‐ and U‐box‐containing proteins that function as E3 ubiquitin ligases. Accordingly, the C‐terminus of AvrPtoB exhibits ubiquitin ligase activity in a cell‐free system. AvrPtoB mutants with disrupted E3 ubiquitin ligase activity elicit Rsb when delivered by P. syringae into tomato plants, or cell death when transiently transformed into N. benthamiana leaves. These results illustrate the correspondence between ubiquitin ligase activity and suppression of Rsb‐mediated ETI.

In contrast, NMR structural analysis of AvrPto did not lead to a definitive enzymatic activity for the protein. However, it did provide clues to regions of the protein likely to interact with substrates, including Pto (Wulf et al., 2004). Structural analysis of the AvrPto–Pto complex revealed additional details about the function of AvrPto to signal an immune response through its interaction with Pto (Xing et al., 2007). A similar analysis of the N‐terminus of AvrPtoB (amino acids 121–205), alone and complexed with Pto, demonstrated that the N‐terminal region of AvrPtoB does not change conformation on Pto binding (Dong et al., 2009). The analysis identified both a shared Pto interaction interface with AvrPto and a Pto interaction interface unique to AvrPtoB. Clearly, structural analysis is not the panacea for functional elucidation of all effectors, but for some it can be extremely informative about the mechanism of effector action.

EFFECTOR FUNCTION: IDENTIFICATION OF HOST TARGETS BY INTERACTION

Even after elucidating a host process perturbed by an effector and the mechanism by which the effector acts on that process, the question of what host protein(s) is being targeted leading to enhanced virulence may still remain, as was the case for AvrPtoB. One of the most common ways to answer this question is to identify host proteins that physically interact with an effector. Although several methods exist, the most frequently utilized is the yeast two‐hybrid system. This method was successful in identifying the host targets of two DC3000 effectors, HopM1 and HopU1 (Fu et al., 2007; Nomura et al., 2006).

Concurrent with the AvrPtoB C‐terminus crystal structure analysis, an alternative approach was used to decipher the function of this multipurpose effector (Abramovitch et al., 2006). Screening of a tomato yeast two‐hybrid library with full‐length AvrPtoB yielded ubiquitin as the strongest interactor. This study also confirmed that AvrPtoB possesses E3 ubiquitin ligase activity and that the activity is required for suppressing Rsb. In this case, yeast two‐hybrid analysis generated information regarding the mechanism by which AvrPtoB functions but not its target.

A second tomato protein identified in the same yeast two‐hybrid screen is Bti9 (R. Abramovitch and G. Martin, unpublished). Bti9 shares homology with LysM domain containing RLKs and is hypothesized to recognize peptidoglycan as a PAMP leading to PTI in tomato (L. Zeng and G. Martin, unpublished). The closest Arabidopsis homologue of Bti9 is CERK1, which was recently shown to be a target of AvrPtoB and will be discussed in a subsequent section of this review (Gimenez‐Ibanez et al., 2009).

The yeast two‐hybrid system provides a simple means for identifying putative interactors, yet several limitations exist for this technology. Foremost, high numbers of false positives may result due to auto‐activation of reporter genes, protein overexpression itself, or aberrant interaction of proteins that would normally exist in different compartments of the cell in planta. Therefore, interactions must be confirmed by alternative methods and the relevance of the interaction to the action of the effector must be defined. With any in vivo technique proposed to detect protein‐protein interactions, the presence of a third protein bridging the interaction between the effector and the host protein remains a possibility. Lastly, because standard yeast two‐hybrid methods rely on interactions occurring in the yeast nucleus, the chance of identifying interactions with membrane proteins, which comprise up to one third of eukaryotic proteomes, is diminished. However, the cDNA cloning process may result in truncated forms of proteins allowing for interactions with the cytoplasmic domains of membrane‐associated proteins to occur. Alternatively, the use of the split‐ubiquitin system can compensate for this disadvantage, because interaction is detected at the membrane (Thaminy et al., 2004).

A second option for the high‐throughput identification of novel effector‐interacting proteins is affinity purification followed by mass spectroscopy. This method benefits from the use of proteins expressed natively in the host; however, interactions occur in host extracts where disruption of cellular compartments may bring together proteins that would not normally co‐exist in the cell. This technique allows for detection of proteins present together in a complex, but does not specifically detect direct interactions. As with the yeast two‐hybrid approach, putative interactors must be verified through rigorous follow‐up experiments. Although this technique is a viable option for identifying effector targets, to our knowledge it has not yet been used to identify P. syringae effector host protein interactions. A recent review discusses the advantages and disadvantages of various protein interaction methods (Lalonde et al., 2008).

EFFECTOR FUNCTION: CANDIDATE HOST TARGETS

Consideration of the decoy model has facilitated the selection of some candidate effector targets (van der Hoorn and Kamoun, 2008). For instance, the proposed decoy for AvrPtoB and AvrPto activity is the tomato kinase, Pto. If Pto mimics the true targets of both effectors, the targets are also likely to be kinases. Analyses of candidate targets have been accomplished with pairwise assays for effector‐interacting proteins. Based on sequence similarity with Pto, the PAMP RLKs FLS2 and EFR were tested, and their kinase domains were verified to interact with AvrPto through a series of assays, including co‐immunoprecipitation and bimolecular fluorescent complementation, as in vivo demonstrations of interaction, and in vitro pull‐down assays and surface plasmon resonance, as in vitro demonstrations of direct interaction (Xiang et al., 2007). AvrPto also inhibits the autophosphorylation of RLKs, suggesting kinase inhibition as a possible mechanism for PTI suppression in plants. A typical strategy to confirm the relevance of a putative target in pathogen virulence is to test for the abrogation of enhanced virulence caused by the effector in the absence of the target. For example, a DC3000 strain lacking AvrPto grows to levels equal to wild‐type DC3000 in the Arabidopsis fls2 mutant, but exhibits growth deficiency compared with DC3000 in wild‐type plants.

In a similar study, AvrPto and AvrPtoB were shown to interact with FLS2 and its co‐receptor, BAK1, and, in the process, disrupt the flg22‐induced FLS2–BAK1 complex (Shan et al., 2008). In this case, BAK1 was chosen as a candidate on the basis of its role in brassinosteroid perception and the phenotypic similarity of AvrPto‐expressing transgenic Arabidopsis to brassinosteroid‐insensitive plants (see above). Interestingly, the regions of AvrPtoB that were shown to be required for several PTI suppression assays (He et al., 2006) are also required for BAK1 interaction and disruption of the FLS2–BAK1 complex (Shan et al., 2008). This correlation did not hold for AvrPtoB interaction with Pto or FLS2. The experiments described above all rely on the overexpression of proteins in plant cells. In order to confirm these responses with a disease model, disruption of the FLS2–BAK1 complex was examined in response to both wild‐type DC3000 and the DC3000 avrPto/avrPtoB double mutant. The authors found that, by 2 h post‐infection, the wild‐type strain disrupted the complex, whereas the complex remained intact after infection with the mutant strain.

A candidate approach was also taken by Rosebrock et al. (2007) to show that Fen, a Pto family member, is the R protein recognizing forms of AvrPtoB lacking E3 ubiquitin ligase activity. Furthermore, full‐length AvrPtoB targets Fen for ubiquitination and subsequent degradation, restoring susceptibility to the host. Here, members of the Pto family were chosen as candidates on the basis of the previous finding that Rsb is dependent on the NB‐LRR protein Prf in tomato (Abramovitch et al., 2003). To test this hypothesis further, a stable transgenic tomato line exhibiting knocked‐down expression of the Pto gene family was assayed for the Rsb phenotype (Rosebrock et al., 2007). Indeed, expression of the Pto gene family is necessary for resistance. Next, a protoplast cell death assay was used to demonstrate that Fen, but not other Pto‐related proteins, is responsible for Rsb. A recent report presents evidence supporting one possibility for how Pto avoids ubiquitination and subsequent degradation by AvrPtoB. Pto was shown to phosphorylate AvrPtoB near its E3 ubiquitin ligase domain, disabling its enzymatic activity, and allowing recognition to occur (Ntoukakis et al., 2009).

Several advances in the study of host immunity and effector functional analysis have benefited from the use of RNA interference (RNAi), gene silencing and mutagenesis of candidate host targets or processes. As a previously mentioned example, FLS2 was confirmed as a target of AvrPto using a virulence assay in fls2 mutant plants (Xiang et al., 2007). In a recent study, microRNAs (miRNAs) were hypothesized to play a role in host immunity against bacteria (Navarro et al., 2008). Arabidopsis plants containing mutations in genes required for two distinct steps of miRNA generation display enhanced growth of three nonpathogenic bacterial strains compared with the wild‐type. Because the miRNA pathway appears to be important for PTI, it was hypothesized that effectors might target this pathway to suppress immunity. In fact, several PAMP‐responsive miRNAs are suppressed on infection with wild‐type DC3000. Agrobacterium‐mediated transient expression of AvrPtoB in efr mutant Arabidopsis plants suppresses transcription of the PAMP‐responsive miRNAs independent of its E3 ubiquitin ligase domain. It is unclear whether this is a direct effect of AvrPtoB or, as seems more likely, caused by AvrPtoB‐mediated inhibition of upstream PAMP receptors.

The extensive collection of T‐DNA insertion mutant lines in Arabidopsis makes this species an ideal system in which to study candidate effector host targets. It is possible to find lines that are knockouts for many genes of interest, whereas, with silencing and RNAi, there is often a background level of gene expression that must be considered. Furthermore, mutant lines and stable RNAi lines can be crossed with one another to study the effects of multiple genes at once. The major advantage of silencing and RNAi is the ability to knock down the expression of multiple related genes in a single plant. This can be accomplished because as few as 23 consecutive nucleotides of homology with the endogenous gene are necessary for silencing (Thomas et al., 2001).

RECENT DISCOVERIES ABOUT AvrPtoB VIRULENCE FUNCTION

The research discussed up to this point indicates that the C‐terminus of AvrPtoB is not required for the suppression of PTI in plants (He et al., 2006; Shan et al., 2008; Xiao et al., 2007b; de Torres et al., 2006). However, two papers published in the last year report evidence for a role of the E3 ligase in PTI suppression using combinations of the methods reviewed here.

Göhre et al. (2008) showed that normal localization of the PAMP receptor, FLS2, to the membrane is lost on infection of FLS2‐green fluorescent protein (GFP) transgenic Arabidopsis plants with DC3000. Infection with either a DC3000 T3SS mutant strain or a strain lacking AvrPtoB does not cause a loss of localization, demonstrating a requirement for AvrPtoB. Intriguingly, FLS2 protein levels are diminished on treatment with flg22 and expression of AvrPtoB, whereas treatment with either alone is ineffective. Furthermore, incubation with the proteasome inhibitor MG132 restores FLS2 protein accumulation to untreated levels, suggesting a role for the E3 ubiquitin ligase domain of AvrPtoB in the decreased stability of activated FLS2. Indeed, AvrPtoB ubiquitinates the cytoplasmic domain of FLS2, EFR, and, to a lesser extent, BAK1 in in vitro assays. In vivo ubiquitination assays in AvrPtoB‐expressing transgenic plants show that native FLS2 is ubiquitinated in the presence of AvrPtoB independent of treatment with flg22. Interestingly, native FLS2 is also ubiquitinated on treatment with flg22 alone, suggesting that ubiquitination by endogenous enzymes may trigger endocytosis and degradation of the activated receptor.

To test whether FLS2 is a genuine target of AvrPtoB E3 ligase activity, a virulence assay was performed on wild‐type and fls2 plants with DC3000, a mutant of DC3000 lacking AvrPtoB and an AvrPtoB mutant complemented with the N‐terminal 387 amino acids of AvrPtoB expressed from a plasmid (Göhre et al., 2008). In this experiment, the presence of AvrPtoB provides no increase in bacterial growth in the fls2 mutant, whereas, in wild‐type plants, AvrPtoB causes an increase in growth. This result supports the hypothesis that FLS2 is targeted by AvrPtoB to increase virulence. Interestingly, the addition of AvrPtoB1–387 does not lead to enhanced growth in either plant, suggesting that the virulence function of AvrPtoB requires E3 ubiquitin ligase activity in Arabidopsis.

A second paper has reported that AvrPtoB targets the LysM RLK, CERK1, in Arabidopsis plants (Gimenez‐Ibanez et al., 2009). Bti9, described above as an interactor of AvrPtoB, is the tomato orthologue of CERK1. CERK1 is required for chitin perception, and its activation leads to the induction of PTI in response to certain fungal pathogens (Wan et al., 2008). It has also been hypothesized to function as a receptor for related compounds, including bacterial peptidoglycan. The authors showed that cerk1 mutant plants support enhanced bacterial growth of both wild‐type DC3000 and a T3SS mutant when compared with wild‐type plants, suggesting a role for CERK1 in PTI against bacterial pathogens (Gimenez‐Ibanez et al., 2009). In addition, several DC3000 effectors, including AvrPtoB, exhibit the inhibition of chitin responses in wild‐type plants, supporting the importance of a CERK1‐mediated pathway in the immune response.

The authors proposed a model in which AvrPtoB inhibits CERK1 via direct ubiquitination and degradation based on several pieces of evidence (Gimenez‐Ibanez et al., 2009). First, AvrPtoB and its derivatives were shown to interact with the CERK1 kinase domain in yeast in a manner similar to Pto. Second, an AvrPtoB mutation and a truncation that abolished ubiquitin ligase activity displayed reduced ability to inhibit chitin responses in N. benthamiana. Third, AvrPtoB ubiquitinates CERK1 in vitro and leads to a reduction in CERK1 protein abundance in planta, both of which require a functional AvrPtoB E3 ubiquitin ligase domain. Finally, an AvrPtoB mutant lacking E3 ubiquitin ligase activity does not enhance the growth of the plasmid‐cured strain of P. syringae pv. phaseolicola which is normally nonpathogenic on Arabidopsis, described above. However, because of the significantly reduced abundance of the AvrPtoB variant proteins lacking E3 ubiquitin ligase activity, some of the data do not convincingly support the proposed indispensability of the E3 ligase domain for suppressing CERK1‐mediated PTI. Interestingly, the proteosomal inhibitor, MG132, does not suppress AvrPtoB‐mediated degradation of CERK1, whereas the vacuolar‐type H+‐ATPase inhibitor Bafilomycin A1 does, suggesting the involvement of an endosomal sorting pathway for vacuolar degradation. This pathway is typically used for the down‐regulation of activated receptors that have been monoubiquitinated, and may be an intriguing possibility for AvrPtoB‐mediated inhibition of CERK1 or involvement of the endogenous receptor recycling pathway (d'Azzo et al., 2005).

CONCLUSIONS

AvrPtoB is one example of a multidomain, multifunctional effector protein. Whether other effectors will have similar diverse activities remains to be seen. On the surface, the literature reviewed here suggests that AvrPtoB is able to suppress the majority of readouts for all plant immune responses tested. However, on further examination, it is apparent that only two distinct activities have been demonstrated for AvrPtoB: suppression of Fen‐mediated ETI and inhibition of PTI signalling at the level of PRRs. Whether naturally delivered AvrPtoB can suppress general cell death, as observed previously using Agrobacterium‐mediated transformation in N. benthamiana, remains to be shown (Abramovitch et al., 2003).

Current evidence supports a model for the inhibition of multiple RLKs by AvrPtoB to suppress PTI in plants. Because RLKs function at the initial steps in PAMP recognition, perturbation of their function by AvrPtoB is likely to lead to dramatic downstream effects. Therefore, this single activity of AvrPtoB can explain all of the PTI suppression‐related phenotypes observed, including miRNA suppression.

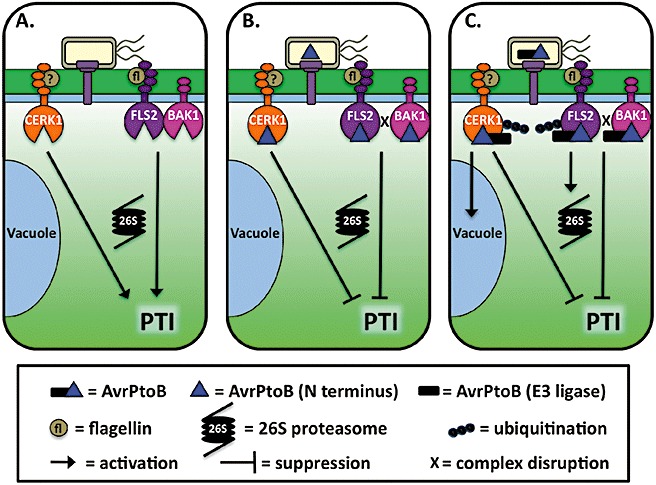

But how can a protein that is thought to be delivered in limited amounts by the T3SS disable all of the PRRs in the cell? PTI is a locally induced immune response. Therefore, it is reasonable to expect that only the PRRs in the vicinity of the delivering bacterium are activated by PAMPs. Under these circumstances, AvrPtoB needs to inhibit only the neighbouring PRRs that have been activated. Whether this process requires AvrPtoB E3 ubiquitin ligase activity remains to be conclusively shown. However, the model shown in Fig. 2 can accommodate the possibility for an obligatory or a partial role of the E3 ubiquitin ligase in the suppression of PTI.

Figure 2.

AvrPtoB virulence activity in Arabidopsis. (A) In the absence of AvrPtoB, FLS2 and CERK1 recognize flagellin and an unknown molecule as pathogen (or microbe)‐associated molecular patterns (PAMPs), respectively, leading to PAMP‐triggered immunity (PTI). (B) Delivery of the N‐terminal region of AvrPtoB suppresses the induction of PTI by flagellin by disrupting the FLS2–BAK1 complex necessary for signalling and by possibly inhibiting FLS2 and CERK1 kinase activity. (C) Delivery of full‐length AvrPtoB suppresses PTI in the same manner as the N‐terminal region. In addition, the C‐terminal E3 ubiquitin ligase domain may promote ubiquitination of FLS2 and CERK1, either directly or by the endogenous receptor recycling pathway that functions through the 26S proteasome or the vacuolar degradation pathways. Degradation of the activated receptors may provide insurance that the receptor remains inactive after AvrPtoB dissociates and frees up the effector to act on another substrate.

Perhaps AvrPtoB disrupts receptor–co‐receptor complexes, such as FLS2–BAK1, via its N‐terminus. Subsequently, utilizing its E3 ubiquitin ligase activity, AvrPtoB promotes the internalization and degradation of the receptor, in this case FLS2 or CERK1/Bti9. This would free up a limited number of AvrPtoB molecules to target other PRR complexes. Moreover, in this scenario, the E3 ubiquitin ligase activity would not be observed as necessary for PTI suppression in gain‐of‐function assays in which high levels of AvrPtoB are produced. It is also noteworthy to revisit HopPmaL when considering the importance of the C‐terminus in PTI suppression. HopPmaL is a naturally occurring truncated homologue of AvrPtoB from P. syringae pv. maculicola which lacks the E3 ubiquitin ligase domain, yet retains virulence activity in tomato (Lin et al., 2006).

As the targets and mechanism(s) of AvrPtoB and other effectors are elucidated, it is important to keep in mind the value of combining loss‐of‐function and gain‐of‐function assays, each with their unique sets of advantages and disadvantages. Together, the methods addressed in this article and novel assays yet to be developed will support the field of P. syringae effector functional analysis for years to come, leading to a better understanding of the plant immune system and how pathogens overcome these responses and cause disease.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank Dr Jesse Munkvold for critical reading of the manuscript. Research in the Martin laboratory on the topics of this article is supported by National Institutes of Health grant no. R01GM078021 and National Science Foundation grant no. DBI‐0605059 to GBM.

REFERENCES

- Abramovitch, R.B. , Janjusevic, R. , Stebbins, C.E. and Martin, G.B. (2006) Type III effector AvrPtoB requires intrinsic E3 ubiquitin ligase activity to suppress plant cell death and immunity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA, 103, 2851–2856. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abramovitch, R.B. , Kim, Y.J. , Chen, S. , Dickman, M.B. and Martin, G.B. (2003) Pseudomonas type III effector AvrPtoB induces plant disease susceptibility by inhibition of host programmed cell death. EMBO J., 22, 60–69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ade, J. , Deyoung, B. , Golstein, C. and Innes, R.W. (2007) Indirect activation of a plant nucleotide binding site‐leucine‐rich repeat protein by a bacterial protease. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA, 104, 2531–2536. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alfano, J.R. and Collmer, A. (1996) Bacterial pathogens in plants: life up against the wall. Plant Cell, 8, 1683–1698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Almeida, N. , Yan, S. , Lindeberg, M. , Studholme, D. , Schneider, D. , Condon, B. , Liu, H. , Viana, C. , Warren, A. , Evans, C. , Kemen, E. , Maclean, D. , Angot, A. , Martin, G.B. , Jones, J. , Collmer, A. , Setubal, J. and Vinatzer, B.A. (2009) A draft genome sequence of Pseudomonas syringae pv. tomato T1 reveals a type III effector repertoire significantly divergent from that of Pseudomonas syringae pv. tomato DC3000. Mol. Plant Microbe. Interact., 22, 52–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson, J.C. , Pascuzzi, P.E. , Xiao, F. , Sessa, G. and Martin, G.B. (2006) Host‐mediated phosphorylation of type III effector AvrPto promotes Pseudomonas virulence and avirulence in tomato. Plant Cell, 18, 502–514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asai, T. , Tena, G. , Plotnikova, J. , Willmann, M.R. , Chiu, W.L. , Gomez‐Gomez, L. , Boller, T. , Ausubel, F. and Sheen, J. (2002) MAP kinase signalling cascade in Arabidopsis innate immunity. Nature, 415, 977–983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ashfield, T. , Keen, N.T. , Buzzell, R.I. and Innes, R.W. (1995) Soybean resistance genes specific for different Pseudomonas syringae avirulence genes are allelic, or closely linked, at the RPG1 locus. Genetics, 141, 1597–1604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Axtell, M. , Chisholm, S.T. , Dahlbeck, D. and Staskawicz, B.J. (2003) Genetic and molecular evidence that the Pseudomonas syringae type III effector protein AvrRpt2 is a cysteine protease. Mol. Microbiol., 49, 1537–1546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Axtell, M. and Staskawicz, B.J. (2003) Initiation of RPS2‐specified disease resistance in Arabidopsis is coupled to the AvrRpt2‐directed elimination of RIN4. Cell, 112, 369–377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Badel, J.L. , Nomura, K. , Bandyopadhyay, S. , Shimizu, R. , Collmer, A. and He, S.Y. (2003) Pseudomonas syringae pv. tomato DC3000 HopPtoM (CEL ORF3) is important for lesion formation but not growth in tomato and is secreted and translocated by the Hrp type III secretion system in a chaperone‐dependent manner. Mol. Microbiol., 49, 1239–1251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Badel, J.L. , Shimizu, R. , Oh, H.S. and Collmer, A. (2006) A Pseudomonas syringae pv. tomato avrE1/hopM1 mutant is severely reduced in growth and lesion formation in tomato. Mol. Plant-Microbe Interact., 19, 99–111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belkhadir, Y. , Nimchuk, Z. , Hubert, D.A. , Mackey, D. and Dangl, J.L. (2004) Arabidopsis RIN4 negatively regulates disease resistance mediated by RPS2 and RPM1 downstream or independent of the NDR1 signal modulator and is not required for the virulence functions of bacterial type III effectors AvrRpt2 or AvrRpm1. Plant Cell, 16, 2822–2835. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bent, A.F. , Innes, R.W. , Ecker, J.R. and Staskawicz, B.J. (1992) Disease development in ethylene‐insensitive Arabidopsis thaliana infected with virulent and avirulent Pseudomonas and Xanthomonas pathogens. Mol. Plant Microbe. Interact., 5, 372–378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bisgrove, S.R. , Simonich, M.T. , Smith, N.M. , Sattler, A. and Innes, R.W. (1994) A disease resistance gene in Arabidopsis with specificity for two different pathogen avirulence genes. Plant Cell, 6, 927–933. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bogdanove, A.J. and Martin, G.B. (2000) AvrPto‐dependent Pto‐interacting proteins and AvrPto‐interacting proteins in tomato. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA, 97, 8836–8840. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bretz, J.R. , Mock, N.M. , Charity, J.C. , Zeyad, S. , Baker, C.J. and Hutcheson, S.W. (2003) A translocated protein tyrosine phosphatase of Pseudomonas syringae pv. tomato DC3000 modulates plant defence response to infection. Mol. Microbiol., 49, 389–400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buell, C.R. , Joardar, V. , Lindeberg, M. , Selengut, J. , Paulsen, I.T. , Gwinn, M.L. , Dodson, R.J. , Deboy, R.T. , Durkin, A.S. , Kolonay, J.F. , Madupu, R. , Daugherty, S. , Brinkac, L. , Beanan, M.J. , Haft, D.H. , Nelson, W.C. , Davidsen, T. , Zafar, N. , Zhou, L. , Liu, J. , Yuan, Q. , Khouri, H. , Fedorova, N. , Tran, B. , Russell, D. , Berry, K. , Utterback, T. , Van Aken, S.E. , Feldblyum, T.V. , D'Ascenzo, M. , Deng, W.L. , Ramos, A.R. , Alfano, J.R. , Cartinhour, S. , Chatterjee, A.K. , Delaney, T.P. , Lazarowitz, S.G. , Martin, G.B. , Schneider, D. , Tang, X. , Bender, C. , White, O. , Fraser, C.M. and Collmer, A. (2003) The complete genome sequence of the Arabidopsis and tomato pathogen Pseudomonas syringae pv. tomato DC3000. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA, 100, 10181–10186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang, J.H. , Rathjen, J.P. , Bernal, A.J. , Staskawicz, B.J. and Michelmore, R.W. (2000) avrPto enhances growth and necrosis caused by Pseudomonas syringae pv. tomato in tomato lines lacking either Pto or Prf . Mol. Plant Microbe. Interact., 13, 568–571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang, J.H. , Urbach, J.M. , Law, T.F. , Arnold, L.W. , Hu, A. , Gombar, S. , Grant, S. , Ausubel, F. and Dangl, J.L. (2005) A high‐throughput, near‐saturating screen for type III effector genes from Pseudomonas syringae . Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA, 102, 2549–2554. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Z. , Agnew, J.L. , Cohen, J.D. , He, P. , Shan, L. , Sheen, J. and Kunkel, B.N. (2007) Pseudomonas syringae type III effector AvrRpt2 alters Arabidopsis thaliana auxin physiology. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA, 104, 20131–20136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Z. , Kloek, A. , Cuzick, A. , Moeder, W. , Tang, D. , Innes, R.W. , Klessig, D. , Mcdowell, J. and Kunkel, B.N. (2004) The Pseudomonas syringae type III effector AvrRpt2 functions downstream or independently of SA to promote virulence on Arabidopsis thaliana . Plant J., 37, 494–504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Z. , Kloek, A.P. , Boch, J. , Katagiri, F. and Kunkel, B.N. (2000) The Pseudomonas syringae avrRpt2 gene product promotes pathogen virulence from inside plant cells. Mol. Plant Microbe. Interact., 13, 1312–1321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chisholm, S.T. , Coaker, G. , Day, B. and Staskawicz, B.J. (2006) Host‐microbe interactions: shaping the evolution of the plant immune response. Cell, 124, 803–814. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chisholm, S.T. , Dahlbeck, D. , Krishnamurthy, N. , Day, B. , Sjolander, K. and Staskawicz, B.J. (2005) Molecular characterization of proteolytic cleavage sites of the Pseudomonas syringae effector AvrRpt2. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA, 102, 2087–2092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coaker, G. , Falick, A. and Staskawicz, B. (2005) Activation of a phytopathogenic bacterial effector protein by a eukaryotic cyclophilin. Science, 308, 548–550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohn, J. and Martin, G.B. (2005) Pseudomonas syringae pv. tomato type III effectors AvrPto and AvrPtoB promote ethylene‐dependent cell death in tomato. Plant J., 44, 139–154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cunnac, S. , Lindeberg, M. and Collmer, A. (2009) Pseudomonas syringae type III secretion system effectors: repertoires in search of functions. Current Opinion in Microbiology, 12, 53–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D'Azzo, A. , Bongiovanni, A. and Nastasi, T. (2005) E3 ubiquitin ligases as regulators of membrane protein trafficking and degradation. Traffic, 6, 429–441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dangl, J.L. and Jones, J.D. (2001) Plant pathogens and integrated defence responses to infection. Nature, 411, 826–833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Torres, M. , Mansfield, J. , Grabov, N. , Brown, I. , Ammouneh, H. , Tsiamis, G. , Forsyth, A. , Robatzek, S. , Grant, M. and Boch, J. (2006) Pseudomonas syringae effector AvrPtoB suppresses basal defence in Arabidopsis. Plant J., 47, 368–382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Torres‐Zabala, M. , Truman, W. , Bennett, M.H. , Lafforgue, G. , Mansfield, J. , Rodriguez Egea, P. , Bögre, L. and Grant, M. (2007) Pseudomonas syringae pv. tomato hijacks the Arabidopsis abscisic acid signalling pathway to cause disease. EMBO J., 26, 1434–1443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Debroy, S. , Thilmony, R. , Kwack, Y.B. , Nomura, K. and He, S.Y. (2004) A family of conserved bacterial effectors inhibits salicylic acid‐mediated basal immunity and promotes disease necrosis in plants. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA, 101, 9927–9932. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Desveaux, D. , Singer, A.U. , Wu, A. , Mcnulty, B. , Musselwhite, L. , Nimchuk, Z. , Sondek, J. and Dangl, J.L. (2007) Type III effector activation via nucleotide binding, phosphorylation, and host target interaction. PLoS Pathog., 3, e48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deyoung, B. and Innes, R.W. (2006) Plant NBS‐LRR proteins in pathogen sensing and host defense. Nat. Immunol., 7, 1243–1249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dong, J. , Xiao, F. , Fan, F. , Gu, L. , Cang, H. , Martin, G.B. and Chai, J. (2009) Crystal structure of the complex between Pseudomonas effector AvrPtoB and the Pto tomato kinase reveals it has both a shared and a unique interface compared with AvrPto‐Pto. Plant Cell, 21, 1846–1859. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Espinosa, A. , Guo, M. , Tam, V.C. , Fu, Z.Q. and Alfano, J.R. (2003) The Pseudomonas syringae type III‐secreted protein HopPtoD2 possesses protein tyrosine phosphatase activity and suppresses programmed cell death in plants. Mol. Microbiol., 49, 377–387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feil, H. , Feil, W.S. , Chain, P. , Larimer, F. , DiBartolo, G. , Copeland, A. , Lykidis, A. , Trong, S. , Nolan, M. , Goltsman, E. , Thiel, J. , Malfatti, S. , Loper, J.E. , Lapidus, A. , Detter, J.C. , LAnd, M. , Richardson, P.M. , Kyrpides, N.C. , Ivanova, N. and Lindow, S.E. (2005) Comparison of the complete genome sequences of Pseudomonas syringae pv. syringae B728a and pv. tomato DC3000. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA, 102, 11064–11069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flor, H.H. (1956) The complementary genic systems in flax and flax rust. Adv. Genet., 8, 29–54. [Google Scholar]

- Fu, Z.Q. , Guo, M. , Jeong, B. , Tian, F. , Elthon, T. , Cerny, R. , Staiger, D. and Alfano, J.R. (2007) A type III effector ADP‐ribosylates RNA‐binding proteins and quells plant immunity. Nature, 447, 284–288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gimenez‐Ibanez, S. , Hann, D.R. , Ntoukakis, V. , Petutschnig, E. , Lipka, V. and Rathjen, J.P. (2009) AvrPtoB targets the LysM receptor kinase CERK1 to promote bacterial virulence on plants. Curr. Biol., 19, 423–429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glazebrook, J. , Rogers, E.E. and Ausubel, F.M. (1997) Use of Arabidopsis for genetic dissection of plant defense responses. Annu. Rev. Genet., 31, 547–569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goel, A. , Lundberg, D. , Torres, M. , Matthews, R. , Akimoto‐Tomiyama, C. , Farmer, L. , Dangl, J.L. and Grant, S. (2008) The Pseudomonas syringae type III effector HopAM1 enhances virulence on water‐stressed plants. Mol. Plant Microbe. Interact., 21, 361–370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Göhre, V. , Spallek, T. , Häweker, H. , Mersmann, S. , Mentzel, T. , Boller, T. , De Torres, M. , Mansfield, J. and Robatzek, S. (2008) Plant pattern‐recognition receptor FLS2 is directed for degradation by the bacterial ubiquitin ligase AvrPtoB. Curr. Biol., 18, 1824–1832. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gómez‐Gómez, L. , Felix, G. and Boller, T. (1999) A single locus determines sensitivity to bacterial flagellin in Arabidopsis thaliana . Plant J., 18, 277–284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodin, M. , Zaitlin, D. , Naidu, R. and Lommel, S. (2008) Nicotiana benthamiana: its history and future as a model for plant‐pathogen interactions. Mol. Plant Microbe. Interact., 21, 1015–1026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grant, M.R. , Godiard, L. , Straube, E. , Ashfield, T. , Lewald, J. , Sattler, A. , Innes, R.W. and Dangl, J.L. (1995) Structure of the Arabidopsis RPM1 gene enabling dual specificity disease resistance. Science, 269, 843–846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo, M. , Chancey, S.T. , Tian, F. , Ge, Z. , Jamir, Y. and Alfano, J.R. (2005) Pseudomonas syringae type III chaperones ShcO1, ShcS1, and ShcS2 facilitate translocation of their cognate effectors and can substitute for each other in the secretion of HopO1‐1. Journal of Bacteriology, 187, 4257–4269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guttman, D.S. and Greenberg, J.T. (2001) Functional analysis of the type III effectors AvrRpt2 and AvrRpm1 of Pseudomonas syringae with the use of a single‐copy genomic integration system. Mol. Plant Microbe. Interact., 14, 145–155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hann, D.R. and Rathjen, J.P. (2007) Early events in the pathogenicity of Pseudomonas syringae on Nicotiana benthamiana . Plant J., 49, 607–618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hauck, P. , Thilmony, R. and He, S.Y. (2003) A Pseudomonas syringae type III effector suppresses cell wall‐based extracellular defense in susceptible Arabidopsis plants. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA, 100, 8577–8582. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He, P. , Shan, L. , Lin, N.C. , Martin, G.B. , Kemmerling, B. , Nürnberger, T. and Sheen, J. (2006) Specific bacterial suppressors of MAMP signaling upstream of MAPKKK in Arabidopsis innate immunity. Cell, 125, 563–575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Initiative, T.A. G. (2000) Analysis of the genome sequence of the flowering plant Arabidopsis thaliana . Nature, 408, 796–815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson, R.W. , Athanassopoulos, E. , Tsiamis, G. , Mansfield, J.W. , Sesma, A. , Arnold, D.L. , Gibbon, M.J. , Murillo, J. , Taylor, J.D. and Vivian, A. (1999) Identification of a pathogenicity island, which contains genes for virulence and avirulence, on a large native plasmid in the bean pathogen Pseudomonas syringae pathovar phaseolicola . Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA, 96, 10875–10880. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jamir, Y. , Guo, M. , Oh, H. , Petnicki‐Ocwieja, T. , Chen, S. , Tang, X. , Dickman, M.B. , Collmer, A. and Alfano, J.R. (2004) Identification of Pseudomonas syringae type III effectors that can suppress programmed cell death in plants and yeast. Plant J., 37, 554–565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Janjusevic, R. , Abramovitch, R.B. , Martin, G.B. and Stebbins, C.E. (2006) A bacterial inhibitor of host programmed cell death defenses is an E3 ubiquitin ligase. Science, 311, 222–226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jelenska, J. , Yao, N. , Vinatzer, B.A. , Wright, C.M. , Brodsky, J.L. and Greenberg, J.T. (2007) A J domain virulence effector of Pseudomonas syringae remodels host chloroplasts and suppresses defenses. Curr. Biol., 17, 499–508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]