Abstract

Compartment syndrome of the lower leg or foot, a severe complication with a low incidence, is mostly caused by high-energy deceleration trauma. The diagnosis is based on clinical examination and intracompartmental pressure measurement. The most sensitive clinical symptom of compartment syndrome is severe pain. Clinical findings must be documented carefully. A fasciotomy should be performed when the difference between compartment pressure and diastolic blood pressure is less than 30 mm Hg or when clinical symptoms are obvious. Once the diagnosis is made, immediate fasciotomy of all compartments is required. Fasciotomy of the lower leg can be performed either by one lateral incision or by medial and lateral incisions. The compartment syndrome of the foot requires thorough examination of all compartments with special focus on the calcaneal compartment. Depending on the injury, clinical examination, and compartment pressure, fasciotomy is recommended via a dorsal and/or medial plantar approach. Surgical management does not eliminate the risk of developing nerve and muscle dysfunction. When left untreated, poor outcomes with contractures, toe deformities, paralysis, and sensory neuropathy can be expected. In severe cases, amputation may be necessary.

Level of Evidence: Level III. See Guidelines for Authors for a complete description of levels of evidence.

Introduction

Acute compartment syndrome is a complication following fractures, soft tissue trauma, and reperfusion injury after acute arterial obstruction [9, 10, 38, 49, 57]. It is caused by bleeding or edema in a closed, nonelastic muscle compartment surrounded by fascia and bone [47]. The long-term consequences of a compartment syndrome were already described by Richard von Volkmann at the end of the 19th century following application of casts [93]. A few years later, the connection to elevated intracompartmental pressure was made [37].

The incidence of compartment syndrome of the foot is around 6% in patients with foot injuries due to motorcycle accidents [39], while the incidence of compartment syndrome of the lower leg seems even lower (eg, 1.2% after closed tibial diaphyseal fractures [17]). Ischemia causes capillary wall damage and a vicious cycle of events results in permanent nerve and muscle dysfunction [21, 52, 55]. While the existence and treatment of lower leg compartment syndrome was described in 1958 [43], until recently compartment syndrome of the foot was largely unrecognized and only described in some case reports [7, 50, 87]. In 1988, Myerson described the clinical entity and presented surgical decompression as a therapeutic intervention [68]. Trauma surgeons dealing with musculoskeletal injuries must be familiar with treatment of acute compartment syndrome [72].

The aim of this review is to describe (1) the anatomy of the compartments of the lower leg and foot, (2) the pathophysiology, and (3) the diagnosis of compartment syndromes of the lower leg and foot. In contrast to previously published reviews [27, 66, 67], we additionally focus on treatment and outcome of compartment syndromes of the foot and lower leg.

Search Strategy and Criteria

We performed a comprehensive literature search using PubMed at the National Library of Medicine using the keywords “compartment syndrome” combined with “lower leg” or “foot.” This search identified 156 and 194 publications for potential inclusion, respectively. With the additional limits of English or German language and studies on humans, we identified 130 and 157 papers, respectively.

When the search terms “compartment syndrome” and “lower leg” were combined with “outcome” only 24 items and three reviews were identified. Five publications were identified as case reports, and only one study evaluated long-term results [25]. When the search terms “compartment syndrome” and “foot” were combined with “outcome” only 26 publications were identified, while eight were identified as case reports. Two reviews of foot injuries describing compartment syndrome as a relevant entity following trauma were identified. None of the publications evaluated long-term results.

Abstracts of all papers were independently reviewed by two authors (MF and FH). All studies dealing with injuries and disorders causing compartment syndrome of the lower leg or foot as well as case reports and case series were included. We also evaluated cited references to identify papers not identified in the original search. We identified no prospective randomized controlled trials. We did not evaluate study quality in those studies related to treatment.

Anatomy

The lower leg consists of four compartments: anterior, lateral, superficial posterior, and deep posterior (Table 1). In contrast, there is no consensus regarding the number of foot anatomical compartments. In the late 1920s, three compartments were described [32], which were confirmed by Kamel and Sakla in 1961 [42]. However, Myerson later identified four compartments [68] and nine compartments were identified in one cadaver study [46] (Table 2). Only three compartments (medial, lateral, superficial) run the entire length of the foot. Five compartments (four interossei and adductor) are confined to the forefoot. A calcaneal compartment was described by Manoli and Weber in patients developing progressive claw-toe deformities following calcaneal fractures [46]. In a cadaver study exploring the clinical relevance of the barrier between the superficial (flexor digitorum brevis) and the calcaneal compartment (quadratus plantae), the authors demonstrated the barrier became incompetent at a pressure gradient of less than 10 mm Hg; thus, they presumed that barrier would not impair tissue perfusion and allow an independent compartment syndrome [33]. In a recent cadaver study, the authors could not identify distinct myofascial compartments in the forefoot and conclude that a fasciotomy of the hindfoot compartments through a modified medial incision would be sufficient to decompress the foot [44]. Nonetheless, cadaver studies cannot simulate the physiological conditions, and therefore conclusions from these studies should be cautiously interpreted.

Table 1.

Compartments of the lower leg

| Structure | Compartments | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Anterior | Lateral | Superficial Posterior | Deep Posterior | |

| Muscles | Tibialis anterior muscle | Peroneus longus | Gastrocnemius | Tibialis posterior |

| Extensor hallucis longus | Peroneus brevis | Soleus | Flexor hallucis longus | |

| Extensor digitorum longus | Plantaris | Flexor digitorum longus | ||

| Vessels | Anterior tibial artery | Peroneal artery | ||

| Anterior tibial veins | Peroneal vein | |||

| Posterior tibial artery | ||||

| Posterior tibial vein | ||||

| Nerves | Deep peroneal nerve | Common peroneal nerve | Tibial nerve | |

Table 2.

Compartments of the foot

| Compartments | Muscles | Vessels | Nerves |

|---|---|---|---|

| Medial | Flexor hallucis brevis | ||

| Abductor hallucis | |||

| Lateral | Abductor digiti quinti | ||

| Flexor digiti minimi | |||

| Superficial | Flexor digitorum brevis | Medial plantar nerve (?) | |

| Lumbricals | |||

| Flexor digitorum longus tendons | |||

| Interosseus (× 4) | Interossei | ||

| Adductor | Adductor | ||

| Calcaneal | Quadratus plantae | Posterior tibial artery | Posterior tibial nerve |

| Posterior tibial vein | |||

| Lateral plantar artery | Lateral plantar nerve | ||

| Lateral plantar vein | |||

| Medial plantar nerve (?) |

Pathophysiology

Acute compartment syndrome is either caused by bleeding and edema in a closed, relatively nonelastic muscle compartment surrounded by fascia and bone [47] or by a diminution of the intracompartmental space. The most common cause for a compartment syndrome is bleeding, which can develop after vascular injuries or from cancellous bone following fractures or osteotomies. Another cause is edema developing after an increased capillary permeability which also may be due to an oxygen deprivation caused by bleeding. The edema increases the perfusion barrier resulting in hypoxia and acidosis. Following a vicious circle, hypoxia and acidosis again increase capillary permeability and fluid extravasation. Furthermore, the nonelastic osteofascial planes limit volume expansion of the edema and therefore increase the intracompartmental pressure. This leads to a reduced transmural pressure gradient between microcirculation and interstitium, which induces ischemia within the affected compartment [47].

Perfusion within a compartment is only present when the diastolic blood pressure exceeds the intracompartmental pressure [8]. During vasoconstriction or hypertension, perfusion ceases at even lower pressures [47]. Although it is unclear at which pressure tissue damage occurs, clinical studies suggest a difference between diastolic and intracompartmental pressure of less than 30 mm Hg as an indication for fasciotomy. In tibial diaphyseal fractures, this threshold detected all patients with compartment syndrome [53]. Although there are various theories of how compartment syndrome develops, the exact mechanism is unclear. One theory suggests arterial spasm after increased intracompartmental pressure [64]. The most accepted explanation is the theory of local venous hypertension when the intraluminal venous pressure exceeds the interstitial pressure within the compartment allowing a continuous venous flow [47]. Increasing interstitial pressure leads to an increased intraluminal venous pressure preventing vascular collapse. This leads to a decreased gradient between arterioles and veins, which in turn decreases capillary blood flow within the affected compartment. Only 3 hours of experimental ischemia induces an increased capillary permeability and postischemic swelling [26].

While early studies stated irreversible nerve and muscle damage begin after 5 to 6 hours of ischemia [14], more recent clinical studies revealed that muscle necrosis occurs within the first 3 hours [91]. This is earlier than suggested in experimental, tourniquet-induced ischemia studies in which adenosine triphosphate levels were normalized 15 minutes after a 3-hour tourniquet application [36]. However, it seems unclear to which extent results from animal studies can be transferred in the clinical situation. Muscle tissue reacts to ischemia with scar formation resulting in the formation of myotendinous adhesions and contractures [78]. Muscle contracture results in stiffness and deformity distal to the affected compartment. Additionally, muscle necrosis causes myoglobinemia, which may induce renal dysfunction [73].

Accident-independent risk factors for the development of a compartment syndrome are a medical history of anticoagulants and bleeding disorders [72]. Accident-related risk factors include high-velocity or high-energy trauma [5], burn injuries, snake bites, intravenous drug infiltration [96], younger age, obtunded patients [72], and systemic hypotension [81]. In our personal experience (unpublished), 28 of 33 compartment syndromes of the foot were caused by high-energy deceleration trauma. Fifteen cases resulted from falls greater than 2 m, and 13 were caused by motor vehicle accidents. The mean age of patients was 38.4 years.

Compartment syndrome of the lower leg is not only described following trauma, arterial obstruction, lithotomy position [35, 60], and fracture table positioning [2], but also the clinical entity of a chronic exertional compartment syndrome [84] is described. It is an overuse condition mostly in young athletic patients and causes exercise-related pain. The etiology remains unclear. The most affected compartment is the anterior compartment of the lower leg [6], but there are also case reports and case series describing a chronic exertional compartment syndrome of the foot [41, 45, 59, 63, 83]. Although the chronic exertional compartment syndrome is not an acute injury, surgical release is the treatment of choice [89]. In contrast to trauma-associated compartment syndrome, minimally invasive approaches were used at the lower leg with excellent results [18, 61].

Diagnosis

In 1948, Griffiths described four main symptoms of a manifest compartment syndrome: pain, paresthesia, paresis, and pain with stretch (the “four Ps” of an acronym) [31]. More recently, pulse examination and pink skin color were added [11].

Although this review focuses on the acute compartment syndrome of the lower leg and foot, every extremity as well as the abdominal cavity can be affected from a compartment syndrome. Besides the lower leg and foot, the thigh and the forearm especially can be affected by a compartment syndrome [23, 57]. Although we could not find information regarding incidence, high-energy trauma seems to be a risk factor: In a study of industrial roller injuries, three of 11 patients developed a compartment syndrome [3]. The abdominal cavity can be affected as well. It is defined as an intraabdominal pressure of greater than 20 mm Hg and failure of one or more organs [79]. Relief of the compartment by a decompression laparotomy is the treatment of choice [79].

Patients with certain injuries are at risk to develop a compartment syndrome. Chopart and Lisfranc joint dislocations are frequently associated with a foot compartment syndrome. In a study with more than 100 patients, the incidence of foot compartment syndrome in this injury was described in 25% (Chopart dislocations) and 34% (Lisfranc dislocations) of patients [76]. In isolated midfoot fractures, compartment syndrome is rarely observed [24]. Recurrent compartment syndrome of the foot is also a rare entity but is described in the literature [4]. Only a few patients with bilateral compartment syndrome of the foot are reported, but the surgeon must be alert especially in entrapment injuries of the lower extremity [56, 85].

Approximately 2% of diaphyseal tibial fractures are complicated by a compartment syndrome [13, 51]. Intramedullary nailing is associated with an increase in compartment pressure but not with an increased incidence of a compartment syndrome [51]. Reamed intramedullary nailing lowers the pressure in the deep posterior compartment [70]. On the other hand, external fixation was associated with an increased incidence of compartment syndrome compared to intramedullary nailing [54].

Although diagnostic devices are commercially available a complete and careful examination of patients suspected for compartment syndrome is necessary. However, the most important step in diagnosing a compartment syndrome is the surgeon’s awareness of this complication and appropriate clinical examination.

The typical clinical presentation of compartment syndrome of the lower leg and foot is not different from other affected body regions. In a systematic review, pain was identified as the earliest and most sensitive clinical sign of a manifest compartment syndrome [90]. In a retrospective study, foot pain was present in all patients with a manifest compartment syndrome of the foot [66, 69] but it is not specific when other injuries are present. In contrast to injuries without compartment syndromes, immobilization and casts do not reduce the pain. In one study, exacerbation of pain due to passive motion was present in 86% of patients with compartment syndrome of the foot [66]. Pain with passive stretch had comparable sensitivity, specificity, and predictive values [90]. Severe and spontaneous pain is the earliest and most frequent sign of compartment syndrome. The indiscriminate use of analgesics in patients with severe pain can potentially mask the key symptom. Additionally, intoxicated patients suffer from less pain resulting in the underdiagnosis of compartment syndrome.

Sensory deficits are also common in patients with compartment syndrome [90]. Decreased two-point discrimination seems more reliable than decreased pinprick sensation [66]. Frequent examination is needed in the acute phase, if a compartment syndrome is suspected. Although evidence-based recommendations cannot be made, serial examinations at least every hour are essential, since muscle necrosis occurs within 3 hours [91].

Muscle strength is not a good parameter since it is difficult to judge in a patient with injuries and is dependent on pain that may be due to those injuries. Examination of pulses is unreliable in the diagnosis of compartment syndrome since intracompartmental pressure does not reach systolic blood pressure.

Invasive measurement is a quick and safe procedure to diagnose a compartment syndrome. This method was first described in 1975 [94]. Gerngross et al. later developed a system for measurement of the intracompartmental pressure using the principle of piezo-resistance [28, 88]. Recently, devices for continuous pressure monitoring have become commercially available [1, 34]. However, in a cohort study with more than 200 patients with tibial diaphyseal fractures, the use of continuous compartment pressure monitoring did not reveal any differences in outcome and time delay from injury to fasciotomy as compared to clinically examined patients [1]. Another study demonstrated that complication rates and late sequelae were similar in alert patients with or without continuous compartment pressure monitoring [34]. Because at least nine foot compartments have been identified, continuous pressure monitoring is not feasible for patients at risk for developing compartment syndrome of the foot. Only one compartment can be monitored continuously per measuring device. Therefore, serial examinations of the clinical status are necessary to prevent a delay between the established compartment syndrome and surgical release. The highest compartment pressure values are often found after 12 to 36 hours [72]. In uncertain cases, intracompartmental pressure monitoring should be performed in all compartments requiring multiple sticks. Some authors suggest the calcaneal compartment is susceptible to increased pressure [46, 67, 69]. Therefore, special attention should be paid to the calcaneal compartment pressure. The normal pressure values in the foot were investigated by Dayton et al. and revealed values between 4.7 and 6 mm Hg depending on the technique used [15]. This confirms results from the lower leg and other body regions [71, 82], suggesting a comparable physiology.

As previously mentioned, intracompartmental pressure should be correlated with the diastolic blood pressure. The threshold at which a compartment should be decompressed is still debatable. While some authors still favor an absolute value of 30 mm Hg [95], others define 30 mm Hg below the mean arterial pressure or 20 mm Hg below the diastolic blood pressure as a threshold for fasciotomy [72]. Today, the indication for fasciotomy should either rely on clinical findings (neurologic deficits) or on a differential pressure between compartment pressure and diastolic pressure of less than 30 mm Hg [53]. Although most of these recommendations are derived from studies investigating other body regions, there is no reason to presume a different pathophysiological background in foot compartment syndromes. We emphasize that a decreased diastolic blood pressure because of regional anesthesia may have implications for diagnosing compartment syndrome by pressure monitoring systems [58].

Documentation of clinical findings is important in patients with compartment syndrome since serial examinations are necessary and the findings over time must be compared. Recently, inadequate documentation was identified as the most common cause for paid claims in orthopaedic malpractice cases [11]. In another study of patients with suspected compartment syndrome, the authors reported inadequate documentation in 70% of the patients [11].

In summary, the history of substantial trauma and the presence of severe injuries should raise clinical suspicion for the diagnosis of compartment syndrome. Open injuries do not implicitly release the compartments since all nine compartments are rarely affected. Invasive pressure measurement should be considered for a swollen, contused foot with a history of a crush injury. Adequate documentation is necessary to compare the results during the clinical course.

Treatment

Although the management of compartment syndrome consists of immediate surgical treatment, dressings and casts must be completely opened in patients with severe postoperative pain to release extracorporal pressure. In cases with impending compartment syndrome, the extremity should not be elevated since this reduces the already impaired blood flow. A diagnosed compartment syndrome needs immediate fasciotomy as an emergency surgical procedure to release pressure from the affected compartment. The earlier a manifest compartment is released the less likely that long-term sequelae will develop: In patients with tibial fractures, McQueen et al. demonstrated that the time between apparent onset of compartment syndrome and surgical release influenced the outcome rather than the time between trauma and fracture stabilization [51, 52]. Generally, the existing literature is lacking guidelines on what the optimal management of tibial fractures is in the presence of compartment syndrome.

Multiple approaches have been used to decompress the foot compartments [27]. Incisions of the fasciotomy should be planned according to the affected compartments.

Lower Leg

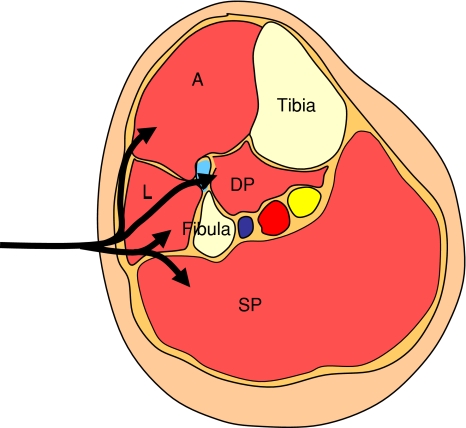

Once a compartment syndrome of the lower leg is diagnosed, many authors recommend all four compartments (anterior, lateral, deep posterior, and superficial posterior) be decompressed throughout the entire length including the retinacula [19]. Decompression can be performed either by a single lateral incision or by combined anterolateral and posteromedial incisions [12]. In tibial fractures, a single incision is recommended to sustain stability of the fracture [17]. Double incision can reduce soft tissue support for the fracture [17]. The parafibular incision must extend the entire length of the lower leg [77]. Incomplete decompression of the affected compartment results in suboptimum outcomes [48]. The intermuscular septum between the lateral and superficial posterior compartment can be identified and should be split longitudinally. Care must be taken not to injure the common and superficial peroneal nerves. The skin is dissected anteriorly and the anterior compartment can be opened. After retracting the peroneal muscles anteriorly, the fascia of the deep posterior compartment becomes visible and must be split along the entire length (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Anatomical section view of the lower leg. The lateral approach uses one longitudinal incision as preferred in our trauma center. L = lateral compartment; A = anterior compartment; DP = deep posterior compartment; SP = superficial posterior compartment.

Foot

Plantar Approach

In the case of an isolated compartment syndrome of the calcaneal compartment with compression of medial and lateral plantar nerves and vessels, a single plantar incision can be considered. However, since lateral compartments are difficult to decompress, we do not generally recommend this approach. The approach starts with an incision following the plantar aspect of the first metatarsal. The medial compartment becomes visible and is split longitudinally. The abductor hallucis should be retracted to reach the other compartments. All wounds are left open to obtain secondary healing, skin graft, or vacuum-assisted closure.

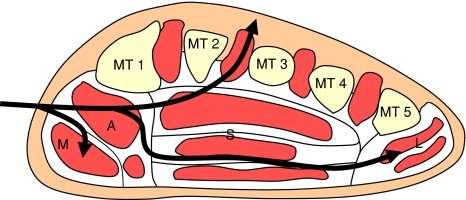

Dorsal Approach

On the assumption that the interosseus compartments are the most affected compartments, Mubarak and Owen recommended a dorsal dermatofasciotomy [62]. This is the incision we most frequently use. The approach can be modified to two dorsal incisions over the second and fourth metatarsals [68]. This approach allows direct access to all compartments, and provides exposure for open reduction and internal fixation of Chopart or Lisfranc fracture dislocations and tarsometatarsal fractures. However, calcaneal fractures cannot be reached via this approach and require other techniques. After the recognition of the calcaneal compartment, surgeons realized that the dorsal approach does not allow its decompression of this compartment [46]. If two dorsal incisions are used, we recommend performing the medial incision medial to the second metatarsal and the lateral incision lateral to the fourth metatarsal. To minimize the risk of skin bridge necrosis, these two incisions are made through the subcutaneous tissue to preserve perfusion. Additionally, superficial veins and nerves should be preserved. The dorsal fascia of each interosseous compartment is opened longitudinally. In the first interosseous compartment, the muscle is stripped from the medial fascia and retracted medially. The white fascia of the adductor compartment becomes visible and is carefully split. All wounds are left open to obtain secondary healing, skin graft, or vacuum-assisted closure (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Anatomical section view of the forefoot. The dorsal approach uses one or two longitudinal incisions. It facilitates access to the interosseus and adductor compartments. MT = metatarsal; M = medial compartment; A = adductor compartment; S = superficial compartment; L = lateral compartment.

Medial Plantar Approach

The necessity for calcaneal compartment decompression required a medial plantar approach in combination to the dorsal approach to decompress all foot compartments [7, 65]. The medial incision begins at the origin of the abductor hallucis (approximately 3 cm above the plantar surface and 4 cm from the posterior aspect of the heel) and is extended parallel to the plantar surface for 6 cm [46]. Following the incision, the fascia of the abductor hallucis muscle is visible and should be split in line with the dermal incision. After release of the medial compartment, the abductor hallucis muscle is detached from the fascia and retracted superiorly. The visible white fascia is the barrier to the calcaneal compartment and should be split longitudinally. Although splitting of the muscle is described in the literature [30], other authors favor a blunt dissection since it is more tissue preserving [75]. After reflecting the medial compartment superiorly, the superficial compartment is identified lateral to the medial compartment. A longitudinal incision of the fascia releases this compartment. The flexor digitorum brevis is retracted inferiorly and the medial fascia of the lateral compartment can be identified. This compartment is decompressed when the abductor digiti quinti and flexor digiti minimi are visible and can be identified. All wounds are left open to obtain secondary healing, skin graft, or vacuum-assisted closure (Figs. 3, 4).

Fig. 3.

Anatomical section view of the forefoot. Compartments accessible through the medial plantar approach. MT = metatarsal; M = medial compartment; A = adductor compartment; S = superficial compartment; L = lateral compartment.

Fig. 4.

Anatomical section view of the hindfoot. The plantar medial approach allows access to the calcaneal compartment. It uses one or two longitudinal incisions. M = medial compartment; C = calcaneal compartment; S = superficial compartment; L = lateral compartment.

In a recent cadaver study, the authors found only three compartments extending from the hindfoot to the midfoot. The authors suggest that fasciotomy of the hindfoot would be a sufficient treatment for compartment syndrome of the foot [44]. However, we recommend that the dermatofasciotomy should be performed including the forefoot to verify the release of the forefoot compartments.

Lateral Approach

In 1982, Echtermeyer et al. described a lateral approach [20]. The incision begins at the lateral malleolus and is extended to the forefoot between the fourth and fifth metatarsals. Since the firm skin, especially of younger patients, may compress the leg and thereby diminish the therapeutic effect of fasciotomy, a primary wound closure is not recommended although studies are not available so far [25]. Temporary wound closure may either be carried out using a vacuum dressing system or artificial skin. A definitive closure is possible after the swelling has subsided. In patients with persistent swelling, a mesh graft must be used.

Untreated compartment syndrome with ischemia of the lower leg or foot may lead to muscle contractures resulting in deformity and functional impairment [78]. Additionally, nerve damage may cause weakness or paralysis of the affected muscles and a dysfunctional painful extremity. While nonoperative treatment aims at preserving joint mobility, salvaging of late sequelae of compartment syndrome may require nerve decompression and surgical correction of deformities (soft tissue releases, tendon transfers, realignment osteotomies, joint fusions) [78].

Outcome

Although the etiology, pathophysiology, and treatment of compartment syndrome are well-described, little is known about the long-term outcomes. Since compartment syndrome of the lower leg and foot has a low incidence (1.2% after closed tibia fractures, 6% after open tibia fracture) [17], studies with a high number of patients are not available. A long observation period with various surgeons and different surgical techniques does not allow direct comparison of published outcomes. To the best of our knowledge, only one study investigated quality of life after compartment syndrome of the lower leg using the EQ-5D [29]. Two studies investigated patients with compartment syndrome of the lower leg but did not use validated outcome measures such as the SF-36 questionnaire [25, 35].

Injuries below the knee reportedly determine the outcome in patients suffering severe trauma [97]. Hence, along with other injuries of the lower limb, compartment syndrome plays a key role in the rehabilitation of affected patients. Although surgical decompression is an emergency procedure with an absolute indication to prevent further damage and long-term impairment, several severe long-term sequelae of fasciotomies have been reported. Besides cosmetic issues, altered sensation and dry, scaly skin with pruritus were frequent clinical findings [22].

Lower Leg

In a study of 30 cases, patients with a compartment syndrome of the lower leg reported more problems on the dimensions of EQ-5D than the control group at least 12 months after treatment, although the overall self-rated health was not statistically different [29]. Additionally, the authors reported that patients with faster closure times of the wound had better self-rated health status than patients with longer wound closure times [29].

In one followup study of outcomes of 26 patients with traumatic compartment syndrome of the lower leg, 15.4% complained about pain at rest and 26.9% reported pain with exertion 1 to 7 years after trauma [25]. In this population, more than 50% of patients had reduced range of motion and a reduced sensation, while in another study only 15% were seen in patients with compartment syndrome due to various causes [35]. Infections due to fasciotomy are described in up to 38% of patients [40]. In patients in whom a skin graft was performed for wound closure that study demonstrated fewer infections. Additionally, patients with a trauma-induced compartment syndrome and skin grafts reported less frequent pain and discomfort [29, 40]. Patients with traumatic compartment syndrome have reduced isokinetic strength and work [25]. In one report the presence of associated injuries did not seem to influence the long-term result following traumatic compartment syndrome of the lower leg regarding motor or sensory dysfunction and loss of muscle strength [25]. To the best of our knowledge, there is no information available regarding the resumption of work.

After surgical decompression of chronic exertional compartment syndrome of the lower leg de Fijter et al. reported unlimited exercise in 96% after a mean followup of more than 5 years [16]. In a case series of 11 athletes with chronic exertional compartment syndrome of the lower leg, all patients reached the preinjury level of sports activity at a 2-year followup [61]. In contrast, in another study only 87% reported reduced symptoms after surgical release of chronic exertional compartment syndrome of the lower leg [92]. An early study of 28 patients reported better results in patients in which the anterior compartment is affected as compared to the deep posterior compartment [80].

Foot

Most reports about the outcome following foot compartment syndromes are case reports. In a series of 14 patients, Myerson [69] described four patients returning to work and resuming preoperative exercise activities. While six patients had occasional symptoms with daily activities or mild discomfort with normal shoe wear, three patients developed contractures with claw toes. In no patient was an amputation necessary [69]. We found 15 of 33 patients had a compartment syndrome associated with other severe injuries (unpublished data). The mean ISS was 19.1, and the mean NISS was 22.7 points. Eight of 33 patients had impaired range of motion of the toes or ankle, while three patients had a free flap resulting in decreased motor function. Paresthesia and numbness of the scars or distal to the affected compartments were common long-term sequelae in eight patients.

Discussion

Compartment syndromes of the lower leg or foot are severe complications and require immediate treatment. Unrecognized compartment syndrome causes irreversible damage to the affected region. Aim of this review was not only to evaluate the anatomy, pathogenesis, and diagnosis, but also the outcome of compartment syndrome of the lower leg and foot.

Our search suggests the literature is quite limited. First, using PubMed we identified no prospective randomized trials comparing alternate approaches. Second, we could only identify one study using validated outcome measures following compartment syndrome of the lower leg [29]. Thus, further studies are necessary to describe long-term outcome in which data of validated outcome measures should be performed. Third, since few studies deal with anatomical structures [33, 46, 68], the number of foot compartments stated in the literature is still debatable and ranges from three to 10 compartments [33, 42, 74]. Fourth, the literature on foot compartment syndrome are limited to small case series with a maximum of 14 patients [69]. Additionally, one report described foot compartment syndrome in seven children [86]. Studies regarding outcome after trauma-induced compartment syndrome of the lower leg did not include more than 40 patients [25, 29]. The small incidence [17, 39, 53] required a long observation period up to 6 years [35] with different surgeons and different surgical techniques. Thus, direct comparison of published outcomes is nearly impossible.

While the pathophysiology of the compartment syndrome is well-described [8, 26, 47, 64], it remains unclear when irreversible damage occurs. A study from 1991 suggested an ischemic time of 5 to 6 hours [14], while more recent investigations reported muscle necrosis after less than 3 hours in an animal model [91]. Thus, information provided in the literature is inconsistent and further studies are necessary to clear this controversy.

Although the clinical signs are well-described [90], the most important step in diagnosing a compartment syndrome is the clinician’s awareness. In patients at risk for a compartment syndrome, repeated examinations are required to allow for this dynamic process. The clinician must be aware that pain as clinical sign of compartment syndrome may be masked in patients with reduced vigilance or previously treated with analgesics. Although the literature lacks recommendations regarding the intervals in which serial examinations should be performed we recommend serial examinations in patients at risk at least every hour since irreversible damage was described after less than 3 hours [91]. In patients with uncertain signs, invasive measurement of intracompartmental pressure is available [28].

However, there are different recommendations as to which differential pressure should be used as a clear indication for a fasciotomy [53, 72, 95]. In this regard, the surgeon should be aware of differences in diastolic blood pressure due to anesthetics during intraoperative measurement as compared to awake patients [58].

The treatment of a compartment syndrome consists of dermatofasciotomy. The literature describes splitting of the fascia of the lower leg via one lateral approach or combined anterolateral and posteromedial incisions. We could not identify a study comparing both methods and hence the literature lacks recommendations how a compartment syndrome of the lower leg should be relieved. Recommendations for surgical treatment of foot compartment syndrome are even more controversial. Although multiple approaches are described [7, 19, 62, 65, 68] the literature lacks studies comparing different approaches for surgical treatment of foot compartment syndrome as well.

In conclusion, compartment syndrome of the lower leg and foot is a rare but serious complication of which a surgeon should be aware. Although an immediate fasciotomy is the undisputed treatment for patients with compartment syndrome, the literature lacks guidelines for patients at risk. The fasciotomy of the lower leg can be performed via one or two incisions. The approaches for dermatofasciotomy of the foot should be planned on the basis of associated injuries.

Footnotes

Each author certifies that he or she has no commercial associations (eg, consultancies, stock ownership, equity interest, patent/licensing arrangements, etc) that might pose a conflict of interest in connection with the submitted article.

This work was performed at Hannover Medical School, Hannover, Germany.

References

- 1.Al Dadah OQ, Darrah C, Cooper A, Donell ST, Patel AD. Continuous compartment pressure monitoring vs. clinical monitoring in tibial diaphyseal fractures. Injury. 2008;39:1204–1209. doi: 10.1016/j.injury.2008.03.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Anglen J, Banovetz J. Compartment syndrome in the well leg resulting from fracture-table positioning. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1994;239–242. [PubMed]

- 3.Askins G, Finley R, Parenti J, Bush D, Brotman S. High-energy roller injuries to the upper extremity. J Trauma. 1986;26:1127–1131. doi: 10.1097/00005373-198612000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Batra S, McMurtrie A, Sinha AK, Griffin S. Recurrent compartment syndrome of foot following calcaneal fracture. Foot Ankle Surg. 2007;13:154–156. doi: 10.1016/j.fas.2007.01.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Benejam CE, Potaczek SG. Unusual presentation of Lisfranc fracture dislocation associated with high-velocity sledding injury: a case report and review of the literature. J Med Case Reports. 2008;2:266. doi: 10.1186/1752-1947-2-266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bong MR, Polatsch DB, Jazrawi LM, Rokito AS. Chronic exertional compartment syndrome: diagnosis and management. Bull Hosp Jt Dis. 2005;62:77–84. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bonutti PM, Bell GR. Compartment syndrome of the foot. A case report. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1986;68:1449–1451. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Burton AC. On the physical equilibrium of small blood vessels. Am J Physiol. 1951;164:319–329. doi: 10.1152/ajplegacy.1951.164.2.319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Busch T, Sirbu H, Zenker D, Dalichau H. Vascular complications related to intraaortic balloon counterpulsation: An analysis of ten years experience. Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 1997;45:55–59. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-1013687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cara JA, Narvaez A, Bertrand ML, Guerado E. Acute atraumatic compartment syndrome in the leg. Int Orthop. 1999;23:61–62. doi: 10.1007/s002640050306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cascio BM, Wilckens JH, Ain MC, Toulson C, Frassica FJ. Documentation of acute compartment syndrome at an academic health-care center. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2005;87:346–350. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.D.02007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cooper GG. A Method of Single-Incision, 4 Compartment Fasciotomy of the Leg. Eur J Vasc Surg. 1992;6:659–661. doi: 10.1016/S0950-821X(05)80846-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Court-Brown CM. Reamed intramedullary tibial nailing: an overview and analysis of 1106 cases. J Orthop Trauma. 2004;18:96–101. doi: 10.1097/00005131-200402000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Day LJ, Bovill EG, Trafton PG. Orthopedics. In: Way LW. Current Surgical Diagnosis and Treatment, 9th ed. East Norwalk, CT: Appleton and Lange; 1991:1038.

- 15.Dayton P, Goldman FD, Barton E. Compartment pressure in the foot. Analysis of normal values and measurement technique. J Am Podiatr Med Assoc. 1990;80:521–525. doi: 10.7547/87507315-80-10-521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fijter WM, Scheltinga MR, Luiting MG. Minimally invasive fasciotomy in chronic exertional compartment syndrome and fascial hernias of the anterior lower leg: short- and long-term results. Mil Med. 2006;171:399–403. doi: 10.7205/milmed.171.5.399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.DeLee JC, Stiehl JB. Open tibia fracture with compartment syndrome. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1981;175–184. [PubMed]

- 18.Due J, Nordstrand K. A simple technique for subcutaneous fasciotomy. Acta Chirurgica Scandinavica. 1987;153:521–522. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Echtermeyer V. Compartment syndrome. Principles of therapy [in German] Unfallchirurg. 1991;94:225–230. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Echtermeyer V, Muhr G, Oestern HJ, Tscherne H. Surgical treatment of compartmental syndromes (author’s transl) [in German] Unfallheilkunde. 1982;85:144–152. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Finkelstein JA, Hunter GA, Hu RW. Lower limb compartment syndrome: course after delayed fasciotomy. J Trauma. 1996;40:342–344. doi: 10.1097/00005373-199603000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fitzgerald AM, Gaston P, Wilson Y, Quaba A, McQueen MM. Long-term sequelae of fasciotomy wounds. Br J Plast Surg. 2000;53:690–693. doi: 10.1054/bjps.2000.3444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Friedrich JB, Shin AY. Management of forearm compartment syndrome. Hand Clin. 2007;23:245–254. doi: 10.1016/j.hcl.2007.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Frink M, Geerling J, Hildebrand F, Knobloch K, Zech S, Droste P, Krettek C, Richter M. Etiology, treatment and long-term results of isolated midfoot fractures. Foot Ankle Surg. 2006;12:121–125. doi: 10.1016/j.fas.2006.02.004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Frink M, Klaus AK, Kuther G, Probst C, Gosling T, Kobbe P, Hildebrand F, Richter M, Giannoudis PV, Krettek C, Pape HC. Long term results of compartment syndrome of the lower limb in polytraumatised patients. Injury. 2007;38:607–613. doi: 10.1016/j.injury.2006.12.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fuhrman FA, Crismon JM. Early changes in distribution of sodium, potassium and water in rabbit muscles following release of tourniquets. Am J Physiol. 1951;166:424–432. doi: 10.1152/ajplegacy.1951.166.2.424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fulkerson E, Razi A, Tejwani N. Review: acute compartment syndrome of the foot. Foot Ankle Int. 2003;24:180–187. doi: 10.1177/107110070302400214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gerngross H, Rosenheimer M, Becker HP. Invasive measurement of compartment pressure based on piezo-resistance principles [in German] Chirurg. 1991;62:832–833. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Giannoudis PV, Nicolopoulos C, Dinopoulos H, Ng A, Adedapo S, Kind P. The impact of lower leg compartment syndrome on health related quality of life. Injury. 2002;33:117–121. doi: 10.1016/S0020-1383(01)00073-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Goldman FD, Dayton PD, Hanson CJ. Compartment syndrome of the foot. J Foot Surg. 1990;29:37–43. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Griffiths DL. The management of acute circulatory failure in an injured limb. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1948;30:280–298. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Grodinsky M. A study of the fascial spaces of the foot and their bearing of infection. Surg Gynecol Obstet. 1929;49:737–751. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Guyton GP, Shearman CM, Saltzman CL. The compartments of the foot revisited. Rethinking the validity of cadaver infusion experiments. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2001;83:245–249. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.83B2.10504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Harris IA, Kadir A, Donald G. Continuous compartment pressure monitoring for tibia fractures: does it influence outcome? J Trauma. 2006;60:1330–1335. doi: 10.1097/01.ta.0000196001.03681.c3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Heemskerk J, Kitslaar P. Acute compartment syndrome of the lower leg: Retrospective study on prevalence, technique, and outcome of fasciotomies. World J Surg. 2003;27:744–747. doi: 10.1007/s00268-003-6691-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Heppenstall RB, Scott R, Sapega A, Park YS, Chance B. A comparative study of the tolerance of skeletal muscle to ischemia. Tourniquet application compared with acute compartment syndrome. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1986;68:820–828. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hildebrand O. Die Lehre von den ischämischen Muskellähmungen und Kontrakturen. Samml Klin Vorträge. 1906;122:437. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ho GH, Laarhoven CJ, Ottow RT. Compartment syndrome in both lower legs after prolonged surgery in the lithotomy position [in Dutch] Ned Tijdschr Geneeskd. 1998;142:1210–1212. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Jeffers RF, Tan HB, Nicolopoulos C, Kamath R, Giannoudis PV. Prevalence and patterns of foot injuries following motorcycle trauma. J Orthop Trauma. 2004;18:87–91. doi: 10.1097/00005131-200402000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Johnson SB, Weaver FA, Yellin AE, Kelly R, Bauer M. Clinical results of decompressive dermotomy-fasciotomy. Am J Surg. 1992;164:286–290. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9610(05)81089-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Jowett A, Birks C, Blackney M. Chronic exertional compartment syndrome in the medial compartment of the foot. Foot Ankle Int. 2008;29:838–841. doi: 10.3113/FAI.2008.0838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kamel R, Sakla FB. Anatomical compartments of the sole of the human foot. Anat Rec. 1961;140:57–60. doi: 10.1002/ar.1091400109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kunkel MG, Lynn RB. The anterior tibial compartment syndrome. Can J Surg. 1958;1:212–217. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ling ZX, Kumar VP. The myofascial compartments of the foot: a cadaver study. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2008;90:1114–1118. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.90B8.20836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lokiec F, Siev-Ner I, Pritsch M. Chronic compartment syndrome of both feet. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1991;73:178–179. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.73B1.1991764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Manoli A, Weber TG. Fasciotomy of the foot: an anatomical study with special reference to release of the calcaneal compartment. Foot Ankle. 1990;10:267–275. doi: 10.1177/107110079001000505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Matsen FA, III. Compartmental syndrome. An unified concept. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1975;8–14. [PubMed]

- 48.Matsen FA, III, Winquist RA, Krugmire RB., Jr Diagnosis and management of compartmental syndromes. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1980;62:286–291. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Matsuoka T, Yoshioka T, Tanaka H, Ninomiya N, Oda J, Sugimoto H, Yokota J. Long-term physical outcome of patients who suffered crush syndrome after the 1995 Hanshin-Awaji earthquake: prognostic indicators in retrospect. J Trauma. 2002;52:33–39. doi: 10.1097/00005373-200201000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Maurel B, Brilhault J, Martinez R, Lermusiaux P. Compartment syndrome with foot ischemia after inversion injury of the ankle. J Vasc Surg. 2007;46:369–371. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2007.03.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.McQueen MM, Christie J, Court-Brown CM. Compartment pressures after intramedullary nailing of the tibia. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1990;72:395–397. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.72B3.2341435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.McQueen MM, Christie J, Court-Brown CM. Acute compartment syndrome in tibial diaphyseal fractures. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1996;78:95–98. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.McQueen MM, Court-Brown CM. Compartment monitoring in tibial fractures. The pressure threshold for decompression. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1996;78:99–104. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.McQueen MM, Gaston P. Court-Brown. Acute compartment syndrome - Who is at risk? J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2000;82:200–203. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.82B2 .9799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.McQuillan WM, Nolan B. Ischaemia complicating injury. A report of thirty-seven cases. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1968;50:482–492. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Middleton DK, Johnson JE, Davies JF. Exertional compartment syndrome of bilateral feet: a case report. Foot Ankle Int. 1995;16:95–96. doi: 10.1177/107110079501600209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Mithofer K, Lhowe DW, Vrahas MS, Altman DT, Altman GT. Clinical spectrum of acute compartment syndrome of the thigh and its relation to associated injuries. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2004;223–229. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 58.Miyabe M, Sato S. The effect of head-down tilt position on arterial blood pressure after spinal anesthesia for cesarean delivery. Reg Anesth. 1997;22:239–242. doi: 10.1016/S1098-7339(06)80008-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Mollica MB. Chronic exertional compartment syndrome of the foot. A case report. J Am Podiatr Med Assoc. 1998;88:21–24. doi: 10.7547/87507315-88-1-21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Moses TA, Kreder KJ, Thrasher JB. Compartment syndrome: an unusual complication of the lithotomy position. Urology. 1994;43:746–747. doi: 10.1016/0090-4295(94)90204-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Mouhsine E, Garofalo R, Moretti B, Gremion G, Akiki A. Two minimal incision fasciotomy for chronic exertional compartment syndrome of the lower leg. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2006;14:193–197. doi: 10.1007/s00167-004-0613-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Mubarak S, Owen CA. Compartmental syndrome and its relation to the crush syndrome: A spectrum of disease. A review of 11 cases of prolonged limb compression. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1975;81–89. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 63.Muller GP, Masquelet AC. Chronic compartment syndrome of the foot. A case report [in French] Rev Chir Orthop Reparatrice Appar Mot. 1995;81:549–552. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Mustard WT, Simmons EH. Experimental arterial spasm in the lower extremities produced by traction. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1953;35:437–441. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.35B3.437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Myerson M. Acute compartment syndromes of the foot. Bull Hosp Jt Dis Orthop Inst. 1987;47:251–261. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Myerson M. Diagnosis and treatment of compartment syndrome of the foot. Orthopedics. 1990;13:711–717. doi: 10.3928/0147-7447-19900701-06. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Myerson M, Manoli A. Compartment syndromes of the foot after calcaneal fractures. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1993;142–150. [PubMed]

- 68.Myerson MS. Experimental decompression of the fascial compartments of the foot–the basis for fasciotomy in acute compartment syndromes. Foot Ankle. 1988;8:308–314. doi: 10.1177/107110078800800606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Myerson MS. Management of compartment syndromes of the foot. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1991;239–248. [PubMed]

- 70.Nassif JM, Gorczyca JT, Cole JK, Pugh KJ, Pienkowski D. Effect of acute reamed versus unreamed intramedullary nailing on compartment pressure when treating closed tibial shaft fractures: a randomized prospective study. J Orthop Trauma. 2000;14:554–558. doi: 10.1097/00005131-200011000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Ogunlusi JD, Oginni LM, Ikem IC. Normal leg compartment pressures in adult Nigerians using the Whitesides method. Iowa Orthop J. 2005;25:200–202. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Olson SA, Glasgow RR. Acute compartment syndrome in lower extremity musculoskeletal trauma. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2005;13:436–444. doi: 10.5435/00124635-200511000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Paaske WP, Bagl P, Lorentzen JE, Olgaard K. Plasma exchange after revascularization compartment syndrome with acute toxic nephropathy caused by rhabdomyolysis. J Vasc Surg. 1988;7:757–758. doi: 10.1067/mva.1988.avs0070757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Reach JS, Jr, Amrami KK, Felmlee JP, Stanley DW, Alcorn JM, Turner NS, Carmichael SW. Anatomic compartments of the foot: a 3-Tesla magnetic resonance imaging study. Clin Anat. 2007;20:201–208. doi: 10.1002/ca.20381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Richter J, Schulze W, Klaas A, Clasbrummel B, Muhr G. Compartment syndrome of the foot: an experimental approach to pressure measurement and release. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 2008;128:199–204. doi: 10.1007/s00402-007-0522-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Richter M, Wippermann B, Krettek C, Schratt HE, Hufner T, Therman H. Fractures and fracture dislocations of the midfoot: occurrence, causes and long-term results. Foot Ankle Int. 2001;22:392–398. doi: 10.1177/107110070102200506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Rorabeck CH. A practical approach to compartmental syndrome. Part III. Management. Instr Course Lect. 1983;32:102–113. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Santi MD, Botte MJ. Volkmann’s ischemic contracture of the foot and ankle: evaluation and treatment of established deformity. Foot Ankle Int. 1995;16:368–377. doi: 10.1177/107110079501600610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Schachtrupp A, Jansen M, Bertram P, Kuhlen R, Schumpelick V. Abdominal compartment syndrome: significance, diagnosis and treatment. Anaesthesist. 2006;55:660–667. doi: 10.1007/s00101-006-1019-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Schepsis AA, Martini D, Corbett M. Surgical management of exertional compartment syndrome of the lower leg. Long-term followup. Am J Sports Med. 1993;21:811–817. doi: 10.1177/036354659302100609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Schwartz JT, Jr, Brumback RJ, Lakatos R, Poka A, Bathon GH, Burgess AR. Acute compartment syndrome of the thigh. A spectrum of injury. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1989;71:392–400. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Seiler JG, III, Womack S, L’Aune WR, Whitesides TE, Hutton WC. Intracompartmental pressure measurements in the normal forearm. J Orthop Trauma. 1993;7:414–416. doi: 10.1097/00005131-199310000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Seiler R, Guziec G. Chronic compartment syndrome of the feet. A case report. J Am Podiatr Med Assoc. 1994;84:91–94. doi: 10.7547/87507315-84-2-91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Shah SN, Miller BS, Kuhn JE. Chronic exertional compartment syndrome. Am J Orthop. 2004;33:335–341. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Sharma H, Rana B, Naik M. Bipedal compartment syndrome folowing bilateral intra-articular calcaneal fractures. Foot Ankle Surg. 2004;10:93–96. doi: 10.1016/j.fas.2004.01.004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Silas SI, Herzenberg JE, Myerson MS, Sponseller PD. Compartment syndrome of the foot in children. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1995;77:356–361. doi: 10.2106/00004623-199503000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Starosta D, Sacchetti AD, Sharkey P. Calcaneal fracture with compartment syndrome of the foot. Ann Emerg Med. 1988;17:856–858. doi: 10.1016/S0196-0644(88)80572-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Sterk J, Schierlinger M, Gerngross H, Willy C. Compartment pressure measurement of acute compartment syndrome - results of a survey in Germany to measurement technique and pressure [in German] Unfallchirurg. 2001;104:119–126. doi: 10.1007/s001130050701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Tzortziou V, Maffulli N, Padhiar N. Diagnosis and management of chronic exertional compartment syndrome (CECS) in the United Kingdom. Clin J Sport Med. 2006;16:209–213. doi: 10.1097/00042752-200605000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Ulmer T. The clinical diagnosis of compartment syndrome of the lower leg: are clinical findings predictive of the disorder? J Orthop Trauma. 2002;16:572–577. doi: 10.1097/00005131-200209000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Vaillancourt C, Shrier I, Vandal A, Falk M, Rossignol M, Vernec A, Somogyi D. Acute compartment syndrome: How long before muscle necrosis occurs? CJEM. 2004;6:147–154. doi: 10.1017/s1481803500006837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Verleisdonk EJ, Schmitz RF, Werken C. Long-term results of fasciotomy of the anterior compartment in patients with exercise-induced pain in the lower leg. Int J Sports Med. 2004;25:224–229. doi: 10.1055/s-2003-45255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Volkmann R. Die ischämischen Muskellähmungen und Kontracturen. Zentralbl Chir. 1881;8:801–803. [Google Scholar]

- 94.Whitesides TE, Jr, Haney TC, Harada H, Holmes HE, Morimoto K. A simple method for tissue pressure determination. Arch Surg. 1975;110:1311–1313. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.1975.01360170051006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Willy C, Sterk J, Völker HU, Sommer C, Weber F, Trentz O, Gerngross H. Acute compartment syndrome. Results of a clinical investigation of pressure and time thresholds for emergency fasciotomy [in German] Unfallchirurg. 2001;104:381–391. doi: 10.1007/s001130050747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Yamaguchi S, Viegas SF. Causes of upper extremity compartment syndrome. Hand Clin. 1998;14:365–370. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Zelle BA, Brown SR, Panzica M, Lohse R, Sittaro NA, Krettek C, Pape HC. The impact of injuries below the knee joint on the long-term functional outcome following polytrauma. Injury. 2005;36:169–177. doi: 10.1016/j.injury.2004.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]