Abstract

We examined gender differences in age of onset, clinical course, and heritability of alcohol dependence in 2524 adults participating in the University of California San Francisco (UCSF) family study of alcoholism. Men were significantly more likely than women to have initiated regular drinking during adolescence. Onset of regular drinking was not found to be heritable but was found to be significantly associated with a shorter time to onset of alcohol dependence. A high degree of similarity in the sequence of alcohol-related life events was found between men and women, however, men experienced alcohol dependence symptoms at a younger age and women had a more rapid clinical course. Women were found to have a higher heritability estimate for alcohol dependence (h2 =0.46) than men (h2 =0.32). These findings suggest that environmental factors influencing the initiation of regular drinking rather than genetic factors associated with dependence may in part underlie some of the gender differences seen in the prevalence of alcohol dependence in this population.

Keywords: heritability, alcohol dependence, gender, survival analyses

INTRODUCTION

National epidemiological samples have generally demonstrated that men are more likely to drink than women1 and that alcohol dependence occurs less frequently among women than men2–3. What is not clear is whether the differences in alcohol dependence rates between men and women are a direct reflection of customary differences in drinking practices that may be environmentally driven or whether there are sex specific phenotypes that differ in genetic risk for alcohol dependence.

A number of theories posit that there may be subtypes of alcohol use disorders that may be gender specific4. The best known of these are Cloninger’s Types I and II 5 and Babor’s Types A and B6. Cloninger’s Type II and Babor’s Type B are similar in having earlier onset of drinking problems, more antisocial and other psychiatric co-morbidity, and a more severe course, as opposed to Type I and Type A. Evidence suggests that type II/B might be more heritable than type I/A5, raising the possibility that Type II/B is more genetically based and Type I/A more environmentally based4. It has been further hypothesized that type I/A alcoholism is more common in women and type II/B more common in men. Sociopathy phenotypes, such as the presence of antisocial personality disorder and/or conduct disorder (ASPD/CD), are twice as common in men as compared to women and are highly significantly co-morbid with alcohol dependence. However, they represent a very small sample of the aggregate of alcohol dependence in the general population2, 7, 8. This suggests that while ASPD/CD may be strongly associated with alcohol dependence and being male, other risk factors most likely explain most of the genetic and environmental variance for alcohol dependence, particularly in women. In this light, Hill9 has proposed a type III alcoholism that is not related to paternal sociopathy but still represents a severe form of the disorder.

Additional data on gender differences in alcohol dependence are provided by behavioral genetics studies in twins. If alcohol dependence is more heritable in males then twin correlations for alcohol dependence should be higher in male twins than in female twins. Early studies using twin and adoption strategies have found evidence of moderate to strong genetic influences (heritability estimate of 40–60%) on alcoholism among men10–15; although, recent studies do not provide evidence for higher heritability for male early onset alcoholism or for alcoholism with comorbid ASPD16. Early studies on the role of genetic influences on alcoholism among women produced results that were less clear. Some early studies found that alcoholism in women to be less influenced by genetic factors than men14, 15, 17. However, others obtained heritability estimates for women comparable to those in men13, 18. One problem with some studies is that they lacked the power to detect sex differences because relatively few affected women were ascertained for study. In one large study, 5091 male and 4168 female twins were assessed for sex differences in the sources of genetic liability to alcohol abuse and dependence19. In that study, the proportion of population variation in liability to alcohol use disorders attributed to genetic factors was found to be equally high for men (51–66%) and women (55–66%).

While data on female alcoholics in large population samples is now becoming more frequently available9, 20–22, replications of findings from large scale behavioral genetics studies with reliable assessment instruments are still needed. Such studies can also provide valuable data on gender differences in alcohol-related symptomatology, age of onset, as well as heritability. The present report is part of a larger, nationwide, behavioral genetics study, the University of California San Francisco (UCSF) Family Alcoholism Study. Community recruitment was used in this study to avoid selecting a sample solely limited to the subset of alcoholics who present for formal treatment. The specific aims of the present report are to evaluate early drinking and the clinical course of alcohol dependence in this data set in order to elucidate gender differences in: (1) age at regular drinking and its association with alcohol dependence; (2) the clinical course of alcoholism in this population as well as to compare the clinical data in the UCSF family study to data from the Collaborative Study for the Genetics of Alcoholism (COGA); and (3) the heritability of age at first regular drinking and alcohol dependence.

METHODS

Participants

The UCSF family study is a behavioral genetics study that recruited probands with alcohol dependence and the relatives of those probands, nationwide. In addition, a community sample was ascertained in order to estimate population means and standard deviations for genetic analyses. Participants were recruited through the use of semi-targeted direct mail, a web site, press releases, advertisements and from alumni of treatment centers, across the nation. Thirty-three percent of the probands were recruited from the general population random mailings, 32% from community organizations, 18% from treatment program alumni, and 17 % from other sources. Probands reporting serious drug dependence (defined as use of stimulants, cocaine, or opiates daily for more than 3 months or weekly for more than 6 months), current or past diagnosis of schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, or other psychiatric illness involving psychotic symptoms, a life-threatening illness, or an inability to speak and read English were excluded. The details of recruitment of all participants and other methodology for assessing participants, inter-rater reliability and participant demographics have been previously published23, 24. This is the first report describing the clinical data for alcohol dependence derived from the study.

Measures

A remote data collection procedure was developed allowing for blood samples and other questionnaires to be returned by mail, and structured diagnostic interviews to be conducted by telephone, making nationwide data collection possible. Potential participants first had the study explained and gave written informed consent. A modified version of the Semi-Structured Assessment for the Genetics of Alcoholism (SSAGA)25, was used to collect demographic, medical, psychiatric, alcohol, nicotine, and other drug use history. Modifications of the SSAGA for the present study included changes in diagnostic criteria and items to approximate DSM-IV and DSM-III-R criteria. Only the sections of the SSAGA relevant to substance abuse, demographics and medical history were utilized. Twenty percent of those enrolled did not complete all study requirements.

Data Analyses

The data analyses were based on the specific aims; the first aim of which was to determine the age of onset and prevalence of regular drinking (defined as: how old were you when you started drinking alcohol regularly, not necessarily daily, but on a regular basis) in men and women, as well as the probability of transition to alcohol dependence using survival analyses. The Kaplan-Meier method was used to estimate survival time using a time-to-event model (time interval from first regular drinking to dependence) in the presence of censored cases Therefore the age of onset and prevalence of regular drinking was used as the initial variable to: (1) determine the prevalence in this population; (2) determine its association with alcohol dependence; and (3) to estimate the duration of time elapsed to regular use and between regular use and the onset of dependence using survival analyses.

The second aim of the study was: (1) to investigate gender differences in the clinical course of alcoholism in UCSF family study participants, using 36 alcohol-related life events derived from the SSAGA, and (2) to determine whether the clinical course of alcoholism follows the same patterns previously described in the literature for COGA participants. Comparative analysis of the age at first occurrence of the sequence of 36 alcohol-related life events was determined in those participants with alcohol dependence. The present study used the same procedures as Schuckit and colleagues22, 26, 27 and Ehlers and colleagues28 to evaluate the course of alcoholism in this population.

The comparative analysis of the age at first occurrence of the sequence of alcohol-related life events between the alcohol-dependent subjects that were male vs. female was performed using Spearman’s rank correlation (rs). For these analyses each symptom is assigned a number based on the order of its appearance in time for all 36 symptoms for each gender and the Spearman rank correlation was computed relating order of appearance by gender. The same analysis was also performed to compare the total sample of alcoholics in the UCSF family study to a sample of alcohol-dependent patients from the COGA study. Because the COGA study uses a DSM-III-R plus Feighner criteria to make a diagnosis of alcohol dependence, the UCSF study data was compared to COGA first using UCSF participants that met DSM-IV criteria, and then a second confirmatory analysis with UCSF participants that met DSM-III-R criteria. An analysis of how many individuals endorsed individual items and whether they differed based on gender, or whether they were in the UCSF Family Study vs. COGA Study was evaluated using the Chi-Square test. The analyses of whether the age of first occurrence of each of the items differed based on: gender or UCSF vs. COGA was evaluated using t-tests. Significance for these analyses was set at p < 0.001, (Bonferroni correction).

The third aim of the study was to determine the heritability of DSM-IV alcohol dependence, and age of onset of regular drinking using a family genetics design. The total additive genetic heritability (h2) were estimated using SOLAR v 2.0.4 29, 30. SOLAR estimates heritability by partitioning the trait relative pair covariance into additive genetic and environmental contributions while correcting for any covariates included in the model. The discrete trait (alcohol dependence) was modeled with a liability threshold model. When overall heritability was found to be significant separate heritability for men and women were obtained. Participant's age at the time of evaluation and sex were evaluated as potential covariates and retained if they accounted for at least 5% of the total variance. Rather than allowing SOLAR to estimate means during the model-fitting procedure using the available sample data, means were constrained to the population mean (i.e., 15% for the overall analyses, 16% for males and 15% for females in the gender-specific analyses) to correct for ascertainment bias when estimating h2. These analyses have been described previously28, 31, 32.

RESULTS

Demographics

The demographic characteristics of this population have been presented previously24. In brief, the UCSF family sample had a mean age of 48.4 ± 13.4 years, a mean educational level of 14.4 ± 2.9 years, and an annual income of $57,356 ± $54,656. Racial distribution was: 92% Caucasian, 3% each African American and Hispanic, and 1% each Native American and Other. Fifty-four percent were married. Probands were 58% female, with 97% of probands meeting lifetime criteria for alcohol dependence, whereas, 38% of the relatives of probands were found to be alcohol dependent. Prevalence of alcohol and drug dependence in relatives in the UCSF family study was similar to the COGA sample33, although the UCSF sample had a slightly higher mean age, education, and socioeconomic status34. The UCSF random sample had similar demographic characteristics to the Family Study sample with 15% having a lifetime history of DSM-IV alcohol dependence.

Effect of age at first regular drinking on the development of alcohol dependence

Two thousand five hundred and twenty-four participants (1557 women, 967 men) had valid data that were used in the present analyses. Of those individuals, 1333 participants (796 women, 537 men) had a lifetime diagnosis of DSM-IV alcohol dependence. The mean age of first meeting criteria for DSM-IV alcohol dependence was 27.53 ± 9.50 (S.D.). Ninety percent of the sample reported regular drinking with equal proportions of men and women in the sample (1438 women, 900 men). Survival analyses revealed that survival to regular drinking was shorter in men than women (median survival estimate: women=19 ± 0.134; men=18 ± 0.092) (Mantel-Cox chi-Square = 25.63, df=1, p<0.0001).

The probability of having a lifetime alcohol dependence diagnosis was found to be significantly associated with the age at which a person reported first drinking regularly. Table 1 presents data demonstrating that those individuals who developed regular drinking at younger ages were significantly (p<0.001) more likely to become alcohol dependent than those who chose to begin regular drinking at later ages. A significantly higher proportion of the population of men than women in this sample reported drinking regularly between the ages of 19 and 35 years (p<0.001).

Table 1.

Age Onset of Regular Drinking and Alcohol Dependence

| Age onset of Regular Drinking |

No Alcohol Dependence (n) |

Alcohol Dependence (n) |

Alcohol Dependence (%) |

Chi-Square p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| <13 | 14 | 45 | 76 | 0.001 |

| <15 | 66 | 164 | 71 | <0.001 |

| <17 | 202 | 436 | 68 | <0.001 |

| <19 | 472 | 804 | 63 | <0.001 |

| <21 | 643 | 958 | 60 | <0.001 |

| <25 | 843 | 1121 | 57 | <0.001 |

| <30 | 962 | 1209 | 56 | 0.001 |

| <35 | 977 | 1221 | 55 | 0.002 |

| <40 | 995 | 1240 | 55 | <0.001 |

This table presents the number of participants who became alcohol dependent or did not based on the age when that participant first began drinking regularly. Significant differences in the proportion of participants who became alcohol dependent based on age at first drinking regularly are determined by Chi-square and p values are presented in the final column.

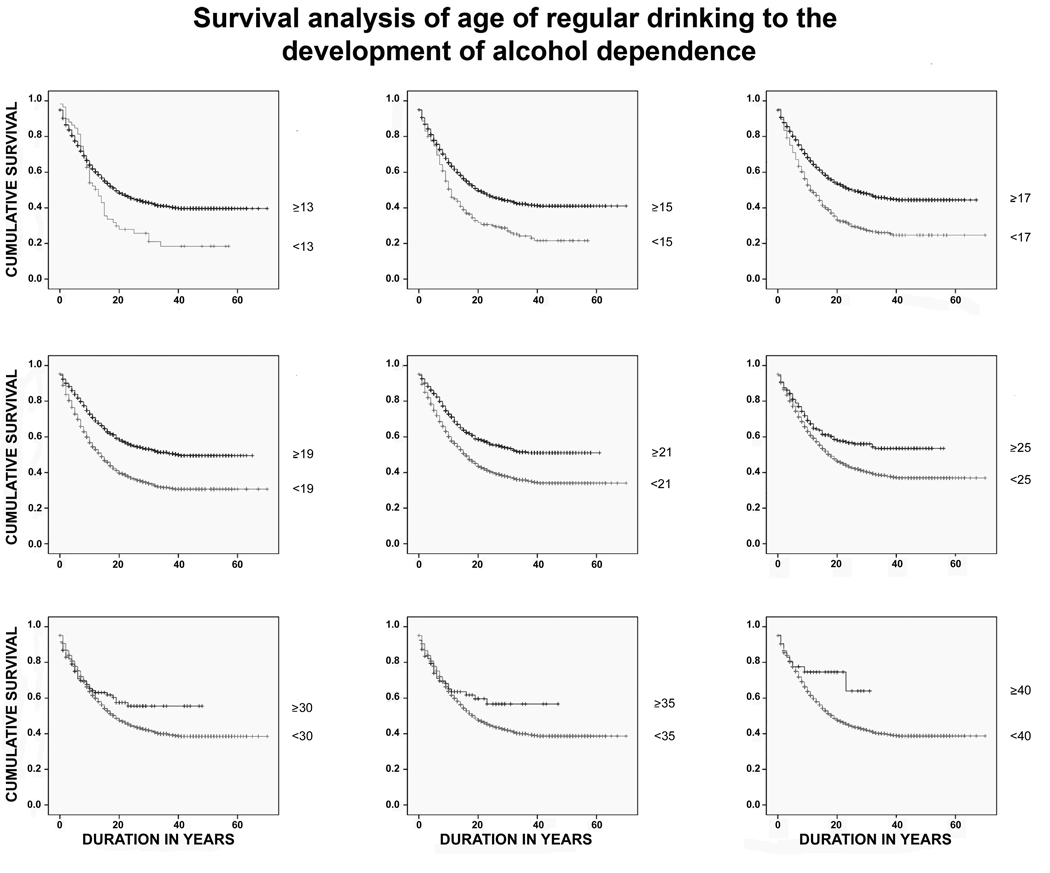

Table 2 and figure 1 present data from the survival analyses which includes estimates of the mean survival time (years) from age at onset of regular drinking to meeting criteria for DSM-IV alcohol dependence. Regular drinking at an early age had a significant (p<0.001) impact on the survival duration to the development of alcohol dependence. Having started regular drinking at 13 or younger was found to be associated with a mean survival time to alcohol dependence of 20.2 ± 1.7 years as opposed to 32.4 ± 1.4 years for individuals who did not develop regular drinking until after the age of 25. Survival time was also not different based on gender (Chi Square = 1.827, df=1, p<0.176).

Table 2.

Survival Analysis from Regular Drinking to Alcohol Dependence

| Age | Number Cases | Number Censored |

Number Alcohol Dependent |

Survival time Mean ± SE |

Log rank, significance |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| < 13 vs. ≥ 13 |

59 2218 |

14 1012 |

45 1206 |

20.2 ± 2.6 34.1 ± 0.7 |

7.17, p = 0.007 |

| < 15 vs. ≥ 15 |

230 2047 |

66 960 |

164 1087 |

20.7 ± 1.5 35.0 ± 0.7 |

29.59, p < 0.001 |

| < 17 vs. ≥ 17 |

638 1639 |

202 824 |

436 815 |

24.8 ± 1.2 35.9 ± 0.8 |

76.95, p < 0.001 |

| < 19 vs. ≥19 |

1276 1001 |

472 554 |

804 447 |

28.5 ± 0.9 38.1 ± 0.9 |

84.03, p < 0.001 |

| < 21 vs. ≥ 21 |

1601 676 |

643 383 |

958 293 |

30.8 ± 0.8 36.5 ± 1.1 |

46.18, p < 0.001 |

| < 25 vs. ≥ 25 |

1964 313 |

843 183 |

1121 130 |

32.7 ± 0.7 34.2 ± 1.4 |

15.38, p < 0.001 |

| < 30 vs. ≥ 30 |

2171 106 |

962 64 |

1209 42 |

33.6 ± 0.7 29.6 ± 2.2 |

2.25, p = 0.133 |

| < 35 vs. ≥ 35 |

2198 79 |

977 49 |

1221 30 |

33.6 ± 0.7 29.4 ± 2.5 |

1.86, p = 0.172 |

| < 40 vs. ≥ 40 |

2235 42 |

995 31 |

1240 11 |

33.7 ± 0.7 23.0 ± 2.0 |

4.03, p = 0.045 |

Survival analyses revealed that having a lifetime cannabis dependence diagnosis was significantly associated with the age at which a person reported first trying the drug. The Kaplan-Meier method was used to estimate survival time using a time to event model (time interval from first use to dependence) in the presence of censored cases (cases that do not have alcohol dependence but may have not passed through the age of risk). These survival curves were compared at each of the ages using the log-rank test of the null hypothesis of a single survival curve. Significant differences (p<0.001) were found for ages 15–25 yrs.

Figure 1.

The following graphs exhibit the cumulative survival rates between two groups of subjects: those who first began regular drinking under age (13,15,17,19,21,25) group (♦) versus those whose first alcohol consumption is over age (13,15,17,19,21,25) group (♢) respectively. The cumulative survival rate is the proportion of subjects within the group who survives (i.e. not developing alcohol dependence) at different points in time after the subjects’ first exposure to alcohol. The survival curves of the older alcohol consumption group (♢) are consistently above those of the younger group (♦), and their survival curves diverge farther and farther apart as time progresses. These graphs clearly indicate that subjects that consume alcohol at a later age are more likely to survive without alcohol dependence than those consume at an earlier age.

To further explore whether older participants reported regular drinking at a significantly older age, a median split by participant age (48 yrs) was made and the age of onset of regular drinking compared between the older (≥48 yrs), and younger (<48 yrs) cohorts for the entire sample and between men and women separately. Overall, the median survival estimate to regular drinking was significantly longer in older participants (≥48 yrs) (20 ± 0.10 yrs) than younger participants (<48 yrs = 17 ± 0.15 yrs) (Mantel-Cox Chi-Square =161, df=1, p<0.0001). Median survival estimates to regular drinking were also significantly longer in older women (≥ 47 yrs = 21 ± 0.14 yrs) as compared to younger women (≥47 yrs = 17 ±0.14 yrs) (Mantel-Cox Chi-Square =175.0, df=1, p<0.0001), and in older men (≥ 50 yrs = 19 ± 0.18 yrs) as compared to younger men (≥50 yrs= 17 ± 0.14 yrs) (Mantel-Cox Chi-Square =17.7, df=1, p<0.0001). Thus, overall survival times were longer for the older cohorts, however, women appear to show a larger cohort effect in survival time (4 yrs) than men (2 yrs).

Clinical course of alcoholism

Table 3 shows the pattern of appearance of the retrospective reports of the ages at first appearance of alcohol-related life events for all 1333 DSM-IV alcohol-dependent participants (e.g. probands, family members, random sample) in the UCSF Family Alcoholism Study. Results showed that men had a remarkably high degree of similarity to the women in the sample in their clinical course (r=.942, p<.0001). As seen in Table 3, men reported their first life events associating with drinking at a significantly earlier age than women (men= 20.7 yrs, women 23.5). However, by the late twenties/early thirties, the women had “caught up” with the men and were experiencing the more severe symptoms of heavy drinking and physical consequences at the same age as men.

Table 3.

Clinical Course of Alcoholism in Men and Women in the UCSF Study and a Comparison with COGA

| Alcohol-related life event in temporal rank order |

UCSF Patients who experienced event N (%) |

Age at which event first occurred in UCSF patients (Mean ± SD) |

Significant difference (p<0.001) in age between Men (M) and Women (W) |

Significant difference (p<0.001) in age between UCSF and COGA subjects |

Significant difference (p<0.001) in proportion between Men (M) and Women (W) |

Significant difference (p<0.001) in proportion between UCSF and COGA subjects |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Drank while in hazardous situation |

1109 (88.7) | 22.29 ± 7.9 | W > M | W < M | ||

| Physical fights | 431 (34.5) | 22.96 ± 7.9 | W > M | UCSF > COGA | W < M | UCSF < COGA |

| Hitting others without fighting |

328 (26.2) | 23.03 ± 7.6 | ||||

| Arguments | 970 (77.7) | 23.74 ± 8.7 | W > M | UCSF > COGA | ||

| Drank when not intended | 1069 (85.5) | 24.11 ± 8.5 | UCSF > COGA | UCSF > COGA | ||

| Blackouts | 1036 (82.9) | 24.17 ± 9.5 | UCSF > COGA | |||

| Hit/threw things | 639 (51.1) | 24.43 ± 8.6 | W > M | |||

| Arrested for alcohol related behavior |

396 (31.7) | 25.20 ± 9.0 | W < M | |||

| Lost friends | 585 (46.9) | 25.26 ± 8.7 | UCSF > COGA | |||

| Problems at work/school | 821 (65.7) | 25.37 ± 9.8 | UCSF > COGA | W < M | UCSF > COGA | |

| Problems with family, friends |

1004 (80.4) | 26.11 ± 9.4 | UCSF > COGA | UCSF > COGA | ||

| Tolerance | 1181 (94.4) | 26.21 ± 8.8 | W > M | UCSF > COGA | UCSF > COGA | |

| Binges | 734 (58.7) | 26.27 ± 9.4 | W < M | UCSF > COGA | ||

| Drank more than intended | 1207 (96.5) | 26.28 ± 9.4 | W > M | UCSF > COGA | UCSF > COGA | |

| Guilt | 1104 (88.3) | 26.29 ± 9.2 | UCSF > COGA | |||

| Interfered with work, responsibilities |

931 (74.4) | 26.40 ± 9.5 | UCSF > COGA | UCSF > COGA | ||

| Objections from family and friends |

1041 (83.3) | 27.12 ± 9.9 | W > M | UCSF > COGA | ||

| Hit family members | 331 (26.5) | 27.13 ± 9.0 | ||||

| Decreased important activities |

859 (68.8) | 27.21 ± 9.2 | UCSF > COGA | |||

| Problems in love relationship |

918 (73.4) | 27.22 ± 8.5 | UCSF > COGA | |||

| Little time for non-drinking activities |

874 (69.9) | 27.26 ± 9.4 | UCSF > COGA | UCSF > COGA | ||

| Self-injury while drunk | 712 (57.0) | 27.39 ± 10.4 | W < M | UCSF > COGA | ||

| Considered self excessive drinker |

1085 (86.8) | 27.71 ± 9.2 | UCSF > COGA | |||

| Arrested for DWI | 699 (55.9) | 27.74 ± 9.5 | W > M | W < M | UCSF > COGA | |

| Strong desire for alcohol | 776 (62.1) | 27.82 ± 9.4 | UCSF > COGA | |||

| Used rules for drinking | 936 (74.8) | 28.00 ± 8.9 | UCSF > COGA | UCSF > COGA | ||

| Morning drinking | 788 (63.0) | 28.10 ± 9.9 | UCSF > COGA | W < M | ||

| Wanted to quit 3+ times | 1060 (84.7) | 28.43 ± 9.1 | UCSF > COGA | UCSF > COGA | ||

| Inability to change drinking behavior |

575 (46.0) | 28.55 ± 9.6 | UCSF > COGA | W < M | ||

| Psychological impairment | 868 (89.5) | 28.64 ± 9.6 | UCSF > COGA | |||

| Shakes | 624 (50.9) | 28.79 ± 11.7 | UCSF > COGA | |||

| Unable to quit/cut down | 975 (81.2) | 29.17 ± 9.2 | UCSF > COGA | |||

| Continued despite physical illness |

501 (40.1) | 29.94 ± 9.4 | UCSF > COGA | |||

| Withdrawal | 853 (87.4) | 31.15 ± 10.3 | UCSF > COGA | |||

| Health problem occurred | 626 (50.0) | 33.00 ± 11.2 | UCSF > COGA | |||

| Sought professional help | 881 (70.4) | 33.16 ± 10.4 | UCSF > COGA |

The clinical course of alcoholism as represented by the temporal sequence of 36 alcohol-related life events for UCSF Family Study males and female participants who were alcohol-dependent, and a comparison to a sample of alcohol-dependent patients from the Collaborative Study on the Genetics of Alcoholism (COGA) study. An analysis of how many individuals endorsed individual items and whether they differed based on gender, or whether they were in the UCSF Family Study vs. COGA Study was evaluated using the Chi-Square test. The analyses of whether the age of first occurrence of each of the items differed based on: gender or UCSF vs. COGA was evaluated using t-tests. Significances (p<0.001) and their direction are indicated (e.g. W>M or UCSF>COGA) in the last 4 columns.

The comparison of response rates on individual alcohol-related life events between men and women participants revealed that while overall rates were substantially similar, men were significantly more likely to report: drinking while in a hazardous situations, binges, inability to change drinking behaviour, morning drinking, problems at work/school, physical fights, arrests for alcohol-related behaviour, and self injury while drunk (all p< 0.001) (see Table 3).

The retrospective reports of the sequence of 36 alcohol-related life events for UCSF family study participants who were alcohol-dependent compared to those reported in a sample of alcohol-dependent patients from the COGA study are shown in Table 3. Participants in the UCSF study had a high degree of similarity to the COGA sample in their clinical course whether they were compared using DSM-IV or DSM-III-R criteria (r=.904, p <.0001, DSM-IV, r=.923 p<.0001, DSM-III-R). While the two groups generally reported having experienced the same progression of events, COGA participants were found to first report alcohol-related life problems approximately two (2) years earlier than UCSF participants, however, by their late twenties/early thirties the UCSF participants were experiencing the more severe symptoms of heavy drinking and physical consequences at the same age as the COGA participants. When the same analyses were conducted using DSM-III-R criteria for the UCSF participants in the analyses, the only significant difference was that interfered with work responsibilities was no longer significant at the p<0.001 level (T=−3.09, df=1,1328, p<0.002).

The comparison of response rates on individual alcohol-related life events between all UCSF participants that met DSM-IV criteria and subjects from the COGA study revealed that UCSF participants were significantly more likely than COGA participants to endorse 27 of the 36 items (p<0.001). The only variable that more COGA participants endorsed was physical fights. When the same analyses were conducted using DSM-III-R criteria for the UCSF participants in the analyses, the only differences found were that UCSF participants were no longer significantly different from the COGA participants at the p<0.001 level on: wanted to quit more than three times, binges, and drank more than intended.

Heritability analyses

Age at which an individual first began regular drinking was not found to be significantly heritable. Whereas, DSM-IV alcohol dependence was found to be significantly heritable (h2 =0.24, p=0.0009). Additionally, when heritability was estimated for DSM-IV alcohol dependence in men and women separately, women were found to have a higher heritability estimate (h2 =0.46, p<0.0002) than men (h2 =0.32, p<.0366). It should be noted that while the difference in heritability estimates for males and females could not be directly tested, the non-overlapping confidence intervals suggest that this difference is likely to be significant.

DISCUSSION

Gender differences in alcohol use, abuse, and dependence are a consistent finding in the literature35. A significantly higher proportion of the population of men in the UCSF sample reported drinking regularly between the ages of 19 and 35 years than women, and those participants who developed regular drinking at younger ages were significantly more likely to become alcohol dependent than those who chose to begin regular drinking at later ages. This effect was particularly significant between ages 15 and 25. These data are consistent with a number of previous studies that have provided data to suggest that individuals who drink before the age of 15 years are substantially more likely to become alcohol dependent31, 36–38. The data from the UCSF study extends those findings and also demonstrated a cohort effect with the relatively younger women (<48 yrs) reporting a net decrease in the age of regular drinking that was twice as large (4 yrs) than that for men (2 yrs). These data confirm those published by Grucza and colleagues39, using data from the NLAES and NESARC who also found that age of onset of drinking had decreased in the younger birth cohorts examined. Additionally, Grucza and colleagues39, found that age of onset of drinking accounted for much of the increase in lifetime alcohol dependence among women.

Age at which a person first drank regularly was not found to be heritable in the population ascertained by the UCSF family study. These findings are consistent with data from Ehlers and colleagues31 who demonstrated that age at first intoxication was not heritable in a population of American Indians living on reservations. However, regular drinking in this study was not defined by a quantity and frequency measure. If regular drinking were defined differently, say as early problem drinking, it might have been found to be heritable. How environmental factors may influence the age at which a person first begins drinking regularly in such a way that leads to increased risk for alcohol dependence is not entirely clear. One hypothesis posits that early drinking disrupts the normal course of social and intellectual development leading to an increased risk for a number of social and psychological pathologies including drug addictions40, 41. An alternate hypothesis has been forwarded, suggesting that drug addictions and psychopathology are in fact a reflection of a more general underlying susceptibility to psychopathologies and disinhibitory behavior42–45. Although most studies point to “age of onset of regular drinking” as an environmental variable it may represent different constructs at different ages. For instance, very early onset of drinking (before the age of 13) may represent a more general measure of disinhibitory behavior or conduct disorder and as such could potentially be more heritable. In the present study the number of individuals with very early onset of drinking was limited and thus the statistical power for evaluation of the heritability of regular drinking in this age group was limited. As adolescence progresses, drinking becomes more common and may be highly influenced by such environmental variables such as peer pressure and social circumstances; whereas, individuals who have not drank regularly after the age of 21 may possess protective factors that may be both environmental (religion, family norms) or genetic (low tolerance to taste or effects of alcohol). Further studies are needed to disentangle the set of factors leading to regular drinking in adolescence.

A high degree of similarity was observed between men and women in the UCSF sample of alcohol dependents in many aspects of their clinical course. These data expand earlier findings from studies involving different subgroups of U.S. populations of alcoholics21, 22, 26–28, 46. While men and women in the UCSF study had highly similar clinical courses a few differences were found in the proportion of women participants endorsing individual alcohol-related items when compared to men. As might be predicted, men endorsed more antisocial symptoms than women such as physical fights and arrests. However, women in the UCSF sample were just as likely as men to endorse severe alcohol dependence symptomatolgy such as withdrawal, psychological impairment, health problems, and continued drinking despite health problems or serious illness. The age at which women first reported alcohol-related events was approximately three years later than men, but while their overall clinical course progressed highly similarly there was evidence of “telescoping” or a shortening clinical course by approximately four years. These data are consistent with several other studies that have reported telescoping of the clinical course of alcoholism in women20, 28, 47.

A high degree of similarity between UCSF Family Alcoholism Study participants and those participating in the COGA study in their clinical course was also found. However, COGA alcoholics reported alcohol-related life problems approximately three years earlier than the UCSF sample and alcohol dependent participants in the UCSF family study overall were significantly more likely to report alcohol-related life events than COGA participants. The only variable that was more frequent in the COGA sample was physical fights. Hill9 has suggested that the presence of fighting while intoxicated was the best discriminator of being an alcoholic from a family with a history of sociopathy. Gilligan and colleagues48 also suggested that fighting while drinking was associated with alcoholics who showed more antisocial behaviors. While ASPD was not directly assessed in the UCSF population these findings suggest that the UCSF study participants while endorsing a severe form of alcoholism with withdrawal and medical problems may have relatively less antisocial behaviors, such as fighting while intoxicated, than other large samples. These data also suggest that other risk factors most likely explain most of the genetic and environmental variance for the severe form of alcohol dependence seen in this sample, particularly in women. In this light, Hill9 has proposed a type III alcoholism that is not related to paternal sociopathy but still represents a severe form of the disorder.

Data from the UCSF study supports this idea that alcoholism in women can be significantly heritable and perhaps more heritable than in men, at least within this population. These data also support the conclusions of Hill35 who has questioned the notion that, in general, alcoholism in women may have less of a genetic diathesis in women. There have been conflicting data on estimates of heritability of alcohol dependence in women with some studies reporting negligible14 and others substantial18, 49 heritability. It has been suggested by Prescott and Kendler50, that conflicting results between studies might in part be due to differences in sampling methods. If differences in alcoholism rates between men and women are in part due to environmental factors (such as sex specific social pressures to drink (or not to drink) during adolescence and young adulthood) then one would predict that women would actually have a more heritable form of the disorder. This hypothesis is consistent with the data obtained in the UCSF Family Study where the heritability estimates for women were higher than for men.

This study has several implications for clinical medicine and public health. That this and other studies have found that earlier ages of onset of regular drinking are associated with higher rates of lifetime alcohol dependence suggests that clinicians should be giving this information to parents of children under the age of 13 years so that parents are better able to monitor and intervene if drinking starts during their children’s teenage years. If most of the variance in early drinking is environmental, as suggested by this and other studies, transmitting that information to parents and communities is important because environmental interventions at both the family and the community levels may be effective in reducing underage drinking. Clearly, the environmental factors that lead to early regular drinking need to be identified and preventive measures aimed at those factors implemented by parents and communities. Additionally, the fact that alcohol dependence has been found to be heritable in women as well as in men suggests that it is important to tell family members of an alcohol dependent proband that they are at increased risk for the development of the disorder regardless of the gender of the proband or family member. Finally, the fact that a number of studies have demonstrated that alcohol dependence has a clear clinical course and that the order of appearance of specific symptoms appears to be invariant to ethnic heritage, gender, or clinical subtype, strengthens the disease construct of the disorder. It also suggests that clinicians can estimate where a patient is on his/her clinical course by evaluating what symptoms he/she is currently experiencing. That kind of estimate is useful not only for evaluating prognosis but for assessing when interventions of different intensities may be appropriate based on the likely near term progression of the disease. That information is also useful to patients and their families for motivating and planning treatment interventions earlier rather than later in the disease progression.

However, the results of this study should be interpreted in the context of several limitations. First, the findings may not generalize to other large samples of alcoholics that were ascertained without bias. Second, only retrospective and cross-sectional data on alcohol use and use disorders were assessed. Third, comparisons to other large samples may be limited by differences on a variety of variables including recruitment, as well as a number of genetic and environmentally determined variables. The family design cannot distinguish whether the causes of familial similarity are genetic or environmental in nature. Finally, this study was not designed to measure unbiased heritability of alcohol consumption related traits. However, because sampling from families was biased towards alcohol dependent family members the observed estimates are biased but this is not expected to affect the assessment of whether a sex specific heritability is greater than that of the other gender.

Acknowledgements

Supported in part by funds from the State of California for medical research on alcohol and substance abuse through the University of California at San Francisco and additionally by the Ernest Gallo Foundation to KCW and U54 RR025024, AA010201 to CLE. The authors thank Shirley Sanchez for editing the manuscript.

Footnotes

Declaration of interest: The authors report no conflicts of interest. The authors alone are responsible for the content and writing of the paper.

References

- 1.Greenfield TK, Midanik LT, Rogers JD. A 10-year national trend study of alcohol consumption, 1984–1995: is the period of declining drinking over? Am J Public Health. 2000;90:47–52. doi: 10.2105/ajph.90.1.47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chan KK, Neighbors C, Gilson M, Larimer ME, Alan MG. Epidemiological trends in drinking by age and gender: providing normative feedback to adults. Addict Behav. 2007;32:967–976. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2006.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kessler RC, McGonagle KA, Zhao S, et al. Lifetime and 12-month prevalence of DSM-III-R psychiatric disorders in the United States. Results from the National Comorbidity Survey. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1994;51:8–19. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1994.03950010008002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hesselbrock VM, Hesselbrock MN. Are there empirically supported and clinically useful subtypes of alcohol dependence? Addiction. 2006;101 Suppl 1:97–103. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2006.01596.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cloninger CR, Bohman M, Sigvardsson S. Inheritance of alcohol abuse. Cross-fostering analysis of adopted men. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1981;38:861–868. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1981.01780330019001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Babor TF, Hofmann M, DelBoca FK, et al. Types of alcoholics, I. Evidence for an empirically derived typology based on indicators of vulnerability and severity. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1992;49:599–608. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1992.01820080007002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ehlers CL, Gilder DA, Slutske WS, Lind PA, Wilhelmsen KC. Externalizing disorders in American Indians: Comorbidity and a genome wide linkage analysis. Am J Med Genet B Neuropsychiatr Genet. 2008;147B:690–698. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.b.30666. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kunitz SJ, Gabriel KR, Levy JE, et al. Alcohol dependence and conduct disorder among Navajo Indians. J Stud Alcohol. 1999;60:159–167. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1999.60.159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hill SY. Absence of paternal sociopathy in the etiology of severe alcoholism: is there a type III alcoholism? J Stud Alcohol. 1992;53:161–169. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1992.53.161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cadoret RJ, O'Gorman TW, Troughton E, Heywood E. Alcoholism and antisocial personality. Interrelationships, genetic and environmental factors. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1985;42:161–167. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1985.01790250055007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cadoret RJ, Troughton E, O'Gorman TW. Genetic and environmental factors in alcohol abuse and antisocial personality. J Stud Alcohol. 1987;48:1–8. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1987.48.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Goodwin DW, Schulsinger F, Hermansen L, Guze SB, Winokur G. Alcohol problems in adoptees raised apart from alcoholic biological parents. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1973;28:238–243. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1973.01750320068011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Heath AC, Bucholz KK, Madden PA, et al. Genetic and environmental contributions to alcohol dependence risk in a national twin sample: consistency of findings in women and men. Psychol Med. 1997;27:1381–1396. doi: 10.1017/s0033291797005643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.McGue M, Pickens RW, Svikis DS. Sex and age effects on the inheritance of alcohol problems: a twin study. J Abnorm Psychol. 1992;101:3–17. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.101.1.3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pickens RW, Svikis DS, McGue M, Lykken DT, Heston LL, Clayton PJ. Heterogeneity in the inheritance of alcoholism. A study of male and female twins. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1991;48:19–28. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1991.01810250021002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Prescott CA, Caldwell CB, Carey G, Vogler GP, Trumbetta SL, Gottesman II. The Washington University Twin Study of alcoholism. Am J Med Genet B Neuropsychiatr Genet. 2005;134B:48–55. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.b.30124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Goodwin DW, Schulsinger F, Knop J, Mednick S, Guze SB. Alcoholism and depression in adopted-out daughters of alcoholics. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1977;34:751–755. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1977.01770190013001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kendler KS, Heath AC, Neale MC, Kessler RC, Eaves LJ. A population-based twin study of alcoholism in women. JAMA. 1992;268:1877–1882. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Prescott CA, Aggen SH, Kendler KS. Sex differences in the sources of genetic liability to alcohol abuse and dependence in a population-based sample of U.S. twins. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 1999;23:1136–1144. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.1999.tb04270.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Diehl A, Croissant B, Batra A, Mundle G, Nakovics H, Mann K. Alcoholism in women: is it different in onset and outcome compared to men? Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2007;257:344–351. doi: 10.1007/s00406-007-0737-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hesselbrock V. Female alcoholism: new perspectives-findings from the COGA Study. Collaborative Study on the Genetics of Alcoholism. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 1996;20:168A–171A. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.1996.tb01769.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Schuckit MA, Anthenelli RM, Bucholz KK, Hesselbrock VM, Tipp J. The time course of development of alcohol-related problems in men and women. J Stud Alcohol. 1995;56:218–225. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1995.56.218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Seaton KL, Cornell JL, Wilhelmsen KC, Vieten C. Effective strategies for recruiting families ascertained through alcoholic probands. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2004;28:78–84. doi: 10.1097/01.ALC.0000107200.88229.57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Vieten C, Seaton KL, Feiler HS, Wilhelmsen KC. The University of California, San Francisco Family Alcoholism Study. I. Design, methods, and demographics. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2004;28:1509–1516. doi: 10.1097/01.alc.0000142261.32980.64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bucholz KK, Cadoret R, Cloninger CR, et al. A new, semi-structured psychiatric interview for use in genetic linkage studies: a report on the reliability of the SSAGA. J Stud Alcohol. 1994;55:149–158. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1994.55.149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Schuckit MA, Smith TL, Anthenelli R, Irwin M. Clinical course of alcoholism in 636 male inpatients. Am J Psychiatry. 1993;150:786–792. doi: 10.1176/ajp.150.5.786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Schuckit MA, Smith TL, Danko GP, Reich T, Bucholz KK, Bierut LJ. Similarities in the clinical characteristics related to alcohol dependence in two populations. Am J Addict. 2002;11:1–9. doi: 10.1080/10550490252801594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ehlers CL, Wall TL, Betancourt M, Gilder DA. The clinical course of alcoholism in 243 Mission Indians. Am J Psychiatry. 2004;161:1204–1210. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.161.7.1204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Almasy L, Blangero J. Multipoint quantitative-trait linkage analysis in general pedigrees. Am J Hum Genet. 1998;62:1198–1211. doi: 10.1086/301844. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.S.F.B.R. Sequential Oligogenic Linkage Analysis Routines. 2009 Available at: URL: http://solar.sfbrgenetics.org/

- 31.Ehlers CL, Slutske WS, Gilder DA, Lau P, Wilhelmsen KC. Age at first intoxication and alcohol use disorders in Southwest California Indians. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2006;30:1856–1865. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2006.00222.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wilhelmsen KC, Ehlers C. Heritability of substance dependence in a Native American population. Psychiatr Genet. 2005;15:101–107. doi: 10.1097/00041444-200506000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rice JP, Neuman RJ, Saccone NL, et al. Age and birth cohort effects on rates of alcohol dependence. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2003;27:93–99. doi: 10.1097/01.ALC.0000047303.89421.AA. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Schuckit MA, Daeppen JB, Tipp JE, Hesselbrock M, Bucholz KK. The clinical course of alcohol-related problems in alcohol dependent and nonalcohol dependent drinking women and men. J Stud Alcohol. 1998;59:581–590. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1998.59.581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hill SY. Vulnerability to alcoholism in women. Genetic and cultural factors. Recent Dev Alcohol. 1995;12:9–28. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Grant BF, Dawson DA. Age at onset of alcohol use and its association with DSM-IV alcohol abuse and dependence: results from the National Longitudinal Alcohol Epidemiologic Survey. J Subst Abuse. 1997;9:103–110. doi: 10.1016/s0899-3289(97)90009-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hingson RW, Heeren T, Winter MR. Age at drinking onset and alcohol dependence: age at onset, duration, and severity. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2006;160:739–746. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.160.7.739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hawkins JD, Graham JW, Maguin E, Abbott R, Hill KG, Catalano RF. Exploring the effects of age of alcohol use initiation and psychosocial risk factors on subsequent alcohol misuse. J Stud Alcohol. 1997;58:280–290. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1997.58.280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Grucza RA, Norberg K, Bucholz KK, Bierut LJ. Correspondence between secular changes in alcohol dependence and age of drinking onset among women in the United States. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2008;32:1493–1501. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2008.00719.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.De Wit DJ, Adlaf EM, Offord DR, Ogborne AC. Age at first alcohol use: a risk factor for the development of alcohol disorders. Am J Psychiatry. 2000;157:745–750. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.157.5.745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.York JL. Clinical significance of alcohol intake parameters at initiation of drinking. Alcohol. 1999;19:97–99. doi: 10.1016/s0741-8329(99)00020-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Heath AC, Martin NG. Teenage alcohol use in the Australian twin register: genetic and social determinants of starting to drink. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 1988;12:735–741. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.1988.tb01337.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Iacono WG, Carlson SR, Malone SM, McGue M. P3 event-related potential amplitude and the risk for disinhibitory disorders in adolescent boys. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2002;59:750–757. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.59.8.750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.McGue M, Iacono WG, Legrand LN, Malone S, Elkins I. Origins and consequences of age at first drink. I. Associations with substance-use disorders, disinhibitory behavior and psychopathology, and P3 amplitude. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2001;25:1156–1165. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Prescott CA, Kendler KS. Age at first drink and risk for alcoholism: a noncausal association. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 1999;23:101–107. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Scott DM, Williams CD, Cain GE, et al. Clinical course of alcohol dependence in African Americans. J Addict Dis. 2008;27:43–50. doi: 10.1080/10550880802324754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Randall CL, Roberts JS, Del Boca FK, Carroll KM, Connors GJ, Mattson ME. Telescoping of landmark events associated with drinking: a gender comparison. J Stud Alcohol. 1999;60:252–260. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1999.60.252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Gilligan SB, Reich T, Cloninger CR. Alcohol-related symptoms in heterogeneous families of hospitalized alcoholics. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 1988;12:671–678. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.1988.tb00263.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kendler KS, Neale MC, Heath AC, Kessler RC, Eaves LJ. A twin-family study of alcoholism in women. Am J Psychiatry. 1994;151:707–715. doi: 10.1176/ajp.151.5.707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Prescott CA, Kendler KS. Influence of ascertainment strategy on finding sex differences in genetic estimates from twin studies of alcoholism. Am J Hum Genet. 2000;96:754–761. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]