Abstract

Lipolysis in adipocytes, the hydrolysis of triacylglycerol (TAG) to release fatty acids (FAs) and glycerol for use by other organs, is a unique function of white adipose tissue. Lipolysis in adipocytes occurs at the surface of cytosolic lipid droplets, which have recently gained much attention as dynamic organelles integral to lipid metabolism. Desnutrin/ATGL is now established as a bona fide TAG hydrolase and mutations in human desnutrin/ATGL/PNPLA2, as well as in its activator, comparative gene identification 58, are associated with Neutral Lipid Storage disease. Furthermore, recent identification of AdPLA as the major adipose phospholipase A2, has led to the discovery of a dominant autocrine/paracrine regulation of lipolysis through PGE2. Here, we review emerging concepts in the key players in lipolysis and the regulation of this process. We also examine recent findings in mouse models and humans with alterations/mutations in genes involved in lipolysis and discuss activation of lipolysis in adipocytes as a potential therapeutic target.

Keywords: lipolysis, obesity, adipocytes

1. Introduction: Lipolysis in adipocytes

Triacylglycerol (TAG) stored in white adipose tissue is the major energy reserve in mammals. Excess TAG accumulation in adipose tissue results in obesity as well as related metabolic disorders such as type 2 diabetes, cardiovascular disease and hypertension (Ahmadian et al., 2007). TAG is synthesized and stored in cytosolic lipid droplets during times of energy excess, and is mobilized from lipid droplets, via lipolysis, during times of energy need to generate fatty acids (FAs) (Ahmadian et al., 2007, Walther and Farese, 2009). Whereas, TAG synthesis occurs in other organs, such as the liver for VLDL production, lipolysis for the provision of FAs as an energy source for other organs is a unique function of adipocytes (Ahmadian et al., 2007). Increasing lipolysis in adipocytes may be a potentially useful therapeutic target for treating obesity. However, chronically high levels of FAs in the blood, typically observed in obesity, are correlated with many detrimental metabolic consequences such as insulin resistance. Here, we discuss the key players of lipolysis within adipocytes, as well as the regulation of this process. We also highlight recent findings in mouse models and humans with alterations/mutations in genes involved in lipolysis and discuss manipulating adipocyte lipolysis as a potential therapeutic target.

2. Pathogenesis

2.1 Lipid droplets

In adipocytes, TAG is stored in unilocular cytosolic lipid droplets. Although once considered to be inert storage sites, lipid droplets have recently become appreciated as dynamic organelles, central to lipid and energy metabolism. Lipid droplets are composed of a TAG and cholesterol ester core, surrounded by a phospholipid monolayer and coated with many proteins. Several of these proteins are characterized by the presence of a conserved N-terminal motif defined as a PAT domain, named after perilipin, adipophilin (also called adipocyte differentiation-related protein, ADRP), and tail-interacting protein of 47kDa (TIP47) but also including OXPAT/MLDP and S3-12 (Brasaemle, 2007). Furthermore, these PAT proteins are expressed in different tissues, suggesting potential tissue-specific functions (Brasaemle, 2007). Additionally, other proteins that may be involved in lipid droplet formation, lipid synthesis, lipolysis and membrane-trafficking are also found on lipid droplets (Guo et al., 2009, Gubern et al., 2009, Gubern et al., 2008, Yu et al., 1998). Caveolin, an integral membrane protein associated with cell surface pits (caveolae), has also been shown to localize to lipid droplets and regulate lipolysis (Cohen et al., 2004). The relative abundance of lipid droplet associated proteins, their posttranslational modifications and interactions with other proteins help to regulate lipolytic activity in adipocytes.

Despite recent progress in lipid droplet biology, several fundamental questions remain. First, how are lipid droplets formed? While several theories on lipid droplet biogenesis exist, the most widely accepted model states that neutral lipids accumulate in the ER bilayer and subsequently bud from the cytosolic leaflet of the membrane (Walther and Farese, 2009). However, further research is required to understand lipid droplet biogenesis. Furthermore, how is TAG transported from the site of synthesis to the lipid droplet to increase its size? Lipids must either be transported to the lipid droplet, perhaps via vesicular transport, or synthesized locally, possibly by enzymes such as diacylglycerol acyltransferases (DGATs) that have been shown to be present on lipid droplets (Walther and Farese, 2009, Guo et al., 2009). It is also postulated that smaller lipid droplets from newly formed TAG could fuse together to form larger lipid droplets (Walther and Farese, 2009, Guo et al., 2009). In addition, to help adipocytes deal with large amounts of incoming FAs it has been suggested that both lipid droplet biogenesis and growth may occur at the plasma membrane (Ost et al., 2005). In support of this hypothesis, caveolins that are involved in plasma membrane organization and endocytosis have been detected on lipid droplets and caveolin knockout mice exhibit defects in lipolysis (Cohen et al., 2004). Further investigation will be required to fully understand the development, expansion as well as many other aspects of lipid droplet biology.

2.2 The players in lipolysis in adipocytes

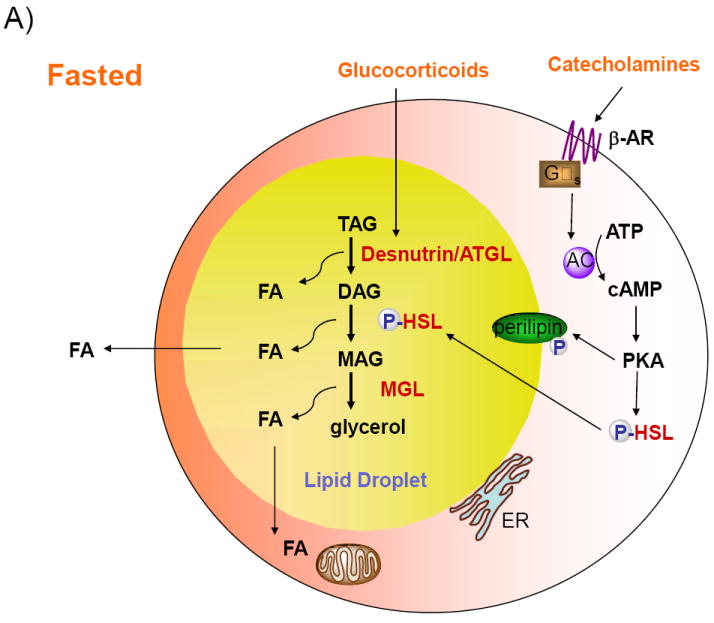

During times of energy shortage, TAG stored in lipid droplets is hydrolyzed to FAs and glycerol via lipolysis. FAs released from adipose tissue can enter the circulation and be taken up by other organs as an energy source for β-oxidation and subsequent ATP generation. Additionally, liberated FAs and glycerol can also serve as substrates in the liver for ketogenesis and gluconeogenesis, respectively (Stipanuk, 2006). Previously, hormone sensitive lipase (HSL) was considered to be the rate-limiting enzyme in TAG hydrolysis (Duncan et al., 2007). However, HSL knockout mice were not obese and accumulated diacylglycerol (DAG) in adipose tissue rather that TAG, implicating HSL as primarily a DAG lipase and suggesting the presence of additional novel lipase(s) in adipocytes (Haemmerle et al., 2002). In 2004, three laboratories independently identified the same novel TAG lipase named desnutrin, ATGL and phosphopholipase A2 ζ, leading to re-evaluation of the classic model of lipolysis (Villena et al., 2004, Jenkins et al., 2004, Zimmermann et al., 2004). Desnutrin/ATGL is predominantly expressed in adipose tissue and exhibits high substrate specificity for TAG (Villena et al., 2004, Zimmermann et al., 2004). Maximal activity of desnutrin/ATGL is dependent on its activator, comparative gene identification 58 (CGI-58), although the mechanism of this activation is not clear (Schweiger et al., 2009). Desnutrin/ATGL is now considered to be the major TAG lipase in adipose tissue, hydrolyzing TAG to DAG and a FA. DAG is subsequently hydrolyzed by HSL to generate monoacylglycerol (MAG) and a second FA. MAG lipase then hydrolyzes MAG producing glycerol and a third FA (Figure 1).

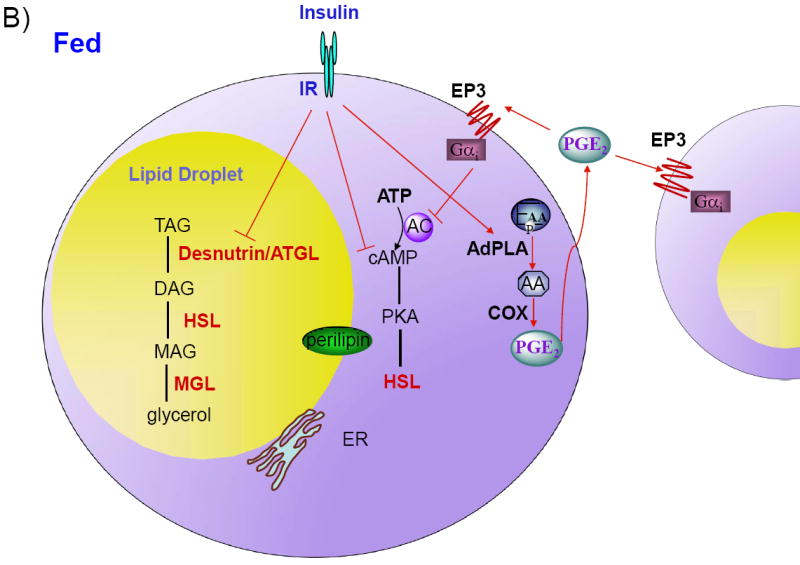

Figure 1. Regulation of lipolysis in adipocytes.

A) Desnutrin/ATGL initiates lipolysis by hydrolyzing triacylglycerol (TAG) to diacylglycerol (DAG). Hormone-sensitive lipase (HSL) hydrolyzes DAG to monoacylglycerol (MAG), which is subsequently hydrolyzed by MAG lipase to generate glycerol and three fatty acids (FAs). The FAs generated during lipolysis can be released into the circulation for use by other organs or oxidized within adipocytes. During fasting, catecholamines, by binding to Gαs-coupled β-adrenergic receptors (β-AR), activate adenylate cyclase (AC) to increase cAMP and activate protein kinase A (PKA). PKA phosphorylates HSL, resulting in translocation of HSL from the cytosol to the lipid droplet. PKA also phosphorylates the lipid droplet associated protein perilipin. Additionally, during fasting, glucocorticoids increase the expression of desnutrin/ATGL. B) In the fed state, insulin binding to the insulin receptor (IR), results in decreased cAMP levels and decreased lipolysis. Insulin also suppresses expression of desnutrin/ATGL. Recent studies have revealed that lipolysis is dominantly regulated by prostaglandin E2 (PGE2) through adipose-specific phospholipase A2 (AdPLA). AdPLA hydrolyzes the sn-2 position of phospholipids to generate arachidonic acid (AA), which via cyclooxygenase (COX) produces PGE2, that acts locally by binding to Gαi-coupled EP3 present in adipocytes, resulting in inhibition of AC and decreased lipolysis.

Mice lacking desnutrin/ATGL exhibit TAG accumulation in multiple organs, most notably the heart and die prematurely due to heart failure, preventing detailed characterization of lipolysis in adipocytes from these mice (Haemmerle et al., 2006). Transgenic mice overexpressing desnutrin/ATGL specifically in adipose tissue display elevated lipolysis and increased FA oxidation in white adipose tissue, resulting in higher energy expenditure and resistance to diet-induced obesity (Ahmadian et al., 2009). Interestingly, despite elevated lipolysis in these mice serum FA levels are not increased (Ahmadian et al., 2009). Generation of mice lacking desnutrin/ATGL specifically in adipose tissue will be crucial in fully characterizing the role of desnutrin/ATGL in lipolysis in adipocytes.

2.3 Regulation of lipolysis in adipocytes

Lipolysis in adipocytes is strongly regulated by hormones. In the fasted state, elevated glucocorticoids upregulate desnutrin/ATGL transcription (Villena et al., 2004) (Figure 1 A). Furthermore, catecholamines, by binding to Gαs-coupled β-adrenergic receptors, generate a signaling cascade that increases cAMP levels and activate protein kinase A (PKA). PKA phosphorylates HSL resulting in its translocation from the cytosol to the lipid droplet where it can hydrolyze DAG. PKA also phosphorylates the lipid droplet associated protein perilipin to provide lipases greater access to the lipid droplet (Brasaemle, 2007). In contrast, during the fed state insulin binds to its receptor in adipocytes and initiates a signaling event that, via phosphorylation and activation of phosphodiesterase 3B (PDE3B), decreases cAMP and ultimately inhibits lipolysis (Figure 1B). The importance of PDE3B in suppressing adipocyte lipolysis has been demonstrated in PDE3B null mice (Choi et al., 2006). In the fed state, insulin also suppresses the expression of desnutrin/ATGL, possibly through FoxO1 (Chakrabarti and Kandror, 2009). Although the C-terminal region of human desnutrin/ATGL contains two previously identified phosphoserine residues (S406 and S430), that are conserved in murine desnutrin/ATGL, phosphorylation of these sites does not appear to affect TAG hydrolysis or localization to lipid droplets (Duncan et al., 2009).

While the endocrine regulation of lipolysis by catecholamines and insulin has been well characterized, much remains to be investigated regarding the local regulation of lipolysis in adipocytes by autocrine/paracrine facors. Adipocytes secrete several factors that can regulate lipolysis locally, such as TNF-α which stimulates lipolysis and adenosine which inhibits lipolysis (Jaworski et al., 2007, Dhalla et al., 2009). Prostaglandins have also been shown to inhibit, stimulate, or have no effect on lipolysis depending on the concentration and species tested (Jaworski et al., 2007). However, recent identification of adipose-specific phospholipase A2 (AdPLA) has shed new light on a dominant autocrine/paracrine regulation of lipolysis by adipocyte-derived PGE2 (Duncan et al., 2008, Jaworski et al., 2009). AdPLA is a membrane-associated, calcium-dependent PLA2 and represents a new group of PLA2s, group XVI (Duncan et al., 2008). AdPLA is highly expressed exclusively in adipocytes and is the major PLA in adipocytes (Jaworski et al., 2009). As a PLA2, AdPLA catalyzes the release of FAs from the sn-2 position of phospholipids that is typically enriched in arachidonic acid, a substrate for the synthesis of eicosanoids (Jaworski et al., 2009) (Figure 1B). PGE2 is the predominant prostaglandin produced in white adipose tissue, and ablation of AdPLA in mice causes a >85% fall in PGE2 levels in this tissue. While PGE2 has 4 cognate receptors (EP1, EP2, EP3, and EP4), Gαi-coupled EP3 is expressed at >10-fold higher levels than the other EP receptors in adipose tissue (Jaworski et al., 2009). Reduced PGE2 levels induced by loss of AdPLA causes decreased EP3 signaling, which, in turn, elevates cAMP levels and activates lipolysis through PKA-mediated phosphorylation of HSL (Jaworski et al., 2009). The induction of AdPLA by feeding and insulin, suggests that it plays an important role in the suppression of lipolysis during the fed state (Jaworski et al., 2009). AdPLA null mice exhibit unrestrained adipocyte lipolysis and are resistant to both diet-induced and genetic obesity indicating that AdPLA is a critical factor in the development of obesity (Jaworski et al., 2009). Interestingly, similar to desnutrin/ATGL transgenic mice, increased lipolysis in these mice does not lead to elevated serum FA levels but instead promotes FA oxidation directly within adipocytes (Jaworski et al., 2009, Ahmadian et al., 2009).

In addition to the autocrine/paracrine regulation of lipolysis by PGE2, other signaling pathways through cytokines, growth hormones, AMP-activated protein kinase and nicotinic acid have also been shown to regulate lipolysis (Lafontan, 2008, Jaworski et al., 2007). Furthermore, in primates but not rodents, regulation of lipolysis by naturietic peptides through a cGMP dependent protein kinase (PKG) has also been shown to exist (Lafontan, 2008). However, future investigation into these pathways will be required to establish their relative importance in regulating lipolysis.

2.5 Human diseases with alterations in lipolysis in adipocytes

Mutations in the human desnutrin/ATGL gene (PNPLA2) are associated with a rare inherited disorder called Neutral Lipid Storage Disease with Myopathy (NLSDM), which results in systemic TAG accumulation, myopathy, cardiac abnormalities, and hepatomegaly (Schweiger et al., 2009). TAG accumulation in the heart causes cardiac defects reminiscent of the phenotype observed in mice lacking desnutrin/ATGL (Schweiger et al., 2009). Most of the identified mutations lead to the expression of C-terminally truncated versions of desnutrin/ATGL (Schweiger et al., 2009). Interestingly, these variants exhibit elevated enzyme activity in vitro compared to the full length form but fail to bind to lipid droplets in intact cells, suggesting that the lipolytic defect in these individuals is due to impaired localization of desnutrin/ATGL and that the C-terminus of desnutrin/ATGL likely contains a regulatory domain that affects hydrolase activity (Schweiger et al., 2009). In this regard, recent findings have shown that the N- and C-terminus of murine desnutrin/ATGL interact, suggesting that the negative regulatory role of the C-terminal domain in vitro likely results from masking of critical sites in the N-terminal patatin domain(Duncan et al., 2009). In humans, mutations in CGI-58, the activator of desnutrin/ATGL, have also been identified and, similar to individuals with mutated desnutrin/ATGL, they exhibit systemic TAG accumulation, mild myopathy and hepatomegaly (Schweiger et al., 2009). However, these individuals also display ichthyosis. This disease is known as Chanarin-Dorfman Syndrome or NLSD with ichthyosis (NLSD-I). Affected individuals express mutant forms of CGI-58 that are unable to activate desnutrin/ATGL, indicating that the TAG accumulation in tissues is due to defective desnutrin/ATGL function. It is interesting to note that, although desnutrin/ATGL and CGI-58 are highly expressed in adipocytes where lipolysis is the major function, patients with NLSDL or NLSDM are not obese (Schweiger et al., 2009). Further investigation into the roles of desnutrin/ATGL and CGI-58, particularly in human adipose tissue will be necessary to better understand and treat these diseases. Additionally, identification of single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) in other genes encoding proteins involved in lipolysis and characterization of their associated pathological syndromes will be crucial in helping to develop strategies to target lipolysis as a treatment for obesity or related diseases.

3. Therapy

It might be predicted that increasing lipolysis in adipocytes would lead to chronically high levels of circulating FAs that are correlated with adverse metabolic effects such as insulin resistance. Therefore, inhibiting lipolysis to lower serum FA levels has been a therapeutic approach for the management of insulin resistance and type 2 diabetes. Nicotinic acid and its analog acipimox have been used as antilipolytic agents for the treatment of dyslipidemia (Dhalla et al., 2009). However, their therapeutic usefulness is limited since the initial decrease in serum FA levels is followed by a rebound effect resulting in increased serum FA levels and insulin resistance (Dhalla et al., 2009).

Interestingly, mouse models of increased lipolysis do not have elevated serum FA levels, revealing that increasing lipolysis in adipocytes does not alter serum FA levels. Rather, increasing lipolysis in mice results in leanness and promotes FA oxidation directly within adipocytes (Ahmadian et al., 2009, Jaworski et al., 2009, Saha et al., 2004, Tansey et al., 2001), suggesting that activation of lipolysis may be a promising therapeutic target for the treatment of obesity. In this regard, adipocytes from obese humans have reduced lipolytic capacity and desnutrin/ATGL expression is reduced in adipose tissue of ob/ob mice (Langin et al., 2005, Villena et al., 2004). It is important to note that when FAs are generated at a rate that exceeds the oxidative capacity of adipose tissue, ectopic TAG storage and insulin resistance may result, as seen in many lipodystrophy models (Jaworski et al., 2009). Therefore, partial activation of lipolysis in adipocytes may be a more promising therapeutic approach. However, since there are numerous genes involved in lipolysis including those that encode for lipolytic enzymes, regulatory proteins as well as lipid droplet associated proteins, it is important that the tissue specificity of the target is taken into account. As discussed above, mutations in desnutrin/ATGL as well as CGI-58 severely affect multiple tissues. In this regard, AdPLA may represent an ideal target for manipulating lipolysis since it is highly expressed only in adipose tissue and is therefore less likely to have off-target effects. Future investigation into the role AdPLA in human adipocytes as well as the pathological syndrome of humans with SNPs in the AdPLA (PLA2G16) gene will help answer some of these questions. Furthermore, as more lipid droplet associated proteins are identified and characterized there will likely be more potential therapeutic targets for modulating lipolysis.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Ahmadian M, Duncan RE, Jaworski K, Sarkadi-Nagy E, Sul HS. Triacylglycerol metabolism in adipose tissue. Future Lipdol. 2007;2:229–237. doi: 10.2217/17460875.2.2.229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahmadian M, Duncan RE, Varady KA, Frasson D, Hellerstein MK, Birkenfeld AL, Samuel VT, Shulman GI, Wang Y, Kang C, Sul HS. Adipose overexpression of desnutrin promotes fatty acid use and attenuates diet-induced obesity. Diabetes. 2009;58:855–866. doi: 10.2337/db08-1644. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brasaemle DL. Thematic review series: adipocyte biology. The perilipin family of structural lipid droplet proteins: stabilization of lipid droplets and control of lipolysis. J Lipid Res. 2007;48:2547–2559. doi: 10.1194/jlr.R700014-JLR200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chakrabarti P, Kandror KV. FoxO1 controls insulin-dependent adipose triglyceride lipase (ATGL) expression and lipolysis in adipocytes. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:13296–13300. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C800241200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi YH, Park S, Hockman S, Zmuda-Trzebiatowska E, Svennelid F, Haluzik M, Gavrilova O, Ahmad F, Pepin L, Napolitano M, Taira M, Sundler F, Stenson Holst L, Degerman E, Manganiello VC. Alterations in regulation of energy homeostasis in cyclic nucleotide phosphodiesterase 3B-null mice. J Clin Invest. 2006;116:3240–3251. doi: 10.1172/JCI24867. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen AW, Razani B, Schubert W, Williams TM, Wang XB, Iyengar P, Brasaemle DL, Scherer PE, Lisanti MP. Role of caveolin-1 in the modulation of lipolysis and lipid droplet formation. Diabetes. 2004;53:1261–1270. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.53.5.1261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dhalla AK, Chisholm JW, Reaven GM, Belardinelli L. A1 adenosine receptor: role in diabetes and obesity. Handb Exp Pharmacol. 2009:271–295. doi: 10.1007/978-3-540-89615-9_9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duncan RE, Ahmadian M, Jaworski K, Sarkadi-Nagy E, Sul HS. Regulation of lipolysis in adipocytes. Annu Rev Nutr. 2007;27:79–101. doi: 10.1146/annurev.nutr.27.061406.093734. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duncan RE, Sarkadi-Nagy E, Jaworski K, Ahmadian M, Sul HS. Identification and functional characterization of adipose-specific phospholipase A2 (AdPLA) J Biol Chem. 2008;283:25428–25436. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M804146200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duncan RE, Wang Y, Ahmadian M, Lu J, Sarkadi-Nagy E, Sul HS. Characterization of desnutrin functional domains:Critical residues for triacylglycerol hydrolysis in cultured cells. J Lipid Res. 2009 doi: 10.1194/jlr.M000729. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gubern A, Barcelo-Torns M, Casas J, Barneda D, Masgrau R, Picatoste F, Balsinde J, Balboa MA, Claro E. Lipid droplet biogenesis induced by stress involves triacylglycerol synthesis that depends on group VIA phospholipase A2. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:5697–5708. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M806173200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gubern A, Casas J, Barcelo-Torns M, Barneda D, de la Rosa X, Masgrau R, Picatoste F, Balsinde J, Balboa MA, Claro E. Group IVA phospholipase A2 is necessary for the biogenesis of lipid droplets. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:27369–27382. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M800696200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo Y, Cordes KR, Farese RV, Jr, Walther TC. Lipid droplets at a glance. J Cell Sci. 2009;122:749–752. doi: 10.1242/jcs.037630. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haemmerle G, Lass A, Zimmermann R, Gorkiewicz G, Meyer C, Rozman J, Heldmaier G, Maier R, Theussl C, Eder S, Kratky D, Wagner EF, Klingenspor M, Hoefler G, Zechner R. Defective lipolysis and altered energy metabolism in mice lacking adipose triglyceride lipase. Science. 2006;312:734–737. doi: 10.1126/science.1123965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haemmerle G, Zimmermann R, Hayn M, Theussl C, Waeg G, Wagner E, Sattler W, Magin TM, Wagner EF, Zechner R. Hormone-sensitive lipase deficiency in mice causes diglyceride accumulation in adipose tissue, muscle, and testis. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:4806–4815. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110355200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaworski K, Ahmadian M, Duncan RE, Sarkadi-Nagy E, Varady KA, Hellerstein MK, Lee H-Y, Samuel VT, Shulman GI, Kim K-H, de Val S, Kang C, Sul HS. AdPLA ablation increases lipolysis and prevents obesity induced by high-fat feeding or leptin deficiency. Nat Med. 2009;15:159–168. doi: 10.1038/nm.1904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaworski K, Sarkadi-Nagy E, Duncan RE, Ahmadian M, Sul HS. Regulation of triglyceride metabolism. IV. Hormonal regulation of lipolysis in adipose tissue. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2007;293:G1–4. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00554.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jenkins CM, Mancuso DJ, Yan W, Sims HF, Gibson B, Gross RW. Identification, cloning, expression, and purification of three novel human calcium-independent phospholipase A2 family members possessing triacylglycerol lipase and acylglycerol transacylase activities. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:48968–48975. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M407841200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lafontan M. Advances in adipose tissue metabolism. Int J Obes (Lond) 2008;32(Suppl 7):S39–51. doi: 10.1038/ijo.2008.237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langin D, Dicker A, Tavernier G, Hoffstedt J, Mairal A, Ryden M, Arner E, Sicard A, Jenkins CM, Viguerie N, van Harmelen V, Gross RW, Holm C, Arner P. Adipocyte lipases and defect of lipolysis in human obesity. Diabetes. 2005;54:3190–3197. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.54.11.3190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ost A, Ortegren U, Gustavsson J, Nystrom FH, Stralfors P. Triacylglycerol is synthesized in a specific subclass of caveolae in primary adipocytes. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:5–8. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C400429200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saha PK, Kojima H, Martinez-Botas J, Sunehag AL, Chan L. Metabolic adaptations in the absence of perilipin: increased beta-oxidation and decreased hepatic glucose production associated with peripheral insulin resistance but normal glucose tolerance in perilipin-null mice. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:35150–35158. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M405499200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schweiger M, Lass A, Zimmermann R, Eichmann TO, Zechner R. Neutral lipid storage disease: genetic disorders caused by mutations in adipose triglyceride lipase/PNPLA2 or CGI-58/ABHD5. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2009;297:E289–296. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00099.2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stipanuk M. Biochemical, Physiological, Molecular Aspects of Human Nutrition. St Louis: Elsevier; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Tansey JT, Sztalryd C, Gruia-Gray J, Roush DL, Zee JV, Gavrilova O, Reitman ML, Deng CX, Li C, Kimmel AR, Londos C. Perilipin ablation results in a lean mouse with aberrant adipocyte lipolysis, enhanced leptin production, and resistance to diet-induced obesity. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98:6494–6499. doi: 10.1073/pnas.101042998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Villena JA, Roy S, Sarkadi-Nagy E, Kim KH, Sul HS. Desnutrin, an adipocyte gene encoding a novel patatin domain-containing protein, is induced by fasting and glucocorticoids: ectopic expression of desnutrin increases triglyceride hydrolysis. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:47066–47075. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M403855200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walther TC, Farese RV., Jr The life of lipid droplets. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2009;1791:459–466. doi: 10.1016/j.bbalip.2008.10.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu W, Bozza PT, Tzizik DM, Gray JP, Cassara J, Dvorak AM, Weller PF. Co-compartmentalization of MAP kinases and cytosolic phospholipase A2 at cytoplasmic arachidonate-rich lipid bodies. Am J Pathol. 1998;152:759–769. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zimmermann R, Strauss JG, Haemmerle G, Schoiswohl G, Birner-Gruenberger R, Riederer M, Lass A, Neuberger G, Eisenhaber F, Hermetter A, Zechner R. Fat mobilization in adipose tissue is promoted by adipose triglyceride lipase. Science. 2004;306:1383–1386. doi: 10.1126/science.1100747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]