Abstract

Bacterial and synthetic DNAs containing CpG dinucleotides in specific sequence contexts activate the vertebrate immune system through Toll-like receptor 9 (TLR9). In the present study, we used a synthetic nucleoside with a bicyclic heterobase [1-(2′-deoxy-β-d-ribofuranosyl)-2-oxo-7-deaza-8-methyl-purine; R] to replace the C in CpG, resulting in an RpG dinucleotide. The RpG dinucleotide was incorporated in mouse- and human-specific motifs in oligodeoxynucleotides (oligos) and 3′-3-linked oligos, referred to as immunomers. Oligos containing the RpG motif induced cytokine secretion in mouse spleen-cell cultures. Immunomers containing RpG dinucleotides showed activity in transfected-HEK293 cells stably expressing mouse TLR9, suggesting direct involvement of TLR9 in the recognition of RpG motif. In J774 macrophages, RpG motifs activated NF-κB and mitogen-activated protein kinase pathways. Immunomers containing the RpG dinucleotide induced high levels of IL-12 and IFN-γ, but lower IL-6 in time- and concentration-dependent fashion in mouse spleen-cell cultures costimulated with IL-2. Importantly, immunomers containing GTRGTT and GARGTT motifs were recognized to a similar extent by both mouse and human immune systems. Additionally, both mouse- and human-specific RpG immunomers potently stimulated proliferation of peripheral blood mononuclear cells obtained from diverse vertebrate species, including monkey, pig, horse, sheep, goat, rat, and chicken. An immunomer containing GTRGTT motif prevented conalbumin-induced and ragweed allergen-induced allergic inflammation in mice. We show that a synthetic bicyclic nucleotide is recognized in the C position of a CpG dinucleotide by immune cells from diverse vertebrate species without bias for flanking sequences, suggesting a divergent nucleotide motif recognition pattern of TLR9.

The immune system of vertebrates recognizes synthetic oligodeoxynucleotides, bacterial and plasmid DNAs containing unmethylated CpG dinucleotides in specific sequence contexts (CpG motifs) (1-5). This recognition is mediated by a molecular pattern recognition receptor, Toll-like receptor 9 (TLR9) (6). Upon activation by CpG DNA, TLR9 initiates signaling pathways that activate several transcription factors, including NF-κB and AP-1 (3-5). The immunological events that occur after CpG DNA activation of the immune system include B cell proliferation, increased expression of MHC class II antigens, increased synthesis of RNA and DNA, and the release of a number of cytokines and chemokines (7-9). The potent T helper 1 immune response produced by CpG activation of the innate immune system supports the broad therapeutic application of CpG DNA against cancer, infectious diseases, asthma, and allergies and as adjuvants in immunotherapy. Several studies have demonstrated the potential effectiveness of CpG DNAs as therapies in animal models, and a number of CpG DNAs are currently being tested in clinical trials (4, 10).

We previously showed that two CpG DNAs attached through their 5′ ends failed to stimulate the immune system, while CpG DNAs designed to contain two 5′ ends through a 3′-3-linkage of DNA had enhanced activity (11-16). Blocking of the 5′ end of DNA, even with fluorescein conjugation, resulted in the loss of activity (12). These studies suggested that an accessible 5′ end of CpG DNA was required for activity and that the receptor(s) read the DNA sequence from the 5′ end. We called such 3′-3′-attached CpG DNAs immunomers (13, 14).

Optimal sequences for activating TLR9 vary among species (7, 17-19). The CpG motifs that are most active in the mouse system are poorly active in human systems and vice versa. Different CpG DNA sequences are usually required, therefore, for preclinical animal and human clinical studies. As a part of continued understanding of CpG DNA-TLR9 recognition and development of potent synthetic immunostimulatory motifs, we are also working to develop synthetic motifs that are recognized by TLR9 of different species without motif specificity.

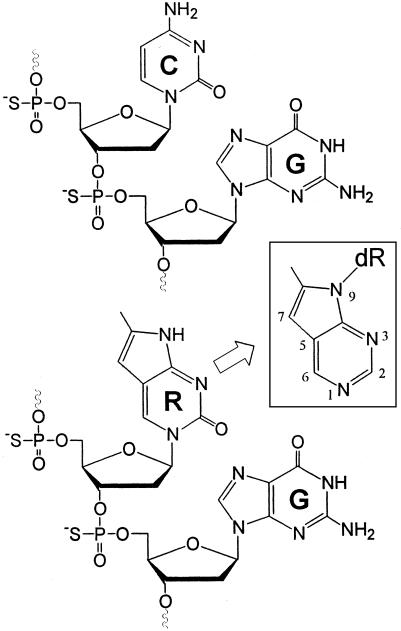

In the present study, we showed that a bicyclic analog, 1-(2′-deoxy-β-d-ribofuranosyl)-2-oxo-7-deaza-8-methyl-purine (R, Fig. 1) could be used to replace deoxycytidine (but not deoxyguanosine) in a CpG dinucleotide to create a synthetic immunostimulatory dinucleotide referred to as RpG dinucleotide. Human- and mouse-specific oligonucleotides and immunomers containing the RpG dinucleotide were potent immunostimulators in both mouse and human systems, without species specificity. Mouse and human immunomers with RpG motifs also stimulated peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) from human, monkey, pig, horse, sheep, goat, rat, and chicken in a motif-independent fashion. We show immunostimulatory activity by using a bicyclic heterobase in place of deoxycytidine in a CpG dinucleotide.

Fig. 1.

Structures of natural CpG and synthetic RpG immunostimulatory dinucleotides. (Inset) Structure of a 7-deaza-purine with 9-glycoside is shown for comparison.

Materials and Methods

Synthesis and Purification of CpG and RpG Oligonucleotides. Oligonucleotides were synthesized with phosphorothioate backbone modification, deprotected, purified by HPLC, and characterized by capillary gel electrophoresis and matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization-time-of-flight MS as described (13, 14). The phosphoramidites of dA, dG, dC, and T were obtained from Applied Biosystems. The solid support attached with diDMT-protected glyceryl linker to synthesize immunomers was obtained from ChemGenes (Ashland, MA). Phosphoramidite of the synthetic nucleoside (R) used in the study was obtained from Glen Research (Sterling, VA). The purity of full-length oligonucleotides ranged from 89% to 95% with the remaining oligonucleotides being shorter by 1 or 2 nt (n-1 and n-2) as determined by capillary gel electrophoresis and/or denaturing PAGE. All oligos contained <0.5 units/ml endotoxin as determined by Limulus assay (BioWhittaker).

Cell Culture Conditions, Reagents, and Mice. Spleen cells from 4- to 8-week-old BALB/c, C57BL/6, or C3H/HeJ mice were cultured in RPMI complete medium as described (20). Murine J774 macrophage cells (American Type Culture Collection) were cultured in DMEM supplemented with 10% (vol/vol) FCS, 50 mM 2-mercaptoethanol, and antibiotics (100 units/ml penicillin G/streptomycin). All other culture reagents were purchased from Mediatech (Gaithersburg, MD). BALB/c, C57BL/6, C3H/HeJ, and AKR/j mice were obtained from Taconic Farms or The Jackson Laboratory and maintained in accordance with the Hybridon Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee-approved animal protocols.

Cytokine ELISAs. Mouse spleen or J774 cells were plated in 24-well dishes by using 5 × 106 or 1 × 106 cells per ml, respectively. Oligonucleotides dissolved in TE buffer (10 mM Tris·HCl, pH 7.5/1 mM EDTA) were added to a final concentration of 0.03, 0.1, 0.3, 1.0, 3.0, or 10.0 μg/ml to the cell cultures. The cells were then incubated at 37°C for 24 h, and the supernatants were collected for ELISA assays. The experiments were performed two or three times for each oligo in triplicate for each concentration. For kinetics studies, spleen cells were stimulated with 10 units/ml recombinant human IL-2 (Sigma) before activating the cells with different concentrations of oligos for 4, 8, 24, or 48 h. The secretion of IL-12, IFN-γ, and IL-6 was measured by sandwich ELISA as described (14). The required reagents, including cytokine antibodies and standards, were purchased from BD Biosciences (San Diego).

Mouse Splenomegaly Assay. Female BALB/c mice (4-6 weeks, 19-21 g) were divided into groups of two or three mice. Oligonucleotides dissolved in sterile PBS were administered s.c. to mice at a dose of 5 mg/kg. The mice were killed after 72 h, and the spleens were harvested and weighed as described (20, 21).

Stimulation of HEK293 Cells Stably Expressing Mouse TLR9. HEK293 cells stably expressing mouse TLR9 as a fusion protein with yellow fluorescent protein (293 moTLR9-YFP; C.F.K. and E.L., unpublished work), as well as 293 cells transfected with empty vector (pcDNA3), were plated in DMEM (BioWhittaker) containing 10% FCS (GIBCO Life Sciences) and 10 μg/ml ciprofloxacin (Mediatech) at a density of 3 × 104 cells per well in a 96-well dish. The next day, cells were stimulated for 12 h with 10 μg/ml of oligos, before harvesting of supernatant and measurement of IL-8 release by ELISA (Duoset, R & D Systems).

Preparation of J774 Cell Extracts and Assays for NF-κB and IκBα Activation. For NF-κB activation, J774 cells were plated at a density of 5 × 106 cells per well in six-well plates and treated with oligos at a concentration of 10 μg/ml for 1 h, and nuclear extracts were prepared as described (16). Protein concentrations were determined, mixed with a 5′ 32P-labeled NF-κB-specific oligonucleotide probe, and analyzed on a 6% native polyacrylamide gel in TBE buffer (22.5 mM Tris/22.5 mM boric acid/0.5 mM EDTA, pH 8.3) at 140 V for 2-3 h as described (14). IκBα levels in the cytoplasmic extracts were monitored by Western blotting using rabbit polyclonal antibody to IκBα (Santa Cruz Biotechnology) as described (14). Gels were dried and exposed to Kodak Biomax MR film at -70°C. Films were scanned, and the images were processed with ADOBE imaging software.

Isolation of Human B Cells. PBMCs from freshly drawn healthy volunteer blood (CBR Laboratories, Boston) were isolated by the Ficoll density gradient centrifugation method (Histopaque-1077, Sigma), and B cells were isolated from PBMCs by positive selection by using the CD19 cell isolation kit (Miltenyi Biotec) according to the manufacturer's instructions.

Isolation of PBMCs from Monkey, Pig, Horse, Goat, Sheep, Rat, and Chicken Blood. Peripheral blood from cynomolgus monkey, pig (Yorkshire), goat (Boer), sheep (domestic Rambouillet/cross), and Sprague-Dawley rat was obtained from Charles River Breeding Laboratories. Peripheral blood of horse and chicken (Rhode Island Red) was a generous gift from Cathy Cedar (TranXenogen, Shrewsbury, MA). PBMCs were isolated by the Histopaque-Ficoll method (sheep, goat, horse, and pig, at 800 × g, 45 min; monkey and rat, at 400 × g, 30 min; and chicken, at 500 × g, 20 min).

B Cell and PBMC Proliferation Assays. A total of 1 × 105 B cells or 2 × 105 PBMCs per 200 μl were stimulated with different concentrations of oligos for 66 h, then pulsed with 0.75 μCi of [3H]thymidine and harvested 8 h later. The results are expressed as proliferation index (cpm of stimulated wells/cpm of medium control).

Sensitization of Mice with Conalbumin (CA) and Ragweed Allergen. Four- to 6-week-old BALB/c or AKR/j mice were given i.p. injections of 200 μg of CA (Sigma) or ragweed (Greer Labs, Lenoir, NC), respectively, in 100 μl of PBS mixed with 100 μl of ImjectAlum adjuvant (Pierce) on days 0 and 7, and intranasally challenged on days 14 and 21 with the same allergen. The mice were killed by CO2 inhalation 72 h after the last challenge. Spleens were excised and single-cell suspensions were prepared as described above. Spleen cells were treated with oligos at different concentrations for 2 h followed by treatment with 50 μg/ml CA. Supernatants were harvested after 72 h, and IL-5, IFN-γ, and IL-12 levels were measured by ELISA as described above.

CA Sensitization of Mice and Treatment with RpG Immunomer. Four- to 5-week-old female BALB/c mice received i.p. injections of 200 μg of CA adsorbed to 100 μl of Imject Alum and dissolved in 100 μl of PBS on days 0, 7, and 14. The mice received intranasal challenges with 100 μg/ml CA in 20 μl of PBS on days 21, 22, and 23. Nonsensitized control mice received i.p. injections and intranasal challenges of PBS. Mice received immunomer 7 in PBS at a dose of 50 μg per mouse through s.c. injection on days 0, 7, and 14 simultaneously with CA sensitization. Blood was drawn on day 24, i.e., 24 h after last CA challenge. Serum was analyzed for CA-specific serum IgE, IgG1, and IgG2a and total serum IgG levels.

Results

Structure of RpG Dinucleotide, Design, and Synthesis of Oligonucleotides and Immunomers. The structures of natural CpG and RpG dinucleotides are shown in Fig. 1. R has a chemical structure similar to that of a 7-deaza-8-methyl-purine (see Fig. 1 Inset) but the glycoside is at position 1 rather than position 9 as in natural purines (22). We synthesized oligos and immunomers incorporating R in place of either cytosine or guanine in CpG dinucleotide and studied the effect of the resulting oligos on immune stimulation. Oligos 1, 2, and 6 contained a GACGTT nucleotide motif that was specifically recognized by mouse immune cells and 4, 5, and 7 contained a GTCGTT nucleotide motif that was preferentially recognized by human immune cells (Table 1). Compound 3 contained R in the G position (Table 1). Incorporation of the modification was characterized by matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization-time-of-flight mass analysis of the purified products, and the data are presented in Table 1.

Table 1. Oligonucleotide sequences, modifications, mass spectral analysis, and murine in vivo and in vitro immunostimulatory data.

| Molecular mass,†m/z

|

Spleen weight,‡ mg ± SD

|

IL-12,¶ pg/ml ± SD

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number | Sequence* | Found | Calculated | C3H/HeJ | C57BL/6 | BALB/c | |

| Oligo 1 | 5′-CTATCTGACGTTCTCTGT-3′ | 5,705 | 5,704 | 134 ± 7 | 1,866 ± 83 | 1,489 ± 88 | 3,635 ± 165 |

| Oligo 2 | 5′-CTATCTGARGTTCTCTGT-3′ | 5,742 | 5,741 | 125 ± 7 | 1,323 ± 409 | 1,177 ± 74 | 2,754 ± 20 |

| Oligo 3 | 5′-CTATCTGACRTTCTCTGT-3′ | 5,702 | 5,701 | 85 ± 4 | 57 ± 20 | 256 ± 91 | 103 ± 6 |

| Oligo 4 | 5′-CTATCTGTCGTTCTCTGT-3′ | 5,694 | 5,695 | 113 ± 6 | 669 ± 96 | 709 ± 35 | 1,653 ± 4 |

| Oligo 5 | 5′-CTATCTGTRGTTCTCTGT-3′ | 5,736 | 5,732 | 123 ± 3 | 779 ± 45 | 885 ± 9 | 1,770 ± 104 |

| Immunomer 6 | 5′-TCTGARGTTCT-L-TCTTGRAGTCT-5′ | 7,247 | 7,242 | 157 ± 32 | 2,487 ± 201 | 2,059 ± 78 | 5,211 ± 336 |

| Immunomer 7 | 5′-TCTGTRGTTCT-L-TCTTGRTGTCT-5′ | 7,228 | 7,224 | 134 ± 33 | 2,743 ± 164 | 2,390 ± 186 | 6,021 ± 601 |

| Medium | — | — | 78 ± 12§ | 37 ± 1 | 99 ± 18 | 37 ± 4 | |

All oligos and immunomers are phoshorothioate backbone modified; L, glycerol linker in immunomers; mouse- (1–3, and 6) and human- (4, 5, and 7) specific CpG and RpG motifs are shown underlined

Matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization–time-of-flight mass data

Splenectomy, 72 h after s.c. administration at a single dose of 5 mg/kg; values shown are averages of two or three mice

Control group injected with PBS

At 1 μg/ml concentration of compounds; medium values are in the absence of CpG activation; each value is an average of triplicate measurements, and the data shown are representative of two or three independent experiments

RpG Oligos Induce Cytokine Secretion in Mouse Spleen Cell Cultures. Oligos 1 and 2 at concentrations of 0.1, 0.3, 1.0, 3.0, and 10.0 μg/ml induced concentration-dependent cytokine secretion in all three strains of mouse spleen cell cultures (Table 2, which is published as supporting information on the PNAS web site). Consistent with earlier reports (23-27), the parent oligo 1 at 1.0 μg/ml showed potent induction of IL-12 (Table 1) and IL-6 (Table 2) in all three mouse strains. In comparison, oligo 2, which contained R in place of C, induced less IL-12 at lower concentrations but more at higher concentrations than did oligo 1 (Table 2). With the control oligonucleotide, which contained R in place of G, cytokine levels were similar to background (see IL-12 data in Table 1), suggesting that the receptor recognized R in place of C but not in place of G.

Whereas oligos 1 and 2 induced similar levels of IL-12, 2 induced much less IL-6 secretion than did 1 in all three strains of mouse spleen cell cultures (Table 2). Human-specific oligos 4 and 5, with CpG and RpG dinucleotides, respectively, also induced cytokine secretion in mouse spleen cell cultures (Table 1), abut the response with 4 was lower than with 1 as expected.

Immunomers Containing RpG Dinucleotides Show Potent Immune Stimulation. In mouse spleen cells, both mouse-specific (6) and human-specific (7) immunomers produced potent induction of cytokines (IL-12 and IL-6) compared with 1 and 4 (Tables 1 and 2). In general, immunomer 6 induced higher levels of cytokines than did 1 (Table 1). Surprisingly, human-specific immunomer 7 also induced cytokine levels similar to those induced by 6 in all three strains of mouse spleen cell cultures (Tables 1 and 2).

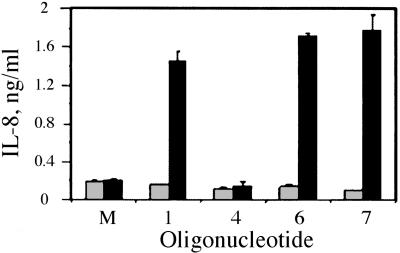

TLR9 Recognizes Both CpG and RpG Motifs. To test whether the RpG dinucleotide was recognized by TLR9, we used HEK293 cells expressing mouse TLR9 as a fusion protein with yellow fluorescent protein. The results are presented as induction of IL-8 secretion levels in Fig. 2. Mouse-specific CpG oligo 1 produced a measurable response, whereas human-specific CpG oligo 4 produced no response, suggesting species-specific recognition of 1 by mouse TLR9 as expected (Fig. 2). Mouse-specific RpG immunomer 6 induced greater IL-8 secretion than did 1, suggesting that mouse TLR9 recognized the RpG motif, and it was more potent than 1 (Fig. 2). Surprisingly, human-specific RpG immunomer 7 also stimulated high levels of IL-8 secretion, suggesting specific recognition of this motif by mouse TLR9 (Fig. 2). The HEK293 cells that expressed empty vector did not respond to any of the oligos, suggesting that the response found resulted from mouse TLR9 recognition of specific oligos (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Secretion of IL-8 by HEK293 pcDNA3 (gray bars) and HEK293 mouse-TLR9-YFP (black bars) cells in response to activation with CpG oligos and RpG immunomers at a concentration of 10 μg/ml. Data given are the mean of duplicate measurements ± SD.

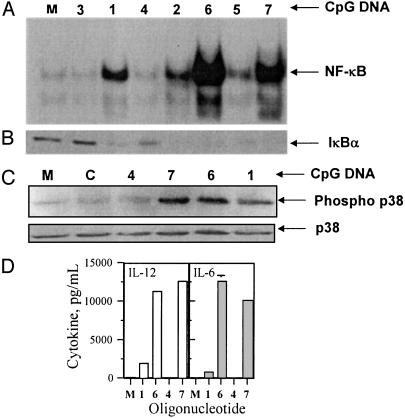

Activation of NF-κB and IκBα in J774 Murine Macrophages. The expected activation of NF-κB was found with mouse-specific oligo 1 (Fig. 3A) and an equal level of activation was observed with RpG oligo 2. In contrast, control oligo 3 containing CpR dinucleotide failed to activate NF-κB. Interestingly, human-specific RpG oligo 5 activated NF-κB in J774 mouse macrophages, whereas its natural CpG counterpart 4 failed completely (Fig. 3A). Mouse-specific RpG immunomer 6 showed potent activation of NF-κB in the same assay. Surprisingly, human-specific 7 also induced equally strong NF-κB activation as that of 6 (Fig. 3A) consistent with mouse spleen cell culture assay data. Fig. 3B shows the status of IκBα in J774 cells upon activation with oligos, which corresponded to the presence or absence of NF-κB in the nucleus.

Fig. 3.

(A) Activation of the transcription factor NF-κB in J774 murine macrophages upon treatment with CpG oligos. J774 cell cultures were treated with PBS (M) or 10 μg/ml 1-7 (lanes as labeled with oligo numbers) for 1 h, and nuclear extracts were isolated, incubated with a 32P-labeled DNA probe containing NF-κB binding sequence, and analyzed by electrophoretic mobility-shift assay. (B) Degradation of IκBα in J774 macrophage cells upon treatment with CpG oligos. J774 cell cultures were treated with PBS (M) or 10 μg/ml oligos 1-7 for 1 h, and cytoplasmic fractions were extracted and analyzed by Western blotting. (C) Phosphorylation of p38 in J774 cells treated with CpG oligos. (D) Induction of cytokine secretion by oligos in J774 macrophage cell cultures. J774 cells were cultured and activated with oligos at various concentrations for 24 h, and the levels of secreted IL-12 and IL-6 in culture medium were measured by ELISA. Data shown are at 1.0 μg/ml concentration of oligos. M, medium-treated control. Each value is an average of three replicates ± SD, and the results are representative of two or three independent experiments.

RpG Oligos Activate p38 Mitogen-Activated Protein Kinase Pathway in J774 Cells. CpG oligo 1 and immunomers 6 and 7 induced phosphorylation of p38 in J774 cells to a similar extent (Fig. 3C). Human-specific CpG oligo 4 and a non-CpG control oligo failed to show a phospho-p38 band (Fig. 3C).

Activation of J774 Cells to Secrete Cytokines. Corresponding to the activation of NF-κB, immunomers 6 and 7 induced high levels of IL-12 and IL-6 production compared with 1 (Fig. 3D), whereas human-specific CpG oligo 4 failed to induce cytokine secretion.

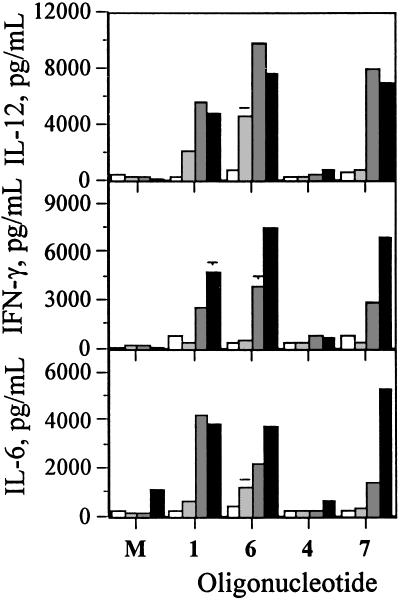

Kinetics of Cytokine Induction. Mouse-specific oligo 1 induced time-dependent IL-12, IFN-γ, and IL-6 secretion from mouse spleen cells, whereas the cytokine levels induced by human-specific oligo 4 were minimal (Fig. 4). Mouse-specific immunomer 6, which contained RpG dinucleotide, induced higher levels of IL-12 and IFN-γ in a time-dependent manner than did 1. Human-specific immunomer 7, which contained RpG dinucleotide, induced levels of IL-12 and IFN-γ similar to or higher than those induced by 1. In general, immunomers 6 and 7 induced less IL-6 but more IL-12 and IFN-γ than did 1 in this assay, in which IL-2 was used as a costimulant (Fig. 4)

Fig. 4.

Time-dependent induction of cytokine secretion by oligos in BALB/c mouse spleen cell cultures. BALB/c mouse spleen cells were cultured, treated with IL-2 at 10 units/ml, and activated with 1.0 μg/ml 1, 4, 6,or 7 for 4, 8, 24, or 48 h (bars from left to right), and the levels of secreted IL-12, IFN-γ, and IL-6 in culture medium were measured by ELISA. Each value is an average of three replicate measurements ± SD, and the results are representative of two independent experiments.

In Vivo Effects of Oligos on Mouse Spleen Weight. A significant increase in spleen weight was observed in mice injected with 1-7, except with control oligo 3, compared with mice injected with PBS (78 ± 12 mg; Table 1). The mice treated with 1, 2, 4, and 5 showed an average increase of 45-72% in their spleen weights compared with the control group. The mice injected with control oligo 3 showed only a 9% increase in spleen weight (Table 1). Both immunomers 6 and 7 containing RpG motif caused ≈72-101% increase in spleen weight at the same dose (Table 1). These in vivo results complement the in vitro spleen-cell culture data.

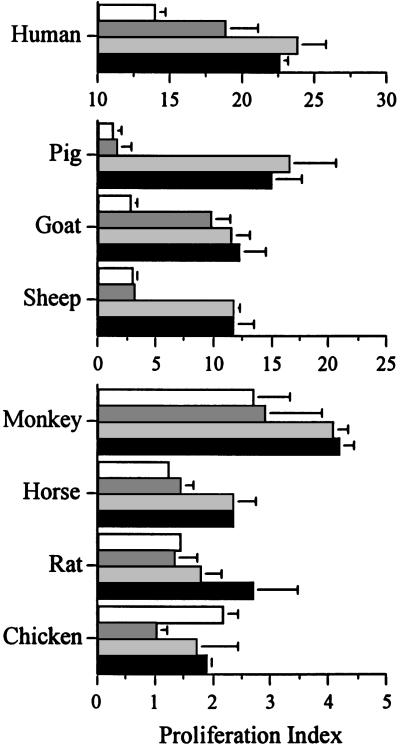

Recognition of RpG Immunomers by Human and Other Vertebrate Species. In the human B cell proliferation assay, human-specific oligo 4 showed greater activity than did mouse-specific oligo 1 (Fig. 5), whereas both RpG-containing immunomers 6 and 7 induced potent B cell proliferation. In addition, immunomers 6 and 7 induced proliferation of PBMCs from other vertebrate species, including cynomolgus monkey, pig, horse, sheep, goat, rat, and chicken (Fig. 5).

Fig. 5.

Proliferation of B cells (human) or PBMCs isolated from the blood obtained from different vertebrate species at a concentration of 1 μg/ml. Each value is an average of three replicates, and the results are representative of one or two independent experiments except in the case of humans. In the case of humans, results shown are representative of six donors. Bars represent oligos 1 (empty), 4 (hatched), 6 (gray), and 7 (black).

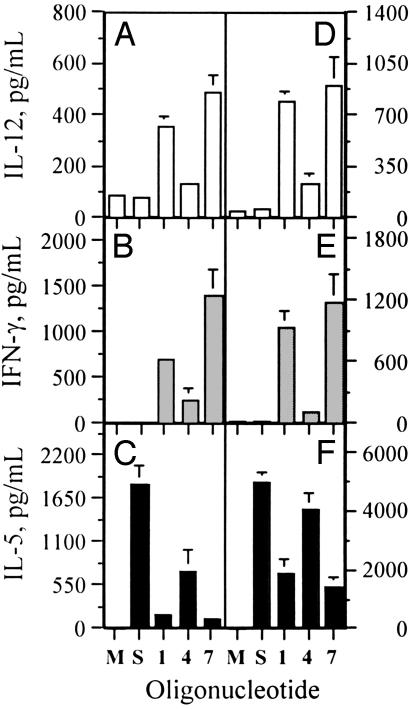

T Helper 1 Cytokine Induction by RpG Immunomer in CA- or Ragweed-Sensitized and Challenged Mouse Spleen Cell Cultures. In cultures not treated with CpG oligo, allergen-sensitized and challenged mouse spleen cells secreted high levels of IL-5 and low levels of IL-12 and IFN-γ, suggesting that T helper 2 cells were mainly activated (Fig. 6). When the allergen-sensitized and challenged mouse spleen cells were treated with oligos and immunomers, a concentration-dependent decrease in IL-5 and increase in IL-12 and IFN-γ secretion was observed (Fig. 5). In these assays, mouse- and human-specific oligos 1 and 4, respectively, showed the expected specificity, whereas immunomer 7 showed higher activity than did 1.

Fig. 6.

Cytokine secretion profiles induced by oligos 1, 4, and 7 in CA-sensitized and challenged BALB/c (A-C) or ragweed allergen-sensitized and challenged AKR/j mouse spleen-cell cultures (D-F) at a concentration of 1.0 μg/ml. Each value is an average of three replicate measurements ± SD. Results are representative of two or three independent experiments. M, media control without allergen treatment of spleen cells; S, allergen-sensitized but not treated with oligos.

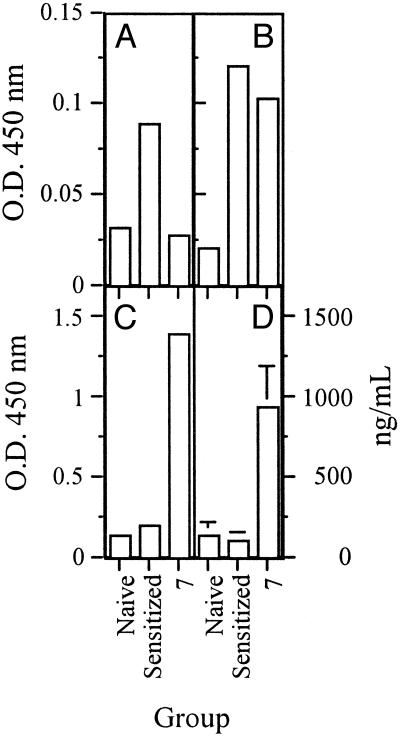

In Vivo Effects of RpG Immunomer on Allergen-Specific Antibody Titers. Mice that received injections of immunomer 7 on the same day as CA was administered produced significantly less CA-specific serum IgE (Fig. 7A) than did CA-sensitized and challenged mice that were not treated with immunomer. Mice treated with immunomer also produced slightly lower levels of CA-specific serum IgG1 (Fig. 7B) and significantly higher CA-specific serum IgG2a levels (Fig. 7C) than did untreated mice. A significant increase in total serum IgG was found in mice treated with immunomer 7 (Fig. 7D), suggesting the potential use of this modification for preventing allergen-induced immune responses in a mouse model.

Fig. 7.

CA-specific serum IgE (A), IgG1 (B), IgG2a (C), and total serum IgG (D) in various treatment groups of BALB/c mice. Naive, mice not sensitized and challenged with CA nor treated with immunomer 7; Sensitized, mice sensitized and challenged with CA but not treated with immunomer 7; 7, mice sensitized and challenged with CA and treated with immunomer 7.

Discussion

In previous studies, immunomers containing a synthetic CpR motif (R = 2′-deoxy-7-deazaguanosine) induced cytokine secretion profiles distinct from those induced by the natural CpG motif (14). Immunomers containing the CpR motif also produced a greater antigen-specific IgG2a/IgG1 antibody ratio than did the CpG motif in in vivo assays. These results suggested that the CpR motif was recognized by the receptor and this recognition resulted in downstream effects different from those produced by the normal CpG motif-containing immunomer (14). The use of the CpR dinucleotide in immunomers had no influence on TLR9 specificity, however, and it was necessary to use different motifs in immunomers containing the CpR dinucleotide for mouse and human systems. In the present study, we showed that TLR9 recognized a bicyclic heterobase (R) (shown in Fig. 1) substituted for cytosine in CpG dinucleotides and induced immune responses.

Activation of TLR9 by CpG oligos triggers stress kinase (28, 29) and NF-κB (30) signaling pathways, leading to the activation of multiple transcription factors, which in turn up-regulate cytokine secretion and expression of cell surface markers. In the present study, treatment of J774 cells with RpG oligos and immunomers led to the activation of NF-κB and phosphorylation of p38 in J774 cells, as occurred also with CpG oligos, suggesting that similar signaling pathways were involved in both cases (Fig. 3). The ability of RpG oligos and immunomers to induce cytokine secretion in lipopolysaccharide-hyporesponsive C3H/HeJ mouse spleen-cell cultures further suggested that these oligos activated the immune system independent of TLR4, which is a receptor for lipopolysaccharide but not CpG or RpG oligos. Direct evidence of TLR9 involvement in RpG immunomer recognition was demonstrated by the activation of 293 cells transfected with mouse TLR9 (Fig. 2). Additionally, comparison of the results measuring the ability of oligos 2 and 3 to activate NF-κB in J774 cells and induce cytokine secretion in mouse spleen-cell cultures suggested that the receptor recognized the RpG motif, but not the CpR motif.

Immunomers containing the RpG motif induced cells to rapidly produce high levels of cytokines compared with conventional linear CpG oligos, as determined in kinetics studies using IL-2 as a costimulator (31). In general, activation of immune cells with RpG immunomers resulted in higher IL-12 and IFN-γ than that occurred with CpG oligos (Fig. 4). Consistent with in vitro data, RpG oligos and immunomers caused spleen enlargement in mice. They also potently reversed allergen-induced T helper 2 responses to T helper 1 responses by inhibiting IL-5 secretion and augmenting secretion of IL-12 and IFN-γ (Fig. 6) (32, 33). Further more, the T helper 1 responses induced by RpG immunomer resulted in increased serum CA-specific IgG2a levels with concomitant decrease in serum IgE levels (Fig. 7).

Mouse and human TLR9 exhibit selectivity for GACGTT and GTCGTT hexameric motifs, respectively (17, 18). In the present study, oligos 1 and 4 selectively activated murine and human immune cells, respectively, confirming the selectivity of TLR9 between species. On the contrary, oligos containing GARGTT and GTRGTT motifs activated NF-κB in J774 cells and induced cytokine production in both mouse and human cell cultures to a similar extent. In contrast to CpG oligos, immunomers containing the RpG dinucleotide in mouse- and human-specific motifs were recognized to a similar extent by mouse TLR9 in HEK293 cells (Fig. 2). Additionally, RpG immunomers induced potent proliferation of PBMCs obtained from a number of vertebrate species (Fig. 5). Taken together, these data suggest that TLR9 from different species recognized the RpG motif without selectivity for the flanking sequences. We show that a synthetic nucleotide motif could overcome species-dependent TLR9 sequence selectivity.

In conclusion, we have demonstrated that a bicyclic heterobase substituted for deoxycytidine in a CpG dinucleotide, referred to as RpG, was recognized by murine, human, and several other vertebrate immune cells. The recognition was TLR9 specific and resulted in the activation of the same signaling pathways as in the case of CpG oligos. Importantly, immunomers containing RpG dinucleotide were recognized by immune cells of a range of animal species without discrimination for GARGTT and GTRGTT motifs. Universal recognition of this motif is a significant advancement in rapidly bringing these compounds to clinical trials without having to change the sequences for testing in different animal species. The receptor, TLR9, alone or in conjunction with other receptors, recognized CpG (1-7), YpG (34), CpR (14, 34), and the present RpG dinucleotides, suggesting that the receptor was able to modulate downstream cytokine secretion profiles depending on the structure of the nucleotide motif. These studies also suggest the nucleotide motif recognition pattern of TLR9 and the ability to modulate cytokine secretion profiles by using these synthetic agonists of TLR9.

Supplementary Material

Abbreviations: TLR, Toll-like receptor; CA, conalbumin; PBMC, peripheral blood mononuclear cell.

References

- 1.Yamamoto, S., Yamamoto, T., Nojima, Y., Umemori, K., Phalen, S., McMurray, D. N., Kuramoto, E., Iho, S., Takauji, R., Sato, Y., et al. (2002) Jpn. J. Infect. Dis. 55, 37-44. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Krieg, A. M. (2002) Annu. Rev. Immunol., 20, 709-760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pisetsky, D. S. (2000) Springer Semin. Immunopathol. 22, 21-23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dalpke, A., Zimmermann, S. & Heeg, K. (2002) Biol. Chem. 383, 1491-1500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kandimalla, E. R., Zhu, F.-G., Bhagat, L., Yu, D. & Agrawal, S. (2003) Biochem. Soc. Trans. 31, 654-658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hemmi, H., Takeuchi, O., Kawai, T., Kaisho, T., Sato, S., Sanjo, H., Matsumoto, M., Hoshino, K., Wagner, H., Takeda, K. & Akira, S. (2000) Nature 408, 740-745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Krieg, A. M., Yi, A. K., Matson, S., Waldschmidt, T. J., Bishop, G. A., Teasdale, R., Koretzky, G. A. & Klinman, D. M. (1995) Nature 374, 546-549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Klinman, D. M., Yi, A. K., Beaucage, S. L., Conover, J. & Krieg, A. M. (1996) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 96, 2285-2290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zhao, Q., Temsamani, J., Zhou, R. Z. & Agrawal, S. (1997) Antisense Nucleic Acid Drug Dev. 7, 495-502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Agrawal, S. & Kandimalla, E. R. (2002) Trends Mol. Med. 8, 114-121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yu, D., Zhao, Q., Kandimalla, E. R. & Agrawal, S. (2000) Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 10, 2585-2588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kandimalla, E. R., Bhagat, L., Yu, D., Cong, Y., Tang, J. & Agrawal, S. (2002) Bioconjugate Chem. 13, 966-974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yu, D., Kandimalla, E. R., Bhagat, L., Tang, J. Y., Cong, Y., Tang, J. & Agrawal, S. (2002) Nucleic Acids Res. 30, 4460-4469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kandimalla, E. R., Bhagat, L., Wang, D., Yu, D., Tang, J., Wang, H., Huang, P., Zhang, R. & Agrawal, S. (2003) Nucleic Acids Res. 31, 2393-2400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yu, D., Zhu, F. G., Bhagat, L., Wang, H., Kandimalla, E. R., Zhang, R. & Agrawal, S. (2002) Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 297, 83-90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bhagat, L., Zhu, F. G., Yu, D., Tang, J., Wang, H., Kandimalla, E. R., Zhang, R. & Agrawal, S. (2003) Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 300, 853-861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hartmann, G., Weeratna, R. D., Ballas, Z. K., Payette, P., Blackwell, S., Suparto, I., Rasmussen, W. L., Waldschmidt, M., Sajuthi, D., Purcell, R. H., et al. (2000) J. Immunol. 164, 1617-1624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bauer, S., Kirschning, C. J., Hacker, H., Redecke, V., Hausmann, S., Akira, S., Wagner, H. & Lipford, G. B. (2001) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 98, 9237-9242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.vanUden, J. & Raz, E. (2000) Springer Semin. Immunopathol. 22, 1-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zhao, Q., Temsamani, J., Iadarola, P. L., Jiang, Z. & Agrawal, S. (1996) Biochem Pharmacol. 51, 173-182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Branda, R. F., Moore, A. L., Mathews, L., McCormack, J. J. & Zon, G. (1993) Biochem. Pharmacol. 45, 2037-2043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Woo, J., Meyer, R. B., Jr., & Gamper, H. B. (1996) Nucleic Acids Res. 24, 2470-2475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Agrawal, S. & Kandimalla, E. R. (2001) Curr. Cancer Drug Targets 1, 197-209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yu, D., Kandimalla, E. R., Zhao, Q., Cong, Y. & Agrawal, S. (2001) Bioorg. Med. Chem. 9, 2803-2808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yu, D., Kandimalla, E. R., Zhao, Q., Cong, Y. & Agrawal, S. (2001) Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 11, 2263-2267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yu, D., Kandimalla, E. R., Zhao, Q., Bhagat, L., Cong, Y. & Agrawal, S. (2003) Bioorg. Med. Chem. 11, 459-464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yu, D., Kandimalla, E. R., Cong, Y., Tang, J., Tang, J. Y., Zhao, Q. & Agrawal, S. (2002) J. Med. Chem. 45, 4540-4548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yi, A. K. & Krieg, A. M. (1998) J. Immunol. 161, 4493-4497. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Choudhury, B. K., Wild, J. S., Alam, R., Klinman, D. M., Boldogh, I., Dharajiya, N., Mileski, W. J. & Sur, S. (2002) J. Immunol. 169, 5955-5961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Stacey, K. J., Sweet, M. J. & Hume, D. A. (1996) J. Immunol. 157, 2116-2122. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Decker, T., Schneller, F., Kronschnabl, M., Dechow, T., Lipford, G. B., Wagner, H. & Peschel, C. (2000) Exp. Hematol. 28, 558-568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Silverman, E. S. & Drazen, J. M. (2003) Am. J. Respir. Cell Mol. Biol. 28, 645-647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Serebrisky, D., Teper, A. A., Huang, C. K., Lee, S. Y., Zhang, T. F., Schofield, B. H., Kattan, M., Sampson, H. A. & Li, X. M. (2000) J. Immunol. 165, 5906-5912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kandimalla, E. R., Yu, D., Zhao, Q. & Agrawal, S. (2001) Bioorg. Med. Chem. 9, 807-813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.