Abstract

We have investigated expression of vitamin D receptor (VDR) and peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors (PPAR)α, δ, γ in primary cultured normal melanocytes (NHM), melanoma cell lines (MeWo, SK-Mel-5, SK-Mel-25, SK-Mel-28), a cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma cell line (SCL-1) and an immortalized sebocyte cell line (SZ95). LNCaP prostate cancer cells, MCF-7 breast cancer cells and embryonic kidney cells (HEK-293) were used as controls. VDR and PPAR mRNA were detected, quantitated and compared in these cell lines using real-time quantitative polymerase chain reaction (RTqPCR). The expression patterns of these nuclear receptors (NRs) varied strongly between the different cell lines according to their origin. PPARδ and PPARγ were less strongly expressed in the melanoma cell lines and in the other skin-derived cell lines as compared to the control cell lines. PPARα and VDR were stronger expressed in the 1,25(OH)2D3-sensitive melanoma cells (MeWo and in SK-Mel-28) than in the 1,25(OH)2D3-resistent melanoma cell lines (SK-Mel-5 and SK-Mel-25) or in NHM. Interestingly, VDR expression was increased by the treatment with 1,25(OH)2D3 in 1,25(OH)2D3-sensitive melanoma cells but not in 1,25(OH)2D3-resistent melanoma cell lines. 1,25(OH)2D3 increased the expression of PPARα in almost all cell lines analyzed. Our results indicate a cross-talk between VDR- and PPAR-signaling pathways in various cell types including melanoma cells. Further investigations are required to investigate the physiological and pathophysiological relevance of this cross-talk. Because VDRand PPAR-signaling pathways regulate a multitude of genes that are of importance for a multitude of cellular functions including cell proliferation, cell differentiation, immune responses and apoptosis, the provided link between VDR and PPAR may open important new perspectives for treatment and prevention of melanoma and other diseases.

Key words: nuclear receptors, skin, malignant melanoma, peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors, PPAR, vitamin D receptor, VDR

Introduction

As the outermost layer of the skin, the epidermis offers protection against bacterial and viral infections, or mechanical and chemical aggressions. It is a multistratified epithelium. Progenitor undifferentiated keratinocytes which migrate from basal to the uppermost layer undergo a vectorial differentiation. This program includes a biochemical differentiation, the sequential expression of various structural proteins (e.g., keratins, involucrin and loricrin), and the processing and reorganization of lipids (e.g., sterols, free fatty acids and sphingolipids), which provide a hydrophobic barrier to the body.1 By their diverse biological activities on keratinocytes and other skin cells, nuclear receptors (NRs) like peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors (PPARs) or like the vitamin D receptor (VDR) represent a major research target for the understanding and treatment of many skin diseases.2

Since their discovery in the early 1990s it has become clear that PPARs are ligand-activated transcription factors that are involved in the genetic regulation of complex pathways of mammalian metabolism, including fatty acid oxidation and lipogenesis. Later these receptors have been shown to be implicated also in cellular proliferation, differentiation, tumor promotion, apoptosis and immune reaction/inflammation.3 Three genetically and functionally distinct PPAR isoforms have been described: PPARα (NR1C1), PPARβ or PPARδ (also named NR1C2, FAAR or NUC1) and PPARγ (NR1C3). All three PPARs are adopted orphan nuclear hormone receptors4–6 and exhibit distinct patterns of tissue distribution,7 differ in their ligand-binding domains. Of the three PPARs, PPARδ represents the receptor, that is widely expressed in a wide range of tissues and cells, with relatively higher levels of expression noted in skin, brain, adipose, kidney, heart and digestive tract, suggesting possible developmental or physiological roles in these tissues.8–12 PPARγ is expressed at high levels in adipose tissue, and is an important regulator of adipocyte differentiation and lipid metabolism.13–15 The highest PPARα expression was shown in the liver,16 and in tissues with high fatty acid catabolism such as the kidney, heart, skeletal muscle and brown fat.9,17,18 In human epidermis not only all three types of PPARs were detected, but also the VDR.

After activation through a ligand the conformation of NRs like PPARs and VDR is altered and stabilized, resulting in the creation of a binding cleft and recruitment of transcriptional coactivators. After activation, PPARs and VDR form heterodimers with the retinoid-X receptor (RXR). These heterodimers preferentially bind to specific response elements, named peroxisome proliferator response elements (PPREs) or vitamin D response elements (VDREs), respectively, that are situated in enhancer sites of regulated target genes and regulates gene expression. VDRE have been reported in the proximal promoter of a number of vitamin D-responding genes including the human vitamin D 24-hydroxylase (CYP24).19,20 The CYP24 gene is more than 10,000-fold induced by 1,25(OH)2D3 (1α,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3, calcitriol), the biologically most active natural vitamin D metabolite, and represents the most responsive primary 1,25(OH)2D3 target gene.21 In contrast, most other known primary target genes of 1,25(OH)2D3 appear to be much less responsive and often show a physiological relevant inducibility of two-fold or less after treatment with 1,25(OH)2D3.22,23

Recent published data show that, in the breast cancer cell line MCF-7, 1,25(OH)2D3 regulates PPARδ-expression by binding to a potent DR3-type VDRE only 350 bp upstream of the transcription start site of the PPARδ gene.24 Dunlop et al.24 demonstrated that in MCF-7 and in the prostate cancer line PC-3, VDR- and PPARδ-signaling pathways are connected at the level of cross-regulation of their respective transcription factor mRNA levels. Recently, we demonstrated a putative cross-talk between the signaling pathways of PPARδ and VDR in MeWo melanoma cells.25 In addition, we found hints for a similar cross-regulation between the signaling pathways of PPARα and VDR in MeWo cells.25

As a step further in improving our understanding of the relevance of nuclear receptors for skin physiology and pathophysiology, we now investigated expression of VDR and PPARs in primary cultured normal melanocytes (NHM), melanoma cell lines (MeWo, SK-Mel-5, SK-Mel-25, SK-Mel-28), a cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma cell line (SCL-1) and an immortalized sebocyte cell line (SZ95). LNCaP prostate cancer cells, MCF-7 breast cancer cells, hepatoblastoma cells (HepG2), and embryonic kidney cells (HEK-293) were used as controls.

Results

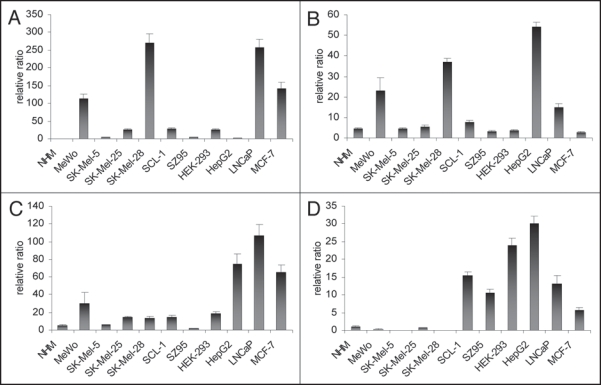

VDR and PPARα, δ are expressed in all skin-derived cell lines. First, we examined mRNA expression of the three PPAR subtypes and of VDR in all cell lines without any treatment using RTqPCR. Figure 1A-C show that the VDR, PPARα and PPARδ are expressed in all cell lines analyzed. In general, VDR expression was stronger in melanoma cell lines as compared to NHM. SK-Mel-28 and MeWo revealed higher levels of VDR expression than SK-Mel-5 and SK-Mel-25 (Fig. 1A). Among the cell lines not derived from skin, LNCaP and MCF-7 showed strong VDR expression (Fig. 1A). Similar to VDR expression, the PPARα expression was stronger in the melanoma cell lines MeWo and SK-Mel-28 compared to the two other melanoma cell lines and the other skin-derived cell lines (Fig. 1B). The expression of PPARα and PPARγ varied slightly between NHM and the individual melanoma cell lines (Fig. 1C and D). Moreover, in the skin-derived cell lines (above all in the melanoma cell lines), PPARδ and PPARγ were not as strongly expressed as in the cell lines not derived from skin. In SK-Mel-5 and SK-Mel-28 cells, the expression of PPARγ could not been detected. HepG2 showed strongest expression of all PPARs as compared to other cell lines analyzed. HepG2 cells revealed a relatively low VDR expression combined with a very high expression of CYP24 (data not shown). This gene expression pattern indicates that HepG2 cells inactivate 1,25(OH)2D3 very quickly, indicating that a redosing with 1,25(OH)2D3 every 48 h would be ineffective. Therefore we renounced on a treatment of HepG2 cells with 1,25(OH)2D3. All the other the cell lines were treated with 1,25(OH)2D3 in a concentration of 10−8 M in order to find hints for a cross-talk between the signaling pathways of PPARδ and VDR.

Figure 1.

(A) VDR expression without treatment after 120 h of cell culture in melanoma cell lines (MeWo, SK-Mel-5, SK-Mel-25, SK-Mel-28) compared to NHM, SCL-1, SZ95 and cell lines not deriving from skin (HEK-293, HepG2, LNCaP, MCF-7) measured with RTqPCR. (B) PPARα expression without treatment after 120 h of cell culture in melanoma cell lines (MeWo, SK-Mel-5, SK-Mel-25, SK-Mel-28) compared to NHM, SCL-1, SZ95 and cell lines not deriving from skin (HEK-293, HepG2, LNCaP, MCF-7) measured with RTqPCR. (C) PPARδ expression without treatment after 120 h of cell culture in melanoma cell lines (MeWo, SK-Mel-5, SK-Mel-25, SK-Mel-28) compared to NHM, SCL-1, SZ95 and cell lines not deriving from skin (HEK-293, HepG2, LNCaP, MCF-7) measured with RTqPCR. (D) PPARγ expression without treatment after 120 h of cell culture in melanoma cell lines (MeWo, SK-Mel-5, SK-Mel-25, SK-Mel-28) compared to NHM, SCL-1, SZ95 and cell lines not deriving from skin (HEK-293, HepG2, LNCaP, MCF-7) measured with RTqPCR.

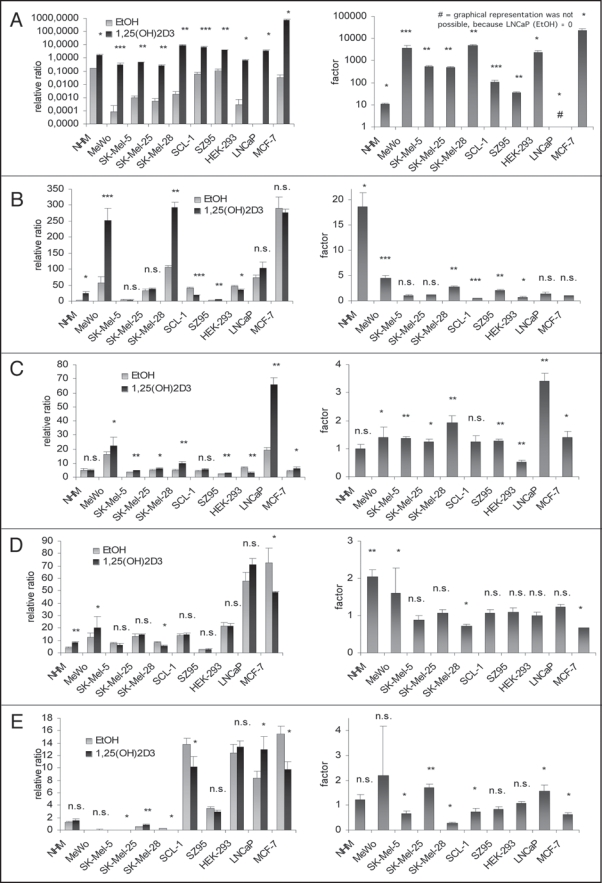

1,25(OH)2D3 treatment increases VDR expression in melanoma cell lines MeWo and SK-Mel-28. We treated NHM, melanoma cell lines (MeWo, SK-Mel-5, SK-Mel-25, SK-Mel-28), SCL-1, SZ95, HEK-293, LNCaP and MCF-7 with 1,25(OH)2D3 (10−8 M) over 120 h and quantified RNA expression using RTqPCR-technology. As a control for the effectiveness of the cell treatment we analyzed the expression of the CYP24 gene, the most responsive primary 1,25(OH)2D3 target gene. In all treated cell lines 1,25(OH)2D3 induced significantly the expression of CYP24 (Fig. 2A). Expression of VDR was not in all cell lines increased after 1,25(OH)2D3 treatment (Fig. 2B). NHM, SZ95 and above all the melanoma cell lines MeWo and SK-Mel-28 showed an increase in VDR expression (NHM: 18-fold, p < 0.05; SZ95: 2-fold, p < 0.005; MeWo: 4.5-fold, p < 0.0005; SK-Mel-28: 3-fold, p < 0.005). In contrast, 1,25(OH)2D3 had no effect on VDR expression in the melanoma cell lines SK-Mel-5 and SK-Mel-25. In accordance with this, induction of CYP24 expression was less pronounced in SK-Mel-5 and SK-Mel-25 (about 1,000-fold; p < 0.005) as compared to MeWo and SK-Mel-28 (about 10,000-fold; MeWo: p < 0.0005, SK-Mel-28: p < 0.005) (Fig. 2A).

Figure 2.

(see previos page). (A) Relative ratios (left) and changes (right) of CYP24A1 expression after 120 h 1,25(OH)2D3 treatment (black) compared to control (grey) in melanoma cell lines (MeWo, SK-Mel-5, SK-Mel-25, SKMel-28), NHM, SCL-1, SZ95 and cell lines not deriving from skin (HEK-293, LNCaP, MCF-7) (*p ≤ 0.05; **p ≤ 0.005; ***p ≤ 0.0005) measured with RTqPCR. (B) relative ratios (left) and changes (right) of VDR expression after 120 h 1,25(OH)2D3 treatment (black) compared to control (grey) in melanoma cell lines (MeWo, SK-Mel-5, SK-Mel-25, SKMel-28), NHM, SCL-1, SZ95 and cell lines not deriving from skin (HEK-293, LNCaP, MCF-7) (n.s. >0.05; *p ≤ 0.05; **p ≤ 0.005; ***p ≤ 0.0005) measured with RTqPCR. (C) relative ratios (left) and changes (right) of PPARγ expression after 120 h 1,25(OH)2D3 treatment (black) compared to control (grey) in melanoma cell lines (MeWo, SK-Mel-5, SK-Mel-25, SKMel-28), NHM, SCL-1, SZ95 and cell lines not deriving from skin (HEK-293, LNCaP, MCF-7) (n.s. >0.05; *p ≤ 0.05; **p ≤ 0.005) measured with RTqPCR. (D) relative ratios (left) and changes (right) of PPARγ expression after 120 h 1,25(OH)2D3 treatment (black) compared to control (grey) in melanoma cell lines (MeWo, SK-Mel-5, SK-Mel-25, SKMel-28), NHM, SCL-1, SZ95 and cell lines not deriving from skin (HEK-293, LNCaP, MCF-7) (n.s. >0.05; *p ≤ 0.05; **p ≤ 0.005) measured with RTqPCR. (E) relative ratios (left) and changes (right) of PPARδ expression after 120 h 1,25(OH)2D3 treatment (black) compared to control (grey) in melanoma cell lines (MeWo, SK-Mel-5, SK-Mel-25, SKMel-28), NHM, SCL-1, SZ95 and cell lines not deriving from skin (HEK-293, LNCaP, MCF-7) (n.s. >0.05; *p ≤ 0.05; **p ≤ 0.005) measured with RTqPCR.

1,25(OH)2D3 treatment increased PPARα expression in all melanoma cell lines.

The PPARα expression after 120 h of 1,25(OH)2D3 treatment was analyzed in the different cell lines using RTqPCR (Fig. 2C). We show that treatment with 1,25(OH)2D3 increases PPARα expression in all melanoma cell lines (MeWo and SK-Mel-25: about 1.5-fold, p < 0.05; SK-Mel-5: about 1.5-fold, p < 0.005; SK-Mel-28: about 2-fold, p < 0.005). A significant increase of the PPARα expression was also observed in SZ95 (about 1.5-fold, p < 0.005), LNCaP (about 3.5-fold, p < 0.005) and MCF-7 (about 1.5-fold, p < 0.05). In NHM, PPARα expression was not modulated by 1,25(OH)2D3.

1,25(OH)2D3 treatment increased PPARδ expression in MeWo and NHM.

Using RTqPCR we analyzed PPARδ expression in the different cell lines after 120 h of 1,25(OH)2D3 treatment (Fig. 2D). 1,25(OH)2D3 increased the PPARδ expression only in MeWo (1.5-fold, p < 0.05) and in NHM (2-fold, p < 0.005). In SK-Mel-28 and in MCF-7 the PPARδ expression was even lower after 120 h of 1,25(OH)2D3 treatment as compared to the vehicle (EtOH)-treated controls.

PPARγ expression after 1,25(OH)2D3 treatment in melanoma cell lines.

Like PPARα and PPARδ, the third PPAR subtype, PPARγ was analyzed after 120 h of 1,25(OH)2D3 treatment using RTqPCR technology (Fig. 2E). According to the cell line analyzed, PPARγ expression was increased (SK-Mel-25, LNCaP) or decreased (SK-Mel-5, SK-Mel-28, SCL-1, MCF-7). The treatment with 1,25(OH)2D3 did not increase the very low PPARγ expression in most melanoma cell lines analyzed.

Discussion

In the present study, we compared for the first time PPAR and VDR mRNA expression in different melanoma cell lines, in other skin derived cell lines, and in cell lines not derived from the skin. LightCycler-based RTqPCR was chosen to detect and quantitate NR expression because of its broad dynamic range of detection, quantitative reliability, and reproducibility. We showed that PPAR and VDR expression varied strongly between the different cell lines according to their origin. In addition to this, cell lines expressing the PPARs at high levels not necessarily expressed the VDR strongly. This confirms a recently published paper, subdividing the NRs into several clades, depending upon tissue-specific expression patterns.26 This classification may reflect shared responsibility in coordinating the transcriptional programs necessary to execute idiotypic physiological pathways within any given tissue or organ. VDR and PPARs were assigned to a distinct cluster of NRs.26 Studying the expression profile of NRs in different cell lines offers a simple, powerful way to obtain highly related information about their physiological functions as individual proteins.

We show that melanoma cell lines and other skin-derived cell lines express PPARδ and PPARγ less strongly as compared to the cell lines not deriving from skin that we analyzed. The cell line HepG2 deriving from liver, one of the organs playing an important role in lipid and glucose metabolism, expresses high levels of PPARs. Interestingly, in our study the melanoma cell lines MeWo and SK-Mel-28 strongly expressed PPARα. These results are in agreement with recently published data, showing high levels of mRNA and protein expression in human melanoma cell lines compared to NHM.27 In addition, we show that PPARα and VDR are stronger expressed in MeWo and SK-Mel-28 than in SK-Mel-5 and SK-Mel-25 or in NHM. Thus, VDR expression in these cells correlates with their sensitivity to the antiproliferative effects of 1,25(OH)2D3.28 Analysing cell proliferation, Reichrath et al.29 identified the existence of 1,25(OH)2D3-sensitive (MeWo and SK-Mel-28) and 1,25(OH)2D3-resistent melanoma cell lines (SK-Mel-5 and SK-Mel-25). The present study showes that 1,25(OH)2D3 treatment induces VDR expression in 1,25(OH)2D3-sensitive cell lines (MeWo and SK-Mel-28) but had no effect in SK-Mel-5 and SK-Mel-25. In addition to this, expression of the CYP24 gene, the most responsive primary 1,25(OH)2D3 target gene, was increased after treatment with 1,25(OH)2D3 about 10 times stronger in the 1,25(OH)2D3-sensitive melanoma cell lines than in the 1,25(OH)2D3-resistent melanoma cell lines. These increases of VDR and CYP24 expression can be explained by the presence of at least one VDRE in enhancer sites of target genes.30,31 In our study, treatment with 1,25(OH)2D3 did not increase VDR expression in all cell lines analyzed. The regulation of the expression of 1,25(OH)2D3 target genes is very complex and not only depends on the type of VDRE but also on a multitude of coactivators and corepressors or on other unknown mechanisms.31

In a recent study, Dunlop et al.24 revealed a potent VDRE in the human PPARδ promoter. It was demonstrated that PPARδ is a primary 1,25(OH)2D3-responding gene and that VDR and PPARδ signalling pathways are interconnected at the level of cross-regulation of their respective transcription factor mRNA levels.24

We here show that treatment with 1,25(OH)2D3 increases the expression of PPARα in all analyzed melanoma cell lines, but also in a part of the other cell lines. PPARα having no known VDRE in its promoter does not belong to the known primary target genes of 1,25(OH)2D3. It can be speculated whether the increase in PPARα expression after treatment with 1,25(OH)2D3 may be induced via indirect mechanisms.

It is well known that signaling pathways of a large number of NRs are interconnected. The present study suggests that VDR and PPARα are co-expressed in melanoma cell lines. Our findings indicate a cross-talk between VDR- and PPARα-signaling pathways that is of importance for the ability of these NRs to modulate gene expression. Moreover, since both the VDR and PPAR compete for their predominant heterodimerisation partner, RXR, complex transcriptional regulation of target genes may be expected when these NRs are activated. Considering the enormous number of direct and indirect target genes of VDR and PPARs, it is tempting to speculate that these NRs may modulate proliferation and differentiation of normal and malignant melanocytes via various mechanisms. 1,25(OH)2D3 exerts a significant inhibitory effect on the G1/S checkpoint of the cell cycle by upregulating the cyclin dependent kinase inhibitors p27 and p21, and by inhibiting cyclin D1.28 Beside the growth regulation of cells, 1,25(OH)2D3 also has an effect on tumor invasion, angiogenesis and metastastic behavior in various malignancies.28,32–35 It has been demonstrated that treatment with several PPAR ligands inhibits cell proliferation in melanoma cells and in other cell lines.3 In addition to this, PPARα activation by corresponding ligands decreases the metastatic potential both in B16F10 mouse melanoma cells and in human SkMel188 cells in vitro via downregulation of Akt signaling.36 Activation of PPAR signaling pathways by 1,25(OH)2D3 or other vitamin D ligands may open new perspectives for treatment or prevention of malignant melanoma.

In summary, we showed that the expression patterns of VDR and PPARs differ in individual cell lines according to their origin. Our results suggest that the signaling pathways of the VDR and the PPARs are interconnected not only in melanoma cell lines but also in a large number of other cell lines. This cross-talk involves the presence of VDR- and PPAR-response elements and a competition for the same heterodimerisation partner, RXR. However, the complete mechanisms of this cross-talk between the VDR and PPAR signaling pathways are not yet known. Further investigations are required to evaluate the physiological and pathophysiological relevance of this cross-talk. The signaling pathways of PPARs and VDR regulate a multitude of genes that are of importance for various cellular functions including cell proliferation, cell differentiation, immune responses and apoptosis. The findings of this study may therefore open new perspectives for treatment and/or prevention of melanoma and other diseases.

Materials and Methods

Cell culture. All cell lines were seeded into culture dishes (10 cm in diameter) (Greiner, Frickenhausen, Germany) and cultivated at 37°C. The human melanoma cell lines (MeWo, SK-Mel-5, SK-Mel-25, SK-Mel-28) and the cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma cell line (SCL-1) were cultivated in Roswell Park Memorial Institute 1640 medium (RPMI) (10% fetal calf serum (FCS), 1% L-Glutamin, 1% penicillin/streptomycin, 37°C, 5% CO2). LNCaP prostate cancer cells were also grown in RPMI, but supplemented with 5% FCS. The immortalized sebocyte cell line SZ95 were cultivated using Sebomed medium (10% FCS, 0.002% epidermal growth factor, 1% penicillin/streptomycin, 37°C, 5% CO2). The primary cultured normal melanocytes (NHM) were grown in melanocyte growth medium and supplemented with 0.4% bovine pituitary extract, 1 ng/ml basic fibroblast growth factor, 5 µg/ml insulin, 0.5 µg/ml hydrocortison, 10 ng/ml PMA, 1% penicillin/streptomycin and 0.05% amphotericin B. The hepatoblastoma cells (HepG2), the breast cancer cells (MCF-7) and the embryonic kidney cells (HEK-293) were cultivated in Dulbecco’s modified eagle’s medium (DMEM) (10% FCS, 1% L-Glutamin, 1% penicillin/streptomycin, 37°C, 5% CO2). Semi-confluent cells were incubated with or without 1,25(OH)2D3 over 120 h in a concentration of 10−8 M. 1,25(OH)2D3 was redosed every 48 h. Treatment of cells with vehicle (ethanol) alone served as control. 1,25(OH)2D3 was purchased from Sigma (Taufkirchen, Germany). The concentration of 1,25(OH)2D3 (10−8 M) was choosen because we had found in previous experiments that this concentration is highly effective in inducing genomic effects in melanoma cells35 without exerting toxic effects.

RNA isolation.

RNA isolation was carried out with RNeasy Kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany) according to the manufacturers manual. RTqPCR reactions were carried out with Omniscript RT Kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany), using Oligo-dT-primers and 2 µg mRNA per reaction as a template.

Quantitative real time PCR (RTqPCR) and analysis.

Expression of the human VDR, CYP24 and the PPAR isotype genes was analyzed in MeWo cells using RTqPCR (60 cycles in LightCycler, Roche Molecular Biochemicals, Mannheim, Germany) and genespecific primers from Qiagen (Hilden, Germany) and TIB Molbiol (Berlin, Germany) (Table 1). In order to calculate the normalized ratio, the relative amount of target gene (VDR, CYP24 and the PPARs) and a reference gene (β2-microglobulin) was determined for each sample and one calibrator, integrated into each LightCycler run. The relative ratio of target to reference for each sample and for the calibrator was first calculated to correct for sample-to-sample variations caused by differences in the initial quality and quantity of the nucleic acid (Roche, technical note LC 13/2001). The target/reference ratio of each sample was then divided by the target/reference ratio of the calibrator using relative quantification software (Roche Relquant). This second step normalized different detection sensitivities of target and reference amplicons. Thus the normalization to a calibrator provided a constant calibrator point between PCR runs. Each sample was analyzed in quadruplicate; final values were expressed as median of N-fold differences in target gene expression in treated samples relative to the control samples.

Table 1.

Gene-specific primers used in RTqPCR

| Primer | Sequence | Source |

| PPARα | QuantiTect Primer Assay (QT00017451) | Qiagen |

| PPARδ | QuantiTect Primer Assay (QT00078064) | Qiagen |

| PPARγ | QuantiTect Primer Assay (QT00029841) | Qiagen |

| VDR (forward) | 5′-CCA GTT CGT GTG AAT GAT GG-3′ | TIB Molbiol |

| VDR (reverse) | 5′-GTC GTC CAT GGT GAA GGA-3′ | |

| CYP24 (forward) | 5′-GCA GCC TAG TGC AGA TTT-3′ | TIB Molbiol |

| CYP24 (reverse) | 5′-ATT CAC CCA GAA CTG TTG-3′ | |

| β2 μglobulin (forward) | 5′-CCA GCA GAG AAT GGA AAG TC-3′ | TIB Molbiol |

| β2 μglobulin (reverse) | 5′-GAT GCT GCT TAC ATG TCT CG-3′ |

Statistical analysis.

All data are presented as mean ± standard deviation for at least three experiments. Statistical significance was calculated by the Student’s t-test. Mean differences were considered to be significant when p < 0.05 (*), decisive (highly significant) when p < 0.005 (**), and conclusive when p < 0.0005 (***).

Abbreviations

- 1,25(OH)2D3

1α,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3, calcitriol

- bp

base pairs

- DMEM

dulbecco’s modified eagle’s medium

- EtOH

ethanol

- FCS

fetal calf serum

- h

hours

- M

molar

- mRNA

messenger ribonucleic acid

- NHM

primary cultured normal melanocytes

- NR

nuclear receptor

- PBS

phosphate buffered saline

- PPAR

peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor

- PPRE

peroxisome proliferator response element

- RPMI

roswell park memorial institute 1640 medium

- RTqPCR

real-time quantitative polymerase chain reaction

- RXR

retinoid-X receptor

- VDR

vitamin D receptor

- VDRE

vitamin D response element

Footnotes

Previously published online as a Dermato-Endocrinology E-publication: http://www.landesbioscience.com/journals/dermatoendocrinology/article/9629

References

- 1.Wahli W. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors (PPARs): from metabolic control to epidermal wound healing. Swiss Med Wkly. 2002;132:83–91. doi: 10.4414/smw.2002.09939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sertznig P, Seifert M, Tilgen W, Reichrath J. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors (PPARs) and the human skin. Importance of PPARs in Skin Physiology and Dermatologic Diseases. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2008;9:15–31. doi: 10.2165/00128071-200809010-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sertznig P, Seifert M, Tilgen W, Reichrath J. Present concepts and future outlook: Function of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors (PPARs) for pathogenesis, progression and therapy of cancer. J Cell Physiol. 2007;212:1–12. doi: 10.1002/jcp.20998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Desvergne B, Wahli W. PPAR: a key nuclear factor innutrient/gene interactions? In: Bauerle P, editor. Inducible Transcription. Vol. 1. Birkhäuser: Boston,; 1995. pp. 142–176. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wahli W, Braissant O, Desvergne B. Peroxisome proliferator activated receptors: transcriptional regulators of adipogenesis, lipid metabolism and more…. Chem Biol. 1995;2:261–266. doi: 10.1016/1074-5521(95)90045-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chawla A, Repa JJ, Evans RM, Mangelsdorf DJ. Nuclear receptors and lipid physiology: opening the X-files. Science. 2001;294:1866–1870. doi: 10.1126/science.294.5548.1866. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Escher P, Wahli W. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors: insight into multiple cellular functions. Mutat Res. 2000;448:121–138. doi: 10.1016/s0027-5107(99)00231-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Amri EZ, Bonino F, Ailhaud G, Abumrad NA, Grimaldi PA. Cloning of a protein that mediates transcriptional effects of fatty acids in preadipocytes. Homology to peroxisome proliferators-activated receptors. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:2367–2371. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.5.2367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Braissant O, Foufelle F, Scotto C, Dauca M, Wahli W. Differential expression of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors (PPARs): tissue distribution of PPARalpha, beta and gamma in the adult rat. Endocrinology. 1996;137:354–366. doi: 10.1210/endo.137.1.8536636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Desvergne B, Wahli W. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors: Nuclear control of metabolism. Endocr Rev. 1999;20:649–688. doi: 10.1210/edrv.20.5.0380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Michalik L, Desvergne B, Basu-Modak S, Tan NS, Wahli W. Nuclear hormone receptors and mouse skin homeostasis: implication of PPARbeta. Horm Res. 2000;54:263–268. doi: 10.1159/000053269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Escher P, Braissant O, Basu-Modak S, Michalik L, Wahli W, Desvergne B. Rat PPARs: quantitative analysis in adult rat tissues and regulation in fasting and refeeding. Endocrinology. 2001;142:4195–4202. doi: 10.1210/endo.142.10.8458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chawla A, Schwarz EJ, Dimaculangan DD, Lazar MA. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor (PPAR)gamma: adipose-predominant expression and induction early in adipocyte differentiation. Endocrinology. 1994;135:798–800. doi: 10.1210/endo.135.2.8033830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tontonoz P, Hu E, Graves RA, Budavari AI, Spiegelman BM. mPPARgamma2: tissue-specific regulator of an adipocyte enhancer. Genes Dev. 1994;8:1224–1234. doi: 10.1101/gad.8.10.1224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tontonoz P, Hu E, Spiegelman BM. Stimulation of adipogenesis in fibroblasts by PPARgamma2, a lipid-activated transcription factor. Cell. 1994;79:1147–1156. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90006-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Palmer CN, Hsu MH, Griffin KJ, Raucy JL, Johnson EF. Peroxisome proliferator activated receptor-alpha expression in human liver. Mol Pharmacol. 1998;53:14–22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Auboeuf D, Rieusset J, Fajas L, Vallier P, Frering V, Riou JP, et al. Tissue distribution and quantification of the expression of mRNAs of peroxisome proliferatoractivated receptors and liver X receptor-alpha in humans: no alteration in adipose tissue of obese and NIDDM patients. Diabetes. 1997;46:1319–1327. doi: 10.2337/diab.46.8.1319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gonzalez FJ. The role of peroxisome proliferator activated receptor alpha in peroxisome proliferation, physiological homeostasis and chemical carcinogenesis. Adv Exp Med Biol. 1997;422:109–125. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4757-2670-1_9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Toell A, Polly P, Carlberg C. All natural DR3-type vitamin D response elements show a similar functionality in vitro. Biochem J. 2000;352:301–309. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chen KS, DeLuca HF. Cloning of the human 1a,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 24-hydroxylase gene promoter and identification of two vitamin D-responsive elements. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1995;1263:1–9. doi: 10.1016/0167-4781(95)00060-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lemay J, Demers C, Hendy GN, Delvin EE, Gascon-Barre M. Expression of the 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3K24-hydroxylase gene in rat intestine: response to calcium, vitamin D3 and calcitriol administration in vivo. J Bone Miner Res. 1995;10:1148–1157. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.5650100803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Swami S, Raghavachari N, Muller UR, Bao YP, Feldman D. Vitamin D growth inhibition of breast cancer cells: gene expression patterns assessed by cDNA microarray. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2003;80:49–62. doi: 10.1023/A:1024487118457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Palmer HG, Sanchez-Carbayo M, Ordonez-Moran P, Larriba MJ, Cordon-Cardo C, Munoz A. Genetic signatures of differentiation induced by 1a,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 in human colon cancer cells. Cancer Res. 2003;63:7799–7806. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dunlop TW, Vaisanen S, Frank C, Molnar F, Sinkkonen L, Carlberg C. The human peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor delta gene is a primary target of 1alpha,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 and its nuclear receptor. J Mol Biol. 2005;349:248–260. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2005.03.060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sertznig P, Dunlop T, Seifert M, Tilgen W, Reichrath J. Cross-talk between vitamin D receptor (VDR)- and peroxisome proliferator activated receptor (PPAR)-signaling in melanoma cells. Anticancer res. 2009. (in press) [PubMed]

- 26.Bookout AL, Jeong Y, Downes M, Yu RT, Evans RM, Mangelsdorf DJ. Anatomical profiling of nuclear receptor expression reveals a hierarchical transcriptional network. Cell. 2006;126:789–799. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.06.049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Eastham LL, Mills CN, Niles RM. PPARalpha/gamma expression and activity in mouse and human melanocytes and melanoma cells. Pharma Res. 2008;25:1327–1333. doi: 10.1007/s11095-007-9524-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hansen CM, Binderup L, Hamberg KJ, Carlberg C. Vitamin D and cancer: effects of 1,25(OH)2D3 and its analogs on growth control and tumorigenesis. Front Biosci. 2001;6:820–848. doi: 10.2741/hansen. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Reichrath J, Rech M, Moeini M, Meese E, Tilgen W, Seifert M. In vitro comparison of the vitamin D endocrine system in 1,25(OH)2D3-responsive and -resistant melanoma cells. Cancer Biol Ther. 2007;6:48–55. doi: 10.4161/cbt.6.1.3493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Carlberg C, Polly P. Gene regulation by vitamin D3. Crit Rev Eukaryot Gene Expr. 1998;8:19–42. doi: 10.1615/critreveukargeneexpr.v8.i1.20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zella LA, Kim S, Shevde NK, Pike JW. Enhancers located within two introns of the vitamin D receptor gene mediate transcriptional autoregulation by 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3. Mol Endocrinol. 2006;20:1231–1247. doi: 10.1210/me.2006-0015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Danielsson C, Fehsel K, Polly P, Carlberg C. Differential apoptotic response of human melanoma cells to 1alpha,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 and its analogues. Cell Death Differ. 1998;5:946–952. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4400437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Danielsson C, Torma H, Vahlquist A, Carlberg C. Positive and negative interaction of 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 and the retinoid CD437 in the induction of human melanoma cell apoptosis. Int J Cancer. 1999;81:467–470. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0215(19990505)81:3<467::aid-ijc22>3.0.co;2-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Osborne JE, Hutchinson PE. Vitamin D and systemic cancer: is this relevant to malignant melanoma? Br J Dermatol. 2002;147:197–213. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2133.2002.04960.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Seifert M, Rech M, Meineke V, Tilgen W, Reichrath J. Differential biological effects of 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 on melanoma cell lines in vitro. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 2004;89:375–379. doi: 10.1016/j.jsbmb.2004.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Grabacka M, Plonka PM, Urbanska K, Reiss K. Peroxisome proliferator receptor α activation decreases metastatic potential of melanoma cells in vitro via downregulation of Akt. Clin Cancer Res 2. 2006;12:3028–3036. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-05-2556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]