Abstract

Objectives

Three-dimensional ultrasound (3D-US) imaging is a powerful tool to visualize various components of the anal sphincter complex, i.e., the internal anal sphincter (IAS), the external anal sphincter (EAS) and the puborectalis muscle (PRM). Our goal was to determine the reliability of 3D US imaging technique in detecting morphological defects in the IAS, EAS & PRM.

Methods

Transperineal 3D-US images were obtained in 3 groups of women: nulliparous (n=13), aysmptomatic parous (n=20) and patients with fecal incontinence (FI) (n=25). The IAS and EAS were assessed to determine the cranio-caudal length of defects and scored as follows: 0=normal, 1=<25%, 2=25–50%, 3=50–75%, 4=>75%. The two PRM hemi-slings were scored separately, 0 = normal, 1 = <50% abnormal and 2 = >50% length abnormal. Subjects were grouped according to the score as: normal (score 0), minor abnormality (scores of 1 and 2) and major abnormality (scores of 3 and 4). Three observers performed the scoring.

Results

The 3D-US allowed detailed evaluation of the IAS, EAS & PRM. The inter-rater reliability for detecting the defects ranged between 0.80–0.95. Nullipara women did not show any significant defect but the defects were quite common in asymptomatic parous and FI patients. The prevalence of defects was greater in the FI patients as compared to the aysmptomatic parous women.

Conclusion

3D-US yields reliable assessment of the morphological defects in the anal sphincter complex muscles.

Keywords: three-dimensional ultrasound imaging, intra-rater reliability, the puborectalis muscle, internal anal sphincter, and external anal sphincter

INTRODUCTION

Anal sphincter complex consists of the internal anal sphincter (IAS), the external anal sphincter (EAS) and the puborectalis muscle (PRM). Anatomical defects of the IAS, EAS and PRM are associated with fecal incontinence1–3. The PRM, also referred to as the pubovisceral muscle by some investigators, is a part of the pelvic floor (levator-ani) muscle complex 4. The anatomical defects in the PRM occur commonly in women following childbirth5, 6. Two-dimensional, and 3-dimensional endoanal ultrasound imaging has been used to assess the IAS and EAS7, 8. More recently, the 3D-US imaging of the anal sphincter complex has been performed using a transperineal cutaneous approach. The major advantages of 3D US imaging is that it is less invasive because the transducer does not need to be inserted into the anal canal 9–11. Furthermore, it allows visualization of the entire sling of the PRM12, which is not possible with the endo-anal US imaging. However, limited data are available with regards to the standardization and reproducibility of 3D-US imaging technique to assess the anal sphincter complex muscles. The aim of our study was to perform an inter-rater reliability study of the 3D ultrasound imaging technique in detecting morphological defects in the various components of the anal sphincter complex muscles.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

The University of California, San Diego Institutional Review Board approved the protocol for the study and each subject signed an informed consent prior to participation in the study. The study is an ongoing case-control protocol to evaluate patients with fecal incontinence (FI), asymptomatic parous controls and nulliparous controls. For this particular study, the US images obtained in 58 females were analysed. Each subject completed a medical history, validated urinary and fecal incontinence questionnaires to assess urinary and anal incontinence symptoms (Urinary Distress Inventory, short form [UDI-6]13, Incontinence Impact Questionnaire, short form [IIQ-7]13 and Fecal Incontinence Severity Index [FISI]14). Women with FI, who had a score of 20 or greater on the FISI questionnaire, were included in the study. All parous controls had at least one prior full-term vaginal delivery (>2,000gm size fetus). Nulliparous and parous controls scored less than five on the FISI14 questionnaire and had no “moderate” or “greatly bothered” responses to any questions on the UDI-6 and IIQ-713 questionnaires.

The transperineal 3D ultrasound imaging was performed with the subjects in the dorsal lithotomy position, using either a Voluson 730 (General Electric Healthcare, Milwaukee, WI) or an HD11 system (Philips Medical Systems, Bothell, WA). No bowel preparation was instituted prior to US imaging. The 5–9 MHz (Voluson 730), or a 3–9 MHz (HD11) endo-vaginal transducer was placed on the perineum and oriented in the mid-sagittal plane to obtain images of the anal sphincter complex. The ultrasound beam was directed in the cranial direction to capture the pelvic floor hiatus along with the PRM images and in the posterior direction to capture the IAS and the EAS images. Imaging was performed at rest and then during a sustained anal sphincter/pelvic floor contraction (squeeze). All images were stored on compact disks and analyzed off-line using the proprietary soft wares, 4D View (General Electric) and Q-lab 5.0 (Philips).

Three observers, each with greater than 2 years experience in the 3D-US assessment of the anal sphincter complex evaluated these images. All investigators discussed the scoring system and practiced scoring as a group prior to this study. The three observers independently performed the post-processing of the images and applied the scoring system to evaluate the PRM, EAS and IAS. Two of the three observers (RKM and DHP) were also blinded to the subject’s parous or continence status; the third observer (MMW) captured all the images and thus was aware of the participant’s detailed clinical history. For each of the structures (IAS, EAS & PRM), at least four separately captured volumes (usually two at rest and two during squeeze) were reviewed to confirm the presence or absence of anatomical defects. The latter was defined as an US image abnormality seen as muscle disruption. Whenever an imaging abnormality was visualized, all available volumes depicting the structure were carefully inspected to confirm the presence of true abnormality versus an artifact. If the imaging abnormality appeared to have sharp edges, an image artifact was suspected. The three observers also agreed on the characteristic appearance of different imaging artifacts. The observers assigned the final score after all the available volumes for each muscle structure were evaluated.

To visualize anal sphincters, the sagittal images of the anal canal were placed in the horizontal direction and axial images were visualized along the entire cranio-caudal length of the IAS and EAS, at every 1 mm distance (Figure 1). The IAS and EAS muscles are approximately 3cm and 2cm respectively in the cranio-caudal extent8. In each 2D-axial image, any abnormality around the circumference of the IAS or EAS was noticed. Normally, the anal canal is fairly symmetric (circular in shape). Finding of the asymmetric anal canal shape on the axial images also helped confirm the suspected defect. The scoring system reflects the percentage of total number of slices that were abnormal (Figures 2 and 3). The IAS and EAS were assessed separately for abnormalities and scored as follows:

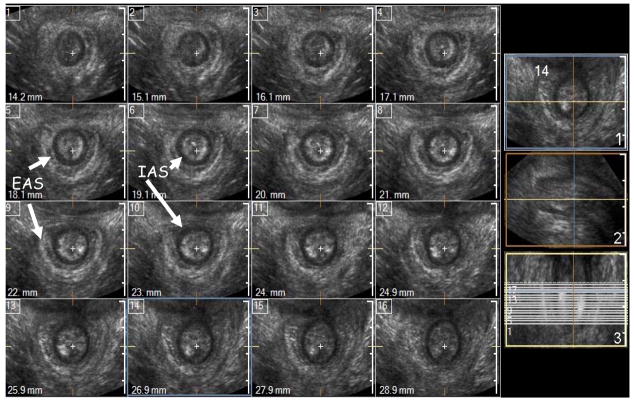

Figure 1.

Cross-sectional (axial) 1 mm multi-slice imaging of the normal anal canal in a nulliparous subject. In this example the anal sphincter complex is shown at every 1 mm distance using I-Slice function of HD-11 (Philips). Marked in the figure are the IAS (black circle) and the EAS (white outer ring) are smooth, uniform and symmetrical.

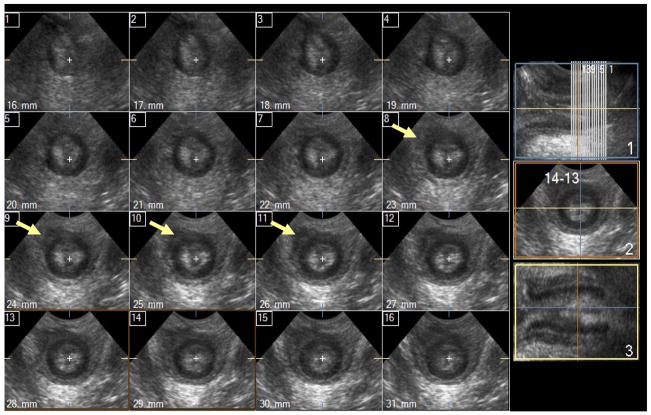

Figure 2.

Cross-sectional (axial) 1 mm multi-slice images of the anal sphincter complex with <50% damage – damage in the external anal sphincter (EAS) is marked with white arrows, no internal anal sphincter (IAS) damage is seen.

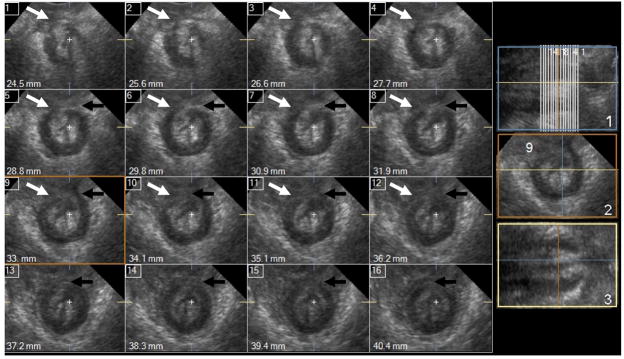

Figure 3.

Cross-sectional (axial) 1mm multi-slice images of the anal sphincter complex 100% damage. Damage of the external anal sphincter (EAS) is marked with white arrow. Damage in the internal anal sphincter (IAS) shown with black arrows; the IAS has horse-shoe instead of the circular shape. The shape of the sphincter complex and the anal mucosa are oblong.

0 → normal (i.e. no imaging abnormalities present on any of the 1mm slices)

1 → ≥25% of total images were abnormal,

2 → 25–50% of total images were abnormal

3 → 50–75% of total images were abnormal,

4 → ≥ 75% of total images were abnormal.

To visualize the PRM, the 3D-US volume was rotated as previously described15. To determine the plane of the PRM, the lower end of pubic symphysis and anorectal angle were identified; the PRM plane was defined as the straight line connecting these 2 points. In addition to analysing US images in the PRM plane, the images were also assessed in the planes parallel to the PRM plane in the cranial and caudal directions, millimetre by millimetre. Furthermore, a thick slice function (10mm) that integrates the US data over a defined thickness (Figure 4) was also used to assess the morphological appearance of the muscle for any defect. The latter was helpful in determining if the abnormality in the US images in the 2D multi-slice was indeed real. Since an anatomical disruption of the PRM may cause asymmetry of the pelvic floor hiatus, shift of the pelvic floor hiatal structures from the midline and vaginal shape asymmetry were also evaluated. Therefore, all of the above findings were taken into consideration to confirm a suspected disruption of the PRM. Our scoring system to determine the severity of PRM damage was a slight modification of the previously published levator-ani MRI scoring system5. In our study, the PRM was divided into two hemi-slings and scored separately.

Figure 4.

Examples of the puborectalis muscle (PRM) injury on 10mm ‘thick slice’ images of the PRM. The numbers on each panel demonstrates how each PRM hemi-sling is scored separately (see methods for details).

0 → normal

1 → <50% of the length of the hemi-sling abnormal

2 → ≥ 50% of the length of the hemi-sling abnormal

The scores from both sides were added; the maximal possible score an individual could receive was 4 (Figure 4).

We also measured the anterior-posterior length (APL) of the pelvic floor hiatus, which was the distance between the pubic symphysis and anorectal angle15.

For each of the structures, the PRM, EAS and IAS we grouped the data as follows:

Normal group - score 0

Minor abnormality group - scores of 1 and 2

Major abnormality group - scores of 3 and 4

Group comparisons were performed using two-sided Student t test and Mann Whitney U test for parametric and non-parametric data respectively. To determine correlation between anterior-posterior length of the pelvic floor hiatus (APL) and PRM morphological score one-way ANOVA statistics was used. For intra-rater reliability data, Cronbach’s alpha (SPSS 11.5) was used to compare the individual scores between two or three observers.

RESULTS

3D-US images from 58 females were included for analysis, 33 without symptoms of urinary or anal incontinence (13 nullipara and 20 vaginally parous) and 25 patients with fecal incontinence. Table IA summarizes the demographic information in three groups. The nulliparous group was younger than the FI and parous groups. The FI group had significantly higher fecal incontinence severity index (FISI) scores compared with the other two groups. The three groups were found to have a spectrum of normal and abnormal findings.

Table I.

Groups characteristics

| Characteristics | Nulliparous controls N=13 | Parous Controls N=20 | FI patients N=25 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age years (range) | 29 (19–54)* | 52 (34–67) | 53 (29–74) |

|

| |||

| Race (%white) | 54% | 60% | 64% |

|

| |||

| BMI (kg/m2) | 23.6±4.3 | 26.1±4.4 | 26.9±5.6 |

|

| |||

| Vaginal parity: Mean ± SD | 0 | 2.2±1.1 | 1.6±1.2 |

| Median (range) | 0 | 2 (1–5) | 2 (0–4) |

|

| |||

| FISI14 Median (range) | 0 (0) | 0 (0–4) | 38 (20–54)^ |

p-value <0.05 as compared with parous and FI patients groups

p-value <0.001 as compared with nulliparous and parous asymptomatic groups

Out of the 58 subjects, adequate images were obtained in 57 subjects for the evaluation of IAS, EAS and PRM. One observer scored images from 20 subjects; the two other observers evaluated all 58 subjects. Figure 3 demonstrates representative examples of the normal and abnormal PRM and anal sphincter muscles. When the muscles were normal, as was the case in all but one nulliparous women, it was usually quite clear. However, when muscle disruption was suspected, great care was taken to distinguish the true morphological defect from an image artifact. The muscles were usually denser with clearer edges on the squeeze image as compared to the rest image. However, squeeze images had a potential of introducing edge refraction, air and motion artifacts. Moreover, in the PRM/pelvic floor hiatus volumes, if asymmetry of the pelvic floor hiatus or asymmetry of the vaginal shape was present it was usually accentuated by the squeeze (Figure 5). Frequently, ballooning of the vagina towards the side of the PRM defect was seen in the squeeze image. In the US volumes that captured the IAS and EAS, the appearance of asymmetric anal canal was highly suggestive of the morphological abnormality. However, in addition to the common imaging artifacts, the anal canal shape was occasionally distorted due to an external compression of the perineal body by the US transducer. In the case of suspected external compression from US transducer all the available volumes were reviewed. The external compression related artifact was usually less pronounced in the squeeze volumes of the anal canal. The longitudinal extent of injury to the IAS and EAS was quite variable and ranged from 2 millimetres in length to the entire longitudinal extent of the IAS and EAS. On the other hand, the variability in the circumferential extent of the defect was relatively small and ranged from 20–30%.

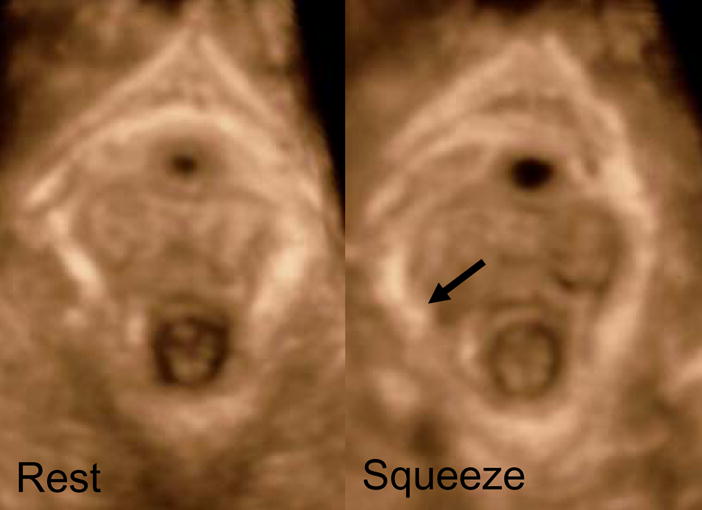

Figure 5.

Dynamic images of the pelvic floor hiatus at rest and squeeze in the same parous woman. The injury of the puborectalis muscle is accentuated when during pelvic floor contraction (squeeze) maneuver the pelvic floor hiatus bulges out towards the side of injury (arrow).

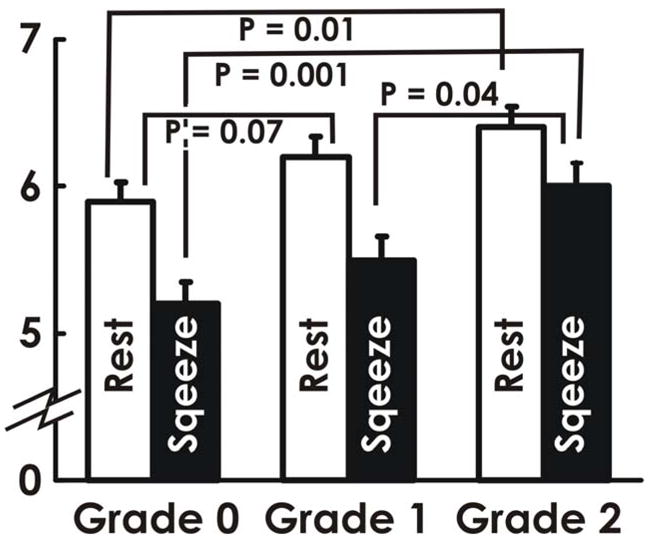

Table 2 shows the summary of data scored by one blinded observer (DHP). In the nullipara group, only 1 subject demonstrated minor abnormality of the PRM. On the other hand, the prevalence of minor and major abnormalities in the 3 muscles was observed with greater frequency in the parous control group. Patients with FI symptoms had even greater number of abnormalities. The subjects with 2 or all 3 abnormal muscles were greater in the FI patients as compared to asymptomatic parous controls (48% versus 20%). The inter-rater reliability measure, Cronbach’s alpha for the 2 observers is 0.82, 0.92 and 0.95 for the PRM, EAS and IAS respectively. The corresponding values for the 3 observers (n=20), is 0.91, 0.90 and 0.89 for the PRM, EAS and IAS respectively. Figure 6 shows the relationship between the anterior-posterior (AP) length of the pelvic floor hiatus in parous and FI subjects (n=44). Patients with minor as well major abnormalities of the PRM (grades 1 and 2) had significantly longer AP length, both at rest and during squeeze, as compared to the subjects with no abnormality (grade 0).

Table 2.

Presence of minor and major imaging abnormalities in three groups

| Groups | Nulliparous controls (N=13) | Parous Controls (N=20) | FI patients (N=25) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PRM | Normal | 12/13 (92%) | 9/19 (47%) | 7/25 (28%) |

| Minor abnormalities | 1/13 (8%) | 6/19 (32%) | 8/25 (32%) | |

| Major abnormalities | 0 | 4/19 (21%) | 10/25 (40%) | |

|

| ||||

| EAS | Normal | 13/13 (100%) | 16/20 (80%) | 13/25 (52%) |

| Minor abnormalities | 0 | 2/20 (10%) | 5/25 (20%) | |

| Major abnormalities | 0 | 2/20 (10%) | 7/25 (28%) | |

|

| ||||

| IAS | Normal | 13/13 (100%) | 15/20 (75%) | 12/25 (48%) |

| Minor abnormalities | 0 | 3/20 (15%) | 5/25 (20%) | |

| Major abnormalities | 0 | 2/20 (10%) | 8/25 (32%) | |

|

| ||||

| More than one abnormality* | 0/13 (0%) | 5/20 (20%) | 12/25 (48%) | |

The proportion of subjects who had abnormality in two or all three assessed muscles (EAS, IAS and PRM)

Figure 6.

Anterior-posterior length (mean + SEM) of the pelvic floor hiatus in the plane of the puborectalis muscle in the parous (n=19) and fecal incontinence patients (n=25) with different grades of PRM injury.

DISCUSSION

In summary, our data show the following, 1; anatomical defects of the individual components of the anal sphincter complex can be recognized using the transperineal, cutaneous 3D-US imaging technique, 2; there is an excellent inter-rater reliability for the detection of abnormalities in the anal sphincter complex in the 3DUS images, 3; parous subjects with an anatomically defective PRM have a longer AP length of the pelvic floor hiatus as compared to the ones with an intact PRM, 4; aysmptomatic parous controls show defects in the PRM quite frequently, however anal sphincter defects in this group are less common as compared to the FI patients and 5; the prevalence of more than 1 abnormality in a given subject is greater in the FI patients as compared to aysmptomatic parous controls.

As compared to endoanal approaches, transperineal imaging of the anal sphincter is clearly more desirable because it does not requires insertion of the US transducer into the anal canal. Furthermore, the ability to capture a 3D US volume has many advantages; 1, it reduces the operator-induced error in capturing adequate images, 2; it allows visualization of the US images in the 3 standard planes (coronal, sagittal and transverse) or any other desired plane, 3; it allows one to view the thin and thick slices of the US images in the desired planes, which adds further strength to image analysis, 4; it allows visualization of the entire sling of the PRM and pelvic floor hiatus, 5; from the pelvic floor hiatus images, asymmetry of the hiatus and abnormalities in the shape of the vagina and other structures in the hiatus can be easily discerned.

Our study is the first to describe a semi-quantitative scoring system for the assessment of morphological abnormalities in the anal sphincter complex muscles using the transperineal 3D-US imaging technique. Our IAS and EAS scoring system was slightly different from what has been commonly used in the literature. It addresses the length of disruption of the sphincters as opposed to the degree of circumferential break. Our rationale is that disruption of a ring (sphincter muscle), regardless of degree of circumferential separation will compromise sphincter function. Furthermore, we found that the longitudinal extent of injury varies significantly among different subject but the circumferential extent of injury is relatively same, i.e., 20–30% of the extent of the circumference of the anal canal. The injury to the sphincter muscles is always located in the anterior section because the injury in majority of the subject is most likely related to obstetrical trauma or episiotomy. We found an excellent inter-rater reliability of the scoring system. We were aware of the various sources of artifacts in the US images16 and assessed our images carefully to exclude possible error related to these artifacts. The most common artifacts in the US images are due to motion, air shadowing and edge refraction. When possible muscle disruption was found, multiple US volumes at rest and squeeze were evaluated to confirm our findings. Furthermore, asymmetry of the pelvic floor hiatus and abnormalities in the shape of vagina and sphincter muscles were also taken into consideration to ensure that the observed anatomical defect was not an imaging artifact. The following software tools were extremely helpful in scoring the pelvic floor muscles: multislice (e.g. iSlice [Philips], TUI [GE]), thick slice, multiplanar, contrast/brightness image settings, and scrolling back and forth function.

The anatomical defects of the internal and external anal sphincter muscles in the multipara women are quite common. Sultan and colleagues1 found that following childbirth, 35% of the primiparous women develop defects of the IAS or EAS or both. The prevalence of anal sphincter defects in the multiparous group was even higher, i.e., 44%. On the other hand, in our population of aysmptomatic parous women, the prevalence of IAS and EAS defects is quite low. We believe that the reason may be that unlike earlier studies, our subjects, even though parous, were carefully selected for the absence of fecal incontinence symptoms, which was not the case in earlier studies. Another reason may be that the 3D-US imaging technique allows better assessment of the anal sphincter complex because one can view images in all 3 planes and using the multislice function one can visualize images at every 1mm distance. Our’s is the first study to determine the prevalence of anal sphincter defects in the asymptomatic parous women using the transperineal 3D-US imaging technique. We found high prevalence of anatomical defects in the PRM (major defects in 21% of aysmptomatic parous women), a finding similar to the one reported by the other investigators. DeLancey et al5, who used MR imaging, found that 20% of parous women had defects in the levator-ani muscle. Deitz et al6 who used 3D-US imaging technique, similar to our technique, found levator ani avulsions in 36% of the parous women.

The puborectalis muscle (PRM) that encircles the pelvic floor hiatus is a major determinant of the AP length of the hiatus. Accordingly, pelvic floor contraction reduces and pudendal nerve block increases the AP length of the pelvic floor hiatus17. We found that women with anatomic defects of the PRM have significantly longer AP length at rest and squeeze, as compared to the ones with no muscle defects. It is likely that women with the PRM defects have a decreased muscle tone at rest and diminished ability to contract the PRM with squeeze. We propose that our finding of the longer resting and squeeze AP lengths of the pelvic floor hiatus in women with PRM abnormality provides validity to our scoring system. The current understanding is that the development of fecal incontinence requires multiple hits, i.e., damage to 2 or more muscles of the continence system 2, 18. Clinical observations suggest that women with significant defects of the EAS may maintain continence through the IAS and PRM19. Accordingly, we found that the FI group showed a greater proportion of subjects with two or more abnormal muscles of continence, as compared to the asymptomatic parous controls, which we believe provides further validity to the 3D US image modality and our scoring system.

The limitations of our study include non-blinding of one of the reviewers of US images with regards to the nulliparous, parous or FI status of the subject. Although this could affect the prevalence of defects recorded by this reviewer, it should not affect inter-rater reliability between other observers. Does the US image abnormality mean true anatomic or functional abnormality? In the case of 2D endoanal ultrasounds, authors report high correlation between anatomical abnormalities detected on the ultrasound images with the findings at the time of surgery20 or histology21. Certainly more studies are needed to correlate the imaging abnormalities with the muscle function. Another potential limitation of our study is that we did not perform a direct comparison of the 3D-US images with the currently considered gold standard, i.e., 2D endo-anal US images. However, comparison of the published 2D-US images with our 3D-US images shows that the 3D-US images are comparable in quality to the 2D-US images with several added advantages as listed earlier.

In summary, the 3D-US imaging is a portable and relatively inexpensive modality, as compared to the MRI technique, to evaluate the anatomical integrity of the muscles of anal sphincter complex. It is also fairly quick as it takes only 6–8 seconds to capture each US volume. Our study shows that the transperineal 3D-US can be used for semi-quantitative assessment of the anal sphincters and puborectalis muscle. Future studies may investigate if there are differences in the 3D-US images of anal sphincter complex muscles in patients with and without history of anal sphincter tear at the time of childbirth. Furthermore, it would be extremely important to determine if there are differences in the appearance of anal sphincter complex in nullipara women with and without history of fecal incontinence.

Acknowledgments

Financial supported by: NIH RO1 grant DK60733

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest: Dr Pretorius is a consultant for Philips Medical Systems

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Sultan AH, Kamm MA, Hudson CN, Thomas JM, Bartram CI. Anal-sphincter disruption during vaginal delivery. N Engl J Med. 1993;329(26):1905–11. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199312233292601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fernandez-Fraga X, Azpiroz F, Malagelada JR. Significance of pelvic floor muscles in anal incontinence. Gastroenterology. 2002;123(5):1441–50. doi: 10.1053/gast.2002.36586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bharucha AE. Fecal incontinence. Gastroenterology. 2003;124(6):1672–85. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5085(03)00329-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.DeLancey JO. The anatomy of the pelvic floor. Curr Opin Obstet Gynecol. 1994;6(4):313–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.DeLancey JO, Kearney R, Chou Q, Speights S, Binno S. The appearance of levator ani muscle abnormalities in magnetic resonance images after vaginal delivery. Obstet Gynecol. 2003;101(1):46–53. doi: 10.1016/s0029-7844(02)02465-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dietz HP, Lanzarone V. Levator trauma after vaginal delivery. Obstet Gynecol. 2005;106(4):707–12. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000178779.62181.01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sentovich SM, Wong WD, Blatchford GJ. Accuracy and reliability of transanal ultrasound for anterior anal sphincter injury. Dis Colon Rectum. 1998;41(8):1000–4. doi: 10.1007/BF02237390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Liu J, Guaderrama N, Nager CW, Pretorius DH, Master S, Mittal RK. Functional correlates of anal canal anatomy: puborectalis muscle and anal canal pressure. Am J Gastroenterol. 2006;101(5):1092–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2006.00596.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Timor-Tritsch IE, Monteagudo A, Smilen SW, Porges RF, Avizova E. Simple ultrasound evaluation of the anal sphincter in female patients using a transvaginal transducer. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2005;25(2):177–83. doi: 10.1002/uog.1827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lee JH, Pretorius DH, Weinstein M, Guaderrama NM, Nager CW, Mittal RK. Transperineal three-dimensional ultrasound in evaluating anal sphincter muscles. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2007 doi: 10.1002/uog.4057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Valsky DV, Messing B, Petkova R, et al. Postpartum evaluation of the anal sphincter by transperineal three-dimensional ultrasound in primiparous women after vaginal delivery and following surgical repair of third-degree tears by the overlapping technique. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2007;29(2):195–204. doi: 10.1002/uog.3923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jung SA, Pretorius DH, Padda BS, et al. Vaginal high-pressure zone assessed by dynamic 3-dimensional ultrasound images of the pelvic floor. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2007;197(1):52, e1–7. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2007.04.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Uebersax JS, Wyman JF, Shumaker SA, McClish DK, Fantl JA. Short forms to assess life quality and symptom distress for urinary incontinence in women: the Incontinence Impact Questionnaire and the Urogenital Distress Inventory. Continence Program for Women Research Group. Neurourol Urodyn. 1995;14(2):131–9. doi: 10.1002/nau.1930140206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rockwood TH, Church JM, Fleshman JW, et al. Patient and surgeon ranking of the severity of symptoms associated with fecal incontinence: the fecal incontinence severity index. Dis Colon Rectum. 1999;42(12):1525–32. doi: 10.1007/BF02236199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Weinstein MM, Jung SA, Pretorius DH, Nager CW, den Boer DJ, Mittal RK. The reliability of puborectalis muscle measurements with 3-dimensional ultrasound imaging. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2007;197(1):68, e1–6. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2007.02.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nelson TR, Pretorius DH, Hull A, Riccabona M, Sklansky MS, James G. Sources and impact of artifacts on clinical three-dimensional ultrasound imaging. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2000;16(4):374–83. doi: 10.1046/j.1469-0705.2000.00180.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Guaderrama NM, Liu J, Nager CW, et al. Evidence for the innervation of pelvic floor muscles by the pudendal nerve. Obstet Gynecol. 2005;106(4):774–81. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000175165.46481.a8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bharucha AE, Fletcher JG, Harper CM, et al. Relationship between symptoms and disordered continence mechanisms in women with idiopathic faecal incontinence. Gut. 2005;54(4):546–55. doi: 10.1136/gut.2004.047696. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Malouf AJ, Norton CS, Engel AF, Nicholls RJ, Kamm MA. Long-term results of overlapping anterior anal-sphincter repair for obstetric trauma. Lancet. 2000;355(9200):260–5. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(99)05218-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Deen KI, Kumar D, Williams JG, Olliff J, Keighley MR. Anal sphincter defects. Correlation between endoanal ultrasound and surgery. Ann Surg. 1993;218(2):201–5. doi: 10.1097/00000658-199308000-00013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sultan AH, Kamm MA, Talbot IC, Nicholls RJ, Bartram CI. Anal endosonography for identifying external sphincter defects confirmed histologically. Br J Surg. 1994;81(3):463–5. doi: 10.1002/bjs.1800810349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]