Abstract

Phenolic compounds affect intracellular free Ca2+ concentration ([Ca2+]i) signaling. The study examined whether the simple phenolic compound octyl gallate affects ATP-induced Ca2+ signaling in PC12 cells using fura-2-based digital Ca2+ imaging and whole-cell patch clamping. Treatment with ATP (100 µM) for 90 s induced increases in [Ca2+]i in PC12 cells. Pretreatment with octyl gallate (100 nM to 20 µM) for 10 min inhibited the ATP-induced [Ca2+]i response in a concentration-dependent manner (IC50=2.84 µM). Treatment with octyl gallate (3 µM) for 10 min significantly inhibited the ATP-induced response following the removal of extracellular Ca2+ with nominally Ca2+-free HEPES HBSS or depletion of intracellular Ca2+ stores with thapsigargin (1 µM). Treatment for 10 min with the L-type Ca2+ channel antagonist nimodipine (1 µM) significantly inhibited the ATP-induced [Ca2+]i increase, and treatment with octyl gallate further inhibited the ATP-induced response. Treatment with octyl gallate significantly inhibited the [Ca2+]i increase induced by 50 mM KCl. Pretreatment with protein kinase C inhibitors staurosporin (100 nM) and GF109203X (300 nM), or the tyrosine kinase inhibitor genistein (50 µM) did not significantly affect the inhibitory effects of octyl gallate on the ATP-induced response. Treatment with octyl gallate markedly inhibited the ATP-induced currents. Therefore, we conclude that octyl gallate inhibits ATP-induced [Ca2+]i increase in PC12 cells by inhibiting both non-selective P2X receptor-mediated influx of Ca2+ from extracellular space and P2Y receptor-induced release of Ca2+ from intracellular stores in protein kinase-independent manner. In addition, octyl gallate inhibits the ATP-induced Ca2+ responses by inhibiting the secondary activation of voltage-gated Ca2+ channels.

Keywords: Ca2+, Flavonoid, Octyl gallate, PC12 cells, Phenolic compound, Purinergic receptor, Voltage-gated Ca2+ channels

INTRODUCTION

ATP is a neurotransmitter or neuromodulator in many areas of the peripheral and central nervous system [1,2]. ATP induces an increase in intracellular free Ca2+ concentration ([Ca2+]i) in PC12 cells by activating both P2X-receptor-regulated non-selective cation channels [3] and P2Y-receptor-mediated phospholipase C (PLC) [4,5]. In addition, the ATP-induced activation of non-selective cation channels induces an increase in [Ca2+]i through the depolarization-induced activation of voltage-gated L-type Ca2+ channels [5].

Fruits, vegetables, beverages, plants, and some herbs are enriched with powerful antioxidant polyphenols. Phenolic compounds are attracting increasing interest from consumers and manufacturers because numerous epidemiological studies have suggested associations between the consumption of polyphenol-rich foods or beverages and the prevention of certain chronic diseases such as cancers and cardiovascular diseases [6,7]. Moreover, these compounds have been reported to be able to protect neuronal cells in various in vitro and in vivo models through different intracellular targets [8-13]. Phenolic compounds affect the function of voltage-gated ion channels [14-17] including voltage-gated Ca2+ channels [18]. Phenolic compounds have ability to affect agonist-induced [Ca2+]i increase in neuronal cells [19-22]. Octyl gallate is a simple phenol compound that potently inhibits the flux of Ca2+ into rat pituitary GH4C1 cells [23].

ATP-induced [Ca2+]i increase in PC12 cells may be involved in the release of catecholamine in PC12 cells [24-26] and in cell death [27]. Although octyl gallate has been reported to have inhibitory effects on Ca2+ flux into rat pituitary GH4C1 cells, there are no reports on the effect of octyl gallate against ATP-induced Ca2+ signaling in cultured PC12 cells. The present study examined whether octyl gallate inhibits ATP-induced [Ca2+]i increases in PC12 cells using fura-2-based digital Ca2+ imaging and whole-cell patch clamping.

METHODS

Materials

Fura-2 acetoxymethylester (AM) was purchased from Molecular Probes (Eugene, OR, USA). Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM), fetal bovine serum (FBS, heat-inactivated) and horse serum (HS, heat-inactivated) were obtained from Invitrogen (Carlsbad, CA, USA). ATP (disodium salt), bovine serum albumin, octyl gallate and all other reagents were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA).

Cell culture

PC12 rat medulla pheochromocytoma cells were grown in DMEM supplemented with 10% FBS and 10% HS at 37℃ in a humidified atmosphere of 10% CO2 and 90% O2. To measure [Ca2+]i , cells from a stock culture were plated in wells of six-well culture plates at a density of 3×104 cells/well; each well contained a 25 mm-diameter coverslip (Fisher Scientific, Pittsburgh, PA, USA). Cells were used for experiment 2~3 days after plating.

Ca2+ imaging

Digital imaging of Ca2+ was performed as described previously [28]. Cells were loaded with 12 µM fura-2 AM in HEPES-buffered Hanks's solution (HEPES-HBSS; 20 mM HEPES,137 mM NaCl, 1.26 mM CaCl2, 0.4 mM MgSO4, 0.5 mM MgCl2, 5 mM KCl, 0.4 mM KH2PO4, 0.6 mM Na2HPO4, 3 mM NaHCO3, and 5 mM glucose) containing 0.5% bovine serum albumin for 45 min at 37℃. CaCl2 was removed for nominally Ca2+-free HEPES HBSS. To elicit depolarization-induced activation of the voltage-gated Ca2+ channels, we used 50 mM KCl HEPES-HBSS, in which 137 mM NaCl and 5 mM KCl were replaced with 92.3 mM NaCl and 50 mM KCl, respectively. The loading was terminated by washing with HEPES-HBSS for 15 min before starting the experiment. The coverslip was mounted in a flow through chamber, which was superfused at 2 ml/min. Solutions were selected with a multi-port valve coupled to several reservoirs. The chamber containing the fura-2-loaded cells was mounted on the stage of an inverted microscope and alternately excited at 340 or 380 nm by rapidly switching optical filters (10 nm band pass) mounted on a computer-controlled wheel placed between a 100 W Xe arc lamp and the epifluorescence port of the microscope. Excitation light was reflected from a dichroic mirror (400 nm) through a 20× objective (Nikon; N.A. 0.5). Digital fluorescence images (510 nm, 40 nm band-pass) were collected with a cooled charge-coupled device camera cascade 512B (512×512 binned to 256×256 pixels; Photometrics, Tucson, AZ, USA) controlled by a computer. Image pairs were collected every 3~60 s using an Imaging Work Bench 6.0 (INDEC BioSystems, Santa Clara, CA, USA) exposure to excitation light was 120 ms per image. Cells were delimited by producing a mask that contained pixel values above a threshold applied to the 380 nm image. Background images were collected at the beginning of each experiment after removing cells from another area to the coverslip. Autofluorescence from cells not loaded with the dye was less than 5% and so was not corrected.

Whole-cell patch clamping

Whole-cell currents were recorded at a holding potential of -70 mV with an Axopatch ID patch-clamp amplifier (Axon Instruments). The external solution was composed of the following: 140 mM NaCl; 5 mM KCl; 1.3 mM CaCl2; 1 mM MgCl2, 20 mM HEPES; and 10 mM glucose, and the pH was adjusted to 7.3 with NaOH. Pipettes were filled with buffer consisting of the following: 140 mM CsCl; 1 mM MgCl2; 1 mM CaCl2; 10 mM EGTA; and 10 mM HEPES, adjusted pH 7.3 with CsOH. All experimental parameters were controlled using pClamp 6.03 software (Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA, USA). Drugs were dissolved in the external solution and delivered with a linear array of 0.32 mm inner diameter microcapillary tubes. The tips of the drug application pipettes were placed within 100 µm of the cells [29].

Statistical analyses

Data are expressed as means±SEM. Significance was determined with a one-way ANOVA followed by a Bonferroni's test and non-paired or paired Student's t-test.

RESULTS

Effect of octyl gallate on ATP-induced [Ca2+]i increase in cultured PC12 cells

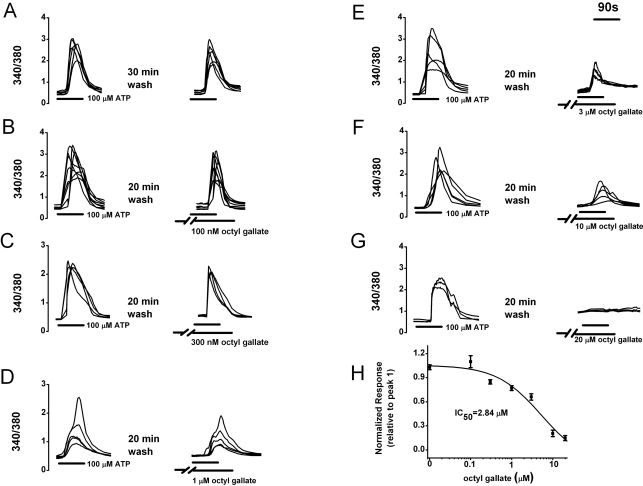

Treatment with ATP (100 µM) for 90 s transiently induced increased [Ca2+]i in PC12 cells. Reproducible responses could be elicited by applying ATP (100 µM) for 90 s at 30 min intervals (relative to peak 1=103.0±3.0%, n=99) (Fig. 1A). To determine whether octyl gallate specifically affects the ATP-induced [Ca2+]i increase, cells were pretreated for 10 min with 100 nM, 300 nM, 1 µM, 3 µM, 10 µM, or 20 µM octyl gallate. Treatment with 100 nM octyl gallate for 10 min did not significantly affect the ATP-induced [Ca2+]i increase (relative to peak 1=109.0±7.4%, n=35) (Fig. 1B), whereas treatment with the increasing concentrations of octyl gallate (300 nM to 20 µM) significantly inhibited ATP-induced responses in a concentration-dependent manner (relative to peak 1=84.8±2.7%, n=26 at 300 nM; 74.8±3.1%, n=30 at 1 µM; 56.9±4.0%, n=39 at 3 µM; 20.5±4.0%, n=21 at 10 µM; 14.7±3.1%, n=15 at 20 µM; Figs. 1C~H). A non-linear least-squares fit by the prism 5.0 to the concentration-response data yielded an IC50 of 2.84±0.18 µM for octyl gallate (Fig. 1H). Thereafter, 3.0 µM octyl gallate was used to quantify and confirm the inhibitory effects of octyl gallate on ATP-induced [Ca2+]i response.

Fig. 1.

Concentration-dependent inhibitory effects of octyl gallate on the ATP-induced [Ca2+]i increase in PC12 cells. (A~G) After pretreating cells with various concentration of octyl gallate, subsequent ATP-induced [Ca2+]i response was observed. Image pairs were collected at 3~60 s intervals. ATP and octyl gallate were applied as indicated by the horizontal bars. (H) Summary of concentration-response data. The ATP-induced response amplitude is presented as a percentage of the initial control (relative to peak 1) (n=99, 35, 26, 30, 39, 21, 15 at 0, 100 nM, 300 nM, 1 µM, 3 µM, 10 µM, 20 µM, respectively). A non-linear least-squares fit by the prism software 5.0 to the concentration-response data yielded an IC50 of 2.84 µM for octyl gallate. Data represent mean±SEM.

Inhibitory effects of octyl gallate on ATP-induced Ca2+ release from intracellular stores and Ca2+ influx from the extracellular space

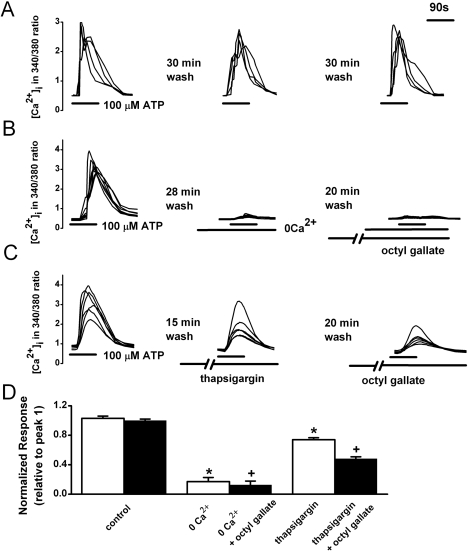

ATP induces releases Ca2+ from intracellular stores or Ca2+ influx from the extracellular space in PC12 cells. The nature of the octyl gallate-mediated inhibition of ATP-induced [Ca2+]i increase was investigated. Specifically, we tested whether the removal of extracellular Ca2+ by treatment with nominally Ca2+-free HEPES HBSS or the depletion of intracellular Ca2+ stores by treatment with thapsigargin which depletes and irreversibly prevents the refilling of intracellular stores [30], affected ATP-induced [Ca2+]i increase in the absence or presence of octyl gallate.

Reproducible responses were elicited by applying ATP (100 µM) for 90 s at 30 min intervals (103.0±3.0% of the control responses, n=99) (Fig. 2A, D). Removal of Ca2+ for 2 min markedly inhibited the subsequent ATP-induced [Ca2+]i response, but ATP still induced a small response (relative to peak 1=17.2±5.6%, n=33). These results suggest that the ATP-induced [Ca2+]i increase in PC12 cells is largely mediated by Ca2+ influx from the extracellular space. Pretreatment with octyl gallate (3 µM) for 10 min significantly inhibited the ATP-induced response in the presence of nominally Ca2+-free HEPES HBSS for 2 min (relative to peak 1=12.4±5.4%, n=33) (Fig. 2B, D). Pretreatment with thapsigargin significantly decreased the subsequent ATP-induced response (relative to peak 1=73.9±2.7%, n=59). Treatment with octyl gallate for 10 min significantly inhibited the ATP-induced responses in thapsigargin-treated cells (relative to peak 1=48±2.8%, n=59) (Fig. 2C, D).

Fig. 2.

Inhibitory effects of octyl gallate on the ATP-induced release of Ca2+ from intracellular stores and Ca2+ influx from the extracellular space. (A) Reproducible [Ca2+]i increases were elicited by super fusion with 100 µM ATP for 90 s at 30 min intervals. ATP-induced [Ca2+]i were recorded after treatment with nominally Ca2+-free HEPES-HBSS for 2 min (B) or with thapsigargin (1 µM) for 15 min (C); then 20 min later the ATP-induced responses were recorded in the presence of octyl gallate (3 µM) for 10 min. (D) Summary of the effects of octyl gallate on ATP-induced [Ca2+]i increase. The amplitude of the ATP-induced response is presented as a percentage of the initial control (relative to peak 1) for the control (n=99), nominally Ca2+-free HEPES-HBSS-treated (0 Ca2+, n=33), 0 Ca2+ plus octyl gallate-treated (n=33), thapsigargin-treated (n=59), and thapsigargin plus octyl gallate-treated (n=59) cells. Data represent mean±SEM. *p<0.05 relative to respective control (paired Student's t-test). +p<0.05 relative to respective non-octyl gallate-treated cells (paired Student's t-test).

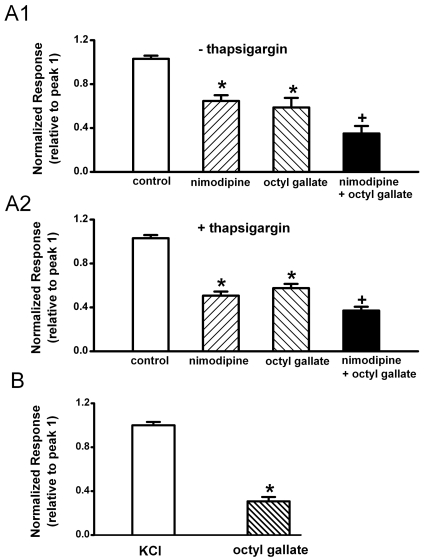

Inhibitory effects of octyl gallate on ATP-induced secondary Ca2+ influx through voltage-gated Ca2+ channels

ATP activates secondarily voltage-gated L-type Ca2+ channels in PC12 cells through the P2X receptor-mediated depolarization by influx of Ca2+ and Na+ [5]. We tested whether octyl gallate affects the ATP-induced secondary activation of voltage gated L-type Ca2+ channels (Fig. 3). Pretreatment with nimodipine (1 µM) for 10 min significantly inhibited the subsequent ATP-induced [Ca2+]i response (relative to peak 1=58.8±2.7% , n=25) (Fig. 3A1). Treatment with octyl gallate (3 µM) for 10 min also significantly inhibited the subsequent ATP-induced [Ca2+]i response (relative to peak 1=54.8±3.6%, n=25). Moreover, treatment for 10 min octyl gallate (3 µM) further inhibited the ATP-induced response in the presence of nimodipine (relative to peak 1=39.3±3.7%, n=25).

Fig. 3.

Inhibitory effects of octyl gallate on the ATP-induced secondary Ca2+ influx through voltage-gated Ca2+ channels. Effects of nimodipine and octyl gallate on ATP (100 µM)-induced [Ca2+]i increase in untreated cells (A1) and thapsigargin-treated cells (A2). Cells were pretreated with thapsigargin (1 µM) for 45 min during the fura-2 loading period, since thapsigargin-induced increase in [Ca2+]i returns to near basal levels after a 15 min exposure to thapsigargin. The amplitude of the ATP-induced response after treatment of vehicle (control) (n=25, n=24), nimodipine (n=25, n=24), octyl gallate (n=25, n=24), nimodipine plus octyl gallate (n=25, n=24) is presented as a percentage of the initial control in untreated and thapsigargin-treated cells, respectively. (B) Effects of octyl gallate on KCl (50 mM K+ HEPES-HBSS)-induced [Ca2+]i increase. The amplitude of the KCl-induced response after treatment of vehicle (n=31) or octyl gallate (n=26) is presented as a percentage of the initial control. Data represent mean±SEM. *p<0.05 relative to respective control or KCl-treated cell; +p<0.05 relative to respective nomodipine or octyl gallate-treated cells (one way ANOVA followed by Bonferroni's test and paired Student's t-test).

Since ATP increases [Ca2+]i by the release of Ca2+ from intracellular stores as well as extracellular Ca2+ influx (Fig. 2), the next experiment assessed whether octyl gallate could inhibit ATP-induced Ca2+ influx in intracellular store-depleted cells (Fig. 3A2). Cells were pretreated with thapsigargin (1 µM) for 45 min during the fura-2 loading period, since the thapsigargin-induced [Ca2+]i increase returns to near basal levels after a 15 min exposure to thapsigargin [5]. Treatment with nimodipine (1 µM) for 10 min significantly inhibited the subsequent ATP-induced [Ca2+]i response (relative to peak 1=50.7±3.6%, n=30) (Fig. 3A2), as did treatment with octyl gallate (3 µM) for 10 min (relative to peak 1=57.6±3.8%, n=30). Moreover, treatment with 3 µM octyl gallate for 10 min further inhibited the ATP-induced response in the presence of nimodipine (relative to peak 1=37.1±3.5%, n=30).

To confirm the inhibitory effect of octyl gallate on the secondary Ca2+ influx through the ATP-induced activation of voltage-gated Ca2+ channels, it was determined whether octyl gallate could inhibit the depolarization-induced activation of Ca2+ channels using 50 mM KCl HEPES HBSS (Fig. 3B). Reproducible [Ca2+]i increases were induced by treatment for 90 s with 50 mM KCl HEPES HBSS at 30 min intervals (relative to peak 1=98.5±3.0%, n=31). Pretreatment for 5 min with octyl gallate (3 µM) significantly inhibited the subsequent high KCl-induced [Ca2+]i response (relative to peak 1=30.7±4.0%, n=26).

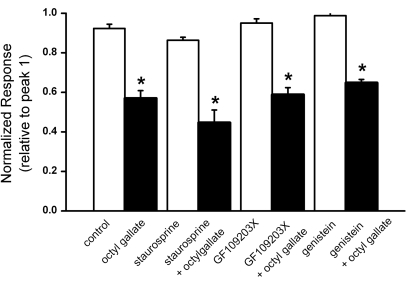

Effects of protein kinase inhibitors on the ATP-induced [Ca2+]i increases

ATP induces activation of phospholipase C (PLC) in PC12 cells [5], which can activate protein kinase C (PKC) and tyrosine kinase. Phenolic compounds also potently inhibit several kinases involved in signal transduction, mainly PKC and tyrosine kinases [31], and tyrosine phosphorylation can induce Ca2+ influx [32]. Appropriately, an experiment was done to ascertain whether octyl gallate could inhibit ATP-induced [Ca2+]i increase via inhibition of PKC or tyrosine kinase (Fig. 4). Pretreatment for 10 min with the non-specific PKC inhibitor staurosporin (100 nM), the specific PKC inhibitor GF109203X (300 nM), or the tyrosine kinase inhibitor genistein (50 µM) did not affect the ATP-induced response. However, treatment with octyl gallate (3 µM) significantly inhibited the ATP-induced response in the presence of the non-specific or specific PKC inhibitors, and the tyrosine kinase inhibitor. Moreover, no differences were observed in the response induced by treatment with octyl gallate in the presence or absence of the kinase inhibitors.

Fig. 4.

ATP-induced [Ca2+]i increase were not inhibited by treatment with PKC inhibitors staurosporin, GF10923X or the tyrosine kinase inhibitor genistein. ATP-induced responses were induced in the presence of vehicle (control, n=59), octyl gallate (3 µM, n=39), staurosprin (100 nM, n=30), staurosprin (100 nM) plus octyl gallate (3 µM) (n=29), GF 109203X (300 nM, n=32), GF 109203X (300 nM) plus octyl gallate (3 µM) (n=29), genistein (50 µM, n=35), genistein (50 µM) plus octyl gallate (3 µM) (n=34) for 10 min following 90 s exposure to ATP and a 20 min wash. The amplitude of the ATP-induced response is presented as a percentage of the initial control responses. Data are expressed as mean±SEM. *p<0.05 relative to respective non-octyl gallate-treated cells (one way ANOVA followed by Bonferroni's test).

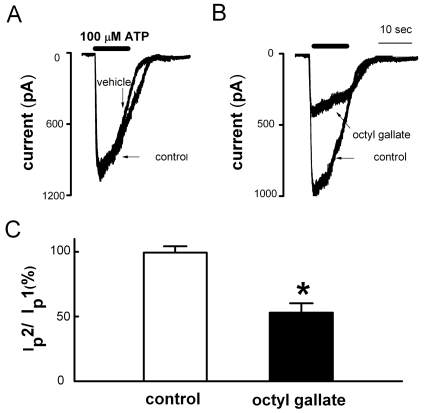

Inhibitory effects of octyl gallate on ATP-induced currents

Activation of P2X receptors by ATP induces the influx of Na+ and Ca2+ across the cell membrane [33]. In this study, the removal of extracellular Ca2+ markedly inhibited the ATP-induced [Ca2+]i increase. The ATP-induced [Ca2+]i increase in thapsigargin-treated cells was also inhibited by treatment with octyl gallate (3 µM). These results suggest that ATP-induced cation currents are inhibited by octyl gallate. A whole-cell voltage clamping technique was next used to investigate whether treatment with octyl gallate could inhibit ATP-induced inward currents at a holding potential of -70 mV. Reproducible ATP-induced inward currents were elicited by treatment with ATP (100 µM) for 10 s at 10 min intervals (Ip2/Ip1=99.3±4.9%, n=9) (Fig. 5A). Pretreatment with octyl gallate (3 µM) for 10 min significantly inhibited the ATP-induced currents (Ip2/Ip1=52.9±7.3%, n=6) (Fig. 5B).

Fig. 5.

Inhibitory effects of octyl gallate on ATP-induced inward currents in PC12 cell. (A) Application of ATP (100 µM, 10 s) evoked inward currents (control). In the same cells, a second application of ATP induced inward current after 10 min washout (vehicle) (n=9). (B) Pretreatment with 3 µM octyl gallate for 10 min inhibited the ATP-induced inward current (octyl gallate, n=6). (C) Summary of the effect of octyl gallate on ATP-induced inward currents. The amplitude of second ATP-induced response (Ip2) is presented as a percentage of the initial control (Ip1) (Ip2/Ip1). Data are expressed as mean±SEM. *p<0.05 relative to control (non-paired student's t-test).

DISCUSSION

The present results demonstrate that octyl gallate clearly inhibits ATP-induced [Ca2+]i increases in PC12 cells, by inhibiting both non-selective P2X receptors from extracellular space and P2Y receptor-induced release of Ca2+ from intracellular stores. In addition, octyl gallate inhibited the ATP-induced currents and the depolarization-induced [Ca2+]i increase.

In this study, the removal of extracellular Ca2+ markedly inhibited the ATP-induced [Ca2+]i increase. Treatment with nimodipine (1 µM) inhibited the ATP-induced [Ca2+]i increase in thapsigargin-treated and non-thapsigargin-treated cells by 49.3% and 41.2%, respectively, confirming our earlier observations [5]. Treatment with octyl gallate further significantly inhibited the ATP-induced response in the presence of nimodipine in untreated or thapsigargin-treated cells, suggesting that the inhibition of Ca2+ influx by octyl gallate may be both nimodipine-sensitive and nimodipine-insensitive. ATP also induces [Ca2+]i increases partly by an influx of non-selective cations, such as Ca2+ and Na+, in PC12 cells [3]. In fact, using a whole-cell voltage-clamping technique in the present study, it was demonstrated that octyl gallate inhibits ATP-induced inward currents. These data suggest that octyl gallate inhibits ATP-induced Ca2+ influx by inhibiting non-selective cation channels.

Octyl gallate inhibits voltage-gated Ca2+ channels in rat pituitary GH4C1 cells [23]. In PC12 cells, ATP induces Ca2+ influx through the secondary activation of voltage-gated Ca2+ channels following depolarization of the membrane by the ATP-induced activation of non-selective cation channels [34]. In addition to L-type voltage-dependent Ca2+ channels, it has been reported that ATP can induce a [Ca2+]i increase in PC12 cells through dihydropyridine- and CTX-insensitive-voltage-dependent Ca2+ channels [34]. In this study, octyl gallate inhibited high KCl-induced [Ca2+]i increase. Treatment with octyl gallate or nimodipine inhibited ATP-induced Ca2+ influx in PC-12 cells. In addition, treatment with octyl gallate further inhibited the ATP-induced Ca2+ influx in the presence of nimodipine. Collectively, these data suggest that octyl gallate inhibits the ATP-induced Ca2+ influx in PC12 cells through inhibition of the secondary activation of voltage-gated L-type Ca2+ channels and dihydropyridine- and CTX-insensitive-voltage-dependent Ca2+ channels.

Phenolic compounds potently inhibit several kinases involved in signal transduction, mainly PKC and tyrosine kinases [31,35-37]. Protein phosphorylation such as tyrosine phosphorylation and serine-thronine phosphorylation can induce Ca2+ influx [32]. ATP induces PLC activation in PC12 cells [5], which can activate PKC. ATP was also found to induce the activation of tyrosine kinase in PC12 cells [38]. In the present study, the nonspecific PKC inhibitor staurosporin and the specific PKC inhibitor GF109203X, and the tyrosine kinase inhibitor genistein did not affect the inhibitory effects of octyl gallate on ATP-induced [Ca2+]i responses, although octyl gallate inhibited the ATP-induced responses in the presence of PKC inhibitors or tyrosine kinase inhibitors. These results indicate that octyl gallate inhibits ATP-induced [Ca2+]i increase in a protein kinase-independent manner.

In this study, octyl gallate inhibited the ATP-induced [Ca2+]i increases in concentration-dependent manner. Pretreatment with the Ca2+-ATPase antagonist thapsigargin decreased the ATP-induced [Ca2+]i responses. Pretreatment with octyl gallate inhibited ATP-induced Ca2+ release from intracellular stores following the removal of extracellular Ca2+. In the present study, however, we could not determine how octyl gallate inhibits the ATP-[Ca2+]i increase through the inhibition of P2Y receptor-mediated signaling.

The inhibitory effects of flavonoid on ion channels have been reported to be mediated by binding to ligand-gated channels, voltage-gated channels, and the membrane lipid bilayer. Apigenin has been reported to inhibit GABA-activated Cl-currents through binding to the benzodiazepine site [39]. Genistein blocked the voltage-sensitive Na+ channels through a direct binding to the channels [40]. (-)-Epigallocatechin-3-gallate (EGCG) inhibits rKv1.5 channels [41]. In addition, polyphenols have also been reported to interact with the membrane lipid bilayer to exert their biological functions [42,43]. Membrane lipid can affect ion channel structure and fuction [44]. Collectively, it is possible that octyl gallate in the present study exerted inhibition effects by directly binding to the P2X receptors and IP3 receptor or L-type Ca2+ channels and then reducing allosteric inhibition of the channels. However, the present study has provided no further information on how octyl gallate might exert its inhibitory effects on channels at molecular level.

ATP is a widely distributed neurotransmitter and neuromodulator in the peripheral and central nervous system [1,2]. ATP receptors regulate various functions including the release of neurotransmitters in the peripheral and central nervous systems [45-47]. ATP-induced [Ca2+]i increases in PC12 cells may be involved in the cell death [27]. The present study provides available information that octyl gallate inhibits ATP-induced [Ca2+]i increases by inhibiting multiple pathways. More research is needed to assess the alleged heath benefits of octyl gallate including synaptic transmission and neuroprotective effect by modulating calcium homeostasis.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This research was supported by a grant No. R13-2002-005-04001-0 (2009) from the Medical Research Center, Korea Science and Engineering Foundation, Republic of Korea.

ABBREVIATIONS

- AM

acetoxymethylester

- DMEM

Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium

- FBS

fetal bovine serum

- HS

horse serum

- HEPES-HBSS

HEPES-buffered Hanks's solution

- PKC

protein kinase C

- PLC

phospholipase C

- EGCG

(-)-epigallocatechin-3-gallate

References

- 1.Jahr CE, Jessell TM. ATP excites a subpopulation of rat dorsal horn neurones. Nature. 1983;304:730–733. doi: 10.1038/304730a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Inoue K. ATP receptors for the protection of hippocampal functions. Jpn J Pharmacol. 1998;78:405–410. doi: 10.1254/jjp.78.405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fasolato C, Pizzo P, Pozzan T. Receptor-mediated calcium influx in PC12 cells. ATP and bradykinin activate two independent pathways. J Biol Chem. 1990;265:20351–20355. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Murrin RJ, Boarder MR. Neuronal "nucleotide" receptor linked to phospholipase C and phospholipase D: Stimulation of PC12 cells by ATP analogues and UTP. Mol Pharmacol. 1992;41:561–568. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kim HJ, Choi JS, Lee YM, Shim EY, Hong SH, Kim MJ, Min DS, Rhie DJ, Kim MS, Jo YH, Hahn SJ, Yoon SH. Fluoxetine inhibits ATP-induced [Ca2+]i increase in PC12 cells by inhibiting both extracellular Ca2+ influx and Ca2+ release from intracellular stores. Neuropharmacology. 2005;49:265–274. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2005.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Manach C, Mazur A, Scalbert A. Polyphenols and prevention of cardiovascular diseases. Curr Opin Lipidol. 2005;16:77–84. doi: 10.1097/00041433-200502000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Duthie SJ. Berry phytochemicals, genomic stability and cancer: evidence for chemoprotection at several stages in the carcinogenic process. Mol Nutr Food Res. 2007;51:665–674. doi: 10.1002/mnfr.200600257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Levites Y, Amit T, Mandel S, Youdim MB. Neuroprotection and neurorescue against Abeta toxicity and PKC-dependent release of nonamyloidogenic soluble precursor protein by green tea polyphenol (-)-epigallocatechin-3-gallate. FASEB J. 2003;17:952–954. doi: 10.1096/fj.02-0881fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ono K, Yoshiike Y, Takashima A, Hasegawa K, Naiki H, Yamada M. Potent anti-amyloidogenic and fibril-destabilizing effects of polyphenols in vitro: implications for the prevention and therapeutics of Alzheimer's disease. J Neurochem. 2003;87:172–181. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2003.01976.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ramassamy C. Emerging role of polyphenolic compounds in the treatment of neurodegenerative diseases: a review of their intracellular targets. Eur J Pharmacol. 2006;545:51–64. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2006.06.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Silva JP, Proenca F, Coutinho OP. Protective role of new nitrogen compounds on ROS/RNS-mediated damage to PC12 cells. Free Radic Res. 2008;42:57–69. doi: 10.1080/10715760701787719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zhao B. Natural antioxidants protect neurons in Alzheimer's disease and Parkinson's disease. Neurochem Res. 2009;34:630–638. doi: 10.1007/s11064-008-9900-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bastianetto S, Yao ZX, Papadopoulos V, Quirion R. Neuroprotective effects of green and black teas and their catechin gallate esters against beta-amyloid-induced toxicity. Eur J Neurosci. 2006;23:55–64. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2005.04532.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ko FN, Huang TF, Teng CM. Vasodilatory action mechanisms of apigenin isolated from Apium graveolens in rat thoracic aorta. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1991;1115:69–74. doi: 10.1016/0304-4165(91)90013-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Saponara S, Sgaragli G, Fusi F. Quercetin as a novel activator of L-type Ca2+ channels in rat tail artery smooth muscle cells. Br J Pharmacol. 2002;135:1819–1827. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0704631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Losi G, Puia G, Garzon G, de Vuono MC, Baraldi M. Apigenin modulates GABAergic and glutamatergic transmission in cultured cortical neurons. Eur J Pharmacol. 2004;502:41–46. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2004.08.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kim HJ, Yum KS, Sung JH, Rhie DJ, Kim MJ, Min do S, Hahn SJ, Kim MS, Jo YH, Yoon SH. Epigallocatechin-3-gallate increases intracellular [Ca2+]i in U87 cells mainly by influx of extracellular Ca2+ and partly by release of intracellular stores. Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch Pharmacol. 2004;369:260–267. doi: 10.1007/s00210-003-0852-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Formica JV, Regelson W. Review of the biology of quercetin and related bioflavonoids. Food Chem Toxicol. 1995;33:1061–1080. doi: 10.1016/0278-6915(95)00077-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Han JH, Kim KJ, Jang HJ, Jang JH, Kim MJ, Sung KW, Rhie DJ, Jo YH, Hahn SJ, Lee MY, Yoon SH. Effects of apigenin on glutamate-induced [Ca2+]i Increases in aultured rat hippocampal neurons. Kor J Physiol Pharmacol. 2008;12:43–50. doi: 10.4196/kjpp.2008.12.2.43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lin F, Xin Y, Wang J, Ma L, Liu J, Liu C, Long L, Wang F, Jin Y, Zhou J, Chen J. Puerarin facilitates Ca2+-induced Ca2+ release triggered by KCl-depolarization in primary cultured rat hippocampal neurons. Eur J Pharmacol. 2007;570:43–49. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2007.05.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ban JY, Jeon SY, Bae K, Song KS, Seong YH. Catechin and epicatechin from Smilacis chinae rhizome protect cultured rat cortical neurons against amyloid beta protein (25-35)-induced neurotoxicity through inhibition of cytosolic calcium elevation. Life Sci. 2006;79:2251–2259. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2006.07.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Shimmyo Y, Kihara T, Akaike A, Niidome T, Sugimoto H. Three distinct neuroprotective functions of myricetin against glutamate-induced neuronal cell death: involvement of direct inhibition of caspase-3. J Neurosci Res. 2008;86:1836–1845. doi: 10.1002/jnr.21629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Summanen J, Vuorela P, Rauha JP, Tammela P, Marjamaki K, Pasternack M, Tornquist K, Vuorela H. Effects of simple aromatic compounds and flavonoids on Ca2+ fluxes in rat pituitary GH4C1 cells. Eur J Pharmacol. 2001;414:125–133. doi: 10.1016/s0014-2999(01)00774-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Majid MA, Okajima F, Kondo Y. Characterization of ATP receptor which mediates norepinephrine release in PC12 cells. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1992;1136:283–289. doi: 10.1016/0167-4889(92)90118-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nakazawa K, Inoue K. Roles of Ca2+ influx through ATP-activated channels in catecholamine release from pheochromocytoma PC12 cells. J Neurophysiol. 1992;68:2026–2032. doi: 10.1152/jn.1992.68.6.2026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Suh BC, Lee CO, Kim KT. Signal flows from two phospholipase C-linked receptors are independent in PC12 cells. J Neurochem. 1995;64:1071–1079. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1995.64031071.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sun AY, Chen YM. Extracellular ATP-induced apoptosis in PC12 cells. Adv Exp Med Biol. 1998;446:73–83. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4615-4869-0_5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rhie DJ, Sung JH, Kim HJ, Ha US, Min DS, Kim MS, Jo YH, Hahn SJ, Yoon SH. Endogenous somatostatin receptors mobilize calcium from inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate-sensitive stores in NG108-15 cells. Brain Res. 2003;975:120–128. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(03)02596-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Choi JS, Choi BH, Ahn HS, Kim MJ, Rhie DJ, Yoon SH, Min do S, Jo YH, Kim MS, Sung KW, Hahn SJ. Mechanism of block by fluoxetine of 5-hydroxytryptamine3 (5-HT3)-mediated currents in NCB-20 neuroblastoma cells. Biochem Pharmacol. 2003;66:2125–2132. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2003.08.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Thastrup O, Cullen PJ, Drobak BK, Hanley MR, Dawson AP. Thapsigargin, a tumor promoter, discharges intracellular Ca2+ stores by specific inhibition of the endoplasmic reticulum Ca2+-ATPase. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1990;87:2466–2470. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.7.2466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Agullo G, Gamet-Payrastre L, Manenti S, Viala C, Remesy C, Chap H, Payrastre B. Relationship between flavonoid structure and inhibition of phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase: a comparison with tyrosine kinase and protein kinase C inhibition. Biochem Pharmacol. 1997;53:1649–1657. doi: 10.1016/s0006-2952(97)82453-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Munaron L, Distasi C, Carabelli V, Baccino FM, Bonelli G, Lovisolo D. Sustained calcium influx activated by basic fibroblast growth factor in Balb-c 3T3 fibroblasts. J Physiol. 1995;484:557–566. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1995.sp020686. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nakazawa K, Fujimori K, Takanaka A, Inoue K. An ATP-activated conductance in pheochromocytoma cells and its suppression by extracellular calcium. J Physiol. 1990;428:257–272. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1990.sp018211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gollasch M, Haller H. Multiple pathways for ATP-induced intracellular calcium elevation in pheochromocytoma (PC12) cells. Ren Physiol Biochem. 1995;18:57–65. doi: 10.1159/000173900. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ferriola PC, Cody V, Middleton E., Jr Protein kinase C inhibition by plant flavonoids. Kinetic mechanisms and structure-activity relationships. Biochem Pharmacol. 1989;38:1617–1624. doi: 10.1016/0006-2952(89)90309-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Duarte J, Perez Vizcaino F, Utrilla P, Jimenez J, Tamargo J, Zarzuelo A. Vasodilatory effects of flavonoids in rat aortic smooth muscle. Structure-activity relationships. Gen Pharmacol. 1993;24:857–862. doi: 10.1016/0306-3623(93)90159-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Revuelta MP, Cantabrana B, Hidalgo A. Depolarization-dependent effect of flavonoids in rat uterine smooth muscle contraction elicited by CaCl2. Gen Pharmacol. 1997;29:847–857. doi: 10.1016/s0306-3623(97)00002-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.DAmbrosi N, Murra B, Cavaliere F, Amadio S, Bernardi G, Burnstock G, Volonte C. Interaction between ATP and nerve growth factor signalling in the survival and neuritic outgrowth from PC12 cells. Neuroscience. 2001;108:527–534. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(01)00431-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Avallone R, Zanoli P, Puia G, Kleinschnitz M, Schreier P, Baraldi M. Pharmacological profile of apigenin, a flavonoid isolated from Matricaria chamomilla. Biochem Pharmacol. 2000;59:1387–1394. doi: 10.1016/s0006-2952(00)00264-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Paillart C, Carlier E, Guedin D, Dargent B, Couraud F. Direct block of voltage-sensitive sodium channels by genistein, a tyrosine kinase inhibitor. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1997;280:521–526. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Choi BH, Choi JS, Min DS, Yoon SH, Rhie DJ, Jo YH, Kim MS, Hahn SJ. Effects of (-)-epigallocatechin-3-gallate, the main component of green tea, on the cloned rat brain Kv1.5 potassium channels. Biochem Pharmacol. 2001;62:527–535. doi: 10.1016/s0006-2952(01)00678-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hendrich AB, Malon R, Pola A, Shirataki Y, Motohashi N, Michalak K. Differential interaction of Sophora isoflavonoids with lipid bilayers. Eur J Pharm Sci. 2002;16:201–208. doi: 10.1016/s0928-0987(02)00106-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hendrich AB. Flavonoid-membrane interactions: possible consequences for biological effects of some polyphenolic compounds. Acta Pharmacol Sin. 2006;27:27–40. doi: 10.1111/j.1745-7254.2006.00238.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Tillman TS, Cascio M. Effects of membrane lipids on ion channel structure and function. Cell Biochem Biophys. 2003;38:161–190. doi: 10.1385/CBB:38:2:161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Zhang YX, Yamashita H, Ohshita T, Sawamoto N, Nakamura S. ATP increases extracellular dopamine level through stimulation of P2Y purinoceptors in the rat striatum. Brain Res. 1995;691:205–212. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(95)00676-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Cunha RA, Ribeiro JA. ATP as a presynaptic modulator. Life Sci. 2000;68:119–137. doi: 10.1016/s0024-3205(00)00923-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Choi YM, Jang JY, Jang M, Kim SH, Kang YK, Cho H, Chung S, Park MK. Modulation of firing activity by ATP in dopamine neurons of the rat substantia nigra pars compacta. Neuroscience. 2009;160:587–595. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2009.02.067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]