Abstract

Background

Anxiety disorders and pain are commonly comorbid, though little is known about the effect of pain on the course and treatment of anxiety.

Methods

This is a secondary analysis of a randomized controlled trial for anxiety treatment in primary care. Participants with panic disorder (PD) and/or generalized anxiety disorder (GAD) (N = 191; 81% female, mean age 44) were randomized to either their primary-care physician’s usual care or a 12-month course of telephone-based collaborative care. Anxiety severity, pain interference, health-related quality of life, health services use, and employment status were assessed at baseline, and at 2-, 4-, 8-, and 12-month follow-up. We defined response to anxiety treatment as a 40% or greater improvement from baseline on anxiety severity scales at 12-month follow-up.

Results

The 39% who reported high pain interference at baseline had more severe anxiety (mean SIGH-A score: 21.8 versus 18.0, P<.001), greater limitations in activities of daily living, and more work days missed in the previous month (5.8 versus 4.0 days, P = .01) than those with low pain interference. At 12-month follow-up, high pain interference was associated with a lower likelihood of responding to anxiety treatment (OR = .28; 95% CI = .12–.63) and higher health services use (26.1% with ≥1 hospitalization versus 12.0%, P<.001).

Conclusions

Pain that interferes with daily activities is prevalent among primary care patients with PD/GAD and associated with more severe anxiety, worse daily functioning, higher health services use, and a lower likelihood of responding to treatment for PD/GAD.

Keywords: anxiety disorders, pain, primary care, activities of daily living

INTRODUCTION

Generalized anxiety disorder (GAD) and panic disorder (PD) are common among primary care patients, with an estimated prevalence of 12–18%.[1,2] These anxiety disorders are associated with significant healthcare utilization[3,4] and an estimated $50 billion per year in excess healthcare costs.[5,6] Despite negative consequences of untreated anxiety, it frequently remains undetected by primary-care physicians PCPs.[7]

People with anxiety disorders frequently report somatic pain.[8] The National Comorbidity Study[9] and the World Mental Health Surveys,[10] have found evidence for a relationship between painful conditions, such as arthritis or chronic back pain and anxiety disorders. People with an anxiety disorder are 2 to 3 times more likely to have a painful condition than others without an anxiety disorder[9], and among people with chronic back or neck pain, the odds of having an anxiety disorder are 2 to 3 times higher than for those without chronic pain.[10]

Although anxiety and pain are frequently comorbid,[11] little is known about the effects of pain on the course and treatment of anxiety disorders. The purpose of this study was to describe the relationship between pain that interferes with daily activities and improvement in the DSM-IV-defined anxiety disorders of GAD and PD among patients with either one or both of these conditions who participated in a randomized clinical trial of an effective primary-care-based collaborative care intervention.[12] We hypothesized that (1) greater pain interference would reduce the response to treatment for anxiety over the course of 12 months; (2) anxiety severity would be positively associated with pain interference; and (3) greater pain interference would negatively affect functional status, health services use, and occupational functioning, before and after treatment for anxiety.

METHODS

SETTING AND PARTICIPANTS

Detailed descriptions of the trial recruitment, assessment, and intervention procedures have been published previously.[12,13] Briefly, we recruited 191 patients aged 18–64, who currently met DSM-IV criteria for PD and/or GAD and had at least a moderate level of anxiety symptoms as measured by the Hamilton Anxiety Rating Scale (≥14) and the Panic Disorder Severity Scale (PDSS) (≥7), from four Pittsburgh-area primary-care practices that shared a common electronic medical record (EMR). Eligible participants were not receiving treatment from a mental health professional, had no obvious dementia, psychotic illness, bipolar disorder, unstable medical conditions that would preclude treatment of their anxiety disorder, had no alcohol abuse or dependence, or communication barriers. They were randomized to either (1) a telephone-based information/self-management program for PD/GAD delivered to participants and PCPs by an anxiety care manager[13] or (2) participant and PCP notification of the PD/GAD diagnosis alone (“usual care”). The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the University of Pittsburgh, and all subjects provided written informed consent prior to their participation.

PROCEDURE

Intervention participants were assigned an anxiety care manager who provided psychoeducation about anxiety disorders, assessed treatment preferences, and taught self-management skills through the guided use of workbooks for managing PD/GAD. The intervention did not specifically address pain or pain treatment. Care managers coordinated care with PCPs via the EMR and made guideline-based treatment recommendations depending on participant preference and response to treatment. PCPs were free to accept or reject these recommendations and were responsible for prescribing pharmacotherapy.[13]

MEASUREMENTS

Sociodemographic characteristics

Sociodemographic variables were collected by self-report and included participants’ age, gender, race, education, and marital status. A trained study nurse conducted detailed chart abstractions to determine the prevalence of (1) any comorbid medical conditions and (2) any painful conditions (e.g. osteoarthritis, rheumatoid arthritis, fibromyalgia, chronic low back pain, migraine headache, myalgia and myositis, cervicalgia, chronic foot pain, hip pain, shoulder pain, or plantar fasciitis) in our study population.

Pain interference

We assessed pain in this population using a measure of the extent to which pain interfered with daily activities. Pain interference was assessed at baseline, 4-, and 12-month follow-up using a single item from the Medical Outcomes Study SF-12: “During the past four weeks, how much did pain interfere with your normal work (including both work outside the home and housework)”.[14] We classified patients who responded “not at all” or “a little bit” as “low pain interference,” and patients who responded “moderately,” “quite a bit,” or “a lot” as “high pain interference.” This approach has been used previously in other population-based surveys of pain.[15–17]

Anxiety

We assessed anxiety severity at baseline, 2-, 4-, 8-, and 12-month follow-up using the Structured Interview Guide for the Hamilton Anxiety Rating Scale (SIGH-A),[18] the Panic Disorder Severity Scale,[19] and the Generalized Anxiety Disorder Severity Scale (GADSS).[20] We defined response to anxiety treatment as a 40% or greater improvement on these scales from baseline.[20,21]

Health Related Quality Of Life (HRQOL) and depression

HRQOL was assessed at baseline, 4, and 12 months using the SF-12 mental health component summary score (MCS).[22] We did not use the SF-12 physical health component summary score, as the measure of pain interference is included in this summary score. Data on employment status, number of hours worked, and days of work missed were collected at baseline and 12 months by self-report. Depression was assessed at baseline, 2, 4, 8, and 12 months using the Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression (HRSD).[23]

Health services use

We conducted chart reviews to determine the type and dosage of pain medications and antidepressant that patients had been prescribed. Health services use was determined by review of the EMR; we calculated the number of PCP contacts, emergency department (ER) visits, and hospitalizations (medical or psychiatric).

STATISTICAL ANALYSES

Cross-sectional analyses

To assess whether there were underlying clinical and demographic differences between patients with high and low pain interference in this sample, we used tests of comparison (t test and χ2) to explore these differences at baseline across a wide range of variables.

To assess the effect of pain interference on healthcare use in the previous 12 months, we used (1) a Poisson regression model for the number of PCP visits, (2) a zero-inflated Poisson regression model for the number of ER visits and hospitalizations,[24] and (3) logistic regression for binomial measures of ER visits and hospitalizations (≥1 and ≥2 visits/hospitalizations). We used linear and logistic regression to assess the effect of pain interference on employment characteristics at 12 months. All models controlled for intervention status, race, major depression, and the number of comorbid physical conditions.

Longitudinal analyses

To assess the main effect of pain interference on response to anxiety treatment, our primary outcome, we used logistic regression to model the effect of pain interference on the dichotomous outcome of whether a 40% reduction on anxiety scores was achieved at 12 months. We controlled for intervention status, baseline anxiety scores, and variables that differed between the high and low pain interference groups and could have an effect on the outcome measure: race, whether or not the patient had a comorbid diagnosis of major depression, and number of comorbid physical conditions.

Next, we examined whether the effect of pain interference on response to anxiety treatment differed by intervention status. We used logistic regression models to explore the interaction between pain interference and intervention status on our main dependent variable, response to anxiety treatment, as defined by a 40% or greater reduction in SIGH-A, GADSS, PDSS, and MCS scores from baseline. To ensure that the dichotomized outcome would not compromise the statistical power, we also used linear regression models to explore the interaction between pain interference and intervention status on 12-month relative change for each of the anxiety scales.

RESULTS

PATIENT CHARACTERISTICS

We describe the characteristics of the 191 patients with GAD and/or PD who were included in these analyses, by pain interference status, in Table 1. Overall, 81% were female, 95% were White, and the mean age was 44. Two thirds had at least a high school education and 74% were married. Most patients had GAD either alone (42%) or in combination with PD (48%). In addition, the majority (57%) met criteria for major depressive disorder.

TABLE 1.

Baseline Sociodemographic and Clinical Characteristics

| Overall (n = 191) | Low pain interference (n = 75) | High pain interference (n = 116) | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sociodemographic characteristics | ||||

| Mean age (SD) | 44.2 (10.7) | 43.2 (9.5) | 44.8 (11.4) | .31 |

| Female, No. (%) | 115 (81) | 61 (81) | 94 (81) | .95 |

| Caucasian, No. (%) | 182 (95) | 75 (100) | 107 (92) | <.05 |

| >High school education, No. (%) | 123 (64) | 48 (64) | 75 (65) | .93 |

| Married, No. (%) | 140 (74) | 60 (80) | 80 (71) | .12 |

| Clinical characteristics | ||||

| Anxiety diagnosis, No. (%) | .69 | |||

| GAD | 80 (42) | 33 (44) | 47 (41) | |

| PD | 20 (10) | 9 (12) | 11 (9) | |

| GAD/PD | 91 (48) | 33 (44) | 58 (50) | |

| Major depressive disorder | 108 (57) | 34 (45) | 74 (64) | <.05 |

| Mean SIGH-A (SD) | 20.3 (6.4) | 18.0 (5.0) | 21.8 (6.8) | <.001 |

| Mean PDSS (SD) | 8.5 (6.0) | 7.3 (5.7) | 9.2 (6.3) | <.05 |

| Mean GADS, (SD) | 12.8 (4.3) | 11.6 (3.7) | 13.6 (4.4) | <.01 |

| Mean HRS-D (SD) | 17.4 (6.5) | 15.7 (5.9) | 18.2 (6.7) | <.05 |

| Mean SF-12 MCS (SD) | 30.3 (9.5) | 30.5 (9.2) | 30.2 (9.7) | .86 |

| Comorbid medical conditions | ||||

| Mean no. comborbid conditions (SD) | 2.4 (1.9) | 2.0 (1.5) | 2.8 (2.1) | <.01 |

| Have a painful conditiona, No. (%) | 62 (32) | 24 (32) | 38 (33) | .91 |

| Baseline medications | ||||

| Antidepressant medicationsb, No. (%) | 60 (31.4) | 23 (30.7) | 37 (31.9) | .86 |

| Pain medication use, No. (%) | ||||

| Opiods | 11 (5.8) | 1 (1.3) | 10 (8.6) | .04 |

| Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory | 21 (11) | 8 (10.7) | 13 (11.2) | .91 |

| Baseline ADL limitations | ||||

| Moderate activities, No. (%) | <.001 | |||

| No, not limited at all | 124 (64.9) | 67 (89.3) | 57 (49.1) | |

| Yes, limited a little | 34 (17.8) | 6 (8.0) | 28 (24.1) | |

| Yes, limited a lot | 33 (17.3) | 2 (2.7) | 31 (26.7) | |

| Climbing several flights of stairs, No. (%) | <.001 | |||

| No, not limited at all | 109 (57.1) | 59 (78.7) | 50 (43.1) | |

| Yes, limited a little | 39 (20.4) | 11 (14.7) | 28 (24.1) | |

| Yes, limited a lot | 43 (22.5) | 5 (6.7) | 38 (32.8) | |

| Baseline employment characteristics | ||||

| Working, part-time or full-time, No. (%) | 116 (61.0) | 46 (61.0) | 70 (60.0) | .89 |

| Hours worked per week, mean (SD) | 39.2 (12.9) | 39.0 (13.7) | 39.3 (12.2) | .90 |

| Work days absent in past month, mean (SD) | 3.0 (5.3) | 1.9 (4.0) | 3.6 (5.8) | .02 |

Pain conditions: Osteoarthritis, rheumatoid arthritis, fibromyalgia, chronic low back pain, migraine headache, myalgia and myositis, cervicalgia, chronic foot pain, hip pain, shoulder pain, and plantar fasciitis.

Includes selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRI), serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRI), tricyclic antidepressants, and other antidepressants.

GAD, generalized anxiety disorder; PD, panic disorder; SIGH-A, structured Interview Guide for the Hamilton Anxiety Rating Scale; PDSS, Panic Disorder Severity Scale; GADSS, Generalized Anxiety Disorder Severity Scale; HRS, Hamilton Depression Rating Scale; MCS, mental health component summary score.

At baseline, 39% (75) of the participants endorsed “low pain interference” and 61% (116) had “high pain interference.” There were no differences between the two groups in the frequency of physician-diagnosed painful conditions. However, the high pain interference group was more likely to be prescribed opiods (1.3 versus 8.6%, P<.05).

PAIN INTERFERENCE ASSOCIATION WITH BASELINE ANXIETY SEVERITY AND HRQOL

High pain interference patients reported higher anxiety levels on the SIGH-A (21.8 versus 18.0; P<.001), PDSS (9.2 versus 7.3; P<.05), and the GADSS (13.6 versus 11.6; P<.01), indicating more severe anxiety symptoms (Table 1). Participants with high pain interference also scored higher on the HRS-D (18.2 versus 15.7, P<.05), indicating more severe depression symptoms, and in fact were more likely to meet criteria for major depressive disorder (64% versus 45%, P<.05).

High and low pain interference patients reported similar levels of HRQOL, as measured by the SF-12 MCS, although high pain interference patients expressed significantly greater limitations in moderate activities (26.7% “limited a lot” versus 2.7%; P<.001).

PAIN INTERFERENCE ASSOCIATION WITH HEALTH SERVICES USE AND EMPLOYMENT

As shown in Table 2, high pain interference patients reported more PCP visits (6 versus 4.5; P<.001), telephone contacts (1 versus .5; P = .03), and total contacts (7 versus 6; P<.001) at 12-months follow-up than low pain interference patients. Additionally, high pain interference patients reported more ER visits (≥1 visit, 49.6 versus 29.3%; P<.001) and hospitalizations (≥1 hospitalization, 26.1 versus 12.0%; P<.001) at 12-month follow-up. We did not find any significant differences in employment characteristics.

TABLE 2.

12-month health care use and employment

| Overall (N = 191) | Low pain (N = 75) | High pain (N = 116) | P-Valuea | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Healthcare use (in previous 12 months) | ||||

| Median (range) total PCP visits | 5.5 (0–23) | 4.5 (1–13) | 6 (0–23) | <.001b |

| Median (range) total PCP telephone calls | 1 (0–17) | 0.5 (0–10) | 1 (0–17) | .03 |

| Median (range) total PCP contacts | 6 (0–34) | 6 (1–20) | 7 (0–34) | <.001 |

| Median (range) ER department visits | 0 (0–6) | 0 (0–2) | 0 (0–6) | <.001b |

| ≥1 ER visits, No. (%) | 79 (49.6) | 22 (29.3) | 57 (49.6) | <.001 |

| ≥2 ER visits, No. (%) | 30 (15.8) | 3 (4.0) | 27 (23.5) | <.001 |

| Median (range) hospitalizations | 0 (0–6) | 0 (0–2) | 0 (0–6) | <.001 |

| ≥1 hospitalization, No. (%) | 39 (20.5) | 9 (12.0) | 30 (26.1) | <.001 |

| ≥2 hospitalizations, No. (%) | 4 (2.1) | 0 (.0) | 4 (3.5) | .92 |

| Employment characteristics | ||||

| Working, part-time or full-time, No. (%) | 87 (61.0) | 35 (70.0) | 52 (55.9) | .10 |

| Hours worked per week, mean (SD) | 39.9 (15.5) | 40.0 (16.3) | 39.8 (15.1) | .77 |

| Work days absent in past month, mean (SD) | 2.8 (6.0) | 1.9 (4.1) | 3.6 (6.8) | .16 |

Adjusted for intervention status, race, depression, and number of comorbid conditions.

Zero-inflated Poisson model used because more than half of values were zeros.

PCP, primary-care physicians; ER, emergency department.

PAIN INTERFERENCE ASSOCIATION WITH RESPONSE TO ANXIETY TREATMENT

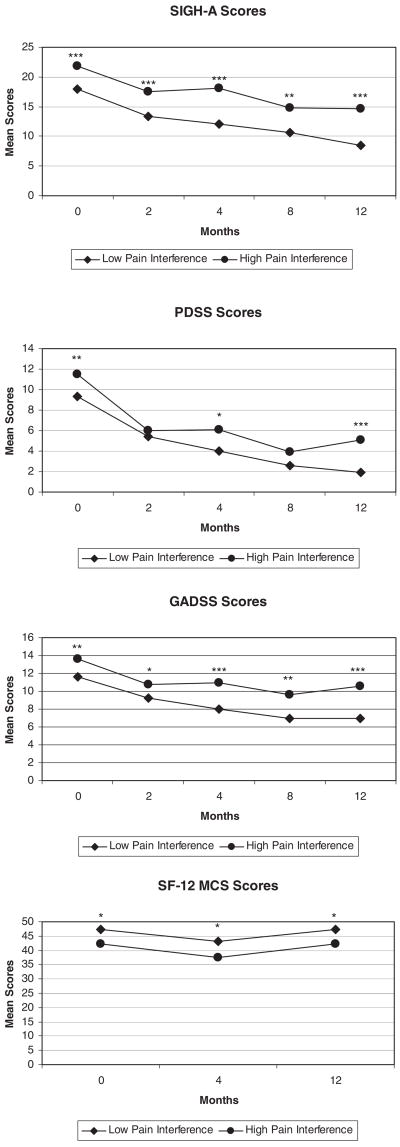

As displayed in Table 3, we found a consistent main effect of high pain interference on rates of anxiety treatment response. Specifically, high pain interference patients were much less likely to achieve a 40% or greater reduction in anxiety symptoms at 12-months follow-up, based on SIGH-A scores (odds ratio, OR = .28; 95% confidence interval, CI = .12–.63), PDSS scores (OR = .28; 95% CI = .11–.71), and GADSS scores (OR = .26; 95% CI = .11–.60). High pain interference patients were also less likely to have a 40% or greater reduction in depression (HRSD) scores (OR = .20; 95% CI = .08–.54) and the MCS of the SF-12 (OR = .41; 95% CI = .18–.94). We illustrate this further in Figure 1, which portray that high pain interference patients have higher scores on all anxiety scales at baseline and continue to have higher scores over the course of follow-up.

TABLE 3.

Main Effect of High Pain Interference on ≥40% Improvement in Measures of Anxiety at 12-month Follow-upa

| Anxiety Scales | Odds ratio | 95% CI | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| SIGH-A | 0.28 | 0.12–0.63 | 0.002 |

| PDSS | 0.28 | 0.11–0.71 | 0.007 |

| GADSS | 0.26 | 0.11–0.60 | 0.002 |

| HRS-D | 0.20 | 0.08–0.54 | 0.001 |

| SF-12 MCS | 0.41 | 0.18–0.94 | 0.03 |

All models adjusted for intervention status, baseline anxiety scores, race, major depression, and number of comorbid medical conditions. SIGH-A, structured Interview Guide for the Hamilton Anxiety Rating Scale; PDSS, Panic Disorder Severity Scale; GADSS, Generalized Anxiety Disorder Severity Scale; HRSD, Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression; MCS, mental health component summary score.

Figure 1.

Anxiety scores over time, by pain status (***p<.001, **p<.01, *p<.05).

Using the dichotomized outcome, we did not find an interaction effect between intervention status and pain interference. However, the effect of the intervention on relative improvement on the PDSS scale differed for those with high and low pain interference (β = −.50; P = .04). For those with high pain interference, receiving the intervention was associated with greater relative improvement than the usual care group. For those with low pain interference, there was not a significant difference between those in the intervention and usual care groups. There were not significant interaction effects for any of the other anxiety measures.

DISCUSSION

This report demonstrates that primary care patients with GAD and/or PD who report high levels of pain interference with their normal daily activities are less likely to respond to anxiety treatment within 12 months than are patients with no or low pain interference. In addition, this report finds that anxious patients with high pain interference have more severe anxiety, more ADL limitations, more ER visits and hospitalizations, and more days absent from work in the past month than those with no or low pain interference.

Pain and anxiety are closely related conditions.[11] Indeed, a high amount of pain-related anxiety and its associated fear avoidance behavior[25] has been associated with the development of chronic low back pain and pain-related disability.[26] It has been shown that increased vigilance to somatic experience and exaggerated interpretation of sensory stimuli occurs in adults who report higher levels of baseline anxiety,[27,28] and may partially explain the increased prevalence of a chronic painful condition in this population. Neurobiological studies also implicate similar regions in the brain for both anxiety and pain,[29] and trials of antidepressants for patients with GAD and pain found that this medication worked to reduce both types of symptoms,[30], suggesting a linked neurobiology.

Our findings suggest that pain interference and anxiety disorders frequently present together and may complicate treatment. High pain interference is associated with a reduced response to anxiety treatment over 12 months and may affect response to anxiety treatment interventions. It is important, therefore, that physicians treating pain or anxiety also assess the patient for the other condition and deliver treatments accordingly. However, patients suffering from anxiety disorders[7,31] and pain[32]) often receive inadequate treatment. Our finding that people with high pain interference are no more likely than those with low pain interference to take antidepressant medication suggests this. Thus, untreated pain may be a risk factor for anxiety and arguably the reverse may also be true. The challenge exists to streamline care to allow physicians to coordinate treatment of mental and physical health conditions simultaneously.

There are several limitations to this study. Our sample consisted of predominantly white, well-educated women and thus we cannot generalize our findings to the general population. However, as we enrolled patients from four primary-care practices (urban-academic, suburban, and rural), reflecting the demographics of the Pittsburgh region, our results are likely generalizable to other primary-care populations. We were also limited to one measure of pain, which only assessed pain interference. We did not assess the intensity or duration of pain and did not have data from multidimensional measures such as the McGill Pain Questionnaire[33]. Our findings are also limited by our inability to detect differences in the effect of pain interference by anxiety diagnosis due to small sample size. Finally, as both pain interference and anxiety measures were collected contemporaneously, we cannot determine any casual effect between these conditions. The directionality of the relationship is unknown. Future research using longitudinal methods and additional pain measures will be able to elucidate this issue.

Primary-care patients with GAD and/or PD and high pain interference have a lower likelihood of responding to anxiety treatment within 12 months. These findings emphasize the importance of understanding the effects of comorbid physical conditions on the course and response to treatment of anxiety disorders. Future studies should determine whether anxiety disorders similarly adversely affect the treatment of pain and should modify interventions to address the treatment of pain in the presence of anxiety disorders and vice versa.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge funding support for this research from the National Institute of Mental Health (R01 MH09421 and T32 MH19986). Drs. Morone and Karp are supported by the NIH Roadmap Multidisciplinary Clinical Research Career Development Award Grant (1KL2RR024154-01) from the National Center for Research Resources (NCRR), a component of the National Institutes of Health (NIH), and NIH Roadmap for Medical Research.

Contract grant sponsor: National Institute of Mental Health; Contract grant numbers: R01 MH09421; T32 MH19986; Contract grant sponsor: NIH Roadmap Multidisciplinary Clinical Research Career Development Award Grant; Contract grant number: 1KL2RR024154-01); Contract grant sponsor: National Center for Research Resources (NCRR); Contract grant sponsor: NIH Roadmap for Medical Research.

References

- 1.Kessler RC, Chiu WT, Demler O, Merikangas KR, Walters EE. Prevalence, severity, and comorbidity of 12-month DSM-IV disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2005;62:617–627. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.62.6.617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Narrow WE, Rae DS, Robins LN, Regier DA. Revised prevalence estimates of mental disorders in the United States: using a clinical significance criterion to reconcile 2 surveys’ estimates. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2002;59:115–123. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.59.2.115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Deacon B, Lickel J, Abramowitz JS. Medical utilization across the anxiety disorders. J Anxiety Disord. 2008;22:344–350. doi: 10.1016/j.janxdis.2007.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nease DE, Jr, Volk RJ, Cass AR. Does the severity of mood and anxiety symptoms predict health care utilization? J Fam Pract. 1999;48:769–777. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Marciniak M, Lage MJ, Landbloom RP, Dunayevich E, Bowman L. Medical and productivity costs of anxiety disorders: case control study. Depress Anxiety. 2004;19:112–120. doi: 10.1002/da.10131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Marciniak MD, Lage MJ, Dunayevich E, et al. The cost of treating anxiety: the medical and demographic correlates that impact total medical costs. Depress Anxiety. 2005;21:178–184. doi: 10.1002/da.20074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB, Monahan PO, Lowe B. Anxiety disorders in primary care: prevalence, impairment, comorbidity, and detection. Ann Intern Med. 2007;146:317–325. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-146-5-200703060-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB, et al. Physical symptoms in primary care. Predictors of psychiatric disorders and functional impairment. Arch Fam Med. 1994;3:774–779. doi: 10.1001/archfami.3.9.774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sareen J, Cox BJ, Clara I, Asmundson GJ. The relationship between anxiety disorders and physical disorders in the US National Comorbidity Survey. Depress Anxiety. 2005;21:193–202. doi: 10.1002/da.20072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Demyttenaere K, Bruffaerts R, Lee S, et al. Mental disorders among persons with chronic back or neck pain: results from the World Mental Health Surveys. Pain. 2007;129:332–342. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2007.01.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.McWilliams LA, Goodwin RD, Cox BJ. Depression and anxiety associated with three pain conditions: results from a nationally representative sample. Pain. 2004;111:77–83. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2004.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rollman BL, Belnap BH, Mazumdar S, et al. A randomized trial to improve the quality of treatment for panic and generalized anxiety disorders in primary care. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2005;62:1332–1341. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.62.12.1332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rollman BL, Herbeck Belnap B, Reynolds CF, Schulberg HC, Shear MK. A contemporary protocol to assist primary care physicians in the treatment of panic and generalized anxiety disorders. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2003;25:74–82. doi: 10.1016/s0163-8343(03)00004-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ware J, Jr, Kosinski M, Keller SD. A 12-Item Short-Form Health Survey: construction of scales and preliminary tests of reliability and validity. Med Care. 1996;34:220–233. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199603000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Blyth FM, March LM, Brnabic AJ, Jorm LR, Williamson M, Cousins MJ. Chronic pain in Australia: a prevalence study. Pain. 2001;89:127–134. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3959(00)00355-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Scudds RJ, Ostbye T. Pain and pain-related interference with function in older Canadians: the Canadian Study of Health and Aging. Disabil Rehabil. 2001;23:654–664. doi: 10.1080/09638280110043942. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Thomas E, Peat G, Harris L, Wilkie R, Croft PR. The prevalence of pain and pain interference in a general population of older adults: cross-sectional findings from the North Staffordshire Osteoarthritis Project (NorStOP) Pain. 2004;110:361–368. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2004.04.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Shear MK, Vander Bilt J, Rucci P, et al. Reliability and validity of a structured interview guide for the Hamilton Anxiety Rating Scale (SIGH-A) Depress Anxiety. 2001;13:166–178. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Shear MK, Brown TA, Barlow DH, et al. Multicenter collaborative panic disorder severity scale. Am J Psychiatry. 1997;154:1571–1575. doi: 10.1176/ajp.154.11.1571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Barlow DH, Gorman JM, Shear MK, Woods SW. Cognitive-behavioral therapy, imipramine, or their combination for panic disorder: a randomized controlled trial. J Am Med Assoc. 2000;283:2529–2536. doi: 10.1001/jama.283.19.2529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Roy-Byrne PP, Katon W, Cowley DS, Russo J. A randomized effectiveness trial of collaborative care for patients with panic disorder in primary care. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2001;58:869–876. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.58.9.869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tarlov AR, Ware JE, Jr, Greenfield S, et al. The Medical Outcomes Study. An application of methods for monitoring the results of medical care. Jama. 1989;262:925–930. doi: 10.1001/jama.262.7.925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Potts MK, Daniels M, Burnam MA, Wells KB. A structured interview version of the Hamilton Depression Rating Scale: evidence of reliability and versatility of administration. J Psychiatr Res. 1990;24:335–350. doi: 10.1016/0022-3956(90)90005-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lambert D. Zero-inflated Poisson regression, with an application to defects in manufacturing. Technometrics. 1992;34:1–14. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Vlaeyen JW, Linton SJ. Fear-avoidance and its consequences in chronic musculoskeletal pain: a state of the art. Pain. 2000;85:317–332. doi: 10.1016/S0304-3959(99)00242-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Picavet HS, Vlaeyen JW, Schouten JS. Pain catastrophizing and kinesiophobia: predictors of chronic low back pain. Am J Epidemiol. 2002;156:1028–1034. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwf136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.McCracken LM, Gross RT. Does anxiety affect coping with chronic pain? Clin J Pain. 1993;9:253–259. doi: 10.1097/00002508-199312000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.McCracken LM, Gross RT, Sorg PJ, Edmands TA. Prediction of pain in patients with chronic low back pain: effects of inaccurate prediction and pain-related anxiety. Behav Res Ther. 1993;31:647–652. doi: 10.1016/0005-7967(93)90117-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Grachev ID, Fredrickson BE, Apkarian AV. Brain chemistry reflects dual states of pain and anxiety in chronic low back pain. J Neural Transm. 2002;109:1309–1334. doi: 10.1007/s00702-002-0722-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Russell JM, Weisberg R, Fava M, Hartford JT, Erickson JS, D’Souza DN. Efficacy of duloxetine in the treatment of generalized anxiety disorder in patients with clinically significant pain symptoms. Depress Anxiety. 2008;25:E1–E11. doi: 10.1002/da.20337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Stein MB, Sherbourne CD, Craske MG, et al. Quality of care for primary care patients with anxiety disorders. Am J Psychiatry. 2004;161:2230–2237. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.161.12.2230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Auret K, Schug SA. Underutilisation of opioids in elderly patients with chronic pain: approaches to correcting the problem. Drugs Aging. 2005;22:641–654. doi: 10.2165/00002512-200522080-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Melzack R. The McGill Pain Questionnaire: major properties and scoring methods. Pain. 1975;1:277–299. doi: 10.1016/0304-3959(75)90044-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Shear K, Belnap BH, Mazumdar S, Houck P, Rollman BL. Generalized Anxiety Disorder Severity Scale (GADSS): a preliminary validation study. Depress Anxiety. 2006;23:77–82. doi: 10.1002/da.20149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]