Abstract

Neuronal calcium sensor (NCS) proteins regulate signal transduction and are highly conserved from yeast to humans. NCS homolog in fission yeast (Ncs1p) is essential for cell growth under extreme Ca2+ conditions. Ncs1p expression increases ∼100-fold when fission yeast grows in high extracellular Ca2+ (>0.1 m). Here, we show that Ca2+-induced expression of Ncs1p is controlled at the level of transcription. Transcriptional reporter assays show that ncs1 promoter activity increased 30-fold when extracellular Ca2+ was raised to 0.1 m and was highly Ca2+-specific. Ca2+-dependent transcription of ncs1 is abolished by the calcineurin inhibitor (FK506) and by knocking out the calcineurin target, prz1. Thus, Ca2+-induced expression of Ncs1p is linked to the calcineurin/prz1 stress response. The Ca2+-responsive ncs1 promoter region consists of 130 nucleotides directly upstream from the start codon and contains tandem repeats of the sequence, 5′-caact-3′, that binds to Prz1p. The Ca2+-sensitive ncs1Δ phenotype is rescued by a yam8 null mutation, suggesting a possible interaction between Ncs1p and the Ca2+ channel, Yam8p. Ca2+ uptake and Ncs1p binding to yeast membranes are both decreased in yam8Δ, suggesting Ca2+-induced binding of Ncs1p to Yam8p results in channel closure. We propose that Ncs1p promotes Ca2+ tolerance in fission yeast, in part by cytosolic Ca2+ buffering and perhaps by negatively regulating the Yam8p Ca2+ channel.

Keywords: Calcium, Calcineurin, Calcium-binding Proteins, Calmodulin, Yeast Transcription, EF-hand, NCS-1, Calcineurin, Calmodulin, Fission Yeast

Introduction

Calcium ion (Ca2+) regulates signaling processes in the fission yeast, Schizosaccharomyces pombe (reviewed in Refs. 1–3), as it does in mammalian cells (reviewed in Ref. 4). Fission yeast contains ion channels (5, 6) and transporters (7–9) homologous to those involved in regulating Ca2+ entry and signal transduction in excitable cells. Thus, stimulation of yeast cells by pheromones or other extracellular stimuli lead to an increase in intracellular Ca2+ levels (10, 11) sensed by Ca2+-binding proteins belonging to the EF-hand superfamily (12). In S. pombe, a total of 23 genes specifies EF-hand-containing Ca2+-binding proteins, including cam1 (calmodulin) (13), cnb1 (calcineurin B) (14), and the recently characterized ncs1 gene (Ncs1p) (15), belonging to the neuronal calcium sensor (NCS)2 family (16) expressed mostly in the central nervous system (17, 18).

The primary sequence of S. pombe Ncs1p is >50% identical to neuronal homologs of the NCS branch of the EF-hand superfamily (19, 20). Recoverin, the most intensively studied NCS protein, serves as a Ca2+ sensor in retinal rod and cone cells where it controls the desensitization of rhodopsin (21–24). The NCS family also includes neuronal Ca2+ sensors such as neurocalcin (25), hippocalcin (26), and frequenin (27), as well as the budding yeast homolog, Frq1 (28). All members of the NCS family have around 200 amino acid residues, contain N-terminal myristoylation, and possess four EF-hands.

Three-dimensional structures are now known for many NCS proteins, including recoverin (29, 30), frequenin (31), Frq1 (32), neurocalcin (33), and guanylate cyclase activator proteins (34, 35). The Ca2+-bound forms of these proteins all share a common fold with four EF-hands arranged in a tandem array, with an exposed N-terminal myristoyl group. Binding of Ca2+ to recoverin leads to extrusion of its myristoyl group such that many hydrophobic residues become exposed for target recognition (30, 36). The Ca2+-induced exposure of the myristoyl group, termed the Ca2+-myristoyl switch, enables recoverin to bind to membrane targets only at high Ca2+ levels (37, 38).

NCS proteins interact with and regulate many different physiological targets. Recoverin binds specifically and regulates rhodopsin kinase (23), whereas the guanylate cyclase activator proteins specifically regulate retinal guanylate cyclases (39, 40). NCS-1 and yeast Frq1 activate phosphatidylinositol 4-kinase important for secretion from the Golgi (28). Hippocalcin and VILIP proteins regulate guanylate cyclase and nicotinamide acetylcholine receptors implicated in synaptic plasticity (41). KChIPs (42), hippocalcin (43), and NCS-1 (44) all bind and regulate various ion channels and thus serve as Ca2+ sensors that control membrane excitability. The mechanism of target regulation in each case is not understood, and it remains unclear how the structurally similar NCS proteins are able to specifically bind and regulate so many different target proteins.

Yeast genetics is a powerful tool for dissecting NCS protein interactions in signaling pathways. Indeed, genetics studies performed on the budding yeast, Saccharomyces cerevisiae showed that FRQ1 is an essential yeast gene (28). The lethality of the Frq1 knockout strain was rescued upon overexpressing the PIK1 gene, suggesting an interaction between Frq1 and Pik1 (phosphatidylinositol 4-kinase). Additional studies have shown that Frq1 interacts structurally with Pik1, and this Ca2+-induced interaction is essential for the activation of lipid kinase activity in budding yeast (32, 45, 46).

Similar knockout studies were also performed on fission yeast and revealed two additional NCS targets (15). First, S. pombe ncs1, unlike FRQ1, is not an essential yeast gene. Instead, the ncs1 deletion strain (ncs1Δ) exhibited nutrition-insensitive sporulation, suggesting that Ncs1p may regulate desensitization of the glucose receptor. Second, the ncs1Δ fission yeast is unable to grow in the presence of high extracellular Ca2+ concentrations, demonstrating that Ncs1p helps confer Ca2+ tolerance. High affinity Ca2+ binding to Ncs1p and its Ca2+-induced expression are both essential for protecting fission yeast from extreme Ca2+ conditions. The Ca2+ intolerance of the ncs1Δ phenotype is not complemented by overexpressing FRQ1 or mammalian recoverin, indicating that Ncs1p is more than just a Ca2+ buffer and performs a unique sensory function in fission yeast.

In this study, we further characterized the molecular mechanism of Ca2+ tolerance conferred by Ncs1p in fission yeast. Previously, we showed that exposure of yeast cells to high extracellular Ca2+ levels causes the Ncs1p expression level to increase nearly 100-fold (15). Our current studies demonstrate that Ca2+-induced expression of Ncs1p in fission yeast is controlled at the transcriptional level. The Ca2+-sensitive ncs1 promoter region is localized to the first 130bp upstream from the start codon and has been named, mec1 (more expression with calcium). The Ca2+-induced transcription of ncs1 is regulated by calcineurin and therefore linked to an important stress response (47, 48). A useful application of this work was our development of an expression vector harboring the ncs1 promoter (mec1) that is capable of providing rapid, inducible expression of recombinant genes in fission yeast.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Strains and Growth Conditions

S. pombe strains used in this study are listed in Table 1. Standard culture media and genetic manipulation techniques were used (15, 49). For vegetative growth of S. pombe, rich medium (YES) or synthetic minimum medium (EMM) were used with addition of nutritional supplements as needed (49).

TABLE 1.

S. pombe strains used in this study

| Strainab | Relevant genotype | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| NHP058 | h+his3-D1 ade6-M216 leu1–32 ura4-D18 | Hamasaki-Katagiri et al. (15) |

| NHP059 | h+his3-D1 ade6-M216 leu1–32 ura4-D18 ncs1Δ::his3 | Hamasaki-Katagiri et al. (15) |

| NHP083 | h+his3-D1 ade6-M216 leu1–32 ura4-D18 prz1::LEU2 | This study |

| HC3 | h−ade6-M210 leu1–32 ura4-D18 ehs1/yam8::ura4 | Carnero et al. (5) |

| NHP085 | h+his3-D1 ade6-M210 leu1–32 ura4-D18 ehs1/yam8::ura4 | This study |

| NHP094 | h−his3-D1 ade6-M210 leu1–32 ura4-D18 ehs1/yam8::ura4 ncs1Δ::his3 | This study |

| KP2758 | h−leu1–32 ura4-D18 yam8::ura4+ | Furune et al. (73) |

a S. pombe strain HC3 was a kind gift from Dr. Sanchez.

b S. pombe strain KP2758 was a kind gift from Dr. Kuno.

Prz1-insertion mutant NHP083 was created by one-step gene disruption with wild-type NHP058. Cloning of prz1 open reading frame and construction of prz1::LEU2 fragment was performed according to Hirayama et al. (48) using LEU2 gene as a marker instead of ura4 gene. The deletion allele (prz1::LEU2) was confirmed by Southern blotting analysis.

Ehs1/yam8 mutant strain HC3 was a kind gift from Dr. Y. Sanchez (Universidad de Salamanca, Spain) (5). The yam8 deletion mutant (strain KP2758) was a kind gift from Dr. Takayoshi Kuno (Kobe University, Kobe, Japan) (47). Ehs1/yam8 mutant strain with his3 mutation, NHP085, and a double mutant NHP094 was derived from the cross of HC3 and NHP059.

For the calcium sensitivity assay, calcium chloride was added to YES agar media at a final concentration of 0.1 m before autoclaving (calcium plate). FK506 (A. G. Scientific, Inc.) was stored in 90% ethanol-10% Tween 20 at a concentration of 20 mg/ml at −70 °C and added to the agar plate right before the experiment. The mutant strain, bearing a plasmid based on S. pombe expression vector pREP4X (ura4+), was grown on EMM-U to maintain plasmids to exponential phase before being streaked onto YES-containing calcium.

Plasmids

The mec803 construct, a 803-bp fragment consisting of −803 to −1 nucleotides upstream of ncs1 open reading frame, was obtained by PCR cloning using genomic DNA from wild-type strain NHP058 as a template and 5′-AACTGCAGAAATGTTAAACATAATTACC-3′ and 5′-CTCGAGGAGCTCGCGGCCGCTCTAGAGGGCCCGGTACCCTTGAAGACAAGTTAATC-3′ as upstream and downstream primers, respectively. S. pombe expression plasmid pREP42-mec803-GFP (ura4+) was constructed by replacement of nmt1 promoter in pREP42EGFP-C, a gift from Dr. Ian M. Hagan (University of Manchester, Manchester, UK), with an mec803 fragment using PstI and XhoI restriction sites.

Plasmid pREP4X-mec803-luxAB was constructed by replacement of the nmt1 promoter in pREP4X with mec803 fragment at PstI/XhoI restriction sites and insertion of the bacterial luciferase luxAB fragment at XhoI/XmaI restriction sites. Bacterial luciferase luxAB gene, derived from Vibrio harveyi luxA and luxB, was PCR-cloned from pDCM58, a kind gift from Dr. Daniel C. Masison (National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD) (50, 51).

Shorter versions of ncs1 promoter fragment mec666, mec424, mec313, and mec206 were cloned in the same way as mec803. The promoter fragments mec183, mec155, mec130, mec102, mec78, and mec51 were PCR-cloned from pREP4X-mec803-luxAB together with luxAB gene.

Plasmid pREP4X-mec424-ncs1 was constructed by replacing the luxAB gene fragment in pREP4X-mec424-luxAB with the ncs1 gene (15). Plasmids pREP4X-mec130-ncs1 and pREP4X-mec102-ncs1 were constructed in the same way as pREP4X-mec424-ncs1. The Prz1 gene fragment obtained during construction of prz1::LEU2 was introduced into XhoI/XmaI restriction sites of pREP4X to create pREP4X-prz1. All the sequences of cloned nucleotides were confirmed.

Promoter Assays

For quantitative assay using bacterial luciferase (luxAB) reporter gene, yeast cells grown in synthetic media were diluted to A600 of 0.5 in synthetic media containing calcium chloride, other salts, and reagents and/or FK506, as indicated, at the start of the incubation. After indicated periods of incubation at 30 °C, 5 μl of n-decanal, a substrate reagent, was added to 100 μl of culture, and the fluorescence of the mixture was measured immediately at room temperature. Each experiment was performed as duplicate and average reading per cell density (A600) of each culture was given. These values were compared with that of control experiment (no additional reagent), and relative activation of ncs1 promoter levels were shown as “relative promoter activity.” For qualitative assay using GFP reporter gene, yeast cells were grown similarly and observed under fluorescence microscope (Olympus BX51 equipped with a charge-coupled device camera, SPOT-RT Slider, Diagnostic Instruments).

Western Blot Analysis

Western blot analysis was performed as described before (15). Briefly, the cells from the cultures of the same optical densities were lysed in EB buffer (15 mm KCl, 10 mm HEPES-KOH, pH 7.8, 3 mm dithiothreitol, 1 mm phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride), and the lysate samples were subjected to SDS-PAGE (15% acrylamide) followed by Western blot analysis with anti-GFP antibody (mouse polyclonal antibody, Clontech).

Membrane Binding Assay

Binding of recombinant, unmyristoylated Ncs1p to Yam8p was studied by using a pulldown assay using S. pombe membranes. Purified recombinant Ncs1p was prepared as described previously (15). The plasma membrane fraction containing Yam8p was isolated from a 1-liter fission yeast culture grown in YES medium by first disrupting cells using glass beads to generate a cell-free suspension followed by ultracentrifugation (18,000 × g for 30 min) to obtain a final membrane pellet (15). The membrane pellet was washed twice with an equal volume of EGTA buffer (1 mm EGTA, 0.1 m NaCl, 10 mm Tris at pH 7.5) to remove any endogenous myristoylated Ncs1p. The Ncs1p-free membrane pellet was then suspended in an equal volume of lysis EB buffer and could be stored overnight. An aliquot of the stock membrane suspension (100 μl) was treated with an equal volume of unmyristoylated Ncs1p stock solution (2 mg/ml) in either the Ca2+-free (1 mm EGTA) or Ca2+-bound (1 mm CaCl2) state and incubated for 30 min at 4 °C. The Ncs1p-treated membranes were centrifuged (18,000 × g for 30 min) to spin down the membrane pellet. The pelleted membranes were washed once to remove unbound Ncs1p and then subjected to SDS-PAGE (15% acrylamide) followed by Western blot analysis with anti-ncs1 antibody (provided by the UC Davis Genome Center).

Fluorescent EMSA

Synthetic oligonucleotides (purchased from ACGT Corp.) representing nucleotides −130 to −101 in the ncs1 promoter were 5′-labeled using the fluorescent dye, Cy5 (Amersham Biosciences). This 30-bp nucleotide sequence was 5′-AATTTACCCTGCGCCTCCCCAACTTCAACT-3′. For cold-chase competition experiments (52), unlabeled double-stranded oligonucleotides of wild-type sequence (above), randomized sequence (5′-ATGCTTGCATGACTCAGACAGTACGACTG-3′), and mutated sequence (5′-AATTTACCCTGCGCCTCCCAGGACTCAACT-3′) were used as unlabeled competitors. Complementary strands were denatured at 95 °C for 10 min and annealed by slowly cooling to room temperature in the presence of 10 mm HEPES (pH 7.5), 0.1 m NaCl, 5 mm MgCl2, and 0.1 mm EDTA. Formation of double-stranded DNA was checked on a 20% non-denaturing polyacrylamide/0.25 × TBE/1% glycerol gel prior to binding.

Recombinant Prz1p with a 6-His tag was expressed by pET151-prz1p in Escherichia coli strain BL21(DE3) and purified using established procedures (45). Purified protein samples were exchanged into 10 mm HEPES (pH 7.5), 0.1 m NaCl, and 5 mm Mg2+ and concentrated by Centricon 10 (Millipore) at 4 °C. Prz1p stock protein (50 μm) was then incubated with 5 nm Cy5-labeled duplex DNA for 1 h at room temperature in 10 mm HEPES, pH 7.5, 5 mm MgCl2, 0.1 mm EDTA, 2 mm dithiothreitol, and 1 nm (0.05 unit per ml) of poly(dI-dC) (Amersham Biosciences). Protein-DNA complexes were resolved on 5% non-denaturing polyacrylamide/0.25 × TBE/1% glycerol gels at 200 V for 30 min in 0.25 × TBE and 0.5 mm MgCl2 running buffer. Wet fluorescent gels were scanned using the red fluorescence mode of a Storm 860 system (Molecular Dynamics) with a voltage setting of 1000 V and a scanning resolution of 200 μm.

RESULTS

Ca2+-induced Transcription of Ncs1

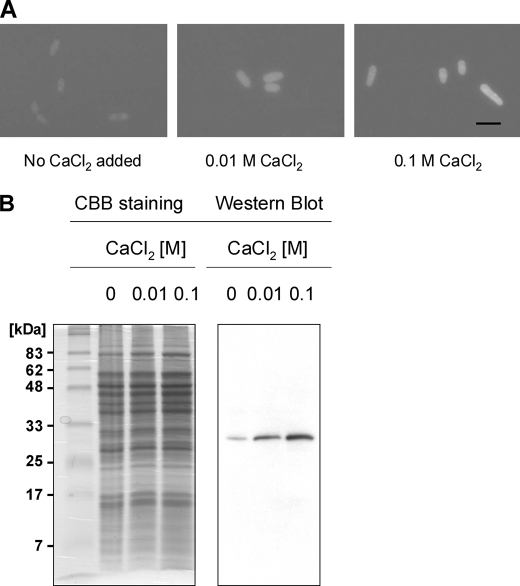

In our earlier study, we discovered a striking Ca2+-sensitive phenotype in the ncs1 deletion mutant (ncs1Δ) of fission yeast (15). Ca2+-induced expression of Ncs1p protein in fission yeast was found to be necessary to protect the cell from high levels of extracellular Ca2+ (0.1 m in agar plate). The cellular level of endogenous Ncs1p was up-regulated nearly 100-fold when the extracellular Ca2+ concentration increased to 0.01 m. In the current study, we investigated whether the Ca2+-induced expression of Ncs1p is controlled at the transcriptional level. To test this possibility, a segment of genomic DNA that encompasses the ncs1 promoter region (803 bp upstream from the start codon) was introduced upstream of the GFP gene in a transcriptional reporter vector for fission yeast. The transcription and hence expression of GFP in these cells (monitored by fluorescence excited at 488 nm) increased dramatically as calcium was added to the extracellular media (Fig. 1A). The Ca2+-induced expression of GFP was also confirmed by Western blotting analysis using anti-GFP antibody (Fig. 1B). These results demonstrate that the ncs1 promoter is capable of producing a dramatic increase in the transcription of GFP when a final Ca2+ concentration ranging from 0.01 to 0.1 m was added to the extracellular medium. Thus, the ncs1 promoter is Ca2+-responsive, indicating that Ca2+-induced expression of Ncs1p in fission yeast must be the result of up-regulated transcription.

FIGURE 1.

Ncs1 promoter activity regulated by calcium. A, the S. pombe wild-type strain that bears pREP42-mec803-EGFP was grown in EMM-U media containing 0, 0.01, or 0.1 m calcium chloride for 16 h and observed by fluorescence microscopy (×400). The black bar indicates 10 μm. B, the same cells used in A were lysed, and the cell lysates were analyzed by Western blot analysis using anti-GFP antibody (right panel). The left panel shows an equivalent gel stained by Coomassie Brilliant Blue to show that each lane contained the same level of protein.

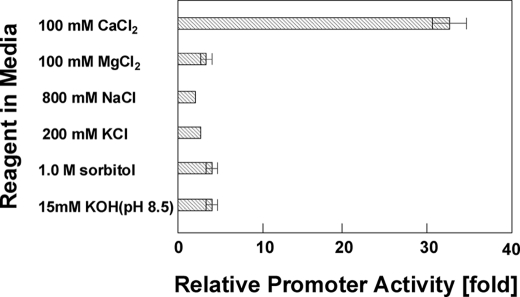

Ca2+-dependent transcription in yeast occurs in stress-response pathways known to be activated by osmotic shock, high pH, and salts (53). The activity of the ncs1 promoter was, therefore, tested against various salts and other stresses using bacterial luciferase as a quantitative reporter gene (see “Experimental Procedures”). The addition of divalent cations (Mg2+ or Mn2+), monovalent cations, osmotic reagent, and/or high pH (media pH of 8.5 before growth) did not cause a change in the observed luciferase reporter activity (Fig. 2). Luciferase activity from the cells without stress treatment was the same level in all cases. By contrast, the luciferase reporter activity increased >30-fold when the extracellular calcium concentration was raised to 0.1 m, similar to that observed above using the GFP reporter assay. As a consequence of its Ca2+-specific promoter activity, we named the ncs1 promoter, “more expression with calcium 1” (mec1). The Ca2+-induced up-regulation of ncs1 promoter activity occurs relatively quickly as evidenced by a 5-fold increase after only 30 min of induction (data not shown). The promoter activity increased >30-fold within 2 h and remained at that level after an overnight incubation. The Ca2+-induced ncs1 promoter activity kept increasing monotonically while the extracellular media Ca2+ concentration was raised from 0.01 to 0.3 m and finally leveled off at 1.0 m, which is the upper limit for allowing growth of wild type fission yeast in liquid media.

FIGURE 2.

Calcium specific up-regulation of ncs1 promoter. Reporter activities, using wild-type cells bearing a plasmid pREP-mec803-luxAB (bacterial luciferase) grown in minimum media, were measured 6 h after the cells were treated with various reagents. Promoter activity was shown as a ratio of the luminometer readings of the cells with reagent versus without reagent (see “Experimental Procedures”).

What transcription factor proteins in fission yeast are involved in producing the Ca2+-induced transcription of ncs1? The simplest possibility would be to have the protein product (Ncs1p) interact directly with its own promoter in a Ca2+-dependent fashion and thus provide a simple feedback. Indeed, the NCS protein DREAM is a transcription factor that binds to specific DNA promoter sequences and serves as a transcriptional repressor for pain modulation (54, 55). To test whether Ncs1p binds to the ncs1 promoter, electrophoretic mobility shift assays (EMSAs) were performed below but were unable to detect any DNA binding by Ncs1p. In addition, the transcriptional reporter assays described above were performed using ncs1Δ (that lacked Ncs1p) and compared with those above for wild type. The ncs1Δ mutant showed ∼3-fold higher Ca2+-induced ncs1 promoter activity compared with that of wild type (Table 2). In the absence of Ca2+, the ncs1 promoter activities of wild type and ncs1Δ both were similar. Together, these results indicate that Ncs1p is not needed for Ca2+-induced ncs1 promoter activity, and therefore Ncs1p is not a transcription factor in this case and does not mediate a direct feedback mechanism.

TABLE 2.

Activity of ncs1 promoter monitored by luciferase reporter assay

| Condition or media additive | Relative promoter activity |

|---|---|

| WT (no added Ca2+)a | 1 |

| WT (no added Ca2+)a + FK506 | 1.9 |

| WT (0.1 m CaCl2)a | 35.9 |

| WT (0.1 m CaCl2)a + FK506 | 3.2 |

| WT (no added Ca2+)b | 1 |

| WT (0.1 m CaCl2)b | 7.9 |

| ncs1Δ (no added Ca2+)b | 1 |

| ncs1Δ (0.1 m CaCl2)b | 27 |

| prz1− (no added Ca2+)b | 1 |

| prz1− (0.1 m CaCl2)b | 1.8 |

a The ncs1 promoter activity was measured 18 h after treating cells with 0.1 m CaCl2 and/or 1 μg/ml FK506 using bacterial luciferase reporter assay as described in Fig. 2.

b The ncs1 promoter activity was measured 4 h after treating cells with 0.1 m CaCl2.

Transcription of ncs1 Controlled by Calcineurin and prz1

A possible mechanism for Ca2+-induced ncs1 promoter activity involves the well characterized “stress response” pathway via the CaM-dependent protein phosphatase, calcineurin (14, 56–58). Various stress signals such as high salt, high pH, elevated temperature, and hypertonic shock as well as pheromone stimulation all cause an increase in cytosolic Ca2+. Elevation of intracellular Ca2+ activates calcineurin that in turn activates transcription factor proteins by dephosphorylation. A target of calcineurin in budding yeast is the protein TCN1/CRZ1 that triggers the transcription of a group of genes containing the calcineurin-dependent response element (CDRE) motif (53, 59). A homolog of TCN1/CRZ1 in fission yeast (prz1) is also dephosphorylated by calcineurin and translocates to nuclei in response to Ca2+ signaling (48). The prz1 deletion mutant has the same calcium-sensitive phenotype (48) as ncs1Δ, suggesting a possible interaction between ncs1 and prz1.

Does Ca2+-induced activation of the ncs1 promoter involve the calcineurin-prz1 pathway? To test this possibility, we first used the calcineurin inhibitor, FK506, to determine whether inhibition of calcineurin has any effect on the Ca2+-dependent ncs1 promoter activity. The addition of 1 μg/ml FK506 to the cell media under normal basal conditions (i.e. with no added Ca2+) caused morphological effects reported previously (48) but did not affect the basal ncs1 promoter activity. The addition of FK506 significantly prevented Ca2+-induced up-regulation of ncs1 promoter activity when the extracellular Ca2+ concentration was raised to 0.1 m (Table 2). These results indicate that enzymatic activity of calcineurin is necessary for promoting Ca2+-induced transcription of ncs1.

The next question was to examine whether the calcineurin target (Prz1p) is required for Ca2+-induced activation of the ncs1 promoter. The ncs1 promoter activity was measured in a prz1− mutant (lacking expression of Prz1p) to see if Ca2+-induced transcription of ncs1 is controlled by the transcription factor protein, Prz1p. The ncs1 promoter activity from prz1− cells (monitored by the luciferase reporter assay) increased only a small amount (<1.9-fold) when extracellular Ca2+ concentration was raised to 0.1 m for 6 h (Table 2). Thus, prz1− lacks the robust Ca2+-induced activation of ncs1 promoter seen in wild type. The prz1 deletion mutant was then supplemented with either pREP4X-prz1 or pREP4X-prz1-SRR (constitutively active form (48)) to introduce expression of recombinant Prz1p and to directly demonstrate whether Prz1p is necessary to promote Ca2+-induced activation of ncs1 promoter. When either pREP4X-prz1 or pREP4X-prz1-SRR was introduced into prz1−, these cells initially grew slowly in the presence of 10 μm of thiamine (which allows moderate expression) and tended to aggregate. However, after conditioning the cells to grow in calcium-free media, these cells showed more than 8-fold higher ncs1 promoter activity compared with a negative control (cells containing reporter constructs bearing empty vector). These results show that expression of the transcription factor, Prz1p, is required for Ca2+-induced activation of the ncs1 promoter.

Finally, we wanted to investigate whether Prz1p is acting solely on Ncs1p in the ncs1Δ phenotype or whether Prz1p also up-regulates other genes that contribute to Ca2+ tolerance. To address this issue, we prepared a prz1− mutant that overexpresses Ncs1p (pREP4X-ncs1) and ncs1Δ that overexpresses Prz1p (pREP4X-prz1). If overexpression of Ncs1p complements the Ca2+-sensitive prz1− phenotype, then this would suggest that Prz1p up-regulates Ncs1p alone to confer Ca2+ tolerance. Interestingly, both strains testing for complementation grew very slowly even without Ca2+, and both were not viable in the presence of high extracellular Ca2+. The lack of any complementation by Ncs1p in prz1− suggests that up-regulation of ncs1 alone is not sufficient for Ca2+ tolerance. Indeed, Prz1p also controls expression of Ca2+ pump genes, pmr1 and pmc1 (47, 48), whose Ca2+-induced expression must also be necessary to enable Ca2+ tolerance.

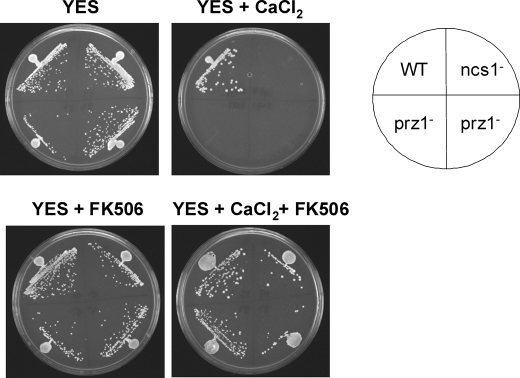

Calcineurin Regulates Multiple Targets

Our studies above on prz1− mutant and calcineurin inhibitor (FK506) clearly demonstrate that the calcineurin/prz1 pathway controls Ca2+-induced transcription of ncs1. This would predict that FK506 should prevent Ca2+-induced expression of Ncs1p and therefore disable wild-type cells from growing at high Ca2+ levels like those seen with ncs1Δ. Surprisingly, the wild-type strain grew equally well on calcium plates in the presence or absence of FK506 (Fig. 3), indicating that FK506 had almost no effect on the Ca2+ tolerance of wild type. Even more surprising was the observation that FK506 added to ncs1Δ strain appears to rescue the Ca2+-sensitive ncs1Δ phenotype (Fig. 3). FK506 treatment also rescued the Ca2+-sensitive phenotype of prz1− (Fig. 3). The fact that a calcineurin inhibitor restores Ca2+ tolerance in both ncs1Δ and prz1− suggests that calcineurin must regulate other targets independent of Prz1p and Ncs1p (47). Calcineurin can directly regulate protein targets by catalyzing the removal of phosphate groups. Indeed, calcineurin in budding yeast directly inhibits the Ca2+ exchanger, Vcx1, by promoting its dephosphorylation (60). A similar calcineurin-dependent inhibition of a Ca2+ exchanger is also likely in fission yeast because Saccharomyces cerevisiae Vcx1 is >90% identical in sequence to its fission yeast homolog. Thus, calcineurin-dependent inhibition of a Vcx1 homolog in fission yeast could explain the effects of FK506 in Fig. 3. FK506 promotes calcium tolerance in both ncs1Δ and prz1−, because it removes inhibition of a vacuolar Ca2+ exchanger (Vcx1). The activation of Vcx1 by FK506 provides increased capacity to sequester elevated Ca2+ and thus maintain viable cytosolic Ca2+ levels in the ncs1Δ and prz1− mutants grown in high Ca2+ (see Fig. 3) that otherwise is not possible without FK506.

FIGURE 3.

Both ncs1Δ and prz1− mutants regain calcium tolerance in the presence of FK506. Ncs1D and prz1− mutant cells (two independent isolates for prz1−) were streaked on rich media agar plates containing 0.1 m calcium chloride and/or 0.5 μg/ml FK506.

Ncs1p Targets Yam8p Ca2+ Channel

What is the physiological target of Ncs1p in fission yeast? A likely target protein that affects Ca2+ tolerance is a Ca2+ channel, because it can readily restrict Ca2+ influx. In S. pombe, there is currently only one characterized Ca2+ channel, coded by the gene, ehs1/yam8 (hereafter called, yam8). The yam8 gene is a homolog of the high affinity Ca2+ channel (MID1) in S. cerevisiae that encodes a stretch-activated calcium channel on the plasma membrane (5, 6). To examine the role of yam8 in the calcium-sensitive ncs1Δ phenotype, a deletion mutant of yam8 was crossed with the ncs1Δ strain. The ncs1Δ/yam8Δ mutant grows equally well in the presence or absence of high Ca2+, and therefore the yam8 deletion rescues Ca2+ tolerance (Table 3). This demonstrates that reduced Ca2+ influx from the yam8 deletion is sufficient to protect the ncs1Δ cells from high extracellular Ca2+, suggesting that yam8 might be a target of either ncs1 or calcineurin. An intriguing hypothesis is that Ca2+-bound Ncs1p might physically interact with Yam8p and promote Ca2+-induced channel closure similar to the Ca2+-induced closure of voltage-gated Ca2+ channels mediated by CaM (61, 62) and NCS-1 (44). Alternatively, Yam8p channel activity might also be controlled by protein dephosphorylation catalyzed by calcineurin (63).

TABLE 3.

Loss of Yam8p Ca2+ channel rescues calcium tolerance of ncs1Δ mutant

Wild-type, ncs1Δ, yam8Δ, or double mutant cells were streaked onto rich medium with or without 0.1 m CaCl2.

| Genotype | Growth |

|

|---|---|---|

| −Ca2+ | +Ca2+ | |

| ncs1+/yam8+ | + | + |

| ncs1Δ/yam8+ | + | − |

| ncs1+/yam8Δ | + | + |

| ncs1Δ/yam8Δ | + | + |

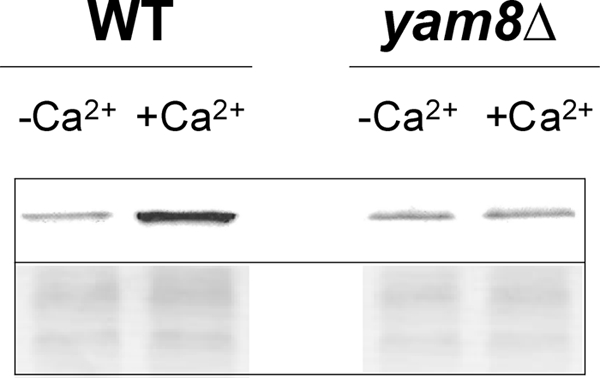

To examine whether Ncs1p directly binds to Yam8p, we performed a series of membrane binding pulldown assays (Fig. 4). Because the ncs1G2A mutant is able to rescue calcium tolerance in ncs1Δ (15), this implies that unmyristoylated Ncs1p is physiologically active in this phenotype. Also, removal of the myristoyl group is necessary to eliminate nonspecific membrane binding by virtue of the Ca2+-myristoyl switch (15, 37). A purified sample of recombinant unmyristoylated Ncs1p protein was added to a plasma membrane fraction isolated from wild-type or yam8Δ fission yeast cells and assayed for Ca2+-dependent membrane binding in each case. The membrane fraction (pellet) was first washed with 1 mm EGTA to remove endogenous Ca2+-free, myristoylated Ncs1p. The lack of endogenous Ncs1p in the membrane fraction was verified using SDS-PAGE and Western blot analysis. The Ca2+-free (and Ncs1p free) membranes were then suspended and incubated with recombinant unmyristoylated Ncs1p both in the presence and absence of saturating Ca2+. The Ncs1p-treated membranes were washed once with buffer. The pelleted membranes were then subjected to SDS-PAGE and Western blot analysis to look for the binding of Ncs1p. In the absence of Ca2+, a faint band appeared at ∼22 kDa on a Western blot (Fig. 4), representing weak binding of Ncs1p to membranes and/or background signal. The intensity of this faint band increased ∼3-fold when the pulldown experiment was performed in the presence of saturating Ca2+ (1 mm Ca2+). Clearly, the addition of Ca2+ enhances the binding of unmyristoylated Ncs1p to yeast membranes that we suggest might represent binding of Ca2+-bound Ncs1p to Yam8p in the membranes. To further test this possibility, the same pulldown assay was performed on membranes isolated from yam8Δ cells that lack expression of Yam8p. In this case, the Ca2+-induced binding of Ncs1p to membranes is somewhat reduced (Fig. 4), consistent with a loss of Ca2+-induced binding to Yam8p. These results suggest Ca2+-induced binding of Ncs1p to Yam8p that might promote channel closure, analogous to Ca2+-induced inhibition of voltage-gated Ca2+ channels by Ca2+-bound CaM (61, 62).

FIGURE 4.

Membrane-binding pulldown assay. Plasma membrane fractions from S. pombe wild-type and yam8 deletion mutant (KP2758) cells were treated with recombinant, unmyristoylated Ncs1p in the presence (right) and absence (left) of saturating Ca2+. Upper panel, Ncs1p bound to S. pombe membranes probed by Western blot analysis. Bottom panel, SDS-PAGE of membrane fractions visualized by Coomassie Brilliant Blue staining.

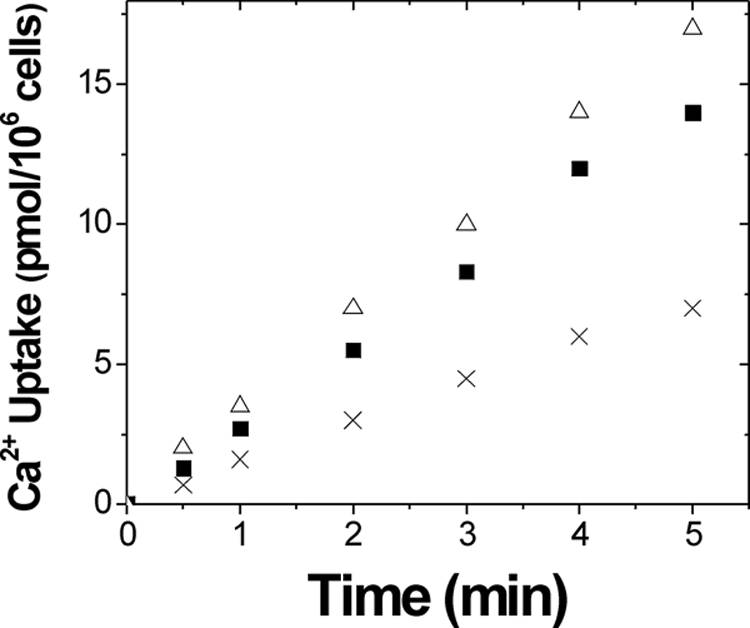

To test whether Ca2+-induced interaction of Yam8p with Ncs1p results in channel closure, we compared Ca2+ uptake measured from yeast strains: wild type, ncs1Δ, and yam8Δ (Fig. 5). Experiments measuring the uptake of radioactive Ca2+ (45Ca) by fission yeast were performed as described previously (6, 64). The ncs1Δ strain exhibited higher uptake of 45Ca compared with that of wild type, whereas 45Ca uptake by yam8Δ was markedly lower. These results provide evidence that Ncs1p binding to Yam8p promotes Ca2+-induced channel closure in fission yeast.

FIGURE 5.

Calcium uptake activity in fission yeast. Calcium 45 uptake by yeast cells was measured at different time points after the addition of 1 μm 45Ca2+ to the cell culture under the same conditions as described in a previous study (64) for wild type (solid squares), ncs1Δ (open triangles), and yam8Δ (cross).

Lastly, we determined whether the yam8 deletion had any effect on the Ca2+-dependent ncs1 promoter activity. The transcriptional reporter assay performed on yam8Δ showed an increase in reporter activity after growing in the presence of 0.1 m Ca2+. Thus, the yam8 deletion does not prevent Ca2+-induced activation of the ncs1 promoter, suggesting that one or more other calcium channels in fission yeast can enable Ca2+ influx needed to up-regulate ncs1 promoter activity.

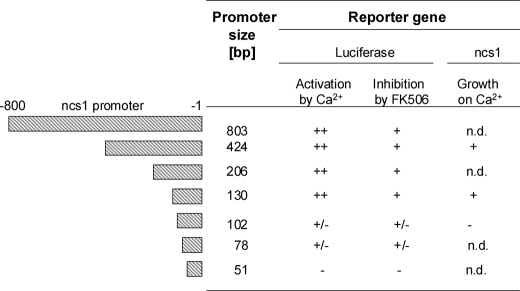

Location of the Ncs1 Promoter

To identify the precise DNA sequence in the ncs1 promoter region responsible for promoting Ca2+-induced transcription, various sized DNA fragments upstream of the start codon were constructed and examined for their transcriptional activity using the luciferase reporter assay described above. The nucleotide numbering in the promoter region was defined such that “A” from the start codon is assigned as zero. Various sized fragments of the promoter region were constructed starting at nucleotide numbers −666, −424, −313, −206, −183, −155, −130, −102, −78, and −51, and ending at nucleotide −1. Each fragment was tested for up-regulation at 0.1 m calcium chloride in liquid media. Representative results are listed in Fig. 6. The results show that the 130-bp promoter fragment (i.e. nucleotides from −130 to −1, called mec1) was the minimal sequence that produced full Ca2+-induced up-regulation that was also aborted by addition of calcineurin inhibiter, FK506. The Ca2+-induced up-regulation was partially lost by deleting an additional 28 bases and completely lost by deleting 79 more bases (Fig. 6). Thus, the nucleotides between −130 to −1 are necessary for Ca2+-induced transcription. The 130-bp fragment always gave slightly higher activation than longer fragments (data not shown). This suggests the possibility that the region between −130 and −155 might interact with a suppressor. Lastly, the basal activity of the ncs1 promoter (in the absence of calcium) dropped as the promoter was shortened from 130 to 102 bp and eliminated altogether when the promoter was shortened from 78 to 51 bp (data not shown). These results indicate that nucleotides between −103 to −51 and including the TATA box (−48 to −43) are important for controlling basal expression as well.

FIGURE 6.

Localization of ncs1 promoter region responsible for calcium-dependent up-regulation. Reporter assay was carried out in the same manner as Fig. 2 except ncs1 promoter mec803 was replaced by mec424, mec206, mec130, mec102, mec78, or mec51. Promoter activation level was indicated by ++ (>20-fold), +/− (5- to 10-fold), and − (<5-fold).

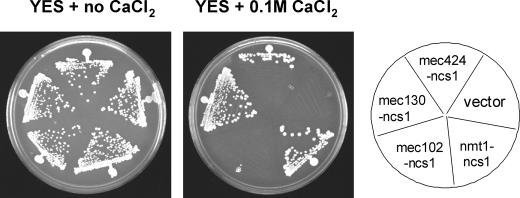

The various ncs1 promoter constructs above were tested for their ability to control expression of recombinant Ncs1p and rescue Ca2+ tolerance in ncs1Δ cells. Yeast strains were prepared that express recombinant Ncs1p protein in ncs1Δ background using a plasmid system containing ncs1 cDNA placed under the various ncs1 promoter fragments described above. The ncs1Δ cells that bear the ncs1 expression plasmid containing either mec1(424-1), mec1(130-1), or mec1(102-1) were all tested on calcium plates. The 130-bp promoter construct was sufficient to support growth of ncs1Δ on 0.1 m Ca2+, whereas the 102-bp promoter construct did not (Figs. 3, 6, and 7). These measurements suggest that the region responsible for calcium-induced up-regulation lies somewhere between nucleotides −130 and −1 in the ncs1 promoter. This region does not contain any sequence elements resembling the CDRE motif found in S. cerevisiae (59).

FIGURE 7.

The 130-bp fragment from ncs1 promoter enables high enough expression of ncs1 gene to permit growth of ncs1Δ mutant on agar plate with 0.1 m calcium chloride. The Ncs1Δ mutant strain, which is unable to grow on calcium plates, was transformed with pREP4X-mec424-ncs1, pREP4X-mec130-ncs1, or pREP4X-p102-ncs1, in which nmt1 promoter in pREP-ncs1 was replaced with 424-, 130-, or 102-bp fragments from ncs1 promoter. vector = pREP4X alone; nmt1-ncs1 = original pREP4X (with nmt1 promoter)-ncs1 open reading frame.

We have constructed an inducible expression vector system for fission yeast that harbors mec1(130-1) and contains a selectable marker gene (ura4+). This expression system enables general expression of recombinant genes in fission yeast grown on media lacking uracil and extracellular Ca2+. The amount of inducible expression is controlled by changing the extracellular Ca2+ concentration. Maximal expression occurs when the extracellular Ca2+ concentration is raised above 0.1 m Ca2+.

Prz1p Binding to ncs1 Promoter

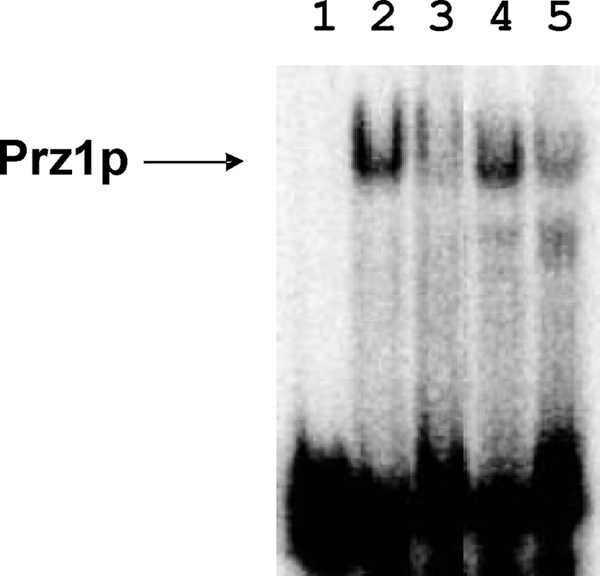

Electrophoresis mobility shift assays (EMSAs) were performed to monitor direct binding of Prz1p to oligonucleotide fragments of the ncs1 promoter (Fig. 8). Reporter assays above (Figs. 6 and 7) demonstrate that Ca2+-induced ncs1 promoter activity requires the 30-bp nucleotide sequence (nucleotides −130 to −101). EMSA experiments show that recombinant Prz1p binds specifically to this 30-bp duplex DNA sequence (Fig. 8, lane 2), but Prz1p does not bind to the same sized duplex having a random sequence (see cold-chase experiments in Fig. 8, compare lanes 3 and 4). Prz1p shows weakened binding to a mutant sequence (nucleotides −111 to −107 changed to 5′-aggac-3′; Fig. 8, lane 5), suggesting this conserved sequence motif (5′-caact-3′, see “Discussion”) contributes to sequence specific binding.

FIGURE 8.

Electrophoretic mobility shift assay of Prz1p binding to ncs1 promoter sequence. 5 nm of Cy5 labeled duplex DNA (see “Experimental Procedures”) in 10 mm HEPES (pH 7.5), 0.1 m NaCl, and 5 mm Mg2+ was incubated with buffer blank (lane 1) and recombinant Prz1p (lanes 2–5). Cold-chase experiments (see “Experimental Procedures”) were performed using unlabeled wild-type sequence (lane 3), unlabeled random sequence (lane 4), and unlabeled mutant sequence (nucleotides −111 to −107 changed to AGGAC, lane 5).

DISCUSSION

The neuronal calcium sensor (NCS) proteins regulate a variety of physiological targets in signal transduction and are highly conserved from yeast to humans (17, 65, 66). Previous gene knockout studies revealed that S. pombe NCS homolog (Ncs1p) is essential for the growth of yeast cells in the presence of extreme Ca2+ (15). The exposure of yeast cells to very high extracellular Ca2+ levels (>0.1 m) causes a dramatic increase in the expression of S. pombe Ncs1p that somehow protects yeast from toxic effects of high Ca2+. In this study, we further characterized the molecular mechanism and physiological relevance of the Ca2+-sensitive ncs1Δ phenotype. Our studies reveal that Ca2+-induced expression of S. pombe Ncsp1 is controlled at the level of transcription (Fig. 1). The fission yeast ncs1 promoter consists of a short 130-bp region (mec1) upstream from the start codon that is responsible for Ca2+-induced transcription of ncs1 (Fig. 6). The ncs1 up-regulation is Ca2+ specific (Fig. 2) and essential for Ca2+ tolerance (Fig. 7). The Ca2+-sensitive ncs1 promoter activity is lost in prz1− mutant, and abolished by the calcineurin inhibitor, FK506. Also, Prz1p binds directly to a 30-bp sequence in mec1 (Fig. 8). Thus, the calcineurin-prz1 pathway (47, 48) is necessary for controlling Ca2+-induced transcription of ncs1. This is the first demonstration of an NCS protein whose expression is regulated by calcineurin. We propose that other NCS proteins might be similarly coupled to calcineurin signaling in neurons. Indeed, mammalian calcineurin regulates the transcription factor, NFAT, during the activation of T-lymphocytes (67). NFAT recognizes the calcium-responsive promoter sequence (GGAAA) found in the promoters of both mammalian recoverin (starting at nucleotide −203) and NCS-1 (at −930). An important next step will be to explore whether Ca2+-induced transcription of NCS proteins in mammalian cells is regulated by the calcineurin/NFAT pathway.

The S. pombe ncs1 promoter region contains a number of repetitive sequence elements (5′-caact-3′) that we show contribute to sequence-specific binding by Prz1p (Fig. 8) and may represent Ca2+-dependent response elements. Analysis of the nucleotide sequence of the ncs1 promoter revealed the sequence, 5′-caact-3′, repeated at positions −151 to −147, −136 to −131, −111 to −107, −105 to −101, −85 to −80, and −36 to −31. We especially note that the motifs at −111 to −107 and −105 to −101 are located nearly in tandem. The fission yeast genes pmc1 (P-type Ca2+-ATPase) and pmr1 (P-type Ca2+/Mn2+-ATPase) also exhibit Ca2+-induced transcription controlled by the calcineurin/prz1 pathway (48, 68). The pmc1 promoter contains the 5′-caact-3′ sequence in tandem starting at nucleotides −521 to −517 and repeated at −516 to −512. The pmr1 promoter contains 5′-caact-3′ starting at −564 to −560 and also at −55 to −51. The calcium-responsive ncs1 promoter region (mec1) recognized by Prz1p in fission yeast does not contain the CDRE observed previously in budding yeast (59). A few budding yeast CDRE sequences could be identified upstream of the S. pombe ncs1 promoter located between nucleotides −666 and −424. However, deletion of these CDRE sequences had no effect on Ca2+-dependent up-regulation of ncs1 promoter activity. Thus, the calcium-responsive ncs1 promoter sequence in fission yeast (mec1) is quite distinct from the CDRE reported for budding yeast.

Regulation of the ncs1 promoter in S. pombe is different from that of FRQ1 in S. cerevisiae. We showed in this study that the transcription of the ncs1 gene in fission yeast is clearly up-regulated by the calcineurin/prz1 pathway. By stark contrast, the ncs1 homolog in S. cerevisiae (FRQ1) was not identified as a TCN1/CRZ1-regulated gene in a genome-wide microarray screening (53). So, expression of FRQ1 is not regulated by the homologous calcineurin/CRZ1 pathway in budding yeast. Also, when a corresponding mec803-GFP transcriptional reporter construct was introduced into budding yeast cells, the GFP expression and hence transcription was not enhanced by increasing the extracellular Ca2+ concentration. Thus, the S. pombe ncs1 promoter sequence does not produce any Ca2+-induced reporter activity in the context of budding yeast and apparently is not recognized by the S. cerevisiae calcineurin/CRZ1 transcriptional machinery.

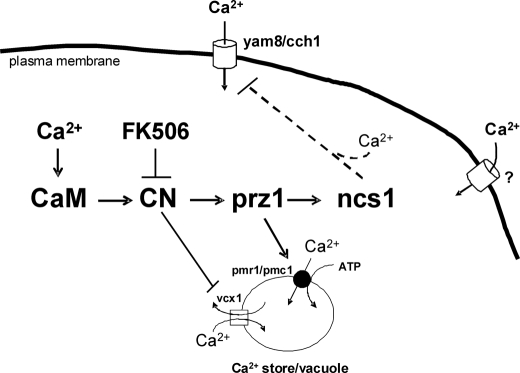

What is the biochemical mechanism and function of S. pombe Ncs1p that contributes to Ca2+ tolerance in fission yeast (Fig. 9)? The simplest function would be that Ncs1p is simply acting as a cytosolic Ca2+ buffer to chelate incoming Ca2+ under extreme external conditions (>0.1 m Ca2+). However, previous studies showed that the calcium-sensitive ncs1Δ phenotype is not complemented by overexpressing recombinant Frq1, but the Ca2+ intolerance is rescued by expressing a similar amount of recombinant Ncs1p (15). Frq1 binds Ca2+ with nearly the same capacity as Ncs1p (69); therefore, the lack of any complementation by Frq1 suggests that cytosolic buffering alone is not sufficient for Ca2+ tolerance and that Ncs1p must possess a separate and unique function (not performed by Frq1) that protects the cell.

FIGURE 9.

Schematic model of Ca2+-induced expression of ncs1 up-regulated by calcineurin to promote Ca2+ tolerance in fission yeast. Extracellular Ca2+ enters the cell through Ca2+ channels, causing a rise in intracellular Ca2+ concentration that activates the calcineurin pathway, leading to Ca2+-induced transcription of ncs1. The Ca2+-bound form of Ncs1p interacts with the Yam8p Ca2+ channel to promote channel closure and thus block the entry of extracellular Ca2+ under extreme conditions.

We propose that Ncs1p may serve as a Ca2+ sensor for ion channels (Fig. 9), analogous to the role of CaM in promoting Ca2+-induced closure of voltage-gated Ca2+ channels (61, 62). Ca2+-induced regulation of ion channels is also performed by various NCS proteins, including KChIPs (42), NCS-1 (44, 70), and CaBP1 (71, 72). In this study, we provide evidence that Ncs1p promotes Ca2+-induced closure of Yam8p Ca2+ channels (Figs. 4 and 5 and Table 3). Ca2+-induced channel closure would then restrict and minimize Ca2+ influx under extreme external conditions to help maintain viable cytosolic Ca2+ levels and prevent cell death.

Ncs1p might also serve as a Ca2+ sensor for the two Ca2+-ATPase pumps, pmr1 (48) and pmc1 (73) (Fig. 9). Both pmr1 and pmc1 are up-regulated by the calcineurin/prz1 pathway (48). Thus, Ca2+-induced expression of Ncs1p, Pmr1p, and Pmc1p should generate similar levels of all three proteins, making it possible for Ncs1p to bind and serve as a regulatory subunit for each pump or perhaps assist in the trafficking of these pumps to cell membranes. Indeed, NCS proteins have been shown to facilitate Ca2+-induced trafficking of ion channels and other membrane proteins (74, 75). Ca2+-induced activation of Ca2+ pumps could maximize Ca2+ efflux under extreme external conditions and thereby help maintain a viable cytosolic Ca2+ concentration. Future studies are needed to explore Ca2+-induced regulation of Ca2+ pumps by Ncs1p.

Our study suggests that calcineurin regulates more than one pathway to promote Ca2+ tolerance in fission yeast (Fig. 9). One pathway involves prz1 to up-regulate the transcription of ncs1. However, the fact that calcineurin inhibitor (FK506) restores Ca2+ tolerance in both ncs1Δ and prz1− (Fig. 3) indicates that calcineurin must also operate on separate targets independent of prz1 and ncs1. In budding yeast, calcineurin catalyzes dephosphorylation of the Ca2+ exchanger Vcx1, causing a steep decline in Ca2+ transport into vacuoles (60). Protein phosphorylation also regulates the opening of Ca2+ channels in budding yeast (63). Thus, calcineurin promotes calcium tolerance by controlling at least two separate pathways: 1) Prz1p-dependent up-regulation of ncs1 (this study) and pmc1/pmr1 (47, 48) and 2) dephosphorylation and inhibition of the Vcx1 Ca2+ exchanger (60).

Lastly, we present a new protein expression vector system that bears the calcium-sensitive ncs1 promoter (mec1) and is capable of producing inducible expression of recombinant genes in fission yeast (Fig. 6). The basal activity of the mec1 promoter is reasonably low and induction of protein expression can be achieved by simply raising the extracellular Ca2+ concentration to 10 mm, which then leads to a rapid rise in protein expression over a period of 0.5–2.0 h. The relatively short induction period is a great advantage for kinetic studies not possible with most commonly used inducible expression systems. The amount of inducible expression from our system is 30- to 100-fold higher than the basal level and remains stable for a period of 24 h or longer. This level of induction is comparable to that of the nmt1* promoter, of medium strength (76) with which removal of thiamine from the media, the induction process, takes much more time. We recommend that our newly constructed expression vector with ncs1 promoter could be used as a useful inducible expression system where rapid induction is critical and high levels of extracellular calcium do not affect the factors of interest.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Daniel C. Masison for generously providing a plasmid pDCM58, Dr. Ian M. Hagan for plasmid pREP42EGFP-C, Dr. Y. Sanchez for a fission yeast strain HC3, and Dr. Takayoshi Kuno for providing fission yeast strain KP2758. We thank Dr. Alexandra Dace and Dr. Aswani Valiveti for helpful discussion and suggestions.

This work was supported, in whole or in part, by National Institutes of Health Grants EY012347 and NS059969 (to J. B. A.).

- NCS

- neuronal calcium sensor

- CaM

- calmodulin

- CDRE

- calcineurin-dependent response element

- CN

- calcineurin

- EMSA

- electrophoretic mobility shift assay

- GFP

- green fluorescent protein

- mec1

- more expression with calcium 1

- ncs1Δ

- ncs1 deletion mutant

- Ncs1p

- protein coded by S. pombe gene, ncs1

- NFAT

- nuclear factor of activated T-cells.

REFERENCES

- 1.Catty P., Goffeau A. (1996) Biosci. Rep. 16, 75–85 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Davis T. N. (1995) Adv. Second Messenger Phosphoprotein Res. 30, 339–358 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Okorokov L. A., Silva F. E., Okorokova, Façanha A. L. (2001) FEBS Lett. 505, 321–324 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Berridge M. J. (1997) J. Physiol. 499, 291–306 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Carnero E., Ribas J. C., García B., Durán A., Sanchez Y. (2000) Mol. Gen. Genet. 264, 173–183 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tasaka Y., Nakagawa Y., Sato C., Mino M., Uozumi N., Murata N., Muto S., Iida H. (2000) Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 269, 265–269 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Façanha A. L., Appelgren H., Tabish M., Okorokov L., Ekwall K. (2002) J. Cell Biol. 157, 1029–1039 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Halachmi D., Ghislain M., Eilam Y. (1992) Eur. J. Biochem. 207, 1003–1008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ghislain M., Goffeau A., Halachmi D., Eilam Y. (1990) J. Biol. Chem. 265, 18400–18407 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Iida H., Yagawa Y., Anraku Y. (1990) J. Biol. Chem. 265, 13391–13399 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Muend S., Rao R. (2008) FEMS Yeast Res. 8, 425–431 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ikura M. (1996) Trends Biochem. Sci. 21, 14–17 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Moser M. J., Flory M. R., Davis T. N. (1997) J. Cell Sci. 110, 1805–1812 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sio S. O., Suehiro T., Sugiura R., Takeuchi M., Mukai H., Kuno T. (2005) J. Biol. Chem. 280, 12231–12238 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hamasaki-Katagiri N., Molchanova T., Takeda K., Ames J. B. (2004) J. Biol. Chem. 279, 12744–12754 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Burgoyne R. D., Weiss J. L. (2001) Biochem. J. 353, 1–12 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Braunewell K. H., Gundelfinger E. D. (1999) Cell Tissue Res. 295, 1–12 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Palczewski K., Polans A. S., Baehr W., Ames J. B. (2000) BioEssays 22, 337–350 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kawasaki H., Nakayama S., Kretsinger R. H. (1998) Biometals 11, 277–295 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yap K. L., Ames J. B., Swindells M. B., Ikura M. (1999) Proteins 37, 499–507 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dizhoor A. M., Ray S., Kumar S., Niemi G., Spencer M., Brolley D., Walsh K. A., Philipov P. P., Hurley J. B., Stryer L. (1991) Science 251, 915–918 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chen C. K., Inglese J., Lefkowitz R. J., Hurley J. B. (1995) J. Biol. Chem. 270, 18060–18066 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kawamura S. (1993) Nature 362, 855–857 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Erickson M. A., Lagnado L., Zozulya S., Neubert T. A., Stryer L., Baylor D. A. (1998) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 95, 6474–6479 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hidaka H., Okazaki K. (1993) Neurosci. Res. 16, 73–77 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kobayashi M., Takamatsu K., Saitoh S., Noguchi T. (1993) J. Biol. Chem. 268, 18898–18904 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pongs O., Lindemeier J., Zhu X. R., Theil T., Engelkamp D., Krah-Jentgens I., Lambrecht H. G., Kock K. W., Schwemer J., Rivosecchi R. (1993) Neuron 11, 15–28 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hendricks K. B., Wang B. Q., Schnieders E. A., Thorner J. (1999) Nat. Cell Biol. 1, 234–241 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Flaherty K. M., Zozulya S., Stryer L., McKay D. B. (1993) Cell 75, 709–716 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ames J. B., Ishima R., Tanaka T., Gordon J. I., Stryer L., Ikura M. (1997) Nature 389, 198–202 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bourne Y., Dannenberg J., Pollmann V., Marchot P., Pongs O. (2001) J. Biol. Chem. 276, 11949–11955 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Strahl T., Huttner I. G., Lusin J. D., Osawa M., King D., Thorner J., Ames J. B. (2007) J. Biol. Chem. 282, 30949–30959 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Vijay-Kumar S., Kumar V. D. (1999) Nat. Struct. Biol. 6, 80–88 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ames J. B., Dizhoor A. M., Ikura M., Palczewski K., Stryer L. (1999) J. Biol. Chem. 274, 19329–19337 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Stephen R., Bereta G., Golczak M., Palczewski K., Sousa M. C. (2007) Structure 15, 1392–1402 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ames J. B., Levay K., Wingard J. N., Lusin J. D., Slepak V. Z. (2006) J. Biol. Chem. 281, 37237–37245 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zozulya S., Stryer L. (1992) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 89, 11569–11573 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Dizhoor A. M., Chen C. K., Olshevskaya E., Sinelnikova V. V., Phillipov P., Hurley J. B. (1993) Science 259, 829–832 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Dizhoor A. M., Lowe D. G., Olshevskaya E. V., Laura R. P., Hurley J. B. (1994) Neuron 12, 1345–1352 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Palczewski K., Subbaraya I., Gorczyca W. A., Helekar B. S., Ruiz C. C., Ohguro H., Huang J., Zhao X., Crabb J. W., Johnson R. S. (1994) Neuron 13, 395–404 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Zhao C. J., Noack C., Brackmann M., Gloveli T., Maelicke A., Heinemann U., Anand R., Braunewell K. H. (2009) Mol. Cell. Neurosci. 40, 280–292 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.An W. F., Bowlby M. R., Betty M., Cao J., Ling H. P., Mendoza G., Hinson J. W., Mattsson K. I., Strassle B. W., Trimmer J. S., Rhodes K. J. (2000) Nature 403, 553–556 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Tzingounis A. V., Kobayashi M., Takamatsu K., Nicoll R. A. (2007) Neuron 53, 487–493 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Tsujimoto T., Jeromin A., Saitoh N., Roder J. C., Takahashi T. (2002) Science 295, 2276–2279 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Strahl T., Grafelmann B., Dannenberg J., Thorner J., Pongs O. (2003) J. Biol. Chem. 278, 49589–49599 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Strahl T., Hama H., DeWald D. B., Thorner J. (2005) J. Cell Biol. 171, 967–979 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Deng L., Sugiura R., Takeuchi M., Suzuki M., Ebina H., Takami T., Koike A., Iba S., Kuno T. (2006) Mol. Biol. Cell 17, 4790–4800 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hirayama S., Sugiura R., Lu Y., Maeda T., Kawagishi K., Yokoyama M., Tohda H., Giga-Hama Y., Shuntoh H., Kuno T. (2003) J. Biol. Chem. 278, 18078–18084 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Moreno S., Klar A., Nurse P. (1991) Methods Enzymol. 194, 795–823 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Escher A., O'Kane D. J., Lee J., Szalay A. A. (1989) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 86, 6528–6532 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Jones G., Song Y., Chung S., Masison D. C. (2004) Mol. Cell. Biol. 24, 3928–3937 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Osawa M., Tong K. I., Lilliehook C., Wasco W., Buxbaum J. D., Cheng H. Y., Penninger J. M., Ikura M., Ames J. B. (2001) J. Biol. Chem. 276, 41005–41013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Yoshimoto H., Saltsman K., Gasch A. P., Li H. X., Ogawa N., Botstein D., Brown P. O., Cyert M. S. (2002) J. Biol. Chem. 277, 31079–31088 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Carrión A. M., Link W. A., Ledo F., Mellström B., Naranjo J. R. (1999) Nature 398, 80–84 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Cheng H. Y., Pitcher G. M., Laviolette S. R., Whishaw I. Q., Tong K. I., Kockeritz L. K., Wada T., Joza N. A., Crackower M., Goncalves J., Sarosi I., Woodgett J. R., Oliveira-dos-Santos A. J., Ikura M., van der Kooy D., Salter M. W., Penninger J. M. (2002) Cell 108, 31–43 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Cyert M. S. (2003) Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 311, 1143–1150 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Moser M. J., Geiser J. R., Davis T. N. (1996) Mol. Cell. Biol. 16, 4824–4831 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Nakamura T., Liu Y., Hirata D., Namba H., Harada S., Hirokawa T., Miyakawa T. (1993) EMBO J. 12, 4063–4071 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Stathopoulos A. M., Cyert M. S. (1997) Genes Dev. 11, 3432–3444 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Cunningham K. W., Fink G. R. (1996) Mol. Cell. Biol. 16, 2226–2237 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Dick I. E., Tadross M. R., Liang H., Tay L. H., Yang W., Yue D. T. (2008) Nature 451, 830–834 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Zühlke R. D., Pitt G. S., Deisseroth K., Tsien R. W., Reuter H. (1999) Nature 399, 159–162 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Bonilla M., Cunningham K. W. (2003) Mol. Biol. Cell 14, 4296–4305 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Eilam Y., Chernichovsky D. (1987) J. Gen. Microbiol. 133, 1641–1649 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Ames J. B., Tanaka T., Stryer L., Ikura M. (1996) Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 6, 432–438 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Burgoyne R. D., O'Callaghan D. W., Hasdemir B., Haynes L. P., Tepikin A. V. (2004) Trends Neurosci. 27, 203–209 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Crabtree G. R., Olson E. N. (2002) Cell 109, S67–S79 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Maeda T., Sugiura R., Kita A., Saito M., Deng L., He Y., Yabin L., Fujita Y., Takegawa K., Shuntoh H., Kuno T. (2004) Genes Cells 9, 71–82 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Ames J. B., Hendricks K. B., Strahl T., Huttner I. G., Hamasaki N., Thorner J. (2000) Biochemistry 39, 12149–12161 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Nakamura T. Y., Pountney D. J., Ozaita A., Nandi S., Ueda S., Rudy B., Coetzee W. A. (2001) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 98, 12808–12813 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Yang J., McBride S., Mak D. O., Vardi N., Palczewski K., Haeseleer F., Foskett J. K. (2002) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 99, 7711–7716 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Kasri N. N., Holmes A. M., Bultynck G., Parys J. B., Bootman M. D., Rietdorf K., Missiaen L., McDonald F., De Smedt H., Conway S. J., Holmes A. B., Berridge M. J., Roderick H. L. (2004) EMBO J. 23, 312–321 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Furune T., Hashimoto K., Ishiguro J. (2008) Genes Genet. Syst. 83, 373–381 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Braunewell K. H., Klein-Szanto A. J., Szanto A. J. (2009) Cell Tissue Res. 335, 301–316 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Shibata R., Misonou H., Campomanes C. R., Anderson A. E., Schrader L. A., Doliveira L. C., Carroll K. I., Sweatt J. D., Rhodes K. J., Trimmer J. S. (2003) J. Biol. Chem. 278, 36445–36454 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Forsburg S. L. (1993) Nucleic Acids Res. 21, 2955–2956 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]