Abstract

Cytochrome c oxidase is a member of the heme-copper family of oxygen reductases in which electron transfer is linked to the pumping of protons across the membrane. Neither the redox center(s) associated with proton pumping nor the pumping mechanism presumably common to all heme-copper oxidases has been established. A possible conformational coupling between the catalytic center (Fea33+–CuB2+) and a protein site has been identified earlier from ligand binding studies, whereas a structural change initiated by azide binding to the protein has been proposed to facilitate the access of cyanide to the catalytic center of the oxidized bovine enzyme. Here we show that cytochrome oxidase pretreated with a low concentration of azide exhibits a significant increase in the apparent rate of cyanide binding relative to that of free enzyme. However, this increase in rate does not reflect a conformational change enhancing the rapid formation of a Fea33+–CN–CuB2+ complex. Instead the cyanide-induced transition of a preformed Fea33+–N3–CuB2+ to the ternary complex of Fea33+–N3 CuB2+–CN is the most likely reason for the observed acceleration. Significantly, the slow rate of azide release from the ternary complex indicates that cyanide ligated to CuB blocks a channel between the catalytic site and the solvent. The results suggest that there is a pathway that originates at CuB and that, during catalysis, ligands present at this copper center control access to the iron of heme a3 from the bulk medium.

Keywords: Bioenergetics/Respiratory Chain, Enzymes/Inhibitors, Enzymes/Mechanisms, Enzymes/Oxidase, Methods/Electron Paramagnetic Resonance EPR, Methods/FTIR

Introduction

Cellular respiration involves membrane-bound complexes that catalyze the coupling of electron transfer to formation of a proton gradient. Cytochrome c oxidases, terminal enzymes in mitochondria and many prokaryotes, are members of a family of heme-copper oxygen reductases sharing a common structure at the heme a3–CuB catalytic site. In oxidases, two different mechanisms for the coupling between electron transport and proton translocation are utilized. The first is Mitchell's loop mechanism in which oxidation of substrate at one side of membrane is associated with the uptake of protons from the opposite side. These protons, called scalar protons, are incorporated into water produced during the reduction of oxygen. In the second mechanism, proton pumping, originally discovered by Wikström (1), the transfer of protons across the membrane is driven by the free energy provided by the redox reactions. The net reaction catalyzed by cytochrome c oxidases is

where Hi+ represents protons taken up from the interior phase, Ho+ represents protons released into the exterior domain, and c2+ and c3+ are reduced and oxidized cytochrome c, respectively.

Mammalian cytochrome c oxidase (CcO)3 is composed of 13 subunits (2), but only two of them contain redox active cofactors (3). Four redox centers, CuA, CuB, and two hemes, heme a and a3, are located in subunit I and II and buried within the protein matrix. CuA, a dinuclear copper site, is the initial electron acceptor from reduced cytochrome c. Electron flow then continues to heme a and then to the binuclear heme a3–CuB center. At this binuclear center, the interaction of O2, electrons, and protons takes place, and oxygen is reduced to water. This center is also a site where inhibitors of respiration are bound.

In oxidized bovine CcO, the low spin ferric iron of heme a (Fea3+) is axially coordinated by His-68 and His-378, whereas His-376 is the axial ligand to the high spin iron of heme a3 (Fea33+) (3). CuB is ligated by His-290, His-291, and His-240. The distance between Fea3 and CuB is ∼5 Å, and the high spin ferric iron and this cupric ion are magnetically coupled (4). From spectroscopic studies (5) and the x-ray structure (6), it was clear that there is a bridging ligand mediating the interaction between Fea3 and CuB in the oxidized enzyme. However, the chemical nature of this native ligand has yet to be established. Suggestions for this molecular bridge include water or hydroxide (7, 8), water plus hydroxide (9, 10), and even peroxide (11).

As the catalytic site is completely shielded by protein from the external solution, channels or pathways connecting this site with the solvent are required. These channels are needed to facilitate the access of both oxygen (3, 12) and protons (13) and to release pumped protons (14) and water (15, 16).

Despite intensive investigations, neither the redox center(s) associated with proton pumping nor the pumping mechanism common to the family of heme-copper oxidases has been established. A number of models have been proposed. In these models, a key component is an electrostatic interaction between the redox centers and some acid-base groups (17–22) or conformational change, such as the redox Bohr effect (23–26). In most cases, the catalytic center is expected to play a principal role in the pumping, and certain structural rearrangements in the coordination of Fea3 and CuB site have been postulated (27).

The identification and characterization of coupling interactions between the redox centers and distant protein sites are essential for an understanding of oxidase catalysis and for choosing between the current pumping models. From a study of the interaction of ligands with oxidized CcO, a structural change at the catalytic center accompanying azide binding to a protein site has already been proposed (28). The presence of azide at this protein site appears to trigger a structural change observed as an acceleration of cyanide binding to heme a3.

A protein binding site for azide was identified in the x-ray structure of the complex of bovine CcO with azide (29). Altogether, two azide ions were determined in this structure. The first is located at the catalytic center between Fea3 and CuB, and the second is hydrogen-bonded to Asn-422 and Tyr-379, in proximity to the iron of heme a. Thus it may appear that azide binding to the Asn-422/Tyr-379 duo stimulates a specific transition at the catalytic center.

Here we investigated the interaction of azide and cyanide, either singly or together, with oxidized enzyme by UV-visible, electron paramagnetic resonance, and Fourier-transform infrared spectroscopy. It is shown that the presumed conformational interaction between the distal azide binding site and the heme a3–CuB center is not very likely. Rather it appears that the acceleration of absorbance changes observed in the presence of azide results from cyanide binding to CuB in the preformed complex of Fea33+–N3–CuB2+. Production of the novel Fea33+–N3 CuB2+–CN ternary structure monitored by UV-visible spectroscopy resembles cyanide coordination to heme a3. Remarkably, the cyanide coordinated to CuB significantly suppresses dissociation of azide from this ternary complex. Our results, taken together with published data, suggest that CuB is the entry and exit point for ligands from heme a3 in both oxidized and reduced enzyme. The data also imply that alteration of the ligation of CuB can be a gating mechanism controlling the opening of a passage between heme a3 and the solvent during turnover.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Materials

Hepes buffer was purchased from Sigma, peroxide-free Triton X-100 was from Roche Diagnostics, n-dodecyl-β-d-maltoside (DM) was from Anatrace, sodium cyanide was from Mallinckrodt, and sodium azide was from Kodak.

Enzyme Purification

Bovine heart CcO was isolated from mitochondria by the modified method of Soulimane and Buse (30) (see Ref. 31 for modifications) into DM-containing buffer (10 mm Hepes, pH 7.8, 100 mm K2SO4, and 0.05% DM).

Preparation of Samples

Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR) was performed on oxidase in aqueous buffers (100 mm Hepes, pH 7.8, 50 mm K2SO4, 0.05% DM). The concentration of oxidase was typically ∼0.7 mm. Spectra were collected in a CaF2 cell of 0.04-mm path length using a Nexus 470 FT-IR spectrometer at room temperature. The FTIR spectrometer was equipped with a liquid nitrogen-cooled mercury cadmium telluride detector and an 1800–2400-cm−1 band pass filter (Laser Components, Inc., Santa Rosa CA) in the light path. The data consisted of 1024 co-added interferograms usually recorded with a spectral resolution of 1 cm−1. The FTIR data are presented as the difference of the complex of oxidase with ligands minus the spectrum of untreated enzyme. The spectra were also subjected to baseline correction over the range of interest.

Samples for EPR were first frozen in methanol plus dry ice and then transferred to liquid nitrogen for storage. Spectra were recorded at 10 K using a Bruker EMX spectrometer, the microwave frequency was 9.26 GHz, with a power of 3 milliwatts, a modulation amplitude of 10 G, a modulation frequency of 100 kHz, and a time constant of 323 ms. All samples were prepared in a buffer consisting of 10 mm Hepes, pH 7.8, 50 mm K2SO4, 0.1% Triton X-100.

To prepare the complex with either azide or cyanide, oxidized enzyme was incubated with the appropriate ligand for 15 min at room temperature. Complexes containing both azide and cyanide were produced by preincubation of enzyme with azide at room temperature for 15 min before the addition of cyanide. After the changes in the optical spectrum induced by cyanide were fully developed, the samples were utilized for FTIR or EPR measurements.

To remove the ligands from solution, the enzyme was passed through a column of Sephadex G 25 (2 × 25 cm) equilibrated with Hepes buffer at 4 °C. The oxidase diluted by gel filtration was concentrated by centrifugation in an Amicon ultrafiltration cone with a molecular mass cut-off of 50 kDa. The UV-visible spectra of the samples for the FTIR measurements were collected directly in the FTIR cuvette with the HP8453 diode array spectrometer at 23 °C.

RESULTS

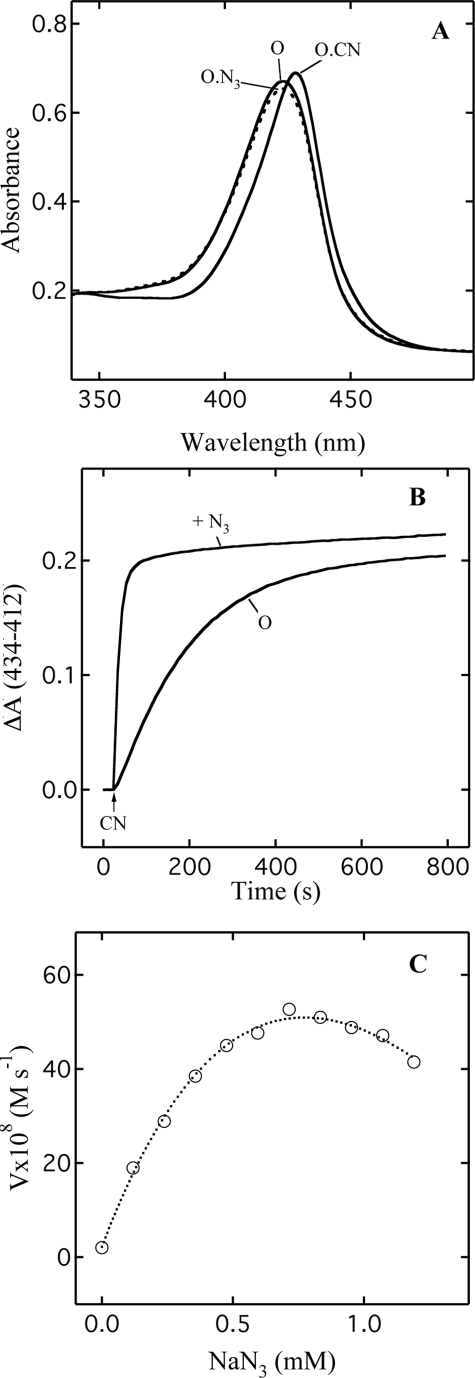

Replacing the native ligand present at the catalytic site of oxidized enzyme with external ligands influences the optical spectrum of heme a3 and can change the spin state of the ferric iron. An illustration of this effect for both azide and cyanide on the Soret band of bovine enzyme is shown in Fig. 1. The binding of cyanide results in a marked alteration of the spectrum with a shift of the absorbance maximum from 424 to 428 nm (Fig. 1A). This optical transition is associated with a change of Fea33+ from high spin to low spin (32). In contrast, the effect of 200 μm azide on the spectrum is very subtle with only a slight absorbance decrease in the Soret band (Fig. 1A). At this concentration of azide, there is no a change in the spin state of Fea33+ (33).

FIGURE 1.

Influence of azide on the optical spectrum of oxidized cytochrome oxidase and the spectral change triggered by the addition of cyanide. A, the Soret band spectra of oxidized CcO (O), in the presence of 0.2 mm NaN3 (O.N3) and 2 mm NaCN (O.CN). B, the kinetics of spectral change in the Soret band initiated by the addition of 2 mm NaCN to oxidized CcO (O) and to the solution of enzyme containing 0.2 mm NaN3 (+N3). C, the dependence of the initial rates of the spectral change induced by 2 mm NaCN on the concentration of azide in the solution. The dotted guideline is used to highlight two opposite effects of azide. Conditions of measurements are as follows: concentration of CcO, 4.2 μm; buffer, 100 mm Hepes, pH 7.8, 50 mm K2SO4, 0.05% DM; temperature, 23 °C.

By monitoring the changes in the Soret band, the kinetics of cyanide binding to oxidized CcO can be measured. With 2 mm cyanide, the kinetics are pseudo first order and are well described by a single exponential function (Fig. 1B). The kinetics are, however, sensitive to the presence of azide in the reaction mixture. For example, the binding of cyanide to oxidase pretreated with 200 μm NaN3 (Fig. 1B) is strongly enhanced when compared with the sample in which azide is absent (Fig. 1B). In both cases, the spectra are nearly identical with the Soret band located at 428 nm at the end of reaction (Fig. 1A), indicating that in both situations, all of Fea33+ has been converted to the low spin state.

However, in the presence of azide, the kinetics cannot be fitted by a single exponential function. Therefore we use the initial rate of the spectral changes induced by cyanide in the presence of azide to assess the effect of azide concentration (Fig. 1C). At pH 7.8, this rate increases with increasing azide concentration up to ∼0.7 mm; above that concentration, a decline in rates is observed. Thus azide exhibits two opposing effects on the reaction with cyanide, stimulation at lower concentrations and an inhibition at higher concentrations. The acceleration of cyanide binding is unexpected because both ligands are believed to compete for the same binding site, namely Fea3–CuB. Consequently, the original expectation was that the pretreatment of enzyme with azide should decrease the rate of cyanide binding.

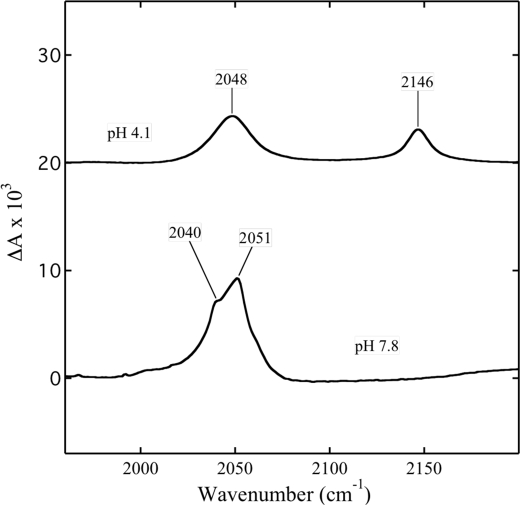

To better understand this stimulation, we extended this investigation of the ligand interaction with oxidase using FTIR and EPR spectroscopy. Both ligands are infrared-active, and their binding to protein is revealed by changes in their infrared stretching frequencies. Free azide in water solution displays FTIR absorbance at 2146 and 2048 cm−1 at pH 4.1 (Fig. 2). The stretch at 2146 cm−1 represents the protonated form of HN3, and that at 2048 cm−1 originates from the anion of N3− (33, 34). When the complex of CcO with azide is prepared by the addition of a stoichiometric amount of ligand to the enzyme, two new bands are observed, at 2051 and 2040 cm−1 (Fig. 2). The infrared absorbance at 2051 cm−1 was assigned earlier to either the bridging structure Fea33+–N3–CuB2+ (33, 35, 36) or the azide anion attached to the protein (34). The mode at 2040 cm−1 has been attributed to either CuB2+–N3 coordination (34) or azide bound to ferric iron of heme a (33) or to a Fea33+–N3 structure with no coordination to CuB (35) or a second bridging conformation of Fea33+–N3–CuB2+ (36). When azide is removed from this sample by gel filtration, there are no longer bands due to azide in FTIR spectrum and the optical spectrum is identical to that of original, oxidized enzyme. A small shoulder visible at ∼2060 cm−1 might originate from binding of azide to some other metal ions such as inorganic ferric iron or cupric copper present in small quantities in the purified enzyme.

FIGURE 2.

FTIR spectra of free azide and in complex with cytochrome oxidase. pH 4.1, the spectrum of 1 m NaN3 in water at pH 4.1. The spectrum has been displaced along the vertical axis. pH 7.8, the spectrum of CcO with one equivalent of NaN3 (800 μm CcO + 800 μm NaN3) at pH 7.8.

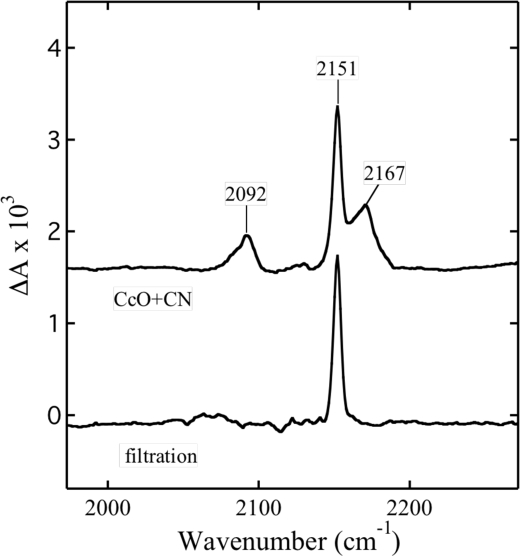

The FTIR spectrum of CcO with bound cyanide displays frequencies of the ligand at 2167, 2151, and 2092 cm−1 (Fig. 3). In this spectrum, the band at 2092 cm−1 is due to free HCN (33, 37), whereas the absorbance at 2151 cm−1 has been attributed to either the bridging mode Fea33+–CN–CuB2+ (33, 38, 39) or CuB2+–CN (37). The intensity of the stretch at 2167 cm−1 displayed some variability with the enzyme preparation (37) and was ascribed to a free copper-cyano complex (39).

FIGURE 3.

FTIR spectra of cytochrome oxidase complexed with cyanide. CcO+CN, the spectrum of 700 μm CcO with 1 mm NaCN in a Hepes buffer at pH 7.8. The spectrum has been displaced along the vertical axis. filtration, the spectrum of the complex of CcO with cyanide after gel filtration.

The complex of CcO with cyanide exhibits behavior opposite to that of azide. This difference in behavior is observed when the cyanide complex is subjected to gel filtration. After filtration, CcO still displays the maximum of the Soret band at 428 nm and a single FTIR mode at 2151 cm−1 (Fig. 3). Both spectra demonstrate that the cyanide remains complexed with the enzyme. Moreover, the gel filtration displaces the cyanide from the site characterized by the frequency of 2167 cm−1 and also removes that of free cyanide.

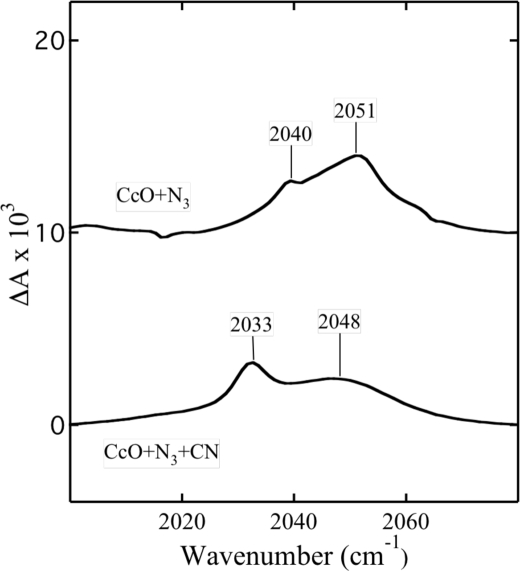

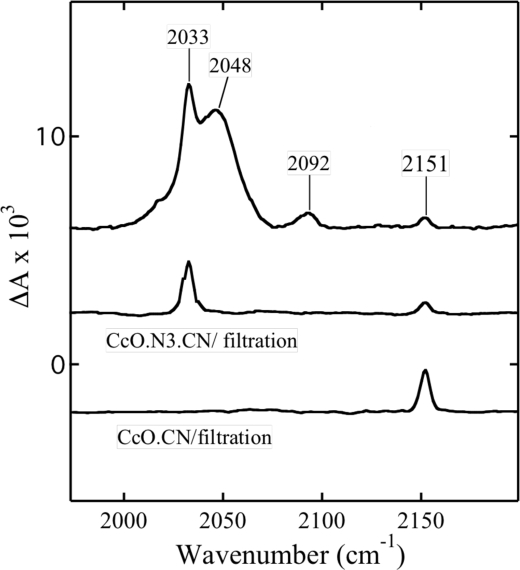

A different situation is observed when both azide and cyanide are reacted with cytochrome oxidase. When the enzyme is preincubated with an approximately stoichiometric amount of azide, there are two major bands observed in the FTIR spectrum as described above (Fig. 4). The addition of 1 mm cyanide to this sample rapidly shifts the maximum of the Soret band to 428 nm. This optical change is associated with the development of new modes at 2048 and 2033 cm−1 in the FTIR spectrum. The stretch at 2048 cm−1 is due to free N3− in solution (33, 34), resulting possibly from the displacement of bound azide to a protein site by cyanide. The azide mode at 2033 cm−1, assigned to the ternary complex of Fea33+–N3 CuB2+–CN (35), resists displacement by cyanide on the time scale of hours. Eventually this displacement takes place with the development of the FTIR absorbance at 2151 cm−1 due to the bridging cyanide (33, 35).

FIGURE 4.

FTIR spectra of the complex of cytochrome oxidase with azide in the presence and absence of cyanide. CcO+N3, the spectrum of 800 μm CcO in the presence of 700 μm NaN3 at pH 7.8. CcO+N3+CN, the spectrum of the same sample of CcO after reaction with 1 mm NaCN.

In this last sample, the position of the Soret band at 428 nm shows that all of Fea33+ is in the low spin state and implies that any azide at the catalytic site has been completely replaced by cyanide. However, this conclusion is not supported by the FTIR spectrum (Fig. 5) that still exhibits bands at 2033 and 2151 cm−1 due to bound azide and cyanide, respectively (Fig. 5, top spectrum). An additional mode at 2048 cm−1 belongs to free azide, whereas that at 2092 cm−1 belongs to free HCN. A striking feature of this spectrum is that the intensity of the cyanide band at 2151 cm−1 is much smaller than the same band in CcO reacted exclusively with cyanide (Fig. 5, bottom). This suggests that only a portion of the low spin Fea33+ is produced by the direct coordination of cyanide to heme a3 (e.g. Fea33+–CN–CuB2+). The remaining population has to result from the bound azide responsible for the stretch at 2033 cm−1 and attributed earlier to the Fea33+–N3 CuB2+–CN structure (35).

FIGURE 5.

FTIR spectra of cytochrome oxidase in the presence of both azide and cyanide and after gel filtration. Top, the spectrum of 800 μm CcO in the presence of both 800 μm NaN3 and 1 mm NaCN at pH 7.8. CcO.N3.CN/filtration, the spectrum of the same sample of CcO after filtration. CcO.CN/filtration, the spectrum of the complex of CcO with cyanide after gel filtration.

Remarkably, this putative ternary complex is unusually stable and is observed even after the sample was passed through column of Sephadex G25 (Fig. 5, middle). As expected, free azide and cyanide were removed, and only the modes of both bound ligands are detected. In addition, the maximum of the Soret band of this gel-filtered sample remains at 428 nm (not shown).

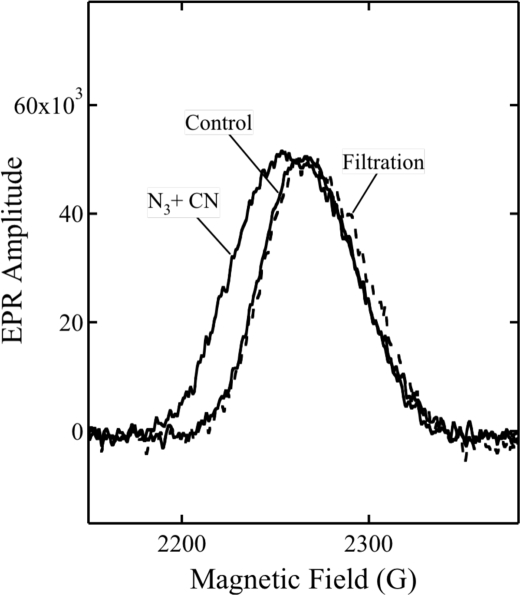

We previously showed that both azide and cyanide can be bound to a specific protein site distinct from the catalytic center (31). Ligation to these sites is demonstrated by small but reproducible modifications of the EPR spectrum of Fea3+ in oxidized enzyme. The g = 3 EPR signals of low spin Fea3+ of untreated oxidized enzyme (Control), in the presence of both azide and cyanide (N3 + CN) and after gel filtration, are shown in Fig. 6. The low field shift of the g = 3 signal is only detectable when both ligands are present in the solution. After filtration, the absorption-like peak returns to nearly the same position observed in the untreated enzyme, showing that both ligands are displaced from the protein sites by gel filtration.

FIGURE 6.

Dependence of the g = 3 EPR signal of oxidized heme a on the presence of azide and cyanide. Control, the control spectrum of 25 μm oxidized CcO at pH 7.8. N3+CN, in the presence of both 500 μm NaN3 and 5 mm NaCN. Filtration, the spectrum after filtration. For the conditions of measurements, see “Experimental Procedures.”

DISCUSSION

Both azide and cyanide are strong inhibitors of the activity of respiratory oxidases. To inhibit the enzyme, it is sufficient that one ligand is bound at the binuclear center composed of heme a3 and CuB. However, past studies indicated that the catalytic site has an ability to bind two external ligands simultaneously. The capacity of the Fea3–CuB center to form these ternary complexes was documented for azide plus nitric oxide (40, 41), two NO molecules (42, 43), chloride plus NO (42), two sulfide ions (32), and cyanide plus NO (44).

We previously demonstrated the presence of two additional specific binding sites for azide and cyanide in the proximity of heme a in the oxidized bovine enzyme (31). Interaction of ligands with these sites does not change the optical spectrum of the enzyme but changes the EPR spectrum of Fea3+ (Fig. 6). Based on structural and spectroscopic data, we attributed one site to the Asn-422/Tyr-379 duo and the second to the Mg2+ ion (29). As both ligands are removed from these additional sites by filtration (Fig. 6) (31), we consider the binuclear heme a3–CuB as the most likely center where both azide and cyanide are trapped.

The suggestion that the catalytic center is the target site is corroborated by comparison of our optical and FTIR spectra of ligand complexes with the published structural data. Because cyanide was determined in the x-ray structure of oxidized bovine CcO to be located between Fea3 and CuB (45), we conclude that the Soret band at 428 nm and the stretching frequency at 2151 cm−1 (Fig. 3) reflect the bridging mode of binding (Fea33+–CN–CuB2+). Cyanide at this binuclear center is bound so strongly that even gel filtration does not lead to the release of this ligand (Fig. 3).

The addition of cyanide to the preformed azide complex, prepared at low azide concentrations, triggers a rapid shift of the maximum of the Soret band from 424 to 428 nm (Fig. 1B). This shift reflects a transition of Fea33+ from the high spin to the low spin state, and it would seem that the presence of azide is responsible for an acceleration of binding of cyanide to heme a3 (28).

Consequently, to explain the stimulating effect of azide, it was proposed that azide interacts with some remote high affinity binding site. Presumably the interaction of azide with this protein site should “open up” the catalytic center (28). If this azide-binding site were the catalytic center, then access of the cyanide to Fea33+ is expected to be impaired.

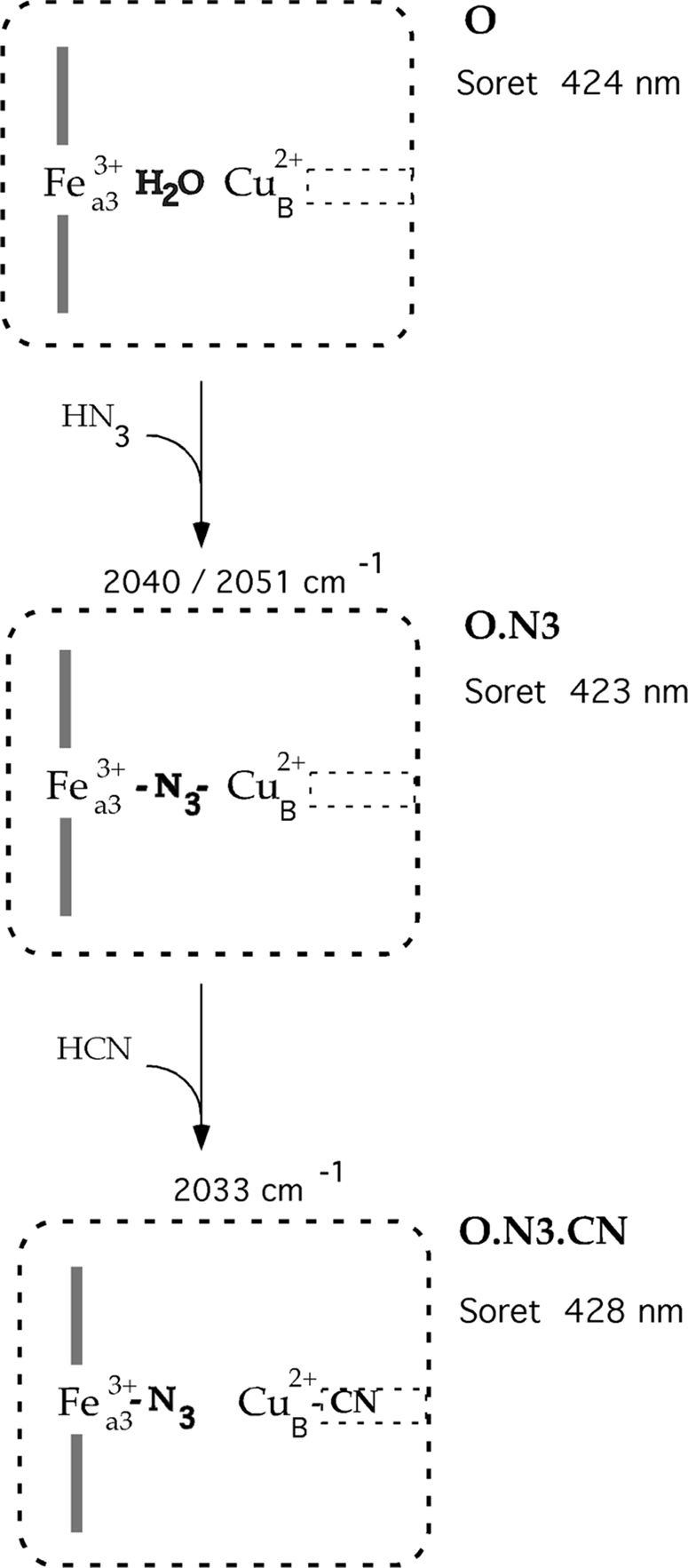

However, FTIR spectra show that despite the rapid and full conversion of Fea33+ to the low spin state, there is only a fraction of enzyme molecules displaying cyanide in the bridging position and interacting directly with iron (Fea33+–CN–CuB2+) (Fig. 5). In most of the population, azide is still bound to oxidase, but its stretching frequency has shifted to 2033 cm−1 (Figs. 4 and 5). This discrepancy, having the whole population of Fea33+ in the low spin state but only a fraction in which cyanide interacts directly with heme iron, can be reconciled by assuming that cyanide binding to CuB triggers a change in the mode of azide binding in the preformed Fea33+–N3–CuB2+ complex (33, 35). The coordination of cyanide to CuB weakens or breaks the bond between the terminal nitrogen of azide and CuB. This change increases the ligand field strength of azide with a consequent spin transition of the heme a3 iron that is detected as a shift of the Soret band and the appearance of the azide stretching frequency at 2033 cm−1. Thus the formation of the ternary complex of Fea33+–N3 CuB2+–CN is responsible for the observation of rapid optical changes. The azide in this ternary complex is eventually replaced by cyanide but on a substantially slower time scale (35). The correlation of the ligand coordination at the catalytic site with the optical and FTIR characteristics is shown schematically in Fig. 7.

FIGURE 7.

Schematic of the transitions at the catalytic site during the reaction of azide and cyanide with oxidized cytochrome oxidase. In the catalytic center of oxidized CcO (O), represented by the large box, water is assumed to be a bridging ligand between Fea33+ and CuB2+. The maximum of the Soret band at 424 nm reflects the high spin state of Fea33+. This catalytic site is only accessible to external ligands through a hydrophobic channel connecting CuB with the solvent. This channel is depicted as the small box on the right of CuB. Ligands in the neutral protonated form diffuse to the binuclear center (54), but they are bound as anions. Azide ion at low concentration displaces water between Fea3 and CuB. This substitution, however, does not change the spin state of Fea33+, and the alteration of the optical spectrum is negligible. Presumably this azide exhibits two modes of the binding indicated by two bands in the FTIR spectra, at 2040 and 2051 cm−1. (O.N3), the addition of cyanide to the preformed azide-oxidase adduct results in the rapid formation of the ternary complex (O.N3.CN). This formation is associated with the appearance of a new azide stretch at 2033 cm−1 and a red shift of the Soret maximum to 428 nm. The strong binding of cyanide to CuB blocks the channel that restricts a release of azide from the catalytic center.

Remarkably, the Fea33+–N3 CuB2+–CN complex is stable even after the free ligands are removed from solution (Fig. 5). This unexpected increase of the apparent stability of bound azide (Fig. 5) can be ascribed only to the simultaneous presence of cyanide. Clearly the stretch of azide at 2033 cm−1 indicates a new binding mode that could reflect an enhancement of the affinity of Fea3 for azide. However, previous studies of ligand interaction with CcO together with the consideration of the structural properties of the catalytic center suggest an alternative explanation.

The binuclear center is buried in the protein and only accessible to oxygen and small external ligands via channels (3). The channels, deduced from the structure of the oxidized enzyme, connect CuB with the surface of the protein (3). Apparently the strong ligation of cyanide to CuB blocks diffusion to the adjacent channels, and presumably this blockage is the main reason for the trapping of azide in CcO. The implied role of CuB in the gating of ligands between heme a3 and the solvent has already been documented for fully reduced enzyme (46–50). In the reduced enzyme, carbon monoxide release and binding to iron of heme a3 was associated with transient coordination to CuB. Moreover, CO release from the reduced catalytic center is dramatically diminished when cyanide is present in solution (51). Altogether our results as well as published data (46–51) suggest that CuB is an obligatory site for the exit and entry of ligands to both the oxidized and the reduced binuclear center. Apparently the nature and the strength of ligands bound to CuB control the connectivity of heme a3 with the solvent. This observation suggests that cycling of ligands at CuB could be a gating mechanism relevant for the formation and stabilization of intermediates during enzyme turnover.

Two additional points revealed by our observations deserve consideration. First, the FTIR spectrum of the Fea33+–N3 CuB2+–CN complex, without free ligands in solution, shows FTIR frequencies at 2033 and 2151 cm−1 (Fig. 5). The single band at 2151 cm−1 represents that fraction of enzyme in which cyanide has already reached the final bridging position (Fea33+–CN–CuB2+). The major species is, however, the ternary complex displaying the band at 2033 cm−1. However, in this structure, the infrared absorbance due to CuB2+–CN is not detectable in the FTIR spectra (Fig. 5). The puzzling absence of this CuB2+–CN infrared band has been already noted and rationalized as showing a weak absorbance coefficient of the complex (35). An alternative possibility is that the stretching frequencies of cyanide in CuB2+–CN and in the bridging structure are at 2151 cm−1.

Second, azide at higher concentrations displays an inhibitory effect on the reaction with cyanide (Fig. 1C). The opposite behavior of azide observed at low and high concentrations corresponds to the formation of two distinct complexes of oxidized CcO with this ligand (33, 52, 53). These two products are distinguished by UV-visible spectra and by different affinities for azide. The first complex is characterized by a high affinity (Kd ∼60 μm), and only slight changes of the optical spectrum are observed on azide binding. Azide in this complex is presumably coordinated between Fea3 and CuB (Fea33+–N3–CuB2+). The binding of the second azide to the low affinity site (Kd ∼ 20 mm) brings about spectral changes similar to those produced by cyanide. In this low affinity phase, the azide is supposedly bound to CuB, forming the ternary complex of Fea33+–N3 CuB2+–N3, and the formation of this complex is responsible for the onset of inhibition.

Acknowledgment

We thank Dr. J. S. Olson for the generous support during this investigation.

This work was supported, in whole or in part, by National Institutes of Health Grants GM 084348 (to M. F.), GM 35649 (to John S. Olson), and GM 080575 (to G. P.).

- CcO

- cytochrome c oxidase

- Fea3+

- oxidized iron of heme a

- Fea33+

- oxidized iron of heme a3

- CuB2+

- oxidized copper at the catalytic site

- FTIR

- Fourier-transform infrared spectroscopy

- DM

- n-dodecyl-β-d-maltoside.

REFERENCES

- 1.Wikstrom M. K. (1977) Nature 266, 271–273 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kadenbach B., Jarausch J., Hartmann R., Merle P. (1983) Anal. Biochem. 129, 517–521 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tsukihara T., Aoyama H., Yamashita E., Tomizaki T., Yamaguchi H., Shinzawa-Itoh K., Nakashima R., Yaono R., Yoshikawa S. (1996) Science 272, 1136–1144 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Day E. P., Peterson J., Sendova M. S., Schoonover J., Palmer G. (1993) Biochemistry 32, 7855–7860 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fann Y. C., Ahmed I., Blackburn N. J., Boswell J. S., Verkhovskaya M. L., Hoffman B. M., Wikström M. (1995) Biochemistry 34, 10245–10255 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tsukihara T., Aoyama H., Yamashita E., Tomizaki T., Yamaguchi H., Shinzawa-Itoh K., Nakashima R., Yaono R., Yoshikawa S. (1995) Science 269, 1069–1074 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Soulimane T., Buse G., Bourenkov G. P., Bartunik H. D., Huber R., Than M. E. (2000) EMBO J. 19, 1766–1776 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Svensson-Ek M., Abramson J., Larsson G., Törnroth S., Brzezinski P., Iwata S. (2002) J. Mol. Biol. 321, 329–339 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ostermeier C., Harrenga A., Ermler U., Michel H. (1997) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 94, 10547–10553 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Qin L., Hiser C., Mulichak A., Garavito R. M., Ferguson-Miller S. (2006) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 103, 16117–16122 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yoshikawa S., Shinzawa-Itoh K., Nakashima R., Yaono R., Yamashita E., Inoue N., Yao M., Fei M. J., Libeu C. P., Mizushima T., Yamaguchi H., Tomizaki T., Tsukihara T. (1998) Science 280, 1723–1729 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Riistama S., Puustinen A., García-Horsman A., Iwata S., Michel H., Wikström M. (1996) Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1275, 1–4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gennis R. B. (1998) Biochim. Biophys. Acta Bioenergetics 1365, 241–248 [Google Scholar]

- 14.Puustinen A., Wikström M. (1999) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 96, 35–37 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Florens L., Schmidt B., McCracken J., Ferguson-Miller S. (2001) Biochemistry 40, 7491–7497 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Schmidt B., McCracken J., Ferguson-Miller S. (2003) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 100, 15539–15542 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Michel H. (1998) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 95, 12819–12824 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Popović D. M., Stuchebrukhov A. A. (2004) FEBS Lett. 566, 126–130 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wikström M., Verkhovsky M. I. (2007) Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1767, 1200–1214 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Siegbahn P. E., Blomberg M. R. (2008) J. Phys. Chem. A 112, 12772–12780 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Brzezinski P., Gennis R. B. (2008) J. Bioenerg. Biomembr. 40, 521–531 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kaila V. R., Verkhovsky M. I., Hummer G., Wikström M. (2009) Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1787, 1205–1214 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tsukihara T., Shimokata K., Katayama Y., Shimada H., Muramoto K., Aoyama H., Mochizuki M., Shinzawa-Itoh K., Yamashita E., Yao M., Ishimura Y., Yoshikawa S. (2003) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 100, 15304–15309 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Papa S., Capitanio N., Capitanio G. (2004) Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1655, 353–364 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Muramoto K., Hirata K., Shinzawa-Itoh K., Yoko-o S., Yamashita E., Aoyama H., Tsukihara T., Yoshikawa S. (2007) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 104, 7881–7886 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kamiya K., Boero M., Tateno M., Shiraishi K., Oshiyama A. (2007) J. Am. Chem. Soc. 129, 9663–9673 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sharpe M. A., Ferguson-Miller S. (2008) J. Bioenerg. Biomembr. 40, 541–549 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.van Buuren K. J., Nicholis P., van Gelder B. F. (1972) Biochim. Biophys. Acta 256, 258–276 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Fei M. J., Yamashita E., Inoue N., Yao M., Yamaguchi H., Tsukihara T., Shinzawa-Itoh K., Nakashima R., Yoshikawa S. (2000) Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr 56, 529–535 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Soulimane T., Buse G. (1995) Eur. J. Biochem. 227, 588–595 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Fabian M., Jancura D., Palmer G. (2004) J. Biol. Chem. 279, 16170–16177 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Thomson A. J., Greenwood C., Gadsby P. M., Peterson J., Eglinton D. G., Hill B. C., Nicholls P. (1985) J. Inorg. Biochem. 23, 187–197 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Li W., Palmer G. (1993) Biochemistry 32, 1833–1843 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yoshikawa S., Caughey W. S. (1992) J. Biol. Chem. 267, 9757–9766 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tsubaki M. (1993) Biochemistry 32, 174–182 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Vamvouka M., Muller W., Ludwig B., Varotsis C. (1999) J. Phys. Chem. B 103, 3030–3034 [Google Scholar]

- 37.Yoshikawa S., Caughey W. S. (1990) J. Biol. Chem. 265, 7945–7958 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Tsubaki M. (1993) Biochemistry 32, 164–173 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tsubaki M., Mogi T., Hori H., Sato-Watanabe M., Anraku Y. (1996) J. Biol. Chem. 271, 4017–4022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Stevens T. H., Brudvig G. W., Bocian D. F., Chan S. I. (1979) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 76, 3320–3324 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Brudvig G. W., Stevens T. H., Chan S. I. (1980) Biochemistry 19, 5275–5285 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Butler C. S., Seward H. E., Greenwood C., Thomson A. J. (1997) Biochemistry 36, 16259–16266 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Pilet E., Nitschke W., Rappaport F., Soulimane T., Lambry J. C., Liebl U., Vos M. H. (2004) Biochemistry 43, 14118–14127 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hill B. C., Brittain T., Eglinton D. G., Gadsby P. M., Greenwood C., Nicholls P., Peterson J., Thomson A. J., Woon T. C. (1983) Biochem. J. 215, 57–66 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Mochizuki M., Tomita I., Muramoto K., Shinzawa-Itoh K., Yamashita E., Tsukihara T., Yoshikawa S. (2008) Biochim. Biophys. Acta Bioenergetics 1777, p S69 [Google Scholar]

- 46.Alben J. O., Moh P. P., Fiamingo F. G., Altschuld R. A. (1981) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 78, 234–237 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Dyer R. B., Einarsdottir O., Killough P. M., Lopezgarriga J. J., Woodruff W. H. (1989) J. Am. Chem. Soc. 111, 7657–7659 [Google Scholar]

- 48.Dyer R. B., Peterson K. A., Stoutland P. O., Woodruff W. H. (1991) J. Am. Chem. Soc. 113, 6276–6277 [Google Scholar]

- 49.Einarsdóttir O., Dyer R. B., Lemon D. D., Killough P. M., Hubig S. M., Atherton S. J., López-Garriga J. J., Palmer G., Woodruff W. H. (1993) Biochemistry 32, 12013–12024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Dyer R. B., Peterson K. A., Stoutland P. O., Woodruff W. H. (1994) Biochemistry 33, 500–507 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Hill B. C. (1994) FEBS Lett. 354, 284–288 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Wever R., Muijsers A. O., van Gelder B. F., Bakker E. P., van Buuren K. J. (1973) Biochim. Biophys. Acta 325, 1–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Vygodina T. V., Konstantinov A. A. (1985) Biochemistry (Mosc.) 2, 861–870 [Google Scholar]

- 54.Mitchell R., Rich P. R. (1994) Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1186, 19–26 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]