Abstract

The reduced folate carrier (RFC) is the major transport system for folates in mammals. We previously demonstrated the existence of human RFC (hRFC) homo-oligomers and established the importance of these higher order structures to intracellular trafficking and carrier function. In this report, we examined the operational significance of hRFC oligomerization and the minimal functional unit for transport. In negative dominance experiments, multimeric transporters composed of different ratios of active (either wild type (WT) or cysteine-less (CLFL)) and inactive (either inherently inactive (Y281L and R373A) due to mutation, or resulting from inactivation of the Y126C mutant by (2-sulfonatoethyl) methanethiosulfonate (MTSES)) hRFC monomers were expressed in hRFC-null HeLa (R5) cells, and residual WT or CLFL activity was measured. In either case, residual transport activity with increasing levels of inactive mutant correlated linearly with the fraction of WT or CLFL hRFC in plasma membranes. When active covalent hRFC dimers, generated by fusing CLFL and Y126C monomers, were expressed in R5 cells and treated with MTSES, transport activity of the CLFL-CLFL dimer was unaffected, whereas Y126C-Y126C was potently (64%) inhibited; heterodimeric CLFL-Y126C and Y126C-CLFL were only partly (27 and 23%, respectively) inhibited by MTSES. In contrast to Y126C-Y126C, trans-stimulation of methotrexate uptake by intracellular folates for Y126C-CLFL and CLFL-Y126C was nominally affected by MTSES. Collectively, these results strongly support the notion that each hRFC monomer comprises a single translocation pathway for anionic folate substrates and functions independently of other monomers (i.e. despite an oligomeric structure, hRFC functions as a monomer).

Keywords: Epitope Mapping, Folate, Plasma Membrane, Protein Structure, Transport Drugs, Antifolate, Folate, Oligomer, Reduced Folate Carrier, Transport

Introduction

Folates are members of the B class of vitamins that are required for the synthesis of nucleotide precursors, serine, and methionine in one-carbon transfer reactions (1). Folates are hydrophilic anionic molecules that do not cross biological membranes by diffusion alone, so it is not surprising that sophisticated membrane transport systems have evolved to facilitate folate accumulation by mammalian cells. Transporter-mediated internalization of folates is required for cellular macromolecule biosynthesis, since mammals cannot synthesize folates de novo (2, 3).

The ubiquitously expressed reduced folate carrier (RFC)2 is widely considered to be the major transport system for folate cofactors in mammalian cells and tissues (3, 4). RFC achieves uphill transport of folates into cells via a mechanism involving exchange of intracellular organic phosphates for extracellular folates (5). RFC serves a generalized role in folate transport and provides specialized tissue functions (3, 4). Further, losses of RFC expression and consequently function may contribute to physiological and developmental problems related to folate deficiency (6). In addition to its physiological role, RFC is pharmacologically significant because it can transport antifolate drugs, such as methotrexate (Mtx), pemetrexed, and raltitrexed used for cancer (4). Loss of RFC expression or synthesis of mutant RFC proteins in tumor cells leads to incomplete inhibition of intracellular enzyme targets and low levels of antifolate substrate for polyglutamate synthesis, resulting in drug resistance (4, 7).

Since its cloning in the mid 1990s, RFC structure and function have been studied extensively (4, 8). Using state-of-the-art molecular biology and biochemistry methods for characterizing polytopic membrane proteins, a detailed picture of the molecular structure of human RFC (hRFC) has emerged, including its membrane topology, N-glycosylation, functionally or structurally important domains and amino acids, and packing of α-helix transmembrane domains (4, 8). To test hypotheses related to structure and mechanism, a three-dimensional homology model for the 591-amino acid hRFC polypeptide was generated, based on solved structures for the bacterial lactose/proton symporter LacY and glycerol 3-phosphate/inorganic phosphate antiporter GlpT as well as biochemical data for hRFC (8, 9).

There is growing evidence that quaternary structure involving higher order oligomers is an essential feature of the structure and function of membrane transporters (10, 11). Many secondary transporters exist as higher order oligomers (e.g. dimers (NhaA and LacS) or trimers (AcrB, Glt, BetP, and CaiT)), although unambiguous evidence for monomer structures (LacY and GlpT) was also reported (10, 11). Outside of its importance for quality control in the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) and intracellular trafficking (12), in only a few cases have clear functional or regulatory roles for transporter oligomerization been established. For instance, it was shown for the Streptococcus thermophilus lactose transporter LacS that individual monomers cooperate with each other during the transport cycle, implying that oligomerization is essential for transport function (13). For the homodimeric NhaA Na+/H+ antiporter from Escherichia coli, monomers are fully functional, yet the dimer appears to be beneficial under extreme stress conditions at alkaline pH in the presence of Na+ or Li+ (14).

Our recent study presented compelling evidence that hRFC exists as a homo-oligomer (15). (i) hRFC was cross-linked with homobifunctional cross-linkers to form higher order complexes with molecular masses approximating those of dimers, trimers, and tetramers. (ii) When co-expressed in hRFC-null HeLa (R5) cells, hRFC proteins with different epitope tags (Myc and hemagglutinin (HA)) co-immunoprecipitated with epitope-specific antibodies. (iii) By biotinylation of surface hRFC proteins, oligomers were localized to the cell surface. (iv) Direct evidence of co-folding hRFC monomers and intracellular trafficking of oligomeric hRFC from the ER involved dominant-negative effects of mutant hRFCs (i.e. S138C) on surface expression and transport activity of wild type (WT) hRFC. (v) For another inactive mutant (R373A) with high level surface expression, co-expression at equal levels with WT hRFC resulted in co-association and some loss of transport activity compared with WT hRFC alone, although this was not systematically studied.

Indeed, it is not yet established whether the association of hRFC monomers to form oligomers is obligatory to function (i.e. whether individual monomers are themselves functional or the activity of associated monomers is somehow functionally “coupled,” resulting in net concentrative uptake of folate substrates). Clearly, structural and functional characterization of oligomeric hRFC is essential, given its potential importance to understanding the molecular mechanism of folate transport.

In this report, we use established complementary approaches to examine the operational significance of hRFC oligomerization and to determine the “minimal functional unit” for (anti)folate membrane transport. These include “negative dominance” experiments (10, 13, 16–18) involving functional studies on hRFC multimeric transporters composed of co-expressed active (either WT or cysteine-less full-length (CLFL)) and inactive (either inherently inactive due to mutation (Y281L and R373A) or resulting from inactivation of a Cys insertion mutant (Y126C) by (2-sulfonatoethyl) methanethiosulfonate (MTSES)) hRFC monomers; and expression of dimeric concatameric hRFC constructs (19, 20), generated by fusing CLFL and Y126C mutant hRFCs, followed by functional studies after MTSES treatment. Our results demonstrate that despite their co-association in forming oligomers, hRFC monomers are not only capable of mediating cellular uptake of folate substrates but indeed comprise the operational minimal functional unit for membrane transport by this system.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Reagents

[3′,5′,7-3H]Mtx (20 Ci/mmol) was purchased from Moravek Biochemicals (Brea, CA). Unlabeled Mtx and (6R,S)5-formyl tetrahydrofolate (leucovorin) were provided by the Drug Development Branch, NCI, National Institutes of Health (Bethesda, MD). Both labeled and unlabeled Mtx were purified by high pressure liquid chromatography prior to use (21). Synthetic oligonucleotides were obtained from Invitrogen. Tissue culture reagents and supplies were purchased from assorted vendors with the exception of fetal bovine serum, which was purchased from Hyclone Technologies (Logan, UT).

Generation of CLFL hRFC and Mutant Constructs

CLFL hRFC was generated from Myc-His10-tagged full-length hRFC in pCDNA3.1 (15) by subcloning and site-directed mutagenesis with the QuikChangeTM kit (Agilent Technologies, La Jolla, CA). The first seven cysteines (Cys-30, -33, -220, -246, -365, -396, and -458) were mutated to serines by substituting a fragment (nucleotides 1–1611) from our previous Cys-less hRFC construct, which was truncated at amino acid 538 (22), using XhoI/SfiI digestions (New England Biolabs, Ipswich, MA). The remaining four cysteines (Cys-546, -549, -563, and -580) were individually changed to serines by site-directed mutagenesis. To generate HA-tagged CLFL hRFC, a DNA fragment encoding the HA epitope following the stop codon was inserted after Gln-586 of CLFL hRFC, as previously described for HA-tagged full-length WT hRFC (23). QuikChangeTM mutagenesis was also used with HA-tagged full-length WT hRFC template (23) to generate the HA-tagged Y281L hRFC and R373A hRFC (15). This approach was likewise used to generate Y126C in the Cys-less background from CLFL hRFC (Myc-His10) as template.

hRFC concatameric constructs composed of covalently fused hRFC monomers were prepared by site-directed mutagenesis and subcloning. First, a ClaI site was introduced by site-directed mutagenesis into both CLFL hRFC (Myc-His10) and Y126C hRFC (Myc-His10) in the 5′-untranslated region (UTR) at position −56 preceding the ATG start codon to generate 5C-CLFL hRFC and 5C-Y126C hRFC, respectively. A BamHI site was then introduced by the same strategy into 5C-CLFL hRFC and 5C-Y126C hRFC between the ClaI site and the ATG start codon at position −28 to generate 5C5B-CLFL hRFC and 5C5B-Y126C hRFC, respectively. Finally, an existing BamHI site located just after the stop codon in both 5C5B-CLFL hRFC and 5C5B-Y126C hRFC was removed (while preserving the hRFC cDNA reading frame) to generate 5C5B-CLFL-3Bdel hRFC and 5C5B-Y126C-3Bdel hRFC, respectively. To prepare the hRFC homoconcatamer CLFL-CLFL, 5C-CLFL hRFC was digested with ClaI/BamHI and inserted into 5C5B-CLFL-3Bdel, also digested with ClaI/BamHI (New England Biolabs). The hRFC homoconcatamer Y126C-Y126C was generated from 5C-Y126C and 5C5B-Y126C-3Bdel using the same strategy as for the CLFL-CLFL construct. To prepare the heteroconcatamer of CLFL hRFC and Y126C hRFC, CLFL-Y126C, 5C-CLFL was digested with ClaI/BamHI and inserted into 5C5B-Y126C-3Bdel digested with ClaI/BamHI. For Y126C-CLFL, the analogous approach involving insertion of ClaI/BamHI-digested 5C-Y126C into 5C5B-CLFL-3Bdel was used. All concatameric constructs were designed to include the linker, GSSGAARGLSR, between two hRFC monomeric fragments to provide distance and flexibility. The Myc-His10 was preserved on the downstream monomeric fragment.

For all mutagenesis, mutation primers were designed by the Stratagene Web site. Sequences for the mutation primers are available upon request. All of the mutations were confirmed by automated DNA sequencing at Genewiz, Inc. (South Plainfield, NJ).

Cell Culture

hRFC-null Mtx-resistant HeLa cells, designated R5 (24), were a gift of Dr. I. David Goldman (Bronx, NY). R5 cells were maintained as described previously (25). hRFC constructs (see above) were transfected into R5 cells with Lipofectamine and Plus reagents (Invitrogen) (25). With all transfections, the cells were harvested after 48 h for preparation of plasma membranes and Western blotting (see below). For transport assays (below), cultures were split 24 h after transfection and assayed after an additional 24 h.

Membrane Transport Experiments

Cellular uptake of [3H]Mtx (0.5 μm) was measured over 2 min at 37 °C in 60-mm dishes in Hepes-sucrose-Mg2+ buffer (20 mm Hepes, 235 mm sucrose, pH adjusted to 7.3 with MgO) (HSM) (25). The levels of intracellular radioactivity were expressed as pmol/mg protein, calculated from direct measurements of radioactivity and protein contents (26) of the cell homogenates. For experiments involving MTSES treatments, cells were incubated in Dulbecco's phosphate-buffered saline (DPBS) with 10 mm MTSES for 15 min at 37 °C, after which cells were washed once with DPBS containing 14 mm β-mercaptoethanol. Following additional washes with DPBS and HSM, cells were assayed for transport. For trans-stimulation experiments, cells were preincubated with 500 μm leucovorin for 15 min at 37 °C in DPBS, after which cells were washed with ice-cold DPBS (twice), and HSM (once). For transport assays, the cells were warmed briefly to 37 °C, and uptake was initiated by the addition of HSM containing [3H]Mtx (0.5 μm).

Membrane Preparations, SDS-PAGE, and Western Blot Analysis

Plasma membrane preparation, SDS-PAGE, and electrotransfer to polyvinylidene difluoride membranes (Thermo Scientific, Rockford, IL) were performed exactly as reported previously (25). The Cell Surface Labeling Accessory Pack (Thermo Scientific) with sulfo-N-hydroxysuccinimide-SS-biotin (sulfo-NHS-SS-biotin) was used to biotinylate and isolate surface proteins (15). The biotinylated surface proteins were isolated with immobilized NeutrAvidinTM and eluted with 10 mm Tris-Cl (pH 7.5), containing 0.5% SDS, 50 mm dithiothreitol, and protease inhibitor mixture. For deglycosylation, 50 mm sodium phosphate (pH 7.5), 1% Nonidet P-40, and N-glycosidase F (1000 units; New England Biolabs) were added, and the reaction was incubated overnight at 37 °C. Detection and quantitation of immunoreactive proteins were with commercial anti-Myc or anti-HA antibodies (Covance, Emeryville, CA) or anti-hRFC antibody (27), with IRDye800-conjugated secondary antibody (Rockland, Gilbertsville, PA), using an Odyssey® infrared imaging system (LI-COR, Lincoln, NE). Densitometry was performed with the Odyssey software (version 3.0).

In Vitro Co-expression of WT/CLFL and Mutant hRFC Constructs

To systematically determine the impact of co-expressing inactive mutant hRFC proteins (either inherently inactive due to mutation (Y281L or R373A) or resulting from inactivation of a Cys insertion mutant (Y126C) by treatment with MTSES) with active (either WT or CLFL) hRFC on Mtx transport activity, plasmid encoding WT hRFC (which includes a C-terminal Myc-His10 epitope) was co-transfected with plasmids encoding the inactive R373A or Y281L hRFC mutants (both mutants include a C-terminal HA tag), or plasmid encoding CLFL hRFC (which includes a C-terminal HA tag) was co-transfected with plasmid encoding Y126C hRFC (which includes a C-terminal Myc-His10 epitope). All transfections used R5 HeLa cells as the recipients. Ratios of WT/CLFL to mutant plasmids (∼0:100, 20:80, 40:60, 60:40, 80:20, and 100:0) were varied while maintaining constant total hRFC plasmid. After 48 h, hRFC transport activity was assessed by measuring influx of [3H]Mtx, whereas sulfo-NHS-SS-biotin-labeled hRFC cell surface proteins were isolated on immobilized avidin (above), eluted, and analyzed by SDS-PAGE and Western blots following deglycosylation with N-glycosidase F. Both WT/CLFL and mutant proteins showed sharp banding on Western blots following deglycosylation, such that mutant and WT/CLFL proteins (molecular masses differed by ∼3.2 kDa) could be separated, thus permitting quantification on Western blots with hRFC antibody (27).

Residual transport activity of hRFC was plotted against the fraction of WT/CLFL hRFC to total hRFC. If the minimal functional unit is a monomer, transport activity should closely reflect the amount of WT/CLFL hRFC and increase linearly with increasing ratios of active WT/CLFL to total (inactive mutant plus WT/CLFL) surface hRFC (13, 16–18). However, if dimers or higher oligomers are the minimal functional units, only homo-oligomers of WT or CLFL hRFC should be fully active. Accordingly, total activity should increase quadratically with increasing active species according to the equation, ratemeasured = ƒn × (rateWT/CLFL), where ƒ is the fraction of WT or CLFL to total hRFC forms (active plus inactive), rateWT/CLFL is the transport rate for 100% WT hRFC or CLFL hRFC, as appropriate, ratemeasured is the experimentally measured rate for the mixture, and n is the subunit stoichiometry (2 for dimer, 3 for trimer, etc.) (13, 16–18).

Co-immunoprecipitation

Co-immunoprecipitations of Myc- and HA-tagged hRFCs were performed, as described previously (25), using mouse anti-Myc monoclonal antibody (Covance) and mouse IgG as a control. Additional controls included monomeric Myc- and HA-tagged constructs expressed individually and immunoprecipitated with HA and Myc antibodies, respectively. These were described in our previous report (15). The samples were eluted with 3× SDS-PAGE sample buffer (28) and fractionated on a 7.5% polyacrylamide gel in the presence of SDS for Western blotting.

Confocal Microscopy

For confocal microscopy, R5 cells were plated and transfected in Lab-Tek®II chamber slidesTM (Nalge Nunc International, Naperville, IL), as described previously (15). The primary antibody used was mouse anti-Myc (Covance), and the fluorescent secondary antibody was Alexa Fluor® 488 goat anti-mouse IgG (H + L) (Molecular Probes, Inc., Eugene, OR). The slides were visualized with a Zeiss laser-scanning microscope model 510 and a ×63 water immersion lens, using the same parameter setting for all samples. Confocal analysis was performed at the Imaging Core of the Karmanos Cancer Institute.

RESULTS

Negative Dominance Analysis of the hRFC Minimal Functional Unit by Co-expression of WT and Inactive Mutant hRFC Monomers

Whether monomeric or oligomeric structures represent the minimal functional units for membrane transport by secondary transporters can be deduced by measuring transport activities upon mixing active WT and inactive mutant monomeric proteins (13, 16–18). For oligomeric transporters, association of active and inactive monomers by co-expression or reconstitution can manifest as negative dominance and decrease transport activity to levels below WT levels if oligomerization is obligatory to function. Alternatively, WT monomers could conceivably complement inactive mutants, resulting in increased transport activities for the mutant hRFC. With inactivating mutants, the functional unit can be deduced from the extent of functional dominance over a range of levels of WT and mutant monomeric carriers, assuming that (i) a random binomial distribution of composite oligomers between WT and mutant monomers is generated and (ii) the presence of inactive monomer inactivates the oligomer. The analysis typically involves plotting relative transport rates versus the fractional composition of mutant or WT forms, such that linearity results if the monomers comprising the oligomers function independently. If negative dominant interactions occur between mutant and WT monomers in oligomeric hRFC, residual uptake would depend on the nth power of the fraction of WT carrier, where n is 2 for a dimer, 3 for a trimer, etc. (13, 16–18) (see “Materials and Methods”).

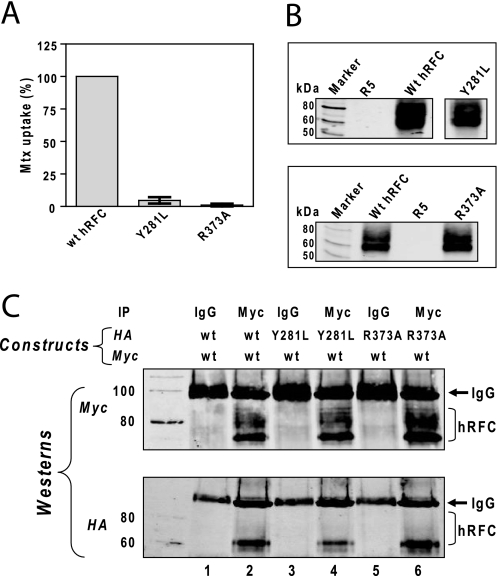

For this series of experiments with hRFC, we focused on the Y281L and R373A hRFC mutants. In initial experiments using HA-tagged constructs, Y281L and R373A hRFCs were expressed at levels approximating those for WT hRFC in transiently transfected hRFC-null R5 HeLa cells, accompanying nearly undetectable transport activity (<4% of WT levels; Fig. 1, A and B).

FIGURE 1.

Function and expression of inactive hRFC mutants and their association with WT hRFC. A and B, HA-tagged hRFC WT and its mutants (Y281L and R373A) were transiently transfected into HeLa R5 cells. A, cells were assayed for transport with [3H]Mtx (0.5 μm) over 2 min at 37 °C. Transport results are expressed as the averages ± ranges for two separate experiments. B, hRFC expression is shown on a Western blot of plasma membrane proteins (2.5 μg) from hRFC-null R5 cells, R5 transfectants expressing WT and Y281L hRFCs (top), and WT and R373A hRFCs (bottom). Detection of immunoreactive hRFC was with anti-HA primary antibody and IRDye800-conjugated secondary antibody and used an Odyssey® infrared imaging system. The molecular mass markers for SDS-PAGE (in kDa) are noted. C, Myc-tagged WT hRFC was co-expressed with HA-tagged WT, Y281L, or R373A hRFC in HeLa R5 cells. Plasma membranes were prepared, solubilized, and immunoprecipitated (IP) with Myc-specific antibody (lanes 2, 4, and 6) or with control IgG (lanes 1, 3, and 5). The samples were analyzed by SDS-PAGE and immunoblotted with Myc- and HA-specific antibodies. The molecular mass markers (in kDa) for SDS-PAGE are noted.

In co-expression experiments, HA-tagged Y281L and R373A hRFCs co-immunoprecipitated with Myc-His10-tagged WT carrier in both total plasma membranes (Fig. 1C, lanes 4 and 6, respectively) and in sulfo-NHS-SS-biotin-labeled surface fractions (not shown). HA-tagged WT and Myc-tagged WT hRFCs were co-immunoprecipitated as a positive control (Fig. 1C, lane 2), although no immunoreactive hRFC proteins (WT or mutant) were detected with Myc- or HA-specific antibodies for samples immunoprecipitated with mouse IgG in lieu of antibody (Fig. 1C, lanes 1, 3, and 5). Likewise, for HA-tagged protein expressed individually and immunoprecipitated with Myc antibody or for Myc-tagged hRFC expressed individually and immunoprecipitated with HA antibody, no immunoreactive hRFC proteins were detected (not shown) (see Ref. 15). Thus, our results establish the existence of hRFC oligomers between WT hRFC monomers and between WT and mutant monomers at the membrane surface.

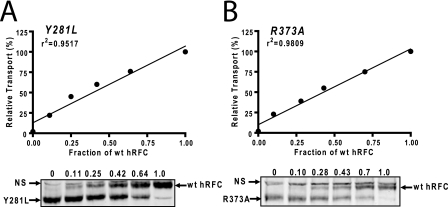

Because our previous report with R373A hRFC co-expressed with WT hRFC (15) raised the possibility of a functional negative dominance between inactive mutant and WT monomers, it was important to test this directly. To systematically determine the impact of inactive mutant hRFC proteins oligomerizing with WT hRFC on net Mtx transport activity, R5 cells were co-transfected with different ratios of inactive Y281L or R373A mutant to WT hRFC cDNAs, such that total hRFC was constant. Forty-eight hours post-transfection, hRFC transport activities were measured with [3H]Mtx (0.5 μm) over 2 min at 37 °C. Sulfo-NHS-SS-biotin-labeled hRFC surface proteins were isolated and analyzed by SDS-PAGE and Western blots following deglycosylation with N-glycosidase F (which permits resolution and quantitation of the WT and mutant forms) (Fig. 2, A and B, lower panels). When residual transport activity was plotted against the fraction of WT hRFC to total hRFC (Fig. 2, A and B, upper panels), [3H]Mtx uptake increased linearly as the WT fraction increased from 0 to 100% in the presence of either Y281L hRFC (Fig. 2A) or R373A hRFC (Fig. 2B). These data suggest that the minimal functional unit for hRFC is a monomer.

FIGURE 2.

Determination of the minimal functional unit of hRFC by co-expressing WT and inactive hRFC mutants. WT (Myc-tagged) and mutant (Y281L and R373A; HA-tagged) hRFC constructs were transiently transfected into HeLa R5 cells. The cells were assayed for transport with [3H]Mtx (0.5 μm) over 2 min at 37 °C. Surface hRFC proteins labeled with sulfo-NHS-SS-biotin were measured by SDS-PAGE and Western blotting with anti-hRFC antibody. Relative levels of WT and mutant hRFC proteins were measured by densitometry with Odyssey® software. The calculated fractions of WT hRFC to total hRFC protein from each sample are noted above each lane. The residual transport activities from representative experiments were plotted versus WT hRFC fractions from densitometry measurements, in the presence of Y281L (A) or R373A hRFCs (B). Correlation coefficients were calculated by Prism software (version 4.0). Results are shown for a representative experiment. In replicate experiments, transport activity and densitometry values did not vary more than 10%. NS, nonspecific. Detailed methods are described under “Materials and Methods.”

Negative Dominance Analysis of the Minimal Functional Unit by Co-expression of CLFL hRFC with Y126C Cys Insertion hRFC Mutant and Treatment with MTSES

Our previous characterization of active Cys-less and 282 Cys insertion hRFC mutants (9, 25) implied a related strategy for determining the minimal functional unit of oligomeric hRFC. This involves generation of hRFC oligomers composed of a Cys-less mutant and a Cys insertion mutant, followed by treatment with the thiol-reactive methanethiolsulfonate reagent MTSES. An analogous approach was used by Bamber et al. to study monomer interactions with the yeast mitochondrial ADP/ATP carrier (16). The assumption is that MTSES will potently inhibit the Cys mutant monomer without impacting the Cys-less form, thereby facilitating a negative dominance analysis analogous to that for the Y281L and R373A mutants co-expressed with WT hRFC. For these experiments, a previously truncated (538-amino acid) Cys-less hRFC template was extended to its complete 591-amino acid length (designated Cys-less full-length or CLFL). In the CLFL background, we prepared a Y126C mutant, previously reported as highly sensitive to MTSES treatment, resulting in profound irreversible loss of transport activity (9).

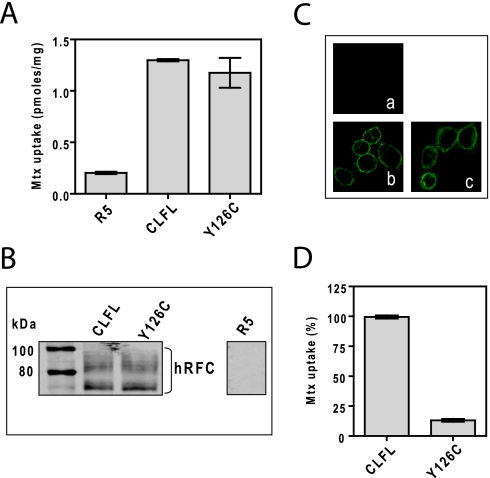

In initial experiments, CLFL and Y126C constructs were individually expressed in R5 HeLa cells as Myc-His10-tagged proteins and assayed for [3H]Mtx transport. For CLFL and Y126C, transport was virtually identical and was substantially (∼6-fold) increased over that in R5 cells (Fig. 3A). Activity approximated 40% of WT hRFC levels (supplemental Fig. 1S), accompanying a comparable decrease in the level of surface-targeted hRFCs on Western blots (Fig. 3B and supplemental Fig. 1S). Surface targeting was confirmed by indirect immunofluorescence staining/confocal microscopy (Fig. 3C). Upon treatment with MTSES (10 mm), [3H]Mtx uptake was unaffected for CLFL hRFC; however, transport by the Y126C mutant was potently inhibited (by ∼88%) (Fig. 3D).

FIGURE 3.

Characterization of CLFL hRFC and a single Cys insertion mutant, Y126C hRFC. Both Myc-tagged CLFL hRFC and Y126C hRFC constructs were transiently transfected into HeLa R5 cells. A, cells were assayed for transport with [3H]Mtx (0.5 μm) over 2 min at 37 °C. Transport results are expressed as the averages ± ranges for two separate experiments. B, hRFC expression is shown on a Western blot of plasma membrane proteins (5 μg) from hRFC-null R5 cells, and R5 transfectants expressing CLFL hRFC or Y126C hRFC. Detection of immunoreactive hRFC was with anti-Myc antibody and IRDye800-conjugated secondary antibody with an Odyssey® infrared imaging system. The molecular mass markers for SDS-PAGE (in kDa) are noted. C, confocal results are shown for hRFC-null R5 cells (a) and for R5 transfectants expressing CLFL hRFC (b) or Y126C hRFC (c). The cells were fixed with 3.3% paraformaldehyde, permeabilized with 0.1% Triton X-100, and stained with anti-Myc primary antibody and Alexa Fluor® 488-conjugated secondary antibody. The slides were visualized with a Zeiss laser-scanning microscope model 510 using a ×63 water immersion lens. D, R5 cells expressing CLFL hRFC and Y126C hRFC were preincubated with and without 10 mm MTSES for 15 min at 37 °C. Cells were washed, and [3H]Mtx (0.5 μm) uptake was assayed at 37 °C for 2 min. Uptake is presented as a percentage of the level measured in the absence of MTSES. All transport results are expressed as average values ± ranges for two separate experiments.

To verify co-association between CLFL and Y126C hRFC forms in oligomers, HA-tagged CLFL hRFC was co-expressed with the Myc-His10-tagged Y126C mutant in R5 cells. Plasma membranes from the R5 transfectants were prepared, solubilized, precleared, and immunoprecipitated with Myc antibody or normal IgG and protein G beads. Samples were eluted and analyzed on Western blots probed with Myc- and HA-specific antibodies. For samples treated with Myc antibody, both WT Myc- and HA-tagged hRFCs were immunoprecipitated (Fig. 4A, lane 2), as described above. Likewise, Myc-tagged Y126C and HA-tagged CLFL hRFC proteins were co-immunoprecipitated with Myc antibody (Fig. 4A, lane 4). No immunoreactive hRFC proteins were detected with Myc- or HA-specific antibodies for samples immunoprecipitated with mouse IgG (Fig. 4A, lanes 1 and 3). These results unambiguously establish that, analogous to the epitope-tagged WT hRFC proteins, CLFL and Y126C mutant hRFCs associate to form oligomers.

FIGURE 4.

Determination of the hRFC minimal functional unit by co-expressing CLFL and Y126C hRFC Cys insertion mutant. A, results of a co-immunoprecipitation (IP) of CLFL hRFC with Y126C hRFC are shown. HeLa R5 cells were cotransfected together with WT hRFC (Myc-tagged) and WT hRFC (HA-tagged) or with CLFL hRFC (HA-tagged) and Y126C hRFC (Myc-tagged). Plasma membranes were prepared, solubilized, and immunoprecipitated with Myc-specific antibody (lanes 2 and 4) or with control IgG (lanes 1 and 3). The samples were analyzed by SDS-PAGE and immunoblotted with Myc- and HA-specific antibodies. Molecular mass markers for SDS-PAGE (in kDa) are noted. B, both CLFL hRFC (HA-tagged) and Y126C hRFC (Myc-tagged) constructs were transiently transfected into HeLa R5 cells. The cells were assayed for transport with [3H]Mtx (0.5 μm) over 2 min at 37 °C. Surface hRFC proteins were biotinylated with sulfo-NHS-SS-biotin and were measured by SDS-PAGE/Western blotting with anti-hRFC antibody. Results are shown for levels of CLFL and Y126C hRFC proteins determined by densitometry, and the calculated fractions of CLFL hRFC to total hRFC proteins are noted above each lane. The residual transport activities after treatment with MTSES (10 mm) were plotted versus the fraction of CLFL hRFC measured by densitometry. Results are shown for a representative experiment. In replicate experiments, both transport activity and densitometry values did not vary more than 10%. The correlation coefficient was calculated by Prism software (version 4.0). Detailed methods are described under “Materials and Methods.”

For the negative dominance study, CLFL (HA-tagged) and Y126C (Myc-His10-tagged) hRFCs were co-expressed at defined molar ratios in R5 HeLa cells. Forty-eight hours post-transfection, cells were treated with and without MTSES. [3H]Mtx transport was measured and correlated with levels of cell surface CLFL and Y126C forms by sulfo-NHS-SS-biotin labeling, deglycosylation with N-glycosidase F, and SDS-PAGE/Western blots with hRFC antibody. The easily resolved CLFL and Y126C species were quantified by densitometry, and the results were plotted (as ratios of CLFL to total hRFC) versus residual transport activities following MTSES treatment.

These experiments were based on the concept that if transport by CLFL and Y126C hRFC oligomers involved functional interactions between the monomers, residual [3H]Mtx transport after treatment with MTSES would negatively deviate from linearity proportional to the nth power of the fraction of CLFL, analogous to the experiments with the Y281L and R373A mutants (16). However, if CLFL and Y126C monomers functioned independently, residual transport activity after MTSES treatment would correlate linearly with the fraction of CLFL (see “Materials and Methods”).

As shown in Fig. 4B, residual [3H]Mtx transport activity correlated linearly with the fraction of CLFL hRFC present in membranes. Thus, despite their physical association as hRFC oligomers, CLFL hRFC and Y126C hRFC appear to function as monomers.

Analysis of the hRFC Minimal Functional Unit by Expression of CLFL and Y126C hRFC Concatamers

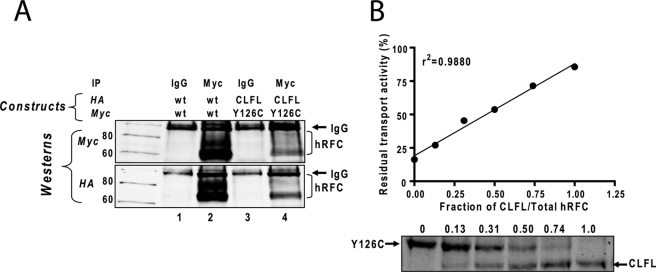

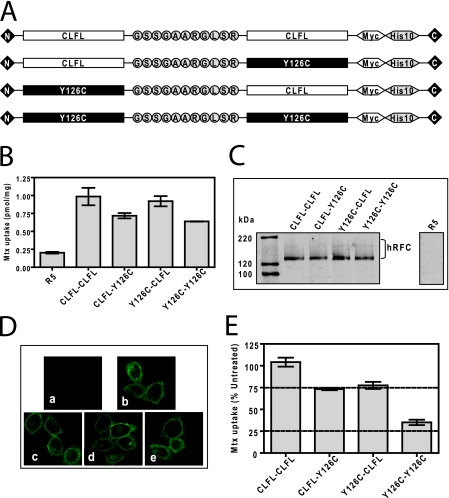

To extend our study of CLFL and Y126C hRFC oligomers, we generated “head-to-tail” hRFC concatamers by fusing the CLFL and Y126C hRFC monomeric proteins in tandem. All constructs were designed with an 11-amino acid peptide linker, GSSGAARGLSR, between the hRFC monomeric forms to confer flexibility between domains. The following constructs were prepared: CLFL-CLFL, CLFL-Y126C, Y126C-CLFL, and Y126C-Y126C (Fig. 5A). The concatamers were all tagged with C-terminal Myc-His10.

FIGURE 5.

Characterization of covalent dimeric hRFC concatamers and treatment with MTSES to identify functional interactions between hRFC monomers. HeLa R5 cells were transiently transfected with CLFL-CLFL, CLFL-Y126C, Y126C-CLFL, and Y126C-Y126C concatameric hRFCs. A, schematic representation of hRFC concatamers composed of covalently linked CLFL and Y126C monomers (tagged with a Myc-His10) is shown. B, cells were assayed for transport with [3H]Mtx (0.5 μm) over 2 min at 37 °C. Transport results are expressed as the averages ± ranges for two separate experiments. C, hRFC expression is shown on a Western blot of plasma membrane proteins (5 μg) from hRFC-null R5 cells and R5 transfectants expressing CLFL-CLFL, CLFL-Y126C, Y126C-CLFL, and Y126C-Y126C concatameric hRFCs. Detection of immunoreactive hRFCs was with anti-Myc antibody and IRDye800-conjugated secondary antibody with an Odyssey® infrared imaging system. The molecular mass markers for SDS-PAGE (in kDa) are noted. D, confocal results are shown for hRFC-null R5 cells (a), R5 transfectants expressing CLFL-CLFL (b), CLFL-Y126C (c), Y126C-CLFL (d), and Y126C-Y126C concatameric hRFCs (e). The cells were fixed with 3.3% paraformaldehyde, permeabilized with 0.1% Triton X-100, and stained with anti-Myc primary antibody and Alexa Fluor® 488-conjugated secondary antibody. The slides were visualized with a Zeiss laser-scanning microscope 510 using a ×63 water immersion lens. E, R5 cells expressing CLFL-CLFL, CLFL-Y126C, Y126C-CLFL, and Y126C-Y126C concatameric hRFCs were preincubated with and without 10 mm MTSES for 15 min at 37 °C. Cells were washed, and 0.5 μm [3H]Mtx uptake was assayed at 37 °C for 2 min. Uptake is presented as a percentage of the level measured in the absence of MTSES in excess of the residual transport in untransfected R5 cells (not shown). All transport results are expressed as average values ± ranges for two separate experiments. Details are provided under “Materials and Methods.”

The concatameric constructs were transiently transfected into R5 cells and assayed for [3H]Mtx transport and membrane expression on Western blots probed with anti-Myc antibody. All of the tandem hRFC proteins were active for transport (∼3–4-fold over R5 cells) (Fig. 5B) and migrated with an apparent molecular mass approximately double that for the corresponding hRFC monomeric forms (compare results in Fig. 5C with those in Fig. 3B). By indirect immunofluorescence staining and confocal microscopy, all of the hRFC concatameric proteins appeared to target the plasma membranes (Fig. 5D).

To assess possible functional interactions between covalently linked CLFL and Y126C hRFC monomers, we measured transport activity after treating the concatameric R5 transfectants with MTSES (10 mm) (Fig. 5E). As expected, MTSES had no effect on [3H]Mtx transport for the CLFL-CLFL covalent dimer. However, transport by Y126C-Y126C was inhibited ∼64%. For the mixed concatamers (CLFL-Y126C and Y126C-CLFL), inhibition by MTSES was only 27 and 23%, respectively. These results indicate that MTSES treatment of the CLFL-Y126C and Y126C-CLFL covalent dimers resulting in inhibition of the Y126C mutant monomer has insignificant impact on transport activity for the tethered CLFL in either the head or tail position.

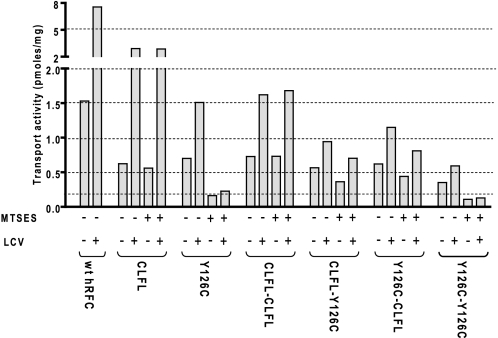

To further verify the functional independence of the individual CLFL and Y126C monomers, we measured trans-stimulation of [3H]Mtx uptake, following preloading of cells with leucovorin, mediated by covalently linked CLFL and Y126C concatamers, as a measure of bidirectional transport (29). For these experiments, R5 HeLa cells were transfected with WT, CLFL, or Y126C hRFC monomeric constructs or the CLFL/Y126C covalently linked dimers (Fig. 5A). Cells were treated with or without MTSES (10 mm), incubated for 15 min at 37 °C with or without 500 μm leucovorin, and then assayed for [3H]Mtx uptake. For each of the constructs without MTSES treatment, leucovorin preloading trans-stimulated [3H]Mtx uptake to various extents (∼45 to ∼500% over the corresponding cells without leucovorin preloading) (Fig. 6). MTSES treatment inhibited transport as in Fig. 5 and effectively abolished trans-stimulation for monomeric Y126C and dimeric Y126C-Y126C but not for monomeric CLFL or dimeric CLFL-CFLF. Although MTSES slightly (∼25–30%) inhibited transport for the CLFL-Y126C and Y126C-CLFL heteroconcatamers with and without leucovorin preloading, relative trans-stimulation (1.7–1.9-fold) was largely unaffected by MTSES treatment. This suggests that the covalently linked CLFL monomer was capable of bidirectional transport.

FIGURE 6.

Trans-stimulation of [3H]Mtx influx by leucovorin with monomeric and concatameric hRFCs. HeLa R5 cells were transiently transfected with WT, CLFL, Y126C, CLFL-CLFL, CLFL-Y126C, Y126C-CLFL, and Y126C-Y126C hRFCs. For MTSES-treated samples, transfected cells were pretreated with 10 mm MTSES for 15 min at 37 °C and then assayed for trans-stimulation. For trans-stimulation, the transfected cells were preincubated with or without 500 μm leucovorin (LCV) for 15 min at 37 °C, washed, and assayed for [3H]Mtx (0.5 μm) uptake. Details are provided under “Materials and Methods.” Uptake is presented as a percentage of the level measured in excess of the residual low transport in untransfected R5 cells. Data are from a single representative experiment performed twice with nearly identical results.

Collectively, these results strongly support the notion that each hRFC monomer comprises a single translocation pathway for anionic folates and functions largely independently of other monomers (i.e. despite its oligomeric structure, hRFC functions as a monomer).

DISCUSSION

The present study significantly expands upon our recent report that hRFC, the major folate membrane transporter in human cells and tissues, exists as a homo-oligomer (15). In our prior study, functional oligomeric WT hRFC was expressed at the cell surface of transfected R5 HeLa cells. When an inactive hRFC mutant (S138C) with impaired intracellular trafficking was co-expressed with WT hRFC, a dominant negative phenotype resulted with profoundly decreased WT hRFC surface expression due to defective intracellular trafficking and apparent retention in the ER (15). By contrast, another inactive hRFC mutant (R373A) was highly expressed in plasma membranes as an oligomer with WT carrier and appeared to suppress WT hRFC activity, albeit substantially less than for S138C. These results established that homo-oligomers composed of hRFC monomers are especially critical for cellular trafficking from the ER to plasma membranes and raised the possibility of a dominant negative effect of mutant hRFC on WT hRFC function, implying functional coupling between monomers. They also provided strong impetus for the functional characterization of oligomeric hRFC, as described herein. In this report, we used separate complementary approaches to characterize the minimal functional unit for hRFC (i.e. to establish whether individual hRFC monomers within the hRFC oligomer are themselves functional and/or if there was evidence of functional cooperativity between hRFC monomers).

We initially applied negative dominance strategies used by others for assessing functional interactions between monomers in secondary transporters (13, 16–18), involving mixtures of active and inactive monomeric carriers and characterizing levels of the individual monomeric forms and net transport activities of the mixtures. These methods require that the different mutant and WT monomers be expressed independently and that their levels are directly proportional to the amounts of plasmid DNAs used for transfections. Of course, these methods also assume the random formation of hetero-oligomers between WT and mutant subunits (13), which for a dimer would constitute at most 50% of the total forms (with 25% each for the homodimeric forms). Further, should negative dominance interactions between inactive and active monomers occur, a nearly complete suppression of transport should ensue. Although it is possible that dominant inhibitory effects of mutant monomers may be incomplete, any deviation from linearity in the graphic analysis provides strong evidence for functional interactions between monomers.

We co-expressed inactive hRFC mutants that efficiently targeted to the cell surface, including R373A (15) and Y281L with WT hRFC, and CLFL with a uniquely MTSES-sensitive Cys insertion mutant (Y126C) (9) in a CLFL background, followed by MTSES treatment. Although it is possible that there could conceivably be differential retention in the ER and/or preferential oligomerization involving WT or mutant monomers, resulting in a somewhat biased distribution of monomers comprising membrane oligomers, mutant and WT or CLFL monomers were co-immunoprecipitated at similar levels, suggesting otherwise. For both experimental designs, essentially identical results were obtained, such that residual transport in the presence of inactive mutant (R373A, Y281L) or following inhibition of Y126C with MTSES showed a linear correlation with the fraction of active hRFC (WT and CLFL, respectively). This strongly argues that WT and CLFL hRFCs can function independently of their oligomeric associations with the inactive monomers (e.g. R373A and Y126C, respectively). The apparent loss of WT transport activity in our prior study with co-expressed R373A and WT hRFCs, compared with WT hRFC alone (15), probably reflects the different experimental design and may result from slight variations in co-folding of mutant and WT monomers that manifest as a modest decrease in net transport activity rather than direct functional coupling between hRFC monomers.

An alternative experimental strategy that circumvents the requirement for random oligomerization involves expression of individual active and inactive monomers as covalent concatameric dimers, which increases the maximum percentage of heterodimers from 50 to 100%. This approach was first used with voltage-gated K+ channels (30) and has since been applied to other membrane proteins, including aquaporins (31), Na+,K+-ATPase (32), ligand-gated ion channels (33), lactose permease (34), NaPiIIa (35), KAAT1 (36), CAATCH1 (36), and LacS (20). With LacS, the use of covalent dimers of tandem fused active and inactive subunits, combined with LacS heterodimers of active and conditionally inactive monomers, implied a functional coupling in the proton motive force-driven uptake cycle, most likely via a conformational change associated with reorientation of the empty binding site (20).

For our study, we generated and expressed covalent head-to-tail dimers between CLFL and Y126C hRFC monomers in R5 HeLa cells. The covalent dimers targeted efficiently to plasma membranes as higher molecular mass species (approximately twice that for monomeric hRFCs), whereupon they were active for [3H]Mtx transport and were trans-stimulated following preloading with a high concentration of leucovorin, establishing bidirectional transport fluxes. For the Y126C-Y126C concatamer, treatment with MTSES resulted in an appreciable loss of transport activity and a nearly complete loss of trans-stimulation. The incomplete inhibition of transport activity (∼50% of the level for CLFL-CLFL hRFC) and nominal effect on trans-stimulation for the Y126C-CLFL and CLFL-Y126C heterodimers by MTSES provided further evidence that each hRFC monomer comprises a separate translocation pathway that functions independently of the functional status of the associated monomer(s).

Although our results establish the functional independence of the individual monomers comprising oligomeric hRFC, it remains an open question whether WT hRFC monomers may still require oligomerization to function, even if this involves their association with mutant inactive hRFC monomers. Unfortunately, this is not easily addressed in the absence of an approach for generating and validating mutant monomeric hRFC. Current studies are under way in this pursuit.

Finally, our results raise the intriguing question of what possible biological significance there is for a functional monomeric hRFC that assembles as oligomers independent of a direct mechanistic role in membrane translocation of folate substrates. Oligomerization can be envisaged to serve a regulatory role by influencing plasma membrane stabilities of transporters or by modulating protein/protein interactions in the plasma membrane (19, 37). Our previous results (15) imply that hRFC oligomerization can regulate hRFC trafficking from the ER to the cell surface. Thus, hRFC oligomerization may be important to antifolate resistance and impaired accumulation via effects on membrane trafficking/transporter stability. An interesting extension of this as a potential means of circumventing drug resistance involves treatments with small molecule ligands (e.g. folates) to promote co-folding and hRFC oligomer formation, which may result in increased surface targeting of both WT and mutant hRFCs. An analogous use of “pharmacologic chaperones” to promote surface trafficking of mutant proteins was described for other membrane proteins ranging from P-glycoprotein to cystic fibrosis transmembrane regulator and human ERG (38–40). For hRFC, such a mechanism may have broader regulatory significance as a means of acutely responding to levels of extracellular folate cofactors. Although no unique and unambiguous biological roles for the R27H substitution resulting from the G80A polymorphism in hRFC (4, 6) or N-terminally modified hRFC proteins (4) have been identified, the possibility that these primary sequence modifications may impact carrier function at the level of hRFC oligomerization is not unreasonable. Similarly, no obvious biological roles for naturally occurring modified hRFC transcripts (4, 6) and encoded proteins have been described, although one form (i.e. 988 bp deletion in exon 7) was reported to functionally modulate hRFC activity (41). By analogy, an alternatively spliced form of the oligomeric norepinephrine transporter with variations in the 3′-UTR was found to act as a dominant negative inhibitor, resulting in a reduction in the level of plasma membrane protein (42). Experiments are under way to explore these intriguing possibilities.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. I. David Goldman for the generous gift of hRFC-null R5 HeLa cells. The contributions of Dr. Yijun Deng in the initial experiments with the Y281L and R373A hRFC mutants are appreciated.

This work was supported, in whole or in part, by National Institutes of Health, NCI, Grant CA53535.

The on-line version of this article (available at http://www.jbc.org) contains supplemental Fig. 1S.

- RFC

- reduced folate carrier

- hRFC

- human RFC

- CLFL

- cysteine-less full-length

- DPBS

- Dulbecco's phosphate buffered saline

- ER

- endoplasmic reticulum

- HA

- hemagglutinin

- MTSES

- (2-sulfonatoethyl) methanethiosulfonate

- Mtx

- methotrexate

- sulfo-NHS-SS-biotin

- sulfo-N-hydroxysuccinimide-SS-biotin

- UTR

- untranslated region

- WT

- wild type

- leucovorin

- (6R,S)5-formyl tetrahydrofolate.

REFERENCES

- 1.Stokstad E. L. R. (1990) in Folic Acid Metabolism in Health and Disease (Picciano M. F., Stokstad E. L. R., Greogory J. F. ed) pp. 1–21, Wiley-Liss, New York [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sirotnak F. M., Tolner B. (1999) Annu. Rev. Nutr. 19, 91–122 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Matherly L. H., Goldman D. I. (2003) Vitam. Horm. 66, 403–456 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Matherly L. H., Hou Z., Deng Y. (2007) Cancer Metastasis Rev. 26, 111–128 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Goldman I. D. (1971) Ann. N.Y. Acad. Sci. 186, 400–422 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Matherly L. H. (2004) Curr. Pharmacogenetics 2, 287–298 [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zhao R., Goldman I. D. (2003) Oncogene 22, 7431–7457 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Matherly L. H., Hou Z. (2008) Vitam. Horm. 79, 145–184 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hou Z., Ye J., Haska C. L., Matherly L. H. (2006) J. Biol. Chem. 281, 33588–33596 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Veenhoff L. M., Heuberger E. H., Poolman B. (2002) Trends Biochem. Sci. 27, 242–249 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Padan E. (2008) Trends Biochem. Sci. 33, 435–443 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sitte H. H., Farhan H., Javitch J. A. (2004) Mol. Interv. 4, 38–47 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Veenhoff L. M., Heuberger E. H., Poolman B. (2001) EMBO J. 20, 3056–3062 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rimon A., Tzubery T., Padan E. (2007) J. Biol. Chem. 282, 26810–26821 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hou Z., Matherly L. H. (2009) J. Biol. Chem. 284, 3285–3293 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bamber L., Harding M., Monné M., Slotboom D. J., Kunji E. R. (2007) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 104, 10830–10834 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.MacKinnon R. (1991) Nature 350, 232–235 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yerushalmi H., Lebendiker M., Schuldiner S. (1996) J. Biol. Chem. 271, 31044–31048 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kao L., Sassani P., Azimov R., Pushkin A., Abuladze N., Peti-Peterdi J., Liu W., Newman D., Kurtz I. (2008) J. Biol. Chem. 283, 26782–26794 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Geertsma E. R., Duurkens R. H., Poolman B. (2005) J. Mol. Biol. 350, 102–111 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fry D. W., Yalowich J. C., Goldman I. D. (1982) J. Biol. Chem. 257, 1890–1896 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cao W., Matherly L. H. (2003) Biochem. J. 374, 27–36 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Payton S. G., Haska C. L., Flatley R. M., Ge Y., Matherly L. H. (2007) Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1769, 131–138 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zhao R., Chattopadhyay S., Hanscom M., Goldman I. D. (2004) Clin. Cancer Res. 10, 8735–8742 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hou Z., Stapels S. E., Haska C. L., Matherly L. H. (2005) J. Biol. Chem. 280, 36206–36213 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lowry O. H., Rosebrough N. J., Farr A. L., Randall R. J. (1951) J. Biol. Chem. 193, 265–275 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wong S. C., Zhang L., Witt T. L., Proefke S. A., Bhushan A., Matherly L. H. (1999) J. Biol. Chem. 274, 10388–10394 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Laemmli U. K. (1970) Nature 227, 680–685 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Goldman I. D. (1971) Biochim. Biophys. Acta 233, 624–634 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Isacoff E. Y., Jan Y. N., Jan L. Y. (1990) Nature 345, 530–534 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mathai J. C., Agre P. (1999) Biochemistry 38, 923–928 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Emerick M. C., Fambrough D. M. (1993) J. Biol. Chem. 268, 23455–23459 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nicke A., Rettinger J., Schmalzing G. (2003) Mol. Pharmacol. 63, 243–252 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sahin-Tóth M., Lawrence M. C., Kaback H. R. (1994) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 91, 5421–5425 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Köhler K., Forster I. C., Lambert G., Biber J., Murer H. (2000) J. Biol. Chem. 275, 26113–26120 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bossi E., Soragna A., Miszner A., Giovannardi S., Frangione V., Peres A. (2007) Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 292, C1379–C1387 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tzubery T., Rimon A., Padan E. (2008) J. Biol. Chem. 283, 15975–15987 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Loo T. W., Bartlett M. C., Clarke D. M. (2005) J. Bioenerg. Biomembr. 37, 501–507 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gong Q., Jones M. A., Zhou Z. (2006) J. Biol. Chem. 281, 4069–4074 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Loo T. W., Clarke D. M. (1994) J. Biol. Chem. 269, 28683–28689 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Drori S., Sprecher H., Shemer G., Jansen G., Goldman I. D., Assaraf Y. G. (2000) Eur. J. Biochem. 267, 690–702 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kitayama S., Ikeda T., Mitsuhata C., Sato T., Morita K., Dohi T. (1999) J. Biol. Chem. 274, 10731–10736 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.