Abstract

Intrinsically disordered proteins or protein regions play an important role in fundamental biological processes. During spliceosome activation, a large structural rearrangement occurs. The Prp19 complex and related factors are involved in the catalytic activation of the spliceosome. Recent mass spectrometric analyses have shown that Ski interaction protein (SKIP) and peptidylprolyl isomerase-like protein 1 (PPIL1) are Prp19-related factors that constitute the spliceosome B, B*, and C complexes. Here, we report that a highly flexible region of SKIP (SKIPN, residues 59–129) is intrinsically disordered. Upon binding to PPIL1, SKIPN undergoes a disorder-order transition. A highly conserved fragment of SKIP (residues 59–79) called the PPIL1-binding fragment (PBF) was sufficient to bind PPIL1. The structure of PBF·PPIL1 complex, solved by NMR, shows that PBF exhibits an ordered structure and interacts with PPIL1 through electrostatic and hydrophobic interactions. Three subfragments in the PBF (residues 59–67, 68–73, and 74–79) show hook-like backbone structure, and interactions between these subfragments are necessary for PBF·PPIL1 complex formation. PPIL1 is a cyclophilin family protein. It is recruited by SKIP into the spliceosome by a region other than the peptidylprolyl isomerase active site. This enables the active site of PPIL1 to remain open in the complex and still function as a peptidylprolyl cis/trans-isomerase or molecular chaperon to facilitate the folding of other proteins in the spliceosomes. The large disordered region in SKIP provides an interaction platform. Its disorder-order transition, induced by PPIL1 binding, may adapt the requirement for a large structural rearrangement occurred in the activation of spliceosome.

Keywords: Protein Domains, Protein Folding, Protein Structure, RNA Processing, RNA Splicing

Introduction

Pre-mRNA splicing, the removal of introns from mRNA precursors, is a dynamic process and requires many conformational rearrangements (1). It is catalyzed by the spliceosome, which is a large machine formed by ordered interactions of several small nuclear ribonucleoproteins (snRNPs),3 U1, U2, U5, and U4/U6, and numerous other less stably associated non-snRNP splicing factors (2). The assembly of the spliceosome goes through many intermediate stages. The stable intermediate complexes are the A, B, and C complexes. After the complex A is formed by pre-mRNA binding to the U1 and U2, it recruits U4/U6·U5 tri-snRNP, forming the B complex. The B complex is still inactive and requires conformational and compositional rearrangements to form active spliceosome, complex B* (3). Complex B* undergoes the first catalytic step of splicing to generate complex C. After additional rearrangements occur in the spliceosomal RNP network (4), complex C undergoes a second catalytic step and releases the mRNA.

Mass spectrometric analyses of the human A (5), B (6, 7), B* (8), and C (7) complexes indicate that there are dramatic changes in protein content during splicing. For example, in the A complex to B complex transition, ∼25 proteins are recruited and more than 35 non-snRNP proteins associated. These include the Prp19·CDC5 complex and Prp19-related factors. Subunits of these become more stably integrated in the B* complex (8, 9). Recently, Bessonov et al. (7) purified the catalytically active C complex and identified its stable RNP core, which constituted with Prp19·CDC5 and Prp19-related factors. Ski interaction protein (SKIP) and peptidylprolyl isomerase-like protein 1 (PPIL1) belong to Prp19-related factors and are included in this stable RNP core. Both of them are believed to be involved in the activation of the spliceosome (2, 8, 9).

Human SKIP (536 residues) is colocalized with SC35, a splicing factor at nuclear speckles (11). Expression of a dominant negative SKIP (residues 87–342 of SKIP) results in a 1,25- (OH)2D3-dependent transient accumulation of the unspliced transcripts (12), indicting that SKIP influences pre-mRNA splicing. Nagai et al. (13) reported that SKIP affected the splicing of a natural gene product, the downstream intron, and aberrant splicing. An ortholog of SKIP in Saccharomyces cerevisiae, Prp45p, is essential for pre-mRNA splicing; it interacts with splicing factors Prp46p (14, 15). SKIP is also a multifunctional protein, which is involved in transcription initiation, transcription elongation, and the cell cycle. As a transcriptional coactivator, it is linked to activation of important transcription factors, such as vitamin D receptor, CBF1, Smad2/3, and MyoD (16). It was proposed that SKIP may be a transcription/splicing coupling factor based on the participation of SKIP in transcription and splicing.

PPIL1 (166 residues) belongs to a novel subfamily of cyclophilin, which contains a single domain (PPIase domain) and has a SKIP-binding region and a cyclosporin A (inhibitor of peptidylprolyl isomerase)-binding region (17). SKIP recruits PPIL1 into the spliceosome. The N-proximal 180 amino acids of SnwA (ortholog of human SKIP) interact with CypE (ortholog of human PPIL1) in Dictyostelium discoideum (18). Xu et al. (17) confirmed that the N-terminal of SKIP (residues 59–129, SKIPN) is sufficient to associate with PPIL1. Nevertheless, how they bind and the structural basis of their binding are still unknown.

Here, we report that a large region in SKIP (71 residues) is intrinsically disordered in the free state and undergoes a disordered-ordered transition upon binding to PPIL1. We further identified that a shorter fragment of SKIP (PBF, PPIL1 binding fragment of the SKIP, residues 59–79) was involved in PPIL1 interaction. Furthermore, the complex structure of PBF·PPIL1 was determined by NMR, and the details of the interaction interfaces are described. The biological implication of the disorder-order transition of SKIPN upon binding PPIL1 during the spliceosome assembly is discussed.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Sample Preparation

The human PPIL1 mutant clone (A43S) was a gift from Prof. Q. H. Zhang. Clones, including wild-type PPIL1, SKIPN (residues 59–129 of SKIP), PBF (residues 59–79 of SKIP), SKIP172 (residues 1–172 of SKIP), PPIL1-(GGGS)4-PBF (linking the C-terminal of PPIL1 and PBF with the sequence Gly-Gly-Gly-Ser repeated four times), and PPIL1 mutants (K30A, K30D, K91A, K91D, R131K, R131E, R131A, L116A, L116D, and I136A/V139A) were constructed by using megaprimer PCR (19) or PCR (supplemental Table S1). All selected clones were verified by DNA sequencing.

The recombinant PPIL1 plasmid was introduced into Escherichia coli BL21(DE3) cells for protein expression. Cells were grown in either Luria-Bertani medium for unlabeled samples or minimal medium with H2O or ∼75% D2O supplemented as appropriate with glucose or [13C6]glucose and 15NH4Cl for 15N-, 15N/13C-, or 15N/13C/2H-labeled PPIL1 samples. Cultures were induced at an A600 nm of 0.6–0.8 with 1 mm isopropyl 1-thio-β-d-galactopyranoside at 16 °C or 37 °C. Proteins were purified with a Ni-NTA column and then a Superdex 75 gel-filtration column.

To obtain 15N/13C/2H-labeled SKIPN, we cultured cells with media dissolved in ∼100% D2O. SKIPN is a highly soluble protein (>2 mm). For protein SKIPN expressed in ∼100% D2O, all the deuterium in the amide groups can be rapidly exchanged with the proton from water. Therefore, the completed backbone chemical shift assignment of SKIPN was performed using three-dimensional heteronuclear NMR experiments.

To obtain PBF, we constructed the PBF clone with vector pET32(c). PBF fused with Trx, and an enterokinase cleavage site was expressed in E. coli cells. Purified fused proteins (∼15.4 mg) were dialyzed against the cleavage buffer (20 mm Tris-HCl, 50 mm NaCl, 2 mm CaCl2, pH 7.4) and then incubated with enterokinase (37 units) at 20.5 °C for ∼16 h in 15.5-ml mixture and then further separated on a Ni-NTA column. The resultant Ala-Met-PBF was mixed with purified unlabeled His6-tagged-PPIL1 (molar ratio of PBF/PPIL1 was ∼1/1.3) and loaded onto a new Ni-NTA column. The complex Ala-Met-PBF·PPIL1 was eluted after washing with the washing buffer (20 mm Tris-HCl, 150 mm NaCl, pH 7.8).

Expression and purification of SKIPN, SKIP172, PPIL1-(GGGS)4-PBF, and PPIL1 mutants were the same as those for PPIL1. Before use, the buffer of these samples was exchanged into Buffer A containing 50 mm phosphate buffer, 50 mm NaCl, 1 mm EDTA, 0.2‰ NaN3, and 0.5 mm dithiothreitol, pH 6.5. The purity of these proteins was assessed by SDS-PAGE (Fig. 1).

FIGURE 1.

Tricine-SDS-PAGE of proteins. A, lanes 1–9, proteins are PPIL1-(GGGS)4-PBF, R131A, R131E, R131K, K91D, K91A, K30D, K30A, and wild-type PPIL1. B, lanes 1–6, proteins are protein molecular mass markers (116.0, 66.2, 45.0, 35.0, 25.0, 18.4, and 14.4 kDa, respectively, from top to bottom), L116A, L116D, I136A/V139A, SKIPN, and SKIP172.

Peptide Synthesis

Unlabeled peptides (PBF, its subfragments, and its mutants (supplemental Table S2)) were synthesized by GL Biochem or Sangon (Shanghai). They were supplied with stringent analytical specifications (purity level above 98%), which included high-performance liquid chromatography and mass spectrometry analysis. Before use, peptides were weighed and dissolved in Buffer A, and the pH of each sample was systematically controlled and, if necessary, adjusted to a value of 6.5 by addition of dilution NaOH or HCl solution.

NMR Spectroscopy

All spectra were recorded at 25 °C on Bruker DMX500 or DMX600 spectrometers. The standard NMR methodology was used as described (17). The sequential and side-chain assignments for SKIPN(15N/13C/2H), SKIPN(15N/13C/2H)·PPIL1 (molar ratio is 1:1.5), PBF(15N/13C)·PPIL1 (molar ratio is ∼1:1.3), PPIL1(15N/13C/2H)·PBF (molar ratio is 1:3.1), and PPIL1-(GGGS)4-PBF(15N/13C) were performed. Sequential assignments of SKIPN include HNCO, HN(CA)CO, HNCA, HN(CO)CA, HNCACB, HN(CO)CACB, HNN, and HN(C)N (20). Interproton distance restraints were derived from multidimensional NOE spectra with mixing times of 130 ms. NOE experiments included three-dimensional 13C-separated and 15N-separated NOE spectra. For interface NOE restraints, two-dimensional 15N,13C double-half-filter NOE spectra were recorded by using samples PBF(15N/13C)·PPIL1 and PPIL1(15N/13C/2H, expressed in medium with ∼75% D2O)·PBF (Fig. 6C). Freeze-dried 15N/13C-PPIL1-(GGGS)4-PBF was dissolved in 100% D2O, and 15N-1H HSQC spectra were recorded to identify slow exchanging amide protons of the sample.

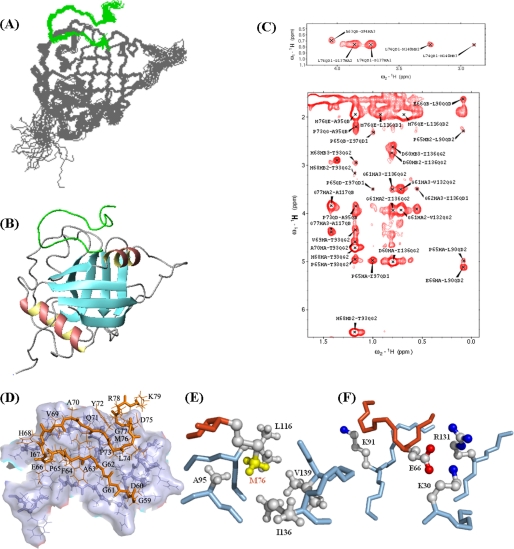

FIGURE 6.

Structures of PPIL1·PBF. A, best-fit superposition of the backbone atoms of the final 20 NMR structures of PPIL1·PBF. PBF is shown in green, and PPIL1 is shown in gray. Residues 167–182, the linker (GGGS)4, have been omitted. B, ribbon representation of the energy-minimized average structure of PPIL1·PBF. C, two-dimensional 15N,13C double half-filter NOESY of 15N/13C/2H-labeled PPIL1 (expressed in ∼75% D2O media) in complex with unlabeled PBF. D, interface of PPIL1·PBF structure. PBF is shown in brown, and the interface in PPIL1 is shown in gray. Interactions involving Met76 (E) and Glu66 (F) of SKIPN. For E and F, the backbone of PBF is shown in brown, and the backbone of PPIL1 is shown in steel blue. Proton and carbon atoms of the side chain, nitrogen atoms of the Arg and Lys side chains, oxygen atoms of the Asp side chain, and the methyl group of Met76 in PBF are shown in gray, blue, red, and yellow, respectively.

Due to the difficulty in obtaining full side-chain assignments of the sample PBF(15N/13C)·PPIL1, a fused protein PPIL1-(GGGS)4-PBF was prepared. Cross-peaks of PBF for the fused protein (red) are well overlapped with those for the complex SKIPN (15N/13C/2H)·PPIL1 (blue, supplemental Fig. S1B). The same is true for the cross-peaks of PPIL1 in the fused protein (red) and PPIL1(15N):SKIPN (blue, supplemental Fig. S1C), demonstrating that PPIL1-(GGGS)4-PBF is representative of the PPIL1·PBF complex in structure (supplemental Fig. S1A). In total, for the fused protein, except for Pro and the linker (GGGS)4, 97% backbone and >90% atoms of the side chain were assigned.

Structure Calculations

Comparing two-dimensional 15N,13C double-half-filter NOESY of the samples PBF(15N/13C)·PPIL1 and PPIL1(15N/13C/2H)·PBF with the 13C-separated NOESY of the sample 15N/13C-PPIL1-(GGGS)4-PBF, we obtained 17 unambiguous interface constrains between PPIL1 and PBF (Asp184-HB2/HB3 and HA with Ile136-QG2, Gly185-HA2 and HA3 with Val132-QG2, Pro189-HA with Ile97-QD1, Glu190-HA with Leu90-QD2, His192-HA with Thr93-QG2, Leu198-QD1 with Gly137-HA2 and HA3 and Asn140-HB2 and HB3, Met200-QE with Asn140-HB2 and HB3 and Ala95-QB, Gly201-HA2 and HA3 with Ala117-QB). The CSI (21) program was used to obtain the backbone dihedral angles in secondary structures on the basis of chemical shift information. These constrains were added during the automatic NOE assignment by program CYANA 2.1 (22). After refined by manually, the initial structures of PPIL1·PBF calculated by CYANA were further chosen for refinement in explicit water by using CNS (23, 24) with python script reported by Jung et al. (25). The 20 structures with the lowest energy were chosen for structural analysis.

CSI

The chemical shift index (CSI) provides the secondary structural preferences of each residue of SKIPN. Here, a random-coil reference dataset from c-GGXGG-NH2 peptides in 8 m urea at pH 2.3 was adopted (26), and the corresponding correction factors (27) were used to correct local sequence-dependent contributions. The error derived from the differences in the acquisition temperature and pH was processed by the inherent correction function of the CSI in NMRView (28).

CD Spectroscopy

The temperature dependences of the CD spectra for proteins SKIPN and SKIP172 were obtained using a Jasco-810 spectropolarimeter equipped with the Julabo temperature-controller F25-HD. SKIPN or SKIP172 was dialyzed against buffer containing 20 mm phosphate, 50 mm NaCl, pH 6.5, before use. Far-UV CD spectra were recorded at wavelengths between 190 nm and 250 nm using a 0.1-cm path length cell. Near-UV CD spectra were recorded at wavelengths between 240 and 320 nm using a 1-cm path length cell. All CD spectra were the average of three or five successive spectra. Mean ellipticity values per residue ([θ]) were calculated as [θ] = 3300 mΔA/(lcn), where l represents path length, n is the number of residues (80 residues for SKIPN and 178 residues for SKIP172), m is the molecular mass in daltons (9,040 Da for SKIPN and 20,055 Da for SKIP172), and c is the protein concentration expressed in milligrams/ml.

DSC Experiments

DSC experiments were carried out with a VP-DSC calorimeter. Calorimetric cells were kept under an excess pressure of 30 p.s.i. to prevent degassing during the scan. In all measurements, the buffer from the last dialysis step was used in the reference cell of the calorimeter. Several buffer-buffer baselines were obtained before each run with a protein solution to ascertain proper equilibration of the calorimeter. An additional buffer-buffer baseline was obtained after each protein run to check that no significant change in instrumental baseline had occurred. Lysozyme (Fluke) was used as the control. Data were analyzed using the MicroCal VP-DSC standard analysis software.

Surface Plasmon Resonance Measurements

SKIPN was coupled to a carboxymethyl-dextran CM5 sensor chip with an amine coupling kit. Binding was observed upon injection of different concentrations of PPIL1 or its mutants. The plateau values reached after completion of the association reactions were analyzed by using a Langmuir binding isotherm.

NMR Backbone Relaxation Experiments

15N relaxation experiments were carried out at 25 °C using published methods (29). 15N T1 relaxation rates were measured with 8 relaxation delays: 11, 62, 142, 243, 364, 525, 757, and 1150 ms. 15N T2 relaxation rates were measured with 6 relaxation delays: 17.6, 35.2, 52.8, 70.4, 105.6, and 140.8 ms. A recycle delay of 1 s was used for measurement of T1 and T2 relaxation rates. The spectra measuring 1H-15N NOE were acquired with a 2-s relaxation delay followed by a 3-s period of proton saturation. The spectra recorded in the absence of proton saturation employed a relaxation delay of 5 s. The exponential curve fitting and extract of T1 and T2 were processed by Sparky.

Chemical Shift Perturbation

To investigate the PPIL1 and PBF binding sites, 0.35 mm 15N-labeled PPIL1 or 15N-labeled SKIPN in Buffer A was used for NMR titration experiments at 25 °C. 15N-1H HSQC of sample was recorded until there was no change in the spectrum. The final molar ratios were 1:2 for 15N-labeled SKIPN:K30A and 15N-labeled SKIPN:K91A, 1:3 for 15N-labeled SKIPN:K30D, 1:5 for 15N-labeled SKIPN:R131K, and 15N-labeled SKIPN:R131A. For 15N-labeled PPIL1 titrating with PBF or its mutants, their final molar ratios were more than 1:6.

RESULTS

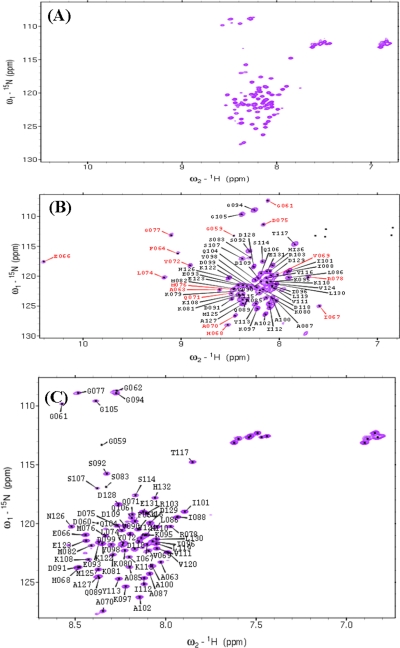

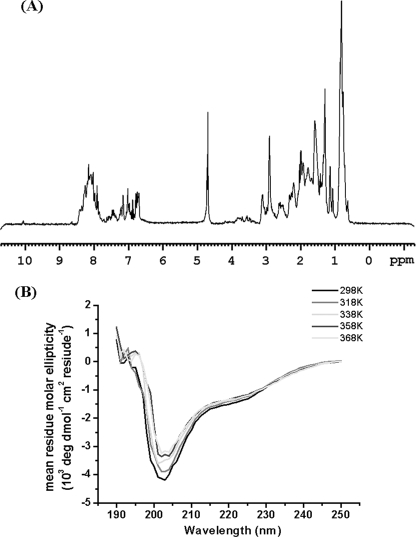

SKIPN in the Free State Is an Intrinsically Unstructured Fragment in Solution

Backbone amide proton chemical shifts of protein SKIPN alone are poorly dispersed (7.8–8.6 ppm) in 1H-15N correlated NMR spectra (Fig. 2, A and C), indicating that SKIPN may be an unstructured protein fragment. CSI provides the secondary structural preferences of each amino acid residue (26, 27). As shown in Fig. 3A, the average deviations of the 13CA, 13CB, 13CO, and 1HN chemical shifts from random coil values (Δδ) for SKIPN are <1.0, 1.5, 0.5, and 0.3 ppm, respectively, which indicate that free SKIPN has no secondary structural preferences.

FIGURE 2.

A, 1H-15N HSQC spectrum of ∼1. 0 mm 15N/13C/2H-labeled SKIPN alone in Buffer A at 25 °C. B, the two-dimensional 15N,1H-TROSY spectrum of 0.6 mm 15N/13C/2H-labeled SKIPN in complex with 0.9 mm unlabeled PPIL1 in Buffer A at 25 °C. C, the backbone assignments of free SKIPN (expressed in ∼100% D2O media).

FIGURE 3.

Characteristics of protein SKIPN in the free state. A, the deviations of the 13CA, 13CB, 13CO, and 1HN chemical shifts from random coil values (Δδ) for protein SKIPN. B, far-UV CD spectra of SKIPN from 5 to 95 °C at 5 °C intervals. C, changes in ellipticity at 200, 208, 220, and 275 nm as function of temperature (from 5 to 95 °C at 5 °C intervals) of SKIPN in 50 mm NaCl, 20 mm phosphate buffer, pH 6.5. For far-UV CD spectra, 0.2 mg/ml SKIPN was used. For near-UV CD spectra, 2 mg/ml SKIPN was used. D, the heat capacity of 1 mg/ml SKIPN (gray line) was recorded by nano-DSC at a rate of 1 °C/min. Lysozyme (black line) at 3 mg/ml was used as control.

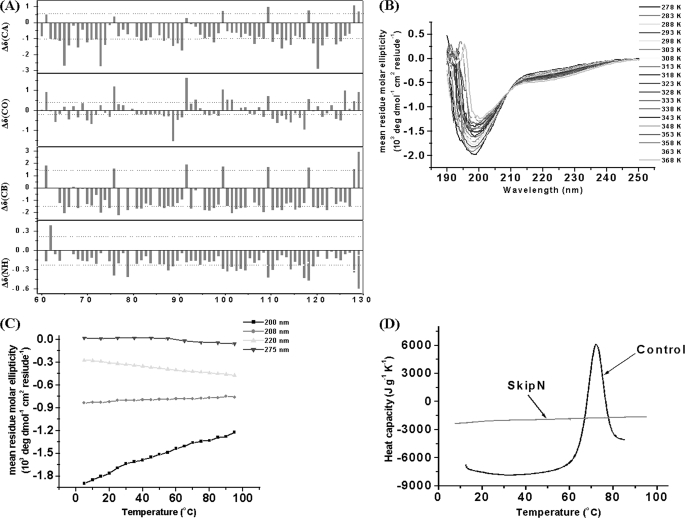

CD spectra and DSC experiments further confirm that SKIPN is an unstructured protein fragment. SKIPN has negative bands near 199 nm and low ellipticity above 210 nm from 5 to 95 °C (Fig. 3B), which are consistent with those of disordered proteins (30, 31). Upon temperature increases from 5 to 95 °C in 5 °C steps, signals at far-UV CD208 nm and CD220 nm characterized α-helical structure, and CD200 nm characterized coil structure increased or decreased linearly rather than in as a state transition (Fig. 3C). This result suggests that SKIPN has no temperature-dependent structure transition. The ellipticity in 275 nm related with four Tyr residues in SKIPN (no Trp residue) shows slight changes (Fig. 3C), reflecting the high mobility of aromatic side chains (32). Further evidence for an unfolded state is seen in DSC experiments (Fig. 3D). For the control sample, a transition temperature at ∼72 °C was found. For SKIPN, there was no transition found. These data show that SKIPN in the free state is an unstructured fragment in solution from 4 to 95 °C.

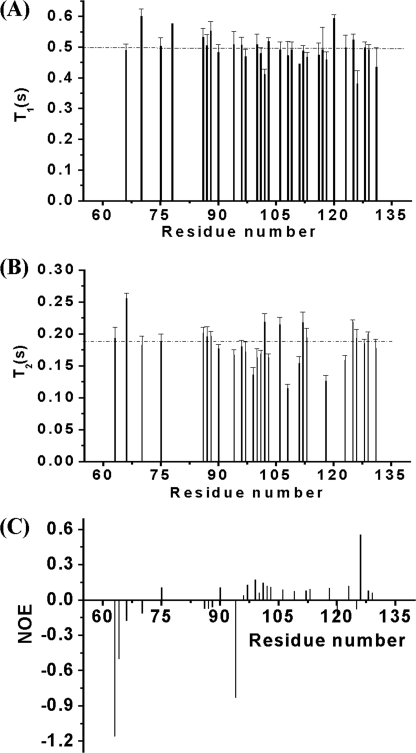

To probe the dynamic properties of SKIPN in solution, 15N longitudinal (T1) and transverse (T2) relaxation times and steady-state 1H-15N NOE were measured for free states. The average values of T1 (Fig. 4A), T2 (Fig. 4B), and 1H-15N NOE for positive values (Fig. 4C) of SKIPN were 0.50 s, 0.18 s, and 0.12, respectively. The steady-state 1H-15N NOE is an excellent measure of flexibility in proteins (33, 34). As shown in Fig. 4C, residues with negative NOE values can be divided into five regions, including Ala63 to Ala70, Leu86 to Ile88, Gly94, Val120, and Met125. Small positive or negative NOE values show that SKIPN alone (9.0 kDa) is very flexible, especially for these five regions in solution. Together, the experiments demonstrate that free SKIPN in solution is an intrinsically unstructured protein with backbone flexibility varying by region.

FIGURE 4.

Backbone dynamics of 0.3 mm15N-labeled SKIPN alone in Buffer A at 25 °C. T1 (A), T2 (B), and 15N-1H NOE (C) values of the backbone amide resonances of protein SKIPN are plotted by residue number. The dashed lines represent the average T1 and T2 of SKIPN. Residues with overlapping, vanishing cross-peaks, without assignment, or residue Pro (residues 65, 73, and 121) were excluded.

Disorder-Order Transition of PBF upon Binding to PPIL1

Upon titration of PPIL1 into 15N-labeled SKIPN, the intensity of some cross-peaks in the 1H-15N HSQC for the free SKIPN diminished, new resonances appeared, and the intensity enhanced concomitant with the formation of the SKIPN·PPIL1 complex. Exchange between the free and bound states of residues from Gly59 to Arg78 of SKIPN was slow on the chemical shift timescale, and cross-peaks corresponding to both states were observed at intermediate SKIPN·PPIL1 concentration ratios. This is consistent with 15N-labeled PPIL1 titrating with SKIPN, which is also a slow rate exchange process. As shown in Fig. 2B, when the molar ratio of SKIPN·PPIL1 reached ∼1:1.5, cross-peaks of the free state related to both states were nearly diminished. In the bound state, peaks of Gly61, Phe64, Glu66, Ile67, His68, Tyr72, Leu74, Asp75, Gly77, and Arg78 are well dispersed in two-dimensional 15N,1H-TROSY spectrum, especially for Glu66 (chemical shift of HN is 10.4 ppm), which suggests that upon binding to PPIL1, intrinsically unstructured SKIPN undergoes a disorder-order transition.

Residues 59–79 of SKIP (PBF) Involved in PPIL1 Binding

It has been previously reported that SKIPN (residues 59–129 of SKIP) is sufficient to associate with PPIL1 (17). Here, we further demonstrated that PBF (residues 59–79 of SKIP) is the PPIL1-binding region. As shown in Fig. 2B, well dispersed peaks in the two-dimensional 15N,1H-TROSY spectrum result from residues Gly61 to Arg78, which suggests that this region of SKIPN may be involved in PPIL1 binding. The chemical shift deviations of HN and H between SKIPN alone and complexed with PPIL1 are shown in supplemental Table S3. To further investigate this fragment, 15N/13C-labeled Ala-Met-PBF (residues 59–79 of SKIPN) was prepared. By comparing cross-peaks in 1H-15N-correlated NMR spectra of Ala-Met-PBF(15N/13C)·PPIL1 (Fig. 5A) and SKIPN(15N/13C/2H)·PPIL1 (Fig. 2B), we found that the well dispersed peaks of PBF were overlapped between two spectra. Moreover, the average transverse relaxation time of PBF (42 ms) was much lower than that of the other residues of SKIPN (103 ms) in the complex state (Fig. 5B), indicating that PBF binds tightly with PPIL1 while the remaining residues of SKIPN are in the bound state. These results demonstrate that the PBF of SKIP constitutes a PPIL1-binding region.

FIGURE 5.

A, 1H-15N HSQC spectrum of ∼0. 7 mm 15N/13C-labeled Ala-Met-PBF of SKIP in complex with 0.9 mm unlabeled PPIL1 in Buffer A at 25 °C. B, T2 values of 0.6 mm 15N/13C/2H-labeled SKIPN in complex with 0.9 mm unlabeled PPIL1 backbone amides in Buffer A at 25 °C. The lower and higher dashed lines represent the average T2 of PBF (residues 59–79) and another fragment of SKIPN (residues 80–129). Residues with overlapping, vanishing cross-peaks, without assignment, or residue Pro (residues 65, 73, and 121) were excluded.

Overall Structure of PPIL1-(GGGS)4-PBF

The coordinates of 20 NMR structures have been deposited in the Protein Data Bank (code 2K7N), and the structural statistics are listed in Table 1. In the complex, PPIL1 exhibits the typical cyclophilin fold with an anti-parallel eight-stranded β-barrel capped by two α-helices (Fig. 6B). Comparing structures of PPIL1 in the complex and the free state, there were no large conformation changes for PPIL1 upon PBF binding. Two active site residues, arginines 55 and I57 located on β3, were not affected by the binding of PBF. The average pairwise root mean square (r.m.s.) differences of backbone and heavy atoms of well defined regions (residues 13–64, 97–102, 108–145, and 157–164) between PPIL1 in the free state and in the complex PPIL1·PBF were 1.77 ± 0.09 and 2.61 ± 0.12 Å, respectively. The largest deviations of PPIL1 structures in the free and complex states arose from the N-terminal six residues and the PBF binding interface. Upon binding to PPIL1, PBF formed an ordered hook-like structure and lay on PPIL1 (Fig. 6A), which could be segregated into three sequential subfragments (Fig. 6D): PBF1 (residues 59–67), PBF2 (residues 68–73), and PBF3 (residues 74–79). 33 or 22 intramolecular NOE constraints were found between PBF2 and PBF1 or PBF3, respectively. Intramolecular interactions appear to be crucial for the stability of the complex, because neither PBF1, PBF2, PBF3, nor PBF12 alone could interact with PPIL1 as shown by NMR titration experiments (supplemental Table S2). Using mixed samples (including PBF1 mixed with PBF2; PBF12 mixed with PBF3; and PBF1, PBF2, and PBF3 mixed together) to titrate PPIL1, complex formation was not observed. These results suggest that intact PBF is necessary for its binding to protein PPIL1. Lack of any of these fragments will prevent their interaction with PBF.

TABLE 1.

NMR structure statistics of human PPIL1-PBF

| NMR constraints | PPIL1 | PBF | Interface |

|---|---|---|---|

| Distance constraints | 2511 | 262 | 166 |

| Intraresidue | 571 | 70 | |

| Sequential (|i − j| = 1) | 774 | 108 | |

| Medium range (2 < |i − j| ≤ 4) | 368 | 58 | |

| Long-range (|i − j| > 4) | 798 | 26 | |

| Hydrogen bonds | 110 | ||

| Torsion angle constraints | 112 |

| Structure statistics (20 structures) | |

|---|---|

| Violations (mean ± S.D.) | |

| Distance constraints (Å) | 0.0236 ± 0.0014 |

| Dihedral angle constraints (°) | 0.6808 ± 0.1636 |

| Deviations from idealized geometry | |

| Bond lengths (Å) | 0.0039 ± 0.00013 |

| Bond angles (°) | 0.5088 ± 0.0159 |

| Impropers (°) | 1.3695 ± 0.0738 |

| Average pairwise r.m.s. deviationa (Å) | |

| Heavy | 1.91 ± 0.27 |

| Backbone | 1.18 ± 0.29 |

| Ramachandran plot analysis | |

| Residues in most favored regions | 77.8% |

| Residues in additionally allowed regions | 20.4% |

| Residues in generously allowed regions | 1.2% |

| Residues in disallowed regions | 0.5% |

a Pairwise r.m.s. of aa 13–163 and 184–202. The r.m.s. of backbone and heavy atoms of well defined regions (aa 13–64, 97–102, 108–145, 157–164, and 183–203) were 0.67 ± 0.08 and 1.46 ± 0.14 Å, respectively.

The PBF·PPIL1 Interface

The PBF·PPIL1 interface was analyzed by ProFace (35) with the PPIL1·PBF-20 average structure of the ensembles. Here, the value of threshold distance for clustering interface atoms into spatial patches is 15.0 Å (36). The interface area upon complex formation is 1622.4 Å2 involving 26 residues from PPIL1 and 19 residues from PBF. That includes Tyr28, Lys30, Asp59, Asp89–Leu98, Thr115–Pro118, Gly130–Asn140, and Met144 at PPIL1, which is consistent with the results of titrating SKIPN into 15N-labeled PPIL1. That also includes Gly59–Leu74, Met76, and Gly77 at SKIP. Non-polar residues account for ∼60%, and polar residues or charged residues account for ∼20% at this interface. The hydrophobic interface formed between PBF and PPIL1 includes many methyl-containing residues, such as Met76 of PBF contacting Ala95, Leu116, Ile136, and Val139 of PPIL1, Ala63 of PBF contacting Ile97 of PPIL1, and Ile67 of PBF contacting Thr93 of PPIL1. From the solution structures, it is suggested that electrostatic interactions also play a role in maintaining stability of the PPIL1·PBF complex. The side chain of Glu66 of PBF is located close to the amino group of Lys30 and guanidinium group of Arg131 of PPIL1. Also, the amino group of Lys91 of PPIL1 is located near the side chain of His68 of PBF.

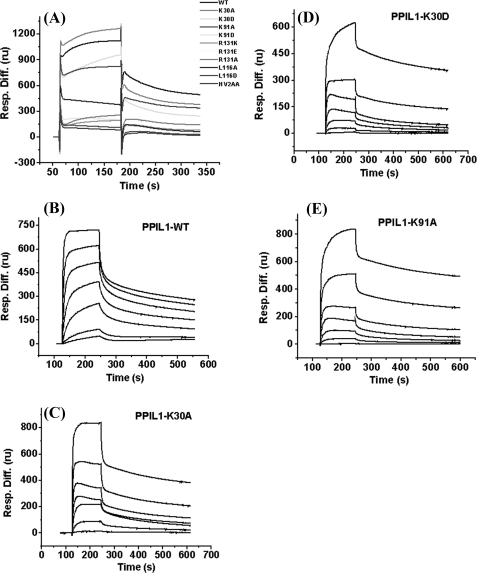

One key residue of PBF at the interface is Met76. The methyl group of Met76 inserts into a hydrophobic cavity of PPIL1 containing Ala95, Leu116, Ile136, and Val139 (Fig. 6E). Therefore, a PBF mutant peptide Met76 to Ala76 (M76A) was synthesized, and three PPIL1 mutants L116A, L116D, and I136A/V139A were prepared. PBF mutant M76A could not interact with PPIL1 in titrations of mutant peptide into 15N-labeled PPIL1 (supplemental Fig. S2A). In surface plasmon resonance experiments, replacing Leu116 of PPIL1 with Ala decreased the affinity of PPIL1 for SKIPN, whereas PPIL1 mutants L116D and I136A/V139A abolished the binding (Fig. 7A). Thus, the hydrophobic interaction network between Met76 of SKIPN and the pocket of PPIL1 contributes substantially to the tight binding between these two proteins. To destroy the interaction of Met76 with the hydrophobic cavity is to destroy the interaction of PBF3 with PPIL1.

FIGURE 7.

Kinetic study the interaction between SKIPN to PPIL1 or its mutants by a BIAcore 3000 system at 25 °C. Protein SKIPN was immobilized on a CM5 sensor chip by amine coupling. Wild-type PPIL1 or its mutants were injected over sensor chip at concentrations of 5.18 μm in phosphate-buffered saline (A). Wild-type PPIL1 (B) and its mutants K30A (C), K30D (D), and K91A (E) at concentrations from 0 to 5.18 μm: 0.08, 0.16, 0.32, 0.65, 1.30, 2.59, and 5.18 μm in phosphate-buffered saline (pH 7.4). Raw binding data were analyzed by BIAevaluation 4.0 and fit to a 1:1 Langmuir binding model. The equilibrium dissociation constants (KD) are summarized in Table 2.

Another important interface residue is Glu66 of PBF. The chemical shift of the amide hydrogen of Glu66 shifts to low field (10.4 ppm) upon binding to PPIL1. Structure of PPIL1·PBF (Fig. 6F) indicates that carboxyl oxygen atoms of Glu66 are located in a positively charged region of PPIL1 comprising Lys30, Lys91, and Arg131. It is possible to form salt-bridged or hydrogen-bonded between negative charged carboxyl group of Glu66 and positive charged amino acid residues. Three PBF mutants, Glu66 to Asp66, Arg66, and Ala66 (E66A, E66D, and E66R) were synthesized. PBF mutants E66A and E66R cannot bind to PPIL1 in NMR titration experiments (supplemental Fig. S2, B–D), whereas mutant E66D maintained the binding affinity (supplemental Fig. S2E). Furthermore, by using the NMR titration experiments, we found that PPIL1 mutants K30A, K30D, and K91A still bound to SKIPN (supplemental Fig. S2, F–H). The PPIL1-binding activity of three mutants decreased and was investigated by using surface plasmon resonance experiments. The equilibrium dissociation constants for the interaction of SKIPN with the K30A (Fig. 7C) and K30D (Fig. 7D) were 0.36 ± 0.02 and 6.32 ± 3.53 μm, respectively, compared with 0.19 ± 0.04 μm with wild-type PPIL1 (Fig. 7B and Table 2). Replacing Lys91 with an Ala increased the KD to 50.75 ± 7.28 μm (Fig. 7E), whereas mutant K91D abolished the binding of PPIL1 to SKIPN (Table 2). Changing Arg131 to Ala, Asp, or even Lys (supplemental Fig. S2I) caused the complete loss of PPIL1-binding activity. Taken together, these data suggested that while all three positively charged residues may play a role in electrostatic interaction, Arg131 of PPIL1 is the probable H-bond donor to Glu66 of SKIPN.

TABLE 2.

Equilibrium dissociation constants for SKIPN binding to wild-type PPIL1 or its mutants

| PPIL1 or its mutants | KD |

|---|---|

| μm | |

| Wild-type PPIL1 | 0.19 ± 0.04 μm |

| K30A | 0.36 ± 0.02 μm |

| K30D | 6.32 ± 3.53 μm |

| K91A | 50.75 ± 7.28 μm |

| K91D | -a |

| R131A | -a |

| R131D | -a |

| R131K | -a |

| L116A | -b |

| L116D | -a |

| I136A/V139A | -a |

a Very low binding activity.

b Low binding activity.

DISCUSSION

SKIP and PPIL1 Are Components of Prp19-related Factors

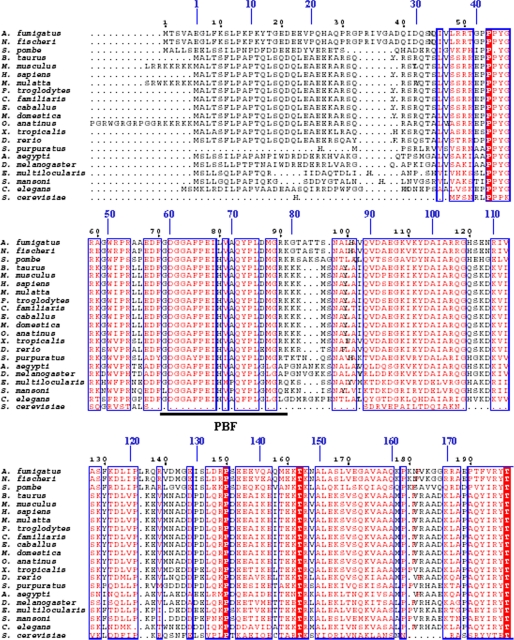

SKIP-like proteins are found in a wide range of organisms. This includes SKIP/SNW1/NCoA-62 in Homo sapiens, Bx42 in Drosophila melanogaster, Prp45p in Schizosaccharomyces pombe and Saccharomyces cerevisiae, Cwf13/SkiP in Aspergillus fumigatus and Neosartorya fischeri, SNW1 in Canis familiaris, Danio rerio, Equus caballus, Mus musculus, and Schistosoma mansoni, and SKIP in Aedes aegypti, Bos taurus, Caenorhabditis elegans, Echinococcus multilocularis, Macaca mulatta, Monodelphis domestica, Ornithorhynchus anatinus, Pan troglodytes, Strongylocentrotus purpuratus, and Xenopus tropicalis. These orthologs are highly conserved with the exception of S. cerevisiae Prp45p (Fig. 8). This protein lacks part of the N terminus, including the highly conserved glycine-rich box and PBF. The rest of the regions are similar to human SKIP. The evolutionary conservation indicates their crucial role in the fundamental biological process.

FIGURE 8.

Sequence alignments of SKIP172 of SKIP. Alignments of SKIP172 sequences from various species, including SKIP/SNW1/NCoA-62 in H. sapiens (NP_036377), Bx42 in D. melanogaster (NP_511093), Prp45p in S. pombe (CAB41231) and S. cerevisiae (P28004), Cwf13/SkiP in A. fumigatus (XP_748038) and N. fischeri (XP_001266227), SNW1 in C. familiaris (XP_531889), D. rerio (AAI33123), E. caballus (XP_001492173), M. musculus (EDL02956), and S. mansoni (ABQ15152), and SKIP in A. aegypti (XP_001648953), B. taurus (NP_001071302), C. elegans (NP_505950), E. multilocularis (CAI59265), M. mulatta (XP_001096395), M. domestica (XP_001367089), O. anatinus (XP_001505367), P. troglodytes (XP_001165674), S. purpuratus (XP_001188665), and X. tropicalis (NP_001017145). The alignments were generated by ClustalW (53) and decorated using ESPript (10). Conserved residues are colored red in blue frames. Lowly conserved residues are in black columns. The black numbers represent the residue number of Cwf13 of A. fumigatus, and the blue numbers represent the residue number of SKIP of H. sapiens. The thick black line represents the PBF of SKIP.

SKIP is a required pre-mRNA splicing factor in nuclear speckles (11). Expression of a dominant negative SKIP results in a 1,25-(OH)2D3-dependent transient accumulation of the unspliced transcripts, indicting that SKIP influences pre-mRNA splicing (12). Nagai et al. (13) reported that SKIP affected the splicing of a natural gene product, the downstream intron, and aberrant splicing. SKIP is recruited to the spliceosome before the first catalytic step and ultimately associates with the spliced-out intron (8).

Mass spectrometric analyses showed that SKIP and PPIL1 are the components of Prp19-related factors. Activated spliceosomes purified by antibody to SKIP and characterized by mass spectrometry showed that the B* complex includes the Prp19·CDC complex and Prp19-related factors, which contain protein PPIL1 (8). The Prp19·CDC complex and its Prp19-related factors appear to be stably integrated into the spliceosome, which indicates that there are major RNP-remodeling events during activation (9). Under native and low stringency conditions the purified B complexes showed that these two group proteins are recruited at the earlier stages of spliceosome assembly (6). Recently, Bessonov et al. (7) reported these two group proteins are more stably associated in the C complex, which constitutes the RNP core of the spliceosome.

The primary structure of SKIP can be divided into three larger regions, N-terminal (residues 1–173), SNW domain (residues 174–332), and C-terminal (residues 333–536) (37, 38). Here, we found that PBF (residues 59–79) of SKIP interacts with protein PPIL1. Ambrozkova et al. (39) found that the C-terminal of spSNW1 (ortholog of human SKIP) interacts with the small subunit of the splicing factor U2AF (spU2AF23, ortholog of human U2AF35) in S. pombe. With binding to spU2AF23, spSNW1 can homodimerize. This result is consistent with U2AF35 and U2AF65 being present in the B complex (6). So, SKIP may be recruited into the B complex by U2AF35. Through the N-terminal of Prp45p (ortholog of human SKIP), Prp45p interacts with Prp46p (ortholog of human PRL1) in S. cerevisiae (14). Protein PRL1 is part of the Prp19·CDC complex and constitutes the core spliceosome. Additionally, SKIP can interact with SNIP1 (40) and PABPN1 (41), which are included in the B and C complexes, but not the core of the C spliceosome (7). From the above analysis, we can see that SKIP may undergo dramatic conformational changes during splicing. Most parts of SKIP are intrinsically unstructured to contact diverse interaction partners.

PBF Undergoes a Disorder-Order Transition on Binding to PPIL1

Herein, we report that SKIPN (71 residues) is an intrinsically disordered protein fragment with high flexibility in the free state. Further experiments show that not only SKIPN (residues 59–129 of SKIP) but also SKIP172 (residues 1–172 of SKIP) are unstructured protein fragments detected by one-dimensional NMR and far-UV spectra. As shown in Fig. 9A, amide proton chemical shifts of protein SKIP172 alone are poorly dispersed (6.5–8.5 ppm) in the one-dimensional NMR spectrum, indicating that SKIP172 may be an unstructured protein region. Similar to SKIPN, SKIP172 has negative bands near 202 nm and low ellipticity above 210 nm from 25 to 95 °C (Fig. 9B), which are consistent with those of disordered proteins (30, 31).

FIGURE 9.

Characteristics of protein SKIP172 in the free state. A, one-dimensional NMR spectrum of SKIP172 (2 mg/ml) in H2O containing 10% D2O at 25 °C in Buffer A. B, far-UV CD spectra of SKIP172 (0.2 mg/ml) in 50 mm NaCl, 20 mm phosphate buffer, pH 6.5, from 25 to 95 °C.

Upon binding to protein PPIL1, SKIPN undergoes a disorder-order transition. We found that conserved PBF (residues 59–79 of SKIP) is involved in the PPIL1 binding. The complex structure of PPIL1·PBF shows that PBF forms an ordered hook-like structure (Fig. 6D) and complexes with PPIL1 through electrostatic and hydrophobic interaction. Glu66 and Met76 of PBF play a key role in binding to PPIL1. Glu66 makes electrostatic interactions with Arg131 in PPIL1, and the methyl group of Met76 inserts into a hydrophobic cavity in PPIL1. The two residues, like two pins, bind to PPIL1 (Fig. 6D). Mutating any of them to Ala abolished the binding of PBF with PPIL1. Moreover, there are three subfragments in PBF, PBF1, PBF2, and PBF3 and extensive intramolecular NOEs exist between them. Neither PBF1 and PBF2 nor PBF3 alone could bind to PPIL1. It appears that favorable intermolecular and intramolecular interactions reduce entropy and drive intrinsically disordered protein fragments toward a low energy conformational state.

During spliceosome activation, a large structural rearrangement occurs. It has been demonstrated that the Prp19p complex and associated proteins are required for the spliceosome activation (42). SKIP and PPIL1 are Prp19-related factors. The large disordered region in SKIP and its disorder-order transition induced by PPIL1 binding may adapt the requirement of large structural rearrangement that occurs in spliceosome activation. Of course, it is necessary to confirm this hypothesis in the future. A disordered to ordered transition has also been observed in another splicing factor. Reidt et al. (43) reported that, in the free state, the U4/U6–60K peptide adopts a random coil conformation. Upon binding to cyclophilin H, residues Ile118–Phe121 of U4/U6–60K peptide expanded the central β-sheet of cyclophilin H and side chain of Phe121 inserts into a hydrophobic cavity. Hayness and Iakoucheva (44) reported that serine/arginine-rich splicing factors belong to a class of intrinsically disordered proteins. They emphasized the importance of disorder for determining broad binding specificity of SR proteins and for spliceosome assembly.

Cyclophilins in Pre-mRNA Splicing

Human spliceosomes contain at least eight cyclophilin family proteins (3, 45), and they are recruited at different stages during splicing. Cyclophilins are PPIases. Isomerization of peptidylprolyl bonds is a rate-limiting step in protein folding. They also act as a molecular chaperon. Spliceosome cyclophilins may mediate structural transitions and otherwise might slow down the splicing (7). The crystal structure of cyclophilin H in complex with U4/U6–60K peptide reveals that the active site of cyclophilin H is free and maintains PPIase activity when bound to this peptide (43). In addition, the cyclophilin inhibitor cyclosporin A slows pre-mRNA splicing in vitro and in vivo, suggesting that the PPIase is available to aid in folding and/or transport of other spliceosomal proteins (46). Similarly, PPIL1 is recruited by SKIP into the spliceosome, which is mediated by a region other than the peptidylprolyl isomerase active site. This enables the active site of PPIL1 to remain open in the complex, and it still can function as a PPIase or molecular chaperon to facilitate folding of other proteins in the activated spliceosome B* or spliceosome C.

SKIP, a Putative Transcription/Splicing Coupling Factor

Considerable evidence supports the concept of a functional coupling between RNA polymerase II-directed transcription and RNA splicing (47, 48). SKIP is a transcriptional coactivator. For example, endogenous SKIP can be recruited to the vitamin D-responsive promoter regions of relevant target genes and activate vitamin D receptor. It is a unique nuclear receptor coactivator, because it lacks the LXXLL motifs, which are characteristic of a large variety of coactivators. In addition, SKIP recruited to the promoter regions was markedly delayed relative to other LXXLL-containing coactivators (12, 49), and this may be reflective of a potential role in splicing of the nascent RNA transcript. Considering functions of SKIP relevant to both transcription and mRNA splicing, it was proposed that SKIP may be a putative transcription/splicing coupling factor. Another example is the observation that SKIP physically associates with U5snRNPs and CycT1:CDK9/P-TEFb in nuclear extracts and enhances HIV-1 Tat-regulated elongation. This provides some insights into the role of transcription elongation and splicing factors at the HIV-1 promoter (50).

PPIL1 is recruited by SKIP into spliceosome. It may function as a PPIase or molecular chaperon to facilitate folding of other proteins both in transcription and in splicing. Recently, Bourquin et al. (51) reported that PPIG (also known as SR-Cyp, CARS-Cyp, and CYPG in humans) is localized at nuclear speckles. It contains a serine/arginine-rich (SR) domain, which was found in many splicing factor and is required for interaction with the C-terminal domain of RNA polymerase II and the N-terminal region containing a PPIase domain. The C-terminal domain has a repetitive proline-rich amino acid sequence, and its conformation may be regulated by PPIG. The participation of PPIG in both transcription and splicing provides a good example of the intimate connection between these two cellular processes. PPIL1 may be another example.

In summary, SKIP is a multifunctional protein that is involved in transcription initiation, transcription repression, splicing, and cell cycle (reviewed by Fold et al. (16)). It interacts extensive partners such as the VDR/RXR heterodimer, Ski, Samd 2/3, MyoD, CBF1, NcoR/SMRT, PPIL1, pRb, SNIP1, and others (16, 40). Romero et al. (52) reported that the 398–521 fragment of the SKIP ortholog SNWA is one of the strongest predicted disorder protein regions that utilize the neural network. Here, we demonstrated that another fragment of human SKIP172 (residues 1–172) is an intrinsically disordered region. Upon binding to one partner, PPIL1, SKIP undergoes disorder-order transition. Structural plasticity of SKIP is especially important for interactions with multiple partners.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. M. C. Bewley for suggestions about writing, Dr. Y. S. Yang for useful suggestions, Dr. Z. F. Luo for the assistance with the surface plasmon resonance experiments, and Dr. Y. W. Ding for the assistance with the DSC experiments. We thank Prof. T. D. Goddard and D. G. Kneller for providing Sparky and Dr. R. Koradi and Prof. K. Wüthrich for providing Molmol.

This work was supported by the Chinese National Fundamental Research Project (Grants 2006CB806507, 2006CB910201, 2002CB713806, and 2006AA02A315) and the Chinese National Natural Science Foundation (Grants 30121001, 30570361, and 30830031).

The atomic coordinates and structure factors (code 2K7NM) have been deposited in the Protein Data Bank, Research Collaboratory for Structural Bioinformatics, Rutgers University, New Brunswick, NJ (http://www.rcsb.org/).

The on-line version of this article (available at http://www.jbc.org) contains supplemental Figs. S1 and S2 and Tables S1–S3.

- snRNP

- small nuclear ribonucleoprotein

- DSC

- differential scanning calorimetry

- PPIL1

- peptidylprolyl isomerase-like protein 1

- SKIP

- Ski interaction protein

- SKIPN

- the N-terminal of SKIP (aa 59–129)

- PBF

- PPIL1-binding domain of SKIP (aa 59–79)

- PPIase

- peptidylprolyl cis/trans-isomerase

- Ni-NTA

- nickel-nitrilotriacetic acid

- TROSY

- transverse relaxation-optimized spectroscopy

- NOE

- nuclear Overhauser effect

- NOESY

- NOE spectroscopy

- CSI

- chemical shift index

- HIV-1

- human immunodeficiency virus, type 1

- r.m.s.

- room mean square

- aa

- amino acid(s)

- PPIG

- peptidylprolyl isomerase G.

REFERENCES

- 1.Staley J. P., Guthrie C. (1998) Cell 92, 315–326 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jurica M. S., Moore M. J. (2003) Mol. Cell 12, 5–14 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wahl M. C., Will C. L., Lührmann R. (2009) Cell 136, 701–718 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Konarska M. M., Vilardell J., Query C. C. (2006) Mol. Cell 21, 543–553 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Behzadnia N., Golas M. M., Hartmuth K., Sander B., Kastner B., Deckert J., Dube P., Will C. L., Urlaub H., Stark H., Lührmann R. (2007) EMBO J. 26, 1737–1748 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Deckert J., Hartmuth K., Boehringer D., Behzadnia N., Will C. L., Kastner B., Stark H., Urlaub H., Lührmann R. (2006) Mol. Cell. Biol. 26, 5528–5543 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bessonov S., Anokhina M., Will C. L., Urlaub H., Lührmann R. (2008) Nature 452, 846–850 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Makarov E. M., Makarova O. V., Urlaub H., Gentzel M., Will C. L., Wilm M., Lührmann R. (2002) Science 298, 2205–2208 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Makarova O. V., Makarov E. M., Urlaub H., Will C. L., Gentzel M., Wilm M., Lührmann R. (2004) EMBO J. 23, 2381–2391 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gouet P., Courcelle E., Stuart D. I., Métoz F. (1999) Bioinformatics 15, 305–308 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mintz P. J., Patterson S. D., Neuwald A. F., Spahr C. S., Spector D. L. (1999) EMBO J. 18, 4308–4320 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zhang C., Dowd D. R., Staal A., Gu C., Lian J. B., van Wijnen A. J., Stein G. S., MacDonald P. N. (2003) J. Biol. Chem. 278, 35325–35336 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nagai K., Yamaguchi T., Takami T., Kawasumi A., Aizawa M., Masuda N., Shimizu M., Tominaga S., Ito T., Tsukamoto T., Osumi T. (2004) Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 316, 512–517 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Albers M., Diment A., Muraru M., Russell C. S., Beggs J. D. (2003) RNA 9, 138–150 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Diehl B. E., Pringle J. R. (1991) Genetics 127, 287–298 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Folk P., Půta F., Skruzný M. (2004) Cell Mol. Life Sci. 61, 629–640 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Xu C., Zhang J., Huang X., Sun J., Xu Y., Tang Y., Wu J., Shi Y., Huang Q., Zhang Q. (2006) J. Biol. Chem. 281, 15900–15908 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Skruzný M., Ambrozková M., Fuková I., Martínková K., Blahůsková A., Hamplová L., Půta F., Folk P. (2001) Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1521, 146–151 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Aiyar A., Leis J. (1993) BioTechniques 14, 366–369 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Panchal S. C., Bhavesh N. S., Hosur R. V. (2001) J. Biomol. NMR 20, 135–147 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wishart D. S., Sykes B. D. (1994) J. Biomol. NMR 4, 171–180 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Herrmann T., Güntert P., Wüthrich K. (2002) J. Mol. Biol. 319, 209–227 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Brünger A. T., Adams P. D., Clore G. M., DeLano W. L., Gros P., Grosse-Kunstleve R. W., Jiang J. S., Kuszewski J., Nilges M., Pannu N. S., Read R. J., Rice L. M., Simonson T., Warren G. L. (1998) Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 54, 905–921 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Linge J. P., Williams M. A., Spronk C. A., Bonvin A. M., Nilges M. (2003) Proteins 50, 496–506 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jung J. W., Yee A., Wu B., Arrowsmith C. H., Lee W. (2005) J. Biochem. Mol. Biol. 38, 550–554 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Schwarzinger S., Kroon G. J., Foss T. R., Wright P. E., Dyson H. J. (2000) J. Biomol. NMR 18, 43–48 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Schwarzinger S., Kroon G. J., Foss T. R., Chung J., Wright P. E., Dyson H. J. (2001) J. Am. Chem. Soc. 123, 2970–2978 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Delaglio F., Grzesiek S., Vuister G. W., Zhu G., Pfeifer J., Bax A. (1995) J. Biomol. NMR 6, 277–293 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Farrow N. A., Muhandiram R., Singer A. U., Pascal S. M., Kay C. M., Gish G., Shoelson S. E., Pawson T., Forman-Kay J. D., Kay L. E. (1994) Biochemistry 33, 5984–6003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Greenfield N. J. (2006) Nat. Protoc. 1, 2876–2890 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Venyaminov S. Yu., Baikalov I. A., Shen Z. M., Wu C. S., Yang J. T. (1993) Anal. Biochem. 214, 17–24 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kelly S. M., Jess T. J., Price N. C. (2005) Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1751, 119–139 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kay L. E., Torchia D. A., Bax A. (1989) Biochemistry 28, 8972–8979 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Donne D. G., Viles J. H., Groth D., Mehlhorn I., James T. L., Cohen F. E., Prusiner S. B., Wright P. E., Dyson H. J. (1997) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 94, 13452–13457 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Saha R. P., Bahadur R. P., Pal A., Mandal S., Chakrabarti P. (2006) BMC Struct. Biol. 6, 11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Chakrabarti P., Janin J. (2002) Proteins 47, 334–343 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Dahl R., Wani B., Hayman M. J. (1998) Oncogene 16, 1579–1586 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Baudino T. A., Kraichely D. M., Jefcoat S. C., Jr., Winchester S. K., Partridge N. C., MacDonald P. N. (1998) J. Biol. Chem. 273, 16434–16441 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ambrozková M., Půta F., Fuková I., Skruzný M., Brábek J., Folk P. (2001) Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 284, 1148–1154 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bracken C. P., Wall S. J., Barré B., Panov K. I., Ajuh P. M., Perkins N. D. (2008) Cancer Res. 68, 7621–7628 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kim Y. J., Noguchi S., Hayashi Y. K., Tsukahara T., Shimizu T., Arahata K. (2001) Hum. Mol. Genet 10, 1129–1139 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Chan S. P., Kao D. I., Tsai W. Y., Cheng S. C. (2003) Science 302, 279–282 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Reidt U., Wahl M. C., Fasshauer D., Horowitz D. S., Lührmann R., Ficner R. (2003) J. Mol. Biol. 331, 45–56 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Haynes C., Iakoucheva L. M. (2006) Nucleic Acids Res. 34, 305–312 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Mesa A., Somarelli J. A., Herrera R. J. (2008) FEBS Lett. 582, 2345–2351 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Horowitz D. S., Lee E. J., Mabon S. A., Misteli T. (2002) EMBO J. 21, 470–480 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Pandit S., Wang D., Fu X. D. (2008) Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 20, 260–265 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Proudfoot N. J., Furger A., Dye M. J. (2002) Cell 108, 501–512 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.MacDonald P. N., Dowd D. R., Zhang C., Gu C. (2004) J. Steroid Biochem. Mol. Biol. 89–90, 179–186 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Brès V., Gomes N., Pickle L., Jones K. A. (2005) Genes Dev. 19, 1211–1226 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Bourquin J. P., Stagljar I., Meier P., Moosmann P., Silke J., Baechi T., Georgiev O., Schaffner W. (1997) Nucleic Acids Res. 25, 2055–2061 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Romero P., Obradovic Z., Kissinger C. R., Villafranca J. E., Garner E., Guilliot S., Dunker A. K. (1998) Pac. Symp. Biocomput. 3, 437–448 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Thompson J. D., Higgins D. G., Gibson T. J. (1994) Nucleic Acids Res. 22, 4673–4680 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.