Abstract

Metallo-β-lactamases (MβLs) stand as one of the main mechanisms of bacterial resistance toward carbapenems. The rational design of an inhibitor for MβLs has been limited by an incomplete knowledge of their catalytic mechanism and by the structural diversity of their active sites. Here we show that the MβL GOB from Elizabethkingia meningoseptica is active as a monometallic enzyme by using different divalent transition metal ions as surrogates of the native Zn(II) ion. Of the metal derivatives in which Zn(II) is replaced, Co(II) and Cd(II) give rise to the most active enzymes and are shown to occupy the same binding site as the native ion. However, Zn(II) is the only metal ion capable of stabilizing an anionic intermediate that accumulates during nitrocefin hydrolysis, in which the C–N bond has already been cleaved. This finding demonstrates that the catalytic role of the metal ion in GOB is to stabilize the formation of this intermediate prior to nitrogen protonation. This role may be general to all MβLs, whereas nucleophile activation by a Zn(II) ion is not a conserved mechanistic feature.

Keywords: Enzymes/Mechanisms, Enzymes/Metallo, Antibiotics, Drug Resistance, Zinc, GOB, Catalysis, Metal Substitution, Metallo-beta-lactamase, Reaction Intermediate

Introduction

The expression of β-lactam-degrading enzymes (β-lactamases) is the most common mechanism of antibiotic resistance among bacteria (1, 2). These enzymes have been grouped into four classes (A–D) according to sequence homology (3, 4). Class A, C, and D enzymes use an active site serine residue as a nucleophile, whereas class B lactamases (generically termed metallo-β-lactamases (MβLs)3) employ one or two Zn(II) ions to cleave the β-lactam ring (1–10).

MβLs have particular importance in the clinical setting in that they can hydrolyze a broader spectrum of β-lactam substrates (including carbapenems) than the serine-type enzymes and are resistant to most clinically employed inhibitors (5–10). The design of an efficient pan-MβL inhibitor has been mostly limited by a striking diversity in the active site structures, catalytic profiles, and metal ion requirements for activity among different enzymes. Based on this heterogeneity, MβLs have been classified into three subclasses: B1, B2, and B3 (3). Subclass B1 includes several chromosomally encoded enzymes, such as BcII from Bacillus cereus (11–13), CcrA from Bacteroides fragilis (14–17), BlaB from Elizabethkingia meningoseptica (18), and transferable VIM (19), IMP (20, 21), SPM (22), and GIM (23) type enzymes. Subclass B2 includes the CphA (24, 25) and ImiS (26) lactamases from Aeromonas species and Sfh-I from Serratia fonticola (27). Subclass B3, originally represented only by L1 from Stenotrophomonas maltophilia (28–30), now includes enzymes from other opportunistic pathogens like FEZ-1 from Legionella gormanii (31) and GOB from E. meningoseptica (32, 33) as well as from environmental bacteria, such as CAU-1 from Caulobacter crescentus (34) and THIN-B from Janthinobacterium lividum (35).

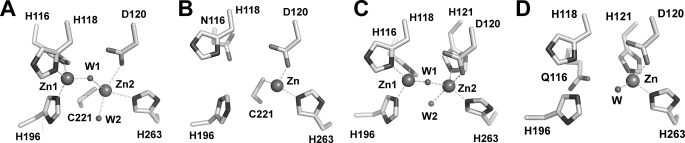

Molecular structures of MβLs from the three subclasses have been solved by x-ray crystallography (11, 13, 14, 24, 28, 31). Comparison of their structures reveals a common αβ/βα sandwich fold, in which diverse insertions and deletions have resulted in different loop topologies and, ultimately, in different zinc coordination environments and metal site occupancies (Fig. 1). MβLs bind up to two metal ions in their active sites. In B1 and B3 enzymes, Zn1 is tetrahedrally coordinated to three histidine ligands (His116, His118, and His196 in Fig. 1, A and C) and a water/OH− molecule (3H site), which is the attacking nucleophile (13, 14, 28, 31). The coordination polyhedron of Zn2 in B1 enzymes is provided by Asp120, Cys221, His263, and one or two water molecules (DCH site) (Fig. 1A) (13, 14). Notably, this site constitutes the active species in mono-Zn(II) B2 enzymes (Fig. 1B) (24). Instead, two mutations (C221S and R121H) affect the Zn2 coordination geometry in B3 MβLs, and the metal ion is now bound to Asp120, His121, His263, and one or two water molecules, whereas Ser221 is no longer a metal ligand (DHH site) (Fig. 1C) (28, 31). A remarkable exception is constituted by the deepest branching member of the MβL B3 subclass, GOB from E. meningoseptica (4). In all reported GOB sequences, His116 and Ser221 are substituted by Gln and Met, respectively, suggesting the presence of an unusually perturbed metal binding site within this subclass.

FIGURE 1.

Metallo-β-lactamase metal binding sites. A, dinuclear B1 MβL BcII from B. cereus (Protein Data Bank code 1bc2) (13); B, mononuclear B2 MβL CphA from Aeromonas hydrophila (Protein Data Bank code 1x8g) (24); C, dinuclear B3 MβL L1 from S. maltophilia (Protein Data Bank code 1sml) (28); D, molecular model for the mononuclear B3 MβL GOB-18 from E. meningoseptica (33). Zinc atoms are shown as large gray spheres, and water molecules (W) are shown as small gray spheres. Coordination bonds are shown as dashed lines.

We have recently reported a biochemical and biophysical characterization of GOB-18 (33). In contrast to all known MβLs, GOB-18 is fully active against a broad range of β-lactam substrates using a single Zn(II) ion. Based on spectroscopic, mutagenesis, and modeling experiments, we already proposed that the Zn(II) ion is bound to Asp120, His121, His263, and one or two solvent molecule(s) (i.e. in the canonical Zn2 site of dinuclear MβLs) (Fig. 1D).

These findings are puzzling because, although it is accepted that B2 lactamases may work without a metal-activated nucleophile (24, 36), this is not the case for B3 lactamases (37). A crystal structure of mono-Zn(II) L1 has revealed that the single metal ion is located in the 3H site (i.e. the one involved in nucleophile activation) (38). A recent kinetic and spectroscopic study in L1 has also indicated that mono-Zn(II) L1 in solution is active with the metal ion localized in the 3H site (37). Thus, there is no precedent of a B3 lactamase without a metal-activated nucleophile. The absence of a crystal structure for GOB has precluded a possible description of the role of the metal site in this enzyme, which is still unclear. Here we report a series of experiments that allow us to propose that the metal site in GOB is involved in stabilization of an anionic intermediate that accumulates during catalysis, thus favoring C–N bond cleavage after the nucleophilic attack. These results are unprecedented because these intermediates have been only identified in catalysis by dinuclear lactamases (16, 17, 37, 39) and disclose the existence of a common catalytic feature in MβLs from all subclasses.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Chemicals

All reagents were purchased from Sigma with the exception of the NAP-10 gel filtration column purchased from Amersham Biosciences. Metal-free buffers were prepared adding Chelex 100 (Sigma) to normal buffers and stirring for 0.5 h.

GOB-18 and D120S GOB-18 Expression and Purification

This was performed as previously described (33), employing plasmid pET9a-GOB-18 or pET9a-D120S GOB-18 and Escherichia coli BL21 (DE3) Codon Plus RIL as the bacterial host. Protein purity was higher than 95% as determined by SDS-PAGE and Coomassie staining. Protein concentration was determined spectrophotometrically employing ϵ280 = 32,200 m−1 cm−1.

Metal Substitution

Apo-GOB-18 was generated as previously described (33), and metal removal was corroborated by atomic absorption spectroscopy. Zn(II)-GOB-18 was prepared by dialyzing 50–100 μm apo-GOB-18 against 300 volumes of buffer (15 mm Hepes, pH 7.5, 200 mm NaCl containing ZnSO4 at a concentration equal to the protein concentration in the dialysis bag). Zn(II)-D120S GOB-18, Co(II)-GOB-18, Co(II)-D120S GOB-18, Ni(II)-GOB-18, Ni(II)-D120S GOB-18, Cd(II)-GOB-18, and Cd(II)-D120S GOB-18 were instead generated by dialyzing 50–100 μm apo-GOB-18 or apo-D120S GOB-18 against 300 volumes of buffer (15 mm Hepes, pH 7.5, 200 mm NaCl containing ZnSO4, CoSO4, NiCl2, or CdCl2, respectively, at a concentration equivalent to 5 times the protein concentration in the dialysis bag). Excess metal was then removed by a second dialysis with 500 volumes of metal-free buffer. All dialysis steps (8–12 h each) were run at 4 °C.

Metal Content Determination

Metal content determinations were performed by atomic absorption spectroscopy using a Metrolab 250 instrument operating in the flame mode.

Non-steady-state Kinetics

Nitrocefin hydrolysis catalyzed by different GOB-18 metal variants was followed, employing a Jasco V-550 spectrophotometer for slow reactions and an SX.18-MVR stopped-flow spectrometer associated with a PD.1 photodiode array (Applied Photophysics, Surrey, UK) or an absorbance photomultiplier for fast reactions. All measurements were performed in metal-free buffer (100 mm Hepes, pH 7.5, 200 mm NaCl). Reaction temperature was 30 °C for all GOB-18 metal variants with the exception of Zn(II)-GOB-18, where the reaction temperature was 4 °C. Enzyme and substrate concentrations were adjusted to 10–30 and 5–15 μm, respectively, to attain single turnover conditions. Nonlinear regression analysis was used to fit single-wavelength absorbance changes with the program Dynafit (40). Groups of data corresponding to hydrolysis of nitrocefin were fitted simultaneously. The molar extinction coefficients of nitrocefin used were as follows: substrate ϵ390 = 18,400 m−1 cm−1; product ϵ390 = 6,300 m−1 cm−1, ϵ490 = 17,400 m−1 cm−1, ϵ665 = 500 m−1 cm−1. Steady-state kinetic parameters for the hydrolysis of nitrocefin were calculated as kcat = k2k3/(k2 + k3) and Km = k3(k−1 + k2)/k1(k2 + k3) for Zn(II)-GOB-18 and kcat = k2 and Km = (k−1 + k2)/k1 for all other GOB-18 metal variants.

Steady-state Kinetics

All reactions were performed at 30 °C in buffer (15 mm Hepes, pH 7.5, 200 mm NaCl). Antibiotic hydrolysis was monitored following the absorbance variation resulting from the hydrolysis of the β-lactam ring, using the following extinction coefficients: imipenem, Δϵ300 = −9,000 m−1 cm−1; penicillin G, Δϵ235 = −800 m−1 cm−1; cefotaxime, Δϵ260 = −7,500 m−1 cm−1. The kinetic parameters kcat and Km were derived from nonlinear fit of the Michaelis-Menten equation to initial rate measurements recorded on a Jasco V-550 spectrophotometer. In each case, kcat values have been calculated taking into account the concentration of metallated mononuclear enzyme.

Circular Dichroism

Measurements were performed at 25 °C, using a Jasco J-715 spectropolarimeter flushed with N2. Samples were prepared dialyzing the corresponding protein solution against 300 volumes of buffer 10 mm Tris-HCl, pH 7, 50 mm NaCl, twice for 8–12 h, at 4 °C.

NMR Spectroscopy

NMR spectra were recorded at 298 K on a Bruker Avance II 600 spectrometer operating at 600.13 MHz. 1H NMR paramagnetic spectra were acquired under conditions to optimize detection of the fast relaxing isotropically shifted resonances, either using the superWEFT pulse sequence (41) or water presaturation. These spectra were recorded over large spectral widths with acquisition times ranging from 16 to 80 ms and intermediate delays from 2 to 35 ms. 1H NMR spectra in the diamagnetic envelope were obtained employing a selective shaped pulse for solvent saturation (42). Hydrodynamic radius determination by pulsed field gradient 1H NMR was performed according to Ref. 43. A 113Cd NMR experiment was performed at 133 MHz, with a 5-mm reverse broad band probe. About 260,000 free induction decays were recorded, acquiring 32,768 complex points in 100 ms, with a 30° observe pulse (4 s), a spectral width of 160,000 Hz (1,200 ppm), and a relaxation delay of 0.5 s. The external reference was Cd(ClO4)2.

Electronic Absorption Spectroscopy

UV-visible spectra were recorded on a Jasco V-550 spectrophotometer at 25 °C. Samples were in buffer (15 mm Hepes, pH 7.5, 200 mm NaCl).

111mCd(II) PAC Spectroscopy

The experiment was performed employing a setup with six BaF2 detectors. Radioactive 111mCd was produced on the day of the experiments by the Cyclotron Department at the University Hospital in Copenhagen. Preparation and purification of 111mCd were as previously described (44). A 25-μl 111mCd-containing solution was mixed with non-radioactive cadmium acetate and buffer (Hepes and NaCl; see final concentrations below). pH was adjusted to 7.5 at room temperature. Apo-GOB-18 in 15 mm Hepes, pH 7.5, 200 mm NaCl was added at a final enzyme concentration of 40 μm, and pH was adjusted to 7.5 at room temperature. The total volume of the sample was 750 μl. Sample was then left 2 h at room temperature to allow binding of Cd(II) to the protein and subsequently run through a gel filtration column (NAP10), using 15 mm Hepes, pH 7.5, 200 mm NaCl as eluent. 111mCd-containing protein fractions were pooled (four fractions with a volume of 250 μl each). The sample was frozen in liquid nitrogen and placed in the PAC instrument, where the temperature was set to −20 °C and controlled by a Peltier element. Fits to PAC data were carried out with 300 data points, disregarding the first five points due to systematic errors in these. The analytical expression for the perturbation function is known, and five parameters are fitted for each nuclear quadrupole interaction (45). In radiotracer (109Cd) experiment condition were the same as for PAC experiments.

RESULTS

Nitrocefin Hydrolysis by Zn(II)-GOB-18 Proceeds by Means of an Anionic Intermediate

Nitrocefin, a synthetic cephalosporin, has been extensively employed as a chromogenic probe of the mechanism of MβLs. Benkovic and co-workers (16, 17) reported for the first time the accumulation of a reaction intermediate in the hydrolysis of nitrocefin by the B1 enzyme CcrA from B. fragilis. The same intermediate was also reported for the B3 enzyme L1 (37, 46) and for an evolved mutant of the B1 lactamase BcII (39). In all cases, this intermediate was stabilized exclusively by the dinuclear forms of these enzymes.

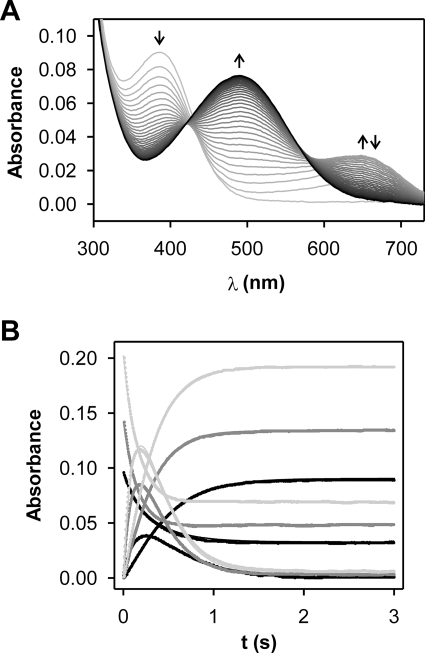

We studied the hydrolysis of nitrocefin catalyzed by mono Zn(II)-GOB-18 employing a stopped-flow equipment coupled to a photodiode array. Besides the decay of the substrate absorption at 390 nm and the rise of the product absorption at 490 nm, the sequence of electronic absorption spectra obtained clearly shows the accumulation and the decay of a species with an intense absorption band centered at 665 nm, identical to the one reported for the anionic intermediate previously observed for dinuclear enzymes (Fig. 2A).

FIGURE 2.

Non-steady-state nitrocefin hydrolysis catalyzed by Zn(II)-GOB-18. A, sequence of electronic absorption spectra of 4.5 μm nitrocefin upon the reaction with 9.3 μm Zn(II)-GOB-18 obtained employing a stopped-flow equipment coupled to a photo diode array. The reaction progresses from gray to black spectra. B, time evolution of absorbance at 390, 490, and 665 nm upon reaction of 1) 5.2 μm nitrocefin with 14.1 μm Zn(II)-GOB-18 (black); 2) 7.7 μm nitrocefin with 28.9 μm Zn(II)-GOB-18 (dark gray), and 3) 11 μm nitrocefin with 28.9 μm Zn(II)-GOB-18 (light gray). In each case, 600 points were recorded on a linear time scale over 3 s. Fits to the kinetic model in Scheme 1 overlay experimental points. Parameters obtained from the global fit of data were as follows: k+1 = 4.8 ± 0.4 s−1 μm−1; k−1 = 260 ± 20 s−1; k2 = 14.1 ± 0.2 s−1; k3 = 6.43 ± 0.02 s−1; ϵEI = 35,000 ± 2,000 m−1 cm−1. Measurements were performed in 100 mm Hepes, pH 7.5, 200 mm NaCl, at 4 °C.

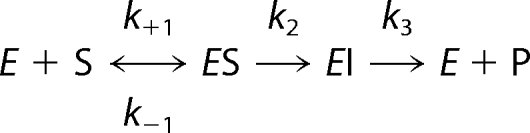

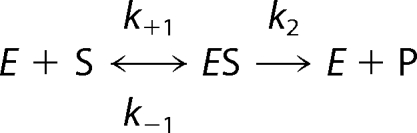

In order to obtain a minimal kinetic mechanism for the UV-visible data, we performed similar experiments with different amounts of nitrocefin and enzyme measuring the evolution of the absorbance at 390, 490, and 665 nm (Fig. 2B). Data were then subjected to simultaneous global fit. The kinetic model that fits the experimental data best is as follows.

|

The individual kinetic constants obtained were employed to calculate kcat = 4.4 ± 0.1 s−1 and Km = 18 ± 3 μm as described under “Experimental Procedures.” These values compare very well with the steady-state kinetic parameters determined under the same experimental conditions: kcat = 4.0 ± 0.3 s−1 and Km = 25 ± 5 μm, strongly supporting the proposed model.

The finding of a reaction intermediate in mononuclear Zn(II)-GOB-18 similar to that reported for dinuclear enzymes suggests that the Zn2 ion is involved in its stabilization in all cases. To further explore the role of this metal ion, we decided to probe the mechanism of nitrocefin hydrolysis by GOB-18 substituted with a variety of transition divalent metal ions.

Nitrocefin Hydrolysis by M(II)-GOB-18 Derivatives

Cytoplasmic overexpression of GOB-18 in E. coli gives rise to a mixture of the Fe(III) and Zn(II) variants (33). We have already optimized a procedure for metal depletion (33). The apoprotein can then be fully loaded with metal ions by dialysis (see “Experimental Procedures”). We have now prepared different metal derivatives (referred to as M(II)-GOB-18 hereafter) using Co(II), Ni(II), and Cd(II) as surrogates of the native Zn(II) ion. The metal content of each M(II)-GOB-18 variant was determined by atomic absorption spectroscopy. Similar values were obtained for several protein preparations. The metal content of the different M(II)-GOB-18 derivatives never exceeded 1 eq per protein molecule in agreement with the metal content of the native enzyme (Table 1).

TABLE 1.

Metal content of GOB-18 variants as determined by atomic absorption spectroscopy

The presented values correspond to the average of at least three independent protein preparations. Deviations from the presented values never exceeded 15%.

| GOB-18 variant | Metal equivalents |

|---|---|

| Zn(II)-GOB-18 | 0.97 |

| Co(II)-GOB-18 | 0.72 |

| Ni(II)-GOB-18 | 0.83 |

| Cd(II)-GOB-18 | 0.77 |

In order to determine the essentiality of the Zn(II) ion in the stabilization of the anionic intermediate in the hydrolysis of nitrocefin by GOB-18 and to explore the mechanistic changes induced by the metal replacements, reactions catalyzed by the different M(II)-GOB-18 derivatives were studied similarly to those above described for the native Zn(II) enzyme. Two major facts result from these experiments: 1) the intermediate is not accumulated in the reaction catalyzed by M(II)-GOB-18 derivatives as detected by Zn(II)-GOB-18 (direct conversion of substrate to product was observed in all cases; see supplemental Fig. S1), and 2) all M(II)-GOB-18 derivatives are less active than Zn(II)-GOB-18, and among these the Co(II) variant displays higher levels of nitrocefinase activity than the Cd(II) and Ni(II) derivatives.

In each case, single wavelength traces corresponding to substrate depletion and product formation were globally fit to the model presented in Scheme 2 (supplemental Fig. S1). Kinetic constants obtained are summarized in supplemental Table S1.

|

The fact that there is no accumulation of the anionic intermediate in the hydrolysis of nitrocefin catalyzed by GOB-18 metal variants other than the Zn(II) native one may be interpreted as an inherent inability of the metal ions to stabilize the intermediate or as a different binding of these ions to the protein. To explore these hypotheses, we employed different spectroscopic techniques to ascertain the coordination sphere of the M(II)-GOB-18 derivatives.

Spectroscopic and Functional Study of M(II)-GOB-18 Derivatives

We exploited the features of the employed metal ions as spectroscopic probes of their coordination spheres. High spin Co(II) and high spin Ni(II) can be employed as paramagnetic probes to identify the metal ligands by following their effect on the 1H NMR spectrum of the protein. Cd(II) can be directly interrogated by NMR and PAC spectroscopy.

We tested the activity of Co(II)-GOB-18, Ni(II)-GOB-18, and Cd(II)-GOB-18 against a series of clinically relevant substrates (penicillin G, cefotaxime, and imipenem). The corresponding steady-state kinetic parameters are summarized and compared with those of Zn(II)-GOB-18 in Table 2. The general activity trend is Zn(II) > Cd(II), Co(II) > Ni(II) (in all cases, the addition of 20 μm metal ion to the reaction medium did not improve the catalytic efficiency). Remarkably, the catalytic efficiencies of M(II)-GOB-18 derivatives were mainly affected in the kcat values as compared with the native enzyme. The kcat values for Cd(II), Co(II), and Ni(II)-GOB-18 decreased by ∼3-fold, 10-fold, and ∼100-fold, respectively, compared with those corresponding to Zn(II)-GOB-18. Instead, Km values for each substrate were within the same order of magnitude for the different assayed metal ions.

TABLE 2.

Steady-state kinetic parameters for the hydrolysis of different β-lactam substrates by GOB-18 variants

Kinetic parameters were derived from nonlinear fit of the Michaelis-Menten equation to initial rate measurements. The reaction medium was 15 mm Hepes, pH 7.5, 200 mm NaCl, at 30 °C. The presented values correspond to the average of at least three independent enzyme preparations.

| Substrate | Penicillin G | Cefotaxime | Imipenem |

|---|---|---|---|

| Zn(II) | |||

| kcat (s−1) | 700 ± 100 | 40 ± 10 | 34 ± 4 |

| Km (μm) | 360 ± 80 | 40 ± 9 | 28 ± 9 |

| kcat/Km (s−1 μm−1) | 1.9 ± 0.4 | 1.1 ± 0.2 | 1.3 ± 0.4 |

| Co(II) | |||

| kcat (s−1) | 130 ± 10 | 5.8 ± 0.3 | 3.3 ± 0.2 |

| Km (μm) | 300 ± 100 | 33 ± 5 | 26 ± 6 |

| kcat/Km (s−1 μm−1) | 0.4 ± 0.1 | 0.18 ± 0.03 | 0.13 ± 0.03 |

| Ni(II) | |||

| kcat (s−1) | 2.5 ± 0.3 | 0.67 ± 0.07 | 2.0 ± 0.2 |

| Km (μm) | 230 ± 20 | 30 ± 3 | 72 ± 7 |

| kcat/Km (s−1 μm−1) | 0.011 ± 0.003 | 0.022 ± 0.006 | 0.029 ± 0.006 |

| Cd(II) | |||

| kcat (s−1) | 260 ± 30 | 17 ± 2 | 6.2 ± 0.4 |

| Km (μm) | 580 ± 80 | 32 ± 9 | 50 ± 10 |

| kcat/Km (s−1 μm−1) | 0.5 ± 0.1 | 0.5 ± 0.1 | 0.12 ± 0.02 |

We recorded circular dichroism and 1H NMR spectra of M(II)-GOB-18 derivatives as well as those of apo and Zn(II)-GOB-18 in order to probe their correct folding (see supplemental Fig. S2). CD spectra in the far UV range are similar, with some minor differences in the case of apo-GOB-18. However, the CD spectra in the near UV region suggest a reduced level of tertiary structure in apo-GOB-18 as compared with the metallated forms. Also, the signals in the 1H NMR spectrum of apo-GOB-18 show less dispersion than for any of the metallated variants (see supplemental Fig. S2), suggesting that (despite showing secondary structure) apo-GOB-18 does not adopt the native conformation. The hydrodynamic radii of apo-GOB-18 and Zn(II)-GOB-18 were determined by pulse field gradient 1H NMR spectroscopy, resulting in values of 29 ± 1 and 23.1 ± 0.5 Å, respectively, confirming that apo-GOB-18 adopts a more extended conformation than the metallated protein.

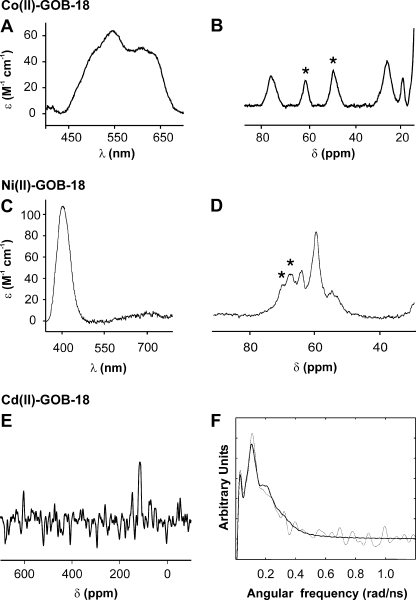

Fig. 3A shows the electronic absorption spectrum of Co(II)-GOB-18. The transitions observed in the visible range correspond to Laporte forbidden d-d (or ligand field) electronic transitions of the Co(II) ion bound to the protein. The molar extinction coefficient of these bands (50–60 m−1 cm−1) is consistent with a pentacoordinated Co(II) ion (47). The spectral features observed resemble those of mononuclear Co(II)-L1 with the metal ion localized in the DHH site (37). A 1H NMR spectrum of Co(II)-GOB-18 recorded under conditions that allow the detection of paramagnetic signals reveals a set of isotropically shifted resonances spanning from 80 to 20 ppm (Fig. 3B). When the spectrum was recorded in D2O, signals at 60 and 47 ppm were absent, indicating the presence of two solvent-exchangeable resonances that can be attributed to two His ligands. In addition, the low number of signals observed in the paramagnetic region of the spectrum and their dispersion in the chemical shift range is also consistent with a pentacoordinated Co(II) ion (47, 48). The present spectrum shows a larger signal dispersion than that of mononuclear Co(II)-L1 (37).

FIGURE 3.

Co(II)-GOB-18, Ni(II)-GOB-18, and Cd(II)-GOB-18 spectroscopy characterization. A and C, differential electronic absorption spectrum of Co(II)-GOB-18 and Ni-GOB-18, respectively, minus apo-GOB-18. Samples were in 15 mm Hepes, pH 7.5, 200 mm NaCl. Measurements were performed at 25 °C. B and D, Co(II)-GOB-18 and Ni(II)-GOB-18 1H NMR spectra. Protein concentration was 1 mm. Samples were in 15 mm Hepes, pH 7.5, 200 mm NaCl, 10% D2O. Measurements were performed at 298 K. Signals (*) were no longer detected in D2O medium. Spectra were processed employing a 120-Hz line broadening. E, 113Cd NMR spectrum of Cd(II)-GOB-18. Protein concentration was 1 mm. The sample was in 15 mm Hepes, pH 7.5, 200 mm NaCl, 10% D2O. The measurement was performed at 298 K. The spectrum was processed employing 800-Hz line broadening. F, 111mCd PAC spectrum of Cd(II)-GOB-18. Fourier transform of the experimental perturbation function (gray line) and the fit (black line). The experiment was carried out at −20 °C, with 40 μm GOB-18 in 15 mm Hepes, pH 7.5 (determined at 25 °C), 100 mm NaCl, 2 eq of Cd(II) (see “Experimental Procedures” for the exact protocol).

Fig. 3C shows the electronic absorption spectrum of Ni(II)-GOB-18. The signals observed in the visible range correspond to ligand field electronic transitions of the Ni(II) ion bound to the protein. The spectrum resembles that of Ni(II)-carboxypeptidase A, which contains a single hexacoordinated metal ion (49). The 1H NMR spectrum of Ni(II)-GOB-18 reveals a set of isotropically shifted resonances spanning from 70 to 50 ppm (Fig. 3D). When the spectrum was recorded in D2O, the signals at 70 and 67 ppm were no longer detected, indicating the presence of two exchangeable resonances that can be attributed to two His ligands. The chemical shifts of this variant resemble those reported for Ni(II)-carboxypeptidase A (50). This observation, together with the absence of signals experiencing pseudocontact shifts, supports the hypothesis of a pseudo-octahedral Ni(II) site (50).

The 113Cd NMR spectrum of 113Cd(II)-GOB-18 shows only one signal (Fig. 3E) at 115 ppm, revealing only one metal binding site. Besides, the chemical shift of the observed signal is consistent with a coordination sphere containing nitrogen and oxygen donor atoms. 113Cd(II) resonances in proteins with a mixed N/O coordination sphere are usually found between 300 and 40 ppm, O being the most shielding donor atom (51). On the other hand, each sulfur donor present at a 113Cd(II) binding site is so deshielding that it is possible to use chemical shifts to determine the number of sulfur donor atoms at an unknown site (51). Resonances of 113Cd(II)-BcII have been reported at 262 and 142 ppm, which have been attributed to the metal ion bound to sites DCH and D3H, respectively, differing significantly from the resonance here reported (52, 53). The 115 ppm resonance observed for 113Cd(II)-GOB-18 agrees well with experimental 113Cd NMR data giving a resonance at 120 ppm for carboxypeptidase A (54), presumably with a N2O3 coordination sphere (two histidines, one water, and a bidentate carboxylate) and also with theoretical predictions (55).

Fig. 3F shows the 111mCd(II) PAC spectroscopic data recorded for Cd(II)-GOB-18. With 2 eq of Cd(II) added to the protein and an incubation time of 2 h, the PAC signal is found at a relatively low frequency. It can be fit with just one nuclear quadrupole interaction, which would agree with the single resonance observed by 113Cd NMR. Also, only one Cd(II) ion was observed to bind per protein molecule, as demonstrated by a radiotracer experiment using 109Cd(II), where 2 eq of 109Cd(II) were incubated with the protein under the same conditions as applied for the PAC experiment, and a subsequent gel filtration displayed very close to 50% of the radioactivity in the same fractions as the protein. All data from 113Cd NMR, 111mCd PAC, and atomic absorption spectroscopy for the fully metal-loaded protein are thus consistent with one binding site.

The nuclear quadrupole interaction fall in the spectral range expected for ligands coordinating with nitrogen or oxygen atoms. The PAC spectrum obtained from a mixture of 111mCd(II) but not protein in the buffer is very different from the one described above (not shown), indicating that in that case, no free 111mCd(II) was present. Fitted parameters are shown in supplemental Table S2.

M(II)-D120S GOB-18 Derivatives

Spectroscopic data on Co(II)-, Ni(II)-, and Cd(II)-substituted GOB-18 unequivocally point to metal binding to a single site in all M(II)-GOB-18 derivatives. However these data could be compatible with binding to a His2Gln or to a His2Asp site. In order to unequivocally determine the metal binding site in GOB-18 metal derivatives, we obtained the metal-substituted mutant D120S GOB-18, where one of the possible metal binding sites is drastically perturbed. D120S GOB-18 as isolated contained no metal bound and displayed no activity against nitrocefin. Although exhaustive dialysis of this mutant against buffer containing an excess of ZnSO4, CoSO4, NiCl2, or CdCl2 resulted in some extent of metal binding (Table 3), all metal derivatives displayed non-detectable activity against nitrocefin. All D120S GOB-18 metal derivatives were interrogated by CD, showing similar features to those presented for the wild type enzyme (not shown), thus indicating comparable secondary and tertiary structure. These results allow us to unambiguously assign site DHH as the metal binding site in all GOB-18 derivatives.

TABLE 3.

Metal content of Asp120Ser GOB-18 variants as determined by atomic absorption spectroscopy

The presented values correspond to the average of at least three independent measurements. Deviations from the presented values never exceeded 15%.

| D120S GOB-18 variant | Metal equivalents |

|---|---|

| Zn(II)-D120S GOB-18 | 0.44 |

| Co(II)-D120S GOB-18 | 0.50 |

| Ni(II)-D120S GOB-18 | 0.53 |

| Cd(II)-D120S GOB-18 | 0.26 |

DISCUSSION

MβLs represent the largest group of carbapenemases (5–10). The lack of a pan-MβL inhibitor is mostly due to the failure to identify common structural and mechanistic features in enzymes from different organisms, which show a striking diversity in terms of substrate spectrum, active site structure, and metal ion requirements. The Zn(II) ions in MβLs are required for substrate binding and hydrolysis, but the specific role and essentiality of each metal binding site are still subject of intense debate (5–10).

Zn(II) is ubiquitous in nature, being the only metal ion present in enzymes from all six groups in the EC nomenclature (56). This fact highlights its amazing chemical versatility. In the case of MβLs, the Zn(II) ion is able to contribute to β-lactam hydrolysis by 1) lowering the pKa of a bound water molecule, which may act as a nucleophile, providing a high local concentration of hydroxide ions at neutral pH (37, 57); 2) acting as a Lewis acid, polarizing the C=O bond and therefore augmenting the electrophilic nature of the carbonyl carbon (57); and 3) stabilizing a negative charge in the bridging nitrogen of the lactam moiety, after C–N bond cleavage (16, 17, 24, 36, 58, 59). These three roles have been invoked for the two metal binding sites in MβLs, but it is not clear yet which of them are essential for catalysis.

Substrate docking studies to the active site of B1 and B3 lactamases suggest that the attacking nucleophile in the dinuclear forms is the bridging water/OH− ligand (13, 14, 28, 36, 60). This moiety is asymmetrically positioned with respect to the two metal ions, lying closer (1.9–2.1 Å) to the metal ion in the 3H site than to the Zn(II) ion in the DCH or DHH sites (2.1–3.1 Å) (13, 14, 28). The shorter bond length in the former case is consistent with this ligand being a hydroxide and with the idea that the 3H site is responsible for lowering the pKa of a water molecule, thus being responsible for nucleophile activation (57). The role of C=O polarization by this same zinc ion is not supported by QM/MM calculations and by different docking studies, which reveal that the β-lactam bond may not directly bind to the metal ion (60, 61).

The availability of crystal structures of mono-Zn(II) BcII (a B1 enzyme) (11) and L1 (B3) (38) disclosing the presence of one metal ion localized in the preserved 3H site and theoretical studies of substrate binding to mononuclear BcII (62–64) have supported the hypothesis that only this metal site would be essential, delivering the attacking nucleophile. The structure of the mono-Zn(II) B2 enzyme CphA revealed that the only metal ion in this case is bound to the DCH site because one of the His residues of the 3H binding site is replaced by an Asn (24). In this case, the attacking nucleophile has been proposed to be a water molecule that is not activated by a metal ion (24, 36). However, B2 enzymes have been considered as an exception, being limited to few bacteria and performing as exclusive carbapenemases.

The recent report of GOB, a B3 enzyme, which is active as a mononuclear enzyme and is not inhibited by excess Zn(II) (33, 36), provides an excellent opportunity to examine the role of the metal ion in a broad spectrum MβL. Here we have shown that nitrocefin hydrolysis mediated by mono-Zn(II) GOB proceeds via accumulation of an anionic intermediate identical to the one reported by Benkovic and co-workers (16, 17) for a dinuclear B1 enzyme and by Crowder and co-workers (37, 46) for a dinuclear B3 lactamase. Replacement of the native Zn(II) ion by other metal ions, such as Co(II), Ni(II), and Cd(II), gives rise to metal derivatives with disparate catalytic efficiencies and for which accumulation of such an intermediate cannot be detected. We attribute the reduced catalytic efficiencies in Co(II), Ni(II), and Cd(II)-GOB to a less efficient metal-nitrogen interaction in the first step of the reaction, where the C–N bond cleavage is concerted with the nucleophilic attack. QM/MM calculations simulating nitrocefin hydrolysis by a dinuclear B1 enzyme have shown that the metal ion in the Zn2 site plays a significant role in lowering the energetic barrier for C–N bond scission (65), in agreement with this proposal. Different spectroscopic techniques unequivocally show that metal replacement does not affect the identity of the metal binding site (the DHH site), revealing that the Zn(II) ion in the DHH site is essential for the stabilization of this intermediate, which does not require formation of a dinuclear center. Steady-state kinetic data reveal similar Km values for the different GOB-18 variants, suggesting that the metal ions used here for Zn(II) replacement are equally well suited to provide an anchoring site for the substrate carboxylate. These results are in agreement with the finding that Zn(II) is essential for substrate binding in MβLs (66).

The kinetic data of nitrocefin hydrolysis by Co(II), Cd(II), and Ni(II) GOB can also be fit to Scheme 1 by assuming k3 ≫ k2. In this model, k2 reflects the nucleophilic attack in concert with the C–N bond cleavage, the latter being triggered by a metal-nitrogen interaction. We therefore conclude that the reduced k2 values can also be accounted for by a less efficient interaction with the nitrogen atom of the substrate. Another possibility that we cannot fully discard at this point is that the metal site is also involved in nucleophile activation. Nevertheless, QM/MM calculations on B2 enzymes do not support this hypothesis (36).

We have recently shown that second shell mutations in the B1 lactamase BcII obtained by in vitro evolution are able to fine tune the position of the metal ion in the DCH site of this enzyme, stabilizing the nitrocefin intermediate, which is not accumulated in hydrolysis mediated by wild type BcII (39). Here we observe the same phenomenon; subtle changes (such as those that may be induced by metal substitution) determine the stability of this intermediate.

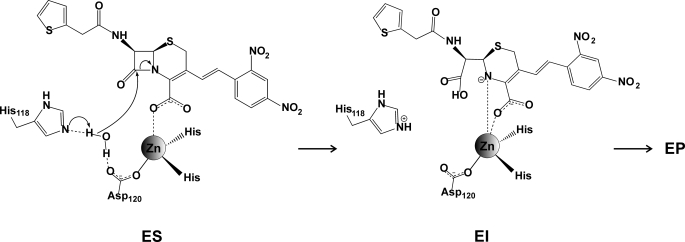

Based on these observations, we propose a β-lactam hydrolysis mechanism for GOB, which does not require a metal-activated nucleophile (Fig. 4). Instead, the role of the metal ion is to steer substrate binding and to provide electrostatic stabilization of the anionic intermediate. This mechanism is in agreement with the proposal that BcII could be active as a mononuclear enzyme with an empty 3H site (67) (i.e. with a requirement of a Zn(II) ion for intermediate stabilization rather than for nucleophile activation (58)), which is formed by shifting of an equilibrium between the two sites (52) upon substrate binding (67).

FIGURE 4.

Nitrocefin hydrolysis mechanism proposed for GOB. ES, enzyme-substrate; EI, enzyme-intermediate; EP, enzyme product.

This conclusion suggests that the positioning of the metal ion at the DCH/DHH site is crucial to define a catalytically active lactamase. This is in excellent agreement with the finding that engineering a more buried position for this metal center seriously impairs the lactamase activity (68), whereas rendering a more substrate-accessible Zn(II) at this site enhances the catalytic efficiency (39). Although nitrocefin is not a clinically useful antibiotic, its usefulness as a probe of the catalytic mechanism of MβLs should not be underestimated. It has been shown recently that carbapenem hydrolysis by a B1 MβL also proceeds by means of an anionic intermediate, after C–N bond cleavage (58). This evidence points to a general role of the Zn(II) ion in the DCH/DHH site of MβL from all subclasses, which may be targeted as a common mechanistic element for inhibitor design.

Supplementary Material

This work was supported by grants from Agencia Nacional de Promoción Científica y Tecnológica and the Howard Hughes Medical Institute (to A. J. V.) and from the Danish Research Council for Nature and Universe (to L. H.). The Bruker Avance II 600-MHz NMR spectrometer was purchased with funds from Agencia Nacional de Promoción Científica y Tecnológica (PME2003-0026) and Consejo Nacional de Investigaciones Científicas y Técnicas (CONICET).

The on-line version of this article (available at http://www.jbc.org) contains supplemental Tables S1 and S2 and Figs. S1 and S2.

- MβL

- metallo-β-lactamase

- PAC

- perturbed angular correlation spectroscopy of γ-rays.

REFERENCES

- 1.Fisher J. F., Meroueh S. O., Mobashery S. (2005) Chem. Rev. 105, 395–424 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Perez F., Endimiani A., Hujer K. M., Bonomo R. A. (2007) Curr. Opin. Pharmacol. 7, 459–469 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Frère J. M., Galleni M., Bush K., Dideberg O. (2005) J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 55, 1051–1053 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hall B. G., Salipante S. J., Barlow M. (2003) J. Mol. Evol. 57, 249–254 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Crowder M. W., Spencer J., Vila A. J. (2006) Acc. Chem. Res. 39, 721–728 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bebrone C. (2007) Biochem. Pharmacol. 74, 1686–1701 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Galleni M., Lamotte-Brasseur J., Rossolini G. M., Spencer J., Dideberg O., Frère J. M. (2001) Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 45, 660–663 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Walsh T. R., Toleman M. A., Poirel L., Nordmann P. (2005) Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 18, 306–325 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cricco J. A., Rasia R. M., Orellano E. G., Ceccarelli E. A., Vila A. J. (1999) Coord. Chem. Rev. 190, 519–535 [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cricco J. A., Vila A. J. (1999) Curr. Pharm. Des. 5, 915–927 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Carfi A., Pares S., Duée E., Galleni M., Duez C., Frère J. M., Dideberg O. (1995) EMBO J. 14, 4914–4921 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Orellano E. G., Girardini J. E., Cricco J. A., Ceccarelli E. A., Vila A. J. (1998) Biochemistry 37, 10173–10180 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fabiane S. M., Sohi M. K., Wan T., Payne D. J., Bateson J. H., Mitchell T., Sutton B. J. (1998) Biochemistry 37, 12404–12411 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Concha N. O., Rasmussen B. A., Bush K., Herzberg O. (1996) Structure 4, 823–836 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yanchak M. P., Taylor R. A., Crowder M. W. (2000) Biochemistry 39, 11330–11339 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wang Z., Fast W., Benkovic S. J. (1998) J. Am. Chem. Soc. 120, 10788–10789 [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wang Z., Fast W., Benkovic S. J. (1999) Biochemistry 38, 10013–10023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.García-Saez I., Hopkins J., Papamicael C., Franceschini N., Amicosante G., Rossolini G. M., Galleni M., Frère J. M., Dideberg O. (2003) J. Biol. Chem. 278, 23868–23873 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Docquier J. D., Lamotte-Brasseur J., Galleni M., Amicosante G., Frère J. M., Rossolini G. M. (2003) J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 51, 257–266 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Materon I. C., Beharry Z., Huang W., Perez C., Palzkill T. (2004) J. Mol. Biol. 344, 653–663 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Toney J. H., Hammond G. G., Fitzgerald P. M., Sharma N., Balkovec J. M., Rouen G. P., Olson S. H., Hammond M. L., Greenlee M. L., Gao Y. D. (2001) J. Biol. Chem. 276, 31913–31918 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Murphy T. A., Catto L. E., Halford S. E., Hadfield A. T., Minor W., Walsh T. R., Spencer J. (2006) J. Mol. Biol. 357, 890–903 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Castanheira M., Toleman M. A., Jones R. N., Schmidt F. J., Walsh T. R. (2004) Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 48, 4654–4661 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Garau G., Bebrone C., Anne C., Galleni M., Frère J. M., Dideberg O. (2005) J. Mol. Biol. 345, 785–795 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hernandez Valladares M., Felici A., Weber G., Adolph H. W., Zeppezauer M., Rossolini G. M., Amicosante G., Frère J. M., Galleni M. (1997) Biochemistry 36, 11534–11541 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Crawford P. A., Yang K. W., Sharma N., Bennett B., Crowder M. W. (2005) Biochemistry 44, 5168–5176 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Saavedra M. J., Peixe L., Sousa J. C., Henriques I., Alves A., Correia A. (2003) Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 47, 2330–2333 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ullah J. H., Walsh T. R., Taylor I. A., Emery D. C., Verma C. S., Gamblin S. J., Spencer J. (1998) J. Mol. Biol. 284, 125–136 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Spencer J., Clarke A. R., Walsh T. R. (2001) J. Biol. Chem. 276, 33638–33644 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Garrity J. D., Carenbauer A. L., Herron L. R., Crowder M. W. (2004) J. Biol. Chem. 279, 920–927 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.García-Sáez I., Mercuri P. S., Papamicael C., Kahn R., Frère J. M., Galleni M., Rossolini G. M., Dideberg O. (2003) J. Mol. Biol. 325, 651–660 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bellais S., Aubert D., Naas T., Nordmann P. (2000) Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 44, 1878–1886 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Morán-Barrio J., González J. M., Lisa M. N., Costello A. L., Peraro M. D., Carloni P., Bennett B., Tierney D. L., Limansky A. S., Viale A. M., Vila A. J. (2007) J. Biol. Chem. 282, 18286–18293 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Docquier J. D., Pantanella F., Giuliani F., Thaller M. C., Amicosante G., Galleni M., Frère J. M., Bush K., Rossolini G. M. (2002) Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 46, 1823–1830 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Docquier J. D., Lopizzo T., Liberatori S., Prenna M., Thaller M. C., Frère J. M., Rossolini G. M. (2004) Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 48, 4778–4783 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Simona F., Magistrato A., Dal Peraro M., Cavalli A., Vila A. J., Carloni P. (2009) J. Biol. Chem. 284, 28164–28171 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hu Z., Periyannan G., Bennett B., Crowder M. W. (2008) J. Am. Chem. Soc. 130, 14207–14216 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Nauton L., Kahn R., Garau G., Hernandez J. F., Dideberg O. (2008) J. Mol. Biol. 375, 257–269 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tomatis P. E., Fabiane S. M., Simona F., Carloni P., Sutton B. J., Vila A. J. (2008) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 105, 20605–20610 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kuzmic P. (1996) Anal. Biochem. 237, 260–273 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Inubushi T., Becker E. D. (1983) J. Magn. Reson. 51, 128–133 [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hwang T. L., Shaka A. J. (1995) J. Magn. Reson. A 112, 275–279 [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wilkins D. K., Grimshaw S. B., Receveur V., Dobson C. M., Jones J. A., Smith L. J. (1999) Biochemistry 38, 16424–16431 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hemmingsen L., Bauer R., Bjerrum M. J., Zeppezauer M., Adolph H. W., Formicka G., Cedergren-Zeppezauer E. (1995) Biochemistry 34, 7145–7153 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hemmingsen L., Sas K. N., Danielsen E. (2004) Chem. Rev. 104, 4027–4062 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.McManus-Munoz S., Crowder M. W. (1999) Biochemistry 38, 1547–1553 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Bertini I., Luchinat C. (1984) Adv. Inorg. Biochem. 6, 71–111 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Bertini I., Turano P., Vila A. J. (1993) Chem. Rev. 93, 2833–2932 [Google Scholar]

- 49.Rosenberg R. C., Root C. A., Gray H. B. (1975) J. Am. Chem. Soc. 97, 21–26 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Bertini I., Donaire A., Monnanni R., Moratal Mascarell J. M., Salgado J. (1992) J. Chem. Soc. Dalton Trans. 1443–1447 [Google Scholar]

- 51.Coleman J. E. (1993) Methods Enzymol. 227, 16–43 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Hemmingsen L., Damblon C., Antony J., Jensen M., Adolph H. W., Wommer S., Roberts G. C., Bauer R. (2001) J. Am. Chem. Soc. 123, 10329–10335 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Damblon C., Jensen M., Ababou A., Barsukov I., Papamicael C., Schofield C. J., Olsen L., Bauer R., Roberts G. C. (2003) J. Biol. Chem. 278, 29240–29251 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Gettins P. (1986) J. Biol. Chem. 261, 15513–15518 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Hemmingsen L., Olsen L., Antony J., Sauer S. P. (2004) J. Biol. Inorg. Chem 9, 591–599 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Lipscomb W. N., Sträter N. (1996) Chem. Rev. 96, 2375–2434 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Bounaga S., Laws A. P., Galleni M., Page M. I. (1998) Biochem. J. 31, 703–711 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Tioni M. F., Llarrull L. I., Poeylaut-Palena A. A., Martí M. A., Saggu M., Periyannan G. R., Mata E. G., Bennett B., Murgida D. H., Vila A. J. (2008) J. Am. Chem. Soc. 130, 15852–15863 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Spencer J., Read J., Sessions R. B., Howell S., Blackburn G. M., Gamblin S. J. (2005) J. Am. Chem. Soc. 127, 14439–14444 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Dal Peraro M., Vila A. J., Carloni P., Klein M. L. (2007) J. Am. Chem. Soc. 129, 2808–2816 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Dal Peraro M., Llarrull L. I., Rothlisberger U., Vila A. J., Carloni P. (2004) J. Am. Chem. Soc. 126, 12661–12668 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Dal Peraro M., Vila A. J., Carloni P. (2004) Proteins 54, 412–423 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Díaz N., Suárez D., Merz K. M., Jr. (2001) J. Am. Chem. Soc. 123, 9867–9879 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Olsen L., Rasmussen T., Hemmingsen L., Ryde U. (2004) J. Phys. Chem. B 108, 17639–17648 [Google Scholar]

- 65.Park H., Brothers E. N., Merz K. M., Jr. (2005) J. Am. Chem. Soc. 127, 4232–4241 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Rasia R. M., Vila A. J. (2004) J. Biol. Chem. 279, 26046–26051 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Llarrull L. I., Tioni M. F., Vila A. J. (2008) J. Am. Chem. Soc. 130, 15842–15851 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.González J. M., Medrano Martín F. J., Costello A. L., Tierney D. L., Vila A. J. (2007) J. Mol. Biol. 373, 1141–1156 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.