Abstract

This applied study attempted to evaluate a combination of transfer procedures commonly used to teach tacts to children with autism. A receptive to echoic to tact transfer and an echoic to tact transfer procedure were combined during 5-min instructional sessions to teach tacts to a seven-year-old vocal child with autism. A multiple baseline design across three sets of ten tacts was used. Without the teaching procedure, the child acquired no target tacts. With the 5-min teaching procedure implemented first with Set 1 then with Sets 2 and 3, respectively, the child acquired thirty new tacts over sixty teaching sessions. The results have wide application for children with and without autism who need instruction to learn tacts.

Keywords: teaching tacts, receptive echoic to tact transfer procedures, autism

Skinner (1957) observed that two types of nonverbal stimuli usually control verbal behavior: an audience and “nothing less than the whole of the physical environment” (p. 81). The stimuli in the physical environment can represent almost anything a person could “make contact with” through his sensory modalities. Thus, Skinner used the term “tact” for verbal behavior under the control of nonverbal stimuli. For instance, a child sees a book and says, “book.” The nonverbal stimulus of the book evoked the vocal response “book.”

Tacts, or labeling, form the foundation of language development (Sundberg & Partington, 1998). With tasks as simple as requesting a desired item to complex skills such as inferring meaning (e.g., Lowenkron, 2004) tacts play a critical role. Children with serious tacting deficits experience significant impairments. Developing effective procedures for establishing or transferring stimulus control has wide utility for those children having difficulty acquiring tacts.

There is sizable literature in behavior analysis that shows how to transfer stimulus control (e.g., Cooper, Heron, & Heward, 1987). However, there are few controlled studies on transferring stimulus control between verbal operants in children with autism (e.g., Drash, High, & Tudor, 1999; Sundberg, Endicott, & Eigenheer, 2000). In Teaching Language to Children with Autism and Other Developmental Disabilities, Sundberg and Partington (1998) describe a procedure for establishing stimulus control for vocal tacts with and without motivational variables. In the procedure they suggest starting with a nonverbal stimulus and saying, “What is that?” and then following the verbal stimulus with an echoic stimulus (e.g., “That's a bird”). The consequence for the child saying “bird” is praise and can be paired with a physical reinforcer such as a tickle. After implementing the previously described sequence the next step is to again present the nonverbal stimulus with the verbal stimulus, “What is that?” After the child says, “Bird,” the reinforcing consequence is again applied. The physical reinforcer may be faded at this step. The last part of the procedure presents the nonverbal stimulus with the child saying “bird” followed by praise. In practice, this would be referred to as an echoic to tact transfer, which is used frequently both within intensive and natural environment teaching.

Receptive to echoic to tact transfers are also used in clinical practices, but controlled studies using these transfer procedures to teach children with autism have not been extensively documented in the literature. The following applied experiment was conducted to examine a combination of two transfer procedures (receptive to echoic to tact and echoic to tact) to teach a child with autism additional tacts.

METHOD

Participant

The participant was Lucas, a seven-year-old boy with moderate autism and mild mental retardation. Prior to the study, Lucas received annual psychological testing. The Wechsler Abbreviated Scale of Intelligence revealed a full-scale IQ score of 63, Verbal IQ of 61 and Performance IQ of 70. On the Scales of Independent Behavior, his language comprehension was 4 years, 2 months and his language expression was at a 2 year, 4 month old level.

Lucas had a vocabulary of over 500 words. He usually spoke in one- to three-word utterances but occasionally formed sentences up to six words in length. He could effectively mand for items, actions and attention, answer simple questions, and follow two-step directions. Additionally, he had good imitative and echoic abilities. Lucas is the oldest son of the first author, who served as the instructor and conducted the study with the guidance of the second author.

Setting and Materials

The setting was Lucas' home. Training sessions took place in two areas of the house: at a small child's table in the basement and at an island counter area in the kitchen. The setting was not controlled for ambient noise level or other environmental events (e.g., sibling playing with toys). On weekdays the sessions were usually conducted after school at 4 p.m. On weekends the sessions occurred at various times. Materials, brought to the setting before beginning a session, included pictures of objects obtained from books, pictures of actual household items, or commercially produced picture flashcards. Each object picture was cut out and affixed to a white index card which displayed only one object (e.g., toothbrush, stapler). There were a total of 30 such object cards. A countdown timer was also used throughout the study.

Dependent Variable

The dependent variable was the number of correct tacts per set of 10 stimulus cards. A correct tact was defined as emitting the appropriate vocal response for the picture on a card without any additional tacts before or after that one. Three sets of 10 object cards were constructed. The number of correct tacts for each set was counted before the intervention began. Tacts were measured during a probe session at least 12 hrs and no more than 48 hrs after the last teaching session. During the probe, the instructor showed Lucas the picture and said, “What is it?” A correct response was recorded when Lucas emitted the tact of the picture within 3 s without saying any other tacts. The first five sessions, or baseline, were conducted on all three sets without any teaching. After five sessions, the procedure began for Set 1 only.

Procedure

A pool of approximately 100 objects was examined to select 30 unknown tacts. Because Lucas already had acquired over 500 tacts, most of the unknown tacts selected involved more obscure items. Only two- to three-syllable tacts were included. Once 35 objects were selected as potential targets, three typical peers (ages 5, 6, and 7) were used to be sure that the tacts were not too unfamiliar to children of Lucas' age. A few were discarded (“shower” and “matches”) after at least one of the peers answered incorrectly during the probe. Tacts were included in the study if they met the following criteria: 1) two to three syllables in length; 2) Lucas answered incorrectly or did not make a response; and 3) All three typical peers correctly identified the tact. These procedures yielded a total of 30 tacts, which were then randomly put into three sets (Table 1). It should be noted that for 55% of the 30 tacts, Lucas did not respond when asked, “What is it?” during the baseline probes. For 45% of the 30 tacts, Lucas answered with a word that was closely associated with the target tact name (i.e., answered “teacher” for the chalkboard, “lemonade” for the lemon). The tacts that had an associative, incorrect response on baseline were evenly distributed among sets.

Table 1.

The three sets of, initially unknown, tacts used in the transfer procedure.

| Set 1 | Set 2 | Set 3 |

| pudding | paper | salad |

| iron | calendar | shovel |

| mushroom | pencil | tomato |

| toaster | chalkboard | quarter |

| ice cream | dresser | stapler |

| bulldozer | lemon | butter |

| screwdriver | tractor | lipstick |

| mitten | dishes | teapot |

| razor | feather | vacuum |

| toothpaste | toothbrush | ambulance |

Baseline. The first five sessions were conducted on all three sets without any teaching. Lucas was simply shown each of the 30 cards and asked, “What is it?” After five probe sessions, the teaching procedure began for Set 1 only. After 12 instructional sessions, the baseline ended for Set 2 and teaching began. After another 12 sessions teaching began for Set 3. Only one session was run per day. The 60 sessions of the study were not on consecutive days and took three months to complete.

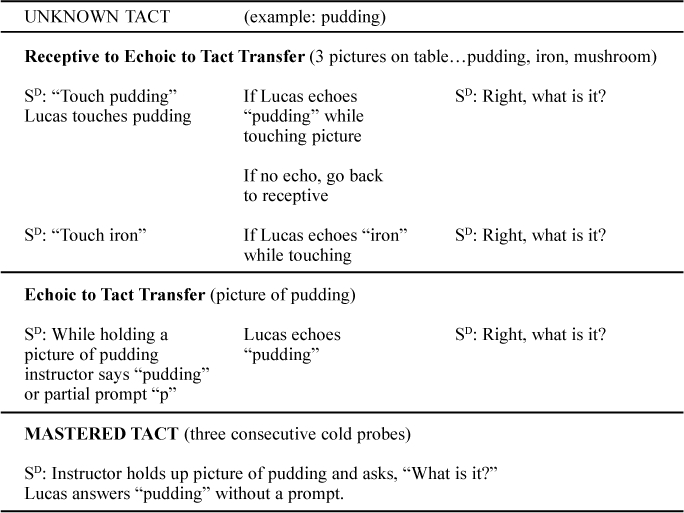

Teaching sessions. Teaching consisted of one timed 5-min session per day utilizing a combination of two different transfer procedures. A probe session occurred immediately before the training session. The first transfer procedure was a receptive to echoic to tact transfer procedure. Three of the 10 pictures were placed on the table. Lucas was directed to touch one of the pictures. Most-to-least prompting ensured that Lucas touched the picture of the correct item. Lucas usually made an echoic response while he touched the picture, which led to the use of the second transfer procedure, the echoic to tact transfer.

Figure 1 displays the teaching procedure used throughout the study. For example, pictures of pudding, an iron, and a mushroom were placed on the table and Lucas was told “touch pudding.” Lucas received a physical or gestural prompt, if needed, to touch the picture of the pudding. If he echoed “pudding” as he touched the picture, the echoic to tact transfer was immediately attempted. The picture of the pudding was held up and the instructor said, “Right, what is it?” If no response, the instructor said “pudding” and if Lucas echoed, the instructor again said, “Right, what is it?” If the transfer to tact was not successful, the instructor went back to the receptive command for a different item by saying “touch iron.” If Lucas echoed “iron,” the tact transfer was attempted for iron. If no echoic response, the third picture on the table was used to attempt the receptive to echoic to tact transfer. These transfer procedures were combined in a very fluid process moving rapidly from receptive to echoic to tact or moving from a non-response or error back to a receptive prompt.

Figure 1.

Correct tacts during baseline and a stimulus control transfer intervention.

Once Lucas showed success with scanning the pictures in an array of three, receptively identifying the named picture by pointing to it, and echoing the label, the receptive prompt was dropped for those pictures and only an echoic (either the full word or a partial phonemic) prompt was used.

During the echoic to tact transfer, the picture of the tact was held up and the tact was orally presented by the instructor. If Lucas did not echo the tact independently, the instructor said, “Say [tact Lucas did not echo].” Lucas typically said the word and then the instructor immediately attempted a transfer procedure by asking, “What is it?” If, at any time throughout the study, Lucas did not echo with or without a prompt, the instructor moved to the previous step of receptive prompts (e.g., “Touch [tact Lucas did not echo]”). These two transfer procedures were mixed together during the 5-min sessions.

At the beginning of introducing each set of 10 tacts, the instructor systematically targeted three or four of the tacts in the set. Receptive to echoic to tact transfers were used more frequently at the introduction of a set and echoic to tact transfers were utilized as tacts became more familiar. The data for the experiment were collected before the teaching session for the day began. During data collection for the dependent variable, the pictures were presented and the question asked, “What is it?” During the probes, the instructor did not prompt or correct Lucas. Praise statements such as “good job” or “right” immediately followed correct answers.

Interrater reliability. The instructor/first author took data during the dependent variable condition using a yes/no probe sheet. Another observer also took data for 30% of the sessions to measure interrater reliability. If Lucas said the tact correctly, a yes was circled under the date of the session next to that item. If he did not say the tact correctly, the no was circled. The first author's data sheet was compared with the observer's data sheet yielding agreements and disagreements. Agreement was calculated by dividing the smaller total by the larger total of agreements. The mean of interrater agreement across three sets was 100%.

RESULTS

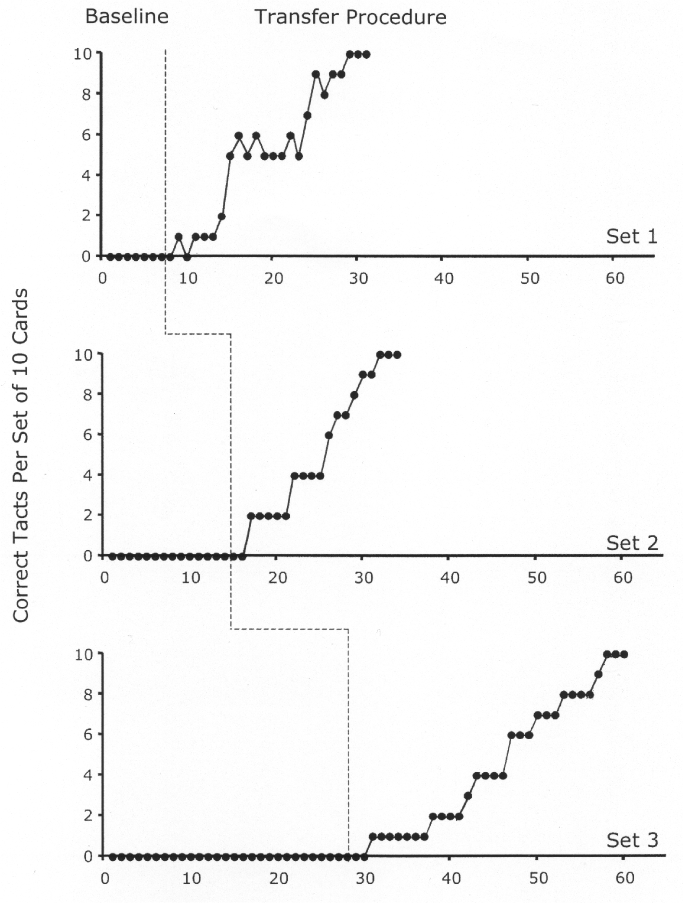

Figure 2 displays the number of correct tacts per set of 10 possible tacts during probe sessions. Five baseline probe sessions were completed for all sets. During baseline, Lucas did not make any correct tacts for any of the three sets. During the intervention all tacts were measured again followed by the first 5-min teaching session for Set 1 only (Session 6). The data show that after three teaching sessions (Session 9), Lucas answered one tact from set one correctly. As the teaching procedure continued for Set 1, he answered more correct tacts until he met the criterion of 3 days in a row at 100% accuracy.

Figure 2.

Illustrative diagram of the transfer procedures used within the 5-min teaching procedure.

For Set 2 he answered incorrectly during all of the 15 baseline trials. The teaching procedure was started for Set 2 after 12 teaching sessions for Set 1 (Session 15). After two teaching sessions for Set 2 (Session 17), Lucas answered 2 out of 10 correctly. He needed to continue to work on 5 tacts from Set 1 so these 5 were incorporated into the 5-min teaching sessions. After seven teaching sessions (Session 22) for Set 2, he answered 4 tacts correctly from Set 2 and after 11 teaching sessions (Session 26) for Set 2, he was correct for 6 out of 10 from Set 2 and 7 out of 10 for Set 1.

The teaching procedure for Set 3 was started after Set 1 was taught for 24 sessions (Set 1 was mastered) and Set 2 was taught for 12 sessions (Session 28). Lucas was answering 10 out of 10 correctly for Set 1, and 8 out of 10 correctly for Set 2 when the teaching sessions began for Set 3. By the seventh teaching session for Set 3 (Session 35), the mastery criterion for Sets 1 and 2 had been met (all 10 from set correct over three consecutive probes). As in the other two tiers, Lucas made steady progression to the criterion after implementation of the teaching procedure. Overall, he learned 30 tacts over 60 teaching sessions.

DISCUSSION

The data in this applied experiment show that a combination of two transfer procedures resulted in the successful acquisition of the 30 targeted tacts. Related to the procedure described by Sundberg and Partington (1998), this experiment also used a systematic procedure to establish and transfer stimulus control. The procedure was a fluid combination of a receptive to echoic to tact transfer and an echoic to tact transfer. As the data show, the combined transfer procedures were effective and efficient in establishing stimulus control for the targeted tacts.

An interesting feature of the data is the stepwise progression. Because the instructor focused on three to four tacts each session, Lucas generally answered those tacts correctly while not responding correctly to the others. This is most likely directly related to the fact that the instructor used a mass-trials procedure, which is used often in discrete trial teaching sessions. In the mass-trials procedure, the student is given the same instruction repeatedly and prompts are given to ensure correct student responding (Lovaas, 2002). Selecting three or four of the 10 targets at a time allowed mass trialing of these tacts and may have led to a step-wise pattern. In other words, data in Figure 2 show incremental growth directly related to how the instruction was delivered.

This study utilized the principles of errorless teaching while transferring skills from one operant to another. This supports the view that prompts should be used to prevent errors rather then to correct errors (Terrace, 1963). This also helps demonstrate that once correct responding is initiated with a prompt, the teacher's task should be to transfer stimulus control from the prompt to the task related stimuli (Touchette & Howard, 1984).

The receptive prompt, “Touch [targeted tact]” served as the controlling prompt in this experiment. Wolery, Ault, and Doyle (1992) described the need to use controlling prompts as much as possible to prevent errors while introducing new skills. They defined controlling prompts as, “teacher behaviors that ensure the student will respond correctly when asked to do the behavior” (p. 37). Non-controlling prompts, on the other hand, increase the probability of correct responding but do not ensure that the student will respond correctly.

In this experiment the instructor also used a graduated guidance approach. Wolery et al. (1992) noted the use of a graduated guidance procedure is a viable option when an instructor is experienced with prompt levels and prompt fading procedures. In this study, the instructor made moment-to-moment decisions regarding prompt delivery, prompt reduction, or prompt elimination based on the student's response. The instructor also prevented errors and non-responses by interrupting the incorrect response to provide the controlling prompt. The instructor used the graduated guidance procedure to decide on the prompt level and also to decide when to transfer the skill. When Lucas started to give an incorrect response or did not respond vocally to the SD, the instructor went back to the receptive direction, since this response could be easily prompted and functioned as the controlling prompt.

Limitations and future research. Because the two transfer procedures were used simultaneously, it is not known whether the use of the receptive part of the procedure was an important factor in Lucas' acquisition of tacts. One might speculate that the echoic to tact transfer procedure alone would have yielded similar tact acquisition results. However, we believe that the receptive part of the procedure was important because it insured successful responding in the context of tact instruction. Of course, more research is needed on this issue. Future research based on our study may focus on attempting to measure the effectiveness of the two transfer procedures used independently and/or in combination. Finally, children with different language profiles (high receptive/high echoic/low tacting ability versus high receptive/low echoic/high tacting ability) could be studied to better define which transfer procedures work best when teaching verbal behavior to individuals with different skill levels.

Conclusion. This applied study suggests that when teaching vocal verbal behavior to a child with poor tacting abilities, the use of a controlling prompt to obtain successful responding is an important consideration. Because a child such as Lucas cannot always be successfully prompted to speak, the use of receptive to echoic to tact transfer can provide a bridge to increasing vocal responding and lead to the successful acquisition of tacts.

REFERENCES

- Cooper J. O, Heron T. E, Heward W. L. Applied behavior analysis. Columbus, OH: Merrill; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Drash P. W, High R. L, Tudor R. M. Using mand training to establish an echoic repertoire in young children with autism. The Analysis of Verbal Behavior. 1999;16:29–44. doi: 10.1007/BF03392945. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lovaas O. I. Teaching individuals with developmental delays. Austin, TX: Pro-Ed; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Lowenkron B. Meaning: A verbal behavior account. The Analysis of Verbal Behavior. 2004;20:77–97. doi: 10.1007/BF03392996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sundberg M. L, Partington J. W. Teaching language to children with autism or other developmental disabilities. Pleasant Hills, CA: Behavior Analysts; 1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sundberg M. L, Endicott K, Eigenheer P. Using intraverbal prompts to establish tacts for children with autism. The Analysis of Verbal Behavior. 2000;17:89–104. doi: 10.1007/BF03392958. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skinner B. F. Verbal behavior. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall; 1957. [Google Scholar]

- Terrace H. Discrimination learning with and without “errors.”. Journal of the Experimental Analysis of Behavior. 1963;6:1–27. doi: 10.1901/jeab.1963.6-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Touchette P. E, Howard J. S. Errorless learning: Reinforcement contingencies and stimulus control transfer in delayed prompting. Journal of the Applied Behavior Analysis. 1984;17(2):175–188. doi: 10.1901/jaba.1984.17-175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolery M, Ault M. J, Doyle P.M. Teaching students with moderate to severe disabilities. White Plains, NY: Longman; 1992. [Google Scholar]