Abstract

Obesity, hypertension, cardiovascular disease, and inflammation are closely associated with the rising incidence of diabetes. One pharmacological target that may have significant potential to lower the risk of obesity-related diseases is the angiotensin type 1 receptor (AT1R). We examined the hypothesis that the AT1R blocker (ARB), valsartan, reduces the metabolic consequences and inflammatory effects of a high-fat (western) diet in mice. C57BL/6J mice were treated by oral gavage with 10 mg/kg/day of valsartan or vehicle and placed on either a standard chow or western diet for 12 weeks. Western diet-fed mice given valsartan had improved glucose tolerance, reduced fasting blood glucose levels, and reduced serum insulin levels compared to western diet alone-fed mice. Valsartan treatment also blocked western diet-induced increases in serum levels of the pro-inflammatory cytokines IFN-γ and MCP-1. In the pancreatic islets, valsartan enhanced mitochondrial function and prevented western diet-induced decreases in glucose-stimulated insulin secretion. In adipose tissue, valsartan reduced western diet-induced macrophage infiltration and expression of macrophage-derived MCP-1. In isolated adipocytes, valsartan treatment blocked or attenuated western diet-induced changes in expression of several key inflammatory signals: IL-12p40, IL-12p35, TNF-α, IFN-γ, adiponectin, platelet 12-lipoxygenase, collagen 6, iNOS, and AT1R. Our findings indicate that AT1R blockade with valsartan attenuated several deleterious effects of the western diet at the systemic and local level in islets and adipose tissue. This study suggests that ARBs provide additional therapeutic benefits in the metabolic syndrome and other obesity-related disorders beyond lowering blood pressure.

Keywords: valsartan, angiotensin type 1 receptor, inflammation, adipose tissue, macrophages, islets

Introduction

Obesity is a metabolic disorder characterized by chronic inflammation and dyslipidemia and is a strong predictor for the development of hypertension, diabetes, and cardiovascular disease. One potential pharmacologic target for treating obesity-related metabolic disorders is angiotensin II, a regulator of cardiovascular homeostasis (reviewed in (1)). Dysregulated angiotensin activity leads to hypertension and other cardiovascular complications. Specific inhibitors, such as the ARBs and angiotensin converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors, have implicated this pathway also in the development of metabolic diseases like obesity and type 2 diabetes. A meta-analysis of clinical trials with these inhibitors revealed an overall 25% reduction in new-onset diabetes (2). In addition, ARB treatment decreases fat cell volume and fat accumulation and improves differentiation of adipocytes, which is associated with a more insulin-sensitive phenotype (3–6). Thus, targeting angiotensin II may be a viable strategy in the treatment of the metabolic syndrome, type 2 diabetes, and other obesity-related disorders.

Angiotensin II is part of the renin-angiotensin system (RAS) and acts as a vasoconstrictor of blood vessels thereby regulating blood pressure, vascular tone, and fluid and electrolyte balance. Angiotensin II is also pro-inflammatory in blood vessels, causing increased reactive oxygen species (ROS) release, increased NF-κB nuclear translocation and subsequent pro-inflammatory cytokine transcription, and reduced endothelial nitric oxide synthase (eNOS) activity (reviewed in (7)). These pro-inflammatory pathways can be blocked by ARBs (8).

In spite of clinical support for ARB and ACE inhibitor treatment in reducing diabetes onset, the protection offered to pancreatic islets and adipocytes remains unclear. Local RAS have been identified in both pancreatic and adipose tissues and may play roles in the progression of the metabolic syndrome (reviewed in (9–10)). To concurrently address the in vivo effects of ARB administration on islets and adipose tissue, we orally administered valsartan to C57BL/6J mice fed either a chow or high-fat (western) diet. We evaluated the drug’s effects on metabolism, pancreatic islet and adipocyte function, and macrophage infiltration into adipose tissue and ensuing systemic inflammation. The results suggest valsartan ameliorates the damaging effects of high-fat feeding on pancreatic beta-cell function and adipose tissue inflammation. Our study is the first to address the potential of ARB protection of both islets and adipose tissue in vivo in a high-fat diet mouse model.

Methods

Male C57BL/6J mice were treated daily by oral gavage with 10 mg/kg/day of valsartan or vehicle and placed on either a standard chow or western diet for 12 weeks beginning at 6–8 weeks of age as previously reported (11). Measurements of glucose and insulin tolerance, body weight, and fasting blood glucose (BG) were made prior to termination. Pancreas, fat, and serum were then collected for additional studies. Methodological details are provided in the online supplement (see http://hyper.ahajournals.org). All experiments were performed in accordance with an animal study protocol approved by the UVA Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee.

Results

Effects of valsartan and western diet on body weight and BG

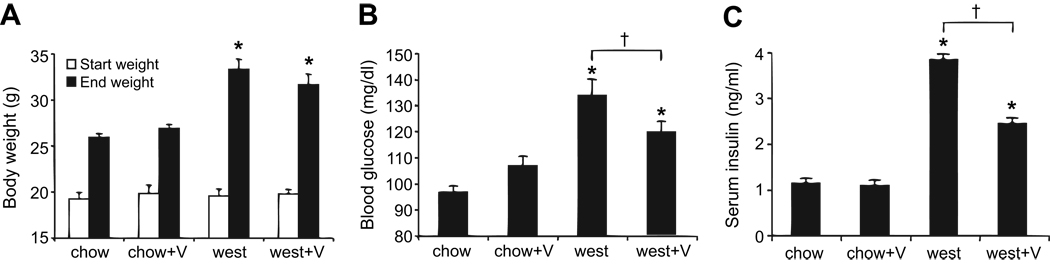

C57BL/6J mice were placed either on a chow or western (west) diet for 12 weeks and treated orally with 10 mg/kg/day of valsartan (V) or water vehicle. Body weight and BG were measured weekly. As shown in Figure 1A, the western diet caused significantly greater weight gain (including epididymal fat pad weight gain; see Figure 5B) by the end of the 12-week trial for both valsartan-treated and vehicle-treated mice. Neither body weights nor weight gains differed between west and west+V groups. Valsartan thus does not impact diet-induced weight gain or enlargement of adipose tissue.

Figure 1.

Valsartan reduces fasting BG and non-fasting serum insulin in western diet-fed mice. (A) Mean body weights at the start (white bars) and end (black bars) of the 12-week diet for various treatment groups. (B) Overnight fasting BG and (C) non-fasting serum insulin levels for each treatment group. *P<0.05 vs chow; †P<0.05 vs west. N=13–14 mice per group.

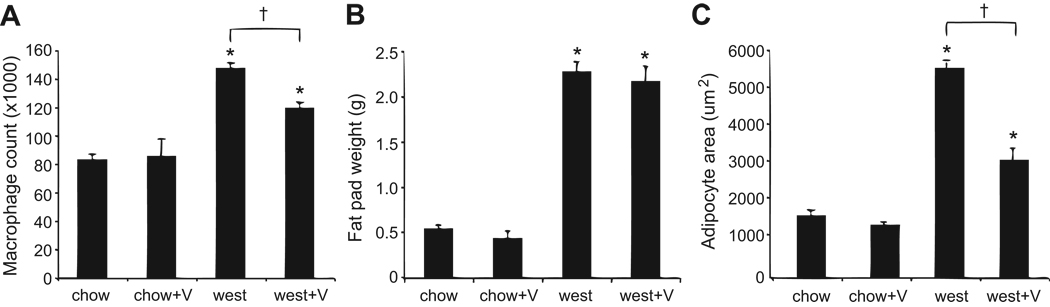

Figure 5.

Adipose tissue macrophage counts, adipose tissue weight, and adipocyte size. (A) Valsartan reduces macrophage infiltration into visceral fat as determined by FACS analysis; N=4 mice per group. The macrophage count was normalized to gram of starting epididymal fat tissue. (B) Weights from epididymal fat pads used for measuring macrophage infiltration; N=4 mice per group. (C) Average area of adipocytes from mice; N=3–4 mice per group. *P<0.05 vs chow; †P<0.05 vs west.

Weekly BG measurements did not differ among treatment groups at any point throughout the 12-week trial and remained <250 mg/dl in all treatment groups, indicating no incidence of diabetes (mean BG at last reading: chow, 168±4; chow+V, 169±7; west, 169±6; west+V, 174±5 mg/dl). However, as shown in Figure 1B, overnight fasting BG in mice at 10 weeks on the diet showed significant increases in the west group as compared to the chow-fed groups. Non-fasted insulin levels obtained at the termination of the study were substantially increased by the high-fat diet (Figure 1C). This effect was attenuated by valsartan. Consistent with increased and attenuated insulin secretion, respectively, islet hyperplasia was present in the west group, but absent in the west+V group (Figure S1). Furthermore, the proportion of insulin-stained beta-cells in the islets was significantly decreased in the west group and preserved with valsartan treatment (Figure S1).

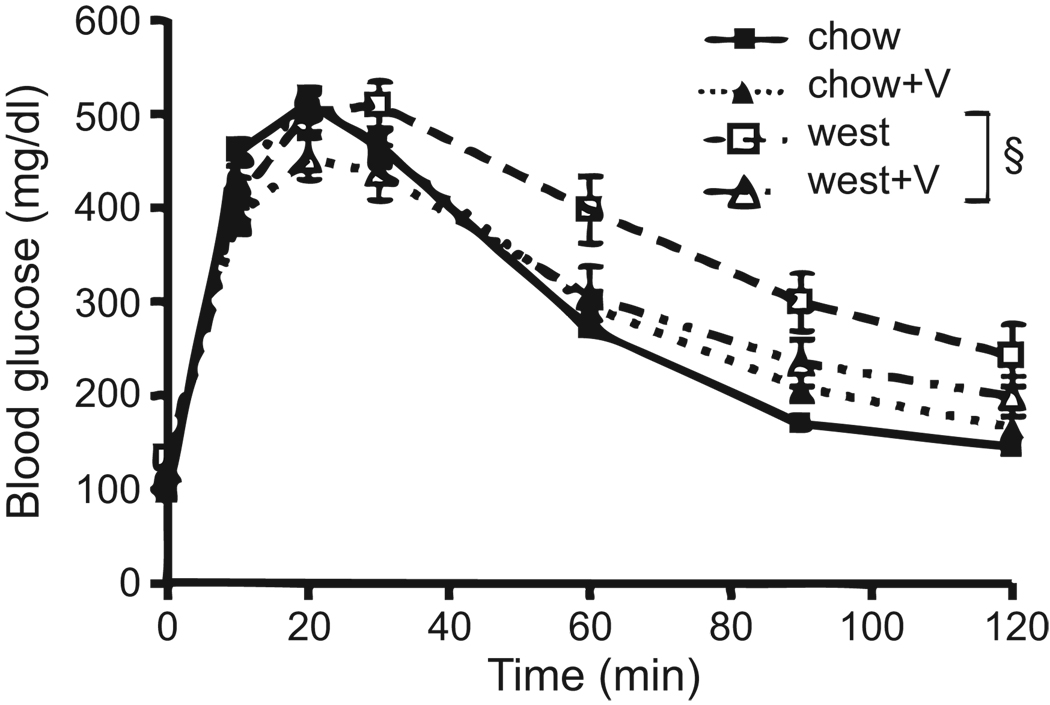

Glucose and insulin tolerance

Mice were subjected to a glucose tolerance test (GTT) and insulin tolerance test (ITT) at week 10 and 11, respectively. As shown in Figure 2, chow and chow+V groups displayed similar responses to the intraperitoneal glucose challenge. The west group had higher fasting BG prior to the glucose bolus (P<0.05, see also Figure 1B), did not respond as quickly, and glucose remained elevated when compared to chow-fed groups (P<0.01), suggesting that the west group has impaired glucose tolerance (Figure 2). The west+V group showed a significant improvement in glucose tolerance compared to the west group, but did not fully normalize to the level of controls (Figure 2). The ITT indicated slightly better insulin sensitivity in the chow+V mice (see Figure S2).

Figure 2.

Valsartan improves glucose tolerance. BG levels were measured at the indicated time points following an intraperitoneal glucose injection. §P<0.01 by two-way ANOVA. N=13–14 mice per group.

Valsartan reduces levels of serum cytokines

We obtained blood serum measurements for 32 circulating cytokines at the termination of the 12-week trial using a Luminex system. As shown in Table 1, IFN-γ and MCP-1, both key products of obesity-mediated inflammation, were significantly elevated in the west group compared to the chow group. This effect was reversed in the west+V group. In addition, MIP-1β and RANTES were both reduced in the west+V group compared to the chow and the west groups (Table 1). No significant differences were observed for the other cytokines tested.

Table 1.

Effects of valsartan on serum cytokine levels (pg/ml).

| Cytokine | chow | chow+V | west | west+V |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| IFN-γ | not detected | 2.34±2.34 | 7.61±2.32* | 1.51±1.51† |

| MCP-1 | 25.15±9.95 | 43.67±9.08 | 68.86±11.01* | 36.11±10.31‡ |

| MIP-1β | 92.79±32.63 | 90.65±11.29 | 67.60±22.19 | 17.24±17.24 |

| RANTES | 97.81±13.73 | 93.63±7.21 | 72.28±17.36 | 53.84±11.93 |

P<0.05 vs chow;

P<0.05,

P<0.10 vs west.

N=7–8 per treatment group per cytokine.

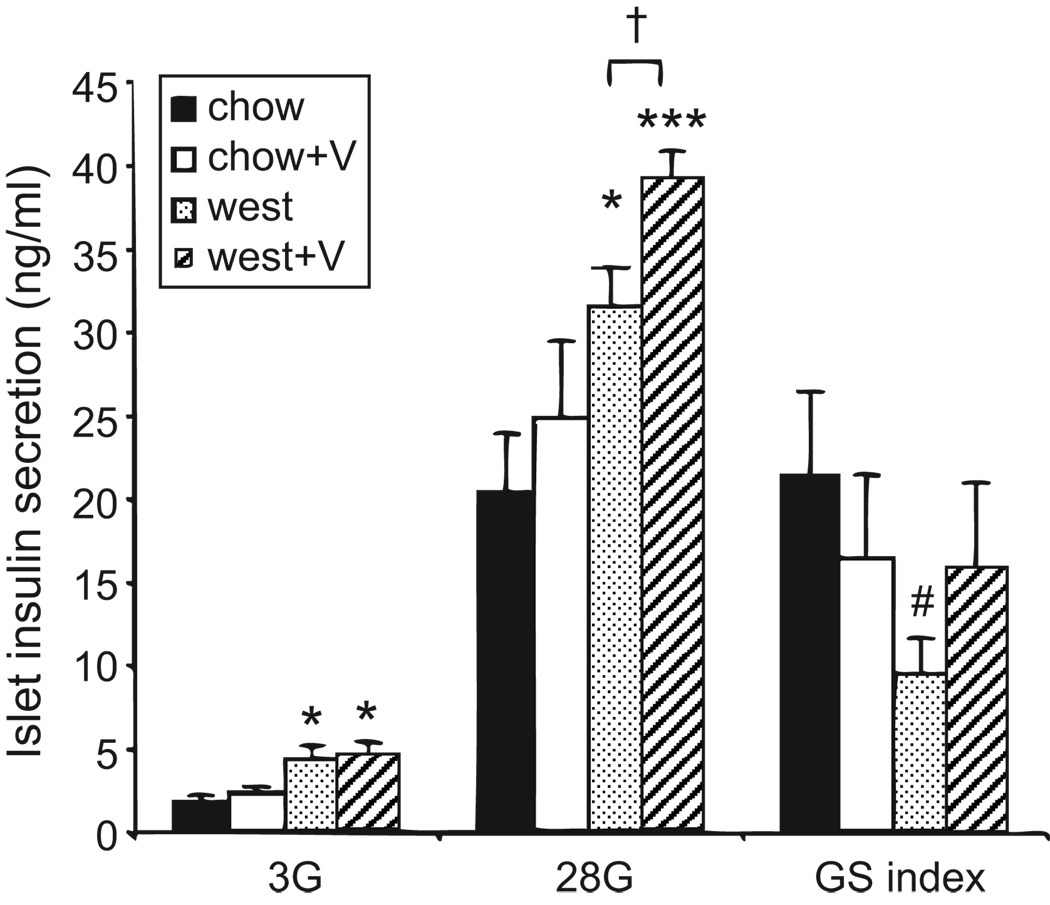

Valsartan improves glucose-stimulated insulin secretion

Isolated islets were assessed for physiological function by measuring basal insulin secretion (3 mmol/L glucose) followed by glucose-stimulated insulin secretion (28 mmol/L glucose). As shown in Figure 3, islets from both west and west+V mice showed an increase in basal and glucose-stimulated insulin secretion (28 mmol/L) compared to chow-fed groups. Mice in the west+V group also showed enhanced insulin secretion in 28 mmol/L glucose compared to mice fed a western diet alone (Figure 3). The ratio of stimulated to basal glucose (glucose stimulation index) was marginally reduced for the west group compared to the other treatment groups. These data suggest that valsartan tends to enhance glucose-stimulated insulin secretion in the context of a high-fat diet.

Figure 3.

Valsartan improves glucose-stimulated insulin secretion in islets. Islets were incubated one hour in 3 mmol/L glucose (3G) followed by one hour in 28 mmol/L glucose (28G), and insulin in medium was measured in ng/ml. GSI is the ratio of 28G/3G. *P<0.05, ***P<0.001, #P=0.052 vs chow; †P<0.05 vs west. Sets of 30 islets were used for each replicate per treatment group; N=8–10 replicates.

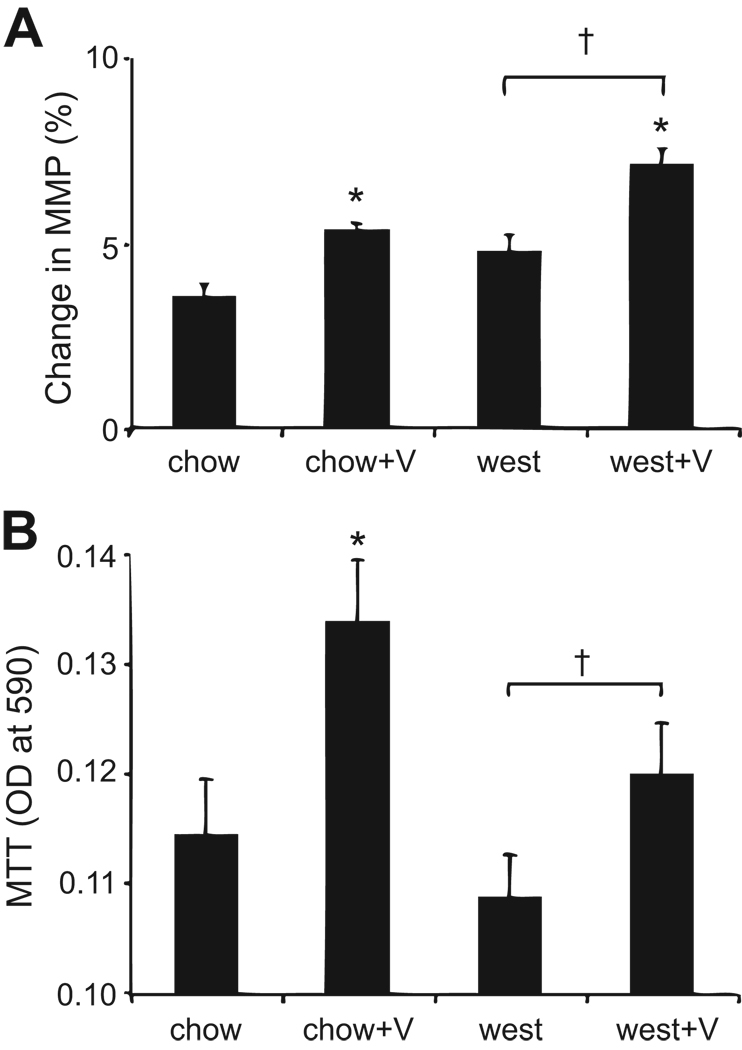

Valsartan enhances islet mitochondrial activity

We next examined islet mitochondrial activity since the angiotensin system may affect cell metabolism (reviewed in (12)). As shown in Figure 4A, increases in mitochondrial membrane potential were observed among islets from mice treated with valsartan. This result was supported by separate measurements of MTT (Figure 4B), a known product of mitochondrial activity. Thus, valsartan clearly has a stimulatory effect on the mitochondrial gradient that drives ATP production and increases the byproducts of mitochondrial activity.

Figure 4.

Valsartan stimulates mitochondrial activity. (A) Percent change in mitochondrial membrane potential (MMP) measured by rh123 fluorescence; N>30 islets for each treatment group. (B) Mitochondrial activity measured by MTT assay; N=4 sets of islets for each treatment group. *P<0.05 vs chow; †P<0.05 vs west.

Islet gene expression

We examined islet expression of several key pro-inflammatory genes (IFN-γ, TNF-α, MCP-1, IL-12p35, and IL-12p40). The 12-week western diet caused an increase only in IFN-γ expression (6.13-fold) that approached significance (P=0.07) and that was reduced by valsartan treatment (0.58-fold; P=0.06).

Valsartan reduces macrophage infiltration into adipose tissue

To investigate anti-inflammatory effects of valsartan, adipose tissue (epididymal fat pads) was collected and processed to isolate SVCs for FACS analysis. As shown in Figure 5A, macrophage content detected by both F4/80 and CD11b antibodies in the CD45 positive gate was nearly double in the west group compared to the chow group. However, macrophage numbers were significantly lower in the west+V group compared to the west group. As shown in Figure 5B, fat pad weights were much greater for all mice fed the western diet and valsartan treatment did not reduce fat pad weight. Adipocyte size was significantly increased with western diet, and this effect was ameliorated by valsartan (Figure 5C, S3). These findings suggest valsartan reduces the inflammatory response caused by western diet-induced changes in adipose tissue. The approximate two-fold reduction in adipocyte size in the presence of dramatically increased fat pad weight in the west+V group suggests that valsartan increases total adipocyte number in adipose tissue.

Effects of valsartan on gene expression in visceral adipose tissue and isolated adipocytes

We also investigated the possible effects of valsartan on the expression of key pro-inflammatory genes in visceral fat. As shown in Table 2, a substantial increase in MCP-1 expression, a key component in macrophage signaling, was seen in epididymal fat tissue from the west group. The increase was prevented by valsartan treatment. TNF-α and IL-6 showed a similar trend as MCP-1, but changes were not significant (Table 2). Adiponectin, an anti-inflammatory adipocyte-derived factor, showed reduced expression levels among mice on the western diet (Table 2); valsartan did not affect adiponectin expression. Increased expression of IL-12p40 was observed in the west group when compared to chow group (Table 2). Valsartan increased IL-12p40 in the chow and west group to similar levels.

Table 2.

Effects of valsartan on gene expression in adipose tissue.

| Gene | chow | chow+V | west | west+V |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MCP-1 | 1.05±0.12 | 1.10±0.15 | 23.98±8.00* | 5.70±1.99*† |

| IL-12p40 | 1.08±0.14 | 2.85±0.76* | 1.91±0.29* | 2.92±1.07 |

| TNF-α | 1.04±0.11 | 0.87±0.09 | 2.29±0.86 | 1.21±0.38 |

| IL-6 | 1.07±0.15 | 1.21±0.24 | 33.20±21.33 | 15.33±9.86 |

| Adiponectin | 1.09±0.23 | 1.31±0.21 | 0.36±0.06* | 0.50±0.11* |

Data are normalized to total actin and are presented as the fold change in expression compared to the chow-fed control group for each gene.

P<0.05 vs chow;

P<0.05 vs west.

N=9–12 per treatment group per gene.

We also examined differences in gene expression in isolated adipocytes. Although some findings were similar to that reported for whole fat tissue, some of the differences were more pronounced and new changes were seen in isolated adipocytes. As shown in Table 3, the west group showed significant upregulation of IL-12p35 and IL-12p40 whereas valsartan downregulated these pro-inflammatory cytokines in the chow and west group. The western diet also upregulated TNF-α, IFN-γ, as well as the anti-inflammatory enzyme, platelet 12-LO, implicated in angiotensin regulation (Table 3; see discussion for 12-LO); these effects were prevented in the west+V group. Adiponectin was significantly downregulated in the west group (Table 3), however, unlike in whole fat tissue, valsartan reversed the effects of western diet in isolated adipocytes. The western diet did not significantly upregulate TLR-4, MCP-1, or IL-6 (Table 3), although valsartan treatment reduced expression for each of these genes compared to chow controls to some degree. Additionally, expression of the extracellular matrix protein collagen 6 and inducible NOS (iNOS), both upregulated in obese rodent models in an inflammation-dependent manner (13–14), are induced by the western diet and decreased with valsartan treatment (Table 3). Finally, the AT1R was significantly upregulated by the western diet, and the effect was abrogated with valsartan treatment (Table 3). Taken together, these data suggest western diet-induced obesity substantially activates inflammation in adipocytes and valsartan treatment attenuated or prevented it (see Figure S4).

Table 3.

Effects of valsartan on gene expression in isolated adipocytes.

| Gene | chow | chow+V | west | west+V |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| IL-12p35 | 1.01±0.08 | 0.67±0.06* | 1.93±0.16* | 0.60±0.03*‡ |

| IL-12p40 | 1.01±0.07 | 0.67±0.08* | 1.31±0.12† | 0.92±0.11§ |

| TNF-α | 1.03±0.15 | 0.83±0.12 | 2.35±0.38* | 1.39±0.33 |

| IFN-γ | 1.02±0.15 | 0.79±0.16 | 2.49±0.56† | 0.93±0.32§ |

| Platelet 12-LO | 1.11±0.32 | 0.69±0.08 | 1.76±0.25 | 0.91±0.16‡ |

| Adiponectin | 1.02±0.12 | 1.05±0.11 | 0.55±0.08* | 0.91±0.07‡ |

| TLR4 | 1.01±0.05 | 0.65±0.08* | 0.98±0.04 | 0.81±0.06†§ |

| MCP-1 | 1.02±0.12 | 0.76±0.10 | 0.60±0.04* | 0.55±0.05* |

| IL-6 | 1.02±0.13 | 0.58±0.09* | 0.65±0.10† | 0.37±0.05*§ |

| Collagen 6 | 1.01±0.10 | 0.03±0.03* | 2.98±0.19* | 1.54±0.20†‡ |

| iNOS | 1.01±0.09 | 0.85±0.13 | 3.64±0.27* | 1.57±0.32‡ |

| AT1R | 1.05±0.19 | 0.78±0.08 | 1.86±0.11* | 1.11±0.21‡ |

Data are normalized to total actin and are presented as the fold change in expression compared to the chow-fed control group for each gene.

P<0.05,

P<0.10 vs chow;

P<0.05,

P<0.10 vs west.

N=4 per treatment group per gene.

Discussion

Our study provides evidence that treatment of western-diet fed mice with the AT1R blocker, valsartan, significantly reduces the deleterious effects of a high-fat intake. Noticeably, western diet-fed mice treated with valsartan exhibited improved glucose tolerance, improved insulin sensitivity (as indicated by lower serum insulin), reduced signs of visceral adipose tissue inflammation and macrophage infiltration, and improved pancreatic islet function compared to western diet alone-fed mice. These data suggest that the RAS plays a key role in modulating metabolism and the inflammatory response in response to a high-fat diet (see Figure S4).

When challenged with a high-fat diet, free fatty acids and inflammatory mediators are secreted by adipocytes and stromal inflammatory cells in the adipose tissue. These factors are released into the circulation to exert systemic effects (15). Elevated MCP-1 is associated with obesity, diabetes, and cardiovascular disease. MCP-1, the strongest known chemotactic factor for monocytes, is responsible for macrophage infiltration into the adipose tissue, leading to further cytokine expression, such as TNF-α, and thereby promoting inflammation. MCP-1 expression is increased by angiotensin II and reduced by RAS blockade (16–17). Consistent with these earlier findings, we observed that in the context of a high-fat diet valsartan reduced systemic and local adipose tissue MCP-1 levels and macrophage infiltration into the visceral adipose tissue. This may be one key mechanism by which valsartan reduces adipose tissue inflammation. We observed that MCP-1 was upregulated by a western diet in total adipose tissue and not in isolated adipocytes, whereas pro-inflammatory cytokines were upregulated in isolated adipocytes and not in total adipose tissue. This is consistent with reported observations that angiotensin II induces MCP-1 expression in pre-adipocytes and the macrophage-containing stromal vascular pool and not in adipocytes, while MCP-1 induces the expression of pro-inflammatory cytokines in adipocytes (18–20).

Central obesity correlates with an increased risk of developing type 2 diabetes. Adipose tissue dysfunction leads to increased release of pro-inflammatory mediators which in turn impair insulin signaling and pancreatic beta-cell function. For example, MCP-1, IFN-γ, IL-6, IL-12, and iNOS act systemically to impair whole body insulin sensitivity (21), and acute expression of a dominant negative MCP-1 in wild-type C57BL/6J mice fed a high-fat diet or db/db mice can reverse insulin resistance (22). Indeed, in our study, the mice fed a western diet exhibited increased MCP-1, IFN-γ, IL-12, and iNOS expression in serum and adipose tissue and impaired glucose tolerance and insulin sensitivity, and these changes were normalized by valsartan treatment. Adiponectin is an adipocyte-specific adipokine that improves insulin sensitivity by increasing energy expenditure and fatty acid oxidation (23). However, MCP-1 activation can decrease adiponectin expression (23). Type 2 diabetics often exhibit decreased levels of adiponectin, and insulin sensitivity is improved by adiponectin therapy (24). Treatment of hypertensive patients with ARBs leads to increased serum adiponectin levels (25–26). We observed that treatment of western diet-fed mice with valsartan ameliorated the diet-induced decrease in adiponectin in adipocytes, providing further support for a therapeutic role of AT1R blockade in restoring insulin sensitivity.

Angiotensin II primarily acts via the G-protein coupled transmembrane receptor, AT1R (reviewed in (1, 7)). In our study we observed that AT1R expression in adipocytes, which express all components of the RAS (27), was significantly upregulated when mice were fed a western diet, and this effect was reversed with valsartan administration. This is the first report that a high-fat diet leads to increased AT1R expression in adipocytes and that this can be prevented by ARB treatment.

High-fat diet-induced adipocyte hypertrophy leads to fibrosis of adipose tissue which promotes shear stress and inflammation (13). Consistent with this, we observed that collagen 6 is upregulated in adipocytes from western diet-fed mice and this is ameliorated by valsartan treatment. Studies utilizing valsartan have demonstrated decreases in adipocyte size and total visceral fat mass in rodents (3, 6, 28). We observed a decrease in adipocyte size when western diet-fed mice are treated with valsartan. This is consistent with the idea that AT1R blockade improves adipocyte function by promoting the development of smaller and more metabolically efficient adipocytes. No changes were observed in body weight or epididymal fat pad weight between the west and west+V groups in our study. This may be explained by differences in the dosage and duration of valsartan treatment in the previous studies, suggesting that longer valsartan treatment in our mice may eventually decrease adipose tissue weight. This is of clinical relevance as short-term valsartan administration in humans did not improve beta-cell function and insulin-responsiveness. Thus, longer therapeutic ARB treatment in humans may be needed for metabolic improvement (29).

The existence of a local RAS in the pancreatic islets is gaining increasing recognition and this RAS is induced by physiological and pathophysiological stimuli (reviewed in (9)). The pancreatic islet RAS regulates endocrine and exocrine functions relevant to the metabolic syndrome, such as local islet blood flow, islet beta-cell proinsulin biogenesis, glucose-stimulated insulin release, mitochondrial function, and pancreatic duct and acinar cell secretion (reviewed in (9, 12)). Angiotensin II impairs islet blood flow and can directly impair glucose-mediated insulin release (30). It also promotes mitochondrial oxidant release leading to decreased energy metabolism in the islets. Dysfunctional mitochondria contribute to the pathophysiology of diseases, such as hypertension, cardiovascular disease, and diabetes (reviewed in (12)). In support of a role for the islet RAS in mediating beta-cell function, we observed that valsartan decreased islet hyperplasia, enhanced mitochondrial activity, decreased IFN-γ expression, and mildly enhanced insulin secretion in islets. Similarly, islets from the obesity-induced type 2 diabetes db/db mouse model exhibited upregulation of RAS components and decreased beta-cell function, and treatment with the ARB losartan improved glucose-induced insulin release from these islets (31). This improvement may occur in part through reduction of the local islet inflammatory response in the presence of ARB (32–33). However, it is possible that ARB effects in islets may be secondary to reduced inflammation in visceral adipose tissue and reduced systemic inflammation. This is consistent with the lack of altered gene expression of components of the pancreatic RAS (data not shown).

Finally, our data indicate that ARB administration may target members of the fatty-acid metabolizing 12-lipoxygenase (12-LO) family, as we observed decreased expression of the platelet-form of 12-LO in adipocytes of valsartan-treated mice. We recently reported that 12-LO products promote an inflammatory response and impair insulin signaling in adipocytes (34). Moreover, 12-LO activation plays a significant role in promoting beta-cell toxicity, inflammation, and atherosclerosis (11, reviewed in (35)). The major arachidonic acid metabolite of 12-LO, 12(S)-hydroxyeicosatetranoic acid (12(S)-HETE), enhances AT1R expression in type 2 diabetic rat glomeruli (36) and is secreted in patient urine during the early diabetic process (reviewed in (35)). Angiotensin II increases expression of 12(S)-HETE in porcine vascular smooth muscle cells and fails to elicit vascular responses in 12-LO-deficient mice (reviewed in (35); 37). The ARB drugs valsartan and losartan decrease 12(S)-HETE expression in streptozotocin-induced diabetic mice and 12-LO expression in obese Zucker rat renal cortical tissue, respectively (38–39). Thus, AT1R may be a regulator of 12-LO activity, and is also regulated by 12-LO activity. Establishing the role that 12-LO plays in mediating RAS activity and ensuing complications will require additional studies.

Perspectives

In summary, AT1R blockade with valsartan significantly ameliorates several detrimental effects of a high-fat diet in mice: it reduces the inflammatory response, improves glucose tolerance, and offers protection for islet and adipose tissue (see Figure S4). Our study is unique in that we concurrently examined two key tissues targeted in the progression of the metabolic syndrome, type 2 diabetes, and other obesity-related disorders. Our results indicate that angiotensin II blockade may be an effective therapeutic strategy for the treatment of these diseases.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgments/Sources of Funding

This study was supported in part by an investigator-initiated research grant from Novartis Pharmaceuticals (East Hanover, NJ, USA); the remainder was supported by NIH NHLBI P01 HL55798 and NIDDK DK 55240. We thank the Animal Characterization Core and Cell and Islet Isolation Core at the UVA DERC (DK063609) for their contributions.

Disclosure

This study was supported in part by an investigator-initiated grant by Novartis Pharmaceuticals.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Olivares-Reyes JA, Arellano-Plancarte A, Castillo-Hernandez JR. Angiotensin II and the development of insulin resistance: Implications for diabetes. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2009;302:128–139. doi: 10.1016/j.mce.2008.12.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Abuissa H, Jones PG, Marso SP, O'Keefe JH., Jr Angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors or angiotensin receptor blockers for prevention of type 2 diabetes: a meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2005;46:821–826. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2005.05.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mori Y, Itoh Y, Tajima N. Angiotensin II receptor blockers downsize adipocytes in spontaneously type 2 diabetic rats with visceral fat obesity. Am J Hypertens. 2007;20:431–436. doi: 10.1016/j.amjhyper.2006.09.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Shimabukuro M, Tanaka H, Shimabukuro T. Effects of telmisartan on fat distribution in individuals with the metabolic syndrome. J Hypertens. 2007;25:841–848. doi: 10.1097/HJH.0b013e3280287a83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Janke J, Engeli S, Gorzelniak K, Luft FC, Sharma AM. Mature adipocytes inhibit in vitro differentiation of human preadipocytes via angiotensin type 1 receptors. Diabetes. 2002;51:1699–1707. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.51.6.1699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tomono Y, Iwai M, Inaba S, Mogi M, Horiuchi M. Blockade of AT1 receptor improves adipocyte differentiation in atherosclerotic and diabetic models. Am J Hypertens. 2008;21:206–212. doi: 10.1038/ajh.2007.50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Das UN. Is angiotensin-II an endogenous pro-inflammatory molecule? Med Sci Monit. 2005;11:RA155–RA162. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dandona P, Kumar V, Aljada A, Ghanim H, Syed T, Hofmayer D, Mohanty P, Tripathy D, Garg R. Angiotensin II receptor blocker valsartan suppresses reactive oxygen species generation in leukocytes, nuclear factor-kappa B, in mononuclear cells of normal subjects: evidence of an antiinflammatory action. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2003;88:4496–4501. doi: 10.1210/jc.2002-021836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Leung PS. The physiology of a local renin-angiotensin system in the pancreas. J Physiol. 2007;580:31–37. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2006.126193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Engeli S, Schling P, Gorzelniak K, Boschmann M, Janke J, Ailhaud G, Teboul M, Massiéra F, Sharma AM. The adipose-tissue renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system: role in the metabolic syndrome? Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2003;35:807–825. doi: 10.1016/s1357-2725(02)00311-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nunemaker CS, Chen M, Pei H, Kimble SD, Keller SR, Carter JD, Yang Z, Smith KM, Wu R, Bevard MH, Garmey JC, Nadler JL. 12-lipoxygenase-knockout mice are resistant to inflammatory effects of obesity induced by western diet. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2008;295:E1065–E1075. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.90371.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.de Cavanagh EM, Inserra F, Ferder M, Ferder L. From mitochondria to disease: role of the renin-angiotensin system. Am J Nephrol. 2007;27:545–553. doi: 10.1159/000107757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Khan T, Muise ES, Iyengar P, Wang ZV, Chandalia M, Abate N, Zhang BB, Bonaldo P, Chua S, Scherer PE. Metabolic dysregulation and adipose tissue fibrosis: role of collagen VI. Mol Cell Biol. 2009;29:1575–1591. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01300-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Perreault M, Marette A. Targeted disruption of inducible nitric oxide synthase protects against obesity-linked insulin resistance in muscle. Nat Med. 2001;7:1138–1143. doi: 10.1038/nm1001-1138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.de Ferranti S, Mozaffarian D. The perfect storm: obesity, adipocyte dysfunction, and metabolic consequences. Clin Chem. 2008;54:945–955. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2007.100156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Takahashi M, Suzuki E, Takeda R, Oba S, Nishimatsu H, Kimura K, Nagano T, Nagai R, Hirata Y. Angiotensin II and tumor necrosis factor-alpha synergistically promote monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 expression: roles of NF-kappaB, p38, and reactive oxygen species. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2008;294:H2879–H2888. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.91406.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kato S, Luyckx VA, Ots M, Lee KW, Ziai F, Troy JL, Brenner BM, MacKenzie HS. Renin-angiotensin blockade lowers MCP-1 expression in diabetic rats. Kidney Int. 1999;56:1037–1048. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.1999.00643.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Guo YJ, Li WH, Wu R, Xie Q, Cui LQ. ACE2 overexpression inhibits angiotensin II-induced monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 expression in macrophages. Arch Med Res. 2008;39:149–154. doi: 10.1016/j.arcmed.2007.07.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tsuchiya K, Yoshimoto T, Hirono Y, Tateno T, Sugiyama T, Hirata Y. Angiotensin II induces monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 expression via a nuclear factor-kappaB-dependent pathway in rat preadipocytes. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2006;291:E771–E778. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00560.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Xu H, Barnes GT, Yang Q, Tan G, Yang D, Chou CJ, Sole J, Nichols A, Ross JS, Tartaglia LA, Chen H. Chronic inflammation in fat plays a crucial role in the development of obesity-related insulin resistance. J Clin Invest. 2003;112:1821–1830. doi: 10.1172/JCI19451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Shoelson SE, Lee J, Goldfine AB. Inflammation and insulin resistance. J Clin Invest. 2006;116:1793–1801. doi: 10.1172/JCI29069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kanda H, Tateya S, Tamori Y, Kotani K, Hiasa K, Kitazawa R, Kitazawa S, Miyachi H, Maeda S, Egashira K, Kasuga M. MCP-1 contributes to macrophage infiltration into adipose tissue, insulin resistance, and hepatic steatosis in obesity. J Clin Invest. 2006;116:1494–1505. doi: 10.1172/JCI26498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rasouli N, Kern PA. Adipocytokines and the metabolic complications of obesity. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2008;93:S64–S73. doi: 10.1210/jc.2008-1613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yamauchi T, Kamon J, Waki H, Terauchi Y, Kubota N, Hara K, Mori Y, Ide T, Murakami K, Tsuboyama-Kasaoka N, Ezaki O, Akanuma Y, Gavrilova O, Vinson C, Reitman ML, Kagechika H, Shudo K, Yoda M, Nakano Y, Tobe K, Nagai R, Kimura S, Tomita M, Froguel P, Kadowaki T. The fat-derived hormone adiponectin reverses insulin resistance associated with both lipoatrophy and obesity. Nature Med. 2001;7:941–946. doi: 10.1038/90984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Furuhashi M, Ura N, Higashiura K, Murakami H, Tanaka M, Moniwa N, Yoshida D, Shimamoto K. Blockade of the renin-angiotensin system increases adiponectin concentrations in patients with essential hypertension. Hypertension. 2003;42:76–81. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000078490.59735.6E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Makita S, Abiko A, Naganuma Y, Moriai Y, Nakamura M. Effects of telmisartan on adiponectin levels and body weight in hypertensive patients with glucose intolerance. Metabolism. 2008;57:1473–1478. doi: 10.1016/j.metabol.2008.05.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ailhaud G, Fukamizu A, Massiera F, Negrel R, Saint-Marc P, Teboul M. Angiotensinogen, angiotensin II and adipose tissue development. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 2000;24:S33–S35. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0801501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sugimoto K, Qi NR, Kazdová L, Pravenec M, Ogihara T, Kurtz TW. Telmisartan but not valsartan increases caloric expenditure and protects against weight gain and hepatic steatosis. Hypertension. 2006;47:1003–1009. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000215181.60228.f7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bokhari S, Israelian Z, Schmidt J, Brinton E, Meyer C. Effects of angiotensin II type 1 receptor blockade on beta-cell function in humans. Diabetes Care. 2007;30:181. doi: 10.2337/dc06-1745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Huang Z, Jansson L, Sjöholm A. Vasoactive drugs enhance pancreatic islet blood flow, augment insulin secretion and improve glucose tolerance in female rats. Clin Sci (Lond) 2007;112:69–76. doi: 10.1042/CS20060176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chu KY, Lau T, Carlsson PO, Leung PS. Angiotensin II type 1 receptor blockade improves beta-cell function and glucose tolerance in a mouse model of type 2 diabetes. Diabetes. 2006;55:367–374. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.55.02.06.db05-1022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chu KY, Leung PS. Angiotensin II Type 1 receptor antagonism mediates uncoupling protein 2-driven oxidative stress and ameliorates pancreatic islet beta-cell function in young Type 2 diabetic mice. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2007;9:869–878. doi: 10.1089/ars.2007.1590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nakayama M, Inoguchi T, Sonta T, Maeda Y, Sasaki S, Sawada F, Tsubouchi H, Sonoda N, Kobayashi K, Sumimoto H, Nawata H. Increased expression of NAD(P)H oxidase in islets of animal models of Type 2 diabetes and its improvement by an AT1 receptor antagonist. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2005;332:927–933. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2005.05.065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chakrabarti SK, Cole BK, Wen Y, Keller S, Nadler J. 12/15-lipoxygenase products induce inflammation and impair insulin signaling in 3T3-L1 adipocytes. Obesity. 2009;17:1657–1663. doi: 10.1038/oby.2009.192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Natarajan R, Nadler J. Lipid inflammatory mediators in diabetic vascular disease. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2004;24:1542–1548. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000133606.69732.4c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Xu ZG, Miao LN, Cui YC, Jia Y, Yuan H, Wu M. Angiotensin II type 1 receptor expression is increased via 12-lipoxygenase in high-glucose stimulated glomerular cells and type 2 diabetic glomeruli. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2009;24:1744–1752. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfn703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Anning PB, Coles B, Bermudez-Fajardo A, Martin PE, Levison BS, Hazen SL, Funk CD, Kühn H, O'Donnell VB. Elevated endothelial nitric oxide bioactivity and resistance to angiotensin-dependent hypertension in 12/15-lipoxygenase knockout mice. Am J Pathol. 2005;166:653–662. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)62287-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Abdel-Rahman EM, Abadir PM, Siragy HM. Regulation of renal 12(S)-hydroxyeicosatetraenoic acid in diabetes by angiotensin AT1 and AT2 receptors. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2008;295:R1473–R1478. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.90699.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Xu ZG, Lanting L, Vaziri ND, Li Z, Sepassi L, Rodriguez-Iturbe B, Natarajan R. Upregulation of angiotensin II type 1 receptor, inflammatory mediators, and enzymes of arachidonate metabolism in obese Zucker rat kidney: reversal by angiotensin II type 1 receptor blockade. Circulation. 2005;111:1962–1969. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000161831.07637.63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.