Abstract

Songbirds produce learned vocalizations that are controlled by a specialized network of neural structures, the song control system. Several nuclei in this song control system demonstrate a marked degree of adult seasonal plasticity. Nucleus volume varies seasonally based on changes in cell size or spacing, and in the case of nucleus HVC and area X on the incorporation of new neurons. Reelin, a large glycoprotein defective in reeler mice, is assumed to determine the final location of migrating neurons in the developing brain. In mammals, reelin is also expressed in the adult brain but its functions are less well characterized. We investigated the relationships between the expression of reelin and/or its receptors and the dramatic seasonal plasticity in the canary (Serinus canaria) brain. We detected a broad distribution of the reelin protein, its messenger RNA and the mRNAs encoding for the reelin receptors (VLDLR and ApoER2) as well as for its intracellular signaling protein, Dab1. These different mRNAs and proteins did not display the same neuroanatomical distribution and were not clearly associated, in an exclusive manner, with telencephalic brain areas that incorporate new neurons in adulthood. Song control nuclei were associated with a particular specialized expression of reelin and its mRNA, with the reelin signal being either denser or lighter in the song nucleus than in the surrounding tissue. The density of reelin-ir structures did not seem to be affected by four weeks of treatment with exogenous testosterone. These observations do not provide conclusive evidence that reelin plays a prominent role in the positioning of new neurons in the adult canary brain but call for additional work on this protein analyzing its expression comparatively during development and in adulthood with a better temporal resolution at critical points in the reproductive cycle when brain plasticity is known to occur.

Keywords: Reelin, Dab-1, songbirds, neuroplasticity, in situ hybridization, immunocytochemistry

1. Introduction

The acquisition and production in oscine songbirds of learned, often complex, vocalizations is regulated by a set of neural structures often referred to as the song control system (Nottebohm 1980a: Brenowitz et al. 1997; Nottebohm, 2005). This neural system includes at least two major circuits: a caudal motor pathway necessary for the acquisition and production of learned song (Nottebohm et al., 1976; Yu and Margoliash, 1996) and a rostral pathway necessary for the imitation of an external model but not necessary for its production (Bottjer et al., 1984). The caudal motor pathway originates in HVC (used as a proper name, Reiner et al., 2004), from where it projects to the nucleus arcopallialis (RA), itself connected directly and indirectly with the neurons of the tracheosyringeal part of the hypoglossal nucleus (nXIIts) that innervate the syrinx (vocal organ of birds); in addition, RA innervates brainstem nuclei that control respiration. The anterior pathway also originates in HVC, from where it projects to Area X of the medial striatum, that in turn projects to the medial part of the dorsolateral thalamic nucleus (DLM), and from there to the lateral part of the magnocellular nucleus of the anterior nidopallium (lMAN) that projects back to RA (Nottebohm et al., 1976, 1982; Okuhata and Saito, 1987; Bottjer et al., 1989).

Some of the nuclei in this system exhibit in adulthood considerable anatomical plasticity (Ball, 1999; Tramontin and Brenowitz, 2000). In many songbird species that live in the temperate zones, the occurrence of singing and the stereotypy of singing vary seasonally, often being maximal in the spring, when territories are first acquired, followed by pair formation. The volume of song control nuclei HVC and RA vary in parallel with these changes in singing. For example, HVC and RA are twice as large in early spring as during the fall (Nottebohm, 1981). The changes in RA may result in part from hormone-dependent changes in dendritic length, synapse numbers, cell size and spacing (DeVoogd and Nottebohm, 1981; Canady et al., 1988; Brenowitz, 2004; Thompson and Brenowitz, 2005). The volume changes in HVC are accompanied by the death and subsequent replacement of some of its cells (Kirn and Nottebohm, 1993; Kirn et al., 1994; Tramontin and Brenowitz, 2000), a phenomenon that does not occur in RA. New neurons continue to be added, too, to the Area X of adult songbirds (Lipkind et al., 2002) though seasonal changes in neuronal recruitment were not observed in studies designed to explain the cellular basis of seasonal variation in area X volume in song sparrows (Thompson and Brenowitz 2004).

The birth, migration, recruitment into existing circuits and replacement of neurons in adult brain (Goldman and Nottebohm, 1983; Paton and Nottebohm, 1984; Alvarez-Buylla and Nottebohm, 1988; Kirn et al., 1994) and their molecular underpinnings remain poorly understood. It seems reasonable, though, to suppose that molecular agents that control these events in mammals might also be expressed in parts of the adult avian brain that engage in neurogenesis and the recruitment and replacement of neurons. We showed recently that the protein doublecortin, which is expressed in post-mitotic neurons and, as part of the microtubule machinery, is required for neuronal migration, is still expressed at high levels in the adult canary (Serinus canaria) telencephalon (Boseret et al., 2007), but at much lower levels in the adult mammalian brain (des Portes et al., 1998; Couillard-Despres et al., 2005) where adult neurogenesis is more restricted.

Similarly, the glycoprotein reelin seems broadly expressed in the brain of adult starlings (Sturnus vulgaris) (Absil et al., 2003) suggesting that it may play a role in the positioning of migrating neuroblasts (e.g., in HVC where the protein is expressed at relatively high density) but also that it should be implicated in other functions since expression is also detected in areas that are not known to incorporate new neurons in adults. The focus of studies of Reelin expression in mammals has been on the critical role it plays during the embryonic period (Schiffmann et al., 1997, Bar et al., 2000). In mammals, reelin is secreted by several different classes of cells, including in particular the Cajal-Retzius cells in the marginal cortical area that produce the protein during development of the cortex, hippocampus and dentate gyrus (Forster et al., 2006). A deficit in reelin secretion produces in humans a major malformation of the cortex called lissencephaly characterized by the absence of folds at the surface of the brain (Hong et al., 2000). Reelin-deficient (reeler) mice similarly show major cytoarchitectonic abnormalities in the central nervous system, as well as marked neurological dysfunctions including ataxia, tremors and imbalance (D’Arcangelo et al., 1995, Tissir and Goffinet, 2003, Forster et al., 2006). Based on these and other observations, it is has been hypothesized that reelin plays a significant role in the control of neuronal migration and determination of the final position of neurons in the developing brain, perhaps even acting as a cellular “stop” signal (Pearlman and Sheppard 1996). This led us to investigate whether reelin is also expressed in the adult canary brain, in particular in areas that incorporate new neurons, and if so to determine whether reelin expression relates in any way with the localization and numbers of new neurons that are incorporated.

Reelin is secreted in the extracellular space and reelin-signaling is then mediated through its binding to two types of membrane-associated receptors, the very low density lipoprotein receptor (VLDLR) and the apolipoprotein E receptor 2 (ApoER2) expressed at the surface of migrating neurons and of radial glial cells (Forster et al., 2006). When occupied, VLDLR and ApoER2 associate with the intracellular protein Disabled1 (Dab1). This induces the phosphorylation of Dab1 and triggers an intracellular signaling cascade that finally causes the neurons to assume their final shape and location. The importance of this signaling pathway is confirmed by the observation that the inactivation of Dab1 or the double inactivation of VLDLR and ApoER2 result in the same neurological phenotype as reelin deficiency (see (Forster et al., 2006) for review).

As would be expected from its role in neuronal positioning, in the rodent brain reelin expression during ontogeny is generally correlated with the anatomical differentiation of the central nervous system (Schiffmann et al., 1997). Later in post-natal life, there is evidence that Reelin continues to be expressed and takes on other functions (Fatemi, 2005a). For example, it has been shown to stimulate dendrite development (Niu et al., 2004) and to modulate synaptic plasticity by enhancing LTP (Weeber et al., 2002). Reelin also modifies N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA) and dopamine function (Qiu et al., 2006, Matsuzaki et al., 2007). In addition, reelin has been implicated in a number of psychiatric diseases such as bipolar psychotic disorder or schizophenia (Guidotti et al., 2000).

Reelin expression has been previously detected in the brain of a number of avian and reptilian species (Bernier et al., 1999, Goffinet et al., 1999, Bernier et al., 2000, Absil et al., 2003, Li et al., 2007) indicating that this protein has been conserved during evolution. Its structure is also similar across species as attested by the observation that a same antibody detects this protein in the brain of various species belonging to all classes of vertebrates form fishes to mammals (see (Absil et al., 2003) for discussion). Comparative studies of the role of Reelin and Dab1 in neural development in a range of species including chicks lead to the conclusion that its developmental function for the vertebrate brain is highly conserved (Bar et al., 2000). Indeed Bar et al. (2000) argue that despite the fact that there are significant taxonomic differences among reptiles, birds and mammals in cortical/pallial organization and the developmental pattern of cellular migration that the fundamental role of Reelin and Dab1 for architectonic development is the same in these different lineages (Bar et al., 2000). Given its role in brain development and plasticity, we investigated here the possible relationships between the expression of reelin and/or its receptors and the dramatic seasonal plasticity that has been extensively characterized in the canary brain (Nottebohm, 1981, Brenowitz, 2004). The specific goals of the present experiments were therefore: 1) to verify the presence of the reelin protein and mRNA and its neuroanatomical distribution in relation to the sites such as the nidopallium and medial striatum (but not the arcopallium) that are known to incorporate new neurons and experience a marked seasonal plasticity, in particular the song control nuclei 2) assess in this species the anatomical relationships between the pattern of reelin expression and the expression of the receptors (VLDLR, ApoER2) or intracellular signaling protein (Dab1) that are supposed to mediate reelin action, and 3) determine whether, as suggested in a previous study(Absil et al., 2003) reelin expression is modulated by steroids in parallel with the volume of song control nuclei such as HVC and RA.

2. Material and methods

2.1. Subjects

All experiments reported here were carried out on male and female canaries (Serinus canaria) belonging to the “Malines” Belgian breed, a population of mixed origin with a predominance of German roller. All birds were bought from a local dealer in Belgium. Two separate groups of subjects were used for in situ hybridization (ISH) and immunocytochemical (ICC) studies. Food, water, sand and bathing water were always available ad libitum. All experimental procedures were in agreement with the Belgian laws on “Protection and Welfare of Animals” and on the “Protection of experimental animals” and the NIH Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals. The protocols were approved by the Ethics Committee for the Use of Animals at the University of Liège.

2.2. In situ hybridization

2.2.1. Animals and brain histology

Adult males (N=5) and females (N=5) who were born during the previous breeding season were obtained in February from the local dealer. They had been kept until that time in natural photoperiods characteristic of the area around Liège, Belgium. Upon arrival in the laboratory, birds were immediately transferred to a short photoperiod (6L:18D) for 8 weeks to make sure they would be photosensitive at the beginning of the experiment (Nicholls and Storey, 1977) and would therefore respond in a homogeneous manner to the subsequent photostimulation. They were then switched for three weeks to a long photoperiod (16L:8D) to stimulate song production and song control nuclei growth. Birds were repeatedly observed during this three-week period to make sure all males produced full complete songs. This duration of photostimulation was selected to ensure that brains would be collected at a time when HVC volume would be in its growth phase and a significant growth would already have occurred but volume was not yet maximal. This ensured that some neural plasticity would be ongoing but of course not that the time of maximal reelin expression would be selected. A time-course study only would be able to provide that information but was beyond the scope of this first exploration.

Birds were killed by decapitation, brains were dissected out of the skull, frozen on dry ice and stored at −80°C until used. Frozen brains were cut on a cryostat into five series of 30 μm coronal sections (one section every 150 μm in each series) that were mounted onto Superfrost Plus slides (Menzel-Gläser, Braunschweig, Germany). The plane of the sections was adjusted to match as closely as possible the plane of the canary brain atlas (Stokes et al., 1974). One series of sections was Nissl-stained with thionin blue to provide anatomical landmarks for the interpretation of the in situ hybridization signals. In situ hybridization for reelin, Dab, ApoE2 or VLDLR mRNA was carried out on adjacent series of sections.

2.2.2. Cloning of cDNA probes

Based on sequence information available from chicken (see below), PCR was used to amplify fragments of reelin, Dab1, ApoER2 (also referred to as LR8B) and VLDLR expressed in the songbird brain. The mRNA from a zebra finch (Taeniopygia guttata) brain was prepared by using the RNeasy Mini Kit (Qiagen GmbH, Hilden, Germany). The synthesis of first-strand cDNA was done with SUPERSCRIPT II Reverse Transcriptase (Invitrogen, Karlsruhe, Germany) and oligo (dT)-primer. The resulting RNA-DNA hybrids were subsequently used in PCR’s to generate pieces of the appropriate genes. The following primers were then used in PCR:

| For reelin: | forward: 5′-CAACCAGGATACATGATGCAGTT-3′

reverse: 5′-AAGTCCTTTGGCTGATGCTG-3′ |

| For Dab1: | forward: 5′-GACAAGCAGTGTGAACAGGC-3′

reverse: 5′-AGGCTGAGCCATATGGAAATC-3′ |

| For ApoER2: | forward: 5′-TGGACTGACCTGGAGAATGAAGC-3′

reverse: 5′-TTCTTCCGTTTCCAGTTTCTCCA-3′ |

| For VLDLR: | forward: 5′-GAAAAAGCAGGAATGAATGG-3′

reverse: 5′-TAGACGGGATTATCAAAATTCAT-3′. |

PCR was carried out for 40 cycles by using the following parameters: 94°C for 1 minute, 53°C for 30 seconds, 72°C for 1 minute. Amplified fragments were purified, blunt-ended and cloned into the Sma I site of the plasmid vector pGEM7ZF (Promega, Mannheim, Germany). Resultant clones were sequenced to verify the authenticity and fidelity of the amplification. The cloned reelin sequence is 800 bp in length and is 93 % identical to the chicken counterpart (GenBank no. AF 090441). The cloned partial Dab1 sequence is 741 bp in length and is 93 % identical to the chicken Dab1 (GenBank no. AF 527579). The cloned ApoER2 sequence is 635 bp in length and is 83 % identical to the chicken sequence (NM_205186). The cloned VLDLR sequence is 756 bp in length and is around 90 % identical to the chicken sequence (NM_205229).

2.2.3. In situ hybridization

The expression of the corresponding mRNAs in brain sections was detected with antisense RNA probes labeled with 35S-CTP. The distribution of reelin, Dab1 and ApoER2 was studied in alternate sets of sections throughout the brain of 4 males and 4 females. The distribution of VLDLR was only tested in sections from one male and one female. Labeling of the probes with 35S-CTP (1250 Ci/mmol; Perkin Elmer, Rodgau, Germany) was performed using the Riboprobe System (Promega). Our in situ hybridization procedure followed a previously published protocol (Whitfield et al., 1990) with modifications as previously described in detail (Voigt et al., 2007). For signal detection, sections were exposed to autoradiographic film (Kodak Biomax MR, Rochester, NY, USA) for various durations (reelin, 4 weeks; Dab1, 9 weeks; ApoER2 and VLDLR, 14 weeks).

Autoradiograms were trans-illuminated with a ChromaPro 45 light source and acquired with a CCD digital camera connected to a Macintosh computer running the image analysis software Image J 1.36b (NIH, USA; see http://rsb.info.nih.gov/ij/). Representative sections were then drawn with the Canvas 9 software (ACD Systems Inc, Victoria BC, Canada) and representative plates were prepared based on these drawings and on digitized autoradiograms. Selected sections were also exposed to emulsion (Kodak NTB, Rochester, NY, USA) and then examined and photographed under darkfield illumination with a microscope (Leitz Aristoplan; Leica Microsystems, Bensheim, Germany).

2.3. Immunocytochemistry

2.3.1. Animals and endocrine treatments

Another batch of adult male (N=14) canaries were obtained in April as yearlings. Before their arrival in the laboratory, birds were housed in outdoor aviaries under a natural photoperiod. Immediately after their arrival in the University animal facility, all birds were housed indoors in flocks of 3–4 individuals at a stable temperature (20–24°C) under a 11L:13D photoperiod.

During the following week, all males were castrated through a unilateral incision behind the last rib on the left side as previously described (Sartor et al., 2005) and then transferred two weeks later to a short photoperiod (6L:18D) for 8 weeks to make sure they would be photosensitive at the beginning of the endocrine treatments (Niu et al., 2004).

On the first day of the experiment, that is ten weeks after castration (day 0), all birds were implanted with one Silastic™ capsule filled with either crystalline testosterone (T; Fluka Chemika, Buchs, Switzerland, Cat. nbr: 86500; n=7) or left empty as control (C; n=7). Capsules were made of Silastic™ tubing (Degania Silicone, Degania Bet, Israel; cat. Nr: 602–175, outer diameter: 1.65 mm, inner diameter: 0.76 mm) cut at a length of 12 mm that was closed at both ends with Silastic™ glue (Silastic Medical Adhesive Silicone type A, Coventry, UK) leaving a length of 10 mm that was either filled with T or left empty. This type of capsules has been shown previously to establish in adult females circulating levels of T typical of sexually mature males (Nottebohm, 1980b) and to increase the sizes of song control nuclei in castrated males to levels characteristic of normal gonadally intact males (Appeltants et al., 2003). All males were transferred the same day into a long-day photoperiod (16L:8D) and placed in individual cages located in the same room so that birds were until the end of the experiment in visual (but not acoustic) isolation.

Singing of all subjects in experiments 1 and 2 was observed and quantified systematically by an observer (GéB) who was blind to the endocrine condition of the subjects. Quantification was carried out four times per day during 60 min (starting at 8:00, 11:00, 14:00 and 18:00) on days 14, 21 and 27 by methods that have been previously described in detail (Boseret et al., 2006). All birds were sacrificed during the day following the last behavioral observations (day 28). This time point was selected because we knew that HVC volume was significantly increased indicating that plasticity was occurring.

2.3.2. Perfusion and brain histology

Birds were first tranquilized by an injection of 25 μl Medetomidin (Domitor™; Pfizer, Louvain-la-Neuve, Belgium), which was followed 10 minutes later by a complete anesthesia induced by an injection of 25 μl of a mixture of zolazepam and tiletamine both at 50 mg/ml (Zoletil™; Virbac, Louvain-la-Neuve, Belgium). 50 μl of heparin (20 mg/ml) was injected into the left ventricle and birds were perfused through the left ventricle with saline followed by approximately 100 ml of fixative (4% paraformaldehyde with 0.1% glutaraldehyde in 0.1 M phosphate buffer saline [PBS]). The brain was removed from the skull, post-fixed in the same fixative without glutaraldehyde for at least one additional hour, cryo-protected in a solution of sucrose (30%) in PBS, frozen on dry ice and stored at −80°C. The completeness of castration and presence of Silastic ™ capsules were then checked in all subjects. The absence of testes was confirmed at autopsy in all males by careful dissection and inspection of the abdominal cavity. All birds were completely castrated except for one control male and his data were therefore not further considered.

Brains were cut in 30 μm coronal sections on a cryostat, from the level of the Locus Coeruleus (LoC) to the rostral end of Area X. Six series of alternate sections were collected and one of them was used for reelin visualization. All sections were stored in cryoprotectant at −20°C. One series of sections was also stained for Nissl material with toluidine blue to provide accurate anatomical localization.

2.3.3. Reelin immunocytochemistry

Immunocytochemistry was carried out on two sets of adjacent sections with one monoclonal antibody raised in mouse against the secreted N-terminal extremity of the glycoprotein Reelin (anti-Reelin 142) graciously donated by Prof. Andre Goffinet, Catholic University of Louvain (UCL), Woluwe St-Pierre, Bruxelles, Belgium. This primary antibody was previously used for visualizing reelin in the brain of numerous species belonging to all major classes of vertebrates from fishes to mammals (de Bergeyck et al. 1998; Goffinet et al. 1999; Smalheiser et al. 2000; Perez-Garcia et al. 2001; Martìnez-Cerdeño and Clascà 2002), including birds (Bernier et al. 2000). Its specificity has been repeatedly demonstrated and is widely accepted (see references above). The use of this Reelin antibody has also been previously described and validated in another songbird species, the European starling (Absil et al., 2003). The specificity of this antibody is also confirmed by the observation that the distribution of reelin-immunoreactive structures observed in the canary brain matches the distribution of the corresponding mRNA.

Floating sections were rinsed in PBS, containing 0.2% Triton X-100 (PBST), then immersed in a solution of 0.06% H2O2 to eliminate endogenous peroxidases. After 20 minutes, they were placed in blocking solution (Normal Goat Serum, cat.no. X-0907, Dakopatts; A/S Denmark) for 30 min and then incubated at 4°C overnight with the primary antibody overnight (anti Reelin diluted 1/250). Sections were rinsed in PBST and placed for 2 hours in a biotinylated Goat Anti-Mouse antibody (cat.no. E-0466, Dakopatts; A/S Denmark, dilution: 1/400) and then, after a further rinse exposed for 90 min to an Avidin-Biotin Complex coupled with horseradish peroxidase (Kit VectaStain ABC Elite Standard, cat. no. PK 6100, Burlingame, CA, USA). The sections were finally reacted in a solution of 0.04% of 3,3′-diaminobenzidin tetrahydrochloride (DAB; cat no, D5637, Sigma; St-Louis, MO, USA), rinsed in PBS and mounted on microscope slides in an aqueous gelatin-based medium.

2.3.4. Analysis of sections

Anatomical results described here were first obtained on the brain on these 13 birds. Additional observations of reelin-immunoreactive structures were also made on brain sections from additional males kept in similar but slightly different experimental conditions. No qualitative differences in the morphology or overall distribution of these structures could be detected between these birds.

All sections were first qualitatively observed with a Leica DMRB microscope to identify brain areas containing Reelin-immunoreactive (Reelin-ir) cells. Pictures of representative sections were then digitized through an Olympus BH2 microscope equipped with a firewire Leica DFC480 color video camera coupled to a MacIntosh micro-computer. Representative figures were prepared in Adobe Photoshop. No transformation of images was performed in the program except for adjustments of contrast and light intensity that were performed to equalize gray levels between different panels of a same figure.

The anatomical nomenclature used in this report are based on three avian brain atlases (canary: (Stokes et al., 1974); zebra finch: Nixdorf-Bergweiler and Bischof 2006: http://www.ncbi.nlm.gov/books/bv.fgci?rid=atlas) with additional anatomical information concerning the hypothalamus-preoptic areas and auditory or vocal control areas (see respectively (Balthazart et al., 1996) and (Bottjer et al., 1989, Vates et al., 1996, Bottjer and Johnson, 1997, Mello et al., 1998, Bottjer et al., 2000)). This nomenclature of brain structures was modified according to the recommendations provided by the Brain Nomenclature Forum (Reiner et al., 2004).

2.3.5. Quantitative studies

The numbers of densely labeled reelin-ir cells was counted by one of the experimenter (GéB) in several song control nuclei and in an equivalent control area located just outside the nucleus. Cells were counted in a standardized square area (200 × 200 μm or 0.04 mm2) located in a standardized manner within the selected area. This quantification method has been described previously in another study (Boseret et al., 2007). Specifically, reelin-ir cells were counted in HVC and in the adjacent nidopallium just ventral to HVC at three successive rostro-caudal levels, in the nucleus robustus arcopallialis (RA) and in the adjacent arcopallium jut lateral to this nucleus at two rostro-caudal levels, in area X and adjacent medial striatum just lateral to X (two rostro-caudal levels), and finally in the lateral part of the magnocellular nucleus of the anterior nidopallium (LMAN) and one adjacent area of the nidopallium at one rostro-caudal level. LMAN was identified in the sections stained by immunocytochemistry based on the adjacent sections that had been stained by toluidine blue for Nissl substance.

3. Results

3.1. Distribution of the reelin mRNA in the canary brain

The reelin mRNA was broadly expressed throughout the brain of male and female canaries. No qualitative sex difference in the pattern of expression could be detected, except for expression in and around song control nuclei (see below) and the following distribution thus applies to both sexes. The distribution of reelin mRNA was highly heterogeneous and allowed to outline many large brain areas on the autoradiograms as illustrated for representative sections through a female brain in Figure 1.

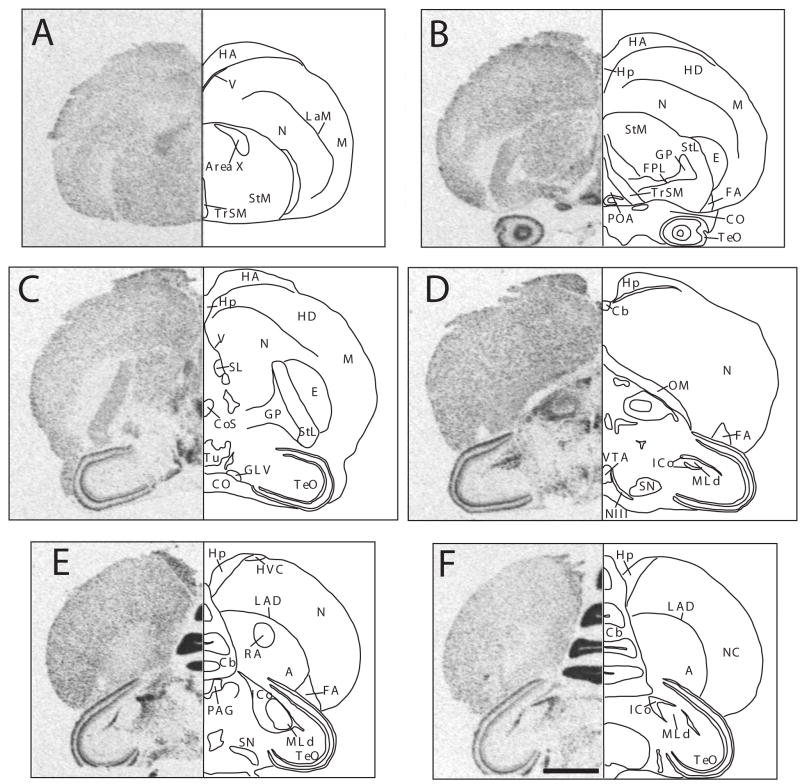

Figure 1.

Autoradiograms of coronal sections through a female canary brain processed by in situ hydridization for the reelin mRNA (left side of each panel) and mirror-image drawing presenting the interpretation of these autoradiograms and names of labeled structures. Panles A through F represent sections in a rostral to caudal order. Magnification bar: 2 mm.

Abbreviations: A: arcopallium; Area X: area X of the medial striatum; Cb: cerebellum; CO: chiasma opticum; CoS: nucleus commussuralis septi; E: entopallium; FA: tractus fronto-arcopallialis; FPL: fasciculus prosencephali lateralis; GLV: nucleus geniculatus lateralis, pars ventralis; GP: globus pallidus; HA: hyperpallium apicale; HD: hyperpallium densocellulare; Hp: hippocampus; HVC: song control nucleus HVC, used as a proper name; ICo: nucleus intercollicularis; LAD: lamina arcopallialis dorsalis; LaM: lamina mesopallialis; M: mesopallium; MLd: nucleus mesencephalicus lateralis, pars dorsalis; N: nidopallium; NIII: nervus occulomotorius (third nerve); OM: tractus occipitomesencephalicus; PAG: periaqueductal gray; NC: nidopallium caudale; POA: preoptic area; RA: nucleus robustus arcopallialis; SL: nucleus septalis lateralis; SN: substantia nigra; StL: striatum laterale; StM: striatum mediale; TeO: tectum opticum; TrSM: tractus sepatopallio-mesencephalicus; Tu: tuber; V: ventriculus; VTA: ventral tegmental area.

The densest expression was clearly observed in the granular layer of the cerebellum (Cb, Fig. 1E–F). Very dense label was also observed in a variety of structures including the hippocampus, the preoptic area (POA, Fig. 1B), the nucleus of the commisuralis septi (CoS, Fig. 1C), broad regions of the dorsal thalamus (Fig. 1D), the mesencephalic nucleus intercollicularis (ICo, Fig. 1D–F), two external layers of the optic tectum (TeO, Fig. 1B–F, corresponding to the most external and most internal cellular layers of the stratum griseum et fibrosum superficiale, SGFS), the ventral tegmental area (VTA, Fig. 1D) and substantia nigra (SN, Fig. 1D–E).

In contrast a very low or even an absence of expression was detected in brain regions such as the entopallium (E, Fig. 1B–C), the globus palidus (GP, Fig. 1 B–C), the nucleus mesencephalicus lateralis, pars dorsalis (MLd, Fig. 1E–F), internal layers of the optic tectum (TeO, Fig. 1 B–F) and all major fiber tracts such as the tractus septopallio-mesencephalicus (TrSM, Fig. 1B), the tractus fronto-arcopallialis (FA, Fig. 1B–E), the nervus oculomotorius (NIII, Fig. 1 D) or the chiasma opticum (CO, Fig. 1 B–C).

Differences in the density of reelin expression at most rostro-caudal levels also clearly differentiated large fields of the telencephalon as defined by a sharp contrast in hybridization signal usually corresponding to a boundary defined by a lamina. This distinction was, for example, most visible between the striatum mediale (StM) and the nidopallium (N) at the most rostral levels (Fig. 1 AB, separation corresponding to the lamina pallio-subpallialis, LPS) and more caudally between the arcopallium (A) and the adjacent nidopallium (N, Fig. 1 E–F, separation corresponding to the lamina arcopallialis dorsalis, LAD).

Relationship with song control nuclei

Interestingly, local differences in the density of reelin expression also allowed for a clear definition of the boundaries of most of the song control nuclei such that these nuclei are clearly visible in the autoradiograms. A much denser expression of reelin as compared to the surrounding striatum mediale (StM) was, for example observed in the song control nucleus area X (Fig. 2A–E) and this pattern of high reelin expression outlined area X throughout its entire rostro-caudal extent. At the level of the rostral tip of area X, just dorsal to the lamina pallio-subpallialis (LPS) another area of weak reelin expression was also present in the nidopallum (Fig. 2A). This area of weak reelin expression corresponds to the lateral part of the nucleus magnocellularis nidopalli anterioris (LMAN) and outlines LMAN boundaries by the contrast of low expression in the nucleus versus high expression in surrounding nidopallium.

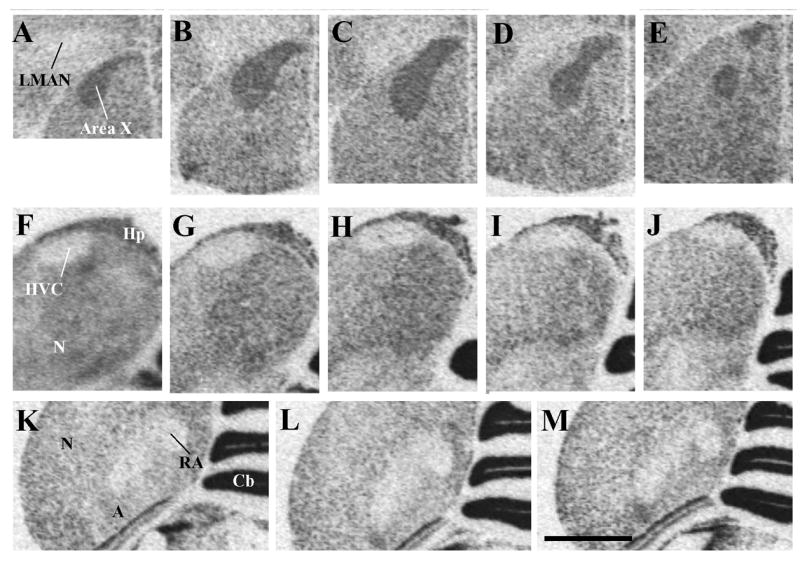

Figure 2.

Autoradiograms of coronal sections through a male canary brain processed by in situ hydridization for the reelin mRNA illustrating the higher density of reelin expression in the song control nucleus area X (panels A–E) compared to the surrounding striatum mediale (StM) but the much lower expression in HVC (panels F–J) and in nucleus robustus arcopallialis (RA, panels K–M) compared to the surrounding nidopallium (N) and arcopallium (A) respectively. Panels located on a same row and illustrating a given nucleus are presented from left to right in a rostral to caudal order.

Magnification bar: 2 mm. Abbreviations: A: arcopallium; Cb, cerebellum; Hp, hippocampus; HVC: song control nucleus HVC; LMAN: magnocellular nucleus of the anterior nidopallium; N: nidopallium; StM: striatum mediale;

A very low, generally undetectable, pattern of reelin expression was also observed in HVC (Fig. 2F–J) and in the nucleus robustus arcopallialis (RA, Fig. 2K–M) and allowed us to outline the boundaries of these two song control nuclei from the surrounding nidopallium (N) and arcopallium (A) respectively. This pattern of lighter expression compared to surrounding tissue defined the song control nuclei throughout their rostro-caudal extent. The low reelin density in RA also outlined a lateral “tail” of this nucleus named archistriatum (arcopallium) pars dorsalis by Johnson and Bottjer (Johnson et al., 1995) that extends in the ventro-lateral direction and was previously shown to specifically express high densities of alpha2-adrenergic receptors as detected by in vitro receptor binding autoradiography (Ball, 1990, Ball, 1994) a high number of cells immunoreactive from the androgen receptor (Balthazart et al., 1992).

The mesencephalic nucleus intercollicularis (ICo) was also clearly outlined by a specialized pattern of reelin mRNA expression. Both the dorso-medial region of this nucleus that forms a cap above the nucleus mesencephalicus lateralis, pars dorsalis (MLd) and its ventro-lateral part located ventrally with respect to MLd were sharply outlined by a dense expression of reelin leaving between them an ovoid structure nearly devoid of label and corresponding to MLd itself (Fig. 1E–F). Just medially to the ICo, another small dark spot of dense reelin mRNA expression was also identified that corresponds to the location of the nucleus uvaeformis (UVa). The triangular shape of this spot of dense expression suggested that the label was accumulated mostly on the medial part of UVa previously called the “horn” (Williams and Vicario, 1993) but the resolution of autoradiograms did not permit us to definitively ascertain this anatomical localization. This interpretation is, however, supported by our immunocytochemical results (see section 3.4).

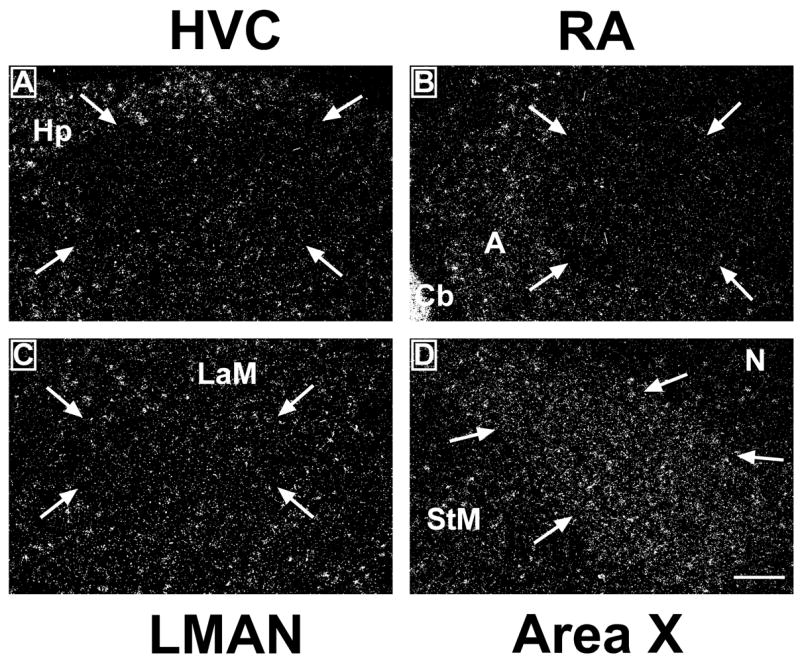

The specific anatomical localization of this regional variations in reelin expression and their correspondence with the song control nuclei themselves was later confirmed by reference to the adjacent Nissl-stained sections. Furthermore, a selection of sections labeled for reelin with 35S were, after the film autoradiography procedure, dipped in photographic emulsion and examined under darkfield illumination to reveal the pattern of reelin mRNA expression with a higher degree of cellular resolution. As illustrated in figure 3, the association of HVC, RA and LMAN with a lighter reelin expression and of area X and part of UVa with a denser reelin expression as compared to the surrounding tissue was clearly confirmed by these analyses.

Figure 3.

Darkfield photomicrographs of emulsion-dipped sections illustrating the expression of reelin within the telencephalic song control nuclei HVC (A), robust nucleus of the arcopallium (RA; B), lateral part of the nucleus magnocellularis nidopalli anterioris (LMAN; C) and Area X (D). Arrows indicate the boundaries of the brain regions. Pictures show the right brain hemisphere. Dorsal is at the top and lateral is on the right in these coronal sections. Abbreviations: A, arcopallium; Cb, cerebellum; Hp, hippocampus; LaM, Lamina mesopallialis; StM: striatum mediale. Magnification bar=200 μm.

3.2. Distribution of the Dab1 mRNA in the canary brain

It is now well established that a very active process of neurogenesis persists in the adult canary brain (Goldman and Nottebohm, 1983, Alvarez-Buylla et al., 1988) so that, for example, up to 1.5% of the neurons in HVC are still replaced each day in adult birds (Alvarez-Buylla and Kirn, 1997). Because reelin is thought to play a major role in determining the final position of migrating neurons, it was expected that a high expression of this protein would be found in the adult canary brain. However the expression of the reelin mRNA described above was by no means confined to areas displaying an intense neurogenesis and/or incorporating new neurons during adult life. These processes are generally confined to the telencephalon and do not occur, under normal physiological conditions in di-, mes-, and met-encephalic areas where a dense reelin expression had been observed. Some neurogenesis has, however, been observed in diencephalic areas in ring doves after hypothalamic lesions (Cao et al., 2002, Chen et al., 2006).

We reasoned that, possibly, reelin was broadly expressed in the brain but that the anatomical specificity of its action would be derived from a greater specificity of its receptors or of the intracellular signaling cascade that is supposed to mediate reelin action on neuronal migration and arrest. Disabled1 (Dab1) encodes an intracellular adapter that forms a key part of the intracellular signaling pathway mediating reelin action (Forster et al., 2006). Since this protein is not secreted and acts intracellularly through phosphorylation triggered by its interaction with occupied reelin receptors, it was hypothesized that an analysis of the neuroanatomical distribution of the Dab1 mRNA would provide an accurate view of the site of action for reelin in the adult canary brain.

In situ hybridization for Dab1 was performed on adjacent sections to those used for the reelin study in situ hybridization study just described. As observed for reelin, a very broad distribution of Dab1 was detected in the canary brain though the density of the hybridization signal was in general much lower: the exposure time to the autoradiography film had to be increased from 4 to 9 weeks to produce a signal that could be easily analyzed. As also observed for reelin, the Dab1 hybridization signal was distributed heterogeneously throughout the brain as illustrated in figure 4 presenting 6 representative adjacent sections from the same female as sections used to prepare figure 1.

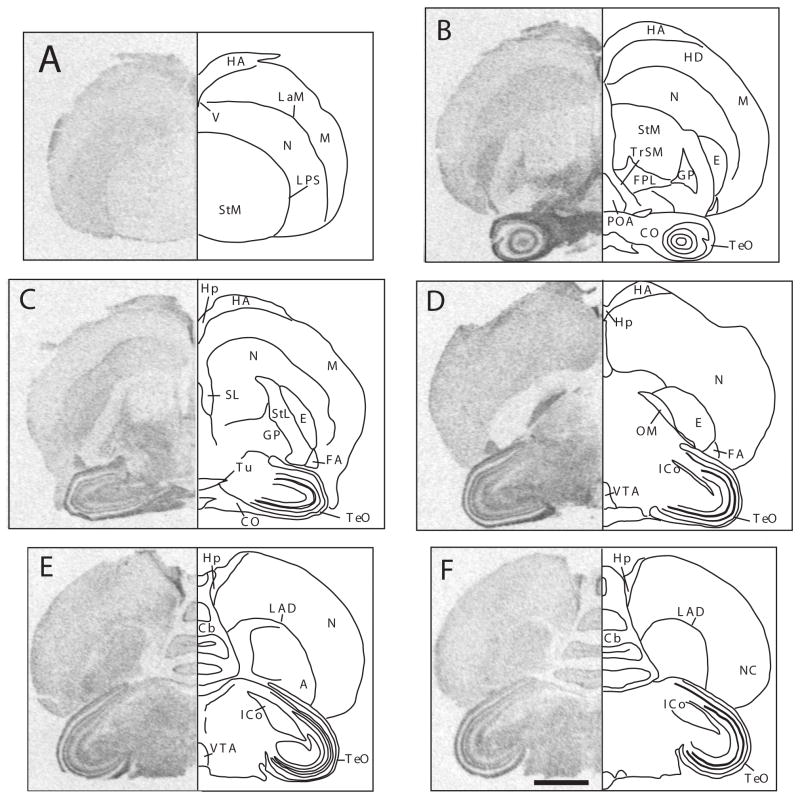

Figure 4.

Autoradiograms of coronal sections through a female canary brain processed by in situ hydridization for the Dab1 mRNA (left side of each panel) and mirror-image drawing presenting the interpretation of these autoradiograms and names of labeled structures. Panels A through F represent sections in a rostral to caudal order. The sections illustrated come from the same subject and are adjacent to sections labeled for reelin that are illustrated in figure 1. Magnification bar: 2 mm.

Abbreviations: A: arcopallium; Cb: cerebellum; CO: chiasma opticum; E: entopallium; FA: tractus fronto-arcopallialis; FPL: fasciculus prosencephali lateralis; GP: globus pallidus; HA: hyperpallium apicale; HD: hyperpallium densocellulare; Hp: hippocampus; ICo: nucleus intercollicularis; LAD: lamina arcopallialis dorsalis; LaM: lamina mesopallialis; LPS: lamina pallio-subpalllialis; M: mesopallium; N: nidopallium; OM: tractus occipitomesencephalicus; NC: nidopallium caudale; POA: preoptic area; SL: nucleus septalis lateralis; StM: striatum laterale; StM: striatum mediale; TeO: tectum opticum; TrSM: tractus sepatopallio-mesencephalicus; Tu: tuber; V: ventriculus; VTA: ventral tegmental area.

Interestingly however, the pattern of Dab1 distribution was not entirely similar to the pattern observed for reelin and actually represented in many brain regions its negative image: brain areas expressing high levels of reelin were often almost devoid of Dab1 expression and vice versa. For example, areas expressing a high density of reelin mRNA such as the preoptic area (Figs 1B and 4B), the striatum laterale (Figs. 1B–C and 4B–C), the dorsal thalamus (Figs. 1 D and 4D) or the nucleus intercollicularis (Figs. 1E–F and 4E–F) displayed no or only very low concentrations of Dab1 mRNA. In the cerebellum reelin was densely expressed in the granular layer while the densest expression of Dab1 was present in the Purkinje cells layer (Figs. 1E–F and 4 E–F).

Conversely, many areas that were almost devoid of reelin expression were associated with high concentrations of Dab1 mRNA. This was for example the case in the entopallium (Figs. 1 B–C and 4B–C), the globus pallidus (Figs. 1B–C and 4 B–C), and several internal layers of the tectum opticum, including the stratum griseum centrale (SGC) (Figs. 1B–F and 4B–F). This opposite distribution concerned also all major fiber tracts that were densely labeled for Dab1 but did not seem to contain any reelin mRNA (see for example the TrSM in Figs. 1 B and 4D or the CO in Figs 1B-C and 4B-C).

The major subdivisions of the telencephalon and the corresponding lamina separating them were also often visible in the Dab1 autoradiograms. These divisions are, for example, very well illustrated in panels B and C of figure 4 where the more densely labeled nidopallium clearly separates the striatum mediale from the more dorsal mesopallium (M) and hyperpallium densocellulare (HD) and that express both lower concentrations of Dab1 mRNA. This division at the same time clearly highlights the corresponding laminae, namely the lamina pallio-subpallialis (LPS) and the lamina mesopallialis (LaM). The hippocampus was highlighted by a dense expression of Dab1 mRNA throughout its rostro-caudal extent (Fig. 4B–E).

Contrary to what was observed for reelin, we could not detect any specific association of the Dab1 mRNA expression with any of the song control nuclei except for ICo which was, as already mentioned earlier, identified by a lower density of Dab1 expression as compared with the surrounding mesencephalon (Fig. 4 D–F). Area X, LMAN, HVC and RA could not be detected on the autoradiograms.

3.3. Distribution of reelin receptors mRNAs (ApoER2 and VLDLR)

Two lipoprotein receptor genes have been identified whose protein products mediate most, if not all, effects of reelin during cortical plate development in mammals: the very low density lipoprotein receptor (VLDLR) and the apolipoprotein E receptor 2 (ApoER2) also referred to as LR8B. Homologous sequences were easily identified in songbirds and were subsequently used to design in situ hybridization probes to detect the corresponding mRNAs in the canary brain. Previous experiments indicated that ApoER2 exhibits a six-fold higher affinity for reelin than the VLDLR (dissociation constant of 0.2 vs. 1.2 nM) (Forster et al., 2006). Therefore our analyses of reelin receptors mRNA expression in the canary brain focused on this higher affinity receptor.

The neuroanatomical distribution of the ApoER2 mRNA was in many respects similar to the distribution of reelin (See Fig. 5). Both were, for example, less densely expressed in the entopallium and globus pallidus than in surrounding areas such as the striatum laterale (Fig. 5 panels A1–2 and B1–2). Both were in contrast densely expressed in the same external layers of the tectum opticum and in the striatum mediale (Fig. 5 panels A1–2 and C1–2). In the cerebellum, however, a differential pattern of labeling was observed. The dense reelin expression was located in the granular layer while the densest ApoER2 expression was more discrete and confined to the Purkinje cell layer.

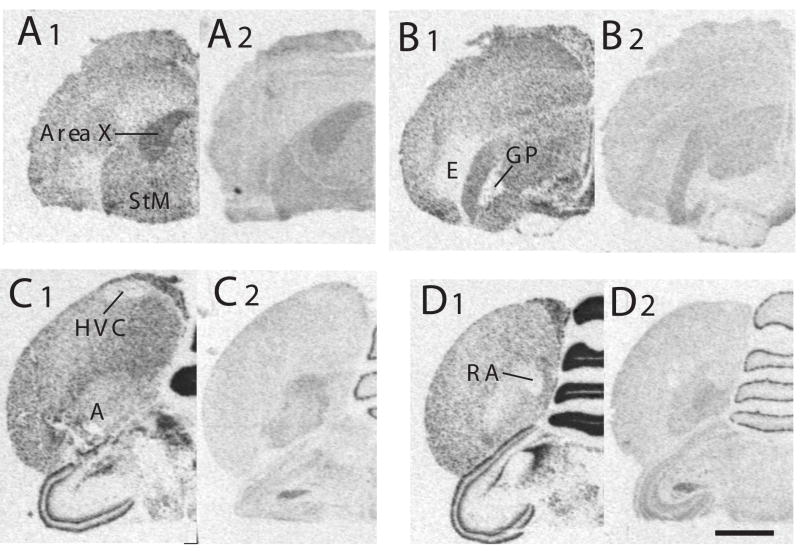

Figure 5.

Autoradiograms of coronal sections through the brain of a male canary processed by in situ hydridization for the reelin (A1, B1, C1, D1) or ApoER2 (A2, B2, C2, D2) mRNA. Panels A through D represent sections in a rostral to caudal order. The sections illustrated in panels designed by a same letter come from adjacent sections from the same subject. Magnification bar: 2 mm. Abbreviations: A: arcopallium; GP: globus pallidus; HVC: song control nucleus HVC; RA: nucleus robustus arcopallialis; StM: striatum mediale.

The two types of mRNA also identified the boundaries of several song control nuclei by a differential density of expression as compared with the adjacent tissue. Area X and the mesencephalic nucleus intercollicularis were both identified in the autoradiograms by a denser expression of reelin and of ApoER2 than in the striatum mediale or in the mesencephalon and MLd respectively (Fig. 5A1–2, C1–2 and D1–2). Conversely, HVC and RA were less densely labeled than surrounding tissue in sections hybridized with probes for both reelin and ApoER2. This differential label was however more clearly identified in the case of reelin than for its receptor (Fig. 5 C1–2 and D1–2).

The VLDLR mRNA distribution was investigated in the brain of one male and one female and the reliability of the corresponding observations is therefore more limited. These autoradiograms indicated however a number of similarities with the distribution of reelin or of ApoER2. In all cases a denser expression was for example observed in the striatum laterale as compared with the adjacent entopallium and globus pallidus (see Fig. 6B–D). A clear definition of the large subdivisions of the telencephalon was also present. Some specificity of the VLDLR distribution was, nevertheless, detectable for example in the optic tectum where the labeled layers included the layers that were also densely labeled for reelin or ApoER2 (most external and internal parts of SGFS) but also several more internal layers overlapping with SGC and even with more internal structures of the optic tectum. Additionally, in the cerebellum, the VLDRL mRNA expression was, like for reelin, particularly dense in the granular layer unlike what was observed for ApoER2, which was mainly expressed in the Purkinje cell layer.

Figure 6.

Autoradiograms of coronal sections through the brain of a male canary processed by in situ hydridization for VLDLR. Magnification bar: 2 mm. Abbreviations: A: arcopallium; Cb: cerebellum; GP: globus pallidus; HA: hyperpallium apicale; Hp: hippocampus; M: mesopallium; N: nidopallium; NC: nidopallium caudale; StL: striatum laterale; StM: striatum mediale; TeO: tectum opticum.

3.4. Distribution of reelin-immunoreactive structures in the canary brain

The relatively important discrepancy between the distribution of reelin and Dab1 mRNA described by in situ hybridization raised a number of questions regarding the physiological significance of this protein and its hypothesized intracellular signaling pathway. In addition, the distribution of reelin mRNA observed here in the canary brain appeared to be broader and thus did not match perfectly with the distribution of the reelin protein previously described by immunocytochemical methods in the brain of European starlings (Sturnus vulgaris)(Absil et al., 2003). Based on available evidence, it is impossible at this time to know whether this represents a genuine species difference or a difference related to the physiological condition of subjects in the two species that were investigated. Additionally, a slight difference in antibody cross-reactivity cannot be excluded but appears unlikely since the primary antibody used in these studies has been shown to cross-react with reelin in representative species of all vertebrate classes.

The reelin protein is known to be secreted by neurons and act on adjacent migrating cells. The protein is also presumably transported to the end of axonal fibers, where it is released and acts on neuronal movements. This action could thus take place at sites relatively distant from the cell bodies producing the protein and expressing the corresponding mRNA. We therefore decided to investigate by immunocytochemistry whether the reelin protein was actually found in the same brain locations as the reelin mRNA in the canary brain.

Immunostaining revealed only one type of reelin-immunoreactive (reelin-ir) cells that were present in high numbers in broad areas of the telencephalon as well as in clearly defined areas of the di-, mes- and met-encephalon. The reelin-ir cells had a spherical or ovoid shape (usually 10–14 μm in diameter, with a cytoplasm densely filled with immunoreactive material. The round nucleus was not stained and appeared as a clear spot in the middle of the dark perikaryon (Fig. 7D insert). Processes associated with these cells did not contain imunoreactive material except at their most proximal end and no reelin ir-fibers were visible in any part of the brain.

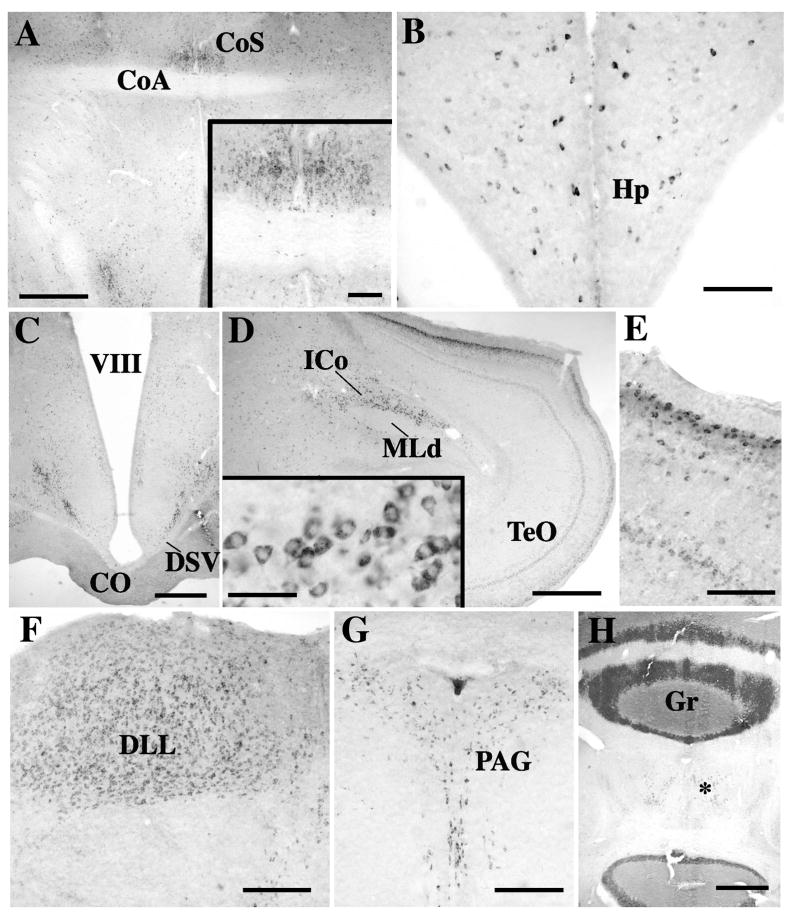

Figure 7.

Photomicrographs illustrating the distribution of reelin-ir cells in the canary brain. A. Preoptic area at the level of the anterior commissure. The nucleus of the commisuralis septi (CoS), just dorsal to the commissural anterior (CoA) is clearly highlighted by a dense cluster of positive cells (also shown at higher magnification in the insert). B. Scattered cells are present in the hippocampus (Hp). C. Low densities of positive cells are detected throughout the hypothalamus. In the infundibular hypothalamus two clusters of reelin-ir cells for diagonal bands just dorsal to the chiasma opticum (CO) and the decussatio supraoptica ventralis (DSV). D. In the mesencephalon, two layers of the optic tectum (TeO) contain high density of positive cells. In the tegmentum the nucleus intercollicularis (ICo) is highlighted by a dense cluster of positive cells. These cells are also shown at higher magnification in the insert. E. Higher magnification of a fragment of the optic lobes illustrating the two layers of positive cells surrounding the nucleus mesencephalicus lateralis, pars dorsalis (MLd). F. The nucleus dorsolateralis anterior thalami, pars lateralis (DLL) is entirely filled by reelin-ir cells. G. Positive cells outline the entire periqueductal gray (PAG). H. In the cerebellum a very dense immunoreactive material is present in the granular layer (Gr) and in the Purkinje cells. Reelin-ir cells are also observed in the deeper layers (asterisk). Magnification bars: 500 μm in A, C, D, H; 50 μm in the insert of panel D; 100 μm in insert of panel A, in B, E, 200 μm in F, G.

Photomicrographs illustrating a few key brain areas that contained a high density of immunoreactive cells are presented in figures 7 and 8.

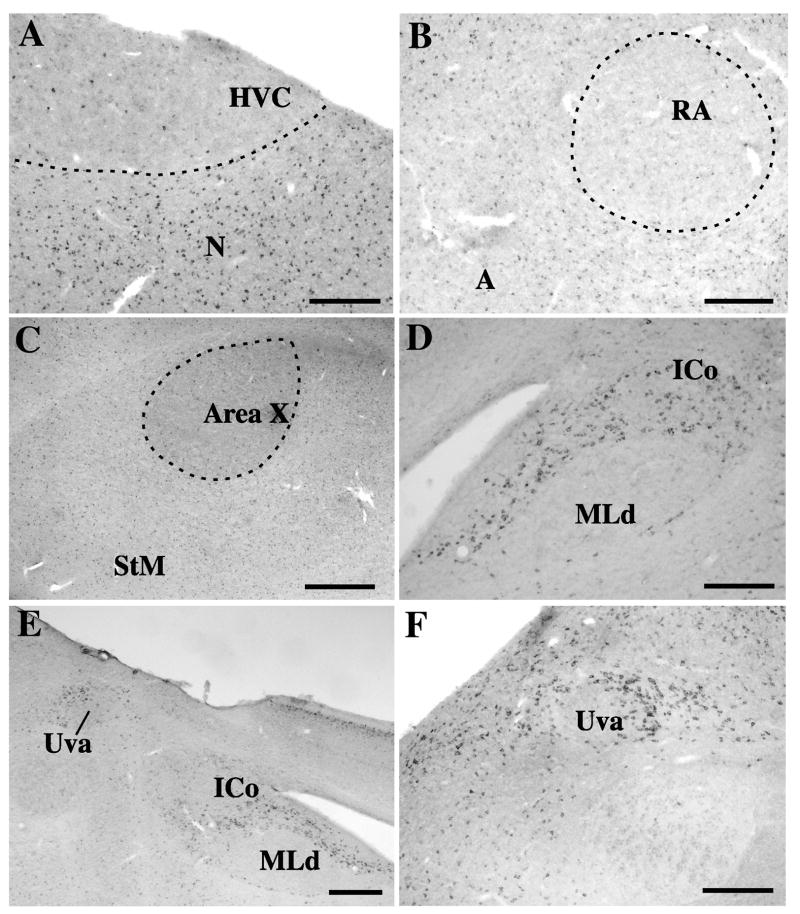

Figure 8.

Photomicrographs illustrating the distribution of reelin-ir cells in and around the song control nuclei of the canary brain. A. HVC and adjacent nidopallium (N). B. nucleus robustus arcopallialis (RA) and adjacent arcopallium (A). C. area X and striatum mediale (StM). D. Nucleus intercollicularis (ICo) surrounding almost completely the nucleus mesencephalicus lateralis, pars dorsalis (MLd). E. low power enlargement of the medial part of the tegmentum containing the ICo, MLd and nucleus uvaeformis (Uva). F. High power magnification illustrating the reelin-ir cells sourounding nucleus Uva. Magnification bars: 200 μm in A, B; D, and F, 500 μm in C and E.

A very high density of reelin-ir cells was observed throughout the pallial part of the telencephalon, including the nidopallium (Fig. 8A) and nidopallium caudale, mesopallium and hyperpallium densocellulare and apicale (HA). The arcopallium (Fig. 8B), hippocampus (Fig. 7B) and area parahippocampalis also contained a large number of reelin-ir cells throughout their rostro-caudal extent but the density of these cells was clearly lower than in the nidopallium.

The striatum mediale (StM) contained a homogeneous population of reelin-ir cells throughout its rostro-caudal length (Fig. 8C). Immunostained perikarya were visible in large numbers in the nucleus septalis lateralis (SL) and to a lesser extent in the nucleus septalis medialis (SM). A very dense group of heavily labeled reeelin-ir cells was detected just above the anterior commissura anterior (CoA) at the level of the nucleus of the commisuralis septi, CoS (Fig. 7A)

A relatively low density of reelin-ir cells was present throughout the hypothalamus except for a few well-defined areas where dense clusters of positive cells could be detected. These groups of positive cells were usually located in a periventricular position and overlapped at their rostral end with the paraventricular nucleus without defining its boundaries. A more lateral dense band of reelin-ir cells was also consistently present in the throughout the caudal part of hypothalamus where it formed a diagonal band parallel to the dorsal edge of the decussatio supraoptica dorsalis (DSV; Fig. 7C). The medial preoptic area and tuberal part of the hypothalamus were in contrast specifically characterized by dense clusters of reelin-ir cells. Most of the dorsal thalamus and in particular its most lateral part, the nucleus dorsolateralis anterior thalami, pars lateralis (DLL) was also outlined by a dense cluster of reelin-ir cells (Fig. 7F).

Two layers of the optic tectum (within SGFS) contained dense populations of reelin-ir cells (Fig. 7D–E) as did the medial and lateral parts of the mesencephalic nucleus intercollicularis (Figs. 7D, 8D–E). Groups of reelin-ir cells were also present at the level of several mes- and met-encephalic nuclei such as the periaqueductal gray (PAG, often to as the griseum centrale in birds, Fig. 7G), the ventral tegmental area (VTA) and the substantia nigra (SN). An extremely high density of immunoreactive material was visible in the granular layer of the cerebellum where the density of immunoreactive structures usually prevented the identification of their exact morphological nature (Fig. 7H). Positive cells were also present in the Purkinje layer of cells.

Relationship with song control nuclei

As observed by in situ hybridization studies of the reelin mRNA distribution, very specific anatomical patterns based on the distibution of reelin-ir cells could be detected within most of the song control nuclei. While the entire nidopallium was filled with a high density of reelin-ir cells, nucleus HVC was almost entirely devoid of this protein and only a few rare scattered reelin-ir cells could be detected within its boundaries (Fig. 8A). A fairly similar situation was observed for nucleus RA that contained significantly fewer reelin-ir cells than the surrounding arcopallium (Fig. 8B). However, given that the density of reelin-ir staining is lower in the arcopallium than in the nidopallium, the boundaries of RA could not be so clearly defined by the lack of reelin-r cells as was the case in HVC (compare Fig. 8A and B).

The song control nuclei LMAN and MMAN could not be recognized in sections stained by immunocytochemistry but based on adjacent Nissl-stained sections, it was confirmed that these nuclei contain scattered populations of positive cells that could not be distinguished from the labeling in the surrounding tissue. Area X and the adjacent StM contained a fairly dense population of reelin-ir cells (Fig. 8C). There was in addition an amorphous staining that was denser within area X than in the surrounding StM. Whether this staining relates to protein released out of the cells or has a non specific nature could not be really ascertained with the available data.

Finally, nucleus ICo and the adjacent nucleus uvaeformis (Uva) were characterized by the presence of a high density of strongly labeled reelin-ir cells (Fig. 7D, 8 D–E). The entire ICo from its most medial to its most lateral aspects was outlined by a dense cluster of reelin-ir cells throughout the rostro-caudal extent of the nucleus. Uva was in contrast rather highlighted by a group of positive cells that were located around the nucleus and formed a “cap” around it that was especially dense on the dorso-medial side (Fig. 8F). This area adjacent to Uva has been previously described as the “horn” and seem to have the same connections as Uva itself based on electrophysiological recordings (Williams and Vicario, 1993). This “cap” of reelin-ir cells was, however, not completely outside Uva and it overlapped partly with the nucleus.

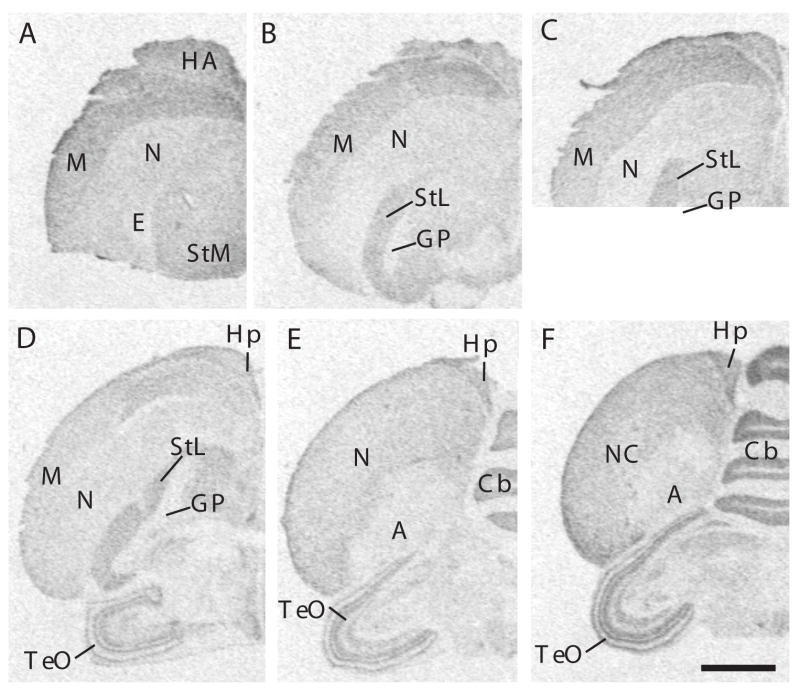

To further support the anatomical specialization of several song control nuclei regarding reelin distribution, the numbers of reelin-ir cells were counted in a standardized manner in and immediately outside of HVC, RA, area X and LMAN. These data were collected in a total of 13 castrated males among which 7 had been treated with exogenous testosterone and 6 had been left as untreated controls. As expected, testosterone-treated birds sang significantly more frequently during this experiment than untreated castrates (216±46 vs. 4±3 songs during the entire recording period, F1,11= 45.555, p<0.0001). Their HVC and RA volume was also significantly increased by respectively 59 and 58 % (both effects being significant for p<0.05).

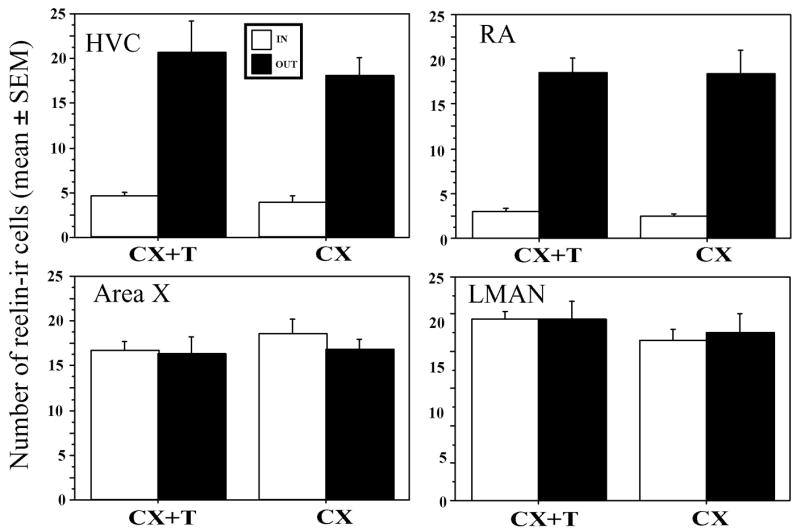

A first analysis by two or three-way ANOVAs of these numbers of reelin-ir cells with models including the endocrine treatment as independent variable, the localization in or out of the nucleus as a repeated factor and, for HVC, RA and area X, the different rostro-caudal levels of study as another repeated factor identified no effect of the location in the rostro-caudal axis and no significant interaction of this factor with the others (all p>0.10). Data collected at different levels were therefore averaged and reanalyzed by 4 two-way ANOVAs, one for each nucleus. In all 4 nuclei, no effect of the testosterone treatment and no interaction of this treatment with the localization in or out of the song control nucleus could be detected (all p≥0.32). As expected from the qualitative analysis of the sections, the numbers of reelin-ir cells were found to be significantly smaller in HVC and in RA that in the adjacent samples (F1,11=61.966, p<0.0001 and F1,11=136.150, p<0.0001 respectively, see Fig. 9). Such a difference was, however, not present in area X nor in LMAN that could not be clearly distinguished by the density of reelin-ir structures in the sections (p>0.51).

Figure 9.

Bar graph illustrating the number of reelin-ir cells inside the 4 song control nuclei HVC, RA, area X and LMAN and in the surrounding tissue just adjacent to the nuclei and effects of the treatment with testosterone on the numbers of these cells in castrated males. Significantly fewer cells are found in HVC and RA than in surrounding tissue but this difference is not observed for area X and MAN. No effect of testosterone could be detected.

4. Discussion

We identified here by immunocytochemistry and in situ hybridization histochemistry a widespread distribution in the canary brain of the reelin protein, of its messenger RNA and of the mRNAs encoding for the reelin receptors and intracellular signaling protein, Dab1. These different mRNAs and protein did not display a similar gross neuroanatomical distribution and were not clearly associated, in an exclusive manner, with the brain areas that incorporate new neurons in adulthood as might have been expected based on the role played by reelin in brain development. The density of reelin-ir structures also did not seem to be affected by four weeks of treatment with exogenous testosterone. Nuclei in the song control system were characterized by a consistent pattern of either high or low reelin expression as compared to surrounding brain areas. These observations tend to rule out a number of hypotheses that had been presented previously based on the finding that, in starlings, the density of reelin-ir structures was increased in HVC following a treatment with exogenous testosterone (Absil et al., 2003). They also suggest a number of potential roles for reelin in the adult songbird brain that should now be experimentally tested.

The distribution of reelin that was identified here in the canary brain both by immunocytochemistry and by in situ hybridization for the corresponding mRNA is relatively similar to the distribution previously reported in another songbird species, the European starling. In both species, this glycoprotein is broadly expressed in large areas of the telencephalon and in specialized structures within the di-, mese-, and met-encephalon. At a finer level, these areas of high expression also seem to be similar in canaries and starlings. For example a high reelin expression is found in the ICo of both species. The overall density of reelin-ir cells in the telencephalon appears however to be higher in canaries than in starlings but it is impossible with the available information to ascertain whether this represents a true biological difference or an experimental artifact due to a differential cross-reactivity of the antibody in both species or even to minor differences in the staining procedure. In general, it appears however that the distribution of reelin has been relatively well conserved among songbirds, at least at the qualitative level. The widespread distribution of the Reelin protein and mRNA in pallial areas in adult canaries reported in this study is in general agreement with reports in mice that the Reelin protein is widely observed in layers 1 through 6 of the cortex (Ikeda and Terashima, 1997; Alcantara et al., 1998). These pallial areas are thought to be homologous to the mammalian cortex (Jarvis et al., 2005). Reelin is also observed with a high level of expression in the hippocampus of adult mice as we observed in this study in canaries (Ikeda and Terashima, 1997; Alcantara et al., 1998). Less attention has been paid to Reelin expression in the diencephalon and mesencephalon of mice but it has been reported that there relatively little expression in these brain regions (Alcantara et al., 1998).

Cells expressing the mRNA for the intracellular protein Dab1 were often not co-expressed in the brain areas displaying high densities of reelin mRNA but were present in other brain regions expressing low levels or no reelin mRNA. Because Dab1 is an intracellular protein that is not secreted, one expects the protein to be present specifically in the cells that also express the corresponding mRNA. In contrast, reelin is secreted in the extracellular space and could act at some distance from the cells that express reelin mRNA. Immunocytochemical analyses demonstrated however that the reelin-ir protein is generally localized in the same brain areas as the reelin mRNA. These data do not support the idea that Reelin and Dab1 are observed in different brain areas because reelin is synthesized in one area but acts at a more distant site. However even though the Dab1 protein is not excreted, it could still be localized and act in the terminals of neurons that express the corresponding mRNA. These terminals could well be located in brain areas that are somewhat distant of the corresponding cells bodies. This explanation could therefore contribute to explain the discrepancy between the distributions of reelin and Dab1.

The available literature suggests that Dab1 mediates the effects of reelin on cell migration and brain organization during ontogeny, but the mode of action of reelin on other physiological response in adulthood (see below) does not necessarily involve Dab1. Because the anatomical data collected here suggest that reelin action in the adult canary brain is not solely associated with the migration and recruitment of new neurons, it is therefore not necessarily required that reelin and Dab1 be co-expressed and co-localized.

In contrast, the in situ hybridization studies performed here suggest that the two reelin receptors, VLDLR and ApoER2, are expressed in the same brain areas as reelin. Although this conclusion is still preliminary and would need to be confirmed by more extensive studies, this coexistence supports the notion that reelin action, even in the adult brain, is mediated by the same receptors as during ontogeny. These two reelin receptors do not only interact with this signaling protein but rather have broader functions in the brain. VLDLR for example is implicated in the metabolism of several classes of lipoproteins (Oka et al., 1994) while ApoER2 plays a role in endocytosis and signal transduction (Petit-Turcotte et al., 2005, Fuentealba et al., 2007). One would expect their distribution to be more widespread than the distribution of reelin, in parallel with their more diversified role.

The most striking observation in this study is certainly the much higher or much lower expression of reelin in the song control nuclei than in adjacent structures as detected both at the mRNA and protein levels. All song control nuclei exhibit a particular pattern of reelin expression throughout their rostro-caudal extent as compared with the surrounding adjacent tissue. For example, in situ autoradiographic studies demonstrated a denser expression of reelin mRNA in area X, in ICo and in UVa as compared with adjacent structures. In contrast, HVC, RA and LMAN were characterized by a low reelin expression while the surrounding nidopallium or arcopallium displayed a high expression of this message. A similar pattern of reelin mRNA expression was recently reported for the zebra finch brain (Li et al., 2007) This differential expression was also observed when we labeled the reelin protein for many of these nuclei (HVC, RA, ICo, and UVa) but immunocytochemical data were less clear for area X and LMAN. The functional significance of this anatomical association is not fully understood but specific hypotheses can be proposed.

We initiated these studies based on the hypothesis that reelin could play a key role in determining the final position of migrating neurons in HVC and adjacent telencephalic (nidopallial) areas in the adult canary brain as it does in developing mammals. In agreement with this idea, reelin and its receptors were found to be more or less densely expressed throughout the telencephalon (but not in HVC, see below), where incorporation of new neurons has been observed in adult songbirds (Goldman and Nottebohm, 1983, Nottebohm 1985, Alvarez-Buylla et al., 1988) and birds from other orders (Ling et al. 1997) but are not so densely expressed in other parts of the brain where neurogenesis has not been described in physiological conditions and is observed only at low levels after experimental lesions (Cao et al., 2002, Chen et al., 2006). In the di-, mes-, and met-encephalon, reelin is indeed expressed at significant densities only in specific nuclei.

This anatomical correlation between reelin expression and neurogenesis/neuronal incorporation is, however, not so obvious upon a more detailed examination of the pattern of distribution. Firstly, the song control nucleus HVC, which is known to incorporate large numbers of new neurons throughout the adult life, only contains low numbers of cells expressing reelin expression and can actually be delineated fairly accurately from the adjacent nidopallium by this relative absence of the protein and of the corresponding mRNA. Why a protein that is supposed to determine the final positioning of neurons would be absent in the nucleus clearly characterized by a high degree of neuronal incorporation is certainly difficult to explain especially because this absence of expression was observed both at the mRNA and the protein level and may also concern at least one type of reelin receptor, the ApoER2. One might speculate that reelin expression is only up-regulated in HVC at specific times that were not targeted by the present experiments. Studies in mammals indicate that expression of this protein is not constitutive but is affected by various stimuli such as tissue injury (Pulido et al., 2007) or during psychiatric diseases (Fatemi, 2005b). Furthermore reelin might be expressed only very transiently by a small subset of cells that guide neuronal replacement. Additional work analyzing the dynamic of reelin expression in HVC is clearly needed to evaluate these possibilities

Interestingly a very dense expression of reelin was identified in area X that is known to incorporate new neurons in adulthood but a complete absence of expression was observed in RA, a song control nucleus where seasonal plasticity is clearly NOT related to the incorporation of new neurons but rather to changes in cell size and cell spacing (Tramontin and Brenowitz, 2000, Thompson and Brenowitz, 2005). Considering that reelin is densely expressed in a large numbers of brain nuclei where no neurogenesis has even been described, including the song control nuclei UVa and ICo, one must come to the conclusion that if reelin plays a role in neuronal recruitment in the adult canary brain, this is only one of its many function that concerns just a small fraction of the reelin expressing cells.

It has been shown that in the adult mammalian brain, reelin is also implicated in various forms of neural plasticity such radial glial fibers differentiation or changes in dendritic spine density and branching of dendrites (e.g., Pappas et al., 2001, Forster et al., 2002, Frotscher et al., 2007). This represents another potential and likely role for reelin in the adult canary brain in particular in the hippocampus considering the relatively dense expression of the reelin and Dab1 mRNA (Fig. 1E-F and Fig. 4C-E) and of the reelin protein (Fig. 7B) in this structure.

One important observation in the present study concerns the specific anatomical association of a high or low reelin expression with song control nuclei. Given that no obvious relationship can be established at this stage between the density of reelin expression and the presence absence of new neuron incorporation in each nucleus, we suggest that an alternative explanation of this anatomical relationship should be derived from the reported role of reelin in modulating dopaminergic and glutamatergic neurotransmission. A marked decrease in methamphetamine-induced locomotor activity is observed in reeler mice and relates directly to a decrease in D1 and D2 receptor mediated dopaminergic function while the presynaptic dopamine release remains essentially unchanged. The expression of these receptor subtypes is indeed decreased in reeler mice as demonstrated by binding experiments. Furthermore, injection of an antibody against reelin also reduced in adult mice the methamphetamine-induced hyperlocomotion indicating that reelin action on dopaminergic systems is not only taking place during development but continues to be important even in adult subjects (Matsuzaki et al., 2007). Reelin also plays a major modulatory role in the synaptic plasticity mediated by glutamatergic neurotransmission mediated the NMDA (N-methyl-D aspartate) and AMPA (α-amino-3-hydroxy-5-methylisoxazole-4- propionic acid) receptor subtypes. Application of reelin to the adult mice brain leads to enhanced NMDA- and AMPA-mediated transmission although pharmacological experiments indicate that both effects are not mediated by the same mechanisms (Qiu et al., 2006). It is thus tempting to relate these functions to the well-known specialization of the song system as far as dopaminergic and glutamatergic neurotarnsmission is concerned.

Chemical neuroatomy studies have shown that most song control nuclei represent groups of neurons that have acquired a chemical specialization by comparison to the neighboring structures (see (Ball, 1994, Ball and Balthazart, 2007) for review). Many song control nuclei for example express high densities of androgen receptors (HVC, RA, ICo, LMAN, nXII..) or of estrogen receptors (HVC, ICo, …). They are also specifically innervated by a number of peptides such as met-enkephalin or vasoactive intestinal polypeptide and can often be identified by the presence of a dense network of fibers containing enzymes involved in neurotransmitter synthesis such as tyrosine hydroxylase, the rate limiting step in the formation of the catecholamines dopamine and norepinephrine (see (Ball and Balthazart, 2007)for a recent review). In male canaries, HVC, RA, LMAN and area X can for example be identified from the surrounding tissue by a dense network of tyrosine hydroxylase-immunoreactive fibers (Appeltants et al., 2001). In vitro quantitative receptor binding autoradiography and in situ hybridization have also identified specialized expressions of neurotransmiters receptors in the song control nuclei. Muscarinic cholinergic receptors are, for example, expressed at higher density in HVC, area X and ICo but at lower density in RA than in surrounding areas (Ryan and Arnold, 1981, Bernard et al., 1993). Similarly, a high density of alpha2-noradrenergic receptors outlines all these nuclei (HVC, RA, area X and ICo) and allows identifying their borders in a manner consistent with their delineation in Nissl stained sections (Bernard et al., 1993, Bernard and Ball, 1995). This pattern of receptor expression does not however fit exactly with the expression of reelin described here (lower density in HVC, RA and LMAN but higher density in area X than in surrounding tissue).

In contrast, there is a surprisingly close match between the expression of reelin and of some glutamatergic receptors (Aamodt et al., 1992) in all these song control nuclei. It was originally reported by Aamodt and collaborators that NMDA receptors as identified by tritiated MK-801 binding are present in lower density than in the surrounding tissue in HVC, RA and LMAN but at higher density in area X (at least in some males) than in the surrounding medial striatum (see detail in (Aamodt et al., 1992)). This pattern perfectly matched the differential reelin expression in these 4 song control nuclei by comparison with the surrounding brain structures. In a subsequent study based on in situ hybridization and on binding experiments with a more specific ligand (tritiated ifenprodil), it was reported, however that the NMDA receptor 2B subunit (NR2B) is expressed at lower density in area X than in the medial striatum (Basham et al., 1999) leaving unexplained the original finding of a higher density of MK-801 binding sites in area X.

A recent systematic screening by in situ autoradiography of the expression of more than 20 glutamate receptor subunits/subtypes confirmed the higher expression of NR2B in all four song control nuclei (HVC, RA, LMAN and area X) and additionally demonstrated that the GluR1 AMPA subunit is differentially expressed in song control nuclei with a pattern that matches perfectly the differential expression of reelin, i.e. a denser expression than in surrounding tissue in area X but a lighter expression in HVC, RA and LMAN (Wada et al., 2004).

This differential expression of reelin and NMDA or AMPA receptors might be a mere coincidence but considering that reelin interferes with NMDA- and AMPA-mediated transmission (Qiu et al., 2006), there are reasons to believe that these two patterns of neuroanatomical distribution are causally related. These relationships could reflect the role of reelin in glutamatergic neurotransmission but could also conversely reflect a role of glutamate on reelin expression. There is indeed a growing body of evidence indicating that neurotransmitter receptors regulate aspects of brain development such as neuronal migration (Heng et al., 2007) and in as well as the expression of specific genes, such as the brain derived neurotrophic factor, BDNF (West et al., 2001) via cell signaling transduction cascades(Sheng and Greenberg, 1990, Bading, 1999). Future research should now address the functional significance of reelin expression in the adult canary brain and the causes and functions of the specific expression of reelin in the song control system.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health (R01 NS 35467) to GFB and the Belgian FRFC (2.4562.05) to JB. We thank the late Dr. Reinhold Metzdorf (Max Planck Institute for Ornithology, Seewiesen, Germany) for help in cloning the songbird reelin, Dab1, VLDLR and ApoER2 fragments and Professor André Goffinet (University of Louvain Medical Scholl, Brussels, Belgium) for kindly providing the reelin antibody and for generous intellectual help and support throughout the studies.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Aamodt SM, Kozlowski MR, Nordeen EJ, Nordeen KW. Distribution and developmental change in [3H]MK-801 binding within zebra finch song nuclei. J Neurobiol. 1992;23:997–1005. doi: 10.1002/neu.480230806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Absil P, Pinxten R, Balthazart J, Eens M. Effects of testosterone on Reelin expression in the brain of male European starlings. Cell Tissue Res. 2003;312:81–93. doi: 10.1007/s00441-003-0701-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alcantara S, Ruiz M, D’Arcangelo G, Ezan F, de Lecea L, Curran T, Sotelo C, Soriano E. Regional and cellular patterns of reelin mRNA expression in the forebrain of the developing and adult mouse. J Neurosci. 1998;18:7779–7799. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.18-19-07779.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alvarez-Buylla A, Kirn JR. Birth, migration, incorporation, and death of vocal control neurons in adult songbirds. J Neurobiol. 1997;33:585–601. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alvarez-Buylla A, Nottebohm F. Migration of young neurons in adult avian brain. Nature. 1988;335:353–354. doi: 10.1038/335353a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alvarez-Buylla A, Theelen M, Nottebohm F. Birth of projection neurons in the higher vocal center of the canary forebrain before, during, and after song learning. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1988;85:8722–8726. doi: 10.1073/pnas.85.22.8722. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Appeltants D, Ball GF, Balthazart J. The distribution of tyrosine hydroxylase in the canary brain: demonstration of a specific and sexually dimorphic catecholaminergic innervation of the telencephalic song control nuclei. Cell Tissue Res. 2001;304:237–259. doi: 10.1007/s004410100360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Appeltants D, Ball GF, Balthazart J. Song activation by testosterone is associated with an increased catecholaminergic innervation of the song control system in female canaries. Neuroscience. 2003;121:801–814. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(03)00496-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bading H. Nuclear calcium-activated gene expression: possible roles in neuronal plasticity and epileptogenesis. Epilepsy Res. 1999;36:225–231. doi: 10.1016/s0920-1211(99)00053-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ball GF. Chemical neuroanatomical studies of the steroid-sensitive songbird vocal control system: a comparative approach. In: Balthazart J, editor. Hormones, Brain and Behaviour in Vertebrates. 1. Sexual Differentiation, Neuroanatomical Aspects, Neurotransmitters and Neuropeptides Comp Physiol. Vol. 8. Karger; Basel: 1990. pp. 148–167. [Google Scholar]

- Ball GF. Neurochemical specializations associated with vocal learning and production in songbirds and budgerigars. Brain Behav Evol. 1994;44:234–246. doi: 10.1159/000113579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ball GF. Neuroendocrine basis of seasonal changes in vocal behavior among songbirds. In: Hauser M, Konishi M, editors. The design of animal communication. MIT Press; Cambridge, MA: 1999. pp. 213–253. [Google Scholar]