Abstract

Objectives. We evaluated the effectiveness of an HIV/STD risk-reduction intervention when implemented by community-based organizations (CBOs).

Methods. In a cluster-randomized controlled trial, 86 CBOs that served African American adolescents aged 13 to 18 years were randomized to implement either an HIV/STD risk-reduction intervention whose efficacy has been demonstrated or a health-promotion control intervention. CBOs agreed to implement 6 intervention groups, a random half of which completed 3-, 6-, and 12-month follow-up assessments. The primary outcome was consistent condom use in the 3 months prior to each follow-up assessment, averaged over the follow-up assessments.

Results. Participants were 1707 adolescents, 863 in HIV/STD-intervention CBOs and 844 in control-intervention CBOs. HIV/STD-intervention participants were more likely to report consistent condom use (odds ratio [OR] = 1.39; 95% confidence interval [CI] = 1.06, 1.84) than were control-intervention participants. HIV/STD-intervention participants also reported a greater proportion of condom-protected intercourse (β = 0.06; 95% CI = 0.00, 0.12) than did the control group.

Conclusions. This is the first large, randomized intervention trial to demonstrate that CBOs can successfully implement an HIV/STD risk-reduction intervention whose efficacy has been established.

The HIV/AIDS pandemic has had a particularly devastating effect on young people throughout the world.1 Those aged 15 to 24 years account for half of all new HIV infections.2 Young people are also at high risk for other STDs. In the United States, although youths aged 15 to 24 years constitute only 25% of the sexually active population, they account for about half of new STD cases.3

Controlled studies have identified developmentally appropriate interventions that reduce self-reported sexual-risk behavior4–10 and rates of biologically confirmed STDs11,12 among adolescents. Less well-documented is whether efficacious HIV/STD interventions retain their ability to reduce sexual risks when implemented under more realistic real-world circumstances.13 This has led to calls for evidence from different types of studies—not studies of the efficacy of HIV/STD risk-reduction interventions under highly controlled circumstances, but studies of their effectiveness in real-world settings.13–15

We conducted a cluster-randomized controlled trial testing the effectiveness of the “Be Proud! Be Responsible!” HIV/STD risk-reduction intervention16 when implemented by community-based organizations (CBOs). Several randomized controlled trials have demonstrated this intervention's efficacy. One reported that African American adolescents who received the intervention reported less sexual-risk behavior at 3-month follow-up than did the control group and that the facilitators' gender did not moderate the intervention's efficacy. 17 Another found that African American adolescents who received the intervention reported less sexual-risk behavior at 6-month follow-up than did the control group and that the intervention's efficacy did not vary by the facilitators' race or gender, the participants' gender, or the gender composition of the intervention groups. 18 A randomized controlled trial found that a culturally adapted version of the intervention reduced sexual risk in Latino adolescents, including monolingual Spanish speakers, at 12-month follow-up.19 Moreover, the intervention was included in the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention dissemination initiative “Programs that Work” and distributed to US schools and CBOs. An economic analysis suggests that the intervention is cost-effective.20

We employed a cluster design with CBOs as the unit of randomization to allow us to draw conclusions about effectiveness of implementation by CBOs. CBOs have played a central role in the fight against HIV since the beginning of the epidemic21–24 and are seen as an essential component of any multisectoral national strategy to curtail the spread of HIV.2 Although previous research has examined factors that increase the likelihood that CBOs will adopt evidence-based HIV risk-reduction strategies,24–26 no large, randomized, controlled trials have tested the effectiveness of evidence-based interventions when implemented by CBOs.

We hypothesized that adolescents in CBOs randomly assigned to implement “Be Proud! Be Responsible!” would be more likely to report consistent condom use than those in CBOs implementing a health-promotion control intervention. A secondary hypothesis was that the intervention's effectiveness would increase with increases in the amount of training the CBOs received, which varied as follows: only the intervention packet; the packet and 2 days of training; or the packet, the training, a practice intervention-implementation session, and 2 days of additional training incorporating videotapes of trainees' practice sessions.

METHODS

We obtained a sample of New Jersey and Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, CBOs by consulting directories of service organizations and an encyclopedia of organizations,27 accessing listings of service organizations on the Internet, and contacting organizations to determine their eligibility. Organizations were eligible to participate if in the prior year they: (1) were nonprofit, (2) delivered services to the community, (3) served at least 50 adolescents aged 13 to 18 years, (4) served an adolescent population that was at least 50% African American, (5) had at least 1 full-time service provider, (6) were willing to be randomized, and (7) agreed to implement 6 intervention groups and cooperate with data collection. We excluded government agencies, religious organizations, schools, hospitals, and organizations that exclusively served special populations (e.g., mentally ill or homeless adolescents). As compensation, the CBOs received an average of $16 572 each for personnel costs, supplies, refreshments, and facilities fees for recruiting and implementing 6 groups and providing space for data collection over an 18-month period.

The study employed a cluster-randomized controlled trial design. We ranked CBOs on size (average rank of number of employees, budget, and adolescents served in the previous year), experience with HIV/STD prevention programs, and facilitators' gender and age, and we stratified on categories created from this ranking. Within each stratum, using variable blocked (4 to 8 in size) computer-generated random number sequences, we randomized CBOs in a 2 × 3 factorial design to the HIV/STD risk-reduction intervention or the health-promotion control intervention and to 1 of the 3 levels of facilitator training (manual only, standard training, and enhanced training). New Jersey and Philadelphia CBOs were randomized separately from each other. One researcher conducted the computer-generated random assignment, and others executed the assignments.

Adolescents aged 13 to 18 years who read, wrote, and spoke English and had written parent or guardian consent in English or Spanish were eligible to participate. For adequate statistical power, it was not necessary to follow all 6 groups each CBO implemented; we randomly selected 3 for follow-up. This article presents findings for that follow-up sample. Facilitators selected by the CBOs recruited adolescents using a common, standardized, scripted recruitment procedure, irrespective of intervention condition and whether the participant would be in the follow-up sample. Facilitators told the adolescents that they might receive an HIV/STD intervention or a health-promotion intervention and that they might or might not be asked to complete follow-up surveys at 3, 6, and 12 months postintervention.

When recruiting, the facilitators were unaware of whether the participants were in the follow-up sample. When participants arrived for their initial intervention session, they were informed of their assigned intervention and were told whether they were in the follow-up sample. Participants signed assent forms. They received $20 for completing each assessment (preintervention, postintervention, 3-month follow-up, 6-month follow-up, and 12-month follow-up).

Intervention Methods

To reduce the likelihood that the effects of the HIV/STD intervention could be attributed to its nonspecific features,28 such as group interaction and special attention, the interventions were structurally similar. Both involved six 50-minute modules of developmentally appropriate interactive activities, films, small-group discussions, experiential exercises, and role-play activities delivered in 2 sessions of 3 modules each.

“Be Proud! Be Responsible!”16 is based on social cognitive theory,29 the theory of reasoned action,30,31 and the theory of planned behavior.32 The intervention is designed to give adolescents the knowledge, motivation, and skills necessary to reduce their risk for STDs, including HIV. It covers information about STDs, including etiology, detection, transmission, prevention, and the possibility of asymptomatic infection. The intervention teaches that abstinence is the most effective way to prevent STDs, but it emphasizes that if adolescents do have sex they should use condoms. It addresses attitudes toward condom use, skill and self-efficacy in using condoms, beliefs about negative consequences of condoms for sexual enjoyment, and skill and self-efficacy in negotiating condom use. It includes themes that encourage adolescents to be proud of themselves, their family, and their community; to behave responsibly for the sake of themselves, their family, and their community; and to consider their goals for the future and how unhealthful behavior might hinder their efforts to achieve those goals. The health-promotion control intervention18,33 focused on reducing behaviors linked to risk for heart disease, hypertension, lung disease, and cancer.

Minimum qualifications for facilitators were a high school diploma; good oral communication skills; small-group experience; experience working with African American adolescents; a background in AIDS education, health education, or skill-building education; and comfort with teaching adolescents about sensitive, potentially embarrassing health topics. Each CBO could hire a new employee or select a current employee with these qualifications.

Facilitators in the manual-only condition received the intervention packet, including the curriculum manual and supporting materials, but no training—only the instruction to prepare by studying the curriculum. Facilitators in the standard-training condition received the intervention packet and a 2-day training similar to a national training-of-trainers for personnel from state departments of education and health and CBOs for use of the “Be Proud! Be Responsible!” curriculum, sponsored by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Facilitators in the enhanced-training condition received the intervention packet and the 2-day standard training, and they practiced implementing the intervention with a group of adolescents. Facilitator trainers were on-site during the practice session, monitored and supervised the implementation, and met with facilitators before and after it to discuss implementation issues. The practice session was videotaped, and the videotapes were used in 2 additional days of training.

Data Collection and Outcome Measures

Participants completed confidential measures of sexual behaviors preintervention and at 3, 6, and 12 months postintervention. Data collectors were blind to the participants' intervention. The reliability and validity of the measures had been established in previous research.5,12,17,18 To increase the validity of self-reports, we used strategies employed in previous intervention trials that found that self-reported sexual behavior and changes in sexual behavior were unrelated to a standard measure of social desirability response bias.5,12,17,18 For instance, to facilitate participants' ability to recall behaviors, we asked them to report their behaviors over a brief period (i.e., the prior 3 months), wrote the dates comprising the period on a chalkboard, and gave them calendars clearly highlighting the period. We stressed the importance of responding honestly, and we told them their responses would be used to create programs for other adolescents like themselves but we could do so only if they responded honestly. We assured participants that their responses would be kept confidential and that code numbers, not names, would be used on the questionnaires.

The primary outcome, self-reported consistent condom use in the previous 3 months, was a binary outcome coded 1 if participants did not use a condom every time they had vaginal intercourse and 2 if they used a condom every time they had vaginal intercourse. Secondary outcomes included a continuous variable for proportion of condom-protected sexual intercourse (number of days on which participants had sexual intercourse using a condom divided by number of days on which they had sexual intercourse); a continuous variable for frequency of condom use rated on a scale from 1 = never to 5 = always; a count variable for frequency of sexual intercourse (number of days on which participants had sexual intercourse) in the prior 3 months; and a binary variable for condom use at most recent sexual intercourse.

Sample Size and Statistical Analyses

We estimated an intraclass correlation of 0.05 on the basis of school-based studies of adolescents' substance use and alcohol consumption.34 We assumed that the 3 groups from each CBO randomly selected for follow-up would include about 20 participants and that 70% of participants (14) would complete the trial. With an α of 0.05, 2-tailed z tests, and an intraclass correlation of 0.05, we projected that 43 CBOs with 14 participants each completing the trial in each intervention condition would provide a power of 92% to detect a 0.25 standard deviation difference in self-reported sexual behavior between the interventions,35 properly accounting for the correlation caused by clustering of participants within CBOs.

We used χ2 and t tests to analyze attrition and descriptive statistics to summarize the participants at baseline for sociodemographic and sexual behavior variables. We tested the effectiveness of the HIV/STD risk-reduction intervention averaged over the postintervention assessments by using a linear, logistic, or Poisson generalized estimating equations regression36 model, depending on the type of outcome variable (continuous, binary, or count, respectively). To account for clustering at the participant and CBO levels, we specified an unstructured working correlation matrix in both the estimation of the model parameters and the robust sandwich estimators of the standard errors of these estimates. The models were fit and contrast statements were specified to obtain estimated mean differences and corresponding 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for continuous measures, odds ratios (ORs) and corresponding 95% CIs for binary measures, and event rate ratios and 95% CIs for counts to compare outcomes across intervention conditions. The models included time-independent covariates, baseline measure of the criterion, intervention condition, time (3 categories representing 3-, 6-, and 12-month follow-up), gender, age group (13–14 years, 15–16 years, and 17–18 years), and race (Black/African American versus others). Models assessing whether the efficacy of the intervention differed among the 3 follow-ups included the baseline measure of the criterion, intervention condition, time, and the intervention condition × time interaction.

In analyses of consistent condom use, proportion of protected intercourse, frequency of condom use, and condom use during most recent intercourse, the sample was limited to participants who were sexually experienced at baseline. Models assessing the effects of the intensity of moderator training included the baseline measure of the criterion, intervention condition, time, 2 intensity-of-training contrast-coded variables (1 representing a linear trend and the other a quadratic trend), the intervention condition × intensity of training linear and quadratic interactions, gender, age group, and race. In tests of intervention effects and intervention condition × intensity of training interactions on condom use, no type I error adjustment was made because these were a priori hypotheses that the trial was designed to test. On frequency of intercourse, the type I error adjusted α was 0.025 (or 0.05/2). The basis for considering race, gender, and age group as moderators was weak; accordingly, a type I error correction reflecting the 3 tests performed was applied (α = 0.0167, or 0.05/3) in tests of these potential moderators. Analyses were performed using an intent-to-treat mode, with participants analyzed on the basis of their intervention assignment regardless of the number of intervention or data-collection sessions attended. All analyses were completed using SAS version 9 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC).

RESULTS

Recruitment and follow-up took place from February 1998 to February 2002. A total of 122 organizations were eligible to participate, and 86 enrolled. The following were among the reasons CBOs cited for declining to participate: 5 (13.9%) were too busy or understaffed, 5 (13.9%) said advocating condom use was against their philosophy, 3 (8.3%) did not want to be randomized to the health-promotion control condition, and 2 (5.6%) said they were implementing another HIV/STD curriculum. Table 1 presents characteristics of the CBOs and participants by intervention condition. The sample includes 22 CBOs from Philadelphia and 64 from New Jersey. All the CBOs were retained through the 12-month follow-up.

TABLE 1.

Sociodemographic Characteristics at Baseline of Participating Community-Based Organizations and Adolescents Randomly Selected for Follow-Up, by Intervention Condition: Philadelphia, PA, and New Jersey, 1998–2002

| Characteristic | HIV/STD Intervention, Mean or No. (%) | Health-Promotion Control Intervention, Mean or No. (%) | Total, Mean or No. (%) |

| Community-based organizations | |||

| No. | 43 | 43 | 86 |

| Employees | 48.3 | 42.0 | 45.1 |

| Adolescent clients in past y | 836.8 | 713.1 | 775.0 |

| Median annual budget (× $100 000) | 12.3 | 6.6 | 7.7 |

| Provided HIV/STD interventions in prior 5 y | 32/43 (74.4) | 33/41 (80.5) | 65/84 (77.4) |

| Intensity of facilitator training | |||

| Manual only | 14/43 (32.6) | 15/43 (34.9) | 29/86 (33.7) |

| Standard training | 14/43 (32.6) | 13/43 (30.2) | 27/86 (31.4) |

| Enhanced training | 15/43 (34.9) | 15/43 (34.9) | 30/86 (34.9) |

| Facilitators | |||

| Age, y | 36.6 | 38.6 | 37.6 |

| Female | 31/43 (72.1) | 32/43 (74.4) | 63/86 (73.3) |

| Black or African American | 34/43 (79.1) | 37/43 (86.0) | 71/86 (82.6) |

| < Bachelor's degree | 16/43 (37.2) | 12/43 (27.9) | 28/86 (32.6) |

| ≥ Bachelor's degree or more | 27/43 (62.8) | 31/43 (72.1) | 58/86 (67.4) |

| Adolescents selected for follow-up | |||

| No. | 863 | 844 | 1707 |

| Female | 500/863 (57.9) | 460/844 (54.5) | 960/1707 (56.2) |

| Black or African Americana | 740/842 (87.9) | 766/833 (92.0) | 1506/1675 (89.9) |

| Age, y | |||

| 13–14 | 422/863 (48.9) | 384/844 (45.5) | 806/1707 (47.2) |

| 15–16 | 303/863 (35.1) | 310/844 (36.7) | 613/1707 (35.9) |

| 17–18 | 138/863 (16.0) | 150/844 (17.8) | 288/1707 (16.9) |

| Sexually experienceda | 488/850 (57.4) | 450/834 (54.0) | 938/1684 (55.7) |

Denominators are smaller than the sample size because not all participants answered the questions regarding their race or sexual experience.

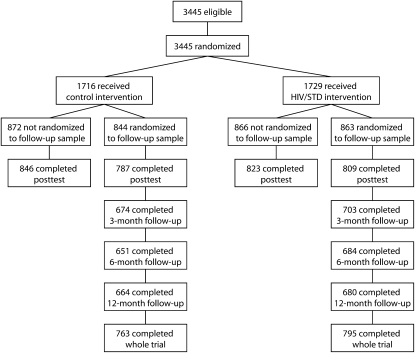

Figure 1 shows the flow of participants in the study. A total of 3445 adolescents received the interventions, and 1707 (863 in the HIV/STD-intervention CBOs and 844 in the control-intervention CBOs) were included in the intervention groups randomly selected for the follow-up sample. The mean age of the follow-up sample was 14.8 years (SE = 0.4). About 95.4% of participants attended both sessions of their assigned intervention, and 1558 (91.3%) of participants attended at least 1 follow-up: 1377 (80.7%), 1335 (78.2%), and 1344 (78.7%) attended the 3-, 6-, and 12-month follow-up sessions, respectively. The 2 interventions did not differ significantly in the percentage of adolescents who attended the follow-up sessions (P = .21). A greater percentage of Black (92.0%) adolescents returned for follow-up compared with other adolescents (87.7%; P = .02). Adolescents aged 17 to 18 years (84.4%) were less likely to return than those aged 15 to 16 years (90.9%) or 13 to 14 years (94.0%; P < .001). Those who returned reported a lower proportion of condom-protected intercourse at baseline (mean = 0.67) than did those who did not return (mean = 0.81; P = .007).

FIGURE 1.

Progress of adolescent participants through the study: Philadelphia, PA, and New Jersey, 1998–2002.

Table 2 presents the descriptive statistics for outcomes by intervention condition and time. Table 3 presents significance tests for the intervention effect over the follow-up period. A significantly greater percentage of the participants in the CBOs that implemented “Be Proud! Be Responsible!” reported consistent condom use averaged over the 3 follow-up assessments, compared with their counterparts in the CBOs that implemented the heath-promotion control intervention, controlling for baseline, gender, age group, and race. Averaged over the follow-ups, participants in the HIV/STD intervention reported a greater proportion of condom-protected intercourse acts during the follow-up period than did health-promotion intervention participants. In addition, averaged over the follow-ups, the HIV/STD intervention participants reported using condoms more frequently when they had intercourse and were more likely to report using a condom during their most recent intercourse episode compared with those in the health-promotion control intervention. We observed no significant differences between the interventions in frequency of intercourse. None of the intervention condition × time interactions were significant, which means the effectiveness of the intervention did not vary among the 3 follow-up assessment periods.

TABLE 2.

Adolescents' Self-Reported Sexual Behaviors by Intervention Condition and Time: Philadelphia, PA, and New Jersey, 1998–2002

| Variable | Baseline, No. (%) or Mean (SE) | 3-Month Follow-Up, No. (%) or Mean (SE) | 6-Month Follow-Up, No. (%) or Mean (SE) | 12-Month Follow-Up, No. (%) or Mean (SE) |

| Consistently used condoms in prior 90 days | ||||

| Health-promotion control intervention | 205/340 (60.3) | 137/260 (52.7) | 114/227 (50.2) | 126/252 (50.0) |

| HIV/STD intervention | 210/369 (56.9) | 168/288 (58.3) | 152/286 (53.1) | 156/278 (56.1) |

| Proportion of condom-protected sexual intercourse in prior 90 d | ||||

| Health-promotion control intervention | 0.76 (0.02) | 0.69 (0.02) | 0.75 (0.04) | 0.69 (0.03) |

| HIV/STD intervention | 0.72 (0.02) | 0.76 (0.02) | 0.79 (0.04) | 0.73 (0.02) |

| Frequency of condom use in prior 90 d | ||||

| Health-promotion control intervention | 3.92 (0.08) | 3.66 (0.09) | 3.59 (0.10) | 3.57 (0.10) |

| HIV/STD intervention | 3.81 (0.08) | 3.85 (0.08) | 3.76 (0.08) | 3.60 (0.08) |

| Used condom at last sexual intercourse | ||||

| Health-promotion control intervention | 330/446 (74.0) | 225/331 (68.0) | 218/301 (72.4) | 224/316 (70.9) |

| HIV/STD intervention | 340/484 (70.2) | 262/363 (72.2) | 249/334 (74.6) | 250/348 (71.8) |

| Frequency of sexual intercourse in prior 90 d | ||||

| Health-promotion control intervention | 3.15 (0.34) | 2.96 (0.31) | 2.64 (0.26) | 4.25 (0.41) |

| HIV/STD intervention | 2.78 (0.26) | 2.62 (0.25) | 3.15 (0.31) | 3.68 (0.34) |

Note. Frequency of condom use was rated on a scale from 1 = never to 5 = always. Frequency of sexual intercourse is the number of days on which the participant reported having sexual intercourse.

TABLE 3.

GEE Model-Based Significance Tests and Effect-Size Estimates for Intervention Effect on Adolescents' Self-Reported Sexual Behavior Over a 12-Month Follow-Up Period: Philadelphia, PA, and New Jersey, 1998–2002

| Outcome | Estimate | P |

| Consistent condom use in prior 3 mo,a OR (95% CI) | 1.39 (1.06, 1.84) | .02 |

| Proportion of protected sexual intercourse, % (95% CI) | 0.06 (0.00, 0.12) | .04 |

| Rated frequency of condom use,b mean difference (95% CI) | 0.20 (0.02, 0.39) | .03 |

| Condom use at last sexual intercourse,a OR (95% CI) | 1.29 (1.00, 1.67) | .05 |

| Frequency of sexual intercourse, event rate ratio (95% CI) | 1.06 (0.88, 1.28) | .56 |

Note. CI = confidence interval; GEE = generalized estimating equation.

OR for intervention versus health control.

Frequency of condom use was rated on a scale from 1 = never to 5 = always.

There were no significant intervention condition × intensity of training linear interactions (P > .09), which means the effectiveness of the intervention did not significantly increase with more intensive facilitator training. Nor were there significant interactions between the intervention and participants' gender (P > .11) or race (P > .21). However, the intervention × age group interaction was significant (P = .003). The intervention increased consistent condom use significantly more in older adolescents, those aged 17 to 18 years (OR = 2.45; 95% CI = 1.40, 4.26; P = .002), than in those aged 13 to 14 years (OR = 0.76; 95% CI = 0.47, 1.23; P = .27), with those aged 15 to 16 years falling in the middle (OR = 1.00; 95% CI = 0.68, 1.48; P = .99). The interactions on the other behavioral outcomes did not reach the type I error adjusted significance criterion (P > .0167).

DISCUSSION

This study suggests that CBOs can achieve success when implementing an evidence-based HIV/STD risk-reduction intervention with adolescents. Consistent with the findings of efficacy trials,17–19 adolescents in the CBOs that implemented “Be Proud! Be Responsible!” were more likely to report using condoms consistently (averaged over the 3-, 6-, and 12-month follow-up assessments) than were those in the CBOs that implemented the health-promotion control intervention. The study also revealed significant effects on other indicators of condom use: proportion of condom-protected sexual intercourse, rated frequency of condom use, and condom use at most recent sexual intercourse. Moreover, the intervention's effectiveness in increasing condom use did not vary among the 3 follow-up assessments.

Interestingly, the intervention did not reduce frequency of sexual intercourse. This contrasts with a randomized controlled trial that found that the intervention reduced frequency of sexual intercourse among African American adolescents similar in age to our participants.17 The lack of an intervention effect on sexual intercourse here may be because of selection bias among CBOs enrolled in this trial. A commonly cited reason for declining to participate was the CBO's philosophy that only abstinence should be promoted as a way to reduce HIV/STD risk. If more CBOs that strongly supported abstinence had been included in the trial, perhaps the intervention would have influenced sexual intercourse.

We systematically varied the amount of training the CBO facilitators received, but we found no evidence that greater amounts of training translated into greater intervention effects. This suggests that it is not necessary to give CBO facilitators more training than is provided to facilitators in efficacy trials or in train-the-trainer workshops. However, the optimal amount of training might depend on the quality of the intervention materials. The “Be Proud! Be Responsible!” manual contained background material and explanations of proper implementation that may have been sufficient for CBO facilitators, obviating the need for additional training. Although previous research has shown that enhanced training increases the adoption rate of evidence-based HIV risk-reduction interventions,25 this is the first study to examine the effects of enhanced training on the effectiveness of an intervention implemented by CBOs.

This study has several important methodological strengths. CBOs were randomly assigned to intervention and training conditions; a large number of CBOs were employed; the CBOs, not the researchers, selected the facilitators and recruited participants from their usual populations; and facilitators received levels of training they would normally receive. These design features increase the generalizability of our findings. Participants were blind to the intervention condition before enrollment, reducing the likelihood of differential self-selection bias. A health-promotion attention-control intervention that controlled for the amount of exposure to the intervention the participants received was employed, no CBOs withdrew from the study, and intervention attendance rates were excellent, strengthening internal validity. The data analysis properly adjusted for clustering of participants within CBOs assessed longitudinally.

However, this study also has limitations. It focused on CBOs that served African American adolescents; whether similar results would be obtained in other adolescent populations is unknown. The primary outcome, consistent condom use, was measured with self-reports. Although several studies, including prospective studies of HIV-serodiscordant couples, suggest that self-reports of consistent condom use are valid,37–40 the fact that sexual behavior was self-reported is a limitation.

In conclusion, this study provides the first evidence from a large, randomized, controlled trial that CBOs can achieve reductions in sexual-risk behavior when implementing an intervention with demonstrated efficacy. Moreover, it suggests that the training of CBO facilitators need not be extraordinarily extensive or expensive to achieve the desired results. What makes these findings exciting is that CBOs have played such a critical role in the delivery of HIV-prevention services throughout the world.2 Future research should explore the effectiveness of CBOs with other populations of adolescents. Such research should also focus on strategies to equip CBOs to encourage abstinence, which may be contextually appropriate for certain populations. Nevertheless, the present study suggests that efficacious interventions retain their beneficial effects when implemented by CBOs outside of tightly controlled research settings.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by the National Institute of Mental Health (grant R01 MH55442).

The authors gratefully acknowledge the contributions to this research of Konstance McCaffree, PhD, Stephanie Bray, BA, Gladys Thomas, MBA, MSW, Janet Hsu, BA, Paulette Moore Hines, PhD, and M. Isabel Fernandez, PhD. We thank Thomas Ten Have, PhD, for his statistical advice and comments on a draft of this article.

Human Participant Protection

This research was approved by the institutional review board of the University of Pennsylvania. All participants had written parent or guardian informed consent and provided written assent to participate.

References

- 1.Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS AIDS Epidemic Update: 2003 Geneva, Switzerland: Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS and World Health Organization; 2003 [Google Scholar]

- 2.Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS 2004 Report on the Global AIDS Epidemic Geneva, Switzerland: Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS and World Health Organization; 2004 [Google Scholar]

- 3.Weinstock H, Berman S, Cates W., Jr Sexually transmitted diseases among American youth: incidence and prevalence estimates, 2000. Perspect Sex Reprod Health 2004;36(1):6–10 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Coyle K, Basen-Engquist K, Kirby D, et al. Safer choices: reducing teen pregnancy, HIV, and STDs. Public Health Rep 2001;116(suppl 1):82–93 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jemmott JB, III, Jemmott LS, Fong GT. Abstinence and safer sex HIV risk-reduction interventions for African American adolescents: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA 1998;279(19):1529–1536 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.St. Lawrence JS, Brasfield T, Jefferson K, Alleyne E, O'Bannon RA, III, Shirley A. Cognitive behavioral intervention to reduce African American adolescents' risk for HIV infection. J Consult Clin Psychol 1995;63(2):221–237 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Stanton BF, Li X, Ricardo I, Galbraith J, Feigelman S, Kaljee L. A randomized, controlled effectiveness trial of an AIDS prevention program for low-income African American youths. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med 1996;150(4):363–372 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jemmott JB, III, Jemmott LS. HIV risk reduction behavioral interventions with heterosexual adolescents. AIDS 2000;14(suppl 2):S40–S52 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Johnson BT, Carey MP, Marsh KL, Levin KD, Scott-Sheldon LA. Interventions to reduce sexual risk for the human immunodeficiency virus in adolescents, 1985–2000: a research synthesis. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med 2003;157(4):381–388 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mullen PD, Ramirez G, Strouse D, Hedges LV, Sogolow E. Meta-analysis of the effects of behavioral HIV prevention interventions on the sexual risk behavior of sexually experienced adolescents in controlled studies in the United States. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2002;30(suppl 1):S94–S105 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.DiClemente RJ, Wingood GM, Harrington KF, et al. Efficacy of an HIV prevention intervention for African American adolescent girls: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA 2004;292(2):171–179 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jemmott JB, III, Jemmott LS, Braverman PK, Fong GT. HIV/STD risk reduction interventions for African American and Latino adolescent girls at an adolescent medicine clinic: a randomized controlled trial. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med 2005;159(5):440–449 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Interventions to Prevent HIV Risk Behaviors Washington, DC: National Institutes of Health; 1997 [Google Scholar]

- 14.Elford J, Hart G. If HIV prevention works, why are rates of high-risk sexual behavior increasing among MSM? AIDS Educ Prev 2003;15(4):294–308 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Flay BR. Efficacy and effectiveness trials (and other phases of research) in the development of health promotion programs. Prev Med 1986;15(5):451–474 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jemmott LS, Jemmott JB, III, McCaffree K. Be Proud! Be Responsible! Strategies to Empower Youth to Reduce Their Risk for AIDS New York, NY: Select Media Publications; 1995 [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jemmott JB, III, Jemmott LS, Fong GT. Reductions in HIV risk-associated sexual behaviors among Black male adolescents: effects of an AIDS prevention intervention. Am J Public Health 1992;82(3):372–377 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jemmott JB, III, Jemmott LS, Fong GT, McCaffree K. Reducing HIV risk-associated sexual behavior among African American adolescents: testing the generality of intervention effects. Am J Community Psychol 1999;27(2):161–187 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Villarruel AM, Jemmott JB, III, Jemmott LS. A randomized controlled trial testing an HIV prevention intervention for Latino youth. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med 2006;160(8):772–777 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pinkerton SD, Holtgrave DR, Jemmott JB., III Economic evaluation of an HIV risk reduction intervention for male African American adolescents. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2000;25(2):164–172 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chillag K, Bartholow K, Cordeiro J, et al. Factors affecting the delivery of HIV/AIDS prevention programs by community-based organizations. AIDS Educ Prev 2002;14(3 suppl):27–37 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Crane SF, Carswell JW. A review and assessment of non-governmental organization-based STD/AIDS education and prevention projects for marginalized groups. Health Educ Res 1992;7(2):175–194 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Paiva V, Ayres JR, Buchalla CM, Hearst N. Building partnerships to respond to HIV/AIDS: non-governmental organizations and universities. AIDS 2002;16(suppl 3):S76–S82 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Miller RL. Innovation in HIV prevention: organizational and intervention characteristics affecting program adoption. Am J Community Psychol 2001;29(4):621–647 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kelly JA, Somlai AM, DiFranceisco MS, et al. Bridging the gap between the science and service of HIV prevention: transferring effective research-based HIV prevention interventions to community AIDS service providers. Am J Public Health 2000;90(7):1082–1088 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kelly JA, Somlai AM, Benotsch EG, et al. Distance communication transfer of HIV prevention interventions to service providers. Science 2004;305(5692):1953–1955 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lagasse P. Encyclopedia of Associations, Regional, State and Local Organizations New York, NY: Columbia University Press; 2001 [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cook TD, Campbell DT. Quasi-experimentation: Design and Analysis Issues for Field Settings Chicago, IL: Rand McNally; 1979 [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bandura A. Social Foundations of Thought and Action: A Social Cognitive Theory Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall; 1986 [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ajzen I, Fishbein M. Understanding Attitudes and Predicting Social Behavior Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall; 1980 [Google Scholar]

- 31.Fishbein M, Ajzen I. Belief, Attitude, Intention and Behavior Reading, MA: Addison-Wesley; 1975 [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ajzen I. The theory of planned behavior. Organ Behav Hum Decis Process 1991;50(2):179–211 [Google Scholar]

- 33.Jemmott JB, III, Jemmott LS, Spears H, Hewitt N, Cruz-Collins M. Self-efficacy, hedonistic expectancies, and condom-use intentions among inner-city Black adolescent women: a social cognitive approach to AIDS risk behavior. J Adolesc Health 1992;13(6):512–519 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Murray DM, Hannan PJ. Planning for the appropriate analysis in school-based drug-use prevention studies. J Consult Clin Psychol 1990;58(4):458–468 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kalichman SC, Carey MP, Johnson BT. Prevention of sexually transmitted HIV infection: a meta-analytic review of the behavioral outcome literature. Ann Behav Med 1996;18(1):6–15 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Diggle PJ, Liang KY, Zeger SL. Analysis of Longitudinal Data New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 1994 [Google Scholar]

- 37.Warner L, Newman DR, Austin HD, et al. Condom effectiveness for reducing transmission of gonorrhea and chlamydia: the importance of assessing partner infection status. Am J Epidemiol 2004;159(3):242–251 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.De Vincenzi I. A longitudinal study of human immunodeficiency virus transmission by heterosexual partners. N Engl J Med 1994;331(6):341–346 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Saracco A, Musicco M, Nicolosi A, et al. Man-to-woman sexual transmission of HIV: longitudinal study of 343 steady partners of infected men. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 1993;6(5):497–502 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Davis KR, Weller SC. The effectiveness of condoms in reducing heterosexual transmission of HIV. Fam Plann Perspect 1999;31(6):272–279 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]