Abstract

Objectives. We present a social marketing conceptual framework for Experience Corps Baltimore City (EC) in which the desired health outcome is not the promoted product or behavior. We also demonstrate the feasibility of a social marketing–based recruitment campaign for the first year of the Baltimore Experience Corps Trial (BECT), a randomized, controlled trial of the health benefits of EC participation for older adults.

Methods. We recruited older adults from the Baltimore, MD, area. Participants randomized to the intervention were placed in public schools in volunteer roles designed to increase healthy behaviors. We examined the effectiveness of a recruitment message that appealed to generativity (i.e., to make a difference for the next generation), rather than potential health benefits.

Results. Among the 155 participants recruited in the first year of the BECT, the average age was 69 years; 87% were women and 85% were African American. Participants reported primarily generative motives as their reason for interest in the BECT.

Conclusions. Public health interventions embedded in civic engagement have the potential to engage older adults who might not respond to a direct appeal to improve their health.

All that's required on your part is a willingness to make a difference. That is, after all, the beauty of service. Anyone can do it.

President Barack Obama, upon signing the Edward M. Kennedy Serve America Act, April 21, 20091

Social marketing uses marketing principles to promote interventions that enhance a social good. Social marketing–based public health interventions could be particularly useful in addressing health behaviors such as physical inactivity, where health education alone may not be effective.2 Social marketing differs from traditional health education in that the health promotion outcome may not be identical to the product or behavior being promoted.3 An example of this is the VERB campaign, which increased free-time physical activity among children aged 9 to 13 years by marketing “fun” and “cool” activities, rather than focusing primarily on health benefits or health risks.4 Similarly, in Baltimore, Maryland, Experience Corps Baltimore City (EC) was designed to increase physical, cognitive, and social activity among seniors through specially designed volunteer roles in public elementary schools.5,6

In 2006, the National Institute on Aging funded the Baltimore Experience Corps Trial (BECT), a randomized controlled trial designed to determine the model's potential to compress the morbidity associated with aging.7 In addition to the primary outcomes of mobility-associated disability, the BECT analyzes the effect of the model on self-reported falls, self-efficacy, memory, health expenditures, and physical activity. The recruitment for the BECT represents a model for future social marketing interventions that could promote health through an appeal to the participation of older adults in national and community service.

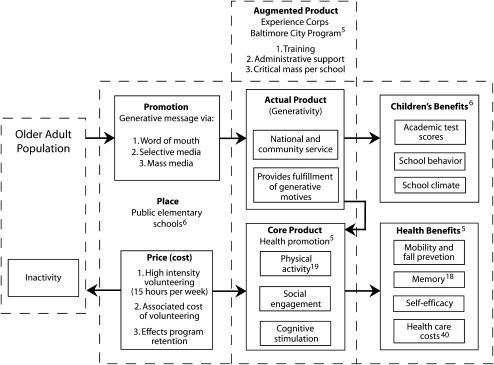

EC has been described in medical literature as a social model for health promotion that describes the “win-win” potential of the program from society's perspective.5 It has yet to be described within the theoretical framework of social marketing, which takes the perspective of the potential volunteer (Figure 1). However, EC, as originally designed,5 is remarkably consistent with social marketing principles. The “4 P's” of social marketing are product, price, place, and promotion.8,9 Product is the desired behavior, or the goods or services that support the desired behavior change. For EC, the product is increased physical, cognitive, and social activity. Price reflects the cost or barriers to adopting the product and must include a consideration of the competing products or behaviors, which for EC would be inactivity. Place represents the location where the target audience will perform the desired behavior; in EC, older adults volunteer in public schools. Promotion reflects the messages and strategies used to reach the audience. In EC, we theorized that older adults would be attracted by generative motives (i.e., desire to make a difference for the next generation). The 4 P's of social marketing provide a conceptual framework for future interventions modeled after EC.

FIGURE 1.

Social marketing conceptual framework for Experience Corps Baltimore City, Maryland.

The development and implementation of the first year of recruitment for the BECT demonstrate how this social marketing conceptual framework could serve as a template for future public health interventions. Using the 4 P's of social marketing, we describe the design of a promotion campaign that appeals to generative motives in older adults. Prior recruitment for a previously published pilot trial was limited to word of mouth, community outreach, and limited direct mailing.5,10 We present promotion campaign results and mass marketing data from the first year of recruitment for the BECT (2006 through 2007 school year). We also demonstrate the feasibility of recruiting older adults through a social marketing campaign using multiple strategies. Finally, we demonstrate how social marketing could be used to guide (1) the development of volunteer programs designed to serve as public health interventions and (2) future research.

METHODS

Our recruitment goals for the BECT are to randomize 700 older adults over 4 years. Study participants randomized to the intervention arm receive 30 hours of training and are placed in participating Baltimore City public schools, whereas control arm participants are placed on a waiting list for EC that includes low-intensity volunteer alternatives. We began recruitment planning for the BECT in June 2006, with funding beginning in November 2006 and recruitment for the 2006–2007 school year ending in February 2007. Recruitment staff for the first year consisted of a full-time recruitment coordinator and a full-time recruiter, with additional effort provided by study investigators.

Product

Kotler and Lee divided product strategy into 3 components: the core product is the desired benefit from the public health perspective; the actual product is the desired product or behavior from the potential customer or participant's perspective; and the augmented product is the tangible objects and services that support the behavioral change.7 In EC, the core product is increased physical, social, and cognitive activity, whereas the actual product provides older adults an opportunity to give back to the community. EC, which is the augmented product, was designed as both a health promotion intervention and a program to improve academic outcomes among children5,6 (Figure 1).

Core product.

Although there is evidence supporting the health benefits of physical activity for all ages,11–15 the direct promotion of physical activity has had limited effectiveness. For example, the US Preventive Services Task Force has concluded that there is insufficient evidence to recommend counseling adult patients to promote physical activity in primary care settings.2 The designers of EC theorized that a minimum of 15 hours of volunteering a week would promote a significant amount of physical activity through travel to and from, as well as activity within, a school.5 In 1999 and 2000, a 1-year pilot randomized controlled trial conducted in Baltimore City provided the initial evidence that EC could increase physical, as well as social and cognitive, activity.5,16–18 There is additional evidence of the long-term benefit of participation in EC, as African American women in EC reported sustained increases in physical activity compared with matched controls over a 3-year period.19 However, in social marketing theory, the core product is not what is actually marketed, and the importance of physical, social, or cognitive activity was not used as a recruitment message in the BECT.

Actual product.

The actual product that is marketed through EC is generative fulfillment. Generativity has been described by Erikson as a developmental stage that begins in middle age and is characterized by the desire to leave a legacy and contribute to the next generation.20 In the pilot trial, 64% volunteered “to help children.”5 This generative message may be particularly attractive to “natural helpers”—community individuals to whom people naturally turn for advice or assistance.21

Augmented product.

EC represents a high-intensity model of older adult volunteering that was specifically designed to promote physical activity (as well as cognitive and social activity) and to improve academic and behavioral outcomes among the schoolchildren.5 Social marketing can work in concert with community development to create sustained behavioral change.9 To help sustain this high level of volunteer commitment, the augmented product supports the volunteers in a number of ways. All volunteers complete a 30-hour training program, are placed in a school with a critical mass of 20 older adults to provide social support, and are managed primarily by the program to minimize the school's administrative burden.5,22 The augmented product, which has been described as a social model for health promotion, was designed to have a community-level effect.5,22 In this regard, EC operates very much like an “informal helper intervention,” by recruiting volunteers, creating opportunities for neighbors to interact, and linking “natural helpers” to formal volunteering.21 Although volunteering is associated with improved health outcomes in many observational studies,23–27 the increased physical activity observed in EC5,17,19 may not extend to other volunteer programs.

Price

Within the proposed conceptual framework, price represents the cost of replacing a sedentary or inactive lifestyle with high-intensity volunteering.8 Two previous national demonstrations of Experience Corps (outside Baltimore City) determined that an incentive stipend was essential for the recruitment and retention of volunteers in a high-intensity program.5,28 BECT participants in the intervention arm receive a monthly stipend that helps to reimburse the costs incurred through participation. Although the stipend was conditioned on 15 hours a week of volunteer time, older adults in the pilot trial provided an average of 22 hours a week, despite lack of additional reimbursement5 (Figure 1). The recruitment material mentions that those who volunteer in the schools will receive a small stipend, but we minimized the stipend in our recruitment message as we sought to recruit older adults with generative, rather than economic, motives.

Participation in the BECT adds an additional “cost”: participants must agree to be randomly assigned to either EC or to the control arm. We compensated all participants with $25 for each in-person evaluation and a $10 dollar gift card for each over-the-phone interview.

Place

Place represents where the target behavior is performed.8 In the BECT, recruitment materials include images of older adults in school settings. Volunteers in EC perform needed roles in urban public elementary schools, which are typically underfunded and overextended; recruiters would reference preliminary data from previous studies that demonstrated the potential for improved reading outcomes among children in schools participating with EC6 (Figure 1). Volunteer roles in EC were purposefully designed to be valued by school principals and feasible and attractive to older adults with a wide variety of educational levels. The roles are particularly suited for “natural helpers” from the community: supporting general literacy and math skills, library and computer laboratory use, and violence prevention through a conflict resolution intervention.5,6,16,22 African Americans who volunteer are more likely to engage in youth mentoring.29 EC has demonstrated the ability to attract older African Americans.5,19 Programs modeled on EC have the potential to attract older minority adults who are underrepresented in traditional public health interventions and are at higher risk for poor health outcomes.30–32

Promotion

Promotion reflects the messages and recruitment strategies used to reach the intended audience. In BECT, the recruitment messages reflected the actual product of older adult generative activity. We chose “Share your wisdom” and “Do you want to make a difference?” as the main recruitment messages. When possible, we included images of older adults engaged in intergenerational activities in school settings, as an example of “social proof” or evidence of similar older adults engaging in volunteer activity in public schools.33 Recruitment material stated that the purpose of randomization was to enable the BECT to determine the health benefits of volunteering. However, the potential health benefits of the program were not used as a recruitment message.

Recruitment strategies included “personal media channels” such as word-of-mouth recruitment through the social networks, as people are more likely to say yes to a request from someone they know and like.33 We also used “selective media channels” such as church bulletins, community outreach talks (during which we handed out brochures and left posters), and direct mailings through formal social networks such as the American Association of Retired Persons (AARP) and the Baltimore City Employees Retirement Systems. Emergent “natural helpers” were identified and served as recruitment ambassadors by speaking about the importance of the trial at community outreach talks.21 Finally, we instituted a mass media campaign that included radio advertisements on local gospel radio, along with press releases that led to public interest articles in both newspapers and local TV.8 Although it was impossible to control for the message provided word of mouth, this primarily generative message was reinforced by recruiters. We included the secondary messages of studying the benefits of volunteering and the concept of randomization as early as possible in the recruitment process.

Recruitment materials publicized a recruitment phone number that prospective participants could call to initiate a 5-step recruitment process, which has been previously described.10 The first step entailed screening potential volunteers in a telephone interview. Recruitment data collected at this step included initial contact information and demographic data, along with health status and information regarding how a prospective participant received information about the trial and what interested the participant about volunteering. Participants were allowed to list more than 1 source of information and reason for participating. Interested participants were invited to the second step, an in-person information meeting. Those who remained interested in participating in the BECT were then invited to join the trial and were scheduled for a baseline evaluation, the third step, where eligibility was established. Eligibility requirements for the BECT included being aged 60 years or older, a Mini-Mental Status Exam score of 24 or above,34 and a minimum sixth-grade reading level.35 Additional data were collected at the baseline evaluation, including self-reported income, comorbid conditions, mobility-associated disability, and physical activity.36 Eligible individuals were randomized after the baseline assessment. The recruitment and evaluation staff described randomization during the telephone screening, at the in-person information meeting, and again prior to consent. Those randomly assigned to the intervention received a background check (fourth step) prior to training (fifth step).

Analyses

We analyzed the baseline characteristics of 368 individuals who responded in the first year of recruitment and were eligible for the BECT, and of 155 who were randomly assigned to the intervention arm or control arm, stratifying by recruitment strategy. Analyses were done using SAS version 9.2 (SAS Institute Inc, Cary, NC). We explored whether individuals who were recruited differed by recruitment strategy or by reason for interest in participation from those declining to participate in the study, using independent t tests for continuous variables and the χ2 test for categorical variables. We categorized the reasons for participating into the following motives: altruism, ideology, material reward, status, social relationships, leisure activity, and personal growth.37

Separate stratified analyses were done among those who reported only 1 recruitment strategy and those who reported more than 1. A series of independent t tests (continuous variables) or χ2 tests (dichotomous variables) were used to examine differences between recruited participants and those who declined participation, according to how they were recruited (recruitment strategy) and the number of recruitment strategies reported.

RESULTS

A total of 469 potential participants were screened in the first year of recruitment. Of these, 368 were eligible by age and able to volunteer 15 hours a week. A total of 155 were recruited successfully, with 213 either declining to proceed with randomization or ineligible for participation at the baseline evaluation. Of those recruited, the average age was 69 years, 85% were women, 87% were African American, and 43% had more than a high school education. There were no significant differences between recruited participants and those who were screened but not recruited into the trial (Table 1). Recruited participants self-reported an average of 4000 kcal of activity a week, or 48 kcal/kg of body weight per week, which is comparable to prior reports of older African American adults.38 Additional baseline characteristics are provided in Table 2.

TABLE 1.

Characteristics of Potential Participants in the First Year of the Baltimore Experience Corps Trial: Baltimore, MD, 2006–2007 School Year

| Screened and Eligible (n = 368), Mean or No. (%) | Not Recruited (n = 213), Mean or No. (%) | Recruited (n = 155), Mean or No. (%) | Pa | |

| Mean age, y | 68.9b | 68.8b | 69.1c | .41 |

| Women | 316 (86) | 185 (87) | 131 (85) | .45 |

| Race | .66 | |||

| African American | 318 (88) | 184 (88) | 134 (87) | |

| White | 37 (10) | 22 (11) | 15 (10) | |

| Other | 8 (2) | 3 (1) | 5 (3) | |

| Education | ||||

| Mean highest grade | 13.5 | 13.5 | 13.7 | .93 |

| ≤ High school | 140 (55) | 70 (53) | 70 (57) | .49 |

| Marital status | .13 | |||

| Married | 92 (26) | 54 (26) | 38 (25) | |

| Divorced | 95 (26) | 56 (27) | 39 (26) | |

| Separated | 8 (2) | 1 (0.5) | 7 (5) | |

| Never married | 36 (10) | 21 (10) | 15 (10) | |

| Widowed | 128 (36) | 77 (37) | 51 (34) | |

| Health status | .40 | |||

| Excellent | 43 (12) | 26 (12) | 17 (11) | |

| Very good | 119 (32) | 64 (30) | 55 (35) | |

| Good | 152 (41) | 89 (42) | 63 (41) | |

| Fair | 51 (14) | 33 (15) | 18 (12) | |

| Poor | 2 (0.5) | 0 (0) | 2 (1) | |

Between recruited and not recruited participants.

Age range was 60–93 years.

Age range was 60–83 years.

TABLE 2.

Baseline Self-Reported Income, Comorbid Conditions, Functional Status, and Physical Activity of Recruited Participants in the First Year of the Baltimore Experience Corps Trial: Baltimore, MD, 2006–2007 School Year

| No. (%) or Mean (SD) | |

| Income, $ | |

| < 10 000 | 26 (17) |

| 10 000–14 999 | 22 (15) |

| 15 000–24 999 | 32 (21) |

| 25 000–34 999 | 24 (16) |

| 35 000–49 999 | 25 (17) |

| ≥ 50 000 | 21 (14) |

| Missing | 5 (3) |

| Comorbid condition | |

| Hypertension | 112 (72) |

| Osteoarthritis | 95 (61) |

| Pulmonary disease | 4 (3) |

| Heart attack or myocardial infarction | 12 (8) |

| Congestive heart failure | 10 (6) |

| Diabetes | 54 (35) |

| Cancer | 12 (8) |

| Difficulty walking several blocks | 30 (20) |

| Difficulty climbing 10 steps | 24 (16) |

| Mean Mini-Mental Status Exam scorea | 28 (1.7) |

| Mean physical activity, kcal/kg/wk | 37.4 (2.1) |

Note. Total number of recruited participants was 155.

Participants were required to score 24 or higher on this exam to be eligible for recruitment.

Source of recruitment information was available for 145 of the 155 recruited participants. Word of mouth was the most common recruitment source among those who were recruited to the BECT from any source, with 31% (n = 45) reporting learning about the trial through friends or family. Selective media strategies produced the majority of recruited participants; these included direct mailings through AARP and the Baltimore City Civil Service Retirees Association (19%), brochures (16%), outreach talks (12%), and notices in church bulletins (13%). Mass media was successful as well; 25% of recruited participants reported hearing about the trial through paid radio advertisements (Table 3).

TABLE 3.

Sources of Recruitment Information as Reported by Recruited Participants in the First Year of the Baltimore Experience Corps Trial: Baltimore, MD, 2006–2007 School Year

| No. of Participants | No. of Participants Reporting 1 Source | No. of Participants Reporting ≥ 2 Sourcesa | Pb | |

| Word of mouth | 45 | 20 | 25 | .46 |

| Direct mailing (letters) | 28 | 23 | 5 | .001 |

| Community outreach talks | 17 | 11 | 6 | .23 |

| Printed material | ||||

| Brochure | 23 | 5 | 18 | .007 |

| Poster | 1 | 0 | 1 | … |

| Church bulletin | 19 | 12 | 7 | .25 |

| Radio advertisement | 36 | 25 | 11 | .02 |

| Newspaper articles | 12 | 5 | 7 | .56 |

| Public interest articles on TV | 7 | 0 | 7 | … |

| Other | 13 | 5 | 8 | .41 |

| Total | 145 | 106 | 39 | <.001 |

| Unknownc | 10 | … | … | … |

Individuals could report more than 1 recruitment source.

One recruitment source versus 2 or more sources.

Ten of the 155 participants did not respond to marketing strategy questions.

Among recruited participants, 73% reported only 1 source of recruitment information and 27% reported 2 or more sources. Among those who learned about the trial through word-of-mouth sources, 44% reported word of mouth as their only source and 56% reported hearing about the BECT through word of mouth and at least 1 other source. The radio ads yielded the largest number of participants who reported only 1 source of recruitment information; these ads were the second most successful recruitment strategy overall (Table 3).

Of the 368 screened, 310 provided information on why they were interested, including 134 of the 155 who were eventually recruited. When we compared the 58 who did not report any motives and the 310 who did provide motives, there were no significant differences in terms of age, education, randomization assignment, health status, or marital status; however, those who did not report a motive were more likely to be White (P ≤ .01). Among study participants who were successfully randomized, 63% reported altruistic motives such as “giving back to the community” or “helping others is important” and 71% reported ideological motives such as “worthwhile cause” or “civil rights/helping the underserved.” Thirty one percent of recruited participants reported material rewards such as it is “good for me” (Table 4).

TABLE 4.

Examples of Participant Motives for Participating in the First Year of the Baltimore Experience Corps Trial: Baltimore, MD, 2006–2007 School Year

| Motives37 and Examples | Screened and Eligible Participants, No. or No (%) | Participants Not Recruited, No. or No (%) | Participants Recruited, No. or No (%) | Pa |

| Participants responding to motivation questions | 310 | 176 | 134 | |

| Altruism | 188 (61) | 104 (59) | 84 (63) | .52 |

| Giving back to the community | 118 | 64 | 54 | |

| Helping others is important | 125 | 71 | 54 | |

| The idea of doing something “good” | 40 | 19 | 21 | |

| Volunteering is a social responsibility | 58 | 29 | 29 | |

| Wanted to help in a research study | 7 | 4 | 3 | |

| To make a difference and help schoolchildren | 3 | 1 | 2 | |

| Ideology | 204 (66) | 109 (62) | 95 (71) | .10 |

| Worthwhile cause | 170 | 91 | 79 | |

| Civil rights (helping the underserved) | 123 | 65 | 58 | |

| Religious reasons, calling from God | 28 | 18 | 10 | |

| To be a better person | 72 | 37 | 35 | |

| Material reward | 87 (28) | 46 (26) | 41 (31) | .39 |

| It is good for me | 68 | 37 | 31 | |

| Money for participation would be helpful | 22 | 11 | 11 | |

| Relative (child) attends a school with EC | 1 | 0 | 1 | |

| Good for my health (physical, mental, etc.) | 1 | 0 | 1 | |

| Status reward | 27 (9) | 13 (7) | 14 (10) | .34 |

| Learn new skills | 23 | 12 | 11 | |

| Gain recognition in the community | 2 | 0 | 2 | |

| Gain experience or connections to get a job | 4 | 2 | 2 | |

| Social relationships | 56 (18) | 29 (16) | 27 (20) | .41 |

| Make friends | 42 | 20 | 22 | |

| Be with friends in existing school with EC | 8 | 6 | 2 | |

| Make friends with people of different age | 30 | 12 | 18 | |

| Leisure time | 120 (39) | 71 (40) | 49 (37) | .50 |

| Bored | 85 | 48 | 37 | |

| Make better use of spare time | 112 | 67 | 45 | |

| Personal growth | 75 (24) | 38 (22) | 37 (28) | .22 |

| Grow personally | 54 | 27 | 27 | |

| Have a sense of purpose in life | 40 | 20 | 20 | |

| Feel valued and needed | 21 | 9 | 12 | |

| Want to learn | 23 | 12 | 11 |

Note. EC = Experience Corps Baltimore City. The total number of participants who were screened and were eligible was N = 368.

Between participants recruited and not recruited.

DISCUSSION

The social marketing conceptual framework presented here demonstrates how EC, as initially designed,5 is consistent with the social marketing principles of product, place, price, and promotion. Recruitment for this first year of the BECT also provides a template for future social marketing campaigns based on national or community service programs that also serve as public health interventions. The messages developed in this first year of recruitment for the BECT—“Share your wisdom” and “Make a difference”—reflected the actual product of generative activity rather than the core product of increased physical, cognitive, and social activity. We demonstrated that a promotion message that appealed to leaving a legacy and contributing to the next generation could recruit older adults successfully across multiple strategies that included (1) word of mouth, (2) selective media such as community outreach and direct mail, and (3) mass media in the form of radio advertisements. Our recruitment results also confirmed 2 other aspects of the EC model: that the local public school represents a place that is attractive to older African American volunteers who are at high risk for poor health outcomes, and that although the associated stipend was important in overcoming the price or cost of high-intensity volunteering, it was not the primary motive for participation in the first year of the trial.

These recruitment results support the EC model of embedding health promotion programs in local community service programs, and demonstrate that these programs can be promoted through word of mouth, selective media, and mass media. There was some preliminary evidence for synergy between strategies, as 23% of participants reported more than 1 source of information. This is consistent with prior research reporting that individuals need to hear a message as many as 3 times before it registers.39 Given many older adults’ concerns about financial scams, we theorize that our most successful recruitment strategies were associated with trusted sources of information, such as a referral from a friend or a bulletin at religious services. Although word of mouth and local grassroots media channels were important recruitment strategies for this community-based model, we do not know if they would be as effective in recruitment for a national service program. Finally, although mass media is an important source of recruitment for this ongoing National Institute on Aging–sponsored trial, local community service programs would probably require outside support to be able to afford a mass media promotion campaign.

The marketing principles of product, price, place, and promotion can guide future research on national and community service–based public health interventions for older adults. The ongoing BECT will determine if this particular augmented product, EC, can not only promote physical, cognitive, and social activity but also prevent incident mobility-associated disability, falls, and memory loss and promote self-efficacy. In the end, this may lead to reduced health care costs among older adult participants.40 Future research on price should be done to determine the importance of specific barriers such as transportation and of benefits such as the Segal AmeriCorps Education Award. This award can be used to support future education expenses of AmeriCorps members who have completed their term of service, or can be transferred to the grandchildren of AmeriCorps members who are aged 55 years or older. Additional research on place will be needed to determine the health potential of other civic engagement models, such as volunteering on public lands.41 Finally, although this analysis of the first year of the BECT further demonstrates the ability of a generative message to attract older adults, additional research will be required to measure the effectiveness of specific messages and strategies over time.

Social marketing interventions based on the EC model could serve to decrease the “structural lag” in our social institutions, in which older adults are currently provided insufficient postretirement opportunities that both are appealing and promote a healthy lifestyle. Commercial marketing has tended to focus on younger adults because they are perceived as being at a life stage when they are determining lifetime spending. Social marketers may find recently retired older adults particularly open to generative opportunities at a time when they are at increased risk of physical inactivity and social isolation.5,28,42,43 Increasing the visibility of older adult volunteers could also make volunteering more attractive to potential older volunteers by providing “social proof” to potential volunteers that other older adults are engaged in community service.33

This analysis has several limitations. It details the development of the initial recruitment strategies for the BECT and evaluates the feasibility of these strategies. Ongoing work in this area will result in an analysis of the comparative effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of specific strategies once recruitment for the BECT has been completed. Further research is required to determine how to best ascribe volunteer motives within the conceptual framework of generativity. Our recruitment resulted in a cohort composed predominately of older African American women. Although this could be seen as a limitation, there is a need for interventions that can attract groups that are underrepresented in most randomized controlled trials and are at high risk of physical inactivity or poor health outcomes.11,32 While we have demonstrated an ability to attract older African Americans, future research using the social marketing model could assist the development of new interventions that might appeal to other demographic groups. For example, a model for coaching sports among youths might attract more older men, and Spanish or Mandarin immersion schools might recruit older immigrant adults, who may be socially isolated, as tutors.44 Finally, the recruitment strategy described here was for a randomized controlled trial; recruitment for a volunteer program that does not involve randomization is likely to have a wider appeal.

Any expansion of national and community service should consider models designed to simultaneously serve as public health interventions. This approach could create a potential “win-win” situation for both older adults and society. EC demonstrates how marketing principles could be used to guide future health policy initiatives based on older adult national and community service. For example, although EC appeals to “generative motives,” other motives such as patriotism, social justice, or the environment might serve as the actual product in newly developed public health interventions. Although EC is a domestic civic engagement program, the Peace Corps has begun to recruit increasing numbers of middle-aged and older Americans, which opens the possibility of international service as a place for future interventions.45 Proposals such as “encore fellowships” would provide additional support for older adult volunteering and further reduce the cost or price of high-intensity volunteering.46 Finally, future promotion efforts would benefit from the associated authority of a trusted spokesperson or organization.33 One example is the “call to service” campaign on Martin Luther King Day in 2009 that featured, among other things, e-mails from the future First Lady, Michelle Obama. New models of national and community service that also serve as health promotion interventions need to be developed before the Baby Boom generation passes into the traditional age of retirement.

Acknowledgments

Funding support for this article was provided in part by the National Institute on Aging (NIA; contracts P01 AG027735, 3P01AG027735-03S2, and 3P01AG027735-02S3); the NIA Johns Hopkins Older Americans Independence Center (contract P30-AG02133) and the NIA Women's Health and Aging Study (contract R37-AG19905); the John A. Hartford Foundation; and the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation.

We thank the Greater Homewood Community Corporation, Experience Corps, Civic Ventures, the Baltimore City Public School System, the City of Baltimore, the Commission on Aging and Retirement Education, Green + Associates, Kaiser Associates Strategic Communications, the Baltimore City Retirees Association, the American Association of Retired Persons, and the Harry and Janette Weinberg Foundation for ongoing vision and support. Special thanks go to the staff and recruited participants of the Baltimore Experience Corps Trial.

Human Participant Protection

This study was approved by the Johns Hopkins School of Medicine institutional review board. There is an active NIH-sponsored Data Safety Monitoring Board that reviews all adverse events and meets twice a year.

References

- 1.The White House Blog A call to service. 2009. Available at: http://www.whitehouse.gov/blog/09/04/21/A-Call-to-Service. Accessed July 3, 2009

- 2.Fink K, Clark B. Behavioral counseling in primary care to promote physical activity. Am Fam Physician 2003;67(9):1975–1976 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pirani S, Reizes T. The Turning Point Social Marketing National Excellence Collaborative: integrating social marketing into routine public health practice. J Public Health Manag Pract 2005;11(2):131–138 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Huhman M, Potter LD, Wong FL, Banspach SW, Duke JC, Heitzler CD. Effects of a mass media campaign to increase physical activity among children: year-1 results of the VERB campaign. Pediatrics 2005;116(2):e277–e284 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fried LP, Carlson MC, Freedman M, et al. A social model for health promotion for an aging population: initial evidence on the Experience Corps model. J Urban Health 2004;81(1):64–78 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rebok GW, Carlson MC, Glass TA, et al. Short-term impact of Experience Corps participation on children and schools: results from a pilot randomized trial. J Urban Health 2004;81(1):79–93 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fries JF. Aging, natural death, and the compression of morbidity. N Engl J Med 1980;303(3):130–135 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kotler P, Lee NR. Social Marketing Influencing Behaviors for Good 3rd ed.Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications; 2008 [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kennedy MG, Crosby RA. Prevention marketing: an emerging integrated framework. : DiClemente RJ, Crosby RA, Kegler MC, Emerging Theories in Health Promotion Practice and Research San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass; 2002:255–284 [Google Scholar]

- 10.Martinez I, Frick K, Glass TA, et al. Engaging older adults in high impact volunteering that enhances health: recruitment and retention in The Experience Corps Baltimore. J Urban Health 2006;83(5):941–953 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Surgeon general's report on physical activity and health. JAMA 1996;276(7):522. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Healthy People 2010: Understanding and Improving Health 2nd ed Washington, DC: Dept of Health and Human Services; 2000 [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fiatarone MA, O'Neill EF, Ryan ND, et al. Exercise training and nutritional supplementation for physical frailty in very elderly people. N Engl J Med 1994;330(25):1769–1775 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nelson ME, Fiatarone MA, Morganti CM, Trice I, Greenberg RA, Evans WJ. Effects of high-intensity strength training on multiple risk factors for osteoporotic fractures. A randomized controlled trial. JAMA 1994;272(24):1909–1914 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Simonsick EM, Guralnik JM, Volpato S, Balfour J, Fried LP. Just get out the door! Importance of walking outside the home for maintaining mobility: findings from the Women's Health and Aging Study. J Am Geriatr Soc 2005;53(2):198–203 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Carlson MC, Saczynski JS, Rebok GW, et al. Exploring the effects of an “everyday” activity program on executive function and memory in older adults: Experience Corps. Gerontologist 2008;48(6):793–801 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tan EJ, Xue QL, Li T, Carlson MC, Fried LP. Volunteering: a physical activity intervention for older adults—the Experience Corps program in Baltimore. J Urban Health 2006;83(5):954–969 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Carlson MC, Erickson KI, Kramer AF, et al. Evidence for neurocognitive plasticity in at-risk older adults: the Experience Corps program. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 2009;64(12):1275–1282 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tan EJ, Rebok GW, Yu Q, et al. The long-term relationship between high-intensity volunteering and physical activity in older African American women. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci 2009;64(2):304–311 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Erikson E. Vital Involvement in Old Age New York, NY: W. W; Norton & Co; 1986 [Google Scholar]

- 21.Eng E, Parker EA. Natural helper models to enhance a community's health and competence. : DiClemente RJ, Crosby RA, Kegler MC, Emerging Theories in Health Promotion Practice and Research San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass; 2002:126–156 [Google Scholar]

- 22.Glass TA, Freedman M, Carlson MC, et al. Experience Corps: design of an intergenerational program to boost social capital and promote the health of an aging society. J Urban Health 2004;81(1):94–105 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Harris AH, Thoresen CE. Volunteering is associated with delayed mortality in older people: analysis of the longitudinal study of aging. J Health Psychol 2005;10(6):739–752 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lum TY, Lightfoot E. The effects of volunteering on the physical and mental health of older people. Res Aging 2005;27(1):31–55 [Google Scholar]

- 25.Morrow-Howell N, Hinterlong J, Rozario PA, Tang F. Effects of volunteering on the well-being of older adults. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci 2003;58(3):S137–S145 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Oman D, Thoresen CE, McMahon K. Volunteerism and mortality among the community-dwelling elderly. J Health Psychol 1999;4(3):301–316 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Musick MA, Herzog AR, House JS. Volunteering and mortality among older adults: findings from a national sample. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci 1999;54(3):S173–S180 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Freedman M. Prime Time: How Baby Boomers Will Revolutionize Retirement and Transform America New York, NY: Public Affairs; 1999 [Google Scholar]

- 29.Foster-Bey J, Dietz N, Grimm R., Jr Volunteers mentoring youth: implications for closing the mentoring gap. Corporation for National and Community Service, Office of Research and Policy Development. 2006. Available at: http://www.nationalservice.gov/pdf/06_0503_mentoring_report.pdf. Accessed April 20, 2009

- 30.Eyler AE, Wilcox S, Matson-Koffman D, et al. Correlates of physical activity among women from diverse racial/ethnic groups. J Womens Health Gend Based Med 2002;11(3):239–253 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wilson J. Volunteering. Annu Rev Sociol 2000;26:215–240 [Google Scholar]

- 32.Adler NE. Community preventive services. Do we know what we need to know to improve health and reduce disparities? Am J Prev Med 2003;24(3 suppl):10–11 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cialdini RB. Influence: Science and Practice 5th ed.Boston, MA: Pearson; Education; 2009 [Google Scholar]

- 34.Folstein MF, Folstein SE, McHugh PR. “Mini-mental state”: a practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. J Psychiatr Res 1975;12(3):189–198 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wilkinson GS. WRAT3: Wide Range Achievement Test 3 Wilmington, DE: Wide Range Inc; 1993 [Google Scholar]

- 36.Stewart AL, Mills KM, King AC, Haskell WL, Gillis D, Ritter PL. CHAMPS physical activity questionnaire for older adults: outcomes for interventions. Med Sci Sports Exerc 2001;33(7):1126–1141 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Fischer LR, Schaffer KB. Older Volunteers: A Guide to Research and Practice Newbury Park, CA: Sage Publications Inc; 1993 [Google Scholar]

- 38.Resnicow K, McCarty F, Blissett D, Wang T, Heitzler C, Lee RE. Validity of a modified CHAMPS physical activity questionnaire among African-Americans. Med Sci Sports Exerc 2003;35(9):1537–1545 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Naples MJ. Effective Frequency: The Relationship Between Frequency and Advertising Effectiveness New York, NY: Association of National Advertisers Inc; 1979 [Google Scholar]

- 40.Frick KD, Carlson MC, Glass TA, et al. Modeled cost-effectiveness of the Experience Corps Baltimore based on a pilot randomized trial. J Urban Health 2004;81(1):106–117 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Norton G, Suk M. America's public lands and waters: the gateway to better health? Am J Law Med 2004;30(2–3):237–243 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Chung S, Domino ME, Stearns SC, Popkin BM. Retirement and physical activity analyses by occupation and wealth. Am J Prev Med 2009;36(5):422–428 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Andersen LB, Schnohr P, Schroll M, Hein HO. All-cause mortality associated with physical activity during leisure time, work, sports, and cycling to work. Arch Intern Med 2000;160(11):1621–1628 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Brown PL. Old Immigrants, invisible with “nobody to talk to.” New York Times August 30, 2009:A1 [Google Scholar]

- 45.Jordan M. Peace Corps opens office in Mexico; older volunteers bring requested technical, business expertise. Washington Post November 10, 2004:A16 [Google Scholar]

- 46.Greene K. Law opens up “encore” careers. Wall Street Journal April 2, 2009. Available at: http://online.wsj.com/article/SB123863704304281321.html. Accessed September 1, 2009 [Google Scholar]