Abstract

Purpose

Protein downregulation and hypermethylation of Ras association domain family 1A (RASSF1A) has been recognized as an important early event in different classes of carcinogenesis, but clinicopathological significance of RASSF1A protein expression and methylation in hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) remains largely unknown. The aim of the study was to investigate the expression of RASSF1A protein and methylation in HCC and their clinical significance.

Methods

Immunohistochemistry was employed to detect the expression of RASSF1A proteins in liver tissue microarrays. Aberrant promoter hypermethylation of RASSF1A was investigated in DNA from HCC, matching noncancerous tissues and serum of 35 HCC patients by methylation-specific PCR.

Results

RASSF1A protein expression in HCC was significantly lower than that in noncancerous (p = 0.015) and paracancerous tissues (p = 0.017). In addition, reduced RASSF1A protein expression is related to TNM stage, metastasis, α-fetoprotein, portal vein embolus, capsular infiltration, and multiple tumor nodes. Furthermore, RASSF1A promoter methylation in HCC was significantly higher than that in noncancerous liver tissues (p < 0.05). Meanwhile, RASSF1A promoter hypermethylation was detected in 14 in the serum DNA from HCC patients, whereas no hypermethylation was detected in the normal controls. Hypermethylation of RASSF1A in HCC serum and tissues was negatively correlated with the expression of RASSF1A protein expression (p < 0.05).

Conclusions

The loss or abnormal protein downregulation and the promoter hypermethylation of RASSF1A could play important roles in the tumorigenesis development and metastases of HCC. The detection of the promoter hypermethylation of RASSF1A in serum DNA could be a valuable biomarker for early-stage diagnosis in populations at high risk of HCC.

Keywords: RASSF1A, Hepatocellular carcinoma, Immunohistochemistry, Promoter hypermethylation, Tissue microarrays (TMAs), DNA

Introduction

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) is one of the most common malignancies worldwide with an increasing incidence [1]. Although the prognosis of patients with HCC has marginally improved over the last two decades, the 5-year survival rate still remains poor, currently 5%, due to the late diagnosis. The majority of patients with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma do not survive for longer than 6 months from the time of diagnosis [2]. The Ras association domain family 1A (RASSF1A) gene is located in chromosome 3p21.3 [3]. Various classes of tumors demonstrate a loss of RASSF1A protein. A subset of tumors was identified that exhibits substantial RASSF1A protein expression and shows increased tumor progression, such as renal cell carcinoma [4], head and neck squamous cell carcinoma [5], ductal carcinoma in situ [6], endometrial carcinoma [7], esophageal and nasopharyngeal carcinoma [8], gastric carcinoma [9], etc. However, to date, no studies have investigated the association between RASSF1A protein expression and clinicopathological features of HCC among a large patient number by immunostaining. There is no information presently available about the protein status of RASSF1A in liver tissue microarrays (TMAs). Recent studies have also shown that inactivation of RASSF1A promoter by methylation was detectable in tumor cell lines and tissues, such as lung [10], gallbladder [11], breast [12], kidney [13], prostate [14], endometrium [7], bladder [15], bile ducts [16], stomach [17], and colon and rectum carcinoma [17]. The hypermethylation of RASSF1A suggests new perspectives for the diagnosis of malignant tumor. The methylation of RASSF1A was detected in the serum DNA of HCC patients by Yeo et al. [18] and Zhang et al. [19], as well as in the tissue DNA of HCC by Zhang et al. [20], Di Gioia et al. [21], Tischoff et al. [22], and Schagdarsurengin et al. [23]. But different groups obtained different data for the detection of hypermethylation of RASSF1A in HCC. What is more, the conclusions on the relationship between the hypermethylation of RASSF1A and the clinicopathological features differed for different groups. Therefore, in the present study, the expression and clinicopathological significance of RASSF1A protein in the hepatocellular carcinogenesis were investigated by immunohistochemistry (IHC) and TMA. In addition, the hypermethylation of RASSF1A in serum and tissue DNA of HCC was evaluated by methylation-specific PCR (MSP). The value of expression and hypermethylation of RASSF1A in the prognostic significance of HCC was further explored in Guangxi Zhuang Autonomous Region, People’s Republic of China.

Materials and methods

Patients

All cases were initial hepatectomies performed to avoid the secondary changes of healing after operation or biopsy in the First Affiliated Hospital, Guangxi Medical University, People’s Republic of China. All the diagnosis and classifications for the samples involved in the present study were based on histology by the same pathologist. Clinical information was obtained from medical records. Written informed consent to use all the samples for research was obtained from the patients and clinicians. The study was approved by the institutional review committee.

Patients for TMA study

The retrospective TMA study included 96 cases of HCCs, 24 cases of paraneoplastic liver tissue, and 85 cases of noncancerous liver tissues, including 62 cases of cirrhosis and 23 cases of normal liver from surrounding liver cavernous hemangioma tissue. The clinicopathological parameters, including age, gender, pathological grade, clinical stages, metastasis and recurrence, paracirrhosis, α-fetoprotein (AFP), HBV and HCV infection, portal vein tumor embolus, tumor capsular, tumor nodes and tumor size, were shown in Table 1. All cases were randomly chosen from the hepatectomies performed over a 1- to 2-year span between May 2002 and December 2005.

Table 1.

Relationship between expression of RASSF1A in HCC TMAs and clinicopathological parameters

| Clinicopathological parameters | n | RASSF1A expression | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n (+) | n (−) | n (+++) | χ2 | p | ||

| Tissue | ||||||

| HCC | 96 | 38 | 58 | 39.58 | 5.893 vs. noncancerous | 0.015 |

| Paracancerous | 24 | 16 | 8 | 66.67 | 5.690 vs. HCC | 0.017 |

| Noncancerous | 85 | 49 | 36 | 57.65 | 0.633 vs. paracancerous | 0.426 |

| Age | ||||||

| ≥50 | 42 | 22 | 20 | 52.38 | 5.113 | 0.024 |

| <50 | 54 | 16 | 38 | 29.63 | ||

| Gender | ||||||

| Male | 92 | 37 | 55 | 45.12 | 0.371 | 0.542 |

| Female | 4 | 1 | 3 | 25 | ||

| Pathological grade | ||||||

| I, II | 64 | 30 | 34 | 46.88 | 5.353 | 0.069 |

| III, IV | 32 | 8 | 24 | 25 | ||

| Clinical TNM stages | ||||||

| I, II | 61 | 35 | 26 | 57.38 | 22.151 | 0.000 |

| III, IV | 35 | 3 | 32 | 8.57 | ||

| Metastasis and recurrence | ||||||

| Yes | 41 | 2 | 39 | 4.88 | 32.086 | 0.000 |

| No | 44 | 28 | 16 | 63.64 | ||

| Paracirrhosis | ||||||

| With | 74 | 27 | 47 | 36.49 | 1.295 | 0.255 |

| Without | 22 | 11 | 11 | 50 | ||

| AFP (μg/L) | ||||||

| ≥400 | 55 | 14 | 41 | 25.45 | 10.75 | 0.001 |

| <400 | 41 | 24 | 17 | 58.54 | ||

| HBV | ||||||

| Positive | 80 | 32 | 48 | 40 | 0.928 | 0.324 |

| Negative | 16 | 6 | 10 | 37.5 | ||

| HCV | ||||||

| Positive | 5 | 1 | 4 | 20 | 1.107 | 0.276 |

| Negative | 91 | 37 | 54 | 40.66 | ||

| Portal vein tumor embolus | ||||||

| With | 31 | 3 | 28 | 9.68 | 17.122 | 0.000 |

| Without | 65 | 35 | 30 | 53.85 | ||

| Tumor capsular infiltration | ||||||

| No capsular or capsular infiltration | 64 | 16 | 48 | 25 | 17.074 | 0.000 |

| No capsular infiltration | 32 | 22 | 10 | 68.75 | ||

| Tumor nodes | ||||||

| Multi | 31 | 5 | 26 | 16.13 | 10.532 | 0.000 |

| Single | 65 | 33 | 32 | 50.77 | ||

| Tumor size (cm) | ||||||

| ≥5 | 56 | 19 | 37 | 33.93 | 1.797 | 0.18 |

| <5 | 40 | 19 | 21 | 47.5 | ||

The ages of HCC patients ranged from 23 to 81 years, with a mean of 49 years. The 24 cases of corresponding paraneoplastic tissue were taken at least 2 cm from the cancerous node. Among 96 HCC patients, 85 cases were followed up for 20 months. Forty-one cases had metastasis, 44 cases did not

Patients for MSP study

The studied population for MSP consisted of 35 patients who were diagnosed with operable HCC from February to July 2006. The preoperative peripheral blood was harvested from 35 cases of HCC and 10 cases of healthy blood donors as controls. Patients’ demographics were obtained and included age, gender, pathological grade, HBV, paracirrhosis, AFP, HBV and HCV infection, portal vein tumor embolus, tumor capsular, tumor nodes, and tumor size (Table 2). RASSF1A protein expression analysis with IHC was also performed in these 35 cases of liver tissues.

Table 2.

Relationship between hypermethylation of RASSF1A in serum, cancerous, and paracancerous DNA, protein expression of RASSF1A in HCC tissues and clinicopathological parameters of HCC

| Clinicopathological parameters | n | Methylation serum [n (+)] | χ2 | p | Methylation HCC [n (+)] | χ2 | p | Methylation paracancerous [n (+)] | χ2 | p | IHC HCC [n (+)] | χ2 | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | |||||||||||||

| ≥50 | 16 | 6 | 0.077 | 0.782 | 15 | 0.781 | 0.377 | 7 | 0.696 | 0.404 | 9 | 2.116 | 0.034 |

| <50 | 19 | 8 | 16 | 11 | 4 | ||||||||

| Gender | |||||||||||||

| Male | 28 | 12 | 0.476 | 0.490 | 26 | 2.540 | 0.111 | 15 | 0.257 | 0.612 | 13 | 0.000 | 1.000 |

| Female | 7 | 2 | 5 | 3 | 0 | ||||||||

| Pathological grade | |||||||||||||

| I–II | 20 | 8 | 0.000 | 1.000 | 17 | 0.588 | 0.443 | 10 | 0.038 | 0.845 | 11 | 2.150 | 0.032 |

| III–IV | 15 | 6 | 14 | 8 | 2 | ||||||||

| HBV | |||||||||||||

| Positive | 30 | 11 | 0.972 | 0.324 | 27 | 0.423 | 0.515 | 16 | 0.305 | 0.581 | 11 | 0.141 | 0.933 |

| Negative | 5 | 3 | 4 | 2 | 2 | ||||||||

| HCV | |||||||||||||

| Positive | 2 | 2 | 1.817 | 0.078 | 2 | 0.51 | 0.613 | 1 | 0.967 | 0.276 | 0 | 1.103 | 0.674T |

| Negative | 33 | 12 | 29 | 17 | 13 | ||||||||

| Paracirrhosis | |||||||||||||

| With | 23 | 10 | 0.338 | 0.561 | 21 | 0.495 | 0.482 | 12 | 0.015 | 0.903 | 9 | 1.621 | 0.302 |

| Without | 12 | 4 | 10 | 6 | 4 | ||||||||

| AFP (μg/L) | |||||||||||||

| ≥400 | 24 | 9 | 0.199 | 0.656 | 22 | 0.723 | 0.395 | 14 | 1.457 | 0.227 | 3 | 3.086 | 0.007 |

| <400 | 11 | 5 | 9 | 4 | 10 | ||||||||

| Portal vein tumor embolus | |||||||||||||

| With | 6 | 2 | 0.134 | 0.714 | 5 | 0.196 | 0.658 | 4 | 0.673 | 0.412 | 1 | 2.732 | 0.022 |

| Without | 29 | 12 | 26 | 14 | 12 | ||||||||

| Tumor capsular | |||||||||||||

| With | 14 | 5 | 0.179 | 0.673 | 11 | 2.305 | 0.129 | 6 | 0.686 | 0.407 | 7 | 2.096 | 0.036 |

| Without | 21 | 9 | 20 | 12 | 6 | ||||||||

| Tumor nodes | |||||||||||||

| Multi | 13 | 5 | 0.213 | 0.648 | 12 | 1.687 | 0.179 | 7 | 0.603 | 0.398 | 3 | 1.548 | 0.191 |

| Single | 22 | 9 | 19 | 11 | 10 | ||||||||

| Tumor size (cm) | |||||||||||||

| ≥5 | 26 | 11 | 0.224 | 0.636 | 24 | 1.394 | 0.238 | 13 | 0.083 | 0.774 | 8 | 1.307 | 0.335 |

| <5 | 9 | 3 | 7 | 5 | 5 | ||||||||

None of the serum samples from ten healthy blood donors displayed RASSF1A promoter methylation, whereas methylation was detected in 14 (40%) of the 35 serum DNA samples of HCC patients. No RASSF1A methylation was examined in 5 normal controls. RASSF1A promoter methylation was detected in 31 (88.6%) of 35 HCC tissues of HCC patients, significantly higher than that in the noncancerous liver tissues (51.4%, 18/35, p < 0.05)

Methods

Tissue microarrays

The representative area of each tumor was identified by microscopy from each case and the corresponding needed spots were marked on the tissue block according to previously reported methods [24, 25]. Single 0.6-mm cores of tissue were used to assemble the arrays. The three tissue array blocks contained 96 HCC, 24 paraneoplastic livers, and 85 (62 liver cirrhosis and 23 normal livers) specimens, respectively. The blocks were heated at 42°C for 3 min and then routinely sectioned at 4-μm thickness.

Immunohistochemistry

For the IHC studies, the procedure employed was described elsewhere [4], with the monoclonal antibodies anti-RASSF1A (Abcam). Sections of stomach tissue were used as positive controls for RASSF1A. The primary antibody was replaced by phosphate buffer solution (PBS) for negative controls. The positive signal for RASSF1A appeared as yellowish brown in the cytoplasm of the cells. One hundred cells from five representative areas from each case were counted. The staining results were evaluated according to the immunodetection of stain intensity and amounts of positive cells by two pathologists (G.C. and P.L.), who discussed each case until they reached a consensus. Stain intensity was up to the standard of the relative stain intensity of most cells. The degree of staining was subdivided as follows: the stain intensity could be from 0 to 3 (0, no staining; 1, focal or fine granular, weak staining; 2, linear or cluster, strong staining; and 3, diffuse, intense staining); and the positive cells in the observed gastric mucosa ranged from 0 to 3 in percentage (0, no staining; 1, <30%; 2, 30–70%; and 3, >70%). The samples were scored by their summation: 0–1 (−); 2–3 (+); 4 (++); 5–6 (+++). Any staining score 2 or above (+) was considered as positive expression.

DNA extraction

Liver tissues were snap-frozen in liquid nitrogen-cooled isopentane and stored at −80°C until further use. High-molecular-weight DNA was extracted from the liver tissues according to the previously described method [18]. DNA from serum was extracted using the QIAamp Blood Mini Kit (Qiagen, Germany) according to the manufacturer’s recommendations. Serum samples were applied at 400 mL/column, and a final volume of 100 mL of serum DNA was collected and stored at −80°C until further processing.

Methylation-specific PCR

Methylation of the promoter region was examined by bisulfite DNA modification followed by MSP. Bisulfite modification using the CpGenomeTM DNA Modification Kit (Chmicon, S7820; USA) was performed according to the manufacturer’s instructions. DNA amplification was carried out in a GeneAmp PCR System 2400 (Perkin Elmer, USA) using CpG WIZ RASSF1A Amplification Kit (Chmicon, S7813; USA). Thirty-five cycles were used for DNA amplification. The thermal profile consisted of an initial denaturation step of 95°C for 5 min, followed by repetitions of 95°C for 45 s, 55°C for 45 s, and 72°C for 60 s, with a final extension step of 72°C for 5 min. PCR products were analyzed by agarose gel electrophoresis and ethidium bromide staining. A blank with water was used as a negative control. Samples were scored as methylated when there was a clearly visible band on the gel with the methylated primers. Triplication was performed for all experiments to ensure the reproducibility of the results.

Statistical analysis

Statistical significance was evaluated by χ2 test for categorical variables and Spearman’s rank correlation for correlation between RASSF1A expression and promoter hypermethylation with SPSS 13.0. Difference was deemed significant when p < 0.05.

Results

Quality of TMAs

Good-quality TMAs were used in the study. The H&E-stained TMAs were highly representative of their donor tissue. All of the samples in the TMAs were suitable in the present study.

Expression of RASSF1A in different liver tissues

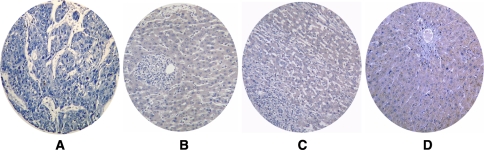

Absent or weak RASSF1A signals could be detected in HCC tissues. In contrast, moderate to strong RASSF1A immunostaining was localized within the cytoplasm of liver cells in normal, cirrhotic, and paracancerous liver sections (Figs. 1, 2, 3). As shown in Table 1, the expression of RASSF1A in HCC cases was significantly lower than that in the paraneoplastic and noncancerous liver tissues. But there was no significant difference between the RASSF1A expression in paracancerous and noncancerous tissues.

Fig. 1.

RASSF1A protein expression detected by immunohistochemistry in liver tissue microarrays (TMAs). a No signal of RASSF1A protein was detected in hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) tissue. b–d RASSF1A protein immunostaining. The signal was localized within the cytoplasm of liver cells in paracancerous liver tissues (b), cirrhotic liver tissues (c) and normal liver tissues (d), respectively (immunohistochemistry, DAB ×100)

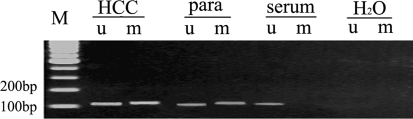

Fig. 2.

Methylation status of RASSF1A in hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC), paracancerous, and serum. M molecular-weight marker, HCC HCC tissues, para paracancerous liver tissues, serum paired serum, H2O water as negative control, u unmethylation-specific primers were used in methylation-specific PCR (MSP), m methylation-specific primers were used in MSP. The detection of a band of 108 and 111 bp indicates the presence of the unmethylated sequences and the methylated sequences, respectively, in the case of patient 28 (Table 3). Partial methylation was observed in HCC and paracancerous tissues, whereas only the unmethylated sequences were detected in serum of this HCC patient. A blank with water was used as a negative control

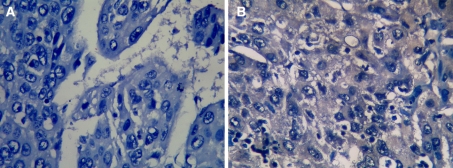

Fig. 3.

RASSF1A protein expression detected by immunohistochemistry in clinical hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) tissues. a No signal of RASSF1A protein was detected by immunostaining in HCC tissue of case 4. b RASSF1A protein was detected in HCC tissues of case 1. The signal was localized within the cytoplasm of tumor cells (IHC, DAB × 400)

Relationship between RASSF1A expression and the clinicopathological parameters of HCC

The expression of RASSF1A in HCC tissue in clinical TNM stages I and II was significantly higher than that in stages III and IV. RASSF1A expression in the cases without metastasis within 20 months was significantly higher than that in the group with metastasis. RASSF1A protein expression in the groups of AFP 400 μg/L or more, portal vein tumor embolus, tumor capsular infiltration, and multitumor nodes was significantly lower than that in the groups of AFP less than 400 μg/L, without tumor embolus, without tumor capsular infiltration, and single tumor node (Table 1).

Methylation of the RASSF1A in HCC tissues and paired plasma

Aberrant methylation of the RASSF1A promoter region was detected in 14 samples of the serum DNA of HCC patients from 35 (40%) with MSP. None of the serum samples from 10 healthy blood donors displayed RASSF1A promoter methylation (Tables 2, 3). RASSF1A promoter methylation was detected in 31 cases (88.6%) in the 35 HCC tissues, significantly higher than that in the noncancerous liver tissues (51.4%, 18/35, p < 0.05). No RASSF1A methylation was examined in five normal controls.

Table 3.

Relationship between RASSF1A hypermethylation in serum, cancerous, and paracancerous DNA, protein expression of RASSF1A in HCC, and clinicopathological parameters

| No. | Methylation | IHC | Clinicopathological parameters | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Serum | HCC tissues | Paracancerous tissues | HCC tissues | Age | Gender | Pathological grade | HBV | HCV | Paracirrhosis | AFP (μg/L) | Portal vein tumor embolus | Tumor capsular | Tumor nodes | Tumor size (cm) | |

| 1 | − | + | − | + | <50 | M | I–II | − | − | Yes | <400 | No | No | Single | <5 |

| 2 | − | + | − | + | <50 | M | I–II | + | − | Yes | <400 | No | No | Single | <5 |

| 3 | − | + | − | + | ≥50 | M | I–II | + | − | Yes | ≥400 | No | No | Single | <5 |

| 4 | + | + | + | − | ≥50 | M | III–IV | − | − | Yes | ≥400 | No | Yes | Single | <5 |

| 5 | + | + | + | − | <50 | M | III–IV | − | − | Yes | ≥400 | No | Yes | Single | ≥5 |

| 6 | + | + | + | − | <50 | M | I–II | + | − | Yes | ≥400 | No | Yes | Single | <5 |

| 7 | + | + | + | − | <50 | M | I–II | + | − | No | ≥400 | No | Yes | Single | <5 |

| 8 | + | + | + | − | <50 | M | III–IV | + | − | Yes | <400 | No | Yes | Single | ≥5 |

| 9 | + | + | + | − | ≥50 | M | I–II | + | − | Yes | ≥400 | No | Yes | Single | ≥5 |

| 10 | + | + | + | − | <50 | M | III–IV | + | − | Yes | ≥400 | No | No | Single | ≥5 |

| 11 | − | + | − | + | ≥50 | M | I–II | + | − | No | ≥400 | No | Yes | Single | ≥5 |

| 12 | + | + | + | − | <50 | M | III–IV | + | − | Yes | ≥400 | No | Yes | Single | <5 |

| 13 | + | + | + | − | <50 | M | III–IV | + | − | Yes | <400 | No | Yes | Single | ≥5 |

| 14 | − | + | − | + | ≥50 | M | I–II | + | − | No | <400 | No | Yes | Single | <5 |

| 15 | − | + | − | + | ≥50 | M | I–II | + | − | Yes | <400 | No | Yes | Single | ≥5 |

| 16 | − | + | − | + | ≥50 | M | I–II | + | − | No | <400 | No | No | Single | <5 |

| 17 | − | − | − | + | ≥50 | M | III–IV | − | − | No | <400 | No | Yes | Single | ≥5 |

| 18 | − | − | − | + | <50 | M | III–IV | + | − | Yes | <400 | No | No | Multi | ≥5 |

| 19 | − | + | − | + | ≥50 | M | I–II | + | − | Yes | <400 | No | Yes | Multi | ≥5 |

| 20 | − | + | − | + | <50 | M | I–II | + | − | Yes | <400 | No | Yes | Single | ≥5 |

| 21 | + | + | + | − | <50 | M | III–IV | + | − | Yes | <400 | No | No | Single | ≥5 |

| 22 | − | − | − | + | ≥50 | M | I–II | + | − | Yes | ≥400 | No | Yes | Single | ≥5 |

| 23 | − | − | − | + | ≥50 | M | I–II | + | − | Yes | <400 | Yes | No | Multi | ≥5 |

| 24 | + | + | + | − | ≥50 | M | I–II | + | − | Yes | ≥400 | Yes | No | Multi | ≥5 |

| 25 | + | + | + | − | <50 | M | III–IV | + | − | Yes | ≥400 | Yes | Yes | Multi | ≥5 |

| 26 | + | + | + | − | <50 | M | I–II | − | + | No | ≥400 | Yes | Yes | Multi | ≥5 |

| 27 | + | + | − | − | ≥50 | M | III–IV | + | + | Yes | ≥400 | Yes | Yes | Multi | ≥5 |

| 28 | − | + | + | − | <50 | M | I–II | + | − | Yes | ≥400 | Yes | Yes | Multi | ≥5 |

| 29 | − | + | + | − | <50 | M | I–II | + | − | Yes | ≥400 | Yes | Yes | Multi | ≥5 |

| 30 | − | + | + | − | <50 | M | III–IV | + | − | Yes | ≥400 | Yes | Yes | Multi | ≥5 |

| 31 | − | + | + | − | ≥50 | M | I–II | + | − | Yes | ≥400 | Yes | Yes | Multi | ≥5 |

| 32 | − | + | + | − | <50 | M | I–II | + | − | Yes | ≥400 | Yes | Yes | Multi | ≥5 |

| 33 | − | + | − | − | ≥50 | M | III–IV | + | − | Yes | ≥400 | Yes | Yes | Multi | ≥5 |

| 34 | − | + | − | − | <50 | M | III–IV | + | − | Yes | <400 | Yes | Yes | Single | ≥5 |

| 35 | − | + | − | − | ≥50 | M | III–IV | + | − | Yes | <400 | Yes | Yes | Multi | ≥5 |

There were 2 cases of positive HCV, 1 with positive HBV (no. 27), and 1 with negative HBV (no. 26). Four cases were “non-B, non-C” cases (nos. 1, 4, 5, 17)

+, positive; −, negative

Relationship between methylation of the RASSF1A and clinicopathological parameters of HCC

Age, gender, pathological grade, HBV, HCV, paracirrhosis, AFP, portal vein tumor embolus, tumor capsular, tumor nodes amount, and tumor size of the 35 patients with methylation status of RASSF1A are illustrated in Tables 2 and 3. There was no association between serum and tissues DNA RASSF1A methylation and clinicopathological parameters.

Correlation between RASSF1A expression and the methylation of the RASSF1A

Among 35 liver tissues, 13 cases (37.14%) expressed RASSF1A protein. There were negative correlations between the expression of RASSF1A protein in the cancer tissues and the RASSF1A promoter methylation in serum (r = −0.628, p = 0.000) and in cancer tissues (r = −0.525, p = 0.002).

Discussion

Compared to collecting tumor biopsies, the TMA is a new technique with numerous advantages including speeding up the analysis, reducing time and reagents required, enhancing high laboratory efficiency, and gaining experimental uniformity. Many studies have demonstrated that TMA is very powerful in pathological and clinicopathological oncology research fields [24–27]. We employed 3 TMAs consisting of 96 samples from HCC, 24 samples from paracancerous, and 85 noncancerous liver tissues to detect the expression of RASSF1A which reflected the advantages of TMA.

Our results showed that absent or weak RASSF1A signals could be detected in tumor cells, and moderate to strong RASSF1A immunostaining was localized within the cytoplasm of normal, cirrhotic, and paracancerous liver sections. Nevertheless, to our knowledge, no study of reduced expression of RASSF1A in HCC by IHC and TMA has been reported. Our study showed that the positive immunostaining rate of RASSF1A was abnormally lower in HCC than in the paracancerous, cirrhotic, and normal liver tissue. The results demonstrate that the loss of RASSF1A could be involved in hepatocarcinogenesis and also provide better understanding of the pathogenesis and permit more accurate diagnosis of HCC. So the findings in the present study demonstrated that reduced RASSF1A protein could take part in hepatocellular carcinogenesis and suggested its possible role as a biomarker for the early diagnoses of HCC.

To our knowledge, this is the first study of immunohistochemically investigating a possible relationship between RASSF1A protein level and clinicopathological parameters of patients in HCC. So another interesting observation in the present study was that the loss of expression of RASSF1A directly correlated with clinical and pathological features. Only 2 of 41 patients (4.88%) with metastasis and recurrence had positive RASSF1A protein expression, whereas 28 of 44 patients (63.64%) without metastasis and recurrence had positive RASSF1A expression, revealing an obvious relationship between RASSF1A and metastasis and recurrence of HCC. In the current study, RASSF1A expression was associated with TNM stages of HCC: in the later TNM stage, the positive RASSF1A expression appeared weaker, which was consistent with the data from Tezval et al. [4] in renal cell carcinoma. Moreover, the reduced RASSF1A expression was directly correlated with the AFP level, portal vein tumor emboli, capsular infiltration, and tumor nodes. Generally, the portal vein tumor emboli, capsular infiltration, and the number of the tumor nodes reflect tumor growth. The present results further suggested that the reduced expression of RASSF1A was positively correlated with the higher frequency of tumor progression and postoperative metastasis and recurrence, that is, to provide a strong clinical support for the prometastatic function of RASSF1A. Xue et al. [28] reported the wt-RASSF1A expression in the QGY-7703 cell line resulted in fewer and smaller clones, decreased xenograft tumor volume and weight, and G(1)/S arrest in vitro and in vivo. In addition, the wt-RASSF1A expression increased cell growth inhibition and the percentage of cells with sub-G1 DNA content when the cells were treated with mitomycin. Hence, our analysis, being confirmatory of previous work, further supports the hypothesis that RASSF1A could be involved in progression of a substantial part of HCC.

Promoter hypermethylation has been found to frequently occur in tumor suppressor and cancer genes involved in many different signaling pathways and to be present in a different pattern in different tumor types [29]. Some antitumor gene expressions due to the methylation of gene promoter regions play an important role in the carcinogenesis of HCC [20]. The expression of the longer isoform, RASSF1A, is lost in many tumor lines and primary tumors by promoter methylation. It has been suggested that RASSF1A methylation is one of the most common aberrations so far identified in human cancers and that the loss of the functional protein may promote the development of many human tumors. Hypermethylation of the RASSF1A has been detected frequently in the tissues of different cancers [10–17], while in the body fluid, methylation of RASSF1A promoter has also been documented in 50% sputum and 84% serum from lung cancer [30], 35% urine from bladder cancer [15], 56–60% serum from breast caner [31–33], and 5% serum from undifferentiated nasopharyngeal carcinoma [34], which indicated the value of RASSF1A methylation in DNA for the early-stage diagnosis of tumors. Detection of methylated DNA has then been suggested as a potential biomarker for early detection of cancer. In this study, HCC tumor tissues demonstrated hypermethylation in RASSF1A gene (88.6%, 31/35) and sera (40%, 14/35), which is in concordance with the findings from other investigators (tissue 60–92.5%; serum 42.5–70%) [18–23]. Although the exact mechanism of how the tumor DNA enters systemic circulation is unclear, the present result can still suggest that RASSF1A methylation should be a potential marker of incipient malignancy in the human hepatocarcinogenesis since, like any ideal biomarker, it appears early in the course of disease and is detectable in biological samples that can be obtained noninvasively.

Although it may be expected that the presence of promoter methylation in DNA is associated with more advanced disease, previous studies on promoter methylation of RASSF1A in blood and tissues have not shown any correlation with tumor staging, except Yeo et al. [18], who reported that the promoter methylation of RASSF1A in the serum DNA of HCC was correlated to the tumor size. The author drew a conclusion that the bigger tumor gained better chance to undergo hypermethylation. In the present study, contrary to expectation, no association was found between the HCC tissue or serum RASSF1A methylation and any of the clinicopathological parameters. Different samples and different number of the patients can partly explain this difference.

It is known that the loss of RASSF1A expression is frequently caused by promoter hypermethylation in many cancers, including HCCs. This relation was present in the second part of our samples. The expression of RASSF1A protein in the cancer tissues was negative related to the RASSF1A promoter methylation in serum (r = −0.628, p = 0.000) and also in cancer tissues (r = −0.525, p = 0.002).

The prognosis of patients with HCC has marginally improved over the last two decades, but the 5-year survival rate is still not optimistic [1, 2]. This dismal result is in part due to the fact that diagnosis is frequently made at an advanced tumor stage precluding effective treatment. Therefore, most gastroenterologists routinely offer at-risk patients HCC surveillance programs on the basis of ultrasonography (US) with or without AFP measurement [31], which can detect most tumors at a stage still suitable for treatment [35]. To date, AFP is the only generally accepted serum marker for HCC. However, given its low positive predictive value, it is limited in a population at average risk [36]. RASSF1A could serve as a noninvasive index to monitor the regression or progression of cancer because of its dramatically decreasing serum level.

In conclusion, our study demonstrates that reduced RASSF1A protein expression and hypermethylation play important roles in the hepatocarcinogenesis of HCC. Furthermore, reduced RASSF1A protein expression has an obvious relationship with the development and aggressiveness of HCC. RASSF1A protein expression and methylation are negatively related, and they could be valuable for clinical prognosis prediction and curative effects in HCC. Especially, the detection of RASSF1A methylation in serum can be a tool for early screening for HCC. In addition, RASSF1A could also be an attractive target for the development of future HCC gene therapy.

Acknowledgments

This work was performed in People’s Republic of China. The study was supported by Medical Major Scientific Research Foundation of Guangxi (Zhong200513). The authors thank Dr. Ping Li for her immunodetection work and Meinhart Francois from Belgium for his useful suggestions in the manuscript preparation.

Footnotes

L. Hu and G. Chen contributed equally to this work.

Contributor Information

Lang Hu, Email: hulang2000060@sina.com.

Gang Chen, Email: chen_gang_triones@163.com.

Hongping Yu, Email: YHP268@163.com.

Xiaoqiang Qiu, Phone: +86-13669406819, Email: starsstars1204@hotmail.com.

References

- 1.Orito E, Mizokami M. Differences of HBV genotypes and hepatocellular carcinoma in Asian countries. Hepatol Res. 2007;37:S33–S35. doi: 10.1111/j.1872-034X.2007.00101.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nagai H, Sumino Y. Therapeutic strategy of advanced hepatocellular carcinoma by using combined intra-arterial chemotherapy. Recent Pat Anticancer Drug Discov. 2008;3:220–226. doi: 10.2174/157489208786242296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dammann R, Li C, Yoon JH, Chin PL, Bates S, Pfeifer GP. Epigenetic inactivation of a RAS association domain family protein from the lung tumour suppressor locus 3p21.3. Nat Genet. 2000;25:315–319. doi: 10.1038/77083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tezval H, Merseburger AS, Matuschek I, Machtens S, Kuczyk MA, Serth J. RASSF1A protein expression and correlation with clinicopathological parameters in renal cell carcinoma. BMC Urol. 2008;8:12. doi: 10.1186/1471-2490-8-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ghosh S, Ghosh A, Maiti GP, Alam N, Roy A, Roy B, et al. Alterations of 3p21.31 tumor suppressor genes in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma: correlation with progression and prognosis. Int J Cancer. 2008;123:2594–2604. doi: 10.1002/ijc.23834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lee JS, Fackler MJ, Teo WW, Lee JH, Choi C, Park MH, et al. Quantitative promoter hypermethylation profiles of ductal carcinoma in situ in North American and Korean women: potential applications for diagnosis. Cancer Biol Ther. 2008;7:1398–1406. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-08-0192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pallarés J, Velasco A, Eritja N, Santacana M, Dolcet X, Cuatrecasas M, et al. Promoter hypermethylation and reduced expression of RASSF1A are frequent molecular alterations of endometrial carcinoma. Mod Pathol. 2008;21:691–699. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.2008.38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lo PH, Xie D, Chan KC, Xu FP, Kuzmin I, Lerman MI, et al. Reduced expression of RASSF1A in esophageal and nasopharyngeal carcinomas significantly correlates with tumor stage. Cancer Lett. 2007;257:199–205. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2007.07.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ye M, Xia B, Guo Q, Zhou F, Zhang X. Association of diminished expression of RASSF1A with promoter methylation in primary gastric cancer from patients of central China. BMC Cancer. 2007;7:120. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-7-120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sung JS, Han SG, Whang YM, Shin ES, Lee JW, Lee HJ, et al. Putative association of the single nucleotide polymorphisms in RASSF1A promoter with Korean lung cancer. Lung Cancer. 2008;61:301–308. doi: 10.1016/j.lungcan.2008.01.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kee SK, Lee JY, Kim MJ, Lee SM, Jung YW, Kim YJ, et al. Hypermethylation of the Ras association domain family 1A (RASSF1A) gene in gallbladder cancer. Mol Cells. 2007;24:364–371. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Li Y, Wei Q, Cao F, Cao X. Expression and promoter hypermethylation of the RASSF1A gene in sporadic breast cancers in Chinese women. Oncol Rep. 2008;19:1149–1153. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Peters I, Vaske B, Albrecht K, Kuczyk MA, Jonas U, Serth J. Adiposity and age are statistically related to enhanced RASSF1A tumor suppressor gene promoter hypermethylation in normal autopsy kidney tissue. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2007;16:2526–2532. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-07-0203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jagadeesh S, Sinha S, Pal BC, Bhattacharya S, Banerjee PP. Mahanine reverses an epigenetically silenced tumor suppressor gene RASSF1A in human prostate cancer cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2007;362:212–217. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2007.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hu J, Li H, Shi T, Ma X, Wang B, Xu H, et al. Relationship between the expression of RASSF1A protein and promoter hypermethylation of RASSF1A gene in bladder tumor. J Huazhong Univ Sci Technol Med Sci. 2008;28:182–184. doi: 10.1007/s11596-008-0217-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chen YJ, Tang QB, Zou SQ. Inactivation of RASSF1A, the tumor suppressor gene at 3p21.3 in extrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma. World J Gastroenterol. 2005;11:1333–1338. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v11.i9.1333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wang YC, Yu ZH, Liu C, Xu LZ, Yu W, Lu J, et al. Detection of RASSF1A promoter hypermethylation in plasma from gastric and colorectal adenocarcinoma patients. World J Gastroenterol. 2008;14:3074–3080. doi: 10.3748/wjg.14.3074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yeo W, Wong N, Wong WL, Lai PB, Zhong S, Johnson PJ. High frequency of promoter hypermethylation of RASSF1A in tumor and serum of patients with hepatocellular carcinoma. Liver Int. 2005;25:266–272. doi: 10.1111/j.1478-3231.2005.01084.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zhang YJ, Wu HC, Shen J, Ahsan H, Tsai WY, Yang HI, et al. Predicting hepatocellular carcinoma by detection of aberrant promoter hypermethylation in serum DNA. Clin Cancer Res. 2007;13:2378–2384. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-06-1900. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zhang C, Li Z, Cheng Y, Jia F, Li R, Wu M, et al. CpG island methylator phenotype association with elevated serum alpha-fetoprotein level in hepatocellular carcinoma. Clin Cancer Res. 2007;13:944–952. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-06-2268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Di Gioia S, Bianchi P, Destro A, Grizzi F, Malesci A, Laghi L, et al. Quantitative evaluation of RASSF1A methylation in the non-lesional, regenerative and neoplastic liver. BMC Cancer. 2006;6:89. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-6-89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tischoff I, Markwarth A, Witzigmann H, Uhlmann D, Hauss J, Mirmohammadsadegh A, et al. Allele loss and epigenetic inactivation of 3p21.3 in malignant liver tumors. Int J Cancer. 2005;115:684–689. doi: 10.1002/ijc.20944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Schagdarsurengin U, Wilkens L, Steinemann D, Flemming P, Kreipe HH, Pfeifer GP, et al. Frequent epigenetic inactivation of the RASSF1A gene in hepatocellular carcinoma. Oncogene. 2003;22:1866–1871. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1206338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kononen J, Bubendorf L, Kallioniemi A, Bärlund M, Schraml P, Leighton S, et al. Tissue microarrays for high-throughput molecular profiling of tumor specimens. Nat Med. 1998;4:844–847. doi: 10.1038/nm0798-844. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Brennan DJ, Kelly C, Rexhepaj E, Dervan PA, Duffy MJ, Gallagher WM. Contribution of DNA and tissue microarray technology to the identification and validation of biomarkers and personalised medicine in breast cancer. Cancer Genomics Proteomics. 2007;4:121–134. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lemmer ER, Friedman SL, Llovet JM. Molecular diagnosis of chronic liver disease and hepatocellular carcinoma: the potential of gene expression profiling. Semin Liver Dis. 2006;26:373–384. doi: 10.1055/s-2006-951604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ko SS, Na YS, Yoon CS, Park JY, Kim HS, Hur MH, et al. The significance of c-erbB-2 overexpression and p53 expression in patients with axillary lymph node-negative breast cancer: a tissue microarray study. Int J Surg Pathol. 2007;15:98–109. doi: 10.1177/1066896906299124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Xue WJ, Li C, Zhou XJ, Guan HG, Qin L, Li P, et al. RASSF1A expression inhibits the growth of hepatocellular carcinoma from Qidong County. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2008;23:1448–1458. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.2007.05067.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kwong J, Lo KW, To KF, Teo PM, Johnson PJ, Huang DP. Promoter hypermethylation of multiple genes in nasopharyngeal carcinoma. Clin Cancer Res. 2002;8:131–137. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hsu HS, Chen TP, Hung CH, Wen CK, Lin RK, Lee HC, et al. Characterization of a multiple epigenetic marker panel for lung cancer detection and risk assessment in serum. Cancer. 2007;110:2019–2026. doi: 10.1002/cncr.23001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chan MW, Chan LW, Tang NL, Lo KW, Tong JH, Chan AW, et al. Frequent hypermethylation of promoter region of RASSF1A in tumor tissues and voided urine of urinary bladder cancer patients. Int J Cancer. 2003;104:611–616. doi: 10.1002/ijc.10971. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Dulaimi E, Hillinck J, Ibanez de Caceres I, Al-Saleem T, Cairns P. Tumor suppressor gene promoter hypermethylation in serum of breast cancer patients. Clin Cancer Res. 2004;10:6189–6193. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-04-0597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Shukla S, Mirza S, Sharma G, Parshad R, Gupta SD, Ralhan R. Detection of RASSF1A and RARbeta hypermethylation in serum DNA from breast cancer patients. Epigenetics. 2006;1:88–93. doi: 10.4161/epi.1.2.2679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wong TS, Kwong DL, Sham JS, Wei WI, Kwong YL, Yuen AP. Quantitative serum hypermethylated DNA markers of undifferentiated nasopharyngeal carcinoma. Clin Cancer Res. 2004;10:2401–2406. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-03-0139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bolondi L. Screening for hepatocellular carcinoma in cirrhosis. J Hepatol. 2003;39:1076–1084. doi: 10.1016/S0168-8278(03)00349-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sherman M. Alphafetoprotein: an obituary. J Hepatol. 2001;34:603–605. doi: 10.1016/S0168-8278(01)00025-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]