Abstract

Purpose

Patients with liver cirrhosis are generally considered to be “auto-anticoagulated” because of coagulopathy and thrombocytopenia. However, deep vein thrombosis (DVT) has been reported in patients with liver cirrhosis. The objectives of this study were to know the prevalence of DVT among cirrhotic patients and to compare clinical pictures between cirrhotic patients with and without DVT.

Methods

A case–control study was performed on the basis of medical record data of patients with liver cirrhosis admitted between August 2004 and July 2007 in Medistra hospital in Jakarta. Diagnosis of DVT was established by duplex Doppler ultrasonography of the lower extremities. Patients with splanchnic thrombosis were excluded from this study. Diagnosis of liver cirrhosis was based on history and clinical manifestation, consistent with liver cirrhosis and confirmed by ultrasonography or computed tomography.

Results

A total of 256 patients with liver cirrhosis were included in this study; 164 (64.1%) among them were men. Patients’ mean age was 60.5 ± 12.5 years, ranging from 16 to 88 years. Viral hepatitis accounted for 74.6% of patients with liver cirrhosis. DVT was found in 12 (4.7%) patients. There was no significant laboratory difference between cirrhotic patients with and without DVT (serum albumin, platelet count, aminotransferases, γ-glutamyl transpeptidase, alkaline phosphatase, total bilirubin levels, and prothrombin time). Diabetes mellitus was significantly higher in the DVT group than that in the control group (66.6 vs. 34.0%, P = 0.025). Multivariate analysis confirmed diabetes mellitus as an independent risk factor for the occurrence of DVT (odds ratio = 4.26; 95% confidence interval = 1.206–15.034; P = 0.024).

Conclusions

The prevalence of DVT in patients with liver cirrhosis was 4.7%, and Deep vein thrombosis is not a rare condition in cirrhotic patients with coagulopathy and warrants further studies on the mechanisms and prevention.

Keywords: DVT, Liver cirrhosis, Autoanticoagulated, Coagulopathy

Background

Deep vein thrombosis (DVT) is a serious disorder that often complicates the course of hospitalized patients. Rudolf Virchow first proposed that thrombosis was the result of at least one of three underlying etiologic factors (i.e., vascular endothelial damage, stasis of blood flow, and hypercoagulability) [1]. Many risk factors have been linked to the occurrence of venous thromboembolism (VTE) in the medically ill patients including increasing age, acute respiratory failure, congestive heart failure, cancer, acute infection, dehydration, rheumatologic disease, etc. [2, 3].

Until recently, there has been no report classifying liver cirrhosis or advanced liver disease as a risk factor of thrombosis. Since most of the coagulation factors and natural anticoagulants are synthesized in the liver, there is a general assumption that patients with advanced liver disease or cirrhosis are considered “auto-anticoagulated” because of low coagulation factors levels. In addition to decreased synthesis of coagulation factors, liver disease also presents with a complex and multifactor pattern of defects of hemostatic function, including abnormal protein synthesis such as dysfibrinogen, deficiency of natural anticoagulants, enhanced fibrinolytic activity, quantitative and qualitative platelet defects, and consumptive coagulopathy [4, 5].

Despite this coagulation dysfunction, DVT could still occur in patients with liver cirrhosis. The first study on hypercoagulation in cirrhotic patients reported that approximately 0.5% of all admissions resulted in a new diagnosis of a VTE event, which consisted of 65.5% DVT, 19.5% pulmonary embolism (PE), and 15% both [6]. The mechanisms of thrombosis are not clear and no other report has studied this phenomenon in more detail. This study was proposed to find out the prevalence of DVT in patients with liver cirrhosis and to compare clinical features of cirrhotic patients with and without DVT.

Patients and methods

Study design and subjects

This was an analytical cross-sectional study based on the medical record data of patients with liver cirrhosis, admitted to Medistra Hospital between August 2004 and July 2007. All patients with liver cirrhosis during the study period were included. Diagnosis of liver cirrhosis was based on the patients’ history, clinical manifestations of chronic liver disease consistent with liver cirrhosis, and imaging findings by liver ultrasonography or computed tomography.

Diagnosis of DVT

Patients with liver cirrhosis were not routinely screened for blood coagulation profile. Patients were assessed for the presence of DVT if they presented with clinical symptoms of DVT (i.e., unilateral swollen or painful leg).

Deep vein thrombosis was detected using Duplex Doppler ultrasonography of the veins system in the lower extremity (Pro Logic 500; General Electric, Milwaukee, WI, USA). The Duplex Doppler ultrasonographic criteria for DVT are as follows: no flow signal, direct clot visualization, the absence of spontaneous flow, and the absence of respiration-modulated phasicity of the evaluated veins. The valvular competency can be assessed using the Valsalva maneuver or manual compression. Late changes after DVT include not only incompetent, damaged valves but also persistently organized clot and venous contraction with the administration of echogenic material. There might be a partial recanalization of the diseased veins with wall thickening and the presence of collateral veins. Patients with splanchnic thrombosis (splenic, portal vein, and mesenteric thrombosis) were excluded from this study.

Statistical analyses

Characteristics of the study subjects were presented descriptively. The prevalence of DVT in cirrhosis was calculated from the total number of patients during the study period. Differences of clinical pictures and laboratory findings between patients with and without DVT were tested using chi-square test for nominal data and the Student t test for numerical data. A P value <0.05 was considered statistically significant. Analyses were performed using statistical software Stata, Version 9.0, for Windows PC (Stata Corporation, Texas, USA).

Results

During the study period, there were 256 patients admitted to the hospital with liver cirrhosis; 164 (64.1%) among them were men. Patients’ mean age was 60.5 ± 12.5 years, ranging from 16 to 88 years. Twelve patients (4.7%) developed DVT, which was identified clinically by a swollen calf with redness and tenderness and confirmed by Duplex Doppler ultrasonography (Figs. 1, 2, 3). All patients with DVT were treated with low-molecular-weight heparin and warfarin.

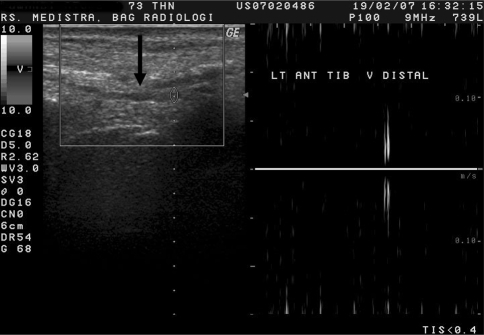

Fig. 1.

Longitudinal section of the distal part of left anterior tibial vein by Duplex Doppler ultrasonography. There is a hypoechoic structure inside (straight arrow) indicating a mild dilated vein and loss of vein compressibility and lack of flow signal

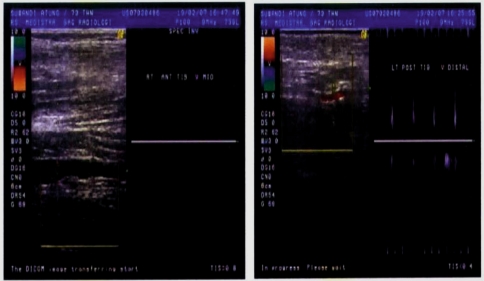

Fig. 2.

Longitudinal section of the distal part of right anterior tibial vein

Fig. 3.

Doppler ultrasonography of a cirrhotic patient with deep vein thrombosis

Viral hepatitis accounted for more than 70% of patients with liver cirrhosis. Half of the patients presented with ascites on admission, whereas hepatic encephalopathy was found in about 14.5% cases (Table 1). Bivariate analysis showed that the number of patients with diabetes mellitus was significantly higher in the DVT group than that in the control group. There was also a tendency that the number of patients having lower serum albumin level (i.e. <3 mg/dL) was significantly higher than that in the DVT group (Table 1). The presence of ascites and hepatic encephalopathy, which indicates disease severity, did not significantly differ between both groups of patients. The percentage of patients with hepatocellular carcinoma was similar in both groups. No other malignancy was found in these patients. No significant difference of laboratory parameters was found (i.e., serum liver enzymes, total bilirubin, albumin level, platelets count, and prothrombin time) between the two groups (Table 2).

Table 1.

Clinical characteristics of cirrhotic patients with and without DVT

| Characteristic | DVT (+) | DVT (−) | Total | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | ||||

| Male | 7 (53.8) | 157 (64.3) | 164 (64.1) | 0.672a |

| Female | 5 (41.7) | 87 (35.7) | 92 (35.9) | |

| Age group | ||||

| ≤50 years | 1 (8.3) | 53 (21.7) | 54 (21.1) | 0.267a |

| >50 years | 11 (91.7) | 191 (78.3) | 202 (78.9) | |

| Etiology | ||||

| Hepatitis B | 5 (41.7) | 97 (39.8) | 102 (39.8) | |

| Hepatitis C | 6 (50.0) | 83 (34.0) | 99 (34.8) | |

| Alcohol | 0 | 3 (1.23) | 3 (1.17) | |

| NASH | 0 | 3 (1.23) | 3 (1.17) | |

| Unknown | 1 (8.3) | 58 (23.8) | 59(23.0) | |

| Etiology group | ||||

| Viral | 11 (91.7) | 180 (73.8) | 191 (74.6) | 0.164a |

| Nonviral | 1 (8.3) | 64 (26.2) | 65 (25.4) | |

| Ascites | ||||

| Yes | 6 (50.0) | 123 (50.4) | 129 (50.4) | 0.978b |

| No | 6 (50.0) | 121 (49.6) | 127 (49.6) | |

| Encephalopathy | ||||

| Yes | 3 (25.0) | 34 (13.9) | 37 (14.5) | 0.280a |

| No | 9 (75.0) | 210 (86.1) | 219 (85.6) | |

| Serum albumin | ||||

| ≥3 mg/dL | 3 (25.0) | 124 (50.8) | 127 (49.6) | 0.081b |

| <3 mg/dL | 9 (75.0) | 120 (49.2) | 129 (50.4) | |

| Diabetes mellitus | ||||

| Yes | 8 (66.6) | 83 (34.0) | 91 (35.6) | 0.025a |

| No | 4 (33.3) | 161 (66.0) | 165 (64.5) | |

| Hepatocellular carcinoma | ||||

| Yes | 4 (33.3) | 83 (34.0) | 87 (34.0) | 0.614a |

| No | 8 (66.7) | 161 (66.0) | 169 (66.0) | |

aFisher’s exact test

bChi-square test

Table 2.

Laboratory values of cirrhotic patients with and without deep vein thrombosis (DVT)

| Characteristic | Cirrhotic patients with DVT | Cirrhotic patients without DVT | P (Student t test) |

|---|---|---|---|

| N | 12 | 244 | |

| Age (mean ± SD) | 61.4 ± 9.82 | 60.4 ± 12.64 | 0.788 |

| Aspartate aminotransferase (IU/L) | 73.0 ± 47.38 | 99.7 ± 126.10 | 0.466 |

| Alanine aminotransferase (IU/L) | 36.5 ± 14.80 | 54.8 ± 60.25 | 0.295 |

| γ-Glutamyl transpeptidase (IU/L) | 102.2 ± 113.25 | 124.3 ± 135.05 | 0.577 |

| Alkaline phosphatase (IU/L) | 158.1 ± 179.66 | 140.7 ± 106.56 | 0.597 |

| Albumin (g/dL) | 2.8 ± 0.57 | 3.0 ± 0.57 | 0.297 |

| Total bilirubin (mg/dL) | 7.8 ± 10.01 | 5.3 ± 7.89 | 0.540 |

| Platelet count (/μL) | 131.5 ± 66.70 | 147.9 ± 91.48 | 0.244 |

| Prothrombin time (seconds) | 18.74 ± 8.07 | 17.7 ± 6.71 | 0.615 |

Several clinical variables, such as sex, age group, etiology, albumin level, diabetes mellitus, and hepatocellular carcinoma, were further tested using logistic regression analysis. Other risk factors, such as smoking, obesity, dyslipidemia, or inherited hypercoagulable states, were not known. Viral etiology was higher in the group of cirrhotic patients with DVT, but it failed to reach statistical significance. Diabetes mellitus was the only variable that was significantly associated with the presence of DVT (Table 3). Subsequent multivariate analysis confirmed diabetes mellitus as an independent risk factor for developing DVT in patients with liver cirrhosis with a high odds ratio. However, serum albumin level of less than 3 mg/dL tended to be a risk factor with a near-significant 95% confidence interval (Table 4).

Table 3.

Logistic regression analysis of risk factors of deep vein thrombosis in cirrhotic patients

| Risk factor | Odds ratio | 95% CI | P |

|---|---|---|---|

| Female sex | 1.289 | 0.397–3.183 | 0.673 |

| Age group >50 years | 3.052 | 0.385–24.180 | 0.291 |

| Etiology by viral infection | 3.911 | 0.495–30.899 | 0.196 |

| Albumin <3.0 mg/dL | 3.100 | 0.819–11.727 | 0.096 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 3.880 | 1.135–13.260 | 0.031 |

| Hepatocellular carcinoma | 0.176 | 0.022–1.389 | 0.099 |

Table 4.

Multivariate analysis of risk factors of deep vein thrombosis in cirrhotic patients

| Risk factor | Coefficient | SE-coefficient | Adjusted odds ratio | 95% CI | Pa |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Etiology by viral infection | 1.6930 | 1.0707 | 5.44 | 0.667–44,322 | 0.114 |

| Albumin <3.0 mg/dL | 1.1819 | 0.6954 | 3.26 | 0.834–12.742 | 0.089 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 1.4492 | 0.6435 | 4.26 | 1.206–15.034 | 0.024 |

| Hepatocellular carcinoma | −1.8699 | 1.0649 | 0.15 | 0.019–1.242 | 0.079 |

aWald statistics

Discussion

To our knowledge, this study is the second case–control study of DVT incidence in patients with liver cirrhosis. Venous thromboembolism is considered a very rare event in patients with liver cirrhosis, with unpredictable course and unclear mechanism. When comparing our results with the report by Northup et al. [6], we found that the incidence of DVT was higher in our series. This discrepancy might be due to different characteristics of our study populations. First, viral hepatitis was the predominant cause of cirrhosis in our study (74.6%) compared with alcoholic and nonalcoholic steatohepatitis in Northup’s study. Second, the presence of diabetes mellitus was high in our cases (35.6%). As we know, diabetes mellitus is a risk factor for the occurrence of DVT.

We did not find any association between the clinical factors, such as sex, age, and laboratory findings, with the presence of DVT in liver cirrhotic patients. No laboratory marker could be used as a predictor for prothrombotic state, including serum albumin level. Most of our patients came already with a low serum albumin level (i.e., less than the normal cutoff point of 3.5 mg/dL). This skewed data distribution could partly explain why serum albumin level failed to show significant association with the presence of DVT. Low albumin level may indicate an advanced liver disease in the majority of our study subjects. In addition, serum albumin level may be used as an indirect marker for the levels of other proteins produced by the liver [7–10]. There are other factors, such as protein C, protein S, and antithrombin III, that play roles as natural anticoagulants. During acute or chronic liver disease, their concentrations decrease concomitantly with other coagulation factors, but usually are not lower than 20% of normal. Decreased natural anticoagulants, therefore, could be another risk factor for developing DVT.

We identified diabetes mellitus as an independent risk factor for developing DVT. This observation was not surprising since the risk of VTE is increased in diabetic patients [11]. Other features of endocrinal disturbance, such as obesity and dyslipidemia, might be risk factors of DVT; however, a recent study concluded that symptoms of metabolic syndrome were not clinically important risk factors for VTE [12]. Further studies are needed to confirm whether metabolic abnormalities, especially those with hepatitis C infection, could be the risk factors of DVT in patients with liver cirrhosis.

There are many risk factors and conditions predisposing to VTE such as age above 40 years, cancer with or without chemotherapy, history of VTE, prolonged immobility (bed ridden or lower limb paralysis), surgery, trauma, obesity, smoking, and inherited hypercoagulable states (e.g., antithrombin deficiency, protein C and/or protein S deficiency, factor V Leiden, prothrombin gene mutation) [13]. Besides, decreased synthesis of the natural anticoagulants, hypercoagulation in liver disease, could also be related to poor flow and vasculopathy associated with a chronic inflammatory state. The potential disease state favoring DVT or PE in patients with liver cirrhosis could be an imbalance of clotting cascade favoring coagulation, immobility of end-stage liver disease, infection, and systemic inflammation [14]. Clinical pretest probability, developed by Wells et al. [15], stratified patients into low, moderate, and high risks of DVT. Among the major criteria, there are malignancy and recent bed riddance for more than 3 days as risk factors [15]. However, our study used medical record data and patients were not assessed for DVT risks at admission. Therefore, we could not rule out the possibility of other risk factors that might contribute to the presence of DVT in our patients.

Our study showed that nearly 80% of the patients were older than 50 years and most of them had chronic hepatitis infection. Patients with this profile often need hospitalization due to cirrhosis complications such as ascites and encephalopathy. Immobilization during hospital stay is known as a risk factor for venous thrombosis due to the stasis of blood flow in the venous system. Therefore, patients with cirrhosis may share the same risk factors of VTE as other hospitalized patients. However, we did not analyze the patients’ length of stay before the occurrence of DVT symptoms. Risk of thrombosis is suggested when the length of hospital stay is more than 4 days [16].

We also analyzed the presence of hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) and its association with DVT. Cancer per se is a known risk factor of thrombosis. However, the presence of HCC apparently was not a risk factor for developing DVT in our study subjects because HCC was found in about one-third of the patients in both groups. The risk of thrombosis in patients with cancer also increases with the use of chemotherapy, hormonal therapy, and indwelling central venous catheters and may increase by 4- to 6-folds [17]. In addition, the occurrence of VTE in asymptomatic patients may antedate the clinical diagnosis of cancer [18]. Therefore, patients with apparent idiopathic VTE could have a risk of occult malignancy and need to be screened for cancer [19, 20].

Thrombosis risk can also be associated with the insertion of central venous catheters. The thrombogenic surface of these catheters can activate platelets and serine proteases, such as factors XII and X. Gram-negative organisms may also infect central venous catheters and release bacterial mucopolysaccharides. These bacterial polysaccharides can activate factor XII, induce a platelet-release reaction, and cause sloughing of the endothelial cells; each of these activities increases the risk of thrombosis. Endotoxin also induces the release of tissue factor, tumor necrosis factor, and interleukin-1, which can incite thrombogenesis [21].

Our study had several limitations. First, the study was not designed prospectively. Second, this is the first study in our country and no preliminary data were available to properly design a cohort study. Consequently, variables were chosen from medical record data and therefore we did not record other factors that might confound our results such as the patients’ lifestyle (smoking habit, obesity) and the history of inherited coagulation disorders. Third, DVT was suspected if the patient presented with clinical symptoms suggestive of DVT and further confirmed by Doppler ultrasonography. We did not screen the patients’ blood coagulation profile and, consequently, we might have overlooked patients with subclinical DVT.

Conclusion

The prevalence of DVT in our patients with liver cirrhosis was 4.7%. This result showed that DVT is not a rare condition in cirrhosis. Diabetes mellitus was the only independent risk factor for developing DVT found in this study. The precise mechanisms of hypercoagulability in cirrhosis are not known and warrant further investigation.

References

- 1.Anderson FA, Spencer FA. Risk factors for venous thromboembolism. Circulation. 2003;107(Suppl I):9–16. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000078469.07362.E6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Alikhan R, Cohen AT, Combe S, et al. Risk factors for venous thromboembolism in hospitalized patients with acute medical illness: analysis of the MEDENOX Study. Arch Intern Med. 2004;164:963–968. doi: 10.1001/archinte.164.9.963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zakai NA, Wright J, Cushman M. Risk factors for venous thrombosis in medical inpatients: validation of a thrombosis risk score. J Thromb Haemost. 2004;2:2156–2161. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2004.00991.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bovill LG. Liver disease. In Goodnight SH, Hathaway WE, editors. Disorders of Haemostasis and Thrombosis, a Clinical Guide. New York: McGraw Hill; 2001. 226

- 5.Abeer Khalid AG, Gader A, Mohammed AG. The liver and the haemostatic system. Saudi J Gastroenterol. 2003;9:59–68. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Northup PG, McMahon MM, Ruhl AP, Altschuler SE, Volk-Bednarz A, Caldwell SH. Coagulopathy does not fully protect hospitalized cirrhosis patients from peripheral venous thromboembolism. Am J Gastroenterol. 2006;101:1524–1528. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2006.00588.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Senzolo M, Burra P, Cholongitas E, Burroughs AK. New insights into the coagulopathy of liver disease and liver transplantation. World J Gastroenterol. 2006;12:7725–7736. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v12.i48.7725. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Caldwell SH, Hoffman M, Lisman T, Macik G, Northup PG, Reddy KR, et al. Coagulation disorders and hemostasis in liver disease: pathophysiology and critical assessment of current management. Hepatology. 2006;44:1039–1046. doi: 10.1002/hep.21303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Protein C deficiency. In Goodnight SH, Hathaway WE, editors. Disorders of Haemostasis and Thrombosis, a Clinical Guide. New York: McGraw Hill; 2001. 369

- 10.Valla DC. Thrombosis and anticoagulation in liver disease. Hepatology. 2008;47:1384–1393. doi: 10.1002/hep.22192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Petrauskiene V, Falk M, Waernbaum I, Norberg M, Eriksson JW. The risk of venous thromboembolism is markedly elevated in patients with diabetes. Diabetologia. 2005;48:1017–1021. doi: 10.1007/s00125-005-1715-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ray JG, Lonn E, Yi Q, Rathe A, Sheridan P, Karon C, the HOPE-2 investigators Venous thromboembolism in association with features of the metabolic syndrome. Q J Med. 2007;100:679–684. doi: 10.1093/qjmed/hcm083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lee AYY. Management of thrombosis in cancer: primary prevention and secondary prophylaxis. Br J Haematol. 2004;128:291–302. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2004.05292.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Northup PG, Sundaram V, Fallon MB, Reddy KR, Balogun RA, Sanyal AJ, Coagulation in Liver Disease Group et al. Hypercoagulation and thrombophilia in liver disease. J Thromb Haemost. 2008;6:2–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2007.02772.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wells PS, Hirsh J, Anderson DR, Lensing AW, Foster G, Kearon C, et al. Accuracy of clinical assessment of deep-vein thrombosis. Lancet. 1995;345:1326–1330. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(95)92535-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cushman M. Epidemiology and risk factors for venous thrombosis. Semin Hematol. 2007;44:62–99. doi: 10.1053/j.seminhematol.2007.02.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Heit JA, Silverstein MD, Mohr DN, Petterson TM, O’Fallon WM, Melton LJ. Risk factors for deep vein thrombosis and pulmonary embolism: a population-based case–control study. Arch Int Med. 2000;160:809–815. doi: 10.1001/archinte.160.6.809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.White RH, Chew HK, Zhou H, Parikh-Patel A, Harris D, Harvey D, et al. Incidence of venous thromboembolism in the year before the diagnosis of cancer in 528, 693 adults. Arch Intern Med. 2005;165:1782–1787. doi: 10.1001/archinte.165.15.1782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Piccioli A, Aw Lensing, Prins MH, Falanga A, Scannapieco GL, Ieran M, SOMIT Investigators Group et al. Extensive screening for occult malignant disease in idiopathic venous thromboembolism: a prospective randomized clinical trial. J Thromb Haemost. 2004;2:884–889. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2004.00720.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sørensen HT. Cancer and subsequent risk of venous thromboembolism. J Thromb Haemost. 2006;4:527–528. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2006.01799.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bick RL. Cancer-associated thrombosis. N Engl J Med. 2003;349:109–111. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp030086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]