Abstract

Purpose

The purpose of the trial was to quantify and compare the efficacy of two different sequences of burst anti-tachycardia pacing (ATP) strategies for the termination of fast ventricular tachycardia.

Methods

The trial was prospective, multicenter, parallel and randomized, enrolling patients with an indication for implantable cardioverter-defibrillator implantation.

Results

From February 2004, 925 patients were randomized and followed-up for 12 months. Eight pulses ATP terminated 64% of episodes vs. 70% in the 15-pulse group (p = 0.504). Fifteen pulses proved significantly better in patients without a previous history of heart failure (p = 0.014) and in patients with LVEF ≥ 40% (p = 0.016). No significant differences between groups were observed with regard to syncope/near-syncope occurrence.

Conclusion

In the general population, 15-pulse ATP is as effective and safe as eight-pulse ATP. The efficacy of ATP on fast ventricular arrhythmias confirmed once more the striking importance of careful device programming in order to reduce painful shocks.

Keywords: Ventricular tachyarrhythmia, Implantable, Defibrillators, Pacing, Programming, Shock

Introduction

Implantable cardiac defibrillators (ICD) have been proven to be highly effective in reducing mortality in patients at risk of sudden cardiac arrest [1, 2]. However, this benefit entails some morbidities, mainly associated with the pain of shocks, both appropriate and inappropriate. Up to 25% of patients receiving multiple shocks report some anxiety or depression, and find it difficult to get used to living with an ICD [3–5].

The first review on the pathogenesis of arrhythmia formation, methods of electrical pacing, response of specific tachyarrhythmias to pacing and the clinical application of pacing to terminate and suppress tachyarrhythmias, date back to 1975. Zipes recognized the high potential of electrical pacing, especially in view of a technological development [6].

Later on, other studies compared shock therapy for ventricular tachycardia with pacing therapy and tried to evaluate different pacing strategies in terms of efficacy and safety [7, 8]. Many of the recent studies that have demonstrated painless effective and safe anti-tachycardia pacing (ATP) for fast ventricular tachycardias (FVTs), have used eight pulses at 88% coupling interval ATP as standard ICD programming to reduce the shocks and morbidity of ICD therapy [9–11].

ATP is highly effective for FVTs and allows pain-free treatment. However, some challenging questions remain. Regarding optimal ATP programming, the optimal number of beats to use in overdrive pacing to terminate a ventricular tachycardia has not yet been prospectively investigated in spontaneous FVTs. Furthermore, there may be significant differences in the efficacy of ATP sequences between primary and secondary prevention patients or in specific subgroups. In order to address these questions, a randomized, prospective study, called the ADVANCE-D (Atp DeliVery for PAiNless ICD ThErapy) trial, was developed in Europe.

Methods

ADVANCE-D was a prospective, multicenter, randomized, controlled, parallel, single-blind trial designed to compare the efficacy of two different ATP sequences (eight vs. 15 pulses) for the treatment of FVT (320–240 ms) in patients with Class I or IIA indication for ICD implantation. Details of the design have been previously reported [12].

In brief, following institutional review board acceptance of the protocol and registration of informed consent, a total of 925 patients with standard ICD indications were enrolled from February 2004 to April 2006 in 60 European centers. After randomization 1:1 to either eight or 15 ATP pulses at 88% of the tachycardia cycle length (stratified by center), patients were followed-up for 12 months.

Patients older than 18 years with standard ICD indications and implanted with a device with ATP delivery capabilities were included in the study; only ICD patients believed unlikely to have a substrate for stable monomorphic ventricular tachycardia (VT) susceptible to ATP (hypertrophic cardiomyopathy, long-QT syndrome, or Brugada syndrome) were excluded.

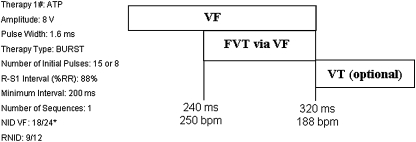

Device programming was standardized except for the initial randomized therapy for FVT (Fig. 1). Detection in the ventricular fibrillation (VF) zone required that 18 of the last 24 R–R intervals should have a cycle length (CL) <320 ms (>188 bpm). Only ICDs capable of programming a FVT detection zone defined within the VF zone (FVT via VF) for a CL of 240 to 320 ms (250 to 188 bpm) and ATP therapy available in this zone were used (Marquis VR mod. 7230, Marquis DR mod. 7274, Maximo VR mod. 7232, Maximo DR mod. 7278 Entrust DR mod.D153DRG, Entrust VR mod. D153VRG; all Medtronic Inc).

Fig. 1.

Detection intervals and therapy programming description

For the ICD model EnTrust, DR/VR programming of the ATP during charging feature had to be switched off until the end of the study.

Following enrolment, patients were randomized according to a web-based randomization scheme, and ICDs were programmed consequently. Follow-up examinations were performed at 3, 6, and 12 months, at which times clinical status and device performance were assessed. Whenever the patients had symptomatic episodes, an unscheduled follow-up examination was performed as soon as possible, preferably within three working days.

The stored electrogram was used to classify all spontaneous episodes. All arrhythmic events were adjudicated by an independent, blinded Episode Review Board (ERB). Each episode was reviewed by two different experts; in the case of disagreement, the episode was reviewed by the four ERB members in a plenary session.

Mortality and adverse events were also recorded. All adverse events, mortality and safety endpoints were adjudicated by an independent, blinded Adverse Event Committee.

The primary endpoint was to quantify and compare the efficacy of two different sequences of Burst ATP strategies for the termination of ventricular tachycardia (with CL of 240 ms-320 ms) from the baseline to 12 months post-randomization in patients treated with eight-pulse ATP at 88% versus patients treated with 15-pulse ATP at 88%.

Secondary endpoints pre-specified in the protocol were: (1) to estimate ATP efficacy in terminating FVT episodes in patients treated for primary and secondary prevention; (2) to estimate the rates of FVT acceleration and degeneration into VF (acceleration was defined as a decrease in FVT cycle length greater than 10% as recorded by the device); (3) to compare the likelihood of syncopal events associated with FVT (syncope was defined as transient, self-limiting loss of consciousness, usually leading to a fall); (4) to estimate the reduction in the number of shocks delivered for the treatment of spontaneous FVT; (5) to evaluate predictors of ATP success. All the secondary endpoints and sub analysis were pre-specified by protocol.

New York Heart Association (NYHA) class information was collected at the baseline only for patients with a history of heart failure.

Statistical analysis

Sample size calculation and its amendment are described in the ADVANCE-D design publication [12].

Continuous data were expressed as mean ± standard deviation, whereas categorical values were expressed as absolute and relative frequencies. Data were analyzed on an intention-to-treat basis. To adjust for multiple episodes per patient, the generalized estimating equations (GEE) method was used in quantification and comparison of therapy delivery, syncope, acceleration, and in episode duration unless otherwise noted [13].

Mortality rate was determined by Kaplan–Meier estimation and curves were compared by mean of the Log-rank test.

A population-averaged logistic regression, both univariate and multivariable, was applied in order to study predictors of efficacy. The multivariable model included all covariates with a significance below 0.1 on univariate analysis.

Summary statistics for episode measures such as CL were adjusted for multiple episodes per patient by calculating the median for each patient and then calculating summary statistics on the basis of each patient’s median.

Statistical analyses were performed by mean of SPSS 12.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, Illinois) and Stata SE9.0 (StataCorp, Texas, USA).

Results

Enrolment began in February 2004 and follow-up was completed by April 2007. We randomized 925 patients, 475 to the eight-pulse group and 450 to the 15-pulse group. Patients with a history of previous myocardial infarction, significant coronary lesions, or previous myocardial revascularization were considered to have coronary artery disease; these represented 74.7% of the patients (691 patients). Five hundred and forty-four patients (58.8%) underwent implantation for secondary prevention. Mean ejection fraction was 33.9 ± 12.1%. Baseline characteristics are reported in Table 1. No patient switched from one assigned ATP burst therapy to the other, or turned off ATP during the study owing to their physician’s decision (except in one patient during a hospitalization event). Mean follow-up was 12 ± 3 months.

Table 1.

Clinical characteristics of the study population

| All pts n = 925 | Group 8 n = 475 | Group 15 n = 450 | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Male gender, n (%) | 811 (87.7%) | 409 (86.1%) | 402 (89.3%) | 0.135 |

| Age, average (standard deviation) | 63.7 (11.6) | 64.0 (10.9) | 63.4 (12.2) | 0.412 |

| Secondary prevention | 544 (58.8%) | 272 (57.3%) | 272 (60.4%) | 0.326 |

| CAD, n (%) | 691 (74.7%) | 364 (76.6%) | 327 (72.7%) | 0.166 |

| HF, n (%) | 542 (58.6%) | 278 (58.6%) | 264 (58.9%) | 0.932 |

| Ejection fraction (%), average (SD) | 33.9 (12.1) | 33.7 (11.8) | 34.2 (12.4) | 0.532b |

| NYHA class, n (%) | 0.676 | |||

| I | 49 (9.4%) | 30 (11.2%) | 19 (7.6%) | |

| II | 309 (59.4%) | 154 (57.2%) | 155 (61.3%) | |

| III | 158 (30.4%) | 83 (30.9%) | 75 (29.9%) | |

| IV | 4 (0.8%) | 2 (0.7%) | 2 (0.8%) | |

| LBBB, n (%) | 163 (17.6%) | 92 (19.5%) | 71 (15.8%) | 0.144 |

| ACE inhibitors, n (%)a | 667 (74.9%) | 357 (78.5%) | 310 (71.3%) | 0.013 |

| Amiodarone, n (%)a | 238 (26.7%) | 123 (27.0%) | 115 (26.4%) | 0.841 |

| ARB II, n (%)a | 66 (7.4%) | 29 (6.4%) | 37 (8.5%) | 0.225 |

| Beta-blockers, n (%)a | 558 (62.7%) | 276 (60.7%) | 282 (64.8%) | 0.199 |

| Digitalis, n (%)a | 95 (10.7%) | 56 (12.3%) | 39 (9.0%) | 0.107 |

| Diuretics, n (%)a | 532 (59.8%) | 277 (60.9%) | 255 (58.6%) | 0.492 |

| Other AAD, n (%)a | 17 (1.9%) | 4 (0.9%) | 13 (3.0%) | 0.022 |

| Spironolactone, n (%)a | 279 (31.3%) | 152 (33.4%) | 127 (29.2%) | 0.176 |

AAD anti arrhythmic drug, CAD coronary artery disease, HF heart failure, LBBB left bundle branch block

aFisher’s exact test

bMann-Whitney non parametric test for independent groups

Detection of spontaneous episodes

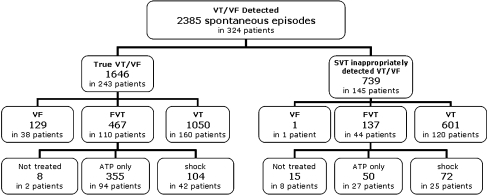

We collected 2,781 tachyarrhythmia episodes with complete electrogram data in 333 patients. Of these, 2,385 were classified as spontaneous episodes by the ERB: 1,646 in 243 patients were true VT/VF, whereas 739 episodes in 145 patients were true supraventricular tachyarrhythmia (SVT).

For the true VT/VF episodes, 129 (8%) in 38 patients were classified as VF, 467 (28%) in 110 patients were classified as FVT and 1050 (64%) in 160 patients were true VTs. Of the 467 FVT, eight episodes did not receive any ATP treatment (therapies were programmed off during a hospitalization event) and were excluded from the analysis (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

ERB adjudication of episodes detected by ICD as spontaneous ventricular tachyarrhythmia. Details on the treatments delivered for episodes appropriately and inappropriately detected in the FVT window are reported. Not treated episodes that did not received any treatment. ATP only episodes treated only by ATP. Shock episodes treated with at least one shock

Primary endpoint on therapy efficacy

There was no difference in median FVT CL between eight- and 15-pulse ATP (291 ms for eight pulses versus 290 ms for 15 pulses; p = 0.650).

The overall ATP efficacy in terminating FVT episodes was 71% when unadjusted and 67% when adjusted (95%CI 60–74%). After adjustment, 64% of episodes were terminated by eight-pulse ATP (95%CI 55–75%) versus 70% (95%CI 60–80%) in the 15-pulse group (p = 0.504).

Secondary endpoints

Predictors of ATP success in general population:

Univariate and multivariable analyses were performed on baseline clinical variables in order to determine their potential correlation with ATP success in the overall population. The independent significant predictors of ATP success identified were: NYHA functional class deterioration in HF patients (OR 0.52, 95% CI 0.29–0.95; p = 0.033) and the administration of ACE inhibitors (OR 3.33, 95% CI 1.51–7.36; p = 0.003). No other variables were predictive of ATP success.

The same analysis was performed dividing the population by randomization groups. Fifteen-pulse burst ATP was significantly better in patients without a previous history of heart failure (OR 5.21, 95%CI 1.39–19.50, p = 0.014) and in patients with left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) ≥ 40% (OR 5.97, 95%CI 1.39–25.62, p = 0.016).

Eight-pulse ATP was more effective in patients with previously reported heart failure, but only in those with NYHA functional class I–II (OR 0.38, 95%CI 0.16–0.91, p = 0.029).

ATP efficacy in primary and secondary prevention

FVT median cycle length was significantly longer in secondary prevention than in primary prevention patients (293 ms vs. 285 ms; p = 0.041).

As reported above, 58.8% of the patients were implanted for secondary prevention (57.3% in the eight-pulse group and 60.4% in the 15-pulse group). The adjusted efficacy (GEE) of ATP for primary prevention was 71.4% in the eight-pulse group and 69.1% in the 15-pulse group (p = 0.798); with regard to secondary prevention, the figures were 62.7% and 69.9% in the eight- and 15-pulse groups, respectively (p = 0.457). No significant differences were found either by group or by indication (p = 0.511 for the eight-pulse group and p = 0.900 for the 15-pulse group).

Univariate analyses were performed on baseline variables in order to determine their potential correlation with ATP success in primary and then in secondary prevention group.

In all the primary prevention patients, the 15-pulse and eight-pulse ATP burst had similar effectiveness.

In the secondary prevention group 15 pulses were significantly more effective in patients without a previous history of heart failure (OR 9.60, 95%CI 1.65–55.87, p = 0.012) and in patients with LVEF ≥ 40% (OR 5.05, 95%CI 1.17–21.73, p = 0.030). The same advantage of the 15-pulse burst was observed in patients without a previous history of NSVTs (OR 2.61 95%CI 1.07–6.37, p = 0.035).

Acceleration rate

FVT acceleration was observed only for 18 episodes (3.9%) in 13 patients: 3.9% in the eight-pulse group vs. 4% in the 15-pulse group (p = 0.993) as summarized in Table 2. Of these 18 episodes, 16 were terminated by shock, while two spontaneously terminated during battery charging. None of the accelerated episodes correlated with syncope or near-syncope.

Syncope occurrence rate

Table 2.

Safety data comparison

| All pts (108 pts) | 8 pulses (57 pts) | 15 pulses (51 pts) | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Syncope related to FVT (pts) | 5 (4.6%) | 1 (1.8%) | 4 (7.8%) | 0.186a |

| Syncope related to FVT (episodes) | 7 (1.7%) | 1 (0.5%) | 6 (3.2%) | 0.169 |

| Near-syncope related to FVT (pts) | 9 (8.3%) | 7 (12.3%) | 2 (3.9%) | 0.167a |

| Near-syncope related to FVT (episodes) | 9 (1.8%) | 7 (2.8%) | 2 (0.7%) | 0.046 |

| Syncope/Near-syncope related to FVT (pts) | 14 (13.0%) | 8 (14.0%) | 6 (11.8%) | 0.726 |

| Syncope/Near-syncope related to FVT (episodes) | 16 (3.6%) | 8 (3.2%) | 8 (4.1%) | 0.690 |

| Acceleration (pts) | 13 (11.5%) | 7 (11.5%) | 6 (11.5%) | 0.992 |

| Acceleration (episodes) | 18 (3.9%) | 10 (3.9%) | 8 (4.0%) | 0.993 |

Percentages regarding episodes were corrected by means of GEE analysis

FVT fast ventricular tachycardia

aFisher’s exact test

As summarized in Table 2, seven episodes of syncope (1.7%) and nine of near-syncope (1.8%) occurred in 14 patients; these were associated to a FVT episode. Syncope and near-syncope occurred in 0.5% and 2.8% of FVT episodes, respectively in the eight-pulse group and in 3.2% and a 0.7% in the 15-pulse group. We found no significant differences between groups with regard to syncope/near-syncope occurrence (p = 0.690).

Reduction in number of shocks

In the eight-pulse arm, 59 out of 250 FVT episodes (22%) required one or more shocks (total shocks 72). In the 15-pulse arm, 45 out of 209 FVT episodes (21%) required one or more shocks (total shocks 50). No significant differences were observed between groups (p = 0.907).

Considering only the inappropriately detected episodes in the FVT zone (raw numbers described in Fig. 2), the GEE adjusted rate of delivered shocks (number of shocks divided by the total number of inappropriately detected episodes) was not significantly different between the two groups (67.6% in the eight-pulse vs. 62.9% in the 15-pulse groups, p = 0.647).

Coronary artery disease (CAD) patients vs. non-CAD patients

Eight- and 15-pulse ATP had the same efficacy in treating FVT in CAD and non-CAD patients (eight-pulse efficacy: 63.2% in CAD patients and 69.9% in non-CAD patients; 15-pulse efficacy: 68.2% in CAD patients and 74.5% in non-CAD). There were no significant differences either between arms or between CAD and non-CAD patients (p values always >0.5).

Mortality

During the study, 57 deaths occurred (6.2%): 31 (6.5%) in the eight-pulse arm and 26 (5.8%) in the 15-pulse arm. Seven patients (0.8%) have been subjected to cardiac transplantation, two deaths were classified as sudden, 21 as non-sudden, ten non-cardiac and 17 unknown. No significant difference was found between the two randomization groups in terms of causes of death (all p values > 0.5) or overall mortality (Log-rank = 0.22; p = 0.636).

Discussion

The medical literature on the adverse psychological consequences of ICD shocks, whether appropriate or not, is growing.

The Painfree Rx I and Painfree Rx II studies found painless ATP to be safe and effective in treating monomorphic ventricular arrhythmias, showing a relative shock reduction of 70–92%, depending mainly on cycle length [14, 15]. Painfree Rx II involved 634 patients in 42 US centers; the first therapy in the FVT zone was a single ATP sequence of an eight-pulse burst-pacing train at 88% of the ventricular tachycardia (VT) cycle length (CL). On comparing ATP and shock therapy, no statistically significant differences were found in arrhythmia acceleration, syncope, or mortality. Additionally, after 12 months, the ATP arm showed a significant improvement in five of the eight subscales in the Medical Outcomes Study 36-item short-form General Health Survey (physical functioning, role physical, bodily pain, social functioning, and role emotional), as well as in the two summaries (mental and physical) [15].

Moreover, recently published studies report that both appropriate and inappropriate shocks are significant predictors of death. In the SCD-HeFT study, the risk of death among patients who received more than one appropriate shock was twice as high as among patients who received a single appropriate shock; furthermore, shocks were much stronger predictors of an adverse outcome in ischemic than in non-ischemic heart failure patients [16]. These results are similar to those obtained the Multicenter Automatic Defibrillator Implantation Trial II (MADIT II), which also showed that the risk of death increased by a factor of 3 after an appropriate ICD shock [17]. Thus, over treatment with shocks has an impact on both the mental and physical status of the patient, as well as reducing device longevity as a result of excessive battery drain.

The ADVANCE-D trial results showed that ATP therapy is highly effective and safe in treating fast ventricular tachyarrhythmia in general population. The results are confirmed in all the subgroups analyzed: ischemic, non-ischemic, primary, and secondary prevention patients. Concerning ATP success predictors, the administration of ACE inhibitors seems to improve ATP efficacy and in the HF population, the efficacy of ATP treatment is greater in less functionally compromised patients. These results may have been coincidental observation and will require further confirmation by means of a specific study.

Owing to the high efficacy of ATP and the consequent reduction in shocks, it may be claimed that ATP should always be programmed as a first-option electrical therapy for fast ventricular tachyarrhythmias.

These European data are in close agreement with those reported by the Painfree RxII study (which was run in the USA) with regard to episode distribution, therapy efficacy, safety, and mortality.

The importance and potential benefits of ICD shock reduction, by optimizing ATP therapy seem clear. Previous studies on the electrical treatment of fast ventricular tachycardia have examined several empirical ATP strategies, such as burst with different numbers of pulses or ramp with beat-to-beat decremented cycle length [8, 18], without obtaining clear proof of the best ATP programming. The ADVANCE-D study compared two different strategies of burst pacing in the general ICD population and in subgroups with specific baseline characteristics. The choice of the two therapies was prompted, on the one hand, by the Painfree experience of using eight pulses at 88% coupling interval (safety proved), and, on the other hand, by various smaller studies in which a different ATP strategy was used. Peinado et al. [8] tested the safety and efficacy of four different pacing sequences in 45 patients with spontaneous or induced monomorphic ventricular tachycardia (MVT). Each patient randomly received each ATP sequence at 3-month intervals. The different pacing modes were based on the number of beats (seven vs. 15) and coupling interval (91 vs. 81%). The success rate was significantly higher for 15 (78%) than for seven beats (68%) at a coupling interval of 91%, but no differences in termination were found when coupling intervals of 81% were used. Although the acceleration rate was higher with 15 pulses, this difference did not reach statistical significance. They concluded that the longer, but less aggressive ATP strategy was more effective and safer.

On the basis of this evidence, we selected 15-pulse ATP at 88% coupling interval, as an alternative to eight-pulse ATP in the hypothesis that a higher number of pulses would better penetrate into the arrhythmic circuit. We tried to minimize the chance of acceleration by using a coupling interval of proven safety. We proved that 15-pulse ATP is, in the general ICD population, as effective as the eight-pulse ATP and is equally safe. The study focused only on faster ventricular tachycardia episodes and did not allow any analysis of ICD patients with slower ventricular arrhythmias, in whom prolonged duration of ATP pulses might be more effective. This last hypothesis needs further evaluation.

The only significant difference in effectiveness was observed in the subgroup of patients without heart failure at the baseline or with an ejection fraction of 40% or higher. This specific subgroup was not included among the pre-specified analysis therefore the result reported should be validated by further randomized studies.

Overall, ADVANCE-D does not show strong evidence of the superiority of one specific ATP strategy. It does, however, definitively confirm the marked impact of ATP therapy on the majority of fast ventricular arrhythmias in ICD patients.

Conclusion

The results of the Painfree trials regarding the importance of shock reduction have, in recent years, raised a relevant clinical question as to the best programming of ATP therapies. Many hypotheses have emerged from the results of small studies in which different types of burst were investigated. These hypotheses demanded final clarification by means of a prospective, parallel, randomized trial. The ADVANCE-D trial fulfilled these requirements and demonstrated that 15-pulse ATP in the general population of ICD-indicated patients is as effective and safe as eight-pulse ATP. The efficacy of ATP on fast ventricular arrhythmias confirmed once more the striking importance of careful device programming, the first goal of which should be to reduce shocks.

Limitations

The study was performed using devices provided by a single manufacturer (Medtronic Inc.). The definition of FVT was determined as all the VT episodes with cycle length of 320–240 ms. The choice of the abovementioned window was made arbitrarily although inspired by previously published international trials [14, 15]. The final number of FVT episodes represented only the 28% of the overall number of arrhythmic episodes in 110 patients.

The pacing algorithm described in our paper was specifically focused on FVT only, although such scenario does not represent daily practice in which the devices are usually programmed using different strategies, with multiple ATP sequences and short-burst pacing, tailored on clinical needs.

One possible confounding factor in estimating ATP success is the possibility that ATP may appear to successfully treat VT that would have otherwise self-terminated. For the same reason, the shock rate reduction cannot be estimated based on the number of VT episodes terminated by ATP.

Acknowledgement

ADVANCE-D Investigators

Prof. M. Santini, Italy, Ospedale S. Filippo Neri, Roma

Dr. A. Kloppe, Germany, Klinikum Lüdenscheid, Lüdenscheid

Dr. A. Proclemer, Italy, Ospedale S. Maria della Misericordia, Udine

Dr. M. Lunati, Italy, Ospedale Niguarda Ca’ Granda, Milano

Dr. G. Molon, Italy, Ospedale Sacro Cuore Don Calabria, Negrar

Dr. J. Schäfer, Germany, Kliniken Essen Nordwest Philippusstift Krankenhaus, Essen

Dr. M. Marzegalli, Italy, Ospedale San Carlo Borromeo, Milano

Dr. P. Defaye, France, Hôpital Albert Michalon, Grenoble

Dr. CH. Reithmann, Germany, University Clinic München Großhadern

Dr. J.Martinez Ferrer, Spain, Hospital Txagorritxu, Vitoria

Dr. J. Mermi, Germany, Klinikum Dortmund, Dortmund

Dr. S. del Castillo, Spain, H. Germans Trias i Pujol, Badalona

Dr. B. Delarche, France, Centre Hospitalier de Pau, Pau

Dr. H.H. Ebert, Germany, Hospital Kardiologische Gemeinschaftspraxis, Riesa

Dr. A. Curnis, Italy, Spedali Civili, Brescia

Dr. L. Libero, Italy, Molinette, Torino

Dr. A. Garcia-Alberola, Spain, H. Virgen de la Arrixaca, Murcia

Prof. P. Mabo, France, Centre Hospitalier Universitaire de Rennes

Prof. E. Himmrich, Germany, Johannes Gutemberg Universitätsklinik, Mainz

Dr. T. Korte, Germany, Kliniken der Med. Hochschule, Hanover

Dr. M. Orlandi, Italy, Ospedale Maggiore, Lodi

Dr. J. Merino, Spain, Hospital La Paz, Madrid

Dr. G. Botto, Italy, Ospedale S. Anna, Como

Dr. M. Sabaté, Spain, Hospital De Bellvitge, Barcelona

Dr. A. Moya, Spain, Hospital Vall d’Hebrón, Barcelona

Dr. J. Boland, Belgium, CHR La Citadelle, Liège

Prof. E. Aliot, France, Hôpital Brabois, Nancy

Dr. E. Occhetta, Italy, Azienda Ospedaliera “Maggiore della Carità”, Novara

Dr. G. Senatore, Italy, Presidio Ospedaliero Riunito, Ciriè

Dr. J.A. García Robles, Spain, H. Gregorio Marañón, Madrid

Dr J.P. Faugier, France, Centre Hospitalier de la Durance, Avignon

Prof. J.M. Davy, France, Hôpital Arnaud de Villeneuve (Cardiologie B), Montpellier

Dr. D. Babuty, France, Hôpital Trousseau, Tours

Dr. J.O. Schwab, Germany, Hospital Rheinische Friedrich-Wilhelms Universität, Bonn

Dr. B. Hügl, Germany, Zentralklinik Bad Berka Kardiologie, Bad Berka

Dr. M. Steinmüller, Germany, Klinikum der Justus-Liebig-Universität, Gießen

Dr. M. Salvador, France, Hôpital Rangueil, Tolouse

Dr. M. Zardini, Italy, Cliniche Gavazzeni, Bergamo

Dr. A. Asso, Spain, H. Miguel Servet, Zaragoza

Dr. J. De Sousa, Portugal, Hospital Santa Maria, Lisbon

Dr. M. Nogueira da Silva, Portugal, Hospital Santa Marta, Lisbon

Dr. F. Leclercq, France, Hôpital Arnaud de Villeneuve (Cardiologie A), Montpellier

Dr. M. Disertori, Italy, Ospedale S. Chiara, Trento

Dr. R. Cappato, Italy, Ospedale San Donato, Milano

Dr. T. Lavergne, France, Hospital Européen George Pompidou, Dr Youven, Paris

Prof. B. Strasberg, Israel, Rabin Medical Center, Petach-Tikva

Dr. F. Mantovan, Italy, Presidio Ospedaliero Cà Foncello, Treviso

Dra. C. Expósito, Spain-H. Son Dureta, Mallorca

Dr. J. Ledesma Garcia, Spain, H. Universitario de Salamanca, Salamanca

Dr. E. Castellanos Martinez, Spain, H. Virgen de la Salud, Toledo

Dr. E. Rodriguez, Spain, Hospital de Sant Pau i de la Santa Creu, Barcelona

Dr. D. Flammang, France, Center d’Angoulême, Saint-Michel

Dr. P. Bru France, Centre Hospitalier, La Rochelle

Prof. J.P. Camous, France, CHU Hôpital Pasteur, Nice

Dr. K. Rybak, Germany, Kardiologische Praxis, Dessau

Prof. V. Calvi, Italy, AO Vittorio Emanuele Ferrarotto, S. Bambino, Catania

Dr. M. Ivaldi, Italy, Ospedale S. Spirito, Casale Monf.to

Dr. L. Tercedor, Spain, Hospital Virgen de las Nieves, Granada

Prof. J. Clementy, France, Hôpital Cardiologique, Bordeaux

Dr. P. Scanu, France, Hôpital Chu Caen, Caen

Dr. N. Elbaz, France, Hôpital Henri Mondor, Créteil

Dr. F. Briand, France, Hôpital Jean Minjoz, Besançon

Dr. A. Tamm, Germany, Kardiologische Praxis, Lutherstadt-Wittenberg

Dr. M. Glikson, Israel, Sheba Medical Center, Ramat-Gan

Dr. J. M. Porres, Spain, H. De Donosti, San Sebastián

Dr. J. Ormaetxe, Spain, Hospital de Basurto-Osakidetza, Bilbao

Dr. T. Betts, UK, John Radcliffe, Oxford

Dr. P. Blouard, Belgium, CHR Namur

Prof. B. France, CHRU du Morvan Hôpital de la Cavalle Blanche, Brest

Dr. D. Lamaison, France, CHU, Clermont, Ferrand

Dr. S. Dinanian, France, Hôpital Béclère, Clamart

Dr. S.V. Aharon Glick, Israel, Tel-Aviv Sourasky Medical Center

Dr. P. Zecchi, Italy, Policlinico A. Gemelli, Roma

Dr. F. Anselme, France, Hôpital Charles Nicolle, Rouen

Prof. J.C. Deharo, France, Hôpital de la Timone, Marseille

Dr. JF. Leclercq, France, Hôpital La Pitié Salpétrière, Paris

Dr. M. Boulus, Israel, Rambam Medical Center, Haifa

Dr. M. Tritto, Italy, Istituto Clinico Mater Domini, Castellanza (VA)

Dr. M. Bocchiardo, Italy, Ospedale Civile, Asti

Dr. C. Scavée, Belgium, UCL Saint-Luc

Dr. A. Leenhardt, France, Hôpital Lariboisière, Paris

Dr. A. Rötzer, Germany, Kliniken Ludwigsburg-Bietigheim, Ludwigsburg

Dr. F. Solimene, Italy, Casa di Cura Montevergine, Mercogliano

Dr. M. Gasparini, Italy, Istituto Clinico Humanitas, Milano

Dr. J.G. Martínez, Spain, Hospital General de Alicante, Alicante

Dr. M. Rodriguez, Spain, Hospital Lluis Alcanys, Xàtiva

Steering Committee members:

Italy:

Prof. Santini (Ospedale S. F. Neri, Roma), Dr. Lunati (Ospedale Niguarda, Milano), Dr. Cappato (Istituto Pol. S. Donato MI)

Spain:

Dr.Arenal (Hospital G. Marañón, Madrid), Dr. Merino (Hospital La Paz, Madrid), Dr. Garcia-Alberola (H. Virgen de la Arrixaca, Murcia)

Germany:

Dr. Mermi (Dortmund)

France:

Dr. Defaye (University Hospital, Grenoble)

Medtronic Spain:

Dr. X. Navarro

Adverse Events Committee members:

Dr. F. Cantù, Ospedali Riuniti, Bergamo, Italy

Dr. JF. Leclercq, Pitié-Salpetrière Hospital, Paris, France

Dr. J.A. García Robles, H. Gregorio Marañón, Madrid, Spain

Dr. M. Wiezcorek, Heart Center Duisburg, Center for Electrophysiology, Duisburg, Germany

Episode Review Committee members:

Dr. R. Brambilla, Istituto Auxologico Italiano, Milano, Italy

Prof. Dr. med. M. Hennersdorf, SLK-Kliniken Heilbronn GmbH, Heilbronn, Germany

Dr. C.Pignalberi, Ospedale San Giacomo, Roma; Italy

Dr. R. Ruiz Granell, Hospital Clinico, Valencia, Spain

Dr. L. Rebellato, Azienda Ospedaliera Santa Maria della Misericordia, Udine, Italy

Dr. C. Pedrinazzi, Azienda Ospedaliera Ospedale Maggiore, Crema, Italy

Study managers:

General Study Manager: Elisabetta Santi

Country Study Managers:

Italy: Laura Manotta, France: Aurelie Kajackas, Spain: Elvira Martin, Germany: Eric Farges, Portugal: Joana Silveira

Data Management:

Massimiliano Pepe, Medtronic Italia, Rome, Italy Remote Data Entry System, SL, Barcelona, Spain

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

Footnotes

Xavier Navarro, Elisabetta Santi, and Tiziana De Santo report being employed by Medtronic at the time of the study.

An erratum to this article can be found at http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s10840-010-9495-3

References

- 1.Moss AJ, Zareba W, Hall WJ, et al. Multicenter Automatic Defibrillator Implantation Trial II Investigators. Prophylactic implantation of a defibrillator in patients with myocardial infarction and reduced ejection fraction. New England Journal of Medicine. 2002;346:877–883. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa013474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bardy GH, Lee KL, Mark DB, et al. Sudden Cardiac Death in Heart Failure Trial (SCD-HeFT) Investigators. Amiodarone or an implantable cardioverter-defibrillator for congestive heart failure. New England Journal of Medicine. 2005;52:225–237. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa043399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sears SF, Todaro JF, Urizar G, et al. Assessing the psychosocial impact of the ICD: a national survey of implantable cardioverter defibrillator health care provides. Pacing and Clinical Electrophysiology. 2000;23:939–945. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-8159.2000.tb00878.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Luederitz B, Jung W, Deister A, et al. Patient acceptance of the implantable cardioverter-defibrillator in ventricular tachyarrhythmias. Pacing and Clinical Electrophysiology. 1993;16:1815–1821. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-8159.1993.tb01816.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sears SF, Sowell LDV, Kuhl EA, et al. The ICD shock and stress management program: a randomized trial of psychosocial treatment to optimize quality of life in ICD patients. Pacing and Clinical Electrophysiology. 2007;30(7):858–864. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-8159.2007.00773.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Batchelder JE, Zipes DP. Treatment of tachyarrhythmias by pacing. Archives of Internal Medicine. 1975;135(8):1115–1124. doi: 10.1001/archinte.135.8.1115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jiménez-Candil J, Arenal A, García-Alberola A, et al. Fast ventricular tachycardias in patients with implantable cardioverter-defibrillators: efficacy and safety of anti-tachycardia pacing. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 2005;45(3):460–461. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2004.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Peinado R, Almendral J, Rius T, et al. Randomized prospective comparison of four burst pacing algorithms for spontaneous ventricular tachycardia. American Journal of Cardiology. 1998;82(11):1422–1425. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9149(98)00654-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wilkoff BL, Ousdigian KT, Sterns LD, et al. EMPIRIC Trial Investigators. A comparison of empiric to physician-tailored programming of implantable cardioverter-defibrillators: results from the prospective randomized multicenter EMPIRIC trial. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 2006;48:330–339. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2006.03.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wilkoff BL, Williamson BD, Stern RS, et al. PREPARE Study Investigators. Strategic programming of detection and therapy parameters in implantable cardioverter-defibrillators reduces shocks in primary prevention patients: results from the PREPARE (Primary Prevention Parameters Evaluation) study. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 2008;52(7):541–550. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2008.05.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Schwab JO, Gasparini M, Lunati M, et al. Avoid delivering therapies for nonsustained fast ventricular tachyarrhythmia in patients with implantable cardioverter/defibrillator: the ADVANCE III Trial. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 2009;20:663–666. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-8167.2008.01415.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lunati M, Defaye P, Mermi J, et al. Improvement of quality of life by means of antitachycardia pacing: from Painfree to the ADVANCE-D trial. Pacing and Clinical Electrophysiology. 2006;29(Suppl 2):S35–S39. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-8159.2006.00488.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Liang KY, Zeger S. Longitudinal data analysis using generalized linear models. Biometrika. 1986;73:13–22. doi: 10.1093/biomet/73.1.13. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wathen MS, Sweeney MO, DeGroot PJ, et al. Shock reduction using antitachycardia pacing for spontaneous rapid ventricular tachycardia in patients with coronary artery disease. Circulation. 2001;104(7):796–801. doi: 10.1161/hc3101.093906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wathen MS, DeGroot PJ, Sweeney MO, et al. Prospective randomized multicenter trial of empirical antitachycardia pacing versus shocks for spontaneous rapid ventricular tachycardia in patients with implantable cardioverter-defibrillators: pacing fast ventricular tachycardia reduces shock therapies (PainFREE Rx II) trial results. Circulation. 2004;110(17):2591–2596. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000145610.64014.E4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Poole JE, Johnson GW, et al. Prognostic importance of defibrillator shocks in patients with heart failure. New England Journal of Medicine. 2008;359:1009–1017. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa071098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Daubert JP, Zareba W, Cannom DS, for the MADIT II Investigators et al. Inappropriate implantable cardioverter-defibrillator shocks in the MADIT II study: frequency, mechanisms, predictors, and survival impact. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 2008;51:1357–65.8. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2007.09.073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gulizia MM, Piraino L, Scherillo M, et al. A randomized study to compare ramp versus burst antitachycardia pacing therapies to treat fast ventricular tachyarrhythmias in patients with implantable cardioverter-defibrillators: the PITAGORA ICD Trial. Feb 13 2009. Circ Arrhythmia Electrophhysiol. 2009;2:146–153. doi: 10.1161/CIRCEP.108.804211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]