Abstract

A generalized platform for introducing a diverse range of biomolecules into living cells in high-throughput could transform how complex cellular processes are probed and analyzed. Here, we demonstrate spatially localized, efficient, and universal delivery of biomolecules into immortalized and primary mammalian cells using surface-modified vertical silicon nanowires. The method relies on the ability of the silicon nanowires to penetrate a cell’s membrane and subsequently release surface-bound molecules directly into the cell’s cytosol, thus allowing highly efficient delivery of biomolecules without chemical modification or viral packaging. This modality enables one to assess the phenotypic consequences of introducing a broad range of biological effectors (DNAs, RNAs, peptides, proteins, and small molecules) into almost any cell type. We show that this platform can be used to guide neuronal progenitor growth with small molecules, knock down transcript levels by delivering siRNAs, inhibit apoptosis using peptides, and introduce targeted proteins to specific organelles. We further demonstrate codelivery of siRNAs and proteins on a single substrate in a microarray format, highlighting this technology’s potential as a robust, monolithic platform for high-throughput, miniaturized bioassays.

Keywords: intracellular delivery, microarray, high-throughput bioassay, nanobiotechnology

At the heart of all investigations into cellular function lies the need to induce specific and controlled perturbations to cells. An assortment of tools is now available to accomplish this in a rational and directed fashion by delivering various biological effectors (small molecules, DNAs, RNAs, peptides, and proteins) (1–7). These options, however, are often limited to either particular molecules or certain cell types due to the lack of a general strategy for transporting polar or charged molecules across the plasma membrane. With the increasing availability and diversity of biological effectors, methods to effectively introduce multiple types of reagents into virtually any cell type in high-throughput have the potential to transform the study of cellular function and ultimately enable precise control over cell fate (8).

To date, microarray-based methods have been used to deliver nucleic acids into cells (9, 10) and to perturb cells with extracellular factors (11–13). The direct introduction of peptides, native proteins, and cell-impermeable small molecules into live cells in a microarray format has yet to be accomplished (14). An ideal method for administering biological reagents into cells should: (i) minimally disrupt cell survival and function; (ii) deliver any type of biomolecule with high efficiency; (iii) work across a wide range of cell types; (iv) be compatible with a diverse set of biologically informative assays; and (v) lend itself to high-throughput investigations. In addition, for those cell types that are only available in limited amounts (e.g., stem cells), compatibility with assay miniaturization is essential.

Vertical nanowire (NW) substrates can satisfy these stringent requirements because the NWs enable direct physical access to the cells’ interiors (15–19). Here, we report an experimental platform based on vertical silicon (Si) NWs that can deliver virtually any type of molecule into a wide variety of cells in a format compatible with microarray technology and live-cell imaging. Building on the previous observation that vertically grown NWs can support cell culture (15–19), we show that vertical NW substrates can serve as a universal, scalable, and highly efficient modality for introducing DNAs, RNAs, peptides, proteins, and small molecules into both immortalized and primary cell types, without chemical modification or viral packaging. This simplicity and generality, which stem from the direct physical access to the cell’s interior afforded by NW penetration (15–19), make NW-based delivery distinct from chemical and viral methods that are widely employed (1–6). Furthermore, this NW-based system is fully compatible with standard microarray printing techniques, allowing large collections of biomolecules to be delivered, or even codelivered, into live cells in a parallel and miniaturized fashion.

Results and Discussion

Vertical Si NWs, Regardless of Surface Coating, Penetrate into Cells in a Minimally Invasive Fashion.

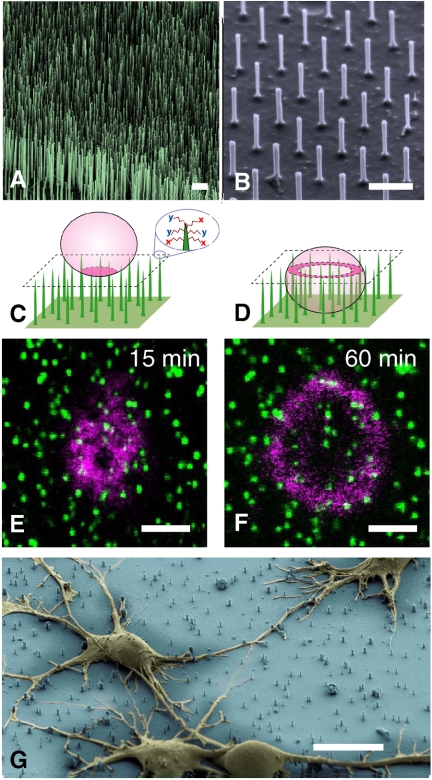

The operational principle of the vertical NW delivery platform is illustrated in Fig. 1. Si NW substrates can be prepared by either growing the NWs epitaxially from a silicon wafer using chemical vapor deposition (CVD) (Fig. 1A and Fig. S1A and B) (20) or etching them from a wafer using standard semiconductor techniques (21) (Fig. 1B and Fig. S1C). The densities, diameters, and heights of the NWs can be precisely controlled by varying the processing parameters. In addition, by altering the NW surface chemistry using a variety of alkoxysilane treatments (22), different tethering chemistries can be achieved. Specifically, in the experiments described below, NWs were coated with a short aminosilane, leading to noncovalent (electrostatic and/or van der Waals), nonspecific binding of molecules. In culture media, molecules are released slowly from the NWs. While more controlled binding and release can be achieved via other surface treatments, the chosen nonspecific binding mechanism endows a single platform with the versatility to deliver and codeliver diverse biomolecules.

Fig. 1.

Si NWs as a generalized platform for delivering a wide range of biological effectors. (A) and (B) Scanning electron micrographs of vertical Si NWs fabricated via CVD and reactive ion etching, respectively. Scale bar in A and B, 1 μm. (C) and (D) Schematic renderings of cells (Pink) on Si NWs (Green) at early and late stages of penetration, respectively. Molecules of interest (X & Y) are nonspecifically tethered to the Si NW surface via alkoxysilane treatment. Upon penetration and delivery, those molecules can alter the cell’s behavior. (E) and (F) Confocal microscope sections (corresponding to the dashed boxes in C and D) of a HeLa cell in the process of being penetrated. Scale bar in E and F, 10 μm. (E) After 15 minutes, the cell membrane, labeled with DiD, sits atop the tips of the wires that are coated with cystamine and Alexa Fluor 488 SE (as shown in C). (F) Within one hour, the same plane shows a magenta circle, the cell’s circumference, surrounding green-labeled wires, indicating NW penetration into the cell (as shown in D). Regardless of the molecular coating, the majority of cells are penetrated within one hour (Fig. S2C). (G) Scanning electron micrograph of rat hippocampal neurons (false colored Yellow) atop a bed of etched Si NWs (false colored Blue), showing characteristic morphology (taken one day after plating). Scale bar, 10 μm.

Previous studies have shown that vertical NWs spontaneously penetrate cells’ membranes when cells are placed on top of the NWs (15–19). To visualize this penetration process, DiD-membrane-labeled HeLa cells (Magenta) were seeded on a bed of Si NWs whose gold tips had been prelabeled with cystamine and Alexa Fluor 488 SE (Green). At 15 min after plating, most of the cells were resting on top of the Si NWs (Fig. 1C and E). By 1 h after plating, however, most of those cells were impaled by the NWs, as indicated by a group of green-labeled wire tips encircled by the magenta ring of the DiD-labeled membrane (Fig. 1D and F). A detailed kinetic study based on sequential confocal imaging revealed that NW penetration was complete in greater than 95% of the cells after an hour, regardless of the NW density or identity of the molecule attached to the NW surface (Fig. S2).

Despite being impaled, cells cultured on vertical Si NWs grow and divide over a period of weeks, consistent with previous studies of cell growth on surface-delimited nanostructures (15–19), (23–25). The scanning electron microscope image in Fig. 1G shows primary rat hippocampal neurons growing unhindered and beginning to make synaptic connections despite Si NW penetration. Up to two weeks after plating, these cells fire action potentials upon current injection (see, for example, Fig. S3G) and show typical spontaneous activity. The cells’ ability to maintain the distinct intracellular ionic concentrations necessary for action potential firing indicates that the integrity of the cellular membrane is preserved despite its penetration by Si NWs.

Some cell functions are initially perturbed by NW impalement. As reported previously (18), HeLa cells grow more slowly on NWs than on glass coverslips. Confocal microscopy reveals that when HeLa cells are seeded on CVD-grown Si NWs, they temporarily develop irregular contours, suggesting that the NWs physically impede the interaction between the cell membrane and the solid substratum required for cell attachment and spreading. An analysis of Annexin V binding (26) suggests that NW penetration also induces lipid scrambling, which is then actively reversed in healthy cells (Fig. S4A to C). Cell morphology returns to normal within a few hours, however. Significantly, quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction (Q-PCR) analyses of HeLa S3 cells and human fibroblasts cultured on etched Si NWs show that the transcript levels of five common housekeeping genes are similar to those in cells cultured on either blank silicon or uncoated multiwell plates (Fig. S4D). In addition, cells cultured on NWs can be detached from the surface using trypsin and cultured further on glass coverslips or in multiwell plates. Thus, it appears that NW-induced perturbations are minimal, although the details of their effects on cell physiology should be investigated further.

Si NWs Can Deliver and Codeliver a Wide Variety of Molecules into a Broad Range of Cell Types.

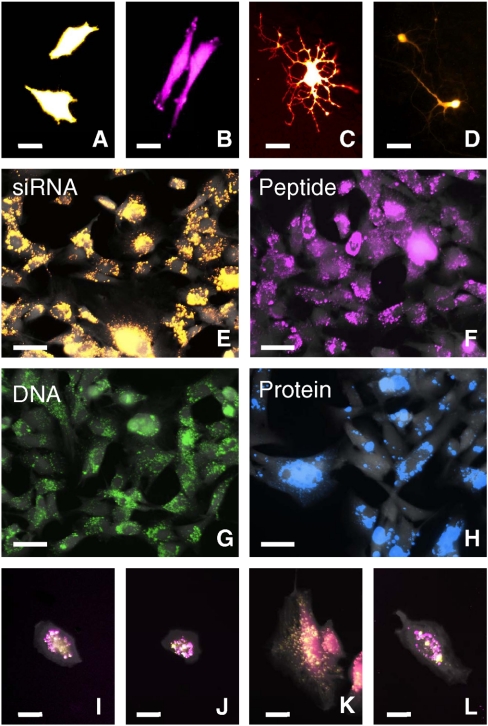

Direct access to the cells’ interiors enables NWs to efficiently deliver a broad range of exogenous materials into multiple cell types, without the need for chemical or viral packaging protocols required by other methods. Fluorescence images in Fig. 2A to D show immortalized (HeLa) and primary cells (human fibroblasts, rat neural progenitor cells (NPCs), and rat hippocampal neurons) expressing fluorescent proteins encoded by plasmid DNAs that were administered using Si NWs, whereas Fig. 2E to H demonstrates the delivery of various biomolecules (siRNAs, peptides, DNAs, and proteins). Moreover, different types of biomolecules can be introduced into the same cell simultaneously by simply codepositing them onto the NWs, as illustrated in Fig. 2I to L. The fluorescence images in Fig. 2E to L were obtained by culturing human fibroblasts on Si NWs to which diverse fluorescently labeled molecules were attached (Fig. S5 and SI Text). After a 24-h incubation, we removed the cells from the Si NW substrates with trypsin, replated them on glass cover slips, and then imaged them using a fluorescence microscope. In every case, the fluorescently labeled biomolecules were observed in over 95% of the cells, regardless of the type of molecule being delivered (Fig. 2E to H). Additionally, we performed experiments where the molecules of interest were added either with the cells at the time of plating or to the culture media 45 min later. As compared to surface-based presentation of the molecules, solution-based introduction, concurrent or delayed, resulted in a significant reduction of the fluorescence intensity within the cells (Fig. S6). While some of the molecules might also be delivered via diffusion through pores briefly opened during the penetration process, the data indicate that NW penetration and the subsequent release of molecules is the dominant means of molecule delivery.

Fig. 2.

Si NWs can deliver and codeliver diverse biomolecular species to a broad range of cell types. (A)–(D) Various immortalized and primary cell types expressing fluorescent proteins after being transfected with plasmid DNA via the Si NWs: (A) HeLa S3 cells (pCMV-TurboRFP), (B) human fibroblasts (pCMV-TurboRFP), (C) NPCs (pCMV-mCherry), and (D) primary rat hippocampal neurons (pCMV-dTomato). Scale bar in A–D, 25 μm. (E)–(H) Human fibroblasts transfected with a variety of biochemicals. To verify intracellular delivery, following a 24-h incubation on coated Si NWs, cells were replated on glass coverslips for imaging. Epifluorescence images show > 95% of the cells receive: (E) siRNA (Alexa Fluor 546 labeled AllStar Negative Control siRNA), (F) peptides (rhodamine labeled 9-mer), (G) plasmid DNA (labeled with Label-IT Cy5), and (H) proteins (recombinant TurboRFP-mito). Scale bars in E–H, 50 μm. (I)–(L) Fluorescence images of human fibroblasts cotransfected with two different molecules using Si NWs: (I) two different siRNAs (Alexa 546 labeled siRNA—yellow & Alexa 647 labeled siRNA—magenta), (J) a peptide and an siRNA (rhodamine labeled peptide—yellow & Alexa 647 labeled siRNA—magenta), (K) plasmid DNA and an siRNA (Cy5-labeled TagBFP plasmid DNA—yellow & Alexa 546 labeled siRNA—magenta), and (L) a recombinant protein and an siRNA (recombinant TurboRFP-mito—yellow & Alexa 647 labeled siRNA—magenta). In E to L, to facilitate identification, cell membranes were labeled with fluorescein (Gray). Scale bars in I–L, 25 μm.

NW-Mediated Delivery of Biological Effectors Induce Cellular Responses That Can Be Assayed Directly on Top of NW Substrates.

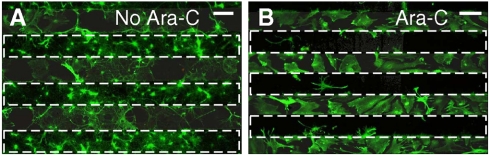

Because the vertical NW platform is compatible with live-cell cultures and common imaging protocols, phenotypic responses to exogenous biological effectors can be assayed directly using standard microscopy techniques. Specifically, Fig. 3 illustrates that the growth of NPCs, also referred to as neurospheres, is affected by the delivery of a surface-tethered antimitotic agent, Cytarabine (Ara-C) (27). When a solution of Ara-C was applied to line-patterned Si NW substrates (Fig. S1A), glial-like cells proliferated and achieved confluence only in the areas between the NW strips, indicating that Ara-C-coated Si NWs inhibit cell division (Fig. 3 and Fig. S7). In cases where neurospheres were not fully triturated down to individual cells, we observed inhibition of glial-like cell growth in regions containing Ara-C coated NWs (Fig. S7); without Ara-C, the same spheres grew isotropically. It should be noted that glial-like cell growth was not inhibited in the regions devoid of NWs (Fig. 3 and Fig. S7), indicating that the effects of Ara-C were isolated to those cells that were penetrated by the Si NWs. This observation demonstrates that small, bioactive molecules can be effectively delivered into living cells using NWs. Moreover, the same observation shows that the effects of dissociated molecules in solution are minimal.

Fig. 3.

Mitotic inhibition via patterned Si NW delivery of Ara-C. Here, dissociated NPCs have been plated on a line-patterned Si NW substrate that was blanket coated with the small molecule mitotic inhibitor Ara-C. (A) NPCs plated on a line-patterned Si NW substrate in the absence of Ara-C divide out isotropically from their point of plating. (B) Cell division is selectively stopped as cells enter or cross regions where the Si NWs deliver Ara-C (dashed squares). Scale bars, 100 μm.

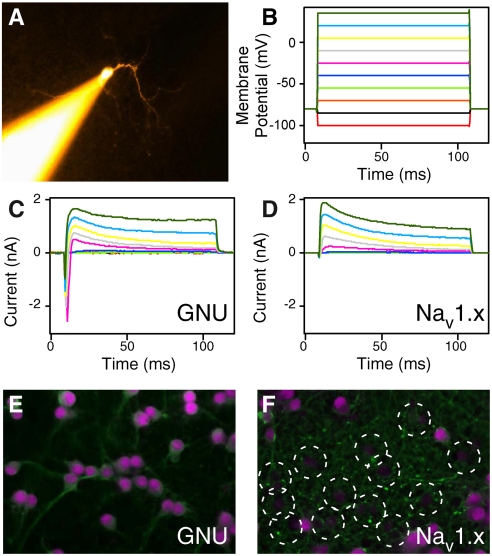

Fig. 4 shows a phenotypic response to NW-assisted delivery of another biomolecule: siRNA administered to rat hippocampal neurons. Here, we chose an siRNA that targets fast, inward sodium channels, including NaV1.1 (Scn1a), NaV1.2 (Scn2a1), NaV1.3 (Scn3a), and NaV1.9 (Scn9a) (28); an siRNA directed against the Drosophila melanogaster GNU gene was used as a negative control. When we measured ion currents in hippocampal neurons using a whole-cell patch clamp 8 d after plating, we found that neurons transfected with NaV1.X channel-targeting siRNAs exhibited substantially reduced sodium currents in response to depolarizing voltage steps (Fig. 4B and D). In contrast, GNU-transfected cells showed normal inward sodium currents (Fig. 4B and C). Immunostaining for the alpha subunit of NaV1.1 confirmed that substantial knockdown had been achieved (Fig. 4E and F). Similar results were obtained using plasmids that coexpressed EGFP and short hairpin RNAs directed at the NaV1.X transcripts (Fig. S3 and SI Text). In these cells, we were not able to observe either spontaneous or evoked action potentials, as expected for high levels of sodium channel knockdown (Fig. S3 and SI Text).

Fig. 4.

Gene knockdown via NW-mediated siRNA delivery. (A) Fluorescence image showing patch clamping of a typical rat hippocampal neuron (E18) on Si NWs (8 d after plating). (B) Applied hyper- and depolarizing voltage steps. (C) and (D) Current responses of a neuron transfected with a control siRNA (GNU) and siRNA targeted against sodium channels (Nav1.X), respectively. Panel C displays fast inward sodium currents and outward delayed-rectifier potassium currents while D only shows the latter. (E) and (F) Immunofluorescence images of rat hippocampal neurons on Si NWs transfected with siRNA for GNU and Nav1.X respectively. Cells were stained for voltage-gated sodium channel type 1 alpha (Scn1a, Pink) and beta-III-tubulin (Green). (F) shows several cells (dashed circles) with significantly reduced expression of sodium channels compared to E.

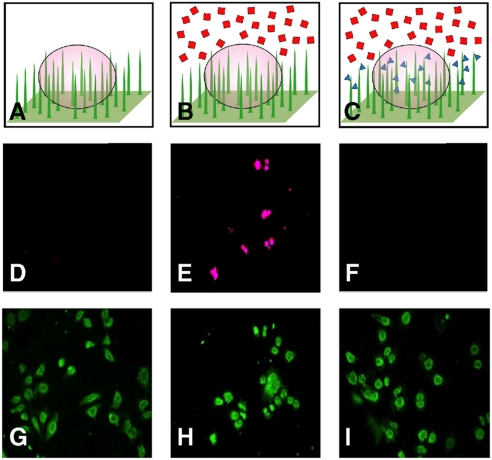

Fig. 5 shows that peptides delivered using the NW platform can induce a phenotypic response in live cells. While DNAs and RNAs are commonly employed to perturb cellular function, peptides and proteins are rarely used (3). To a large extent, this paucity stems from a lack of efficient delivery methods, although low intracellular stability of peptides is also a factor. In cases where it is desirable to avoid the use of genetic material, however, peptide- and protein-based reagents can provide a powerful alternative (29). To demonstrate NW-based delivery of bioactive peptides, we coated amine-functionalized Si NWs with Ac-DEVD-CHO, an aldehyde-terminated tetrapeptide that prevents apoptosis by selectively inhibiting caspase-3/7 (30). When we introduced the apoptosis-inducing agents TNF-α and actinomycin-D to the culture media, HeLa cells on untreated Si NWs underwent rapid apoptosis (as determined by a TUNEL assay (SI Text), Fig. 5E and H). In contrast, HeLa cells cultured on Ac-DEVD-CHO-coated Si NWs did not (Fig. 5F and I). Moreover, HeLa cells plated on untreated NW substrates that were coincubated with Ac-DEVE-CHO-coated wires did undergo apoptosis, indicating that penetration by the treated wires is necessary for realizing the inhibitory effect.

Fig. 5.

Apoptosis inhibition by Si NW delivered peptides. (A)–(C) Schematics of apoptosis inhibition via peptide delivery: (A) control culture of HeLa cells on Si NWs, (B) bath application of apoptosis-inducing agents Act-D and TNF-α (Red Squares), and (C) bath application of Act-D and TNF-α with wires coated in the apoptosis-inhibiting peptide Ac-DEVD-CHO (Blue Triangles). (D)–(F) TUNEL assay of HeLa cells on Si NWs. (D)–(F) Dead nuclei (Pink), for the experiments depicted in A–C respectively. (G)–(I) fluorescence images showing the labeled cell membranes (Green) of all cells assayed in D–F respectively. (E) shows bath application of Act-D and TNF-α induced apoptosis (as compared to the control D), while NW-mediated delivery of Ac-DEVD-CHO effectively inhibits the induced apoptosis (F).

Site-Specific, Biologically Effective Molecule Delivery Can Be Achieved by Arraying Molecules on Top of the Si NW Platform.

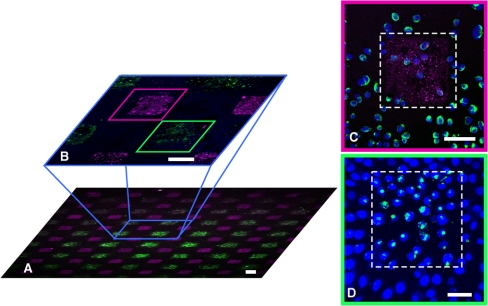

The NW-based transfection platform is directly compatible with microarray technology because the delivery of biomolecules is mediated by the surfaces of the Si NWs themselves. Massively parallel, live-cell screening of diverse biological effectors is thus possible by arraying these molecules on a NW surface. As a proof-of-concept, we printed a 400 - μm pitch checkerboard pattern of Alexa Fluor 488 labeled histone H1 and Alexa Fluor 546 labeled siRNA targeting the intermediate filament vimentin onto Si NW surfaces. We then seeded the arrays with HeLa S3 cells and imaged those cells using fluorescence microscopy (Fig. 6). As anticipated, substantial knockdown of vimentin was observed in the majority of HeLa S3 cells sitting atop the siRNA sites (Fig. 6C and Fig. S8). Meanwhile, the labeled histones were delivered and actively transported to the nuclei of the HeLa S3 cells sitting atop the histone microarray spots (Fig. 6D). Similar results were obtained using a variety of other targeted proteins and peptides (Fig. S9).

Fig. 6.

The NW-delivery platform can be combined with microarray printing to deliver bioactive molecules in a site-specific fashion. (A) Epifluorescence image (4x) of HeLa S3 cells grown on top of a two-molecule microarray (4 d after plating). The array, printed on the NW substrate with a 400 - μm pitch, consists of siRNAs targeted against the intermediate filament vimentin (labeled with Alexa Fluor 546, Pink) and a nuclear histone H1 protein (labeled with Alexa Fluor 488, Green). (B) Confocal image (625 μm × 625 μm) showing the subcellular localization of the siRNAs and histones in the cells. (C) and (D) Confocal zoom-ins of individual spots where siRNAs and histones have been delivered, respectively. (C) Immunostaining for vimentin (Green) and nuclei (Blue) shows that a group of cells receiving siRNAs (Red), outlined in the dotted square, display knocked-down vimentin expression. (D) Cells in the dotted square show histones (Green) intracellularly delivered and subsequently targeted to the cells’ nuclei (Blue). Scale bar in A and B (C and D), 100 (50) μm.

Prospects.

The results presented here establish vertical Si NW arrays as a robust, monolithic platform for introducing various bioactive molecules into a broad range of cell types in high-throughput. This delivery method is highly efficient, even with primary cells that are notoriously difficult to transfect or transduce using conventional methods (1–6). Additionally, this platform requires neither viral packaging nor chemical modification of the molecules to be delivered, thus significantly reducing the efforts required for typical bioassays. Fabrication of the NW substrates is straightforward using standard silicon processes and can be scaled to provide the quantity and consistency needed to support widespread adoption of this technique (Fig. S1C). Finally, this method is fully compatible with multiplexing and microarray technology. The microarray density shown in Fig. 6A and B is ∼250 per square cm, but could easily be increased to ∼1,000 per square cm → using smaller pins. In principle, this could enable ∼20,000 peptides or proteins, or multicomponent combinations thereof (Fig. 2I to L), to be screened on a single microscope slide, or a genome-wide RNAi screen to be performed using rare cell types (e.g., stem cells). We anticipate that this platform will impact a broad range of high-throughput discovery efforts, with applications in the areas of cell and systems biology, drug discovery, and cellular reprogramming.

Experimental Procedures

Preparation of Si NWs via CVD.

Si NWs were grown on Si (111) wafers from immobilized gold nanoparticles as previously described (20, 31–33) (Fig. 1A). Patterning was achieved by either flowing a solution of gold nanoparticles through polydimethysiloxane microfluidic channels or selectively stamping it using patterned PDMS (20, 31–33) (Fig. S1A and B).

Preparation of Si NWs by Etching.

Si NWs were formed by dry-etching Si wafers coated with 200 nanometer (nm) of thermally grown silicon oxide. For the generation of regularly spaced arrays (Fig. 1B), a gold nanoparticle template was prepared by microsphere lithography with close-packed 1 μm diameter polystyrene spheres (34). To fabricate NWs over larger areas, concentrated colloidal gold nanoparticles were resuspended in a resist, spun coat on a Si wafer, and then used to pattern that wafer’s thermal oxide (Fig. 1G and Fig. S1C and Fig. S5).

Scanning Electron Microscope Analyses.

Cells were fixed in a solution of 4% glutaraldehyde in 0.1 M sodium cacodylate (2 h), rinsed, and fixed again in a 1% solution of osmium tetroxide in 0.1 M sodium cacodylate (2 h). The samples were then dehydrated in gradually increasing concentrations of ethanol (from 50–100%) in water, dried in a critical point dryer, and sputter-coated with a few nanometers of platinum/palladium (Fig. 1G and Fig. S5).

Tip Functionalization of Si NWs.

CVD-grown Si NWs were plasma-treated and immersed in an ethanolic solution of 15 mM cystamine (RT, 3 h). After rinsing, they were treated overnight in 1∶3 Alexa Fluor 488 SE in anhydrous DMSO (5 mg/mL) to sodium tetraborate, pH 8.5.

Cell Membrane-Labeling.

Harvested HeLa cells were resuspended in 4 mL of premixed membrane-labeling solution (4 μL Vibrant 1'-dioctadecyl-3,3,3',3'-tetramethylindodicarbocyanine (DiD) per 1 mL of Eagle’s Minimum Essential Medium), incubated for 8 min at 37 °C, and washed twice before use.

Confocal Imaging of NW Penetration Kinetics.

DiD-labeled HeLa cells were plated on CVD-grown NWs whose gold tips had been labeled with Alexa Fluor 488. After incubating for 10 min at 37 °C, the samples were transferred to prewarmed OptiMEM and imaged. Penetration was quantitatively analyzed every 10 min by obtaining cross-sectional confocal fluorescence images at the focal plane defined by the tips of the NWs and then scoring cells upon penetration. (Fig. S2)

Surface Functionalization of Si NWs.

Si NWs were incubated in 1% (v/v) 3-aminopropyltrimethoxysilane (APTMS) in toluene for 1 h under nitrogen at RT. The substrates were then place in tris-buffered saline for 1 h, rinsed, and dried. For some experiments, Si NWs were incubated in 10% APTMS in toluene for 3 h and then rinsed and dried.

Noncovalent, Nonspecific Binding of Molecules to Si NWs.

Substrates were incubated in PBS with various fluorescent molecules (RT, 1 h) and then rinsed. Alternatively, they were coated by dispensing a small volume of solution (2–8 μL/cm2, concentration: 0.1–1 μg/μL) atop a substrate. After the solvent evaporated, the samples were used without further washing.

Culture of Immortal Cells on Si NWs.

1 × 104 trypsin harvested cells in 10 μL media were plated atop a 3 mm × 6 mm sample. After a 15-45 min incubation, additional media was added.

Culture of Neural and Neural Precursor Cells on Si NWs.

Dissociated E18 embryonic hippocampal neurons (35) or passaged neurospheres (36) were plated on Si NW substrates as small drops so as to yield a final density of ∼5 × 104 cells/cm2. After a 15 min incubation, the relevant culturing media was added; for selection of neurons alone, a Neurobasal/B27 media was used (35), whereas for the concurrent generation of glia, a BME/FBS based media was selected (37). A 50% media swap was performed on the fourth, seventh, and eleventh days.

RNA Extraction and Q-PCR Analysis.

Total cellular RNA was isolated and quantitative mRNA analysis of five housekeeping genes and vimentin was performed (38) (Fig. S4D and Fig. S8). (SI Text).

Delivery of Exogenous Biomolecules into Cells.

Si NW samples were precoated with various fluorescent molecules (5 μL at 1 μg/uL): plasmid DNA prelabeled with Label-IT Cy3 or Cy5, siRNA labeled with Alexa Fluor 546 and Alexa Fluor 647, IgGs labeled with Alexa Fluor 488 and Qdot 585, Qdots 525 and 585, rhodamine labeled peptides, and recombinant fluorescent proteins (SI Text). Human fibroblasts were then plated on the samples as described above. After 24 h, the cells were removed with trypsin, replated on glass coverslips, and placed back into the incubator. Three hours later, the settled cells were imaged (Olympus, EXFO, Chroma). To aid in identifying cells, the samples were incubated in 10 μg/mL fluorescein diacetate in PBS for 1 min to label cells’ membranes (Fig. 2E to L). Control experiments, in which fluorescent biomolecules were added to the culture simultaneously, 45 min, or 3 h after plating, demonstrated that Si NW penetration dominates molecular delivery (Fig. S6) (SI Text).

Electrophysiological Recording.

Whole-cell patch clamp recordings were made from rat hippocampal neurons cultured on Si NWs as previously described (39) (SI Text).

Construction of siRNA.

For vimentin knockdown experiments, two siRNA solutions were used: the first consisted of Alexa Fluor 546 labeled Hs_VIM_11 HP Validated siRNA (sense strand: 5′- GAUCCUGCUGGCCGAGCUCtt—Alexa Fluor 546-3′); and the second consisted of an equal parts siRNA pool of Hs_VIM_11 HP Validated siRNA, Hs_VIM_4 HP Validated siRNA (sense strand: 5′-GGCACGUCUUGACCUUGAAtt—Alexa Fluor 546-3′), and Hs_VIM_5 HP Validated siRNA (5′-GAAGAAUGGUACAAAUCCAtt—Alexa Fluor 546-3′). As a control, Alexa Fluor 546 and Alexa Fluor 647 labeled AllStar Negative siRNAs were used. All above-mentioned siRNAs were obtained from Qiagen. For sodium channel knockdown experiments, custom siRNAs were ordered from Qiagen. The 21-mers used were made by targeting against 19-mer sense sequences chosen from prior shRNA experiments (28) (SI Text). NaV1.X targeted siRNA sense strand: 5′-UCGACCCUGACGCCACUtt—Alexa Fluor 546-3′; GNU targeted siRNA sense sequence: 5′-ACUGAGAACUAAGAGAGtt—Alexa Fluor 546-3′.

siRNA Experiments.

HeLa S3 cells were plated on anti-Vimentin siRNA-coated Si NWs. At 2 d, a full media swap was performed. Immunostained cells (SI Text) were visualized using both epifluorescence and confocal imaging (Olympus). Confocal laser powers and gains were set using HeLa cells receiving control AllStar Negative siRNA and three-dimensional image reconstructions were made using BitPlane (Imaris). Substantial knockdown was seen when the Si NWs were used to deliver individual or pooled siRNAs against vimentin; no knockdown was seen when either a control siRNA or no molecule was used (Fig. S8). Sodium channel knockdowns were performed by plating E18 rat hippocampal neurons on siRNA-coated, grown Si NWs as above. Electrophysiological measurements were made at 8 d after plating (Fig. 4). Following patch clamp recordings, samples were fixed, immunostained, and analyzed (Fig. 4). For both knockdowns, as a control, a conventional siRNA delivery reagent, Hyperfect (Qiagen), was used according to the manufacturer’s recommendations. Results obtained from either NW- or Hyperfect-based delivery were similar as determined by immunofluorescence and Q-PCR (Fig. S8).

Apoptosis Experiments.

Silanized Si NWs were treated with 100 mM Ac-DEVD-CHO in PBS (RT, 1 h). HeLa cells (5 × 104 cells/mL) in DMEM were added onto the Si NWs, and incubated (2 h). The samples were then transferred into fresh DMEM containing actinomycin-D (1 μg/mL) and incubated for 30 min, before the addition of TNF-α (2 nanograms/mL). After 7 h incubation, the cells on the Si NWs were analyzed for apoptosis by either the Terminal Deoxynucleotide Transferase dUTP Nick End Labeling (TUNEL) assay or the Annexin V (26, 30). See Fig. 5, Fig. S4A to C, and SI Text for more details.

Ara-C Delivery.

Silanized Si NWs were coated with Ara-C (Cytarabine) in BME, and passaged neurospheres were plated on the substrates as described above. On the sixth day, the cells were examined, immunostained (SI Text), and imaged. See Fig. 3 and Fig. S7.

Microarray Patterning.

siRNA, purified recombinant proteins, and labeled IgGs were printed on flat Si and NW substrates using a Nanoprint contact array printer (Arrayit). The printer was equipped with a flathead, square pin (NS6) of 150 μm width. Single depositions of samples were printed as an array at a pitch of 300 to 500 μm using samples ranging in concentrations from 200 to 400 μM. For arrays containing multiple sample types, the second sample was printed offset from the first after the first was fully arrayed (Fig. 6A and B). Additional images of site-specific delivery can be seen in Fig. S9 online.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments.

We thank D.R. Liu, S. A. Jones, G. Lau, M. Wienisch, N. Sanjana, B. Ilic, M. Metzler, E. Hodges, and L. Xie for scientific discussions and technical assistance. We also thank T. Schlaeger and S. Ratanasirintrawoot for the kind gift of dH1f and dH9f fibroblasts. The nanowire fabrication and characterization were performed in part at the Center for Nanoscale Systems at Harvard University. This work was supported by a National Institutes of Health Pioneer award and the National Science Foundation (to H.P.), the Korea Institute of Science and Technology Core-Competence Program (to E.G.Y), and the W. M. Keck Foundation and the National Institutes of Health (to G.M.).

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission. P.Y. is a guest editor invited by the Editorial Board.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/cgi/content/full/0909350107/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Whitehead KA, Langer R, Anderson DG. Knocking down barriers: Advances in sirna delivery. Nat Rev Drug Discovery. 2009;8:129–138. doi: 10.1038/nrd2742. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kay MA, Glorioso JC, Naldini L. Viral vectors for gene therapy: The art of turning infectious agents into vehicles of therapeutics. Nat Med. 2001;7:33–40. doi: 10.1038/83324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wadia JS, Dowdy SF. Protein transduction technology. Curr Opin Biotechnol. 2002;13:52–56. doi: 10.1016/s0958-1669(02)00284-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.McNaughton BR, Cronican JJ, Thompson DB, Liu DR. Mammalian cell penetration, sirna transfection, and DNA transfection by supercharged proteins. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2009;106:6111–6116. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0807883106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Liu Z, Mark W, Mark H, Hongjie D. Sirna delivery into human t cells and primary cells with carbon-nanotube transporters13. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2007;46:2023–2027. doi: 10.1002/anie.200604295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sokolova V, Matthias E. Inorganic nanoparticles as carriers of nucleic acids into cells. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2008;47:1382–1395. doi: 10.1002/anie.200703039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chen X, Kis A, Zettl A, Bertozzi CR. A cell nanoinjector based on carbon nanotubes. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2007;104:8218–8222. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0700567104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wu RZ, Bailey SN, Sabatini DM. Cell-biological applications of transfected-cell microarrays. Trends Cell Biol. 2002;12:485–488. doi: 10.1016/s0962-8924(02)02354-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ziauddin J, Sabatini DM. Microarrays of cells expressing defined cdnas. Nature. 2001;411:107–110. doi: 10.1038/35075114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bailey SN, Ali SM, Carpenter AE, Higgins CO, Sabatini DM. Microarrays of lentiviruses for gene function screens in immortalized and primary cells. Nat Methods. 2006;3:117–122. doi: 10.1038/nmeth848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chen DS, Davis MM. Molecular and functional analysis using live cell microarrays. Curr Opin Chem Biol. 2006;10:28–34. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpa.2006.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Soen Y, Mori A, Palmer TD, Brown PO. Exploring the regulation of human neural precursor cell differentiation using arrays of signaling microenvironments. Mol Syst Biol. 2006;2:37. doi: 10.1038/msb4100076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Anderson DG, Levenberg S, Langer R. Nanoliter-scale synthesis of arrayed biomaterials and application to human embryonic stem cells. Nat Biotechnol. 2004;22:863–866. doi: 10.1038/nbt981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Berthing T, Sørensen CB, Nygård J, Martinez KL. Applications of nanowire arrays in nanomedicine. Journal of Nanoneuroscience. 2009;1:3–9. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kim W, Ng JK, Kunitake ME, Conklin BR, Yang P. Interfacing silicon nanowires with mammalian cells. J Am Chem Soc. 2007;129:7228–7229. doi: 10.1021/ja071456k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hallstrom W, et al. Gallium phosphide nanowires as a substrate for cultured neurons. Nano Lett. 2007;7:2960–2965. doi: 10.1021/nl070728e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jiang K, et al. Medicinal surface modification of silicon nanowires: Impact on calcification and stromal cell proliferation. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces. 2009;1:266–269. doi: 10.1021/am800219r. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Qi S, Yi C, Ji S, Fong C-C, Yang M. Cell adhesion and spreading behavior on vertically aligned silicon nanowire arrays. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces. 2009;1:30–34. doi: 10.1021/am800027d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Turner AMP, et al. Attachment of astroglial cells to microfabricated pillar arrays of different geometries. J Biomed Mater Res. 2000;51:430–441. doi: 10.1002/1097-4636(20000905)51:3<430::aid-jbm18>3.0.co;2-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hochbaum AI, Fan R, He R, Yang P. Controlled growth of si nanowire arrays for device integration. Nano Lett. 2005;5:457–460. doi: 10.1021/nl047990x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ovchinnikov V, Malinin A, Novikov S, Tuovinen C. Fabrication of silicon nanopillars using self-organized gold-chromium mask. Mater Sci Eng B. 2000;69–70:459–463. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Midwood KS, Carolus MD, Danahy MP, Schwarzbauer JE, Schwartz J. Easy and efficient bonding of biomolecules to an oxide surface of silicon. Langmuir. 2004;20:5501–5505. doi: 10.1021/la049506b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.McKnight TE, et al. Intracellular integration of synthetic nanostructures with viable cells for controlled biochemical manipulation. Nanotechnology. 2003;14:551–556. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pantarotto D, et al. Functionalized carbon nanotubes for plasmid DNA gene delivery. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2004;43:5242–5246. doi: 10.1002/anie.200460437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Park S, Kim Y-S, Kim WB, Jon S. Carbon nanosyringe array as a platform for intracellular delivery. Nano Lett. 2009;9:1325–1329. doi: 10.1021/nl802962t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.van Engeland M, Nieland LJ, Ramaekers FC, Schutte B, Reutelingsperger CP. Annexin v-affinity assay: A review on an apoptosis detection system based on phosphatidylserine exposure. Cytometry. 1998;31:1–9. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0320(19980101)31:1<1::aid-cyto1>3.0.co;2-r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Doetsch F, Caille I, Lim D, Garciaverdugo J, Alvarezbuylla A. Subventricular zone astrocytes are neural stem cells in the adult mammalian brain. Cell. 1999;97:703–716. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80783-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Xu X, Shrager P. Dependence of axon initial segment formation on na+ channel expression. J Neurosci Res. 2005;79:428–441. doi: 10.1002/jnr.20378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zhou H, et al. Generation of induced pluripotent stem cells using recombinant proteins. Cell Stem Cell. 2009;4:381–384. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2009.04.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Schlegel, et al. Cpp32/apopain is a key interleukin 1beta converting enzyme-like protease involved in fas-mediated apoptosis. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:1841–1844. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.4.1841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lee JS, Brittman S, Yu D, Park H. Vapor-liquid-solid and vapor-solid growth of phase-change sb 2te 3 nanowires and sb 2te 3/gete nanowire heterostructures. J Am Chem Soc. 2008;130:6252–6258. doi: 10.1021/ja711481b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Martensson T, et al. Nanowire arrays defined by nanoimprint lithography. Nano Lett. 2004;4:699–702. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Woodruff JH, Ratchford JB, Goldthorpe IA, McIntyre PC, Chidsey CED. Vertically oriented germanium nanowires grown from gold colloids on silicon substrates and subsequent gold removal. Nano Lett. 2007;7:1637–1642. doi: 10.1021/nl070595x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hulteen JC, Van Duyne RP. Nanosphere lithography: A materials general fabrication process for periodic particle array surfaces. J Vac Sci Technol, A. 1995;13:1553–1558. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kaech S, Banker G. Culturing hippocampal neurons. Nat Protocols. 2006;1:2406–2415. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2006.356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Reynolds BA, Weiss S. Generation of neurons and astrocytes from isolated cells of the adult mammalian central nervous system. Science. 1992;255:1707–1710. doi: 10.1126/science.1553558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sanjana NE, Fuller SB. A fast flexible ink-jet printing method for patterning dissociated neurons in culture. J Neurosci Methods. 2004;136:151–163. doi: 10.1016/j.jneumeth.2004.01.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ionescu-Zanetti C, et al. Mammalian electrophysiology on a microfluidic platform. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102:9112–9117. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0503418102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Arancio O, Kandel ER, Hawkins RD. Activity-dependent long-term enhancement of transmitter release by presynaptic 3′,5′-cyclic gmp in cultured hippocampal neurons. Nature. 1995;376:74–80. doi: 10.1038/376074a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.