Abstract

ISG15 is an IFN-α/β–induced, ubiquitin-like protein that is conjugated to a wide array of cellular proteins through the sequential action of three conjugation enzymes that are also induced by IFN-α/β. Recent studies showed that ISG15 and/or its conjugates play an important role in protecting cells from infection by several viruses, including influenza A virus. However, the mechanism by which ISG15 modification exerts antiviral activity has not been established. Here we extend the repertoire of ISG15 targets to a viral protein by demonstrating that the NS1 protein of influenza A virus (NS1A protein), an essential, multifunctional protein, is ISG15 modified in virus-infected cells. We demonstrate that the major ISG15 acceptor site in the NS1A protein in infected cells is a critical lysine residue (K41) in the N-terminal RNA-binding domain (RBD). ISG15 modification of K41 disrupts the association of the NS1A RBD domain with importin-α, the protein that mediates nuclear import of the NS1A protein, whereas the RBD retains its double-stranded RNA-binding activity. Most significantly, we show that ISG15 modification of K41 inhibits influenza A virus replication and thus contributes to the antiviral action of IFN-β. We also show that the NS1A protein directly and specifically binds to Herc5, the major E3 ligase for ISG15 conjugation in human cells. These results establish a “loss of function” mechanism for the antiviral activity of the IFN-induced ISG15 conjugation system, namely, that it inhibits viral replication by conjugating ISG15 to a specific viral protein, thereby inhibiting its function.

Keywords: interferon, antiviral, dsRNA, Herc5, importin-α

ISG15 is a ubiquitin-like molecule that is highly induced by IFN α/β (1). It is conjugated to more than 100 cellular proteins through the sequential action of three conjugation enzymes that are also induced by IFN-α/β: E1 (Ube1L) (2), E2 (UbcH8) (3, 4), and E3 (Herc5) (5, 6). The vast majority of IFN-induced ISG15 conjugation is mediated by a single E3 enzyme, Herc5, in contrast to the ubiquitin system that uses a large number of E3 enzymes to accomplish target selectivity (7).

ISG15 and/or its conjugation play important roles in innate immunity against several viruses. The first clue to the antiviral property of ISG15 conjugation was the finding that the NS1 protein of influenza B virus binds ISG15 and blocks its conjugation, suggesting that ISG15 and/or its conjugation is inhibitory to the replication of influenza B virus (2). Subsequently, the antiinfluenza activity of ISG15 and/or its conjugation was established by the demonstration that ISG15 knockout (ISG15−/−) mice are more susceptible to both influenza A and B virus infection (8). Experiments with Ube1L−/− mice established that ISG15 conjugation rather than free ISG15 inhibits influenza B virus replication (9). Further, we established that ISG15 conjugation plays a large role in the IFN-induced antiviral state against influenza A virus in human tissue culture cells (10). Thus, siRNA-silencing of ISG15 conjugation enzymes inhibited IFN-induced ISG15 conjugation and partially rescued the IFN-mediated inhibition of influenza A virus gene expression and replication in human cells. ISG15 conjugation has also been shown to inhibit Sindbis virus replication (11, 12), whereas in the case of HIV-1 and Ebola virus, free ISG15 alone most likely causes the inhibition of virus replication (13 –15). Not all viruses are inhibited by ISG15 and/or its conjugation. For example, antivirus activity has not been detected against vesicular stomatitis virus and lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus (8).

The mechanism by which ISG15 conjugation inhibits the replication of influenza virus or any other virus has not been established. Here we extend the repertoire of ISG15 targets to a viral protein by demonstrating that the NS1 protein of influenza A virus (NS1A protein) is targeted by IFN-induced ISG15 conjugation in virus-infected cells. The NS1A protein is an essential viral protein consisting of two functional domains: the N-terminal RNA-binding domain (RBD, residues 1–73) and the effector domain (residues 74–end) (16). The RBD domain of NS1A protein binds double-stranded RNA (dsRNA) (17 –19) and also contains a nuclear localization signal (NLS) that binds importin-α (20). We show that the major ISG15 attachment site is a critical lysine residue (K41) in the RBD and that this ISG15 modification disrupts the association of the RBD with importin-α, whereas dsRNA-binding activity is retained. Most significantly, we show that ISG15 modification of K41 inhibits influenza A virus replication and thus contributes to the antiviral action of IFN-β. We also show that the NS1A protein directly and specifically binds Herc5, the major ISG15 E3 enzyme in human cells. Our findings establish that the IFN-induced ISG15 conjugation system can exert its antiviral activity by conjugating ISG15 to a specific viral protein in infected cell, thereby inhibiting its function and hence virus replication.

Results

Influenza NS1A Protein Is Modified by IFN-Induced ISG15 Conjugation in Infected Cells.

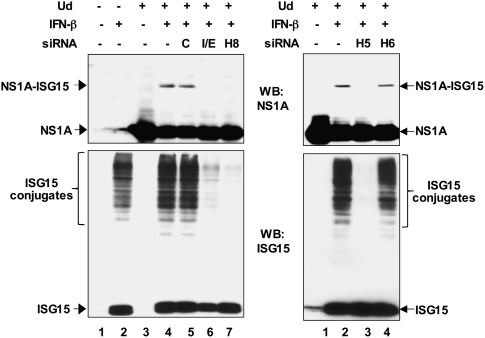

To determine whether any influenza A virus protein is a potential target for ISG15 conjugation in infected cells, we carried out pilot experiments in which 293T cells were cotransfected with plasmids encoding a Flag-tagged viral protein, HA-tagged ISG15, and the enzymes of the ISG15 conjugation system. The NS1A protein of the H3N2 influenza A/Udorn/72 (Ud) virus was ISG15 modified under these conditions, and modification required the presence of all three enzymes of the ISG15 conjugation system (SI Results and Fig. S1). To determine whether ISG15 conjugation of the NS1A protein occurs in infected cells, A549 cells were treated with 100 U/mL of IFN-β for 24 h or left untreated. This level of IFN-β is 10 times lower than the level that was previously shown to inhibit viral protein synthesis almost totally (10). Cells with or without IFN pretreatment were infected with 5 plaque-forming units (pfu)/cell of Ud virus. Extracts from cells collected at 8 h after infection were analyzed by immunoblots probed with anti-NS1A antibody. The synthesis of the NS1A protein was inhibited ≈10-fold by pretreatment with this level of IFN-β, as shown by an immunoblot using a small amount of the extracts (Fig. S2). Using a larger amount of the extracts, a minor IFN-β–induced NS1A species of larger size was also detected in the cells pretreated with IFN-β (Fig. 1, Left, lane 4; Right, lane 2). Several lines of evidence established that this minor species is the NS1A protein conjugated to ISG15. Its size is ≈42 kDa, consistent with the addition of a single ISG15 moiety to the 25-kDa NS1A protein. More definitively, silencing of ISG15 conjugation by transfection of siRNAs targeting either both Ube1L and ISG15 or only UbcH8 eliminated this species (Fig. 1, Left). Further, siRNAs directed against the Herc5 enzyme but not against the related Herc6 enzyme eliminated ISG15 modification of the NS1A protein (Fig. 1, Right), demonstrating that this modification requires all three known IFN-induced ISG15 conjugation enzymes.

Fig. 1.

Influenza NS1A protein is conjugated to ISG15 in infected cells. Where indicated, A549 cells were transfected for 24 h with either control siRNA (C) or siRNA targeting ISG15 and/or its conjugation enzymes: ISG15+Ube1L (I/E), UbcH8 (H8), Herc5 (H5); or siRNA targeting Herc6 (H6). Cells were treated with IFN-β for 24 h and then infected with 5 pfu/cell of Ud virus. Cell extracts prepared from cells collected at 8 h after infection were immunoblotted with either anti-ISG15 or anti-NS1A antibody.

Identification of Lysine Residue K41 as a Major ISG15 Conjugation Site of the NS1A Protein in Infected Cells.

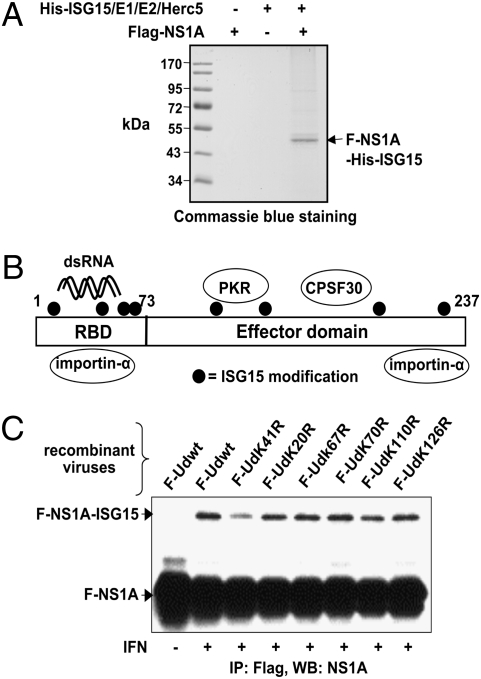

As the first step to elucidate the functional impact of ISG15 modification on the NS1A protein, we identified the ISG15 conjugation sites of the NS1A protein. Because the level of the IFN-induced NS1A-ISG15 conjugate in influenza A virus–infected cells is relatively low, we initiated our identification of NS1A-ISG15 conjugation sites using transfection experiments. Plasmids expressing Flag-tagged Ud NS1A, His-tagged ISG15, and the three ISG15 conjugation enzymes were cotransfected into 293T cells. The Flag-NS1A-His-ISG15 conjugates were purified by sequential affinity selections on Ni-NTA resin and anti-Flag M2 matrix (Fig. 2A). Mass spectrometry analysis of the purified NS1A-ISG15 conjugate identified eight lysine residues that were ISG15 modified (Fig. 2B) (Table S1). The modified lysines were located in both the RBD and the effector domain.

Fig. 2.

Identification of the ISG15 conjugation sites in the NS1A protein. (A) Flag-tagged Ud NS1A was expressed alone or together with His-ISG15 conjugation system in 293T cells by transient transfection. The Flag-NS1A-His-ISG15 conjugate was purified and resolved by gel electrophoresis, as described in Materials and Methods, and was analyzed by mass spectrometry. (B) Location of the ISG15-conjugated lysines identified by mass spectrometry (K20, K41, K67, K70, K110, K126, K196, and K219) in the NS1A protein (Table S1). The positions of the binding sites of several cellular proteins are denoted. (C) A549 cells, with or without IFN pretreatment, were infected with 5 pfu/cell of a recombinant Ud virus expressing the indicated Flag-NS1A (F-NS1A) protein. Infected cell extracts were selected and purified by anti-Flag M2 agarose, followed by immunoblotting using anti-NS1A antibody.

To determine which of these lysines was preferentially modified in infected cells, we generated a panel of recombinant Ud viruses expressing either Flag-tagged WT NS1A or a Flag-tagged NS1A mutant in which one of these lysines was replaced by an arginine residue (KR mutants). Recombinant viruses encoding a NS1A protein with either a K196R or a K219R substitution could not be generated, presumably because R substitutions at either of these positions introduce a missense mutation in the overlapping NS2 protein reading frame. All of the other KR mutant viruses, except the K126R mutant virus, exhibited WT virus replication, indicating that these K-to-R substitutions in the NS1A protein were not attenuating. K126R mutant virus replicated 10-fold slower than WT virus. To determine which of these KR substitutions reduced ISG15 modification of the NS1A protein, cells pretreated with IFN were infected with each of these mutant viruses. The NS1A protein was immunoprecitated from infected cell extracts by anti-Flag M2 matrix, and the immunoprecipitates were immunoblotted using anti-NS1A antibody (Fig. 2C). Among all of the KR mutants, only the NS1A K41R mutant protein showed significant decrease in ISG15 conjugation relative to the WT protein. The decrease in conjugation was 50–60% in several experiments. These results show that IFN-induced ISG15 conjugation of the NS1A protein in infected cells occurs largely on the K41 residue in the RBD.

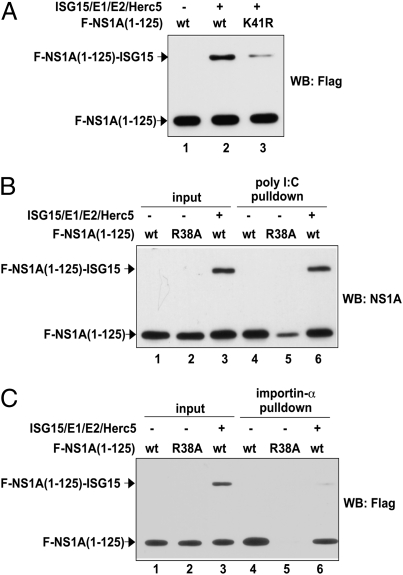

ISG15 Conjugation of K41 Disrupts the Interaction of the NS1A RBD with Importin-α.

Previous studies showed that K41 participates in two crucial NS1A functions. It participates in the binding of the NS1A RBD to dsRNA (18, 19), a function that is critical for viral replication because it causes the inhibition of the activation of the IFN-induced 2′, 5′-oligo(A)synthetase (OAS)/RNaseL antiviral pathway (21). The dsRNA-binding surface comprises tracks of highly conserved basic and hydrophilic residues that are complementary to the phosphate backbone of A-form dsRNA (22). K41 is in this track and contributes to but is not essential for dsRNA binding, whereas the R38 residue in this track is absolutely required for dsRNA binding (18). In addition, K41 is part of the NLS in the RBD (amino acids 35–41) that binds importin-α (20). Both K41 and R38 are critical for importin-α binding and the NLS activity of the NS1A RBD. Surprisingly, the NS1A binding sites for dsRNA and importin-α in the RBD are not totally overlapping, enabling both molecules to bind to the RBD at the same time (20).

We used cotransfection assays in 293T cells to determine the effect of ISG15 conjugation of K41 on the interaction of the RBD with dsRNA and importin-α. Because the Ud NS1A protein possesses a second NLS at its very C terminus that also binds importin-α, we used a plasmid expressing a Ud NS1A fragment that lacks the C-terminal NLS for these experiments, namely, NS1A containing amino acids 1 through 125 [NS1A(1-125)]. Approximately 30–40% of Flag-tagged NS1A(1-125) was modified by ISG15, and the K41R substitution led to a 70–80% reduction in ISG15 conjugation (Fig. 3A), demonstrating that K41 is the predominant site of ISG15 conjugation in the NS1A(1-125) molecule, as is the case in the full-length NS1A protein. The K41R mutant protein did not inhibit overall ISG15 conjugation (Fig. S3). The 293T extracts expressing both unmodified Flag-tagged NS1A(1-125) and its ISG15 conjugates were incubated with either poly(I:C)-agarose (Fig. 3B) or glutathione beads containing bacteria-expressed GST-importin-α (Fig. 3C), and the bound proteins were analyzed by immunoblots with either anti-Flag or anti-NS1A antibody. As a negative control for both assays, extracts expressing the R38A mutant of NS1A(1-125) were subjected to the same procedures. Poly(I:C) pulled down the same relative amounts of unmodified and ISG15-modified NS1A(1-125) that were present in the input extract (compare lanes 3 and 6 in Fig. 3B). In contrast, as compared with the input protein pattern, the GST-importin-α pulldown sample showed a remarkable decrease in the amount of the NS1A(1-125)-ISG15 conjugate relative to the unmodified protein (compare lanes 3 and 6 in Fig. 3C). These results demonstrate that the ISG15 modification of NS1A(1-125), predominantly on the K41 residue, disrupts its interaction with importin-α, whereas its dsRNA-binding activity is retained.

Fig. 3.

ISG15 conjugation of K41 of the NS1A protein selectively disrupts the interaction of its RBD with importin-α. (A) Flag-NS1A(1-125), its K41R mutant, or its R38A mutant were expressed in 293T cells by transfection in the presence or absence of the ISG15 conjugation system, and cell extracts were analyzed using an immunoblot probed by anti-Flag antibody. (B) Extracts of 293T cells transfected with the indicated plasmids were bound to agarose beads coupled to poly(I:C), and the eluant was immunoblotted using anti-NS1A antibody. (C) The same extracts were bound to glutathione beads containing GST-importin-α, and the eluant was immunoblotted using anti-Flag antibody.

ISG15 Modification of K41 of the NS1A Protein Inhibits Influenza A Virus Replication.

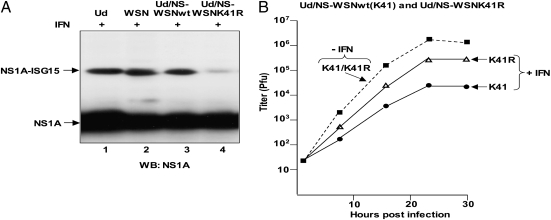

To determine whether ISG15 modification of K41 of the NS1A protein inhibits influenza A virus replication, it was essential to use a virus that encodes an NS1A protein with only one NLS, the one containing K41. The NS1A protein encoded by the H1N1 influenza A/WSN/33 virus (WSN) is such an NS1A protein. In cells pretreated with IFN-β (+IFN), the WSN NS1A protein was ISG15 modified to a similar extent in cells infected with the WSN virus or with a Ud recombinant virus in which the Ud NS gene was replaced by the WSN NS gene (Ud/NS-WSNWT) (Fig. 4A, lanes 2 and 3). A K41R substitution in the WSN NS1A protein in the Ud recombinant virus (Ud/NS-WSNK41R) led to an 80–90% decrease in ISG15 conjugation of the NS1A protein (Fig. 4A, lane 4), demonstrating that K41 is the major ISG15 modification site of the WSN NS1A protein in infected cells.

Fig. 4.

ISG15 modification of K41 of the NS1A protein inhibits influenza A virus replication. (A) IFN-β–pretreated A549 cells were infected with the indicated viruses: Ud, WSN, and recombinant Ud viruses expressing either the WSN NS1A protein (Ud/NS-WSN) or the WSN NS1A K41R mutant protein (Ud/NS-WSNK41R). Cell extracts were immunoblotted using anti-NS1A antibody. (B) HeLa Tet-on cells, with (+IFN) or without (-IFN) pretreatment with IFN-β, were infected with 0.1 pfu/cell of either Ud/NS-WSNwt or Ud/NS-WSNK41R virus, and virus production was determined by plaque assay in MDCK cells.

Elimination of overall IFN-β–induced ISG15 conjugation in human cells only partially protects influenza A virus against the antiviral action of IFN-β because there are several other IFN-β–induced activities that also inhibit influenza A virus replication (10). Our goal was to determine whether the elimination of ISG15 modification of K41 in the WSN NS1A protein (i.e., by introducing a K41R mutation) protects influenza A virus against IFN-β to an extent that is comparable to that provided by overall elimination of ISG15 conjugation. Fig. 4B shows a representative experiment. HeLa Tet-on cells were infected with 0.1 pfu/cell of either of the two Ud/NS-WSN recombinant viruses. In the absence of IFN-β pretreatment (-IFN) the two Ud recombinant viruses, the K41 (WT) and K41R viruses, had indistinguishable kinetics of replication and achieved the same virus yield, demonstrating that the K41R mutation did not cause an inherent defect in virus replication. In contrast, in cells pretreated for 24 h with IFN-β, there was a substantial difference in the replication of the two viruses: the rate of replication and yield of the K41 (WT) virus was reduced 100-fold, whereas the rate of replication and yield of the K41R mutant virus was reduced only 10-fold. Consequently, the K41R mutation in the WSN NS1A protein provided approximately a 10-fold protection against the antiviral action of IFN-β, comparable to that provided by overall elimination of ISG15 conjugation (10). On the basis of this protective effect of the K41R mutation, we conclude that ISG15 modification of K41 of the NS1A protein inhibits influenza A virus replication in IFN-β−treated cells.

NS1A Protein Specifically Binds Herc5, the Major ISG15 E3 in Human Cells.

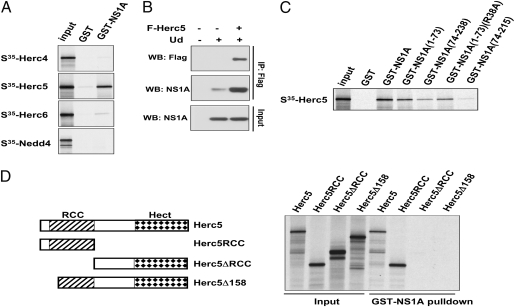

Some ISG15 cellular target proteins have been shown to associate with the Herc5 E3 ligase (6). To determine whether the Ud NS1A protein specifically binds Herc5, we carried out GST-pulldown assays between GST-NS1A and several 35S-labeled E3 ligases synthesized in vitro (Fig. 5A). GST-NS1A specifically pulled down Herc5, but not the related Herc4 and Herc6 proteins nor the Nedd4 ligase. To determine whether the NS1A protein in infected cells binds Herc5, 293T cells were transfected with a plasmid expressing Flag-Herc5, and the cells were then infected with the Ud virus. Immunoprecipitation of Herc5 with anti-Flag antibody pulled down the NS1A protein (Fig. 5B), demonstrating that the NS1A protein in infected cells binds Herc5.

Fig. 5.

The NS1A protein interacts directly with Herc5 ISG15 E3 ligase. (A) 35S-labeled Herc5 protein and three other E3 ligases (Herc4, Herc6, and Nedd4) were subjected to a pulldown assay with glutathione beads containing either GST or GST-NS1A protein purified from bacteria. (B) 293T cells were transfected with a plasmid expressing Flag-tagged Herc5 (F-Herc5) and then infected with Ud virus. Cell extracts were immunoprecipitated with anti-Flag M2 agarose, followed by immunoblots probed with anti-Flag or anti-NS1A antibody. (C) 35S-labeled Herc5 pulldown assay performed with GST-NS1A protein and GST fused to the indicated NS1A mutant proteins. (D) Pulldown assays performed between purified GST-NS1A and 35S-labeled Herc5 deletion mutants. For A–D, the input represents 10% of the total.

To identify the Herc5 interaction surface on NS1A, we tested the Herc5 binding of various NS1A truncation mutants in GST pulldown assays (Fig. 5C). The NS1A RBD [NS1A(1-73)] bound Herc5 almost as well as the full-length protein, and its binding was only slightly reduced by the R38A mutation that eliminates dsRNA-binding activity, indicating that the NS1A RBD-Herc5 interaction is direct and not mediated by RNA. Considerably less Herc5 binding was observed in the full-length NS1A effector domain [NS1A(74-238)] and was almost totally absent in an NS1A effector domain lacking the 22 C-terminal amino acids [NS1A(74-215)]. These results indicate that there is a major Herc5 binding site in the NS1A RBD and apparently a minor binding site in the C-terminal region of the NS1A effector domain.

By analyzing the ability of Herc5 deletions to bind GST-NS1A (Fig. 5D), we determined that the N-terminal regulation of chromosome condensation (RCC) domain of Herc5 (plus the short adjacent N-terminal region) was necessary and sufficient for binding the NS1A protein.

Discussion

Here we established that the IFN-induced ISG15 conjugation system targets the NS1A protein of influenza A virus in infected cells. We showed that the NS1A protein is conjugated to ISG15 in infected cells that were pretreated with IFN-β and that the predominant conjugation site is K41 in the NS1A RBD. ISG15 modification of K41 results in the loss of a function of the RBD, specifically the binding of its NLS to importin-α. This NLS is essential for the nuclear import of NS1A proteins that lack a second, C-terminal NLS (20, 21), which includes those encoded by WSN and all human influenza A viruses isolated after 1989 (20). A defect in the NLS function of the RBD is not as crucial for the NS1A protein of Ud virus because it has a second, C-terminal NLS (20).

In contrast to its effect on importin-α binding, ISG15 modification of K41 did not eliminate dsRNA-binding, as assayed using poly(I:C) to pull down a Ud NS1A(1-125) protein that was expressed at high levels in transfected 293T cells. This transfection result, however, does not necessarily indicate that ISG15 modification of K41 does not affect the dsRNA-binding activity of the NS1A protein that is synthesized in infected cells. It has been shown that assays of the dsRNA-binding activity of the NS1A protein using overexpression in transient transfection experiments overestimate the actual weak dsRNA-binding activity exhibited by the NS1A protein during influenza A virus infection (21). Consequently, it is possible that ISG15 modification of K41 of the NS1A protein in infected cells could result in a reduction or even a loss of NS1A dsRNA-binding activity. If dsRNA-binding were reduced or lost in infected cells, this would limit or eliminate the ability of the NS1A protein to inhibit the activation of the IFN-induced OAS/RNase L pathway (21).

Most significantly, we showed that ISG15 modification of K41 of the NS1A protein inhibits influenza A virus replication and thus contributes to the antiviral action of IFN-β. Using a virus encoding the WSN NS1A protein that contains only one NLS, the NLS that includes K41, we demonstrated that changing K41 to R rendered the virus ≈10-fold more resistant to the antiviral action of IFN-β. This level of protection is comparable to that provided by eliminating overall ISG15 conjugation (10), indicating that eliminating the ISG15 modification of this single NS1A amino acid is responsible for a large part of the protection. Consequently, ISG15 modification of K41 significantly inhibits virus replication despite the fact that only a small fraction (2–5%) of the steady-state amount of the NS1A protein contains an ISG15-modified K41 amino acid, Similarly, it was recently reported that ISG15 conjugation of filamin B, which impacts only a small fraction of the steady-state amount of the protein, abrogates a major function of filamin B (23). These ISG15 results are similar to those obtained with another ubiquitin-like protein, SUMO, whereby low steady-state levels of modification of a protein affect its function (24). It has been postulated that rapid modification by SUMO is followed by equally rapid deconjugation, resulting in a low steady-state level of a SUMO-modified protein, but that the initial modification by SUMO leads to a permanently altered function of the protein. It is not known whether the SUMO model applies to the ISG15 modification of the NS1A protein in influenza A virus–infected cells.

We also showed that the NS1A protein specifically and directly binds Herc5, the major E3 ligase for ISG15 conjugation. This interaction, which is independent of the dsRNA-binding activity of the NS1A protein, is mediated largely by a protein–protein interaction between a region of the NS1A RBD and the RCC domain of Herc5. It is reasonable to postulate that IFN pretreatment leads to comparable amounts of Herc5 and NS1A proteins in infected cells, because this pretreatment induces a 10–30-fold increase in Herc5 expression (5, 6) and inhibits the synthesis of the NS1A protein 10–30-fold (10). It is therefore likely that in infected cells pretreated with IFN-β the majority of both Herc5 and the NS1A protein are complexed with each other. A possible consequence is that the NS1A protein sequesters Herc5 away from catalyzing the ISG15 modification of other influenza A virus proteins, thereby explaining at least in part our finding that the NS1A protein is the major influenza A virus protein that is targeted by the IFN-β–induced ISG15 conjugation system in infected cells. We have found that only one other viral protein, the M1 (matrix) protein, undergoes detectable ISG15 conjugation in infected cells pretreated with IFN-β (Fig. S4). Conversely, Herc5 might sequester the NS1A protein away from carrying out its functions during infection. Future identification of an NS1A mutant defective in Herc5 binding will be required to test these possibilities.

In conclusion, we have shown that IFN-induced ISG15 modification of the K41 residue of the NS1A protein causes a loss of function of the NS1A protein and the inhibition of influenza A virus replication. It is interesting that the NS1A protein, which is responsible for countering key components of the host antiviral system (25), is itself targeted by a major host antiviral system, IFN-induced ISG15 conjugation. These results establish a “loss of function” mechanism for the antiviral activity of the IFN-induced ISG15 conjugation system, namely, that it inhibits viral replication by conjugating ISG15 to a specific viral protein, thereby inhibiting its function.

Materials and Methods

Recombinant influenza A viruses were generated using plasmid-based reverse genetics, as described in SI Materials and Methods. To identify NS1A-ISG15 conjugates in virus-infected cells. A549 cells were treated with 100 U/mL of IFN-β for 24 h and then infected with 5 pfu/cell of the indicated influenza A virus expressing either untagged or N-terminal Flag-tagged NS1A protein. Infected cell extracts were analyzed for the presence of NS1A-ISG15 conjugates as described in the legends of Figs. 1 and 2. Where indicated, siRNAs (20 mM) were transfected into the cells 24 h before IFN treatment, as described previously (10). The siRNAs targeting Herc5, Herc6, ISG15, Ube1L, and UbcH8 were described previously (5, 10). As shown previously (10), siRNA knockdown of UbE1L alone in A549 cells did not achieve efficient inhibition of ISG15 conjugation, and it was necessary to include an siRNA directed against ISG15.

To identify ISG15 conjugation sites in the NS1A protein, 293T cells were cotransfected with plasmids expressing Flag-Ud NS1A, His-ISG15, and the three ISG15 conjugation enzymes. The Flag-NS1A-His-ISG15 conjugate in the transfected cell extract was purified using sequential affinity selection on Ni-NTA resin and anti-Flag M2 agarose (26), followed by electrophoresis on a 10% SDS polyacrylamide gel. The purified protein band was analyzed by mass spectrometry to identify ISG15-modified lysines (Table S1). To determine whether the NS1A-ISG15 conjugate binds dsRNA or importin-α, a plasmid expressing Flag-Ud NS1A(1-125), with or without the four plasmids expressing ISG15 and its conjugation enzymes, was tranfected into 293T cells, and cell extracts were subjected to affinity selection using either poly(I:C)-coupled agarose beads or glutathione beads containing GST-importin-α fusion (provided by Krister Melén) (20). The eluates were analyzed by immunoblots probed with anti-NS1A or anti-Flag antibody to detect the presence of unmodified and ISG15-conjugated NS1A protein. To determine whether the K41R mutation protected influenza A virus against IFN-induced ISG15 conjugation, HeLa Tet-on cells, with or without prior treatment with IFN-β, were infected with 0.1 pfu/cell of either the Ud/NS-WSNwt or Ud/NS-WSNK41R recombinant virus, and the amount of virus produced was determined by plaque assays in Madin-Darby canine kidney (MDCK) cells.

In vitro and in vivo assays for the interaction of the NS1A protein with Herc5 were carried out as described in the legend of Fig. 5 and in SI Materials and Methods.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This investigation was supported by National Institutes of Health Grant AI-11772 (to R.M.K.).

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/cgi/content/full/0909144107/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Haas AL, Ahrens P, Bright PM, Ankel H. Interferon induces a 15-kilodalton protein exhibiting marked homology to ubiquitin. J Biol Chem. 1987;262:11315–11323. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Yuan W, Krug RM. Influenza B virus NS1 protein inhibits conjugation of the interferon (IFN)-induced ubiquitin-like ISG15 protein. EMBO J. 2001;20:362–371. doi: 10.1093/emboj/20.3.362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zhao C, et al. The UbcH8 ubiquitin E2 enzyme is also the E2 enzyme for ISG15, an IFN-alpha/beta-induced ubiquitin-like protein. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:7578–7582. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0402528101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kim KI, Giannakopoulos NV, Virgin HW, Zhang DE. Interferon-inducible ubiquitin E2, Ubc8, is a conjugating enzyme for protein ISGylation. Mol Cell Biol. 2004;24:9592–9600. doi: 10.1128/MCB.24.21.9592-9600.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dastur A, Beaudenon S, Kelley M, Krug RM, Huibregtse JM. Herc5, an interferon-induced HECT E3 enzyme, is required for conjugation of ISG15 in human cells. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:4334–4338. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M512830200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wong JJ, Pung YF, Sze NS, Chin KC. HERC5 is an IFN-induced HECT-type E3 protein ligase that mediates type I IFN-induced ISGylation of protein targets. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:10735–10740. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0600397103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ardley HC, Robinson PA. E3 ubiquitin ligases. Essays Biochem. 2005;41:15–30. doi: 10.1042/EB0410015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lenschow DJ, et al. IFN-stimulated gene 15 functions as a critical antiviral molecule against influenza, herpes, and Sindbis viruses. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104:1371–1376. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0607038104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lai C, et al. Mice lacking the ISG15 E1 enzyme UbE1L demonstrate increased susceptibility to both mouse-adapted and non-mouse-adapted influenza B virus infection. J Virol. 2009;83:1147–1151. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00105-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hsiang TY, Zhao C, Krug RM. Interferon-induced ISG15 conjugation inhibits influenza A virus gene expression and replication in human cells. J Virol. 2009;83:5971–5977. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01667-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lenschow DJ, et al. Identification of interferon-stimulated gene 15 as an antiviral molecule during Sindbis virus infection in vivo. J Virol. 2005;79:13974–13983. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.22.13974-13983.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Giannakopoulos NV, et al. ISG15 Arg151 and the ISG15-conjugating enzyme UbE1L are important for innate immune control of Sindbis virus. J Virol. 2009;83:1602–1610. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01590-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Okumura A, Lu G, Pitha-Rowe I, Pitha PM. Innate antiviral response targets HIV-1 release by the induction of ubiquitin-like protein ISG15. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:1440–1445. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0510518103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Okumura A, Pitha PM, Harty RN. ISG15 inhibits Ebola VP40 VLP budding in an L-domain-dependent manner by blocking Nedd4 ligase activity. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105:3974–3979. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0710629105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Malakhova OA, Zhang DE. ISG15 inhibits Nedd4 ubiquitin E3 activity and enhances the innate antiviral response. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:8783–8787. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C800030200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Krug RM, Yuan W, Noah DL, Latham AG. Intracellular warfare between human influenza viruses and human cells: The roles of the viral NS1 protein. Virology. 2003;309:181–189. doi: 10.1016/s0042-6822(03)00119-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hatada E, Fukuda R. Binding of influenza A virus NS1 protein to dsRNA in vitro. J Gen Virol. 1992;73:3325–3329. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-73-12-3325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wang W, et al. RNA binding by the novel helical domain of the influenza virus NS1 protein requires its dimer structure and a small number of specific basic amino acids. RNA. 1999;5:195–205. doi: 10.1017/s1355838299981621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cheng A, Wong SM, Yuan YA. Structural basis for dsRNA recognition by NS1 protein of influenza A virus. Cell Res. 2009;19:187–195. doi: 10.1038/cr.2008.288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Melén K, et al. Nuclear and nucleolar targeting of influenza A virus NS1 protein: Striking differences between different virus subtypes. J Virol. 2007;81:5995–6006. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01714-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Min JY, Krug RM. The primary function of RNA binding by the influenza A virus NS1 protein in infected cells: Inhibiting the 2′-5′ oligo (A) synthetase/RNase L pathway. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:7100–7105. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0602184103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yin C, et al. Conserved surface features form the double-stranded RNA binding site of non-structural protein 1 (NS1) from influenza A and B viruses. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:20584–20592. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M611619200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jeon YJ, et al. ISG15 modification of filamin B negatively regulates the type I interferon-induced JNK signalling pathway. EMBO Rep. 2009;10:374–380. doi: 10.1038/embor.2009.23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hay RT. SUMO: A history of modification. Mol Cell. 2005;18:1–12. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2005.03.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hale BG, Randall RE, Ortín J, Jackson D. The multifunctional NS1 protein of influenza A viruses. J Gen Virol. 2008;89:2359–2376. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.2008/004606-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Okumura F, Zou W, Zhang DE. ISG15 modification of the eIF4E cognate 4EHP enhances cap structure-binding activity of 4EHP. Genes Dev. 2007;21:255–260. doi: 10.1101/gad.1521607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.